| Revision as of 14:40, 14 February 2008 view sourceYorkshirian (talk | contribs)12,364 edits rmv shankbone's trolling, he was explicity warned by an admin to leave it off the page for a while and discuss first.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 16:21, 9 December 2024 view source Jason.nlw (talk | contribs)Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users3,371 edits better version of image | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|English participant in the 1605 Gunpowder Plot}} | |||

| {{other uses|Guido Fawkes (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{About|the historical figure}} | |||

| {{Infobox Criminal | |||

| {{featured article}} | |||

| | subject_name = Guy Fawkes | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | image_name = Guy Fawkes portrait.jpg | |||

| {{Use British English|date=March 2020}} | |||

| | image_size = 200px | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2022}} | |||

| | image_caption = A modern illustration of Guy Fawkes with the ] in the background. | |||

| {{bots|deny=Citation bot}} | |||

| | date_of_birth = {{birth date|1570|4|13}} | |||

| {{Infobox gunpowder plot | |||

| | place_of_birth = ], ], ] | |||

| | name = Guy Fawkes | |||

| | date_of_death = {{death date and age|1606|1|31|1570|4|13}} | |||

| | image = The Gunpowder Plot Conspirators, 1605 from NPG (cropped).jpg | |||

| | place_of_death = ], ] | |||

| | alt = Black-and-white drawing | |||

| | charge = Conspiracy to assassinate king ] and members of the ] | |||

| | caption = A contemporary engraving of Fawkes made in 1605 | |||

| | penalty = ] | |||

| | |

| enlisted = 20 May 1604 | ||

| | |

| role = Explosives | ||

| | |

| apprehended = 5 November 1605 | ||

| | |

| birth_name = | ||

| | |

| birth_date = 13 April 1570 (presumed) | ||

| | birth_place = ], England | |||

| | death_date = 31 January 1606 (aged 35) | |||

| | death_place = ], London, England | |||

| | other_names = Guido Fawkes, John Johnson | |||

| | motive = ], a conspiracy to assassinate King ] and members of the ] | |||

| | criminal_charge = | |||

| | conviction = ] | |||

| | conviction_penalty = ] | |||

| | conviction_status = Executed | |||

| | occupation = Soldier, ] | |||

| | spouse = | |||

| | parents = {{ubl|Edward Fawkes (father) | Edith (née Blake or Jackson) (mother)}} | |||

| | children = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Guy Fawkes''' ({{IPAc-en|f|ɔː|k|s}}; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606),{{efn|Dates in this article before ] are given in the Julian calendar. The beginning of the year is treated as 1 January even though it began in England on 25 March.}} also known as '''Guido Fawkes''' while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial ] involved in the failed ] of 1605. He was born and educated in ]; his father died when Fawkes was eight years old, after which his mother married a ] Catholic. | |||

| '''Guy Fawkes''' (] ] – ] ]) sometimes known as '''Guido Fawkes''', was a member of a group of ] revolutionaries from ] who planned to carry out the ].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.thisweek-online.com/2005/September/30bonfire.html|publisher=ThisWeek-Online.com|title=Transplanted Englishman brings countryís Guy Fawkes party tradition to Burnsville|date=] ]}}</ref> The plot was an attempt to blow up the ], which would have displaced ] rule by killing King ] and the entire Protestant ], on ] ]. | |||

| Fawkes converted to Catholicism and left for mainland Europe, where he fought for Catholic Spain in the ] against Protestant Dutch ] in the ]. He travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England without success. He later met ], with whom he returned to England. Wintour introduced him to ], who planned to assassinate {{nowrap|]}} and restore a Catholic monarch to the throne. The plotters leased an ] beneath the ]; Fawkes was placed in charge of the gunpowder that they stockpiled there. The authorities were prompted by an anonymous letter to search ] during the early hours of 5 November, and they found Fawkes guarding the explosives. He was questioned and tortured over the next few days and confessed to wanting to blow up the House of Lords. | |||

| Although ] was the lead figure in thinking up the actual plot, Fawkes was put in charge of executing the plan due to his ] and ] experience. The plot was foiled shortly before its intended completion, as Fawkes was captured while guarding the gunpowder. Suspicion was aroused by his wearing a coat, boots and spurs, as if he intended to leave very quickly. | |||

| Fawkes was sentenced to be ]. However, at his execution on 31 January, he died when his neck was broken as he was hanged, with some sources claiming that he deliberately jumped to make this happen; he thus avoided the agony of his sentence. He became synonymous with the ], the failure of which has been commemorated in the UK as ] since 5 November 1605, when his effigy is traditionally burned on a bonfire, commonly accompanied by fireworks. | |||

| Fawkes has left a lasting mark on history and ]. Held in the ] (and some parts of the ]) on November 5 is ], centred on the plot and Fawkes. He has been mentioned in popular film, literature and music by people such as ] and ]. There are geographical locations named after Fawkes, such as '']'' in the ] and ] in ]. | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| ===Childhood=== | ===Childhood=== | ||

| ] | ], next to ] (seen at left).]] | ||

| Guy Fawkes was born in 1570 in ], York. He was the second of four children born to Edward Fawkes, a ] and an advocate of the ] at York,{{efn|According to one source, he may have been Registrar of the Exchequer Court of the Archbishop.{{sfn|Haynes|2005|pp=28–29|ps=}}}} and his wife, Edith.{{efn|Fawkes's mother's maiden name is alternatively given as Edith Blake,<ref>{{citation |url=http://www.gunpowder-plot.org/fawkes.asp |title=Guy Fawkes |publisher=The Gunpowder Plot Society |access-date=19 May 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100318043708/http://www.gunpowder-plot.org/fawkes.asp |archive-date=18 March 2010 }}</ref> or Edith Jackson.<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/>}} Guy's parents were regular ] of the ], as were his paternal grandparents; his grandmother, born Ellen Harrington, was the daughter of a prominent merchant, who served as ] in 1536.<ref>"Fawkes, Guy" in ''],'' ], ed., Oxford University Press, London (1921–1922).</ref> Guy's mother's family were ], and his cousin, Richard Cowling, became a ] priest.<ref name="Fraser 2005 84">{{Harvnb|Fraser|2005|p=84}}</ref> ''Guy'' was an uncommon name in England, but may have been popular in York on account of a local notable, Sir ] of Steeton.<ref name="Sharpep48">{{Harvnb|Sharpe|2005|p=48}}</ref> | |||

| Born on ] 1570 at Stonegate in ], ], Fawkes was the only son of Edward Fawkes and Edith Blake. His mother had given birth to a daughter a couple of years earlier, named Anne who died seven weeks later on ] 1568. Guy was originally ] in the church of ] on ] 1570 as a three day old baby.<ref name="peter">{{cite news|url=http://www.st-peters.york.sch.uk/history/guyfawkes.htm|publisher=St-Peters.york.sch.uk|title=Guy Fawkes - Old Peterite|date=] ]}}</ref> In the five years following Fawkes' birth, his mother also bore two more daughters, Anne (named in honour of the earlier deceased child) and Elizabeth.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.britannia.com/history/g-fawkes.html|publisher=Britannia.com|title=Guy Fawkes: A Biography|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| The date of Fawkes's birth is unknown, but he was ] in the church of ] on 16 April. As the customary gap between birth and baptism was three days, he was probably born about 13 April.<ref name="Fraser 2005 84"/> In 1568, Edith had given birth to a daughter named Anne, but the child died aged about seven weeks, in November that year. She bore two more children after Guy: Anne (b. 1572), and Elizabeth (b. 1575). Both were married, in 1599 and 1594 respectively.<ref name="Sharpep48"/>{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=86 (note)|ps=}} | |||

| He attended ] in ], where his schoolfellows may have included ] and ], both of whom would be among the conspirators of the Gunpowder Plot, and ], who became ].<ref name="peter">{{cite news|url=http://www.st-peters.york.sch.uk/history/guyfawkes.htm|publisher=St-Peters.york.sch.uk|title=Guy Fawkes - Old Peterite|date=] ]}}</ref> During Fawkes's time at St Peter's he was under the tutelage of John Pulleyn, kinsman to the Pulleyns of Scotton and a suspected Catholic who, according to some sources, may have had an early effect on the impressionable Fawkes.<ref name="peter">{{cite news|url=http://www.st-peters.york.sch.uk/history/guyfawkes.htm|publisher=St-Peters.york.sch.uk|title=Guy Fawkes - Old Peterite|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| In 1579, when Guy was eight years old, his father died. His mother remarried several years later, to the Catholic Dionis Baynbrigge (or Denis Bainbridge) of ]. Fawkes may have become a Catholic through the Baynbrigge family's recusant tendencies, and also the Catholic branches of the Pulleyn and Percy families of Scotton,{{sfn|Sharpe|2005|p=49|ps=}} but also from his time at ] in York. A governor of the school had spent about 20 years in prison for recusancy, and its headmaster, John Pulleyn, came from a family of noted Yorkshire recusants, the Pulleyns of ]. In her 1915 work ''The Pulleynes of Yorkshire'', author Catharine Pullein suggested that Fawkes's Catholic education came from his Harrington relatives, who were known for harbouring priests, one of whom later accompanied Fawkes to ] in 1592–1593.<ref name="Herber"/> Fawkes's fellow students included ] and his brother ] (both later involved with Fawkes in the ]) and ], ] and Robert Middleton, who became priests (the latter executed in 1601).{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=84–85|ps=}} | |||

| Fawkes's father was a descendant of the Fawkes family in ]; he was either a ] or ] of the ]s and later an advocate of the ] of the ]. Edward's wife, Edith Blake, was descended from prominent merchants and ] of the city. Edward Fawkes died in 1579, and his widow remarried in 1582, to a Catholic, Denis Bainbridge of ]. The family were known to be ], resisters of the authority of the ], and it is probable that his stepfather's influence contributed to Guy’s affiliation to ]; Fawkes finally converted to Catholicism around the age of 16.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.northeasthistory.co.uk/the_north_east/history/features/205/051105.html|publisher=North East History|title=A man for all treason|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| After leaving school Fawkes entered the service of ].<!-- Browne was one of the leading statesmen during the time of Catholic ], and was also allegedly implicated in the ] --> The Viscount took a dislike to Fawkes and after a short time dismissed him; he was subsequently employed by ], who succeeded his grandfather at the age of 18.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=85–86|ps=}} At least one source claims that Fawkes married and had a son, but no known contemporary accounts confirm this.<ref name="Fraserp86">{{Harvnb|Fraser|2005|p=86}}</ref>{{efn|According to the ], compiled by the ], Fawkes married Maria Pulleyn (b. 1569) in Scotton in 1590, and had a son, Thomas, on 6 February 1591.<ref name="Herber">{{citation |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110617064347/http://www.gunpowder-plot.org/news/1998_04/gfmp.htm |archive-date=17 June 2011 |url=http://www.gunpowder-plot.org/news/1998_04/gfmp.htm |publisher=The Gunpowder Plot Society |contribution=The Marriage of Guy Fawkes and Maria Pulleyn |title=The Gunpowder Plot Society Newsletter |issue= 1 |date=April 1998 |last=Herber |first=David |access-date=16 February 2010}}</ref> These entries, however, appear to derive from a secondary source and not from actual parish entries.<ref name="Fraserp86"/>}}<!-- After renting them out for a while as a way to earn money, he sold his stakes in them to Anne Skipsey.{{fact|date=November 2010}} --> | |||

| ===Occupation as a soldier=== | |||

| After leaving school, Fawkes became a ] for ]. Browne was one of the leading statesmen during the time of Catholic monarch of Scotland ] and was also allegedly implicated in the ]. Browne took a disliking to Fawkes and fired him after a short time.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Fraser | |||

| | first = Antonia | |||

| | authorlink = Antonia Fraser | |||

| | title =Faith And Treason | |||

| | publisher =Nan A. Talese | |||

| | url =http://www.amazon.com/Faith-Treason-Antonia-Fraser/dp/0385471890 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0385471893}}</ref> However, his grandson ] re-employed Fawkes as a table waiter.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.gunpowder-plot.org/york-flanders.asp|publisher=Gunpowder-Plot.org|title=Guy Fawkes: From York to the Battlefields of Flanders|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| ===Military career=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In October 1591 Fawkes sold the estate in ] in York that he had inherited from his father.{{efn|Although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography claims 1592, multiple alternative sources give 1591 as the date. Peter Beal, ''A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology, 1450 to 2000'', includes a signed indenture of the sale of the estate dated 14 October 1591. (pp. 198–199)}} He travelled to the continent to fight in the ] for Catholic Spain against the new ] and, from 1595 until the ] in 1598, France. Although England was not by then engaged in land operations against Spain, the two countries were ], and the attempted invasion of England, led by the ] in 1588, was only five years in the past. He joined ], an English Catholic and veteran commander in his mid-forties who had raised an army in Ireland to fight in ]. Stanley had been held in high regard by ], but following his surrender of ] to the Spanish in 1587 he, and most of his troops, had switched sides to serve Spain. Fawkes became an ] or junior officer, fought well at the ], and by 1603 had been recommended for a ].<ref name="ODNB Fawkes">{{citation |last=Nicholls |first=Mark |contribution=Fawkes, Guy (bap. 1570, d. 1606) |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2004 |edition=online |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/9230 |doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/9230}} {{ODNBsub}}</ref> That year, he travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England. He used the occasion to adopt the Italian version of his name, Guido, and in his memorandum described ] (who became king of England that year) as "a heretic", who intended "to have all of the Papist sect driven out of England." He denounced Scotland, and the King's ]s among the Scottish nobles, writing "it will not be possible to reconcile these two nations, as they are, for very long".{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=89|ps=}} Although he was received politely, the court of ] was unwilling to offer him any support.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=87–90|ps=}} | |||

| He enlisted in the army of ] in the ] and fought with the armies of Catholic Spain against the ] ] in the ] . It was during this time that Fawkes adopted the name Guido, the Spanish form of Guy. He served for many years as a ], gaining considerable expertise with ]s, which is the most likely reason that conspirators Winter and Catesby recruited him. | |||

| ==Gunpowder Plot== | |||

| The Netherlands were then possessions of King ], ], and a foreigner to the Dutch. The Dutch associated Spain and Philip's rule with the Catholic ], which he had tried to impose on his territories in the Low Countries. Fawkes arrived at a time when the death of the ] and ] by Spanish ] had left the Catholic military force in the Netherlands paralysed, and ], the stadtholder in five provinces from 1584 till 1625, son of ], had led successful campaigns against Spanish positions | |||

| {{Main|Gunpowder Plot}} | |||

| ]. Fawkes is third from the right.]] | |||

| In 1596 Fawkes was present at the siege and capture of ]. By 1602 he had risen only to the rank of ]. There is some evidence that Fawkes was in considerable poverty around this time. He may have visited Spain in the early 1600s to request Spanish help in returning England to Catholicism. | |||

| In 1604 Fawkes became involved with a small group of English Catholics, led by ], who planned to assassinate the ] ] and replace him with his daughter, third in the line of succession, ].{{sfn|Northcote Parkinson|1976|p=46|ps=}}{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=140–142|ps=}} Fawkes was described by the Jesuit priest and former school friend ] as "pleasant of approach and cheerful of manner, opposed to quarrels and strife ... loyal to his friends". Tesimond also claimed Fawkes was "a man highly skilled in matters of war", and that it was this mixture of piety and professionalism that endeared him to his fellow conspirators.<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/> The author ] describes Fawkes as "a tall, powerfully built man, with thick reddish-brown hair, a flowing moustache in the tradition of the time, and a bushy reddish-brown beard", and that he was "a man of action ... capable of intelligent argument as well as physical endurance, somewhat to the surprise of his enemies."<ref name="Fraser 2005 84"/> | |||

| == Gunpowder Plot == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Gunpowder Plot}} | |||

| The first meeting of the five central conspirators took place on Sunday 20 May 1604, at an inn called the Duck and Drake, in the fashionable ] district of London.{{efn|Also present were fellow conspirators John Wright, ], and ] (with whom he was already acquainted).<ref name="Fraserpp117119">{{Harvnb|Fraser|2005|pp=117–119}}</ref>}} Catesby had already proposed at an earlier meeting with ] and John Wright to kill the King and his government by blowing up "the Parliament House with gunpowder". Wintour, who at first objected to the plan, was convinced by Catesby to travel to the continent to seek help. Wintour met with the Constable of Castile, the exiled Welsh spy Hugh Owen,{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=87|ps=}} and Sir William Stanley, who said that Catesby would receive no support from Spain. Owen did, however, introduce Wintour to Fawkes, who had by then been away from England for many years, and thus was largely unknown in the country. Wintour and Fawkes were contemporaries; each was militant, and had first-hand experience of the unwillingness of the Spaniards to help. Wintour told Fawkes of their plan to "doe some whatt in Ingland if the pece with Spaine healped us nott",<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/> and thus in April 1604 the two men returned to England.<ref name="Fraserpp117119"/> Wintour's news did not surprise Catesby; despite positive noises from the Spanish authorities, he feared that "the deeds would nott answere".{{efn|] made peace with England in August 1604.<ref name="ODNB Catesby">{{citation |last=Nicholls |first=Mark |contribution=Catesby, Robert (b. in or after 1572, d. 1605) |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2004 |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/4883/ |doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/4883}} {{ODNBsub}}</ref>}} | |||

| Fawkes is notorious for his involvement in the Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was probably placed in charge of executing the plot because of his military and explosives experience. The plot, masterminded by ], was an attempt by a group of religious conspirators to kill King ], his family, and most of the aristocracy by blowing up the House of Lords in the ] during the ]. Fawkes may have been introduced to Catesby by ], a man who was in the pay of the ]. ] is also believed to have recommended him, and Fawkes named him under torture, leading to his arrest and imprisonment for a day after the discovery of the plot. It was Stanley who first presented Fawkes to ] in 1603 when Winter was in Europe. Stanley was the commander of the English in ] at the time. Stanley had handed ] and much of its garrison back to the Spanish in 1587, nearly wiping out the gains that ] had made in the ]. Leicester’s expedition was widely regarded as a disaster, for this reason among others. | |||

| One of the conspirators, ], was appointed a ] in June 1604, gaining access to a house in London that belonged to John Whynniard, Keeper of the King's Wardrobe. Fawkes was installed as a caretaker and began using the pseudonym John Johnson, servant to Percy.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=122–123|ps=}} The contemporaneous account of the prosecution (taken from Thomas Wintour's confession)<ref name="ODNB Thomas Wintour">{{citation |last=Nicholls |first=Mark |contribution=Winter, Thomas (c. 1571–1606) |title=Oxford Dictionary of National Biography |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2004 |url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/29767 |doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/29767}} {{ODNBsub}}</ref> claimed that the conspirators attempted to dig a tunnel from beneath Whynniard's house to Parliament, although this story may have been a government fabrication; no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found; Fawkes himself did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation, but even then he could not locate the tunnel.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=133–134|ps=}} If the story is true, however, by December 1604 the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. Fawkes was sent out to investigate, and returned with the news that the tenant's widow was clearing out a nearby ], directly beneath the House of Lords.<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/>{{sfn|Haynes|2005|pp=55–59|ps=}} | |||

| The best primary source for the details of the plot itself is the account known as the ''King's Book'' or ''James I The Kings Book - A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors. Robt. Barker, Printer to the Kings Most Excellent Majesty, British Museum 1606''. Although this is a government account, and details have been disputed, it is generally considered to be an accurate record of the history of the plot, and the imprisonment, torture and execution of the plotters. | |||

| {{Gunpowder plotters}} | |||

| The plot itself may have been occasioned by the realisation by Protestant authorities and Roman Catholic ] that the Kingdom of Spain was in far too much debt and were fighting too many wars to assist Roman Catholics in the South of Britain. Any possibility of toleration by Great Britain was removed at the ] in 1604 when King James I attacked both extreme ] and Catholics. The plotters realised that no outside help would be forthcoming unless they took action themselves. Fawkes and the other conspirators rented a cellar beneath the House of Lords having first tried to dig a tunnel under the building. This would have proved difficult, because they would have had to dispose of the dirt and debris. (No evidence of this tunnel has ever been found). By March ], they had hidden 1800 ] (36 barrels, or 800 ]) of ] in the cellar. The plotters also intended to abduct Princess ] (later Elizabeth of Bohemia, the "Winter Queen"). A few of the conspirators were concerned, however, about fellow Catholics who would have been present at Parliament during the opening. One of the conspirators wrote a warning letter to ], who received it on ]. The conspirators became aware of the letter the following day, but they resolved to continue the plot after Fawkes had confirmed that nothing had been touched in the cellar. | |||

| The plotters purchased the lease to the room, which also belonged to John Whynniard. Unused and filthy, it was considered an ideal hiding place for the gunpowder the plotters planned to store.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=144–145|ps=}} According to Fawkes, 20 barrels of gunpowder were brought in at first, followed by 16 more on 20 July.<ref name="Fraserpp146147">{{Harvnb|Fraser|2005|pp=146–147}}</ref> On 28 July however, the ever-present threat of the plague delayed the opening of Parliament until Tuesday, 5 November.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=159–162|ps=}} | |||

| Lord Monteagle had been made suspicious, however; the letter was sent to the Secretary of State, who initiated a search of the vaults beneath the House of Lords in the early morning of ]. Peter Heywood, a resident of ], was reputedly the man who snatched the torch from Guy Fawkes’s hand as he was about to light the fuse to detonate the gunpowder. Fawkes was tortured over the next few days, after the King granted special permission to do so. James directed that the torture should be gentle at first, and then more severe. Sir William Wade, Lieutenant of the ] at this time, supervised the torture and obtained Fawkes's confession. For three or four days Fawkes said nothing, let alone divulge the names of his co-conspirators. Only when he found out that they had proclaimed themselves by appearing in arms did he succumb. The torture only revealed the names of those conspirators who were already dead or whose names were known to the authorities. Some had fled to ], ], where they were killed or captured. On ], Fawkes and a number of others implicated in the ] were tried in ]. After being found guilty, they were taken to ] in ] and St Paul's Yard, where they were ]. Fawkes, however, managed to avoid the worst of this ] by jumping from the scaffold where he was supposed to be hanged, breaking his neck before he could be drawn and quartered ("The King's Book.",1606.) | |||

| ] | |||

| == |

===Overseas=== | ||

| In an attempt to gain foreign support, in May 1605 Fawkes travelled overseas and informed Hugh Owen of the plotters' plan.{{sfn|Bengsten|2005|p=50|ps=}} At some point during this trip his name made its way into the files of ], who employed a network of spies across Europe. One of these spies, Captain William Turner, may have been responsible. Although the information he provided to Salisbury usually amounted to no more than a vague pattern of invasion reports, and included nothing which regarded the Gunpowder Plot, on 21 April he told how Fawkes was to be brought by Tesimond to England. Fawkes was a well-known Flemish mercenary, and would be introduced to "Mr Catesby" and "honourable friends of the nobility and others who would have arms and horses in readiness".{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=150|ps=}} Turner's report did not, however, mention Fawkes's pseudonym in England, John Johnson, and did not reach Cecil until late in November, well after the plot had been discovered.<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/>{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=148–150|ps=}} | |||

| It is uncertain when Fawkes returned to England, but he was back in London by late August 1605, when he and Wintour discovered that the gunpowder stored in the undercroft had decayed. More gunpowder was brought into the room, along with firewood to conceal it.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=170|ps=}} Fawkes's final role in the plot was settled during a series of meetings in October. He was to light the fuse and then escape across the Thames. Simultaneously, a revolt in the Midlands would help to ensure the capture of Princess Elizabeth. Acts of ] were frowned upon, and Fawkes would therefore head to ], where he would explain to the Catholic powers his holy duty to kill the King and his retinue.<ref name="Fraser 1999 178–179">{{Harvnb|Fraser|2005|pp=178–179}}</ref> | |||

| Many popular contemporary verses were written in condemnation of Fawkes. The most well-known verse begins: | |||

| ===Discovery=== | |||

| : “Remember, remember the fifth of November, | |||

| ]]] | |||

| : The gunpowder, treason and plot, | |||

| A few of the conspirators were concerned about fellow Catholics who would be present at Parliament during the opening.{{sfn|Northcote Parkinson|1976|pp=62–63|ps=}} On the evening of 26 October, ] received an anonymous letter warning him to stay away, and to "retyre youre self into yowre contee whence yow maye expect the event in safti for ... they shall receyve a terrible blowe this parleament".{{sfn|Northcote Parkinson|1976|pp=68–69|ps=}} Despite quickly becoming aware of the letter{{spaced ndash}}informed by one of Monteagle's servants{{spaced ndash}}the conspirators resolved to continue with their plans, as it appeared that it "was clearly thought to be a hoax".{{sfn|Northcote Parkinson|1976|p=72|ps=}} Fawkes checked the undercroft on 30 October, and reported that nothing had been disturbed.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=189|ps=}} Monteagle's suspicions had been aroused, however, and the letter was shown to King James. The King ordered ] to conduct a search of the cellars underneath Parliament, which he did in the early hours of 5 November. Fawkes had taken up his station late on the previous night, armed with a slow match and a watch given to him by Percy "becaus he should knowe howe the time went away".<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/> He was found leaving the cellar, shortly after midnight, and arrested. Inside, the barrels of gunpowder were discovered hidden under piles of firewood and coal.{{sfn|Northcote Parkinson|1976|p=73|ps=}} | |||

| : I know of no reason | |||

| : Why gunpowder treason | |||

| : Should ever be forgot.” | |||

| (For the full lyrics see '']'') | |||

| ===Torture=== | |||

| John Rhodes produced a popular narrative in verse describing the events of the plot and condemning Fawkes: | |||

| Fawkes gave his name as John Johnson and was first interrogated by members of the King's ], where he remained defiant.<ref name="NorthcoteParkinsonpp9192">{{Harvnb|Northcote Parkinson|1976|pp=91–92}}</ref> When asked by one of the lords what he was doing in possession of so much gunpowder, Fawkes answered that his intention was "to blow you Scotch beggars back to your native mountains."{{sfn|Cobbett|1857|p=229}} He identified himself as a 36-year-old Catholic from ] in Yorkshire, and gave his father's name as Thomas and his mother's as Edith Jackson. Wounds on his body noted by his questioners he explained as the effects of ]. Fawkes admitted his intention to blow up the House of Lords, and expressed regret at his failure to do so. His steadfast manner impressed King James, who described Fawkes as possessing "a Roman resolution".{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=208–209|ps=}} | |||

| James's respect did not, however, prevent him from ordering on 6 November that "John Johnson" be tortured, to reveal the names of his co-conspirators.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=211|ps=}} He directed that the torture be light at first, referring to the use of ], but more severe if necessary, authorising the use of ]: "the gentler Tortures are to be first used unto him ''et sic per gradus ad ima tenditur'' ".<ref name="NorthcoteParkinsonpp9192"/>{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=215|ps=}} Fawkes was transferred to the ]. The King composed a list of questions to be put to "Johnson", such as "''as to what he is'', For I can never yet hear of any man that knows him", "When and where he learned to speak French?", and "If he was a Papist, who brought him up in it?"{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=212|ps=}} The room in which Fawkes was interrogated subsequently became known as the Guy Fawkes Room.{{sfn|Younghusband|2008|p=46|ps=}} | |||

| : "Fawkes at midnight, and by torchlight there was found | |||

| : With long matches and devices, underground" | |||

| ] | |||

| The full verse was published as ''A brief Summary of the Treason intended against King & State, when they should have been assembled in Parliament, November 5. 1605. Fit for to instruct the simple and ignorant herein: that they not be seduced any longer by Papists''. Other popular verses were of a more religious tone and celebrated the fact that England had been saved from the Guy Fawkes conspiracy. John Wilson published, in 1612, a short song on the "powder plot" with the words: | |||

| ], Lieutenant of the Tower, supervised the torture and obtained Fawkes's confession.<ref name="NorthcoteParkinsonpp9192"/> He searched his prisoner, and found a letter addressed to Guy Fawkes. To Waad's surprise, "Johnson" remained silent, revealing nothing about the plot or its authors.{{sfn|Bengsten|2005|p=58|ps=}} On the night of 6 November he spoke with Waad, who reported to Salisbury "He told us that since he undertook this action he did every day pray to God he might perform that which might be for the advancement of the Catholic Faith and saving his own soul". According to Waad, Fawkes managed to rest through the night, despite his being warned that he would be interrogated until "I had gotton the inwards secret of his thoughts and all his complices".{{sfn|Bengsten|2005|p=59|ps=}} His composure was broken at some point during the following day.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=216–217|ps=}} | |||

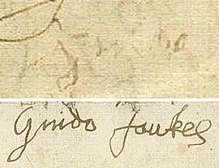

| The observer ] remarked "Since Johnson's being in the Tower, he beginneth to speak English". Fawkes revealed his true identity on 7 November, and told his interrogators that there were five people involved in the plot to kill the King. He began to reveal their names on 8 November, and told how they intended to place Princess Elizabeth on the throne. His third confession, on 9 November, implicated ]. Following the ] of 1571, prisoners were made to dictate their confessions, before copying and signing them, if they still could.{{sfn|Bengsten|2005|p=60|ps=}} Although it is uncertain if he was tortured on the rack, Fawkes's scrawled signature suggests the suffering he endured at the hands of his interrogators.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=215–216, 228–229|ps=}} | |||

| : "O England praise the name of God | |||

| : That kept thee from this heavy rod! | |||

| : But though this demon e'er be gone, | |||

| : his evil now be ours upon!" | |||

| ==Trial and execution== | |||

| The Lord Mayor and aldermen of the City of London commemorated the conspiracy on ] for years after by a sermon in ]. Popular accounts of the plot supplemented these sermons, some of which were published and survive to this day. Many in the city left money in their wills to pay for a minister to preach a sermon annually in their own parish. | |||

| The trial of eight of the plotters began on Monday 27 January 1606. Fawkes shared the barge from the Tower to ] with seven of his co-conspirators.{{efn|The eighth, Thomas Bates, was considered inferior by virtue of his status, and was held instead at Gatehouse Prison.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=263|ps=}}}} They were kept in the ] before being taken to Westminster Hall, where they were displayed on a purpose-built scaffold. The King and his close family, watching in secret, were among the spectators as the Lords Commissioners read out the list of charges. Fawkes was identified as Guido Fawkes, "otherwise called Guido Johnson". He pleaded not guilty, despite his apparent acceptance of guilt from the moment he was captured.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=263–266|ps=none}} | |||

| ], depicting Fawkes's public execution in Westminster]] | |||

| The Fawkes story continued to be celebrated in poetry. The Latin verse ''In Quintum Novembris'' was written c. 1626. ]’s Satan in book six of '']'' was inspired by Fawkes — the Devil invents gunpowder to try to match God's thunderbolts. Post-Reformation and anti–Roman Catholic literature often personified Fawkes as the Devil in this way. From Puritan polemics to popular literature, all sought to associate Fawkes with the demoniacal. | |||

| The jury found all the defendants guilty, and the ] Sir ] pronounced them guilty of ].{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=273|ps=none}} The ] ] told the court that each of the condemned would be ] to his death, by a horse, his head near the ground. They were to be "put to death halfway between heaven and earth as unworthy of both". Their genitals would be cut off and burnt before their eyes, and their bowels and hearts removed. They would then be decapitated, and the dismembered parts of their bodies displayed so that they might become "prey for the fowls of the air".<ref name="Fraserpp266269">{{Harvnb|Fraser|2005|pp=266–269}}</ref> Fawkes's and Tresham's testimony regarding the Spanish treason was read aloud, as well as confessions related specifically to the Gunpowder Plot. The last piece of evidence offered was a conversation between Fawkes and Wintour, who had been kept in adjacent cells. The two men apparently thought they had been speaking in private, but their conversation was intercepted by a government spy. When the prisoners were allowed to speak, Fawkes explained his not guilty plea as ignorance of certain aspects of the indictment.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=269–271|ps=none}} | |||

| On 31 January 1606, Fawkes and three others – Thomas Wintour, ], and ] – were dragged from the Tower on wattled ]s to the ] at Westminster, opposite the building they had attempted to destroy.{{sfn|Haynes|2005|pp=115–116|ps=}} His fellow plotters were then hanged and quartered. Fawkes was the last to stand on the scaffold. He asked for forgiveness of the King and state, while keeping up his "crosses and idle ceremonies" (Catholic practices). Weakened by torture and aided by the hangman, Fawkes began to climb the ladder to the noose, but either through jumping to his death or climbing too high so the rope was incorrectly set, he managed to avoid the agony of the latter part of his execution by ].<ref name="NorthcoteParkinsonpp9192"/>{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=283|ps=}}{{sfn|Sharpe|2005|pp=76–77|ps=}} His lifeless body was nevertheless quartered{{sfn|Allen|1973|p=37|ps=}} and, as was the custom,{{sfn|Thompson|2008|p=102|ps=}} his body parts were then distributed to "the four corners of the kingdom", to be displayed as a warning to other would-be traitors.<ref>{{citation |title=Guy Fawkes |publisher=York Museums Trust |url=http://www.historyofyork.org.uk//themes/tudor-stuart/guy-fawkes |access-date=16 May 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100414012842/http://www.historyofyork.org.uk/themes/tudor-stuart/guy-fawkes |archive-date=14 April 2010 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == In popular culture == | |||

| ].]] | |||

| In 18th-century England, the term "guy" was used to refer to an ] of Fawkes, which would be paraded around town by children on the anniversary of the conspiracy.<ref></ref> It is traditional for children to go door-to-door with their creation asking for a small donation using the term "Penny For The Guy".<ref></ref> In recent years this has attracted controversy as some regard it as nothing more than begging. Whilst it was traditional for children to spend the money raised on fireworks, this is now illegal, as persons under 18 cannot buy fireworks or even be in possession of them in a public place.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| A common phrase is that Fawkes was "the only man to ever enter parliament with honourable intentions".<ref></ref> This phrase may have originated in a 19th-century ], and was commonly seen on ] posters during the early 20th century. The ] became embroiled in controversy when they resurrected the poster with humorous intent in ].<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.struggle.ws/anarchism/writers/anarcho/left/ssp/guyfawkes.html|publisher=Struggle.ws|title=Scottish Socialist Party and Guy Fawkes|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| {{See also|Gunpowder Plot in popular culture|Guy Fawkes mask}} | |||

| Fawkes was ranked 30th in the 2002 list of the '']'', sponsored by the BBC and voted for by the public.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.biographyonline.net/british/greatest-britons.html|publisher=BiographyOnline.net|title=Top 100 Greatest Britons|date=] ]}}</ref> He was also included in a list of the 50 greatest people from Yorkshire.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/uk_news/story/0,3604,1590701,00.html|publisher='']''|title=The 50 greatest Yorkshire people?|date=] ]}}</ref> The ] and thus ] in northern ], ] were named after Fawkes by explorer ], who like Fawkes, was from ]. In the ] a collection of two ] shaped islands and two small rocks north-west of ], are called '']''.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://geology.er.usgs.gov/eespteam/terrainmodeling/images/large/ecuador_srtm_low.pdf|publisher=Geology.er.usgs.gov|title=Topography and Landforms of Ecuador|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| On 5 November 1605, Londoners were encouraged to celebrate the King's escape from assassination by lighting bonfires, provided that "this testemonye of joy be carefull done without any danger or disorder".<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/> ] designated each 5 November as a day of thanksgiving for "the joyful day of deliverance", and remained in force until 1859.<ref name="factsheet">{{citation|author=House of Commons Information Office |url=http://www.parliament.uk/documents/upload/g08.pdf |title=The Gunpowder Plot |date=September 2006 |access-date=15 February 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050215195506/http://www.parliament.uk/documents/upload/g08.pdf |archive-date=15 February 2005 }}</ref> Fawkes was one of 13 conspirators, but he is the individual most associated with the plot.{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=349|ps=}} | |||

| In Britain, 5 November has variously been called ], Guy Fawkes Day, Plot Night,{{sfn|Fox| Woolf|2002|p=269|ps=}} and Bonfire Night (which can be traced directly back to the original celebration of 5 November 1605).{{sfn|Fraser|2005|pp=351–352|ps=}} Bonfires were accompanied by fireworks from the 1650s onwards, and it became the custom after 1673 to burn an effigy (usually of the pope) when heir presumptive ], converted to Catholicism.<ref name="ODNB Fawkes"/> Effigies of other notable figures have found their way onto the bonfires, such as ], ],{{sfn|Fraser|2005|p=356|ps=}} ], ] and ].<ref>{{citation |date=5 November 2022 |title=Lewes bonfire night: Thousands attend annual event |language=en-GB |work=BBC News |url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-sussex-63527177 |accessdate=5 November 2022}}</ref> The "guy" is normally created by children from old clothes, newspapers, and a mask.<ref name="factsheet"/> During the 19th century, "guy" came to mean an oddly dressed person, while in many places it has lost any pejorative connotation and instead refers to any male person and the plural form can refer to people of any gender (as in "]").<ref name="factsheet"/><ref name="mw">{{citation |title=The Merriam-Webster New Book of Word Histories |last=Merriam-Webster |publisher=Merriam-Webster |year=1991 |isbn=0-87779-603-3 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IrcZEZ1bOJsC&pg=PA208|page=208}}, entry "guy"</ref> | |||

| ===Literature=== | |||

| There are several references to Fawkes in popular literature, here are the most noted examples, listed in cronological order. | |||

| *1842: ] - ''Guy Fawkes: A Historical Romance'', is a historical novel which portrayed Fawkes, and Catholic ] in general, in a sympathetic light and began to challenge the official depiction of the plot, one of the first to do so.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Harrison Ainsworth | |||

| | first = William | |||

| | authorlink = William Harrison Ainsworth | |||

| | title =Guy Fawkes: A Historical Romance | |||

| | publisher =Kessinger Publishing | |||

| | url =http://books.google.com/books?hl=en&id=YvcOOnJWc3gC&dq=william+harrison+ainsworth+fawkes&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=eDgfrpTV3h&sig=Wvzti1wdj7OSYbKLCi08P83pAQ0 | |||

| | isbn = 978-1428607347}}</ref> | |||

| *1847: ] - '']'', Jane is compared to Guy Fawkes by Abbot with the line "a sort of infantine Guy Fawkes" because she looked like she was constantly plotting schemes. Brontë herself, like Fawkes, was of ] origins.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.readprint.com/chapter-665/Charlotte-Bronte|publisher=ReadPrint.com|title=Jane Eyre - by Charlotte Bronte: Chapter III|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| *1850: ] - '']'', in order for Peggotty to find money for Saturday's expenses, she "had to prepare a long and elaborate scheme, a very Gunpowder Plot...", directly referencing the Plot Fawkes was involved with.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Dickens | |||

| | first = Charles | |||

| | authorlink = Charles Dickens | |||

| | title =David Copperfield | |||

| | publisher =Penguin Classics | |||

| | url =http://classiclit.about.com/library/bl-etexts/cdickens/bl-cdick-dcopper-10.htm | |||

| | isbn = 978-0140434941}}</ref> | |||

| *1886: ] - '']'', the ] mentions Fawkes in the passage "The ] is the Guy Fawkes prowling in the hid chambers underlying the Claggarts".<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Melville | |||

| | first = Herman | |||

| | authorlink = Herman Melville | |||

| | title =Billy Budd | |||

| | publisher =Chelsea House Publications | |||

| | url =http://books.google.com/books?id=hEnhpPNrZLcC&pg=PA330&dq=guy+fawkes+Herman+Melville&lr=&ei=D8OjR4WzN5G0yQSP4sXZCA&sig=MUz8kZRXMt1UE0exmdCM2U__Vv0 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0791040546}}</ref> | |||

| *1925: ] - '']'', the ] of the ] winning poem directly alludes to Fawkes, "A penny for the Old Guy".<ref>{{cite news|url=http://poetry.poetryx.com/poems/784/|publisher=Poetryx.com|title=T. S. Eliot - The Hollow Men|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| *1953: ] - '']'', the protagonist of the novel is named Guy Montag directly after Guy Fawkes. In the story, the character plans to start burning down the firemen's houses in order to overthrow the government.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.cliffsnotes.com/WileyCDA/LitNote/Fahrenheit-451.id-106,pageNum-16.html|publisher=CliffNotes.com|title=Fahrenheit 451: Summaries and Commentaries - Part One|date=] ]}}</ref> | |||

| *1982: ] - '']'', the ]n ] of a ] ] takes influence from the story of Fawkes. The story revolves around the main character, ], who wears a stylised Guy Fawkes ]. | |||

| *1998: ] - '']'', the ] series headmaster ]'s ] is named ] after the man.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mugglenet.com/books/scholchat2.shtml|title=www.mugglenet.com/books/scholchat2.shtml|title=Scholastic Online Chat Transcript|accessdate=2007-07-15}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Film and music=== | |||

| James Sharpe, professor of history at the University of York, has described how Guy Fawkes came to be toasted as "the last man to enter Parliament with honest intentions".{{sfn|Sharpe|2005|p=6|ps=}} ]'s 1841 historical romance '']'' portrays Fawkes in a generally sympathetic light and his novel transformed Fawkes in the public perception into an "acceptable fictional character".<ref>{{citation |last=Harrison Ainsworth |first=William |authorlink=William Harrison Ainsworth |title=Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder Treason |publisher=Nottingham Society |year=1841 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YvcOOnJWc3gC&pg=PP1}}</ref> Fawkes subsequently appeared as "essentially an action hero" in children's books and ]s such as ''The Boyhood Days of Guy Fawkes; or, The Conspirators of Old London'', published around 1905.<ref name=Sharpe128>{{Harvnb|Sharpe|2005|p=128}}</ref> According to the historian ], Fawkes is now "a major icon in modern political culture", whose face has become "a potentially powerful instrument for the articulation of ]" in the late 20th century.<ref>{{citation |last=Call |first=Lewis |title=A is for Anarchy, V is for Vendetta: Images of Guy Fawkes and the Creation of Postmodern Anarchism |journal=Anarchist Studies |volume=16 |issue=2 |pages=154 |date=July 2008 }}</ref> Fawkes is regarded by some as a ], political rebel<ref name="Nilsen1">{{cite book |last1=Nilsen |first1=Don LF |last2=Nilsen |first2=Alleen Pace |author1-link=Don Nilsen |author2-link=Alleen Pace Nilsen |title=The Language of Humor: An Introduction |date=2018 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-108-41654-2 |pages=185 |edition=1st |url=https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/The_Language_of_Humor/-HWIDwAAQBAJ?gbpv=1&pg=PA185 |language=en |chapter=Literature (14) |doi=10.1017/9781108241403.015}}</ref> or freedom-fighter, especially amongst a minority of Catholics in the United Kingdom.<ref name="guardian1">{{cite web |title=What do Catholics do on Guy Fawkes night? {{!}} Notes and Queries |url=https://www.theguardian.com/notesandqueries/query/0,5753,-18627,00.html |website=] |access-date=6 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230706132929/https://www.theguardian.com/notesandqueries/query/0,5753,-18627,00.html |archive-date=6 July 2023 |language=British English}}</ref> | |||

| There have been various ]s and ]s which focuses on Fawkes and the Gunpowder Plot. Some noted examples are the historic portrays such as the one screened on ] during ], ] named ''Traitors'', which was a one-hour play in the ''Screenplay'' strand about the Plot, written by ]. In 2004 ] screened a two-part serial also written by McGovern, '']'', the second part of which covered the Plot. | |||

| ]'', based on popular depictions of Fawkes.]] | |||

| Other films and television shows have referenced Fawkes in a fictional context; the most noted example of this was when the ] comic was adapted into a ] during 2005, the main character's mask was based on Fawkes. The film gathered large exposure world wide and to date has amounted a ] of $132,511,035.<ref name="boxofficemojo">{{cite web | work=boxofficemojo.com | title=V for Vendetta (2006) | url=http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?page=main&id=vforvendetta.htm | accessmonthday=2 October | accessyear=2006}}</ref> Fawkes is referenced in the 1985 film '']'', as the main character's pet falcon is named after Guy Fawkes. He has also been referenced in television shows such as an ] of '']'', '']'' and the ] special "]". | |||

| ==References== | |||

| Various noted ]al acts and artists have mentioned Fawkes, especially ones from ]. The most famous example of this is on ]'s 1970 solo album '']'', where Lennon sings "Remember, remember, the 5th of November" on the song "]".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.songmeanings.net/lyric.php?lid=3530822107858491837|title=John Lennon - Remember|publisher=SongMeanings.net|accessdate=2007-07-15}}</ref> The vinyl version of ]' album '']'', the words "Guy Fawkes was a genius" are carved near the centre of the record.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.geocities.com/costelt/Lyrics/etching.htm|title=List of etchings|publisher=Etchings on Smiths and Morrissey vinyl|accessdate=2007-07-15}}</ref> Also ]'s song "Commons Brawl" includes the lines "But there again I think for less poor Guy went to the wall, the wrong house but the right idea to end the ] brawl".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.actionext.com/names_j/jethro_tull_lyrics/commons_brawl.html|title=Commons Brawl Lyrics by Jethro Tull|publisher=ActionNext.com|accessdate=2007-07-15}}</ref> | |||

| '''Footnotes''' | |||

| {{Notelist|notes=}} | |||

| '''Citations''' | |||

| == See also == | |||

| {{reflist|30em}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], a Spanish merchant who unsuccessfully tried to assassinate ] in 1582. | |||

| '''Bibliography''' | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{Library resources box}} | |||

| *James I The Kings Book-A True and Perfect Relation of the Whole Proceedings Against the Late Most Barbarous Traitors. Robt. Barker, Printer to the Kings Most Excellent Majesty, British Museum 1606. | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| * {{citation |last=Allen |first=Kenneth |title=The Story of Gunpowder |year=1973 |publisher=Wayland |isbn=978-0-85340-188-9 |url=https://archive.org/details/storyofgunpowder0000alle }} | |||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Bengsten |first=Fiona |title=Sir William Waad, Lieutenant of the Tower, and the Gunpowder Plot |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=89NarZPrQ7sC |edition=illustrated |publisher=Trafford Publishing |year=2005 |isbn=1-4120-5541-5}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Cobbett |first=William |title=A History of the Protestant Reformation in England and Ireland |year=1857 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=rl0JAAAAQAAJ |publisher=Simpkin, Marshall and Company}} | |||

| * {{citation |last1=Fox |first1=Adam |last2=Woolf |first2=Daniel R. |authorlink2=Daniel Woolf |title=The spoken word: oral culture in Britain, 1500–1850 |year=2002 |publisher=Manchester University Press |isbn=0-7190-5747-7}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Fraser |first=Antonia |authorlink=Antonia Fraser |title=The Gunpowder Plot |publisher=Phoenix |year=2005 |origyear=1996 |isbn=0-7538-1401-3}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Haynes |first=Alan |title=The Gunpowder Plot: Faith in Rebellion |publisher=Hayes and Sutton |year=2005 |origyear=1994 |isbn=0-7509-4215-0}} | |||

| * {{citation |first=C. |last=Northcote Parkinson |authorlink=C. Northcote Parkinson |title=Gunpowder Treason and Plot |year=1976 |publisher=Weidenfeld and Nicolson |isbn=0-297-77224-4}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Sharpe |first=J. A. |title=Remember, Remember: A Cultural History of Guy Fawkes Day |publisher=Harvard University Press |year=2005 |edition=illustrated |isbn=0-674-01935-0}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Thompson |first=Irene |title=The A to Z of Punishment and Torture: From Amputations to Zero Tolerance |year=2008 |publisher=Book Guild Publishing |isbn=978-1-84624-203-8}} | |||

| * {{citation |last=Younghusband |first=George |title=A Short History of the Tower of London |year=2008 |publisher=Boucher Press |isbn=978-1-4437-0485-4}} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{sisterlinks|d=Q13898|commons=category:Guy Fawkes|b=no|v=no|s=no|voy=no|mw=no|m=no|species=no|wikt=no|n=no}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| == External links == | |||

| {{commonscat|Guy Fawkes}} | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * , an extensive set of rhymes, often known as Bonfire "prayers" or "chants" which vary by community and location. | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * , a walking trail exploring the Gunpowder Plot and its historical context | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Gunpowder Plot}} | {{Gunpowder Plot}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Fawkes, Guy}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Fawkes, Guy}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 16:21, 9 December 2024

English participant in the 1605 Gunpowder Plot This article is about the historical figure. For other uses, see Guy Fawkes (disambiguation).

| Guy Fawkes | |

|---|---|

A contemporary engraving of Fawkes made in 1605 A contemporary engraving of Fawkes made in 1605 | |

| Born | 13 April 1570 (presumed) York, England |

| Died | 31 January 1606 (aged 35) Westminster, London, England |

| Other names | Guido Fawkes, John Johnson |

| Occupation(s) | Soldier, alférez |

| Criminal status | Executed |

| Parents |

|

| Motive | Gunpowder Plot, a conspiracy to assassinate King James VI and I and members of the Houses of Parliament |

| Conviction(s) | High treason |

| Criminal penalty | Hanged, drawn and quartered |

| Role | Explosives |

| Enlisted | 20 May 1604 |

| Date apprehended | 5 November 1605 |

Guy Fawkes (/fɔːks/; 13 April 1570 – 31 January 1606), also known as Guido Fawkes while fighting for the Spanish, was a member of a group of provincial English Catholics involved in the failed Gunpowder Plot of 1605. He was born and educated in York; his father died when Fawkes was eight years old, after which his mother married a recusant Catholic.

Fawkes converted to Catholicism and left for mainland Europe, where he fought for Catholic Spain in the Eighty Years' War against Protestant Dutch reformers in the Low Countries. He travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England without success. He later met Thomas Wintour, with whom he returned to England. Wintour introduced him to Robert Catesby, who planned to assassinate King James I and restore a Catholic monarch to the throne. The plotters leased an undercroft beneath the House of Lords; Fawkes was placed in charge of the gunpowder that they stockpiled there. The authorities were prompted by an anonymous letter to search Westminster Palace during the early hours of 5 November, and they found Fawkes guarding the explosives. He was questioned and tortured over the next few days and confessed to wanting to blow up the House of Lords.

Fawkes was sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered. However, at his execution on 31 January, he died when his neck was broken as he was hanged, with some sources claiming that he deliberately jumped to make this happen; he thus avoided the agony of his sentence. He became synonymous with the Gunpowder Plot, the failure of which has been commemorated in the UK as Guy Fawkes Night since 5 November 1605, when his effigy is traditionally burned on a bonfire, commonly accompanied by fireworks.

Early life

Childhood

Guy Fawkes was born in 1570 in Stonegate, York. He was the second of four children born to Edward Fawkes, a proctor and an advocate of the consistory court at York, and his wife, Edith. Guy's parents were regular communicants of the Church of England, as were his paternal grandparents; his grandmother, born Ellen Harrington, was the daughter of a prominent merchant, who served as Lord Mayor of York in 1536. Guy's mother's family were recusant Catholics, and his cousin, Richard Cowling, became a Jesuit priest. Guy was an uncommon name in England, but may have been popular in York on account of a local notable, Sir Guy Fairfax of Steeton.

The date of Fawkes's birth is unknown, but he was baptised in the church of St Michael le Belfrey, York on 16 April. As the customary gap between birth and baptism was three days, he was probably born about 13 April. In 1568, Edith had given birth to a daughter named Anne, but the child died aged about seven weeks, in November that year. She bore two more children after Guy: Anne (b. 1572), and Elizabeth (b. 1575). Both were married, in 1599 and 1594 respectively.

In 1579, when Guy was eight years old, his father died. His mother remarried several years later, to the Catholic Dionis Baynbrigge (or Denis Bainbridge) of Scotton, Harrogate. Fawkes may have become a Catholic through the Baynbrigge family's recusant tendencies, and also the Catholic branches of the Pulleyn and Percy families of Scotton, but also from his time at St. Peter's School in York. A governor of the school had spent about 20 years in prison for recusancy, and its headmaster, John Pulleyn, came from a family of noted Yorkshire recusants, the Pulleyns of Blubberhouses. In her 1915 work The Pulleynes of Yorkshire, author Catharine Pullein suggested that Fawkes's Catholic education came from his Harrington relatives, who were known for harbouring priests, one of whom later accompanied Fawkes to Flanders in 1592–1593. Fawkes's fellow students included John Wright and his brother Christopher (both later involved with Fawkes in the Gunpowder Plot) and Oswald Tesimond, Edward Oldcorne and Robert Middleton, who became priests (the latter executed in 1601).

After leaving school Fawkes entered the service of Anthony Browne, 1st Viscount Montagu. The Viscount took a dislike to Fawkes and after a short time dismissed him; he was subsequently employed by Anthony-Maria Browne, 2nd Viscount Montagu, who succeeded his grandfather at the age of 18. At least one source claims that Fawkes married and had a son, but no known contemporary accounts confirm this.

Military career

In October 1591 Fawkes sold the estate in Clifton in York that he had inherited from his father. He travelled to the continent to fight in the Eighty Years War for Catholic Spain against the new Dutch Republic and, from 1595 until the Peace of Vervins in 1598, France. Although England was not by then engaged in land operations against Spain, the two countries were still at war, and the attempted invasion of England, led by the Spanish Armada in 1588, was only five years in the past. He joined Sir William Stanley, an English Catholic and veteran commander in his mid-forties who had raised an army in Ireland to fight in Leicester's expedition to the Netherlands. Stanley had been held in high regard by Elizabeth I, but following his surrender of Deventer to the Spanish in 1587 he, and most of his troops, had switched sides to serve Spain. Fawkes became an alférez or junior officer, fought well at the siege of Calais in 1596, and by 1603 had been recommended for a captaincy. That year, he travelled to Spain to seek support for a Catholic rebellion in England. He used the occasion to adopt the Italian version of his name, Guido, and in his memorandum described James I (who became king of England that year) as "a heretic", who intended "to have all of the Papist sect driven out of England." He denounced Scotland, and the King's favourites among the Scottish nobles, writing "it will not be possible to reconcile these two nations, as they are, for very long". Although he was received politely, the court of Philip III was unwilling to offer him any support.

Gunpowder Plot

Main article: Gunpowder Plot

In 1604 Fawkes became involved with a small group of English Catholics, led by Robert Catesby, who planned to assassinate the Protestant King James and replace him with his daughter, third in the line of succession, Princess Elizabeth. Fawkes was described by the Jesuit priest and former school friend Oswald Tesimond as "pleasant of approach and cheerful of manner, opposed to quarrels and strife ... loyal to his friends". Tesimond also claimed Fawkes was "a man highly skilled in matters of war", and that it was this mixture of piety and professionalism that endeared him to his fellow conspirators. The author Antonia Fraser describes Fawkes as "a tall, powerfully built man, with thick reddish-brown hair, a flowing moustache in the tradition of the time, and a bushy reddish-brown beard", and that he was "a man of action ... capable of intelligent argument as well as physical endurance, somewhat to the surprise of his enemies."

The first meeting of the five central conspirators took place on Sunday 20 May 1604, at an inn called the Duck and Drake, in the fashionable Strand district of London. Catesby had already proposed at an earlier meeting with Thomas Wintour and John Wright to kill the King and his government by blowing up "the Parliament House with gunpowder". Wintour, who at first objected to the plan, was convinced by Catesby to travel to the continent to seek help. Wintour met with the Constable of Castile, the exiled Welsh spy Hugh Owen, and Sir William Stanley, who said that Catesby would receive no support from Spain. Owen did, however, introduce Wintour to Fawkes, who had by then been away from England for many years, and thus was largely unknown in the country. Wintour and Fawkes were contemporaries; each was militant, and had first-hand experience of the unwillingness of the Spaniards to help. Wintour told Fawkes of their plan to "doe some whatt in Ingland if the pece with Spaine healped us nott", and thus in April 1604 the two men returned to England. Wintour's news did not surprise Catesby; despite positive noises from the Spanish authorities, he feared that "the deeds would nott answere".

One of the conspirators, Thomas Percy, was appointed a Gentleman Pensioner in June 1604, gaining access to a house in London that belonged to John Whynniard, Keeper of the King's Wardrobe. Fawkes was installed as a caretaker and began using the pseudonym John Johnson, servant to Percy. The contemporaneous account of the prosecution (taken from Thomas Wintour's confession) claimed that the conspirators attempted to dig a tunnel from beneath Whynniard's house to Parliament, although this story may have been a government fabrication; no evidence for the existence of a tunnel was presented by the prosecution, and no trace of one has ever been found; Fawkes himself did not admit the existence of such a scheme until his fifth interrogation, but even then he could not locate the tunnel. If the story is true, however, by December 1604 the conspirators were busy tunnelling from their rented house to the House of Lords. They ceased their efforts when, during tunnelling, they heard a noise from above. Fawkes was sent out to investigate, and returned with the news that the tenant's widow was clearing out a nearby undercroft, directly beneath the House of Lords.

The plotters purchased the lease to the room, which also belonged to John Whynniard. Unused and filthy, it was considered an ideal hiding place for the gunpowder the plotters planned to store. According to Fawkes, 20 barrels of gunpowder were brought in at first, followed by 16 more on 20 July. On 28 July however, the ever-present threat of the plague delayed the opening of Parliament until Tuesday, 5 November.

Overseas

In an attempt to gain foreign support, in May 1605 Fawkes travelled overseas and informed Hugh Owen of the plotters' plan. At some point during this trip his name made its way into the files of Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury, who employed a network of spies across Europe. One of these spies, Captain William Turner, may have been responsible. Although the information he provided to Salisbury usually amounted to no more than a vague pattern of invasion reports, and included nothing which regarded the Gunpowder Plot, on 21 April he told how Fawkes was to be brought by Tesimond to England. Fawkes was a well-known Flemish mercenary, and would be introduced to "Mr Catesby" and "honourable friends of the nobility and others who would have arms and horses in readiness". Turner's report did not, however, mention Fawkes's pseudonym in England, John Johnson, and did not reach Cecil until late in November, well after the plot had been discovered.

It is uncertain when Fawkes returned to England, but he was back in London by late August 1605, when he and Wintour discovered that the gunpowder stored in the undercroft had decayed. More gunpowder was brought into the room, along with firewood to conceal it. Fawkes's final role in the plot was settled during a series of meetings in October. He was to light the fuse and then escape across the Thames. Simultaneously, a revolt in the Midlands would help to ensure the capture of Princess Elizabeth. Acts of regicide were frowned upon, and Fawkes would therefore head to the continent, where he would explain to the Catholic powers his holy duty to kill the King and his retinue.

Discovery

A few of the conspirators were concerned about fellow Catholics who would be present at Parliament during the opening. On the evening of 26 October, Lord Monteagle received an anonymous letter warning him to stay away, and to "retyre youre self into yowre contee whence yow maye expect the event in safti for ... they shall receyve a terrible blowe this parleament". Despite quickly becoming aware of the letter – informed by one of Monteagle's servants – the conspirators resolved to continue with their plans, as it appeared that it "was clearly thought to be a hoax". Fawkes checked the undercroft on 30 October, and reported that nothing had been disturbed. Monteagle's suspicions had been aroused, however, and the letter was shown to King James. The King ordered Sir Thomas Knyvet to conduct a search of the cellars underneath Parliament, which he did in the early hours of 5 November. Fawkes had taken up his station late on the previous night, armed with a slow match and a watch given to him by Percy "becaus he should knowe howe the time went away". He was found leaving the cellar, shortly after midnight, and arrested. Inside, the barrels of gunpowder were discovered hidden under piles of firewood and coal.

Torture

Fawkes gave his name as John Johnson and was first interrogated by members of the King's Privy chamber, where he remained defiant. When asked by one of the lords what he was doing in possession of so much gunpowder, Fawkes answered that his intention was "to blow you Scotch beggars back to your native mountains." He identified himself as a 36-year-old Catholic from Netherdale in Yorkshire, and gave his father's name as Thomas and his mother's as Edith Jackson. Wounds on his body noted by his questioners he explained as the effects of pleurisy. Fawkes admitted his intention to blow up the House of Lords, and expressed regret at his failure to do so. His steadfast manner impressed King James, who described Fawkes as possessing "a Roman resolution".

James's respect did not, however, prevent him from ordering on 6 November that "John Johnson" be tortured, to reveal the names of his co-conspirators. He directed that the torture be light at first, referring to the use of manacles, but more severe if necessary, authorising the use of the rack: "the gentler Tortures are to be first used unto him et sic per gradus ad ima tenditur ". Fawkes was transferred to the Tower of London. The King composed a list of questions to be put to "Johnson", such as "as to what he is, For I can never yet hear of any man that knows him", "When and where he learned to speak French?", and "If he was a Papist, who brought him up in it?" The room in which Fawkes was interrogated subsequently became known as the Guy Fawkes Room.

Sir William Waad, Lieutenant of the Tower, supervised the torture and obtained Fawkes's confession. He searched his prisoner, and found a letter addressed to Guy Fawkes. To Waad's surprise, "Johnson" remained silent, revealing nothing about the plot or its authors. On the night of 6 November he spoke with Waad, who reported to Salisbury "He told us that since he undertook this action he did every day pray to God he might perform that which might be for the advancement of the Catholic Faith and saving his own soul". According to Waad, Fawkes managed to rest through the night, despite his being warned that he would be interrogated until "I had gotton the inwards secret of his thoughts and all his complices". His composure was broken at some point during the following day.

The observer Sir Edward Hoby remarked "Since Johnson's being in the Tower, he beginneth to speak English". Fawkes revealed his true identity on 7 November, and told his interrogators that there were five people involved in the plot to kill the King. He began to reveal their names on 8 November, and told how they intended to place Princess Elizabeth on the throne. His third confession, on 9 November, implicated Francis Tresham. Following the Ridolfi plot of 1571, prisoners were made to dictate their confessions, before copying and signing them, if they still could. Although it is uncertain if he was tortured on the rack, Fawkes's scrawled signature suggests the suffering he endured at the hands of his interrogators.

Trial and execution

The trial of eight of the plotters began on Monday 27 January 1606. Fawkes shared the barge from the Tower to Westminster Hall with seven of his co-conspirators. They were kept in the Star Chamber before being taken to Westminster Hall, where they were displayed on a purpose-built scaffold. The King and his close family, watching in secret, were among the spectators as the Lords Commissioners read out the list of charges. Fawkes was identified as Guido Fawkes, "otherwise called Guido Johnson". He pleaded not guilty, despite his apparent acceptance of guilt from the moment he was captured.

The jury found all the defendants guilty, and the Lord Chief Justice Sir John Popham pronounced them guilty of high treason. The Attorney General Sir Edward Coke told the court that each of the condemned would be drawn backwards to his death, by a horse, his head near the ground. They were to be "put to death halfway between heaven and earth as unworthy of both". Their genitals would be cut off and burnt before their eyes, and their bowels and hearts removed. They would then be decapitated, and the dismembered parts of their bodies displayed so that they might become "prey for the fowls of the air". Fawkes's and Tresham's testimony regarding the Spanish treason was read aloud, as well as confessions related specifically to the Gunpowder Plot. The last piece of evidence offered was a conversation between Fawkes and Wintour, who had been kept in adjacent cells. The two men apparently thought they had been speaking in private, but their conversation was intercepted by a government spy. When the prisoners were allowed to speak, Fawkes explained his not guilty plea as ignorance of certain aspects of the indictment.

On 31 January 1606, Fawkes and three others – Thomas Wintour, Ambrose Rookwood, and Robert Keyes – were dragged from the Tower on wattled hurdles to the Old Palace Yard at Westminster, opposite the building they had attempted to destroy. His fellow plotters were then hanged and quartered. Fawkes was the last to stand on the scaffold. He asked for forgiveness of the King and state, while keeping up his "crosses and idle ceremonies" (Catholic practices). Weakened by torture and aided by the hangman, Fawkes began to climb the ladder to the noose, but either through jumping to his death or climbing too high so the rope was incorrectly set, he managed to avoid the agony of the latter part of his execution by breaking his neck. His lifeless body was nevertheless quartered and, as was the custom, his body parts were then distributed to "the four corners of the kingdom", to be displayed as a warning to other would-be traitors.

Legacy

See also: Gunpowder Plot in popular culture and Guy Fawkes mask

On 5 November 1605, Londoners were encouraged to celebrate the King's escape from assassination by lighting bonfires, provided that "this testemonye of joy be carefull done without any danger or disorder". An Act of Parliament designated each 5 November as a day of thanksgiving for "the joyful day of deliverance", and remained in force until 1859. Fawkes was one of 13 conspirators, but he is the individual most associated with the plot.

In Britain, 5 November has variously been called Guy Fawkes Night, Guy Fawkes Day, Plot Night, and Bonfire Night (which can be traced directly back to the original celebration of 5 November 1605). Bonfires were accompanied by fireworks from the 1650s onwards, and it became the custom after 1673 to burn an effigy (usually of the pope) when heir presumptive James, Duke of York, converted to Catholicism. Effigies of other notable figures have found their way onto the bonfires, such as Paul Kruger, Margaret Thatcher, Liz Truss, Rishi Sunak and Vladimir Putin. The "guy" is normally created by children from old clothes, newspapers, and a mask. During the 19th century, "guy" came to mean an oddly dressed person, while in many places it has lost any pejorative connotation and instead refers to any male person and the plural form can refer to people of any gender (as in "you guys").

James Sharpe, professor of history at the University of York, has described how Guy Fawkes came to be toasted as "the last man to enter Parliament with honest intentions". William Harrison Ainsworth's 1841 historical romance Guy Fawkes; or, The Gunpowder Treason portrays Fawkes in a generally sympathetic light and his novel transformed Fawkes in the public perception into an "acceptable fictional character". Fawkes subsequently appeared as "essentially an action hero" in children's books and penny dreadfuls such as The Boyhood Days of Guy Fawkes; or, The Conspirators of Old London, published around 1905. According to the historian Lewis Call, Fawkes is now "a major icon in modern political culture", whose face has become "a potentially powerful instrument for the articulation of postmodern anarchism" in the late 20th century. Fawkes is regarded by some as a martyr, political rebel or freedom-fighter, especially amongst a minority of Catholics in the United Kingdom.

References

Footnotes

- Dates in this article before 14 September 1752 are given in the Julian calendar. The beginning of the year is treated as 1 January even though it began in England on 25 March.

- According to one source, he may have been Registrar of the Exchequer Court of the Archbishop.

- Fawkes's mother's maiden name is alternatively given as Edith Blake, or Edith Jackson.

- According to the International Genealogical Index, compiled by the LDS Church, Fawkes married Maria Pulleyn (b. 1569) in Scotton in 1590, and had a son, Thomas, on 6 February 1591. These entries, however, appear to derive from a secondary source and not from actual parish entries.

- Although the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography claims 1592, multiple alternative sources give 1591 as the date. Peter Beal, A Dictionary of English Manuscript Terminology, 1450 to 2000, includes a signed indenture of the sale of the estate dated 14 October 1591. (pp. 198–199)

- Also present were fellow conspirators John Wright, Thomas Percy, and Thomas Wintour (with whom he was already acquainted).

- Philip III made peace with England in August 1604.

- The eighth, Thomas Bates, was considered inferior by virtue of his status, and was held instead at Gatehouse Prison.

Citations

- Haynes 2005, pp. 28–29

- Guy Fawkes, The Gunpowder Plot Society, archived from the original on 18 March 2010, retrieved 19 May 2010

- ^ Nicholls, Mark (2004), "Fawkes, Guy (bap. 1570, d. 1606)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.), Oxford University Press, doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/9230 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- "Fawkes, Guy" in The Dictionary of National Biography, Leslie Stephen, ed., Oxford University Press, London (1921–1922).

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 84

- ^ Sharpe 2005, p. 48

- Fraser 2005, p. 86 (note)

- Sharpe 2005, p. 49

- ^ Herber, David (April 1998), "The Marriage of Guy Fawkes and Maria Pulleyn", The Gunpowder Plot Society Newsletter, The Gunpowder Plot Society, archived from the original on 17 June 2011, retrieved 16 February 2010

- Fraser 2005, pp. 84–85

- Fraser 2005, pp. 85–86

- ^ Fraser 2005, p. 86

- Fraser 2005, p. 89

- Fraser 2005, pp. 87–90

- Northcote Parkinson 1976, p. 46

- Fraser 2005, pp. 140–142

- ^ Fraser 2005, pp. 117–119

- Fraser 2005, p. 87