| Revision as of 21:26, 2 April 2008 editIrpen (talk | contribs)32,604 edits we should not editorialize. If he is not acceptable, he should not be used rather than be characterized here← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:26, 30 November 2024 edit undoMellk (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users61,654 edits Reverted 2 edits by 86.180.70.47 (talk): Unexplained changesTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| (746 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{Totally-disputed|date=March 2008}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] division]] | |||

| During ], ] was a battleground. While it is clear that ] played an important role in the victory over Nazism, during the ] of Ukraine by ] some Ukrainians, predominantly from the West of Ukraine which had only joined the Soviet Union in 1939, chose to collaborate with the Nazis. Their reasons including the hopes for self-rule and dissatisfaction with Soviet control. However, the lack of Ukrainian autonomy under the Nazis, mistreatment by the occupiers, and the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians as ], soon led to a rapid change in the attitude among the collaborators. By the time the ] returned to Ukraine, most of the population welcomed the soldiers as liberators.<ref>Bauer, Yehuda: "" pg. 13-14. Accessed ] ].</ref> Furthermore, more than 4.5 million Ukrainians fought Germany in the Red Army and more than 250,000 as part of the ].<ref>Potichnyj, Peter J.: "". Accessed ] ].</ref> Ukraine also produced noted commanders such as Marshal ] and partisan leader ]. | |||

| '''Ukrainian collaboration with Nazi Germany''' took place during the ] and the ], ], by ] during the ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Markiewicz |first=Paweł |url= |title=Unlikely Allies: Nazi German and Ukrainian Nationalist Collaboration in the General Government During World War II |publisher=Purdue University Press |year=2021 |isbn=978-1-61249-679-5}}</ref> | |||

| ==Attitudes towards German invasion== | |||

| {{weasel}} | |||

| {{Unreferencedsection|date=January 2007}} | |||

| The German invasion of the ] (]) began on ], ], and by September the occupied had set up the first administration including the ]. The Germans had their own plans for Ukraine: it was to become ], allowing for "Aryan" colonisation, and the local population - the Slavs were viewed as ] by the Nazi idealology. | |||

| Many Ukrainians chose to resist, fighting German occupantion forces with ] or ]. However, particularly in the Western Ukraine, loyalty to the Soviet State was low. Although the ] did give the population the national and cultural autonomy that neither the ] nor the interwar ] did, it came at a price. In ] millions of Ukrainians starved to death in an infamous famine, the ] <ref> although many scholars view it as induced or exacerbated by the Soviet government much debate still surround the issue which also is controversial in latter-day Ukraine</ref> and in ] several thousand intelligentsia were exiled, sentenced to ] ]s or executed. The negative impact of Soviet policies helped the Germans win popular support in some regions and some initially viewed the Germans as allies in the struggle to free Ukraine from oppression and achieve independence. In some areas, Ukrainians publicly celebrated the invasion of their homeland by Nazi Germany; the German soldiers were kissed and greeted warmly by Ukrainians in streets.{{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| By September 1941, the German-occupied territory of Ukraine was divided between two new German administrative units, the ] of the Nazi ] and the ]. Some Ukrainians chose to resist and fight the German occupation forces and either joined the ] or the irregular ] units conducting guerrilla warfare against the Germans. Most Ukrainians, especially in ], had little to no loyalty toward the Soviet Union, which had been repressively occupying ] in the interwar years and had overseen a famine in the early 1930s called the ] that killed millions of Ukrainians. Some who worked with or for the Nazis against the Allied forces<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Perks |first=Robert |date=1993 |title=Ukraine's Forbidden History: Memory and Nationalism |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40179315 |journal=Oral History |volume=21 |issue=1 |pages=43–53 |jstor=40179315 |issn=0143-0955|quote=Both occupying regimes imposed their own language and government... For the majority of Ukrainians in the east, Soviet rule was even more repressive}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.thenation.com/article/archive/seven-decades-nazi-collaboration-americas-dirty-little-ukraine-secret/ |title=Seven Decades of Nazi Collaboration: America's Dirty Little Ukraine Secret (An interview with Russ Bellant)|publisher=] |author=Paul H. Rosenberg |date=28 March 2014}}</ref> ] hoped that enthusiastic collaboration would enable them to re-establish an independent state. Many were involved in a series of war crimes and ], including ], and the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Torvey |first=Colin |title=Means, Ends, and Perpetrators: Connections Between the Holocaust and the Genocide of Ethnic Poles in Volhynia and Galicia |url=https://cdr.lib.unc.edu/concern/articles/f7623p616}}</ref> | |||

| ==Under occupation== | |||

| Many Ukrainians collaborated with the German occupiers, participating in the local administration, in German-supervised auxiliary police, ], in the German military, and serving as ] guards. Nationalists in the west of Ukraine were among the most enthusiastic collaborators early on, hoping that their efforts would enable them to establish independent state later on. For example, on the eve of Barbarossa as many as four thousand Ukrainians, operating under ] orders, sought to cause disruption behind Soviet lines. After the capture of ], in important Ukrainian city, ] leaders proclaimed a new Ukrainian State on ], ] and were simultaneously encouraging loyalty to the new regime, in hope that they would be supported by the Germans. Already in 1939, during the German-Polish war, the OUN had been “a faithful German auxiliary”, according to<ref>Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe, by John A. Armstrong in The Journal of Modern History > Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), p. 409</ref> | |||

| Ukrainians, including ethnic minorities like Russians, Tatars and others,<ref>{{Cite news |date=2016-09-29 |title=Historian Timothy Snyder: Babi Yar A Tragedy For All Ukrainians |language=en |work=Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/ukraine-babi-yar-historian-snyder-tragedy-for-all/28022569.html |access-date=2023-05-02 |quote="However, from the very beginning, and that is true, some local residents, Ukrainians -- not only ethnic Ukrainians but also Russians, Tatars, and others -- collaborated. Some people from each ethnic group collaborated."}}</ref> who collaborated with the Nazi Germany did so in various ways including participating in the local administration, in German-supervised auxiliary police, ], in the German military, or as guards in the ]s. | |||

| However, despite initially acting warmly to the idea of an independent Ukraine, the Nazi administration had other ideas, in particular the ] programme and the total 'Aryanisation' of the population. They preferred to play Slavic nations out one against the other. OUN initially carried out attacks on Polish villages, trying to destroy or expel Polish enclaves from what the OUN fighters perceived as Ukrainian territory.<ref> Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe, by John A. Armstrong in The Journal of Modern History > Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), p. 409</ref> When OUN help was no longer needed, its leaders were imprisoned. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| <!--Later, hundreds of members and sympathisers were executed at ]{{Fact|date=April 2007}}. In response to the new realities, the OUN ceased it collaboration and formed the ] in 1942, which quickly grew into a large ] force and proceeded to fight against all foreign militaries in Ukraine, including the Germans{{Fact|date=April 2007}}, the Soviets, and the Poles.--> | |||

| Stalin and Hitler both demanded territory from their immediate neighbour, Poland.<ref name="muse"/> The ] in 1939 brought together Ukrainians of the USSR and Ukrainians of what was then Eastern ] (]), under a single Soviet banner. In the territories of Poland invaded by ], the size of the Ukrainian minority became negligible and was gathered mostly around UCC ({{Interlanguage link|УЦК|uk|Український центральний комітет}}), formed in ].<ref name="TP1997">{{cite book |title=Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947 |author=Tadeusz Piotrowski |publisher=McFarland |year=1997 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NBbnrEMswbUC&q=nationalized&pg=PA11 |chapter=1. Soviet terror |isbn=978-0-7864-2913-4 |pages=11–12}}</ref> | |||

| Less than two years later, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The German ] began on June 22, 1941. Operation Barbarossa brought together native Ukrainians of the USSR and the prewar ]. By September the occupied territory was divided between two new German administrative units: to the southwest, the ] of the Nazi ], and the northeast, ], which stretched all the way to ] by 1943.<ref name="muse"/> | |||

| ==Auxiliary police== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| 109, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 201-st Ukrainian Schutzmannschaftant-battalions participated in anti-partisan operations in Ukraine and Belarus. In February — March 1943 50-th Ukrainian Schutzmannschaftant-battalion participated in the large antiguerrilla action «Winterzauber» (Winter magic) in Belarus, cooperating with several Latvian and 2nd Lithuanian battalion. Schuma-battalions burned down villages suspected in supporting Soviet partisans. (''Gerlach, C. «Kalkulierte Morde» Hamburger Edition, Hamburg, 1999''). | |||

| ] the Liberator" poster in ]]] | |||

| All inhabitants of the village Khatyn in Belarus were burnt alive by the Nazis with participation of Ukrainian collaborators from 118th Schutzmannschaft battalion on 22 March 1943. | |||

| ] noted in a report dated July 9, 1941 "a fundamental difference between the former Polish and Russian territories. In the former Polish region, the Soviet regime was seen as enemy rule... Hence the German troops were greeted by the Polish as well as the ]n population for the most part, at least, as liberators or with friendly neutrality... The situation in the current occupied White Ruthenian areas of the USSR has a completely different basis."<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Life and Terror in Stalin's Russia, 1934–1941|last=Thurston|first=Robert|year=1996}}</ref> | |||

| Ukrainian nationalist partisan leader ] gathered a force of 3,000 in summer 1941 to help the Wehrmacht fight the Red Army. In September 1942, Borovets entered into negotiations with the Soviet partisans of ]. They tried to attract him to the struggle against the Germans but could not reach an agreement. Borovets refused to obey the Soviet command structure and feared German retaliation against Ukrainian civilians. Still, until the spring of 1943 neutrality was maintained between the Borovets detachments and the Soviet partisans.<ref>{{cite book |last=Dziobak |first=V. V. |script-title=uk:Тарас Бульба-Боровець і його військові підрозділи в українському русі Опору (1941—1944) |language=uk |trans-title=Taras Bulba-Borovets and his military units in the Ukrainian Resistance movement (1941—1944) |location=Kiev |publisher=Institute of History of Ukraine |date=2002 |pages=111–119}}</ref> Parallel to the negotiations with the Soviets, Borovets continued to try to reach an agreement with the Germans. In November 1942, he met with ] Puts, the head of the ] of Volhynia and ] general district. | |||

| ==SS Division "Galizien"== | |||

| {{main|14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS Galizien (1st Ukrainian)}} | |||

| In November 1943, during negotiations with the Germans, Borovets was arrested by the ] in Warsaw and incarcerated in ].{{sfn|Dziobak|2002|p=108}} In the autumn of 1944, the Nazis, looking for Ukrainian support in a war they were by then losing, freed Borovets.{{sfn|Dziobak|2002|p=172}} He was forced to change his nom de guerre to ''Kononenko'' and under this name he led the formation of a Ukrainian special forces detachment of around 50 men under the '']''. This detachment was to be dropped in the rear of the ] for guerrilla warfare. Those plans never came to fruition. | |||

| ] division marching in front of the ] (1943).]] | |||

| By ], ] the German Command had created the ] manned by 14,000 Ukrainians. The history, composition, and function of the SS Galizien are the topic of contentious debate among scholars still today. Some have held that these men volunteered eagerly for war against the Soviets allied to Germany<ref>Williamson, G: ''The SS: Hitler's Instrument of Terror''</ref> while others claim that at least some of them were victims of compulsory conscription as Germany suffered defeats and lost manpower on the eastern front.<ref>{{cite book | author=Melnyk, Michael | title=To Battle: The Formation and History of the 14. Gallician SS Volunteer Division | publisher=Helion and Company Ltd}}</ref> Sol Litman of the ] claims that there are many proven and documented incidents of atrocities and massacres committed by the SS Galizien against minorities, particularly Jews during the course of WWII,<ref>{{cite book | author=Litman, Sol | title=Pure Soldiers or Bloodthirsty Murderers?: The Ukrainian 14th Waffen-SS Galicia Division | edition=Hardcover | publisher=Black Rose Books | year=2003| id=ISBN 1551642190}}</ref> however other authors, including Michael Melnyk,<ref>{{cite book | author=Melnyk, Michael | title=To Battle: The Formation and History of the 14. Gallician SS Volunteer Division | publisher=Helion and Company Ltd}}</ref> whose father fought in the Division, and Michael O. Logusz<ref>{{cite book | author=Logusz, Michael | title=Galicia Division: The Waffen-SS 14th grenadier Division 1943-1945 | publisher=Schiffer Publishing}}</ref> maintain that members of the division fought almost entirely at the front against the Soviet Red Army and defend the unit against the accusations made by Litman and others since the war. Neither the division nor any of its members was never formally charged with any war crime. | |||

| At the end of the war Hitler's Ukrainian nationalist allies demanded transfers away from the Eastern Front so that they could surrender to ] rather than Soviet forces. Borovets' detachment surrendered to the Allies on May 10, 1945, and was interned in ] Italy.{{sfn|Dziobak|2002|pp=176—177}}<ref name="muse"/> Because of the fluid nature of these allegiances, historian ] has emphasized that labels such as "collaborators" and "resistance" have been rendered useless in describing the actual loyalty of these groups.<ref name="muse" /> However, in the newly annexed portions of western Ukraine, there was little to no loyalty towards The Soviet Union, whose Red Army had seized Ukraine during the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939. | |||

| ==Occupation== | |||

| {{main|Reichskommissariat Ukraine}} | |||

| Nationalists in western Ukraine hoped that their efforts would enable them to re-establish an independent state later on. For example, on the eve of Operation' Barbarossa, as many as 4,000 Ukrainians, operating under ] orders, sought to cause disruption behind Soviet lines. After the capture of ], a highly-contentious and strategically important city with a significant Ukrainian minority, ] leaders ] on June 30, 1941, and encouraged loyalty to the new regime in the hope that the Germans would support it. In 1939, during the German-Polish War, the OUN was "a faithful German auxiliary".<ref name="J.A.A.">John A. Armstrong, ''Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe'', The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), p. 409.</ref> | |||

| ] ] German high command during the parade in ]]] | |||

| Despite an initial warm reaction to the idea of an independent Ukraine (see ]), the Nazi administration had other ideas, particularly the ] programme and the total ']' of the population. It played the Slavic nations against one another. OUN initially carried out attacks on Polish villages to try to exterminate Polish populations or expel Polish enclaves from what the OUN fighters perceived as Ukrainian territory.<ref name="J.A.A."/> This culminated in the ]. | |||

| According to ], "something that is never said, because it's inconvenient for precisely everyone, is that more Ukrainian Communists collaborated with the Germans, than did Ukrainian nationalists." Snyder also points out that very many of those who collaborated with the German occupation also collaborated with the Soviet policies in the 1930s.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201111224009/http://www.eurozine.com/germans-must-remember-the-truth-about-ukraine-for-their-own-sake/ |date=2020-11-11 }}, ] (7 July 2017)</ref> | |||

| ==Holocaust== | ==Holocaust== | ||

| {{Main|The Holocaust in Ukraine}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The atrocities against the ]ish population during ] took place within a few days of the German occupation. The Ukrainian auxiliary police participated in the ] massacre.<ref> | |||

| The elimination of ] during ] started within a few days of the beginning of the Nazi occupation. The ], which formed mid August 1941,<ref name="JM">{{cite book |author=Jürgen Matthäus |author-link=Jürgen Matthäus |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=x9PTQR93dNsC |title=Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1941–1942 |date=18 April 2013 |publisher=AltaMira Press |page=524 |isbn=978-0-7591-2259-8}}</ref> assisted by ] C, and ] rounded up Jews and undesirables for the ] massacre,<ref name="spector">{{cite encyclopedia|first=Shmuel|last=Spector|title=Extracts from the Babi Yar article|encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of the Holocaust|editor=Israel Gutman|url=http://www.zchor.org/BABIYAR.HTM|publisher=Yad Vashem, Sifriat Hapoalim, Macmillan Publishing Company|year=1990|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121230194729/http://www.zchor.org/BABIYAR.HTM|archive-date=30 December 2012|quote=The implementation of the decision to kill all the Jews of Kiev was entrusted to Sonderkommando 4a. The unit consisted of SD men (Sicherheitsdienst; Security Service) and Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police; Sipo); the third company of the Special Duties Waffen-SS battalion; and a platoon of the No. 9 police battalion. The unit was reinforced by police battalions Nos. 45 and 305 and by units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police.}}</ref> as well as other later massacres in cities and towns of modern-day Ukraine, such as ],<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kac |first=Daniel |title=Fun ash aroysgerufn (Summoned from the Ashes) |publisher=Czytelnik |year=1983 |location=Warsaw, Poland |pages=135–158 |language=Yiddish |chapter=Perl Tine Reports}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Kołki |url=https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/untold-stories/community/14622104-Ko%c5%82ki |website=Yad Vachem |access-date=2023-09-27 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143106/https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/untold-stories/community/14622104-Ko%C5%82ki |url-status=live }}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|last1=Ganuz|first1=I.|last2=Peri|first2=J.|url=http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/stepan/stee009.html|title=The Generations of Stepan: The History of Stepan and Its Jewish Population|publisher=jewishgen.org|date=28 May 2006|access-date=25 May 2016|archive-date=6 September 2024|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143104/https://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/stepan/stee009.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Stepan |url=http://www.jewishheritage.org.ua/en/6352/stepan.html |website=Faina Petryakova Science Center for Judaica and Jewish Art |access-date=2023-09-27 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143107/http://www.jewishheritage.org.ua/en/6352/stepan.html |url-status=live }}</ref> ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/holocaust/timeline/timeline_40.asp|title=The Holocaust Timeline: 1941 - July 25 Pogrom in Lvov/June 30 Germany occupies Lvov; 4,000 Jews killed by July 3/June 30 Einsatzkommando 4a and local Ukrainians kill 300 Jews in Lutsk/September 19 Zhitomir Ghetto liquidated; 10,000 killed|publisher=yadvashem.org|access-date=26 May 2016|archive-date=15 July 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180715001155/http://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/holocaust/timeline/timeline_40.asp}}</ref> | |||

| "The implementation of the decision to kill all the Jews of Kiev was entrusted to Sonderkommando 4a. This unit consisted of SD (Sicherheitsdienst; Security Service) and Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police; Sipo) men; the third company of the Special Duties Waffen-SS battalion; and a platoon of the No. 9 police battalion. The unit was reinforced by police battalions Nos. 45 and 305 and by units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police." (, Encyclopedia of the Holocaust, Israel Gutman, editor in Chief, Yad Vashem, Sifriat Hapoalim, MacMillan Publishing Company,1990)</ref><ref>"The Ukrainians led them past a number of different places where one after the other they had to remove their luggage, then their coats, shoes and overgarments and also underwear. They also had to leave their valuables in a designated place. There was a special pile for each article of clothing. It all happened very quickly and anyone who hesitated was kicked or pushed by the Ukrainians to keep them moving." ()</ref> | |||

| and in other Ukrainian cities and towns, such as ],<ref></ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ],<ref></ref> | |||

| and ].<ref></ref> On September 1, 1941, Nazi-controlled Ukrainian newspaper ''Volhyn'' wrote "The element that settled our cities (Jews)... must disappear completely from our cities. The Jewish problem is already in the process of being solved."<ref></ref> | |||

| During this period, on 1 September 1941, the Nazi-sponsored Ukrainian newspaper ''Volhyn'' wrote, in an article titled Zavoiovuimo misto" (Let's Conquer the City): | |||

| In May 2006, a Ukrainian newspaper ''Ukraine Christian News'' commented: "Carrying out the massacre was the Einsatzgruppe C, supported by members of a Waffen-SS battalion and units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, under the general command of Friedrich Jeckeln. The participation of Ukrainian collaborators in these events, now documented and proven, is a matter of painful public debate in Ukraine."<ref> (Ukraine Christian News, May 3, 2006) Accessed January 14, 2006</ref>. Among others, about 621 members of ] (]) were executed in Babi Yar, including the Ukrainian poet ]. | |||

| <blockquote>"All elements that reside in our land, whether they are Jews or Poles, must be ]. We are at this very moment resolving ], and this ] is part of the plan for the Reich's total reorganization of Europe.",<ref>{{Cite book |last=Burds |first=Jeffrey |title=Holocaust in Rovno |publisher=Palgrave McMillan |year=2013 |isbn=9781137388391 |pages=39 |language=english}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Messina |first=Adele Valeria |title=American Sociology and Holocaust Studies The Alleged Silence and the Creation of the Sociological Delay |publisher=Academic Studies Press |year=2017 |isbn=9781618115478 |pages=176, 177}} | |||

| The most notorious figures among the Ukrainian nationalists who were personally responsible for mass executions were ], head of the so-called Bukovyna battalion (later split into several Schutzmannschaft battalions) and his aide ], head of Kiev ], later head of a Schutzmannschaft battalion. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Spector |first=Shmuel |title=The Jews of Volynia and their reaction to extermination |publisher=Yad Vashem |pages=160}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Basic Historical Narrative of the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center |year=2018 |location=Kyiv Ukraine |pages=114}}</ref> "The empty space that will be created, must immediately and irrevocable be filled by the real owners and masters of this land, the Ukrainian people".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Shkandrij |first=Myroslav |title=Ukrainian Nationalism |publisher=Yale University Press |year=2015 |isbn=9780300206289 |pages=242 |chapter=10}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Gilbert |first=Martin |title=The Holocaust: The Human Tragedy |publisher=RosettaBooks LLC |year=1985 |isbn=9780795337192 |pages=199}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ===Righteous Among the Nations in Ukraine=== | |||

| Reinforced by religious prejudice, antisemitism turned violent in the first days of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Some Ukrainians derived nationalist resentment from the belief that the Jews had worked for Polish landlords.<ref name="War, Richard J p. 223"/> The ] by the Soviet secret police while they retreated eastward were blamed on Jews. The ] of ] provided justification for the revenge killings by the ultranationalist ], which accompanied German '']'' moving east.<ref name="War, Richard J p. 223">{{cite book |title=The Third Reich at War: 1939-1945 |author=Richard J. Evans |author-link=Richard J. Evans |publisher=Penguin Books |location=London |year=2009 |pages=203–223 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WjoiVWGQ9HYC&q=Brzezany+Lemberg&pg=PT203 |isbn=978-1-101-02230-6 |access-date=2020-11-05 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143109/https://books.google.com/books?id=WjoiVWGQ9HYC&q=Brzezany+Lemberg&pg=PT203#v=snippet&q=Brzezany%20Lemberg&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> In ] (prewar Borysław, Poland, population 41,500), the SS commander gave an enraged crowd, which had seen bodies of men murdered by NKVD and laid out in the town square, 24 hours to act as they wished against ], who were forced to clean the dead bodies and to dance and then were killed by beating with axes, pipes etc. The same type of mass murders took place in ]. During ], 7,000 Jews were murdered by Ukrainian nationalists, led by the ].<ref name="War, Richard J p. 223"/><ref>Jakob Weiss, ''Lemberg Mosaic'', p. 173. {{ISBN|0-9831091-1-7}}.</ref><ref>Lucy S. Dawidowicz (1975), ''The War Against the Jews 1933-1945'', Bantam Books Inc., New York, p. 171.</ref> As late as 1945, Ukrainian militants were still rounding up and murdering Jews.<ref>''The Holocaust Chronicle, A History in Words and Pictures'', Edited by David J. Hogan, Publications International Ltd, Lincolnwood, Illinois, p.592</ref> | |||

| While some of the collaborators were civilians, others were given a choice to enlist for paramilitary service beginning in September 1941 from the Soviet prisoner-of-war camps because of ongoing close relations with the Ukrainian ''Hilfsverwaltung''.<ref name="Eikel">{{cite book |author=Markus Eikel |chapter=The local administration under German occupation in central and eastern Ukraine, 1941–1944 |at=110–122 in PDF |title=The Holocaust in Ukraine: New Sources and Perspectives |quote=Ukraine differs from other parts of the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union, whereas the local administrators have formed the ''Hilfsverwaltung'' in support of extermination policies in 1941 and 1942, and in providing assistance for the deportations to camps in Germany, mainly in 1942 and 1943. |publisher=Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum |year=2013 |url=http://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20130500-holocaust-in-ukraine.pdf |access-date=2016-04-20 |archive-date=2021-03-15 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210315093728/https://www.ushmm.org/m/pdfs/20130500-holocaust-in-ukraine.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> In total, over 5,000 native Ukrainian soldiers of the Red Army signed up for training with the SS at a special ] to assist with the ].<ref name="Black">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M7KbsHLnbwgC&q=Hamburg%2C++Karl++Streibel&pg=PA331 |chapter=Police Auxiliaries for Operation Reinhard |author=Peter R. Black |title=Secret Intelligence and the Holocaust |publisher=Enigma Books |year=2006 |editor=David Bankir |pages=331–348 |isbn=1-929631-60-X |via=Google Books |access-date=2020-11-05 |archive-date=2023-03-17 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230317071120/https://books.google.com/books?id=M7KbsHLnbwgC&q=Hamburg%2C++Karl++Streibel&pg=PA331 |url-status=live }}</ref> Another 1,000 defected during field operations.<ref name="Black"/> ] took a major part in the Nazi plan to exterminate European Jews during ]. They served at all ]s and played an important role in the annihilation of the ] (see the ]) and the ] among other ghetto insurgencies.<ref name="Arad-22">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QpAgHYTPRz0C&q=Treblinka+guards+were+Volksdeutsche&pg=PA21 |title=Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps |author=Yitzhak Arad |author-link=Yitzhak Arad |publisher=] |year=1987 |isbn=0-253-34293-7 |page=21 |access-date=2020-11-05 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143230/https://books.google.com/books?id=QpAgHYTPRz0C&q=Treblinka+guards+were+Volksdeutsche&pg=PA21 |url-status=live }}</ref> The men who were dispatched to death camps and Jewish ghettos as guards were never fully trusted and so were always overseen by '']''.<ref name="Procknow">{{cite book |author=Gregory Procknow |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=iVnCbDAKTe4C&q=Treblinka+guards+were+Volksdeutsche&pg=PA35 |title=Recruiting and Training Genocidal Soldiers |publisher=Francis & Bernard Publishing |year=2011 |isbn=978-0-9868374-0-1 |page=35 |access-date=2020-11-05 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143116/https://books.google.com/books?id=iVnCbDAKTe4C&q=Treblinka+guards+were+Volksdeutsche&pg=PA35#v=onepage&q=Treblinka%20guards%20were%20Volksdeutsche&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> Occasionally, along with the prisoners they were guarding, they would kill their commanders in the process of attempting to defect.<ref name="Frankel1998">{{cite book|first=John-Paul|last=Himka|author-link=John-Paul Himka|editor=Jonathan Frankel|title=Studies in Contemporary Jewry: Volume XIII: The Fate of the European Jews, 1939-1945: Continuity or Contingency?|url=http://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje16/text11.htm|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120106044835/http://www.zwoje-scrolls.com/zwoje16/text11.htm|archive-date=January 6, 2012|volume=XIII|year=1998|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-511931-2|pages=170–190|chapter=Ukrainian Collaboration in the Extermination of the Jews During World War II: Sorting out the Long-Term and Conjunctural Factors}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/belzec1/bel041.html|title=Belzec: Stepping Stone to Genocide, Chapter 4 – cont.|publisher=JewishGen, Inc.|date=February 13, 2008|access-date=May 7, 2016|archive-date=October 29, 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029001313/http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/belzec1/bel041.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| According to ], 2185 righteous Ukrainians had been identified by the year 2007.<ref></ref> These are the people, who risked their lives to save the Jews.<ref>Ukrainian Righteous among the nations. Myron B. Kuropas. .</ref> | |||

| ], sign in the background says "Herzlich Willkommen, Heil Hitler"]] | |||

| During his visit to ] ] raised one of the righteous - Father ] to the honours of the Altar for his sacrifice while saving innocent people from death. In ] father Kovtch began to baptize Jews in large numbers in attempt to save their lives. In doing so, he broke the Nazi prohibitions and so he was arrested in December ]. In August of ], for helping Jews he was deported to the ] concentration camp where he was killed and burned in the camp's ovens for his courageous attempt to save lives.<ref>Pope to glorify Ukrainian Priest who saved Jews during the Holocaust. Dr. Alexander Roman. </ref> | |||

| In May 2006, the Ukrainian newspaper ''Ukraine Christian News'' commented, "Carrying out the massacre was the Einsatzgruppe C, supported by members of a Waffen-SS battalion and units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, under the general command of ]. The participation of Ukrainian collaborators in these events, now documented and proven, is a matter of painful public debate in Ukraine".<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061114082404/http://www.invictory.org.ua/article2.html |date=2006-11-14 }} (Ukraine Christian News, May 3, 2006) Accessed January 14, 2006.</ref> | |||

| ==Collaborating organizations, political movements, individuals and military volunteers== | |||

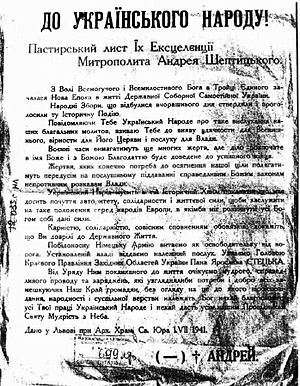

| The most famous instances of the saving of hundreds of Jews during WWII features the ] of the ], ]. He harbored hundreds of Jews in his residence and in Greek Catholic monasteries. He also issued the pastoral letter, "Thou Shalt Not Kill," to protest ]. | |||

| In total, the Germans enlisted 250,000 native Ukrainians for duty in five separate formations including the Nationalist Military Detachments (VVN), the Brotherhoods of Ukrainian Nationalists (DUN), the ], the ] (UVV) and the ] (''Ukrainische Nationalarmee'', UNA).<ref name="muse">{{cite journal |publisher=Project Muse |title=Civil Wars in the Soviet Union |author=Alfred J. Rieber |pages=133, 145–147 |journal=Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History |url=http://www.spranceana.com/uploads/2012/12/4.1rieber.pdf |year=2003 |volume=4 |issue=1 |doi=10.1353/kri.2003.0012 |s2cid=159755578 |access-date=2016-04-11 |archive-date=2020-10-30 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030005123/http://www.spranceana.com/uploads/2012/12/4.1rieber.pdf |url-status=dead }} Slavica Publishers.</ref><ref name="GM">{{cite journal|first=Grzegorz|last=Motyka|author-link=Grzegorz Motyka|url=http://www.ipn.gov.pl/biuletyn/1/inf_aktual_ss_galizien.html|title=Dywizja SS 'Galizien'|trans-title=SS Division 'Galicia'|language=pl|journal=Pamięć I Sprawiedliwość|publisher=Biuletyn IPN|volume=1|date=February 2001|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030103014426/http://www.ipn.gov.pl/biuletyn/1/inf_aktual_ss_galizien.html|archive-date=3 January 2003}}</ref> By the end of 1942, in Reichskommissariat Ukraine alone, the SS employed 238,000 native Ukrainian police and 15,000 Germans, a ratio of 1 to 16.<ref name="JB201324-25">{{cite book | title=Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941 | author=Jeffrey Burds | publisher=Springer | year=2013 | pages=24–25 | isbn=978-1-137-38840-7 | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lkVGAgAAQBAJ&q=238%2C000+native | access-date=2020-09-19 | archive-date=2024-09-06 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143110/https://books.google.com/books?id=lkVGAgAAQBAJ&q=238%2C000+native#v=snippet&q=238%2C000%20native&f=false | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Auxiliary police=== | |||

| ] unit in ], near ]]] | |||

| {{main|Ukrainian Auxiliary Police}} | |||

| The 109th, 114th, 115th, 116th, 117th, ], ] Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft-battalions participated in ] in Ukraine and ]. In February and March 1943, the 50th Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft Battalion participated in the large anti-guerrilla action «]» (Winter magic) in ], cooperating with several Latvian and the ]. Schuma-battalions burned down villages suspected of supporting ] ].<ref>Gerlach, C. "Kalkulierte Morde" Hamburger Edition, Hamburg, 1999.</ref> On March 22, 1943, all inhabitants of the village of ] in Belarus were burned alive by the Nazis in what became known as the ], with the participation of the ].<ref>State Memorial Complex "Khatyn" official web-page https://khatyn.by/en/genocide/expeditions/ {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211130163810/http://www.khatyn.by/en/genocide/expeditions/ |date=2021-11-30 }} - The destruction of the village of Khatyn is a tragic and vivid example. The village was annihilated by the thugs from the 118th Police Battalion, which was stationed in a small town of Pleschinitsy, and by the thugs from the SS battalion "Dirlewanger", which was stationed in Logoisk.</ref><ref>В.И. Адамушко "Хатынь. Трагедия и память НАРБ 2009 {{ISBN|978-985-6372-62-2}}</ref> | |||

| According to Paul R. Magocsi, "''Ukrainian auxiliary police and militia, or simply "Ukrainians" (a generic term that in fact included persons of non-Ukrainian as well as Ukrainian national background) participated in the overall process as policemen and camp guards''".<ref name="rpmag1">{{cite book |last=Magocsi |first=Paul Robert |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=t124cP06gg0C&q=A+History+of+Ukraine |title=A History of Ukraine |publisher=University of Toronto Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-8020-7820-9 |edition=2nd |location=Toronto |pages=678 |access-date=2023-02-28 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143111/https://books.google.com/books?id=t124cP06gg0C&q=A+History+of+Ukraine#v=snippet&q=A%20History%20of%20Ukraine&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Ukrainian volunteers in the German armed forces=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] 3 and 4 {{citation needed|date=December 2022}} | |||

| === SS Division Galicia === | |||

| {{main|14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Ukrainian)}} | |||

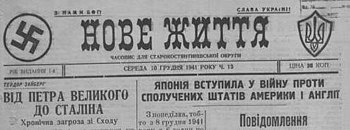

| ]". The headlines read: "From ] to ] – the Eastern Menace" and "] declares war on the ] and ]"]] | |||

| On 28 April 1943, the German Governor of the ], ], and the local Ukrainian administration officially declared the creation of the ]. Volunteers signed for service as of 3 June 1943 and numbered 80,000.<ref>K.G. Klietmann Die Waffen SS; eine Dokumentation Osnabruck Der Freiwillige, 1965 p.194</ref> On 27 July 1944, the division was formed into the ] as ].<ref name="landstreitkrafte313">GEORG TESSIN Verbande und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945 DRITTER BAND: Die Landstreitkrafte 6—14 VERLAG E. S. MITTLER & SOHN GMBH. • FRANKFURT/MAIN {{ISBN|3-7648-0942-6}} page 313</ref> | |||

| Sol Litman of the ] states that there are many proven and documented incidents of atrocities and massacres committed by the unit against Poles and Jews during World War II.<ref>{{cite book | author=Litman, Sol | title=Pure Soldiers or Bloodthirsty Murderers?: The Ukrainian 14th Waffen-SS Galicia Division | edition=Hardcover | publisher=Black Rose Books | year=2003| isbn=1-55164-219-0}}</ref> Official SS records show that the 4, 5, 6 and 7 SS-Freiwilligen regiments were under ] command during the accusations.<ref name="landstreitkrafte313"/><ref>Tessin, Georg / Kannapin, Norbert. Waffen-SS und Ordnungspolizei im Kriegseinsatz 1939-1945.{{ISBN|3-7648-2471-9}} p.52.</ref> See ]. | |||

| ===Ukrainian National Committee=== | |||

| {{main|Ukrainian National Committee}} | |||

| In March 1945, the Ukrainian National Committee was set up after a series of negotiations with the Germans. The Committee represented and had command over all Ukrainian units fighting for the Third Reich, such as the ]. However, it was too late, and the committee and the army were disbanded at the end of the war. | |||

| ===Ukrainian Central Committee=== | |||

| ] became the head of the National Committee, while ], the head of the {{ill|Ukrainian Central Committee|pl|Ukraiński Komitet Centralny|ru|Украинский центральный комитет|uk|Український центральний комітет}}, became his deputy. The Central Committee was the officially recognized Ukrainian community and quasi-political organization under the ]. | |||

| ===Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists=== | |||

| * ] of the Ukrainian State, led by OUN-B. Suppressed by the Nazis shortly after its establishment. | |||

| ===Heads of local Ukrainian administration and public figures under the German occupation=== | |||

| * ] (1899–1992) in the fall of 1941, Ohloblyn was appointed the Mayor of Kiev at the behest of the ]. He held the post from September 21 to October 25.<ref name="Plokhy">{{cite book |last1=Plokhy |first1=Serhii |title=The Cossack Myth: History and Nationhood in the Age of Empires |date=2012 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-13953-673-8 |pages=110–111 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qK4gAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA110 |access-date=2022-04-20 |archive-date=2024-09-06 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240906143111/https://books.google.com/books?id=qK4gAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA110#v=onepage&q&f=false |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| * ] (Kiev mayor, 1941–1942,<ref name="Routledge">{{Cite book |title=The Routledge Handbook to Music under German Occupation, 1938-1945: Propaganda, Myth and Reality |publisher=Routledge |year=2019 |isbn=978-1-351-86258-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nmPBDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT74 |editor-last=David Fanning, Erik Levi |editor-first=}}</ref> | |||

| * Leontii Forostivsky (Kiev mayor, 1942–1943)<ref>{{Cite book |title=Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule |last=Berkhoff |first=Karel C. |publisher=Harvard University Press |year=2008 |isbn=978-0-674-02078-8 |pages=151}}</ref><!-- this reference verified --> | |||

| * ] (head of the Ukrainian Red Cross, 1941–1942) | |||

| * Oleksii Kramarenko (Kharkov mayor, 1941–1942, executed by Germans in 1943) | |||

| * Oleksander Semenenko (Kharkov mayor, 1942–1943) | |||

| * Paul Kozakevich (Kharkov mayor, 1943) | |||

| * Aleksandr Sevastianov (Vinnytsia mayor, 1941 – ?) | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| * ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| {{See also|Bibliography of the Soviet Union during World War II|Bibliography of Ukrainian history#World War II}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Andrew Gregorovich | title=The Ukrainian Experience in World War II With a Brief Survey of Ukraine's Population Loss of 10 Million |edition=Electronic Reprint Edition | publisher=Forum | year=1995 }} | |||

| * Armstrong, J. A. (1968). Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe. ''The Journal of Modern History'', '''40'''(3), pp. 396–410. | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Gilbert Martin | title=The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War | edition=Reprint Edition | publisher=Owl Books | year=1987| id=ISBN 978-0805003482}} | |||

| *{{cite book | |

* {{cite book | vauthors=((Dean, M.)) | date=31 December 1999 | title=Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941-44 | publisher=Palgrave Macmillan | isbn=978-0-312-22056-3}} | ||

| * {{cite book | author=Gilbert Martin | title=The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War | edition=Reprint | publisher=Owl Books | year=1987 | isbn=978-0-8050-0348-2 | url-access=registration | url=https://archive.org/details/holocausthistory0000gilb}} | |||

| * Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe, by John A. Armstrong in The Journal of Modern History > Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), pp. 396-410 | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Gilbert Martin | title=The Holocaust: The Jewish tragedy | edition=Unknown Binding | publisher=Collins | year=1986 | isbn=978-0-00-216305-7 | url-access=registration | url=https://archive.org/details/holocaustjewisht0000gilb}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Mordecai Paldiel| title=The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust| publisher=KTAV Publishing House in association with the ]| year=1993| id=ISBN 0881253766 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Goldenshteyn, M.)) | date=12 December 2021 | title=So They Remember: A Jewish Family's Story of Surviving the Holocaust in Soviet Ukraine | publisher=Oxford University Press}} | |||

| *{{cite book | author=Mordecai Paldiel and ]| title=The Righteous Among the Nations: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust | publisher=HarperCollins Publishers| year=2007| id=ISBN 0061151122 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Lower, W.)) | date=19 September 2005 | title=Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine | publisher=The University of North Carolina Press}} | |||

| * {{cite book| author=Mordecai Paldiel| title=The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust| publisher=KTAV Publishing House in association with the ]| year=1993| isbn=0-88125-376-6| url-access=registration| url=https://archive.org/details/pathofrighteousg00pald}} | |||

| * {{cite book | author=Mordecai Paldiel and ]| title=The Righteous Among the Nations: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust | publisher=HarperCollins Publishers| year=2007| isbn=978-0-06-115112-5}} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1= Дзьобак|first1=Володимир | url=https://ssu.gov.ua/sbu/doccatalog/document?id=42832 |title= Тарас Боровець і "Поліська Січ" |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20120311095841/http://www.ssu.gov.ua/sbu/doccatalog/document?id=42832 |journal= З архівів ВУЧК-ГПУ-НКВД-КГБ|volume= 1/2(2/3)|date= 1995|archive-date=March 11, 2012}} {{LCC|JN6635.A55 I679}} | |||

| * {{cite book | vauthors=((Steinhart, E. C.)) | date=9 February 2015 | title=The Holocaust and the Germanization of Ukraine | publisher=Cambridge University Press}} | |||

| * {{cite book | veditors=((Zabarko, B.)) | date=30 November 2004 | title=Holocaust in the Ukraine | publisher=Vallentine Mitchell}} | |||

| {{SS organizations}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Collaboration with Axis Powers}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Ukrainian Collaboration With Nazi Germany}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:26, 30 November 2024

Ukrainian collaboration with Nazi Germany took place during the occupation of Poland and the Ukrainian SSR, USSR, by Nazi Germany during the Second World War.

By September 1941, the German-occupied territory of Ukraine was divided between two new German administrative units, the District of Galicia of the Nazi General Government and the Reichskommissariat Ukraine. Some Ukrainians chose to resist and fight the German occupation forces and either joined the Red Army or the irregular partisan units conducting guerrilla warfare against the Germans. Most Ukrainians, especially in western Ukraine, had little to no loyalty toward the Soviet Union, which had been repressively occupying eastern Ukraine in the interwar years and had overseen a famine in the early 1930s called the Holodomor that killed millions of Ukrainians. Some who worked with or for the Nazis against the Allied forces Ukrainian nationalists hoped that enthusiastic collaboration would enable them to re-establish an independent state. Many were involved in a series of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including the Holocaust in Ukraine, and the massacres of Poles in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

Ukrainians, including ethnic minorities like Russians, Tatars and others, who collaborated with the Nazi Germany did so in various ways including participating in the local administration, in German-supervised auxiliary police, Schutzmannschaft, in the German military, or as guards in the concentration camps.

Background

Stalin and Hitler both demanded territory from their immediate neighbour, Poland. The Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 brought together Ukrainians of the USSR and Ukrainians of what was then Eastern Poland (Kresy), under a single Soviet banner. In the territories of Poland invaded by Nazi Germany, the size of the Ukrainian minority became negligible and was gathered mostly around UCC (УЦК [uk]), formed in Kraków.

Less than two years later, Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union. The German Operation Barbarossa began on June 22, 1941. Operation Barbarossa brought together native Ukrainians of the USSR and the prewar territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union. By September the occupied territory was divided between two new German administrative units: to the southwest, the District of Galicia of the Nazi General Government, and the northeast, Reichskommissariat Ukraine, which stretched all the way to Donbas by 1943.

Reinhard Heydrich noted in a report dated July 9, 1941 "a fundamental difference between the former Polish and Russian territories. In the former Polish region, the Soviet regime was seen as enemy rule... Hence the German troops were greeted by the Polish as well as the White Ruthenian population for the most part, at least, as liberators or with friendly neutrality... The situation in the current occupied White Ruthenian areas of the USSR has a completely different basis."

Ukrainian nationalist partisan leader Taras Bulba-Borovets gathered a force of 3,000 in summer 1941 to help the Wehrmacht fight the Red Army. In September 1942, Borovets entered into negotiations with the Soviet partisans of Dmitry Medvedev. They tried to attract him to the struggle against the Germans but could not reach an agreement. Borovets refused to obey the Soviet command structure and feared German retaliation against Ukrainian civilians. Still, until the spring of 1943 neutrality was maintained between the Borovets detachments and the Soviet partisans. Parallel to the negotiations with the Soviets, Borovets continued to try to reach an agreement with the Germans. In November 1942, he met with Obersturmbannführer Puts, the head of the security service of Volhynia and Podolia general district.

In November 1943, during negotiations with the Germans, Borovets was arrested by the Gestapo in Warsaw and incarcerated in Sachsenhausen concentration camp. In the autumn of 1944, the Nazis, looking for Ukrainian support in a war they were by then losing, freed Borovets. He was forced to change his nom de guerre to Kononenko and under this name he led the formation of a Ukrainian special forces detachment of around 50 men under the Waffen-SS. This detachment was to be dropped in the rear of the Red Army for guerrilla warfare. Those plans never came to fruition.

At the end of the war Hitler's Ukrainian nationalist allies demanded transfers away from the Eastern Front so that they could surrender to Allies rather than Soviet forces. Borovets' detachment surrendered to the Allies on May 10, 1945, and was interned in Rimini Italy. Because of the fluid nature of these allegiances, historian Alfred Rieber has emphasized that labels such as "collaborators" and "resistance" have been rendered useless in describing the actual loyalty of these groups. However, in the newly annexed portions of western Ukraine, there was little to no loyalty towards The Soviet Union, whose Red Army had seized Ukraine during the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939.

Occupation

Main article: Reichskommissariat UkraineNationalists in western Ukraine hoped that their efforts would enable them to re-establish an independent state later on. For example, on the eve of Operation' Barbarossa, as many as 4,000 Ukrainians, operating under Wehrmacht orders, sought to cause disruption behind Soviet lines. After the capture of Lviv, a highly-contentious and strategically important city with a significant Ukrainian minority, OUN leaders proclaimed a new Ukrainian State on June 30, 1941, and encouraged loyalty to the new regime in the hope that the Germans would support it. In 1939, during the German-Polish War, the OUN was "a faithful German auxiliary".

Despite an initial warm reaction to the idea of an independent Ukraine (see Ukrainian national government (1941)), the Nazi administration had other ideas, particularly the Lebensraum programme and the total 'Aryanisation' of the population. It played the Slavic nations against one another. OUN initially carried out attacks on Polish villages to try to exterminate Polish populations or expel Polish enclaves from what the OUN fighters perceived as Ukrainian territory. This culminated in the mass killings of Polish families in Volhynia and Eastern Galicia.

According to Timothy Snyder, "something that is never said, because it's inconvenient for precisely everyone, is that more Ukrainian Communists collaborated with the Germans, than did Ukrainian nationalists." Snyder also points out that very many of those who collaborated with the German occupation also collaborated with the Soviet policies in the 1930s.

Holocaust

Main article: The Holocaust in Ukraine

The elimination of Jews during the Holocaust in Ukraine started within a few days of the beginning of the Nazi occupation. The Ukrainian Auxiliary Police, which formed mid August 1941, assisted by Einsatzgruppen C, and Police battalions rounded up Jews and undesirables for the Babi Yar massacre, as well as other later massacres in cities and towns of modern-day Ukraine, such as Kolky, Stepan, Lviv, Lutsk, and Zhytomyr.

During this period, on 1 September 1941, the Nazi-sponsored Ukrainian newspaper Volhyn wrote, in an article titled Zavoiovuimo misto" (Let's Conquer the City):

"All elements that reside in our land, whether they are Jews or Poles, must be eradicated. We are at this very moment resolving the Jewish question, and this resolution is part of the plan for the Reich's total reorganization of Europe.", "The empty space that will be created, must immediately and irrevocable be filled by the real owners and masters of this land, the Ukrainian people".

Reinforced by religious prejudice, antisemitism turned violent in the first days of the German attack on the Soviet Union. Some Ukrainians derived nationalist resentment from the belief that the Jews had worked for Polish landlords. The NKVD prisoner massacres by the Soviet secret police while they retreated eastward were blamed on Jews. The antisemitic canard of Jewish Bolshevism provided justification for the revenge killings by the ultranationalist Ukrainian People's Militia, which accompanied German Einsatzgruppen moving east. In Boryslav (prewar Borysław, Poland, population 41,500), the SS commander gave an enraged crowd, which had seen bodies of men murdered by NKVD and laid out in the town square, 24 hours to act as they wished against Polish Jews, who were forced to clean the dead bodies and to dance and then were killed by beating with axes, pipes etc. The same type of mass murders took place in Brzezany. During Lviv pogroms, 7,000 Jews were murdered by Ukrainian nationalists, led by the Ukrainian People's Militia. As late as 1945, Ukrainian militants were still rounding up and murdering Jews.

While some of the collaborators were civilians, others were given a choice to enlist for paramilitary service beginning in September 1941 from the Soviet prisoner-of-war camps because of ongoing close relations with the Ukrainian Hilfsverwaltung. In total, over 5,000 native Ukrainian soldiers of the Red Army signed up for training with the SS at a special Trawniki training camp to assist with the Final Solution. Another 1,000 defected during field operations. Trawniki men took a major part in the Nazi plan to exterminate European Jews during Operation Reinhard. They served at all extermination camps and played an important role in the annihilation of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (see the Stroop Report) and the Białystok Ghetto Uprising among other ghetto insurgencies. The men who were dispatched to death camps and Jewish ghettos as guards were never fully trusted and so were always overseen by Volksdeutsche. Occasionally, along with the prisoners they were guarding, they would kill their commanders in the process of attempting to defect.

In May 2006, the Ukrainian newspaper Ukraine Christian News commented, "Carrying out the massacre was the Einsatzgruppe C, supported by members of a Waffen-SS battalion and units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police, under the general command of Friedrich Jeckeln. The participation of Ukrainian collaborators in these events, now documented and proven, is a matter of painful public debate in Ukraine".

Collaborating organizations, political movements, individuals and military volunteers

In total, the Germans enlisted 250,000 native Ukrainians for duty in five separate formations including the Nationalist Military Detachments (VVN), the Brotherhoods of Ukrainian Nationalists (DUN), the SS Division Galicia, the Ukrainian Liberation Army (UVV) and the Ukrainian National Army (Ukrainische Nationalarmee, UNA). By the end of 1942, in Reichskommissariat Ukraine alone, the SS employed 238,000 native Ukrainian police and 15,000 Germans, a ratio of 1 to 16.

Auxiliary police

The 109th, 114th, 115th, 116th, 117th, 118th, 201st Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft-battalions participated in anti-partisan operations in Ukraine and Belarus. In February and March 1943, the 50th Ukrainian Schutzmannschaft Battalion participated in the large anti-guerrilla action «Operation Winterzauber» (Winter magic) in Belarus, cooperating with several Latvian and the 2nd Lithuanian battalion. Schuma-battalions burned down villages suspected of supporting Soviet partisans. On March 22, 1943, all inhabitants of the village of Khatyn in Belarus were burned alive by the Nazis in what became known as the Khatyn massacre, with the participation of the 118th Schutzmannschaft battalion.

According to Paul R. Magocsi, "Ukrainian auxiliary police and militia, or simply "Ukrainians" (a generic term that in fact included persons of non-Ukrainian as well as Ukrainian national background) participated in the overall process as policemen and camp guards".

Ukrainian volunteers in the German armed forces

SS Division Galicia

Main article: 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Ukrainian)

On 28 April 1943, the German Governor of the District of Galicia, Otto Wächter, and the local Ukrainian administration officially declared the creation of the SS Division Galicia. Volunteers signed for service as of 3 June 1943 and numbered 80,000. On 27 July 1944, the division was formed into the Waffen-SS as 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS (1st Ukrainian).

Sol Litman of the Simon Wiesenthal Center states that there are many proven and documented incidents of atrocities and massacres committed by the unit against Poles and Jews during World War II. Official SS records show that the 4, 5, 6 and 7 SS-Freiwilligen regiments were under Ordnungspolizei command during the accusations. See 14th Waffen Grenadier Division of SS, the 1st Galician: Atrocities and war crimes.

Ukrainian National Committee

Main article: Ukrainian National CommitteeIn March 1945, the Ukrainian National Committee was set up after a series of negotiations with the Germans. The Committee represented and had command over all Ukrainian units fighting for the Third Reich, such as the Ukrainian National Army. However, it was too late, and the committee and the army were disbanded at the end of the war.

Ukrainian Central Committee

Pavlo Shandruk became the head of the National Committee, while Volodymyr Kubijovyč, the head of the Ukrainian Central Committee [pl; ru; uk], became his deputy. The Central Committee was the officially recognized Ukrainian community and quasi-political organization under the Nazi occupation of Poland.

Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists

- Ukrainian National Government of the Ukrainian State, led by OUN-B. Suppressed by the Nazis shortly after its establishment.

Heads of local Ukrainian administration and public figures under the German occupation

- Oleksander Ohloblyn (1899–1992) in the fall of 1941, Ohloblyn was appointed the Mayor of Kiev at the behest of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists. He held the post from September 21 to October 25.

- Volodymyr Bahaziy (Kiev mayor, 1941–1942,

- Leontii Forostivsky (Kiev mayor, 1942–1943)

- Fedir Bohatyrchuk (head of the Ukrainian Red Cross, 1941–1942)

- Oleksii Kramarenko (Kharkov mayor, 1941–1942, executed by Germans in 1943)

- Oleksander Semenenko (Kharkov mayor, 1942–1943)

- Paul Kozakevich (Kharkov mayor, 1943)

- Aleksandr Sevastianov (Vinnytsia mayor, 1941 – ?)

See also

- Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy

- History of the Jews in Ukraine

- List of Ukrainian Righteous Among the Nations

References

- Markiewicz, Paweł (2021). Unlikely Allies: Nazi German and Ukrainian Nationalist Collaboration in the General Government During World War II. Purdue University Press. ISBN 978-1-61249-679-5.

- Perks, Robert (1993). "Ukraine's Forbidden History: Memory and Nationalism". Oral History. 21 (1): 43–53. ISSN 0143-0955. JSTOR 40179315.

Both occupying regimes imposed their own language and government... For the majority of Ukrainians in the east, Soviet rule was even more repressive

- Paul H. Rosenberg (28 March 2014). "Seven Decades of Nazi Collaboration: America's Dirty Little Ukraine Secret (An interview with Russ Bellant)". The Nation.

- Torvey, Colin. "Means, Ends, and Perpetrators: Connections Between the Holocaust and the Genocide of Ethnic Poles in Volhynia and Galicia".

- "Historian Timothy Snyder: Babi Yar A Tragedy For All Ukrainians". Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 2016-09-29. Retrieved 2023-05-02.

However, from the very beginning, and that is true, some local residents, Ukrainians -- not only ethnic Ukrainians but also Russians, Tatars, and others -- collaborated. Some people from each ethnic group collaborated.

- ^ Alfred J. Rieber (2003). "Civil Wars in the Soviet Union" (PDF). Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 4 (1). Project Muse: 133, 145–147. doi:10.1353/kri.2003.0012. S2CID 159755578. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2016-04-11. Slavica Publishers.

- Tadeusz Piotrowski (1997). "1. Soviet terror". Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918-1947. McFarland. pp. 11–12. ISBN 978-0-7864-2913-4.

- Thurston, Robert (1996). Life and Terror in Stalin's Russia, 1934–1941.

- Dziobak, V. V. (2002). Тарас Бульба-Боровець і його військові підрозділи в українському русі Опору (1941—1944) [Taras Bulba-Borovets and his military units in the Ukrainian Resistance movement (1941—1944)] (in Ukrainian). Kiev: Institute of History of Ukraine. pp. 111–119.

- Dziobak 2002, p. 108.

- Dziobak 2002, p. 172.

- Dziobak 2002, pp. 176–177.

- ^ John A. Armstrong, Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe, The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 40, No. 3 (Sep., 1968), p. 409.

- Germans must remember the truth about Ukraine – for their own sake Archived 2020-11-11 at the Wayback Machine, Eurozine (7 July 2017)

- Jürgen Matthäus (18 April 2013). Jewish Responses to Persecution: 1941–1942. AltaMira Press. p. 524. ISBN 978-0-7591-2259-8.

- Spector, Shmuel (1990). "Extracts from the Babi Yar article". In Israel Gutman (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Holocaust. Yad Vashem, Sifriat Hapoalim, Macmillan Publishing Company. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012.

The implementation of the decision to kill all the Jews of Kiev was entrusted to Sonderkommando 4a. The unit consisted of SD men (Sicherheitsdienst; Security Service) and Sicherheitspolizei (Security Police; Sipo); the third company of the Special Duties Waffen-SS battalion; and a platoon of the No. 9 police battalion. The unit was reinforced by police battalions Nos. 45 and 305 and by units of the Ukrainian auxiliary police.

- Kac, Daniel (1983). "Perl Tine Reports". Fun ash aroysgerufn (Summoned from the Ashes) (in Yiddish). Warsaw, Poland: Czytelnik. pp. 135–158.

- "Kołki". Yad Vachem. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- Ganuz, I.; Peri, J. (28 May 2006). "The Generations of Stepan: The History of Stepan and Its Jewish Population". jewishgen.org. Archived from the original on 6 September 2024. Retrieved 25 May 2016.

- "Stepan". Faina Petryakova Science Center for Judaica and Jewish Art. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2023-09-27.

- "The Holocaust Timeline: 1941 - July 25 Pogrom in Lvov/June 30 Germany occupies Lvov; 4,000 Jews killed by July 3/June 30 Einsatzkommando 4a and local Ukrainians kill 300 Jews in Lutsk/September 19 Zhitomir Ghetto liquidated; 10,000 killed". yadvashem.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2018. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- Burds, Jeffrey (2013). Holocaust in Rovno. Palgrave McMillan. p. 39. ISBN 9781137388391.

- Messina, Adele Valeria (2017). American Sociology and Holocaust Studies The Alleged Silence and the Creation of the Sociological Delay. Academic Studies Press. pp. 176, 177. ISBN 9781618115478.

- Spector, Shmuel. The Jews of Volynia and their reaction to extermination. Yad Vashem. p. 160.

- Basic Historical Narrative of the Babyn Yar Holocaust Memorial Center. Kyiv Ukraine. 2018. p. 114.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Shkandrij, Myroslav (2015). "10". Ukrainian Nationalism. Yale University Press. p. 242. ISBN 9780300206289.

- Gilbert, Martin (1985). The Holocaust: The Human Tragedy. RosettaBooks LLC. p. 199. ISBN 9780795337192.

- ^ Richard J. Evans (2009). The Third Reich at War: 1939-1945. London: Penguin Books. pp. 203–223. ISBN 978-1-101-02230-6. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Jakob Weiss, Lemberg Mosaic, p. 173. ISBN 0-9831091-1-7.

- Lucy S. Dawidowicz (1975), The War Against the Jews 1933-1945, Bantam Books Inc., New York, p. 171.

- The Holocaust Chronicle, A History in Words and Pictures, Edited by David J. Hogan, Publications International Ltd, Lincolnwood, Illinois, p.592

- Markus Eikel (2013). "The local administration under German occupation in central and eastern Ukraine, 1941–1944". The Holocaust in Ukraine: New Sources and Perspectives (PDF). Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. 110–122 in PDF. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-03-15. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

Ukraine differs from other parts of the Nazi-occupied Soviet Union, whereas the local administrators have formed the Hilfsverwaltung in support of extermination policies in 1941 and 1942, and in providing assistance for the deportations to camps in Germany, mainly in 1942 and 1943.

- ^ Peter R. Black (2006). "Police Auxiliaries for Operation Reinhard". In David Bankir (ed.). Secret Intelligence and the Holocaust. Enigma Books. pp. 331–348. ISBN 1-929631-60-X. Archived from the original on 2023-03-17. Retrieved 2020-11-05 – via Google Books.

- Yitzhak Arad (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. p. 21. ISBN 0-253-34293-7. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Gregory Procknow (2011). Recruiting and Training Genocidal Soldiers. Francis & Bernard Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-9868374-0-1. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2020-11-05.

- Himka, John-Paul (1998). "Ukrainian Collaboration in the Extermination of the Jews During World War II: Sorting out the Long-Term and Conjunctural Factors". In Jonathan Frankel (ed.). Studies in Contemporary Jewry: Volume XIII: The Fate of the European Jews, 1939-1945: Continuity or Contingency?. Vol. XIII. Oxford University Press. pp. 170–190. ISBN 978-0-19-511931-2. Archived from the original on January 6, 2012.

- "Belzec: Stepping Stone to Genocide, Chapter 4 – cont". JewishGen, Inc. February 13, 2008. Archived from the original on October 29, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Holocaust Victims Honored in Babi Yar Archived 2006-11-14 at the Wayback Machine (Ukraine Christian News, May 3, 2006) Accessed January 14, 2006.

- Motyka, Grzegorz (February 2001). "Dywizja SS 'Galizien'" [SS Division 'Galicia']. Pamięć I Sprawiedliwość (in Polish). 1. Biuletyn IPN. Archived from the original on 3 January 2003.

- Jeffrey Burds (2013). Holocaust in Rovno: The Massacre at Sosenki Forest, November 1941. Springer. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-1-137-38840-7. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2020-09-19.

- Gerlach, C. "Kalkulierte Morde" Hamburger Edition, Hamburg, 1999.

- State Memorial Complex "Khatyn" official web-page https://khatyn.by/en/genocide/expeditions/ Archived 2021-11-30 at the Wayback Machine - The destruction of the village of Khatyn is a tragic and vivid example. The village was annihilated by the thugs from the 118th Police Battalion, which was stationed in a small town of Pleschinitsy, and by the thugs from the SS battalion "Dirlewanger", which was stationed in Logoisk.

- В.И. Адамушко "Хатынь. Трагедия и память НАРБ 2009 ISBN 978-985-6372-62-2

- Magocsi, Paul Robert (2010). A History of Ukraine (2nd ed.). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 678. ISBN 978-0-8020-7820-9. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2023-02-28.

- K.G. Klietmann Die Waffen SS; eine Dokumentation Osnabruck Der Freiwillige, 1965 p.194

- ^ GEORG TESSIN Verbande und Truppen der deutschen Wehrmacht und Waffen SS im Zweiten Weltkrieg 1939-1945 DRITTER BAND: Die Landstreitkrafte 6—14 VERLAG E. S. MITTLER & SOHN GMBH. • FRANKFURT/MAIN ISBN 3-7648-0942-6 page 313

- Litman, Sol (2003). Pure Soldiers or Bloodthirsty Murderers?: The Ukrainian 14th Waffen-SS Galicia Division (Hardcover ed.). Black Rose Books. ISBN 1-55164-219-0.

- Tessin, Georg / Kannapin, Norbert. Waffen-SS und Ordnungspolizei im Kriegseinsatz 1939-1945.ISBN 3-7648-2471-9 p.52.

- Plokhy, Serhii (2012). The Cossack Myth: History and Nationhood in the Age of Empires. Cambridge University Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN 978-1-13953-673-8. Archived from the original on 2024-09-06. Retrieved 2022-04-20.

- David Fanning, Erik Levi, ed. (2019). The Routledge Handbook to Music under German Occupation, 1938-1945: Propaganda, Myth and Reality. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-86258-5.

- Berkhoff, Karel C. (2008). Harvest of Despair: Life and Death in Ukraine under Nazi Rule. Harvard University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-674-02078-8.

Further reading

See also: Bibliography of the Soviet Union during World War II and Bibliography of Ukrainian history § World War II- Armstrong, J. A. (1968). Collaborationism in World War II: The Integral Nationalist Variant in Eastern Europe. The Journal of Modern History, 40(3), pp. 396–410.

- Dean, M. (31 December 1999). Collaboration in the Holocaust: Crimes of the Local Police in Belorussia and Ukraine, 1941-44. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-22056-3.

- Gilbert Martin (1987). The Holocaust: A History of the Jews of Europe During the Second World War (Reprint ed.). Owl Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-0348-2.

- Gilbert Martin (1986). The Holocaust: The Jewish tragedy (Unknown Binding ed.). Collins. ISBN 978-0-00-216305-7.

- Goldenshteyn, M. (12 December 2021). So They Remember: A Jewish Family's Story of Surviving the Holocaust in Soviet Ukraine. Oxford University Press.

- Lower, W. (19 September 2005). Nazi Empire-Building and the Holocaust in Ukraine. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Mordecai Paldiel (1993). The Path of the Righteous: Gentile Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. KTAV Publishing House in association with the ADL. ISBN 0-88125-376-6.

- Mordecai Paldiel and Elie Wiesel (2007). The Righteous Among the Nations: Rescuers of Jews During the Holocaust. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-115112-5.

- Дзьобак, Володимир (1995). "Тарас Боровець і "Поліська Січ"". З архівів ВУЧК-ГПУ-НКВД-КГБ. 1/2(2/3). Archived from the original on March 11, 2012. LCC JN6635.A55 I679

- Steinhart, E. C. (9 February 2015). The Holocaust and the Germanization of Ukraine. Cambridge University Press.

- Zabarko, B., ed. (30 November 2004). Holocaust in the Ukraine. Vallentine Mitchell.

| Schutzstaffel (SS) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branches | |||||||

| Leadership | |||||||

| Leaders | |||||||

| Main departments |

| ||||||

| Ideological institutions | |||||||

| Police and security services | |||||||

| Führer protection | |||||||

| Waffen-SS units |

| ||||||

| SS-controlled enterprises | |||||||