| Revision as of 10:45, 13 April 2008 editTreybien (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers123,057 edits →Contemporary literature← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:39, 7 January 2025 edit undoWrangler1981 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,504 edits →Comic-book anti-heroes | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Type of fictional character}} | |||

| In ], an '''anti-hero''' is a ] who is lacking the traditional heroic attributes and qualities, and instead possesses character traits that are antithetical to heroism. | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2023}} | |||

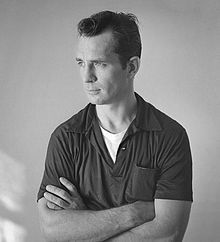

| ] films commonly feature antiheroes as lead characters whose actions are morally ambiguous. ], pictured here in '']'' (1964), portrayed the archetypal antihero called the "]" in the Italian '']'' of ].]] | |||

| <!--Please do not add links to TV Tropes, amateur blogs, user-generated sources, and fan websites--> | |||

| An '''antihero ''' (sometimes spelled as '''anti-hero''')<ref name="Lexico">{{cite web |title=Anti-Hero |url=https://www.lexico.com/definition/anti-hero |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200806044801/https://www.lexico.com/definition/anti-hero |url-status=dead |archive-date=6 August 2020 |website=] |publisher=] |access-date=26 September 2020}}</ref> or '''anti-heroine''' is a main character in a narrative (in literature, film, TV, etc.) who may lack some conventional heroic qualities and attributes, such as ], and ].<ref name="Lexico"/> Although antiheroes may sometimes perform actions that most of the audience considers morally correct, their reasons for doing so may not align with the audience's morality.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Laham|first1=Nicholas|title=Currents of Comedy on the American Screen: How Film and Television Deliver Different Laughs for Changing Times |date=2009|publisher=]|location=Jefferson, North Carolina|isbn=9780786442645|page=51}}</ref> | |||

| The word ''anti-hero'' itself is fairly recent, and its principal definition has changed through the years. The 1940 edition of ] listed ''anti-hero'', but did not define it.<ref>''Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 11th Edition'', 2004</ref> Later sources would call the anti-hero a persona characterized by a lack of "traditional" heroic qualities.<ref>''American Heritage Dictionary of the American Language'', 1992</ref> | |||

| Antihero is a literary term that can be understood as standing in opposition to the traditional hero, i.e., one with high social status, well liked by the general populace. Past the surface, scholars have additional requirements for the antihero. | |||

| The "]" antihero, is defined by three factors. The first is that the antihero is doomed to fail before their adventure begins. The second constitutes the blame of that failure on everyone but themselves. Thirdly, they offer a critique of social morals and reality.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Kennedy |first=Theresa Varney |date=2014 |title='No Exit' in Racine's Phèdre: The Making of the Anti-Hero |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/tfr.2014.0114 |journal=] |volume=88 |issue=1 |pages=165–178 |doi=10.1353/tfr.2014.0114 |s2cid=256361158 |issn=2329-7131}}</ref> To other scholars, an antihero is inherently a hero from a specific point of view, and a villain from another.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Klapp |first=Orrin E. |date=September 1948 |title=The Creation of Popular Heroes |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/220292 |journal=] |volume=54 |issue=2 |pages=135–141 |doi=10.1086/220292 |s2cid=143440315 |issn=0002-9602}}</ref> | |||

| Typically, an antihero is the focal point of conflict in a story, whether as the protagonist or as the antagonistic force.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Petersen |first=Michael Bang |title=An Age of Chaos? |date=2019 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/26907483 |journal=RSA Journal |volume=165 |issue=3 (5579) |pages=44–47 |jstor=26907483 |issn=0958-0433}}</ref> This is due to the antihero's engagement in the conflict, typically of their own will, rather than a specific calling to serve the greater good. As such, the antihero focuses on their personal motives first and foremost, with everything else secondary.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Klapp |first=Orrin E. |date=1948 |title=The Creation of Popular Heroes |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2771362 |journal=American Journal of Sociology |volume=54 |issue=2 |pages=135–141 |doi=10.1086/220292 |jstor=2771362 |s2cid=143440315 |issn=0002-9602}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | == History == | ||

| ] and other figures of the "]" created reflective, critical protagonists who influenced the antiheroes of many later works.]] | |||

| An early antihero is ]'s ], since he serves to voice criticism, showcasing an anti-establishment stance.<ref name="tolstoy1">{{cite book |last1=Steiner |first1=George |title=Tolstoy Or Dostoevsky: An Essay in the Old Criticism |date=2013 |publisher=Open Road |location=New York |isbn=9781480411913 |pages=197–207}}</ref> The concept has also been identified in classical ],<ref name="britannica1">{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/27600/antihero |title=antihero |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |date=14 February 2013 |access-date=9 August 2014}}</ref> ], and ]<ref name="tolstoy1"/> such as '']''<ref name="britannica1"/><ref>{{cite web |last1=Wheeler |first1=L. Lip |title=Literary Terms and Definitions A |url=http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/lit_terms_A.html#antihero_anchor |website=Dr. Wheeler's Website |publisher=] |access-date=3 October 2013}}</ref> and the ] rogue.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Halliwell |first1=Martin |title=American Culture in the 1950s |url=https://archive.org/details/americancultures00hall_904 |url-access=limited |date=2007 |publisher=] |location=Edinburgh |isbn=9780748618859 |page=}}</ref> | |||

| There is no definitive moment when the anti-hero came into existence as a literary ]. ]' ''Argonautica'' portrays ] as a timid, passive, indecisive man that contrasts sharply with other ] heroes.<ref>{{cite journal| author=Haggar, Daley| title=Review of ''Infinite Jest''| journal=Harvard Advocate| year=1996| volume=Fall 96}}</ref> The anti-hero has evolved over time, changing as society's conceptions of the hero changed, from the ] times of ]'s '']'' and ]'s ], to the darker-themed ] of the 19th century, such as ]'s '']'' or ]'s '']''. The ] also sets a literary precedent for the modern concept of the anti-hero. | |||

| An anti-hero that fits the more contemporary notion of the term is the lower-caste warrior ], in ]. Karna is the sixth brother of the ] (symbolising ''good''), born out of wedlock, and raised by a lower caste charioteer. He is ridiculed by the Pandavas, but accepted as an excellent warrior by the antagonist ], this becoming a loyal friend to him, eventually fighting on the ''wrong'' side of the final ]. Karna serves as a critique of the then society, the protagonists, as well as the idea of the war being worthwhile itself – even if Krishna later justifies it properly.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Kotru |first1=Umesh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=tBMfCAAAQBAJ&q=Daanaveera |title=Karna The Unsung Hero of the Mahabharata |last2=Zutshi |first2=Ashutosh |date=2015-03-01 |publisher=One Point Six Technology Pvt Ltd |isbn=978-93-5201-304-3 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| == Contemporary literature == | |||

| In modern times, heroes have enjoyed an increased moral complexity. Mid-20th century playwrights such as ] and ] showcased anti-heroic ]s recognizable by their lack of identity and determination. ] and ] of the mid-20th century saw characters such as ], who lacked the glorious appeal of previous heroic figures, become popular. Influenced by the pulps, early ]s featured anti-heroic characters such as ] (whose shadowy nature contrasted with their openly "heroic" peers like ]) and ] (who would just as soon conquer ] as try to save it).<ref></ref> ]'s "]" showcased a wandering ] (the "]" played by ]) whose gruff demeanor clashed with other heroic characteristics. {{Fact|date=August 2007}} ] has been considered the most influential antihero archetype in the superhero genre. | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| The young, flawed, and brooding antihero became the most widely imitated archetype in the superhero genre since the appearance of superman.<br /> | |||

| The term antihero was first used as early as 1714,<ref name="Merriam">{{cite web |url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/antihero |title=Antihero |website=Merriam-Webster Dictionary |date=31 August 2012 |access-date=3 October 2013}}</ref> emerging in works such as '']'' in the 18th century,<ref name="tolstoy1"/> and is also used more broadly to cover ]es as well, created by the ] poet ].<ref>{{cite web |last1=Wheeler |first1=L. Lip |title=Literary Terms and Definitions B |url=http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/lit_terms_A.html#antihero_anchor |website=Dr. Wheeler's Website |publisher=] |access-date=6 September 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Bradford W. Wright, Comic Book Nation: ''The transformation of Youth Culture in America'' 212<br /> | |||

| Literary ] in the 19th century helped popularize new forms of the antihero,<ref>{{cite book |last1=Alsen |first1=Eberhard |title=The New Romanticism: A Collection of Critical Essays |date=2014 |publisher=] |location=Hoboken |isbn=9781317776000 |page=72 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DDHKAgAAQBAJ&q=anti+hero+romanticism&pg=PA72 |access-date=20 April 2015 |via=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Simmons |first1=David |title=The Anti-Hero in the American Novel: From Joseph Heller to Kurt Vonnegut |date=2008 |publisher=] |location=New York |isbn=9780230612525 |page=5 |edition=1st |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=KZnFAAAAQBAJ&q=anti+hero+romanticism&pg=PA5 |access-date=20 April 2015 |via=]}}</ref> such as the ].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Lutz |first1=Deborah |title=The Dangerous Lover: Gothic Villains, Byronism, and the Nineteenth-century Seduction Narrative |date=2006 |publisher=] |location=Columbus |isbn=9780814210345 |page=82 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=47I-p5s49vQC&q=antihero+%22gothic+double%22&pg=PA82 |access-date=20 April 2015 |via=]}}</ref> The antihero eventually became an established form of social criticism, a phenomenon often associated with the unnamed protagonist in ]'s '']''.<ref name="tolstoy1"/> The antihero emerged as a ] to the traditional hero ], a process that ] called the fictional "center of gravity".<ref name="Frye">{{cite book |last1=Frye |first1=Northrop |url=https://archive.org/details/anatomyofcritici0000frye_e1u9/page/34/mode/2up |title=Anatomy of Criticism |date=2002 |publisher=] |isbn=9780141187099 |location=London |page=34 |url-access=registration}}</ref> This movement indicated a literary change in heroic ethos from feudal aristocrat to urban democrat, as was the shift from epic to ironic narratives.<ref name="Frye"/> | |||

| Superman on the Couch by Danny Fingeroth 151</blockquote> | |||

| ] (1884) has been called "the first antihero in the American nursery".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hearn |first1=Michael Patrick |title=The Annotated Huckleberry Finn: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) |date=2001 |publisher=] |location=New York |isbn=0393020398 |page=xvci |edition=1st |url=https://archive.org/details/annotatedhuckleb0000twai |url-access=registration}}</ref> Charlotte Mullen of ]'s '']'' (1894) has been described as an anti-heroine.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Ehnenn |first1=Jill R. |title=Women's Literary Collaboration, Queerness, and Late-Victorian Culture |date=2008 |publisher=] |isbn=9780754652946 |page=159 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=o9_qvJNKE98C&q=antiheroine+%22Real+Charlotte%22&pg=PA159 |access-date=7 April 2020 |language=en |via=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Cooke |first1=Rachel |title=The 10 best Neglected literary classics – in pictures |url=https://www.theguardian.com/culture/gallery/2011/feb/27/ten-best-neglected-literary-classics |access-date=7 April 2020 |work=] |date=27 February 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Woodcock |first1=George |title=Twentieth Century Fiction |date=1 April 1983 |publisher=] |isbn=9781349170661 |page=628 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fgKwCwAAQBAJ&q=antiheroine++&pg=PA628 |access-date=7 April 2020 |language=en |via=]}}</ref> | |||

| The antihero became prominent in early 20th century ] works such as ]'s '']'' (1915),<ref>{{cite book |last1=Barnhart |first1=Joe E. |title=Dostoevsky's Polyphonic Talent |date=2005 |publisher=] |location=Lanham |isbn=9780761830979 |page=151}}</ref> ]'s '']'' (1938),<ref>{{cite book |last1=Asong |first1=Linus T. |title=Psychological Constructs and the Craft of African Fiction of Yesteryears: Six Studies |date=2012 |publisher=Langaa Research & Publishing CIG |location=Mankon |isbn=9789956727667 |pages=76 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MFkDP6Lym9YC&q=La+Naus%C3%A9e+anti-hero&pg=PA76 |via=]}}</ref> and ]'s '']'' (1942).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Gargett |first1=Graham |title=Heroism and Passion in Literature: Studies in Honour of Moya Longstaffe |date=2004 |publisher=Rodopi |location=Amsterdam |isbn=9789042016927 |page=198 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sc6QqZCpHgYC&q=l%27etranger+anti-hero&pg=PA198 |via=]}}</ref> The protagonist in these works is an indecisive central character who drifts through his life and is marked by ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Brereton |first1=Geoffrey |title=A Short History of French Literature |date=1968 |publisher=] |pages=254–255}}</ref> | |||

| Many modern anti-heroes possess, or even encapsulate, the ] rejection of traditional values symptomatic of ] in general, as well as the disillusion felt after ] and the ]. It has been argued that the continuing popularity of the anti-hero in modern literature and popular culture may be based on the recognition that a person is fraught with human frailties, unlike the archetypes of the white-hatted cowboy and the noble warrior, and is therefore more accessible to readers and viewers. This popularity may also be symptomatic of the rejection by the ] of traditional values after the ] revolution of the 1960s.<ref>{{cite journal| author=Erickson, Leslie| title=The Search for Self: Everyday Heroes and an Integral Re-Visioning of the Heroic Journey in Postmodern Literature and Popular Culture | journal=Ph.D Dissertation| year=2004| volume=University of Nebraska}}</ref> | |||

| The antihero entered American literature in the 1950s and up to the mid-1960s as an alienated figure, unable to communicate.<ref name="Hart">{{cite book |last1=Hardt |first1=Michael |last2=Weeks |first2=Kathi |title=The Jameson Reader |date=2000 |publisher=] |location=Oxford, UK ; Malden, Massachusetts |isbn=9780631202707 |edition=Reprint |pages=294–295}}</ref> The American antihero of the 1950s and 1960s was typically more proactive than his French counterpart.<ref name="Edelstein">{{cite book |last1=Edelstein |first1=Alan |title=Everybody is Sitting on the Curb: How and why America's Heroes Disappeared |date=1996 |publisher=Praeger |location=Westport, Connecticut |isbn=9780275953645 |pages=1; 18}}</ref> The British version of the antihero emerged in the works of the "]" of the 1950s.<ref name="britannica1"/><ref>{{cite book |last1=Ousby |first1=Ian |title=The Cambridge Paperback Guide to Literature in English |date=1996 |publisher=] |location=New York |isbn=9780521436274 |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/cambridgepaperba00ousb/page/27}}</ref> The collective protests of ] saw the solitary antihero gradually eclipsed from fictional prominence,<ref name="Edelstein"/> though not without subsequent revivals in literary and cinematic form.<ref name="Hart"/> | |||

| In the postmodern era, traditionally defined heroic qualities, akin to the classic "knight in shining armor" type, have given way to the "gritty truth" of life, and authority in general is being questioned. The brooding ] or "noble criminal" archetype seen in characters like Batman is slowly becoming part of the popular conception of heroic valor rather than being characteristics that are deemed un-heroic.<ref>{{cite journal| author=Lawall G,| title=Apollonius' Argonautica. Jason as anti-hero| journal=Yale Classical Studies| year=1966| volume=19| pages= 119-169}}</ref> | |||

| ], Collection Fonds cantonal d’art contemporain at Art Genéve 2024<ref>{{Cite web |title=Accueil |url=https://fcac.ch/ |access-date=2024-11-10 |website=Fonds cantonal d'art contemporain}}</ref>]] | |||

| During the ] from the 2000s and into early 2020s, antiheroes such as ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] became prominent in the most popular and critically acclaimed TV shows.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Reese |first1=Hope |title=Why Is the Golden Age of TV So Dark? |url=https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2013/07/why-is-the-golden-age-of-tv-so-dark/277696/ |website=] |access-date=31 October 2021 |language=en |date=11 July 2013 |quote=A new book explains the link between the rise of antihero protaganists and the unprecedented abundance of great TV (and what Dick Cheney has to do with it).}}</ref><ref>Faithfull, E. (2021). How House brought the "savant anti-hero" into the mainstream and changed TV dramas. www.nine.com.au. https://www.nine.com.au/entertainment/latest/house-savant-anti-hero-medical-drama-9now/0e030210-8bfe-424f-b687-f2e36e6f0694</ref><ref>Pruner, A. (n.d.). Hear us out: Gregory House was TV's last great doctor. https://editorial.rottentomatoes.com/article/hear-us-out-gregory-house-was-tvs-last-great-doctor/</ref> | |||

| In his essay published in 2020, ''Postheroic Heroes - A Contemporary Image (german: Postheroische Helden - Ein Zeitbild)'', German ] ] examines the simultaneity of heroic and post-heroic role models as an opportunity to explore the place of the heroic in contemporary society.<ref>{{Cite web |last=deutschlandfunk.de |date=2020-03-05 |title=Ulrich Bröckling: "Postheroische Helden" - Man hüte sich vor Helden! |url=https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/ulrich-broeckling-postheroische-helden-man-huete-sich-vor-100.html |access-date=2024-11-10 |website=Deutschlandfunk |language=de}}</ref> In contemporary art, artists such as the French multimedia artist ] negotiate in his series of ''Soft Heroes'', in which overburdened, modern and tired Anti Heroes seem to have given up on the world around them. <ref>{{Cite web |title=Soft Heroes |url=https://dda-geneve.ch/fr/artistes/thomas-liu-le-lann/oeuvres/soft-heroes |access-date=2024-11-10 |website=Documents d’artistes Genève |language=fr}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-05-10 |title=Thomas Liu Le Lann: Wer ist Milo? |url=https://www.gallerytalk.net/thomas-liu-le-lann-dittrich-schlechtriem-milo/ |access-date=2024-11-10 |website=gallerytalk.net |language=de}}</ref> | |||

| ===Comic book anti-heroes=== | |||

| {{main|Comic book anti-hero}} | |||

| In American mainstream comic books, anti-heroes have become increasingly popular since the 1970s. The comic book version is generally a variation on the formula of ]es. As Suzana Flores describes it, a comic book antihero is "often psychologically damaged, simultaneously depicted as superior due to his superhuman abilities and inferior due to his impetuousness, irrationality, or lack of thoughtful evaluation." Particularly well-known comic book anti-heroes include ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Flores|2018|p=146-147}} These characters have all been adapted into feature films, as well. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| {{portal|Literature}} | |||

| <!-- Commented out because image was deleted: ]''..]] --> | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ], a similar type of character in professional wrestling | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| == References == | |||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| == |

===Bibliography=== | ||

| * {{cite book |last1=Flores |first1=Suzana E. |title=Untamed: The Psychology of Marvel's Wolverine|date=2018 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-4766-7442-1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=L4liDwAAQBAJ}} | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| {{Wiktionary}} | |||

| {{Comics}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Fiction writing}} | |||

| * | |||

| ⚫ | {{Stock characters}} | ||

| {{authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:39, 7 January 2025

Type of fictional character For other uses, see Antihero (disambiguation).

An antihero (sometimes spelled as anti-hero) or anti-heroine is a main character in a narrative (in literature, film, TV, etc.) who may lack some conventional heroic qualities and attributes, such as idealism, and morality. Although antiheroes may sometimes perform actions that most of the audience considers morally correct, their reasons for doing so may not align with the audience's morality.

Antihero is a literary term that can be understood as standing in opposition to the traditional hero, i.e., one with high social status, well liked by the general populace. Past the surface, scholars have additional requirements for the antihero.

The "Racinian" antihero, is defined by three factors. The first is that the antihero is doomed to fail before their adventure begins. The second constitutes the blame of that failure on everyone but themselves. Thirdly, they offer a critique of social morals and reality. To other scholars, an antihero is inherently a hero from a specific point of view, and a villain from another.

Typically, an antihero is the focal point of conflict in a story, whether as the protagonist or as the antagonistic force. This is due to the antihero's engagement in the conflict, typically of their own will, rather than a specific calling to serve the greater good. As such, the antihero focuses on their personal motives first and foremost, with everything else secondary.

History

An early antihero is Homer's Thersites, since he serves to voice criticism, showcasing an anti-establishment stance. The concept has also been identified in classical Greek drama, Roman satire, and Renaissance literature such as Don Quixote and the picaresque rogue.

An anti-hero that fits the more contemporary notion of the term is the lower-caste warrior Karna, in The Mahabharata. Karna is the sixth brother of the Pandavas (symbolising good), born out of wedlock, and raised by a lower caste charioteer. He is ridiculed by the Pandavas, but accepted as an excellent warrior by the antagonist Duryodhana, this becoming a loyal friend to him, eventually fighting on the wrong side of the final just war. Karna serves as a critique of the then society, the protagonists, as well as the idea of the war being worthwhile itself – even if Krishna later justifies it properly.

The term antihero was first used as early as 1714, emerging in works such as Rameau's Nephew in the 18th century, and is also used more broadly to cover Byronic heroes as well, created by the English poet Lord Byron.

Literary Romanticism in the 19th century helped popularize new forms of the antihero, such as the Gothic double. The antihero eventually became an established form of social criticism, a phenomenon often associated with the unnamed protagonist in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's Notes from Underground. The antihero emerged as a foil to the traditional hero archetype, a process that Northrop Frye called the fictional "center of gravity". This movement indicated a literary change in heroic ethos from feudal aristocrat to urban democrat, as was the shift from epic to ironic narratives.

Huckleberry Finn (1884) has been called "the first antihero in the American nursery". Charlotte Mullen of Somerville and Ross's The Real Charlotte (1894) has been described as an anti-heroine.

The antihero became prominent in early 20th century existentialist works such as Franz Kafka's The Metamorphosis (1915), Jean-Paul Sartre's Nausea (1938), and Albert Camus's The Stranger (1942). The protagonist in these works is an indecisive central character who drifts through his life and is marked by boredom, angst, and alienation.

The antihero entered American literature in the 1950s and up to the mid-1960s as an alienated figure, unable to communicate. The American antihero of the 1950s and 1960s was typically more proactive than his French counterpart. The British version of the antihero emerged in the works of the "angry young men" of the 1950s. The collective protests of Sixties counterculture saw the solitary antihero gradually eclipsed from fictional prominence, though not without subsequent revivals in literary and cinematic form.

During the Golden Age of Television from the 2000s and into early 2020s, antiheroes such as Tony Soprano, Gru, Megamind, Jack Bauer, Gregory House, Dexter Morgan, Walter White, Frank Underwood, Don Draper, Neal Caffrey, Nucky Thompson, Jax Teller, Alicia Florrick, Annalise Keating, Selina Meyer and Kendall Roy became prominent in the most popular and critically acclaimed TV shows.

In his essay published in 2020, Postheroic Heroes - A Contemporary Image (german: Postheroische Helden - Ein Zeitbild), German sociologist Ulrich Bröckling examines the simultaneity of heroic and post-heroic role models as an opportunity to explore the place of the heroic in contemporary society. In contemporary art, artists such as the French multimedia artist Thomas Liu Le Lann negotiate in his series of Soft Heroes, in which overburdened, modern and tired Anti Heroes seem to have given up on the world around them.

Comic book anti-heroes

Main article: Comic book anti-heroIn American mainstream comic books, anti-heroes have become increasingly popular since the 1970s. The comic book version is generally a variation on the formula of superheroes. As Suzana Flores describes it, a comic book antihero is "often psychologically damaged, simultaneously depicted as superior due to his superhuman abilities and inferior due to his impetuousness, irrationality, or lack of thoughtful evaluation." Particularly well-known comic book anti-heroes include Wolverine, Punisher, Marv, Spawn, and Deadpool. These characters have all been adapted into feature films, as well.

See also

References

- ^ "Anti-Hero". Lexico. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 26 September 2020.

- Laham, Nicholas (2009). Currents of Comedy on the American Screen: How Film and Television Deliver Different Laughs for Changing Times. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co. p. 51. ISBN 9780786442645.

- Kennedy, Theresa Varney (2014). "'No Exit' in Racine's Phèdre: The Making of the Anti-Hero". The French Review. 88 (1): 165–178. doi:10.1353/tfr.2014.0114. ISSN 2329-7131. S2CID 256361158.

- Klapp, Orrin E. (September 1948). "The Creation of Popular Heroes". American Journal of Sociology. 54 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1086/220292. ISSN 0002-9602. S2CID 143440315.

- Petersen, Michael Bang (2019). "An Age of Chaos?". RSA Journal. 165 (3 (5579)): 44–47. ISSN 0958-0433. JSTOR 26907483.

- Klapp, Orrin E. (1948). "The Creation of Popular Heroes". American Journal of Sociology. 54 (2): 135–141. doi:10.1086/220292. ISSN 0002-9602. JSTOR 2771362. S2CID 143440315.

- ^ Steiner, George (2013). Tolstoy Or Dostoevsky: An Essay in the Old Criticism. New York: Open Road. pp. 197–207. ISBN 9781480411913.

- ^ "antihero". Encyclopædia Britannica. 14 February 2013. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- Wheeler, L. Lip. "Literary Terms and Definitions A". Dr. Wheeler's Website. Carson-Newman University. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Halliwell, Martin (2007). American Culture in the 1950s. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 60. ISBN 9780748618859.

- Kotru, Umesh; Zutshi, Ashutosh (1 March 2015). Karna The Unsung Hero of the Mahabharata. One Point Six Technology Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-93-5201-304-3.

- "Antihero". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 3 October 2013.

- Wheeler, L. Lip. "Literary Terms and Definitions B". Dr. Wheeler's Website. Carson-Newman University. Retrieved 6 September 2014.

- Alsen, Eberhard (2014). The New Romanticism: A Collection of Critical Essays. Hoboken: Taylor & Francis. p. 72. ISBN 9781317776000. Retrieved 20 April 2015 – via Google Books.

- Simmons, David (2008). The Anti-Hero in the American Novel: From Joseph Heller to Kurt Vonnegut (1st ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 9780230612525. Retrieved 20 April 2015 – via Google Books.

- Lutz, Deborah (2006). The Dangerous Lover: Gothic Villains, Byronism, and the Nineteenth-century Seduction Narrative. Columbus: Ohio State University Press. p. 82. ISBN 9780814210345. Retrieved 20 April 2015 – via Google Books.

- ^ Frye, Northrop (2002). Anatomy of Criticism. London: Penguin. p. 34. ISBN 9780141187099.

- Hearn, Michael Patrick (2001). The Annotated Huckleberry Finn: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Tom Sawyer's Comrade) (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. xvci. ISBN 0393020398.

- Ehnenn, Jill R. (2008). Women's Literary Collaboration, Queerness, and Late-Victorian Culture. Ashgate Publishing. p. 159. ISBN 9780754652946. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Google Books.

- Cooke, Rachel (27 February 2011). "The 10 best Neglected literary classics – in pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 7 April 2020.

- Woodcock, George (1 April 1983). Twentieth Century Fiction. Macmillan Publishers Ltd. p. 628. ISBN 9781349170661. Retrieved 7 April 2020 – via Google Books.

- Barnhart, Joe E. (2005). Dostoevsky's Polyphonic Talent. Lanham: University Press of America. p. 151. ISBN 9780761830979.

- Asong, Linus T. (2012). Psychological Constructs and the Craft of African Fiction of Yesteryears: Six Studies. Mankon: Langaa Research & Publishing CIG. p. 76. ISBN 9789956727667 – via Google Books.

- Gargett, Graham (2004). Heroism and Passion in Literature: Studies in Honour of Moya Longstaffe. Amsterdam: Rodopi. p. 198. ISBN 9789042016927 – via Google Books.

- Brereton, Geoffrey (1968). A Short History of French Literature. Penguin Books. pp. 254–255.

- ^ Hardt, Michael; Weeks, Kathi (2000). The Jameson Reader (Reprint ed.). Oxford, UK ; Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell. pp. 294–295. ISBN 9780631202707.

- ^ Edelstein, Alan (1996). Everybody is Sitting on the Curb: How and why America's Heroes Disappeared. Westport, Connecticut: Praeger. pp. 1, 18. ISBN 9780275953645.

- Ousby, Ian (1996). The Cambridge Paperback Guide to Literature in English. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780521436274.

- "Accueil". Fonds cantonal d'art contemporain. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- Reese, Hope (11 July 2013). "Why Is the Golden Age of TV So Dark?". The Atlantic. Retrieved 31 October 2021.

A new book explains the link between the rise of antihero protaganists and the unprecedented abundance of great TV (and what Dick Cheney has to do with it).

- Faithfull, E. (2021). How House brought the "savant anti-hero" into the mainstream and changed TV dramas. www.nine.com.au. https://www.nine.com.au/entertainment/latest/house-savant-anti-hero-medical-drama-9now/0e030210-8bfe-424f-b687-f2e36e6f0694

- Pruner, A. (n.d.). Hear us out: Gregory House was TV's last great doctor. https://editorial.rottentomatoes.com/article/hear-us-out-gregory-house-was-tvs-last-great-doctor/

- deutschlandfunk.de (5 March 2020). "Ulrich Bröckling: "Postheroische Helden" - Man hüte sich vor Helden!". Deutschlandfunk (in German). Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- "Soft Heroes". Documents d’artistes Genève (in French). Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- "Thomas Liu Le Lann: Wer ist Milo?". gallerytalk.net (in German). 10 May 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2024.

- Flores 2018, p. 146-147.

Bibliography

- Flores, Suzana E. (2018). Untamed: The Psychology of Marvel's Wolverine. McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-1-4766-7442-1.

External links

| Comics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glossary of comics terminology | |||||||||||

| Formats | |||||||||||

| Techniques | |||||||||||

| Creators |

| ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| Comics studies and narratology |

| ||||||||||

| By country |

| ||||||||||

| Lists |

| ||||||||||

| Collections and museums |

| ||||||||||

| Schools | |||||||||||

| Organizations |

| ||||||||||

| Stock characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||