| Revision as of 07:21, 21 May 2008 editDelldot on a public computer (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers1,985 edits ce, italics mostly← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 09:38, 17 November 2024 edit undo46.253.36.102 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Inherited neurodegenerative disorder}} | |||

| {{Infobox Disease | | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2017}} | |||

| Name = {{PAGENAME}} | | |||

| {{Use American English|date=December 2017}} | |||

| Image = georgehuntington.jpg | | |||

| {{cs1 config|name-list-style=vanc|display-authors=6}} | |||

| Caption = ]'s 1872 paper described the disorder. | | |||

| {{Infobox medical condition (new) | |||

| DiseasesDB = 6060 | | |||

| |

| name = Huntington's disease | ||

| |

| image = Neuron with mHtt inclusion.jpg | ||

| | alt = Several neurons colored yellow and having a large central core with up to two dozen tendrils branching out of them, the core of the neuron in the foreground contains an orange blob about a quarter of its diameter | |||

| ICDO = | | |||

| | caption = An edited microscopic image of a ] (yellow) with an ] (orange), which occurs as part of the disease process (image width 360 ]) | |||

| OMIM = 143100 | | |||

| | synonyms = Huntington's chorea | |||

| MedlinePlus = | | |||

| | field = ] | |||

| eMedicineSubj = | | |||

| | symptoms = Problems with motor skills including coordination and gait, mood, and mental abilities<ref name="Day20152"/><ref name=War2020/> | |||

| eMedicineTopic = | | |||

| | complications = ], ], physical injury from falls, ]<ref name=Frank2014/> | |||

| MeshID = D006816 | | |||

| | onset = 30{{ndash}}50 years old<ref name=NIH2020/> | |||

| | duration = Long term<ref name=NIH2020/> | |||

| | causes = ] (inherited or new mutation)<ref name=NIH2020/> | |||

| | risks = | |||

| | diagnosis = ]<ref name=Durr2012/> | |||

| | differential = ], ], ], ], ]<ref>{{cite book| vauthors = Ferri FF |title=Ferri's differential diagnosis: a practical guide to the differential diagnosis of symptoms, signs, and clinical disorders|date=2010|publisher=Elsevier/Mosby|location=Philadelphia, PA|isbn=978-0-323-07699-9 |page=Chapter H|edition=2nd}}</ref> | |||

| | prevention = | |||

| | treatment = ]<ref name=War2020/> | |||

| | medication = ]<ref name=Frank2014/> | |||

| | prognosis = 15{{ndash}}20 years from onset of symptoms<ref name=NIH2020/> | |||

| | frequency = 4{{ndash}}15 in 100,000 (European descent)<ref name="Day20152"/> | |||

| | named after = ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| <!-- Definitions and symptoms --> | |||

| '''Huntington's disease''', also called '''Huntington's chorea''', '''chorea major''', or '''HD''', is a ] ] inherited by approximately 3 to 7 per 100,000 people of Western European descent, varying geographically, down to 1 per 1,000,000 of Asian and African descent.<ref>{{cite web|title=Huntington's Disease|author=NCBI OMIM|url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/query.fcgi?cmd=Retrieve&db=OMIM&dopt=Detailed&tmpl=dispomimTemplate&list_uids=143100#143100_POPULATION_GENETICS' |accessdate=2008-05-22}}</ref> The name is derived from the physician ] who described it precisely in 1872. The disorder has been heavily researched in the last few decades, and it was one of the first inherited ]s for which an accurate test could be performed. | |||

| Huntington's disease's most obvious symptoms are abnormal body movements called ] and a lack of coordination, but it also affects a number of mental abilities and some aspects of behavior. Physical symptoms occur in a large range of ages around a ] occurrence of late forties/early fifties, but if they occur before the age of 20 then the condition is known as '''Juvenile HD'''. As there is currently no proven cure, symptoms are managed with various medications and supportive services. | |||

| '''Huntington's disease''' ('''HD'''), also known as '''Huntington's chorea''', is an incurable ]<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/huntingtons-disease/treatment/ | title=Huntington's disease - Treatment and support | date=23 October 2017 | work = National Health Service UK | access-date=6 May 2023 | archive-date=6 May 2023 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230506014916/https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/huntingtons-disease/treatment/ | url-status=live }}</ref> that is mostly ].<ref name="Illarioshkin_2018">{{cite journal | vauthors = Illarioshkin SN, Klyushnikov SA, Vigont VA, Seliverstov YA, Kaznacheyeva EV | title = Molecular Pathogenesis in Huntington's Disease | journal = Biochemistry. Biokhimiia | volume = 83 | issue = 9 | pages = 1030–1039 | date = September 2018 | pmid = 30472941 | doi = 10.1134/S0006297918090043 | s2cid = 26471825 |url=http://protein.bio.msu.ru/biokhimiya/contents/v83/full/83091299.html#Ref4 | via = protein.bio.msu.ru |access-date=8 November 2020 |archive-date=13 November 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201113121719/http://protein.bio.msu.ru/biokhimiya/contents/v83/full/83091299.html#Ref4 |url-status=live }}</ref> The earliest symptoms are often subtle problems with mood or mental/psychiatric abilities.<ref name="Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sudhakar V, Richardson RM | title = Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative Diseases | journal = Neurotherapeutics | volume = 16 | issue = 1 | pages = 166–175 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30542906 | pmc = 6361055 | doi = 10.1007/s13311-018-00694-0 }}</ref><ref name="Day20152"/> A general ] and an unsteady ] often follow.<ref name=War2020>{{cite journal | vauthors = Caron NS, Wright GE, Hayden MR | title = Huntington Disease | journal = GeneReviews | date = 2020 | pmid = 20301482 | veditors = Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJ, Stephens K, Amemiya A }}</ref> It is also a ] causing a ] ] known as ].<ref name="Robbins">{{cite book |title=Robbins basic pathology |vauthors=Kumar, Abbas A, Aster J |date=2018 |publisher=Elsevier |isbn=978-0-323-35317-5 |edition=Tenth |location=Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |page=879}}</ref><ref name="Purves">{{cite book | vauthors = Purves D |title=Neuroscience |date=2012 |location=Sunderland, Mass. | publisher = Sinauer Associates |isbn=978-0-87893-695-3 |page=415 |edition=5th}}</ref> As the disease advances, uncoordinated, involuntary body movements of chorea become more apparent.<ref name="Day20152"/> Physical abilities gradually worsen until ] becomes difficult and the person is unable to talk.<ref name="Day20152"/><ref name=War2020/> ] generally decline into ], depression, apathy, and impulsivity at times.<ref name="Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative"/><ref name="The Biology of Huntingtin">{{cite journal | vauthors = Saudou F, Humbert S | title = The Biology of Huntingtin | journal = Neuron | volume = 89 | issue = 5 | pages = 910–926 | date = March 2016 | pmid = 26938440 | doi = 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.02.003 | s2cid = 8272667 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref name="Frank2014" /> The specific symptoms vary somewhat between people.<ref name="Day20152"/> Symptoms usually begin between 30 and 50 years of age, and can start at any age but are usually seen around the age of 40.<ref name="The Biology of Huntingtin"/><ref name="Gene Therapy for Neurodegenerative"/><ref name="Frank2014" /><ref name="NIH2020">{{cite web |title=Huntington's Disease Information Page | work = National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke |url=https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease-Information-Page |access-date=14 December 2020 |archive-date=13 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201213025651/https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease-Information-Page |url-status=live }}</ref> The disease may develop earlier in ].<ref name="Day20152"/> About eight percent of cases start before the age of 20 years, and are known as ''juvenile HD'', which typically present with the ] of ] rather than those of chorea.<ref name=Frank2014/> | |||

| <!-- Note: Huntingtin protein and gene are correctly spelled with an 'i' in place of the 'o'. --> | |||

| Huntington's disease is one of several ] diseases caused by a ]. This expansion is in the ] ], which codes for ] (Htt), producing mutant Huntingtin (mHtt). The misfunction of this protein increases mitochondrial dysfunction and ]al ] in select areas of the ] as the normal age-related decline in general brain cell function means that the cells eventually can no longer handle the mutant protein, usually at around 40-50 years of age. This damage itself isn't fatal, but complications caused by its symptoms reduce life expectancy. | |||

| <!-- Cause and diagnosis --> | |||

| == Symptoms == | |||

| HD is typically ], who carries a ] in the ] (''HTT'').<ref name=NIH2020/> However, up to 10% of cases are due to a new mutation.<ref name="Day20152"/> The huntingtin gene provides the genetic information for ] (Htt).<ref name="Day20152"/> Expansion of ]s of ]-]-] (known as a ]) in the gene coding for the huntingtin protein results in an abnormal mutant protein (mHtt), which gradually damages ] through a number of possible mechanisms.<ref name="Illarioshkin_2018"/><ref name="hdprimer"/> The mutant protein is ], so having one parent who is a carrier of the trait is sufficient to trigger the disease in their children. Diagnosis is by ], which can be carried out at any time, regardless of whether or not symptoms are present.<ref name=Durr2012>{{cite journal | vauthors = Durr A, Gargiulo M, Feingold J | title = The presymptomatic phase of Huntington disease | journal = Revue Neurologique | volume = 168 | issue = 11 | pages = 806–808 | date = November 2012 | pmid = 22902173 | doi = 10.1016/j.neurol.2012.07.003 }}</ref> This fact raises several ethical debates: the age at which an individual is considered mature enough to choose testing; whether parents have the right to have their children tested; and managing confidentiality and disclosure of test results.<ref name=War2020/> | |||

| Onset of symptoms does not occur suddenly, but they increase in severity progressively, often becoming noticeable in stages. Quite often, physical signs are the first noticed, followed by ] and ] ones. In many cases, psychiatric changes, which pre-empt the physical ones, are overlooked. Physical symptoms are almost always evident; cognitive symptoms which can lead to ] problems exhibit differently from person to person. | |||

| === Physical === | |||

| Most people with Huntington's Disease eventually exhibit jerky, random, and uncontrollable movements called ], although some exhibit very slow movement and stiffness (], ]). These abnormal movements are initially exhibited as general lack of coordination and an unsteady ] and gradually increase as the disease progresses; this eventually causes problems with loss of facial expression (called "masks in movement") or exaggerated facial gestures, inability to walk, sit or stand stably, ] (slurring of words) and some uncontrollable movement of the lips, chewing and swallowing (]) which commonly causes weight loss.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Gaba AM, Zhang K, Marder K, Moskowitz CB, Werner P, Boozer CN |title=Energy balance in early-stage Huntington disease |journal=Am. J. Clin. Nutr. |volume=81 |issue=6 |pages=1335–41 |year=2005 |pmid=15941884 |doi=}}</ref><ref>{{dead link|date=May 2008}}Booklet by the Huntington Society of Canada, retrieved 2007-04-11.</ref> Continence, eating and mobility are extremely difficult if not impossible. | |||

| <!-- Treatment, epidemiology, and prognosis --> | |||

| Counterintuitively, there may be some health benefits: carriers of the gene are hypothesized to have higher levels of the tumor suppressor ] and a better than average immune system than non-carriers, although to date neither of these hypotheses has been supported with rigorous study.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Eskenazi BR, Wilson-Rich NS, Starks PT |title=A Darwinian approach to Huntington's disease: Subtle health benefits of a neurological disorder |journal=Med. Hypotheses |volume=69 |issue=6 |pages=1183–9 |year=2007 |pmid=17689877 |doi=10.1016/j.mehy.2007.02.046 |url=}}</ref> | |||

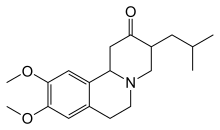

| No cure for HD is known, and full-time care is required in the later stages.<ref name=War2020/> Treatments can relieve some symptoms and in some, improve ].<ref name=Frank2014/> The best evidence for treatment of the movement problems is with ].<ref name=Frank2014/> HD affects about 4 to 15 in 100,000 people of European descent.<ref name="Day20152">{{cite journal | vauthors = Dayalu P, Albin RL | title = Huntington disease: pathogenesis and treatment | journal = Neurologic Clinics | volume = 33 | issue = 1 | pages = 101–114 | date = February 2015 | pmid = 25432725 | doi = 10.1016/j.ncl.2014.09.003 }}</ref><ref name=Frank2014/> It is rare among the Finnish and Japanese, while the occurrence rate in Africa is unknown.<ref name=Frank2014/> The disease affects males and females equally.<ref name=Frank2014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Frank S | title = Treatment of Huntington's disease | journal = Neurotherapeutics | volume = 11 | issue = 1 | pages = 153–160 | date = January 2014 | pmid = 24366610 | pmc = 3899480 | doi = 10.1007/s13311-013-0244-z }}</ref> Complications such as ], ], and physical injury from falls reduce life expectancy; although fatal aspiration pneumonia is commonly cited as the ultimate cause of death for those with the condition.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Aspiration Pneumonia: What It Is, Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment |url=https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21954-aspiration-pneumonia |access-date=2023-06-12 |website=Cleveland Clinic |language=en |archive-date=12 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230612211926/https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21954-aspiration-pneumonia |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="The Biology of Huntingtin"/><ref name=Frank2014/> ] is the cause of death in about 9% of cases.<ref name=Frank2014/> Death typically occurs 15–20 years from when the disease was first detected.<ref name=NIH2020/> | |||

| <!-- History and research --> | |||

| === Cognitive === | |||

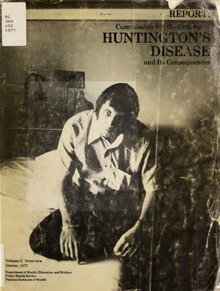

| The earliest known description of the disease was in 1841 by American physician Charles Oscar Waters.<ref name=History2015/> The condition was described in further detail in 1872 by American physician ].<ref name=History2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vale TC, Cardoso F | title = Chorea: A Journey through History | journal = Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements | volume = 5 | date = 2015 | pmid = 26056609 | pmc = 4454991 | doi = 10.7916/D8WM1C98 | doi-broken-date = 1 November 2024 }}</ref> The genetic basis was discovered in 1993 by an international collaborative effort led by the ].<ref name=Research2016>{{cite web |title=About Huntington's Disease |url=https://www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease |website=Genome.gov |access-date=13 January 2021 |language=en |archive-date=9 January 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210109070041/https://www.genome.gov/Genetic-Disorders/Huntingtons-Disease |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="HDF-About Us"/> Research and ] began forming in the late 1960s to increase public awareness, provide support for individuals and their families and promote research.<ref name="HDF-About Us">{{cite web|url=http://hdfoundation.org/history-of-the-hdf/|title=History of the HDF|publisher=Hereditary Disease Foundation|access-date=18 November 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151119025644/http://hdfoundation.org/history-of-the-hdf/|archive-date=19 November 2015}}</ref><ref name="HDSA12020">{{cite web |title=History and Genetics of Huntington's Disease {{!}} Huntington's Disease Society of America |date=March 2019 |url=https://hdsa.org/what-is-hd/history-and-genetics-of-huntingtons-disease/ |access-date=14 December 2020 |archive-date=1 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201201060837/https://hdsa.org/what-is-hd/history-and-genetics-of-huntingtons-disease/ |url-status=live }}</ref> Research directions include determining the exact mechanism of the disease, improving ] to aid with research, testing of medications and their ] to treat symptoms or slow the progression of the disease, and studying procedures such as ] with the goal of replacing damaged or lost neurons.<ref name=Research2016/> | |||

| Selective cognitive abilities are progressively impaired, including ] (planning; cognitive flexibility, ], rule acquisition, initiating appropriate actions, and inhibiting inappropriate actions), ] function (slowing of thought processes to control muscles), ] and ] skills of self and surrounding environment, selection of correct methods of remembering information (but not actual ] itself), short-term memory, and ability to learn new skills, depending on the ] of the individual. | |||

| ==Signs and symptoms== | |||

| === Psychopathological === | |||

| Psychopathological symptoms vary more than cognitive and physical ones, and may include ], ], a reduced display of emotions (]) and decreased ability to recognize negative expressions like anger, disgust, fear or sadness in others,<ref name="pmid17584778">{{cite journal |author=Johnson SA, Stout JC, Solomon AC, ''et al'' |title=Beyond disgust: impaired recognition of negative emotions prior to diagnosis in Huntington's disease |journal=Brain |volume=130 |issue=Pt 7 |pages=1732–44 |year=2007 |pmid=17584778 |doi=10.1093/brain/awm107}}</ref> ], ], and ]. The latter can cause or worsen ] such as ] and ], or ]. | |||

| ] of Huntington's disease most commonly become noticeable between the ages of 30 and 50 years, but they can begin at any age<ref name=NIH2020/> and present as a ] of motor, cognitive, and psychiatric symptoms.<ref name=Jensen>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jensen RN, Bolwig T, Sørensen SA | title = | language = da | journal = Ugeskrift for Laeger | volume = 180 | issue = 13 | date = March 2018 | pmid = 29587954 }}</ref> When developed in an early stage, it is known as juvenile Huntington's disease.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=Huntington's disease - Symptoms and causes |url=https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/huntingtons-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20356117 |access-date=2022-12-13 |website=Mayo Clinic |language=en |archive-date=5 March 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180305034543/https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/huntingtons-disease/symptoms-causes/syc-20356117 |url-status=live }}</ref> In 50% of cases, the psychiatric symptoms appear first.<ref name=Jensen/> Their progression is often described in early stages, middle stages, and late stages with an earlier ] phase.<ref name=War2020/> In the early stages, subtle personality changes, problems in ] and physical skills, ], and mood swings occur, all of which may go unnoticed,<ref name="NHSScot">{{cite web |title=Huntington's disease |url=https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/brain-nerves-and-spinal-cord/huntingtons-disease |publisher=www.nhsinform.scot |access-date=12 July 2020 |language=en |archive-date=12 July 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200712181757/https://www.nhsinform.scot/illnesses-and-conditions/brain-nerves-and-spinal-cord/huntingtons-disease |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="genereviews">{{cite journal | vauthors = Caron NS, Wright GE, Hayden MR | title = Huntington Disease | journal = Genereviews Bookshelf | date = June 2020 | pmid = 20301482 | url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=huntington#huntington.Management | access-date = 22 November 2020 | publisher = University of Washington | archive-date = 10 February 2009 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090210161856/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=gene&part=huntington#huntington.Management | url-status = live }}</ref> and these usually precede the motor symptoms.<ref name="DSM5">{{cite book |title=Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. |date=2013 |publisher=American Psychiatric Association |location=Arlington, VA |isbn=978-0-89042-554-1 |page=639 |edition=5th}}</ref> Almost everyone with HD eventually exhibits similar physical symptoms, but the onset, progression, and extent of cognitive and behavioral symptoms vary significantly between individuals.<ref name="OxfordMonographclinical">{{cite book | vauthors = Kremer B |chapter=Clinical neurology of Huntington's disease |veditors=Bates G, Harper P, Jones L | title=Huntington's Disease – Third Edition| publisher=Oxford University Press| location=Oxford| year=2002| isbn=978-0-19-851060-4|pages=28–53}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|vauthors=Wagle AC, Wagle SA, Marková IS, Berrios GE |year=2000|title=Psychiatric Morbidity in Huntington's disease|journal=Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research|issue=8|pages=5–16}}</ref> | |||

| The most characteristic initial physical symptoms are jerky, random, and uncontrollable movements called ].<ref name="Robbins"/> Many people are not aware of their involuntary movements, or impeded by them.<ref name="Day20152"/> Chorea may be initially exhibited as general restlessness, small unintentionally initiated or uncompleted motions, lack of coordination, or slowed ].<ref name="lancet07">{{cite journal | vauthors = Walker FO | title = Huntington's disease | journal = Lancet | volume = 369 | issue = 9557 | pages = 218–228 | date = January 2007 | pmid = 17240289 | doi = 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60111-1 | s2cid = 46151626 }}</ref> These minor motor abnormalities usually precede more obvious signs of motor dysfunction by at least three years.<ref name="OxfordMonographclinical2">{{cite book |title=Huntington's Disease – Third Edition |vauthors=Kremer B |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2002 |isbn=978-0-19-851060-4 |veditors=Bates G, Harper P, Jones L |location=Oxford |pages=28–53 |chapter=Clinical neurology of Huntington's disease}}</ref> The clear appearance of symptoms such as rigidity, writhing motions, or ] appear as the disorder progresses.<ref name="lancet07" /> These are signs that the system in the brain that is responsible for movement has been affected.<ref name="pmid16496032">{{cite journal | vauthors = Montoya A, Price BH, Menear M, Lepage M | title = Brain imaging and cognitive dysfunctions in Huntington's disease | journal = Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience | volume = 31 | issue = 1 | pages = 21–29 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16496032 | pmc = 1325063 | url = http://www.cma.ca/multimedia/staticContent/HTML/N0/l2/jpn/vol-31/issue-1/pdf/pg21.pdf | url-status = dead | access-date = 17 September 2008 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20160323102506/https://www.cma.ca/multimedia/staticcontent/html/n0/l2/jpn/vol-31/issue-1/pdf/pg21.pdf | archive-date = 23 March 2016 }}</ref> ] functions become increasingly impaired, such that any action that requires muscle control is affected. When muscle control is affected such as rigidity or muscle contracture this is known as ]. Dystonia is a neurological hyperkinetic movement disorder that results in twisting or repetitive movements, that may resemble a tremor. Common consequences are physical instability, abnormal facial expression, and difficulties chewing, ], and ].<ref name="lancet07" /> ] and ] are also associated symptoms.<ref name="Dickey3">{{cite journal | vauthors = Dickey AS, La Spada AR | title = Therapy development in Huntington disease: From current strategies to emerging opportunities | journal = American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part A | volume = 176 | issue = 4 | pages = 842–861 | date = April 2018 | pmid = 29218782 | pmc = 5975251 | doi = 10.1002/ajmg.a.38494 }}</ref> Eating difficulties commonly cause weight loss and may lead to malnutrition.<ref name="pmid191655312">{{cite journal | vauthors = Aziz NA, van der Marck MA, Pijl H, Olde Rikkert MG, Bloem BR, Roos RA | title = Weight loss in neurodegenerative disorders | journal = Journal of Neurology | volume = 255 | issue = 12 | pages = 1872–1880 | date = December 2008 | pmid = 19165531 | doi = 10.1007/s00415-009-0062-8 | s2cid = 26109381 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=11 April 2007 |title=Booklet by the Huntington Society of Canada |url=http://www.hdac.org/caregiving/pdf/Caregiver_Handbook.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080625160929/http://www.hdac.org/caregiving/pdf/Caregiver_Handbook.pdf |archive-date=25 June 2008 |access-date=10 August 2008 |work=Caregiver's Handbook for Advanced-Stage Huntington Disease |publisher=HD Society of Canada}}</ref> Weight loss is common in people with Huntington's disease, and it progresses with the disease. Juvenile HD generally progresses at a faster rate with greater cognitive decline, and chorea is exhibited briefly, if at all; the Westphal variant of ], rigidity, and tremors is more typical in juvenile HD, as are ]s.<ref name="lancet07" /><ref name="Dickey3" /> | |||

| Cognitive abilities are progressively impaired and tend to generally decline into ].<ref name="Frank2014" /> Especially affected are ], which include planning, cognitive flexibility, ], rule acquisition, initiation of appropriate actions, and inhibition of inappropriate actions. Different cognitive impairments include difficulty focusing on tasks, lack of flexibility, a lack of impulse, a lack of awareness of one's own behaviors and abilities and difficulty learning or processing new information. As the disease progresses, ] deficits tend to appear. Reported impairments range from ] deficits to ] difficulties, including deficits in ] (memory of one's life), ] (memory of the body of how to perform an activity), and ].<ref name="pmid16496032"/> | |||

| Reported ] signs are ], ], a ], ], ], and ] and ].<ref name="pmid180708482">{{cite journal | vauthors = van Duijn E, Kingma EM, van der Mast RC | title = Psychopathology in verified Huntington's disease gene carriers | journal = The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences | volume = 19 | issue = 4 | pages = 441–448 | year = 2007 | pmid = 18070848 | doi = 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.19.4.441 }}</ref> Other common psychiatric disorders could include ], ], ] and ]. Difficulties in recognizing other people's negative expressions have also been observed.<ref name="pmid16496032"/> The ] of these symptoms is highly variable between studies, with estimated rates for lifetime prevalence of ] between 33 and 76%.<ref name="pmid180708482" /> For many with the disease and their families, these symptoms are among the most distressing aspects of the disease, often affecting daily functioning and constituting reason for ].<ref name="pmid180708482" /> Early behavioral changes in HD result in an increased risk of suicide.<ref name="Robbins"/> Often, individuals have reduced awareness of chorea, cognitive, and emotional impairments.<ref>{{cite book |title=Bradley's neurology in clinical practice |vauthors=Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH |publisher=Elsevier/Saunders |year=2012 |isbn=978-1-4377-0434-1 |veditors=Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J |edition=6th |location=Philadelphia, PA |page=108 |chapter=Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice}}</ref> | |||

| Mutant huntingtin is expressed throughout the body and associated with abnormalities in peripheral tissues that are directly caused by such expression outside the brain. These abnormalities include ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = van der Burg JM, Björkqvist M, Brundin P | title = Beyond the brain: widespread pathology in Huntington's disease | journal = The Lancet. Neurology | volume = 8 | issue = 8 | pages = 765–774 | date = August 2009 | pmid = 19608102 | doi = 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70178-4 | s2cid = 14419437 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Genetics== | ==Genetics== | ||

| <!-- Please note that although the disorder is spelled Huntington, the associated gene and protein are correctly spelled Huntingtin --> | |||

| {{see also|Trinucleotide repeat disorders}} | |||

| Everyone has two copies of the ] (''HTT''), which codes for the ] (Htt). ''HTT'' is also called the HD gene, and the ''IT15'' gene, (interesting ] 15). Part of this gene is a repeated section called a ] – a ], which varies in length between individuals, and may change length between generations. If the repeat is present in a healthy gene, a dynamic mutation may increase the repeat count and result in a defective gene. When the length of this repeated section reaches a certain threshold, it produces an altered form of the protein, called mutant huntingtin protein (mHtt). The differing functions of these proteins are the cause of pathological changes, which in turn cause the disease symptoms. The Huntington's disease mutation is genetically dominant and almost fully ]; mutation of either of a person's ''HTT'' alleles causes the disease. It is not inherited according to sex, but by the length of the repeated section of the gene; hence its severity can be influenced by the sex of the affected parent.<ref name="lancet07"/> | |||

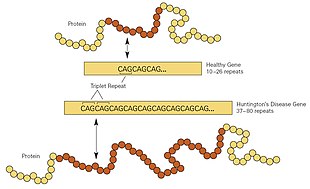

| The gene involved in Huntington's disease, called ] (HTT), or Interesting Transcript 15 (IT15) gene, known historically as the HD gene, is located on the short arm of ] (4p16.3). In the first part (5'end) of the HD gene, there is a sequence of three ] ]—]-]-] (CAG)—that is repeated multiple times (i.e. ...CAGCAGCAG...); this is called a ]. CAG is the ] for the ] ]; thus a series of CAG forms a chain of glutamine known as polyglutamine (polyQ). | |||

| ===Genetic mutation=== | |||

| HD is one of several ]s that are caused by the length of a repeated section of a gene exceeding a normal range.<ref name="lancet07" /> The ''HTT'' gene is located on the ] of ]<ref name="lancet07" /> at 4p16.3. ''HTT'' contains a sequence of three ]s—cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG)—repeated multiple times (i.e. ... CAGCAGCAG ...), known as a trinucleotide repeat.<ref name="lancet07" /> CAG is the three-letter ] (]) for the ] ], so a series of them results in the production of a chain of glutamine known as a ] (or polyQ tract), and the repeated part of the gene, the ''polyQ region''.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Katsuno M, Banno H, Suzuki K, Takeuchi Y, Kawashima M, Tanaka F, Adachi H, Sobue G | title = Molecular genetics and biomarkers of polyglutamine diseases | journal = Current Molecular Medicine | volume = 8 | issue = 3 | pages = 221–234 | date = May 2008 | pmid = 18473821 | doi = 10.2174/156652408784221298 }}</ref> | |||

| A polyQ length of less than 36 glutamines produces a ] ] called ] ('''Htt'''), whereas a sequence of 36 or more produces an erroneous form of Htt, '''mHtt''' (standing for mutant Htt). Reduced penetrance is found in counts 36-39 and results in later onset. No case of HD has been diagnosed with a count of less than 36.<ref>Chong, S.S., Almqvist, E., Telenius, H., LaTray, L., Nichol, K., Bourdelat-Parks, B., Goldberg, Y.P., Haddad, B.R., Richards, F., Sillence, D., Greenberg, C.R., Ives, E., Van den Engh, G., Hughes, M.R., and Hayden, M.R. (1997). Contribution of DNA sequence and CAG size to mutation frquences of intermediate alleles for Huntington Disease: Evidence from single sperm analyses. Human Molecular Genetics 6:302-309</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| {| class="wikitable" style="margin: |

{| class="wikitable" style="float:right; margin-left:15px; margin-right:15px; text-align:center;" | ||

| |+Classification of trinucleotide repeats, and resulting disease status, depending on the number of CAG repeats<ref name="lancet07" /> | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Repeat count | |||

| ! Effect | |||

| ! Classification | |||

| ! classification | |||

| ! Disease status | |||

| ! repeat count | |||

| ! Risk to offspring | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | <27 | |||

| | unnaffected | |||

| | |

| Normal | ||

| | Will not be affected | |||

| | < 27 | |||

| | None | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | | 27–35 | ||

| | Intermediate | |||

| | intermediate | |||

| | Will not be affected | |||

| | 27 - 35 | |||

| | Elevated, but <50% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | 36–39 | |||

| | affected | |||

| | Reduced Penetrance | | Reduced Penetrance | ||

| | May or may not be affected | |||

| | 36 - 39 | |||

| | 50% | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | | | 40+ | ||

| | Full |

| Full penetrance | ||

| | |

| Will be affected | ||

| | |

| 50% | ||

| |} | |||

| Generally, people have fewer than 36 repeated glutamines in the polyQ region, which results in the production of the ] protein huntingtin.<ref name="lancet07" /> However, a sequence of 36 or more glutamines results in the production of a protein with different characteristics.<ref name="lancet07" /> This altered form, called mutant huntingtin (mHtt), increases the decay rate of certain types of ]. Regions of the brain have differing amounts and reliance on these types of neurons and are affected accordingly.<ref name="lancet07" /> Generally, the number of CAG repeats is related to how much this process is affected, and accounts for about 60% of the variation of the age of the onset of symptoms. The remaining variation is attributed to the environment and other genes that modify the mechanism of HD.<ref name="lancet07" /> About 36 to 39 repeats result in a reduced-penetrance form of the disease, with a much later onset and slower progression of symptoms. In some cases, the onset may be so late that symptoms are never noticed.<ref name="lancet07" /> With very large repeat counts (more than 60), HD onset can occur below the age of 20, known as juvenile HD. Juvenile HD is typically of the Westphal variant that is characterized by slowness of movement, rigidity, and tremors. This accounts for about 7% of HD carriers.<ref name="Squitieri">{{cite journal | vauthors = Squitieri F, Frati L, Ciarmiello A, Lastoria S, Quarrell O | title = Juvenile Huntington's disease: does a dosage-effect pathogenic mechanism differ from the classical adult disease? | journal = Mechanisms of Ageing and Development | volume = 127 | issue = 2 | pages = 208–212 | date = February 2006 | pmid = 16274727 | doi = 10.1016/j.mad.2005.09.012 | s2cid = 20523093 }}</ref><ref name="juvenile">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nance MA, Myers RH | title = Juvenile onset Huntington's disease--clinical and research perspectives | journal = Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews | volume = 7 | issue = 3 | pages = 153–157 | year = 2001 | pmid = 11553930 | doi = 10.1002/mrdd.1022 }}</ref> | |||

| Having mHtt instead of Htt causes certain neurons in select areas of the brain to have an increased mortality, progressively interfering with their functioning. Generally, but not always, the greater the number of CAG repeats, the earlier the onset of symptoms.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kieburtz K, MacDonald M, Shih C, ''et al'' |title=Trinucleotide repeat length and progression of illness in Huntington's disease |journal=J. Med. Genet. |volume=31 |issue=11 |pages=872–4 |year=1994 |pmid=7853373 |doi=}}</ref> | |||

| ===Inheritance=== | ===Inheritance=== | ||

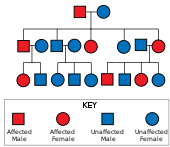

| ] fashion.]] | |||

| Huntington's disease is ], needing only one affected ] from either parent to inherit the disease. Although this generally means there is a one in two chance of inheriting the disorder from an affected parent, the inheritance of HD is more complex due to potential ]s, where ] doesn't produce an exact copy of itself. This can cause the number of repeats to change in successive generations. This can mean that a parent with a count close to the threshold, may pass on a gene with a count either side of the threshold. Repeat counts maternally inherited are usually similar, whereas paternally inherited ones tend to increase.<ref>{{cite journal| author=RM Ridley, CD Frith, TJ Crow and PM Conneally| title=Anticipation in Huntington's disease is inherited through the male line but may originate in the female| journal=Journal of Medical Genetics| year=1988| volume=25| pages=589-595| url=http://jmg.bmjjournals.com/cgi/content/abstract/25/9/589| pmid=2972838}}</ref> This potential increase in repeats in successive generations is known as ]. | |||

| ] fashion. The probability of each offspring inheriting an affected gene is 50%. Inheritance is independent of sex, and the phenotype does not skip generations.]] | |||

| ], in which neither parent has HD, are rare. | |||

| Huntington's disease has ] inheritance, meaning that an affected individual typically inherits one copy of the gene with an expanded trinucleotide repeat (the mutant ]) from an affected parent.<ref name="lancet07" /> Since the penetrance of the mutation is very high, those who have a mutated copy of the gene will have the disease. In this type of inheritance pattern, each offspring of an affected individual has a 50% risk of inheriting the mutant allele, so are affected with the disorder (see figure). This probability is sex-independent.<ref name="basicgenetics">{{cite book | vauthors =Passarge E | title=Color Atlas of Genetics | url =https://archive.org/details/coloratlasofgene0000pass | url-access =registration | publisher=Thieme | edition=2nd | year=2001 | page= | isbn=978-0-86577-958-7}}</ref> Sex-dependent or sex-linked genes are traits that are found on the X or Y chromosomes.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Sex Linked |url=https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Sex-Linked |access-date=2022-12-13 |website=Genome.gov |language=en |archive-date=14 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220414183337/https://www.genome.gov/genetics-glossary/Sex-Linked |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ] individuals (where both parents have HD) generally do not show an earlier onset of disease, but may have an increased rate of decline. | |||

| ] numbering over 28 are unstable during ], and this instability increases with the number of repeats present.<ref name="lancet07" /> This usually leads to new expansions as generations pass (]s) instead of reproducing an exact copy of the trinucleotide repeat.<ref name="lancet07" /> This causes the number of repeats to change in successive generations, such that an unaffected parent with an "intermediate" number of repeats (28–35), or "reduced penetrance" (36–40), may pass on a copy of the gene with an increase in the number of repeats that produces fully penetrant HD.<ref name="lancet07" /> The earlier ] and greater severity of disease in successive generations due to increases in the number of repeats is known as genetic ].<ref name="Day20152"/> Instability is greater in ] than ];<ref name="lancet07" /> maternally inherited alleles are usually of a similar repeat length, whereas paternally inherited ones have a higher chance of increasing in length.<ref name="lancet07" /><ref name="Ridley">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ridley RM, Frith CD, Crow TJ, Conneally PM | title = Anticipation in Huntington's disease is inherited through the male line but may originate in the female | journal = Journal of Medical Genetics | volume = 25 | issue = 9 | pages = 589–595 | date = September 1988 | pmid = 2972838 | pmc = 1051535 | doi = 10.1136/jmg.25.9.589 }}</ref> Rarely is Huntington's disease caused by a ], where neither parent has over 36 CAG repeats.<ref name="pmid16965319">{{cite journal | vauthors = Semaka A, Creighton S, Warby S, Hayden MR | title = Predictive testing for Huntington disease: interpretation and significance of intermediate alleles | journal = Clinical Genetics | volume = 70 | issue = 4 | pages = 283–294 | date = October 2006 | pmid = 16965319 | doi = 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00668.x | s2cid = 26007984 }}</ref> | |||

| ==Mechanism== | |||

| {{see also|Huntingtin protein}} | |||

| Like all proteins, Htt and mHtt are ], perform or affect ] functioning, and are finally cleared up in a process called degradation. The exact mechanism in which mHtt causes or affects the biological processes of DNA replication and programmed cell death (]) remains unclear, so research is divided into identifying the functioning of Htt, how mHtt differs or interferes with it, and the ] effects of remnants of the protein (known as aggregates) left after degradation. | |||

| In the rare situations where both parents have an expanded HD gene, the risk increases to 75%, and when either parent has two expanded copies, the risk is 100% (all children will be affected). Individuals with ] are rare. For some time, HD was thought to be the only disease for which possession of a second mutated gene did not affect symptoms and progression,<ref name="pmid2881213">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wexler NS, Young AB, Tanzi RE, Travers H, Starosta-Rubinstein S, Penney JB, Snodgrass SR, Shoulson I, Gomez F, Ramos Arroyo MA | title = Homozygotes for Huntington's disease | journal = Nature | volume = 326 | issue = 6109 | pages = 194–197 | year = 1987 | pmid = 2881213 | doi = 10.1038/326194a0 | hdl-access = free | s2cid = 4312171 | bibcode = 1987Natur.326..194W | hdl = 2027.42/62543 }}</ref> but it has since been found that it can affect the ] and the rate of progression.<ref name="lancet07" /><ref name="pmid12615650">{{cite journal | vauthors = Squitieri F, Gellera C, Cannella M, Mariotti C, Cislaghi G, Rubinsztein DC, Almqvist EW, Turner D, Bachoud-Lévi AC, Simpson SA, Delatycki M, Maglione V, Hayden MR, Donato SD | title = Homozygosity for CAG mutation in Huntington disease is associated with a more severe clinical course | journal = Brain | volume = 126 | issue = Pt 4 | pages = 946–955 | date = April 2003 | pmid = 12615650 | doi = 10.1093/brain/awg077 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| ===Function=== | |||

| Htt is involved in ] trafficking as it interacts with HIT1, a ] binding protein, to mediate ], the absorption of materials into a cell.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Velier J, Kim M, Schwarz C, ''et al'' |title=Wild-type and mutant huntingtins function in vesicle trafficking in the secretory and endocytic pathways |journal=Exp. Neurol. |volume=152 |issue=1 |pages=34–40 |year=1998 |pmid=9682010 |doi=10.1006/exnr.1998.6832}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Waelter S, Scherzinger E, Hasenbank R, ''et al'' |title=The huntingtin interacting protein HIP1 is a clathrin and alpha-adaptin-binding protein involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis |journal=Hum. Mol. Genet. |volume=10 |issue=17 |pages=1807–17 |year=2001 |pmid=11532990 |doi= | doi = 10.1093/hmg/10.17.1807 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> | |||

| ==Mechanisms== | |||

| mHtt reduces the production of ] (BDNF) which protects neurons in the ].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Canals JM, Pineda JR, Torres-Peraza JF, ''et al'' |title=Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates the onset and severity of motor dysfunction associated with enkephalinergic neuronal degeneration in Huntington's disease |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=24 |issue=35 |pages=7727–39 |year=2004 |pmid=15342740 |doi=10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1197-04.2004}}</ref> This loss of BDNF may contribute to striatal cell death, which does not follow apoptotic pathways as the neurons appear to die of starvation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Sawa A, Nagata E, Sutcliffe S, ''et al'' |title=Huntingtin is cleaved by caspases in the cytoplasm and translocated to the nucleus via perinuclear sites in Huntington's disease patient lymphoblasts |journal=Neurobiol. Dis. |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=267–74 |year=2005 |pmid=15890517 |doi=10.1016/j.nbd.2005.02.013}}</ref> | |||

| Huntingtin protein interacts with over 100 other proteins, and appears to have multiple functions.<ref name="pmid15383276">{{cite journal | vauthors = Goehler H, Lalowski M, Stelzl U, Waelter S, Stroedicke M, Worm U, Droege A, Lindenberg KS, Knoblich M, Haenig C, Herbst M, Suopanki J, Scherzinger E, Abraham C, Bauer B, Hasenbank R, Fritzsche A, Ludewig AH, Büssow K, Coleman SH, Gutekunst CA, Landwehrmeyer BG, Lehrach H, Wanker EE | title = A protein interaction network links GIT1, an enhancer of huntingtin aggregation, to Huntington's disease | journal = Molecular Cell | volume = 15 | issue = 6 | pages = 853–865 | date = September 2004 | pmid = 15383276 | doi = 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.09.016 | author23-link = Bernhard Landwehrmeyer | doi-access = free }}</ref> The behavior of the mutated protein (mHtt) is not completely understood, but it is toxic to certain cell types, particularly ]. Early damage is most evident in the ] ], initially in the ], but as the disease progresses, other areas of the brain are also affected, including regions of the ]. Early symptoms are attributable to functions of the striatum and its cortical connections—namely control over movement, mood, and higher cognitive function.<ref name="lancet07" /> ] also appears to be changed in HD.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Glajch KE, Sadri-Vakili G | title = Epigenetic Mechanisms Involved in Huntington's Disease Pathogenesis | journal = Journal of Huntington's Disease | volume = 4 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–15 | date = 2015 | pmid = 25813218 | doi = 10.3233/JHD-159001 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Huntingtin function=== | ||

| {{See also|Huntingtin#Function}} | |||

| Both Htt and mHtt are cleaved (the first step in degradation) by ], which removes the protein's amino end (the ]).<ref>{{cite journal |author=Kim YJ, Yi Y, Sapp E, ''et al'' |title=Caspase 3-cleaved N-terminal fragments of wild-type and mutant huntingtin are present in normal and Huntington's disease brains, associate with membranes, and undergo calpain-dependent proteolysis |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=98 |issue=22 |pages=12784–9 |year=2001 |pmid=11675509 |doi=10.1073/pnas.221451398}}</ref> Caspase-2 then further breaks down the amino terminal fragment (the part with the CAG repeat) of Htt, but cannot act upon all of the repeats of mHtt.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Hermel E, Gafni J, Propp SS, ''et al'' |title=Specific caspase interactions and amplification are involved in selective neuronal vulnerability in Huntington's disease |journal=Cell Death Differ. |volume=11 |issue=4 |pages=424–38 |year=2004 |pmid=14713958 |doi=10.1038/sj.cdd.4401358}}</ref> These repeats left in the cell, called aggregates or N-fragments, are able to affect polyQ dependent ].<ref>{{cite journal |author=Freiman RN, Tjian R |title=Neurodegeneration. A glutamine-rich trail leads to transcription factors |journal=Science |volume=296 |issue=5576 |pages=2149–50 |year=2002 |pmid=12077389 |doi=10.1126/science.1073845}}</ref> Specifically, mHtt binds with TAF<sub>II</sub>130, a coactivator to ] dependent transcription.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Bae BI, Xu H, Igarashi S, ''et al'' |title=p53 mediates cellular dysfunction and behavioral abnormalities in Huntington's disease |journal=Neuron |volume=47 |issue=1 |pages=29–41 |year=2005 |pmid=15996546 |doi=10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.005}}</ref> The aggregates also interact with SP<sub>1</sub>, thereby preventing it from binding to ],the normal functioning of these proteins.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Dunah AW, Jeong H, Griffin A, ''et al'' |title=Sp1 and TAFII130 transcriptional activity disrupted in early Huntington's disease |journal=Science |volume=296 |issue=5576 |pages=2238–43 |year=2002 |pmid=11988536 |doi=10.1126/science.1072613}}</ref> | |||

| Htt is ] in all cells, with the highest concentrations found in the brain and ], and moderate amounts in the ], ], and ]s. Its functions are unclear, but it does interact with proteins involved in ], ], and ].<ref name="Liu"/> In ] to exhibit HD, several functions of Htt have been identified.<ref name="Httfunction">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cattaneo E, Zuccato C, Tartari M | title = Normal huntingtin function: an alternative approach to Huntington's disease | journal = Nature Reviews. Neuroscience | volume = 6 | issue = 12 | pages = 919–930 | date = December 2005 | pmid = 16288298 | doi = 10.1038/nrn1806 | s2cid = 10119487 }}</ref> In these animals, Htt is important for embryonic development, as its absence is related to embryonic death. ], an enzyme which plays a role in catalyzing ], is thought to be activated by the mutated gene through damaging the ubiquitin-protease system. It also acts as an ] agent preventing ] and controls the production of ], a protein that protects neurons and regulates their creation during ]. Htt also facilitates ] and ], and controls neuronal gene transcription.<ref name="Httfunction"/> If the expression of Htt is increased, ] survival is improved and the effects of mHtt are reduced, whereas when the expression of Htt is reduced, the resulting characteristics are more as seen in the presence of mHtt.<ref name="Httfunction"/> Accordingly, the disease is thought not to be caused by ] of Htt, but by a ] of mHtt in the body.<ref name="lancet07" /> | |||

| ===Cellular changes=== | |||

| In transgenic mice neurodegeneration caused by mHtt is related to the ] enzyme cleaving the Htt protein, as they did not show effects of HD in experiments.<ref name="pmid16777606">{{cite journal |author=Graham RK, Deng Y, Slow EJ, ''et al'' |title=Cleavage at the caspase-6 site is required for neuronal dysfunction and degeneration due to mutant huntingtin |journal=Cell |volume=125 |issue=6 |pages=1179–91 |year=2006 |pmid=16777606 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.026}}</ref> | |||

| ] (stained orange) caused by HD, image width 250 ]]] | |||

| In genetically altered "knockin" mice, the extended CAG repeat portion of the gene is all that is needed to cause disease.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Murphy KP, Carter RJ, Lione LA, ''et al'' |title=Abnormal synaptic plasticity and impaired spatial cognition in mice transgenic for exon 1 of the human Huntington's disease mutation |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=20 |issue=13 |pages=5115–23 |year=2000 |pmid=10864968 |doi=}}</ref> Aggregates of mHtt are present in the brains of both HD patients<ref name="pmid9302293">{{cite journal |author=DiFiglia M, Sapp E, Chase KO, ''et al'' |title=Aggregation of huntingtin in neuronal intranuclear inclusions and dystrophic neurites in brain |journal=Science |volume=277 |issue=5334 |pages=1990–3 |year=1997 |pmid=9302293 |doi=10.1126/science.277.5334.1990}}</ref> and HD mice,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Davies SW, Turmaine M, Cozens BA, ''et al'' |title=Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation |journal=Cell |volume=90 |issue=3 |pages=537–48 |year=1997 |pmid=9267033 |doi= | doi = 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80513-9 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> and are most prevalent in ], less so in ] and almost absent in most other brain regions including the ] and ].<ref name="pmid9302293"/><ref>{{cite journal |author=Gutekunst CA, Li SH, Yi H, ''et al'' |title=Nuclear and neuropil aggregates in Huntington's disease: relationship to neuropathology |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=19 |issue=7 |pages=2522–34 |year=1999 |pmid=10087066 |doi=}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |author=Sieradzan KA, Mechan AO, Jones L, Wanker EE, Nukina N, Mann DM |title=Huntington's disease intranuclear inclusions contain truncated, ubiquitinated huntingtin protein |journal=Exp. Neurol. |volume=156 |issue=1 |pages=92–9 |year=1999 |pmid=10192780 |doi=10.1006/exnr.1998.7005}}</ref> These aggregates consist mainly of the amino terminal end of mHtt (CAG repeat), and are found in both the ] and ] of neurons.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cooper JK, Schilling G, Peters MF, ''et al'' |title=Truncated N-terminal fragments of huntingtin with expanded glutamine repeats form nuclear and cytoplasmic aggregates in cell culture |journal=Hum. Mol. Genet. |volume=7 |issue=5 |pages=783–90 |year=1998 |pmid=9536081 |doi= | doi = 10.1093/hmg/7.5.783 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> The presence of these aggregates however does not correlate with cell death.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Fusco FR, Chen Q, Lamoreaux WJ, ''et al'' |title=Cellular localization of huntingtin in striatal and cortical neurons in rats: lack of correlation with neuronal vulnerability in Huntington's disease |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=19 |issue=4 |pages=1189–202 |year=1999 |pmid=9952397 |doi=}}</ref> Thus mHtt acts in the nucleus but does not cause apoptosis through aggregation.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Saudou F, Finkbeiner S, Devys D, Greenberg ME |title=Huntingtin acts in the nucleus to induce apoptosis but death does not correlate with the formation of intranuclear inclusions |journal=Cell |volume=95 |issue=1 |pages=55–66 |year=1998 |pmid=9778247 |doi= | doi = 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81782-1 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref> | |||

| The toxic action of mHtt may manifest and produce the HD pathology through multiple cellular changes.<ref name="pmid14585171">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rubinsztein DC, Carmichael J | title = Huntington's disease: molecular basis of neurodegeneration | journal = Expert Reviews in Molecular Medicine | volume = 5 | issue = 20 | pages = 1–21 | date = August 2003 | pmid = 14585171 | doi = 10.1017/S1462399403006549 | s2cid = 28435830 }}</ref><ref name="pmid2136787">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bloch M, Hayden MR | title = Opinion: predictive testing for Huntington disease in childhood: challenges and implications | journal = American Journal of Human Genetics | volume = 46 | issue = 1 | pages = 1–4 | date = January 1990 | pmid = 2136787 | pmc = 1683548 }}</ref> In its mutant (polyglutamine expanded) form, the protein is more prone to cleavage that creates shorter fragments containing the polyglutamine expansion.<ref name="pmid14585171"/> These protein fragments have a propensity to undergo ] and aggregation, yielding fibrillar aggregates in which non-native polyglutamine β-strands from multiple proteins are bonded together by hydrogen bonds.<ref name="hdprimer">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bates GP, Dorsey R, Gusella JF, Hayden MR, Kay C, Leavitt BR, Nance M, Ross CA, Scahill RI, Wetzel R, Wild EJ, Tabrizi SJ | title = Huntington disease | journal = Nature Reviews. Disease Primers | volume = 1 | pages = 15005 | date = April 2015 | pmid = 27188817 | doi = 10.1038/nrdp.2015.5 | author-link12 = Sarah Tabrizi | s2cid = 25759303 }}</ref> These aggregates share the same fundamental cross-beta ] architecture seen in other ] .<ref name="fibrilstruc">{{cite journal | vauthors = Matlahov I, van der Wel PC | title = Conformational studies of pathogenic expanded polyglutamine protein deposits from Huntington's disease | journal = Experimental Biology and Medicine | volume = 244 | issue = 17 | pages = 1584–1595 | date = December 2019 | pmid = 31203656 | pmc = 6920524 | doi = 10.1177/1535370219856620 | s2cid = 189944779 }}</ref> Over time, the aggregates accumulate to form ] within cells, ultimately interfering with neuronal function.<ref name="hdprimer"/><ref name="pmid14585171"/> Inclusion bodies have been found in both the ] and ].<ref name="pmid14585171"/> Inclusion bodies in cells of the brain are one of the earliest pathological changes, and some experiments have found that they can be ] for the cell, but other experiments have shown that they may form as part of the body's defense mechanism and help protect cells.<ref name="pmid14585171"/> | |||

| ===Pathophysiology=== | |||

| Degeneration of ]al cells, especially in the ]s and ] (the ]) of the ] occurs. There is also ] and loss of medium spiny neurons. | |||

| Several pathways by which mHtt may cause cell death have been identified. These include effects on ], which help fold proteins and remove misfolded ones; interactions with ]s, which play a role in the ]; the ]; impairment of energy production within cells; and effects on the expression of genes.<ref name="hdprimer"/><ref name="urlNature Clinical Practice Neurology | Mechanisms of Disease: histone modifications in Huntingtons disease | Article">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sadri-Vakili G, Cha JH | title = Mechanisms of disease: Histone modifications in Huntington's disease | journal = Nature Clinical Practice. Neurology | volume = 2 | issue = 6 | pages = 330–338 | date = June 2006 | pmid = 16932577 | doi = 10.1038/ncpneuro0199 | s2cid = 12474262 }}</ref> | |||

| The brain initiates motion by sending a signal down the spinal cord from the external ]. At the same time that the stimulus is being sent down the spinal cord, the ] of the ] excite the internal globus pallidus, which inhibits the ] and modulates motion. | |||

| Mutant huntingtin protein has been found to play a key role in ].<ref name="Liu">{{cite journal | vauthors = Liu Z, Zhou T, Ziegler AC, Dimitrion P, Zuo L | title = Oxidative Stress in Neurodegenerative Diseases: From Molecular Mechanisms to Clinical Applications | journal = Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity | volume = 2017 | pages = 2525967 | date = 2017 | pmid = 28785371 | pmc = 5529664 | doi = 10.1155/2017/2525967 | doi-access = free }}</ref> The impairment of ] can result in higher levels of ] and release of ].<ref name="pmid27662334">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kumar A, Ratan RR | title = Oxidative Stress and Huntington's Disease: The Good, The Bad, and The Ugly | journal = Journal of Huntington's Disease | volume = 5 | issue = 3 | pages = 217–237 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27662334 | pmc = 5310831 | doi = 10.3233/JHD-160205 }}</ref> | |||

| In Huntington's disease the external globus pallidus over-inhibits the flow of excitation from the subthalamic nuclei, which interferes with the initiation of motion. The | |||

| subthalamic nuclei also generate reduced excitation to the internal globus pallidus, resulting in a weak inhibitory signal to the thalamus. The thalamus in turn then sends a strong excitatory signal to the ] resulting in unmodulated motion. | |||

| Glutamine is known to be ] when present in large amounts, that can cause damage to numerous cellular structures. Excessive glutamine is not found in HD, but the interactions of the altered huntingtin protein with numerous proteins in neurons lead to an increased vulnerability to glutamine. The increased vulnerability is thought to result in excitotoxic effects from normal glutamine levels.<ref name="hdprimer"/> | |||

| == Diagnosis == | |||

| {{see|Genetic testing}} | |||

| To determine whether initial symptoms are evident, a physical and/or psychological examination is required. The uncontrollable movements are often the symptoms which cause initial alarm and lead to diagnosis; however, the disease may begin with cognitive or emotional symptoms, which are not always recognized. ] testing is possible by means of a ] which counts the number of repetitions in the gene. | |||

| ===Macroscopic changes=== | |||

| A negative blood test means that the individual does not carry the expanded copy of the gene, will never develop symptoms, and cannot pass it on to children. A positive blood test means that the individual does carry the expanded copy of the gene, will develop the disease, and has a 50% chance of passing it on to children. A pre-symptomatic positive blood test is not considered a diagnosis, because it may be decades before onset. | |||

| {{See also|Basal ganglia disease}} | |||

| ] made up of the ] and the ].]] | |||

| Initially, damage to the brain is regionally specific with the ] in the subcortical ] being primarily affected, followed later by ] involvement in all areas.<ref name="Nopoulos">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nopoulos PC | title = Huntington disease: a single-gene degenerative disorder of the striatum | journal = Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience | volume = 18 | issue = 1 | pages = 91–98 | date = March 2016 | pmid = 27069383 | pmc = 4826775 | doi = 10.31887/DCNS.2016.18.1/pnopoulos }}</ref><ref name="McColgan">{{cite journal | vauthors = McColgan P, Tabrizi SJ | title = Huntington's disease: a clinical review | journal = European Journal of Neurology | volume = 25 | issue = 1 | pages = 24–34 | date = January 2018 | pmid = 28817209 | doi = 10.1111/ene.13413 | doi-access = free }}</ref> Other areas of the ] affected include the ]; cortical involvement includes ]; also evident is involvement of the ], ]s in the ], lateral tuberal nuclei of the ] and parts of the ].<ref name="lancet07" /> These areas are affected according to their structure and the types of neurons they contain, reducing in size as they lose cells.<ref name="lancet07" /> Striatal ]s are the most vulnerable, particularly ones with ] towards the ], with ]s and spiny cells projecting to the ] being less affected.<ref name="lancet07" /><ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Purves D, Augustine GA, Fitzpatrick D, Hall W, LaMantia AS, McNamara JO, Williams SM | veditors = Purves D | title = Neuroscience | url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?call=bv.View..ShowTOC&rid=neurosci.TOC&depth=2 | edition = 2nd | publisher = Sinauer Associates | location = Sunderland, MA | isbn = 978-0-87893-742-4 | chapter = Modulation of Movement by the Basal Ganglia – Circuits within the Basal Ganglia System | chapter-url = https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?highlight=Huntington's%20disease&rid=neurosci.section.1251 | access-date = 1 April 2009 | year = 2001 | url-status=live | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090218192801/http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/bv.fcgi?call=bv.View..ShowTOC&rid=neurosci.TOC&depth=2 | archive-date = 18 February 2009}}</ref> HD also causes an ] in ]s and activation of the brain's immune cells, ].<ref name="pmid17965655">{{cite journal | vauthors = Lobsiger CS, Cleveland DW | title = Glial cells as intrinsic components of non-cell-autonomous neurodegenerative disease | journal = Nature Neuroscience | volume = 10 | issue = 11 | pages = 1355–1360 | date = November 2007 | pmid = 17965655 | pmc = 3110080 | doi = 10.1038/nn1988 }}</ref> | |||

| Because of the ramifications on the life of an at-risk individual, with no cure for the disease and no proven way of slowing it, several counseling sessions are usually required before the blood test. Unless a child shows significant symptoms or is sexually active or considered to be ], children under eighteen will not be tested. The members of the ] strongly encourage these restrictions in their testing protocol. A pre-symptomatic test is a life-changing event and a very personal decision. Embryonic screening is also possible, giving HD carriers or at-risk individuals the option of ensuring their children will not inherit the disease if abortion is acceptable to them. It is possible to test an embryo either in the womb (]) or to ensure a child will not have HD by utilising ] and testing before implantation. | |||

| The basal ganglia play a key role in movement and behavior control. Their functions are not fully understood, but theories propose that they are part of the cognitive ]<ref name="pmid16496032"/> and the motor circuit.<ref name="pmid10923984"/> The basal ganglia ordinarily inhibit a large number of circuits that generate specific movements. To initiate a particular movement, the cerebral cortex sends a signal to the basal ganglia that causes the inhibition to be released. Damage to the basal ganglia can cause the release or reinstatement of the inhibitions to be erratic and uncontrolled, which results in an awkward start to the motion or motions to be unintentionally initiated or in a motion to be halted before or beyond its intended completion. The accumulating damage to this area causes the characteristic erratic movements associated with HD known as chorea, a ].<ref name="pmid10923984">{{cite journal | vauthors = Crossman AR | title = Functional anatomy of movement disorders | journal = Journal of Anatomy | volume = 196 | issue = Pt 4 | pages = 519–525 | date = May 2000 | pmid = 10923984 | pmc = 1468094 | doi = 10.1046/j.1469-7580.2000.19640519.x }}</ref> Because of the basal ganglia's inability to inhibit movements, individuals affected by it inevitably experience a reduced ability to produce speech and swallow foods and liquids (dysphagia).<ref>{{Cite book|title = Motor Speech Disorders: Substrates, Differential Diagnosis, and Management | edition = 3rd | vauthors = Duffy J |publisher = Elsevier|year = 2013|location = St. Louis, Missouri|pages = 196–7}}</ref> | |||

| A full pathological diagnosis can only be established by a neurological examination's findings and/or demonstration of cell loss in the areas affected by HD, supported by a cranial ] or ] scan findings. | |||

| ===Transcriptional dysregulation=== | |||

| == Management == | |||

| There is no treatment to fully arrest the progression of the disease, but symptoms can be reduced or alleviated through the use of medication and care methods. Huntington mice models exposed to better ] techniques, especially better access to food and water, lived much longer than mice that were not well cared for.{{Fact|date=December 2007}} | |||

| ] (CBP), a transcriptional coregulator, is essential for cell function because as a coactivator at a significant number of promoters, it activates the transcription of genes for survival pathways.<ref name="urlNature Clinical Practice Neurology | Mechanisms of Disease: histone modifications in Huntingtons disease | Article"/> CBP contains an ] domain to which HTT binds through its polyglutamine-containing domain.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Steffan JS, Bodai L, Pallos J, Poelman M, McCampbell A, Apostol BL, Kazantsev A, Schmidt E, Zhu YZ, Greenwald M, Kurokawa R, Housman DE, Jackson GR, Marsh JL, Thompson LM | title = Histone deacetylase inhibitors arrest polyglutamine-dependent neurodegeneration in Drosophila | journal = Nature | volume = 413 | issue = 6857 | pages = 739–743 | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11607033 | doi = 10.1038/35099568 | s2cid = 4419980 | bibcode = 2001Natur.413..739S | url = https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5q52298v | access-date = 28 June 2019 | archive-date = 1 August 2020 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20200801220516/https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5q52298v | url-status = live }}</ref> Autopsied brains of those who had Huntington's disease also have been found to have incredibly reduced amounts of CBP.<ref name="urlAnalysis of Strand Slippage in DNA Polymerase Expansions of CAG/CTG Triplet Repeats Associated with Neurodegenerative Disease – JBC">{{cite journal | vauthors = Petruska J, Hartenstine MJ, Goodman MF | title = Analysis of strand slippage in DNA polymerase expansions of CAG/CTG triplet repeats associated with neurodegenerative disease | journal = The Journal of Biological Chemistry | volume = 273 | issue = 9 | pages = 5204–5210 | date = February 1998 | pmid = 9478975 | doi = 10.1074/jbc.273.9.5204 | doi-access = free }}</ref> In addition, when CBP is overexpressed, polyglutamine-induced death is diminished, further demonstrating that CBP plays an important role in Huntington's disease and neurons in general.<ref name="urlNature Clinical Practice Neurology | Mechanisms of Disease: histone modifications in Huntingtons disease | Article"/> | |||

| === Medication === | |||

| Other standard treatments to alleviate emotional symptoms include the use of ]s and sedatives, with ]s (in low doses) for psychotic symptoms. | |||

| == |

==Diagnosis== | ||

| ] helps by improving speech and swallowing methods; this therapy is more effective if started early on, as the ability to learn is reduced as the disease progresses. | |||

| ] of the onset of HD can be made following the appearance of physical symptoms specific to the disease.<ref name="lancet07" /> Genetic testing can be used to confirm a physical diagnosis if no family history of HD exists. Even before the onset of symptoms, genetic testing can confirm if an individual or ] carries an expanded copy of the trinucleotide repeat (CAG) in the ''HTT'' gene that causes the disease. ] is available to provide advice and guidance throughout the testing procedure and on the implications of a confirmed diagnosis. These implications include the impact on an individual's psychology, career, family-planning decisions, relatives, and relationships. Despite the availability of pre-symptomatic testing, only 5% of those at risk of inheriting HD choose to do so.<ref name="lancet07" /> | |||

| Intensive therapy: A pilot study on July, 2007, of inpatient rehabilitation for the Italian Welfare system, of speech, mind and body showed no motor decline in the two-year study. This is a significant find for Huntington's.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17702702 | |||

| |title=Effects of an intensive rehabilitation programme on patients with Huntington's disease: a pilot study. | |||

| |publisher= Clin Rehabil. 2007 Jul;21(7):603-13. | |||

| |author=Zinzi P, Salmaso D, De Grandis R, Graziani G, Maceroni S, Bentivoglio A, Zappata P, Frontali M, Jacopini G. | |||

| |date=2007-Jul-21 | |||

| |language=English }}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Clinical=== | ||

| Nutrition is an important part of treatment; most third and fourth stage HD sufferers need two to three times the ] of the average person to maintain body weight.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.hdsa.org/site/PageServer?pagename=family_guide_nutrition | |||

| |title=Family Guide Series - Nutrition and Huntington's Disease | |||

| |publisher=Huntington's Disease Society of America Publications | |||

| |author=Gaba, Anna | |||

| |date= | |||

| |language=English | |||

| |accessdate=2008-04-02 | |||

| }}</ref> However, the additional calories should be from a healthy source, not saturated fats and unhealthy foods, so a ]'s consultation is often helpful. Healthier foods in pre-symptomatic and earlier stages may slow down the onset and progression of the disease. High calorie intake in pre-symptomatic and earlier stages has been shown to speed up the onset and reduce IQ level. | |||

| ] section from an ] ] of a patient with HD, showing ] of the heads of the ], enlargement of the frontal horns of the ] (hydrocephalus ''ex vacuo''), and generalized cortical atrophy<ref>{{cite web |vauthors=Gaillard F |title=Huntington's disease |url=http://www.radpod.org/2007/05/01/huntingtons-disease/ |date=1 May 2007 |work=Radiology picture of the day |publisher=www.radpod.org |access-date=24 July 2009 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071022134552/http://radpod.org/2007/05/01/huntingtons-disease/ |archive-date=22 October 2007}}</ref>]] | |||

| ] can be added to drinks as swallowing becomes more difficult, as thicker fluids are easier and safer to swallow. The option of using a ] is available when eating becomes too hazardous or uncomfortable, this greatly reduces the chances of ] of food, and the subsequent increased risk of pneumonia, and increases the amount of nutrients and calories that can be ingested. | |||

| A ], sometimes combined with a ], can determine whether the onset of the disease has begun.<ref name="lancet07" /> Excessive unintentional movements of any part of the body are often the reason for seeking medical consultation. If these are abrupt and have random timing and distribution, they suggest a diagnosis of HD. Cognitive or behavioral symptoms are rarely the first symptoms diagnosed; they are usually only recognized in hindsight or when they develop further. How far the disease has progressed can be measured using the unified Huntington's disease rating scale, which provides an overall rating system based on motor, behavioral, cognitive, and functional assessments.<ref name="pmid19111470">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rao AK, Muratori L, Louis ED, Moskowitz CB, Marder KS | title = Clinical measurement of mobility and balance impairments in Huntington's disease: validity and responsiveness | journal = Gait & Posture | volume = 29 | issue = 3 | pages = 433–436 | date = April 2009 | pmid = 19111470 | doi = 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.11.002 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://huntingtonstudygroup.org/tools-resources/uhdrs/ |title=Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale (UHDRS) |access-date=14 April 2009 |work=UHDRS and Database |publisher=HSG |date=1 February 2009 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150811064639/http://huntingtonstudygroup.org/tools-resources/uhdrs/ |archive-date=11 August 2015}}</ref> ], such as a ] or ], can show atrophy of the caudate nuclei early in the disease, as seen in the illustration to the right, but these changes are not, by themselves, diagnostic of HD. ] can be seen in the advanced stages of the disease. ] techniques, such as ] (fMRI) and ] (PET), can show changes in brain activity before the onset of physical symptoms, but they are experimental tools and are not used clinically.<ref name="lancet07" /> | |||

| ], an Omega-3 fatty acid, may slow and possibly reverse the progression of the disease.<ref></ref> It is currently in FDA clinical trial as ethyl-EPA, (brand name Miraxion), for prescription use. Clinical trials utilise 2 grams per day of EPA. In the United States, it is available over the counter in lower concentrations in Omega-3 and fish oil supplements. Results of the first Phase III trial showed an improvement in motor function scores over the control group, but the small sample size render the result inconclusive. A larger trial is near completion and will be more statistically robust when results are posted. | |||

| ===Predictive genetic testing=== | |||

| == Prognosis == | |||

| Development of Huntington’s disease is highly ] repeat length-dependent. In the normal population, the CAG repeat is of between 7 and 35 repeats. Individuals carrying more than approximately 40 repeats will, however, go on to develop the disease at some point within their lifetime.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Andrew SE, Goldberg YP, Kremer B, ''et al'' |title=The relationship between trinucleotide (CAG) repeat length and clinical features of Huntington's disease |journal=Nat. Genet. |volume=4 |issue=4 |pages=398–403 |year=1993 |pmid=8401589 |doi=10.1038/ng0893-398}}</ref> The age of onset (and to a degree the severity of the disease) and hence the age at death, are inversely correlated with the length of the expanded CAG repeat, such that those with longer repeats develop the disease earlier. Individuals with greater than approximately 60 CAG repeats often develop juvenile Huntington's disease.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Harper PS |title=Huntington's disease: a clinical, genetic and molecular model for polyglutamine repeat disorders |journal=Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond., B, Biol. Sci. |volume=354 |issue=1386 |pages=957–61 |year=1999 |pmid=10434293 |doi=10.1098/rstb.1999.0446}}</ref> There is a large variation in age of onset for any given CAG repeat length within the intermediate range (40-50 CAGs). For example, a repeat length of 40 CAGs leads to an onset ranging from 40 to 70 years of age in the North American and Canadian population. This variation means that, although ]ic ]s have been proposed for predicting the age of onset,<ref>{{cite journal |author=Rubinsztein DC, Leggo J, Chiano M, ''et al'' |title=Genotypes at the GluR6 kainate receptor locus are associated with variation in the age of onset of Huntington disease |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=94 |issue=8 |pages=3872–6 |year=1997 |pmid=9108071 |doi= | doi = 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3872 <!--Retrieved from CrossRef by DOI bot-->}}</ref><ref name="pmid2973230">{{cite journal |author=Adams P, Falek A, Arnold J |title=Huntington disease in Georgia: age at onset |journal=Am. J. Hum. Genet. |volume=43 |issue=5 |pages=695–704 |year=1988 |pmid=2973230 |doi=}}</ref> in reality predicting the precise age at which clinical signs will manifest is not practical. | |||

| Because HD follows an autosomal dominant pattern of inheritance, a strong motivation exists for individuals who are at risk of inheriting it to seek a diagnosis. The genetic test for HD consists of a blood test, which counts the numbers of CAG repeats in each of the ''HTT'' alleles.<ref name="pmid15717026">{{cite journal | vauthors = Myers RH | title = Huntington's disease genetics | journal = NeuroRx | volume = 1 | issue = 2 | pages = 255–262 | date = April 2004 | pmid = 15717026 | pmc = 534940 | doi = 10.1602/neurorx.1.2.255 }}</ref> ] are given as follows: | |||

| Juvenile HD has been defined as having an onset younger than 20 years of age. The symptoms of juvenile HD are different from those of adult-onset HD in that they generally progress faster and are more likely to exhibit rigidity and ] instead of chorea and often include ]s.<ref name="Huntington1">Kremer B. Clinical neurology of Huntington's disease. In: Huntington's Disease (Third ed.), edited by Bates GP, Harper PS and Jones L. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002, p. 28-61.</ref> | |||

| * At 40 or more CAG repeats, full ] allele (FPA) exists.<ref name=Die-Smulders2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = de Die-Smulders CE, de Wert GM, Liebaers I, Tibben A, Evers-Kiebooms G | title = Reproductive options for prospective parents in families with Huntington's disease: clinical, psychological and ethical reflections | journal = Human Reproduction Update | volume = 19 | issue = 3 | pages = 304–315 | date = May 2013 | pmid = 23377865 | doi = 10.1093/humupd/dms058 | doi-access = free }} {{cite journal | vauthors = de Die-Smulders CE, de Wert GM, Liebaers I, Tibben A, Evers-Kiebooms G | title = Reproductive options for prospective parents in families with Huntington's disease: clinical, psychological and ethical reflections | journal = Human Reproduction Update | volume = 19 | issue = 3 | pages = 304–315 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23377865 | doi = 10.1093/humupd/dms058 | doi-access = free }}</ref> A "]" or "positive result" generally refers to this case. A positive result is not considered a diagnosis, since it may be obtained decades before the symptoms begin. However, a negative test means that the individual does not carry the expanded copy of the gene and will not develop HD.<ref name="lancet07" /> The test will tell a person who originally had a 50% chance of inheriting the disease if their risk goes up to 100% or is eliminated. Persons who test positive for the disease will develop HD sometime within their lifetimes, provided they live long enough for the disease to appear.<ref name="lancet07" /> | |||

| * At 36 to 39 repeats, incomplete or reduced penetrance allele (RPA) may cause symptoms, usually later in the adult life.<ref name=Die-Smulders2013/> The maximum risk is 60% that a person with an RPA will be symptomatic at age 65, and 70% at 75.<ref name=Die-Smulders2013/> | |||

| * At 27 to 35 repeats, intermediate allele (IA), or large normal allele, is not associated with symptomatic disease in the tested individual, but may expand upon further inheritance to give symptoms in offspring.<ref name=Die-Smulders2013/> | |||

| * With 26 or fewer repeats, the result is not associated with HD.<ref name=Die-Smulders2013/> | |||