| Revision as of 08:12, 28 May 2008 view sourcePetergkeyes (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users764 edits This is a major advocacy group, and the website is packed with meticulously researched and referenced data - often straight from the horse's mouth.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:32, 4 January 2025 view source KMaster888 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,260 edits ce | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Debate over the anti-tooth-decay measure}} | |||

| {{Wikify|date=April 2008}} | |||

| {{ |

{{pp-sock|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2020}} | |||

| '''Water fluoridation opposition''' refers to activism against the ] to public water supplies. | |||

| {{Alternative medicine sidebar|conspiracy}} | |||

| Opposition to ] arises from political, ethical, economic, and health considerations. For deprived groups, international and national agencies and dental associations across the world support the safety and effectiveness of water fluoridation.<ref name=Pizzo /> Proponents see it as a question of public health policy and equate the issue to ] and ], citing significant benefits to dental health and minimal risks.<ref name=ethics> | |||

| Opposition to water fluoridation arises from concern over the lack of quality research demonstrating its efficacy and safety<ref>Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/fluorid.htm Fluoridation of Drinking Water: a Systematic Review of its Efficacy and Safety. Accessed 2007-06-23</ref>, evidence that it may cause serious health problems, and a general resistance to the idea of compulsory 'mass medication' which takes away an individual's right to choose. | |||

| * {{cite journal | vauthors = McNally M, Downie J | title = The ethics of water fluoridation | journal = Journal | volume = 66 | issue = 11 | pages = 592–593 | date = December 2000 | pmid = 11253350 | url = http://cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-66/issue-11/592.html }} | |||

| </br>Most major medical and dental research associations maintain that water fluoridation is a safe and effective way to prevent ] and improve oral health.<ref name="whostatement" /><ref name="CDC"> website, page accessed March 3, 2006.</ref><ref name="NIDCR"> website, "The Story of Fluoride", page accessed March 3, 2006.</ref><ref name="iadrstatement"> policy statements, including water fluoridation, page accessed March 3, 2006.</ref> | |||

| * {{cite journal | vauthors = Cohen H, Locker D | title = The science and ethics of water fluoridation | journal = Journal | volume = 67 | issue = 10 | pages = 578–580 | date = November 2001 | pmid = 11737979 | url = http://cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-67/issue-10/578.html }}</ref><ref>Perrella, Andrea ML, and Simon J. Kiss. "Risk perception, psychological heuristics and the water fluoridation controversy." Canadian journal of public health 106.4 (2015): e197-e203.</ref> In contrast, opponents view it as an infringement of individual rights, if not an outright violation of medical ethics,<ref name="Cross2003">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cross DW, Carton RJ | title = Fluoridation: a violation of medical ethics and human rights | journal = International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health | volume = 9 | issue = 1 | pages = 24–29 | date = 1 March 2003 | pmid = 12749628 | doi = 10.1179/107735203800328830 | s2cid = 24127394 }}</ref> on the basis that individuals have no choice in the water that they drink, unless they drink more expensive bottled water.<ref name="Coggon">{{cite journal | vauthors = Coggon D, Cooper C | title = Fluoridation of water supplies. Debate on the ethics must be informed by sound science | journal = BMJ | volume = 319 | issue = 7205 | pages = 269–270 | date = July 1999 | pmid = 10426716 | pmc = 1126914 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.319.7205.269 }}</ref> A small minority of scientists have challenged the medical consensus, variously claiming that water fluoridation has no or little ] benefits, may cause serious health problems, is not effective enough to justify the costs, and is ] obsolete.<ref name="FRWG" /><ref name="Thiessen">{{cite journal | vauthors = Ko L, Thiessen KM | title = A critique of recent economic evaluations of community water fluoridation | journal = International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health | volume = 21 | issue = 2 | pages = 91–120 | date = 3 December 2014 | pmid = 25471729 | pmc = 4457131 | doi = 10.1179/2049396714Y.0000000093 }}</ref><ref name="Hileman">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hileman B | date = 4 November 2006 | url = http://pubs.acs.org/email/cen/html/090506090615.html | title = Fluoride Risks Are Still A Challenge | volume = 84 | issue = 36 | pages = 34–37 | journal = ] | doi = 10.1021/cen-v084n036.p034 | access-date = 14 April 2016 }}</ref><ref name="Kaminsky">{{cite journal | vauthors = Krimsky S | author-link = Sheldon Krimsky | title = Book review: Is Fluoride Really All That Safe? | date = 16 August 2004 | url = http://pubs.acs.org/cen/books/8233/8233books.html | volume = 82 | issue = 33 | pages = 35–36 | journal = ] | doi = 10.1021/cen-v082n033.p035 | access-date = 19 April 2016 }}</ref> | |||

| Opposition to fluoridation has existed since its initiation in the 1940s.<ref name="Martin1989" /> During the 1950s and 1960s, ] baselessly claimed that fluoridation was a ] plot to undermine American public health.<ref name="Johnston">{{cite book | vauthors = Johnston RD | title = The Politics of Healing | url = https://archive.org/details/politicshealingh00john | url-access = limited | publisher = Routledge | year = 2004 | isbn = 978-0-415-93339-1| page = }}</ref> In recent years, water fluoridation has become a prevalent health and political issue in many countries, resulting in some countries and communities discontinuing its use while it has expanded in others.<ref name="Scher2011">{{cite web|title=Introduction to the SCHER opinion on Fluoridation|url=http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/opinions_layman/fluoridation/en/l-3/1.htm#0|publisher=European Commission Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks (SCHER)|access-date=18 April 2016|date=2011}}</ref><ref name="Tiemann2013" /> The controversy is propelled by a significant public opposition supported by a minority of professionals,<ref name="ReferenceA">{{cite journal | vauthors = Martin B | title = Analyzing the fluoridation controversy: resources and structures | journal = Social Studies of Science | volume = 18 | issue = 2 | pages = 331–363 | date = May 1988 | pmid = 11621556 | doi = 10.1177/030631288018002006 | s2cid = 31073263 }}</ref> which include researchers, dental and medical professionals, alternative medical practitioners, health food enthusiasts, a few religious groups (mostly ] in the U.S.), and occasionally consumer groups and environmentalists.<ref name="Reilly">{{cite book | vauthors = Reilly GA |chapter=The task is a political one: the promotion of fluoridation |pages=323–342 |title=Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America | veditors = Ward JW, Warren C |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0-19-515069-8 }}</ref> Organized political opposition has come from ],<ref name="Dehnbase">{{cite web |url=http://www.dehnbase.org/lpus/library/platform/cp.html|title=Consumer protection |publisher=Libertarian Party |access-date= 28 June 2010}}</ref> the ],<ref name="Freeze_2009">{{cite book | vauthors = Freeze RA, Lehr JH |title=The fluoride wars: how a modest public health measure became America's longest-running political melodrama |location=Hoboken |publisher=Wiley |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-470-44833-5 }}</ref> the ],<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal |last=McNeil |first=Donald R. |date=1985 |title=America's Longest War: The Fight over Fluoridation, 1950– |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40256913 |journal=] |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=140–153 |jstor=40256913 |pmid=11624732 |issn=0363-3276}}</ref> ], and ].<ref name="Greenwars">{{cite news |vauthors=Nordlinger J |title=Water fights: believe it or not, the fluoridation war still rages – with a twist you may like |work=Natl Rev |date=2003-06-30 |url=http://www.thefreelibrary.com/Water+Fights%3a+Believe+it+or+not%2c+the+fluoridation+war+still+rages+--...-a0103135852 }}{{Dead link|date=August 2023 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> | |||

| A review conducted by the ] conclusion that the "evidence about reducing inequalities in dental health (using water fluoridation) was of poor quality, contradictory and unreliable" and noted that overall the studies they reviewed did support a decrease in dental decay from fluoridated water<ref>Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/fluorid.htm Fluoridation of Drinking Water: a Systematic Review of its Efficacy and Safety. Accessed 2007-06-23</ref> | |||

| Proponents of fluoridation have been criticized for overstating the benefits, while opponents have been criticized for understating them and for overstating the risks.<ref name="ChengChalmers2007">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cheng KK, Chalmers I, Sheldon TA | title = Adding fluoride to water supplies | journal = BMJ | volume = 335 | issue = 7622 | pages = 699–702 | date = October 2007 | pmid = 17916854 | pmc = 2001050 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.39318.562951.BE }}</ref><ref name=yorkcrd /> ]s have cited the lack of high quality research for the benefits and risks of water fluoridation and questions that are still unsettled.<ref name=Scher2011 /><ref name=yorkcrd>{{cite web | work = Centre for Reviews and Dissemination | url = https://www.york.ac.uk/media/crd/Fluoridation%20Statement.pdf | title = What the 'York Review' on the fluoridation of drinking water really found | publisher = ] | location = York, United Kingdom | date = 28 October 2003 | access-date = 12 April 2016 }}</ref><ref name=Ih2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Iheozor-Ejiofor Z, Worthington HV, Walsh T, O'Malley L, Clarkson JE, Macey R, Alam R, Tugwell P, Welch V, Glenny AM | display-authors = 6 | title = Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries | journal = The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews | volume = 6 | issue = 6 | pages = CD010856 | date = June 2015 | pmid = 26092033 | pmc = 6953324 | doi = 10.1002/14651858.CD010856.pub2 }}</ref>{{Update inline|reason=Updated version https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/39362658|date = October 2024}} Researchers who oppose the practice state this as well.<ref name="Book Reviews 2011">{{cite journal| vauthors = Peckham S |title=Book Reviews: The case against fluoride: how hazardous waste ended up in our drinking water and the bad science and powerful politics that keep it there, by Paul Connett, James Beck, and H Spedding Micklem|journal=Critical Public Health|volume=22|issue=1|date=2012|pages=113–114|issn=0958-1596|doi=10.1080/09581596.2011.593350|s2cid=144744675}}</ref> According to a 2013 ] report on fluoride in drinking water, these gaps in the fluoridation scientific literature fuel the controversy.<ref name=Tiemann2013 /> | |||

| ==Efficacy of water fluoridation== | |||

| </br>A recent review of the evidence from the ], published in 2000, examined 30 studies.<ref> York Review, Executive Summary http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/summary.pdf</ref> The researchers concluded that the quality of evidence in most studies was poor, also expressing concern over the "continuing misinterpretations of the evidence." Of the studies examined, there were mixed conclusions on the effectiveness of water fluoridation - the majority found some improvement, some showed no difference, some actually showed an increase in decay. The study did find an increase in cosmetic fluorosis, but no evidence of any link between fluoride and ], ], or bone fractures. It reserved caution however. A BBC story reviewing the review article, suggested that because of the poor evidence it said no firm conclusions should be drawn, and more evidence is needed.<ref>, from the ]. Published ] ]; accessed Feb 5, 2008.</ref> | |||

| </br> | |||

| Public water fluoridation was first practiced in 1945, in the U.S. As of 2015, about 25 countries have supplemental water fluoridation to varying degrees, and 11 of them have more than 50% of their population drinking fluoridated water. A further 28 countries have water that is naturally fluoridated, though in many of them there are areas where fluoride is above the optimum level.<ref name=extent2012>{{cite book |chapter=The extent of water fluoridation |chapter-url=https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/014a47_0776b576cf1c49308666cef7caae934e.pdf |url=http://bfsweb.org/one-in-a-million |title=One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation |edition=3rd |year=2012 |author1 = The British Fluoridation Society | author2 = The UK Public Health Association | author3 = The British Dental Association | author4 = The Faculty of Public Health |isbn=978-0-9547684-0-9 |pages=55–80 |publisher=British Fluoridation Society |location=Manchester }}</ref> As of 2012, about 435 million people worldwide received water fluoridated at the recommended level, of whom 57 million (13%) received naturally fluoridated water and 377 million (87%) received artificially fluoridated water.<ref name=extent2012 /><!-- Page 56 --> In 2014, three-quarters of the US population on the public water supply received fluoridated water, which represented two-thirds of the total US population.<ref name=US-CDC-WF-Stats-2014>{{cite web |url=https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/2014stats.htm |title=Community Water Fluoridation --- 2014 Water Fluoridation Statistics |work=cdc.gov |access-date=19 April 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| == Medical consensus == | |||

| Those that question the effectiveness of water fluoridation point out that dental decay continues to exist in water fluoridated communities. They reason that if fluoride is effective, then there would be no more tooth decay, and suggest that the continued prevalence of tooth decay among low-income groups demonstrates the ineffectiveness of fluoridation. | |||

| National and international health agencies and dental associations throughout the world have endorsed water fluoridation as safe and effective.<ref name=Pizzo>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pizzo G, Piscopo MR, Pizzo I, Giuliana G | title = Community water fluoridation and caries prevention: a critical review | journal = Clinical Oral Investigations | volume = 11 | issue = 3 | pages = 189–193 | date = September 2007 | pmid = 17333303 | doi = 10.1007/s00784-007-0111-6 | s2cid = 13189520 }}</ref><ref name=ADAorgs>{{cite web |url=http://www.ada.org/en/public-programs/advocating-for-the-public/fluoride-and-fluoridation/fluoridation-facts/fluoridation-facts-compendium|publisher=American Dental Association |title=National and International Organizations That Recognize the Public Health Benefits of Community Water Fluoridation for Preventing Dental Decay |access-date=2016-04-19 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080607092909/http://ada.org/public/topics/fluoride/facts/compendium.asp |archive-date=2008-06-07 }}</ref> The views on the most effective method for community prevention of tooth decay are mixed. The Australian government states that water fluoridation is the most effective means of achieving fluoride exposure that is community-wide.<ref name="NHMRC" /> The World Health Organization states water fluoridation, when feasible and culturally acceptable, has substantial advantages, especially for subgroups at high risk,<ref name="Petersen-2004">{{cite journal | vauthors = Petersen PE, Lennon MA | title = Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in the 21st century: the WHO approach | journal = Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology | volume = 32 | issue = 5 | pages = 319–321 | date = October 2004 | pmid = 15341615 | doi = 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2004.00175.x }}</ref> while the ] finds no advantage to water fluoridation compared with topical use.<ref name="EU2011" /> | |||

| One study by the National Institute of Dental Research showed little difference in tooth decay rates among children in fluoridated and non-fluoridated communities. In the study's results, the difference between the children exposed to water fluoridation, and those who were not exposed, was very small, between 0.12 and 0.30 DMFS (Decayed Missing and Filled Surfaces). <ref></ref> | |||

| Opponents conclude that, in light of the continuing dental health problem, water fluoridation is unable to successfully increase health standards and thus should not be used.<ref>, website, accessed 22 February, 2006.</ref> | |||

| ] supports water fluoridation as safe and effective.<ref name=extent2012 /> the European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry,<ref>{{cite journal | author = European Academy of Paediatric Dentistry | title = Guidelines on the use of fluoride in children: an EAPD policy document | journal = European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry | volume = 10 | issue = 3 | pages = 129–135 | date = September 2009 | pmid = 19772841 | doi = 10.1007/bf03262673 | s2cid = 3567956 }}</ref> and the national dental associations of Australia,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ada.org.au/News-Media/Issues-at-a-Glance/Fluoride |access-date=2016-04-19 |title=Issues at a Glance Fluoride |author=] |archive-date=22 April 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170422041132/http://www.ada.org.au/News-Media/Issues-at-a-Glance/Fluoride |url-status=dead }}</ref> Canada,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cda-adc.ca/_files/position_statements/fluoride.pdf|access-date=2016-04-19|date=March 2003| quote = update March 2012 |title=CDA position on use of fluorides in caries prevention |author=] }}</ref> and the U.S.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://ada.org/public/topics/fluoride/facts/fluoridation_facts.pdf|access-date=2008-12-22 |date=2005 |author=ADA Council on Access, Prevention and Interprofessional Relations |publisher=] |title=Fluoridation facts |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080723125738/http://ada.org/public/topics/fluoride/facts/fluoridation_facts.pdf |archive-date=2008-07-23 }}</ref> The American Dental Association calls water fluoridation "one of the safest and most beneficial, cost-effective public health measures for preventing, controlling, and in some cases reversing, tooth decay."<ref>{{cite web | publisher = American Dental Association | url = https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/press-kits/water-fluoridation-press-kit | title = Water Fluoridation Press Kit | date = 2005 | access-date = 26 June 2021 | archive-date = 26 June 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210626092740/https://www.ada.org/en/press-room/press-kits/water-fluoridation-press-kit | url-status = dead }}</ref> | |||

| Water fluoridation opponents also argue that the decline of tooth decay over the last thirty years may be the result of factors other than fluoride, including improved oral hygiene, diet, and overall health.<ref>, website, Hardy Limeback, accessed 22 February, 2006.</ref> | |||

| In the English speaking nations—the United States, Canada, UK, Australia and New Zealand, all of which practice water fluoridation—many medical associations and authorities have published position statements and endorsed water fluoridation. The ],<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Murthy VH, ((c)) | doi = 10.1177/003335491513000402 | title = Surgeon General's Perspectives: Community Water Fluoridation – One of CDC's "10 Great Public Health Achievements of the 20th Century" | journal = Public Health Reports | date = July–August 2015 | volume = 130 | issue = 4 | pages = 296–298 | pmid = 26346894 | pmc = 4547574 }}</ref> the ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://apha.org/news-and-media/news-releases/apha-news-releases/apha-reaffirms-its-support-for-community-water-fluoridation |access-date=2016-04-19 |date=2011 |title=APHA Reaffirms Its Support for Community Water Fluoridation |author=American Public Health Association }}</ref> the ],<ref>{{cite book|title=Royal Commission on the NHS Chapter 9|year= 1979|publisher=HMSO|isbn=978-0101761505|url=http://www.sochealth.co.uk/national-health-service/royal-commission-on-the-national-health-service-contents/royal-commission-on-the-nhs-chapter-9/|access-date=19 May 2015}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|author=Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing|title=Fluoridation of drinking water|url=http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/dentalfluoridation|website=www.health.gov.au|access-date=22 April 2016|language=en}}</ref> ],<ref>{{cite web|title=Questions and answers | Fluoride facts|url=http://www.fluoridefacts.govt.nz/questions-and-answers-0|website=www.fluoridefacts.govt.nz|access-date=22 April 2016}}</ref> and ] support fluoridation, citing a number of international scientific reviews that indicate "there is no link between any adverse health effects and exposure to fluoride in drinking water at levels that are below the maximum acceptable concentration of 1.5 mg/L."<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewh-semt/water-eau/drink-potab/health-sante/faq_fluoride-fluorure-eng.php |title=Fluoride in Drinking Water |publisher=]|date=2017-01-23 }}</ref> The ] listed water fluoridation as one of the ten great public health achievements of the 20th century in the U.S.,<ref name="CDC-1999">{{cite journal |author=Division of Oral Health, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, CDC |title=Achievements in public health, 1900–1999: Fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries |journal = Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) |volume=48 |issue=41 |pages=933–940 |date=1999 |url=http://cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm4841a1.htm }} Contains in: {{cite journal | vauthors = <!-- pacify citation bot --> | title = From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Achievements in public health, 1900-1999: fluoridation of drinking water to prevent dental caries | journal = JAMA | volume = 283 | issue = 10 | pages = 1283–1286 | date = March 2000 | pmid = 10714718 | doi = 10.1001/jama.283.10.1283 | doi-access = free }}</ref> along with ], ], recognition of the ], and other achievements.<ref name="CDC-1999" /> | |||

| Since oral health is affected by many factors, fluoride alone would be unable, nor would it be expected, to eradicate the ]. The ]s that would be more likely to benefit from water fluoridation are those living in poorer conditions, and an important factor to decrease dental ] may be water fluoridation programs.<ref name="whostatement"> website, "World Water Day 2001: Oral health", page 3, page accessed March 3, 2006.</ref> Nonetheless, it is understood that these communities suffer from various problems which would impede oral health, such as lack of access to dental care and poorer ] ]. | |||

| In ], the Israeli Association of Public Health Physicians, the Israel Pediatric Association, and the Israel Dental Association, support fluoridation.<ref>{{cite web|title=Restoration of Fluoridation to Drinking Water, Ministry of Health|url=http://www.health.gov.il/English/Topics/Dental_Health/information/Pages/flouride-2015.aspx|website=www.health.gov.il|access-date=23 April 2016}}</ref> The ], looking at global public health, identifies fluoride as one of a few chemicals for which the contribution from drinking-water to overall intake is an important factor in preventing disease. This is because there is clear evidence that optimal concentrations of fluoride provide protection against cavities, both in children and in adults.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/oralhealth/en/index2.html |title=Water fluoridation |work=World Water Day 2001: Oral health |publisher=] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110514030918/http://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/oralhealth/en/index2.html |archive-date=14 May 2011|quote=There are few chemicals for which the contribution from drinking-water to overall intake is an important factor in preventing disease. One example is the effect of fluoride in drinking-water in protecting against dental caries.}}</ref><ref name="WHO2011">{{Cite book|url=http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44584/1/9789241548151_eng.pdf|title=Guidelines for Drinking-water Quality|edition=4th|publisher=]|year=2011|isbn=9789241548151|pages=168, 175, 372, 370–373}}</ref>{{sfn|Fawell et al.|2006|p=32|ps=.{{sp}}"Concentrations in drinking-water of about 1 mg l–1 are associated with a lower incidence of dental caries, particularly in children, whereas excess intake of fluoride can result in dental fluorosis. In severe cases this can result in erosion of enamel. The margin between the beneficial effects of fluoride and the occurrence of dental fluorosis is small and public health programmes seek to retain a suitable balance between the two."}} | |||

| Some research shows the effects of fluoridation to be merely topical,<ref>, website, accessed 18 February, 2006.</ref> indicating that fluoridating water is unnecessary and ineffective. | |||

| === Minority scientific view === | |||

| ==Safety== | |||

| The scientists or doctors who oppose water fluoridation argue that it has no or little cariostatic benefits, may cause serious health problems, is not effective enough to justify the costs, and is pharmacologically obsolete.<ref name=Thiessen /><ref name=Hileman /><ref name=Kaminsky /> | |||

| == Evidence == | |||

| The issue of ] ] has been brought into question by opponents. The ], a UK political party, even refer to fluoride as a poison.<ref>http://www.greenparty.org.uk/files/reports/2003/F%20illegality.htm Water fluoridation contravenes UK law, EU directives and the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine</ref> They say water fluoridation violates Article 35 of the ], and the UK poisons act of 1972 which bans fluorosilicates. Because it believes that fluoride is a poison they say it also violates Articles 3 and 8 of the Human Rights Act, and also Articles 3 and 8 of the Convention because governments are forbidden from harming its citizens. Where children are involved - indeed, specifically targeted - such an act also raise issues under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. | |||

| Proponents and opponents have been both criticized for overstating the benefits or risks, and understating the other, respectively.<ref name="ChengChalmers2007" /><ref name=yorkcrd /> Systematic reviews have cited the lack of high-quality research for the benefits and risks of water fluoridation and questions that are still unsettled.<ref name=Scher2011 /><ref name=yorkcrd /><ref name=Ih2015 /> A 2007 ] report concluded that good evidence for or against water fluoridation is lacking.<ref name=nuffield /> Researchers who oppose the practice state this as well.<ref name="Book Reviews 2011" /> According to a 2013 ] report on fluoride in drinking water, these gaps in the fluoridation scientific literature fuel the controversy.<ref name=Tiemann2013 /> John Doull, chairman of the 2006 ] committee report on fluoride in drinking water, has stated a similar conclusion regarding the source of the controversy: "In the scientific community, people tend to think this is settled. I mean, when the U.S. surgeon general comes out and says this is one of the 10 greatest achievements of the 20th century, that's a hard hurdle to get over. But when we looked at the studies that have been done, we found that many of these questions are unsettled and we have much less information than we should, considering how long this has been going on. I think that's why fluoridation is still being challenged so many years after it began. In the face of ignorance, controversy is rampant."<ref>{{cite journal| vauthors = Barnett-Rose R |title=Compulsory Water Fluoridation: Justifiable Public Health Benefit or Human Experimental Research Without Informed Consent?|journal=William & Mary Environmental Law and Policy Review|date=December 2014|volume= 39|issue= 1|page=225|url=http://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmelpr/vol39/iss1/7/|access-date=21 April 2016}}</ref><ref name=Fagin>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fagin D | title = Second thoughts about fluoride | journal = Scientific American | volume = 298 | issue = 1 | pages = 74–81 | date = January 2008 | pmid = 18225698 | doi = 10.1038/scientificamerican0108-74 | doi-broken-date = 1 November 2024 | bibcode = 2008SciAm.298a..74F }}</ref> | |||

| </br> | |||

| There are a lot of conflicting reports as to the safety of water fluoridation. This issue was covered in the University of York's review concluding that "The evidence about reducing inequalities in dental health was of poor quality, contradictory and unreliable."<ref> York Review, Executive Summary http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/pdf/summary.pdf</ref> Because of these conflicting reports and the numerous websites that point to these safety concerns, many question whether fluoridation should be legal until some of these issues are resolved. Some of the concerns raised include:</br> | |||

| === Safety === | |||

| *A weakening of bones, leading to an increase in hip and wrist fracture.<ref>{{cite journal | journal = ] | volume = 31 | issue = 2 | year = 1998 | pages = 103–118 | author = John Colquhoun | title = Why I changed my mind about water fluoridation | url = http://www.fluoride-journal.com/98-31-2/312103.htm | format = reprinted from '']''}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Water fluoridation#Safety}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| NOTE: The contents here are from the safety section in the "main" article. Please update when that section is changed. Do not add or delete content directly in this section. Edit the main article section first. If those changes are accepted, then that new version can be used here. | |||

| --> | |||

| ] can be present naturally in water at concentrations well above recommended levels, which can have ], including severe dental fluorosis, ], and weakened bones.{{sfn|Fawell et al.|2006|pp=29–36}} In 1984 the World Health Organization recommended a guideline maximum fluoride value of 1.5 mg/L as a level at which fluorosis should be minimal, reaffirming it in 2006.{{sfn|Fawell et al.|2006|pp=37–39}} | |||

| Fluoridation has little effect on risk of ] (broken bones); it may result in slightly lower fracture risk than either excessively high levels of fluoridation or no fluoridation.<ref name="NHMRC">{{cite book |url=http://nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/Eh41_Flouridation_PART_A.pdf|access-date=2009-10-13 |year=2007 |title=A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation |author=National Health and Medical Research Council (Australia) |isbn=978-1864964158 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20091014191758/http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/publications/synopses/Eh41_Flouridation_PART_A.pdf | archive-date=14 October 2009 }} Summary: {{cite journal | vauthors = Yeung CA | title = A systematic review of the efficacy and safety of fluoridation | journal = Evidence-Based Dentistry | volume = 9 | issue = 2 | pages = 39–43 | date = 2008 | pmid = 18584000 | doi = 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400578 | s2cid = 205675585 | url = http://nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/media/media/rel07/Fluoride_Flyer.pdf | doi-access = free }}</ref> There is no clear association between fluoridation and ] or deaths due to cancer, both for cancer in general and specifically for ] and ].<ref name="NHMRC" /><ref name="YorkReview2000">{{cite web | vauthors = McDonagh M, Whiting P, Bradley M, Cooper J, Sutton A, Chestnutt I, Misso K, Wilson P, Treasure E, Kleijnen J |title=A systematic review of public water fluoridation |url=http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/CRD_Reports/crdreport18.pdf|date=2000 }} Report website: {{cite web |title=Fluoridation of drinking water: a systematic review of its efficacy and safety |publisher=NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination |date=2000 |url=http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/fluorid.htm |access-date=2009-05-26 }} Authors' summary: {{cite journal | vauthors = McDonagh MS, Whiting PF, Wilson PM, Sutton AJ, Chestnutt I, Cooper J, Misso K, Bradley M, Treasure E, Kleijnen J | display-authors = 6 | title = Systematic review of water fluoridation | journal = BMJ | volume = 321 | issue = 7265 | pages = 855–859 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 11021861 | pmc = 27492 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.321.7265.855 }} Authors' commentary: {{cite journal | vauthors = Treasure ET, Chestnutt IG, Whiting P, McDonagh M, Wilson P, Kleijnen J | title = The York review – a systematic review of public water fluoridation: a commentary | journal = British Dental Journal | volume = 192 | issue = 9 | pages = 495–497 | date = May 2002 | pmid = 12047121 | doi = 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801410a | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| *A lowering of IQ.<ref>National Research Council. Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA's Standards (2006). Page accessed 23 February, 2007.</ref> | |||

| In rare cases improper implementation of water fluoridation can result in overfluoridation that causes outbreaks of acute ], with symptoms that include ], ], and ]. Three such outbreaks were reported in the U.S. between 1991 and 1998, caused by fluoride concentrations as high as 220 mg/L; in the 1992 Alaska outbreak, 262 people became ill and one person died.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Balbus JM, Lang ME | title = Is the water safe for my baby? | journal = Pediatric Clinics of North America | volume = 48 | issue = 5 | pages = 1129–1152, viii | date = October 2001 | pmid = 11579665 | doi = 10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70365-5 }}</ref> In 2010, approximately 60 gallons of fluoride were released into the water supply in ], in 90 minutes—an amount that was intended to be released in a 24-hour period.<ref>{{cite news |publisher= Fox 8 |title= Asheboro notifies residents of over-fluoridation of water |date= 2010-06-29 |url= http://www.myfox8.com/news/wghp-asheboro-fluoride-release-100629,0,2164002.story |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100704054308/http://www.myfox8.com/news/wghp-asheboro-fluoride-release-100629,0,2164002.story |archive-date= 4 July 2010}}</ref> | |||

| *Chromosomal damage and interference with ] repair.<ref>, website, accessed 18 February, 2006.</ref><ref>, from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref><ref name="nciosteosarcomas"> website, "Fluoridated Water: Questions and Answers", page accessed March 3, 2006.</ref> | |||

| *According to the ] fluoride is an equivocal ].<ref>http://emporium.turnpike.net/P/PDHA/fluoride/adverse.htm</ref> Available ] is conflicting, but ] (a rare bone cancer) has been shown to be associated with fluoride exposure, including fluoridated water, in humans and animals.<ref> http://www.slweb.org/bibliography.html#cancer</ref><ref>http://www.fluoridealert.org/health/cancer/</ref><ref>http://www.fluoridation.com/cancer.htm</ref> | |||

| *A study using rats that were fed for one year with 1 ppm fluoride in their water. They were shown to have detrimental changes to their kidneys and brains,<ref>, website, accessed 18 February, 2006.</ref> an increased uptake of aluminum in the brain, and the formation of ] deposits, a characteristic of ].<ref> website, accessed 18 February, 2006.</ref><ref>Varner, J.A., K.F. Jensen, W. Horvath, R.L. Isaacson., abstract from website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> However another study found no link<ref> (in pdf format), from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> Moreover, there is some research that suggests Alzheimer's disease can be prevented with water fluoridation because of the competition between ] and fluoride ].<ref>Kraus, A.S. and W.F. Forbes. , abstract from website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> Nonetheless, this research is also limited by design and no definitive conclusion of this effect can be made. Other studies claim that ] and ] are the most important risk factors concerning alzheimers..<ref>, by the website, a division of the National Institute of Aging, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> | |||

| Like other common water additives such as ], hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride decrease pH and cause a small increase of ], but this problem is easily addressed by increasing the pH.<ref name=Pollick /> Although it has been hypothesized that hydrofluosilicic acid and sodium silicofluoride might increase human ] uptake from water, a 2006 statistical analysis did not support concerns that these chemicals cause higher blood lead concentrations in children.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Macek MD, Matte TD, Sinks T, Malvitz DM | title = Blood lead concentrations in children and method of water fluoridation in the United States, 1988-1994 | journal = Environmental Health Perspectives | volume = 114 | issue = 1 | pages = 130–134 | date = January 2006 | pmid = 16393670 | pmc = 1332668 | doi = 10.1289/ehp.8319 | bibcode = 2006EnvHP.114..130M }}</ref> Trace levels of ] and lead may be present in fluoride compounds added to water; however, ]s are below measurement limits.<ref name=Pollick /> | |||

| *In animal studies, fluoride has been shown to inhibit melatonin production and promote precocious ].<ref></ref> Fluoride may have an analogous inhibitory effect on human melatonin production, as fluoride accumulates readily in the human pineal gland, the brain organ responsible for melatonin synthesis.<ref></ref> Further, fluoride can weaken the immune system, leaving people vulnerable to the development of ] and ].<ref>, website, accessed 19 February, 2006.</ref> | |||

| The effect of water fluoridation on the natural environment has been investigated, and no adverse effects have been established. Issues studied have included fluoride concentrations in groundwater and downstream rivers; lawns, gardens, and plants; consumption of plants grown in fluoridated water; air emissions; and equipment noise.<ref name=Pollick>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pollick HF | title = Water fluoridation and the environment: current perspective in the United States | journal = International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health | volume = 10 | issue = 3 | pages = 343–350 | date = 2004 | pmid = 15473093 | doi = 10.1179/oeh.2004.10.3.343 | s2cid = 8577186 }}</ref> | |||

| *A study showing that overdose of fluoride have been associated with ] damage, impaired ] function, and ] in children.<ref></ref> | |||

| === Efficacy === | |||

| *Animal studies demonstrate that fluoride can damage the male reproductive system in various species.<ref>, website, accessed 18 February, 2006.</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Water fluoridation#Effectiveness}} | |||

| <!-- | |||

| NOTE: The contents here are from the safety section in the "main" article. Please update when that section is changed. Do not add or delete content directly in this section. Edit the main article section first. If those changes are accepted, then that new version can be used here. | |||

| --> | |||

| Reviews have shown that water fluoridation reduces cavities in children.<ref name=Ih2015 /><ref name=EU2011>{{cite web|title=What role does fluoride play in preventing tooth decay?|url=http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/opinions_layman/fluoridation/en/l-3/5.htm#0|date=2011|access-date=18 April 2016}}</ref><ref name=Parnell>{{cite journal | vauthors = Parnell C, Whelton H, O'Mullane D | title = Water fluoridation | journal = European Archives of Paediatric Dentistry | volume = 10 | issue = 3 | pages = 141–148 | date = September 2009 | pmid = 19772843 | doi = 10.1007/bf03262675 | s2cid = 5442458 }}</ref> A conclusion for the efficacy in adults is less clear with some reviews finding benefit and others not.<ref name=Ih2015 /><ref name=Parnell /> Studies in the U.S. in the 1950s and 1960s showed that water fluoridation reduced childhood cavities by fifty to sixty percent, while studies in 1989 and 1990 showed lower reductions (40% and 18% respectively), likely due to increasing use of fluoride from other sources, notably toothpaste, and the "halo effect" of food and drink that is made in fluoridated areas and consumed in unfluoridated ones.<ref name="FRWG">{{cite journal|author=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|date=August 2001|title=Recommendations for using fluoride to prevent and control dental caries in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention|url=http://cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5014a1.htm|journal=MMWR. Recommendations and Reports|volume=50|issue=RR-14|pages=1–42|pmid=11521913<!-- |url=http://cdc.gov/fluoridation/guidelines/tooth_decay.htm -->}}</ref> | |||

| A 2000 UK ] (York) found that water fluoridation was ] with a decreased proportion of children with cavities of 15% and with a decrease in decayed, ], and ] ] (average decreases was 2.25 teeth). The review found that the evidence was of moderate quality: few studies attempted to reduce ], control for ]s, report variance measures, or use appropriate analysis. Although no major differences between natural and artificial fluoridation were apparent, the evidence was inadequate for a conclusion about any differences.<ref name=YorkReview2000 /> A 2002 systematic review found strong evidence that water fluoridation is effective at reducing overall tooth decay in communities.<ref name=Truman>{{cite journal | vauthors = Truman BI, Gooch BF, Sulemana I, Gift HC, Horowitz AM, Evans CA, Griffin SO, Carande-Kulis VG | display-authors = 6 | title = Reviews of evidence on interventions to prevent dental caries, oral and pharyngeal cancers, and sports-related craniofacial injuries | journal = American Journal of Preventive Medicine | volume = 23 | issue = 1 Suppl | pages = 21–54 | date = July 2002 | pmid = 12091093 | doi = 10.1016/S0749-3797(02)00449-X | url = https://zenodo.org/record/1260085 }}</ref> A 2015 Cochrane review also found benefit in children.<ref name=Ih2015 /> | |||

| ====Concentration of fluoride==== | |||

| Fluoride may also prevent cavities in adults of all ages. A 2007 ] by CDC researchers found that water fluoridation prevented an estimated 27% of cavities in adults, about the same fraction as prevented by exposure to any delivery method of fluoride (29% average).<ref name=Griffin>{{cite journal | vauthors = Griffin SO, Regnier E, Griffin PM, Huntley V | title = Effectiveness of fluoride in preventing caries in adults | journal = Journal of Dental Research | volume = 86 | issue = 5 | pages = 410–415 | date = May 2007 | pmid = 17452559 | doi = 10.1177/154405910708600504 | s2cid = 58958881 | hdl = 10945/60693 | hdl-access = free }} Summary: {{cite journal | vauthors = Yeung CA | title = Fluoride prevents caries among adults of all ages | journal = Evidence-Based Dentistry | volume = 8 | issue = 3 | pages = 72–73 | year = 2007 | pmid = 17891121 | doi = 10.1038/sj.ebd.6400506 | s2cid = 24509775 | doi-access = free }}</ref> A 2011 European Commission review concluded that water fluoridation has no known advantage over topical prevention (e.g. through fluoride toothpaste). It also found that water fluoridation has limited benefit for adults, because the continued administration of systemic fluoride after the permanent teeth have erupted has questionable efficacy in preventing tooth decay.<ref name=EU2011 /> A 2015 Cochrane review found no conclusive research in adults.<ref name=Ih2015 /> | |||

| ] | |||

| Although anti-fluoridation advocates do not want water fluoridation at all, they also raise concern over the concentration of fluoride that is currently being used. Concentration is measured in parts per million or the equivalent measurement: milligrams per liter (mg/L). The ](EPA) provide guidelines on the level of fluoride to add to the water under the Safe Drinking Water Act and its amendments (1974, 1986, and 1996). These include the maximum contaminant level goal (MCLG), the maximum contaminant level (MCL), and the secondary maximum contaminant level (SMCL). The MCLG of a substance is defined as the maximum level of a contaminant in drinking water at which no known or anticipated adverse effect on the health of persons would occur, and which allows an adequate margin of safety. After the MCLG has been found, "the MCL is then set as close to the MCLG as feasible, which the Safe Drinking Water Act defines as the level that may be achieved with the use of the best available technology, treatment techniques, and other means which EPA finds are available(after examination for efficiency under field conditions and not solely under laboratory conditions) are available, taking cost into consideration." The SMCL is a nonenforceable secondary standard taking into account cosmetic or aesthetic considerations. In 1986 the EPA established an MCLG and MCL for fluoride at a concentration of 4 milligrams per liter (mg/L) and an SMCL of 2 mg/L. In 2006 the National Research Council conducted a report entitled ''Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA’s Standards'' The committee concluded that the current MCLG of 4 mg/L should be lowered to better protect people from the health risks associated with high natural fluoride levels. | |||

| <ref>http://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/faqs.htm EPA: Community Water Fluoridation, FAQ</ref> They now advocate a level of 0.7–1.2 mg/L. | |||

| <ref>http://www.epa.gov/safewater/standard/setting.html EPA: Setting Standards for Safe Drinking Water</ref> <br clear="all" /> Opponents would argue that there is no safe level of fluoride. | |||

| Most countries in Europe have experienced substantial declines in cavities without the use of water fluoridation.<ref name=Pizzo /> For example, in Finland and Germany, tooth decay rates remained stable or continued to decline after water fluoridation stopped. Fluoridation may be useful in the U.S. because unlike most European countries, the U.S. does not have school-based dental care, many children do not visit a dentist regularly, and for many U.S. children water fluoridation is the prime source of exposure to fluoride.<ref name=Burt>{{cite book | vauthors = Burt BA, Tomar SL |chapter=Changing the face of America: water fluoridation and oral health |pages=307–322 |title=Silent Victories: The History and Practice of Public Health in Twentieth-century America | veditors = Ward JW, Warren C |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2007 |isbn=978-0195150698 }}</ref> The effectiveness of water fluoridation can vary according to circumstances such as whether preventive dental care is free to all children.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hausen HW | title = Fluoridation, fractures, and teeth | journal = BMJ | volume = 321 | issue = 7265 | pages = 844–845 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 11021844 | pmc = 1118662 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.321.7265.844 }}</ref> | |||

| {| cellpadding=10 align=right | |||

| |- | |||

| | | |||

| {| border="BORDER" style="border-collapse:collapse;padding:3px;text-align:center;" | |||

| ! colspan=4 style="background:#ffdead;padding:3px" | Schedule for fluoride prescription<ref name="aapdschedule"> (in pdf format), from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| ! style="width:10em" | Age | |||

| ! style="width:5em" colspan=1 | < 0.3 ppm | |||

| ! style="width:5em" colspan=1 | 0.3 - 0.6 ppm | |||

| ! style="width:5em" colspan=1 | >0.6 ppm | |||

| |- | |||

| | Birth - 6 months | |||

| | 0 | |||

| | 0 | |||

| | 0 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 6 months - 3 years | |||

| | .25 mg | |||

| | 0 | |||

| | 0 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 3 years - 6 years | |||

| | .50 mg | |||

| | .25 mg | |||

| | 0 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 6 years - 16 years | |||

| | 1.0 mg | |||

| | .50 mg | |||

| | 0 | |||

| |} | |||

| Dosages are in milligrams F/day; 1.0 ppm = 1 mg/liter.<br> | |||

| Fluoride content of local water supply is in ppm. | |||

| |} | |||

| Both sides of the argument agree that fluoride in high concentrations is harmful to the ]. However advocates of fluoride argue that almost any substance is harmful because ] is based on the amount of exposure.<ref>, from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> In defending water fluoridation, the American Dental Association points out that ], ], ], ], ], and even ] are potentially harmful if given in excessive amounts.<ref name="adafluoridationfacts"> (in PDF format), from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> | |||

| == Ethics == | |||

| Another concern cited in respect of fluoride overexposure is ]. Fluorosis is undesirable because, in severe cases, it discolors teeth, causes surface changes to the ], and makes ] more difficult.<ref>, from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> Government agencies, such as the Center for Disease Control and Prevention, keep records on the ] of fluorosis in the general public.<ref>, from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> Also a concern, ] is a disease in which fluoride deposits into ], causing ] stiffness, joint pain, and sometimes changes in bone shape.<ref>, from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> For skeletal fluorosis to occur, chronic, high level exposure to fluoride is required. A mild form of skeletal fluorosis, ], is seen when levels of fluoride reach 5 parts per million (ppm) and the time of exposure lasts for 10 years.<ref name="adafluoridationfacts"> (in pdf format), from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> | |||

| Water fluoridation pits the common good against individual rights.{{Citation needed|reason=This statement is not self-evident and requires justification|date=July 2018}} Some say the common good overrides individual rights, and equate it to ] and ].<ref name=ethics /><ref name=Cross2003 /> Others say that individual rights override the common good, and say that individuals have no choice in the water that they drink, unless they drink more expensive bottled water,<ref name=Coggon /> and some argue unequivocally that it does not stand up to scrutiny relative to the Nuremberg Code and other codes of medical ethics.<ref name=Cross2003 /> | |||

| The ] cautions that fluoride levels above 1.5 milligrams per liter leaves the risk for fluorosis. | |||

| <ref>, from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> | |||

| Those who emphasize the public good emphasize the ] that appropriate levels of water fluoridation are safe and effective to prevent cavities and see it as a ] intervention, replicating the benefits of naturally fluoridated water, which can free people from the misery and expense of tooth decay and ], with the greatest benefit accruing to those least able to help themselves. This perspective suggests it would be unethical to withhold such treatment.<ref>{{cite book |chapter=The ethics of water fluoridation |chapter-url=https://bfsweb.org/download/1344/one-in-a-million/1Vng0bH7Tc1j0u_L_jJknMBC6OLwiY2TC/The%20ethics%20of%20water%20fluoridation%20(3rd%20edition,%202012) |url=http://bfsweb.org/one-in-a-million |title=One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation |edition=3rd |year=2012 |author1 = The British Fluoridation Society | author2 = The UK Public Health Association | author3 = The British Dental Association | author4 = The Faculty of Public Health |isbn=978-0954768409 |pages=88–92 |publisher=British Fluoridation Society |location=Manchester }}</ref> In her book ''50 Health Scares That Fizzled'', ] writes that, "For lower-income people with no insurance, fluoridated water (like enriched flour and fortified milk) looks more like a free preventative health measure that a few elitists are trying to take away."<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Callahan JR |title=50 health scares that fizzled |date=2011 |publisher=Greenwood |location=Santa Barbara, Calif. |isbn=978-0313385384}}</ref> | |||

| ==Ethics== | |||

| Those who emphasize individual or local choice, may view fluoridation as a violation of ] or legal rules that prohibit medical treatment without medical supervision or informed consent or that prohibit administration of unlicensed medical substances,<ref name=Pizzo /><ref name=LockerCohen2001>{{cite journal | vauthors = Cohen H, Locker D | title = The science and ethics of water fluoridation | journal = Journal | volume = 67 | issue = 10 | pages = 578–580 | date = November 2001 | pmid = 11737979 | url = http://www.cda-adc.ca/jcda/vol-67/issue-10/578.html }}</ref> view it as "mass medication",<ref name=GreenUK2003>{{cite press release | author1-last = Charlton | author1-first = Hugo | author2-last = Fitz-Gibbon | author2-first = Spencer | publisher = UK Green Party | date = 2003-07-08 | url = http://www.greenparty.org.uk/files/reports/2003/F%20illegality.htm | title = Water fluoridation contravenes UK law, EU directives and the European Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine | access-date = 2008-08-03 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20040317205936/http://www.greenparty.org.uk/files/reports/2003/F%20illegality.htm | archive-date = 2004-03-17 | url-status = dead }}</ref> or may even characterize it as a violation of the ] and the Council of Europe's Biomedical Convention of 1999.<ref name=Cross2003 /><ref name=Tiemann2013>{{cite web| vauthors = Tiemann M |title=Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Review of Fluoridation and Regulation Issues|url=https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/RL33280.pdf|access-date=19 April 2016|date=5 April 2013|pages= 1–4}}</ref><ref name="ChengChalmers2007" /> Another journal article suggested applying the ] to this controversy, which calls for ] to reflect a conservative approach to minimize risk in the setting where harm is possible (but not necessarily confirmed) and where the science is not settled.<ref name="Tickner">{{cite journal | vauthors = Tickner J, Coffin M | title = What does the precautionary principle mean for evidence-based dentistry? | journal = The Journal of Evidence-Based Dental Practice | volume = 6 | issue = 1 | pages = 6–15 | date = March 2006 | pmid = 17138389 | doi = 10.1016/j.jebdp.2005.12.006 }}</ref> Others have opposed it on the grounds of potential financial conflicts of interest driven by the chemical industry.<ref name=GreenUK2015>{{Citation| title= Health| work = Record of Policy Statements| publisher = ]| year= 2014| url= http://policy.greenparty.org.uk/he.html| access-date = 2014-11-22 }}</ref> | |||

| One aspect of opposition to water fluoridation regards the social or political implications of adding fluoride to public water supplies. Setting aside the claim that water fluoridation may improve dental health, such an act would violate an individual's right to pursue free choice of, or form of, medical treatment and it is argued that water fluoridation is "compulsory mass medication" because it does not allow proper consent.<ref>, website, accessed 23 February, 2006.</ref> | |||

| A 2007 ] report reached a conclusion mainly on three points, stating that : | |||

| It is also argued that, because of the negative health effects of fluoride exposure, mandatory fluoridation of public water supplies is a "breach of ethics" and a "human rights violation."<ref>, website, accessed 22 February, 2006.</ref> Litigation, both pro and con, has been a frequent outcome of public water fluoridation. | |||

| * The balance of benefit to risk ratio – is unclear due to the lack of good evidence for or against water fluoridation. | |||

| * Alternatives to the practice exist – topical fluoride therapy (toothbrushing, etc.) | |||

| * The role of consent – it gets priority when there are potential harms. | |||

| The report therefore concluded that local and regional democratic procedures are the most appropriate way to decide whether to fluoridate.<ref name=nuffield>{{cite journal | vauthors = Calman K | title = Beyond the 'nanny state': stewardship and public health | journal = Public Health | volume = 123 | issue = 1 | pages = e6–e10 | date = January 2009 | pmid = 19135693 | doi = 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.10.025 | pmc = 7118790 | url = http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/fileLibrary/pdf/One_page_summary_public_health.pdf | publisher = Nuffield Council on Bioethics | access-date = 20 April 2016 | archive-date = 27 March 2009 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20090327113131/http://www.nuffieldbioethics.org/fileLibrary/pdf/One_page_summary_public_health.pdf | url-status = dead }}</ref><ref name=Nuffieldfull>{{cite book|title=Public health : ethical issues (Chapter 7 – Fluoridation of water)|date=2007|publisher=]|location=London|isbn=978-1-904384-17-5|url=http://nuffieldbioethics.org/report/public-health-2/water-fluoridation/|access-date=25 April 2016|archive-date=24 June 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170624000426/http://nuffieldbioethics.org/report/public-health-2/water-fluoridation|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=Community Water Fluoridation in the United States|url=https://www.apha.org/policies-and-advocacy/public-health-policy-statements/policy-database/2014/07/24/13/36/community-water-fluoridation-in-the-united-states|website=www.apha.org|publisher=American Public Health Association|access-date=30 April 2016}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Jiang Y, Foster Page LA, McMillan J, Lyons K, Broadbent J, Morgaine KC | title = Is New Zealand water fluoridation justified? | journal = The New Zealand Medical Journal | volume = 127 | issue = 1406 | pages = 80–86 | date = November 2014 | pmid = 25447252 }}</ref> | |||

| == Opposition groups and campaigns == | |||

| Many advocates of fluoridation do not consider it a violation of people's right to consent to medical treatment. They usually argue that fluoridation is not a form of mass medication because fluoride is naturally present in all water systems.<ref name="adafluoridationfacts"> (in pdf format), from the website, page accessed 18 March, 2006.</ref> Opponents argue that the form of fluoride found in naturally fluoridated water supplies is not the same as the form used to artificially fluoridate water. Likewise, opponents argue that the pharmacy grade fluoride used in many studies to support fluoride as a tooth decay preventative is not the grade used to fluoridate water (although this raises the question of whether the grade of fluoride used to fluoridate water is effective, and also if we can rely on studies that support fluoride use, since they don't use the same fluoride that is in the public water supply). Frequently, those who promote water fluoridation make the comparison to the fortification of other types of foods, such as adding vitamins to ]s and ]s.<ref name="bmastatment"> website, statement on water fluoridation, page accessed March 3, 2006.</ref> | |||

| The controversy is propelled by a significant public opposition supported by a minority of professionals,<ref name="ReferenceA" /> including researchers, dental and medical professionals, alternative medical practitioners such as ], health food enthusiasts, a few religious groups (mostly ] in the U.S.), and occasionally consumer groups and environmentalists.<ref name=Reilly /> Organized political opposition has come from ],<ref name=Dehnbase /> the ],<ref name = "Freeze_2009" /> the ],<ref name=":0" /> and from groups like the Green parties in the UK and New Zealand.<ref name=Greenwars /><ref name=GreenUK2015 /><ref name = "Freeze_2009" />{{rp|219–254}} | |||

| Opposition campaigns involve newspaper articles, talk radio, and public forums. Media reporters are often poorly equipped to explain the scientific issues, and are motivated to present controversy regardless of the underlying scientific merits. Websites, which are increasingly used by the public for health information, contain a wide range of material about fluoridation ranging from factual to fraudulent, with a disproportionate percentage opposed to fluoridation. Antifluoridationist literature links fluoride exposure to a wide variety of effects, including ], ], ], ], ], and low ], along with diseases of the ], ], ], and ], though there is no scientific evidence linking fluoridation to these adverse health effects.<ref name=Armfield>{{cite journal | vauthors = Armfield JM | title = When public action undermines public health: a critical examination of antifluoridationist literature | journal = Australia and New Zealand Health Policy | volume = 4 | pages = 25 | date = December 2007 | pmid = 18067684 | pmc = 2222595 | doi = 10.1186/1743-8462-4-25 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Fact Sheet: Community Water Fluoridation |url=https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/resources/community-water-fluoridation-fact-sheet.html |website=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention |date=2021}}</ref> | |||

| ====The precautionary principle==== | |||

| == Public opinion == | |||

| In an analysis published in the March 2006 issue of the ''Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice,'' the authors examine the water fluoridation controversy in the context of the ]. The authors note that while the precautionary principle is "often criticized as antiscientific," it is based on the notion that: | |||

| Many people do not know that fluoridation is meant to prevent tooth decay, or that natural or bottled water can contain fluoride. As fluoridation does not appear to be an important issue for the general public in the U.S., the debate may reflect an argument between two relatively small ] for and against fluoridation.<ref name=Griffin-opinions /> A survey of Australians in 2009 found that 70% supported and 15% opposed fluoridation. Those opposed were much more likely to score higher on ]s such as "unclear benefits".<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Armfield JM, Akers HF | title = Risk perception and water fluoridation support and opposition in Australia | journal = Journal of Public Health Dentistry | volume = 70 | issue = 1 | pages = 58–66 | year = 2009 | pmid = 19694932 | doi = 10.1111/j.1752-7325.2009.00144.x | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| A study of focus groups from 16 European countries in 2003 found that fluoridation was opposed by a majority of focus group members in most of the countries, including France, Germany, and the UK.<ref name="Griffin-opinions">{{cite journal | vauthors = Griffin M, Shickle D, Moran N | title = European citizens' opinions on water fluoridation | journal = Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology | volume = 36 | issue = 2 | pages = 95–102 | date = April 2008 | pmid = 18333872 | doi = 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00373.x }}</ref> A survey in ], UK, performed in 1999 found that while a 62% majority favored water fluoridation in the city, the 31% who were opposed ] with greater intensity than supporters.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Dixon S, Shackley P | title = Estimating the benefits of community water fluoridation using the willingness-to-pay technique: results of a pilot study | journal = Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology | volume = 27 | issue = 2 | pages = 124–129 | date = April 1999 | pmid = 10226722 | doi = 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb02001.x }}</ref> Every year in the U.S., pro- and anti-fluoridationists face off in ]s or other public decision-making processes: in most of them, fluoridation is rejected.<ref name="Reilly" /> | |||

| <blockquote>f there is uncertainty, yet credible scientific evidence or concern of threats to health, precautionary measures should be taken. In other words, preventive action should be taken on early warnings even though the nature and magnitude of the risk are not fully understood.<ref>Tickner J, Coffin M. (2006). ''What does the precautionary principle mean for evidence-based dentistry?'' Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice, Issue 6, pages 6-15.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| == Use throughout the world == | |||

| The authors note that “The need for precaution arises because the costs of inaction in the face of uncertainty can be high, and paid at the expense of sound public health.” | |||

| {{Main|Fluoridation by country}} | |||

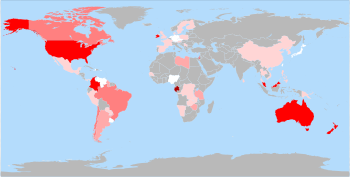

| [[File:Water-fluoridation-extent-world-equirectangular.svg|350px|thumb|alt=World map showing countries in gray, white and in various shades of red. The U.S. and Australia stand out as bright red (which the caption identifies as the 60–80% color). Brazil and Canada are medium pink (40–60%). China, much of western Europe, and central Africa are light pink (1–20%). Germany, Japan, Nigeria, and Venezuela are white (<1%).|Percentage of population receiving fluoridated water, including both artificial and natural fluoridation, as of 2012:<ref name="extent">{{cite book |chapter=The extent of water fluoridation |chapter-url=http://bfsweb.org/onemillion/09%20One%20in%20a%20Million%20-%20The%20Extent%20of%20Fluoridation.pdf |url=http://bfsweb.org/onemillion/onemillion.htm |title=One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation |edition=2nd |year=2004 |publisher=The British Fluoridation Society, The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health |isbn=978-0-9547684-0-9 |pages=55–80 |location=Manchester |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081122032013/http://www.bfsweb.org/onemillion/onemillion.htm |archive-date=22 November 2008 |df=dmy-all }}</ref>{{div col|colwidth=5em}} | |||

| {{legend|#aa0000|{{nowrap|80–100%}}|border=1px solid #aaa}} | |||

| {{legend|#ff0000|{{nowrap|60–80%}}|border=1px solid #aaa}} | |||

| {{legend|#ff8080|{{nowrap|40–60%}}|border=1px solid #aaa}} | |||

| {{legend|#ffaaaa|{{nowrap|20–40%}}|border=1px solid #aaa}} | |||

| {{legend|#ffd5d5|{{nowrap|1–20%}}|border=1px solid #aaa}} | |||

| {{legend|#ffffff|{{nowrap|< 1%}}|border=1px solid #aaa}} | |||

| {{legend|#b9b9b9|unknown|border=1px solid #aaa}}{{div col end}}]] | |||

| A 2012 study found that 25 countries have artificial water fluoridation to varying degrees, with 11 of them delivering fluoridated water to more than 50% of their population. It found that a further 28 countries have water that is naturally fluoridated, though in many of them the fluoride concentration is above the maximum recommended level. About 435 million people worldwide received water fluoridated at the recommended level,<ref name="extent2012" /><!-- Page 56 --> with about 211 million of them living in the United States.<ref name="US-CDC-WF-Stats-2012">{{cite web |date=2018-04-20 |title=Community Water Fluoridation … 2012 Water Fluoridation Statistics |url=https://www.cdc.gov/fluoridation/statistics/2012stats.htm |access-date=13 October 2018 |work=cdc.gov}}</ref> | |||

| In determining whether the precautionary principle should be applied to fluoridation, the authors note that: | |||

| * There are other ways of delivering fluoride besides the water supply; | |||

| * Fluoride does not need to be swallowed to prevent tooth decay; | |||

| * Tooth decay has dropped at the same rate in countries with, and without, water fluoridation; | |||

| * People are now receiving fluoride from many other sources besides the water supply; | |||

| * Studies indicate fluoride’s potential to cause a wide range of adverse, systemic effects; | |||

| * Since fluoridation affects so many people, “one might accept a lower level of proof before taking preventive actions.” <ref>Tickner J, Coffin M. (2006). ''What does the precautionary principle mean for evidence-based dentistry?'' Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice, Issue 6, pages 6-15.</ref> | |||

| Despite support by public health organizations and dental authorities, the practice is controversial as a public health measure; some countries and communities have discontinued it, while others have expanded it.<ref name="Scher2011" /><ref name="Tiemann2013" /> In the U.S., rejection in state and local communities is more likely when the decision is made by a public referendum; in Europe, most decisions against fluoridation have been made administratively.<ref name="Martin1989">{{cite journal | vauthors = Martin B |year=1989 |title=The sociology of the fluoridation controversy: a reexamination |journal=Sociol. Q. |volume=30 |issue=1 |pages=59–76 |doi=10.1111/j.1533-8525.1989.tb01511.x |url=http://www.uow.edu.au/~bmartin/pubs/89sq.html }}</ref> Neither side of the dispute appears to be weakening or willing to concede.<ref name="Reilly" /> | |||

| ==Opposition from health authorities== | |||

| Water fluoridation is used in the United States, United Kingdom, Ireland, Canada, Australia, Israel, Hong Kong and a handful of other countries. Most countries failed to adopt fluoridation, yet experienced the same or greater decline in cavities as those countries that did fluoridate during the later half of the twentieth century.<ref name="pmid3523258">{{cite journal | vauthors = Diesendorf M | title = The mystery of declining tooth decay | journal = Nature | volume = 322 | issue = 6075 | pages = 125–129 | date = 1986 | pmid = 3523258 | doi = 10.1038/322125a0 | bibcode = 1986Natur.322..125D | s2cid = 4357504 }}</ref> The following nations previously fluoridated their water, but stopped the practice, with the years when water fluoridation started and stopped in parentheses: | |||

| In 2005, eleven environmental protection agency ] employee unions, representing over 7000 environmental and public health professionals of the Civil Service, called for a halt on drinking water fluoridation programs across the USA and asked EPA management to recognize fluoride as posing a serious risk of causing ] in people. The unions acted on an apparent cover-up of evidence from ] School of Dental Medicine linking fluoridation with an elevated risk of ] in boys, a rare but fatal bone cancer.<ref>The Washington Post: "Professor at Harvard Is Being Investigated" http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/07/12/AR2005071201277.html</ref> | |||

| * Federal Republic of Germany (1952–1971) | |||

| * Sweden (1952–1971) | |||

| * Netherlands (1953–1976) | |||

| * Czechoslovakia (1955–1990) | |||

| * German Democratic Republic (1959–1990) | |||

| * Soviet Union (1960–1990) | |||

| * Finland (1959–1993) | |||

| * Japan (1952–1972)<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Furukawa S, Hagiwara Y, Taguchi C, Turumoto A, Kobayashi S | title = Associations between oral health behavior and anxiety about water fluoridation and motivation to establish water fluoridation in Japanese residents | journal = Journal of Oral Science | volume = 53 | issue = 3 | pages = 313–319 | date = September 2011 | pmid = 21959658 | doi = 10.2334/josnusd.53.313 | doi-access = free }}</ref> | |||

| * Israel (1981–2014, 2016–) *Mandatory by law since 2002.<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Zwebner S | date = 17 March 2014 | url = https://www.knesset.gov.il/mmm/data/pdf/m00204.pdf | title = הפלרת מי השתייה | trans-title = Fluoridation of drinking water | language = Hebrew | pages = 2–3 | quote = Dates of beginning of Water fluoridation practice in Israel: 1981 Optional, 2002 Mandatory) | publisher = ] Research and Information Center | access-date = 2 September 2014 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Main D | date = 29 August 2014 | url = http://www.newsweek.com/israel-has-officially-banned-fluoridation-its-drinking-water-267411 | title = Israel Has Officially Banned Fluoridation of Its Drinking Water | work = ] | access-date = 2 September 2014 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Water fluoridation set to return in Israel |date=11 April 2016 |url=http://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2016-archive/april/water-fluoridation-set-to-return-in-israel |work=ADA News |publisher=American Dental Association |access-date=10 January 2017 |archive-date=10 March 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190310102412/https://www.ada.org/en/publications/ada-news/2016-archive/april/water-fluoridation-set-to-return-in-israel |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| Water had been fluoridated in Israel in all major cities since 1981. This was stopped by the Minister of Health in 2014<ref>{{Cite news |last=Main |first=Douglas|date=2014-08-29 |title=Israel Bans Water Fluoridation |url=https://www.newsweek.com/israel-has-officially-banned-fluoridation-its-drinking-water-267411 |access-date=2024-12-01 |website=Newsweek |language=en}}</ref> which was met with backlash.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2014-06-22 |title=Backlash against Health Minister Yael German for her decision to stop fluoridation |url=https://www.jpost.com/Health-and-Science/Backlash-against-Health-Minister-Yael-German-for-her-decision-to-stop-fluoridation-360188 |access-date=2024-12-01 |work=The Jerusalem Post |language=en}}</ref> The subsequent Minister of Health in 2016 ordered the reintroduction of fluoride to Israel's public drinking water.<ref>{{Cite news |date=2017-08-22 |title=Israel's fluoridation supply expected to be restored after three years |url=https://www.jpost.com/HEALTH-SCIENCE/Israels-fluoridation-supply-expected-to-be-restored-after-three-years-503121 |access-date=2024-12-01 |work=The Jerusalem Post |language=en}}</ref> Due to budgetary constraints, it has never taken effect.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.gov.il/en/pages/water-fluoridation |access-date=2024-12-01 |website=www.gov.il}}</ref> Dental health professionals and scholarly journals have noted the steep rise in tooth decay, especially in children due to the removal of fluoride in tap water in Israel.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Tobias |first1=Guy |last2=Mordechai |first2=Findler |last3=Tali |first3=Chackartchi |last4=Yaron |first4=Bernstein |last5=Beatrice |first5=Greenberg Parizer |last6=Jonathan |first6=Mann |last7=Harold |first7=Sgan-Cohen |date=2022-01-28 |title=The effect of community water fluoridation cessation on children's dental health: a national experience |journal=Israel Journal of Health Policy Research |volume=11 |issue=1 |pages=4 |doi=10.1186/s13584-022-00514-z |doi-access=free |issn=2045-4015 |pmc=8796457 |pmid=35090561}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=PDF file from Editorial Manager |url=http://dx.doi.org/10.15438/rr.4.4.22 |access-date=2024-12-01 |doi=10.15438/rr.4.4.22 |doi-broken-date=2 December 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| In the United Kingdom a ] can direct a water company to fluoridate the water supply in an area if it is technically possible. The strategic health authority must consult with the local community and businesses in the affected area. The water company will act as a contractor in any new schemes and cannot refuse to fluoridate the supply.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.unitedutilities.com/About-your-water.aspx |title=About your water |publisher=United Utilities }}</ref> In areas with complex water sources, water fluoridation is more difficult and more costly. Alternative fluoridation methods have been proposed, and implemented in some parts of the world. The ] (WHO) is currently assessing the effects of fluoridated toothpaste, milk fluoridation and salt fluoridation in Africa, Asia, and Europe. The WHO supports fluoridation of water in some areas.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.who.int/entity/oral_health/media/en/orh_report03_en.pdf |title=World Oral Health Report |publisher=] |access-date=4 March 2006}}</ref> In some other countries, ] is added to table salt.<ref>{{cite web | vauthors = Ackermann-Liebrich U, Autrup H, Bard D, Calow P, Michaelidou SC, Davison J, Dekant W, de Voogt P, Gard A, Greim H, Hirvonen A, Janssen C, Linders J, Peterlin B, Tarazona J, Testai E, Vighi M | display-authors = 6 | collaboration = Scientific Committee on Health and Environmental Risks | date = 18 May 2010 |title=Critical review of any new evidence on the hazard profile, health effects, and human exposure to fluoride and the fluoridating agents of drinking water |url=http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/environmental_risks/docs/scher_o_122.pdf | publisher = European Commission }}, citing {{cite journal | vauthors = Götzfried F | title = Production of fluoridated salt | journal = Schweizer Monatsschrift für Zahnmedizin = Revue Mensuelle Suisse d'Odonto-Stomatologie = Rivista Mensile Svizzera di Odontologia e Stomatologia | volume = 116 | issue = 4 | pages = 367–370 | year = 2006 | pmid = 16708522 }}</ref> | |||

| In addition, over 1,700 health industry professionals, including doctors, dentists, scientists and researchers from a variety of disciplines are calling for an end to water fluoridation in an online petition to Congress. | |||

| == History == | |||

| Their petition highlights eight recent events that they say mandates a moratorium on water fluoridation, including a 500-page review of fluoride’s toxicology that was published in 2006 by a distinguished panel appointed by the ] of the ]. While the NRC report did not specifically examine artificially fluoridated water, it concluded that the ] ] safe drinking water standard of 4 parts per million (ppm) for fluoride is unsafe and should be lowered. Despite over 60 years of water fluoridation in the U.S, there are no double-blind studies which prove fluoride's effectiveness in tooth decay. The panel reviewed a large body of literature in which fluoride has a statistically significant association with a wide range of adverse effects.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{Main|History of water fluoridation}} | |||

| Fluoridation began during a time of great optimism and faith in science and experts (the 1950s and 1960s); even then, the public frequently objected. Opponents drew on distrust of experts and unease about medicine and science.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Carstairs C, Elder R |title=Expertise, health, and popular opinion: debating water fluoridation, 1945–80 |journal=Can. Hist. Rev. |volume=89 |issue=3 |pages=345–371 |year=2008 |doi=10.3138/chr.89.3.345 }}</ref> Controversies include disputes over fluoridation's benefits and the strength of the evidence basis for these benefits, the difficulty of identifying harms, legal issues over whether water fluoride is a medicine, and the ethics of mass intervention.<ref name="ChengChalmers2007" /> | |||

| Several prominent dental researchers and government advisors who were leaders of the pro-fluoridation movement have announced reversals of their former positions after they concluded that water fluoridation is not an effective means of reducing dental caries and that it poses serious risks to human health. The late Dr. John Colquhoun was Principal Dental Officer of ], ]. In an article titled, ''"Why I changed my mind about water fluoridation''", he published his reasons for changing sides. <ref>http://www.fluoride-journal.com/98-31-2/312103.htm ''Why I changed my mind about water fluoridation.'' Colquhoun, J. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine 41 1-16 (1997)</ref> | |||