| Revision as of 03:47, 23 August 2005 view sourceVivafelis (talk | contribs)158 editsm →Modern Kiev: - Spelling fix← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 13:31, 27 December 2024 view source Shwabb1 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,043 edits Added/fixed links and a template; other fixesTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Capital of Ukraine}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{About|the capital of Ukraine}} | |||

| ], the protector of Kiev, with today's city center in the background.]] | |||

| {{Pp-extended|small=yes}} | |||

| {{infobox Kiev}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| '''Kiev''' ({{lang-ua|'''Київ''', ''Kyiv''}}; ]: '''{{Audio|ru-Kiev.ogg|Киев}}''', ''Kiev''), also '''Kyiv''', is the ] and the largest city of ], located in the north central part of the country on the ] river. ], Kiev officially had 2,642,486 inhabitants, although the large number of unregistered ]s would probably raise this figure to about 3 million. Administratively, Kiev is a national-level subordinated ], independent from surrounding ]. Kiev is an important industrial, scientific, educational and cultural center of ]. It is home to many high-tech industries, ] institutions, world-famous ]s and ] institutions. The city has an extensive infrastructure and highly developed system of ], including a ] system. | |||

| {{Use American English|date=April 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox settlement | |||

| | name = Kyiv | |||

| | native_name = {{lang|uk|Київ}} | |||

| | other_name = Kiev | |||

| | settlement_type = ] and ] | |||

| <!-- images, nickname, motto -->| image_skyline = {{multiple image | |||

| | perrow = 1/2/2/1 | |||

| | border = infobox | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| | image1 = 17-07-02-Maidan Nezalezhnosti RR74377-PANORAMA.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = ] | |||

| | image2 = P1130119-1.JPG | |||

| | caption2 = ] | |||

| | image3 = Червоний корпус КНУ.JPG | |||

| | caption3 = ] | |||

| | image4 = Будинок з химерами, серпень 2019.jpg | |||

| | caption4 = ] | |||

| | image5 = Софійський собор Київ.jpg | |||

| | caption5 = ] | |||

| | image6 = Маріїнський палац в Києві (cropped).jpg | |||

| | caption6 = ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | imagesize = 300px | |||

| | image_alt = | |||

| | image_caption = | |||

| | image_flag = Flag of Kyiv Kurovskyi.svg | |||

| | flag_size = | |||

| | flag_alt = | |||

| | image_shield = COA of Kyiv Kurovskyi.svg | |||

| | shield_size = 75px | |||

| | shield_alt = | |||

| | image_blank_emblem = Kyiv logo english.svg | |||

| | blank_emblem_type = ] | |||

| | blank_emblem_size = | |||

| | blank_emblem_alt = | |||

| | nickname = Mother of ] Cities<ref name="auto">{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Kyiv|title=Kyiv – History|website=Encyclopædia Britannica|language=en|access-date=9 March 2020|archive-date=4 May 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150504135716/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/317542/Kiev|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | nicknames = | |||

| | motto = | |||

| | mottoes = | |||

| | anthem = ]<br />{{center|]}} | |||

| <!-- maps and coordinates -->| image_map = {{Maplink|frame=yes|plain=y|frame-width=300|frame-height=300|frame-align=center|stroke-width=2|zoom=9|type=shape-inverse|stroke-color=#808080|fill=#808080|title=Kyiv|id=Q1899|fill-opacity=0.4|frame-coordinates={{Coord|50.40|30.54}}}} | |||

| | mapsize = 300px | |||

| | map_alt = Interactive map of Kyiv | |||

| | map_caption = Interactive map of Kyiv | |||

| | pushpin_map = Ukraine#Europe | |||

| | pushpin_mapsize = 300px | |||

| | pushpin_map_alt = | |||

| | pushpin_map_caption = Kyiv in Ukraine | |||

| | pushpin_map_caption_notsmall = | |||

| | pushpin_label = <!-- only necessary if "name" or "official_name" are too long --> | |||

| | pushpin_label_position = <!-- position of the pushpin label: left, right, top, bottom, none --> | |||

| | coordinates = {{Coord|50|27|00|N|30|31|24|E|region:UA-30_type:city|display=inline, title}} <!-- Please note: these are the nearest DMS coords to a "center marker of Ukraine" sculpture of a blue globe--> | |||

| | coor_pinpoint = <!-- to specify exact location of coordinates (was coor_type) --> | |||

| | coordinates_footnotes = <!-- for references: use <ref> tags --> | |||

| | grid_name = <!-- name of a regional grid system --> | |||

| | grid_position = <!-- position on the regional grid system --> | |||

| <!-- location -->| subdivision_type = ] | |||

| | subdivision_name = ] | |||

| | subdivision_type1 = ] | |||

| | subdivision_name1 = ] | |||

| <!-- established -->| established_title = Founded | |||

| | established_date = {{CE|482|link=y}} (officially)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kyivpost.com/guide/about-kyiv/kyivs-1530th-birthday-marked-with-fun-protest-1-128618.html|title=Kyiv's 1,530th birthday marked with fun, protest|author=Oksana Lyachynska|date=31 May 2012|website=Kyiv Post|access-date=16 May 2013|archive-date=1 June 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140601085436/http://www.kyivpost.com/guide/about-kyiv/kyivs-1530th-birthday-marked-with-fun-protest-1-128618.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | founder = | |||

| | named_for = ] | |||

| <!-- seat, smaller parts -->| seat_type = ] | |||

| | seat = ] | |||

| | parts_type = ] | |||

| | parts_style = <!-- list, coll (collapsed list), para (paragraph format) --> | |||

| | parts = List of 10 | |||

| | p1 = ] | |||

| | p2 = ] | |||

| | p3 = ] | |||

| | p4 = ] | |||

| | p5 = ] | |||

| | p6 = ] | |||

| | p7 = ] | |||

| | p8 = ] | |||

| | p9 = ] | |||

| | p10 = ] | |||

| <!-- government type, leaders -->| government_footnotes = <!-- for references: use <ref> tags --> | |||

| | leader_party = | |||

| | leader_title = ] | |||

| | leader_name = ]<ref name=KKMs5614/><ref name="Poroshenko appoints Klitschko head of Kyiv city administration - decree"/> | |||

| <!-- display settings -->| unit_pref = Metric | |||

| <!-- area -->| area_footnotes = <!-- for references: use <ref> tags --> | |||

| | area_total_km2 = 839 | |||

| | area_total_sq_mi = 324 | |||

| <!-- elevation -->| elevation_m = 179 | |||

| | elevation_ft = 587 | |||

| <!-- population -->| population_footnotes = | |||

| | population_as_of = 1 January 2021 | |||

| | population_total = {{DecreaseNeutral}} 2,952,301<ref name="Number of present population of Ukraine 1 January 2022"/> | |||

| | pop_est_footnotes = | |||

| | pop_est_as_of = | |||

| | population_est = | |||

| | population_rank = ] in Ukraine<br />] in Europe | |||

| | population_density_km2 = 3299 | |||

| | population_density_sq_mi = 8540 | |||

| | population_metro_footnotes = | |||

| | population_metro = 3,475,000<ref name="citypopulation.de">{{cite web | url=http://www.citypopulation.de/world/Agglomerations.html | title=Major Agglomerations of the World | publisher=Citypopulation.de | date=1 January 2021 | access-date=23 September 2021 | archive-date=23 November 2019 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191123050211/http://citypopulation.de/world/Agglomerations.html | url-status=live }}</ref> of the ] | |||

| | population_density_metro_km2 = | |||

| | population_density_metro_sq_mi = | |||

| | population_demonym = Kyivan,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Definition of KYIV |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kyiv |access-date=2023-05-11 |website=Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary |language=en |archive-date=28 September 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220928161317/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kyiv |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Kyiv definition and meaning |url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/kyiv |access-date=2023-05-11 |website=Collins English Dictionary |archive-date=28 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221128125544/http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/kyiv |url-status=live }}</ref> Kievan<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130314083809/http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/kievan |date=14 March 2013 }}, retrieved 29 May 2013 from Dictionary.com</ref> | |||

| <!-- demographics (section 1) --> <br/> Киянин, Киянка (]) | |||

| | demographics_type1 = ] | |||

| | demographics1_footnotes = <ref>{{Cite web|title= ВАЛОВИЙ РЕГІОНАЛЬНИЙ ПРОДУКТ У 2021 РОЦІ|url= https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2023/05/zb_vrp_2021.xlsx&ved=2ahUKEwjY1N_wjK-AAxVL8LsIHfbyBoIQFnoECBEQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3p1PStO6ejpZRSYd9Ix41p|website=ukrstat.gov.ua}}</ref> | |||

| | demographics1_title1 = ] and ] | |||

| |demographics1_info1 = ]{{FXConvert|UKR|1276|b|lk=on}} (2021) | |||

| |demographics1_title2 = Per capita | |||

| |demographics1_info2 = ₴{{FXConvert|UKR|431616|lk=on}} (2021) | |||

| <!-- time zone(s) -->| timezone1 = ] | |||

| | utc_offset1 = +2 | |||

| | timezone1_DST = ] | |||

| | utc_offset1_DST = +3 | |||

| <!-- postal codes, area code -->| postal_code_type = Postal code | |||

| | postal_code = 01xxx–04xxx | |||

| | area_code_type = | |||

| | area_code = +380 44 | |||

| | registration_plate_type = ] | |||

| | registration_plate = AA, KA (before 2004: КА, КВ, КЕ, КН, КІ, KT) | |||

| | iso_code = UA-30 | |||

| <!-- blank fields (section 1) -->| blank_name_sec1 = ] | |||

| | blank_info_sec1 = ] | |||

| <!-- website, footnotes -->| website = | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Kyiv''' (also '''Kiev'''){{efn|See {{slink||Name}} for alternative spellings and pronunciations.}} is the capital and most populous ] of ]. It is in north-central Ukraine along the ]. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2,952,301,<ref name="Number of present population of Ukraine 1 January 2022">{{cite web | url=https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2022/zb/05/zb_%D0%A1huselnist.pdf | title=Number of present population of Ukraine 1 January 2022 | publisher=UkrStat.gov.ua | language=uk | date=1 January 2022 | access-date=20 February 2023 | archive-date=10 August 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220810155123/https://ukrstat.gov.ua/druk/publicat/kat_u/2022/zb/05/zb_%D0%A1huselnist.pdf | url-status=live }}</ref> making Kyiv the ] city in Europe.<ref>{{cite web|title=City Mayors: The 500 largest European cities (1 to 100)|url=http://www.citymayors.com/features/euro_cities1.html|website=www.citymayors.com|access-date=19 February 2017|archive-date=2 January 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100102120542/http://citymayors.com/features/euro_cities1.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Kyiv is an important industrial, scientific, educational, and cultural center in ]. It is home to many ] industries, higher education institutions, and historical landmarks. The city has an extensive system of ] and infrastructure, including the ]. | |||

| In ] Kiev, one of the earliest cities in the Eastern Europe, passed through several stages of the great prominence and relative obscurity. Founded probably in the ], a trading post in the land of ], the city gradually acquired the eminence as the center of the ], in ] - ] centuries a political and cultural capital of ]. Completely destroyed during the ] in ], the city lost most of its influence for the centuries to come. It was a provincial capital of marginal importance in the outskirts of the territories controlled by its powerful neighbors: the ], the ] and the ], later the ]. The city prospered again during the Russian ] in the late ]. After the turbulent period following the ] (]), from ] Kiev was an important city of the ], and, since ], its capital. During ], the city was destroyed again, almost completely, but quickly recovered in the post-war years becoming the third most important city of the ]. It now remains the capital of Ukraine, independent since ] following the ]. | |||

| The city's name is said to derive from the name of ], one of its four legendary founders. During ], Kyiv, one of the oldest cities in Eastern Europe, passed through several stages of prominence and obscurity. The city probably existed as a commercial center as early as the 5th century. A ] settlement on the great trade route between ] and ], Kyiv was a tributary of the ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/kiev|title=Kiev|work=TheFreeDictionary.com|access-date=4 July 2015|archive-date=5 August 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180805021737/https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Kiev|url-status=live}}</ref> until its capture by the ] (]) in the mid-9th century. Under Varangian rule, the city became a capital of ], the first ] state. Completely ] during the ] in 1240, the city lost most of its influence for the centuries to come. Coming under ], then ] and then ], the city would grow from a frontier market into an important centre of Orthodox learning in the sixteenth century, and later of industry, commerce, and administration by the nineteenth.<ref name="auto"/> | |||

| == Geography and climate == | |||

| The city prospered again during the Russian Empire's ] in the late 19th century. In 1918, when the ] declared independence from the ] after the ] there, Kyiv became its capital. From the end of the ] and ] wars in 1921, Kyiv was a city of the ], and made its capital in 1934. The city suffered significant destruction during ] but quickly recovered in the postwar years, remaining the ]'s third-largest city. | |||

| Kiev is located on both sides of the Dnieper river which flows south through the city towards the ]. Its ] are {{coor dm |50|27|N|30|30|E|type:city(2600000)_scale:300000_region:ua}}. Geographically, Kiev belongs to the ] natural zone (a part of the European mixed woods). However, the city's unique landscape distinguishes it from the surrounding region. The elder right-bank (western) part of Kiev is represented by numerous woody hills, ravines and small rivers (now mostly extinct). It is a part of the larger Prydniprovska (''near-Dnieper'') upland adjoining the western bank of the Dnieper. The left-bank (eastern) part of the city was built in the Dnieper valley. Significant areas of it were artificially sand-deposited and enforced by ]s. | |||

| Following ] and ] in 1991, Kyiv remained Ukraine's capital and experienced a steady ] of ] migrants from other ].<ref name="History of Ukraine">{{cite book|last=Magocsi|first=Paul Robert|title=A History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Z0mKRsElYNkC&pg=PT481|edition=2nd, Revised|year=2010|publisher=University of Toronto Press|isbn=978-1-4426-9879-6|page=481|access-date=9 September 2017|archive-date=14 June 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614025229/https://books.google.com/books?id=Z0mKRsElYNkC&pg=PT481|url-status=live}}</ref> During the country's transformation to a ] and ], Kyiv has continued to be Ukraine's largest and wealthiest city. Its armament-dependent industrial output fell after the Soviet collapse, adversely affecting science and technology, but new sectors of the economy such as services and ] facilitated Kyiv's growth in salaries and investment, as well as providing continuous funding for the development of ] and urban infrastructure. Kyiv emerged as the most ] region of Ukraine; ] advocating tighter ] dominate during ]. | |||

| The river forms a branching system of ], isles and harbors within city limits. The city is adjoined by the mouth of the ] and the ] in the north, and the ] in the south. Both Dnieper and Desna around Kiev are ], although regulated by the reservoir shipping locks and limited by winter freezing-over. | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| Kiev's ] is continental humid, although it has changed significantly during recent decades due to ] climate changes. | |||

| {{seealso|Names of Kyiv}} | |||

| ]'', 1552, showing Kyiv labelled "Kyouia ep''iscop''atus" ("Kyiv episcopate")]] | |||

| *{{langx|en|Kyiv}} ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|iː|ɪ|v}} {{respell|KEE|iv}},<ref>{{cite tweet|last=Preston|first=Rich|user=RichPreston|number=1497147957996630017|title=And here's what the BBC Pronunciation Unit advises. We changed our pronunciation and spelling of Kiev to Kyiv in 2019.}}</ref> {{IPAc-en|k|iː|v}} {{respell|KEEV}}<ref>{{cite Merriam-Webster|Kyiv|access-date=24 February 2022}}</ref>) or Kiev ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|iː|ɛ|v}} {{respell|KEE|ev}})<ref>{{cite EPD|18}}</ref><ref name="lpd3">{{cite LPD|3}}</ref> | |||

| *{{langx|uk|Київ|translit=Kyiv}}, {{IPA|uk|ˈkɪjiu̯|pron|uk-Київ.ogg}}<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Kyjiw|title=Kyjiw|work=]|language=de|access-date=2024-11-29}}</ref> | |||

| *{{langx|ru|Киев|translit=Kiyev}},{{efn|]: Кіевъ}} {{IPA|ru|ˈkʲi(j)ɪf|pron|Ru-Киев.ogg}}<ref name="lpd3"/> | |||

| The traditional etymology, stemming from the '']'', is that the name is a derivation of ] ({{langx|uk|Кий|links=no}}, {{langx|ru|Кий|links=no}},{{efn|]: Кій}} {{small|]:}} ''Ky''<!--WP:RUS--> or ''Kiy''), the legendary eponymous founder of the city. According to ]'s etymological dictionary from the ] name ''*Kyjevŭ gordŭ'' (literally, "Kyi's castle", "Kyi's ]"), from ] ''*kyjevъ'',<ref>{{Cite encyclopedia|title=*kyjevъ/*kyjevo|date=1987|dictionary=Ėtimologicheskiĭ slovarʹ slavi͡anskikh I͡Azykov: Praslavi͡anskiĭ leksicheskiĭ fond|language=ru|editor-last=Trubachev|editor-first=O. N.|editor-link=Oleg Trubachyov|volume=13 (*kroměžirъ–*kyžiti)|publisher=Nauka|location=Moscow|pages=256–257}}</ref> This etymology has been questioned, for instance by ] who called it an "etymological myth", and meant that the names of the legendary founders are in turn based on place names. According to the Canadian Ukrainian linguist ], the name can be connected to the Proto-Slavic root ], but should be interpreted as meaning 'stick, pole' as in its modern Ukrainian equivalent ]. The name should in that case be interpreted as 'palisaded settlement'.<ref>Rudnyc'kyj, Jaroslav Bohdan (1962–1982). An etymological dictionary of the Ukrainian language. 2., rev. ed. Winnipeg: Ukrainian free acad. of sciences, pp. 660–663.</ref> | |||

| ==Modern Kiev== | |||

| Today, Kiev is a modern city with over 2.5 million inhabitants. Like many other large cities of the the former ], it is a mix of the old and the new, seen in everything from the buildings to the stores to the people themselves. Experiencing a fast growth rate during the ], ] and the early- to mid-], Kiev has continued its consistent growth after 5 years of resturcturing. As a result, today, even Kiev's "downtown" is a dotted picture of the new, modern buildings (known as ]) amongst the pale yellows, blues and grays of the older apartments. During the last growth period, urban sprawl has been gradually reduced while population densities of suburbs started increasing. Today, it is rather popular to own a novostroika in ], ], ] along the Dnieper, around ] as well as in ] or other better established areas. | |||

| ''Kyiv'' is the romanized official Ukrainian name for the city,<ref name="collins">{{Cite web|title=Kiev|url=https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/kiev|access-date=14 November 2020|website=Collins English Dictionary|publisher=HarperCollins|language=en|archive-date=1 May 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210501212120/https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/kiev|url-status=live}} The entry is the same as the print edition of {{Cite book|title=Collins Dictionary of English|publisher=HarperCollins|year=2018|edition=13th|location=Glasgow, UK}} It includes the note "''Ukrainian name'': Kyiv". For American English, the website also includes the definition from {{Cite book|title=Webster's New World College Dictionary|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Harcourt|year=2010|edition=4th|location=Boston}} In the 2018 fifth edition, WNWCD changed the main headword to ''Kyiv'', with ''Kiev'' as a see-also entry with the label "Russ. name for '''Kyiv'''".</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Kiev|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kiev|access-date=14 November 2020|website=Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary|publisher=Merriam-Webster|language=en|archive-date=13 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201113053916/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Kiev|url-status=live}} Merriam–Webster's online dictionary entry has the headword "'''Kiev'''" with the label "variants: ''or Ukrainian'' '''Kyiv''' ''or'' '''Kyyiv'''." According to M–W's {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200811071307/https://www.merriam-webster.com/help/explanatory-notes/dict-usage |date=11 August 2020 }}, the key word ''or'' signals an equal variant spelling: "these the two spellings occur with equal or nearly equal frequency and can be considered equal variants. Both are standard, and either one may be used according to personal inclination."</ref> and it is used for legislative and official acts.<ref name=":1">{{cite web|last=Ukrainian Commission for Legal Terminology|title=Kiev?, Kyiv?! Which is right?|url=http://www.uazone.net/Kiev_Kyiv.html|access-date=15 March 2011|publisher=UA Zone|archive-date=26 May 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110526012255/http://www.uazone.net/Kiev_Kyiv.html|url-status=live}}</ref> ''Kiev'' is the traditional English name for the city,<ref name="collins" /><ref>{{Cite web|title=Kiev|url=https://www.lexico.com/definition/kiev|access-date=14 November 2020|website=Oxford Dictionary on Lexico.com|language=en|archive-date=12 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201112023014/https://www.lexico.com/definition/kiev|url-status=dead}} The entry includes the usage note "Ukrainian name '''Kyiv'''", and the dictionary has a see-also entry for "Kyiv" cross-referencing this one. The entry text is republished from the print edition of the {{Cite book|title=Oxford Dictionary of English|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2010|edition=3rd}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Kiev|url=https://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/kiev|access-date=14 November 2020|website=Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English Online|publisher=Pearson English Language Teaching|archive-date=6 May 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170506050832/http://www.ldoceonline.com/dictionary/kiev|url-status=live}}</ref> but because of its historical derivation from the Russian name, ''Kiev'' lost favor with many Western media outlets after the outbreak of the ] in 2014 in conjunction with the ] campaign launched by Ukraine to change the way that international media were spelling the city's name.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/kyiv-not-kiev-why-spelling-matters-in-ukraines-quest-for-an-independent-identity/ |title=Kyiv not Kiev: Why spelling matters in Ukraine's quest for an independent identity |date=21 October 2019 |publisher=] |access-date=26 May 2021 |archive-date=19 January 2020 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20200119141129/https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/ukrainealert/kyiv-not-kiev-why-spelling-matters-in-ukraines-quest-for-an-independent-identity/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| With the Ukrainian independence on the turn of the millenium, new changes came. The Western-style novostroikas, hip nightclubs, classy restaurants and prestigious hotels opened in the center. Music from ] and the ] started rising on Ukrainian music charts. And most importantly, with the changes in visa rules in ], Ukraine is positioning itself as a prime tourist attraction, with Kiev, among the other large cities, looking to profit from the new opportunities. The center of Kiev has been cleaned up and buildings have been restored and redecorated, especially Khreschatyk and Independence Square. Many of the historical places of Kiev, such as Andryivskyi Uzviz, have become popular street vendor locations, where one can buy traditional Ukrainian art, religious items, books, game sets (most commonly chess) as well as jewellery. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| With the partial collapse of the Kiev transit services, private investors have seen room for profit. While the publicly owned and operated ] system remains the fastest, the most convenient and affordable network that covers most, but not all, of the city, the ]s (private microbuses) have become the next most popular method of tranposrtation, with the public transit buses, ] (electrically diven) and ]s being gradually phased out. Marshrutkas provide a good coverage of the smaller residential streets and have routes that are convenient for the residents - although on the busiest routes the buses get increasingly larger. Being more expensive, they are also faster, cleaner and more available, although with an increased frequency of accidents the safety became a concern that has yet to be addressed. It is also quite common for any local with a car to act as a taxi driver now and then, although organized private taxi companies have increased competition dramatically. The ] is also expanding to cover the growing demand. | |||

| {{Main|History of Kyiv}} | |||

| {{For timeline}} | |||

| {{See also|Principality of Kiev|Grand Prince of Kiev}} | |||

| The first known humans in the region of Kyiv lived there in the late ] (]).<ref name=use> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161124133700/http://leksika.com.ua/13290305/ure/kiyiv |date=24 November 2016 }} at ]</ref> The population around Kyiv during the ] formed part of the so-called ], as evidenced by artifacts from that culture found in the area.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161124133700/http://leksika.com.ua/13290305/ure/kiyiv |date=24 November 2016 }} in the ]: "Населення періоду мідного віку на тер. К. було носієм т. з. трипільської культури; відомі й знахідки окремих предметів бронзового віку."</ref> During the early ] certain tribes settled around Kyiv that practiced land cultivation, husbandry and trading with the ] and ancient states of the northern Black Sea coast.<ref name=use/> Findings of Roman coins of the 2nd to the 4th centuries suggest trade relations with the eastern provinces of the ].<ref name=use/> Notable archaeologists of the area around Kyiv include ]. | |||

| ===Founding=== | |||

| <center> | |||

| Scholars continue to debate when the city was founded: The traditional founding date is 482 CE, so the city celebrated ] in 1982. Archaeological data indicates a founding in the sixth or seventh centuries,<ref name="eob">" {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150504135716/https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/317542/Kiev |date=4 May 2015 }}", ]. Retrieved 9 March 2020.</ref><ref>], Glib Ivakin, Yaroslava Vermenych. '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220226013846/http://resource.history.org.ua/cgi-bin/eiu/history.exe?Z21ID=&I21DBN=EIU&P21DBN=EIU&S21STN=1&S21REF=10&S21FMT=eiu_all&C21COM=S&S21CNR=20&S21P01=0&S21P02=0&S21P03=TRN=&S21COLORTERMS=0&S21STR=Kyiv_mst |date=26 February 2022 }}''. Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine.</ref> with some researchers dating the founding as late as the late 9th century.<ref>Rabinovich GA From the history of urban settlements in the eastern Slavs. In the book.: History, culture, folklore and ethnography of the Slavic peoples. M. 1968. 134.</ref> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| Image:Kiev_satellite_2002.jpg|Downtown from satellite. © DigitalGlobe | |||

| Image:Kyiv_mainsquare.jpg|Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) | |||

| Image:Kiev nightview.jpg|Birds-eye view at night. © | |||

| Image:Kiev_Patron_Bridge.jpg|Paton Bridge | |||

| Image:Kiev 9.jpg|Downtown | |||

| Image:Kiev 1.jpg|Streets | |||

| Image:Kiev_dnipro.jpg|View east across ] | |||

| Image:Kiev_lavra.jpg|View over the ] | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| </center> | |||

| ] in the ]]] | |||

| ==History== | |||

| There are several legendary accounts of the origin of the city. One tells of members of a Slavic tribe (]), brothers Kyi (the eldest, after whom the city was named), Shchek, Khoryv, and their sister Lybid, who founded the city (See the '']'').<ref name=use/> Another legend states that ] passed through the area in the 1st century. Where the city is now he erected a cross, where a church later was built. Since the ] an image of ] has represented the city as well as the ]. | |||

| {{see details|History of Kiev}} | |||

| Historically, Kiev is one of the most ancient and important cities of the region, the center of ], survivor of numerous wars, purges and genocides. Many historical and architectural landmarks are preserved or reconstructed in the city, which is thought to have existed as early as the ] A.D. With the exact time of city foundation being hard to determine, ] ] was chosen to celebrate the city's 1,500th anniversary. During the ] and ] centuries Kiev was an outpost of the ] empire. Starting from some point during the late ] or early ] Kiev was ruled by the ] nobility and became the nucleus of the ] polity, which became known as ], times of the ] of Kiev. In ] Kiev was ] of ], an event that had a profound effect on the future of the city and the ]. From ], the area with what was left of the city, became part of the ] and from ] a part of ] (], as a capital of ]). | |||

| ] at Kyiv in 830 during the times of the ]; painting by ] (1853–1928)]] | |||

| In the ] it fell under the ] (later ]), where for some time in remained a provincial town of marginal importance. Town prospered again during the Russian industrial revolution in the late ]. In the turbulent period following the ] Kiev was cought in the middle of several conflicts: the ], the ] and the ]. Amidst these chaotic years, Kiev went through becoming the capital of several ] and from ] the city was part of the ], since ] as a capital of ]. In the ], the city was destroyed again, almost completely, but quickly recovered in the post-war years becoming the third most important city of the Soviet Union, the capital of the second largest ]. It now remains the capital of Ukraine, independent since ] following the ]. | |||

| There is little historical evidence pertaining to the period when the city was founded. Scattered ] settlements existed in the area from the 6th century, but it is unclear whether any of them later developed into the city. On the ] there are several settlements indicated along the mid-stream of ], among which is Azagarium, which some historians believe to be the predecessor to Kyiv.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YWg2ywEACAAJ|title=Римский Киев: или Castrum Azagarium на Киево-Подоле|first=Борис|last=Ерофалов-Пилипчак|date=22 February 2019|publisher=A+C|isbn=9786177765010|via=Google Books|access-date=17 June 2020|archive-date=21 June 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200621175340/https://books.google.com/books/about/%D0%A0%D0%B8%D0%BC%D1%81%D0%BA%D0%B8%D0%B9_%D0%9A%D0%B8%D0%B5%D0%B2.html?id=YWg2ywEACAAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Attractions== | |||

| <!-- table commented out for now <table><tr><td valign=top> --> | |||

| <!-- Separated for readability and an image gallery. Images start after "NEIGBORHOODS" --> | |||

| However, according to the 1773 ''Dictionary of Ancient Geography'' of ], that settlement corresponds to the modern city of ]. Just south of Azagarium, there is another settlement, Amadoca, believed to be the capital of the Amadoci people<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eMUBAAAAYAAJ&dq=Amadoca&pg=PA29|title=The Classical Gazetteer: A Dictionary of Ancient Geography, Sacred and Profane|first=William|last=Hazlitt|date=22 February 1851|publisher=Whittaker|via=Google Books|access-date=17 June 2020|archive-date=4 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200804081050/https://books.google.com/books?id=eMUBAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA29&lpg=PA29&dq=Amadoca&source=bl&ots=IlQ3FheTTw&sig=ACfU3U0CbJwExMEZ01bbTNgNHIofesupoQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiz0fCGkYjqAhU5RDABHRzPB90Q6AEwEHoECAoQAQ#v=onepage&q=Amadoca&f=false|url-status=live}}</ref> living in an area between the marshes of Amadoca in the west and the Amadoca mountains in the east. | |||

| It is said that one can walk from one end of Kiev to the other in the summertime without leaving the shade of its many trees. Most characteristic are the ] trees (Ukrainian: "kashtany"). | |||

| Another name for Kyiv mentioned in history, the origin of which is not completely clear, is Sambat, which apparently has something to do with the ]. The ''Primary Chronicle'' says the residents of Kyiv told ] "there were three brothers Kyi, Shchek, and Khoriv. They founded this town and died, and now we are staying and paying taxes to their relatives the Khazars". In ''De Administrando Imperio'', ] mentions a caravan of small cargo boats which assembled annually, and writes, "They come down the river Dnieper and assemble at the strong-point of Kyiv (Kioava), also called Sambatas".<ref>Sigfús Blöndal. " {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200625114047/https://books.google.com/books?id=vFRug14ui7gC&pg=PA9&lpg=PA9&dq=de+administrando+imperio+Kioava&source=bl&ots=Wnsq6ePXjd&sig=ACfU3U0q7AqEvpTy7StBDeqXxKsRj5Ee3A&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj0ooe3rYjqAhVwQjABHfbIBRsQ6AEwAXoECAkQAQ#v=onepage&q=de%20administrando%20imperio%20Kioava&f=false |date=25 June 2020 }}".</ref> | |||

| Kiev is known as a green city, with ] and numerous large and small parks. Notable among these are the WWII Museum, which offers both indoor and outdoor displays of military history and equipment surrounded by verdant hills overlooking the Dnieper river; the ], located on an island in the river and accessible by metro or by car, in which an amusement park, swimming beaches, and boat rentals can be found; and Victory Park, a popular destination for strollers, joggers, and cyclists. | |||

| At least three Arabic-speaking 10th century geographers who traveled the area mention the city of Zānbat as the chief city of the Russes. Among them are ibn Rustah, ], and an author of the ]. The texts of those authors were discovered by Russian orientalist ]. The etymology of Sambat has been argued by many historians, including ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| Boating, fishing, and water sports are popular pastimes. Since the lakes and rivers freeze over in the winter, ice fishermen are frequently seen, as are children with their ice skates. However, the peak of summer is when masses of people can be seen on the shores, swimming or sunbathing, with daytime high temperatures sometimes reaching 30 to 34 ]. | |||

| The Primary Chronicle states that at some point during the late 9th or early 10th century Askold and Dir, who may have been of Viking or Varangian descent, ruled in Kyiv. They were murdered by ] in 882, but some historians, such as ] and ], dispute that, arguing that Khazar rule continued as late as the 920s, leaving historical documents such as the ] and ]. | |||

| Kiev's noteworthy architecture includes government buildings such as the ] (designed and constructed from ]–], then reconstructed in ]) and the sweeping Ministry of Foreign Affairs building; several Orthodox churches and church complexes such as the ] (Monastery of the Caves), ], ], ], and others such as a ] Lutheran church. | |||

| Other historians suggest that ] ruled the city between 840 and 878, before migrating with some ] tribes to the ]. The Primary Chronicle mentions Hungarians passing near Kyiv. ] was previously known as "]" (Hungarian place).<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200613215705/https://pechersk.kyivcity.gov.ua/content/mennyu-1.html |date=13 June 2020 }}. Pechersk Raion in the Kiev City.</ref> | |||

| The cylindrical Salut hotel, located across from Glory Square and an ] at the ] fallen in the WWII, is one of Kiev's most recognized landmarks. Its windows command views in all directions from one of the highest points in the city. | |||

| According to the aforementioned scholars the building of the fortress of Kyiv was finished in 840 under the leadership of Keő (Keve), Csák, and Geréb, three brothers, possibly members of the ]. The three names appear in the Kyiv Chronicle as Kyi, Shchek, and Khoryv and may be not of Slavic origin, as Russian historians have always struggled to account for their meanings and origins. According to Hungarian historian Viktor Padányi, their names were inserted into the Kyiv Chronicle in the 12th century, and they were identified as old-Russian mythological heroes.<ref>dr. Viktor Padányi – Dentu-Magyaria p. 325, footnote 15</ref> | |||

| Among Kiev's best-known public monuments are the statue of ] astride his horse up the hill from Independence Square and the venerated ], ], overlooking the river above ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Kiev is home to several institutions of higher learning, including the ], the Polytechnic Institute, the ], the Agricultural University, and numerous scientific and technical institutes. | |||

| The city of Kyiv stood on the ]. In 968 the nomadic ] attacked and then ].<ref>{{cite web|url= http://www.geocities.com/egfroth1/Pechenegs |title= The Pechenegs |access-date= 27 October 2009 |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20091027115640/http://www.geocities.com/egfroth1/Pechenegs |archive-date= 27 October 2009|first1= Steven |last1= Lowe |first2= Dmitriy V. |last2= Ryaboy}}</ref> By 1000 CE the city had a population of 45,000.<ref>{{cite book|author1=Paul M. HOHENBERG|author2=Lynn Hollen Lees|author3=Paul M Hohenberg|title=The Making of Urban Europe, 1000–1994|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=-fm0wWa_L80C&pg=PA10|year=2009|publisher=Harvard University Press|isbn=978-0-674-03873-8|page=10|access-date=13 December 2015|archive-date=28 July 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140728201257/http://books.google.com/books?id=-fm0wWa_L80C&pg=PA10|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| In March 1169, Grand Prince ] of ] ], leaving the old town and the prince's hall in ruins.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Plokhy |first=Serhii |year=2006 |title=The Origins of the Slavic Nations |page=42 |url =http://shron.chtyvo.org.ua/Plokhii_Serhii/The_Origins_of_the_Slavic_Nations_Premodern_Identities_in_Russia_Ukraine_and_Belarus__en.pdf |publisher=Cambridge University Press |url-status=dead |archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20170329135435/http://shron.chtyvo.org.ua/Plokhii_Serhii/The_Origins_of_the_Slavic_Nations_Premodern_Identities_in_Russia_Ukraine_and_Belarus__en.pdf |archive-date=29 March 2017|isbn=9780521864039}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Martin |first=Janet L. B. |year=2004 |orig-year=1986 |title=Treasure of the Land of Darkness: The Fur Trade and Its Significance for Medieval Russia |location=Cambridge, England |publisher=Cambridge University Press |page=127 |isbn=9780521548113 |doi=10.1017/CBO9780511523199}}</ref> He took many pieces of religious artwork - including the '']'' icon - from Vyshhorod.<ref>Janet Martin, ''Medieval Russia:980–1584'', (Cambridge University Press, 1996), 100.</ref> In 1203, Prince ] and his ] allies captured and burned Kyiv. In the 1230s, the city was besieged and ravaged several times by different Rus princes. The city had not recovered from these attacks when, in 1240, the ], led by ], completed the ].<ref>, University of Toronto Research Repository</ref> | |||

| Each residential region has its market, or ''rynok''. Here one will find table after table of individuals hawking everything imaginable: vegetables, fresh and smoked meats, fish, cheese, honey, dairy products such as milk and home-made smetana (sour cream), ], cut flowers, housewares, tools and hardware, and clothing. Each of the markets has its own unique mix of products. There is a popular book market by the ] (Ukrainian: Petrivka) metro station. | |||

| These events had a profound effect on the future of the city and on the ]. Before Bogolyubsky's pillaging, Kyiv had had a reputation as one of the largest cities in the world, with a population exceeding 100,000 at the beginning of the 12th century.<ref>{{Cite book|author=Orest Subtelny|title=Ukraine. A History. [Illustr.] (Repr.)|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mRE9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA38|year=1989|publisher=CUP Archive|page=38|access-date=13 December 2015|archive-date=14 June 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614015220/https://books.google.com/books?id=mRE9AAAAIAAJ&pg=PA38|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <center> | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| In the early 1320s, a Lithuanian army led by Grand Duke ] defeated a Slavic army led by ] at the ] and conquered the city. The ], who also claimed Kyiv, retaliated in 1324–1325, so while Kyiv was ruled by a Lithuanian prince, it had to pay tribute to the ]. Finally, as a result of the ] in 1362, ], Grand Duke of Lithuania, incorporated Kyiv and surrounding areas into the ].<ref>Jones, Michael (2000). ''The New Cambridge Medieval History, Volume 6, c.1300–c.1415''. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-521-36290-0}}</ref> In 1482, ] sacked and burned much of Kyiv.<ref>Jerzy Lukowski, W. H. Zawadzki (2006). '' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614032901/https://books.google.com/books?id=HMylRh-wHWEC |date=14 June 2020 }}''. Cambridge University Press. p.53. {{ISBN|0-521-61857-6}}</ref> At the time of the Lithuanian rule, the core of the city was located in ] and there was a Lithuanian {{ill|Kyiv Castle|uk|Київський замок}} with 18 towers on the ] which served as a residence of ], ], and subsequently of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania (e.g. ]).<ref>{{cite web |title="Ukraina: Lietuvos epocha, 1320–1569" |url=https://www.bernardinai.lt/2010-05-03-ukraina-lietuvos-epocha-1320-1569/ |website=] |access-date=10 August 2023 |language=lt |date=3 May 2010 |archive-date=10 August 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230810230336/https://www.bernardinai.lt/2010-05-03-ukraina-lietuvos-epocha-1320-1569/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Хто побудував київський замок? |url=https://we.org.ua/history/hto-pobuduvav-kyyivskyj-zamok/ |website=Про Україну |access-date=22 October 2023 |language=uk |archive-date=1 January 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170101014616/https://we.org.ua/history/hto-pobuduvav-kyyivskyj-zamok/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Image:Kiev_rodina_mat_2001_07_11.jpg|Motherland (Rodina Mat') ] memorial | |||

| Image:Kiev beregynia.jpg|Nightview of the monument to '']'', a protectress of Kiev. © | |||

| ] with the "alten" city shown in ruins ("Rudera")]] | |||

| Image:Kiev_raduga_2001_07_09.jpg|"Rainbow", commemorating the ] | |||

| With the 1569 ], when the ] was established, the Lithuanian-controlled lands of the Kyiv region (], ], and ]) were transferred from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the ], and Kyiv became the capital of ].<ref>Davies, Norman (1982). ''God's Playground: A History of Poland, Vol. 1: The Origins to 1795''. Columbia University Press. {{ISBN|978-0-231-05351-8}}</ref> The 1658 ] envisaged Kyiv becoming the capital of the ] within the ],<ref>Magocsi, Paul Robert (1996). ''A History of Ukraine'', University of Washington Press. {{ISBN|0-295-97580-6}}</ref> but this provision of the treaty never went into operation.<ref>Т.Г. Таирова-Яковлева, Иван Выговский // Единорогъ. Материалы по военной истории Восточной Европы эпохи Средних веков и Раннего Нового времени, вып.1, М., 2009: ''Под влиянием польской общественности и сильного диктата Ватикана сейм в мае 1659 г. принял Гадячский договор в более чем урезанном виде. Идея Княжества Руського вообще была уничтожена, равно как и положение о сохранении союза с Москвой. Отменялась и ликвидация унии, равно как и целый ряд других позитивных статей.''</ref> | |||

| Image:Kiev_gate_2001_07_09.jpg|Golden Gate (Zoloti Vorota) | |||

| Image:Kiev_kashtan.jpg|A kashtan (chestnut) tree | |||

| ===Russian suzerainty=== | |||

| Image:Kiev_warmuseum.JPG|] museum | |||

| Occupied by Russian troops since the 1654 ], Kyiv became a part of the ] from 1667 on the ] and enjoyed a degree of autonomy. None of the Polish-Russian treaties concerning Kyiv have ever been ratified.<ref>], O wschodniej granicy Polski z przed 1772 r., w: Księga Pamiątkowa ku czci Oswalda Balzera, t. II, Lwów 1925, s. .</ref> In the ], Kyiv was a primary ], attracting ]s, and the cradle of many of the empire's most important religious figures, but until the 19th century, the city's commercial importance remained marginal. | |||

| Image:Kiev-BotanicalGarden-1280.jpg|] and ]. © R. Lezhoev | |||

| ] to Kyiv in 1649'' by ] (1865–1937) depicts events after the ] against Polish domination.]] | |||

| In 1834, the Russian government established Saint Vladimir University, now called the ] after the Ukrainian poet ] (1814–1861). (Shevchenko worked as a field researcher and editor for the geography department). The medical faculty of Saint Vladimir University, separated into an independent institution in 1919–1921 during the Soviet period, became the ] in 1995. | |||

| During the 18th and 19th centuries, the ] and ecclesiastical authorities dominated city life;{{citation needed|date=January 2018}} the ] had involvement in a significant part of Kyiv's infrastructure and commercial activity. In the late 1840s the historian, ] (Russian: {{transliteration|ru|Nikolai Kostomarov}}), founded a secret political society, the Brotherhood of ] and Methodius, whose members put forward the idea of a federation of free ] with Ukrainians as a distinct and separate group rather than a subordinate part of the Russian nation; the Russian authorities quickly suppressed the society. | |||

| Following the gradual loss of Ukraine's autonomy, Kyiv experienced growing ] in the 19th century, by means of Russian migration, administrative actions, and social modernization. At the beginning of the 20th century the ] part of the population dominated the city centre, while the ] living on the outskirts retained Ukrainian ] to a significant extent.{{Citation needed|date= April 2011}} However, enthusiasts among ethnic Ukrainian aristocrats, soldiers, and merchants made attempts to preserve the native culture in Kyiv, by clandestine book-printing, amateur theatre, folk studies, etc. | |||

| ] | |||

| During the ] in the late 19th century, Kyiv became an important trade and transportation centre of the Russian Empire, specialising in sugar and grain export by railway and on the ]. By 1900, the city had also become a significant industrial centre, with a population of 250,000. Landmarks of that period include the railway infrastructure, the foundation of numerous educational and cultural facilities, and notable architectural monuments (mostly merchant-oriented). In 1892, the ] of the Russian Empire started running in Kyiv (the third in the world). Kyiv prospered during the late 19th century ] in the Russian Empire, when it became the third most important city of the Empire and the major centre of commerce in its southwest. | |||

| ===Soviet era=== | |||

| In the ] following the ], Kyiv became the capital of several ] and was caught in the middle of several conflicts: ], during which German soldiers occupied it from 2 March 1918 to November 1918, the ] of 1917 to 1922, and the ] of 1919–1921. During the last three months of 1919, Kyiv was intermittently controlled by the ]. Kyiv changed hands sixteen times from the end of 1918 to August 1920.<ref>{{cite book |title= Walking Since Daybreak|url= https://archive.org/details/walkingsincedayb0000ekst|url-access= registration|last= Eksteins|first= Modris|year= 1999|publisher= ]|isbn= 0-618-08231-X|page= }}</ref> | |||

| From 1921 to 1991, the city formed part of the ], which became a founding republic of the ] in 1922. The major events that took place in Soviet Ukraine during the ] all affected Kyiv: the 1920s ] as well as the migration of the rural Ukrainophone population made the ] city Ukrainian-speaking and bolstered the development of ] in the city; the ] that started in the late 1920s turned the city, a former centre of commerce and religion, into a major industrial, technological and scientific centre; the ] devastated the part of the migrant population not registered for ration cards; and ]'s ] of 1937–1938 almost eliminated the city's ]<ref name="Brama">{{cite web |url= http://www.brama.com/ukraine/history/terror/index.html |title= The Great Purge under Stalin 1937–38 |publisher= brama.com |access-date= 14 January 2010 |archive-date= 24 January 2010 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100124123256/http://www.brama.com/ukraine/history/terror/index.html |url-status= live }}</ref><ref name="Figes">] ''The Whisperers: Private Life in Stalin's Russia'', 2007, {{ISBN|0805074619}}, pages 227–315.</ref><ref name="Social Catastrophe">Robert Gellately, ''Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe'' (Knopf, 2007: {{ISBN|1-4000-4005-1}}), 720 pages.</ref> | |||

| In 1934, Kyiv became the capital of Soviet Ukraine. The city boomed again during the years of Soviet industrialization as its population grew rapidly and many industrial giants were established, some of which exist today. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In ], the city again suffered significant damage, and ] occupied it from 19 September 1941 to ]. ] forces killed or captured more than 600,000 Soviet soldiers in the great encircling ] in 1941. Most of those captured never returned alive.<ref>Daniel Goldhagen, ''Hitler's Willing Executioners'' (p. 290) – "2.8 million young, healthy Soviet POWs" killed by the Germans, "mainly by starvation... in less than eight months" of 1941–42, before "the decimation of Soviet POWs... was stopped" and the Germans "began to use them as laborers".</ref> Shortly after the ] occupied the city, a team of ] officers who had remained hidden dynamited most of the buildings on the ], the main street of the city, where German military and civil authorities had occupied most of the buildings; the buildings burned for days and 25,000 people were left homeless. | |||

| Allegedly in response to the actions of the NKVD, the Germans rounded up all the local ] they could find, nearly 34,000,<ref>{{Cite web |title= Babi Yar |website= Jewish Virtual Library |date= 2012 |url= https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/babiyar.html |access-date= 6 July 2014 |archive-date= 17 August 2014 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20140817044645/http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/Holocaust/babiyar.html |url-status= live }}</ref> and massacred them at ] in Kyiv on 29 and 30 September 1941.<ref>Andy Dougan, ''Dynamo: Triumph and Tragedy in Nazi-Occupied Kiev'' (Globe Pequot, 2004: {{ISBN|1-59228-467-1}}), p. 83.</ref> In the months that followed, thousands more were taken to Babi Yar where they were shot. It is estimated that the Germans murdered ] of various ethnic groups, mostly civilians, at Babi Yar during World War II.<ref>{{Cite web|publisher= ]|url= https://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005421|title= Kiev and Babi Yar|website= Holocaust Encyclopedia|access-date= 13 March 2016|archive-date= 23 March 2010|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20100323160622/http://www.ushmm.org/wlc/article.php?lang=en&ModuleId=10005421|url-status= live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Kyiv recovered economically in the post-war years, becoming once again the third-most important city of the Soviet Union. The ] in 1986 occurred only {{convert|100|km|mi|abbr=on}} north of the city. However, the prevailing south wind blew most of the radioactive debris away from Kyiv. | |||

| ===Independence=== | |||

| In the course of the ] the ] proclaimed the ] in the city on 24 August 1991. In 2004–2005, the city played host to the largest post-Soviet public demonstrations up to that time, in support of the ]. From November 2013 until February 2014, central Kyiv became the primary location of ]. During the onset of the ] in February 2022, ] attempted to ] but were ] by ] on the outskirts of the city; Kyiv itself escaped major damage. Following the Russian retreat from the region in April 2022, Kyiv has been subject to frequent ]. | |||

| ==Environment== | |||

| {{see also|Kyiv Mountains}} | |||

| ===Geography=== | |||

| ] ] image of Kyiv and the ]]] | |||

| Geographically, Kyiv is on the border of the ] woodland ecological zone, a part of the European mixed woods area, and the East European ] ]. However, the city's unique landscape distinguishes it from the surrounding region. Kyiv is completely surrounded by ]. | |||

| Originally on the west bank, today Kyiv is on both sides of the ], which flows southwards through the city towards the ]. The older and higher western part of the city sits on numerous wooded hills (]), with ravines and small rivers. Kyiv's geographical relief contributed to its ]s, such as ''Podil'' ("lower"), ''Pechersk'' ("caves"), and ''uzviz'' (a steep street, "descent"). Kyiv is a part of the larger ] adjoining the western bank of the Dnieper in its mid-flow, and which contributes to the city's elevation change. | |||

| The northern outskirts of the city border the ]. Kyiv expanded into the ] on the left bank (''to the east'') as late as the 20th century. The whole portion of Kyiv on the left bank of the Dnieper is generally referred to as the ''Left Bank'' ({{lang|uk|Лівий берег}}, ''Livyi bereh''). Significant areas of the left bank Dnieper valley were artificially sand-deposited, and are protected by dams. | |||

| Within the city the Dnieper River forms a branching system of ], isles, and harbors within the city limits. The city is close to the mouth of the ] and the ] in the north, and the ] in the south. Both the Dnieper and Desna rivers are ] at Kyiv, although regulated by the reservoir shipping locks and limited by winter freeze-over. | |||

| In total, there are 448 bodies of open water within the boundaries of Kyiv, which include the Dnieper itself, its reservoirs, and several small rivers, dozens of lakes and artificially created ponds. They occupy 7949 hectares. Additionally, the city has 16 developed beaches (totalling 140 hectares) and 35 near-water recreational areas (covering more than 1,000 hectares). Many are used for pleasure and recreation, although some of the bodies of water are not suitable for swimming.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://kyivcity.gov.ua/news/u_kiyevi_bilya_vodoym_vidkrito_32_zoni_dlya_vidpochinku_z_yakikh_12__iz_mozhlivistyu_kupannya/ |website=kyivcity.gov.ua |title=У Києві біля водойм відкрито 32 зони для відпочинку, з яких 12 – із можливістю купання |language=uk |date=19 June 2020 |access-date=12 October 2020 |archive-date=9 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200809002809/https://kyivcity.gov.ua/news/u_kiyevi_bilya_vodoym_vidkrito_32_zoni_dlya_vidpochinku_z_yakikh_12__iz_mozhlivistyu_kupannya/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2020/06/19/7256376/ |website=pravda.com.ua |title=У Кличка розповіли, де в Києві можна купатися, а де тільки засмагати. Список |language=uk |date=19 June 2020 |access-date=12 October 2020 |archive-date=24 June 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200624083402/https://www.pravda.com.ua/news/2020/06/19/7256376/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| According to the ] 2011 evaluation, there were no risks of ]s in Kyiv and ].<ref name="UN Urban agglomerations types of natural risks">{{cite web|url=http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/CD-ROM/WUP2011-F23-City_Risk_Natural-Disasters.xls |title=Urban agglomerations with 750,000 inhabitants or more in 2011 and types of natural risks |publisher=United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division |date=April 2012 |access-date=1 September 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141006152606/http://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/CD-ROM/WUP2011-F23-City_Risk_Natural-Disasters.xls |archive-date=6 October 2014 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Climate=== | |||

| Kyiv has a warm-summer ] ] (] ''Dfb'').<ref>{{cite journal| last =Kottek| first =M.| author2 =J. Grieser| author3 =C. Beck| author4 =B. Rudolf| author5 =F. Rubel| title =World Map of the Köppen-Geiger climate classification updated| journal =Meteorol. Z.| volume =15| pages =259–263| url =http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/pdf/kottek_et_al_2006_A4.pdf| doi =10.1127/0941-2948/2006/0130| year =2006| issue =3| bibcode =2006MetZe..15..259K| access-date =24 August 2012| archive-date =5 March 2012| archive-url =https://web.archive.org/web/20120305153610/http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/pdf/kottek_et_al_2006_A4.pdf| url-status =live |issn=0941-2948}}</ref> The warmest months are June, July, and August, with mean temperatures of {{convert|13.8|to|24.8|C|F}}. The coldest are December, January, and February, with mean temperatures of {{convert|-4.6|to|-1.1|C|F}}. The highest ever temperature recorded in the city was {{convert|39.4|°C|°F|abbr=on}} on 30 July 1936.<ref name=extremes1>{{cite web |url=http://cgo-sreznevskyi.kyiv.ua/index.php?lang=en&fn=k_klimat&f=kyiv |title=ЦГО Кліматичні дані по м.Києву |website=cgo-sreznevskyi.kyiv.ua |publisher=Central Observatory for Geophysics |language=uk |access-date=12 October 2020 |archive-date=18 April 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200418123950/http://cgo-sreznevskyi.kyiv.ua/index.php?lang=en&fn=k_klimat&f=kyiv |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name=extremes2>{{cite web |url=http://cgo-sreznevskyi.kyiv.ua/index.php?dv=klimat-rekords/ |title=ЦГО Кліматичні рекорди |website=cgo-sreznevskyi.kyiv.ua |publisher=Central Observatory for Geophysics |language=uk |access-date=12 October 2020 |archive-date=31 March 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200331222524/http://cgo-sreznevskyi.kyiv.ua/index.php?dv=klimat-rekords%2F |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The coldest temperature ever recorded in the city was {{convert|-32.9|°C|°F|abbr=on}} on 11 January 1951.<ref name=extremes1/><ref name=extremes2/> Snow cover usually lies from mid-November to the end of March, with the frost-free period lasting 180 days on average, but surpassing 200 days in some years.<ref name="eob" /> | |||

| {{Weather box | |||

| | location = Kyiv (1991–2020, extremes 1881–present) | |||

| | metric first = Yes | |||

| | single line = Yes | |||

| | width = auto | |||

| | collapsed = Yes | |||

| | Jan record high C = 13.2 | |||

| | Feb record high C = 17.3 | |||

| | Mar record high C = 25.3 | |||

| | Apr record high C = 30.2 | |||

| | May record high C = 33.6 | |||

| | Jun record high C = 35.5 | |||

| | Jul record high C = 39.4 | |||

| | Aug record high C = 39.3 | |||

| | Sep record high C = 35.7 | |||

| | Oct record high C = 27.9 | |||

| | Nov record high C = 23.2 | |||

| | Dec record high C = 15.2 | |||

| | year record high C = 39.4 | |||

| | Jan high C = -0.8 | |||

| | Feb high C = 0.7 | |||

| | Mar high C = 6.5 | |||

| | Apr high C = 15.0 | |||

| | May high C = 21.1 | |||

| | Jun high C = 24.6 | |||

| | Jul high C = 26.5 | |||

| | Aug high C = 25.9 | |||

| | Sep high C = 20.0 | |||

| | Oct high C = 12.9 | |||

| | Nov high C = 5.3 | |||

| | Dec high C = 0.5 | |||

| | year high C = 13.2 | |||

| | Jan mean C = −3.2 | |||

| | Feb mean C = −2.3 | |||

| | Mar mean C = 2.5 | |||

| | Apr mean C = 10.0 | |||

| | May mean C = 15.8 | |||

| | Jun mean C = 19.5 | |||

| | Jul mean C = 21.3 | |||

| | Aug mean C = 20.5 | |||

| | Sep mean C = 14.9 | |||

| | Oct mean C = 8.6 | |||

| | Nov mean C = 2.6 | |||

| | Dec mean C = -1.8 | |||

| | year mean C = 9.0 | |||

| | Jan low C = -5.5 | |||

| | Feb low C = -5.0 | |||

| | Mar low C = -0.8 | |||

| | Apr low C = 5.7 | |||

| | May low C = 10.9 | |||

| | Jun low C = 14.8 | |||

| | Jul low C = 16.7 | |||

| | Aug low C = 15.7 | |||

| | Sep low C = 10.6 | |||

| | Oct low C = 5.1 | |||

| | Nov low C = 0.4 | |||

| | Dec low C = -3.9 | |||

| | year low C = 5.4 | |||

| | Jan record low C = -31.1 | |||

| | Feb record low C = -32.2 | |||

| | Mar record low C = -24.9 | |||

| | Apr record low C = -10.4 | |||

| | May record low C = -2.4 | |||

| | Jun record low C = 2.5 | |||

| | Jul record low C = 5.8 | |||

| | Aug record low C = 3.3 | |||

| | Sep record low C = -2.9 | |||

| | Oct record low C = -17.8 | |||

| | Nov record low C = -21.9 | |||

| | Dec record low C = -30.0 | |||

| | year record low C = -32.2 | |||

| | precipitation colour = green | |||

| | Jan precipitation mm = 38 | |||

| | Feb precipitation mm = 40 | |||

| | Mar precipitation mm = 40 | |||

| | Apr precipitation mm = 42 | |||

| | May precipitation mm = 65 | |||

| | Jun precipitation mm = 73 | |||

| | Jul precipitation mm = 68 | |||

| | Aug precipitation mm = 56 | |||

| | Sep precipitation mm = 57 | |||

| | Oct precipitation mm = 46 | |||

| | Nov precipitation mm = 46 | |||

| | Dec precipitation mm = 47 | |||

| | year precipitation mm = 618 | |||

| | Jan snow depth cm = 9 | |||

| | Feb snow depth cm = 11 | |||

| | Mar snow depth cm = 7 | |||

| | Apr snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | May snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | Jun snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | Jul snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | Aug snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | Sep snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | Oct snow depth cm = 0 | |||

| | Nov snow depth cm = 2 | |||

| | Dec snow depth cm = 5 | |||

| | year snow depth cm = | |||

| | Jan rain days = 8 | |||

| | Feb rain days = 7 | |||

| | Mar rain days = 9 | |||

| | Apr rain days = 13 | |||

| | May rain days = 14 | |||

| | Jun rain days = 15 | |||

| | Jul rain days = 14 | |||

| | Aug rain days = 11 | |||

| | Sep rain days = 14 | |||

| | Oct rain days = 12 | |||

| | Nov rain days = 12 | |||

| | Dec rain days = 9 | |||

| | year rain days = 138 | |||

| | Jan snow days = 17 | |||

| | Feb snow days = 17 | |||

| | Mar snow days = 10 | |||

| | Apr snow days = 2 | |||

| | May snow days = 0.2 | |||

| | Jun snow days = 0 | |||

| | Jul snow days = 0 | |||

| | Aug snow days = 0 | |||

| | Sep snow days = 0.03 | |||

| | Oct snow days = 2 | |||

| | Nov snow days = 9 | |||

| | Dec snow days = 16 | |||

| | year snow days = 73 | |||

| | Jan humidity = 82.7 | |||

| | Feb humidity = 80.1 | |||

| | Mar humidity = 74.0 | |||

| | Apr humidity = 64.3 | |||

| | May humidity = 62.0 | |||

| | Jun humidity = 67.5 | |||

| | Jul humidity = 68.3 | |||

| | Aug humidity = 66.9 | |||

| | Sep humidity = 73.5 | |||

| | Oct humidity = 77.4 | |||

| | Nov humidity = 84.6 | |||

| | Dec humidity = 85.6 | |||

| | year humidity = 73.9 | |||

| | Jan sun = 42 | |||

| | Feb sun = 64 | |||

| | Mar sun = 112 | |||

| | Apr sun = 162 | |||

| | May sun = 257 | |||

| | Jun sun = 273 | |||

| | Jul sun = 287 | |||

| | Aug sun = 252 | |||

| | Sep sun = 189 | |||

| | Oct sun = 123 | |||

| | Nov sun = 51 | |||

| | Dec sun = 31 | |||

| | year sun = | |||

| | Jan uv = 1 | |||

| | Feb uv = 1 | |||

| | Mar uv = 2 | |||

| | Apr uv = 4 | |||

| | May uv = 6 | |||

| | Jun uv = 7 | |||

| | Jul uv = 6 | |||

| | Aug uv = 6 | |||

| | Sep uv = 4 | |||

| | Oct uv = 2 | |||

| | Nov uv = 1 | |||

| | Dec uv = 1 | |||

| | source 1 = Pogoda.ru.net,<ref name="pogoda kyiv">{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20191213141910/http://www.pogodaiklimat.ru/climate/33345.htm | |||

| | archive-date = 13 December 2019 | |||

| | url = http://www.pogodaiklimat.ru/climate/33345.htm | |||

| | title = Weather and Climate – The Climate of Kyiv | |||

| | publisher = Weather and Climate (Погода и климат) | |||

| | access-date = 8 November 2021 | |||

| | language = ru}}</ref> Central Observatory for Geophysics (extremes),<ref name=extremes1/><ref name=extremes2/> ] (humidity 1981–2010)<ref name=WMOCLINOkyiv>{{cite web | |||

| | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20210717143555/https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/normals/WMO/1981-2010/RA-VI/Ukraine/12.6.%20WMO_Normals_Excel_Template%20%282%29.xls | |||

| | archive-date = 17 July 2021 | |||

| | archive-format = XLS | |||

| | format = XLS | |||

| | url = https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/pub/data/normals/WMO/1981-2010/RA-VI/Ukraine/12.6.%20WMO_Normals_Excel_Template%20(2).xls | |||

| | title = World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1981–2010 | |||

| | publisher = ] | |||

| | access-date = 17 July 2021}}</ref> | |||

| | source 2 = ] (sun, 1931–1960)<ref name=KyivDMI>{{cite web | last1 = Cappelen | first1 = John | last2 = Jensen | first2 = Jens | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20130427173827/http://www.dmi.dk/dmi/tr01-17.pdf | archive-date=27 April 2013| url = http://www.dmi.dk/dmi/tr01-17.pdf | work = Climate Data for Selected Stations (1931–1960) | title = Ukraine – Kyiv | page = 332 | publisher = Danish Meteorological Institute | language = da | access-date = 1 April 2016}}</ref> and Weather Atlas<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/ukraine/kiev-climate|title=Kiev, Ukraine – Detailed climate information and monthly weather forecast|publisher=Yu Media Group|website=Weather Atlas|language=en|access-date=3 July 2019|archive-date=3 July 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190703190237/https://www.weather-atlas.com/en/ukraine/kiev-climate|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| | date = August 2010 | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Legal status, local government and politics== | |||

| === Legal status and local government === | |||

| {{Main|Legal status and local government of Kyiv}} | |||

| The municipality of the city of Kyiv has a ] within Ukraine compared to the other ]. The most significant difference is that the city is considered as a region of Ukraine (see ]). It is the only city that has double jurisdiction. The Head of ] – the city's governor – is appointed by the ], while the Head of the City Council – the ] – is elected by local popular vote. | |||

| The mayor of Kyiv is ], who was sworn in on 5 June 2014,<ref name=KKMs5614> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201111202603/https://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/208052.html |date=11 November 2020 }}, ] (5 June 2014)</ref> after he had won the ] with almost 57% of the votes.<ref name="votecountKMEIU4614"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200907181110/https://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/207829.html |date=7 September 2020 }}, ] (4 June 2014)</ref> Since 25 June 2014, Klitschko is also ].<ref name="Poroshenko appoints Klitschko head of Kyiv city administration - decree"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140704081010/http://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/210904.html |date=4 July 2014 }}, ] (25 June 2014)<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140714210807/http://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/210980.html |date=14 July 2014 }}, ] (25 June 2014)</ref> Klitschko was last reelected in the ] with 50.52% of the votes, in the first round of the election.<ref name="3131537KlitschkoRE"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201106152400/https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-elections/3131537-vitali-klitschko-wins-in-first-round-of-kyiv-mayor-election.html |date=6 November 2020 }}, ] (6 November 2020)</ref> | |||

| Most key buildings of the national government are along ] (''vulytsia Mykhaila Hrushevskoho'') and Institute Street (''vulytsia Instytutska''). Hrushevskoho Street is named after the Ukrainian academician, politician, historian, and statesman ], who wrote an academic book titled: "Bar Starostvo: Historical Notes: XV–XVIII" about the history of ].<ref>Hrushevsky, M., Bar Starostvo: Historical Notes: XV–XVIII, St. Vladimir University Publishing House, Bol'shaya-Vasil'kovskaya, Building no. 29–31, Kiev, Ukraine, 1894; Lviv, Ukraine, {{ISBN|5-12-004335-6}}, pp. 1–623, 1996.</ref> That portion of the city is also unofficially known as the government quarter ({{lang|uk|урядовий квартал}}). | |||

| The city state administration and council is in the Kyiv City council building on Khreshchatyk Street. The oblast state administration and council is in the oblast council building on ''ploshcha Lesi Ukrainky'' ("Lesya Ukrainka Square"). | |||

| {{Gallery|title=Government buildings in Kyiv|width=170|height=120|align=center | |||

| ||The ]. | |||

| | File:Київ, Будинок уряду України.jpg|The seat of the ] | |||

| | File:Pres-adm-ukraine-2008.jpg|The presidential administration building | |||

| | File:Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Ukraine.JPG|The ] | |||

| | File:Крещатик, 36 (01) - Мэрия.jpg|The seat of Kyiv City State and ] on Khreshchatyk Street | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Politics=== | |||

| {{main|2020 Kyiv local election}} | |||

| {{expand section|date=August 2013}} | |||

| The growing political and economic role of the city, combined with its international relations, as well as extensive ],<ref name="Siumar on Kyiv">{{cite news | url=http://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2012/05/22/6964965/ | title=Київ: стратегічна позиція чи "чемодан" без ручки? | date=22 May 2012 | agency=] | access-date=19 August 2013 | author=Сюмар, Вікторія | archive-date=1 May 2014 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140501135627/http://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2012/05/22/6964965/ | url-status=live }}</ref> have made Kyiv the most pro-Western and pro-democracy region of Ukraine; (so called) ] ] advocating tighter ] receive most votes during ] in Kyiv.<ref name="radiosvoboda.org">{{Cite news|url=https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/24756059.html|title=Виборчі комісії фіксують перемогу опозиційних кандидатів у Києві|newspaper=Радіо Свобода|date=31 October 2012 |access-date=22 February 2022|archive-date=22 February 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220222143446/https://www.radiosvoboda.org/a/24756059.html|url-status=live |last1=Свобода |first1=Радіо }}</ref><ref name="Битва за Київ">{{cite news | url=http://kontrakty.ua/article/59790 | script-title=uk:Битва за Київ: чому посада мера вже не потрібна Кличку і чи будуть вибори взагалі | date=19 March 2013 | agency=Kontrakty | access-date=19 August 2013 | language=uk | archive-date=24 August 2013 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130824001327/http://kontrakty.ua/article/59790 | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="Nebozhenko">{{cite web | url=http://gazeta.ua/articles/politics/_u-kozhnogo-kiyanina-v-golovi-dosvid-majdanu-i-ce-golovnij-bil-vsih-predstavnikiv/493982 | script-title=uk:У кожного киянина в голові – досвід Майдану | date=20 April 2013 | access-date=19 August 2013 | language=uk | archive-date=5 March 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220305145530/https://gazeta.ua/articles/politics/_u-kozhnogo-kiyanina-v-golovi-dosvid-majdanu-i-ce-golovnij-bil-vsih-predstavnikiv-vladi-ekspert/493982 | url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="pravda1629">{{in lang|uk}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121229195207/http://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2012/10/29/6975859/|date=29 December 2012}} by ]<br />{{in lang|uk}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101203204641/http://www.cvk.gov.ua/|date=3 December 2010}}, ]<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614003027/https://books.google.com/books?id=2UoQ-ueHjdEC&pg=PA1629|date=14 June 2020}}, ], 2008, {{ISBN|1851099077}} (page 1629)<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200614021111/https://books.google.com/books?id=cQqr7f9QkngC&pg=PA122|date=14 June 2020}} by Andrej Lushnycky and ], ], 2009, {{ISBN|303911607X}} (page 122)<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130317180048/http://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/eastweek/2012-11-07/after-parliamentary-elections-ukraine-a-tough-victory-party-regions|date=17 March 2013}}, ] (7 November 2012)<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200806095344/https://books.google.com/books?id=H23Pv4Ik3vMC&pg=PA396|date=6 August 2020}} by ] and Patrick Moreau, ], 2008, {{ISBN|978-3-525-36912-8}} (page 396)<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131031065126/http://en.interfax.com.ua/news/general/126937.html#.UUzMyKnCus0|date=31 October 2013}}, ] (12 November 2012)<br />, ] (8 January 2013)<br />{{in lang|uk}} {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131203020408/http://www.ucipr.kiev.ua/publications/electronic-bulletin-your-choice-2012-issue-4-batkivshchyna/lang/en|date=3 December 2013}}, Ukrainian Center for Independent Political Research (24 October 2012)<br /> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140202121637/http://www.geopolitika.lt/?artc=4429|date=2 February 2014}} by ], Centre for Geopolitical Studies (1 May 2011)<br />{{cite web |title=Вибори-2012. Результати голосування |trans-title= |url=http://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2012/10/29/6975859/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130825040209/http://www.pravda.com.ua/articles/2012/10/29/6975859/ |archive-date=25 August 2013 |access-date=18 August 2013 |language=Ukrainian}}</ref> In a poll conducted by the ] in the first half of February 2014, 5.3% of those polled in Kyiv believed "Ukraine and Russia must unite into a single state", nationwide this percentage was 12.5.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171223055352/http://www.kiis.com.ua/?lang=eng&cat=reports&id=236&page=1 |date=23 December 2017 }}, ] (4 March 2014)</ref> | |||

| ===Subdivisions=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{See also|Category:Neighborhoods in Kyiv}} | |||

| {{Main|Subdivisions of Kyiv}} | |||

| ====Traditional subdivision==== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The ] naturally divides Kyiv into the Right Bank and the Left Bank areas. Historically on the western right bank of the river, the city expanded into the left bank only in the 20th century. Most of Kyiv's attractions as well as the majority of business and governmental institutions are on the right bank. The eastern "Left Bank" is predominantly residential. There are large industrial and green areas in both the Right Bank and the Left Bank. | |||

| Kyiv is further informally divided into historical or territorial neighbourhoods, each housing from about 5,000 to 100,000 inhabitants. | |||

| {{Panorama | |||

| |image=File:Панорама Правого берега.jpg | |||

| |fullwidth=14570 | |||

| |fullheight=2000 | |||

| |caption={{center|A ] view of Right-Bank Kyiv, where the city centre is located (May 2011)}} | |||

| |alt= | |||

| |height=210 | |||

| }} | |||

| ====Formal subdivision==== | |||

| ]: {{unbulleted list | |||

| |Г – ] | |||

| |О – ] | |||

| |Печ – ] | |||

| |Под – ] | |||

| |Ш – ] | |||

| |Св – ] | |||

| |Сол – ] | |||

| |Дар – ] | |||

| |Дес – ] | |||

| |Дн – ] | |||

| }}]] | |||

| The first known formal subdivision of Kyiv dates to 1810 when the city was subdivided into 4 parts: ], Starokyiv, and the first and the second parts of ]. In 1833–1834 according to ] ]'s decree, Kyiv was subdivided into 6 police ]s (]); later being increased to 10. In 1917, there were 8 Raion Councils (''Duma''), which were reorganised by ]s into 6 Party-Territory Raions. | |||

| During the Soviet era, as the city was expanding, the number of raions also gradually increased. These newer districts of the city, along with some older areas were then named in honour of prominent communists and socialist-revolutionary figures; however, due to the way in which many communist party members eventually, after a certain period of time, fell out of favour and so were replaced with new, fresher minds, so too did the names of Kyiv's districts change accordingly. | |||

| The last district reform took place in 2001 when the number of districts was decreased from 14 to 10. | |||

| Under ] (mayor from 1999 to 2006), there were further plans for the merger of some districts and revision of their boundaries, and the total number of districts had been planned to be decreased from 10 to 7. With the election of the new mayor-elect (]) in 2006, these plans were shelved. | |||

| Each district has its own ] with jurisdiction over a limited scope of affairs.<ref name="796003Kyivdistrictcouncils">{{in lang|uk}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220203180827/https://interfax.com.ua/news/general/796003.html |date=3 February 2022 }}, ] (3 February 2022)</ref> | |||

| ==Demographics== | |||

| {{Update|section|date=February 2023}} | |||

| {{See also|Kyiv metropolitan area}} | |||

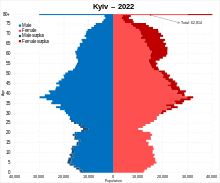

| ] | |||

| According to the official ] statistics, there were 2,847,200 residents within the city limits of Kyiv in July 2013.<ref name="Kiev statistical report">{{cite web | url=http://kyiv.ukrstat.gov.ua/p.php3?c=527 | script-title=uk:Чисельність населення м.Києва | trans-title=Population of Kyiv city | publisher=UkrStat.gov.ua | language=uk | date=1 November 2015 | access-date=9 January 2016 | archive-date=9 October 2020 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201009112619/http://kyiv.ukrstat.gov.ua/p.php3?c=527 | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Historical population=== | |||

| {{Historical populations | |||

| |shading=on | |||

| |10xx|100000 | |||

| |1647|15000 | |||

| |1666|10000 | |||

| |1763|42000 | |||

| |1797|19000 | |||

| |1835|36500 | |||

| |1845|50000 | |||

| |1856|56000 | |||

| |1865|71300 | |||

| |1874|127500 | |||

| |1884|154500 | |||

| |1897|247700 | |||

| |1905|450000 | |||

| |1909|468000 | |||

| |1912|442000 | |||

| |1914|626300 | |||

| |1917|430500 | |||

| |1919|544000 | |||

| |1922|366000 | |||

| |1923|413000 | |||

| |1926|513000 | |||

| |1930|578000 | |||

| |1940|930000 | |||

| |1943|180000 | |||

| |1956|991000 | |||