| Revision as of 13:53, 8 July 2008 edit79.74.121.54 (talk) ←Redirected page to Eddie Murphy← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:37, 18 December 2024 edit undoAlfa-ketosav (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users2,277 edits →History and classification | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Genus of Protozoa}} | |||

| #REDIRECT ] | |||

| {{About|the ] Amoeba|other uses|Amoeba (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{automatic taxobox | |||

| | image = Amoeba proteus with many pseudopodia.jpg | |||

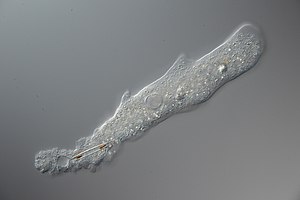

| | image_caption = ''Amoeba proteus'' | |||

| | taxon = Amoeba | |||

| | authority = ], 1822<ref>Bory de Saint-Vincent, J.B.G.M. (1822-1831). Article "Amiba". In: ''Dictionnaire classique d'histoire naturelle par Messieurs Audouin, Isid. Bourdon, Ad. Brongniart, De Candolle, Daudebard de Férusac, A. Desmoulins, Drapiez, Edwards, Flourens, Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, A. De Jussieu, Kunth, G. de Lafosse, Lamouroux, Latreille, Lucas fils, Presle-Duplessis, C. Prévost, A. Richard, Thiébaut de Berneaud, et Bory de Saint-Vincent. Ouvrage dirigé par ce dernier collaborateur, et dans lequel on a ajouté, pour le porter au niveau de la science, un grand nombre de mots qui n'avaient pu faire partie de la plupart des Dictionnaires antérieurs''. 17 vols. Paris: Rey et Gravier; Baudoin frères, vol. 1, p. 260, .</ref> | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Species | |||

| | subdivision = | |||

| * ''Amoeba agilis'' <small>Kirk, 1907</small> | |||

| * ''Amoeba gorgonia'' <small>Pen.</small> | |||

| * ''Amoeba limicola'' <small>Rhumb.</small> | |||

| * '']'' <small>Pal.</small> | |||

| * ''Amoeba vespertilio'' <small>Pen.</small> | |||

| | synonyms = | |||

| * ''Proteus'' <small>Mueller 1786 non Hauser 1885 non Roesel 1755 non Dujardin 1835 non Laurenti 1768</small> | |||

| * ''Vibrio'' <small>Gmelin 1788 non Pacini 1854</small> | |||

| * ''Metamoeba'' <small>Friz, 1992</small> | |||

| }} | |||

| '''''Amoeba''''' is a ] of ] ]s in the family ].<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.nies.go.jp/chiiki1/protoz/morpho/flagella/amoeba.htm|title = National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan|date = 2007|access-date = Sep 11, 2014|website = The World of Protozoa, Rotifera, Nematoda and Oligochaeta|publisher = National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan|last = Xu|first = Kaigin}}</ref> The ] of the genus is '']'', a common freshwater organism, widely studied in classrooms and laboratories.<ref>{{Cite journal|title = Taxonomic Analyses of Seven Species of Family Amoebidae by Isozymic Characterization of Electrophoretic Patterns and the Descriptions of a New Genus and a New Species: Metamoeba n. gen. Amoeba amazonas n. sp|last = Friz|first = Carl T.|date = 1992|journal = Archiv für Protistenkunde|volume = 142|issue = 1–2|pages = 29–40|doi = 10.1016/S0003-9365(11)80098-9}}</ref> | |||

| ==History and classification== | |||

| ] | |||

| The earliest record of an organism resembling ''Amoeba'' was produced in 1755 by ], who named his discovery "''der kleine Proteus''" ("the little Proteus"), after ], the shape-shifting sea-god of Greek Mythology.<ref>Rösel von Rosenhof, A.J. 1755. Der monatlich-herausgege | |||

| benen Insecten-Belustigung erster Theil... J.J. Fleischmann: Nürnberg. Vol. 3, Tab. 101, , , p. 622, .</ref> While Rösel's illustrations show a creature similar in appearance to the one now known as ''Amoeba proteus, ''his "little Proteus<nowiki>''</nowiki> cannot be identified confidently with any modern species.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Biology of Amoeba|last = Jeon|first = Kwang W.|publisher = Academic Press|year = 1973|location = New York|pages = 2–3}}</ref> | |||

| The term "Proteus ]" remained in use throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as an informal name for any large, free-living amoeboid.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Biological atlas: a guide to the practical study of plants and animals|last = McAlpine|first = Daniel|publisher = W. & A. K. Johnston|year = 1881|location = Edinburgh and London|pages = 17}}</ref> | |||

| In 1758, apparently without seeing Rösel's "Proteus" for himself, ] included the organism in his own system of classification, under the name ''Volvox chaos''. However, because the name '']'' had already been applied to a genus of flagellate algae, he later changed the name to '']''. In 1786, the Danish Naturalist ] described and illustrated a species he called ''Proteus diffluens'', which was probably the organism known today as ''Amoeba proteus.''<ref>{{Cite book|title = Biology of Amoeba|last = Jeon|first = Kwang W.|publisher = Academic Press|year = 1973|location = New York|page = 5}}</ref> | |||

| The genus ''Amiba, ''from the Greek ''amoibè'' (ἀμοιβή), meaning "change", was erected in 1822 by ].<ref>Bory de Saint-Vincent, J. B. G. M. "Essai d'une classification des animaux microscopiques." Agasse, Paris (1826).p. 28</ref><ref name="EOS1">{{cite book | editor1-first = Kimberley | editor1-last = McGrath | editor2-last = Blachford | editor2-first = Stacey | title = Gale Encyclopedia of Science Vol. 1: Aardvark-Catalyst | edition = 2nd | year = 2001 | isbn = 978-0-7876-4370-6 | publisher = Gale Group | oclc = 46337140 | url-access = registration | url = https://archive.org/details/galeencyclopedia0000mcgr }}</ref> In 1830, the German naturalist ] adopted this genus in his own classification of microscopic creatures, but changed the spelling to "''Amoeba''."<ref>Ehrenberg, Christian Gottfried. Organisation, systematik und geographisches verhältniss der infusionsthierchen: Zwei vorträge, in der Akademie der wissenschaften zu Berlin gehalten in den jahren 1828 und 1830. Druckerei der Königlichen akademie der wissenschaften, 1832. p. 59</ref> | |||

| ==Anatomy, feeding and reproduction== | |||

| ] | |||

| Species of ''Amoeba'' move and feed by extending temporary structures called ]. These are formed by the coordinated action of ] within the cellular ] pushing out the ] which surrounds the cell.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Molecular Biology of the Cell 5th Edition|last = Alberts Eds.|publisher = Garland Science|year = 2007|isbn = 9780815341055|location = New York|pages = 1037|display-authors=etal}}</ref> In ''Amoeba'', the pseudopodia are approximately tubular, and rounded at the ends (lobose). The cell's overall shape may change rapidly as pseudopodia are extended and retracted into the cell body. An ''Amoeba'' may produce many pseudopodia at once, especially when freely floating. When crawling rapidly along a surface, the cell may take a roughly monopodial form, with a single dominant pseudopod deployed in the direction of movement.<ref>{{Cite web|url = http://www.arcella.nl/amoeba|title = Amoeba|access-date = Sep 11, 2014|website = Microworld: World of Amoeboid Organisms|publisher = Ferry Siemensma|last = Siemensma|first = Ferry}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Historically, researchers have divided the ] into two parts, consisting of a granular inner ] and an outer layer of clear ], both enclosed within a flexible ].<ref>{{Cite book|title = Biology of Amoeba|last = Jeon|first = Kwang W.|publisher = Academic Press|year = 1973|location = New York|pages = 102}}</ref> The cell usually has a single granular ], containing most of the organism's ] . A ] is used to maintain ] by excreting excess water from the cell (see ]). | |||

| An ''Amoeba'' obtains its food by ], engulfing smaller organisms and particles of organic matter, or by ], taking in dissolved nutrients through ] formed within the cell membrane.<ref>{{Cite book|title = Biology of Amoeba|last = Jeon|first = Kwang W.|publisher = Academic Press|year = 1973|location = New York|pages = 100}}</ref> Food enveloped by the ''Amoeba'' is stored in digestive organelles called ]. | |||

| ''Amoeba'', like other unicellular ] organisms, reproduces asexually by ] and ]. ] have not been directly observed in ''Amoeba'', although sexual exchange of genetic material is known to occur in other ] groups.<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors =Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E |title=The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms |journal=Proc. Biol. Sci. |volume=278 |issue=1715 |pages=2083–6|date=July 2011 |pmid=21429931 |pmc=3107637 |doi=10.1098/rspb.2011.0289 }}</ref> Most ]ns appear capable of performing syngamy, ] and ] reduction through a standard ].<ref name="pmid30380054">{{cite journal |vauthors=Hofstatter PG, Brown MW, ((Lahr DJG)) |title=Comparative Genomics Supports Sex and Meiosis in Diverse Amoebozoa |journal=Genome Biol Evol |volume=10 |issue=11 |pages=3118–3128 |date=November 2018 |pmid=30380054 |pmc=6263441 |doi=10.1093/gbe/evy241 }}</ref> The “asexual” model organism '']'' has most of the proteins associated with ].<ref name="pmid30380054" /> In cases where organisms are forcibly divided, the portion that retains the nucleus will often survive and form a new cell and cytoplasm, while the other portion dies.<ref name="SC">{{cite web | url = http://www.scienceclarified.com/Al-As/Amoeba.html | publisher = Scienceclarified.com | title = Amoeba}}</ref> | |||

| ==Osmoregulation== | |||

| Like many other protists, species of ''Amoeba'' control osmotic pressures with the help of a ]-bound ] called the ]. ''Amoeba proteus'' has one contractile vacuole which slowly fills with water from the cytoplasm (diastole), then, while fusing with the cell membrane, quickly contracts (systole), releasing water to the outside by ]. This process regulates the amount of water present in the cytoplasm of the amoeba. | |||

| Immediately after the contractile vacuole (CV) expels water, its membrane crumples. Soon afterwards, many small vacuoles or vesicles appear surrounding the membrane of the CV.<ref name="Nishihara, E. 2008">{{cite journal |vauthors =Nishihara E, Yokota E, Tazaki A |title=Presence of aquaporin and V-ATPase on the contractile vacuole of ''Amoeba proteus'' |journal=Biol. Cell |volume=100 |issue=3 |pages=179–88 |date=March 2008 |pmid=18004980 |doi=10.1042/BC20070091 |display-authors=etal|doi-access= |s2cid=21011052 }}</ref> It is suggested that these vesicles split from the CV membrane itself. The small vesicles gradually increase in size as they take in water and then they fuse with the CV, which grows in size as it fills with water. Therefore, the function of these numerous small vesicles is to collect excess cytoplasmic water and channel it to the central CV. The CV swells for a number of minutes and then contracts to expel the water outside. The cycle is then repeated again. | |||

| The membranes of the small vesicles as well as the membrane of the CV have ] proteins embedded in them.<ref name="Nishihara, E. 2008"/> These ] facilitate water passage through the membranes. The presence of aquaporin proteins in both CV and the small vesicles suggests that water collection occurs both through the CV membrane itself as well as through the function of the vesicles. However, the vesicles, being more numerous and smaller, would allow a faster water uptake due to the larger total surface area provided by the vesicles.<ref name="Nishihara, E. 2008"/> | |||

| The small vesicles also have another protein embedded in their membrane: ] or V-ATPase.<ref name="Nishihara, E. 2008"/> This ATPase pumps H<sup>+</sup> ions into the vesicle lumen, lowering its pH with respect to the ]. However, the pH of the CV in some amoebas is only mildly acidic, suggesting that the H<sup>+</sup> ions are being removed from the CV or from the vesicles. It is thought that the electrochemical gradient generated by V-ATPase might be used for the transport of ions (it is presumed K<sup>+</sup> and Cl<sup>−</sup>) into the vesicles. This builds an osmotic gradient across the vesicle membrane, leading to influx of water from the cytosol into the vesicles by osmosis,<ref name="Nishihara, E. 2008"/> which is facilitated by aquaporins. | |||

| Since these vesicles fuse with the central contractile vacuole, which expels the water, ions end up being removed from the cell, which is not beneficial for a freshwater organism. The removal of ions with the water has to be compensated by some yet-unidentified mechanism. | |||

| Like other eukaryotes, ''Amoeba'' species are adversely affected by excessive ] caused by extremely saline or dilute water. In saline water, an ''Amoeba'' will prevent the influx of salt, resulting in a net loss of water as the cell becomes ] with the environment, causing the cell to shrink. Placed into ], ''Amoeba'' will match the concentration of the surrounding water, causing the cell to swell. If the surrounding water is too dilute, the cell may burst.<ref name="Patterson1981">{{cite journal | author = Patterson, D.J. | year = 1981 | title = Contractile vacuole complex behaviour as a diagnostic character for free living amoebae | journal = Protistologica | volume = 17 | pages = 243–248}}</ref> | |||

| ==Amoeba cysts== | |||

| {{main|Microbial cyst}} | |||

| In environments that are potentially lethal to the cell, an ''Amoeba'' may become dormant by forming itself into a ball and secreting a protective membrane to become a ]. The cell remains in this state until it encounters more favourable conditions.<ref name="SC" /> While in cyst form the amoeba will not replicate and may die if unable to emerge for a lengthy period of time. | |||

| <br /> | |||

| ==Video gallery== | |||

| {| | |||

| |] | |||

| |]]] | |||

| |} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * {{Commons category-inline|Amoeba|''Amoeba''}} | |||

| * {{Wikispecies-inline|Amoeba|''Amoeba''}} | |||

| {{Eukaryota classification}} | |||

| {{Amoebozoa}} | |||

| {{Taxonbar|from=Q46729}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Amoeba (Genus)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 10:37, 18 December 2024

Genus of Protozoa This article is about the genus Amoeba. For other uses, see Amoeba (disambiguation).

| Amoeba | |

|---|---|

| |

| Amoeba proteus | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Phylum: | Amoebozoa |

| Class: | Tubulinea |

| Order: | Euamoebida |

| Family: | Amoebidae |

| Genus: | Amoeba Bory de Saint-Vincent, 1822 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Amoeba is a genus of single-celled amoeboids in the family Amoebidae. The type species of the genus is Amoeba proteus, a common freshwater organism, widely studied in classrooms and laboratories.

History and classification

The earliest record of an organism resembling Amoeba was produced in 1755 by August Johann Rösel von Rosenhof, who named his discovery "der kleine Proteus" ("the little Proteus"), after Proteus, the shape-shifting sea-god of Greek Mythology. While Rösel's illustrations show a creature similar in appearance to the one now known as Amoeba proteus, his "little Proteus'' cannot be identified confidently with any modern species.

The term "Proteus animalcule" remained in use throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, as an informal name for any large, free-living amoeboid.

In 1758, apparently without seeing Rösel's "Proteus" for himself, Carl Linnaeus included the organism in his own system of classification, under the name Volvox chaos. However, because the name Volvox had already been applied to a genus of flagellate algae, he later changed the name to Chaos chaos. In 1786, the Danish Naturalist Otto Müller described and illustrated a species he called Proteus diffluens, which was probably the organism known today as Amoeba proteus.

The genus Amiba, from the Greek amoibè (ἀμοιβή), meaning "change", was erected in 1822 by Bory de Saint-Vincent. In 1830, the German naturalist C. G. Ehrenberg adopted this genus in his own classification of microscopic creatures, but changed the spelling to "Amoeba."

Anatomy, feeding and reproduction

Species of Amoeba move and feed by extending temporary structures called pseudopodia. These are formed by the coordinated action of microfilaments within the cellular cytoplasm pushing out the plasma membrane which surrounds the cell. In Amoeba, the pseudopodia are approximately tubular, and rounded at the ends (lobose). The cell's overall shape may change rapidly as pseudopodia are extended and retracted into the cell body. An Amoeba may produce many pseudopodia at once, especially when freely floating. When crawling rapidly along a surface, the cell may take a roughly monopodial form, with a single dominant pseudopod deployed in the direction of movement.

Historically, researchers have divided the cytoplasm into two parts, consisting of a granular inner endoplasm and an outer layer of clear ectoplasm, both enclosed within a flexible plasma membrane. The cell usually has a single granular nucleus, containing most of the organism's DNA . A contractile vacuole is used to maintain osmotic equilibrium by excreting excess water from the cell (see Osmoregulation).

An Amoeba obtains its food by phagocytosis, engulfing smaller organisms and particles of organic matter, or by pinocytosis, taking in dissolved nutrients through vesicles formed within the cell membrane. Food enveloped by the Amoeba is stored in digestive organelles called food vacuoles.

Amoeba, like other unicellular eukaryotic organisms, reproduces asexually by mitosis and cytokinesis. Sexual phenomena have not been directly observed in Amoeba, although sexual exchange of genetic material is known to occur in other Amoebozoan groups. Most amoebozoans appear capable of performing syngamy, recombination and ploidy reduction through a standard meiotic process. The “asexual” model organism Amoeba proteus has most of the proteins associated with sexual processes. In cases where organisms are forcibly divided, the portion that retains the nucleus will often survive and form a new cell and cytoplasm, while the other portion dies.

Osmoregulation

Like many other protists, species of Amoeba control osmotic pressures with the help of a membrane-bound organelle called the contractile vacuole. Amoeba proteus has one contractile vacuole which slowly fills with water from the cytoplasm (diastole), then, while fusing with the cell membrane, quickly contracts (systole), releasing water to the outside by exocytosis. This process regulates the amount of water present in the cytoplasm of the amoeba.

Immediately after the contractile vacuole (CV) expels water, its membrane crumples. Soon afterwards, many small vacuoles or vesicles appear surrounding the membrane of the CV. It is suggested that these vesicles split from the CV membrane itself. The small vesicles gradually increase in size as they take in water and then they fuse with the CV, which grows in size as it fills with water. Therefore, the function of these numerous small vesicles is to collect excess cytoplasmic water and channel it to the central CV. The CV swells for a number of minutes and then contracts to expel the water outside. The cycle is then repeated again.

The membranes of the small vesicles as well as the membrane of the CV have aquaporin proteins embedded in them. These transmembrane proteins facilitate water passage through the membranes. The presence of aquaporin proteins in both CV and the small vesicles suggests that water collection occurs both through the CV membrane itself as well as through the function of the vesicles. However, the vesicles, being more numerous and smaller, would allow a faster water uptake due to the larger total surface area provided by the vesicles.

The small vesicles also have another protein embedded in their membrane: vacuolar-type H-ATPase or V-ATPase. This ATPase pumps H ions into the vesicle lumen, lowering its pH with respect to the cytosol. However, the pH of the CV in some amoebas is only mildly acidic, suggesting that the H ions are being removed from the CV or from the vesicles. It is thought that the electrochemical gradient generated by V-ATPase might be used for the transport of ions (it is presumed K and Cl) into the vesicles. This builds an osmotic gradient across the vesicle membrane, leading to influx of water from the cytosol into the vesicles by osmosis, which is facilitated by aquaporins.

Since these vesicles fuse with the central contractile vacuole, which expels the water, ions end up being removed from the cell, which is not beneficial for a freshwater organism. The removal of ions with the water has to be compensated by some yet-unidentified mechanism.

Like other eukaryotes, Amoeba species are adversely affected by excessive osmotic pressure caused by extremely saline or dilute water. In saline water, an Amoeba will prevent the influx of salt, resulting in a net loss of water as the cell becomes isotonic with the environment, causing the cell to shrink. Placed into fresh water, Amoeba will match the concentration of the surrounding water, causing the cell to swell. If the surrounding water is too dilute, the cell may burst.

Amoeba cysts

Main article: Microbial cystIn environments that are potentially lethal to the cell, an Amoeba may become dormant by forming itself into a ball and secreting a protective membrane to become a microbial cyst. The cell remains in this state until it encounters more favourable conditions. While in cyst form the amoeba will not replicate and may die if unable to emerge for a lengthy period of time.

Video gallery

References

- Bory de Saint-Vincent, J.B.G.M. (1822-1831). Article "Amiba". In: Dictionnaire classique d'histoire naturelle par Messieurs Audouin, Isid. Bourdon, Ad. Brongniart, De Candolle, Daudebard de Férusac, A. Desmoulins, Drapiez, Edwards, Flourens, Geoffroy de Saint-Hilaire, A. De Jussieu, Kunth, G. de Lafosse, Lamouroux, Latreille, Lucas fils, Presle-Duplessis, C. Prévost, A. Richard, Thiébaut de Berneaud, et Bory de Saint-Vincent. Ouvrage dirigé par ce dernier collaborateur, et dans lequel on a ajouté, pour le porter au niveau de la science, un grand nombre de mots qui n'avaient pu faire partie de la plupart des Dictionnaires antérieurs. 17 vols. Paris: Rey et Gravier; Baudoin frères, vol. 1, p. 260, .

- Xu, Kaigin (2007). "National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan". The World of Protozoa, Rotifera, Nematoda and Oligochaeta. National Institute for Environmental Studies, Japan. Retrieved Sep 11, 2014.

- Friz, Carl T. (1992). "Taxonomic Analyses of Seven Species of Family Amoebidae by Isozymic Characterization of Electrophoretic Patterns and the Descriptions of a New Genus and a New Species: Metamoeba n. gen. Amoeba amazonas n. sp". Archiv für Protistenkunde. 142 (1–2): 29–40. doi:10.1016/S0003-9365(11)80098-9.

- Rösel von Rosenhof, A.J. 1755. Der monatlich-herausgege benen Insecten-Belustigung erster Theil... J.J. Fleischmann: Nürnberg. Vol. 3, Tab. 101, , p. 621, p. 622, .

- Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biology of Amoeba. New York: Academic Press. pp. 2–3.

- McAlpine, Daniel (1881). Biological atlas: a guide to the practical study of plants and animals. Edinburgh and London: W. & A. K. Johnston. p. 17.

- Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biology of Amoeba. New York: Academic Press. p. 5.

- Bory de Saint-Vincent, J. B. G. M. "Essai d'une classification des animaux microscopiques." Agasse, Paris (1826).p. 28

- McGrath, Kimberley; Blachford, Stacey, eds. (2001). Gale Encyclopedia of Science Vol. 1: Aardvark-Catalyst (2nd ed.). Gale Group. ISBN 978-0-7876-4370-6. OCLC 46337140.

- Ehrenberg, Christian Gottfried. Organisation, systematik und geographisches verhältniss der infusionsthierchen: Zwei vorträge, in der Akademie der wissenschaften zu Berlin gehalten in den jahren 1828 und 1830. Druckerei der Königlichen akademie der wissenschaften, 1832. p. 59

- Alberts Eds.; et al. (2007). Molecular Biology of the Cell 5th Edition. New York: Garland Science. p. 1037. ISBN 9780815341055.

- Siemensma, Ferry. "Amoeba". Microworld: World of Amoeboid Organisms. Ferry Siemensma. Retrieved Sep 11, 2014.

- Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biology of Amoeba. New York: Academic Press. p. 102.

- Jeon, Kwang W. (1973). Biology of Amoeba. New York: Academic Press. p. 100.

- Lahr DJ, Parfrey LW, Mitchell EA, Katz LA, Lara E (July 2011). "The chastity of amoebae: re-evaluating evidence for sex in amoeboid organisms". Proc. Biol. Sci. 278 (1715): 2083–6. doi:10.1098/rspb.2011.0289. PMC 3107637. PMID 21429931.

- ^ Hofstatter PG, Brown MW, Lahr DJG (November 2018). "Comparative Genomics Supports Sex and Meiosis in Diverse Amoebozoa". Genome Biol Evol. 10 (11): 3118–3128. doi:10.1093/gbe/evy241. PMC 6263441. PMID 30380054.

- ^ "Amoeba". Scienceclarified.com.

- ^ Nishihara E, Yokota E, Tazaki A, et al. (March 2008). "Presence of aquaporin and V-ATPase on the contractile vacuole of Amoeba proteus". Biol. Cell. 100 (3): 179–88. doi:10.1042/BC20070091. PMID 18004980. S2CID 21011052.

- Patterson, D.J. (1981). "Contractile vacuole complex behaviour as a diagnostic character for free living amoebae". Protistologica. 17: 243–248.

External links

| Eukaryote classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Incertae sedis |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Amoeba | |