| Revision as of 19:53, 15 July 2008 editXargque (talk | contribs)209 editsm Citation Needed for 1882 proof← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:56, 15 November 2024 edit undo174.109.9.57 (talk) Undid revision 1257640449 by 174.109.9.57 (talk)Tag: Undo | ||

| (836 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Problem of constructing equal-area shapes}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{other uses|Squaring the circle (disambiguation)|Square the Circle (disambiguation)|Squared circle (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{distinguish|Square peg in a round hole}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{Pi box}} | |||

| '''Squaring the circle''' is a problem in ] first proposed in ]. It is the challenge of constructing a ] with the ] by using only a finite number of steps with a ]. The difficulty of the problem raised the question of whether specified ]s of ] concerning the existence of ] and ]s implied the existence of such a square. | |||

| In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible, as a consequence of the ], which proves that ] (<math>\pi</math>) is a ]. | |||

| '''Squaring the circle''' is a problem proposed by ] ]. It is the challenge to construct a ] with the same area as a given ] by using only a finite number of steps with ]. More abstractly and more precisely, it may be taken to ask whether specified ]s of ] concerning the existence of lines and circles entail the existence of such a square. | |||

| That is, <math>\pi</math> is not the ] of any ] with ] coefficients. It had been known for decades that the construction would be impossible if <math>\pi</math> were transcendental, but that fact was not proven until 1882. Approximate constructions with any given non-perfect accuracy exist, and many such constructions have been found. | |||

| Despite the proof that it is impossible, attempts to square the circle have been common in ] (i.e. the work of mathematical cranks). The expression "squaring the circle" is sometimes used as a metaphor for trying to do the impossible.{{r|idioms}} | |||

| In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible{{fact|July 2008}}, as a consequence of the fact that ] (π) is a ], rather than algebraic irrational number; that is, it is not the ] of any ] with rational coefficients. It had been known for some decades before then that ''if'' π ''were'' transcendental then the construction would be impossible, but that π ''is'' transcendental was not proven until 1882. Approximate squaring to any given non-perfect accuracy, on the other hand, is possible in a finite number of steps, as a consequence of the fact that there are rational numbers arbitrarily close to π. | |||

| The term '' |

The term ''quadrature of the circle'' is sometimes used as a synonym for squaring the circle. It may also refer to approximate or ] for finding the ]. In general, ] or squaring may also be applied to other plane figures. | ||

| ]).]] | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| Methods to calculate the approximate area of a given circle, which can be thought of as a precursor problem to squaring the circle, were known already in many ancient cultures. These methods can be summarized by stating the ] that they produce. In around 2000 BCE, the ] used the approximation {{nowrap|<math>\pi\approx\tfrac{25}{8}=3.125</math>,}} and at approximately the same time the ] used {{nowrap|<math>\pi\approx\tfrac{256}{81}\approx 3.16</math>.}} Over 1000 years later, the ] '']'' used the simpler approximation {{nowrap|<math>\pi\approx3</math>.{{r|b3p}}}} Ancient ], as recorded in the '']'' and '']'', used several different approximations {{nowrap|to <math>\pi</math>.{{r|plofker}}}} ] proved a formula for the area of a circle, according to which <math>3\,\tfrac{10}{71}\approx 3.141<\pi<3\,\tfrac{1}{7}\approx 3.143</math>.{{r|b3p}} In ], in the third century CE, ] found even more accurate approximations using a method similar to that of Archimedes, and in the fifth century ] found <math>\pi\approx 355/113\approx 3.141593</math>, an approximation known as ].{{r|china}} | |||

| Methods to ''approximate'' to the area of a given circle with a square were known already to ]. The Egyptian ] of 1800BC gives the area of a circle as (64/81) ''d''<sup> 2</sup>, where ''d'' is the diameter of the circle, and ''π'' approximated to 256/81, a number that appears in the older Moscow Mathematical Papyrus, and used for volume approximations (ie ]). ] also found an approximate method, though less accurate, documented in the '']''.<ref>O'Connor, John J. and Robertson, Edmund F. (2000). , ], ].</ref> | |||

| The problem of constructing a square whose area is exactly that of a circle, rather than an approximation to it, comes from ]. Greek mathematicians found compass and straightedge constructions to convert any ] into a square of equivalent area.<ref name=square-polygons/> They used this construction to compare areas of polygons geometrically, rather than by the numerical computation of area that would be more typical in modern mathematics. As ] wrote many centuries later, this motivated the search for methods that would allow comparisons with non-polygonal shapes: | |||

| ] of attempts at the problem.<ref>Florian Cajori, ''A History of Mathematics'', second edition, p.143, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1919.</ref>]] | |||

| {{bi|left=1.6|Having taken their lead from this problem, I believe, the ancients also sought the quadrature of the circle. For if a parallelogram is found equal to any rectilinear figure, it is worthy of investigation whether one can prove that rectilinear figures are equal to figures bound by circular arcs.<ref>Translation from {{harvtxt|Knorr|1986}}, p. 25</ref>}} | |||

| The first Greek to be associated with the problem was ], who worked on it while in prison. ] squared certain ], in the hope that it would lead to a solution. ] believed that inscribing regular polygons within a circle and doubling the number of sides will eventually fill up the area of the circle, and since a polygon can be squared, it means the circle can be squared. Even then there were skeptics—] argued that magnitudes cannot be divided up without limit, so the area of the circle will never be used up<ref>{{cite book| last = Heath | first = Thomas | year = 1981 | title = History of Greek Mathematics | publisher = Courier Dover Publications}}</ref>. The problem was even mentioned in ]'s play ]. | |||

| ]. Its area is equal to the area of the triangle {{math|ABC}} (found by ]).]] | |||

| It is believed that ] was the first Greek who required a plane solution (that is, using only a compass and straightedge). ] attempted a proof of its impossibility in ''Vera Circuli et Hyperbolae Quadratura'' (The True Squaring of the Circle and of the Hyperbola) in 1667. Although his proof was incorrect, it was the first paper to attempt to solve the problem using algebraic properties of ]. It was not until 1882 that ] rigorously proved its impossibility. | |||

| The first known Greek to study the problem was ], who worked on it while in prison. ] attacked the problem by finding a shape bounded by circular arcs, the ], that could be squared. ] believed that inscribing regular polygons within a circle and doubling the number of sides would eventually fill up the area of the circle (this is the ]). Since any polygon can be squared,<ref name=square-polygons>The construction of a square equal in area to a given polygon is Proposition 14 of ], Book II.</ref> he argued, the circle can be squared. In contrast, ] argued that magnitudes can be divided up without limit, so the area of the circle would never be used up.{{r|heath}} Contemporaneously with Antiphon, ] argued that, since larger and smaller circles both exist, there must be a circle of equal area; this principle can be seen as a form of the modern ].{{r|bryson}} The more general goal of carrying out all geometric constructions using only a ] has often been attributed to ], but the evidence for this is circumstantial.{{r|knorr}} | |||

| The problem of finding the area under an arbitrary curve, now known as ] in ], or ] in ], was known as ''squaring'' before the invention of calculus.{{r|guicciardini}} Since the techniques of calculus were unknown, it was generally presumed that a squaring should be done via geometric constructions, that is, by compass and straightedge. For example, ] wrote to ] in 1676 "I believe M. Leibnitz will not dislike the theorem towards the beginning of my letter pag. 4 for squaring curve lines geometrically".{{r|newton-cotes}} In modern mathematics the terms have diverged in meaning, with quadrature generally used when methods from calculus are allowed, while squaring the curve retains the idea of using only restricted geometric methods. | |||

| A 1647 attempt at squaring the circle, ''Opus geometricum quadraturae circuli et sectionum coni decem libris comprehensum'' by ], was heavily criticized by ].{{r|leotaud}} Nevertheless, de Saint-Vincent succeeded in his quadrature of the ], and in doing so was one of the earliest to develop the ].{{r|burn}} ], following de Saint-Vincent, attempted another proof of the impossibility of squaring the circle in ''Vera Circuli et Hyperbolae Quadratura'' (The True Squaring of the Circle and of the Hyperbola) in 1667. Although his proof was faulty, it was the first paper to attempt to solve the problem using algebraic properties of <math>\pi</math>.{{r|gregory|crippa}} ] proved in 1761 that <math>\pi</math> is an ].{{r|lambert1|lambert2}} It was not until 1882 that ] succeeded in proving more strongly that {{pi}} is a ], and by doing so also proved the impossibility of squaring the circle with compass and straightedge.{{r|lindemann|fritsch}} | |||

| After Lindemann's impossibility proof, the problem was considered to be settled by professional mathematicians, and its subsequent mathematical history is dominated by ] attempts at circle-squaring constructions, largely by amateurs, and by the debunking of these efforts.{{r|dudley}} As well, several later mathematicians including ] developed compass and straightedge constructions that approximate the problem accurately in few steps.{{r|ramanujan1|ramanujan2}} | |||

| Two other classical problems of antiquity, famed for their impossibility, were ] and ]. Like squaring the circle, these cannot be solved by compass and straightedge. However, they have a different character than squaring the circle, in that their solution involves the root of a ], rather than being transcendental. Therefore, more powerful methods than compass and straightedge constructions, such as ] or ], can be used to construct solutions to these problems.{{r|origami1|origami2}} | |||

| ==Impossibility== | ==Impossibility== | ||

| The solution of the problem of squaring the circle by compass and straightedge |

The solution of the problem of squaring the circle by compass and straightedge requires the construction of the number <math>\sqrt\pi</math>, the length of the side of a square whose area equals that of a unit circle. If <math>\sqrt\pi</math> were a ], it would follow from standard ] constructions that <math>\pi</math> would also be constructible. In 1837, ] showed that lengths that could be constructed with compass and straightedge had to be solutions of certain polynomial equations with rational coefficients.{{r|wantzel|cajori-on-wantzel}} Thus, constructible lengths must be ]s. If the circle could be squared using only compass and straightedge, then <math>\pi</math> would have to be an algebraic number. It was not until 1882 that ] proved the transcendence of <math>\pi</math> and so showed the impossibility of this construction. Lindemann's idea was to combine the proof of transcendence of ] <math>e</math>, shown by ] in 1873, with ] | ||

| <math display=block>e^{i\pi}=-1.</math> | |||

| This identity immediately shows that <math>\pi</math> is an ], because a rational power of a transcendental number remains transcendental. Lindemann was able to extend this argument, through the ] on linear independence of algebraic powers of <math>e</math>, to show that <math>\pi</math> is transcendental and therefore that squaring the circle is impossible.{{r|lindemann|fritsch}} | |||

| Bending the rules by introducing a supplemental tool, allowing an infinite number of compass-and-straightedge operations or by performing the operations in certain ] makes squaring the circle possible in some sense. For example, ] uses the ] to square the circle, meaning that if this curve is somehow already given, then a square and circle of equal areas can be constructed from it. The ] can be used for another similar construction.{{r|boymer}} Although the circle cannot be squared in ], it sometimes can be in ] under suitable interpretations of the terms. The hyperbolic plane does not contain squares (quadrilaterals with four right angles and four equal sides), but instead it contains ''regular quadrilaterals'', shapes with four equal sides and four equal angles sharper than right angles. There exist in the hyperbolic plane (]) infinitely many pairs of constructible circles and constructible regular quadrilaterals of equal area, which, however, are constructed simultaneously. There is no method for starting with an arbitrary regular quadrilateral and constructing the circle of equal area. Symmetrically, there is no method for starting with an arbitrary circle and constructing a regular quadrilateral of equal area, and for sufficiently large circles no such quadrilateral exists.{{r|hyper1|hyper2}} | |||

| It is possible to construct a square with an area ''arbitrarily close'' to that of a given circle. If a rational number is used as an approximation of π, then squaring the circle becomes possible, depending on the values chosen. However, this is only an approximation and does not meet the constraints of the ancient rules for solving the problem. Several mathematicians have demonstrated workable procedures based on a variety of approximations. | |||

| == Approximate constructions == | |||

| Bending the rules by allowing an infinite number of compass-and-straightedge operations or by performing the operations on certain non-]s also makes squaring the circle possible. For example, although the circle cannot be squared in Euclidean space, it can in ] (hyperbolic geometric space). | |||

| Although squaring the circle exactly with compass and straightedge is impossible, approximations to squaring the circle can be given by constructing lengths close to <math>\pi</math>. | |||

| It takes only elementary geometry to convert any given rational approximation of <math>\pi</math> into a corresponding ], but such constructions tend to be very long-winded in comparison to the accuracy they achieve. After the exact problem was proven unsolvable, some mathematicians applied their ingenuity to finding approximations to squaring the circle that are particularly simple among other imaginable constructions that give similar precision. | |||

| === Construction by Kochański === | |||

| Note that the transcendence of π implies the impossibility of exactly "circling" the square, as well as of squaring the circle. | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | image1 = Kochanski-1.svg | |||

| | caption1 = ] approximate construction | |||

| | image2 = Quadratur des kreises.svg | |||

| | caption2 = Continuation with equal-area circle and square; <math>r</math> denotes the initial radius | |||

| | total_width = 600 | |||

| }} | |||

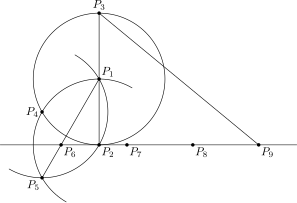

| One of many early historical approximate compass-and-straightedge constructions is from a 1685 paper by Polish Jesuit ], producing an approximation diverging from <math>\pi</math> in the 5th decimal place. Although much more precise numerical approximations to <math>\pi</math> were already known, Kochański's construction has the advantage of being quite simple.{{r|kochanski1}} In the left diagram | |||

| <math display=block>|P_3 P_9|=|P_1 P_2|\sqrt{\frac{40}{3}-2\sqrt{3}}\approx 3.141\,5{\color{red}33\,338}\cdot|P_1 P_2|\approx \pi r.</math> | |||

| In the same work, Kochański also derived a sequence of increasingly accurate rational approximations {{nowrap|for <math>\pi</math>.{{r|kochanski2}}}} | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| === Constructions using 355/113 === | |||

| ==Modern approximative constructions== | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Though squaring the circle is an impossible problem using only compass and straightedge, approximations to squaring the circle can be given by constructing lengths close to π. | |||

| |image1=01 Squaring the circle-Gelder-1849.svg|caption1=Jacob de Gelder's 355/113 construction | |||

| It takes only minimal knowledge of elementary geometry to convert any given rational approximation of π into a corresponding compass-and-straightedge construction, but constructions made in this way tend to be very long-winded in comparison to the accuracy they achieve. After the exact problem was proven unsolvable, some mathematicians have applied their ingenuity to finding ''elegant'' approximations to squaring the circle, defined roughly (and informally) as constructions that are particularly simple among other imaginable constructions that give similar precision. | |||

| |image2=Approximately squaring the circle.svg|caption2=Ramanujan's 355/113 construction | |||

| |total_width=600}} | |||

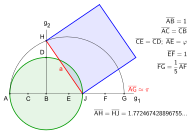

| Jacob de Gelder published in 1849 a construction based on the approximation | |||

| <math display=block>\pi\approx\frac{355}{113} = 3.141\;592{\color{red}\;920\;\ldots}</math> | |||

| This value is accurate to six decimal places and has been known in China since the 5th century as ], and in Europe since the 17th century.{{r|hobson}} | |||

| Gelder did not construct the side of the square; it was enough for him to find the value | |||

| Among the modern approximate constructions was one by ] in 1913 (see his book<ref>Hobson, Ernest William (1913). ''Squaring the Circle: A History of the Problem'', Cambridge University Press. Reprinted by Merchant Books in 2007.</ref>). This was a fairly accurate construction which was based on constructing the approximate value of 3.14164079..., which is accurate to 4 decimals. | |||

| <math display=block>\overline{AH}= \frac{4^2}{7^2+8^2}.</math> | |||

| The illustration shows de Gelder's construction. | |||

| Indian mathematician ] |

In 1914, Indian mathematician ] gave another geometric construction for the same approximation.{{r|ramanujan1|ramanujan2}} | ||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| === Constructions using the golden ratio === | |||

| :<math>\frac{355}{113} = 3.1415929203539823008\dots</math> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | image1 = 01 Squaring the circle-Hobson.svg | |||

| | caption1 = Hobson's golden ratio construction | |||

| | image2 = 01 Squaring the circle-Dixon.svg | |||

| | caption2 = Dixon's golden ratio construction | |||

| | total_width = 600 | |||

| | image3 = Squaring the circle like a medieval Master Mason, by Frederic Beatrix.png | |||

| | caption3 = Beatrix's 13-step construction | |||

| }} | |||

| An approximate construction by ] in 1913{{r|hobson}} is accurate to three decimal places. Hobson's construction corresponds to an approximate value of | |||

| which is accurate to 6 decimal places of π. | |||

| <math display="block">\frac{6}{5}\cdot \left( 1 + \varphi\right) = 3.141\;{\color{red}640\;\ldots},</math> where <math>\varphi</math> is the ], <math>\varphi=(1+\sqrt5)/2</math>. | |||

| The same approximate value appears in a 1991 construction by ].{{r|dixon}} In 2022 Frédéric Beatrix presented a ] construction in 13 steps.{{r|beatrix}} | |||

| Srinivasa Ramanujan in 1914 gave a ruler and compass construction which was equivalent to taking the approximate value for π to be | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| === Second construction by Ramanujan === | |||

| :<math>\left(9^2 + \frac{19^2}{22}\right)^{1/4} = \sqrt{\frac{2143}{22}} = 3.1415926525826461252\dots</math> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | image1 = Squaring_the_circle-Ramanujan-1914.svg | |||

| | caption1 = Squaring the circle, approximate construction according to Ramanujan of 1914, with continuation of the construction (dashed lines, mean proportional red line), see ]. | |||

| | image2 = Squaring the circle-Ramanujan-1913.png | |||

| | caption2 = Sketch of "Manuscript book 1 of Srinivasa Ramanujan" p. 54, Ramanujan's 355/113 construction | |||

| | total_width = 500 | |||

| }} | |||

| In 1914, Ramanujan gave a construction which was equivalent to taking the approximate value for <math>\pi</math> to be | |||

| giving a remarkable 8 decimal places of π. | |||

| <math display=block>\left(9^2 + \frac{19^2}{22}\right)^\frac14 = \sqrt{\frac{2143}{22}} = 3.141\;592\;65{\color{red}2\;582\;\ldots}</math> | |||

| giving eight decimal places of <math>\pi</math>.{{r|ramanujan1|ramanujan2}} | |||

| He describes the construction of line segment OS as follows.{{r|ramanujan1}} | |||

| {{bi|left=1.6|Let AB (Fig.2) be a diameter of a circle whose centre is O. Bisect the arc ACB at C and trisect AO at T. Join BC and cut off from it CM and MN equal to AT. Join AM and AN and cut off from the latter AP equal to AM. Through P draw PQ parallel to MN and meeting AM at Q. Join OQ and through T draw TR, parallel to OQ and meeting AQ at R. Draw AS perpendicular to AO and equal to AR, and join OS. Then the mean proportional between OS and OB will be very nearly equal to a sixth of the circumference, the error being less than a twelfth of an inch when the diameter is 8000 miles long.}} | |||

| In 1991, ] gave constructions for | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| ==Incorrect constructions== | |||

| :<math>\frac{6}{5} (1 + \varphi)</math> and <math>\sqrt{{40 \over 3} - 2 \sqrt{3}\ }</math> | |||

| In his old age, the English philosopher ] convinced himself that he had succeeded in squaring the circle, a claim refuted by ] as part of the ].{{r|bird}} During the 18th and 19th century, the false notions that the problem of squaring the circle was somehow related to the ], and that a large reward would be given for a solution, became prevalent among would-be circle squarers.{{r|demorgan|longitude}} In 1851, John Parker published a book ''Quadrature of the Circle'' in which he claimed to have squared the circle. His method actually produced an approximation of <math>\pi</math> accurate to six digits.{{r|beckmann|schepler|abeles}} | |||

| The ]-age mathematician, logician, and writer Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known by his pseudonym ], also expressed interest in debunking illogical circle-squaring theories. In one of his diary entries for 1855, Dodgson listed books he hoped to write, including one called "Plain Facts for Circle-Squarers". In the introduction to "A New Theory of Parallels", Dodgson recounted an attempt to demonstrate logical errors to a couple of circle-squarers, stating:{{r|gardner}} | |||

| (]), though these were only accurate to 4 decimal places of π. | |||

| {{bi|left=1.6|The first of these two misguided visionaries filled me with a great ambition to do a feat I have never heard of as accomplished by man, namely to convince a circle squarer of his error! The value my friend selected for Pi was 3.2: the enormous error tempted me with the idea that it could be easily demonstrated to BE an error. More than a score of letters were interchanged before I became sadly convinced that I had no chance.}} | |||

| ==Squaring or quadrature as integration== | |||

| A ridiculing of circle squaring appears in ]'s book ''A Budget of Paradoxes'', published posthumously by his widow in 1872. Having originally published the work as a series of articles in '']'', he was revising it for publication at the time of his death. Circle squaring declined in popularity after the nineteenth century, and it is believed that De Morgan's work helped bring this about.{{r|dudley}} | |||

| The problem of finding the area under a curve, known as ] in ], or ] in ], was known as ''squaring'' before the invention of calculus. Since the techniques of calculus were unknown, it was generally presumed that a squaring should be done via geometric constructions, that is, by compass and straightedge. For example ] wrote to ] in 1676 "I believe M. Leibnitz will not dislike þ<sup>e</sup> Theorem towards þ<sup>e</sup> beginning of my letter pag. 4 for '''squaring Curve lines''' Geometrically." (emphasis added) After Newton and ] invented calculus, they still referred to this integration problem as squaring a curve. | |||

| ] | |||

| =="Squaring the circle" as a metaphor== | |||

| Even after it had been proved impossible, in 1894, amateur mathematician Edwin J. Goodwin claimed that he had developed a method to square the circle. The technique he developed did not accurately square the circle, and provided an incorrect area of the circle which essentially redefined <math>\pi</math> as equal to 3.2. Goodwin then proposed the ] in the Indiana state legislature allowing the state to use his method in education without paying royalties to him. The bill passed with no objections in the state house, but the bill was tabled and never voted on in the Senate, amid increasing ridicule from the press.{{r|indiana}} | |||

| The futility of exercises aimed at finding the quadrature of the circle has lent itself to metaphors describing a hopeless, meaningless, or vain undertaking. | |||

| The mathematical crank ] also claimed to have squared the circle in his 1934 book, "Behold! : the grand problem no longer unsolved: the circle squared beyond refutation."{{r|heisel}} ] referred to the book as a "classic crank book."{{r|halmos}} | |||

| For example, in Spanish, the expression ''"descubriste la cuadratura del círculo"'' ("you discovered the quadrature of the circle") is often used derisively to dismiss claims that someone has found a simple solution to a particularly hard or intractable problem.<ref>Colaboradores de Misplaced Pages. Cuadratura del círculo . Misplaced Pages, La enciclopedia libre, 2008 . Disponible en <http://es.wikipedia.org/search/?title=Cuadratura_del_c%C3%ADrculo>.</ref> | |||

| ==In literature== | |||

| ==Claims of circle squaring, and the longitude problem== | |||

| The problem of squaring the circle has been mentioned over a wide range of literary eras, with a variety of ]ical meanings.{{r|tubbs}} Its literary use dates back at least to 414 BC, when the play '']'' by ] was first performed. In it, the character ] mentions squaring the circle, possibly to indicate the paradoxical nature of his utopian city.{{r|amati}} | |||

| The mathematical proof that the ] of the circle is impossible using only compass and straightedge has not proved to be a hindrance to the many people who have invested years in this problem anyway. Having squared the circle is a famous ] assertion. (''See also'' ].) In his old age, the English philosopher ] convinced himself that he had succeeded in squaring the circle. | |||

| ]'']] | |||

| During the 18th and 19th century the notion that the problem of squaring the circle was somehow related to the ] seems to have become prevalent among would-be circle squarers. Using "cyclometer" for circle-squarer, ] wrote in 1872: | |||

| Dante's '']'', canto XXXIII, lines 133–135, contain the verse: | |||

| <poem style="margin-left: 1.6em"> | |||

| As the geometer his mind applies | |||

| To square the circle, nor for all his wit | |||

| Finds the right formula, howe'er he tries</poem> | |||

| <poem style="margin-left: 1.6em"> | |||

| Qual è ’l geométra che tutto s’affige | |||

| per misurar lo cerchio, e non ritrova, | |||

| pensando, quel principio ond’elli indige,</poem> | |||

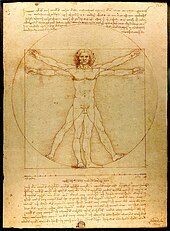

| For Dante, squaring the circle represents a task beyond human comprehension, which he compares to his own inability to comprehend Paradise.{{r|paradiso1}} Dante's image also calls to mind a passage from ], famously illustrated later in ]'s '']'', of a man simultaneously inscribed in a circle and a square.{{r|paradiso2}} Dante uses the circle as a symbol for God, and may have mentioned this combination of shapes in reference to the simultaneous divine and human nature of Jesus.{{r|tubbs|paradiso2}} Earlier, in canto XIII, Dante calls out Greek circle-squarer Bryson as having sought knowledge instead of wisdom.{{r|tubbs}} | |||

| Several works of 17th-century poet ] elaborate on the circle-squaring problem and its metaphorical meanings, including a contrast between unity of truth and factionalism, and the impossibility of rationalizing "fancy and female nature".{{r|tubbs}} By 1742, when ] published the fourth book of his '']'', attempts at circle-squaring had come to be seen as "wild and fruitless":{{r|schepler}} | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| <poem style="margin-left: 1.6em">Mad Mathesis alone was unconfined, | |||

| ] says, speaking of France, that he finds three notions prevalent among cyclometers: 1. That there is a large reward offered for success; 2. That the longitude problem depends on that success; 3. That the solution is the great end and object of geometry. The same three notions are equally prevalent among the same class in England. No reward has ever been offered by the government of either country.<ref>] (1872) ''A Budget of Paradoxes,'' p. 96.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Too mad for mere material chains to bind, | |||

| Now to pure space lifts her ecstatic stare, | |||

| Now, running round the circle, finds it square.</poem> | |||

| Similarly, the ] comic opera '']'' features a song which satirically lists the impossible goals of the women's university run by the title character, such as finding ]. One of these goals is "And the circle – they will square it/Some fine day."{{r|dolid}} | |||

| Although from 1714 to 1828 the British government did indeed sponsor a ] for finding a solution to the longitude problem, exactly why the connection was made to squaring the circle is not clear; especially since two non-geometric methods had been found by the late 1760s. De Morgan goes on to say that "he longitude problem in no way depends upon perfect solution; existing approximations are sufficient to a point of accuracy far beyond what can be wanted." In his book, de Morgan also mentions receiving many threatening letters from would-be circle squarers, accusing him of trying to "cheat them out of their prize." | |||

| The ], a poetic form first used in the 12th century by ], has been said to metaphorically square the circle in its use of a square number of lines (six stanzas of six lines each) with a circular scheme of six repeated words. {{harvtxt|Spanos|1978}} writes that this form invokes a symbolic meaning in which the circle stands for heaven and the square stands for the earth.{{r|sestina}} A similar metaphor was used in "Squaring the Circle", a 1908 short story by ], about a long-running family feud. In the title of this story, the circle represents the natural world, while the square represents the city, the world of man.{{r|bloom}} | |||

| In later works, circle-squarers such as ] in ]'s novel '']'' and Lawyer Paravant in ]'s '']'' are seen as sadly deluded or as unworldly dreamers, unaware of its mathematical impossibility and making grandiose plans for a result they will never attain.{{r|pendrick|goggin}} | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * {{annotated link|Mrs. Miniver's problem}} | |||

| * {{annotated link|Round square copula}} | |||

| * {{annotated link|Squircle}} | |||

| * {{annotated link|Tarski's circle-squaring problem}} | |||

| {{Clear}} | |||

| * The two other classical problems of antiquity were ] and "]", described in the ] article. Unlike squaring the circle, these two problems can be solved by the slightly more powerful construction method of ], as described at '']''. | |||

| * For a more modern related problem, see ]. | |||

| * The ], an 1897 attempt by the ] to dictate a solution to the problem by legislative fiat. | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist|30em|refs= | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| <ref name=abeles>{{cite journal|last=Abeles|first=Francine F.|doi=10.1006/hmat.1993.1013|issue=2|journal=Historia Mathematica|mr=1221681|pages=151–159|title=Charles L. Dodgson's geometric approach to arctangent relations for pi|volume=20|year=1993|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * at the ] | |||

| * at ] | |||

| * at ], includes information on procedures based on various approximations of π | |||

| * at | |||

| * at | |||

| * Pi accurate to 8 decimal places, using straightedge and compass. | |||

| *, lecture by ], at ], 16 January 2008 (available for download as text, audio or video file). | |||

| <ref name=amati>{{Cite journal| last = Amati | first = Matthew | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | jstor = 10.5184/classicalj.105.3.213 | |||

| | pages = 213–222 | |||

| | title = Meton's star-city: Geometry and utopia in Aristophanes' ''Birds'' | |||

| | volume = 105 | |||

| | year = 2010| doi = 10.5184/classicalj.105.3.213 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=b3p>{{cite journal | |||

| | last1 = Bailey | first1 = D. H. | author1-link = David H. Bailey (mathematician) | |||

| | last2 = Borwein | first2 = J. M. | author2-link = Jonathan Borwein | |||

| | last3 = Borwein | first3 = P. B. | author3-link = Peter Borwein | |||

| | last4 = Plouffe | first4 = S. | author4-link = Simon Plouffe | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/BF03024340 | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 1439159 | |||

| | pages = 50–57 | |||

| | title = The quest for pi | |||

| | volume = 19 | |||

| | year = 1997| s2cid = 14318695 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=beatrix>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Beatrix | first = Frédéric | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | journal = Parabola | |||

| | publisher = UNSW School of Mathematics and Statistics | |||

| | title = Squaring the circle like a medieval master mason | |||

| | url = https://www.parabola.unsw.edu.au/2020-2029/volume-58-2022/issue-2/article/squaring-circle-medieval-master-mason | |||

| | volume = 58 | |||

| | year = 2022}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=beckmann>{{cite book |last1=Beckmann |first1=Petr|author-link= Petr Beckmann |title=A History of Pi |date=2015 |publisher=St. Martin's Press |isbn=9781466887169 |pages=178 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=10jABQAAQBAJ&pg=PA18|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=bird>{{cite journal | last=Bird | first=Alexander | title=Squaring the Circle: Hobbes on Philosophy and Geometry | journal=] | volume=57 | issue=2 | pages=217–231 | year=1996 | doi=10.1353/jhi.1996.0012 | s2cid=171077338 | url=https://seis.bristol.ac.uk/~plajb/research/papers/Squaring_the_Circle.html | access-date=14 November 2020 | archive-date=16 January 2022 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220116220209/https://seis.bristol.ac.uk/~plajb/research/papers/Squaring_the_Circle.html | url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=bloom>{{Cite book|title=Twentieth-century American literature|first=Harold|last=Bloom|author-link=Harold Bloom|publisher=Chelsea House Publishers|year=1987|isbn=9780877548034|page=1848|quote=Similarly, the story "Squaring the Circle" is permeated with the integrating image: nature is a circle, the city a square.}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=boymer>{{Cite book|last1=Boyer|first1=Carl B.|author1-link= Carl Benjamin Boyer |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=V6RUDwAAQBAJ|title=A History of Mathematics|last2=Merzbach|first2=Uta C.|author2-link= Uta Merzbach |date=2011-01-11|publisher=John Wiley & Sons|isbn=978-0-470-52548-7|language=en|oclc=839010064|pages=62–63, 113–115}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=bryson>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Bos | first = Henk J. M. | |||

| | contribution = The legitimation of geometrical procedures before 1590 | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/978-1-4613-0087-8_2 | |||

| | mr = 1800805 | |||

| | pages = 23–36 | |||

| | publisher = Springer | location = New York | |||

| | series = Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences | |||

| | title = Redefining Geometrical Exactness: Descartes' Transformation of the Early Modern Concept of Construction | |||

| | year = 2001| isbn = 978-1-4612-6521-4 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=burn>{{cite journal |author-first=R.P. |author-last=Burn |date=2001 |title=Alphonse Antonio de Sarasa and logarithms |journal=] |volume=28|pages=1–17|doi=10.1006/hmat.2000.2295}}</ref> | |||

| <!-- <ref name=cajori>{{cite book|first=Florian|last=Cajori|author-link=Florian Cajori|title=A History of Mathematics|edition=2nd|page= |location= New York|publisher= The Macmillan Company|year=1919|url=https://archive.org/details/ahistorymathema03cajogoog}}</ref> --> | |||

| <ref name=cajori-on-wantzel>{{cite journal|last=Cajori|first=Florian|author-link=Florian Cajori|title=Pierre Laurent Wantzel|journal=]|year=1918|volume=24|issue=7|pages=339–347|mr=1560082|doi=10.1090/s0002-9904-1918-03088-7|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=china>{{cite journal | |||

| | last1 = Lam | first1 = Lay Yong | |||

| | last2 = Ang | first2 = Tian Se | |||

| | doi = 10.1016/0315-0860(86)90055-8 | |||

| | issue = 4 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 875525 | |||

| | pages = 325–340 | |||

| | title = Circle measurements in ancient China | |||

| | volume = 13 | |||

| | year = 1986 | |||

| | doi-access = free | |||

| }} Reprinted in {{cite book | |||

| |title=Pi: A Source Book | |||

| |editor1-first=J. L.|editor1-last=Berggren | |||

| |editor2-first=Jonathan M.|editor2-last=Borwein | |||

| |editor3-first=Peter|editor3-last=Borwein | |||

| |publisher=Springer | |||

| |year= 2004 |isbn= 978-0387205717 |pages= 20–35 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=QlbzjN_5pDoC&pg=PA20}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=crippa>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Crippa | first = Davide | |||

| | contribution = James Gregory and the impossibility of squaring the central conic sections | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/978-3-030-01638-8_2 | |||

| | pages = 35–91 | |||

| | publisher = Springer International Publishing | |||

| | title = The Impossibility of Squaring the Circle in the 17th Century | |||

| | year = 2019| isbn = 978-3-030-01637-1 | |||

| | s2cid = 132820288 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=demorgan>{{cite book|first=Augustus|last=De Morgan|author-link=Augustus De Morgan |year=1872|title=]|page= 96}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=dixon>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Dixon | first = Robert A. | author-link = Robert Dixon (mathematician) | |||

| | contribution = Squaring the circle | |||

| | pages = 44–47 | |||

| | publisher = Blackwell | |||

| | title = Mathographics | |||

| | contribution-url = https://books.google.com/books?id=1fDgb17bgBkC&pg=PA44 | |||

| | year = 1987}} Reprinted by Dover Publications, 1991</ref> | |||

| <ref name=dolid>{{Cite journal| last = Dolid | first = William A. | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | jstor = 40682600 | |||

| | pages = 52–56 | |||

| | title = Vivie Warren and the Tripos | |||

| | volume = 23 | |||

| | year = 1980}} Dolid contrasts Vivie Warren, a fictional female mathematics student in '']'' by ], with the satire of college women presented by Gilbert and Sullivan. He writes that "Vivie naturally knew better than to try to square circles."</ref> | |||

| <ref name=dudley>{{Cite book|first=Underwood|last=Dudley|author-link=Underwood Dudley|title=A Budget of Trisections|publisher=Springer-Verlag|year=1987|isbn=0-387-96568-8|pages=xi–xii}} Reprinted as ''The Trisectors''.</ref> | |||

| <ref name=fritsch>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Fritsch | first = Rudolf | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/BF03322501 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 774394 | |||

| | pages = 164–183 | |||

| | title = The transcendence of {{pi}} has been known for about a century—but who was the man who discovered it? | |||

| | volume = 7 | |||

| | year = 1984| s2cid = 119986449 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=gardner>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Gardner | first = Martin | author-link = Martin Gardner | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/0-387-28952-6 | |||

| | isbn = 0-387-94673-X | |||

| | pages = 29–31 | |||

| | publisher = Copernicus | location = New York | |||

| | title = The Universe in a Handkerchief: Lewis Carroll's Mathematical Recreations, Games, Puzzles, and Word Plays | |||

| | year = 1996}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=goggin>{{cite thesis |type=PhD |last=Goggin |first=Joyce |date=1997 |page=196|title=The Big Deal: Card Games in 20th-Century Fiction |publisher=University of Montréal}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=gregory>{{cite book |last1=Gregory |first1=James|author-link=James Gregory (mathematician) |title=Vera Circuli et Hyperbolæ Quadratura … |trans-title=The true squaring of the circle and of the hyperbola … |date=1667 |publisher=Giacomo Cadorino |location=Padua }} Available at: </ref> | |||

| <ref name=guicciardini>{{cite book|title=Isaac Newton on Mathematical Certainty and Method|first= Niccolò|last=Guicciardini|series=Transformations|volume=4|publisher=MIT Press|year= 2009|isbn= 9780262013178|page=10|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=U4I82SJKqAIC&pg=PA10}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=halmos>{{cite journal | url=https://www.e-periodica.ch/digbib/view?pid=ens-001%3A1970%3A16%3A%3A524#278 | author=Paul R. Halmos |author-link=Paul Halmos| title=How to Write Mathematics | journal=] | volume=16 | number=2 | pages=123–152 | year=1970 }} — </ref> | |||

| <ref name=heath>{{Cite book| last = Heath | first = Thomas |author-link=Thomas Heath (classicist)| year = 1921 | title = History of Greek Mathematics | url = https://archive.org/details/cu31924008704219 | publisher = The Clarendon Press}} See in particular Anaxagoras, ; Lunes of Hippocrates, ; Later work, including Antiphon, Eudemus, and Aristophanes, .</ref> | |||

| <ref name=heisel>{{cite book |last1=Heisel |first1=Carl Theodore|author-link=Carl Theodore Heisel |title=Behold! : the grand problem the circle squared beyond refutation no longer unsolved |date=1934 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Uqe3swEACAAJ|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=hobson>{{Cite book|last=Hobson|first= Ernest William|author-link=E. W. Hobson |year=1913|title=Squaring the Circle: A History of the Problem|publisher=Cambridge University Press|url=https://archive.org/details/squaringcirclehi00hobsuoft|pages=–35}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=hyper1>{{Cite journal| doi = 10.1007/BF03024895 | last = Jagy | first = William C. | title = Squaring circles in the hyperbolic plane | journal = ] | volume = 17 | issue = 2 | pages = 31–36 | year = 1995 | s2cid = 120481094 | url = http://zakuski.math.utsa.edu/~jagy/papers/Intelligencer_1995.pdf }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=hyper2>{{Cite book | |||

| | last = Greenberg | |||

| | first = Marvin Jay | |||

| |author-link= Marvin Greenberg | |||

| | title = Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries | |||

| | publisher = W H Freeman | |||

| | year = 2008 | |||

| | pages = 520–528 | |||

| | edition = Fourth | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-7167-9948-1 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=idioms>{{cite web|last=Ammer|first=Christine|title=Square the Circle. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of Idioms|url=http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/square%20the%20circle|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Company|access-date=16 April 2012}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=indiana>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Singmaster | first = David | author-link = David Singmaster | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/BF03024180 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 784946 | |||

| | pages = 69–72 | |||

| | title = The legal values of pi | |||

| | volume = 7 | |||

| | year = 1985| s2cid = 122137198 }} Reprinted in {{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Berggren | first1 = Lennart | |||

| | last2 = Borwein | first2 = Jonathan | |||

| | last3 = Borwein | first3 = Peter | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/978-1-4757-4217-6_27 | |||

| | edition = Third | |||

| | isbn = 0-387-20571-3 | |||

| | mr = 2065455 | |||

| | pages = 236–239 | |||

| | publisher = Springer-Verlag | location = New York | |||

| | title = Pi: a source book | |||

| | year = 2004}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=knorr>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Knorr | first = Wilbur Richard | author-link = Wilbur Knorr | |||

| | isbn = 0-8176-3148-8 | |||

| | location = Boston | |||

| | mr = 884893 | |||

| | pages = 15–16 | |||

| | publisher = Birkhäuser | |||

| | title = The Ancient Tradition of Geometric Problems | |||

| | title-link = The Ancient Tradition of Geometric Problems | |||

| | year = 1986}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=kochanski1>{{cite conference | |||

| | last = Więsław | first = Witold | |||

| | editor-last = Fuchs | editor-first = Eduard | |||

| | contribution = Squaring the circle in XVI–XVIII centuries | |||

| | contribution-url = https://dml.cz/dmlcz/401234 | |||

| | mr = 1872936 | |||

| | pages = 7–20 | |||

| | publisher = Prometheus | location = Prague | |||

| | series = Dějiny Matematiky/History of Mathematics | |||

| | title = Mathematics throughout the ages. Including papers from the 10th and 11th Novembertagung on the History of Mathematics held in Holbæk, October 28–31, 1999 and in Brno, November 2–5, 2000 | |||

| | volume = 17 | |||

| | year = 2001}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=kochanski2>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Fukś | first = Henryk | |||

| | arxiv = 1111.1739 | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/s00283-012-9312-1 | |||

| | issue = 4 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 3029928 | |||

| | pages = 40–45 | |||

| | title = Adam Adamandy Kochański's approximations of {{pi}}: reconstruction of the algorithm | |||

| | volume = 34 | |||

| | year = 2012| s2cid = 123623596 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=lambert1>{{cite journal|last=Lambert|first=Johann Heinrich|author-link=Johann Heinrich Lambert|title=Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendentes circulaires et logarithmiques |trans-title=Memoir on some remarkable properties of circular transcendental and logarithmic quantities |publication-date=1768|date=1761|journal=Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres de Berlin |volume=17|pages=265–322 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433009864251;view=1up;seq=303 |language=fr }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=lambert2>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Laczkovich | first = M. | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/00029890.1997.11990661 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | jstor = 2974737 | |||

| | mr = 1447977 | |||

| | pages = 439–443 | |||

| | title = On Lambert's proof of the irrationality of {{pi}} | |||

| | volume = 104 | |||

| | year = 1997}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=leotaud>{{Cite book|title=The Oxford Handbook of the History of Mathematics|editor-first1=Eleanor|editor-last1=Robson|editor-first2=Jacqueline|editor-last2=Stedall|publisher=Oxford University Press|date=2009|page=554|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xZMSDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA554|isbn=9780199213122}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=lindemann>{{cite journal |last1=Lindemann |first1=F.|author-link=Ferdinand von Lindemann |title=Über die Zahl π |journal=] |date=1882 |volume=20 |issue=2 |pages=213–225 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044102917051;view=1up;seq=237 |trans-title=On the number π |language=de |doi=10.1007/bf01446522|s2cid=120469397}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=longitude>{{cite book |title=Board of Longitude / Vol V / Confirmed Minutes |date=1737–1779 |publisher=Royal Observatory |location=Cambridge University Library |page=48 |url=https://cudl.lib.cam.ac.uk/view/MS-RGO-00014-00005/52 |access-date=1 August 2021}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=newton-cotes>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=OVPJ6c9_kKgC&pg=PA259|title=Correspondence of Sir Isaac Newton and Professor Cotes: Including letters of other eminent men|last1=Cotes|first1=Roger|author-link= Roger Cotes |year=1850}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=origami1>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Alperin | first = Roger C. | author-link = Roger C. Alperin | |||

| | doi = 10.2307/30037438 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 2125383 | |||

| | pages = 200–211 | |||

| | title = Trisections and totally real origami | |||

| | volume = 112 | |||

| | year = 2005| jstor = 30037438 | arxiv = math/0408159 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=origami2>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Fuchs | first = Clemens | |||

| | doi = 10.4171/EM/179 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | mr = 2824428 | |||

| | pages = 121–131 | |||

| | title = Angle trisection with origami and related topics | |||

| | volume = 66 | |||

| | year = 2011| doi-access = free | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=paradiso1>{{Cite journal| last1 = Herzman | first1 = Ronald B. | |||

| | last2 = Towsley | first2 = Gary B. | |||

| | journal = Traditio | |||

| | jstor = 27831895 | |||

| | pages = 95–125 | |||

| | title = Squaring the circle: ''Paradiso'' 33 and the poetics of geometry | |||

| | volume = 49 | |||

| | year = 1994| doi = 10.1017/S0362152900013015 | |||

| | s2cid = 155844205 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=paradiso2>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Kay | first = Richard | |||

| | date = July 2005 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/02666286.2005.10462116 | |||

| | issue = 3 | |||

| | journal = Word & Image | |||

| | pages = 252–260 | |||

| | title = Vitruvius and Dante's ''Imago dei''  | |||

| | volume = 21| s2cid = 194056860 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=pendrick>{{Cite journal| last = Pendrick | first = Gerard | |||

| | issue = 1 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | jstor = 25473619 | |||

| | pages = 105–107 | |||

| | title = Two notes on "Ulysses" | |||

| | volume = 32 | |||

| | year = 1994}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=plofker>{{cite book|page=|title=Mathematics in India|title-link=Mathematics in India (book)|first=Kim|last=Plofker|author-link=Kim Plofker|date= 2009|publisher=Princeton University Press|isbn=978-0691120676}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=ramanujan1>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Ramanujan | first = S. | author-link = Srinivasa Ramanujan | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | pages = 350–372 | |||

| | title = Modular equations and approximations to {{pi}} | |||

| | url = http://ramanujan.sirinudi.org/Volumes/published/ram06.pdf | |||

| | volume = 45 | |||

| | year = 1914}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=ramanujan2>{{cite journal | |||

| | last = Castellanos | first = Dario | |||

| | date = April 1988 | |||

| | doi = 10.1080/0025570X.1988.11977350 | |||

| | issue = 2 | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | jstor = 2690037 | |||

| | pages = 67–98 | |||

| | title = The ubiquitous {{pi}} | |||

| | volume = 61}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=schepler>{{Cite journal| last = Schepler | first = Herman C. | |||

| | journal = ] | |||

| | jstor = 3029832 | |||

| | mr = 0037596 | |||

| | pages = 165–170, 216–228, 279–283 | |||

| | title = The chronology of pi | |||

| | volume = 23 | |||

| | year = 1950| issue = 3 | |||

| | doi=10.2307/3029284}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=sestina>{{Cite journal|title=The Sestina: An Exploration of the Dynamics of Poetic Structure|first=Margaret|last=Spanos|journal=]|volume=53|issue=3|year=1978|pages=545–557|jstor=2855144|doi=10.2307/2855144|s2cid=162823092}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=tubbs>{{cite book | |||

| | last = Tubbs | first = Robert | |||

| | editor1-last = Tubbs | editor1-first = Robert | |||

| | editor2-last = Jenkins | editor2-first = Alice | |||

| | editor3-last = Engelhardt | editor3-first = Nina | |||

| | contribution = Squaring the circle: A literary history | |||

| | date = December 2020 | |||

| | doi = 10.1007/978-3-030-55478-1_10 | |||

| | mr = 4272388 | |||

| | pages = 169–185 | |||

| | publisher = Springer International Publishing | |||

| | title = The Palgrave Handbook of Literature and Mathematics| isbn = 978-3-030-55477-4 | |||

| | s2cid = 234128826 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name=wantzel>{{cite journal |last1=Wantzel |first1=L. |author-link=Pierre Wantzel|title=Recherches sur les moyens de reconnaître si un problème de géométrie peut se résoudre avec la règle et le compas |journal=] |date=1837 |volume=2 |pages=366–372 |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=nyp.33433110146044;view=1up;seq=380 |trans-title=Investigations into means of knowing if a problem of geometry can be solved with a straightedge and compass |language=fr}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ==Further reading and external links== | |||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| {{Wikisource}} | {{Wikisource}} | ||

| * {{cite web|url=http://www.cut-the-knot.org/impossible/sq_circle.shtml|title=Squaring the Circle|work=]|first=Alexander|last=Bogomolny}} | |||

| * {{cite web|last=Grime|first=James|title=Squaring the Circle|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMP9a2J4Bqw|work=Numberphile|date=25 March 2013 |publisher=]|via=YouTube}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|journal=Convergence|publisher=Mathematical Association of America|title=An Investigation of Historical Geometric Constructions|url=https://www.maa.org/press/periodicals/convergence/an-investigation-of-historical-geometric-constructions|first1=Suzanne|last1=Harper|first2=Shannon|last2=Driskell|date=August 2010}}{{Dead link|date=November 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} | |||

| * {{cite web|url=https://mathshistory.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Squaring_the_circle/|title=Squaring the circle|work=]|date=April 1999|first1=J J|last1=O'Connor|first2=E F|last2=Robertson}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|journal=Convergence|publisher=Mathematical Association of America|title=The Quadrature of the Circle and Hippocrates' Lunes|url=https://www.maa.org/press/periodicals/convergence/the-quadrature-of-the-circle-and-hippocrates-lunes|first=Daniel E.|last=Otero|date=July 2010}} | |||

| * {{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O1sPvUr0YC0|title=2000 years unsolved: Why is doubling cubes and squaring circles impossible?|first=Burkard|last=Polster|author-link=Burkard Polster|via=YouTube|work=Mathologer|date=29 June 2019 }} | |||

| {{Greek mathematics|state=collapsed}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Squaring The Circle}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:56, 15 November 2024

Problem of constructing equal-area shapes For other uses, see Squaring the circle (disambiguation), Square the Circle (disambiguation), and Squared circle (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Square peg in a round hole.

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant π |

|---|

| 3.1415926535897932384626433... |

| Uses |

| Properties |

| Value |

| People |

| History |

| In culture |

| Related topics |

Squaring the circle is a problem in geometry first proposed in Greek mathematics. It is the challenge of constructing a square with the area of a given circle by using only a finite number of steps with a compass and straightedge. The difficulty of the problem raised the question of whether specified axioms of Euclidean geometry concerning the existence of lines and circles implied the existence of such a square.

In 1882, the task was proven to be impossible, as a consequence of the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem, which proves that pi () is a transcendental number. That is, is not the root of any polynomial with rational coefficients. It had been known for decades that the construction would be impossible if were transcendental, but that fact was not proven until 1882. Approximate constructions with any given non-perfect accuracy exist, and many such constructions have been found.

Despite the proof that it is impossible, attempts to square the circle have been common in pseudomathematics (i.e. the work of mathematical cranks). The expression "squaring the circle" is sometimes used as a metaphor for trying to do the impossible.

The term quadrature of the circle is sometimes used as a synonym for squaring the circle. It may also refer to approximate or numerical methods for finding the area of a circle. In general, quadrature or squaring may also be applied to other plane figures.

History

Methods to calculate the approximate area of a given circle, which can be thought of as a precursor problem to squaring the circle, were known already in many ancient cultures. These methods can be summarized by stating the approximation to π that they produce. In around 2000 BCE, the Babylonian mathematicians used the approximation , and at approximately the same time the ancient Egyptian mathematicians used . Over 1000 years later, the Old Testament Books of Kings used the simpler approximation . Ancient Indian mathematics, as recorded in the Shatapatha Brahmana and Shulba Sutras, used several different approximations to . Archimedes proved a formula for the area of a circle, according to which . In Chinese mathematics, in the third century CE, Liu Hui found even more accurate approximations using a method similar to that of Archimedes, and in the fifth century Zu Chongzhi found , an approximation known as Milü.

The problem of constructing a square whose area is exactly that of a circle, rather than an approximation to it, comes from Greek mathematics. Greek mathematicians found compass and straightedge constructions to convert any polygon into a square of equivalent area. They used this construction to compare areas of polygons geometrically, rather than by the numerical computation of area that would be more typical in modern mathematics. As Proclus wrote many centuries later, this motivated the search for methods that would allow comparisons with non-polygonal shapes:

Having taken their lead from this problem, I believe, the ancients also sought the quadrature of the circle. For if a parallelogram is found equal to any rectilinear figure, it is worthy of investigation whether one can prove that rectilinear figures are equal to figures bound by circular arcs.

The first known Greek to study the problem was Anaxagoras, who worked on it while in prison. Hippocrates of Chios attacked the problem by finding a shape bounded by circular arcs, the lune of Hippocrates, that could be squared. Antiphon the Sophist believed that inscribing regular polygons within a circle and doubling the number of sides would eventually fill up the area of the circle (this is the method of exhaustion). Since any polygon can be squared, he argued, the circle can be squared. In contrast, Eudemus argued that magnitudes can be divided up without limit, so the area of the circle would never be used up. Contemporaneously with Antiphon, Bryson of Heraclea argued that, since larger and smaller circles both exist, there must be a circle of equal area; this principle can be seen as a form of the modern intermediate value theorem. The more general goal of carrying out all geometric constructions using only a compass and straightedge has often been attributed to Oenopides, but the evidence for this is circumstantial.

The problem of finding the area under an arbitrary curve, now known as integration in calculus, or quadrature in numerical analysis, was known as squaring before the invention of calculus. Since the techniques of calculus were unknown, it was generally presumed that a squaring should be done via geometric constructions, that is, by compass and straightedge. For example, Newton wrote to Oldenburg in 1676 "I believe M. Leibnitz will not dislike the theorem towards the beginning of my letter pag. 4 for squaring curve lines geometrically". In modern mathematics the terms have diverged in meaning, with quadrature generally used when methods from calculus are allowed, while squaring the curve retains the idea of using only restricted geometric methods.

A 1647 attempt at squaring the circle, Opus geometricum quadraturae circuli et sectionum coni decem libris comprehensum by Grégoire de Saint-Vincent, was heavily criticized by Vincent Léotaud. Nevertheless, de Saint-Vincent succeeded in his quadrature of the hyperbola, and in doing so was one of the earliest to develop the natural logarithm. James Gregory, following de Saint-Vincent, attempted another proof of the impossibility of squaring the circle in Vera Circuli et Hyperbolae Quadratura (The True Squaring of the Circle and of the Hyperbola) in 1667. Although his proof was faulty, it was the first paper to attempt to solve the problem using algebraic properties of . Johann Heinrich Lambert proved in 1761 that is an irrational number. It was not until 1882 that Ferdinand von Lindemann succeeded in proving more strongly that π is a transcendental number, and by doing so also proved the impossibility of squaring the circle with compass and straightedge.

After Lindemann's impossibility proof, the problem was considered to be settled by professional mathematicians, and its subsequent mathematical history is dominated by pseudomathematical attempts at circle-squaring constructions, largely by amateurs, and by the debunking of these efforts. As well, several later mathematicians including Srinivasa Ramanujan developed compass and straightedge constructions that approximate the problem accurately in few steps.

Two other classical problems of antiquity, famed for their impossibility, were doubling the cube and trisecting the angle. Like squaring the circle, these cannot be solved by compass and straightedge. However, they have a different character than squaring the circle, in that their solution involves the root of a cubic equation, rather than being transcendental. Therefore, more powerful methods than compass and straightedge constructions, such as neusis construction or mathematical paper folding, can be used to construct solutions to these problems.

Impossibility

The solution of the problem of squaring the circle by compass and straightedge requires the construction of the number , the length of the side of a square whose area equals that of a unit circle. If were a constructible number, it would follow from standard compass and straightedge constructions that would also be constructible. In 1837, Pierre Wantzel showed that lengths that could be constructed with compass and straightedge had to be solutions of certain polynomial equations with rational coefficients. Thus, constructible lengths must be algebraic numbers. If the circle could be squared using only compass and straightedge, then would have to be an algebraic number. It was not until 1882 that Ferdinand von Lindemann proved the transcendence of and so showed the impossibility of this construction. Lindemann's idea was to combine the proof of transcendence of Euler's number , shown by Charles Hermite in 1873, with Euler's identity This identity immediately shows that is an irrational number, because a rational power of a transcendental number remains transcendental. Lindemann was able to extend this argument, through the Lindemann–Weierstrass theorem on linear independence of algebraic powers of , to show that is transcendental and therefore that squaring the circle is impossible.

Bending the rules by introducing a supplemental tool, allowing an infinite number of compass-and-straightedge operations or by performing the operations in certain non-Euclidean geometries makes squaring the circle possible in some sense. For example, Dinostratus' theorem uses the quadratrix of Hippias to square the circle, meaning that if this curve is somehow already given, then a square and circle of equal areas can be constructed from it. The Archimedean spiral can be used for another similar construction. Although the circle cannot be squared in Euclidean space, it sometimes can be in hyperbolic geometry under suitable interpretations of the terms. The hyperbolic plane does not contain squares (quadrilaterals with four right angles and four equal sides), but instead it contains regular quadrilaterals, shapes with four equal sides and four equal angles sharper than right angles. There exist in the hyperbolic plane (countably) infinitely many pairs of constructible circles and constructible regular quadrilaterals of equal area, which, however, are constructed simultaneously. There is no method for starting with an arbitrary regular quadrilateral and constructing the circle of equal area. Symmetrically, there is no method for starting with an arbitrary circle and constructing a regular quadrilateral of equal area, and for sufficiently large circles no such quadrilateral exists.

Approximate constructions

Although squaring the circle exactly with compass and straightedge is impossible, approximations to squaring the circle can be given by constructing lengths close to . It takes only elementary geometry to convert any given rational approximation of into a corresponding compass and straightedge construction, but such constructions tend to be very long-winded in comparison to the accuracy they achieve. After the exact problem was proven unsolvable, some mathematicians applied their ingenuity to finding approximations to squaring the circle that are particularly simple among other imaginable constructions that give similar precision.

Construction by Kochański

Kochański's approximate construction

Kochański's approximate construction Continuation with equal-area circle and square; denotes the initial radius

Continuation with equal-area circle and square; denotes the initial radius

One of many early historical approximate compass-and-straightedge constructions is from a 1685 paper by Polish Jesuit Adam Adamandy Kochański, producing an approximation diverging from in the 5th decimal place. Although much more precise numerical approximations to were already known, Kochański's construction has the advantage of being quite simple. In the left diagram In the same work, Kochański also derived a sequence of increasingly accurate rational approximations for .

Constructions using 355/113

Jacob de Gelder's 355/113 construction

Jacob de Gelder's 355/113 construction Ramanujan's 355/113 construction

Ramanujan's 355/113 construction

Jacob de Gelder published in 1849 a construction based on the approximation This value is accurate to six decimal places and has been known in China since the 5th century as Milü, and in Europe since the 17th century.

Gelder did not construct the side of the square; it was enough for him to find the value The illustration shows de Gelder's construction.

In 1914, Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan gave another geometric construction for the same approximation.

Constructions using the golden ratio

Hobson's golden ratio construction

Hobson's golden ratio construction Dixon's golden ratio construction

Dixon's golden ratio construction Beatrix's 13-step construction

Beatrix's 13-step construction

An approximate construction by E. W. Hobson in 1913 is accurate to three decimal places. Hobson's construction corresponds to an approximate value of where is the golden ratio, .

The same approximate value appears in a 1991 construction by Robert Dixon. In 2022 Frédéric Beatrix presented a geometrographic construction in 13 steps.

Second construction by Ramanujan

Squaring the circle, approximate construction according to Ramanujan of 1914, with continuation of the construction (dashed lines, mean proportional red line), see animation.

Squaring the circle, approximate construction according to Ramanujan of 1914, with continuation of the construction (dashed lines, mean proportional red line), see animation. Sketch of "Manuscript book 1 of Srinivasa Ramanujan" p. 54, Ramanujan's 355/113 construction

Sketch of "Manuscript book 1 of Srinivasa Ramanujan" p. 54, Ramanujan's 355/113 construction

In 1914, Ramanujan gave a construction which was equivalent to taking the approximate value for to be giving eight decimal places of . He describes the construction of line segment OS as follows.

Let AB (Fig.2) be a diameter of a circle whose centre is O. Bisect the arc ACB at C and trisect AO at T. Join BC and cut off from it CM and MN equal to AT. Join AM and AN and cut off from the latter AP equal to AM. Through P draw PQ parallel to MN and meeting AM at Q. Join OQ and through T draw TR, parallel to OQ and meeting AQ at R. Draw AS perpendicular to AO and equal to AR, and join OS. Then the mean proportional between OS and OB will be very nearly equal to a sixth of the circumference, the error being less than a twelfth of an inch when the diameter is 8000 miles long.Incorrect constructions

In his old age, the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes convinced himself that he had succeeded in squaring the circle, a claim refuted by John Wallis as part of the Hobbes–Wallis controversy. During the 18th and 19th century, the false notions that the problem of squaring the circle was somehow related to the longitude problem, and that a large reward would be given for a solution, became prevalent among would-be circle squarers. In 1851, John Parker published a book Quadrature of the Circle in which he claimed to have squared the circle. His method actually produced an approximation of accurate to six digits.

The Victorian-age mathematician, logician, and writer Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, better known by his pseudonym Lewis Carroll, also expressed interest in debunking illogical circle-squaring theories. In one of his diary entries for 1855, Dodgson listed books he hoped to write, including one called "Plain Facts for Circle-Squarers". In the introduction to "A New Theory of Parallels", Dodgson recounted an attempt to demonstrate logical errors to a couple of circle-squarers, stating:

The first of these two misguided visionaries filled me with a great ambition to do a feat I have never heard of as accomplished by man, namely to convince a circle squarer of his error! The value my friend selected for Pi was 3.2: the enormous error tempted me with the idea that it could be easily demonstrated to BE an error. More than a score of letters were interchanged before I became sadly convinced that I had no chance.A ridiculing of circle squaring appears in Augustus De Morgan's book A Budget of Paradoxes, published posthumously by his widow in 1872. Having originally published the work as a series of articles in The Athenæum, he was revising it for publication at the time of his death. Circle squaring declined in popularity after the nineteenth century, and it is believed that De Morgan's work helped bring this about.

Even after it had been proved impossible, in 1894, amateur mathematician Edwin J. Goodwin claimed that he had developed a method to square the circle. The technique he developed did not accurately square the circle, and provided an incorrect area of the circle which essentially redefined as equal to 3.2. Goodwin then proposed the Indiana pi bill in the Indiana state legislature allowing the state to use his method in education without paying royalties to him. The bill passed with no objections in the state house, but the bill was tabled and never voted on in the Senate, amid increasing ridicule from the press.

The mathematical crank Carl Theodore Heisel also claimed to have squared the circle in his 1934 book, "Behold! : the grand problem no longer unsolved: the circle squared beyond refutation." Paul Halmos referred to the book as a "classic crank book."

In literature

The problem of squaring the circle has been mentioned over a wide range of literary eras, with a variety of metaphorical meanings. Its literary use dates back at least to 414 BC, when the play The Birds by Aristophanes was first performed. In it, the character Meton of Athens mentions squaring the circle, possibly to indicate the paradoxical nature of his utopian city.

Dante's Paradise, canto XXXIII, lines 133–135, contain the verse:

As the geometer his mind applies

To square the circle, nor for all his wit

Finds the right formula, howe'er he tries

Qual è ’l geométra che tutto s’affige

per misurar lo cerchio, e non ritrova,

pensando, quel principio ond’elli indige,

For Dante, squaring the circle represents a task beyond human comprehension, which he compares to his own inability to comprehend Paradise. Dante's image also calls to mind a passage from Vitruvius, famously illustrated later in Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man, of a man simultaneously inscribed in a circle and a square. Dante uses the circle as a symbol for God, and may have mentioned this combination of shapes in reference to the simultaneous divine and human nature of Jesus. Earlier, in canto XIII, Dante calls out Greek circle-squarer Bryson as having sought knowledge instead of wisdom.

Several works of 17th-century poet Margaret Cavendish elaborate on the circle-squaring problem and its metaphorical meanings, including a contrast between unity of truth and factionalism, and the impossibility of rationalizing "fancy and female nature". By 1742, when Alexander Pope published the fourth book of his Dunciad, attempts at circle-squaring had come to be seen as "wild and fruitless":

Mad Mathesis alone was unconfined,

Too mad for mere material chains to bind,

Now to pure space lifts her ecstatic stare,

Now, running round the circle, finds it square.

Similarly, the Gilbert and Sullivan comic opera Princess Ida features a song which satirically lists the impossible goals of the women's university run by the title character, such as finding perpetual motion. One of these goals is "And the circle – they will square it/Some fine day."

The sestina, a poetic form first used in the 12th century by Arnaut Daniel, has been said to metaphorically square the circle in its use of a square number of lines (six stanzas of six lines each) with a circular scheme of six repeated words. Spanos (1978) writes that this form invokes a symbolic meaning in which the circle stands for heaven and the square stands for the earth. A similar metaphor was used in "Squaring the Circle", a 1908 short story by O. Henry, about a long-running family feud. In the title of this story, the circle represents the natural world, while the square represents the city, the world of man.

In later works, circle-squarers such as Leopold Bloom in James Joyce's novel Ulysses and Lawyer Paravant in Thomas Mann's The Magic Mountain are seen as sadly deluded or as unworldly dreamers, unaware of its mathematical impossibility and making grandiose plans for a result they will never attain.

See also

- Mrs. Miniver's problem – Problem on areas of intersecting circles

- Round square copula – Philosophical treatment of oxymoronsPages displaying short descriptions of redirect targets

- Squircle – Shape between a square and a circle

- Tarski's circle-squaring problem – Problem of cutting and reassembling a disk into a square

References

- Ammer, Christine. "Square the Circle. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage® Dictionary of Idioms". Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ^ Bailey, D. H.; Borwein, J. M.; Borwein, P. B.; Plouffe, S. (1997). "The quest for pi". The Mathematical Intelligencer. 19 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1007/BF03024340. MR 1439159. S2CID 14318695.

- Plofker, Kim (2009). Mathematics in India. Princeton University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0691120676.

- Lam, Lay Yong; Ang, Tian Se (1986). "Circle measurements in ancient China". Historia Mathematica. 13 (4): 325–340. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(86)90055-8. MR 0875525. Reprinted in Berggren, J. L.; Borwein, Jonathan M.; Borwein, Peter, eds. (2004). Pi: A Source Book. Springer. pp. 20–35. ISBN 978-0387205717.

- ^ The construction of a square equal in area to a given polygon is Proposition 14 of Euclid's Elements, Book II.

- Translation from Knorr (1986), p. 25

- Heath, Thomas (1921). History of Greek Mathematics. The Clarendon Press. See in particular Anaxagoras, pp. 172–174; Lunes of Hippocrates, pp. 183–200; Later work, including Antiphon, Eudemus, and Aristophanes, pp. 220–235.

- Bos, Henk J. M. (2001). "The legitimation of geometrical procedures before 1590". Redefining Geometrical Exactness: Descartes' Transformation of the Early Modern Concept of Construction. Sources and Studies in the History of Mathematics and Physical Sciences. New York: Springer. pp. 23–36. doi:10.1007/978-1-4613-0087-8_2. ISBN 978-1-4612-6521-4. MR 1800805.

- Knorr, Wilbur Richard (1986). The Ancient Tradition of Geometric Problems. Boston: Birkhäuser. pp. 15–16. ISBN 0-8176-3148-8. MR 0884893.

- Guicciardini, Niccolò (2009). Isaac Newton on Mathematical Certainty and Method. Transformations. Vol. 4. MIT Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780262013178.

- Cotes, Roger (1850). Correspondence of Sir Isaac Newton and Professor Cotes: Including letters of other eminent men.

- Robson, Eleanor; Stedall, Jacqueline, eds. (2009). The Oxford Handbook of the History of Mathematics. Oxford University Press. p. 554. ISBN 9780199213122.