| Revision as of 21:18, 25 July 2008 editPi zero (talk | contribs)3,451 editsm →Development: wikilink, punctuation← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:45, 10 January 2025 edit undoHbanm (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users778 editsm ImprovementTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Major deity in Indian religions symbolising power, time, and death}} | |||

| {{Hdeity infobox| <!--Misplaced Pages:WikiProject Hindu mythology--> | |||

| {{about|the form of ]|the Supreme goddess of time and death |Mahakali|the consort of ]|Bhadrakali|the divine entity in Hinduism|Kali (demon)|other uses|Kali (disambiguation)}} | |||

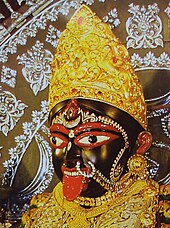

| | Image = Kali_Devi.jpg | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2015}} | |||

| | Caption = The Goddess Kali, (1770) by Richard B. Godfrey (1728 - N/A); from ] | |||

| {{Infobox deity<!--Misplaced Pages:WikiProject Hindu mythology--> | |||

| | Name = Kali | |||

| | type = Hindu | |||

| | Devanagari = काली | |||

| | name = Kali | |||

| | Sanskrit_Transliteration = Kālī | |||

| | deity_of = Goddess of Time, Death and Destruction | |||

| | Pali_Transliteration = | |||

| | abode = ]s, ]s (varies by interpretation), ] | |||

| | Tamil_script = | |||

| | consort = ] | |||

| | Affiliation = ] , ] , ] | |||

| | mantra = *''oṁ jayanti maṅgala kālī<br>bhadrakālī kapālinī<br>durgā kṣamā śivā dhātrī<br>svāhā svadhā namostute'' | |||

| | God_of = Goddess of Time, Change, Death, Destruction | |||

| | Abode = Cremation grounds | |||

| | Mantra = Om Krīm Kālyai namaḥ ,<br/> Om Kapālinaye Namah, <br/> Om Hrim Shrim Krim <br /> Parameshvari Kalike Svaha | |||

| | Weapon = Sword | |||

| | Consort = ] | |||

| | Mount = Jackal | |||

| }} | |||

| *''oṁ krīṃ kālīkāyai namaḥ'' | |||

| :''Kali redirects here. See ] for other uses.'' | |||

| | weapon = ], ] (]) | |||

| :Not to be confused with ], the personification of Kali Yuga | |||

| | image = Kali by Raja Ravi Varma.jpg | |||

| | festivals = {{hlist|]|]}} | |||

| | caption = ''Kali'' by ] | |||

| | affiliation = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | gender = Female | |||

| | member_of = The Ten ] | |||

| | day = Tuesday and Friday | |||

| | texts = ], ], ], ], ]s | |||

| | mount = Lion | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Hinduism}} | |||

| {{Saktism}} | |||

| '''Kali''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|ɑː|l|iː}}; {{langx|sa|काली}}, {{IAST3|Kālī}}), also called '''Kalika''', is a major ] in ], primarily associated with time, death and destruction. Kali is also connected with transcendental knowledge and is the first of the ten ], a group of goddess who provide liberating knowledge.<ref name="Paul"/><ref>{{cite news|url=https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/religion/rituals-puja/the-significance-of-dus-mahavidya/articleshow/68206997.cms |title=The Significance of Dus Mahavidya |website=] |access-date=4 April 2019}}</ref> Of the numerous ], Kali is held as the most famous.<ref name="Lynn"/> She is the preeminent deity in the ] tradition and the ] worship tradition, and is a central figure in the goddess-centric sects of Hinduism as well as in ].<ref name="EY"/><ref>{{Cite web |title=Dakshin Kali Khadgamala Stotra: A Hymn to the Fierce and Compassionate Goddess from Rudrayamal Tantra - Aghori Stories |url=https://aghoristories.com/tantra/dakshina-kali-khadgamala-stotra-a-hymn-to-the-fierce-and-compassionate-goddess-from-rudrayamal-tantra/?amp=1 |access-date=2024-05-06 |website=aghoristories.com| date=February 2024 }}</ref> Kali is chiefly worshipped as the Divine Mother, Mother of the Universe, and ].<ref name="Hawley">{{Cite book |last1=Hawley |first1=John Stratton |title=Sri Ramakrishna: The Spiritual Glow |last2=Wulff |first2=Donna Marie |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |year=1982 |pages=152}}</ref><ref name="Harding">{{cite book |last1=Harding |first1=Elizabeth U. |title=Kali: The Black Goddess of Dakshineswar |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4woiJbQTsBQC |year=1993 |publisher=Nicolas Hays |isbn=978-8120814509}}</ref><ref name="McDaniel">{{cite book |last1=McDaniel |first1=June |title=Offering Flowers, Feeding Skulls: Popular Goddess Worship in West Bengal |year=2004 |publisher=Oxford University Press}}</ref> | |||

| '''Kali''', also known as '''Kalika''' (]: কালী, {{IAST|Kālī}} / কালিকা {{IAST|Kālīkā}} ; ]: {{lang|sa|काली}}), is a ] associated with death and destruction. Despite her negative connotations, she is not actually the goddess of death, but rather of Time and Change. Although sometimes presented as black and violent, her earliest incarnation as a figure of annihilation still has some influence. More complex ] beliefs sometimes extend her role so far as to be the "Ultimate Reality" or '']''. She is also revered as ''Bhavatarini'' (lit. "redeemer of the universe"). Comparatively recent devotional movements largely conceive Kali as a benevolent ]. | |||

| The origins of Kali can be traced to the pre-Vedic and ] era goddess worship ] in the ].<ref name="EY">{{cite web |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Kali |title=Kali |date=31 July 2024 |website= |publisher=] |access-date= |quote=}}</ref> Etymologically the term ''Kali'' refers to one who governs time or is black. The first major appearance of Kali in the ] literature was in the sixth-century CE text '']''.<ref name="EY"/> Kali appears in many stories, with the most popular one being when she manifests as personification of goddess ]'s rage to defeat the demon ]. The terrifying iconography of Kali makes her a unique figure among the ] and symbolises her embracement and embodiment of the grim worldly realities of blood, death and destruction.<ref name="Paul"/> | |||

| Kali is represented as the consort of god ], on whose body she is often seen standing. She is associated with many other Hindu goddesses like ], ], ], ], ] and ]. She is the foremost among the Dasa-]s, ten fierce Tantric goddesses.<ref>Encyclopedia International, by Grolier Incorporated Copyright in Canada 1974. AE5.E447 1974 031 73-11206 ISBN 0-7172-0705-6 page 95 </ref> | |||

| Kali is stated to protect and bestow liberation ('']'') to devotees who approach her with an attitude of a child towards mother. Devotional songs and poems that extol the motherly nature of Kali are popular in ], where she is most widely worshipped as the Divine Mother. ] and ] traditions additionally worship Kali as the ultimate reality or '']''.<ref name="McDaniel" /> In modern times, Kali has emerged as a symbol of significance for women.<ref name="Paul"/> | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The term ''Kali'' is derived from ''Kala'', which is mentioned quite differently in ].<ref name="Jones">{{cite encyclopedia |last1=Jones |first1=Constance |last2=Ryan |first2=James D. |title=Encyclopedia of Hinduism |series=Encyclopedia of World Religions |location=New York |publisher=Infobase Publishing |date=2007 |isbn=9780816054589 |url=https://archive.org/details/wg992 |pages=220–221}}</ref> The homonym ''{{IAST|]}}'' (time) is distinct from ''kāla'' (black), but these became associated through ].<ref name="Coburn111-112"/> | |||

| ''{{IAST|Kālī}}'' is the feminine of ''{{IAST|kāla}}'' "black, dark coloured" (per ] 4.1.42). It appears as the name of a form of ] in ] 4.195, and as the name of an evil female spirit in ] 11552. | |||

| Kali is then understood as "she who is the ruler of time", or "she who is black".<ref name="Jones"/> Kālī is the goddess of time or death and the consort of Shiva.<ref name="McDermott2001">{{cite book |last1=McDermott |first1=Rachel Fell |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FeMX2g8lqkAC&pg=PA175 |title=Singing to the Goddess: Poems to Kali and Uma from Bengal |publisher=] |year=2001 |isbn=978-0198030706}}</ref> She is called Kali Mata ("the dark mother") and also ''kālī'', which can be read here either as a ] or as a description: "the dark (or black) one".<ref name="Coburn111-112">{{cite book |last1=Coburn |first1=Thomas |title=Devī-Māhātmya – Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi |year=1984 |isbn=978-81-208-0557-6}}</ref> | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| The homonymous ''{{IAST|]}}'' "appointed time", which depending on context can mean "death", is distinct from ''{{IAST|kāla}}'' "black", but became associated through ]. The association is seen in a passage from the ''{{IAST|Mahābhārata}}'', depicting a female figure who carries away the spirits of slain warriors and animals. She is called ''{{IAST|kālarātri}}'' (which Thomas Coburn, a historian of Sanskrit Goddess literature, translates as "night of death") and also ''{{IAST|kālī}}'' (which, as Coburn notes, can be read here either as a proper name or as a description "the black one").<ref>''{{IAST|Mahābhārata}}'' 10.8.64-69, cited in Coburn, Thomas; ''{{IAST|Devī-Māhātmya}} — Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition''; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1984; ISBN 81-208-0557-7 pages 111–112.</ref> | |||

| Although the word ''{{IAST|Kālī}}'' appears as early as the ], the first use of it as a proper name is in the ''Kathaka Grhya Sutra'' (19.7).<ref name="Urban">{{cite book | |||

| | last =Urban | |||

| | first = Hugh B. | |||

| | author-link= Hugh Urban | |||

| | chapter = India's Darkest Heart: Kali in the Colonial Imagination | |||

| | year = 2003 | |||

| | editor-last = McDermott | |||

| | editor-first = Rachel Fell | |||

| | editor-last2 = Kripal | |||

| | editor-first2 = Jeffrey J. | |||

| | title = Encountering Kali: In the Margins, at the Center, in the West | |||

| | publisher = University of California Press | |||

| | page = 171 | |||

| | isbn = 978-0-520-92817-6 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| Kali originated as a tantric and non-Vedic goddess. Her roots are most probably connected to the Pre-Aryan period.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Mohanty |first1=Seema |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3KyfCUvoAtoC |title=The Book of Kali |last2=Seema |date=July 2009 |publisher=Penguin Books India |isbn=978-0-14-306764-1 |language=en}}</ref> According to Indologist ], Kali's origins can be traced to the deities of the Pre-Vedic village, tribal, and mountain cultures of South Asia who were gradually appropriated and transformed by the Sanskritic traditions.<ref name="EY" /> | |||

| ==Legends== | |||

| Kali's association with blackness stands in contrast to her consort, ], whose body is covered by the white ashes of the cremation ground (Sanskrit: ''{{IAST|śmaśāna}}'') in which he meditates, and with which Kali is also associated, as ''{{IAST|śmaśāna-kālī}}''. | |||

| Her most well-known appearance is on the battlefield in the sixth century text '']''. The deity of the first chapter of ''Devi Mahatmyam'' is Mahakali, who appears from the body of sleeping ] as goddess Yoga Nidra to wake him up in order to protect ] and the world from two ] (demons), ]. When Vishnu woke up he started a war against the two asuras. After a long battle with Vishnu, the two demons were undefeated and Mahakali took the form of Mahamaya to enchant the two asuras. When Madhu and Kaitabha were enchanted by Mahakali, Vishnu killed them.<ref name="Kinsley1997">{{cite book |last1=Kinsley |first1=David |title=Tantric Visions of the Divine Feminine: The Ten Mahavidyas |publisher=Berkeley: University of California Press |year=1997 |pages=70–76}}</ref> | |||

| In later chapters, the story of two asuras who were destroyed by Kali can be found. ] attack the goddess ]. Kaushiki responds with such anger that it causes her face to turn dark, resulting in Kali appearing out of her forehead. Kali's appearance is dark blue, gaunt with sunken eyes, wearing a tiger skin ] and a ]. She immediately defeats the two asuras. Later in the same battle, the asura ] is undefeated because of his ability to reproduce himself from every drop of his blood that reaches the ground. Countless Raktabija clones appear on the battlefield. Kali eventually defeats him by sucking his blood before it can reach the ground, and eating the numerous clones. Kinsley writes that Kali represents "Durga's personified wrath, her embodied fury".<ref name="Kinsley1997" /> | |||

| ==Origin== | |||

| Other origin stories involve Parvati and Shiva. Parvati is typically portrayed as a benign and friendly goddess. The '']'' describes Shiva asking Parvati to defeat the asura ], who received a boon that would only allow a female to kill him. Parvati merges with Shiva's body, reappearing as Kali to defeat Daruka and his armies. Her bloodlust gets out of control, only calming when Shiva intervenes. The '']'' has a different version of Kali's relationship with Parvati. When Shiva addresses Parvati as Kali, "the dark blue one", she is greatly offended. Parvati performs austerities to lose her dark complexion and becomes Gauri, the golden one. Her dark sheath becomes '']'', who while enraged, creates Kali.<ref name="Kinsley1997" /> | |||

| Kali appears in the ] (section 1, chapter 2, verse 4) not explicitly as a goddess, but as the black tongue of the seven flickering tongues of ], the ] god of ].<ref>Coburn, Thomas; ''{{IAST|Devī-Māhātmya}} — Crystallization of the Goddess Tradition''; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, 1984; ISBN 81-208-0557-7 pages 110–111.</ref> However, the prototype of the figure now known as Kali appears in the ], in the form of a goddess named Raatri. Raatri is considered to be the prototype of both Durga and Kali. | |||

| In the ], Kali turns black out of rage, while battling the demons ].<ref name="Jones"/>{{rp|221}} | |||

| In the ] era, circa 200BCE–200CE, of ], a Kali-like bloodthirsty goddess named ''Kottravai'' appears in the literature of the period.{{fact|date=April 2008}} Like Kali she has dishevelled hair, inspires fear in those who approach her and feasts on battlegrounds littered with the dead. | |||

| ===Slayer of Raktabīja=== | |||

| It was the composition of the ]s in late antiquity that firmly gave Kali a place in the Hindu pantheon. Kali or Kalika is described in the ] (also known as the Chandi or the Durgasaptasati) from the ], circa 300–600CE, where she is said to have emanated from the brow of the goddess ], a slayer of demons or ], during one of the battles between the divine and anti-divine forces. In this context, Kali is considered the 'forceful' form of the great goddess Durga. Another account of the origins of Kali is found in the ], circa 1500CE, which states that she originated as a mountain tribal goddess in the north-central part of India, in the region of Mount Kalanjara (now known as ]). However this account is disputed because the legend was of later origin. | |||

| In Kāli's most famous legend, ] and her assistants, the ], wound the demon ], in various ways and with a variety of weapons in an attempt to destroy him. They soon find that they have worsened the situation for with every drop of blood that drips from Raktabīja, he reproduces a duplicate of himself. The battlefield becomes increasingly filled with his duplicates.<ref name="Kinsley1997" /> Durga summons Kāli to combat the demons. This episode is described in the '']m,'' Kali is depicted as being fierce, clad in a tiger's skin and armed with a sword and noose. She has deep, red eyes with tongue lolling out as she catches drops of Raktabīja's blood before they fall to the ground and create duplicates.<ref name="Wangu2003" /> | |||

| Kali consumes Raktabīja and his duplicates, and dances on the corpses of the slain.<ref name="Kinsley1997" /> In the ''Devi Mahatmya'' version of this story, Kali is also described as a ''Matrika'' and as a '']'' or power of ]. She is given the epithet ''{{IAST|Cāṃuṇḍā}}'' ('']''), that is, the slayer of the demons ].<ref name ="Wangu2003">{{cite book | |||

| The ] a work of late ninth or early tenth century, is one of the Upapuranas. The Kalika Purana mainly describes different manifestations of the Goddess, gives their iconographic details, mounts, and weapons. It also provides ritual procedures of worshipping Kalika. | |||

| |last1=Wangu | |||

| |first1=Madhu Bazaz | |||

| |title=Images of Indian Goddesses | |||

| |year=2003 | |||

| |publisher=Abhinav Publications | |||

| |isbn=978-81-7017-416-5}}</ref>{{rp|72}} ''Chamunda'' is very often identified with Kali and is very much like her in appearance and habit.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|241 Footnotes}} | |||

| ==Iconography and forms== | |||

| ==In Tantra== | |||

| The goddess Kali is regarded as the most famous female deity of all the numerous ].<ref name="Lynn">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Foulston |first=Lynn |editor-last1=Cush |editor-first1=Denise |editor-last2=Robinson |editor-first2=Catherine |editor-last3=York |editor-first3=Michael |chapter=ŚAKTI |page=730 |title=Encyclopedia of Hinduism |publisher=Routledge |date=2008 |isbn=978-0-7007-1267-0 |url=https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203862032/encyclopedia-hinduism-denise-cush-catherine-robinson-michael-york }}</ref> The uncommon appearance of Kali is explained as a cause of her popularity.<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|398}} Kali is iconographically depicted as a "terrifying emaciated woman"; with black skin, long tangled hair, red eyes and a long lolling tongue. She is naked barring a grim set of ornamentation: "a necklace of skulls or freshly decapitated heads, a skirt of severed arms and jewellery made from the corpses of infants." The "wildness" is a defining aspect of her character.<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|399}} The terrifying iconography of Kali is considered symbolic of her role as a protector and a bestower of freedom to devotees, of whom she shall take care of if they come to her in the "attitude of a child."<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|399}} Devotional songs and poems that glorify the motherly nature of Kali are popular in ], where she is most extensively worshipped.<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|399}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In the ], where Kali first appeared as a personification of the rage of goddess ], an aspect of Kali's character was her thirst for blood and fondness to stay at places of death and destruction.<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|399}} In original depictions, Kali was often pictured in a cremation ground or battlefield standing on the corpse of ], which symbolized her manifestation as ].<ref name=":3" /> Kali represents the goddess embracing and encompassing the grim worldly realities of "blood, death and destruction".<ref name="Paul">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Reid-Bowen |first=Paul |editor-last1=Cush |editor-first1=Denise |editor-last2=Robinson |editor-first2=Catherine |editor-last3=York |editor-first3=Michael |chapter=KĀLĪ AND CAṆḌĪ|pp=398-399 |title=Encyclopedia of Hinduism |publisher=Routledge |date=2008 |isbn=978-0-7007-1267-0 |url=https://www.taylorfrancis.com/books/mono/10.4324/9780203862032/encyclopedia-hinduism-denise-cush-catherine-robinson-michael-york }}</ref> | |||

| Goddesses play an important role in the study and practice of ] Yoga, and are affirmed to be as central to discerning the nature of reality as the male deities are. Although ] is often said to be the recipient and student of ] wisdom in the form of ''Tantras'', it is Kali who seems to dominate much of the Tantric iconography, texts, and rituals.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 122.</ref> In many sources Kali is praised as the highest reality or greatest of all deities. The ''Nirvana-tantra'' says the gods ], ], and ] all arise from her like bubbles in the sea, ceaselessly arising and passing away, leaving their original source unchanged. The ''Niruttara-tantra'' and the ''Picchila-tantra'' declare all of Kali's mantras to be the greatest and the ''Yogini-tantra'', ''Kamakhya-tantra'' and the ''Niruttara-tantra'' all proclaim Kali ''vidyas'' (manifestations of ''Mahadevi'', or "divinity itself"). They declare her to be an essence of her own form (''svarupa'') of the ''Mahadevi''.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 122–123.</ref> | |||

| The ''Kalika ]'' describes Kali as "possessing a soothing dark complexion, as perfectly beautiful, riding a lion, four-armed, holding a sword and blue lotus, her hair unrestrained, body firm and youthful".<ref name="White2000">{{cite book |last1=Gupta |first1=Sanjukta |editor-last1=White |editor-first1=David Gordon |editor-link=David Gordon White |chapter=The Worship of Kali According to the Todala Tantra |title=Tantra in Practice |year=2000 |publisher=Princeton Press |page=466 |isbn=0-691-05778-8 |ref=refWhite2000}}</ref> The goddess has two depictions: the popular ] form and the ten-armed Mahakali avatar. In both, she is described as being black in colour, though she is often seen as blue in popular Indian art. Her eyes are described as red with intoxication and rage. Her hair is disheveled, small fangs sometimes protrude out of her mouth, and her tongue is lolling. Sometimes she dons a skirt made of demon arms and a ]. Other times, she is seen wearing a tiger skin. She is also accompanied by ] and a ] while standing on the calm and prostrate Shiva, usually right foot forward to symbolize the more popular '']'' ("right-hand path"), as opposed to the more infamous and transgressive ] ("left-hand path").<ref name="Rawson">{{cite book |last1=Rawson |first1=Philip |title=The Art of Tantra |url=https://archive.org/details/tantra00phil |url-access=registration |year=1973 |publisher=Thames & Hudson}}</ref> Her mount, or '']'', is the lion.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Williams |first=George Mason |title=Handbook of Hindu mythology |date=2003 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-57607-106-9 |series=Handbooks of world mythology |location=Santa Barbara (Calif.) |pages=173}}</ref> | |||

| In the ''Mahanirvana-tantra'', Kali is one of the epithets for the primordial ''sakti'', and in one passage ] praises her: | |||

| ===Popular form=== | |||

| :''At the dissolution of things, it is Kala Who will devour all, and by reason of this He is called Mahakala , and since Thou devourest Mahakala Himself, it is Thou who art the Supreme Primordial Kalika. Because Thou devourest Kala, Thou art Kali, the original form of all things, and because Thou art the Origin of and devourest all things Thou art called the Adya [primordial Kali. Resuming after Dissolution Thine own form, dark and formless, Thou alone remainest as One ineffable and inconceivable. Though having a form, yet art Thou formless; though Thyself without beginning, multiform by the power of Maya, Thou art the Beginning of all, Creatrix, Protectress, and Destructress that Thou art.''<ref>D. Kinsley p. 122.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Kali is depicted with four arms, which symbolize the circle of creation and dissolution.<ref name=":3" /> Her left hands are depicted holding a severed head and a sword.<ref name=":3">{{Cite book |last1=Foulston |first1=Lynn |title=Hindu goddesses: beliefs and practices |last2=Abbott |first2=Stuart |date=2009 |publisher=Sussex Academic |isbn=978-1-902210-43-8 |edition= |location=Brighton |pages=34–38}}</ref> The sword signifies divine knowledge and the human head signifies human ego which must be slain by divine knowledge in order to attain ]. The right hands are usually depicted in the ] (fearlessness) and ] (blessing) ]s, which means her initiated devotees (or anyone worshipping her with a true heart) will be saved as she will guide them here and in the hereafter.<ref name="White2000" />{{rp|477}} | |||

| The figure of Kali conveys death, destruction, fear, and the consuming aspects of reality. As such, she is also a "forbidden thing", or even death itself. In the ''Pancatattva'' ritual, the ''sadhaka'' boldly seeks to confront Kali, and thereby assimilates and transforms her into a vehicle of salvation.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 124.</ref> This is clear in the work of the ''Karpuradi-stotra'', a short praise to Kali describing the ''Pancatattva'' ritual unto her, performed on cremation grounds. (''Samahana-sadhana'') | |||

| She wears a ], variously enumerated at ] (an auspicious number in Hinduism and the number of countable beads on a ] ] or rosary for repetition of ]) or 51, which represents Varnamala or the Garland of letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, ]. Hindus believe ] is a language of ], and each of these letters represents a form of energy, or a form of Kali. Therefore, she is generally seen as the mother of language, and all ]s.<ref name="White2000" />{{rp|475}} | |||

| :''He, O Mahakali who in the cremation-ground, naked, and with dishevelled hair, intently meditates upon Thee and recites Thy mantra, and with each recitation makes offering to Thee of a thousand Akanda flowers with seed, becomes without any effort a Lord of the earth. 0 Kali, whoever on Tuesday at midnight, having uttered Thy mantra, makes offering even but once with devotion to Thee of a hair of his Sakti in the cremation-ground, becomes a great poet, a Lord of the earth, and ever goes mounted upon an elephant.''<ref>D. Kinsley p. 124.</ref> | |||

| She is often depicted naked which symbolizes her being beyond the covering of ] since she is pure (''nirguna'') being-consciousness-bliss and far above Prakriti. She is shown as very dark as she is Brahman in its supreme unmanifest state. She has no permanent qualities—she will continue to exist even when the universe ends. It is therefore believed that the concepts of color, light, good, and bad do not apply to her.<ref name="White2000" />{{rp|463–488}} | |||

| The ''Karpuradi-stotra'' clearly indicates that Kali is more than a terrible, vicious, slayer of demons who serves ] or ]. Here, she is identified as the supreme mistress of the universe, associated with the five elements. In union with Lord ], who is said to be her spouse, she creates and destroys worlds. Her appearance also takes a different turn, befitting her role as ruler of the world and object of meditation.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 124–125.</ref> In contrast to her terrible aspects, she takes on hints of a more benign dimension. She is described as young and beautiful, has a gentle smile, and makes gestures with her two right hands to dispel any fear and offer boons. The more positive features exposed offer the distillation of divine wrath into a goddess of salvation, who rids the ''sadhaka'' of fear. Here, Kali appears as a symbol of triumph over death.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 125.</ref> | |||

| ===Mahakali=== | |||

| ==In Bengali tradition== | |||

| {{Main|Mahakali}} | |||

| Kali is also central figure in late medieval ]i devotional literature, with such devotees as ] (1718–75). With the exception of being associated with ] as ] consort, Kali is rarely pictured in Hindu mythology and iconography as a motherly figure until Bengali devotion beginning in the early eighteenth century. Even in Bengali tradition her appearance and habits change little, if at all.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 126.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The Tantric approach to Kali is to display courage by confronting her on cremation grounds in the dead of night, despite her terrible appearance. In contrast, the Bengali devotee appropriates Kali's teachings, adopting the attitude of a child. In both cases, the goal of the devotee is to become reconciled with death and to learn acceptance of the way things are. These themes are well addressed in Ramprasad's work.<ref>D. Kinsley p.125–126.</ref> | |||

| Mahakali (]: Mahākālī, ]: महाकाली, ]: মহাকালী, ]: મહાકાળી), literally translated as "Great Kali", is sometimes considered as a greater form of Kali, identified with the Ultimate reality of ]. It can also be used as an honorific of the Goddess Kali,.<ref name="McDaniel"/>{{rp|257}} Mahakali symbolizes absolute night and the power of time. She is depicted with five or ten heads, each with three eyes and holding different weapons. Mahakali is known as the origin of all things, her consort is ].<ref name="McDaniel" />{{rp|257}} | |||

| Ramprasad comments in many of his other songs that Kali is indifferent to his wellbeing, causes him to suffer, brings his worldly desires to nothing and his worldly goods to ruin. He also states that she does not behave like a mother should and that she ignores his pleas: | |||

| The ] mentions that Kali took the form of Mahakali at the instruction of Shiva who wanted her to destroy the world during the time of universal ].<ref name="McDaniel" />{{rp|242}} | |||

| :''Can mercy be found in the heart of her who was born of the stone? '' | |||

| :''Were she not merciless, would she kick the breast of her lord?'' | |||

| :''Men call you merciful, but there is no trace of mercy in you. Mother.'' | |||

| :''You have cut off the headset the children of others, and these you wear as a garland around your neck.'' | |||

| :''It matters not how much I call you "Mother, Mother." You hear me, but you will not listen.''<ref>D. Kinsley p. 128.</ref> | |||

| In the ten-armed form of Mahakali, she is depicted as shining like a blue stone. She has ten faces, ten feet, and three eyes for each head. She has ornaments decked on all her limbs. There is no association with Shiva.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Sankaranarayanan |first1=Sri |title=Glory of the Divine Mother: Devi Mahatmyam |publisher=Nesma Books India |year=2001 |isbn=978-8187936008 |page=127}}</ref> | |||

| To be a child of Kali, Ramprasad asserts, is to be denied of earthly delights and pleasures. Kali is said to not give what is expected. To the devotee, it is perhaps her very refusal to do so that enables her devotees to reflect on dimensions of themselves and of reality that go beyond the material world.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 128.</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| ===Dakshinakali=== | |||

| A significant portion of Bengali devotional music features Kali as its central theme and is known as ]. Mostly sung by male vocalists, today even women have taken to this form of music. One of the finest singers of Shyama Sangeet is Pannalal Bhattacharya. | |||

| ] | |||

| Dakshinakali is the most popular form of Kali in Bengal.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |last1=Harper | |||

| |first1=Katherine Anne | |||

| |last2=Brown | |||

| |first2=Robert L. | |||

| |title=The Roots of Tantra | |||

| |year=2012 | |||

| |publisher=SUNY Press | |||

| |isbn=978-0-7914-8890-4|page=53}}</ref> She is the benevolent mother, who protects her devotees and children from mishaps and misfortunes. There are various versions for the origin of the name ''Dakshinakali''. '']'' refers to the gift given to a priest before performing a ritual or to one's guru. Such gifts are traditionally given with the right hand. Dakshinakali's two right hands are usually depicted in gestures of blessing and giving of boons. One version of the origin of her name comes from the story of ], lord of death, who lives in the south (''dakshina''). When Yama heard Kali's name, he fled in terror, and so those who worship Kali are said to be able to overcome death itself.<ref name="Kinsley1998pp86-90">{{cite book | |||

| |last1=Kinsley | |||

| |first1=David R. | |||

| |title=Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=hgTOZEyrVtIC | |||

| |year=1988 | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |isbn=978-8120803947 |pages=86–90}}</ref><ref name="Dold2003" />{{rp|53–55}} | |||

| Dakshinakali is typically shown with her right foot on ]'s chest—while depictions showing Kali with her left foot on Shiva's chest depict the even more fearsome Vamakali. Vamakali is usually worshipped by non-householders.<ref name="Pravrajika Vedantaprana 2015 p.16">Pravrajika Vedantaprana, Saptahik Bartaman, Volume 28, Issue 23, Bartaman Private Ltd., 6, JBS Haldane Avenue, 700 105 (ed. 10 October 2015) p.16</ref> | |||

| == Mythology == | |||

| ===Slayer of Raktabija=== | |||

| The pose shows the conclusion of an episode in which Kali was rampaging out of control after destroying many demons. Vishnu confronted Kali in an attempt to cool her down. She was unable to see beyond the limitless power of her rage and Vishnu had to move out of her way. Seeing this the devas became more fearful, afraid that in her rampage, Kali would not stop until she destroyed the entire universe. Shiva saw only one solution to prevent Kali's endless destruction. Shiva lay down on the battlefield so that Goddess Mahakali would have to step on him. When she saw her consort under her foot, Kali realized that she had gone too far. Filled with grief for the damage she had done, her blood-red tongue hung from her mouth, calming her down. In some interpretations of the story, Shiva was attempting to receive Kali's grace by receiving her foot on his chest.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kinsley |first=David R. |editor1-last=McDermott |editor1-first=Rachel Fell |editor2-last=Kripal |editor2-first=Jeffrey J. |chapter=Kali |title=Encountering Kali: in the margins, at the center, in the West |year=2003 |publisher=University of California Press |page=36 |isbn=978-0-520-92817-6}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In Kali's most famous myth, ] and her assistants, ], wound the demon ], in various ways and with a variety of weapons, in an attempt to destroy him. They soon find that they have worsened the situation, as for every drop of blood that is spilt from Raktabija the demon reproduces a copy of himself. The battlefield becomes increasingly filled with his duplicates.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 118.</ref> Durga, in dire need of help, summons Kali to combat the demons. It is also said that Goddess Durga takes the form of Goddess Kali at this time. | |||

| According to Rachel Fell McDermott, the poets portrayed Shiva as "the devotee who falls at feet in devotion, in the surrender of his ego, or in hopes of gaining ''moksha'' by her touch." In fact, Shiva is said to have become so enchanted by Kali that he performed austerities to win her, and having received the treasure of her feet, held them against his heart in reverence.<ref name="Dold2003">{{cite book |last1=Dold |first1=Patricia |editor-last1=McDermott |editor-first1=Rachel Fell |editor2-last=Kripal |editor2-first=Jeffrey J. |chapter=Kali the Terrific and Her Tests |title=Encountering Kali: In the Margins, at the Center, in the West |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bMUJyU_C-LkC |year=2003 |publisher=University of California Press |page=54 |isbn=978-0-520-92817-6}} | |||

| The '']m'' describes: | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ''Out of the surface of her (Durga's) forehead, fierce with frown, issued suddenly Kali of terrible countenance, armed with a sword and noose. Bearing the strange ] (skull-topped staff ), decorated with a garland of skulls, clad in a tiger’s skin, very appalling owing to her emaciated flesh, with gaping mouth, fearful with her tongue lolling out, having deep reddish eyes, filling the regions of the sky with her roars, falling upon impetuously and slaughtering the great ] in that army, she devoured those hordes of the foes of the devas.''<ref>''Devi Mahatmyam'', Swami Jagadiswarananda, Ramakrishna Math, 1953.</ref> | |||

| The popularity of the worship of the Dakshinakali form of Goddess Kali is often attributed to ]. He was a noted 17th-century Bengali Tantra thinker and author of ''Tantrasara''. Devi Kali reportedly appeared to him in a dream and told him to popularize her in a particular form that would appear to him the following day. The next morning he observed a young woman making cow dung patties. While placing a patty on a wall, she stood in the ''alidha'' pose, with her right foot forward. When she saw Krishnananda watching her, she was embarrassed and put her tongue between her teeth, Agamavagisha realized that this was the divine form of maa kali he was looking for.<ref name="Dold2003" />{{rp|54}}<ref name="Sircar1998">{{cite book | |||

| Kali destroys Raktabija by sucking the blood from his body and putting the many Raktabija duplicates in her gaping mouth. Pleased with her victory, Kali then dances on the field of battle, stepping on the corpses of the slain. Her consort ] lies among the dead beneath her feet, a representation of Kali commonly seen in her iconography as ''Daksinakali'.<ref>D. Kinsley p. 118–119.</ref> | |||

| |last1=Sircar | |||

| |first1=Dineschandra | |||

| |author-link=Dineschandra Sircar | |||

| |title= The Śākta Pīṭhas | |||

| |year=1998 | |||

| |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass Publ | |||

| |isbn=978-81-208-0879-9|page=74}}</ref> Krishnananda Agamavagisha was also the guru of the Kali devotee and poet ].<ref name="Harding" />{{rp|217}} | |||

| ===Samhara Kali=== | |||

| In Devi Mahatmya version of this story, ] is also described as an Matrika and as a ] or power of ]. She is given the epithet ''{{IAST|Cāṃuṇḍā}}'' ('']'') i.e the slayer of demons Chanda and Munda.<ref name = "W72"> Wangu p. 72.</ref> Chamunda is very often identified with Kali and is very much like her in appearance and habit.<ref> Kinsley p. 241 Footnotes.</ref> | |||

| Samhara Kali, also called Vama Kali, is the embodiment of the power of destruction. The chief goddess of Tantric texts, Samhara Kali is the most dangerous and powerful form of Kali. Samhara Kali takes form when Kali steps out with her left foot holding her sword in her right hand. She is the Kali of death, destruction and is worshipped by tantrics. As Samhara Kali she gives death and liberation. According to the Mahakala Samhita, Samhara Kali is two armed and black in complexion. She stands on a corpse and holds a freshly cut head and a plate to collect the dripping blood. She is worshipped by warriors, tantrics – the followers of ].<ref name="Harding" /> | |||

| === |

===Other forms=== | ||

| Other forms of Kali popularly worshipped in Bengal include ] (form of Kali worshipped for protection against epidemics and drought), Bhadra Kali and Guhya Kali. Kali is said to have 8, 12, or 21 different forms according to different traditions. The popular forms are Adya Kali, Chintamani Kali, Sparshamani Kali, Santati Kali, ], Dakshina Kali, ], Bhadra Kali, Smashana Kali, Adharvana Bhadra Kali, Kamakala Kali, Guhya Kali, Hamsa Kali, Shyama Kali, and Kalasankarshini Kali. In ], ] is a regional form of ].<ref name="Pravrajika Vedantaprana 2015 p.16"/> | |||

| ] (A gentle form of Kali), circa 1675.<br>Painting; made in India, Himachal Pradesh, Basohli,<br>now placed in ] Museum.]] | |||

| ==Symbolism== | |||

| In her most famous pose as ''Daksinakali'', it is said that Kali, becoming drunk on the blood of her victims on the battlefield, dances with destructive frenzy. In her fury she fails to see the body of her husband Shiva who lies among the corpses on the battlefield.<ref>D.Kinsley p.119, 130</ref> Ultimately the cries of Shiva attract Kali's attention, calming her fury. As a sign of her shame at having disrespected her husband in such a fashion, Kali sticks out her tongue. However, some sources state that this interpretation is a later version of the symbolism of the tongue: in tantric contexts, the tongue is seen to denote the element (]) of ] (energy and action) controlled by ], spiritual and godly qualities.<ref>McDermott 2003</ref> | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Interpretations of the symbolic meanings of Kali's appearance vary depending on Tantric or devotional approach, and on whether one views her image in a symbolic, allegorical or mystical fashion.<ref name="Kinsley1998pp86-90" /> There are many varied depictions of the different forms of Kali. The most common form shows her with four arms and hands, showing aspects of both creation and destruction. The two right hands are often held out in blessing, one in a mudra saying "fear not" (]), the other conferring boons. Her left hands hold a severed head and blood-covered sword. The sword severs the bondage of ignorance and ego (]), represented by the severed head. One interpretation of Kali's tongue is that the red tongue symbolizes the ] nature being conquered by the white (symbolizing ]) nature of the teeth. Her blackness represents that she is '']'', beyond all qualities of nature, and transcendent.<ref name="Kinsley1998pp86-90" /><ref name="Dold2003" />{{rp|53–55}} Kali's lolling tongue is interpreted as her being angry, enraged; while many in India interpret it as "biting the tongue" in shame.<ref name="Jones"/>{{rp|222}} | |||

| One South Indian tradition tells of a dance contest between Shiva and Kali. After defeating the two demons ] and ], Kali takes residence in a forest. With fierce companions she terrorizes the surrounding area. One of Shiva's devotees becomes distracted while doing austerities and asks Shiva to rid the forest of the destructive goddess. When Shiva arrives, Kali threatens him, claiming the territory as her own. Shiva challenges her to a dance contest, and defeats her when she is unable to perform the energetic ] dance. Although here Kali is defeated, and is forced to control her disruptive habits, we find very few images or other myths depicting her in such manner.<ref>D.Kinsley p.119</ref> | |||

| The most widespread interpretation of Kali's extended tongue involve her embarrassment over the sudden realization that she has stepped on her husband's chest. Kali's sudden "modesty and shame" over that act is the prevalent interpretation among ].<ref name="Dold2003" />{{rp|53–55}} The biting of the tongue conveys the emotion of ''lajja'' or modesty, an expression that is widely accepted as the emotion being expressed by Kali.<ref name="Kali's Tongue">{{cite book |last1=Menon |first1=Usha |last2=Shweder |first2=Richard A. |title=Emotion and Culture: Empirical Studies of Mutual Influence |chapter=Kali's Tongue: Cultural Psychology and the Power of Shame in Orissa, India |editor-last=Kitayama |editor-first=Shinobu |editor2-last=Markus |editor2-first=Hazel Rose |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=American Psychological Association |date=1994 |pages=241–284}}</ref><ref name="McDaniel"/>{{rp|237}} In Bengal also, Kali's protruding tongue is "widely accepted... as a sign of speechless embarrassment: a gesture very common among Bengalis."<ref name="Dutta2011">{{cite book |author=Krishna Dutta |title=Calcutta: A Cultural and Literary History (Cities of the Imagination) |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SZq_BAAAQBAJ&pg=PT18 |year=2011 |publisher=Andrews UK Ltd |isbn=978-1-904955-87-0 |page=18}}</ref><ref name="Harding" />{{rp|xxiii}} | |||

| ===Maternal Kali=== | |||

| The twin earrings of Kali are small embryos. This is because Kali likes devotees who have childlike qualities in them.<ref name="Pravrajika Vedantaprana 2015 p.16"/> The forehead of Kali is seen to be as luminous as the full moon and eternally giving out ambrosia.<ref name="Pravrajika Vedantaprana 2015 p.16"/> | |||

| Another myth depicts the infant Shiva calming Kali, instead. In this similar story, Kali again defeated her enemies on the battlefield and began to dance out of control, drunk on the blood of the slain. To calm her down and to protect the stability of the world, Shiva is sent to the battlefield, as an infant, crying aloud. Seeing the child's distress, Kali ceases dancing to take care of the helpless infant. She picks him up, kisses his head, and proceeds to breast feed the infant Shiva.<ref>D.Kinsley p.131</ref> This myth depicts Kali in her benevolent, maternal aspect; something that is revered in Hinduism, but not often recognized in the West. | |||

| Kali is often shown standing with her right foot on Shiva's chest. This represents an episode where Kali was out of control on the battlefield, such that she was about to destroy the entire universe. Shiva pacified her by laying down under her foot to pacify and calm her. Shiva is sometimes shown with a blissful smile on his face.<ref name="Dold2003" />{{rp|53–55}} She is typically shown with a garland of severed heads, often numbering fifty. This can symbolize the letters of the Sanskrit alphabet and therefore as the primordial sound of ] from which all creation proceeds. The severed arms which make up her skirt represent her devotee's karma that she has taken on.<ref name="Kinsley1998pp86-90" /> | |||

| ] of Mahakali displaying ten hands holding the signifiers of various Devas]] | |||

| There are several interpretations of the symbolism behind the commonly represented image of Kali standing on Shiva's supine form. A common interpretation is that Shiva symbolizes '']'', the universal unchanging aspect of reality, or pure consciousness. Kali represents '']'', nature or matter, sometimes seen as having a feminine quality of creation of life. The merging of these two qualities represent ultimate reality.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|88}} | |||

| ===Mahakali=== | |||

| {{main|Mahakali}} | |||

| A tantric interpretation sees Shiva as consciousness and Kali as power or energy. Consciousness and energy are dependent upon each other, since Shiva depends on Shakti, or energy, in order to fulfill his role in creation, preservation, and destruction. In this view, without Shakti, Shiva is a corpse—unable to act.<ref name="Dold2003"/>{{rp|53}} | |||

| ''Mahakali'' (]: Mahākālī, ]: महाकाली), literally translated as ''Great Kali'', is sometimes considered as greater form of Kali, identified with the Ultimate reality ]. It can also simply be used as an honorific of the Goddess ], signifying her greatness by the prefix "Mahā-". Mahakali, in ], is etymologically the feminized variant of ] or ''Great Time'' (which is interpreted also as '']''), an epithet of the God Shiva in Hinduism. Mahakali is the presiding Goddess of the first episode of ]. Here she is depicted as Devi in her universal form as ]. Here Devi serves as the agent who allows the cosmic order to be restored. | |||

| == |

==Worship== | ||

| ===Mantras=== | |||

| ], ], ]; along with her ].]] | |||

| Kali is closely associated with transcendent knowledge and is regarded as the first of the ten ]s, an amalgamation of goddesses who provide liberating knowledge.<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|399}} Kali is primarily worshipped in the ] worship tradition. The closest way of direct worship is to the forms of ] or ] (Bhadra in Sanskrit means 'gentle'). One mantra for Kali worship is:<ref name="Chawdri">{{cite book | |||

| |last=Chawdhri | |||

| |first=L.R. | |||

| |title=Secrets of Yantra, Mantra and Tantra | |||

| |year=1992 | |||

| |publisher=Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| {{verse translation|lang=sa|italicsoff=y | |||

| Kali is portrayed mostly in two forms: the popular four-armed form and the ten-armed Mahakali form. In both of her forms, she is described as being black in color but is most often depicted as blue in popular Indian art. Her eyes are described as red with intoxication and in absolute rage, Her hair is shown disheveled, small fangs sometimes protrude out of Her mouth and Her tongue is lolling. She is often shown naked or just wearing a skirt made of human arms and a garland of human heads. She is also accompanied by ] and a jackal while standing on a seemingly dead Shiva, usually right foot forward to symbolize the more popular ] or right-handed path, as opposed to the more infamous and transgressive ] or left-handed path.<ref>''The Art of Tantra'', Philip Rawson, Thames & Hudson, 1973</ref> | |||

| |सर्वमङ्गलमाङ्गल्ये शिवे सर्वार्थसाधिके । शरण्ये त्र्यम्बके गौरि नारायणि नमोऽस्तु ते ॥ | |||

| ॐ जयंती मंगला काली भद्रकाली कपालिनी । दुर्गा क्षमा शिवा धात्री स्वाहा स्वधा नमोऽस्तुते ॥ | |||

| |Sarvamangal-māngalyē śivē sarvārthasādhikē. Śaraṇyē tryambakē Gauri nārāyaṇi namō'stu tē. | |||

| Oṃ jayantī mangala kālī bhadrakālī kapālinī . Durgā kṣamā śivā dhātrī svāhā svadhā namō'stutē. | |||

| ॐ काली काली महाकाली कालिके परमेश्वरी । सर्वानन्दकरी देवी नारायणि नमोऽस्तुते ।। | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Tantra=== | |||

| In the ten armed form of Mahakali she is depicted as shining like a blue stone. She has ten faces and ten feet and three eyes. She has ornaments decked on all her limbs. There is no association with Siva.<ref>Sankaranarayanan. S. Devi Mahatmya. p 127</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In Tantrism the cause of reality is the mutual interaction between male and female or Shiva and Shakti. As a result, goddesses play an important role in the study and practice of ] Yoga and are essential in understanding the nature of reality.<ref name="Kinsley1997" /> Kali is often mentioned in Tantric iconography, texts and rituals even though ] received ]'s wisdom in the form of Tantras.<ref name="Kinsley1997" /> Kali is revered are the highest reality or greatest of all deities in many Tantric texts. The ''Niruttara-tantra'' and the ''Picchila-tantra'' state that among all mantras Kali's mantras are the greatest. The ''Kdmadd-tantra'' mentions that Kali is ''sacciddnanda'' or imperishable bliss and Brahman. In other texts like the''Yogini-tantra'', ''Kamakhya-tantra'' and the ''Niruttara-tantra'' Kali is referred to as an essential form of ].<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|122–124}} | |||

| The Kalika Purana describes Kali as possessing a soothing dark complexion, as perfectly beautiful, riding a lion, four armed, holding a sword and blue lotuses, her hair unrestrained, body firm and youthful.<ref> Tantra in Practice, edited by David Gordon White, (ISBN 81-208-1778-8] p466</ref> | |||

| In Tantric practice, Kali's figure represents death itself. The ''Karpuradi-stotra,'' dated to approximately 10th century CE'','' describes the ''Pancatattva'' ritual which is performed on cremation grounds (''Samahana-sadhan''). It states that a '']'' that meditates on the terrible aspects of Kali's form and confronts her can attain salvation.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|122–124}} | |||

| In spite of her seemingly terrible form, Kali is often considered the kindest and most loving of all the Hindu goddesses, as she is regarded by her devotees as the Mother of the whole Universe. And, because of her terrible form she is also often seen as a great protector. | |||

| When the ] saint ] once asked a devotee why one would prefer to worship Mother over him, this devotee rhetorically replied, “Maharaj, when they are in trouble your devotees come running to you. But, where do you run when you are in trouble?”<ref>''Sri Ramakrishna (The Great Master)'', Swami Saradananda, Ramakrishna Math,1952,page624, ''Sri Ramakrishna: The Spiritual Glow'', Kamalpada Hati, P.K. Pramanik, Orient Book Co., 1985, pages 17-18</ref> | |||

| The ''Karpuradi-stotra'' also describes Kali's gentler form that is young, with a smiling face and with two right hands to dispel fear and offer boons. She is also described as the supreme being of the universe. In this benign form, Kali becomes the goddess who grants salvation when fear is overcome and goes from being a symbol of death to being a symbol of triumph over death.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|124–125}} | |||

| According to Ramakrishna darkness is Ultimate Mother or Kali: | |||

| ===In Bengali tradition=== | |||

| ''My Mother is the principle of consciousness. She is Akhanda Satchidananda; | |||

| ], worshipped in ].]] | |||

| ''indivisible Reality, Awareness, and Bliss. The night sky between the stars is perfectly black. | |||

| ] | |||

| ''The waters of the ocean depths are the same; The infinite is always mysteriously dark. | |||

| ''This inebriating darkness is my beloved Kali. | |||

| Kali is a central figure in late medieval ] devotional literature, with such notable devotee poets as ] (1769–1821) and ] (1718–1775). With the exception of being associated with ] as ]'s consort, Kāli is rarely pictured in Hindu legends and iconography as a motherly figure until Bengali devotions beginning in the early eighteenth century. Even in Bengāli tradition her appearance and habits change little, if at all.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|126}} | |||

| ''-Sri Ramakrishna | |||

| The Tantric approach to Kāli is to display courage by confronting her on cremation grounds in the dead of night, despite her terrible appearance. In contrast, the Bengali devotee adopts the attitude of a child, coming to love her unreservedly. In both cases, the goal of the devotee is to become reconciled with death and to learn acceptance of the way that things are. These themes are addressed in Rāmprasād's work.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|125–126}} Rāmprasād comments in many of his other songs that Kāli is indifferent to his wellbeing, causes him to suffer, brings his worldly desires to nothing and his worldly goods to ruin. He also states that she does not behave like a mother should and that she ignores his pleas.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|128}} | |||

| Throughout her history artists the world over have portrayed Kali in myriad poses and settings, some of which stray far from the popular description, and are sometimes even graphically sexual in nature. Given the popularity of this Goddess, artists everywhere will continue to explore the magnificence of Kali’s iconography. This is clear in the work of such contemporary artists as ], and ], who sometimes take great liberties with the traditional, accepted symbolism, but still demonstrate a true reverence for the ] sect. | |||

| To be a child of Kāli, Rāmprasād asserts, is to be denied of earthly delights and pleasures. Kāli is said to refrain from giving that which is expected. To the devotee, it is perhaps her very refusal to do so that enables her devotees to reflect on dimensions of themselves and of reality that go beyond the material world.<ref name="Kinsley1997" />{{rp|128}} | |||

| ===Popular form=== | |||

| A significant portion of Bengali devotional music features Kāli as its central theme and is known as ].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Multani |first1=Angelie |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qsDGEAAAQBAJ&dq=shyama+sangeet+in+bengali+tradition&pg=PT50 |title=From Canon to Covid: Transforming English Literary Studies in India. Essays in Honour of GJV Prasad |last2=Pal |first2=Swati |last3=Saha |first3=Nandini |last4=Shakil |first4=Albeena |last5=Ghosh |first5=Arjun |date=2023-08-31 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-1-000-89220-8 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Classic depictions of Kali share several features, as follows: | |||

| Kāli is especially venerated in the festival of ] in eastern India – celebrated when the new moon day of ] month coincides with the festival of ]. The practice of animal sacrifice is still practiced during Kali Puja in Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, though it is rare outside of those areas. The ]s where this takes place involves the ritual slaying of goats, chickens and sometimes male water buffalos. Throughout India, the practice is becoming less common.<ref name="Fuller Christopher John 2004 83">{{cite book|last=J. Fuller|first= C.|title=The Camphor Flame: Popular Hinduism and Society in India |edition=Revised|year=2004|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-691-12048-5 |page=83|quote=Animal sacrifice is still practiced widely and is an important ritual in popular Hinduism|id= {{ASIN|069112048X|country=uk}}}}</ref> The rituals in eastern India temples where animals are killed are generally led by ] priests.<ref name="Fuller Christopher John 2004 83"/>{{rp|84, 101–104}} A number of ] ] specify the ritual for how the animal should be killed. A Brahmin priest will recite a mantra in the ear of the animal to be sacrificed, in order to free the animal from the cycle of life and death. Groups such as People for Animals continue to protest animal sacrifice based on court rulings forbidding the practice in some locations.<ref>{{cite book |last1=McDermottb|first1=Rachel Fell |title=Revelry, rivalry, and longing for the goddesses of Bengal: the fortunes of Hindu festivals |date=2011 |publisher=] |location=New York; Chichester |isbn=978-0-231-12918-3 |page=205 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ggBeH_lmUu8C&pg=PR10 |access-date=17 December 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Kali's most common four armed iconographic image shows each hand carrying variously a ], a ] (trident), a severed head and a bowl or skull-cup (]) catching the blood of the severed head. | |||

| ===In Tantric Buddhism=== | |||

| Two of these hands (usually the left) are holding a sword and a severed head. The Sword signifies Divine Knowledge and the Human Head signifies human Ego which must be slain by Divine Knowledge in order to attain ]. The other two hands (usually the right) are in the ] and ] ]s or blessings, which means her initiated devotees (or anyone worshiping her with a true heart) will be saved as she will guide them here and in the hereafter.<ref>''Tantra in Practice'', David Gordon White, Princeton Press, 2000, page 477</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Tantric Kali cults such as the Kaula and Krama had a strong influence on ], as can be seen in fierce-looking ]s and ]s such as ] and Krodikali.<ref>{{Cite book |last=English |first=Elizabeth |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50234984 |title=Vajrayoginī: her visualizations, rituals & forms: a study of the cult of Vajrayoginī in India |publisher=Wisdom Publications |year=2002 |isbn=0-86171-329-X |edition=1st Wisdom |location=Boston |pages=38–40 |oclc=50234984}}</ref> | |||

| In Tibet, Krodikali (alt. Krodhakali, Kālikā, Krodheśvarī, Krishna Krodhini) is known as ''Tröma Nagmo'' ({{langx|xct|ཁྲོ་མ་ནག་མོ་}}, ]: {{lang|bo-Latn|khro ma nag mo}}, English: "The Black Wrathful Lady").<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080821222811/http://www.himalayanart.org/pages/vajrayogini/index.html |date=21 August 2008 }} Himalayan Art Resources</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/490.html|title=Vajrayogini (Buddhist Deity) – Krodha Kali (Wrathful Black Varahi) |work=HimalayanArt}}</ref> She features as a key deity in the practice tradition of ] founded by ] and is seen as a fierce form of ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Simmer-Brown |first=Judith |author-link=Judith Simmer-Brown |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/54964040 |title=Dakini's warm breath: the feminine principle in Tibetan Buddhism |year=2002 |isbn=1-57062-920-X |edition=1st paperback |location=Boulder |publisher=Shambhala |pages=146 |oclc=54964040}}</ref> Other similar fierce deities include the dark blue Ugra Tara and the lion-faced ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Shaw |first=Miranda Eberle |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62342823 |title=Buddhist goddesses of India |publisher=Princeton University Press |year=2006 |isbn=0-691-12758-1 |location=Princeton |pages=340, 426|oclc=62342823}}</ref> | |||

| She has a garland consisting of human heads, variously enumerated at ] (an auspicious number in Hinduism and the number of countable beads on a ] ] or rosary for repetition of ]) or 51, which represents ] or the Garland of letters of the Sanskrit alphabet, ]. Hindus believe ] is a language of ], and each of these letters represents a form of energy, or a form of Kali. Therefore she is generally seen as the mother of language, and all ].<ref>''Tantra in Practice'', David Gordon White, Princeton Press, 2000, page 475</ref> | |||

| ===In Sinhala Buddhism=== | |||

| She is often depicted naked which symbolizes her being beyond the covering of ] since she is pure (nirguna) being-consciousness-bliss and far above prakriti. She is shown as very dark as she is brahman in its supreme unmanifest state. She has no permanent qualities -- she will continue to exist even when the universe ends. It is therefore believed that the concepts of color, light, good, bad do not apply to her -- she is the pure, un-manifested energy, the ].<ref>''Tantra in Practice'', David Gordon White, Princeton Press, 2000, page 463-488</ref> | |||

| In Sri Lanka, Kali is venerated and called upon by Buddhists and Hindus. She is a type of mother goddess, sometimes invoked to fight disease,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Three aspects of the 'Dhammika Paniya' controversy |url=https://www.dailymirror.lk/opinion/Three-aspects-of-the--%E2%80%98Dhammika-Paniya%E2%80%99--controversy/172-202661}}</ref> and a maid of the Goddess ].<ref name=":0" /> In Sinhala Buddhism, her origin is explained through her arriving at Munneśvaram from South India, eating humans, and attempting to eat Pattini, who instead tames her.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ===Mahakali form=== | |||

| ] | |||

| She is regarded as having seven forms; Bhadrakāli (who is associated with business and gold trade, and prominently worshipped at the Tamil Hindu ] temple, though over 80% of its patrons are Sinhala Buddhists. Bhadrakāli priests here interpret her tongue as symbolizing revenge, rather than embarrassment, and she tramples the demon of ignorance<ref name=":2">{{Cite journal |last=Bastin |first=Rohan |date=September 1996 |title=The Regenerative Power of Kali Worship in Contemporary Sinhala Buddhism |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/23171698 |journal=Social Analysis: The International Journal of Anthropology|issue=40 |pages=59–94 |jstor=23171698 }}</ref>), Mahābhadrakāli, Pēnakāli, Vandurukāli (Hanumāpatrakāli), Rīrikāli, Sohonkāli, and Ginikāli.<ref name=":0" /> These forms are subordinate to Kāliammā (the mother of Kāli). Red flowers, silver coins, blood, and oil lamps with mustard oil are offered to her, and as Pattini's servant, she accepts offerings on her behalf.<ref name=":1">{{Cite journal |last=Hewamanage |first=Wimal |date=January 2018 |title=The History of the Kāli Cult and its Implications in Modern Sri Lankan Buddhist Culture |journal=Alternative Spirituality and Religion Review|volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=246–256 |doi=10.5840/asrr2018111353 }}</ref> Sohonkāli is the form venerated in one of her most popular temples, the Mōdara Kāli temple in ].<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |title=Kali is not alien to Sinhala-Buddhism |date=27 December 2020 |url=https://dailyexpress.lk/commentary/5609/}}</ref> | |||

| Kali is depicted in the Mahakali form as having ten heads, ten arms, and ten legs. Each of her ten hands is carrying a various implement which vary in different accounts, but each of these represent the power of one of the ]s or Hindu Gods and are often the identifying weapon or ritual item of a given Deva. The implication is that Mahakali subsumes and is responsible for the powers that these deities possess and this is in line with the interpretation that Mahakali is identical with Brahman. While not displaying ten heads, an "ekamukhi" or one headed image may be displayed with ten arms, signifying the same concept: the powers of the various Gods come only through Her ]. | |||

| Her worship in Sri Lanka dates back to at least the 9th century CE, and ] created the ] in the 13th century based on an older 5th century work, which actively recontextualizes Kali in a Buddhist context,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Sri Kali and Sri Lanka |url=http://www.srilankaguardian.org/2011/12/sri-kali-and-sri-lanka.html?m=1}}</ref> exploring the nature of violence and vengeance and how they trap people in cycles until justification, guilt, and good and evil become irrelevant.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Thera |first=Dharmasena |title=The Jewels of the Doctrine |year=1991 |publisher=SUNY Press |isbn=0-7914-0489-7 |language=English |translator-last=Obeyesekere |translator-first=Ranjini}}</ref> Kali has been seen as both a demon (though a tamed one, thanks to Pattini<ref name=":2" />) and a goddess in Sri Lanka.<ref name=":1" /> She and mythical Sinhala Buddhist kings both use demonic fury as a necessary condition of conquest.<ref name=":2" /> | |||

| ===Shiva in Kali iconography=== | |||

| Yantras are used in relation to her, sourced from the ], later Buddhist ] chants, and from non-Buddhist yantras and mantras. The Sādhakayantra is popular, and its corresponding mantra includes Arabic words and Islamic concepts.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| In both these images she is shown standing on the prone, inert or dead body of Shiva. There is a mythological story for the reason behind her standing on what appears to be Shiva’s corpse, which translates as follows: | |||

| ===Worship in the Western world=== | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| ====Theorized early worship==== | |||

| Once Kali had destroyed all the demons in battle, she began a terrific dance out of the sheer joy of victory. All the worlds or ] began to tremble and sway under the impact of her dance. So, at the request of all the Gods, Shiva himself asked her to desist from this behavior. However, she was too intoxicated to listen. Hence, Shiva lay like a corpse among the slain demons in order to absorb the shock of the dance into himself. When Kali eventually stepped upon her husband she realized her mistake and bit her tongue in shame.<ref>''Hindu Gods & Goddesses'', Swami Harshananda, Ramakrishna Math, 1981, pages 116-117</ref> | |||

| A form of Kali worship may have already been transmitted to the west in Medieval times by the wandering ]. A few authors have drawn parallels between Kali worship and the ceremonies of the annual pilgrimage in honor of ], also known as ''Sara-la-Kali'' ("Sara the Black", {{langx|rom|Sara e Kali}}), held at ], a place of ] for Roma in the ], in southern France.<ref>{{Cite book |last=McDowell |first=Bart |title=Gypsies: Wanderers of the World |pages=38–57}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Fonseca |first=Isabel |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/32387216 |title=Bury me standing: the Gypsies and their journey |others=Mazal Holocaust Collection, David Lindroth Inc. |year=1995 |isbn=0-679-40678-6 |edition=1st |location=New York |publisher=Alfred A. Knopf |pages=106–107 |oclc=32387216}}</ref> ] (2001) notes that the similarities in the ceremonies performed at the shrine if Sainte Sara (called Sara e Kali in Romani) indicate that Kali/Durga worship have been incorporated to a Christian figure.<ref name="McDermott1998p281-305" /> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| ====In modern times==== | |||

| The ] interpretation of Kali standing on top of her husband is as follows: | |||

| An academic study of modern-day western Kali enthusiasts noted that, "as shown in the histories of all cross-cultural religious transplants, Kali devotionalism in the West must take on its own indigenous forms if it is to adapt to its new environment."<ref name="McDermott1998p281-305">{{cite book | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| | last =McDermott | |||

| The Shiv ] (Divine Consciousness as Shiva) is inactive, while the ] tattava (Divine Energy as Kali) is active. Shiva, or ] represents ], the Absolute pure consciousness which is beyond all names, forms and activities. Kali, on the other hand, represents the potential (and manifested) energy responsible for all names, forms and activities. She is his Shakti, or creative power, and is seen as the substance behind the entire content of all consciousness. She can never exist apart from Shiva or act independently of him, i.e., Shakti, all the matter/energy of the universe, is not distinct from Shiva, or Brahman, but is rather the dynamic power of Brahman.<ref>''Tantra (The Path of Ecstasy)'', Georg Feuerstein, Shambhala, 1998, pages 70-84, ''Shakti and Shâkta'', Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), Oxford Press/Ganesha & Co., 1918</ref> | |||

| | first = Rachel Fell | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| | chapter = The Western Kali | |||

| | editor-last = Hawley | |||

| | editor-first = John Stratton | |||

| | title = Devi: Goddesses of India | |||

| | publisher = Motilal Banarsidass | |||

| | date = 1998 | |||

| |pages=281–305}}</ref> Rachel Fell McDermott, Professor of Asian and Middle Eastern Cultures at ] and author of several books on Kali, has noted the evolving views in the West regarding Kali and her worship. In 1998 McDermott wrote that feminists and New Age spiritualists are drawn to Kali because they perceive her to be a symbol of repressed female power, sexuality, and healing but that this is a misinterpretation which stems from a lack of knowledge about Hindu religious tradition.<ref name="McDermott1998p281-305" /> By 2003, she amended this view stating that cross-cultural borrowing should be done thoughtfully and is natural due to religious globalization. She further stated that Kali enthusiasts since the early 1990s had sought to take on a more informed approach by incorporating more Indian perspective of her character than feminist and New Age interpretations.<ref name="McDermott1998p281-305" /> | |||

| The emergence of Kali in the modern times as an image of significance for many women, both Hindu and non-Hindu, has been noteworthy.<ref name="Paul"/>{{rp|399}} Since the late twentieth century, various ]s in the West have associated Kali with ].<ref name="EY" /> ] religious and spiritual movements have found in the iconographic representations and mythological stories of Kali an inspiration for ] and ].<ref name="EY" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| ====In Réunion==== | |||

| While this is an advanced concept in ] Shaktism, it also agrees with the ] ] philosophy of ], popularly known as ] and associated most famously with ]. There is a colloquial saying that "Shiva without Shakti is Shava" which means that without the power of action (Shakti) that is Mahakali (represented as the short "i" in Devanagari) Shiva (or consciousness itself) is inactive; Shava means ] in Sanskrit and the play on words is that all Sanskrit consonants are assumed to be followed by a short letter "a" unless otherwise noted. The short letter "i" represents the female power or Shakti that activates Creation. This is often the explanation for why She is standing on Shiva, who is either Her husband and complement in ] or the Supreme Godhead in ]. | |||

| In ], an island territory of France in the Indian Ocean, veneration for Saint ] ({{Langx|fr|Saint Expédit}}) is very popular. The ] have Tamil ancestry but are, at least nominally, Catholics. | |||

| To properly understand this complex Tantric symbolism it is important to remember that the meaning behind Shiva and Kali does not stray from the non-dualistic parlance of ] or the ]. According to both the ] and ] Tantras, there are two distinct ways of perceiving the same absolute reality. The first is a transcendental plane which is often described as static, yet infinite. It is here that there is no matter, there is no universe and only consciousness exists. This form of reality is known as Shiva, the absolute ] -- existence, knowledge and bliss. The second is an active plane, an immanent plane, the plane of matter, of ], i.e., where the illusion of ] and the appearance of an actual universe does exist. This form of reality is known as Kali or Shakti, and (in its entirety) is still specified as the same Absolute ]. It is here in this second plane that the universe (as we commonly know it) is experienced and is described by the Tantric seer as the play of Shakti, or God as Mother Kali.<ref>''Tantra in Practice'', David Gordon White, Princeton Press, 2000, page 463-488, ''Shakti and Shâkta'', Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), Oxford Press/Ganesha & Co., 1918</ref> | |||

| The saint is identified with Kali.<ref name="Suryanarayan">{{cite journal |last1=Suryanarayan |first1=V. |title=Tamils In Re-Union: Losing Cultural Identity – Analysis |journal=Eurasia Review |date=12 October 2018 |url=https://www.eurasiareview.com/12102018-tamils-in-re-union-losing-cultural-identity-analysis/ |access-date=3 March 2021 |language=en |quote=Saint Expedit, worshipped locally, is identified with Goddess Kali.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Comparative scholarship== | |||

| ] (the terrible form of Shiva) in Union, 18th century, Nepal]] | |||

| Scholar Marvin H. Pope in 1965 argues that the ] goddess Kali, who is first attested in the 7th century CE, shares some characteristics with some ancient Near Eastern goddesses, such as wearing a necklace of heads and a belt of severed hands like ], and drinking blood like the Egyptian goddess ] and that therefore that her character might have been influenced by them.{{sfn|Pope|Röllig|1965|page=239}} | |||

| === Levantine Anat === | |||

| From a Tantric perspective, when one meditates on reality at rest, as absolute pure consciousness (without the activities of creation, preservation or dissolution) one refers to this as Shiva or Brahman. When one meditates on reality as dynamic and creative, as the Absolute content of pure consciousness (with all the activities of creation, preservation or dissolution) one refers to it as Kali or Shakti. However, in either case the yogini or yogi is interested in one and the same reality -- the only difference being in name and fluctuating aspects of appearance. It is this which is generally accepted as the meaning of Kali standing on the chest of Shiva.<ref>''Tantra (The Path of Ecstasy)'', Georg Feuerstein, Shambhala, 1998, pages 70-84, ''Shakti and Shâkta'', Arthur Avalon (Sir John Woodroffe), Oxford Press/Ganesha & Co., 1918</ref> | |||

| The Bronze Age epic cycles of the ]ine city of ] include a myth according to which the warrior goddess ] started attacking warriors, with the text of the myth describing the goddess as gloating and her heart filling with joy and her liver with laughter while attaching the heads of warriors to her back and girding hands to her waist{{sfn|Pope|1977|pages=606–607}} until she is pacified by a message of peace sent by her brother and consort, the god ].{{sfn|Pope|1977|page=601}} | |||

| The Hindu goddess Kali similarly wore a necklace of severed heads and a girdle of severed hands, and was pacified by her consort, Śiva, throwing himself under her feet. The sickle sword wielded by Kali might also have been connected to similar sickle swords used in ] ].{{sfn|Pope|1977|pages=608}} | |||

| Although there is often controversy surrounding the images of divine copulation, the general consensus is benign and free from any carnal impurities in its substance. In Tantra the human body is a symbol for the microcosm of the universe; therefore sexual process is responsible for the creation of the world. Although theoretically Shiva and Kali (or Shakti) are inseparable, like fire and its power to burn, in the case of creation they are often seen as having separate roles. With Shiva as male and Kali as female it is only by their union that creation may transpire. This reminds us of the ] and ] doctrine of ] wherein ]- ] has no practical value, just as without prakrti, purusa is quite inactive. This (once again) stresses the interdependencies of Shiva and Shakti and the vitality of their union.<ref>''Impact of Tantra on Religion & Art'', T. N. Mishra, D.K. Print World, 1997,V</ref> | |||

| === Egyptian Sekhmet === | |||

| ] proposed that Kali standing on the dead ] or Shava (Sanskrit for dead body) symbolised the helplessness of a person undergoing the changing process (] and ]) in the body conducted by the ] ].<ref name="bio1">Krishna, Gopi (1993)''Living with Kundalini'': (Shambhala, 1993 ISBN 0877739471)</ref> | |||

| According to an ]ian myth, called {{transliteration|en|The Deliverance of Mankind from Destruction}}, the ancient Egyptian supreme god, the Sun-god ], suspected that mankind was plotting against him, and so he sent the goddess ], who was the incarnation of his violent feminine aspect, the ], to destroy his enemies.{{sfn|Pope|1977|pages=607–608}} | |||

| Furthermore, Hathor appeared as the lion-goddess ] and carried out Ra's orders until she became so captured by her blood-lust that she would not stop despite Ra himself becoming distressed and wishing an end to the killing. Therefore, Ra concocted a ruse whereby a plain was flooded with beer which had been dyed red, which Sekhmet mistook for blood and drank until she became too inebriated to continue killing, thus saving humanity from destruction.{{sfn|Pope|1977|pages=607–608}} | |||

| ==Development== | |||

| Similarly, while killing demons, Kālī became ecstatic with the joy of battle and slaughter and refused to stop, so that the ] feared she would destroy the world, and she was stopped through ruse when her consort Śiva threw himself under her feet.{{sfn|Pope|1977|pages=608}} | |||

| In the later traditions, Kali has become inextricably linked with Shiva. The unleashed form of Kali often becomes wild and uncontrollable, and only Shiva is able to tame her. This is both because she is often a transformed version of one of his consorts and because he is able to match her wildness. ] | |||

| The ancient text of Kali Kautuvam describes her competition with Shiva in dance, from which the sacred 108 ]s appeared. Shiva won the competition by acting the ] ], one of the Karanas, by raising his feet to his head. Other texts describe Shiva appearing as a crying infant and appealing to her maternal instincts. While Shiva is said to be able to tame her, the iconography often presents her dancing on his fallen body, and there are accounts of the two of them dancing together, and driving each other to such wildness that the world comes close to unravelling. | |||

| ==In popular culture== | |||

| Shiva's involvement with ] and Kali's dark nature have led to her becoming an important Tantric figure. To the ] worshippers, it was essential to face her Curse, the terror of death, as willingly as they accepted Blessings from her beautiful, nurturing, maternal aspect. For them, wisdom meant learning that no coin has only one side: as death cannot exist without life, so life cannot exist without death. Kali's role sometimes grew beyond that of a chaos — which could be confronted — to that of one who could bring wisdom, and she is given great metaphysical significance by some Tantric texts. The Nirvāna-tantra clearly presents her uncontrolled nature as the Ultimate Reality, claiming that the ] of Brahma, Visnu and Rudra arise and disappear from her like bubbles from the sea. Although this is an extreme case, the Yogini-tantra, Kamakhya-tantra and the Niruttara-tantra declare her the svarupa (own-being) of the Mahadevi (the great Goddess, who is in this case seen as the combination of all devis). | |||

| ]'' magazine cover, 1972]] | |||