| Revision as of 07:38, 2 September 2008 editJappalang (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers12,378 edits Not shared a shared possession between the two, plus further copyedit← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:06, 18 November 2024 edit undoPanteraMax (talk | contribs)8 editsm →Television: Fixed grammarTags: canned edit summary Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App select source | ||

| (585 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|19th century period of competitive fossil hunting}} | |||

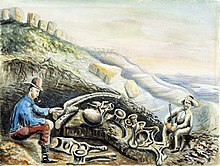

| ] (left) and ] (right) sparked the Bone Wars.]] | |||

| {{About|the period of competitive fossil hunting during the late 19th century|the series of armed conflicts between the Dutch and the state of Bone on Sulawesi|Dutch–Bone wars|the book by Tom Rea|Bone Wars (book){{!}}''Bone Wars'' (book)|the 2011 documentary film|Dinosaur Wars (film){{!}}''Dinosaur Wars'' (film)}} | |||

| The '''Bone Wars''' is the name given to a period of intense fossil speculation and discovery during the ] of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between ] and ]. The two ]s used underhanded methods to out-compete the other in the field, resorting to ], theft, and destruction of bones. The scientists also attacked each other in scientific publications, attempting to ruin the other's credibility and cut off his funding. | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2016}} | |||

| ] (left) and ] (right) sparked the Bone Wars.]] | |||

| The '''Bone Wars''', also known as the '''Great Dinosaur Rush''',<ref>Martin, 66.</ref> was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive ] and discovery during the ] of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between ] (of the ] of ]) and ] (of the ] at ]). Each of the two ]s used underhanded methods to try to outdo the other in the field, resorting to bribery, theft, and the destruction of bones. Each scientist also sought to ruin his rival's reputation and cut off his funding, using attacks in scientific publications. | |||

| Their search for ]s led them west to rich ]s in ], ], and ]. From 1877 to 1892, both paleontologists used their wealth and influence to finance their own expeditions and to procure services and dinosaur bones from fossil hunters. By the end of the Bone Wars, both men had exhausted their funds in the pursuit of paleontological supremacy. | |||

| Cope and Marsh were financially and socially ruined by their |

Cope and Marsh were financially and socially ruined by their attempts to outcompete and disgrace each other, but they made important contributions to science and the field of paleontology and provided substantial material for further work—both scientists left behind many unopened boxes of fossils after their deaths. The efforts of the two men led to 136 new species of ]s being discovered and described. The products of the Bone Wars resulted in an increase in knowledge of ] life, and sparked the public's interest in dinosaurs, leading to continued fossil excavation in ] in the decades to follow. Many historical books and fictional adaptations have been published about this period of intense fossil-hunting activity. | ||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| ===Background=== | ===Background=== | ||

| At |

At first, the relationship between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh was amicable. They met in Berlin in 1864 and spent several days together. They even named ] after each other.<ref name="dodson">Dodson.</ref> Over time their relations soured, due in part to their strong personalities. Cope was known to be pugnacious and possessed a quick temper; Marsh was slower, more methodical, and introverted. Both were quarrelsome and distrustful.<ref>Bryson, 92.</ref> Their differences also extended into the scientific realm, as Cope was a firm supporter of ] while Marsh supported ]'s ] by ].<ref name="ans"/> Even at the best of times, both men were inclined to look down on each other subtly. As one observer put it, "The patrician Edward may have considered Marsh not quite a gentleman. The academic Othniel probably regarded Cope as not quite a professional."<ref name="limerick-7"/> | ||

| Cope and Marsh came from very different backgrounds. Cope was born into a wealthy and influential ] family based in Philadelphia. Although his father wanted his son to work as a farmer, Cope |

Cope and Marsh came from very different backgrounds. Cope was born into a wealthy and influential ] family based in Philadelphia. Although his father wanted his son to work as a farmer, Cope distinguished himself as a ].<ref name="limerick-7">Limerick, ''et al.'', 7.</ref> In 1864, already a member of the ], Cope became a professor of ] at ] and joined ] on his expeditions west. In contrast, Marsh would have grown up poor, the son of a struggling family in ], had it not been for the benefaction of his uncle, philanthropist ].<ref name="preston-60">Preston, 60.</ref> Marsh persuaded his uncle to build the ], placing Marsh as head of the museum. Combined with the inheritance he received from Peabody upon his death in 1869, Marsh was financially comfortable (although, partly because of Peabody's stern views on marriage, Marsh would remain a lifelong bachelor).<ref>Bryson, 93.</ref> | ||

| ]'']] | |||

| On one occasion, the two scientists had gone on a fossil-collecting expedition to Cope's ] pits in New Jersey, where ] had discovered the ] specimen of ''] foulkii'', described by the paleontologist ] (under whom Cope had studied comparative anatomy); this was one of the first American dinosaur finds, and the pits were still rich with fossils.<ref name="dodson"/> Though the two parted amicably, Marsh secretly bribed the pit operators to divert future fossil finds to him, instead of Cope.<ref name="dodson"/> The two began attacking each other in papers and publications, and their personal relations deteriorated.<ref name="preston-61">Preston, 61.</ref> Marsh humiliated Cope by pointing out that his reconstruction of the plesiosaur '']'' was flawed, with the head placed where the tail should have been (or so he claimed, 20 years later;<ref>Marsh.</ref> it was Leidy who published the correction shortly afterwards).<ref>Leidy.</ref> Cope, in turn, began collecting in what Marsh considered his private bone-hunting turf in Kansas and Wyoming, further damaging their relationship.<ref name="preston-61"/><ref name="penick">Penick.</ref> | |||

| ===1872–1877: Early expeditions=== | |||

| On one occasion, the two scientists had gone on a fossil-collecting expedition to Cope's ] pits in New Jersey, where ] had discovered the ] specimen of ''] foulkii'', described by the paleontologist ]; this was one of the first American dinosaur finds, and the pits were still rich with fossils.<ref name="dodson">Dodson.</ref> Though the two parted amicably, Marsh secretly bribed the pit operators to divert the fossils they were discovering to him, instead of Cope.<ref name="dodson"/> The two began attacking each other in papers and publications, and their personal relations soured.<ref name="preston-61"/> Marsh humiliated Cope by pointing out his reconstruction of the plesiosaur '']'' was flawed, with the head placed where the tail should have been. Cope, in turn, began collecting in what Marsh considered his private bone-hunting turf in Kansas and in Wyoming.<ref name="preston-61">Preston, 61.</ref><ref name="penick">Penick.</ref> Any pretense of cordiality between the two ended in 1872, and open hostility ensued.<ref>Wilford, 87.</ref> | |||

| In the 1870s, Cope's and Marsh's professional attentions were directed to the American West by word of large fossil finds. Using his influence in Washington, D.C., Cope was granted a position on the ] under ]. While the position offered no salary, it afforded Cope a great opportunity to collect fossils in the West and publish his finds. Cope's flair for dramatic writing suited Hayden, who needed to make a popular impression with the official survey reports. In June 1872 Cope set off on his first trip, intending to observe the ] bone beds of Wyoming for himself. This caused a rift between Cope, Hayden, and Leidy. It was Leidy who had enjoyed receiving many of the fossils from Hayden's collection until Cope joined the survey, and now Cope was hunting for fossils in Leidy's staked territory—at the same time Leidy was to be collecting.<ref name="thomson-217">Thomson, 217.</ref> Hayden attempted to smooth things over with Leidy in a letter: | |||

| <blockquote>I asked him not to go into that field, that you were going there. He laughed at the idea of being restricted to any locality and said he intended to go whether I aided him or not. I was anxious to secure the cooperation of such a worker as an honor to my corps. I could not be responsible for the field he selected in as much as I pay him no salary and a portion of his expenses. You will see therefore that while it is not a pleasant thing to work in competition with others it seems almost a necessity. You can sympathize.<ref name="thomson-217"/></blockquote> | |||

| Cope took his family with him as far as Denver, while Hayden tried to keep Cope and Leidy from prospecting in the same area. Following a tip from geologist ], Cope also intended to investigate reports of bones Meek had found near Black Buttes Station and the railroad. Cope found the site and some skeletal remains of a dinosaur he dubbed '']''.<ref>Thomson, 218.</ref> Believing he had the full support of Hayden and the survey, Cope then traveled to ] in June, only to find that the men, wagons, horses, and equipment he expected were not there.<ref name="thomson-219"/> Cope cobbled together an outfit at his own expense, consisting of two teamsters, a cook, and a guide,<ref>Western History Association, 56.</ref> along with three men from Chicago who were interested in studying with him.<ref name="thomson-219">Thomson, 219.</ref> As it turned out, two of Cope's men were in fact in the employ of Marsh. When the rival paleontologist found out his own men were taking Cope's money, he was furious. While the men tried to assure Marsh they were still his men (one suggested he took the job in order to lead Cope away from good fossils), Marsh's laziness in soliciting firm agreements and payments may have caused them to seek other work.<ref>Thomson, 221–222.</ref> Cope's journey took the expedition through rugged country only Hayden had surveyed, and he discovered dozens of new species. Meanwhile, one of Marsh's men accidentally forwarded some of his material to Cope instead. On receiving the fossils, Cope sent them back to Marsh, but further damage had been done to their relationship.<ref>Thomson, 225–228.</ref> | |||

| ===Como Bluff and the west=== | |||

| ] | |||

| In the 1870s, Cope's and Marsh's professional attentions were directed to the American West by word of large fossil finds. In 1877, Marsh received a letter from ], a schoolteacher in ]. Lakes reported that he had been hiking in the mountains near the town of Morrison when he and H. C. Beckwith, his friend, had discovered massive bones embedded in the rock. Lakes wrote in his letter that the bones were "apparently a vertebra and a humerus bone of some gigantic saurian."<ref>Wilford, 105.</ref> While awaiting Marsh's reply, Lakes dug up more "colossal" bones and sent them to New Haven. As Marsh was slow to respond, Lakes also sent a shipment of bones to Cope. | |||

| Any pretense of cordiality between Cope and Marsh ended in 1872,<ref>Wilford, 87.</ref> and by spring 1873 open hostility ensued.<ref>Thomson, 229.</ref> At the same time, Leidy, Cope and Marsh were making great discoveries of ancient ]s and ]s in the Western bone beds. The paleontologists had a habit of making hasty ]s eastward describing their finds, only publishing fuller accounts after returning from trips. Among the new specimens described by the men were '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', and '']''. The problem was that many of these finds were not uniquely different from each other; in fact, Cope and Marsh knew that some of the fossils they were collecting had already been found by the others.<ref>Thomson, 235.</ref> As it turned out, many of Marsh's names were valid, while none of Cope's were. Marsh also placed the new species into a new ] of mammals, ]. Cope was humiliated and powerless to stop his rival's changes. Instead, he published a broad analytical study where he proposed a new plan of classification for the Eocene mammals, in which he discarded Marsh's ] in favor of his own. Marsh remained steadfast and continued to claim that all of Cope's names for Dinocerata were incorrect.<ref>Thomson, 237.</ref> | |||

| ] in New Haven, Connecticut, c. 1880]] | |||

| While the scientists argued over classifications and ], they also returned west for more fossils. Marsh made his last trip backed by Yale in 1873, with a large group of thirteen students accompanying him, protected by a group of soldiers who wanted to make a ] to the ] tribe. Due to concerns over his more lavish and expensive expeditions in years past, Marsh had the students pay their own way, and the trip cost Yale only $1857.50, far less than the $15,000 (over $200,000 in modern currency) that Marsh had claimed for the previous expedition. This excursion would prove to be Marsh's last: for the rest of the Bone Wars, Marsh preferred to enlist the services of local collectors. Though he had enough bones to study for years, the scientist's appetite for more would grow.<ref>Thomson, 245.</ref> Cope was even more prolific in his collecting that season than he was in 1872, although Marsh's penchant for cultivating collectors of his own meant that at Bridger his rival was ''persona non grata''. Tired of working under Hayden, Cope found a paying job with the ], but was limited by this federal association; while Cope had to tag along on surveys, Marsh could collect wherever he pleased.<ref>Thomson, 250.</ref> | |||

| The two scientists' attention turned to the ] in the mid-1870s, where the ] in the ] increased Native American ]. Marsh, desiring the fossils found in that region, became embroiled in Army-Indian politics.<ref>Thomson, 264.</ref> In order to gain the support of ] of the Sioux to prospect, Marsh promised Red Cloud payment for fossils collected and that he would return to Washington, D.C. and lobby on their behalf about their improper treatment. In the end, Marsh slipped out of camp and according to his own (possibly romanticized) accounts, amassed cartloads of fossils and retreated just before a hostile ] party arrived.<ref>Thomson, 267.</ref> Marsh, for his part, did lobby the ] and President ] on behalf of Red Cloud, but his motives might have been to make a name for himself against the unpopular Grant administration.<ref>Thomson, 269.</ref> By 1875, both Cope and Marsh paused in their collecting, feeling financial strain and needing to catalogue their backlogged finds, but new discoveries would return them to the West before decade's end.<ref>Thomson, 271.</ref> | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| When Marsh responded to Lakes, he paid the prospector $100, urging him to keep the finds a secret. Learning that Lakes had corresponded with Cope, Marsh sent his field collector ] to Morrison to secure Lake's services. At the same time Marsh published a description of Lake's discoveries in the '']'' on July 1, and before Cope could publish his own interpretation of the finds, Lakes wrote to him that the bones should be shipped to Marsh, a severe insult to Cope.<ref name="wilford-106">Wilford, 106.</ref> | |||

| ===1877–1892: Como Bluff finds=== | |||

| A second letter arrived from the West, this time addressed to Cope. ] was a naturalist who had been collecting plants near Cañon City, Colorado, when he came upon an assortment of fossil bones. After receiving more samples from Lucas, Cope concluded the dinosaurs were large herbivores, gleefully noting the specimen was larger than any other described at the time, including Lakes' discovery.<ref name="wilford-106"/><ref name="wallace-147">Wallace, 147.</ref> Marsh heard of Lucas' finds and instructed Mudge and his former student Samuel Wendell Williston to set up a quarry on his behalf near Cañon. Unfortunately for Marsh, he learned from Williston that Lucas was finding the best bones and had refused to quit Cope to work for him.<ref name="wilford-107">Wilford, 107.</ref> Marsh ordered Williston back to Morrison, where Marsh's small quarry collapsed and nearly killed his assistants. This setback would have dried up Marsh's bone supply from the west if not for a third letter addressed to him.<ref name="wallace-148">Wallace, 148.</ref> | |||

| In 1877, Marsh received a letter from ], a schoolteacher in ]. Lakes reported that he had been hiking in the mountains near the town of ], when he and his friend, H. C. Beckwith, discovered massive bones embedded in the rock. Lakes further advised that the bones were "apparently a ] and a ] bone of some gigantic saurian."<ref>Wilford, 105.</ref> While awaiting Marsh's reply, Lakes dug up more "colossal" bones and sent them to New Haven. As Marsh was slow to respond, Lakes also sent a shipment of bones to Cope.<ref name="wilford-106"/> | |||

| ] at ], ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| When Marsh responded to Lakes, he paid the prospector $100, urging him to keep the finds a secret. Learning that Lakes had corresponded with Cope, Marsh sent his field collector ] to Morrison to secure Lakes' services. Marsh published a description of Lakes' discoveries in the '']'' on July 1, and before Cope could publish his own interpretation of the finds, Lakes wrote to him that the bones should be shipped to Marsh, a severe insult to Cope.<ref name="wilford-106">Wilford, 106.</ref> | |||

| At the time of Lake's discoveries, the ] was being built through a remote area of Wyoming. Marsh's letter was from two men identifying themselves as Harlow and Edwards (their real names were Carlin and Reed), workers on the ]. The two men claimed they had found large amounts of fossils in ], and warned that there were others in the area "looking for such things",<ref>Wilford, 108.</ref> which Marsh took to mean Cope. Marsh sent Williston, who had just wearily arrived in Kansas after the collapse of the Morrison mine,<ref name="jaffe-228">Jaffe, 228.</ref> to Como. His former student sent back a message, confirming the veracity of both the large quantities of bones and the reports that Cope's men were snooping around in the area.<ref name="preston-62">Preston, 62.</ref> Wary of repeating the same mistakes he had made with Lakes, Marsh quickly sent money to the two new bone hunters and urged them to send additional fossils.<ref name="jaffe-228"/> Williston struck a preliminary bargain with Carlin and Reed (who had been unable to cash Marsh's check due to it being made out to their pseudonyms), but Carlin decided he would head to New Haven to deal with Marsh directly.<ref>Jaffe, 229.</ref> Marsh drew up a contract calling for a set monthly fee, with additional cash bonuses to Carlin and Reed possible, depending on the importance of the finds. Marsh also reserved the right to send his own "superintendents" to supervise the digging if needed, and advised the men to try and keep Cope out of the region.<ref name="jaffe-230">Jaffe, 230.</ref> Despite a face-to-face meeting, Carlin failed to negotiate better terms from Marsh. The paleontologist procured Carlin's and Reed's work for the stated terms, but seeds of discord and resentment were sown in the bone hunters as they felt Marsh had bullied them into the deal.<ref name="jaffe-230"/> Marsh's investment in the Como Bluff region soon produced rich results. While Marsh's own collectors headed east for the winter, Reed sent carloads of bones by rail to Marsh throughout 1877. Marsh described and named dinosaurs such as '']'', '']'', and '']'' in the December 1877 issue of the ''American Journal of Science.''<ref name="wallace-149">Wallace, 149-150.</ref> | |||

| A second letter arrived from the west, this time addressed to Cope. The writer, O. W. Lucas, was a naturalist who had been collecting plants near ] when he came upon an assortment of fossil bones. After receiving more samples from Lucas, Cope concluded the dinosaurs were large ]s, gleefully noting that the specimen was larger than any other previously described, including Lakes' discovery.<ref name="wilford-106"/><ref name="wallace-147">Wallace, 147.</ref> Hearing of Lucas' finds, Marsh instructed Mudge and a former student, ], to set up a quarry on his behalf near Cañon. Unfortunately for Marsh, he learned from Williston that Lucas was finding the best bones and refused to quit Cope to come work for Marsh.<ref name="wilford-107">Wilford, 107.</ref> Marsh ordered Williston back to Morrison, where Marsh's small quarry collapsed and nearly killed his assistants. This setback would have dried up Marsh's bone supply from the west, if not for receipt of a third letter.<ref name="wallace-148">Wallace, 148.</ref> | |||

| Despite Marsh's precautions against alerting his rival to Como Bluff's rich bone beds, word of the discoveries quickly spread. Carlin and Reed were involved in the spreading of these rumors, leaking information to the ''Laramie Daily Sentinel'' which published an article about the finds in April 1878. The piece exaggerated the price Marsh had paid for the bones heading east, possibly to raise prices and demand for more bones.<ref name="wallace-152">Wallace, 152.</ref> Marsh, attempting to cover the leak, learned from Williston that Carlin and Reed had been frequented by a man ostensibly working for Cope by the name of "Haines".<ref name="wallace-152"/> Cope had learned of the Como Bluff discoveries, and sent "dinosaur rustlers" to the area in an attempt to quietly steal fossils from under Marsh's nose.<ref name="bakker"/> During the winter of 1878 dissatisfaction with Marsh's infrequent payments fomented, and Carlin began working for Cope instead. | |||

| ]'s sketch of expedition members W.H. Reed (left) and Edward Kennedy in Como Bluff]] | |||

| At the time of Lakes' discoveries, the ] was being built through a remote area of Wyoming. Marsh's letter was from two men identifying themselves as Harlow and Edwards, workers on the ]. Their real names were ] (1848–1915) and William Edwards Carlin.<ref name="reed-archives-peabody">{{cite web |title=William Harlow Reed - Archives : Collections : Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History |url=http://peabody.yale.edu/collections/archives/biography/william-harlow-reed |website=peabody.yale.edu |access-date=10 September 2018 |date=2 December 2010}}</ref> The two men claimed they had found large numbers of fossils in ], and warned that there were others in the area "looking for such things",<ref>Wilford, 108.</ref> which Marsh took to mean Cope. Williston, who had just wearily arrived in Kansas after the collapse of the Morrison mine,<ref name="jaffe-228">Jaffe, 228.</ref> was quickly dispatched to Como Bluff by Marsh. His former student sent back a message, confirming the large quantities of bones and that it was Cope's men snooping around the area.<ref name="preston-62">Preston, 62.</ref> Wary of repeating the same mistakes he had made with Lakes, Marsh quickly sent money to the two new bone hunters and urged them to send additional fossils.<ref name="jaffe-228"/> Williston struck a preliminary bargain with Carlin and Reed (who had been unable to cash Marsh's ] due to it being made out to their pseudonyms), but Carlin decided he would head to New Haven to deal with Marsh directly.<ref>Jaffe, 229.</ref> Marsh drew up a contract calling for a set monthly fee, with additional cash bonuses to Carlin and Reed possible, depending on the importance of the finds. Marsh also reserved the right to send his own "superintendents" to supervise the digging if needed and advised the men to try to keep Cope out of the region.<ref name="jaffe-230">Jaffe, 230.</ref> Despite a face-to-face meeting, Carlin failed to negotiate better terms from Marsh. The paleontologist procured Carlin's and Reed's services, but seeds of resentment were sown as the bone hunters felt Marsh had bullied them into the deal.<ref name="jaffe-230"/> Marsh's investment in the Como Bluff region soon produced rich results. While Marsh's own collectors headed east for the winter, Reed sent carloads of bones by rail to Marsh throughout 1877. Marsh described and named dinosaurs such as '']'', '']'', and '']'' in the December 1877 issue of the ''American Journal of Science.''<ref name="wallace-149">Wallace, 149–150.</ref> | |||

| Despite Marsh's precautions against alerting his rival to Como Bluff's rich bone beds, word of the discoveries rapidly spread. This was at least partly due to Carlin and Reed helping spread the rumors. They leaked information to the ''Laramie Daily Sentinel'', which published an article about the finds in April 1878 that exaggerated the price Marsh had paid for the bones, possibly to raise prices and demand for more bones.<ref name="wallace-152">Wallace, 152.</ref> Marsh, attempting to cover the leak, learned from Williston that Carlin and Reed had been visited by a man ostensibly working for Cope by the name of "Haines".<ref name="wallace-152"/> After learning of the Como Bluff discoveries, Cope sent "dinosaur rustlers" to the area in an attempt to quietly steal fossils from under Marsh's nose.<ref name="bakker">Bakker.</ref> During the winter of 1878, Carlin's dissatisfaction with Marsh's sporadic sending of payment reached a head, and he began working for Cope instead. | |||

| ] | |||

| Cope and Marsh used their personal wealth to fund expeditions each summer, then spent the winter publishing their discoveries. Small armies of fossil hunters in mule-drawn wagons or on trains were soon sending literal tons of fossils back east.<ref name="bates">Bates.</ref> Marsh's teams were the more extravagant; he had crews of at least five workers assist him on the occasions he went West himself. Cope, on the other hand, made do with two teamsters, a cook, and a guide.<ref>Western History Association, 56.</ref> The paleontological digs lasted fifteen years, from 1877 to 1892.<ref name="bakker">Bakker.</ref> The workers for both Cope and Marsh suffered hardships related to the weather, as well as sabotage and obstruction by the other scientist's workers. Reed was locked out of the Como train station by Carlin and was forced to haul the bones down the bluff and crate the specimens on the train platform in the bitter cold.<ref>Jaffe, 237.</ref> Cope directed Carlin to set up his own quarry in Como Bluff, while Marsh sent Reed to spy on his former friend. As Reed's Quarry #4 dried up, Marsh ordered Reed to clear out the bone fragments from the other quarries. Reed reported he had destroyed all the remaining bones to keep them away from Cope.<ref>Jaffe, 238.</ref> Concerned that strangers were encroaching on Reed's quarries, Marsh sent Lakes to Como to assist in excavations,<ref name="wallace-153">Wallace, 153-154.</ref> and in June 1879 visited Como himself. Cope likewise toured his own quarries in August. Although Marsh's men continued to open new quarries and discover more fossils, relations between Lakes and Reed soured, with each offering his resignation in August. Marsh attempted to placate the two by sending each to opposite ends of the quarries,<ref>Jaffe, 244.</ref> but after being forced to abandon one bone quarry in a freezing blizzard, Lakes submitted his resignation and returned to teaching in 1880.<ref name="wallace-156">Wallace, 156.</ref> The departure of Lakes did not ease tensions among Marsh's men; Lake's replacement, a railroad man named Kennedy, felt he didn't have to report to Reed, and the fighting between the two caused Marsh's other workers to quit. Marsh tried separating Kennedy and Reed, and sent Williston's brother Frank to Como in an effort to keep the peace. Frank Williston ended up leaving Marsh's employ and taking up residence with Carlin.<ref name="jaffe-246">Jaffe, 246.</ref> Cope's own digging in Como began faltering, and Carlin's replacements soon quit work altogether.<ref name="jaffe-246"/> | |||

| Cope and Marsh used their personal wealth to fund expeditions each summer, then spent the winter publishing their discoveries. Small armies of fossil hunters in mule-drawn wagons or on trains were soon sending literally tons of fossils back east.<ref name="bates">Bates.</ref> The paleontological digs lasted fifteen years, from 1877 to 1892.<ref name="bakker"/> The workers for both Cope and Marsh suffered hardships related to the weather, as well as sabotage and obstruction by the other scientist's workers. Reed was locked out of the Como train station by Carlin, and was forced to haul the bones down the bluff and crate the specimens on the train platform in the bitter cold.<ref>Jaffe, 237.</ref> Cope directed Carlin to set up his own quarry in Como Bluff, while Marsh sent Reed to spy on his former friend. As Reed's Quarry #4 dried up, Marsh ordered Reed to clear out the bone fragments from the other quarries. Reed reported he had destroyed all the remaining bones to keep them away from Cope.<ref>Jaffe, 238.</ref> Concerned that strangers were encroaching on Reed's quarries, Marsh sent Lakes to Como to assist in excavations,<ref name="wallace-153">Wallace, 153–154.</ref> and in June 1879 visited Como himself. Cope likewise toured his own quarries in August. Although Marsh's men continued to open new quarries and discover more fossils, relations between Lakes and Reed soured, with each offering his resignation in August. Marsh attempted to placate the two by sending each to opposite ends of the quarries,<ref>Jaffe, 244.</ref> but after being forced to abandon one bone quarry in a freezing blizzard, Lakes submitted his resignation and returned to teaching in 1880.<ref name="wallace-156">Wallace, 156.</ref> The departure of Lakes did not ease tensions among Marsh's men; Lakes's replacement, a railroad man named Kennedy, felt he did not have to report to Reed, and the fighting between the two caused Marsh's other workers to quit. Marsh tried separating Kennedy and Reed, and sent Williston's brother Frank to Como in an effort to keep the peace. Frank Williston ended up leaving Marsh's employ and taking up residence with Carlin.<ref name="jaffe-246">Jaffe, 246.</ref> Cope's own digging in Como began faltering, and Carlin's replacements soon quit work altogether.<ref name="jaffe-246"/> | |||

| As the 1880's progressed, Cope's and Marsh's men faced stiff competition from each other and third parties interested in bones. Professor ] of Harvard sent his own representatives west, while Carlin and Frank Williston formed a bone company to sell fossils to the highest bidder.<ref name="wallace-157">Wallace, 157.</ref> Reed left and began a career in ] in 1884, and Marsh's Como quarries yielded little after his departure.<ref name="wallace-157"/> Despite these setbacks, Marsh had more operational quarries than Cope at this point of time; Cope, who at the early 1880s had more bones than he could fit in a single house, had fallen behind in the race for dinosaurs. | |||

| ]'', a dinosaur he described and named in 1877]]As the 1880s progressed, Cope's and Marsh's men faced stiff competition from each other and from third parties interested in bones. Professor ] of ] sent his own representatives west, while Carlin and Frank Williston formed a bone company to sell fossils to the highest bidder.<ref name="wallace-157">Wallace, 157.</ref> Reed left and became a sheep herder in 1884, and Marsh's Como quarries yielded little after his departure. Despite these setbacks, Marsh had more operational quarries than Cope at this point of time; Cope, who at the early 1880s had more bones than he could fit in a single house, had fallen behind in the race for dinosaurs.<ref name="wallace-157"/> | |||

| Cope's and Marsh's discoveries were accompanied by sensational accusations of spying, stealing workers and fossils, and bribery. The two men were so protective of their digging sites that they would destroy smaller or damaged fossils to prevent them from falling into their rival's hands, or fill in their excavations with dirt and rock;<ref name="preston-63"/> while surveying his Como quarries in 1879, Marsh examined recent finds and marked several for destruction.<ref name="wallace-153"/> On one occasion the scientist's rival teams fought each other by throwing stones.<ref name="wallace-157"/> | |||

| Cope's and Marsh's discoveries were accompanied by sensational accusations of spying, stealing workers and fossils, and bribery. The two men were so protective of their digging sites that they would destroy smaller or damaged fossils to prevent them from falling into their rival's hands, or fill in their excavations with dirt and rock;<ref name="preston-63">Preston, 63.</ref> while surveying his Como quarries in 1879, Marsh examined recent finds and marked several for destruction.<ref name="wallace-153"/> On one occasion the scientists' rival teams fought each other by throwing stones.<ref name="wallace-157"/> | |||

| ===Personal disputes and later years=== | ===Personal disputes and later years=== | ||

| While Cope and Marsh dueled for fossils in the American West, they also tried their best to ruin each |

While Cope and Marsh dueled for fossils in the American West, they also tried their best to ruin each other's professional credibility. Humiliated by his error in reconstructing the ] '']'', Cope tried to cover up his mistake by purchasing every copy he could find of the journal in which it was published.<ref>Jaffe, 15.</ref> Marsh, meanwhile, made sure to publicize the story. Cope's own rapid and prodigious output of scientific papers meant that Marsh had no difficulty in finding occasional errors with which to lambast Cope.<ref name="penick"/> Marsh himself was not infallible; he put the skull of a '']'' on a skeleton of '']''.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=D'Emic|first1=Michael D.|last2=Carrano|first2=Matthew T.|date=2020|title=Redescription of Brachiosaurid Sauropod Dinosaur Material From the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Colorado, USA|journal=The Anatomical Record|language=en|volume=303|issue=4|pages=732–758|doi=10.1002/ar.24198|pmid=31254331 |s2cid=195765189 |issn=1932-8494|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>Rajewski, 22.</ref> | ||

| By the late |

By the late 1880s, public attention to the fighting between Cope and Marsh faded, drawn to international stories rather than the "Wild West".<ref name="wallace-175">Wallace, 175–177.</ref> Thanks to ], head of the U.S. Geological Survey, and Marsh's contacts with the rich and powerful in Washington, Marsh was placed at the head of the consolidated government survey and was happy to be out of the sensationalist spotlight.<ref name="wallace-175"/> Cope was much less well-off, having spent most of his money purchasing '']'', and had a hard time finding employment thanks to Marsh's allies in higher education and his own temperament.<ref name="wallace-175"/><ref>Jaffe, 324.</ref> Cope began investing in gold and silver prospects in the West, and braved ]l mosquitos and harsh weather to search for fossils himself.<ref name="wallace-183">Wallace, 183.</ref> Due to mining setbacks and a lack of support from the federal government,<ref name="penick"/> Cope's financial situation deteriorated to the point that his fossil collection was his only significant asset. Marsh, meanwhile, alienated even his loyal assistants, including Williston, with his refusal to share his conclusions drawn from their findings, and his continually lax and infrequent payment schedule.<ref name="wallace-195">Wallace, 195.</ref> | ||

| Cope's chance to exploit Marsh's vulnerabilities came in 1884, when Congress began to investigate the proceedings of the consolidated geological survey. Cope had become friends with ], then a professor of anatomy at ].<ref>Sterling, 592.</ref> Osborn was like Marsh in many ways, slow and methodical, but would prove a damaging influence on Marsh.<ref name="wallace-201">Wallace, 201.</ref> Cope searched for disgruntled workers who would speak out against Powell and the Survey. For the moment, Powell and Marsh were able to successfully refute Cope's charges, and his allegations did not reach the mainstream press.<ref>Wallace, 203.</ref> Osborn seemed reluctant to step up his campaign against Marsh, so Cope turned to another ally he had mentioned to Osborn—a "newspaper man from New York" named ].<ref>Wallace, 204.</ref><ref name="osborn-403"/> Despite setbacks in trying to oust Marsh from his presidency of the ],<ref>Farlow, 709.</ref> Cope received a tremendous financial boost after the ] offered him a teaching job.<ref name="penick"/> |

Cope's chance to exploit Marsh's vulnerabilities came in 1884, when ] began to investigate the proceedings of the consolidated geological survey. Cope had become friends with ], then a professor of anatomy at ].<ref>Sterling, 592.</ref> Osborn was like Marsh in many ways, slow and methodical, but would prove a damaging influence on Marsh.<ref name="wallace-201">Wallace, 201.</ref> Cope searched for disgruntled workers who would speak out against Powell and the Survey. For the moment, Powell and Marsh were able to successfully refute Cope's charges, and his allegations did not reach the mainstream press.<ref>Wallace, 203.</ref> Osborn seemed reluctant to step up his campaign against Marsh, so Cope turned to another ally he had mentioned to Osborn—a "newspaper man from New York" named ].<ref>Wallace, 204.</ref><ref name="osborn-403"/> Despite setbacks in trying to oust Marsh from his presidency of the ],<ref>Farlow, 709.</ref> Cope received a tremendous financial boost after the ] offered him a teaching job.<ref name="penick"/> | ||

| Over the years, Cope kept an elaborate journal of mistakes and misdeeds that Marsh and Powell had committed; the mistakes and errors of the men were put in writing and |

Cope's chance to strike a critical blow at Marsh appeared soon after. Over the years, Cope kept an elaborate journal of mistakes and misdeeds that Marsh and Powell had committed; the mistakes and errors of the men were put in writing and stored in the bottom drawer of Cope's desk.<ref>Osborn, 585.</ref> Ballou planned the first set of articles, in what would become a series of newspaper debates between Marsh, Powell and Cope.<ref name="osborn-403">Osborn, 403.</ref> While the scientific community had long known of Marsh and Cope's rivalry, the public became aware of the shameful conduct of the two men when the '']'' published a story with the headline "Scientists Wage Bitter Warfare."<ref name="preston-63"/> According to author Elizabeth Noble Shor, the scientific community was galvanized: | ||

| <blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| Most scientists of the day recoiled |

Most scientists of the day recoiled to find that Cope's feud with Marsh had become front-page news. Those closest to the scientific fields under discussion, geology and vertebrate paleontology, certainly winced, particularly as they found themselves quoted, mentioned, or misspelled. The feud was not news to them, for it had lurked at their scientific meetings for two decades. Most of them had already taken sides.<ref>Shor.</ref></blockquote> | ||

| In the newspaper articles, Cope attacked Marsh for plagiarism and financial mismanagement and attacked Powell for his geological classification errors and misspending of government |

In the newspaper articles, Cope attacked Marsh for ] and financial mismanagement, and attacked Powell for his geological classification errors and misspending of government-allocated funds.<ref>Osborn, 404.</ref> Marsh and Powell were each able to publish their own side of the story, filing their own charges against Cope. Ballou's articles were poorly researched, written, and read, and Cope himself was smarting from a piece in '']'' which suggested the University of Pennsylvania trustees would ask Cope to step down unless he provided proof for his charges against Marsh and Powell.<ref name="wallace-238">Wallace, 238–239.</ref> Marsh himself kept the ''Herald'' story alive with a fiery rebuttal, but by the end of January the story had faded from all the newspapers, and little changed between the bitter rivals.<ref>Wallace, 252.</ref> | ||

| No congressional hearing was |

No congressional hearing was convened to investigate the misallocation of funds by Powell, and neither Cope nor Marsh was held responsible for any of their mistakes, but some of Ballou's charges against Marsh came to be associated with the Survey. Facing anti-Survey sentiment inflamed by western drought and concerns about takeovers of abandoned western homesteads, Powell found himself the subject of larger scrutiny before the ].<ref name="wallace-256">Wallace, 256–257.</ref> Galvanized to action by Marsh's perceived extravagance with Survey funds, the Appropriations Committee demanded the Survey's budget be itemized.<ref name="wallace-256"/> When his appropriation was cut off in 1892, Powell sent a terse telegram to Marsh demanding his resignation, a personal slight as well as a financial one.<ref>Jaffe, 329.</ref> At the same time, many of Marsh's allies were retiring or had died, lessening his scientific credence.<ref>Wallace, 260.</ref> Just as Marsh's extravagant lifestyle was catching up with him, Cope received a position on the ]. Cope, still reeling from the personal attacks levied at him during the ''Herald'' affair, did not take advantage of the change in fortunes to press his personal attacks.<ref>Wallace, 261.</ref> Cope's fortunes continued to look up throughout the early 1890s, as he was promoted to Leidy's position as Professor of Zoology and was elected President of the ] the same year that Marsh stepped down as head of the Academy of Sciences. Towards the latter part of the decade, Cope's fortunes began to sour once more as Marsh regained some of his recognition, earning the Cuvier Medal, the highest paleontological award.<ref>Wallace, 267.</ref> | ||

| Cope and Marsh's rivalry lasted until Cope's death in 1897, by which time both men |

Cope and Marsh's rivalry lasted until Cope's death in 1897, by which time both men were financially ruined. Cope suffered from a debilitating illness in his later years and had to sell part of his fossil collection and rent out one of his houses to make ends meet. Marsh in turn had to mortgage his residence and ask Yale for a salary on which to live.<ref name="penick"/> The rivalry between the two remained strong if weary. Cope issued a final challenge before his death.<ref name="dodson"/> He had his skull donated to science so that his brain could be measured, hoping that his brain would be larger than that of his adversary; at the time, brain size was believed to be a ]. Marsh never accepted the challenge, and Cope's skull is reportedly still preserved at the University of Pennsylvania.<ref name="dodson"/> (Whether the skull stored at the university is Cope's is disputed; the university stated that it believes the real skull was lost in the 1970s, although ] has said that hairline fractures on the skull and coroner's reports verify the skull's authenticity.)<ref>Baalke.</ref> | ||

| ==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

| ]'' (] #5753) discovered by Cope's fossil hunters at Como Bluff in 1879. The find was not unpacked until after Cope's death.<ref>Norell, 112.</ref>]] | ]'' (] #5753) discovered by Cope's fossil hunters at Como Bluff in 1879. The find was not unpacked until after Cope's death.<ref>Norell, 112.</ref>]] | ||

| Judging by pure numbers, Marsh "won" the Bone Wars. Both scientists made finds of |

Judging by pure numbers, Marsh "won" the Bone Wars. Both scientists made finds of immense scientific value, but while Cope discovered a total of 56 new dinosaur species, Marsh discovered 80.<ref name="bates"/><ref name="colbert-93">Colbert, 93.</ref> In the later stages of the Bone Wars, Marsh simply had more men and money at his disposal than Cope. Cope also had a much broader set of paleontological interests, while Marsh almost exclusively pursued fossilized reptiles and mammals.<ref>Colbert, 88.</ref> | ||

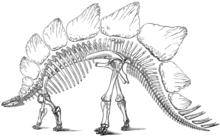

| Several of Cope's and Marsh's discoveries are the most well-known of dinosaurs, encompassing species of '']'', ''Allosaurus'', ''Diplodocus'', ''Stegosaurus'', '']'' and '']''. Their cumulative discoveries defined the then-nascent field of paleontology; before Cope's and Marsh's discoveries, there were only nine named species of dinosaur in North America.<ref name="colbert-93"/> |

Several of Cope's and Marsh's discoveries are among the most well-known of dinosaurs, encompassing species of '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'' and '']''. Their cumulative discoveries defined the then-nascent field of paleontology; before Cope's and Marsh's discoveries, there were only nine named species of dinosaur in North America.<ref name="colbert-93"/> Some of their ideas—such as Marsh's argument that birds are ]—have been upheld; while others are viewed as having little to no scientific merit.<ref>Trefil, 95.</ref> The Bone Wars also led to the discovery of the first complete skeletons, and the rise in popularity of dinosaurs with the public. As paleontologist ] stated, "The dinosaurs that came from not only filled museums, they filled magazine articles, textbooks, they filled people's minds."<ref name="bakker"/> | ||

| Despite their advances, the Bone Wars also had a negative effect not only on the two scientists but also on their peers and the entire field.<ref name="limerick-8">Limerick, 8.</ref> The public animosity between Cope and Marsh harmed the reputation of American paleontology in Europe for decades. Furthermore, the reported use of dynamite and ] by employees of both men may have harmed fossil remains,<ref name="ans"/> though later excavation suggests that some of the damage was exaggerated in order to dissuade competition.<ref>Rajewski, 21.</ref> ] abandoned his more methodical excavations in the West, finding he could not keep up with Cope's and Marsh's reckless searching for bones.<ref name="ans">Academy of Natural Sciences.</ref> Leidy also grew tired of the constant squabbling between the two men, with the result that his withdrawal from the field marginalized his own legacy; after his death, Osborn found not a single mention of the man in either of the rivals' works.<ref>Wallace, 84.</ref> In their haste to outdo each other, Cope and Marsh haphazardly assembled the bones of their own discoveries. Their descriptions of new species, based on their reconstructions, led to confusion and misconceptions that lasted for decades after their deaths.<ref>Jaffe, 248.</ref> | |||

| A 2007–2008 excavation of several of Cope's and Marsh's sites suggest that some of the damage propagated by the two paleontologists was less than what has been recorded. Using Lakes' field paintings, researchers from the Morrison Natural History Museum discovered that Lakes had not actually dynamited the most productive quarries in Colorado; rather, Lakes had just filled in the site. Museum director Matthew Mossbrucker theorized that Lakes propagated the lie "because he didn't want the competition up at the quarry—playing mind games with Cope's gang.<ref>Rajewski, 21.</ref> | |||

| ===Adaptations=== | ===Adaptations=== | ||

| ====Literature==== | |||

| Besides being the focus of historical and paleontological books, the Bone Wars has been the subject of a ], '']'', by ]. ''Bone Sharps'' is a work of historical fiction, as Ottaviani introduces the character of ] to Cope for plot purposes, and other events have been restructured.<ref>Mondor.</ref> The Bone Wars was featured in more fantastical form, in the book '']'' by ], which includes aliens also interested in the bones.<ref>Waggoner.</ref> | |||

| *Besides being the focus of historical and paleontological books, the Bone Wars is the subject of ]'s ] '']: A Tale of Edward Drinker Cope, Othniel Charles Marsh, and the Gilded Age of Paleontology'' (2005); ''Bone Sharps'' is a work of historical fiction, as Ottaviani introduces the character of ] to Cope for plot purposes, and other events have been restructured.<ref>Mondor.</ref> | |||

| *] young adult novel, ''Every Hidden Thing'' (2016), features the fictional children of two scientists based on Cope and Marsh as they live their own ] style adventure in the midst of the Bone Wars. | |||

| *]'s novel '']'' (published posthumously in 2017) addresses the Bone Wars through the experiences of a fictional character, William Johnson, who becomes an apprentice to both Marsh and Cope, and makes his own historic discovery.<ref>{{cite news|title=New Michael Crichton novel coming out in 2017|url=http://www.seattletimes.com/nation-world/apnewsbreak-new-michael-crichton-novel-coming-out-in-2017/|agency=Associated Press|work=Seattle Times|access-date=July 29, 2016}}</ref> | |||

| ====Television==== | |||

| *The Bone Wars is one of three stories retold in the "New Jersey" episode of the ] series '']''. Cope is portrayed by ] and Marsh by ], with ] as the drunk storyteller. | |||

| * The Bone Wars was a tangential part of '']''; season two, episode three titled, "Dinosaur Fever" wherein the Bone Wars conflict between Cope and Marsh set the foundation for the theme of the cutthroat world of 19th century paleontology in setting the foundation for the story. | |||

| * PBS produced '']'', a 2011 documentary about Cope and Marsh.<ref>{{cite web|last=Black|first=Riley|url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/scientists-clash-in-dinosaur-wars|url-access=registration|title=Scientists Clash in 'Dinosaur Wars'|work=]|date=January 17, 2011|accessdate=September 9, 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=15em}} | |||

| {{reflist|4}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{ |

{{Refbegin|30em}} | ||

| *{{cite mailing list |

*{{cite mailing list |last=Baalke |first=Ron |title=Edward Cope's Skull |mailing-list=] |date=October 13, 1994 |url=http://dml.cmnh.org/1994Oct/msg00196.html |access-date=August 15, 2008 |archive-date=March 6, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160306140504/http://dml.cmnh.org/1994Oct/msg00196.html |url-status=dead }} | ||

| *{{cite video | |

*{{cite video |people=Bates, Robin (series producer), Chesmar, Terri and Baniewicz, Rich (associate producers); ] (narrator) |title=The Dinosaurs! Episode 1: "The Monsters Emerge" |url=http://imdb.com/title/tt0103400/ |medium=TV-series |publisher=PBS Video, ] |date=1992 }} | ||

| *{{cite book|author=Bryson, Bill| |

*{{cite book |author=Bryson, Bill |author-link=Bill Bryson |year=2003 |title=] |chapter=Science Red in Tooth and Claw |publisher=] |location=United States |isbn=978-0-7679-0818-4}} | ||

| *{{cite book|author=Buffalo Bill Historical Center|year=1982|title=The American West|publisher=American West Publishing Company: ], ] |

*{{cite book |author=Buffalo Bill Historical Center |year=1982 |title=The American West |publisher=American West Publishing Company: ], ] }} | ||

| *{{cite book|author=Colbert, Edwin|year=1984|title=The Great Dinosaur Hunters and Their Discoveries|publisher=Courier Dover Publications|isbn=0-486-24701- |

*{{cite book |author=Colbert, Edwin |year=1984 |title=The Great Dinosaur Hunters and Their Discoveries |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-486-24701-4}} | ||

| *{{cite video | |

*{{cite video |people=], ] (interviewees) |title=The Dinosaurs! Episode 1: "The Monsters Emerge" |medium=TV-series |publisher=PBS Video, WHYY-TV |date=1992}} | ||

| *{{cite book |last1=Dingus |first1=Lowell |title=King of the Dinosaur Hunters : the life of John Bell Hatcher and the discoveries that shaped paleontology. |date=2018 |publisher=Pegasus Books |isbn=9781681778655}} | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Farlow, James|coauthors=Brett-Surman, M.K., and Walters, Robert|year=1999|title=The Complete Dinosaur|publisher=Indiana University Press|location=United States of America|isbn=0-253-21313-4}} | |||

| *{{cite book | |

*{{cite book |author=Farlow, James |author2=Brett-Surman, M. K. |author3=Walters, Robert |year=1999 |title=The Complete Dinosaur |publisher=] |location=United States |isbn=978-0-253-21313-6}} | ||

| *{{cite book |last=Jaffe |first=Mark |title=The Gilded Dinosaur: The Fossil War Between E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh and the Rise of American Science |publisher=] |location=New York |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-517-70760-9 |url=https://archive.org/details/gildeddinosaur00mark }} | |||

| *{{cite web|author=Levins, Hoag|year=2004|url=http://www.levins.com/bwars.shtml|title=Haddonfield and The 'Bone Wars'|publisher=Levins.com|accessdate=2008-04-15}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Bruce E. Johansen |author-link=Bruce E. Johansen |author2=Matthew Rothschild |title=Silenced!: Academic Freedom, Scientific Inquiry, and the First Amendment Under Siege in America |publisher=] |year=2007 |page=45 |isbn=978-0-275-99686-4 |oclc=85862143 }} | |||

| *{{cite journal|author=Limerick, Patrick|coauthors=Puska, Claudia|year=2003|url=http://www.centerwest.org/publications/pdf/science.pdf|title=Making the Most of Science in the American West|publisher=Center of the American West|location=]|}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |last=Leidy |first=J. |author-link=Joseph Leidy |title=Remarks on ''Elasmosaurus platyurus'' |journal=] |volume=22 |pages=9–10 |location=Philadelphia |date=March 8, 1870 |url=http://www.oceansofkansas.com/Leidy1870.html |access-date=February 2, 2009 }} (] maintained by M. J. Everhart) | |||

| *{{cite web|author=Mondor, Colleen|date=2006-01-01|url=http://www.bookslut.com/features/2006_01_007441.php|title=Comic Books and Thunder Lizards|publisher=BookSlut|accessdate=2008-01-20}} | |||

| *{{cite web |author=Levins, Hoag |year=2004 |url=http://www.levins.com/bwars.shtml |title=Haddonfield and The 'Bone Wars' |publisher=Levins.com |access-date=April 15, 2008 }} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Norell |first=Mark A. |coauthors=Gaffney, Eric S.; and Dingus, Lowell |title=Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History |publisher=Alfred Knopf Publishing|location=New York |year=1995 |pages= |isbn=0-679-43386-4}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |author=Limerick, Patrick |author2=Puska, Claudia |year=2003 |url=http://www.centerwest.org/publications/pdf/science.pdf |title=Making the Most of Science in the American West |journal=Report from the Center |issue=5 |publisher=Center of the American West |location=] |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080910045053/http://www.centerwest.org/publications/pdf/science.pdf |archive-date=September 10, 2008 }} | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Norman, David|authorlink=David B. Norman|title=Dinosaur!|year=1991|publisher=Prentice Hill|location=New York|isbn=0-13-218140-1}} | |||

| *{{cite news |last=Marsh |first=O. C. |author-link=Othniel Charles Marsh |title=Wrong End Foremost |work=] |date=January 19, 1890 |url=http://www.oceansofkansas.com/NYHerald.html |access-date=February 2, 2009 }}—(] maintained by M. J. Everhart). | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Osborn, Henry Fairfield|authorlink=Henry Fairfield Osborn|year=1978|title=Cope: Master Naturalist : Life and Letters of Edward Drinker Cope, With a Bibliography of His Writings|publisher=Ayer Company Publishing|location=]|isbn=0-405-10735-8}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Martin, Anthony J. |year=2006 |title=Introduction to the Study of Dinosaurs |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-4051-3413-2}} | |||

| *{{cite journal|author=Penick, James|year=1971|month=August|url=http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1971/5/1971_5_4.shtml|title=Professor Cope vs. Professor Marsh|journal=]|volume=22|issue=5}} | |||

| *{{cite web |author=Mondor, Colleen |date=January 1, 2006 |url=http://www.bookslut.com/features/2006_01_007441.php |title=Comic Books and Thunder Lizards |publisher=BookSlut |access-date=January 20, 2008 |archive-date=April 22, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150422132230/http://www.bookslut.com/features/2006_01_007441.php |url-status=dead }} | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Preston, Douglas|year=1993|title=Dinosaurs in the Attic: An Excursion Into The American Museum of Natural History|publisher=Macmillan Publishers|location=United States of America|isbn=0-312-10456-1}} | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Norell |first=Mark A. |author2=Gaffney, Eric S. |author3=Dingus, Lowell |title=Discovering Dinosaurs in the American Museum of Natural History |publisher=] |location=New York |year=1995 |isbn=978-0-679-43386-6 |url=https://archive.org/details/discoveringdinos00nore_0 }} | |||

| *{{cite journal|author=Rajewski, Genevieve|year=2008|month=May|title=Where Dinosaurs Roamed|journal=]|publisher=|volume=39|issue=2|pages=20–26}} | |||

| *{{cite book|author= |

*{{cite book |author=Norman, David |author-link=David B. Norman |title=Dinosaur! |year=1991 |publisher=] |location=New York |isbn=978-0-13-218140-2}} | ||

| *{{cite book|author= |

*{{cite book |author=Osborn, Henry Fairfield |author-link=Henry Fairfield Osborn |year=1978 |title=Cope: Master Naturalist : Life and Letters of Edward Drinker Cope, With a Bibliography of His Writings |publisher=Ayer Company Publishing |location=] |isbn=978-0-405-10735-1}} | ||

| *{{cite journal |author=Penick, James |date=August 1971 |url=http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1971/5/1971_5_4.shtml |title=Professor Cope vs. Professor Marsh |journal=] |volume=22 |issue=5 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100101153430/http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/1971/5/1971_5_4.shtml |archive-date=January 1, 2010 |df=mdy-all }} | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Trefil, James S|authorlink=James Trefil|year=2003|title=The Nature of Science: An A-Z Guide to the Laws and Principles Governing Our Universe|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Books|isbn=0-618-31938-7}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Preston, Douglas |year=1993 |title=Dinosaurs in the Attic: An Excursion into the American Museum of Natural History |publisher=] |location=United States |isbn=978-0-312-10456-6}} | |||

| *{{cite web|author=Waggoner, Ben|date=1999-10-22|url=http://palaeo-electronica.org/1999_2/books/bone_wars.htm|title=Bone Wars & Two Tiny Claws|publisher=Palaeontologia Electronica|accessdate=2008-02-03}} | |||

| *{{cite journal |author=Rajewski, Genevieve |date=May 2008 |title=Where Dinosaurs Roamed |journal=] |volume=39 |url=http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/where-dinosaurs-roamed-36987235/ |issue=2 |pages=20–26 }} | |||

| *{{cite book|author=Wallace, David Rains|year=1999|title=The Bonehunters' Revenge: Dinosaurs, Greed, and the Greatest Scientific Feud of the Gilded Age|publisher=Houghton Mifflin Books|isbn=0-618-08240-9}} | |||

| *{{cite book|author= |

*{{cite book |author=Shor, Elizabeth |year=1974 |title=The Fossil Feud Between E. D. Cope and O. C. Marsh |publisher=Exposition Press |location=Detroit, Michigan |isbn=978-0-682-47941-7}} | ||

| *{{cite book |author=Sterling, Keir |year=1997 |title=Biographical Dictionary of American and Canadian Naturalists and Environmentalists |publisher=Greenwood Publishing Group |isbn=978-0-313-23047-9 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/biographicaldict0000unse_p7q0 }} | |||

| *{{cite web|author=|date=|url=http://www.ansp.org/museum/leidy/paleo/bone_wars.php|title=Bone Wars: The Cope-Marsh Rivalry|publisher=]|accessdate=2008-02-19}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Thomson, Keith Stewart |year=2008 |title=The Legacy of the Mastodon: The Golden Age of Fossils in America |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-300-11704-2}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Trefil, James S. |author-link=James Trefil |year=2003 |title=The Nature of Science: An A-Z Guide to the Laws and Principles Governing Our Universe |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-618-31938-1 |url=https://archive.org/details/natureofsciencea00tref }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Wallace, David Rains |year=1999 |title=The Bonehunters' Revenge: Dinosaurs, Greed, and the Greatest Scientific Feud of the Gilded Age |publisher=Houghton Mifflin Books |isbn=978-0-618-08240-7}} | |||

| *{{cite book |author=Wilford, John Noble |year=1985 |title=The Riddle of the Dinosaur |location=New York |publisher=Knopf Publishing |isbn=978-0-394-74392-9 |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/riddleofdinosaur0000wilf }} | |||

| *{{cite web |url=http://www.ansp.org/museum/leidy/paleo/bone_wars.php |title=Bone Wars: The Cope-Marsh Rivalry |publisher=] |access-date=February 19, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080119125809/http://www.ansp.org/museum/leidy/paleo/bone_wars.php <!-- Added by H3llBot --> |archive-date=January 19, 2008 }} | |||

| *{{cite journal |date=January 7, 2006 |title=Feedback |journal=] |issue=2533 |page=64 |issn=0262-4079 |url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg18925332.300-feedback.html |access-date=February 5, 2009 }} | |||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Spoken Misplaced Pages|Bone_Wars_spoken_Wikipedia_article_(English).ogg|date=2018-10-25}} | |||

| {{portalpar|Dinosaurs}} | |||

| * on ], March 2020 | |||

| * Illustrated on the Bone Wars. | |||

| * {{dmoz|Science/Earth_Sciences/Paleontology/History/Bone_Wars/}} | |||

| {{Portal|Dinosaurs}} | |||

| {{Commons category}} | |||

| * on the Bone Wars. | |||

| * View works by online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library. | |||

| * View works by online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library. | |||

| *{{spaced ndash}} An ] Documentary | |||

| * -SciGuys Podcast | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 03:06, 18 November 2024

19th century period of competitive fossil hunting This article is about the period of competitive fossil hunting during the late 19th century. For the series of armed conflicts between the Dutch and the state of Bone on Sulawesi, see Dutch–Bone wars. For the book by Tom Rea, see Bone Wars (book). For the 2011 documentary film, see Dinosaur Wars (film).

The Bone Wars, also known as the Great Dinosaur Rush, was a period of intense and ruthlessly competitive fossil hunting and discovery during the Gilded Age of American history, marked by a heated rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope (of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia) and Othniel Charles Marsh (of the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale). Each of the two paleontologists used underhanded methods to try to outdo the other in the field, resorting to bribery, theft, and the destruction of bones. Each scientist also sought to ruin his rival's reputation and cut off his funding, using attacks in scientific publications.

Their search for fossils led them west to rich bone beds in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming. From 1877 to 1892, both paleontologists used their wealth and influence to finance their own expeditions and to procure services and dinosaur bones from fossil hunters. By the end of the Bone Wars, both men had exhausted their funds in the pursuit of paleontological supremacy.

Cope and Marsh were financially and socially ruined by their attempts to outcompete and disgrace each other, but they made important contributions to science and the field of paleontology and provided substantial material for further work—both scientists left behind many unopened boxes of fossils after their deaths. The efforts of the two men led to 136 new species of dinosaurs being discovered and described. The products of the Bone Wars resulted in an increase in knowledge of prehistoric life, and sparked the public's interest in dinosaurs, leading to continued fossil excavation in North America in the decades to follow. Many historical books and fictional adaptations have been published about this period of intense fossil-hunting activity.

History

Background

At first, the relationship between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh was amicable. They met in Berlin in 1864 and spent several days together. They even named species after each other. Over time their relations soured, due in part to their strong personalities. Cope was known to be pugnacious and possessed a quick temper; Marsh was slower, more methodical, and introverted. Both were quarrelsome and distrustful. Their differences also extended into the scientific realm, as Cope was a firm supporter of Neo-Lamarckism while Marsh supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution by natural selection. Even at the best of times, both men were inclined to look down on each other subtly. As one observer put it, "The patrician Edward may have considered Marsh not quite a gentleman. The academic Othniel probably regarded Cope as not quite a professional."

Cope and Marsh came from very different backgrounds. Cope was born into a wealthy and influential Quaker family based in Philadelphia. Although his father wanted his son to work as a farmer, Cope distinguished himself as a naturalist. In 1864, already a member of the Academy of Natural Sciences, Cope became a professor of zoology at Haverford College and joined Ferdinand Hayden on his expeditions west. In contrast, Marsh would have grown up poor, the son of a struggling family in Lockport, New York, had it not been for the benefaction of his uncle, philanthropist George Peabody. Marsh persuaded his uncle to build the Peabody Museum of Natural History, placing Marsh as head of the museum. Combined with the inheritance he received from Peabody upon his death in 1869, Marsh was financially comfortable (although, partly because of Peabody's stern views on marriage, Marsh would remain a lifelong bachelor).

On one occasion, the two scientists had gone on a fossil-collecting expedition to Cope's marl pits in New Jersey, where William Parker Foulke had discovered the holotype specimen of Hadrosaurus foulkii, described by the paleontologist Joseph Leidy (under whom Cope had studied comparative anatomy); this was one of the first American dinosaur finds, and the pits were still rich with fossils. Though the two parted amicably, Marsh secretly bribed the pit operators to divert future fossil finds to him, instead of Cope. The two began attacking each other in papers and publications, and their personal relations deteriorated. Marsh humiliated Cope by pointing out that his reconstruction of the plesiosaur Elasmosaurus was flawed, with the head placed where the tail should have been (or so he claimed, 20 years later; it was Leidy who published the correction shortly afterwards). Cope, in turn, began collecting in what Marsh considered his private bone-hunting turf in Kansas and Wyoming, further damaging their relationship.

1872–1877: Early expeditions

In the 1870s, Cope's and Marsh's professional attentions were directed to the American West by word of large fossil finds. Using his influence in Washington, D.C., Cope was granted a position on the U.S. Geological Survey under Ferdinand Hayden. While the position offered no salary, it afforded Cope a great opportunity to collect fossils in the West and publish his finds. Cope's flair for dramatic writing suited Hayden, who needed to make a popular impression with the official survey reports. In June 1872 Cope set off on his first trip, intending to observe the Eocene bone beds of Wyoming for himself. This caused a rift between Cope, Hayden, and Leidy. It was Leidy who had enjoyed receiving many of the fossils from Hayden's collection until Cope joined the survey, and now Cope was hunting for fossils in Leidy's staked territory—at the same time Leidy was to be collecting. Hayden attempted to smooth things over with Leidy in a letter:

I asked him not to go into that field, that you were going there. He laughed at the idea of being restricted to any locality and said he intended to go whether I aided him or not. I was anxious to secure the cooperation of such a worker as an honor to my corps. I could not be responsible for the field he selected in as much as I pay him no salary and a portion of his expenses. You will see therefore that while it is not a pleasant thing to work in competition with others it seems almost a necessity. You can sympathize.

Cope took his family with him as far as Denver, while Hayden tried to keep Cope and Leidy from prospecting in the same area. Following a tip from geologist Fielding Bradford Meek, Cope also intended to investigate reports of bones Meek had found near Black Buttes Station and the railroad. Cope found the site and some skeletal remains of a dinosaur he dubbed Agathaumas sylvestris. Believing he had the full support of Hayden and the survey, Cope then traveled to Fort Bridger in June, only to find that the men, wagons, horses, and equipment he expected were not there. Cope cobbled together an outfit at his own expense, consisting of two teamsters, a cook, and a guide, along with three men from Chicago who were interested in studying with him. As it turned out, two of Cope's men were in fact in the employ of Marsh. When the rival paleontologist found out his own men were taking Cope's money, he was furious. While the men tried to assure Marsh they were still his men (one suggested he took the job in order to lead Cope away from good fossils), Marsh's laziness in soliciting firm agreements and payments may have caused them to seek other work. Cope's journey took the expedition through rugged country only Hayden had surveyed, and he discovered dozens of new species. Meanwhile, one of Marsh's men accidentally forwarded some of his material to Cope instead. On receiving the fossils, Cope sent them back to Marsh, but further damage had been done to their relationship.

Any pretense of cordiality between Cope and Marsh ended in 1872, and by spring 1873 open hostility ensued. At the same time, Leidy, Cope and Marsh were making great discoveries of ancient reptiles and mammals in the Western bone beds. The paleontologists had a habit of making hasty telegrams eastward describing their finds, only publishing fuller accounts after returning from trips. Among the new specimens described by the men were Uintatherium, Loxolophodon, Eobasileus, Dinoceras, and Tinoceras. The problem was that many of these finds were not uniquely different from each other; in fact, Cope and Marsh knew that some of the fossils they were collecting had already been found by the others. As it turned out, many of Marsh's names were valid, while none of Cope's were. Marsh also placed the new species into a new order of mammals, Cinocerea. Cope was humiliated and powerless to stop his rival's changes. Instead, he published a broad analytical study where he proposed a new plan of classification for the Eocene mammals, in which he discarded Marsh's genera in favor of his own. Marsh remained steadfast and continued to claim that all of Cope's names for Dinocerata were incorrect.

While the scientists argued over classifications and nomenclature, they also returned west for more fossils. Marsh made his last trip backed by Yale in 1873, with a large group of thirteen students accompanying him, protected by a group of soldiers who wanted to make a show of force to the Sioux tribe. Due to concerns over his more lavish and expensive expeditions in years past, Marsh had the students pay their own way, and the trip cost Yale only $1857.50, far less than the $15,000 (over $200,000 in modern currency) that Marsh had claimed for the previous expedition. This excursion would prove to be Marsh's last: for the rest of the Bone Wars, Marsh preferred to enlist the services of local collectors. Though he had enough bones to study for years, the scientist's appetite for more would grow. Cope was even more prolific in his collecting that season than he was in 1872, although Marsh's penchant for cultivating collectors of his own meant that at Bridger his rival was persona non grata. Tired of working under Hayden, Cope found a paying job with the Army Corps of Engineers, but was limited by this federal association; while Cope had to tag along on surveys, Marsh could collect wherever he pleased.

The two scientists' attention turned to the Dakota Territory in the mid-1870s, where the discovery of gold in the Black Hills increased Native American tensions with the United States. Marsh, desiring the fossils found in that region, became embroiled in Army-Indian politics. In order to gain the support of Chief Red Cloud of the Sioux to prospect, Marsh promised Red Cloud payment for fossils collected and that he would return to Washington, D.C. and lobby on their behalf about their improper treatment. In the end, Marsh slipped out of camp and according to his own (possibly romanticized) accounts, amassed cartloads of fossils and retreated just before a hostile Miniconjou party arrived. Marsh, for his part, did lobby the Interior Department and President Ulysses S. Grant on behalf of Red Cloud, but his motives might have been to make a name for himself against the unpopular Grant administration. By 1875, both Cope and Marsh paused in their collecting, feeling financial strain and needing to catalogue their backlogged finds, but new discoveries would return them to the West before decade's end.

1877–1892: Como Bluff finds

In 1877, Marsh received a letter from Arthur Lakes, a schoolteacher in Golden, Colorado. Lakes reported that he had been hiking in the mountains near the town of Morrison, when he and his friend, H. C. Beckwith, discovered massive bones embedded in the rock. Lakes further advised that the bones were "apparently a vertebra and a humerus bone of some gigantic saurian." While awaiting Marsh's reply, Lakes dug up more "colossal" bones and sent them to New Haven. As Marsh was slow to respond, Lakes also sent a shipment of bones to Cope.

When Marsh responded to Lakes, he paid the prospector $100, urging him to keep the finds a secret. Learning that Lakes had corresponded with Cope, Marsh sent his field collector Benjamin Mudge to Morrison to secure Lakes' services. Marsh published a description of Lakes' discoveries in the American Journal of Science on July 1, and before Cope could publish his own interpretation of the finds, Lakes wrote to him that the bones should be shipped to Marsh, a severe insult to Cope.

A second letter arrived from the west, this time addressed to Cope. The writer, O. W. Lucas, was a naturalist who had been collecting plants near Cañon City, Colorado when he came upon an assortment of fossil bones. After receiving more samples from Lucas, Cope concluded the dinosaurs were large herbivores, gleefully noting that the specimen was larger than any other previously described, including Lakes' discovery. Hearing of Lucas' finds, Marsh instructed Mudge and a former student, Samuel Wendell Williston, to set up a quarry on his behalf near Cañon. Unfortunately for Marsh, he learned from Williston that Lucas was finding the best bones and refused to quit Cope to come work for Marsh. Marsh ordered Williston back to Morrison, where Marsh's small quarry collapsed and nearly killed his assistants. This setback would have dried up Marsh's bone supply from the west, if not for receipt of a third letter.

At the time of Lakes' discoveries, the First transcontinental railroad was being built through a remote area of Wyoming. Marsh's letter was from two men identifying themselves as Harlow and Edwards, workers on the Union Pacific Railroad. Their real names were William Harlow Reed (1848–1915) and William Edwards Carlin. The two men claimed they had found large numbers of fossils in Como Bluff, and warned that there were others in the area "looking for such things", which Marsh took to mean Cope. Williston, who had just wearily arrived in Kansas after the collapse of the Morrison mine, was quickly dispatched to Como Bluff by Marsh. His former student sent back a message, confirming the large quantities of bones and that it was Cope's men snooping around the area. Wary of repeating the same mistakes he had made with Lakes, Marsh quickly sent money to the two new bone hunters and urged them to send additional fossils. Williston struck a preliminary bargain with Carlin and Reed (who had been unable to cash Marsh's check due to it being made out to their pseudonyms), but Carlin decided he would head to New Haven to deal with Marsh directly. Marsh drew up a contract calling for a set monthly fee, with additional cash bonuses to Carlin and Reed possible, depending on the importance of the finds. Marsh also reserved the right to send his own "superintendents" to supervise the digging if needed and advised the men to try to keep Cope out of the region. Despite a face-to-face meeting, Carlin failed to negotiate better terms from Marsh. The paleontologist procured Carlin's and Reed's services, but seeds of resentment were sown as the bone hunters felt Marsh had bullied them into the deal. Marsh's investment in the Como Bluff region soon produced rich results. While Marsh's own collectors headed east for the winter, Reed sent carloads of bones by rail to Marsh throughout 1877. Marsh described and named dinosaurs such as Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, and Apatosaurus in the December 1877 issue of the American Journal of Science.

Despite Marsh's precautions against alerting his rival to Como Bluff's rich bone beds, word of the discoveries rapidly spread. This was at least partly due to Carlin and Reed helping spread the rumors. They leaked information to the Laramie Daily Sentinel, which published an article about the finds in April 1878 that exaggerated the price Marsh had paid for the bones, possibly to raise prices and demand for more bones. Marsh, attempting to cover the leak, learned from Williston that Carlin and Reed had been visited by a man ostensibly working for Cope by the name of "Haines". After learning of the Como Bluff discoveries, Cope sent "dinosaur rustlers" to the area in an attempt to quietly steal fossils from under Marsh's nose. During the winter of 1878, Carlin's dissatisfaction with Marsh's sporadic sending of payment reached a head, and he began working for Cope instead.