| Revision as of 00:36, 10 September 2008 editRod57 (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers32,800 editsm →See also: (Alphabetic list)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 15:50, 8 December 2024 edit undo2601:602:b01:8455:912b:7767:baa0:8dd0 (talk) →Recent observations | ||

| (287 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2019}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{short description|Observational astronomy performed with gamma rays}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] in five years of observation (2009 to 2013).]] | |||

| '''Gamma-ray astronomy''' is the ] study of the ] with ]. | |||

| ] (EGRET) of the ] (CGRO) satellite (1991–2000).]] | |||

| ] (EGRET), in gamma rays of greater than 20 MeV. These are produced by ] bombardment of its surface.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://heasarc.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/cgro/epo/news/gammoon.html |title=EGRET Detection of Gamma Rays from the Moon |publisher=Goddard Space Flight Center |date=August 1, 2005}}</ref>]] | |||

| '''Gamma-ray astronomy''' is a subfield of ] where scientists ] and study ]s and phenomena in ] which emit cosmic ] in the form of ]s,<ref group=nb>Astronomical literature generally hyphenates "gamma-ray" when used as an adjective, but uses "gamma ray" without a hyphen for the noun.</ref> i.e. ]s with the highest ] (above 100 ]) at the very shortest wavelengths. Radiation below 100 keV is classified as ]s and is the subject of ]. | |||

| <!--sources ---> | |||

| == Early history == | |||

| In most cases, gamma rays from ]s and ] fall in the MeV range, but it's now known that solar flares can also produce gamma rays in the GeV range, contrary to previous beliefs. Much of the detected gamma radiation stems from collisions between ] gas and ]s within our ]. These gamma rays, originating from diverse mechanisms such as ], the ] and in some cases ],<ref>for example, supernova ] emitted an "afterglow" of gamma-ray photons from the decay of newly made radioactive ] ejected into space in a cloud, by the explosion. <br /> {{cite web |url=http://science.hq.nasa.gov/kids/imagers/ems/gamma.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070430231515/http://science.hq.nasa.gov/kids/imagers/ems/gamma.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=April 30, 2007 |title=The Electromagnetic Spectrum - Gamma-rays |publisher=] |access-date=November 14, 2010}}</ref> occur in regions of extreme temperature, density, and magnetic fields, reflecting violent astrophysical processes like the decay of neutral ]s. They provide insights into extreme events like ]e, ]e, and the behavior of matter in environments such as ]s and ]s. A huge number of gamma ray emitting high-energy systems like ]s, ]s, ]s, ] stars, remnants of supernova, clusters of galaxies, including the ] and the ] (the most powerful source so far), have been identified, alongside an overall diffuse ] along the plane of the ] galaxy. Cosmic radiation with the highest energy triggers electron-photon cascades in the atmosphere, while lower-energy gamma rays are only detectable above it. ]s, like ], are transient phenomena challenging our understanding of high-energy ]es, ranging from microseconds to several hundred seconds. | |||

| Long before experiments could detect ]s emitted by cosmic sources, scientists had known that the universe should be producing these ]s. Work by ] and H. Primakoff in 1948, ] and I.B. Hutchinson in 1952, and, especially, Morrison in 1958 had led scientists to believe that a number of different processes which were occurring in the universe would result in gamma-ray emission. These processes included ] interactions with ], ] explosions, and interactions of energetic ]s with ]s. However, it was not until the 1960s that our ability to actually detect these emissions came to pass. | |||

| <!--detection--> | |||

| Gamma-rays coming from space are mostly absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere. So gamma-ray astronomy could not develop until it was possible to get our detectors above all or most of the atmosphere, using ]s or spacecraft. The first gamma-ray telescope carried into orbit, on the ] satellite in 1961, picked up fewer than 100 cosmic gamma-ray photons. These appeared to come from all directions in the Universe, implying some sort of uniform "gamma-ray background". Such a background would be expected from the interaction of cosmic rays (very energetic charged particles in space) with gas found between the stars. | |||

| Gamma rays are difficult to detect due to their high energy and their blocking by the Earth’s atmosphere, necessitating balloon-borne detectors and artificial satellites in space. Early experiments in the 1950s and 1960s used balloons to carry instruments to access altitudes where the atmospheric absorption of gamma rays is low, followed by the launch of the first gamma-ray satellites: ] (1972) and ] (1975). These were defense satellites originally designed to detect gamma rays from secret nuclear testing, but they luckily discovered puzzling gamma-ray bursts coming from deep space. In the 1970s, satellite observatories found several gamma-ray sources, among which a very strong source called ] was later identified as a pulsar in proximity. The ] (launched in 1991) revealed numerous gamma-ray sources in space. Today, both ground-based observatories like the ] array and space-based telescopes like the ] (launched in 2008) contribute significantly to gamma-ray astronomy. This interdisciplinary field involves collaboration among physicists, astrophysicists, and engineers in projects like the ] (H.E.S.S.), which explores extreme astrophysical environments like the vicinity of ]s in ]. | |||

| <!-- benefits--> | |||

| The first true astrophysical gamma-ray sources were solar flares, which revealed the strong 2.223 MeV line predicted by Morrison. This line results from the formation of deuterium via the union of a neutron and proton; in a solar flare the neutrons appear as secondaries from interactions of high-energy ions accelerated in the flare process. These first gamma-ray line observations were from ], ], and the ], the latter spacecraft launched in 1980. The solar observations inspired theoretical work by ] and others. | |||

| Studying gamma rays provides valuable insights into extreme astrophysical environments, as observed by the H.E.S.S. Observatory. Ongoing research aims to expand our understanding of gamma-ray sources, such as blazars, and their implications for cosmology. As GeV gamma rays are important in the study of extra-solar, and especially ], astronomy, new observations may complicate some prior models and findings.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.sciencenews.org/article/strange-gamma-rays-sun-magnetic-fields |title=Strange gamma rays from the sun may help decipher its magnetic fields |work=Science News |first=Lisa |last=Grossman |date=August 24, 2018}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/feature/goddard/2017/nasas-fermi-sees-gamma-rays-from-hidden-solar-flares |title=NASA's Fermi Sees Gamma Rays from 'Hidden' Solar Flares |publisher=NASA |first=Francis |last=Reddy |date=January 30, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| <!--future outlook--> | |||

| Significant gamma-ray emission from our galaxy was first detected in 1967 by the gamma-ray detector aboard the ] satellite. It detected 621 events attributable to cosmic gamma-rays. However, the field of gamma-ray astronomy took great leaps forward with the ] (1972) and the ] (1975-1982) satellites. These two satellites provided an exciting view into the high-energy universe (sometimes called the 'violent' universe, because the kinds of events in space that produce gamma-rays tend to be explosions, high-speed collisions, and such). They confirmed the earlier findings of the gamma-ray background, produced the first detailed map of the sky at gamma-ray wavelengths, and detected a number of point sources. However, the poor resolution of the instruments made it impossible to identify most of these point sources with individual stars or stellar systems. | |||

| Future developments in gamma-ray astronomy will integrate data from ] and ] observatories (]), enriching our understanding of cosmic events like neutron star mergers. Technological advancements, including advanced ] designs, better ] technologies, improved trigger systems, faster ], high-performance photon detectors like ]s (SiPMs), alongside innovative data processing algorithms like time-tagging techniques and ] methods, will enhance ] and ]. ] algorithms and ] analytics will facilitate the extraction of meaningful insights from vast datasets, leading to discoveries of new gamma-ray sources, identification of specific gamma-ray signatures, and improved modeling of gamma-ray emission mechanisms. Future missions may include space telescopes and lunar gamma-ray observatories (taking advantage of the ]'s lack of atmosphere and stable environment for prolonged observations), enabling observations in previously inaccessible regions. The ground-based ] project, a next-generation gamma ray observatory which will incorporate many of these improvements and will be ten times more sensitive, is planned to be fully operational by 2025.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.eso.org/public/belgium-fr/teles-instr/paranal-observatory/ctao/?lang |website=ESO.org |title=CTAO — the World's Most Powerful Ground-Based Gamma-Ray Observatory |access-date=23 May 2024}}</ref> | |||

| == |

==Early history== | ||

| Long before experiments could detect gamma rays emitted by cosmic sources, scientists had known that the universe should be producing them. Work by ] and ] in 1948, ] and I.B. Hutchinson in 1952, and, especially, ] in 1958<ref>{{cite journal |title=On gamma-ray astronomy |journal=Il Nuovo Cimento |first=Philip |last=Morrison |volume=7 |issue=6 |pages=858–865 |date=March 1958 |doi=10.1007/BF02745590 |bibcode=1958NCim....7..858M|s2cid=121118803 }}</ref> had led scientists to believe that a number of different processes which were occurring in the universe would result in gamma-ray emission. These processes included ] interactions with ], ] explosions, and interactions of energetic ]s with ]s. | |||

| Perhaps the most spectacular discovery in gamma-ray astronomy came in the late 1960s and early 1970s from a constellation of defense satellites which were put into orbit for a completely different reason. Detectors on board the ] satellite series, designed to detect flashes of gamma-rays from nuclear bomb blasts, began to record bursts of gamma-rays -- not from the vicinity of the Earth, but from deep space. Today, these ]s are seen to last for fractions of a second to minutes, popping off like cosmic flashbulbs from unexpected directions, flickering, and then fading after briefly dominating the gamma-ray sky. Studied for over 25 years now with instruments on board a variety of satellites and space probes, including Soviet ] spacecraft and the ], the sources of these enigmatic high-energy flashes remain a mystery. They appear to come from far away in the Universe, and currently the most likely theory seems to be that at least some of them come from so-called '']'' explosions - supernovas creating ]s rather than ]s. | |||

| However, it was not until the 1960s that our ability to actually detect these emissions came to pass.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://source.wustl.edu/2009/12/washington-university-physicists-are-closing-in-on-the-origin-of-cosmic-rays/ |title=Washington University physicists are closing in on the origin of cosmic rays |publisher=Washington University in St. Louis |first=Diana |last=Lutz |date=December 7, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Most gamma rays coming from space are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, so gamma-ray astronomy could not develop until it was possible to get detectors above all or most of the atmosphere using ]s and spacecraft. The first gamma-ray telescope carried into orbit, on the ] satellite in 1961, picked up fewer than 100 cosmic gamma-ray photons. They appeared to come from all directions in the Universe, implying some sort of uniform "gamma-ray background". Such a background would be expected from the interaction of cosmic rays (very energetic charged particles in space) with interstellar gas. | |||

| == Recent and current observatories == | |||

| During its ] program in 1977, ] announced plans to build a "great observatory" for gamma-ray astronomy. The ] (CGRO) was designed to take advantage of the major advances in detector technology during the 1980s, and was launched in 1991. The satellite carried four major instruments which have greatly improved the spatial and temporal resolution of gamma-ray observations. The CGRO provided large amounts of data which are being used to improve our understanding of the high-energy processes in our Universe. CGRO was de-orbited in June 2000 as a result of the failure of one of its stabilizing ]s. | |||

| The first true astrophysical gamma-ray sources were solar flares, which revealed the strong 2.223 MeV line predicted by Morrison. This line results from the formation of deuterium via the union of a neutron and proton; in a solar flare the neutrons appear as secondaries from interactions of high-energy ions accelerated in the flare process. These first gamma-ray line observations were from ], ], and the ], the latter spacecraft launched in 1980. The solar observations inspired theoretical work by ] and others.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l1/history_gamma.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/19980520035819/http://imagine.gsfc.nasa.gov/docs/science/know_l1/history_gamma.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=May 20, 1998 |title=The History of Gamma-ray Astronomy |publisher=NASA |access-date=November 14, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| ] was launched in 1996 and deorbited in 2003. | |||

| It predominantly studied X-rays, but also observed gamma-ray bursts. | |||

| By identifying the first non-gamma ray counterparts to gamma-ray bursts, it opened the way for their precise position determination and optical observation of their fading remnants in distant galaxies. | |||

| The ] 2 (HETE-2) was launched in October 2000 (on a nominally 2 yr mission) and was still operational in March 2007. | |||

| ], a NASA spacecraft, was launched in 2004 and carries the BAT instrument for gamma-ray burst observations. | |||

| Following BeppoSAX and HETE-2, it has observed numerous x-ray and optical counterparts to bursts, leading to distance determinations and detailed optical follow-up. | |||

| These have established that most bursts originate in the explosions of massive stars (]s and ]s) in distant galaxies. | |||

| Significant gamma-ray emission from our galaxy was first detected in 1967<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.scienceclarified.com/Ga-He/Gamma-Ray.html |title=Gamma ray |work=Science Clarified |access-date=November 14, 2010}}</ref> by the detector aboard the ] satellite. It detected 621 events attributable to cosmic gamma rays. However, the field of gamma-ray astronomy took great leaps forward with the ] (1972) and the ] (1975–1982) satellites. These two satellites provided an exciting view into the high-energy universe (sometimes called the 'violent' universe, because the kinds of events in space that produce gamma rays tend to be high-speed collisions and similar processes). They confirmed the earlier findings of the gamma-ray background, produced the first detailed map of the sky at gamma-ray wavelengths, and detected a number of point sources. However the resolution of the instruments was insufficient to identify most of these point sources with specific visible stars or stellar systems. | |||

| Currently the main space-based gamma-ray observatories are the INTErnational Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory, (]), and the ] (GLAST). | |||

| INTEGRAL is an ESA mission with additional contributions from ], Poland, USA and Russia. | |||

| It was launched on ] ]. | |||

| NASA launched ] on 11 June 2008. | |||

| In includes LAT, the Large Area Telescope, and GBM, the GLAST Burst Monitor, for studying gamma-ray bursts. | |||

| A discovery in gamma-ray astronomy came in the late 1960s and early 1970s from a constellation of military defense satellites. Detectors on board the ] satellite series, designed to detect flashes of gamma rays from nuclear bomb blasts, began to record bursts of gamma rays from deep space rather than the vicinity of the Earth. Later detectors determined that these ]s are seen to last for fractions of a second to minutes, appearing suddenly from unexpected directions, flickering, and then fading after briefly dominating the gamma-ray sky. Studied since the mid-1980s with instruments on board a variety of satellites and space probes, including Soviet ] spacecraft and the ], the sources of these enigmatic high-energy flashes remain a mystery. They appear to come from far away in the Universe, and currently the most likely theory seems to be that at least some of them come from so-called '']'' explosions—supernovas creating ]s rather than ]s. | |||

| Very energetic gamma rays, with photon energies over ~30 GeV, can also be detected by ground based experiments. | |||

| The extremely low photon fluxes at such high energies require detector effective areas that are impractically large for current space-based instruments. | |||

| Fortunately such high-energy photons produce extensive showers of secondary particles in the atmosphere that can be observed on the ground, both directly by radiation counters and optically | |||

| via the ] the ultra-relativistic shower particles emit. | |||

| The Imaging Atmospheric Cherenkov Telescope technique currently achieves the highest sensitivity. The ], a steady source of so called TeV gamma-rays, was first detected in 1989 by the Whipple Observatory at Mt. Hopkins, in ] in the USA. | |||

| Modern Cherenkov telescope experiments like ], ], ], and CANGAROO III can detect the Crab Nebula in a few minutes. | |||

| The most energetic photons (up to 16 ]) observed from an extragalactic object originate from the ] ] (Mrk 501). | |||

| These measurements were done by the High-Energy-Gamma-Ray Astronomy (]) air ] telescopes. | |||

| Nuclear ]s were observed from the ]s of August 4 and 7, 1972, and November 22, 1977.<ref name=Ramaty>{{cite journal |title=Nuclear gamma-rays from energetic particle interactions |journal=Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series |first1=R. |last1=Ramaty |first2=B. |last2=Kozlovsky |first3=R. E. |last3=Lingenfelter |display-authors=1 |volume=40 |pages=487–526 |date=July 1979 |doi=10.1086/190596 |bibcode=1979ApJS...40..487R|hdl=2060/19790005667 |doi-access=free |hdl-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Gamma-ray astronomy observations are still limited by non-gamma ray backgrounds at lower energies, and, at higher energy, by the number of photons that can be detected. | |||

| A ] is an explosion in a solar atmosphere and was originally detected visually in the ]. Solar flares create massive amounts of radiation across the full electromagnetic spectrum from the longest wavelength, ]s, to high energy gamma rays. The correlations of the high energy electrons energized during the flare and the gamma rays are mostly caused by nuclear combinations of high energy protons and other heavier ions. These gamma rays can be observed and allow scientists to determine the major results of the energy released, which is not provided by the emissions from other wavelengths.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://hesperia.gsfc.nasa.gov/hessi/flares.htm |title=Overview of Solar Flares |publisher=] |access-date=November 14, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Larger area detectors and better background suppression are essential for progress in the field. | |||

| See also ] detection of a ]. | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] (Alphabetic list) | |||

| * ], GLAST. | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Detector technology== | |||

| == External links == | |||

| Observation of gamma rays first became possible in the 1960s. Their observation is much more problematic than that of X-rays or of visible light, because gamma-rays are comparatively rare, even a "bright" source needing an observation time of several minutes before it is even detected, and because gamma rays are difficult to focus, resulting in a very low resolution. The most recent generation of gamma-ray telescopes (2000s) have a resolution of the order of 6 arc minutes in the GeV range (seeing the ] as a single "pixel"), compared to 0.5 arc seconds seen in the low energy X-ray (1 keV) range by the ] (1999), and about 1.5 arc minutes in the high energy X-ray (100 keV) range seen by ] (2005). | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| Very energetic gamma rays, with photon energies over ~30 GeV, can also be detected by ground-based experiments. The extremely low photon fluxes at such high energies require detector effective areas that are impractically large for current space-based instruments. Such high-energy photons produce extensive showers of secondary particles in the atmosphere that can be observed on the ground, both directly by radiation counters and optically via the ] which the ultra-relativistic shower particles emit. The ] technique currently achieves the highest sensitivity. | |||

| ] | |||

| Gamma radiation in the TeV range emanating from the ] was first detected in 1989 by the ] at ], in ] in the USA. Modern Cherenkov telescope experiments like ], ], ], and CANGAROO III can detect the Crab Nebula in a few minutes. The most energetic photons (up to 16 ]) observed from an extragalactic object originate from the ], ] (Mrk 501). These measurements were done by the High-Energy-Gamma-Ray Astronomy (]) air ] telescopes. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Gamma-ray astronomy observations are still limited by non-gamma-ray backgrounds at lower energies, and, at higher energy, by the number of photons that can be detected. Larger area detectors and better background suppression are essential for progress in the field.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=3EOsVn_KbJ8C&pg=PA191 |title=Reviews in Modern Astronomy: Cosmic Matter |publisher=Wiley |last1=Krieg |first1=Uwe |editor=Siegfried Röser |volume=20 |page=191 |date=2008 |isbn=978-3-527-40820-7}}</ref> A discovery in 2012 may allow focusing gamma-ray telescopes.<ref name=wogan/> At photon energies greater than 700 keV, the index of refraction starts to increase again.<ref name=wogan>{{cite news |url=https://physicsworld.com/a/silicon-prism-bends-gamma-rays/ |title=Silicon 'prism' bends gamma rays |website=PhysicsWorld.com |first=Tim |last=Wogan |date=May 9, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==1980s to 1990s== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| On June 19, 1988, from ] (50° 20' W, 21° 20' S) at 10:15 UTC a balloon launch occurred which carried two NaI(Tl) detectors ({{val|600|u=cm2}} total area) to an air pressure altitude of 5.5 mb for a total observation time of 6 hours.<ref name=Figueiredo>{{cite journal |title=Gamma-ray observations of SN 1987A |journal=Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica |first1=N. |last1=Figueiredo |first2=T. |last2=Villela |first3=U. B. |last3=Jayanthi |first4=C. A. |last4=Wuensche |first5=J. A. C. F. |last5=Neri |first6=R. C. |last6=Cesta |display-authors=1 |volume=21 |pages=459–462 |date=November 1990 |bibcode=1990RMxAA..21..459F}}</ref> The ] ] in the ] (LMC) was discovered on February 23, 1987, and its progenitor, ], was a ] with luminosity of 2-5{{e|38}} erg/s.<ref name=Figueiredo/> The 847 keV and 1238 keV gamma-ray lines from <sup>56</sup>Co decay have been detected.<ref name=Figueiredo/> | |||

| ] | |||

| During its ] program in 1977, ] announced plans to build a "great observatory" for gamma-ray astronomy. The ] (CGRO) was designed to take advantage of the major advances in detector technology during the 1980s, and was launched in 1991. The satellite carried four major instruments which have greatly improved the spatial and temporal resolution of gamma-ray observations. The CGRO provided large amounts of data which are being used to improve our understanding of the high-energy processes in our Universe. CGRO was de-orbited in June 2000 as a result of the failure of one of its stabilizing ]s. | |||

| ] was launched in 1996 and deorbited in 2003. It predominantly studied X-rays, but also observed gamma-ray bursts. By identifying the first non-gamma ray counterparts to gamma-ray bursts, it opened the way for their precise position determination and optical observation of their fading remnants in distant galaxies. | |||

| The ] 2 (HETE-2) was launched in October 2000 (on a nominally 2-year mission) and was still operational (but fading) in March 2007. The HETE-2 mission ended in March 2008. | |||

| ==2000s and 2010s== | |||

| {{further|Pulsar|Blazar}} | |||

| {{multiple image |direction=horizontal |align=right |total_width=400 | |||

| |image1=Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope 3 years of observations (energies larger than 1 GeV).jpg |caption1=First survey of the sky at energies above 1 GeV, collected by ] in three years of observation (2009 to 2011). | |||

| |image2=585379main 2-year-all-sky GT1 GeV labels.jpg |caption2=Fermi Second Catalog of Gamma-Ray Sources constructed over two years. All-sky image showing energies greater than 1 GeV. Brighter colors indicate gamma-ray sources.<ref name="gamma-ray-census">{{Cite web |url=https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/GLAST/news/gamma-ray-census.html |title=Fermi's Latest Gamma-ray Census Highlights Cosmic Mysteries |publisher=NASA |date=September 9, 2011 |access-date=May 31, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ], a NASA spacecraft, was launched in 2004 and carries the BAT instrument for gamma-ray burst observations. Following BeppoSAX and HETE-2, it has observed numerous X-ray and optical counterparts to bursts, leading to distance determinations and detailed optical follow-up. These have established that most bursts originate in the explosions of massive stars (]s and ]s) in distant galaxies. As of 2021, Swift remains operational.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://swift.gsfc.nasa.gov/ |title=The Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory |publisher=NASA |date=January 12, 2021 |access-date=January 17, 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Currently the (other) main space-based gamma-ray observatories are ] (International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory), ], and ] (Astro-rivelatore Gamma a Immagini Leggero). | |||

| *] (launched on October 17, 2002) is an ESA mission with additional contributions from the ], Poland, US, and Russia. | |||

| *] is an all-Italian small mission by ], ] and ] collaboration. It was successfully launched by the Indian ] rocket from the ] ] base on April 23, 2007. | |||

| *] was launched by NASA on June 11, 2008. It includes LAT, the Large Area Telescope, and GBM, the Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor, for studying gamma-ray bursts. | |||

| ] | |||

| In November 2010, using the ], two gigantic gamma-ray bubbles, spanning about 25,000 ]s across, were detected at the heart of the ]. These bubbles of ] are suspected as erupting from a massive ] or evidence of a burst of star formations from millions of years ago. They were discovered after scientists filtered out the "fog of background gamma-rays suffusing the sky". This discovery confirmed previous clues that a large unknown "structure" was in the center of the Milky Way.<ref>{{cite journal |title=Giant Gamma-ray Bubbles from Fermi-LAT: Active Galactic Nucleus Activity or Bipolar Galactic Wind? |journal=The Astrophysical Journal |first1=Meng |last1=Su |first2=Tracy R. |last2=Slatyer |first3=Douglas P. |last3=Finkbeiner |volume=724 |issue=2 |pages=1044–1082 |date=December 2010 |doi=10.1088/0004-637X/724/2/1044 |bibcode=2010ApJ...724.1044S |arxiv=1005.5480v3|s2cid=59939190 }} <br /> {{cite web |url=http://www.cfa.harvard.edu/news/2010/pr201022.html |title=Astronomers Find Giant, Previously Unseen Structure in our Galaxy |work=Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics |first1=David A. |last1=Aguilar |first2=Christine |last2=Pulliam |name-list-style=amp |date=November 9, 2010 |access-date=November 14, 2010}} <br /> {{cite news |url=https://www.skyandtelescope.com/astronomy-news/why-is-the-milky-way-blowing-bubbles/ |title=Why is the Milky Way Blowing Bubbles? |work=Sky & Telescope |first=Kelly |last=Beatty |date=November 11, 2010 |access-date=November 14, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| In 2011 the Fermi team released its second catalog of gamma-ray sources detected by the satellite's Large Area Telescope (LAT), which produced an inventory of 1,873 objects shining with the highest-energy form of light. 57% of the sources are ]s. Over half of the sources are ], their central ]s created gamma-ray emissions detected by the LAT. One third of the sources have not been detected in other wavelengths.<ref name="gamma-ray-census" /> | |||

| Ground-based gamma-ray observatories include ], ], ], and ]. Ground-based observatories probe a higher energy range than space-based observatories, since their effective areas can be many orders of magnitude larger than a satellite. | |||

| ==Recent observations== | |||

| In April 2018, the largest catalog yet of high-energy gamma-ray sources in space was published.<ref>{{cite press release |url=https://phys.org/news/2018-04-largest-published-high-energy-gamma-ray.html |title=The largest catalog ever published of very high-energy gamma ray sources in the Galaxy |publisher=] |agency=Phys.org |date=April 9, 2018}}</ref> | |||

| In a 18 May 2021 press release, China's Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO) reported the detection of a dozen ultra-high-energy gamma rays with energies exceeding 1 peta-electron-volt (quadrillion electron-volts or PeV), including one at 1.4 PeV, the highest energy photon ever observed. The authors of the report have named the sources of these PeV gamma rays PeVatrons.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} In 2024, LHAASO announced the detection of a 2.5 PeV gamma ray originating from the Cygnus X region. | |||

| === Gamma-Ray Burst GRB221009A 2022 === | |||

| Astronomers using the Gemini South telescope located in Chile observed flash from a Gamma-Ray Burst identified as ], on 14 October 2022. Gamma-ray bursts are the most energetic flashes of light known to occur in the universe. Scientists of NASA estimated that the burst occurred at a point 2.4 billion light-years from earth. The gamma-ray burst occurred as some giant stars exploded at the ends of their lives before collapsing into black holes, in the direction of the constellation ]. It has been estimated that the burst released up to 18 teraelectronvolts of energy, or even a possible TeV of 251. It seemed that GRB221009A was a long gamma-ray burst, possibly triggered by a supernova explosion.<ref></ref><ref> | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| ===Notes=== | |||

| {{reflist|group=nb}} | |||

| ===Citations=== | |||

| {{Reflist|colwidth=30em}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| {{commons category|Gamma-ray astronomy}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| *, a TeV gamma-ray sources catalog. | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100501050234/http://sourceforge.net/projects/gammalib/ |date=May 1, 2010 }}, a versatile toolbox for high-level analysis of astronomical gamma-ray data. | |||

| *, 1-10TeV gamma-ray astronomy in India. | |||

| {{Astronomy navbox}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Gamma-Ray Astronomy}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 15:50, 8 December 2024

Observational astronomy performed with gamma rays

Gamma-ray astronomy is a subfield of astronomy where scientists observe and study celestial objects and phenomena in outer space which emit cosmic electromagnetic radiation in the form of gamma rays, i.e. photons with the highest energies (above 100 keV) at the very shortest wavelengths. Radiation below 100 keV is classified as X-rays and is the subject of X-ray astronomy.

In most cases, gamma rays from solar flares and Earth's atmosphere fall in the MeV range, but it's now known that solar flares can also produce gamma rays in the GeV range, contrary to previous beliefs. Much of the detected gamma radiation stems from collisions between hydrogen gas and cosmic rays within our galaxy. These gamma rays, originating from diverse mechanisms such as electron-positron annihilation, the inverse Compton effect and in some cases gamma decay, occur in regions of extreme temperature, density, and magnetic fields, reflecting violent astrophysical processes like the decay of neutral pions. They provide insights into extreme events like supernovae, hypernovae, and the behavior of matter in environments such as pulsars and blazars. A huge number of gamma ray emitting high-energy systems like black holes, stellar coronas, neutron stars, white dwarf stars, remnants of supernova, clusters of galaxies, including the Crab Nebula and the Vela pulsar (the most powerful source so far), have been identified, alongside an overall diffuse gamma-ray background along the plane of the Milky Way galaxy. Cosmic radiation with the highest energy triggers electron-photon cascades in the atmosphere, while lower-energy gamma rays are only detectable above it. Gamma-ray bursts, like GRB 190114C, are transient phenomena challenging our understanding of high-energy astrophysical processes, ranging from microseconds to several hundred seconds.

Gamma rays are difficult to detect due to their high energy and their blocking by the Earth’s atmosphere, necessitating balloon-borne detectors and artificial satellites in space. Early experiments in the 1950s and 1960s used balloons to carry instruments to access altitudes where the atmospheric absorption of gamma rays is low, followed by the launch of the first gamma-ray satellites: SAS 2 (1972) and COS-B (1975). These were defense satellites originally designed to detect gamma rays from secret nuclear testing, but they luckily discovered puzzling gamma-ray bursts coming from deep space. In the 1970s, satellite observatories found several gamma-ray sources, among which a very strong source called Geminga was later identified as a pulsar in proximity. The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (launched in 1991) revealed numerous gamma-ray sources in space. Today, both ground-based observatories like the VERITAS array and space-based telescopes like the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope (launched in 2008) contribute significantly to gamma-ray astronomy. This interdisciplinary field involves collaboration among physicists, astrophysicists, and engineers in projects like the High Energy Stereoscopic System (H.E.S.S.), which explores extreme astrophysical environments like the vicinity of black holes in active galactic nuclei.

Studying gamma rays provides valuable insights into extreme astrophysical environments, as observed by the H.E.S.S. Observatory. Ongoing research aims to expand our understanding of gamma-ray sources, such as blazars, and their implications for cosmology. As GeV gamma rays are important in the study of extra-solar, and especially extragalactic, astronomy, new observations may complicate some prior models and findings.

Future developments in gamma-ray astronomy will integrate data from gravitational wave and neutrino observatories (Multi-messenger astronomy), enriching our understanding of cosmic events like neutron star mergers. Technological advancements, including advanced mirror designs, better camera technologies, improved trigger systems, faster readout electronics, high-performance photon detectors like Silicon photomultipliers (SiPMs), alongside innovative data processing algorithms like time-tagging techniques and event reconstruction methods, will enhance spatial and temporal resolution. Machine learning algorithms and big data analytics will facilitate the extraction of meaningful insights from vast datasets, leading to discoveries of new gamma-ray sources, identification of specific gamma-ray signatures, and improved modeling of gamma-ray emission mechanisms. Future missions may include space telescopes and lunar gamma-ray observatories (taking advantage of the Moon's lack of atmosphere and stable environment for prolonged observations), enabling observations in previously inaccessible regions. The ground-based Cherenkov Telescope Array project, a next-generation gamma ray observatory which will incorporate many of these improvements and will be ten times more sensitive, is planned to be fully operational by 2025.

Early history

Long before experiments could detect gamma rays emitted by cosmic sources, scientists had known that the universe should be producing them. Work by Eugene Feenberg and Henry Primakoff in 1948, Sachio Hayakawa and I.B. Hutchinson in 1952, and, especially, Philip Morrison in 1958 had led scientists to believe that a number of different processes which were occurring in the universe would result in gamma-ray emission. These processes included cosmic ray interactions with interstellar gas, supernova explosions, and interactions of energetic electrons with magnetic fields. However, it was not until the 1960s that our ability to actually detect these emissions came to pass.

Most gamma rays coming from space are absorbed by the Earth's atmosphere, so gamma-ray astronomy could not develop until it was possible to get detectors above all or most of the atmosphere using balloons and spacecraft. The first gamma-ray telescope carried into orbit, on the Explorer 11 satellite in 1961, picked up fewer than 100 cosmic gamma-ray photons. They appeared to come from all directions in the Universe, implying some sort of uniform "gamma-ray background". Such a background would be expected from the interaction of cosmic rays (very energetic charged particles in space) with interstellar gas.

The first true astrophysical gamma-ray sources were solar flares, which revealed the strong 2.223 MeV line predicted by Morrison. This line results from the formation of deuterium via the union of a neutron and proton; in a solar flare the neutrons appear as secondaries from interactions of high-energy ions accelerated in the flare process. These first gamma-ray line observations were from OSO 3, OSO 7, and the Solar Maximum Mission, the latter spacecraft launched in 1980. The solar observations inspired theoretical work by Reuven Ramaty and others.

Significant gamma-ray emission from our galaxy was first detected in 1967 by the detector aboard the OSO 3 satellite. It detected 621 events attributable to cosmic gamma rays. However, the field of gamma-ray astronomy took great leaps forward with the SAS-2 (1972) and the Cos-B (1975–1982) satellites. These two satellites provided an exciting view into the high-energy universe (sometimes called the 'violent' universe, because the kinds of events in space that produce gamma rays tend to be high-speed collisions and similar processes). They confirmed the earlier findings of the gamma-ray background, produced the first detailed map of the sky at gamma-ray wavelengths, and detected a number of point sources. However the resolution of the instruments was insufficient to identify most of these point sources with specific visible stars or stellar systems.

A discovery in gamma-ray astronomy came in the late 1960s and early 1970s from a constellation of military defense satellites. Detectors on board the Vela satellite series, designed to detect flashes of gamma rays from nuclear bomb blasts, began to record bursts of gamma rays from deep space rather than the vicinity of the Earth. Later detectors determined that these gamma-ray bursts are seen to last for fractions of a second to minutes, appearing suddenly from unexpected directions, flickering, and then fading after briefly dominating the gamma-ray sky. Studied since the mid-1980s with instruments on board a variety of satellites and space probes, including Soviet Venera spacecraft and the Pioneer Venus Orbiter, the sources of these enigmatic high-energy flashes remain a mystery. They appear to come from far away in the Universe, and currently the most likely theory seems to be that at least some of them come from so-called hypernova explosions—supernovas creating black holes rather than neutron stars.

Nuclear gamma rays were observed from the solar flares of August 4 and 7, 1972, and November 22, 1977. A solar flare is an explosion in a solar atmosphere and was originally detected visually in the Sun. Solar flares create massive amounts of radiation across the full electromagnetic spectrum from the longest wavelength, radio waves, to high energy gamma rays. The correlations of the high energy electrons energized during the flare and the gamma rays are mostly caused by nuclear combinations of high energy protons and other heavier ions. These gamma rays can be observed and allow scientists to determine the major results of the energy released, which is not provided by the emissions from other wavelengths.

See also Magnetar#1979 discovery detection of a soft gamma repeater.

Detector technology

Observation of gamma rays first became possible in the 1960s. Their observation is much more problematic than that of X-rays or of visible light, because gamma-rays are comparatively rare, even a "bright" source needing an observation time of several minutes before it is even detected, and because gamma rays are difficult to focus, resulting in a very low resolution. The most recent generation of gamma-ray telescopes (2000s) have a resolution of the order of 6 arc minutes in the GeV range (seeing the Crab Nebula as a single "pixel"), compared to 0.5 arc seconds seen in the low energy X-ray (1 keV) range by the Chandra X-ray Observatory (1999), and about 1.5 arc minutes in the high energy X-ray (100 keV) range seen by High-Energy Focusing Telescope (2005).

Very energetic gamma rays, with photon energies over ~30 GeV, can also be detected by ground-based experiments. The extremely low photon fluxes at such high energies require detector effective areas that are impractically large for current space-based instruments. Such high-energy photons produce extensive showers of secondary particles in the atmosphere that can be observed on the ground, both directly by radiation counters and optically via the Cherenkov light which the ultra-relativistic shower particles emit. The Imaging Atmospheric Cherenkov Telescope technique currently achieves the highest sensitivity.

Gamma radiation in the TeV range emanating from the Crab Nebula was first detected in 1989 by the Fred Lawrence Whipple Observatory at Mt. Hopkins, in Arizona in the USA. Modern Cherenkov telescope experiments like H.E.S.S., VERITAS, MAGIC, and CANGAROO III can detect the Crab Nebula in a few minutes. The most energetic photons (up to 16 TeV) observed from an extragalactic object originate from the blazar, Markarian 501 (Mrk 501). These measurements were done by the High-Energy-Gamma-Ray Astronomy (HEGRA) air Cherenkov telescopes.

Gamma-ray astronomy observations are still limited by non-gamma-ray backgrounds at lower energies, and, at higher energy, by the number of photons that can be detected. Larger area detectors and better background suppression are essential for progress in the field. A discovery in 2012 may allow focusing gamma-ray telescopes. At photon energies greater than 700 keV, the index of refraction starts to increase again.

1980s to 1990s

On June 19, 1988, from Birigüi (50° 20' W, 21° 20' S) at 10:15 UTC a balloon launch occurred which carried two NaI(Tl) detectors (600 cm total area) to an air pressure altitude of 5.5 mb for a total observation time of 6 hours. The supernova SN1987A in the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC) was discovered on February 23, 1987, and its progenitor, Sanduleak -69 202, was a blue supergiant with luminosity of 2-5×10 erg/s. The 847 keV and 1238 keV gamma-ray lines from Co decay have been detected.

During its High Energy Astronomy Observatory program in 1977, NASA announced plans to build a "great observatory" for gamma-ray astronomy. The Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (CGRO) was designed to take advantage of the major advances in detector technology during the 1980s, and was launched in 1991. The satellite carried four major instruments which have greatly improved the spatial and temporal resolution of gamma-ray observations. The CGRO provided large amounts of data which are being used to improve our understanding of the high-energy processes in our Universe. CGRO was de-orbited in June 2000 as a result of the failure of one of its stabilizing gyroscopes.

BeppoSAX was launched in 1996 and deorbited in 2003. It predominantly studied X-rays, but also observed gamma-ray bursts. By identifying the first non-gamma ray counterparts to gamma-ray bursts, it opened the way for their precise position determination and optical observation of their fading remnants in distant galaxies.

The High Energy Transient Explorer 2 (HETE-2) was launched in October 2000 (on a nominally 2-year mission) and was still operational (but fading) in March 2007. The HETE-2 mission ended in March 2008.

2000s and 2010s

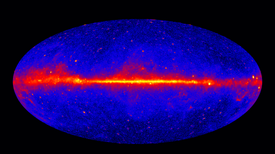

Further information: Pulsar and Blazar First survey of the sky at energies above 1 GeV, collected by Fermi in three years of observation (2009 to 2011).

First survey of the sky at energies above 1 GeV, collected by Fermi in three years of observation (2009 to 2011). Fermi Second Catalog of Gamma-Ray Sources constructed over two years. All-sky image showing energies greater than 1 GeV. Brighter colors indicate gamma-ray sources.

Fermi Second Catalog of Gamma-Ray Sources constructed over two years. All-sky image showing energies greater than 1 GeV. Brighter colors indicate gamma-ray sources.

Swift, a NASA spacecraft, was launched in 2004 and carries the BAT instrument for gamma-ray burst observations. Following BeppoSAX and HETE-2, it has observed numerous X-ray and optical counterparts to bursts, leading to distance determinations and detailed optical follow-up. These have established that most bursts originate in the explosions of massive stars (supernovas and hypernovas) in distant galaxies. As of 2021, Swift remains operational.

Currently the (other) main space-based gamma-ray observatories are INTEGRAL (International Gamma-Ray Astrophysics Laboratory), Fermi, and AGILE (Astro-rivelatore Gamma a Immagini Leggero).

- INTEGRAL (launched on October 17, 2002) is an ESA mission with additional contributions from the Czech Republic, Poland, US, and Russia.

- AGILE is an all-Italian small mission by ASI, INAF and INFN collaboration. It was successfully launched by the Indian PSLV-C8 rocket from the Sriharikota ISRO base on April 23, 2007.

- Fermi was launched by NASA on June 11, 2008. It includes LAT, the Large Area Telescope, and GBM, the Gamma-Ray Burst Monitor, for studying gamma-ray bursts.

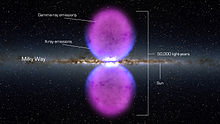

In November 2010, using the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope, two gigantic gamma-ray bubbles, spanning about 25,000 light-years across, were detected at the heart of the Milky Way. These bubbles of high-energy radiation are suspected as erupting from a massive black hole or evidence of a burst of star formations from millions of years ago. They were discovered after scientists filtered out the "fog of background gamma-rays suffusing the sky". This discovery confirmed previous clues that a large unknown "structure" was in the center of the Milky Way.

In 2011 the Fermi team released its second catalog of gamma-ray sources detected by the satellite's Large Area Telescope (LAT), which produced an inventory of 1,873 objects shining with the highest-energy form of light. 57% of the sources are blazars. Over half of the sources are active galaxies, their central black holes created gamma-ray emissions detected by the LAT. One third of the sources have not been detected in other wavelengths.

Ground-based gamma-ray observatories include HAWC, MAGIC, HESS, and VERITAS. Ground-based observatories probe a higher energy range than space-based observatories, since their effective areas can be many orders of magnitude larger than a satellite.

Recent observations

In April 2018, the largest catalog yet of high-energy gamma-ray sources in space was published.

In a 18 May 2021 press release, China's Large High Altitude Air Shower Observatory (LHAASO) reported the detection of a dozen ultra-high-energy gamma rays with energies exceeding 1 peta-electron-volt (quadrillion electron-volts or PeV), including one at 1.4 PeV, the highest energy photon ever observed. The authors of the report have named the sources of these PeV gamma rays PeVatrons. In 2024, LHAASO announced the detection of a 2.5 PeV gamma ray originating from the Cygnus X region.

Gamma-Ray Burst GRB221009A 2022

Astronomers using the Gemini South telescope located in Chile observed flash from a Gamma-Ray Burst identified as GRB221009A, on 14 October 2022. Gamma-ray bursts are the most energetic flashes of light known to occur in the universe. Scientists of NASA estimated that the burst occurred at a point 2.4 billion light-years from earth. The gamma-ray burst occurred as some giant stars exploded at the ends of their lives before collapsing into black holes, in the direction of the constellation Sagitta. It has been estimated that the burst released up to 18 teraelectronvolts of energy, or even a possible TeV of 251. It seemed that GRB221009A was a long gamma-ray burst, possibly triggered by a supernova explosion.

See also

- Cosmic-ray observatory

- Galactic Center GeV excess

- Gamma-ray Burst Coordinates Network

- History of gamma-ray burst research

- Ultra-high-energy cosmic ray

References

Notes

- Astronomical literature generally hyphenates "gamma-ray" when used as an adjective, but uses "gamma ray" without a hyphen for the noun.

Citations

- "EGRET Detection of Gamma Rays from the Moon". Goddard Space Flight Center. August 1, 2005.

- for example, supernova SN 1987A emitted an "afterglow" of gamma-ray photons from the decay of newly made radioactive cobalt-56 ejected into space in a cloud, by the explosion.

"The Electromagnetic Spectrum - Gamma-rays". NASA. Archived from the original on April 30, 2007. Retrieved November 14, 2010. - Grossman, Lisa (August 24, 2018). "Strange gamma rays from the sun may help decipher its magnetic fields". Science News.

- Reddy, Francis (January 30, 2017). "NASA's Fermi Sees Gamma Rays from 'Hidden' Solar Flares". NASA.

- "CTAO — the World's Most Powerful Ground-Based Gamma-Ray Observatory". ESO.org. Retrieved May 23, 2024.

- Morrison, Philip (March 1958). "On gamma-ray astronomy". Il Nuovo Cimento. 7 (6): 858–865. Bibcode:1958NCim....7..858M. doi:10.1007/BF02745590. S2CID 121118803.

- Lutz, Diana (December 7, 2009). "Washington University physicists are closing in on the origin of cosmic rays". Washington University in St. Louis.

- "The History of Gamma-ray Astronomy". NASA. Archived from the original on May 20, 1998. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- "Gamma ray". Science Clarified. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- Ramaty, R.; et al. (July 1979). "Nuclear gamma-rays from energetic particle interactions". Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series. 40: 487–526. Bibcode:1979ApJS...40..487R. doi:10.1086/190596. hdl:2060/19790005667.

- "Overview of Solar Flares". NASA. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- Krieg, Uwe (2008). Siegfried Röser (ed.). Reviews in Modern Astronomy: Cosmic Matter. Vol. 20. Wiley. p. 191. ISBN 978-3-527-40820-7.

- ^ Wogan, Tim (May 9, 2012). "Silicon 'prism' bends gamma rays". PhysicsWorld.com.

- ^ Figueiredo, N.; et al. (November 1990). "Gamma-ray observations of SN 1987A". Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica. 21: 459–462. Bibcode:1990RMxAA..21..459F.

- ^ "Fermi's Latest Gamma-ray Census Highlights Cosmic Mysteries". NASA. September 9, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2015.

- "The Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory". NASA. January 12, 2021. Retrieved January 17, 2021.

- Su, Meng; Slatyer, Tracy R.; Finkbeiner, Douglas P. (December 2010). "Giant Gamma-ray Bubbles from Fermi-LAT: Active Galactic Nucleus Activity or Bipolar Galactic Wind?". The Astrophysical Journal. 724 (2): 1044–1082. arXiv:1005.5480v3. Bibcode:2010ApJ...724.1044S. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/724/2/1044. S2CID 59939190.

Aguilar, David A. & Pulliam, Christine (November 9, 2010). "Astronomers Find Giant, Previously Unseen Structure in our Galaxy". Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. Retrieved November 14, 2010.

Beatty, Kelly (November 11, 2010). "Why is the Milky Way Blowing Bubbles?". Sky & Telescope. Retrieved November 14, 2010. - "The largest catalog ever published of very high-energy gamma ray sources in the Galaxy" (Press release). CNRS. Phys.org. April 9, 2018.

- Record-breaking gamma-ray burst

- Astronomers spotted the most powerful flash of light

External links

- A History of Gamma-Ray Astronomy Including Related Discoveries

- The High-Altitude Water Cherenkov Observatory

- The HEGRA Atmospheric Cherenkov Telescope System

- The HESS Ground Based Gamma-Ray Experiment

- The MAGIC Telescope Project

- The VERITAS Ground Based Gamma-Ray Experiment

- The space-borne INTEGRAL observatory

- NASA's Swift gamma-ray burst mission

- NASA HETE-2 satellite

- TeVCat, a TeV gamma-ray sources catalog.

- GammaLib Archived May 1, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, a versatile toolbox for high-level analysis of astronomical gamma-ray data.

- TACTIC, 1-10TeV gamma-ray astronomy in India.

| Astronomy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Astronomy by |

| ||||||||||

| Optical telescopes | |||||||||||

| Related | |||||||||||