| Revision as of 05:21, 10 September 2008 editGregalton (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,226 edits Rvt banned user again← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:29, 9 January 2025 edit undoJohn of Reading (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers767,450 editsm Typo/quotemark fixes, replaced: a "economy → an "economy, influnce → influence, ’s → 's (6)Tag: AWB | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Devaluation of currency over a period of time}} | |||

| {{otheruses|Inflate}} | |||

| {{about|a rise in general price level|the expansion of the early universe|Inflation (cosmology)|other uses|Inflation (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{for|increases in the money supply or debasement of the currency|monetary inflation}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Use mdy dates|date=September 2017}} | ||

| {{Macroeconomics sidebar}} | |||

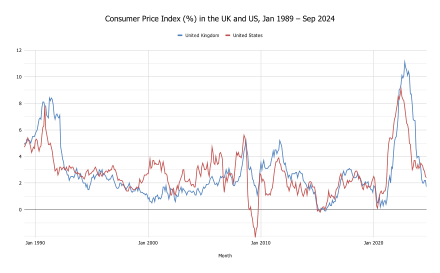

| ] in April 2024]] | |||

| ]}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |date=13 April 2022 |title=CPIH Annual Rate 00: All Items 2015=100 |url=https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/l55o/mm23 |access-date=13 April 2022 |website=] |archive-date=April 24, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220424051728/https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/timeseries/l55o/mm23 |url-status=live }}</ref>]] | |||

| In ], '''inflation''' is a general increase in the prices of goods and services in an ]. This is usually measured using a ] (CPI).<ref>{{citation |title=What Is Inflation? |date=June 8, 2023 |url=https://www.clevelandfed.org/center-for-inflation-research/inflation-101/what-is-inflation-start |access-date=June 8, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210330131140/https://www.clevelandfed.org/our-research/center-for-inflation-research/inflation-101/what-is-inflation-get-started |url-status=dead |publisher=Cleveland Federal Reserve |archive-date=March 30, 2021}}.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bls.gov/bls/inflation.htm|title=Overview of BLS Statistics on Inflation and Prices : U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics|publisher=Bureau of Labor Statistics|date=June 5, 2019|access-date=November 3, 2021|archive-date=December 10, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211210164020/https://www.bls.gov/bls/inflation.htm|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last1=Salwati |first1=Nasiha |last2=Wessel |first2=David |date=June 28, 2021 |title=How does the government measure inflation? |publisher=Brookings Institution |url=https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/06/28/how-does-the-government-measure-inflation/ |url-status=live |access-date=November 3, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211115162420/https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2021/06/28/how-does-the-government-measure-inflation/ |archive-date=November 15, 2021}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/economy_14419.htm|title=The Fed – What is inflation and how does the Federal Reserve evaluate changes in the rate of inflation?|website=Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System|date=September 9, 2016|access-date=November 3, 2021|archive-date=July 17, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210717231718/https://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/economy_14419.htm|url-status=live}}</ref> When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reduction in the ] of money.<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081014031836/http://www.sedlabanki.is/?PageID=195 |date=October 14, 2008}}, Central Bank of Iceland, Accessed on September 11, 2008.</ref><ref>Paul H. Walgenbach, Norman E. Dittrich and Ernest I. Hanson, (1973), Financial Accounting, New York: Harcourt Brace Javonovich, Incorporated. P. 429. "The Measuring Unit principle: The unit of measure in accounting shall be the base money unit of the most relevant currency. This principle also assumes that the unit of measure is stable; that is, changes in its general purchasing power are not considered sufficiently important to require adjustments to the basic financial statements."</ref> The opposite of CPI inflation is ], a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. The common measure of inflation is the '''inflation rate''', the annualized percentage change in a general ].<ref name="Mankiw 2002 22–32">{{Harvnb|Mankiw|2002|pp=22–32}}.</ref> As prices faced by households do not all increase at the same rate, the ] (CPI) is often used for this purpose. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Economics sidebar}} | |||

| '''Inflation''' usually refers to a general rise in the ] of goods and services over a period of time. This is also referred to as '''price inflation'''.<ref>Michael Burda and Charles Wyplosz(1997), ''Macroeconomics: A European text'', 2nd ed., p. 579 (Glossary). ISBN 0-19-877468-0 See also: Olivier Blanchard (2000), ''Macroeconomics'', 2nd ed., Glossary. ISBN 013013306X and Robert Barro (1993), ''Macroeconomics'', 4th ed., Glossary. See also: Andrew Abel and Ben Bernanke (1995), ''Macroeconomics'', 2nd ed., Glossary. ISBN 0201543923.</ref> The term "inflation" originally referred to the debasement of the currency, and was used to describe increases in the money supply (]); however, debates regarding cause and effect have led to its primary use today in describing price inflation. Inflation can also be described as a decline in the real value of money. When the general level of prices rises, each monetary unit buys fewer goods and services. Inflation is measured by calculating the ], which is the percentage rate of change for a price index, such as the ]. | |||

| Changes in inflation are widely attributed to fluctuations in ] ] for goods and services (also known as ]s, including changes in ] or ]), changes in available supplies such as during ] (also known as ]s), or changes in inflation expectations, which may be self-fulfilling.<ref name=Blanchard/> Moderate inflation affects economies in both positive and negative ways. The negative effects would include an increase in the ] of holding money; uncertainty over future inflation, which may discourage investment and savings; and, if inflation were rapid enough, shortages of ] as consumers begin ] out of concern that prices will increase in the future. Positive effects include reducing unemployment due to ],<ref>{{Harvnb|Mankiw|2002|pp=238–255}}.</ref> allowing the central bank greater freedom in carrying out ], encouraging loans and investment instead of money hoarding, and avoiding the inefficiencies associated with deflation. | |||

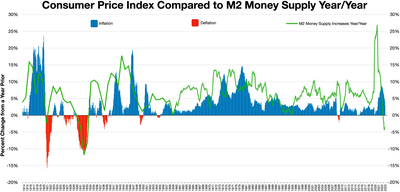

| Economists generally agree that high rates of inflation and ] are caused by high growth rates of the ].<ref>Robert Barro and Vittorio Grilli (1994), ''European Macroeconomics'', Ch. 8, p. 139, Fig. 8.1. Macmillan, ISBN 0333577647.</ref> Views on the factors that determine moderate rates of inflation are more varied: changes in inflation are sometimes attributed to fluctuations in ] ] for goods and services or in available supplies (i.e. changes in ]) and sometimes to changes in the money supply (i.e. the amount of units of currency). However, there is general consensus that in the long run, inflation is caused by money supply increasing faster than the growth rate of the economy. | |||

| Today, some economists favour a low and steady rate of inflation, though inflation is less popular with the general public than with economists, since "inflation simultaneously transfers some of people's income into the hands of government."<ref name="econjournalwatch.org">{{Cite web |last=Hummel |first=Jeffrey Rogers |title=Death and Taxes, Including Inflation: the Public versus Economists |url=https://econjwatch.org/articles/death-and-taxes-including-inflation-the-public-versus-economists |access-date=2023-11-19 |website=econjwatch.org |publisher=Econ Journal Watch: inflation, deadweight loss, deficit, money, national debt, seigniorage, taxation, velocity |page=56}}</ref> Low (as opposed to zero or ]) inflation reduces the probability of economic ] by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly in a downturn and reduces the risk that a ] prevents ] from stabilizing the economy while avoiding the costs associated with high inflation.<ref name="aeaweb.org">{{Cite journal |last=Svensson |first=Lars E. O. |date=December 2003 |title=Escaping from a Liquidity Trap and Deflation: The Foolproof Way and Others |journal=Journal of Economic Perspectives |language=en |volume=17 |issue=4 |pages=145–166 |doi=10.1257/089533003772034934 |s2cid=17420811 |issn=0895-3309|doi-access=free }}</ref> The task of keeping the rate of inflation low and stable is usually given to ]s that control monetary policy, normally through the setting of interest rates and by carrying out ]s.<ref name=Blanchard/> | |||

| Most ]s are tasked with keeping inflation at a low level and there are a number of methods that have been suggested to control it. Inflation can be affected to a significant extent through setting ]s and through other operations (that is, using ]). Some emphasize reducing demand in general, often through ], using increased ] or reduced government spending to reduce demand. Others advocate fighting inflation by fixing the ] between the currency and some reference currency such as gold. Another method attempted in the past has been wage and price controls (]). | |||

| == |

== Terminology == | ||

| The term originates from the Latin ''inflare'' (to blow into or inflate). Conceptually, inflation refers to the general trend of prices, not changes in any specific price. For example, if people choose to buy more cucumbers than tomatoes, cucumbers consequently become more expensive and tomatoes less expensive. These changes are not related to inflation; they reflect a shift in tastes. Inflation is related to the value of currency itself. When currency was linked with gold, if new gold deposits were found, the price of gold and the value of currency would fall, and consequently, prices of all other goods would become higher.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vox.com/cards/inflation-definition-and-explanation/inflation-explanation|title=What is inflation? – Inflation, explained |date=July 25, 2014|work=Vox|access-date=September 13, 2014|archive-date=August 4, 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140804103626/http://www.vox.com/cards/inflation-definition-and-explanation/inflation-explanation|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Inflation originally referred to the debasement of the currency, where gold coins were collected by the government (e.g. the king or the ruler of the region), melted down, mixed with other metals (e.g. silver, copper or lead) and reissued at the same nominal value. By mixing gold with other metals, the government could increase the total number of coins issued using the same amount of gold, and thus gained a profit known as ]. However, this action increased the money supply, and lowered the relative value of money.<ref>Frank Shostak, ""</ref> | |||

| ===Classical economics=== | |||

| In some schools of economics and particularly in the United States in the 19th century (when the term first began to be used frequently), inflation originally was used to refer to increases of the money supply (]), while deflation meant decreasing it.<ref name="Bryan"/> However, classical political economists from Hume to Ricardo did distinguish between and debate the cause and effect: the Bullionists, for example, argued that the Bank of England had over-issued banknotes (over-increased the money supply) and caused 'the depreciation of banknotes' (price inflation).<ref>Mark Blaug, "", pg. 129: "...this was the cause of inflation, or, to use the language of the day, 'the depreciation of banknotes.'"</ref> | |||

| By the nineteenth century, economists categorised three separate factors that cause a rise or fall in the price of goods: a change in the '']'' or production costs of the good, a change in the ''price of money'' which then was usually a fluctuation in the ] price of the metallic content in the currency, and ''currency depreciation'' resulting from an increased supply of currency relative to the quantity of redeemable metal backing the currency. Following the proliferation of private ] currency printed during the ], the term "inflation" started to appear as a direct reference to the ''currency depreciation'' that occurred as the quantity of redeemable banknotes outstripped the quantity of metal available for their redemption. At that time, the term inflation referred to the ] of the currency, and not to a rise in the price of goods.<ref name="Bryan">{{cite journal|first=Michael F.|last=Bryan|url=https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/economic-commentary-archives/1997-economic-commentaries/ec-19971015-on-the-origin-and-evolution-of-the-word-inflation.aspx|publisher=Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary|date=October 15, 1997|title=On the Origin and Evolution of the Word 'Inflation'|journal=Economic Commentary|issue=October 15, 1997|access-date=May 22, 2017|archive-date=October 28, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211028064428/https://www.clevelandfed.org/newsroom-and-events/publications/economic-commentary/economic-commentary-archives/1997-economic-commentaries/ec-19971015-on-the-origin-and-evolution-of-the-word-inflation.aspx|url-status=live}}</ref> This relationship between the over-supply of banknotes and a resulting ] in their value was noted by earlier classical economists such as ] and ], who would go on to examine and debate what effect a currency devaluation has on the price of goods.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Blaug |first=Mark |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4nd6alor2goC&dq=bullionist+inflation&pg=PA128 |title=Economic Theory in Retrospect |date=1997-03-27 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-57701-4 |pages=129 |language=en |quote=...this was the cause of inflation, or, to use the language of the day, 'the depreciation of banknotes.'}}</ref> | |||

| ==Related |

=== Related concepts === | ||

| Other economic concepts related to inflation include: ]{{snd}}a fall in the general price level;<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ashford |first=Kate |date=2023-11-16 |title=What Is Deflation? Why Is It Bad For The Economy? |url=https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/what-is-deflation/#:~:text=Deflation%20Definition,in%20prices%20across%20the%20economy.https://www.forbes.com/advisor/investing/what-is-deflation/#:~:text=Deflation%20Definition,in%20prices%20across%20the%20economy. |access-date=2024-01-30 |work=Forbes Advisor |language=en-US}}</ref> ]{{snd}}a decrease in the rate of inflation;<ref>{{Cite web |title=Disinflation: Definition, How It Works, Triggers, and Example |url=https://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/disinflation.asp |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=Investopedia |language=en}}</ref> ]{{snd}}an out-of-control inflationary spiral;<ref>{{Cite web |title=Hyperinflation |url=https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/economics/hyperinflation/ |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=Corporate Finance Institute |language=en-US}}</ref> ]{{snd}}a combination of inflation, slow economic growth and high unemployment;<ref>{{Cite web |title=What Is Stagflation, What Causes It, and Why Is It Bad? |url=https://www.investopedia.com/terms/s/stagflation.asp |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=Investopedia |language=en}}</ref> ]{{snd}}an attempt to raise the general level of prices to counteract deflationary pressures;<ref>{{Cite web |title=What Is Reflation? |url=https://www.thebalancemoney.com/what-is-reflation-5210962 |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=The Balance |language=en}}</ref> and ]{{snd}}a general rise in the prices of financial assets without a corresponding increase in the prices of goods or services;<ref>{{Cite web |title=Asset-Price Inflation vs. Economic Growth |url=https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/032715/what-difference-between-assetprice-inflation-and-economic-growth.asp |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=Investopedia |language=en}}</ref> ]{{snd}}an advanced increase in the ] and industrial agricultural crops when compared with the general rise in prices.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Agflation: What It Means, How It Works, Impact |url=https://www.investopedia.com/terms/a/agflation.asp |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=Investopedia |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| While "inflation" usually refers to a rise in some broad price index like the ] that indicates the overall level of prices, it is also used to refer to a rise in the prices of some specific set of goods or services, as in "]",<ref>{{cite web|url = http://capmarketline.blogspot.com/2005/11/commodities-inflation.html |title = Capital Markets & Economic Analysis: Commodities Inflation |accessdate = 2008-08-11 |date = Thursday, November 03, 2005}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.econbrowser.com/archives/2006/05/commodity_price.html |title = Econbrowser: Commodity price inflation |accessdate = 2008-08-11}}</ref> "food inflation",<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.nytimes.com/2008/08/08/washington/08ethanol.html?scp=1&sq=food%20inflation&st=cse |title = E.P.A. Declines to Reduce the Quota for Ethanol in Cars - NYTimes.com |accessdate = 2008-08-11 |date = Published: August 7, 2008 |author = MATTHEW L. WALD}}</ref> or "house price inflation"<ref>{{cite web|url = http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/6729323.stm |title = BBC NEWS | Business | House price inflation easing off |accessdate = 2008-08-11 |date = <span class="lu">Last Updated:}}</ref> or ] (a measure of inflation of some sub-set of the broader index, usually excluding goods with higher volatility or strong seasonality). Related economic concepts include: ], a fall in the general price level; ], a decrease in the rate of inflation; ], an out-of-control inflationary spiral; ], a combination of inflation and slow economic growth and rising unemployment; and ], which is an attempt to raise the general level of prices to counteract deflationary pressures. | |||

| More specific forms of inflation refer to sectors whose prices vary semi-independently from the general trend. "House price inflation" applies to changes in the ]<ref>{{Cite web |title=UK House Price Index: November 2021 |url=https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/uk-house-price-index-november-2021 |access-date=2023-11-19 |website=GOV.UK |language=en}}</ref> while "energy inflation" is dominated by the costs of oil and gas.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rubene |first1=Ieva |last2=Koester |first2=Gerrit |date=2021-05-06 |title=Recent dynamics in energy inflation: the role of base effects and taxes|journal=ECB Economic Bulletin |issue=3 |url=https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-bulletin/focus/2021/html/ecb.ebbox202103_04~0a0c8f0814.en.html |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ==Measures of inflation== | |||

| ] | |||

| Inflation is measured by calculating the ], which means the percentage rate of change of a price index, such as the ].<ref>Robert Hall and John Taylor (1986), ''Macroeconomics: Theory, Performance, and Policy'', page 5. ISBN 039395398X.</ref><ref>Blanchard (2000), ''op. cit.''</ref><ref>Barro (1993), ''op. cit.''</ref> | |||

| For example, in January 2007, the U.S. ] was 202.416, and in January 2008 it was 211.080. Therefore, using these numbers, we can calculate that the annual percentage rate of CPI inflation over the course of 2007 was | |||

| :<math>100 \left(\frac{211.080-202.416}{202.416}\right)=4.28%</math> | |||

| That is, the general level of prices for typical U.S. consumers rose by approximately four per cent in 2007.<ref>The numbers reported here refer to the US Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, All Items, series CPIAUCNS, from base level 100 in base year 1982. They were downloaded from the at the ] on August 8, 2008.</ref> | |||

| ==History== | |||

| Price indices include the following. | |||

| ] | |||

| *''']''' (CPI) which measure the price of a selection of goods and services purchased by a "typical consumer." | |||

| *''']''' (COLI) are indices similar to the CPI which are often used to adjust fixed incomes and contractual incomes to maintain the ] of those incomes. | |||

| *''']''' (PPIs) which measures average changes in prices received by domestic producers for their output. This differs from the CPI in that price subsidization, profits, and taxes may cause the amount received by the producer to differ from what the consumer paid. There is also typically a delay between an increase in the PPI and any eventual increase in the CPI. Producer price index measures the pressure being put on producers by the costs of their raw materials. This could be "passed on" to consumers, or it could be absorbed by profits, or offset by increasing productivity. In ] and the ], an earlier version of the PPI was called the ''']'''. | |||

| *''']''', which measure the price of a selection of commodities. In the present commodity price indices are weighted by the relative importance of the components to the "all in" cost of an employee. | |||

| *The ''']''' is a measure of the price of all the goods and services included in ] (GDP). The US Commerce Department publishes a deflator series for US GDP, defined as its nominal GDP measure divided by its real GDP measure. | |||

| *''']''' Because food and oil prices change quickly due to changes in supply and demand conditions in the food and oil markets, it can be difficult to detect the long run trend in price levels when looking at those prices. Therefore most national statistical agencies also report a measure of 'core inflation', which removes the most volatile components (such as food and oil) from a wider price index like the CPI. Since core inflation is less affected by short run supply and demand conditions in specific markets, it helps ]s better measure the inflationary impact of current ]. | |||

| *'''Regional inflation''' The Bureau of Labor Statistics breaks down CPI-U calculations down to different regions of the US. | |||

| *'''Historical inflation''' Before collecting consistent econometric data became standard for governments, and for the purpose of comparing absolute, rather than relative standards of living, various economists have calculated imputed inflation figures. Most inflation data before the early 20th century is imputed based on the known costs of goods, rather than compiled at the time. It is also used to adjust for the differences in real standard of living for the presence of technology. | |||

| *''']''' An undue increase in the prices of real or financial assets, such as ] (equity) and ], can be called 'asset price inflation'. | |||

| While there is no widely-accepted index of this type, some central bankers have suggested that it would be better to aim at stabilizing a wider general price level inflation measure that includes some asset prices, instead of stabilizing CPI or core inflation only. The reason is that by raising interest rates when stock prices or real estate prices rise, and lowering them when these asset prices fall, central banks might be more successful in avoiding ] and crashes in asset prices. | |||

| ===Overview=== | |||

| ===Issues in measuring inflation=== | |||

| Measuring inflation requires finding objective ways of separating out changes in nominal prices from other influences related to real activity. In the simplest possible case, if the price of a 10 oz. can of corn changes from $0.90 to $1.00 over the course of a year, with no change in quality, then this price change represents inflation. This single price change does not, however, demonstrate how overall cost of living changes, and instead of looking at the change in price of one good, the price of a large "basket" of goods and services is measured. This is the purpose of looking at a ], which is a weighted average of many prices. The weights in the ], for example, represent the fraction of spending that typical consumers spend on each type of goods (using data collected by surveying households). | |||

| Inflation has been a feature of history during the entire period when money has been used as a means of payment. One of the earliest documented inflations occurred in ]'s empire 330 ].<ref name=parkin>{{cite journal |last1=Parkin |first1=Michael |title=Inflation |journal=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2008 |pages=1–14 |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_888-2|isbn=978-1-349-95121-5 }}</ref> Historically, when ] was used, periods of inflation and deflation would alternate depending on the condition of the economy. However, when large, prolonged infusions of gold or silver into an economy occurred, this could lead to long periods of inflation. | |||

| Inflation measures are often modified over time, either for the relative weight of goods in the basket, or in the way in which goods from the present are compared with goods from the past. This includes hedonic adjustments and "reweighting" as well as using chained measures of inflation. These adjustments are necessary because the type of goods purchased by 'typical consumers' changes over time, and the quality of some types of goods may change, and new types of goods may be invented. | |||

| The adoption of ] by many countries, from the 18th century onwards, made much larger variations in the supply of money possible.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Fiat Money: What It Is, How It Works, Example, Pros & Cons |url=https://www.investopedia.com/terms/f/fiatmoney.asp |access-date=2024-01-30 |website=Investopedia |language=en}}</ref> Rapid increases in the ] have taken place a number of times in countries experiencing political crises, producing ]s{{snd}}episodes of extreme inflation rates much higher than those observed in earlier periods of ]. The ] of Germany is a notable example. The ] in Venezuela is the highest in the world, with an annual inflation rate of 833,997% as of October 2018.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Corina |first1=Pons |last2=Luc |first2=Cohen |last3=O'Brien |first3=Rosalba |title=Venezuela's annual inflation hit 833,997 percent in October: Congress |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-economy/venezuelas-annual-inflation-hit-833997-percent-in-october-congress-idUSKCN1NC2F9 |access-date=9 November 2018 |work=Reuters |date=7 November 2018 |archive-date=December 12, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211212194638/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-venezuela-economy/venezuelas-annual-inflation-hit-833997-percent-in-october-congress-idUSKCN1NC2F9 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| As with many economic numbers, inflation numbers are often ] in order to differentiate expected cyclical cost increases, versus changes in the economy. Inflation numbers are averaged or otherwise subjected to statistical techniques in order to remove ] and ] of individual prices. Finally, when looking at inflation, economic institutions sometimes only look at subsets or ''special indices''. One common set is inflation excluding food and energy, which is often called "]". | |||

| Historically, inflations of varying magnitudes have occurred, interspersed with corresponding deflationary periods,<ref name=parkin/> from the ] of the 16th century, which was driven by the flood of gold and particularly silver seized and mined by the Spaniards in Latin America, to the largest paper money inflation of all time in Hungary after World War II.<ref name=PeterB>{{cite book |last=Bernholz |first=Peter |url=https://www.elgaronline.com/view/9781784717629.00007.xml |title=Introduction |year=2015 |publisher=Edward Elgar Publishing |isbn=978-1-78471-763-6 |language=en-US |access-date=June 9, 2022 |archive-date=June 18, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210618191304/https://www.elgaronline.com/view/9781784717629.00007.xml |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Effects of inflation== | |||

| An increase in the general level of prices implies a decrease in the real value of money. That is, when the general level of prices rises, each monetary unit buys fewer goods and services.<ref>N. Gregory Mankiw, (2004), ''Principles of Economics'', 3rd edition, International Student Edition. Chapter 30, page 659. ISBN 0324203098.</ref> | |||

| However, since the 1980s, inflation has been held low and stable in countries with independent ]s. This has led to a moderation of the ] and a reduction in variation in most macroeconomic indicators{{snd}}an event known as the ].<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/columnists/article1294376.ece |title=Welcome to 'the Great Moderation' |first=Gerard |last=Baker |work=The Times |date=2007-01-19 |publisher=Times Newspapers |location=London |issn=0140-0460 |access-date=15 April 2011 |archive-date=December 14, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211214175030/https://www.thetimes.co.uk/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| In general, high or unpredictable inflation rates are regarded as bad for following reasons: | |||

| *''Uncertainty'' about future inflation may discourage investment and saving. | |||

| *''Redistribution'' - Inflation redistributes income from those on fixed incomes, such as pensioners, and shifts it to those who draw a variable income, for example from wages and current profits which may keep pace with inflation. The real value of retained profits is destroyed at the rate of inflation as the historical cost balances stay fixed like pensioners´ fixed income. However, debtors may be helped by inflation due to reduction of the real value of debt burden. | |||

| *''Implicit taxation'' - A particular form of inflation as a tax is ''Bracket Creep'' (also called '']''). By allowing inflation to move upwards, certain sticky aspects of the tax code are met by more and more people. For example, income tax brackets, where the next dollar of income is taxed at a higher rate than previous dollars, tend to become distorted. Governments that allow inflation to "bump" people over these thresholds are, in effect, allowing a tax increase because the same real purchasing power is being taxed at a higher rate. | |||

| *''International trade'': Where fixed ]s are imposed, higher inflation than in trading partners' economies will make exports more expensive and tend toward a weakening ]. A sustained higher level of inflation than in the trading partners' economies will also, over the long run, put upward pressure on the implicit exchange rate (what the exchange rate would be if left to be decided in the market) making the fix unsustainable and potentially inviting a an exchange rate crisis. | |||

| *''Cost-push inflation'': Rising inflation can prompt trade unions to demand higher wages, to keep up with consumer prices. Rising wages in turn can help fuel inflation. In the case of collective bargaining, wages will be set as a factor of price expectations, which will be higher when inflation has an upward trend. This can cause a ].{{Fact|date=August 2007}} In a sense, inflation begets further inflationary expectations. | |||

| *''Hoarding'': people buy consumer durables as stores of wealth in the absence of viable alternatives as a means of getting rid of excess cash before it is devalued, creating shortages of the hoarded objects. | |||

| *'']'': if inflation gets totally out of control (in the upward direction), it can grossly interfere with the normal workings of the economy, hurting its ability to supply. | |||

| *'']'': High inflation increases the opportunity cost of holding cash balances and can induce people to hold a greater portion of their assets in interest paying accounts. However, since cash is still needed in order to carry out transactions this means that more "trips to the bank" are necessary in order to make withdrawals, proverbially wearing out the "shoe leather" with each trip. | |||

| *'']'': With high inflation, firms must change their prices often in order to keep up with economy wide changes. But often changing prices is itself a costly activity whether explicitly, as with the need to print new menus, or implicitly. | |||

| *'']'' view: according to this view inflation sets off the business cycle (''see'' ]) and hold this to be the most damaging effect of inflation as artificially low interests rates and the associated increase in the ] lead to reckless, speculative borrowing, resulting in clusters of malinvestments, which eventually have to be liquidated as they become unsustainable.<ref>Thorsten Polleit, "", Mises Institute</ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Some possibly positive effects of (moderate) inflation include: | |||

| | align = right | |||

| *''Labor Market Adjustments'': Keynesians believe that nominal wages are slow to adjust downwards. This can lead to prolonged disequilibrium and high unemployment in the labor market. Since inflation would lower the real wage if nominal wages are kept constant, Keynesian argue that some inflation is good for the economy, as it would allow labor markets to reach equilibrium faster. | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| *''Room to maneuver'': The primary tools for controlling the money supply are the ability to set the discount rate, the rate at which banks can borrow from the central bank, and ] which are the central bank's interventions into the bonds market with the aim of affecting the nominal interest rate. If an economy finds itself in a recession with already low, or even zero, nominal interest rates, then the bank cannot cut these rates further (since negative nominal interest rates are impossible) in order to stimulate the economy - this situation is known as a ]. A moderate level of inflation tends to ensure that nominal interest rates stay sufficiently above zero so that if the need arises the bank can cut the nominal interest rate. | |||

| | width = 350 | |||

| *''Tobin effect'': The ] winning economist ] at one point had argued that a moderate level of inflation can increase investment in an economy leading to faster growth or at least higher steady state level of income. This is due to the fact that inflation lowers the return on monetary assets relative to real assets, such as physical capital. To avoid inflation, investors would switch from holding their assets as money (or a similar, susceptible to inflation, form) to investing in real capital projects. ''See'' ] (Econometrica, V 33, 1965 "Money and Economic Growth"). | |||

| | header = | |||

| | image1 = | |||

| Fineness_of_early_Roman_Imperial_silver_coins.png | |||

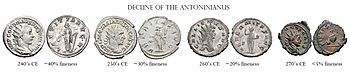

| | caption1 = Silver purity through time in early Roman imperial silver coins. To increase the number of silver coins in circulation while short on silver, the Roman imperial government repeatedly ] the coins. They melted relatively pure silver coins and then struck new silver coins of lower purity but of nominally equal value. Silver coins were relatively pure before Nero (AD 54–68), but by the 270s had hardly any silver left. | |||

| | image2 = Decline_of_the_antoninianus.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = The silver content of Roman silver coins rapidly declined during the ]. | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Ancient Europe=== | |||

| ==Causes of inflation== | |||

| In the long run inflation is generally believed to be a monetary phenomenon while in the short and medium term it is influenced by the relative elasticity of wages, prices and interest rates.<ref>''</ref> The question of whether the short-term effects last long enough to be important is the central topic of debate between monetarist and Keynesian schools. In ] prices and wages adjust quickly enough to make other factors merely marginal behavior on a general trendline. In the ] view, prices and wages adjust at different rates, and these differences have enough effects on real output to be "long term" in the view of people in an economy. | |||

| Alexander the Great's conquest of the ] in 330 BCE was followed by one of the earliest documented inflation periods in the ancient world.<ref name=parkin/> Rapid increases in the quantity of money or in the overall ] have occurred in many different societies throughout history, changing with different forms of money used.<ref>{{Cite news|last=Dobson |first=Roger |title=How Alexander caused a great Babylon inflation |newspaper=] |date=January 27, 2002 |url=https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/how-alexander-caused-a-great-babylon-inflation-671072.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110515070120/http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/how-alexander-caused-a-great-babylon-inflation-671072.html |archive-date=May 15, 2011 |access-date=April 12, 2010 |url-status=dead |df=mdy-all }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | last = Harl | first = Kenneth W. | author-link = Kenneth W. Harl | title = Coinage in the Roman Economy, 300 B.C. to A.D. 700 | place = ] | publisher = ] | year=1996 | isbn = 0-8018-5291-9 }}</ref> For instance, when silver was used as currency, the government could collect silver coins, melt them down, mix them with other, less valuable metals such as copper or lead and reissue them at the same ], a process known as ]. At the ascent of ] as Roman emperor in AD 54, the ] contained more than 90% silver, but by the 270s hardly any silver was left. By diluting the silver with other metals, the government could issue more coins without increasing the amount of silver used to make them. When the cost of each coin is lowered in this way, the government profits from an increase in ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.mint.ca/royalcanadianmintpublic/RcmImageLibrary.aspx?filename=RCM_AR06_E.pdf |title=Annual Report (2006), Royal Canadian Mint, p. 4 |publisher=Mint.ca |access-date=May 21, 2011 |archive-date=December 17, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081217200449/http://www.mint.ca/royalcanadianmintpublic/RcmImageLibrary.aspx?filename=RCM_AR06_E.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> This practice would increase the money supply but at the same time the relative value of each coin would be lowered. As the relative value of the coins becomes lower, consumers would need to give more coins in exchange for the same goods and services as before. These goods and services would experience a price increase as the value of each coin is reduced.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Shostak |first=Frank |date=2008-06-16 |title=Commodity Prices and Inflation: What's the Connection? |url=https://mises.org/library/commodity-prices-and-inflation-whats-connection |access-date=2023-11-19 |website=Mises Institute |language=en}}</ref> Again at the end of the third century CE during the reign of ], the ] experienced rapid inflation.<ref name=parkin/> | |||

| A great deal of economic literature concerns the question of what causes inflation and what effect it has. There are different schools of thought as to what causes inflation. Most can be divided into two broad areas: quality theories of inflation, and quantity theories of inflation. Many theories of inflation combine the two. The quality theory of inflation rests on the expectation of a seller accepting currency to be able to exchange that currency at a later time for goods that are desirable as a buyer. The quantity theory of inflation rests on the equation of the money supply, its velocity, and exchanges. ] and ] proposed a quantity theory of inflation for money, and a quality theory of inflation for production. | |||

| === |

===Ancient China=== | ||

| ] China introduced the practice of printing paper money to create ].<ref name="Glahn">{{cite book |author=von Glahn |first=Richard |title=Fountain of Fortune: Money and Monetary Policy in China, 1000–1700 |publisher=University of California Press |year=1996 |isbn=978-0-520-20408-9 |page=48}}</ref> During the Mongol ], the government spent a great deal of money fighting ], and reacted by printing more money, leading to inflation.<ref name="Ropp2010">{{cite book |author=Ropp |first=Paul S. |title=China in World History |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-19-517073-3 |pages=82}}</ref> Fearing the inflation that plagued the Yuan dynasty, the ] initially rejected the use of paper money, and reverted to using copper coins.<ref name="Bernholz">{{cite book |author=Bernholz |first=Peter |title=Monetary Regimes and Inflation: History, Economic and Political Relationships |publisher=Edward Elgar Publishing |year=2003 |isbn=978-1-84376-155-6 |pages=53–55}}</ref> | |||

| ===Medieval Egypt=== | |||

| ] economic theory proposes that money is transparent to real forces in the economy, and that visible inflation is the result of pressures in the economy expressing themselves in prices. | |||

| During the ] king ]'s ] to ] in 1324, he was reportedly accompanied by a ] that included thousands of people and nearly a hundred camels. When he passed through ], he spent or gave away so much gold that it depressed its price in Egypt for over a decade,<ref>{{Cite web |date=2006-05-24 |title=Mansa Musa |url=http://www.blackhistorypages.net/pages/mansamusa.php |access-date=2023-11-19 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060524015912/http://www.blackhistorypages.net/pages/mansamusa.php |archive-date=May 24, 2006 }}</ref> reducing its purchasing power. A contemporary Arab historian remarked about Mansa Musa's visit: | |||

| {{blockquote|Gold was at a high price in Egypt until they came in that year. The ] did not go below 25 ]s and was generally above, but from that time its value fell and it cheapened in price and has remained cheap till now. The mithqal does not exceed 22 dirhams or less. This has been the state of affairs for about twelve years until this day by reason of the large amount of gold which they brought into Egypt and spent there .|sign=]|source=Kingdom of Mali<ref>{{cite web |title=Kingdom of Mali – Primary Source Documents |url=http://www.bu.edu/africa/outreach/resources/k_o_mali/ |website=African studies Center |publisher=] |access-date=30 January 2012 |archive-date=November 24, 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151124051633/http://www.bu.edu/africa/outreach/resources/k_o_mali/ |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| There are three major types of inflation, as part of what ] calls the "''']'''":<ref>Robert J. Gordon (1988), ''Macroeconomics: Theory and Policy'', 2nd ed., Chap. 22.4, 'Modern theories of inflation'. McGraw-Hill.</ref> | |||

| *''']''': inflation caused by increases in aggregate demand due to increased private and government spending, etc. Demand inflation is constructive to a faster rate of economic growth since the excess demand and favourable market conditions will stimulate investment and expansion. | |||

| *''']''': also called "supply shock inflation," caused by drops in aggregate supply due to increased prices of inputs, for example. Take for instance a sudden decrease in the supply of oil, which would increase oil prices. Producers for whom oil is a part of their costs could then pass this on to consumers in the form of increased prices. | |||

| *''']''': induced by ], often linked to the "]" because it involves workers trying to keep their wages up (gross wages have to increase above the CPI rate to net to CPI after-tax) with prices and then employers passing higher costs on to consumers as higher prices as part of a "vicious circle." Built-in inflation reflects events in the past, and so might be seen as ]. | |||

| === Medieval age and "price revolution" in Western Europe=== | |||

| A major demand-pull theory centers on the supply of money: inflation may be caused by an increase in the quantity of ] in circulation relative to the ability of the economy to supply (its ]). This is most obvious when governments finance spending in a crisis, such as a civil war, by printing money excessively, often leading to ], a condition where prices can double in a month or less. Another cause can be a rapid decline in the ''demand'' for money, as happened in Europe during the ]. | |||

| There is no reliable evidence of inflation in Europe for the thousand years that followed the fall of the Roman Empire, but from the ] onwards reliable data do exist. Mostly, the medieval inflation episodes were modest, and there was a tendency that inflationary periods were followed by deflationary periods.<ref name=parkin/> | |||

| The ] is also thought to play a major role in determining moderate levels of inflation, although there are differences of opinion on how important it is. For example, ] economists believe that the link is very strong; ], by contrast, typically emphasize the role of ] in the economy rather than the money supply in determining inflation. That is, for Keynesians the money supply is only one determinant of aggregate demand. Some economists consider this a 'hocus pocus' approach: They disagree with the notion that central banks control the money supply, arguing that central banks have little control because the money supply adapts to the demand for bank credit issued by commercial banks. This is the '''theory of endogenous money'''. Advocated strongly by post-Keynesians as far back as the 1960s, it has today become a central focus of ] advocates. This position is not universally accepted: banks create money by making loans, but the aggregate volume of these loans diminishes as real interest rates increase. Thus, central banks influence the money supply by making money cheaper or more expensive, and thus increasing or decreasing its production. | |||

| From the second half of the 15th century to the first half of the 17th, Western Europe experienced a major inflationary cycle referred to as the "]",<ref>], ''American Treasure and the Price Revolution in Spain, 1501–1650'' Harvard Economic Studies, p. 43 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: ], 1934).</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/ecipa/archive/UT-ECIPA-MUNRO-99-02.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090306002320/http://www.chass.utoronto.ca/ecipa/archive/UT-ECIPA-MUNRO-99-02.pdf |url-status=dead |title=John Munro: ''The Monetary Origins of the 'Price Revolution':South Germany Silver Mining, Merchant Banking, and Venetian Commerce, 1470–1540'', Toronto 2003|archive-date=March 6, 2009}}</ref> with prices on average rising perhaps sixfold over 150 years. This is often attributed to the influx of gold and silver from the ] into ],<ref>{{cite book |author=Walton |first=Timothy R. |title=The Spanish Treasure Fleets |publisher=Pineapple Press |year=1994 |isbn=1-56164-049-2 |location=Florida, US |page=85 |language=en-us}}</ref> with wider availability of ] in previously ] causing widespread inflation.<ref>{{Cite journal|url=https://ideas.repec.org/p/bsl/wpaper/2007-12.html|title=The Price Revolution in the 16th Century: Empirical Results from a Structural Vectorautoregression Model|first1=Peter|last1=Bernholz|first2=Peter|last2=Kugler|journal=Working Papers|date=August 1, 2007|via=ideas.repec.org|access-date=March 31, 2015|archive-date=April 25, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210425223334/https://ideas.repec.org/p/bsl/wpaper/2007-12.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Tracy, James D. |title=Handbook of European History 1400–1600: Late Middle Ages, Renaissance, and Reformation |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |location=Boston |year= 1994|page=655 |isbn=90-04-09762-7}}</ref> European population rebound from the ] began before the arrival of New World metal, and may have begun a process of inflation that New World silver compounded later in the 16th century.<ref>{{cite book |author=Fischer |first=David Hackett |title=The Great Wave |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1996 |isbn=0-19-512121-X |page=81 |language=en-uk}}</ref> | |||

| A fundamental concept in inflation analysis is the relationship between inflation and ], called the ]. This model suggests that there is a ] between price stability and employment. Therefore, some level of inflation could be considered desirable in order to minimize unemployment. The Phillips curve model described the U.S. experience well in the 1960s but failed to describe the combination of rising inflation and economic stagnation (sometimes referred to as '']'') experienced in the 1970s. | |||

| ===After 1700=== | |||

| Thus, modern macroeconomics describes inflation using a Phillips curve that ''shifts'' (so the trade-off between inflation and unemployment changes) because of such matters as supply shocks and inflation becoming built into the normal workings of the economy. The former refers to such events as the oil shocks of the 1970s, while the latter refers to the ] and ] implying that the economy "normally" suffers from inflation. Thus, the Phillips curve represents only the ] component of the triangle model. | |||

| A pattern of intermittent inflation and deflation periods persisted for centuries until the ] in the 1930s, which was characterized by major deflation. Since the Great Depression, however, there has been a general tendency for prices to rise every year. In the 1970s and early 1980s, annual inflation in most industrialized countries reached two digits (ten percent or more). The double-digit inflation era was of short duration, however, inflation by the mid-1980s returned to more modest levels. Amid this, general trends there have been spectacular high-inflation episodes in individual countries in ], towards the end of the ] in 1948–1949, and later in some Latin American countries, in Israel, and in Zimbabwe. Some of these episodes are considered ] periods, normally designating inflation rates that surpass 50 percent monthly.<ref name=parkin/> | |||

| Another concept of note is the ] (sometimes called the "]"), a level of ], where the economy is at its optimal level of production given institutional and natural constraints. (This level of output corresponds to the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment, ], or the "natural" rate of unemployment or the full-employment unemployment rate.) If GDP exceeds its potential (and unemployment is below the NAIRU), the theory says that inflation will ''accelerate'' as suppliers increase their prices and built-in inflation worsens. If GDP falls below its potential level (and unemployment is above the NAIRU), inflation will ''decelerate'' as suppliers attempt to fill excess capacity, cutting prices and undermining built-in inflation. | |||

| == Measures == | |||

| However, one problem with this theory for policy-making purposes is that the exact level of potential output (and of the NAIRU) is generally unknown and tends to change over time. Inflation also seems to act in an asymmetric way, rising more quickly than it falls. Worse, it can change because of policy: for example, high unemployment under British Prime Minister ] might have led to a rise in the NAIRU (and a fall in potential) because many of the unemployed found themselves as ] (also see ]), unable to find jobs that fit their skills. A rise in structural unemployment implies that a smaller percentage of the labor force can find jobs at the NAIRU, where the economy avoids crossing the threshold into the realm of accelerating inflation. | |||

| {{see also|Consumer price index}} | |||

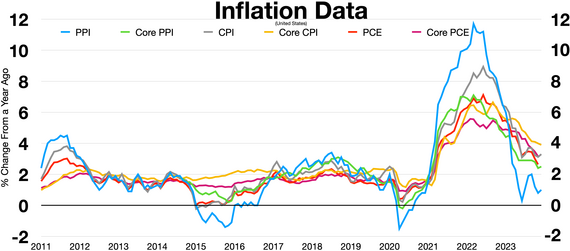

| ] is a ], CPI and PCE ]<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.yahoo.com/now/does-producer-price-index-tell-190327824.html | title=What Does the Producer Price Index Tell You? | date=June 3, 2021 | access-date=October 1, 2022 | archive-date=December 25, 2021 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211225183858/https://www.yahoo.com/now/does-producer-price-index-tell-190327824.html | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| {{legend-line|#00A2FF solid 3px|]}} | |||

| {{legend-line|#61D836 solid 3px|Core PPI}} | |||

| {{legend-line|#929292 solid 3px|]}} | |||

| {{legend-line|#F8BA00 solid 3px|] CPI}} | |||

| {{legend-line|#FF2600 solid 3px|]}} | |||

| {{legend-line|#D41876 solid 3px|Core PCE}}]] | |||

| Given that there are many possible measures of the price level, there are many possible measures of price inflation. Most frequently, the term "inflation" refers to a rise in a broad price index representing the overall price level for goods and services in the economy. The ] (CPI), the ] (PCEPI) and the ] are some examples of broad price indices. However, "inflation" may also be used to describe a rising price level within a narrower set of assets, goods or services within the economy, such as ] (including food, fuel, metals), ]s (such as real estate), services (such as entertainment and health care), or ]. Although the values of capital assets are often casually said to "inflate," this should not be confused with inflation as a defined term; a more accurate description for an increase in the value of a capital asset is appreciation. The FBI (CCI), the ], and ] (ECI) are examples of narrow price indices used to measure price inflation in particular sectors of the economy. ] is a measure of inflation for a subset of consumer prices that excludes food and energy prices, which rise and fall more than other prices in the short term. The ] pays particular attention to the core inflation rate to get a better estimate of long-term future inflation trends overall.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Kiley |first=Michael J. |title=Estimating the common trend rate of inflation for consumer prices and consumer prices excluding food and energy prices |series=Finance and Economic Discussion Series |publisher=Federal Reserve Board |date=July 2008|url=http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2008/200838/200838pap.pdf |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20221009/http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2008/200838/200838pap.pdf |archive-date=2022-10-09 |url-status=live|access-date= May 13, 2015 }}</ref> | |||

| The inflation rate is most widely calculated by determining the movement or change in a price index, typically the ].<ref>''See:'' | |||

| ===Monetarist view=== | |||

| * {{harvnb|Hall|Taylor|1993}}; | |||

| Monetarists assert that the empirical study of monetary history shows that inflation has always been a monetary phenomenon. The ], simply stated, says that the total amount of spending in an economy is primarily determined by the total amount of money in existence. This theory begins with the identity: | |||

| * {{harvnb|Blanchard|2021}}; | |||

| The consumer price index measures movements in prices of a fixed basket of goods and services purchased by a "typical consumer".</ref> | |||

| The inflation rate is the percentage change of a price index over time. The ] is also a measure of inflation that is commonly used in the United Kingdom. It is broader than the CPI and contains a larger basket of goods and services. Inflation is politically driven, and policy can directly influence the trend of inflation. | |||

| :<math>M \cdot V = P \cdot Q</math> | |||

| The RPI is indicative of the experiences of a wide range of household types, particularly low-income households.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Carruthers |first1=A. G. |last2=Sellwood |first2=D. J. |last3=Ward |first3=P. W. |date=1980 |title=Recent Developments in the Retail Prices Index |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2987492 |journal=Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series D (The Statistician) |volume=29 |issue=1 |pages=1–32 |doi=10.2307/2987492 |jstor=2987492 |issn=0039-0526 |access-date=June 9, 2022 |archive-date=June 9, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220609045128/https://www.jstor.org/stable/2987492 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| To illustrate the method of calculation, in January 2007, the U.S. Consumer Price Index was 202.416, and in January 2008 it was 211.080. The formula for calculating the annual percentage rate inflation in the CPI over the course of the year is: <math>\left(\frac{211.080-202.416}{202.416}\right)\times100\%=4.28\%</math> | |||

| The resulting inflation rate for the CPI in this one-year period is 4.28%, meaning the general level of prices for typical U.S. consumers rose by approximately four percent in 2007.<ref>The numbers reported here refer to the US Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, All Items, series CPIAUCNS, from base level 100 in base year 1982. They were downloaded from the FRED database at the ] on August 8, 2008.</ref> | |||

| Other widely used price indices for calculating price inflation include the following: | |||

| * ''']''' (PPIs) which measures average changes in prices received by domestic producers for their output. This differs from the CPI in that price subsidization, profits, and taxes may cause the amount received by the producer to differ from what the consumer paid. There is also typically a delay between an increase in the PPI and any eventual increase in the CPI. Producer price index measures the pressure being put on producers by the costs of their raw materials. This could be "passed on" to consumers, or it could be absorbed by profits, or offset by increasing productivity. In India and the United States, an earlier version of the PPI was called the ]. | |||

| * ''']''', which measure the price of a selection of commodities. In the present commodity price indices are weighted by the relative importance of the components to the "all in" cost of an employee. | |||

| * ''']''': because food and oil prices can change quickly due to changes in ] conditions in the food and oil markets, it can be difficult to detect the long run trend in price levels when those prices are included. Therefore, most ] also report a measure of 'core inflation', which removes the most volatile components (such as food and oil) from a broad price index like the CPI. Because core inflation is less affected by short run supply and demand conditions in specific markets, ]s rely on it to better measure the inflationary effect of current ]. | |||

| Other common measures of inflation are: | |||

| * ''']''' is a measure of the price of all the goods and services included in gross domestic product (GDP). The ] publishes a deflator series for US GDP, defined as its nominal GDP measure divided by its real GDP measure. | |||

| ∴ <math>\mbox{GDP Deflator} = \frac{\mbox{Nominal GDP}}{\mbox{Real GDP}}</math> | |||

| * '''Regional inflation''' The Bureau of Labor Statistics breaks down CPI-U calculations down to different regions of the US. | |||

| * '''Historical inflation''' Before collecting consistent econometric data became standard for governments, and for the purpose of comparing absolute, rather than relative standards of living, various economists have calculated imputed inflation figures. Most inflation data before the early 20th century is imputed based on the known costs of goods, rather than compiled at the time. It is also used to adjust for the differences in real standard of living for the presence of technology. | |||

| * ''']''' is an undue increase in the prices of real assets, such as real estate. | |||

| In some cases, the measures are meant to be more humorous or to reflect a single place. This includes: | |||

| * The ], which calculates the cost of the items mentioned in a song, "].<ref name="Olson">{{Cite news |last=Olson |first=Elizabeth |date=December 20, 2007 |title=The '12 Days' Index Shows a Record Increase |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2003/12/25/business/the-12-days-index-shows-a-record-increase-704075.html?n=Top%2FReference%2FTimes+Topics%2FSubjects%2FG%2FGifts |work=]}}</ref> | |||

| * The ], which compares prices across countries.<ref>{{cite news |date=9 April 1998 |title=Big MacCurrencies |url=http://www.economist.com/node/159859 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171227100228/http://www.economist.com/node/159859 |archive-date=27 December 2017 |access-date=27 November 2013 |newspaper=The Economist}}</ref> | |||

| * The ], which calculates the price of food needed to make a ], a popular African dish.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Erezi |first=Dennis |date=2022-04-28 |title=Jollof Index, Chicken Republic, inflation and changing food consumption patterns |url=https://guardian.ng/features/jollof-index-chicken-republic-inflation-and-changing-food-consumption-patterns/ |access-date=2024-05-15 |website=The Guardian Nigeria News - Nigeria and World News |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| * The ], which calculates the price of food needed to cook one soup and two other dishes for a small family in Hong Kong. | |||

| * The ], which calculates the price of housing in a fashionable neighborhood of ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Eichholtz |first=Piet M. A. |date=1996 |title=A Long Run House Price Index: The Herengracht Index, 1628-1973 |url=http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=598 |journal=SSRN Electronic Journal |language=en |doi=10.2139/ssrn.598 |issn=1556-5068}}</ref> | |||

| * The ], which claimed that when the economy got worse, small luxury sales, such as ], would go up.<ref>{{Cite news |date=23 January 2009 |title=Lip service: What lipstick sales tell you about the economy |url=https://www.economist.com/unknown/2009/01/23/lip-service |access-date=2024-06-10 |newspaper=The Economist |issn=0013-0613}}</ref> | |||

| === Issues in measuring === | |||

| Measuring inflation in an economy requires objective means of differentiating changes in nominal prices on a common set of goods and services, and distinguishing them from those price shifts resulting from changes in value such as volume, quality, or performance. For example, if the price of a can of corn changes from $0.90 to $1.00 over the course of a year, with no change in quality, then this price difference represents inflation. This single price change would not, however, represent general inflation in an overall economy. Overall inflation is measured as the price change of a large "basket" of representative goods and services. This is the purpose of a ], which is the combined price of a "basket" of many goods and services. The combined price is the sum of the weighted prices of items in the "basket". A weighted price is calculated by multiplying the ] of an item by the number of that item the average consumer purchases. Weighted pricing is necessary to measure the effect of individual unit price changes on the economy's overall inflation. The ], for example, uses data collected by surveying households to determine what proportion of the typical consumer's overall spending is spent on specific goods and services, and weights the average prices of those items accordingly. Those weighted average prices are combined to calculate the overall price. To better relate price changes over time, indexes typically choose a "base year" price and assign it a value of 100. Index prices in subsequent years are then expressed in relation to the base year price.<ref name=Taylor>{{cite book |last=Taylor |first=Timothy |title=Principles of Economics |publisher=Freeload Press |date=2008 |isbn=978-1-930789-05-0}}</ref> While comparing inflation measures for various periods one has to take into consideration the ] as well. | |||

| Inflation measures are often modified over time, either for the relative weight of goods in the basket, or in the way in which goods and services from the present are compared with goods and services from the past. Basket weights are updated regularly, usually every year, to adapt to changes in consumer behavior. Sudden changes in consumer behavior can still introduce a weighting bias in inflation measurement. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic it has been shown that the basket of goods and services was no longer representative of consumption during the crisis, as numerous goods and services could no longer be consumed due to government containment measures ("lock-downs").<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Benchimol |first1=Jonathan |last2=Caspi |first2=Itamar |last3=Levin |first3=Yuval |date=2022 |title=The COVID-19 Inflation Weighting in Israel |journal=The Economists' Voice |volume=19 |issue=1 |pages=5–14 |doi=10.1515/ev-2021-0023 |s2cid=245497122 |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last=Seiler|first=Pascal|date=2020-09-16|title=Weighting bias and inflation in the time of COVID-19: evidence from Swiss transaction data|journal=]|volume=156|issue=1|pages=13|doi=10.1186/s41937-020-00057-7|issn=2235-6282|pmc=7493696|pmid=32959014 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| Over time, adjustments are also made to the type of goods and services selected to reflect changes in the sorts of goods and services purchased by 'typical consumers'. New products may be introduced, older products disappear, the quality of existing products may change, and consumer preferences can shift. Different segments of the population may naturally consume different "baskets" of goods and services and may even experience different inflation rates. It is argued that companies have put more innovation into bringing down prices for wealthy families than for poor families.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Botella |first1=Elena |title=That "Inflation Inequality" Report Has a Major Problem |url=https://slate.com/business/2019/11/inflation-inequality-not-about-beer-lettuce.html |access-date=11 November 2019 |work=] |date=8 November 2019 |archive-date=November 30, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211130071656/https://slate.com/business/2019/11/inflation-inequality-not-about-beer-lettuce.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Inflation numbers are often ] to differentiate expected cyclical cost shifts. For example, home heating costs are expected to rise in colder months, and seasonal adjustments are often used when measuring inflation to compensate for cyclical energy or fuel demand spikes. Inflation numbers may be averaged or otherwise subjected to statistical techniques to remove ] and ] of individual prices.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Vavra |first1=Joseph |date=2014 |title=Inflation Dynamics and Time-Varying Volatility: New Evidence and an SS Interpretation |url=https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/129/1/215/1897034 |journal=The Quarterly Journal of Economics |volume=129 |issue=1 |pages=215–258 |doi= 10.1093/qje/qjt027 |access-date=2023-03-22}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Arlt |first=Josef |date=11 March 2021 |title=The problem of annual inflation rate indicator |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/ijfe.2563 |journal=International Journal of Finance & Economics |volume=28 |issue=3 |pages=2772–2788|doi=10.1002/ijfe.2563 |s2cid=233675877 }}</ref> | |||

| When looking at inflation, economic institutions may focus only on certain kinds of prices, or ''special indices'', such as the ] index which is used by central banks to formulate ].<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/coreinflation.asp|title=Why Core Inflation is Important|last=Kenton|first=Will|website=Investopedia|language=en|access-date=2020-01-17|archive-date=December 14, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211214063705/https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/coreinflation.asp|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Most inflation indices are calculated from weighted averages of selected price changes. This necessarily introduces distortion, and can lead to legitimate disputes about what the true inflation rate is. This problem can be overcome by including all available price changes in the calculation, and then choosing the ] value.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.clevelandfed.org/Research/commentary/1991/1201.pdf |title=Median Price Changes: An Alternative Approach to Measuring Current Monetary Inflation |access-date=May 21, 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110515145028/http://www.clevelandfed.org/Research/commentary/1991/1201.pdf |archive-date=May 15, 2011 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> In some other cases, governments may intentionally report false inflation rates; for instance, during the presidency of ] (2007–2015) the ] was criticised for manipulating economic data, such as inflation and GDP figures, for political gain and to reduce payments on its inflation-indexed debt.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-imf-argentina-idUSBRE91019920130202 |title=IMF reprimands Argentina for inaccurate economic data |newspaper=Reuters |date=February 2, 2013 |access-date=February 2, 2013 |last1=Wroughton |first1=Lesley |archive-date=August 4, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210804134926/https://www.reuters.com/article/us-imf-argentina-idUSBRE91019920130202 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-01/argentina-becomes-first-nation-censured-by-imf-on-inflation-data.html |title=Argentina Becomes First Nation Censured by IMF on Economic Data |newspaper=Bloomberg.com |date=February 2, 2013 |access-date=February 2, 2013 |archive-date=March 10, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210310235820/http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-02-01/argentina-becomes-first-nation-censured-by-imf-on-inflation-data.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| === Official vs. true vs. perceived inflation === | |||

| The true inflation is one percentage point lower than the official one, according to research. Therefore, the 2% inflation target is needed to prevent the true inflation being close to zero or even deflation. The reasons are the following:<ref>{{cite web|url=https://cals.ncsu.edu/news/you-decide-why-stop-at-an-inflation-rate-of-2/|title=You Decide: Why Stop at an Inflation Rate Target of 2%?|date=January 29, 2023|website=CALS News|publisher=NC State University}}</ref> | |||

| * '''Substitution effect''': People buy fewer products with the highest price rises and more of those whose prices have risen less. Therefore, the price of their non-fixed shopping basket rises less than that of a fixed shopping basket. | |||

| * '''Unobserved quality improvements''': Even though statisticians try to take quality improvements into account, they are not able to do it fully. This is why people rather buy current products at the higher prices than old products at their old prices. | |||

| * '''New goods''': The current shopping basket is much better, because it has goods that you previously could not even dream of.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.dummies.com/article/business-careers-money/business/economics/inflation-usually-overestimated-228118/|title=Why Inflation Is Usually Overestimated|author=Dan Richards|author2=Manzur Rashid|author3=Peter Antonioni|date=November 1, 2016|publisher=John Wiley & Sons}}</ref> | |||

| Nevertheless, people overestimate the inflation even vs. the measured inflation. This is because they focus more on commonly-bought items than on durable goods, and more on price increases than on price decreases.<ref name=SC>{{cite web|date=January 19, 2022 |publisher=Statistics Canada |title=The naked eye versus the CPI: How does our perception of inflation stack up against the data? |url=https://www.statcan.gc.ca/o1/en/plus/256-naked-eye-versus-cpi-how-does-our-perception-inflation-stack-against-data}}<!-- auto-translated from Finnish by Module:CS1 translator --></ref> | |||

| On the other hand, different people have different shopping baskets and hence face different inflation rates.<ref name=SC/> | |||

| ===Inflation expectations=== | |||

| Inflation expectations or expected inflation is the rate of inflation that is anticipated for some time in the foreseeable future. There are two major approaches to modeling the formation of inflation expectations. ] models them as a weighted average of what was expected one period earlier and the actual rate of inflation that most recently occurred. ] models them as unbiased, in the sense that the expected inflation rate is not systematically above or systematically below the inflation rate that actually occurs. | |||

| A long-standing survey of inflation expectations is the University of Michigan survey.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MICH|title=University of Michigan: Inflation Expectation|date=January 1978|publisher=Economic Research, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis|access-date=March 9, 2017|archive-date=November 7, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211107075130/https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MICH|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Inflation expectations affect the economy in several ways. They are more or less built into ]s, so that a rise (or fall) in the expected inflation rate will typically result in a rise (or fall) in nominal interest rates, giving a smaller effect if any on ]s. In addition, higher expected inflation tends to be built into the rate of wage increases, giving a smaller effect if any on the changes in ]. Moreover, the response of inflationary expectations to monetary policy can influence the division of the effects of policy between inflation and unemployment (see ]). | |||

| == Causes == | |||

| {{Organize section|date=February 2024}} | |||

| === Historical approaches === | |||

| Theories of the origin and causes of inflation have existed since at least the 16th century. Two competing theories, the ] and the ], appeared in various disguises during century-long debates on recommended central bank behaviour. In the 20th century, ], ] and ] (also known as ]) views on inflation dominated post-World War II ] discussions, which were often heated intellectual debates, until some kind of synthesis of the various theories was reached by the end of the century. | |||

| ==== Before 1936 ==== | |||

| {{main|Real bills doctrine}} | |||

| The ] from ca. 1550–1700 caused several thinkers to present what is now considered to be early formulations of the ] (QTM). Other contemporary authors attributed rising price levels to the debasement of national coinages. Later research has shown that also growing output of ]an silver mines and an increase in the ] because of innovations in the payment technology, in particular the increased use of ], contributed to the price revolution.<ref name=Dimand>{{cite book|last1=Dimand |first1=Robert W. |chapter=Monetary Economics, History of |title=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2016 |pages=1–13 |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2721-1 |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_2721-1 |publisher=Palgrave Macmillan UK |isbn=978-1-349-95121-5 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| An alternative theory, the ] (RBD), originated in the 17th and 18th century, receiving its first authoritative exposition in ]'s '']''.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Green |first1=Roy |title=Real Bills Doctrine |journal=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2018 |pages=11328–11330 |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_1614|isbn=978-1-349-95188-8 }}</ref> It asserts that banks should issue their money in exchange for short-term real bills of adequate value. As long as banks only issue a dollar in exchange for assets worth at least a dollar, the issuing bank's assets will naturally move in step with its issuance of money, and the money will hold its value. Should the bank fail to get or maintain assets of adequate value, then the bank's money will lose value, just as any financial security will lose value if its asset backing diminishes. The real bills doctrine (also known as the backing theory) thus asserts that inflation results when money outruns its issuer's assets. The quantity theory of money, in contrast, claims that inflation results when money outruns the economy's production of goods. | |||

| During the 19th century, three different schools debated these questions: The ] upheld a quantity theory view, believing that the ]'s issues of bank notes should vary one-for-one with the bank's gold reserves. In contrast to this, the ] followed the real bills doctrine, recommending that the bank's operations should be governed by the needs of trade: Banks should be able to issue currency against bills of trading, i.e. "real bills" that they buy from merchants. A third group, the Free Banking School, held that competitive private banks would not overissue, even though a monopolist central bank could be believed to do it.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Schwartz |first1=Anna J. |title=Banking School, Currency School, Free Banking School |journal=The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics |date=2018 |pages=694–700 |doi=10.1057/978-1-349-95189-5_263|isbn=978-1-349-95188-8 }}</ref> | |||

| The debate between currency, or quantity theory, and banking schools during the 19th century prefigures current questions about the credibility of money in the present. In the 19th century, the banking schools had greater influence in policy in the United States and Great Britain, while the ] had more influence "on the continent", that is in non-British countries, particularly in the ] and the ]. | |||

| During the Bullionist Controversy during the ], ] argued that the Bank of England had engaged in over-issue of bank notes, leading to commodity price increases. In the late 19th century, supporters of the quantity theory of money led by ] debated with supporters of ]. Later, ] sought to explain price movements as the result of real shocks rather than movements in money supply, resounding statements from the real bills doctrine.<ref name=Dimand/> | |||

| In 2019, monetary historians ] and ] published "Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed: Sources of Monetary Disorder 1922–1938".<ref>{{cite book |last1=Humphrey |first1=Thomas M. |last2=Timberlake |first2=Richard H. |title=Gold, the Real Bills Doctrine, and the Fed : sources of monetary disorder 1922–1938 |date=2019 |publisher=Cato Institute |location=Washington, D.C. |isbn=978-1-948647-13-7 |edition=First}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Keynes and the early Keynesians ==== | |||

| {{further|Keynesian Revolution}} | |||

| {{further|Keynes's theory of wages and prices}} | |||

| John Maynard Keynes in his 1936 main work '']'' emphasized that wages and prices were ] in the short run, but gradually responded to ] shocks. These could arise from many different sources, e.g. autonomous movements in investment or fluctuations in private wealth or interest rates.<ref name=parkin/> Economic policy could also affect demand, ] by affecting interest rates and ] either directly through the level of ] or indirectly by changing ] via tax changes. | |||

| The various sources of variations in aggregate demand will cause cycles in both output and price levels. Initially, a demand change will primarily affect output because of the price stickiness, but eventually prices and wages will adjust to reflect the change in demand. Consequently, movements in real output and prices will be positively, but not strongly, correlated.<ref name=parkin/> | |||