| Revision as of 05:32, 20 September 2008 view sourceBobanni (talk | contribs)3,605 edits Tag removal under discussion - see talk← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:53, 10 January 2025 view source Blindlynx (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users5,227 edits Undid revision 1268482639 by Lute88 (talk) What's wrong with the template?Tag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1932–1933 human-made famine in Soviet Ukraine}} | |||

| <!--This article is in Commonwealth English--> | |||

| {{Redirect|Famine in Ukraine||Famine in Ukraine (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{pp|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox famine | |||

| | famine_name = <!-----Overrides {{PAGENAME}}, do not use without careful consideration)-----> | |||

| | image = GolodomorKharkiv.jpg | |||

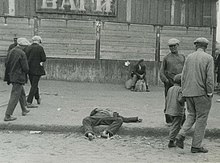

| | caption = Starved peasants on a street in ], 1933, Ukraine's capital at the time | |||

| | country = ] | |||

| | location = ], northern ],{{sfn|Naimark|2010|p=70}} ] | |||

| | coordinates = <!-----(use {{coord}})-----> | |||

| | period = 1932–1933 | |||

| | excess_mortality= <!-----Deaths directly due to famine starvation-----> | |||

| | from_disease = <!-----Indirect famine deaths from subsequent diseases-----> | |||

| | total_deaths = | |||

| * Around 3.5 to 5 million in Ukraine; see ] | |||

| * 62,000 to "hundreds of thousands" in the Kuban{{sfn|Osadchenko|Rudneva|2012}}<ref name="boeckbrian">{{cite journal |last1=Boeck |first1=Brian J. |title=Complicating the National Interpretation of the Famine: Reexamining the Case of Kuban |journal=Harvard Ukraine Studies |date=30 October 2023 |volume=30 |issue=1/4 |page=48 |jstor=23611465}}</ref> | |||

| * Over 300,000 ] dead or migrated{{sfn|Ohayon|2016}} | |||

| | death_rate = <!-----Death rate----> | |||

| | theory = | |||

| | relief = Foreign relief rejected by the state. 176,200 and 325,000 tons of grains provided by the state as food and seed aids between February and July 1933.{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2004|pp=479–484}} | |||

| | food_situation = Deliberate macro-economic food extraction from affected region | |||

| | demographics = | |||

| | causes = * Industrialization policy during the ] | |||

| *Whether it was intentional is debated by scholars | |||

| | memorial = <!-- links to website? --> | |||

| | preceded = | |||

| | succeeded = | |||

| | footnotes = <!-----Test footnote-----> | |||

| |native_name = {{nobold|Голодомор}} | |||

| | consequences = | |||

| * Heavy population loss in Ukraine | |||

| * Kuban Ukrainian population declined from 915,000 to 150,000 between 1926 and 1939 from various causes{{sfn|Ellman|2007}} | |||

| * Over 35% of ] lost in the famine{{sfn|Ohayon|2016}} | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Holodomor''',{{Efn|{{langx|uk|Голодомо́р|Holodomor}}, {{IPA|uk|ɦolodoˈmɔr|IPA}};{{sfn|Jones|2017|page=90}} derived from {{langx|uk|морити голодом|lit=to kill by starvation|translit=moryty holodom|label=none}}); Also literally known as "Extermination by Hunger" or "Hunger-extermination"}} also known as the '''Ukrainian Famine''',<ref>{{Cite web |date=16 April 2019 |title=How Joseph Stalin Starved Millions in the Ukrainian Famine |url=https://www.history.com/news/ukrainian-famine-stalin |access-date=13 February 2024 |website=HISTORY |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Renate |first1=Stark |title=Holodomor, Famine in Ukraine 1932-1933: A Crime against Humanity or Genocide? |url=https://arrow.tudublin.ie/ijass/vol10/iss1/2/ |publisher=Irish Journal of Applied Social Studies: Vol. 10: Iss. 1, Article 2 |access-date=September 14, 2024 |doi=10.21427/D7PQ8P}}</ref>{{Efn|{{langx|uk|великий український голод|translit=velykyi ukrainskyi holod}}}} was a human-made ] in ] from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of ]. The Holodomor was part of the wider ] which affected the major ] areas of the ]. | |||

| {{POV-check|date=July 2008}} | |||

| {{Cleanup|date=March 2008}} | |||

| While scholars are in consensus that the ] was man-made, it remains in dispute whether the Holodomor was directed at Ukrainians and whether it constitutes a ], the point of contention being the absence of attested documents explicitly ordering the starvation of any area in the Soviet Union. Some historians conclude that the famine was deliberately engineered by ] to eliminate a ] movement. Others suggest that the famine was primarily the consequence of rapid ] and ] of agriculture. A middle position is that the initial causes of the famine were an unintentional byproduct of the process of collectivization but once it set in, starvation was selectively weaponized and the famine was "instrumentalized" and amplified against Ukrainians as a means to punish Ukrainians for resisting Soviet policies and to suppress their ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Holodomor}} | |||

| The '''Holodomor''' ({{lang-uk|Голодомор}}) is the famine that took place in ] during the ]-] agricultural season when the devastating famines also took place in several ]. The Holodomor ravaged the rural population of the Ukrainian SSR, and is considered one of the greatest national catastrophes to affect the Ukrainian nation in the modern history.<ref name="Losses"/><ref name="Vallin2"/><ref name="britannica"> - Encyclopædia Britannica: "The Great Famine (Holodomor) of 1932–33—a man-made demographic catastrophe unprecedented in peacetime. Of the estimated six to eight million people who died in the Soviet Union, about four to five million were Ukrainians."</ref><ref>Helen Fawkes, , '']'', ], ]</ref> Estimates for the total number of casualties within Soviet Ukraine range between 2.2 million (]' estimate)<ref> France Meslé, Gilles Pison, Jacques Vallin , ''Population and societies'', N°413, juin 2005</ref> <ref> ce Meslé, Jacques Vallin Mortalité et causes de décès en Ukraine au XXè siècle + CDRom ISBN 2-7332-0152-2 CD online data (partially - http://www.ined.fr/fichier/t_publication/cdrom_mortukraine/cdrom.htm </ref> and 3-3.5 million (historians' estimate),<ref name=Naslidky4>], Hennadiy Yefimenko. (Demographic consequence of Holodomor of 1933 in Ukraine. The all-Union census of 1937 in Ukraine), Kiev, Institute of History, 2003. pp. 42-63</ref><ref name="HowMany" /><ref name=Tragediya>С. Уиткрофт (], (On demographic evidence of the tragedy of the Soviet village in 1931-1833), "Трагедия советской деревни: Коллективизация и раскулачивание 1927-1939 гг.: Документы и материалы. Том 3. Конец 1930-1933 гг.", Российская политическая энциклопедия, 2001, ISBN 5-8243-0225-1, с. 885, Приложение № 2</ref> though much higher figures are often quoted by the media and cited in political debates.<ref name=finn>Peter Finn, , '']'', April 27, 2008, "There are no exact figures on how many died. Modern historians place the number between 2.5 million and 3.5 million. Yushchenko and others have said at least 10 million were killed." </ref> | |||

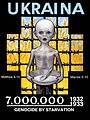

| Ukraine was one of the largest grain-producing states in the USSR and was subject to unreasonably high grain quotas compared to the rest of the USSR in 1930.<ref name="Kulchytskystalinslave" /> {{efn|name=Marples 2009.}} This caused Ukraine to be hit particularly hard by the famine. Early estimates of the death toll by scholars and government officials vary greatly. A joint statement to the ] signed by 25 countries in 2003 declared that 7 to 10 million died.{{efn|name= UN signatory nations, 2003}} However, current scholarship estimates a range significantly lower with 3.5 to 5 million victims.<ref>{{harvnb|Gorbunova|Klymchuk|2020}}; {{harvnb|Kravchenko|2020}}; {{harvnb|Marples|2007|p=1}}; {{harvnb|Mendel|2018}}; {{harvnb|Yefimenko|2021}}</ref> The famine's widespread impact on Ukraine persists to this day.{{how|date=August 2024}} | |||

| The reasons of the famine are the subject of intense scholarly and political debate. Some historians claim the famine was purposely engineered by the Soviet authorities as an attack on ], while others view it as an unintended consequence of the economic problems associated with radical economic changes implemented during the period of ].<ref name=Kremlin>, ''The News in Brief'', ], 19 June 1998, Vol 7 No 22</ref> It is sometimes argued that natural causes may have been the primary reason for the disaster. | |||

| Public discussion of the famine was banned in the Soviet Union until the '']'' period initiated by ] in the 1980s.{{sfn|Serbyn|2005|pp=1055-1061}} Since 2006, the Holodomor has ] by ], 33 other UN member states, and the ] as a genocide against the Ukrainian people carried out by the Soviet government. In 2008, the Russian ] condemned the Soviet regime "that has neglected the lives of people for the achievement of economic and political goals".{{sfn|National Museum of the Holodomor|2019}} | |||

| There is no international consensus among scholars or politicians on whether the Soviet policies that caused the famine fall under the ].<ref name=finn/><ref name="Bilin99">{{cite journal | author=Yaroslav Bilinsky| title= Was the Ukrainian Famine of 1932–1933 Genocide?| journal= Journal of Genocide Research | year= 1999| volume= 1| issue= 2| pages= 147–156 | url=http://www.faminegenocide.com/resources/bilinsky.html | doi=10.1080/14623529908413948 }}</ref><ref name=marples2005>, , ''ExpressNews'' (]), originally published in '']'', November 30, 2005</ref><ref name="KulchFeb2007">], "", '']'', ], ]. {{ru icon}}</ref><ref name=zn2006>],"Holodomor-33: Why and how?", '']'', ]—]. Available online and .</ref> However, as of ] ], the ] and the governments of several other countries have recognized the actions causing Holodomor as an act of ].<ref name=countriesmar2008>Sources differ on interpreting various statements from different branches of different governments as to whether they amount to the official recognition of the Famine as Genocide by the country. For example, after the statement issued by the ] on March 13, 2008, the total number of countries is given as 19 (according to ''Ukrainian ]'': ), 16 (according to '']'', Russian edition: ), "more than 10" (according to ''Korrespondent'', Ukrainian edition: )</ref> | |||

| <!--Do NOT add citations to the lead, except for material likely to be challenged, per ] (]. Move unneeded citations to the body.--> | |||

| ==Etymology== | == Etymology == | ||

| ''Holodomor'' literally translated from ] means "death by hunger", "killing by hunger, killing by starvation",{{sfn|Werth|2012|p=}}{{sfn|Werth|2007|p=132}}{{sfn|Graziosi|2005|p=464, 457}} or sometimes "murder by hunger or starvation."{{sfn|Fawkes|2006}} It is a ] of the Ukrainian {{langx|uk|holod|lit=]|label=none|italic=yes}}, and {{langx|uk|mor|lit=]|label=none|italic=yes}}. The expression {{langx|uk|holodom moryty |lit=|label=none|italic=yes}} means "to inflict death by hunger." The Ukrainian verb {{langx|uk|moryty|lit=|label=none|italic=yes}} ({{langx|uk|морити|lit=|label=none|italic=}}) means "to poison, to drive to exhaustion, or to torment." The ] form of {{langx|uk|moryty|lit=|label=none|italic=yes}} is {{langx|uk|zamoryty|lit=kill or drive to death|label=none|italic=yes}}.{{sfn|SumInUa Dictionary|2010}} In English, the Holodomor has also been referred to as the ''artificial famine'', ''terror-genocide'' and the ''great famine''.{{sfn|Serbyn|2005|pp=1055-1061}}{{sfn|Davies|2006|p=}}{{sfn|Boriak|von Hagen|2009}} | |||

| It was used in print in the 1930s in Ukrainian diaspora publications in ] as ''Haladamor'',{{sfn|Applebaum|2017|p=363}} and by Ukrainian immigrant organisations in the United States and Canada by 1978;{{sfn|Hryshko|1983}}{{sfn|Dolot|1985}}{{sfn|Hadzewycz|Zarycky|Kolomayets|1983}} in the ], of which Ukraine was a ], any references to the famine were dismissed as ], even after ] in 1956, until the declassification and publication of historical documents in the late 1980s made continued denial of the catastrophe unsustainable.{{sfn|Serbyn|2005|pp=1055-1061}} | |||

| The origins of the word Holodomor come from the ] words ''holod'', ‘hunger’, and ''mor'', ‘]’,<ref name="etymology">Ukrainian ''holod'' (голод, ‘hunger’, compare Russian ''golod'') should not be confused with ''kholod'' (холод, ‘cold’). For details, see ]. ''Mor'' means ‘plague’ in the sense of a disastrous evil or affliction, or a sudden unwelcome outbreak. See ].</ref> possibly from the expression ''moryty holodom'', ‘to inflict death by hunger’. The Ukrainian verb "moryty" (морити) means "to poison somebody, drive to exhaustion or to torment somebody". The perfect form of the verb "moryty" is "zamoryty"{{mdash}}"kill or drive to death by hunger, exhausting work". The neologism “Holodomor” is given in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language as "artificial hunger, organised in vast scale by the criminal regime against the country's population"<ref>, in "Velykyi tlumachnyi slovnyk suchasnoi ukrainsʹkoi movy: 170 000 sliv", chief ed. V. T. Busel, ], Perun (2004), ISBN 9665690132</ref> Sometimes the expression is translated into English as "murder by hunger."<ref>Helen Fawkes , , '']'', 24 November 2006</ref> | |||

| Discussion of the Holodomor became possible as part of the Soviet '']'' ("openness") policy in the 1980s. In Ukraine, the first official use of ''famine'' was in a December 1987 speech by ]i, ], on the occasion of the republic's 70th anniversary.{{sfn|Graziosi|2004}} Another early public usage in the Soviet Union was in a February 1988 speech by Oleksiy Musiyenko, Deputy Secretary for ideological matters of the party organisation of the Kyiv branch of the ] in Ukraine.{{sfn|Musiienko|1988}}{{sfn|US Commission Report vol.1|p=67}} | |||

| ==Scope and duration== | |||

| Historians working with declassified Ukrainian SSR documents have concluded that mass starvation in the Ukrainian SSR lasted from the beginning of January 1933 until mid-June or the beginning of July 1933.<ref name=naslidky/><ref name="HowMany"/> The famine affected all 7 oblasts of the Ukrainian SSR as well as the Moldavian ASSR, a part of Ukraine at the time. However, not every '']'' (district) suffered from famine for the whole 6 month period; starvation peaked in spring 1933. The first reports of mass malnutrition and deaths from starvation emerged from 2 rayons and urban area of Uman - by the time ] and ] ]s – now ] and ], dated by beginning of January 1933. By mid-January 1933 there were reports about mass “difficulties” with food in urban areas that had been undersupplied through the rationing system and deaths from starvation among people who were withdrawn from rationing supply according to Central Committee of the CP(b) of Ukraine Decree December 1932. By the beginning of February 1933, according to received reports from local authorities and Ukrainian GPU, the most affected area was listed as ] which also suffered from epidemics of typhus and malaria. ] and Kiev oblasts were 2nd and 3rd respectively. By mid-March most reports originated from Kiev Oblast. | |||

| By mid-April 1933 the ] reached the top of the most affected list, while Kiev, Dnipropetrovsk, Odessa, Vinnytsya, Donetsk oblasts and Moldavian SSR followed it. Last reports about mass deaths from starvation dated mid-May through the beginning of June 1933 originated from Kiev and Kharkiv oblasts rayons. The “less affected” list noted the ] and northern parts of Kiev and Vinnytsya oblasts . According to the Central Committee of the CP(b) of Ukraine Decree as of February 8 1933 all hunger cases should not have been remain untreated, all local authorities directly obliged to submit reports about number of suffered from hunger, reasons of hunger, number of deaths from hunger and about food aid provided from local sources and centrally provided food aid required. Alternative reporting and food assistance were managed per GPU of Ukrainian SSR. Many regional reports and most of central summary reports are available at central and regional Ukrainian archives at present time. <ref>Голод 1932-1933 років на Україні: очима істориків, мовою документів. </ref> | |||

| The term ''holodomor'' may have first appeared in print in the Soviet Union on 18 July 1988, when Musiyenko's article on the topic was published.{{sfn|Mace|2008|p=132}} ''Holodomor'' is now an entry in the modern, two-volume dictionary of the Ukrainian language, published in 2004, described as "artificial hunger, organised on a vast scale by a criminal ] against a country's population."{{sfn|Busel 2001}} | |||

| ==Causes and outcomes== | |||

| ] in 1932-1933 (7 ]s and ]) administrative borders given in light gray.]]] | |||

| While a complex task, it is possible to group some of the causes that contributed to the Holodomor. They have to be understood in the larger context of the social revolution 'from above' that took place in the ] at the time.<ref name=Problemy12>С. Кульчицький, Проблема колективізації сільського господарства в сталінській “революції зверху”, () ''Проблеми Історіїї України факти, судження, пошуки'', | |||

| №12, 2004, сс. 21-69</ref> | |||

| According to Elazar Barkan, Elizabeth A. Cole, and Kai Struve, the Holodomor has been described as a "Ukrainian Holocaust". They assert that since the 1990s the term ''Holodomor'' has been widely adopted by ] in order to draw parallels to ]. However this term has been criticized by some academics, as the Holocaust was a heavily documented, coordinated effort by ] and its collaborators to eliminate certain ethnic groups such as Jews.{{citation needed|date=June 2024}} By contrast, there is no definitive documentation that Stalin directly ordered the mass murder of Ukrainians.{{sfn|Getty|2018}}{{sfn|Engerman|2009|p=}} Barkan et al. state that the term ''Holodomor'' was "introduced and popularized by the Ukrainian diaspora in North America before Ukraine became independent" and that the term 'Holocaust' in reference to the famine "is not explained at all."{{sfn|Barkan|Cole|Struve|2007}} | |||

| ===Policy of collectivization=== | |||

| {{Further|], ], ]}} | |||

| Approaches to changing from individual farming to a collective type of agricultural production had existed since 1917, but for various reasons (lack of ], agronomy resources, etc.) were not implemented widely until 1925, when there was a more intensive effort by the agricultural sector to increase the number of agricultural cooperatives and bolster the effectiveness of already existing ]es. In late 1927, after the XV Congress of the ], then known as the All-Union Communist party (]) or VKP(b), a significant impetus was given to the ] effort. | |||

| == History == | |||

| In 1927, a ] shortened the ] in southern areas of the Ukrainian SSR and ]. In 1927–28 the winter tillage area was badly affected due to low snow levels. Despite seed aid from the State, many affected areas were not re-sown. The 1928 harvest was affected by drought in most of the grain producing areas of the Ukrainian SSR. Shortages in the harvest and difficulties with the supply system invoked difficulties with the food supply in urban areas and destabilized the food supply situation in the USSR in general. In order to alleviate the situation, a system of food ] was implemented in the second quarter of 1928 initially in ], and later spread to ], ], ], Dniprelstan (]), and ]. At the beginning of 1929 a similar system was implemented throughout the USSR. Despite the aid from the Soviet Ukrainian and the Central governments, many southern rural areas registered occurrences of malnutrition and in some cases hunger and starvation (the affected areas and thus the amount of required food aid was under-accounted by authorities). Due to the shortage of forage ], its numbers were also affected . | |||

| === Scope and duration === | |||

| Most of ]es and recently refurnished ]es went through these years with few losses, and some were even able to provide assistance to peasants in the more affected areas (seed and grain for food). | |||

| The famine affected the Ukrainian SSR as well as the ] (a part of the ] at the time) in spring 1932,{{sfn|Pyrih, 1990; No. 1-132.}} and from February to July 1933,{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2004|p=204}} with the most victims recorded in spring 1933. The consequences are evident in demographic statistics: between 1926 and 1939, the ] increased by only 6.6%, whereas Russia and Belarus grew by 16.9% and 11.7% respectively.{{sfn|USSR Census|1939}}{{sfn|Demoscope Weekly| 2012}} The number of ] decreased by 10%.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-02-29 |title=Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей. |url=https://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/ussr_nac_26.php |access-date=2024-08-15 |archive-date=29 February 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240229113741/https://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/ussr_nac_26.php |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-05-20 |title=Демоскоп Weekly - Приложение. Справочник статистических показателей. |url=https://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/sng_nac_39.php |access-date=2024-08-15 |archive-date=20 May 2024 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20240520171244/https://www.demoscope.ru/weekly/ssp/sng_nac_39.php |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref> | |||

| From the 1932 harvest, Soviet authorities were able to procure only 4.3 million tons of grain, as compared with 7.2 million tons obtained from the 1931 harvest.{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2004|pp=470, 476}} Rations in towns were drastically cut back, and in winter 1932–1933 and spring 1933, people in many urban areas starved.{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2004|p=xviii}} Urban workers were supplied by a ] system and therefore could occasionally assist their starving relatives in the countryside, but rations were gradually cut. By spring 1933, urban residents also faced starvation. It is estimated 70% to 80% of all famine deaths during the Holodomor in eight analyzed Oblasts in the Soviet Union occurred in the first seven months of 1933.{{sfn|Wolowyna|2021}} | |||

| Despite the intense state campaign, the collectivization, which was initially voluntary, was not popular amongst peasants: as of early 1929, only 5.6% of Ukrainian peasant households and 3.8% of ] was “collectivized”. In the early of 1929, the methods employed by the specially empowered authority “UkrKolhozcenter” changed from a voluntary enrollment to an administrative one. By ]st, ], a plan for the creation of kolkhozes was “outperformed” by 239%. As a result, 8.8% of arable land was “collectivized”. | |||

| The first reports of mass ] and deaths from starvation emerged from two urban areas of the city of ], reported in January 1933 by ] and ] ]s. By mid-January 1933, there were reports about mass "difficulties" with food in urban areas, which had been undersupplied through the rationing system, and deaths from starvation among people who were refused rations, according to the December 1932 decree of the Central Committee of the Ukrainian Communist Party. By the beginning of February 1933, according to reports from local authorities and Ukrainian ] (secret police), the most affected area was ], which also suffered from epidemics of ] and ]. ] and Kyiv oblasts were second and third respectively. By mid-March, most of the reports of starvation originated from Kyiv Oblast.{{citation needed|date=July 2018}} | |||

| The next major step toward "all-over collectivization" took place after an article was published by ] in ], in early November 1929. | |||

| By mid-April 1933, ] reached the top of the most affected list, while Kyiv, Dnipropetrovsk, Odesa, Vinnytsia, and ] oblasts, and Moldavian SSR were next on the list. Reports about mass deaths from starvation, dated mid-May through the beginning of June 1933, originated from ]s in Kyiv and Kharkiv oblasts. The "less affected" list noted ] and northern parts of Kyiv and Vinnytsia oblasts. The Central Committee of the CP(b) of Ukraine Decree of 8 February 1933 said no hunger cases should have remained untreated.{{sfn|Pyrih, 1990; No. 343-403.}} '']'', which was tracking the situation in 1933, reported the difficulties in communications and the appalling situation in Ukraine.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Reisenauer |first1=Troy Philip |title=The Great Famine in Soviet Ukraine: Toward New Avenues of Inquiry into the Holodomor |url=https://library.ndsu.edu/ir/bitstream/handle/10365/27445/The%20Great%20Famine%20in%20Soviet%20Ukraine%20Toward%20New%20Avenues%20of%20Inquiry%20into%20the%20Holodomor.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y |page=26-28 |publisher=North Dakota State University |access-date=October 9, 2024 |date=2014}}</ref> | |||

| While “summoned “ by ]–], ] meeting of VKP(b) Central Committee “]s" only trained at special short courses, the main driving force of collectivization and '']'' in Ukraine became a "poor peasants committee" (“komnezamy”) and local village councils (''silrady'') where komnezams members had a voting majority.</small> | |||

| Local authorities had to submit reports about the numbers suffering from hunger, the reasons for hunger, number of deaths from hunger, food aid provided from local sources, and centrally provided food aid required. The GPU managed parallel reporting and food assistance in the Ukrainian SSR. Many regional reports and most of the central summary reports are available from present-day central and regional Ukrainian archives.{{sfn|Pyrih, 1990; No. 343-403.}} | |||

| The USSR Kolhozcenter issued the ], ], decree on collectivisation of livestock within a 3-month period (draft animals 100%, cattle 100%, pigs 80%, sheep and goats 60%). This drove many peasants to slaughter their livestock. By ], ], the percentage of collectivized households almost doubled, to 16.4% of the total number of households. | |||

| === Causes === | |||

| Despite the infamous ], ] ], in which the deadline for the complete collectivization of the Ukrainian SSR was set for the period from the end of 1931 to the spring of 1932, the authorities decided to accelerate the completion of the campaign by autumn of 1930. The high expectations of the plan were outperformed by local authorities even without the assistance of the 7500 “]s – and by March 70.9% of arable land and 62.8% of peasant households were suddenly collectivized. The “]” plan was also “over-performed”. First stage of delukakization lasted from second half of January till beginning of March 1930. Such measures were applied to 309 out of 581 total districts of Ukrainian SSR were accounted 2524 thousands peasants households (out of 5054 thousands total). As of 10 of March 1930 61897 of peasants households were “dekulakized” – or 2.5% of total. While at 1929 percentage of “kulak –households” registered as 1.4%. <ref> http://www.history.org.ua/zbirnyk/9/9.pdf p.230-231</ref>Some of the peasants and "weak elements" were arrested and deported “to the north”. Many arrested ']s' and "well-to-do" farmers resettled their families to the ] and ].<ref>Wheatcroft and Davies </ref> The term 'kulak' was ultimately applied to anybody resisting collectivization as many of the so-called 'kulaks' were no more well-off than other peasants. | |||

| {| class="wikitable floatright" style="margin:1em auto 1em 2em; text-align:right;" | |||

| |+ Soviet grain collections and exports<br />''(in thousand tons)''{{sfn|Davies|Tauger|Wheatcroft|1995|p=645}} | |||

| !Year ending | |||

| !Collections | |||

| !Exports | |||

| |- | |||

| !June 1930 | |||

| |16081 | |||

| |1343 | |||

| |- | |||

| !June 1931 | |||

| |22139 | |||

| |5832 | |||

| |- | |||

| !June 1932 | |||

| |22839 | |||

| |4786 | |||

| |- | |||

| !June 1933 | |||

| |18513 | |||

| |1607 | |||

| |} | |||

| {{main|Causes of the Holodomor}} | |||

| While scholars are in consensus that the ] was man-made,<ref>{{harvnb|Andriewsky|2015|p=37}}: "Historians of Ukraine are no longer debating whether the Famine was the result of natural causes (and even then not exclusively by them). The academic debate appears to come down to the issue of intentions, to whether the special measures undertaken in Ukraine in the winter of 1932–33 that intensified starvation were aimed at Ukrainians as such."</ref><ref>{{cite journal|journal=American Political Science Review|doi=10.1017/S0003055419000066|page=571 |title=Mass Repression and Political Loyalty: Evidence from Stalin's 'Terror by Hunger' |date=2019 |last1=Rozenas |first1=Arturas |last2=Zhukov |first2=Yuri M. |volume=113 |issue=2 |s2cid=143428346 |quote=Similar to famines in Ireland in 1846–1851 (Ó Gráda 2007) and China in 1959–1961 (Meng, Qian and Yared 2015), the politics behind Holodomor have been a focus of historiographic debate. The most common interpretation is that Holodomor was 'terror by hunger' (Conquest 1987, 224), 'state aggression' (Applebaum 2017) and 'clearly premeditated mass murder' (Snyder 2010, 42). Others view it as an unintended by-product of Stalin's economic policies (Kotkin 2017; Naumenko 2017), precipitated by natural factors like adverse weather and crop infestation (Davies and Wheatcroft 1996; Tauger 2001).}}</ref> it remains in dispute whether the Holodomor was directed at Ukrainians and whether it constitutes a ], the point of contention being the absence of attested documents explicitly ordering the starvation of any area in the Soviet Union.{{Sfnm|1a1=Ellman|1y=2005|1p=824|2a1=Davies|2a2=Wheatcroft|2y=2006|2pp=628, 631}} Some historians conclude that the famine was deliberately engineered by ] to eliminate a ] movement.{{efn|name=Britannica "Holodomor"}} Others suggest that the famine was primarily the consequence of rapid ] and ] of agriculture. A middle position, held for example by historian Andrea Graziosi, is that the initial causes of the famine were an unintentional byproduct of the process of collectivization but once it set in, starvation was selectively weaponized and the famine was "instrumentalized" and amplified against Ukrainians as a means to punish Ukrainians for resisting Soviet policies and to suppress their ].{{sfn|Werth|2008}} | |||

| The fast-track to collectivization incited numerous peasant revolts in Ukraine and in other parts of the USSR. In response to the situation "Pravda" published the Stalin's article "Dizzy with successes". Soon, numerous orders and decrees were issued banning the use of force and administrative methods. Some of those “mistakenly” dekulakized, received their property back, and some returned home. As a result the collectivization process was rolled back and by ] 1933 38.2% of Ukrainian SSR peasant households and 41.1% of arable land had been collectivized. By the end of August these numbers declined to 29.2% and 35.6% respectively. | |||

| Some scholars suggest that the famine was a consequence of human-made and natural factors.{{sfn|Graziosi|2004}} The most prevalent man-made factor was changes made to agriculture because of rapid ] during the ].{{sfn|Kulchytsky2007- Evidential Gaps}}{{sfn|Fawkes|2006}}{{sfn| Marples|2005}} There are also those who blame a systematic set of policies perpetrated by the Soviet government under ] designed to exterminate the Ukrainians.{{efn|name=Britannica "Holodomor"}}{{sfn|Ellman|2005}}{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2002|p=77|loc= "he drought of 1931 was particularly severe, and drought conditions continued in 1932. This certainly helped to worsen the conditions for obtaining the harvest in 1932"}}{{sfn|Engerman|2009|p=}} | |||

| A second "forced-voluntary" collectivization campaign was initiated in the winter–summer of 1931 with significant assistance of the so-called "tug-brigades" composed from kolkhoz ]s. Many "kulaks" along with families were deported from the Ukrainian SSR. | |||

| ==== Low harvest ==== | |||

| According to declassified data, around 300,000 peasants in Ukrainian SSR were affected by these policies in 1930–31. Ukrainians composed 15% of the total 1.8 million 'kulaks' relocated Soviet-wide.<ref name="DW490">Davies and Wheatcroft, p.490</ref> Since summer 1931 all further deportations were recommended to be administered only to individuals.” <ref > Ivnitskyy "Tragedy of Soviet Village"</ref> | |||

| According to historian ], the grain yield for the Soviet Union preceding the famine was a low harvest of between 55 and 60 million tons,{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2004|pp=xix–xxi}} likely in part caused by damp weather and low traction power,{{sfn|Wheatcroft|2018}} yet official statistics mistakenly reported a yield of 68.9 million tons.{{sfn| Marples|2002}} (Note that a single ton of grain is enough to feed three people for one year.){{sfn|Davies|Tauger|Wheatcroft|1995|p=643}} Historian Mark Tauger has suggested that drought and damp weather were causes of the low harvest.{{sfn|Tauger|2001|p=45}} Mark Tauger suggested that heavy rains would help the harvest while Stephen Wheatcroft suggested it would hurt it which Natalya Naumenko notes as a disagreement in scholarship.{{sfn|Naumenko|2021}} Another factor which reduced the harvest suggested by Tauger included endemic plant rust.{{sfn|Tauger|2001|p=39}} However, in regard to plant disease Stephen Wheatcroft notes that the Soviet extension of sown area combined with lack of crop rotation may have exacerbated the problem,{{efn|name=Davies 2004, p. 437}} which Tauger also acknowledges in regard to the latter.<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> | |||

| ==== Collectivization, procurements, and the export of grain ==== | |||

| This second "forced-voluntary" collectivization campaign also invoked a delay in sowing. During winter and spring of 1930–31, the Ukrainian agricultural authority "Narkomzem" issued several reports about the significant decline of livestock caused by poor treatment, absence of ], stables/farms and due to "] sabotage". | |||

| {{see also|Collectivization in the Soviet Union|Five-year plans of the Soviet Union#First plan, 1928–1932|Causes of the Holodomor#Consequence of collectivization}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Due to factional struggles with ] wing of the party, peasant resistance to the ] under ], and the need for industrialization, ] declared a need to extract a "tribute" or "tax" from the peasantry.<ref name="collectivizationstruggle">{{cite book |last1=Viola |first1=Lynne |title=The Collectivization of Agriculture in Communist Eastern Europe:Comparison and Entanglements |date=2014 |publisher=] |isbn=978-963-386-048-9 |chapter=Collectivization in the Soviet Union: Specificities and Modalities |pages=49–69}}</ref> This idea was supported by most of the party in the 1920s.<ref name="collectivizationstruggle" /> The tribute collected by the party took on the form of a virtual war against the peasantry that would lead to its ] and the relegating of the countryside to essentially a ] homogenized to the urban culture of the Soviet elite.<ref name="collectivizationstruggle" /> ], however, opposed the policy of forced collectivisation under Stalin and would have favoured a ], gradual approach towards ]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Beilharz |first1=Peter |title=Trotsky, Trotskyism and the Transition to Socialism |date=19 November 2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-70651-2 |pages=1–206 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Lfe-DwAAQBAJ&dq=trotsky+widely+acknowledged+collectivisation&pg=PT196 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Rubenstein |first1=Joshua |title=Leon Trotsky : a revolutionary's life |date=2011 |location=New Haven |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-300-13724-8 |page=161 |url=https://archive.org/details/leontrotskyrevol0000rube/page/160/mode/2up?q=forced+collectivization}}</ref> with greater tolerance for the rights of Soviet Ukrainians.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Deutscher |first1=Isaac |author1-link=Isaac Deutscher |title=The Prophet: The Life of Leon Trotsky |date=5 January 2015 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-78168-721-5 |page=637 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YGznDwAAQBAJ&q=isaac+deutscher+trotsky |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |first=Leon |last=Trotsky |author-link=Leon Trotsky |title=Problem of the Ukraine |date=April 1939 |url=https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1939/04/ukraine.html |via=]}}</ref> This campaign of "colonizing" the peasantry had its roots both in old ] and modern ] of the ] yet with key differences to the latter such as Soviet repression reflecting more the weakness of said state rather than its strength.<ref name="collectivizationstruggle" /> | |||

| According to the ], Ukrainian agriculture was to switch from an exclusive orientation of grain to a more diverse output. This included not only a rise in ] crops, but also other types of agricultural production were expected to be utilised by industry (with even cotton plants being established in 1931). This plan anticipated a decrease in grain acreage, in contrast to an increase of yield, area and of acreage for other crops. | |||

| In this vein by the summer of 1930, the government instituted a program of food requisitioning, ostensibly to increase grain exports. According to Natalya Naumenko, ] and lack of favored industries were primary contributors to famine mortality (52% of excess deaths), and some evidence shows there was discrimination against ethnic Ukrainians and Germans. In Ukraine ] was enforced, entailing extreme crisis and contributing to the famine. In 1929–1930, peasants were induced to transfer land and livestock to state-owned farms, on which they would work as day-labourers for payment in kind.{{sfn|Reid|2017}} | |||

| By ], ], 65.7% of Ukrainian SSR peasant households and 67.2% of arable land were reported as "collectivized", however the main grain and sugar beet production areas were collectivized to a greater extent — 80-90%. <ref></ref> | |||

| Food exports continued during the famine, albeit at a reduced rate.{{sfn|Applebaum|2017|pp=189–220; 221ff}} In regard to exports, ] states that the 1932–1933 grain exports amounted to 1.8 million tonnes, which would have been enough to feed 5 million people for one year.{{sfn|Ellman|2007}} The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is somewhat called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses were ] and ], which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country.{{sfn|Selden|1982}}{{sfn|Chamberlin|1933}} Historian ] lists four problems Soviet authorities ignored during collectivization that would hinder the advancement of agricultural technology and ultimately contributed to the famine:{{sfn|Davies|Wheatcroft|2004|pp=436–441}} | |||

| Decree of Central Committee of VKP(b) from August 2 1931 clarified the “all-over collectivization” term - in order to be considered complete the “all-over collectivization” does not have to reach “100%”, but not less then 68-70% of peasants households and not less then 75-80% of arable lands. According to the same decree “all-over collectivization” accomplished at Northern Caucasus (Kuban) - 88% of households and 92% of arable lands “collectivized”, Ukraine (South) – 85 and 94 percents respectively, Ukraine (Right Bank) – 69 and 80 percents respectively, and Moldavian ASRR (part of Ukrainian SRR) – 68 and 75 percent. <ref >Compendium of Soviet Law for 1931. Moscow, 1932</ref> | |||

| * "Over-extension of the sown area" — Crops yields were reduced and likely some plant disease caused by the planting of future harvests across a wider area of land without rejuvenating soil leading to the reduction of fallow land. | |||

| As of the beginning of October 1931, the collectivization of 68.0% of peasant households, and 72.0% of arable land was complete.<ref name="UHJ2004-2">С.В. Кульчицький, Опір селянства суцільній колективізації, '']'', 2004, № 2, 31-50.</ref> | |||

| * "Decline in draught power" — the over extraction of grain lead to the loss of food for farm animals, which in turn reduced the effectiveness of agricultural operations. | |||

| <br clear="all" /> | |||

| * "Quality of cultivation" — the planting and extracting of the harvest, along with ploughing was done in a poor manner due to inexperienced and demoralized workers and the aforementioned lack of draught power. | |||

| {|class="wikitable" align=right style="margin: 1em auto 1.5em 2.5em" | |||

| * "The poor weather" — drought and other poor weather conditions were largely ignored by Soviet authorities who gambled on good weather and believed agricultural difficulties would be overcome. | |||

| |+ <!------>Collectivization in Ukrainian SSR as of October 1, 1932 | |||

| Mark Tauger notes that Soviet and Western specialist at the time noted draught power shortages and lack of crop rotation contributed to intense weed infestations,<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> with these both being also factors Stephen Wheatcroft lists as contributing to the famine. Natalya Naumenko calculated that reduced agriculture production in "collectivized" collective farms is responsible for up to 52% of Holodomor ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Misplaced Pages Library |url=https://wikipedialibrary.wmflabs.org/ |access-date=2024-07-17 |website=wikipedialibrary.wmflabs.org |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ! ] (in late 1932 <br>administrative borders)|| Number<br>of kolhozes||% of peasantry<br>households collectivization | |||

| |- | |||

| | Kiev Oblast || 4053||67.3 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Chernihiv Oblast|| 2332||47.3 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Vinnytsia Oblast || 3347||58.9 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Kharkiv Oblast|| 4347||72.0 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Dnipropetrovsk Oblast || 3399||85.1 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Odessa Oblast || 3594||84.4 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Donetsk Oblast || 1578||84.4 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Moldavian ASSR || 620||68.3 | |||

| |- | |||

| | Ukrainian SSR || 23270||69.0 (77.1% of arable land) | |||

| |} | |||

| ]]es and peasants - 5,831.3 thousand tons + ]es 475,034 tons]] | |||

| The plan for the state grain collection in the Ukrainian SSR adopted for 1931 was over-optimistic — 510 million ]s (8.4 ]). Drought, administrative distribution of the plan for kolkhozes, together with the lack of relevant management generally destabilized the situation. Significant amounts of grain remained unharvested. A significant percentage was lost during processing and transportation, or spoiled at elevators (wet grain). The total Winter sowing area shrunk by approximately 2 million hectares. Livestock in kolkhozes remained without forage, which was collected under grain procurement. A similar occurrence happened with respect to seeds and wages awarded in kind for kolhoz members. Nevertheless, grain collection continued till May 1932 but reached only 90% of expected plan figures. By the end of December 1931, the collection plan was accomplished by 79%. Many kolkhozes from December 1931 onwards suffered from lack of food, resulting in an increased number of deaths caused by malnutrition registered by OGPU in some areas (Moldavian SSR as a whole and several central rayons of Vinnytsya, Kiev and North-East rayons of Odessa oblasts ) in winter-spring and the early summer months of 1932. By 1932 the sowing campaign of the Ukrainian SSR was obtained with minimal drought power as most of the remaining horses were incapable of working, while the number of available agricultural tractors was too small to fill the gap. | |||

| ====Discrimination and persecution of Ukrainians ==== | |||

| The Government of the Ukrainian SSR tried to remedy the situation but had little success. Administrative and territorial reform (oblast creation) in February 1932, also added to the mismanagement. As a result Moscow had more details about the seed situation than the Ukrainian authorities. In May, 1932, in a desperate effort to change the situation, the central Soviet Government provided 7.1 million ]s of grain for food for Ukraine and dispatched adsitional 700 agricultural tractors intended for other regions of USSR. | |||

| {{see also|Causes of the Holodomor#Soviet state policies that contributed to the Holodomor|Russification of Ukraine#Mid-1920s to early 1930s}} | |||

| {{quote box | |||

| | width = 30em | |||

| | author = — ], ] journalist | |||

| | quote = At every station there was a crowd of peasants in rags, offering icons and linen in exchange for a loaf of bread. The women were lifting up their infants to the compartment windows—infants pitiful and terrifying with limbs like sticks, puffed bellies, big cadaverous heads lolling on thin necks. | |||

| }} | |||

| It has been proposed that the Soviet leadership used the human-made famine to attack ], and thus it could fall under the legal definition of genocide.{{sfn|Margolis|2003}}{{sfn|Kulchytsky2007- Evidential Gaps}}{{sfn|Finn|2008}}{{sfn| Marples|2005}}{{sfn|Bilinsky|1999}}{{sfn|Kulchytsky|2006}} For example, special and particularly lethal policies were adopted in and largely limited to Soviet Ukraine at the end of 1932 and 1933. According to ], "each of them may seem like an ] administrative measure, and each of them was certainly presented as such at the time, and yet each had to kill."{{efn|name=note-anodyne}}{{sfn|Snyder|2010|pp=42–46}} Other sources discuss the famine in relation to a project of imperialism or colonialism of Ukraine by the Soviet state.<ref name="colon1">{{cite journal |last1=Irvin-Erickson |first1=Douglas |title=Raphaël Lemkin, Genocide, Colonialism, Famine, and Ukraine |journal=Empire, Colonialism, and Famine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries |date=12 May 2021 |volume=8 |pages=193–215 |doi=10.21226/ewjus645 |s2cid=235586856 |url=https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ewjus/1900-v1-n1-ewjus06029/1077127ar/abstract/ |access-date=23 October 2023 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="colon2">{{cite journal |last1=Hechter |first1=Michael |title=Internal Colonialism, Alien Rule, and Famine in Ireland and Ukraine |journal=Empire, Colonialism, and Famine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries |date=12 May 2021 |volume=8 |pages=145–157 |doi=10.21226/ewjus642 |s2cid=235579661 |url=https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ewjus/1900-v1-n1-ewjus06029/1077124ar/abstract/ |access-date=23 October 2023 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref name="colon3">{{cite journal |last1=Hrynevych |first1=Liudmyla |title=Stalin's Faminogenic Policies in Ukraine: The Imperial Discourse |journal=Empire, Colonialism, and Famine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries |date=12 May 2021 |volume=8 |pages=99–143 |doi=10.21226/ewjus641 |s2cid=235570495 |url=https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ewjus/1900-v1-n1-ewjus06029/1077123ar/abstract/ |access-date=23 October 2023 |doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Klid |first1=Bohdan |title=Empire-Building, Imperial Policies, and Famine in Occupied Territories and Colonies |journal=Empire, Colonialism, and Famine in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries |date=12 May 2021 |volume=8 |pages=11–32 |doi=10.21226/ewjus634 |s2cid=235578437 |url=https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/ewjus/1900-v1-n1-ewjus06029/1077119ar/abstract/ |access-date=23 October 2023 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ] with the areas of most disastrous famine shaded black]] | |||

| By July, the total amount of aid provided from Central Soviet Authorities for food, sowing and forage for “agricultural sector” was numbered more than 17 million poods. | |||

| According to a ] paper published in 2021 by Andrei Markevich, Natalya Naumenko, and Nancy Qian, regions with higher Ukrainian population shares were struck harder with centrally planned policies corresponding to famine such as increased procurement rate,{{sfn|Qian|2021}} and Ukrainian populated areas were given lower numbers of tractors which the paper argues demonstrates that ethnic discrimination across the board was centrally planned, ultimately concluding that 92% of famine deaths in Ukraine alone along with 77% of famine deaths in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus combined can be explained by systematic bias against Ukrainians.{{sfn|Markevich |Naumenko |Qian|2021}} | |||

| Mark Tauger criticized Natalya Naumenko's work as being based on: "major historical inaccuracies and falsehoods, omissions of essential evidence contained in her sources or easily available, and substantial misunderstandings of certain key topics".<ref name="TaugerQianCritique">{{cite journal |last1=Tauger |first1=Mark B. |title=The Environmental Economy of the Soviet Famine in Ukraine in 1933: A Critique of Several Papers by Natalya Naumenko |journal=Econ Journal Watch |url=https://econjwatch.org/File+download/1286/TaugerSept2023.pdf?mimetype=pdf |access-date=16 October 2023 |archive-date=18 October 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231018075413/https://econjwatch.org/File+download/1286/TaugerSept2023.pdf?mimetype=pdf |url-status=live}}</ref> For example, Naumenko ignored Tauger's findings of 8.94 million tons of the harvest that had been lost to crop "rust and smut",<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> four reductions in grain procurement to Ukraine including a 39.5 million puds reduction in grain procurements ordered by Stalin,<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> and that from Tauger's findings which are contrary to Naumenko's paper's claims the "per-capita grain procurements in Ukraine were less, often significantly less, than the per-capita procurements from the five other main grain-producing regions in the USSR in 1932".<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> | |||

| Speculative prices of food in cooperative network (5-10 times more as compared with neighboring Soviet republics) brought significant peasant “travel for bread”, while attempts to handle situation with speculation had very limited success. Such provision (quota on carried-on foods) was lifted by Stalin (at ]'s request) at the end of May 1932. The July GPU reports for the first half of 1932, mentioned the “difficulties with food” in 127 rayons (out of 484) and acknowledged the incompleteness of the information for the regions. The Decree of Sovnarkom on “Kolkhoz Trade” issued in May, fostered rumors amongst peasants that collectivization was rolled-back again as it had been in spring 1930. The number of peasants who abandoned kolkhozes significantly increased. | |||

| Other scholars argue that in other years preceding the famine this was not the case. For example, Stanislav Kulchytsky claims Ukraine produced more grain in 1930 than the ], ] and ] and ] regions all together, which had never been done before, and on average gave 4.7 quintals of grain from every sown hectare to the state{{emdash}}a record-breaking index of marketability{{emdash}}but was unable to fulfill the grain quota for 1930 until May 1931. Ukraine produced a similar amount of grain in 1931; however, by the late spring of 1932 "many districts were left with no reserves of produce or fodder at all".<ref name="Kulchytskystalinslave" /> Despite this, according to statistics gathered by Nataliia Levchuk, Ukraine and North Caucasus Krai delivered almost 100% of their grain procurement in 1931 versus 67% in two Russian Oblasts during the same period versus 1932 where three Russian regions delivered almost all of their procurements and Ukraine and North Caucasus did not.{{sfn|Wolowyna|2021}} This can partially be explained by Ukrainian regions losing a third of their harvests and Russian regions losing by comparison only 15% of their harvest.{{sfn|Wolowyna|2021}} | |||

| As a result, the government plans for the central grain collection in Ukraine was lowered by 18.1%, in comparison to the 1931 plan. Still, collective farms were expected to return return 132,750 tons of grain which had been provided in spring 1932 as aid. The grain collection plan for July 1932 was adopted to collect 19.5 million ]s. The actual state of collection was disastrous, and by ] only 3 million poods (compared to 21 million in 1931) were collected. As of ] the harvested area was half of that in 1931. The sovhozes had only sowed 16% of the defined area. | |||

| Ultimately, Tauger states: "if the regime had not taken even that smaller amount grain from Ukrainian villages, the famine could have been greatly reduced or even eliminated" however (in his words) "if the regime had left that grain in Ukraine, then other parts of the USSR would have been even more deprived of food than they were, including Ukrainian cities and industrial sites, and the overall effect would still have been a major famine, even worse in "non-Ukrainian" regions."<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> In fact in contrast to Naumenko's paper's claims the higher Ukrainian collectivization rates in Tauger's opinion actually indicate a pro-Ukrainian bias in Soviet policies rather than an anti-Ukrainian one: " did not see collectivization as "discrimination" against Ukrainians; they saw it as a reflection of—in the leaders' view—Ukraine's relatively more advanced farming skills that made Ukraine better prepared for collectivization (Davies 1980a, 166, 187–188; Tauger 2006a)."<ref name="TaugerQianCritique" /> | |||

| Since July 1932 Ukrainian SSR met with difficulty in supplying the planned amount of food to rationing system was implemented in early 1928 to supply extensively growing urban areas with food. This system became the almost sole source of food delivery to cities while the alternatives, cooperative trade and black market trading, became too expensive, and under-supplied, to provide long-range assistance. By December 1932, due the fault of grain procurement daily rationing for rural population limited to 100-600 grams of bread, some group of rural citizens completely withdrawn from rationing supply. | |||

| Naumenko responded to some of Tauger's criticisms in another paper.<ref name="naumenkoresponse">{{cite journal |last1=Naumenko |first1=Natalya |title=Response to Professor Tauger's Comments |journal=Econ Journal Watch |date=September 2023 |page=313}}</ref> Naumenko criticizes Tauger's view of the efficacy of collective farms arguing Tauger's view goes against the consensus,<ref name="naumenkoresponse" /> she also states that the tenfold difference in death toll between the 1932-1933 Soviet famine and the ] can only be explained by government policies,<ref name="naumenkoresponse" /> and that the infestations of pests and plant disease suggested by Tauger as a cause of the famine must also correspond such infestations to rates of collectivization due to deaths by area corresponding to this<ref name="naumenkoresponse" /> due Naumenko's findings that: "on average, if you compare two regions with similar pre-famine characteristics, one with zero collectivization rate and another with a 100 percent collectivization rate, the more collectivized region's 1933 mortality rate increases by 58 per thousand relative to its 1927–1928 mortality rate".<ref name="naumenkoresponse" /> Naumenko believes the disagreement between her and Tauger is due to a "gulf in training and methods between quantitative fields like political science and economics and qualitative fields like history" noting that Tauger makes no comments on one of her paper's results section.<ref name="naumenkoresponse" /> | |||

| This disparity between agricultural goals, and actual production grew later in the year. An expected 190 thousand tons of grain were to be exported, but by ], ], only 20 thousand tons were ready. By October 25, the plan for grain collection was lowered once again, from the quantity called for in the plan of ], ]. Nevertheless, collection reached only 39% of the annually planned total.<ref>С. Кульчицький, Голодомор-33: сталінський задум та його виконання (), ''Проблеми Історіїї України факти, судження, пошуки'', №15, 2006, сс. 190-264</ref> A second lowering of goals deducted 70 million poods but still demanded plan completion, and 100% efficiency. Attempts to reach the new goals of production proved futile in late 1932. On ], in order to complete the plan, Ukraine was to collect 94 million poods, 4.8 of them from sovkhozes. As of ], targets were again lowered, to 62.5 million poods. Later that month, on January 14,the targets were lowered even further– by 29.4 million poods, to 33.1 million. At same time, GPU of Ukraine reported hunger and starvation in the ] and ] oblasts, and began implementing measures to remedy the situation. The total amount of grain collected by February 5 was only 255 million poods (compared to 440 million poods in 1931) while the numbers of “hunger and malnutrition cases” as registered by the GPU of Ukrainian SSR, increased every day. | |||

| <br clear="all" /> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" align=right style="margin: 1em auto 1em 2em" | |||

| |+ <!------> USSR Grain production and collections, 1930–33<br>(million tons) | |||

| ! Year || Production || Collections|| Remainder||Collections as<br>% of production | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1930|| 73-77 || 22.1 || 51-55 || 30.2-28.7 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1931|| 57-65 || 22.8 || 34-43 || 40-35.1 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1932|| 55-60 || 18.5 || 36.5-41.5 || 33.6-30.8 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1933|| 70-77 || 22.7 || 47.3-54.3 || 32.4-29.5 | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| <br clear="all" /> | |||

| Whilst the long-lasting effect of overall collectivization had an adverse effect on agricultural output everywhere, Ukraine had long been the most agriculturally productive area, providing over 50% of exported grain and 25% of total production of grain in the ] in 1913. Over 228,936 square kilometres (56.571 million acres), 207,203 km² (51.201 million acres) were used for grain production, or 90.5% of total arable land. This degree of dependency on agriculture meant that the effects of a bad harvest could be almost unlimited. This had been long recognised, and while projections for agricultural production were adjusted, the shock of limited production could not be easily managed. While collections by the state were in turn, limited, there were already clear stresses. The 1932 total Soviet harvest, was to be 29.5 million tons{{Vague|which tons?|date=March 2008}} in state collections of grain out of 90.7 million tons in production. But the actual result was a disastrous 55-60 million tons in production. The state ended up collecting only 18.5 million tons in grain.<ref name="DW448">Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 448</ref> The total Soviet collections by the state were virtually the same in 1930 and 1931 at about 22.8 million tons. For 1932, they had significantly been reduced to 18.5 million tons; with even lower figure in Ukraine. These were the total estimated outcomes of the grain harvests:<ref name="DW448" /> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" align=right style="margin: 1em auto 1em 2em" | |||

| |+ <!------> Ukrainian SSR Grain production and collections, 1927–33 (million tons) | |||

| ! Year || Production || Collections | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1927|| 18.67 || 0.83 centralized collection only | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1928|| 13.88 || 1.44 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1929|| 18.7 || 4.56 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1930|| 22.72 || 6.92 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1931|| 18.34 || 7.39 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1932|| 14.65 || 4.28 | |||

| |- | |||

| | 1933|| 22.29 (including ]) | |||

| || 5.98 | |||

| |- | |||

| |} | |||

| ===Peasants action and inaction === | |||

| Among other factors which contributed to the situation in spring 1933 mentioned an argument that the peasants “incentive to work disappeared” when they worked at “large collective farms.” Soviet archival data for 1930-32 also support that conclusion. | |||

| This is one of the factors for reducing the sowing area in 1932 and significant losses during harvesting. <ref name="Tauger2001"> Mark B. Tauger, Natural Disaster and Human Actions in the Soviet Famine of 1931-33,''The Carl Beck Papers in Russian & East European Studies'', # 1506, 2001, {{ISSN|0889-275X}}, ()</ref> | |||

| Tauger made a counter-reply to this reply by Naumenko.<ref name="taugerresponseresponse">Counter-Reply to Naumenko on the Soviet Famine in Ukraine in 1933 Mark B. Tauger EJW Econ Journal Watch March 2024</ref> Tauger argues in his counter reply that Naumenko's attempt to correspond collectivization rates to famine mortality fails because "there was no single level of collectivization anywhere in the USSR in 1930, especially in the Ukrainian Republic" and that "since collectivization changed significantly by 1932–1933, any connection between 1930 and 1933 omits those changes and is therefore invalid".<ref name="taugerresponseresponse" /> Tauger also criticizes Naumenko's ignoring of statistics Tauger's presented where "in her reply she completely ignored the quantitative data presented in article" in which she against the evidence "denied that any famines took place in the later 1920s".<ref name="taugerresponseresponse" /> To counter Naumenko's claim that collectivization explains the famine Tauger argues ( in his words) how agro-environmental disasters better explain the regional discrepancies: " calculations again omit any consideration of the agro-environmental disasters that harmed farm production in 1932. In her appendices, Table C3, she does the same calculation with collectivization data from 1932, which she argues shows a closer correlation between collectivization and famine mortality (Naumenko 2021b, 33). Yet, as I showed, those agroenvironmental disasters were much worse in the regions with higher collectivization—especially Ukraine, the North Caucasus, and the Volga River basin (and also in Kazakhstan)—than elsewhere in the USSR. As I documented in my article and other publications, these were regions that had a history of environmental disasters that caused crop failures and famines repeatedly in Russian history."<ref name="taugerresponseresponse" /> Tauger notes: " assumption that collectivization subjected peasants to higher procurements, but in 1932 in Ukraine this was clearly not the case" as "grain procurements both total and per-capita were much lower in Ukraine than anywhere else in the USSR in 1932".<ref name="taugerresponseresponse" /> | |||

| By December 1932 0.725 millions of hectares of grain at most affected by famine at spring 1933 areas of Ukrainian SRR remains uncollected <ref> Голод 1932-1933 років на Україні: очима істориків, мовою документів. Document number № 118 </ref> | |||

| ==== Peasant resistance ==== | |||

| {{Holodomor}}{{genocide}} | |||

| A second significant factor was “the massacre of cattle by peasants not wishing to sacrifice their property for nothing to the collective farm.<ref></ref> | |||

| {{history of Ukraine}} | |||

| ], including the Ukrainian SSR, was not popular among the peasantry, and forced collectivisation led to numerous ]. The ] recorded 932 disturbances in Ukraine, 173 in the North Caucasus, and only 43 in the Central Black Earth Oblast (out of 1,630 total). Reports two years prior recorded over 4,000 unrests in Ukraine, while in other agricultural regions - Central Black Earth, Middle Volga, Lower Volga, and North Caucasus - the numbers were sightly above 1,000. OGPU's summaries also cited public proclamations of Ukrainian insurgents to restore the ], while reports by the Ukrainian officials included information about the declining popularity and authority of the party among peasants.<ref name="Kulchytskystalinslave">{{harvnb|Kulchytsky|2017}}; {{harvnb|Kulchytsky|2020}}; {{harvnb|Kulchytsky|2008}}</ref> Oleh Wolowyna comments that peasant resistance and the ensuing repression of said resistance was a critical factor for the famine in Ukraine and parts of Russia populated by national minorities like Germans and Ukrainians allegedly tainted by "fascism and bourgeois nationalism" according to Soviet authorities.{{sfn|Wolowyna|2021}} | |||

| === Regional variation === | |||

| During winter and spring of 1930–31, the Ukrainian agricultural authority "Narkomzem" Ukrainian SRR issued several reports about the significant decline of livestock and especially drought power caused by poor treatment, absence of ], stables/farms and due the "]s sabotage". | |||

| The collectivization and high procurement quota explanation for the famine is called into question by the fact that the oblasts of Ukraine with the highest losses were ] and ], which produced far lower amounts of grain than other sections of the country.{{sfn|Wolowyna|2021}} A potential explanation for this was that Kharkiv and Kyiv fulfilled and over fulfilled their grain procurements in 1930 which led to ]s in these oblasts having their procurement quotas doubled in 1931 compared to the national average increase in procurement rate of 9%. While Kharkiv and Kyiv had their quotas increased, the Odesa oblast and some raions of Dnipropetrovsk oblast had their procurement quotas decreased.{{sfn|Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute|2022}} | |||

| According to Nataliia Levchuk of the Ptoukha Institute of Demography and Social Studies, "the distribution of the largely increased 1931 grain quotas in Kharkiv and Kyiv oblasts by raion was very uneven and unjustified because it was done disproportionally to the percentage of wheat sown area and their potential grain capacity."{{sfn|Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute|2022}} | |||

| <br clear="all" /> | |||

| {| class="wikitable |

{| class="wikitable sortable" | ||

| |+ Famine losses by region{{sfn|Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute|2018}} | |||

| |+ <!------> Ukrainian SSR livestock (thousand head) | |||

| ! Year ||Total<br>Horses</center>||<center> Working<br>Horses </center>||<center> Total Cattle </center>||<center> Oxen </center>||<center> Bulls </center>||<center> Cows </center>||<center> Pigs </center>||<center> Sheep<br>and Goats | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| ! Oblast !! Total Deaths (1932–1934 in thousands) !! Deaths per 1000 (1932) !! Deaths per 1000 (1933) !! Deaths per 1000 (1934) | |||

| |<center>1927</center>||<center> 5056.5</center>||<center> 3900.1</center>||<center> 8374.5</center>||<center> 805.5</center>||<center> …</center>||<center> 3852.1</center>||<center> 4412.4</center>||<center> 7956.3 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 1110.8 || 13.7 || 178.7 || 7 | |||

| |<center>1928</center>||<center> 5486.9</center>||<center> 4090.5</center>||<center> 8604.8</center>||<center> 895.3</center>||<center> 32.8</center>||<center> 3987.0</center>||<center> 6962.9</center>||<center> 8112.2 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 1037.6 || 7.8 || 178.9 || 4.2 | |||

| |<center>1929</center>||<center> 5607.5</center>||<center> 4198.8</center>||<center> 7611.0</center>||<center> 593.7</center>||<center> 26.9</center>||<center> 3873.0</center>||<center> 4161.2</center>||<center> 7030.8 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 545.5 || 5.9 || 114.6 || 5.2 | |||

| |<center>1930</center>||<center> 5308.2</center>||<center> 3721.6</center>||<center> 6274.1</center>||<center> 254.8</center>||<center> 49.6</center>||<center> 3471.6</center>||<center> 3171.8</center>||<center> 4533.4 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 368.4 || 5.4 || 91.6 || 4.7 | |||

| |<center>1931</center>||<center> 4781.3</center>||<center> 3593.7</center>||<center> 6189.5</center>||<center> 113.8</center>||<center> 40.0</center>||<center> 3377.0</center>||<center> 3373.3</center>||<center> 3364.8 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 326.9 || 6.1 || 98.8 || 2.4 | |||

| |1932</center>||<center> 3658.9</center>||<center> …</center>||<center> 5006.7</center>||<center> 105.2</center>||<center> …</center>||<center> 2739.5</center>||<center> 2623.7</center>||<center> 2109.5 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 254.2 || 6 || 75.7 || 11.9 | |||

| |<center>1933</center>||<center> 2604.8</center>||<center> …</center>||<center> 4446.3</center>||<center> 116.9</center>||<center> …</center>||<center> 2407.2</center>||<center> 2089.2</center>||<center> 2004.7 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 230.8 || 7 || 41.1 || 6.4 | |||

| |<center>1934</center>||<center> 2546.9</center>||<center> 2197.3</center>||<center> 5277.5</center>||<center> 156.5</center>||<center> 46.7</center>||<center> 2518.0</center>||<center> 4236.7</center>||<center> 2197.1 | |||

| |- | |- | ||

| | ] || 68.3 || 9.6 || 102.4 || 8.1 | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| === Repressive policies === | |||

| ===Legislation provisions=== | |||

| ]es and their punishment in the ], ], Ukraine.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Several repressive policies were implemented in Ukraine immediately preceding, during, and proceeding the famine, including but not limited to cultural-religious persecution the ], ], ], and harsh grain requisitions. | |||

| On ], ], the Soviet government passed a law "On the Safekeeping of Socialist Property"<ref name="TICirc">Konchalovsky and Lipkov, The Inner Circle, ], New York: 1991, p.54</ref> that imposed from a ten year prison sentence up to the death penalty for any theft of socialist property.<ref>Potocki, p. 320.</ref><ref>Serczyk, p. 311.</ref><ref>Andrew Gregorovich, , Ukrainian Canadian Research & Documentation Centre, Toronto 1998.</ref><ref name="TICirc" /> Stalin personally appended the stipulation: "People who encroach on socialist property should be considered ]."<ref name="TICirc" /> Additionally, the age limit for the death penalty was reduced to 12 years old: children were shot for gathering ears of corn left in the field after harvest.<ref name="TICirc" /> Within the first five months of passage of the law, 54,645 individuals had been sentenced under it and 2,110 executed.<ref name="TICirc" /> The initial wording of the Decree "On fought with speculation” adopted August 22 1932 lead to common situations where minor acts such as bartering tobacco for bread were documented as punished by 5 years imprisonment.<ref name="TICirc" />; After 1934,by NKVD demand, the penalty for minor offenses was limited to a fine of 500 ]s or 3 month of correctional labor. | |||

| The scope of this law, colloquially dubbed the "],"<ref name="TICirc" /> included even the smallest appropriation of grain by peasants for personal use. In little over a month the law was revised, as ] protocols revealed that secret decisions had later modified the original decree of ], ]. The Politburo approved a measure that specifically exempted small-scale theft of socialist property from the death penalty declaring that "organizations and groupings destroying state, social, and co-operate property in an organized manner by fires, explosions and mass destruction of property shall be sentenced to execution without trial", and listed a number of cases in which "kulaks, former traders and other socially-alien persons" would be subject to the death penalty. "Working individual peasants and collective farmers" who stole kolkhoz property and grain should be sentenced to ten years; the death penalty should be imposed only for "systematic theft of grain, sugar beets, animals, etc."<ref name="DW167_168_198_203">Davies and Wheatcroft, pp.167-168, 198-203</ref> | |||

| Soviet expectations for the 1932 grain crop were high because of Ukraine's bumper crop the previous year, which Soviet authorities believed were sustainable. When it became clear that the 1932 grain deliveries were not going to meet the expectations of the government, the decreased agricultural output was blamed on the "]s", and later to agents and spies of foreign Intelligence Services - "nationalists", and "]" and from 1937 on trotskyists. According to a report of the head of the Supreme Court, by ], ] as many as 103,000 people (more than 14 thousand in the Ukrainian SSR) had been sentenced under the provisions of the ] decree. Of the 79,000 whose sentences were known to the Supreme Court, 4,880 had been sentenced to death, 26,086 to ten years' imprisonment and 48,094 to other sentences.<ref name="DW167_168_198_203" /> | |||

| On ], Molotov and Stalin issued an order stating "from today the dispatch of goods for the villages ''of all regions of Ukraine'' shall cease until kolkhozy and individual peasants begin to honestly and conscientiously fulfill their duty to the working class and the Red Army by delivering grain."<ref name="DW174">Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 174.</ref> | |||

| On ], the Politburo instructed that all those sentenced to confinement of three years or more in Ukraine be deported to labor camps. It also simplified procedures for confirming death sentences in Ukraine. The Politburo also dispatched Balytsky to Ukraine for six months with the full powers of the OGPU.<ref name="DW175">Davies and Wheatcroft, p. 175.</ref> | |||

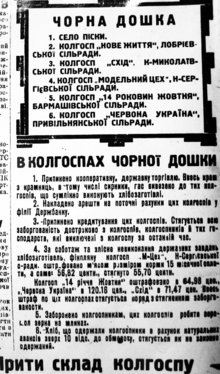

| The existed practice of administrative punishment known as “black board” (black list) by the November, 18 Decree of Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolshevik) of Ukraine was applied to a greater extent and with more harsh methods to selected villages and kolkhozes that were considered to be "underperforming" in the grain collection procurement: “Immediate cessation of delivery of goods, complete suspension of cooperative and state trade in the villages, and removal of all available goods from cooperative and state stores”. Full prohibition of collective farm trade for both collective farms and collective farmers, and for private farmers. Cessation of any sort of credit and demand for early repayment of credit and other financial obligations.” <ref>Rajca, p. 321.</ref><ref name="Grainmemo">, Addendum to the minutes of Politburo No. 93. Resolution on blacklisting villages. December 1932</ref> Initially such sanctions were applied to only 6 villages, but later they were applied to numerous rural settlements and districts. For peasants, who were not kolkhoz members and who were "underperforming" in the grain collection procurement, - special “measures” were adopted. To “reach the grain procurement quota” amongst peasants 1100 brigades were organized which consisted of activists (often from neighboring villages) which had accomplished their grain procurement quota or were close to accomplishing it. | |||

| Since most of goods supplied to the rural areas was commercial (fabrics, matches, fuels) and was sometimes obtained by villagers from neighbored cities or railway stations, sanctioned villages remained for a long period – as an example mentioned in December 6 Decree the village of Kamyani Potoky was removed from blacklist only ], ] when they completed their plan for grain collection early. Since January 1933 the black list regime was “softened” when 100% of plan execution was no longer demanded, mentioned in December 6 Decree villages Liutenky and Havrylivka were removed from the black list after 88 and 70% of plan completion respectively. | |||

| Measures were undertaken to persecute those withholding or bargaining grain. This was done frequently by requisition detachments, which raided farms to collect grain, and was done regardless of whether the peasants retained enough grain to feed themselves, or whether they had enough seed left to plant the next harvest. | |||

| ==== Preceding the famine ==== | |||

| ===Procurement practice === | |||

| {{see also|Union for the Freedom of Ukraine process}} | |||

| Coiner of the term ], ] considered the repression of the Orthodox Church to be a prong of ] against Ukrainians when seen in correlation to the Holodomor famine.{{sfn|Serbyn|2015}} Collectivization did not just entail the acquisition of land from farmers but also the closing of churches, burning of icons, and the arrests of priests.{{sfn|Fitzpatrick|1994|p=6}} Associating the church with the tsarist regime,{{sfn|Fitzpatrick|1994|p=33}} the Soviet state continued to undermine the church through expropriations and repression.{{sfn|Viola|1999}} They cut off state financial support to the church and secularized church schools.{{sfn|Fitzpatrick|1994|p=33}} | |||

| By early 1930 75% of the Autocephalist ] in Ukraine were persecuted by Soviet authorities.{{sfn|Bociurkiw|1982}} The GPU instigated a show trial which denounced the Orthodox Church in Ukraine as a "nationalist, political, counter-revolutionary organization" and instigated a staged "self-dissolution."{{sfn|Bociurkiw|1982}} However the Church was later allowed to reorganize in December 1930 under a pro-Soviet cosmopolitan leader of ] yet purges of the Church reignited during the ].{{sfn |Bociurkiw|1982}} Changes in cultural politics also occurred. | |||

| In 1928, a "by contract" policy of procurement (contracts for the delivery of agricultural products) was implemented for kolkhozes and ordinary peasants alike ("kulaks" had a "firm" plan for procurement). Accordingly, from 1928 through January 1933, "grain production areas" were required to submit 1/3–1/4 of their estimated yield, while areas designated as "grain" were required to submit no more than 1/8 of their estimated yield. However, between the Autumn of 1930 and the Spring of 1932, local authorities tended to collect products from kolkhozes in amounts greater than the minimum required in order to exceed the contracted target (in some cases by more than 200%). Especially harmful methods utilized in the "by contract" policy were "counterplan" actions, which were additional collection plans implemented in already fulfilled contracts. Such "counterplan" measures were strictly forbidden after the Spring of 1933 as "extremely harmful for kolkhoz development."<ref>Soviet Agricultural Encyclopedia 1-st edition 1932-35 Moscow</ref> | |||