| Revision as of 12:07, 2 January 2009 editArnoldReinhold (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators31,138 edits →Dynamics: clarify caption← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 08:50, 9 September 2024 edit undo文爻林夕 (talk | contribs)142 editsmNo edit summary | ||

| (122 intermediate revisions by 76 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Group of asteroids in orbital resonance with Jupiter}} | |||

| {{Cleanup|date=November 2007}} | |||

| ] |

] and ]: The ''Hilda group'' is located between the asteroid belt and the orbit of Jupiter. | ||

| {| style="width:100%;" | |||

| |- | |||

| | valign=top | | |||

| {{legend2|#6ad768|border=1px solid #2B9929|]s}}<br /> | |||

| {{legend2|#007DD6|border=1px solid #00508A|]s of ]s}}<br /> | |||

| {{legend2|#FFFF00|border=1px solid #B3B300|]}} | |||

| | valign=top | | |||

| {{legend2|#d39300|border=1px solid #855D00|'''''Hilda group'''''}}<br /> | |||

| {{legend2|#e9e9e9|border=1px solid #999999|]}}<br /> | |||

| {{legend2|#c90000|border=1px solid #940000|]s {{small|(selection)}}}} | |||

| |} | |||

| ]] | |||

| The '''Hilda asteroids''' (adj. ''Hildian'') are a ] of more than 6,000 ]s located beyond the ] but within ]'s orbit, in a 3:2 ] with Jupiter.<ref name="MPC-hilda-list" /><ref name="Broz-2008" /> The namesake is the asteroid ]. | |||

| The '''Hilda family of asteroids''' consists of ]s with a ] between 3.7 AU and 4.2 AU, an ] greater than 0.07, and an ] less than 20°. They do not form a true ], in the sense that they do not descend from a common parent object. Instead, this is a ''dynamical'' family of bodies, made up of asteroids which are in a 2:3 ] with ]. Hildas move in their elliptical orbits so that their ] put them opposite Jupiter, or 60 degrees ahead of or behind Jupiter at the L<sub>4</sub> and L<sub>5</sub> ]s. Over three successive orbits each Hilda asteroid passes through all of these three points in sequence. The namesake is ], discovered by ] in ]. | |||

| Hildas move in their elliptical orbits in such a fashion that they arrive closest to Jupiter's orbit (i.e. at their ]) just when either one of Jupiter's {{L5}}, {{L4}} or {{L3}} ]s arrives there.<ref name="easysky">{{cite web |title=The triangle formed by the Hilda asteroids |publisher=EasySky |author=Matthias Busch |url=http://www.easysky.de/eng/screenshots/Hildas.htm |access-date=2009-12-15 | |||

| ⚫ | == Dynamics == | ||

| }}</ref> On their next orbit their aphelion will synchronize with the next Lagrange point in the {{L5}}–{{L4}}–{{L3}} sequence. Since {{L5}}, {{L4}} and {{L3}} are 120° apart, by the time a Hilda completes an orbit, Jupiter will have completed 360° − 120° or two-thirds of its own orbit. A Hilda's orbit has a ] between 3.7 and 4.2 ] (the average over a long time span is 3.97), an ] less than 0.3, and an ] less than 20°.<ref name="Ohtsukaetal2008">{{cite journal |bibcode = 2008A&A...489.1355O |title = Quasi-Hilda comet 147P/Kushida-Muramatsu. Another long temporary satellite capture by Jupiter |last1 = Ohtsuka |first1 = Katsuhito |last2 = Yoshikawa |first2 = M. |last3 = Asher |first3 = D. J. |last4 = Arakida |first4 = H. |journal = Astronomy and Astrophysics |volume = 489 |issue = 3 |date = October 2008 |pages = 1355–1362 |doi = 10.1051/0004-6361:200810321 |last5 = Arakida |first5 = H. | |||

| |arxiv = 0808.2277 |s2cid = 14201751 }}</ref> Two ] exist within the Hilda group: the ] and the ]. The namesake for the latter family is ].<ref name=Broz_Vokrouhlicky>{{cite journal|last=Brož|first=M.|author2=Vokrouhlický, D.|title=Asteroid families in the first-order resonances with Jupiter|journal=Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society|date=2008|volume=390|issue=2|pages=715–732|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13764.x|doi-access=free |arxiv=1104.4004|bibcode=2008MNRAS.390..715B|s2cid=53965791}}</ref> | |||

| The surface colors of Hildas often correspond to the low-albedo ] and ]; however, a small portion are ]. D-type and P-type asteroids have surface colors, and thus also surface mineralogies, similar to those of ]. This implies that they share a common origin.<ref name="Ohtsukaetal2008"/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Gil-Hutton|first=R.|author2=Brunini, Adrián|title=Surface composition of Hilda asteroids from the analysis of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey colors|journal=Icarus|volume=193|issue=2|pages=567–571|url=http://sedici.unlp.edu.ar/handle/10915/2097|access-date=14 April 2014|doi=10.1016/j.icarus.2007.08.026|bibcode=2008Icar..193..567G|year=2008}}</ref> | |||

| ⚫ | The asteroids of the Hilda group (Hildas) are in 3:2 ] with Jupiter. That is, their ]s are 2/3 that of Jupiter. |

||

| ⚫ | == Dynamics == | ||

| ⚫ | The Hildas taken together constitute a dynamic triangular figure with slightly convex sides and trimmed |

||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | The asteroids of the Hilda group (Hildas) are in 3:2 ] with Jupiter.<ref name="Ohtsukaetal2008" /> That is, their ]s are 2/3 that of Jupiter. They move along the orbits with a semimajor axis near 4.0 AU and moderate values of eccentricity (up to 0.3) and inclination (up to 20°). Unlike the ]s they may have any difference in longitude with Jupiter, nevertheless avoiding dangerous approaches to the planet. | ||

| ⚫ | Each of the Hilda objects moves along its own ]. |

||

| ⚫ | The Hildas taken together constitute a dynamic triangular figure with slightly convex sides and trimmed apices in the triangular ] of Jupiter—the "Hildas Triangle".<ref name="easysky"/> The "asteroidal stream" within the sides of the triangle is about 1 ] wide, and in the apices this value is 20–40% greater. Figure 1 shows the positions of the Hildas (black) against a background of all known asteroids (gray) up to Jupiter's orbit at January 1, 2005.<ref>L'vov V.N., Smekhacheva R.I., Smirnov S.S., Tsekmejster S.D. Some peculiarities in the Hildas motion. Izv. Pulkovo Astr. Obs., 2004, 217, 318–324 (in Russian)</ref> | ||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | Each of the Hilda objects moves along its own ]. However, at any moment the Hildas together constitute a loosely-triangular configuration, and all the orbits together form a predictable ring. Figure 2 illustrates this with the Hildas positions (black) against a background of their orbits (gray). For the majority of these asteroids, their position in orbit may be arbitrary, except for the external parts of the apexes (the objects near aphelion) and the middles of the sides (the objects near perihelion). The Hildas Triangle has proven to be dynamically stable over a long time span.{{cn|date=April 2019}} | ||

| ⚫ | The typical Hilda object has a ]. |

||

| ⚫ | The typical Hilda object has a ]. On average, the velocity of perihelion motion is greater when the orbital eccentricity is lesser, while the nodes move more slowly. All typical objects in aphelion would seemingly approach closely to Jupiter, which should be destabilising for them—but the variation of the orbital elements over time prevents this, and ] with Jupiter occur only near the perihelion of Hilda asteroids. Moreover, the ] line oscillates near the line of conjunction with different amplitude and a period of 2.5 to 3.0 centuries. | ||

| ⚫ | In addition to the fact that the Hildas triangle revolves in |

||

| ⚫ | In addition to the fact that the Hildas triangle revolves in sync with Jupiter, the density of asteroids in the stream exhibits quasi-periodical waves. At any time, the density of objects in the triangle's apexes is more than twice the density within the sides. The Hildas "rest" at their aphelia in the apexes for an average of 5.0–5.5 years, whereas they move along the sides more quickly, averaging 2.5 to 3.0 years. The ]s of these asteroids are approximately 7.9 years, or two thirds that of Jupiter. | ||

| ]]] | |||

| Although the triangle is nearly ] some asymmetry exists. Due to the eccentricity of Jupiter's orbit the side |

Although the triangle is nearly ], some asymmetry exists. Due to the eccentricity of Jupiter's orbit, the side {{L4}}–{{L5}} slightly differs from the two other sides. When Jupiter is in ], the mean velocity of the objects moving along this side is somewhat smaller than that of the objects moving along the other two sides. When Jupiter is in ], the reverse is true. | ||

| ⚫ | At the apexes of the triangle corresponding to the points {{L4}} and {{L5}} of Jupiter's orbit, the Hildas approach the ]. At the mid-sides of the triangle, they are close to the asteroids of the external part of the ]. The velocity dispersion of Hildas is more evident than that of Trojans in the regions where they intersect. The dispersion of Trojans in ] is twice that of the Hildas. Due to this, as much as one quarter of the Trojans cannot intersect with the Hildas, and at all times many Trojans are located outside Jupiter's orbit. Therefore, the regions of intersection are limited. This is illustrated by the adjacent figure that shows the Hildas (black) and the Trojans (gray) along the ]. One can see the spherical form of the Trojan swarms. | ||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | When moving along each side of the triangle, the Hildas travel more slowly than the Trojans, but encounter a denser neighborhood of outer-asteroid-belt asteroids. Here, the velocity dispersion is much smaller. | ||

| ⚫ | At the apexes of the triangle corresponding to the points |

||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ⚫ | When moving along each side of the triangle the Hildas travel |

||

| |direction = horizontal | |||

| |align = center | |||

| |width1 = 225 | |||

| |width2 = 319 | |||

| |width3 = 225 | |||

| |image1 = HildasOrbitWithLagrangePointsLousy.gif | |||

| |image2 = hildas02.gif | |||

| |image3 = Hilda asteroid as seen from Jupiter.png | |||

| |footer = ''Left'': A schematic of the orbit of ] (green), with ] (red); ''Middle'': Hildas (black) and Trojans viewed from the ecliptic plane near 190 degrees longitude on Jan. 1, 2005. ''Right'': Orbits of two idealized asteroids of the Hilda group, in the rotating reference frame of Jupiter's orbit. Black: eccentricity 0.310; aphelion at Jupiter's orbit. Red: eccentricity 0.211, the critical value for existence of a cusp. | |||

| }} | |||

| == Research == | == Research == | ||

| ⚫ | The observed peculiarities in the Hildas' motion are based on data for a few hundred objects known to date and generate still more questions. Further observations are needed to expand on the list of Hildas. Such observations are most favorable when Earth is near ] with the mid-sides of the Hildas Triangle, because that is when the asteroids are closest to Earth, and in opposition with the Sun. They are therefore at their brightest during these moments which occur every 4 and 1/3 months. In these circumstances the ] of objects of similar size could run up to 2.5 magnitudes as compared to the apices.{{cn|date=September 2017}} | ||

| ⚫ | The Hildas traverse regions of the Solar system from approximately 2 AU up to Jupiter's orbit. This entails a variety of physical conditions and the neighborhood of various groups of asteroids. On further observation some theories on the Hildas may have to be revised.{{cn|date=September 2017}} | ||

| ⚫ | The observed peculiarities in the Hildas' motion are based on data for a few hundred objects known to date and generate still more questions. |

||

| ⚫ | == References == | ||

| ⚫ | The Hildas |

||

| ⚫ | {{reflist|refs= | ||

| <ref name="MPC-hilda-list">{{cite web | |||

| ⚫ | ==References== | ||

| |title = Objects with orbit type Hilda – Database query | |||

| ⚫ | {{reflist |

||

| |work = ] | |||

| |url = https://minorplanetcenter.net/db_search/show_by_orbit_type?&orbit_type=8 | |||

| |access-date = 14 September 2018}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Broz-2008">{{Cite journal | |||

| |first1 = M. |last1 = Broz | |||

| |first2 = D. |last2 = Vokrouhlický | |||

| |date = October 2008 | |||

| |title = Asteroid families in the first-order resonances with Jupiter | |||

| |journal = Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society | |||

| |volume = 390 | |||

| |issue = 2 | |||

| |pages = 715–732 | |||

| |bibcode = 2008MNRAS.390..715B | |||

| |doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13764.x | |||

| |doi-access = free | |||

| |arxiv = 1104.4004 | |||

| |s2cid = 53965791 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| }} <!-- end of reflist --> | |||

| {{Small Solar System bodies}} | {{Small Solar System bodies}} | ||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Hilda Family}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 08:50, 9 September 2024

Group of asteroids in orbital resonance with Jupiter

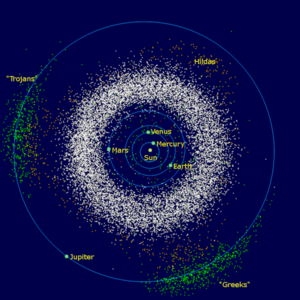

| Jupiter trojans Orbits of planets Sun | Hilda group Asteroid belt Near-Earth objects (selection) |

The Hilda asteroids (adj. Hildian) are a dynamical group of more than 6,000 asteroids located beyond the asteroid belt but within Jupiter's orbit, in a 3:2 orbital resonance with Jupiter. The namesake is the asteroid 153 Hilda.

Hildas move in their elliptical orbits in such a fashion that they arrive closest to Jupiter's orbit (i.e. at their aphelion) just when either one of Jupiter's L5, L4 or L3 Lagrange points arrives there. On their next orbit their aphelion will synchronize with the next Lagrange point in the L5–L4–L3 sequence. Since L5, L4 and L3 are 120° apart, by the time a Hilda completes an orbit, Jupiter will have completed 360° − 120° or two-thirds of its own orbit. A Hilda's orbit has a semi-major axis between 3.7 and 4.2 AU (the average over a long time span is 3.97), an eccentricity less than 0.3, and an inclination less than 20°. Two collisional families exist within the Hilda group: the Hilda family and the Schubart family. The namesake for the latter family is 1911 Schubart.

The surface colors of Hildas often correspond to the low-albedo D-type and P-type; however, a small portion are C-type. D-type and P-type asteroids have surface colors, and thus also surface mineralogies, similar to those of cometary nuclei. This implies that they share a common origin.

Dynamics

Fig 2: The positions of the Hildas against a background of their orbits.

The asteroids of the Hilda group (Hildas) are in 3:2 mean-motion resonance with Jupiter. That is, their orbital periods are 2/3 that of Jupiter. They move along the orbits with a semimajor axis near 4.0 AU and moderate values of eccentricity (up to 0.3) and inclination (up to 20°). Unlike the Jupiter trojans they may have any difference in longitude with Jupiter, nevertheless avoiding dangerous approaches to the planet.

The Hildas taken together constitute a dynamic triangular figure with slightly convex sides and trimmed apices in the triangular libration points of Jupiter—the "Hildas Triangle". The "asteroidal stream" within the sides of the triangle is about 1 AU wide, and in the apices this value is 20–40% greater. Figure 1 shows the positions of the Hildas (black) against a background of all known asteroids (gray) up to Jupiter's orbit at January 1, 2005.

Each of the Hilda objects moves along its own elliptic orbit. However, at any moment the Hildas together constitute a loosely-triangular configuration, and all the orbits together form a predictable ring. Figure 2 illustrates this with the Hildas positions (black) against a background of their orbits (gray). For the majority of these asteroids, their position in orbit may be arbitrary, except for the external parts of the apexes (the objects near aphelion) and the middles of the sides (the objects near perihelion). The Hildas Triangle has proven to be dynamically stable over a long time span.

The typical Hilda object has a retrograde perihelion motion. On average, the velocity of perihelion motion is greater when the orbital eccentricity is lesser, while the nodes move more slowly. All typical objects in aphelion would seemingly approach closely to Jupiter, which should be destabilising for them—but the variation of the orbital elements over time prevents this, and conjunctions with Jupiter occur only near the perihelion of Hilda asteroids. Moreover, the apsidal line oscillates near the line of conjunction with different amplitude and a period of 2.5 to 3.0 centuries.

In addition to the fact that the Hildas triangle revolves in sync with Jupiter, the density of asteroids in the stream exhibits quasi-periodical waves. At any time, the density of objects in the triangle's apexes is more than twice the density within the sides. The Hildas "rest" at their aphelia in the apexes for an average of 5.0–5.5 years, whereas they move along the sides more quickly, averaging 2.5 to 3.0 years. The orbital periods of these asteroids are approximately 7.9 years, or two thirds that of Jupiter.

Although the triangle is nearly equilateral, some asymmetry exists. Due to the eccentricity of Jupiter's orbit, the side L4–L5 slightly differs from the two other sides. When Jupiter is in aphelion, the mean velocity of the objects moving along this side is somewhat smaller than that of the objects moving along the other two sides. When Jupiter is in perihelion, the reverse is true.

At the apexes of the triangle corresponding to the points L4 and L5 of Jupiter's orbit, the Hildas approach the Trojans. At the mid-sides of the triangle, they are close to the asteroids of the external part of the asteroid belt. The velocity dispersion of Hildas is more evident than that of Trojans in the regions where they intersect. The dispersion of Trojans in inclination is twice that of the Hildas. Due to this, as much as one quarter of the Trojans cannot intersect with the Hildas, and at all times many Trojans are located outside Jupiter's orbit. Therefore, the regions of intersection are limited. This is illustrated by the adjacent figure that shows the Hildas (black) and the Trojans (gray) along the ecliptic plane. One can see the spherical form of the Trojan swarms.

When moving along each side of the triangle, the Hildas travel more slowly than the Trojans, but encounter a denser neighborhood of outer-asteroid-belt asteroids. Here, the velocity dispersion is much smaller.

Left: A schematic of the orbit of 153 Hilda (green), with Jupiter (red); Middle: Hildas (black) and Trojans viewed from the ecliptic plane near 190 degrees longitude on Jan. 1, 2005. Right: Orbits of two idealized asteroids of the Hilda group, in the rotating reference frame of Jupiter's orbit. Black: eccentricity 0.310; aphelion at Jupiter's orbit. Red: eccentricity 0.211, the critical value for existence of a cusp.

Left: A schematic of the orbit of 153 Hilda (green), with Jupiter (red); Middle: Hildas (black) and Trojans viewed from the ecliptic plane near 190 degrees longitude on Jan. 1, 2005. Right: Orbits of two idealized asteroids of the Hilda group, in the rotating reference frame of Jupiter's orbit. Black: eccentricity 0.310; aphelion at Jupiter's orbit. Red: eccentricity 0.211, the critical value for existence of a cusp.

Research

The observed peculiarities in the Hildas' motion are based on data for a few hundred objects known to date and generate still more questions. Further observations are needed to expand on the list of Hildas. Such observations are most favorable when Earth is near conjunction with the mid-sides of the Hildas Triangle, because that is when the asteroids are closest to Earth, and in opposition with the Sun. They are therefore at their brightest during these moments which occur every 4 and 1/3 months. In these circumstances the brilliance of objects of similar size could run up to 2.5 magnitudes as compared to the apices.

The Hildas traverse regions of the Solar system from approximately 2 AU up to Jupiter's orbit. This entails a variety of physical conditions and the neighborhood of various groups of asteroids. On further observation some theories on the Hildas may have to be revised.

References

- "Objects with orbit type Hilda – Database query". Minor Planet Center. Retrieved 14 September 2018.

- Broz, M.; Vokrouhlický, D. (October 2008). "Asteroid families in the first-order resonances with Jupiter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 390 (2): 715–732. arXiv:1104.4004. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.390..715B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13764.x. S2CID 53965791.

- ^ Matthias Busch. "The triangle formed by the Hilda asteroids". EasySky. Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- ^ Ohtsuka, Katsuhito; Yoshikawa, M.; Asher, D. J.; Arakida, H.; Arakida, H. (October 2008). "Quasi-Hilda comet 147P/Kushida-Muramatsu. Another long temporary satellite capture by Jupiter". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 489 (3): 1355–1362. arXiv:0808.2277. Bibcode:2008A&A...489.1355O. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200810321. S2CID 14201751.

- Brož, M.; Vokrouhlický, D. (2008). "Asteroid families in the first-order resonances with Jupiter". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 390 (2): 715–732. arXiv:1104.4004. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.390..715B. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13764.x. S2CID 53965791.

- Gil-Hutton, R.; Brunini, Adrián (2008). "Surface composition of Hilda asteroids from the analysis of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey colors". Icarus. 193 (2): 567–571. Bibcode:2008Icar..193..567G. doi:10.1016/j.icarus.2007.08.026. Retrieved 14 April 2014.

- L'vov V.N., Smekhacheva R.I., Smirnov S.S., Tsekmejster S.D. Some peculiarities in the Hildas motion. Izv. Pulkovo Astr. Obs., 2004, 217, 318–324 (in Russian)

| Small Solar System bodies | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor planets |

| ||||||

| Comets | |||||||

| Other | |||||||