| Revision as of 21:48, 21 January 2009 editSwpb (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers93,319 edits Reverted edits by Swpb to version 240479869 by TaBOT-zerem← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:21, 11 January 2025 edit undoAnomieBOT (talk | contribs)Bots6,590,622 editsm Dating maintenance tags: {{Pn}} | ||

| (181 intermediate revisions by 87 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Cardinal direction for steering}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| In ], a '''course''' is the intended path of a vehicle over the surface of the Earth. For air travel, it is the intended flight path of an airplane or the direction of a line drawn on a chart representing the intended airplane path,<!-- What about maritime? --> expressed as the angle measured from a specific reference datum clockwise from 0° through 360° to the line. The reference can be ] or ] and called true course or magnetic course respectively. Course is customarily expressed in three digits, using preliminary zeros if needed. | |||

| In ], the '''course''' of a ] or ] is the ] in which the craft is to be ]. The course is to be distinguished from the '']'', which is the direction where the watercraft's ] or the aircraft's ] is pointed.<ref name="Bartlett"> | |||

| In order to be used in a chart<!-- or for ]--Find no reference, and doubt it -->, this reference has to be ]. | |||

| {{Citation|last=Bartlett|first=Tim|title=Adlard Coles Book of Navigations|year=2008|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RWUQAAAAQBAJ&q=pilotage|page=176|publisher=Adlard Coles|isbn=978-0713689396}}</ref><ref name=Chapman> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Husick | |||

| | first = Charles B. | |||

| | title = Chapman Piloting, Seamanship and Small Boat Handling | |||

| | publisher = Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. | |||

| | date = 2009 | |||

| | page = 927 | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=S4FwbS8StvEC&q=definition+nautical+course&pg=PA50 | isbn = 9781588167446 }}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Cite PHAK|year=2016}}</ref>{{pn|date=January 2025}} | |||

| The path that a vessel follows is called a '''track''' or, in the case of aircraft, '''ground track''' (also known as ''course made good'' or ''course over the ground'').<ref name="Bartlett" /> The intended track is a '''route'''. | |||

| == Discussion == | |||

| == Determining the true course of a vessel == | |||

| {{further|Bearing (angle)#Arcs|Rhumb line#Introduction}} | |||

| * ''']''' (2) is the direction the vessel, aircraft or vehicle is truly "pointing towards" (the heading of the ship shown in the image is 058°). | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| * Any reading from a magnetic compass refers to ''compass north'' (4), which is supposed to contain a two-part ''compass error:'' <br/>a) The earth's magnetic field's north direction, or ''magnetic north'' (3), almost always differs from true north by ] (6), the local amount of which is given in nautical charts, and <br/>b) ship's own magnetic field may influence the compass by so-called ] (5). <br/>Deviation only depends on the ship's own magnetic field and the heading, and therefore can be checked out and given as a ''deviation table'' or, graphically, as a ]. | |||

| | width1 = 200 | |||

| | footer = True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right) | |||

| | image1 = MISB ST 0601.8 - Platform Heading Angle.png | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | width2 = 200 | |||

| | image2 = MISB ST 0601.8 - Platform Magnetic Heading.png | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| For ships and aircraft, routes are typically ] segments between ]. A navigator determines the ''bearing'' (the compass direction from the craft's current position) of the next waypoint. Because water currents or wind can cause a craft to drift off course, a navigator sets a ''course to steer'' that compensates for drift. The helmsman or pilot points the craft on a ''heading'' that corresponds to the course to steer. If the predicted drift is correct, then the craft's track will correspond to the planned course to the next waypoint.<ref name="Bartlett" /><ref name=":0" /> Course directions are specified in degrees from north, either true or magnetic. In ], north is usually expressed as 360°.<ref name="Nolan2010">{{cite book|author=Michael Nolan|title=Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=6yhTiGC3ulcC&pg=PA201|date=2010|publisher=Cengage Learning|isbn=978-1-4354-8272-2|page=201|quote=For example, a runway heading north would have a magnetic heading of 360°.}}</ref> Navigators used ], instead of compass degrees, e.g. "northeast" instead of 45° until the mid-20th century when the use of degrees became prevalent.<ref>{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=xRqzoX04v5AC&q=cardinal+direction&pg=PA233|title=The Annapolis Book of Seamanship: Third Edition: Completely Revised, Expanded and Updated|last1=Rousmaniere|first1=John|last2=Smith|first2=Mark|date=1999|publisher=Simon and Schuster|isbn=9780684854205|pages=234|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| * The ''compass heading'' or ''compass course'' (7) has to be corrected first for deviation (the "nearer" error), wherefrom results the ''magnetic heading'' (8). Correcting this for variation yields ''true heading'' (2). | |||

| ⚫ | [[Image:Course (navigation).svg|center|upright=3|Heading and track (A to B)<br> | ||

| * In case of a ] (9), and/or ] or other current (10), the heading will not meet the desired target, as the vessel will continuously drift sideways; it is necessary to point away from the intended course to counteract these effects. | |||

| 1 – True North <br> | |||

| 2 – Heading, the direction the vessel is "pointing towards" <br> | |||

| == Track == | |||

| 3 – Magnetic north, which differs from true north by the magnetic variation. <br> | |||

| 4 – Compass north, including a two-part error; the magnetic variation (6) and the ship's own magnetic field (5) <br> | |||

| A '''track,''' also ''course over ground,'' is the actual path followed by a moving body, e.g. the vessel's track from A to B in the above given scheme. Some ambiguity exists in the fact that the path a navigator ''intends'' to follow, after evaluating and counteracting possible effects of wind and current, is also called ''track.'' | |||

| 5 – Magnetic deviation, caused by vessel's magnetic field. <br> | |||

| 6 – Magnetic variation, caused by variations in Earth's magnetic field. <br> | |||

| The track is equivalent to the heading (a ] "right ahead"), if no crosswind and cross current occur (2), or the vessel is stationary, but this would hardly ever happen in ]. | |||

| 7 – Compass heading or compass course, before correction for magnetic deviation or magnetic variation. <br> | |||

| 8 – Magnetic heading, the compass heading corrected for magnetic deviation but not magnetic variation; thus, the heading reliative to magnetic north. <br> | |||

| When wind is present, and is not a ] or ], the wind deflects the aircraft (or vessel) from its heading. | |||

| 9, 10 – Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading. <br> | |||

| A, B – Vessel's track.]] | |||

| To correct for the wind, the aircraft or vessel points more or less into the wind. The amount depends on the vehicle's speed, the wind's speed, and the angle of the wind in relation to the vehicle. This so-called ] is computed in advance and is frequently checked while "enroute". In the above scheme, the track would be (9) for wind from port side. | |||

| ] is an ] for storing track logs. | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| * The above scheme shows a ] of 6° East, as is commonly encountered in areas of the ], for instance, and a more-than-somewhat exaggerated deviation (taken from a fictitious deviation table for educational purpose) of +12°, for a compass heading of 040°. By conventional ], deviation could usually be kept beyond 10°, and ]es can be degaussed to almost D=0°. | |||

| * The possible influences of wind and current are maximized by presupposing a very slow boat in heavy wind and current. | |||

| * To increase readability of the scheme, all possible influences were given as positive, i.e. variation=East, + 12° deviation, wind and current from ]. The principle is the same for the opposite of any of the components.Initially a square symbol identifies a target in the beginning of acquisition and tracking phase. A line (vector) representing the target's relative direction of movement is displayed after 20 scans (usually less than one minute). Typically the square designator changes to a circle when steady state tracking is established after 60 scans. The end of the vector, representing target motion, predicts the position of the target after a time period between 0.5 and 30 minutes as selected by the operator. ARPA also shows pas positions of the target with a choice of 5,10 or 20 pas position dots at intervals of 0.5, 1,2,3, or 6 minutes. ARPA (Automatic Radar Plotting Aid) and ATA (Automatic Tracking Aid) have the ability to track 60 and 40 targets respectively at relative speeds of up to 150 knots. Tracked target data is output to other shipborne systems such as electronic chart systems (ECS). Targets may be acquired manually or by using the annular and polygonal automatic acquisition zones. The two conventional annular zones are of variable depth and provide protection over any arc up to and including a full circle around own ship. The polygonal zones can be drawn to virtually any shape and are particularly useful for shore-based or other static site applications. When target tracking, the operator is able to display full target data on any chosen target or CPA/TCPA data on six selected targets. The six targets may be selected manually by the operator or automatically by CPA or range. | |||

| == See also == | == See also == | ||

| {{Portal|Geography}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| ⚫ | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| ⚫ | ==References== | ||

| {{nautical portal}} | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ⚫ | *] | ||

| ⚫ | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| ⚫ | == |

||

| ⚫ | * | ||

| ==External links== | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ⚫ | * | ||

| * | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Course (Navigation)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:21, 11 January 2025

Cardinal direction for steering

In navigation, the course of a watercraft or aircraft is the cardinal direction in which the craft is to be steered. The course is to be distinguished from the heading, which is the direction where the watercraft's bow or the aircraft's nose is pointed. The path that a vessel follows is called a track or, in the case of aircraft, ground track (also known as course made good or course over the ground). The intended track is a route.

Discussion

Further information: Bearing (angle) § Arcs, and Rhumb line § Introduction

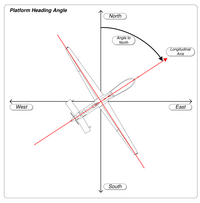

True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right)

True heading (left) and magnetic heading (right)

For ships and aircraft, routes are typically straight-line segments between waypoints. A navigator determines the bearing (the compass direction from the craft's current position) of the next waypoint. Because water currents or wind can cause a craft to drift off course, a navigator sets a course to steer that compensates for drift. The helmsman or pilot points the craft on a heading that corresponds to the course to steer. If the predicted drift is correct, then the craft's track will correspond to the planned course to the next waypoint. Course directions are specified in degrees from north, either true or magnetic. In aviation, north is usually expressed as 360°. Navigators used ordinal directions, instead of compass degrees, e.g. "northeast" instead of 45° until the mid-20th century when the use of degrees became prevalent.

1 – True North

2 – Heading, the direction the vessel is "pointing towards"

3 – Magnetic north, which differs from true north by the magnetic variation.

4 – Compass north, including a two-part error; the magnetic variation (6) and the ship's own magnetic field (5)

5 – Magnetic deviation, caused by vessel's magnetic field.

6 – Magnetic variation, caused by variations in Earth's magnetic field.

7 – Compass heading or compass course, before correction for magnetic deviation or magnetic variation.

8 – Magnetic heading, the compass heading corrected for magnetic deviation but not magnetic variation; thus, the heading reliative to magnetic north.

9, 10 – Effects of crosswind and tidal current, causing the vessel's track to differ from its heading.

A, B – Vessel's track.

See also

- Acronyms and abbreviations in avionics

- Glossary of navigation terms

- Bearing (navigation)

- Breton plotter

- E6B

- Great circle

- Ground track

- Navigation

- Navigation room

- Rhumb line

References

- ^ Bartlett, Tim (2008), Adlard Coles Book of Navigations, Adlard Coles, p. 176, ISBN 978-0713689396

- Husick, Charles B. (2009). Chapman Piloting, Seamanship and Small Boat Handling. Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 927. ISBN 9781588167446.

- ^ Pilot's Handbook of Aeronautical Knowledge (FAA-H-8083-25B ed.). Federal Aviation Administration. 2016-08-24. Archived from the original on 2023-06-20.

- Michael Nolan (2010). Fundamentals of Air Traffic Control. Cengage Learning. p. 201. ISBN 978-1-4354-8272-2.

For example, a runway heading north would have a magnetic heading of 360°.

- Rousmaniere, John; Smith, Mark (1999). The Annapolis Book of Seamanship: Third Edition: Completely Revised, Expanded and Updated. Simon and Schuster. p. 234. ISBN 9780684854205.