| Revision as of 16:04, 23 January 2009 editDomer48 (talk | contribs)16,098 edits →Legacy: Fact tagged since November 2008, as such its comment and opinion← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:07, 12 January 2025 edit undoRevirvlkodlaku (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users84,431 edits Updated short descriptionTags: Mobile edit Mobile app edit Android app edit App description change | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|17th-century colonisation of northern Ireland}} | |||

| {{Nofootnotes|date=February 2008}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Use dmy dates|date=February 2023}} | ||

| {{Use British English|date=June 2013}} | |||

| The '''Plantation of Ulster''' (Irish: '''Plandáil Uladh''') was planned in 1598 with the process of ] taking place in 1609. All the estates of the O'Neills, Earls of Tyrone; O'Donnella (Tyrconnell), and their chief supporters were confiscated. The estates comprised an estimated half a million acres (4,000 km²) of land (waste, woodland and bog were uncounted) in the counties of Donegal, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan, Coleraine(Londonderry) and Armagh in the northern Irish ] of ].<ref>T. A. Jackson, Ireland Her Own, Lawrence & Wishart (London) 1991 (New Edition), ISBN 0 85315 735 9, pg.51</ref> | |||

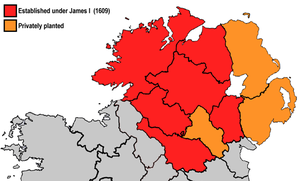

| ] (modern boundaries) that were colonised during the plantations. This map is a simplified one, as the amount of land actually colonised did not cover the entire shaded area.]] | |||

| The '''Plantation of Ulster''' ({{langx|ga|Plandáil Uladh}}; ]: {{lang|sco|Plantin o Ulstèr}}<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.doeni.gov.uk/niea/moneacastleus.pdf |title=Monea Castle and Derrygonnelly Church: Ulster-Scots translation |url-status=dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20110830193417/http://www.doeni.gov.uk/niea/moneacastleus.pdf |archive-date=30 August 2011 |date=2011 |work=DoENI.gov.uk |publisher=], ]}}</ref>) was the organised ] ('']'') of ]{{spaced ndash}}a ] of ]{{spaced ndash}}by people from ] during the reign of King ].<!--in England and Ireland he's James I--> | |||

| 'British’ tenants',<ref>Edmund Curtis, ''A History of Ireland: From Earliest Times to 1922'', Routledge (2000 RP), ISBN 0 415 27949 6, pg.198</ref> a term applied to the ] English and Scottish planters,<ref>T.W Moody & F.X. Martin, The Course of Irish History, Mercier Press 1984 (Second Edition). ISBN 0-85342-715-1, p 190</ref> of whom the Scottish were usually Presbyterian <ref>Edmund Curtis, ''A History of Ireland: From Earliest Times to 1922'', Routledge (2000 RP), ISBN 0 415 27949 6, pg.198</ref> and "persecuted" Dissenters, <ref>T. A. Jackson, ''Ireland Her Own'', Lawrence & Wishart (London) 1991 (New Edition), ISBN 0 85315 735 9, pg.52</ref> were then settled on land which had been confiscated from Irish landowners. The Plantation of Ulster was the biggest and most successful of the ]. Ulster was settled in this way to prevent further rebellion, as it had proved itself over the preceding century to be the most resistant of Ireland's provinces to English invasion. | |||

| Small privately funded plantations by wealthy landowners began in 1606,<ref name="Stewart 38">{{harvp|Stewart|1989|p=38}}.</ref><ref name="Falls 156-7">{{harvp|Falls|1996|pp=156–157}}.</ref><ref name="Perceval-Maxwell 55">{{harvp|Perceval-Maxwell|1999|p=55}}.</ref> while the official plantation began in 1609. Most of the land had been confiscated from the native ], several of whom ] for mainland Europe in 1607 following the ] against ]. The official plantation comprised an estimated half a million ] (2,000 km<sup>2</sup>) of ] in counties ], ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfnp||Jackson|1973|p=51}} Land in counties ], ], and ] was privately colonised with the king's support.<ref name="Stewart 38" /><ref name="Falls 156-7" /><ref name="Perceval-Maxwell 55" /> | |||

| == Planning the plantation== | |||

| Prior to its conquest in the ] of the 1590s, ] had been the most Gaelic part of Ireland, a province existing largely outside English control. An early attempt at plantation in the 1570s on the east coast of Ulster by ], had failed (See ]). | |||

| Among those involved in planning and overseeing the plantation were King James, the ], ], and the ], ].<ref name="MacRaild Smith 142">{{harvp|MacRaild|Smith|2012|p=142}}: "Advisors to King James VI/I, notably Arthur Chichester, Lord Deputy from 1604, and Sir John Davies, the lawyer, favoured the plantation as a definitive response to the challenges of ruling Ireland. ... Undertakers, servitors and natives were granted large blocks of land as long as they planted English-speaking Protestants".</ref> They saw the plantation as a means of controlling, ],<ref>{{harvp|Lenihan|2007|p=43}}: "According to the Lord Deputy Chichester, the plantation would 'separate the Irish by themselves ... , in heart in tongue and every way else become English"</ref> and "civilising" Ulster.<ref>{{harvp|Bardon|2011|p=214}}: "To King James the Plantation of Ulster would be a civilising enterprise which would 'establish the true religion of Christ among men ... almost lost in superstition'. In short, he intended his grandiose scheme would bring the enlightenment of the Reformation to one of the most remote and benighted provinces in his kingdom. Yet some of the most determined planters were, in fact, Catholics."</ref> The province was almost wholly ], ], and rural and had been the region most resistant to English control. The plantation was also meant to sever the ties of the Gaelic clans of Ulster with those from the ] of Scotland,<ref name="Ellis, p.2962">{{cite book |last=Ellis |first=Steven |title=The Making of the British Isles: The State of Britain and Ireland, 1450-1660 |date=2014 |publisher=Routledge |page=296}}</ref> as it meant a strategic threat to England.<ref name=":1">{{Cite web |title=2. The Plantations: Sowing the seeds of Ireland's religious geographies |url=https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/troubledgeogs/chap2.htm#ulster |access-date=31 December 2024 |website=Troubled Geographies: A Spatial History of Religion and Society in Ireland}}</ref> The ] (or "British tenants")<ref name="Curtis 198">{{harvp|Curtis|2000|p=198}}.</ref>{{sfnp|Moody|Martin|1984|p=190}} were required to be English-speaking, ],<ref name="MacRaild Smith 142" /><ref>{{Cite web |url= https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/planters/es09.shtml |title=BBC History – The Plantation of Ulster – Religion |access-date=25 December 2019 |archive-date=4 December 2019 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20191204114125/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/planters/es09.shtml |url-status=live}}</ref> and loyal to the king. Some of the landlords and settlers, however, were Catholic.<ref>{{harvp|Bardon|2011|pp=ix–x}}: "Many will be surprised that three amongst the most energetic planters were Catholics. Sir Randall MacDonell, Earl of Antrim, ... George Tuchet, 18th Baron Audley, ... Sir George Hamilton of Greenlaw, together with his relatives ... made his well-managed estate in the Strabane area a haven for Scottish Catholics".</ref><ref>{{harvp|Bardon|2011|p=214}}: "The result was that over the ensuing decades many Catholic Scots ... were persuaded to settle in this part of Tyrone ".</ref><ref name="Blaney">{{Cite book |last=Blaney |first=Roger |title=Presbyterians and the Irish Language |publisher=Ulster Historical Foundation |date=2012 |isbn=978-1-908448-55-2 |pages=6–16}}</ref> The Scottish settlers were mostly ] ] and the English settlers were mostly ] ], which their culture differed from ].<ref name="Curtis 198" /> Although some "loyal" natives were granted land, the native Irish reaction to the plantation was generally hostile,<ref>{{Cite web |title=BBC History – The Plantation of Ulster – Reaction of the natives |url= https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/planters/es05.shtml |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20191231190907/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/planters/es05.shtml |archive-date=31 December 2019}}</ref> and native writers lamented what they saw as the decline of Gaelic society and the influx of foreigners.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Horning |first=Audrey |title=Ireland in the Virginian Sea: Colonialism in the British Atlantic |publisher=] |date=2013 |pages=179}}</ref> | |||

| The Nine Years War ended in 1603 with the surrender of the O’Neill and O’Donnell lords to the English crown, following an extremely costly series of campaigns by the English in which they had to counter significant Spanish aid to the Irish. But the situation following the peace was far more propitious for colonisation schemes, and much of the legal groundwork was laid by Sir ], then attorney general of Ireland. | |||

| The Plantation of Ulster was the biggest of the ].<ref>{{Cite web |last=Dorney |first=John |date=2 June 2024 |title=The Plantation of Ulster: A Brief Overview |url=https://www.theirishstory.com/2024/06/02/the-plantation-of-ulster-a-brief-overview/ |access-date=30 December 2024 |website=The Irish Story}}</ref> It led to the founding of many of Ulster's towns and created a lasting ] community in the province with ties to Britain. It also resulted in many of the native Irish nobility losing their land and led to centuries of ] and ] animosity, which at times ], notably in the ] and, more recently, ]. | |||

| The terms of surrender granted to the rebels in 1603 were generous, with the principal condition that lands formerly contested by feudal right and ] be held under English law. However, when ] and other rebel aristocrats left Ireland in the ] in 1607 to seek Spanish help for a new rebellion, Lord Deputy ] seized their lands and prepared to colonise the province in a fairly modest ]. This would have included large grants of land to native Irish lords who had sided with the English during the war — for example ]. However, the plan was interrupted by the rebellion in 1608 of ] of ], a former ally of the English. The rebellion was put down by Wingfield. After O'Doherty's death his lands at ] were granted out by the state, and eventually escheated to the Crown. This episode prompted Chichester to expand his plans to expropriate the legal titles of all native landowners in the province. | |||

| ==Ulster before plantation== | |||

| The Plantation of Ulster was sold to ], king of England, Scotland and Ireland, as a joint ] venture to pacify and civilise Ulster. At least half the settlers would be Scots. Five counties were involved in the official plantation — ], ], ], ] and ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| Before the plantation, ] had been the most ] province of Ireland, as it was the least anglicised and the most independent of English control.{{sfnp|Madden|1857|p=2–5}} The region was almost wholly rural and had few towns or villages.{{sfnp|Falls|1996|pp=11–12}}<ref name="Robinson 28">{{harvp|Robinson|2000|p=28}}.</ref> Throughout the 16th century, Ulster was viewed by the English as being "underpopulated" and undeveloped.{{sfnp|Bardon|2005|p=75}}{{sfnp|Chart|1928|p=18}} The economy of Gaelic Ulster was overwhelmingly based on agriculture, especially cattle-raising. Many of the Gaelic Irish practised "creaghting" or "booleying", a kind of ] whereby some of them moved with their cattle to upland pastures during the summer months and lived in temporary dwellings during that time. This often led outsiders to mistakenly believe the Gaelic Irish were nomadic.<ref>{{harvp|Bardon|2011|p=}}: "The economy was overwhelmingly dependent on agriculture. ... The English consistently underestimated the importance of arable farming in Gaelic Ulster, but there is no doubt that cattle raising was the basis of the rural economy. ... This form of transhumance, known as 'booleying', often led outsiders to conclude mistakenly that the Gaelic Irish lived a nomadic existence."</ref>{{Page needed|date=December 2023}} | |||

| The population of Ulster before the Plantation has been estimated to be around 180,000-200,000.{{sfnp|Kennedy|Miller|Gurrin|2012|pp=58–59}} This was after the destruction caused by the devastating famine and warfare at the end of the Nine Years War. Michael Perceval-Maxwell estimated that by 1600 Ulster's total adult population was only 25,000-40,000.{{sfnp|Perceval-Maxwell|1999|p=17}} The war fought between the native Irish Confederacy and the English Crown undoubtedly contributed to depopulation, with 60,000 reported dead by famine and attacks on the civilian population.{{sfnp|Bardon|2005|pp=76–83}}<ref>{{Cite web |title=BBC History – The Plantation of Ulster – Reaction of the Natives – Professor Nicholas Canny |url= https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/transcripts/es05_t03.shtml |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20210308060729/https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/transcripts/es05_t03.shtml |archive-date=8 March 2021}}</ref> | |||

| The plan for the plantation was determined by two factors. One was the wish to make sure the settlement could not be destroyed by rebellion as the first ] had been. This meant that, rather than settling the planters in isolated pockets of land confiscated from convicted rebels, all of the land would be confiscated and then redistributed to create concentrations of British settlers around new towns and garrisons. What was more, the new landowners were explicitly banned from taking Irish tenants and had to import workers from England and Scotland. The remaining Irish landowners were to be granted one quarter of the land in Ulster. The peasant Irish population was intended to be relocated to live near garrisons and Protestant churches. Moreover, the planters were barred from selling their lands to any Irishman. They were required to build defences against a possible rebellion or invasion. The settlement was to be completed within three years. In this way, it was hoped that a defensible new community composed entirely of loyal British subjects would be created. | |||

| The ] began in the 1540s, during the reign of ] (1509–1547), and concluded in the reign of ] (1558–1603) sixty years later, breaking the power of the semi-independent Irish chieftains.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lecky |first=William Edward |url=https://archive.org/details/historyofireland01leckuoft/mode/2up |title=A History of Ireland in the Eighteenth Century |publisher=] |orig-date=1892 |date=1913 |volume=I |pages=4–6 |author-link=William Edward Hartpole Lecky}}</ref> As part of the conquest, ] (colonial settlements) were established in Queen's County and King's County (] and ]) in the 1550s as well as ] in the 1580s, and in 1568 Warham St Leger and Richard Grenville established Joint stock/Cooperate colonies in Cork, although these were not very successful.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Rowse |first=A. L. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=w8f3WXpsJGoC&dq=1568+Warham+St+Leger+and+Richard+Grenville,+cork&pg=PT38 |title=Sir Richard Grenville of the Revenge |date=2013-02-21 |publisher=Faber & Faber |isbn=978-0-571-30043-3 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The second major influence on the Plantation was the negotiation among various interest groups on the British side. The principal landowners were to be '''Undertakers''', wealthy men from England and Scotland who undertook to import tenants from their own estates. They were granted around 3000 acres (12 km²) each, on condition that they settle a minimum of 48 adult males (including at least 20 families), who had to be ] and Protestant. However, veterans of the ] (known as '''Servitors''') led by Arthur Chichester successfully lobbied to be rewarded with land grants of their own. Since these former officers did not have enough private capital to fund the colonisation, their involvement was subsidised by the twelve great guilds. ] from the ] were coerced into investing in the project. The City of London guilds were also granted land on the west bank of the ] to build their own city (], near the older ]) as well as lands in ]. The final major recipient of lands was the Protestant ], which was granted all the churches and lands previously owned by the ] Church. The British government intended that clerics from England and ] would convert the native population to ]. | |||

| There was also the plantation of Munster and Leinster. | |||

| In the 1570s, Elizabeth I authorised a privately funded ], led by ] and ]. This was a failure and sparked violent conflict with the local Irish lord, in which Lord Deputy Essex ] many of the lord of ]'s kin.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Heffernan |first=David |url= https://www.historyireland.com/volume-27/essexs-enterprise/ |url-status=live |title=Essex's 'Enterprise' |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20200927143113/https://www.historyireland.com/volume-27/essexs-enterprise/ |archive-date=27 September 2020 |journal=] |volume=27 |issue=2 |date=March–April 2019}}</ref> | |||

| == Plantation in operation == | |||

| The plantation was a mixed success. At around the time the Plantation of Ulster was planned, the ] at ] in 1607 started. The London guilds planning to fund the Plantation of Ulster switched and backed the ] instead. Many British Protestant settlers went to ] or ] in the New World rather than to Ulster. By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male British settlers in Ulster, which meant that the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000. They formed local majorities of the population in the ] and ] valleys (around modern Derry and east ]), in north ] and in east ]. Moreover, there had also been substantial settlement on officially unplanted lands in south Antrim and north Down, sponsored by the Scottish landowner James Hamilton. What was more, the settler population grew rapidly, as just under half of the planters were women — a very high ratio compared to contemporary Spanish settlement in ] or English settlement in ] and ]. | |||

| In the Nine Years' War of 1594–1603, an alliance of northern Gaelic chieftains—led by ] of ], ] of ], and ] of ]—resisted the imposition of English government in Ulster and sought to affirm their own control. Following an extremely costly series of campaigns by the English the war ended in 1603 with the ].{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=18–23}} The terms of surrender granted to what remained of O'Neill's forces were considered generous at the time.{{sfnp|Lennon|1995|p=301–302}} | |||

| Other aspects of the original plan proved unrealistic, however. Because of political uncertainty in Ireland and the risk of attack by the dispossessed Irish, the undertakers had difficulty attracting settlers (especially from England). They were forced to keep Irish tenants, thus destroying the original plan of segregation between settlers and natives. As a result, the Irish population was neither removed nor Anglicised. In practice, the settlers did not stay on bad land, but clustered around towns and the best land. This meant that, contrary to the terms of the plantation, many British landowners had to take Irish tenants. In 1609, Chichester had 1300 former Irish soldiers deported from Ulster to serve in the ]. The province remained plagued with Irish natives, known as "wood-kerne", who were angered as their land was taken away and attacked settlers. | |||

| After the Treaty of Mellifont, the northern chieftains attempted to consolidate their positions, whilst some within the ] attempted to undermine them. In 1607, O'Neill and his primary allies left Ireland to seek Spanish help for a new rebellion to restore their privileges, in what became known as the ]. King James issued a proclamation declaring their action to be ], paving the way for the ] of their lands and titles.<ref>{{Citation |title=A Proclamation touching the Earles of Tyrone and Tyrconnell |date=15 November 1607 |url=https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E600001-002/text001.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181231230742/https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E600001-002/text001.html |archive-date=31 December 2018 |url-status=live |place=London |publisher=Robert Barker}}</ref> | |||

| The attempted conversion of the Irish to Protestantism had mixed effect, if only because the clerics imported were usually all English speakers, whereas the native population were usually ] ] speakers. However, ministers chosen to serve in the plantation were required to take a course in the Irish language before ordination, and nearly 10% of those who took up their preferments spoke it fluently{{fn|2}}. Of those Catholics who did convert to Protestantism, many made their choice for social and political reasons{{fn|3}}. | |||

| ==Planning the plantation== | |||

| ==Wars of the Three Kingdoms and Ulster Plantation== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{further|]}} | |||

| A colonization of Ulster had been proposed since the end of the ]. The original proposals were smaller, involving planting settlers around key military posts and on church land, and would have included large land grants to native Irish lords who sided with the English during the war, such as ]. However, in 1608 Sir ] of ] launched ], capturing and ]. The brief rebellion was ended by Sir ] at the ]. The rebellion prompted ], the ], to plan a much bigger plantation and to ] the legal titles of all native landowners in the province.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=44–45}} ], the ], used the law as a tool of conquest and colonization. Before the Flight of the Earls, the English administration had sought to minimise the personal estates of the chieftains, but now they treated the chieftains as sole owners of their whole territories, so that all the land could be confiscated. Most of this land was deemed to be forfeited (or ]ed) to the Crown because the chieftains were declared to be ].<ref name=":4">{{Cite book |last=Connolly |first=S. J. |url=https://archive.org/details/contestedislandi0000conn |title=Contested Island: Ireland 1460-1630 |publisher=] |date=2007 |pages=296 |isbn=978-0-19-956371-5 |author-link=Sean Connolly (academic) |url-access=registration}}</ref> English judges had also ] that titles to land held under ], the native Irish custom of inheriting land, had no standing under English law.<ref name=":4" /> Davies used this as a means to confiscate land, when other means failed.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Pawlisch |first=Hans Scott |url=https://archive.org/details/sirjohndaviescon0000pawl |title=Sir John Davies and the conquest of Ireland: a study in legal imperialism |publisher=] |date=1985 |pages=73–80 |isbn=978-0-521-25328-4 |url-access=registration}}</ref> | |||

| In the 1640s, the Ulster Plantation was thrown into turmoil by ]. The wars saw Irish rebellion against the planters, twelve years of bloody war, and ultimately the re-conquest of the province by the English parliamentary ] that confirmed English and Protestant dominance in the province. | |||

| The Plantation of Ulster was presented to ] as a joint "British", or English and Scottish, venture to 'pacify' and 'civilise' Ulster, with half the settlers to be from one country. James had been King of Scotland before he also became King of England and wanted to reward his Scottish subjects with land in Ulster to assure them they were not being neglected now that he had moved his court to London. Long-standing contacts between Ulster and the west of Scotland meant that Scottish participation was a practical necessity.{{sfnp|Canny|2001|pp=196–198}} James saw the ] as barbarous and rebellious,<ref name=":0">{{harvp|Ellis|2007|p=296}}.</ref> and believed Gaelic culture should be wiped out.<ref>{{cite book |last=Szasz |first=Margaret |date=2007 |title=Scottish Highlanders and Native Americans |publisher=] |page=48}}</ref> For centuries, Scottish Gaelic mercenaries called ] ({{lang|ga|gallóglaigh}}) had been migrating to Ireland to serve under the Irish chiefs. Another goal of the plantation was to sever the ties of the Gaelic clans of Ulster with those from the Highlands of Scotland,<ref name="Ellis, p.2962" /> as these ties posed a strategic threat to England.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

| After 1630, Scottish migration to Ireland waned for a decade. In the 1630s many Scots went home after ] forced the Prayer Book of the ] on the ], thus compelling the ] Scots to change their form of worship. In 1638 Scots in Ulster had to take ']' binding them on against taking up arms against the King. This occurred against the background of the ] in Scotland — a Presbyterian uprising against King Charles I. The King subsequently had an army, largely composed of Irish Catholics, raised and sent to Ulster in preparation to invade Scotland. This prompted the English and Scottish Parliaments to threaten to invade Ireland and subdue the Catholics there. This in turn caused Gaelic Irish gentry in Ulster, led by ] and Rory O'More, to plan a rebellion aimed at taking over the administration in Ireland to pre-empt an anti-Catholic invasion. | |||

| Six counties were involved in the official plantation{{spaced ndash}}], ], ], ], ] and ]. In the two officially unplanted counties of ] and ], substantial Presbyterian Scots settlement had been underway since 1606.<ref name="Stewart 38" /> | |||

| On October 23rd, 1641, the native Gaelic Ulster Catholics broke out in armed rebellion — the ]. The natives mobilised in the rebellion turned on the British planter population, massacring about 4000 settlers and expelling about 12,000 more. The initial leader of the rebellion, ], had actually been a beneficiary of the Plantation land grants, but most of his supporters' families had been dispossessed and were undoubtedly motivated by the desire to recover their ancestral lands. Many planter survivors rushed to the seaports and went back to Scotland or England. This massacre and the reprisals which followed permanently soured the relationship between planter and native communities. | |||

| The plan for the plantation was determined by two factors. One was the wish to make sure the settlement could not be destroyed by rebellion as the first ] had been in the Nine Years' War. This meant that, rather than settling the planters in isolated pockets of land confiscated from the Irish, all of the land would be confiscated and then redistributed to create concentrations of British settlers around new towns and garrisons.{{sfnp|Canny|2001|pp=189–200}} | |||

| In the summer of 1642, ten thousand Scottish ] soldiers, including some ], arrived to quell the Irish rebellion. In revenge for the massacres of Protestants, the Scots committed many atrocities against the Catholic population. However, civil war in England and Scotland (the ]) broke out before the rebellion could be put down. Based in ], the Scottish army fought in Ireland until 1650 in the ]. Many stayed on in Ireland afterward with the permission of the Cromwellian authorities. In the northwest of Ulster, the Planters around ] and east ] organised the '''Lagan Army''' in self defence. The Protestant forces fought an inconclusive war with the Ulster Catholics led by ]. All sides committed atrocities against civilians in this war, exacerbating the population displacement begun by the Plantation. In addition to fighting the native Ulster Catholics, the British settlers fought each other in 1648-49 over the issues of the ]. The Scottish Presbyterian army sided with the King and the Lagan Army sided with the English Parliament. In 1649-50, the ], along with some of the British planter Protestants under Charles Coote, defeated both the Scottish forces in Ulster and the native Ulster Catholics. | |||

| What was more, the new landowners were explicitly banned from taking Irish tenants and had to import workers from England and Scotland. The remaining Irish landowners were to be granted one quarter of the land in Ulster. The peasant Irish population was intended to be relocated to live near garrisons and Protestant churches. Moreover, the planters were barred from selling their lands to any Irishman and were required to build defences against any possible rebellion or invasion. The settlement was to be completed within three years. In this way, it was hoped that a defensible new community composed entirely of loyal British subjects would be created.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=48–49}} | |||

| As a result, the English Parliamentarians or Cromwellians (after ]) were generally hostile to Scottish Presbyterians after they ] from the Catholic ] in 1649-53. The main beneficiaries of the postwar ] in Ulster were English Protestants like Sir Charles Coote, who had taken the Parliament's side over the King or the Scottish ] in the Civil Wars. The Wars eliminated the last major Catholic landowners in Ulster. | |||

| The second major influence on the Plantation was the negotiation among various interest groups on the British side. The principal landowners were to be "Undertakers", wealthy men from England and Scotland who undertook to import tenants from their own estates. They were granted around 3000 acres (12 km<sup>2</sup>) each, on condition that they settle a minimum of 48 adult males (including at least 20 families), who had to be English-speaking and Protestant. Veterans of the Nine Years' War (known as "Servitors") led by ] successfully lobbied to be rewarded with land grants of their own. | |||

| ==Ulster Plantation and the Scottish border problem== | |||

| Most of the Scottish planters came from southwest Scotland, but many also came from the unstable regions along the border with England. The plan was that moving Borderers (see ]) to Ireland (particularly to ]) would both solve the Border problem and tie down Ulster. This was of particular concern to ] when he became King of England, since he knew Scottish instability could jeopardise his chances of ruling both kingdoms effectively. | |||

| Since these former officers did not have enough private capital to fund the colonisation, their involvement was subsidised by the twelve great guilds. ] from the ] were coerced into investing in the project, as were City of London guilds which were granted land on the west bank of the ], to build their own city on the site of ] (renamed Londonderry after them) as well as lands in County Coleraine. They were known jointly as ]. The final major recipient of lands was the Protestant ], which was granted all the churches and lands previously owned by the Roman Catholic Church. The British government intended that clerics from England and ] would convert the native population to ].{{sfnp|Canny|2001|p=202}} | |||

| Another wave of Scottish immigration to Ulster took place in the 1690s, when tens of thousands of Scots fled a famine in the borders region. It was at this point that Scottish Presbyterians became the majority community in the province. These planters are often referred to as ]. Despite the fact that Scottish Presbyterians strongly supported the ]s in the ] in the 1690s, they were excluded from power in the postwar settlement by the ] ]. | |||

| ==Implementing the plantation== | |||

| As a result, the descendants of the ] planters played a major part in the ] against ] rule. Not all of the Scottish planters were Lowlanders, however, and there is also evidence of Scots from the southwest Highlands settling in Ulster. Many of these would have been ] speakers {{Fact|date=September 2008}} like the native Ulster Catholics. | |||

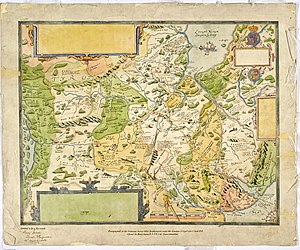

| ] | |||

| Since 1606, there had been substantial lowland Scots settlement on disinhabited land in north Down, led by ] and ].{{sfnp|Perceval-Maxwell|1999|p=55}} In 1607, ] settled 300 Presbyterian Scots families on his land in Antrim.{{sfnp|Elliott|2001|p=88}} | |||

| From 1609 onwards, British Protestant immigrants arrived in Ulster through direct importation by Undertakers to their estates and also by a spread to unpopulated areas, through ports such as Derry and Carrickfergus. In addition, there was much internal movement of settlers who did not like the original land allotted to them.{{sfnp|Robinson|2000|pp=118–119, 125–128}} Some planters settled on uninhabited and unexploited land, often building up their farms and homes on overgrown terrain that has been variously described as "wilderness" and "virgin" ground.<ref>{{harvp|Stewart|1989|pp=40–41}}. Raymond Gillespie: {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210308142651/https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/transcripts/es05_t02.shtml |date=8 March 2021}}, BBC.<!--accessed May 13, 2009--> {{harvp|Bardon|2005|p=178, 314}}. {{harvp|Perceval-Maxwell|1999|pp=29, 132}}. {{harvp|Hanna|1902|p=182}}. {{harvp|Falls|1996|p=201}}.</ref> In 1612, ] received a grant of land to establish a settler town at ].<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.dib.ie/biography/cole-sir-william-a1830 |title=Cole, Sir William |last=Clavin |first=Terry |date=October 2009 |website=Dictionary of Irish Biography |access-date=19 February 2023}}</ref> | |||

| == Legacy == | |||

| {{further|]}} | |||

| By 1922, Unionists were in the majority in four of the nine counties of Ulster, although only two of these counties were involved in the Ulster Plantation. Antrim and Down counties had been settled earlier by Protestants. Following the Anglo-Irish settlement of 1921, these four counties, and two others in which Protestants formed a sizeable minority, remained in the United Kingdom to form ]. {{cn}} | |||

| By 1622, a survey found that there were 6,402 British adult males on Plantation lands, of whom 3,100 were English and 3,700 Scottish – indicating a total adult planter population of around 12,000. However, another 4,000 Scottish adult males had settled in unplanted Antrim and Down, giving a total settler population of about 19,000.<ref>All previous figures from: {{harvp|Canny|2001|p=211}}.</ref> | |||

| T. A. Jackson contends that it is a “complete fallacy” to point to the Plantation as the origin of modern Northern Ireland. He notes that four out of the six counties planted were never part of “Orange” Ulster until the Partition of Ireland. In addition, he writes that the two mainly “Protestant” counties, Antrim and Down, were never part of the plantation, elements “which destroy the myth.” <ref>T. A. Jackson, ''Ireland Her Own'', Lawrence & Wishart (London) 1991 (New Edition), ISBN 0 85315 735 9, pg.52</ref> | |||

| Despite the fact that the Plantation had decreed that the Irish population be displaced, this did not generally happen in practice. Firstly, some 300 native landowners who had taken the English side in the Nine Years' War were rewarded with land grants.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|p=46}} Secondly, the majority of the Gaelic Irish remained in their native areas, but were now only allowed worse land than before the plantation. They usually lived close to and even in the same townlands as the settlers and the land they had farmed previously.<ref>{{harvp|Elliott|2002}}. {{harvp|Stewart|1989|pp=24–25}}. {{harvp|Bardon|2005|p=131}}. {{harvp|Falls|1996|p=221}}. {{harvp|Perceval-Maxwell|1999|p=66}}. {{harvp|Elliott|2001|p=88}}. {{harvp|Robinson|2000|p=100}}</ref> The main reason for this was that Undertakers could not import enough English or Scottish tenants to fill their agricultural workforce and had to fall back on Irish tenants.{{sfnp|Canny|2001|pp=233–235}} However, in a few heavily populated lowland areas (such as parts of north Armagh) it is likely that some population displacement occurred.{{sfnp|Elliott|2001|p=93}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| * CANNY, Nicholas P, Making Ireland British 1580–1650, Oxford: Oxford University Press 2001. ISBN 0-19-820091-9 | |||

| * LENNON, Colm, Sixteenth Century Ireland — The Incomplete Conquest, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1994. ISBN 0-312-12462-7 | |||

| * LENIHAN, Padraig, Confederate Catholics at War, Cork: Cork University Press 2000. | |||

| * SCOT-WHEELER, James, Cromwell in Ireland, New York 1999. | |||

| * Michael Sletcher, ‘Scotch-Irish’, in Stanley I. Kutler, ed., ''Dictionary of American History''. 10 vols. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002. | |||

| *{{1911}} ("Plantation" article) | |||

| However, the Plantation remained threatened by the attacks of bandits, known as "]", who were often Irish soldiers or dispossessed landowners. In 1609, Chichester had 1,300 former Gaelic soldiers deported from Ulster to serve in the ].{{sfnp|Elliott|2001|p=119}}{{sfnp|Canny|2001|pp=205–206}} As a result, military garrisons were established across Ulster and many of the Plantation towns, notably Derry, were fortified. The settlers were also required to maintain arms and attend an annual military 'muster'.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=52–53}} | |||

| ==Note== | |||

| {{fnb|1}} As part of the Plantation plan, the County of Coleraine ceased to exist. With parts of Donegal, Tyrone and ], it became ] to recognise the ] that funded it. ''For further details, see ].'' | |||

| There had been very few towns in Ulster before the Plantation.{{sfnp|Falls|1996|pp=11}}<ref name="Robinson 28" /> Most modern towns in the province can date their origins back to this period. Plantation towns generally have a single broad main street ending in a square in a design often known as a "diamond",{{sfnp|Robinson|2000|pp=169, 170}} which can be seen in communities like ]. | |||

| {{fnb|2}} Padraig O Snodaigh, ''Hidden Ulster, Protestants and the Irish language''. | |||

| ===Failures=== | |||

| {{fnb|3}}Marianne Elliott, ''The Catholics of Ulster: A History''. | |||

| The plantation was a mixed success from the point of view of the settlers. About the time the Plantation of Ulster was planned, the ] at ] in 1607 started. The London guilds planning to fund the Plantation of Ulster switched and backed the ] instead. Many British Protestant settlers went to ] or ] in America rather than to Ulster. | |||

| By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male British settlers in Ulster, which meant that the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000. They formed local majorities of the population in the ] and ] valleys (around modern County Londonderry and east Donegal), in north Armagh and in east Tyrone. Moreover, the unofficial settlements in Antrim and Down were thriving.{{sfnp|Bardon|2011|p=123}} The settler population grew rapidly, as just under half of the planters were women. | |||

| The attempted conversion of the Irish to Protestantism was generally a failure. One problem was language difference. The Protestant clerics imported were usually all ] English speakers, whereas the native population were usually monoglot Irish speakers. However, ministers chosen to serve in the plantation were required to take a course in the Irish language before ordination, and nearly 10% of those who took up their preferments spoke it fluently.<ref>Padraig Ó Snodaigh.</ref>{{Page needed|date=September 2010}} Nevertheless, conversion was rare, despite the fact that, after 1621, Gaelic Irish natives could be officially classed as British if they converted to Protestantism.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=48–49}} Of those Catholics who did convert to Protestantism, many made their choice for social and political reasons.{{sfnp|Elliott|2001|p=}}{{Page needed|date=September 2010}} | |||

| The reaction of the native Irish to the plantation was generally hostile. Chichester wrote in 1610 that the native Irish in Ulster were "generally discontented, and repine greatly at their fortunes, and the small quantity of land left to them". That same year, English army officer ] wrote that "there is not a more discontented people in Christendom" than the Ulster Irish.<ref>Rafferty, Oliver. ''Catholicism in Ulster, 1603–1983''. University of South Carolina Press, 1994. p.12</ref> Irish Gaelic writers bewailed the plantation. In an entry for the year 1608, the '']'' states that the land was "taken from the Irish" and given "to foreign tribes", and that Irish chiefs were "banished into other countries where most of them died". Likewise, an early 17th-century poem by the Irish ] ] laments the plantation, the displacement of the native Irish, and the decline of Gaelic culture.<ref>Gillespie, Raymond. "Gaelic Catholicism and the Plantation of Ulster", in ''Irish Catholic Identities'', edited by Oliver Rafferty. Oxford University Press, 2015. p.124</ref> It asks "Where have the Gaels gone?", adding "We have in their stead an arrogant, impure crowd, of foreigners' blood".<ref>{{Cite web |title=BBC - History - Wars and Conflicts - Plantation of Ulster - Bardic Poetry - A Poem on the Downfall of the Gaoidhil |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/bardic/poem08.shtml |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201112012627/https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/bardic/poem08.shtml |archive-date=12 November 2020 |access-date=10 December 2023 |website=BBC}}</ref> | |||

| Historian ] suggests that Irish hostility to the plantation may have been muted in the early years, as there were much fewer settlers arriving than expected. Bartlett writes that a hatred for the planters grew with the influx of settlers from the 1620s, and the increasing marginalization of the Irish.<ref>Bartlett, Thomas. ''Ireland: A History''. Cambridge University Press, 2010. p.104</ref> Historian Gerard Farrell writes that the plantation stoked a "smoldering resentment" in the Irish, among whom "a widespread perception persisted that they and the generation before them had been unfairly dispossessed of their lands by force and legal chicanery". Petty violence and sabotage against the planters was rife, and many Irish came to identify with the wood-kern who attacked settlements and ambushed settlers. Ferrell suggests it took many years for an Irish uprising to happen because there was depopulation, because many native leaders had been removed, and those who remained only belatedly realised the threat of the plantation.<ref>Farrell, Gerard. ''The 'Mere Irish' and the Colonisation of Ulster, 1570–1641''. Springer, 2017, pp. 277–279</ref> | |||

| ==Wars of the Three Kingdoms== | |||

| {{Further|Wars of the Three Kingdoms|Irish Confederate Wars}} | |||

| By the 1630s it is suggested that the plantation was settling down with "tacit religious tolerance", and in every county Old Irish were serving as royal officials and members of the Irish Parliament.{{sfnp|Elliott|2001|p=97}} However, in the 1640s, the Ulster Plantation was thrown into turmoil by ]. The wars saw Irish rebellion against the planters, twelve years of bloody war, and ultimately the re-conquest of the province by the English parliamentary ] that confirmed English and Protestant dominance in the province.{{sfnp|Canny|2001|pp=577–578}} | |||

| After 1630, Scottish migration to Ireland waned for a decade. In the 1630s, Presbyterians in Scotland ] against Charles I for trying to impose ]. The same was attempted in Ireland, where most Scots colonists were Presbyterian. A large number of them returned to Scotland as a result. Charles I subsequently raised an army largely composed of Irish Catholics, and sent them to Ulster in preparation to invade Scotland. The English and Scottish parliaments then threatened to attack this army. In the midst of this, Gaelic Irish landowners in Ulster, led by ] and ], planned a rebellion to take over the administration in Ireland.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=91–92}} | |||

| On 23 October 1641, the Ulster Catholics ]. The mobilised natives turned on the British colonists, massacring about 4,000 and expelling about 8,000 more. ] believes that "1641 destroyed the Ulster Plantation as a mixed settlement".{{sfnp|Elliott|2001|p=102}} The initial leader of the rebellion, Felim O'Neill, had actually been a beneficiary of the Plantation land grants. Most of his supporters' families had been dispossessed and were likely motivated by the desire to recover their ancestral lands. Many colonists who survived rushed to the seaports and went back to Great Britain.<ref>MacCuarta, Brian, ''Age of Atrocity'', p. 155; {{harvp|Canny|2001|p=177}}.</ref> | |||

| The massacres made a lasting impression on psyche of the Ulster Protestant population. ] states that "The fear which it inspired survives in the Protestant subconscious as the memory of the Penal Laws or the Famine persists in the Catholic."{{sfnp|Stewart|1989|p=49}} He also believed that "Here, if anywhere, the mentality of siege was born, as the warning bonfires blazed from hilltop to hilltop, and the beating drums summoned men to the defence of castles and walled towns crowded with refugees."{{sfnp|Stewart|1989|p=52}} | |||

| In the summer of 1642, the ] sent some 10,000 soldiers to quell the Irish rebellion. In revenge for the massacres of Scottish colonists, the army committed many atrocities against the Catholic population. Based in ], the Scottish army fought against the rebels until 1650, although much of the army was destroyed by the Irish forces at the ] in 1646. In the northwest of Ulster, the colonists around Derry and east Donegal organised the ] in self-defence. The British forces fought an inconclusive war with the Ulster Irish led by ]. All sides committed atrocities against civilians in this war, exacerbating the population displacement begun by the Plantation.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|p=111}} | |||

| In addition to fighting the Ulster Irish, the British settlers fought each other in 1648–49 over the issues of the ]. The Scottish Presbyterian army sided with the King and the Laggan Army sided with the English Parliament. In 1649–50, the New Model Army, along with some of the British colonists under ], defeated both the Scottish forces and the Ulster Irish.{{sfnp|Ó Siochrú|2008|pp=99, 128, 144}} | |||

| As a result, the ] (or ]ians) were generally hostile to Scottish Presbyterians after they ] from the Catholic ] in 1649–53. The main beneficiaries of the postwar ] were English Protestants like Sir Charles Coote, who had taken the Parliament's side over the King or the Scottish Presbyterians. The Wars eliminated the last major Catholic landowners in Ulster.{{sfnp|Lenihan|2007|pp=136–137}} | |||

| ==Continued migration from Scotland to Ulster== | |||

| Most Scottish planters came from southwest Scotland, but many also came from the unstable regions along the border with England. The plan was that moving Borderers (see ]) to Ireland (particularly to County Fermanagh)<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Bell |first=Robert |date=1994 |title='Sheep stealers from the north of England': the Riding Clans in Ulster |url=https://www.historyireland.com/sheep-stealers-from-the-north-of-england-the-riding-clans-in-ulster-by-robert-bell/ |journal=] |volume=2 |issue=4 |access-date=9 August 2024}}</ref> would both solve the Border problem and tie down Ulster. This was of particular concern to ] when he became King of England, since he knew Scottish instability could jeopardise his chances of ruling both kingdoms effectively. | |||

| Another wave of Scottish immigration to Ulster took place in the 1690s, when tens of thousands of Scots fled ] in the border region of Scotland. It was at this point that Scottish Presbyterians became the majority community in the province. Whereas in the 1660s, they made up some 20% of Ulster's population (though 60% of its British population) by 1720 they were an absolute majority in Ulster, with up to 50,000 having arrived during the period 1690–1710.{{sfnp|Cullen|2010|pp=176–179}} There was continuing English migration throughout this period, particularly the 1650s and 1680s, notably amongst these settlers were the Quakers from the North of England, who contributed greatly to the cultivation of flax and linen. In total, during the half century between 1650 and 1700, 100,000 British settlers migrated to Ulster, just over half of which were English.{{sfnp|Kennedy|Ollerenshaw|2012|p=143}} | |||

| Despite the fact that Scottish Presbyterians strongly supported the ]s in the ] in the 1690s, they were excluded from power in the postwar settlement by the ] ]. During the 18th century, rising Scots resentment over religious, political and economic issues fueled their emigration to the American colonies, beginning in 1717 and continuing up to the 1770s. Scots-Irish from Ulster and Scotland and British from the borders region comprised the most numerous group of immigrants from Great Britain and Ireland to the colonies in the years before the ]. An estimated 150,000 left northern Ireland. They settled first mostly in Pennsylvania and western Virginia, from where they moved southwest into the backcountry of the ], the ] and the ].<ref>], '']'', ], 1989, pp. 608–611.</ref> | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

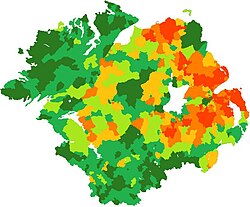

| ]) and 2006 (]).<br />0–10% dark orange, 10–30% mid orange,<br />30–50% light orange, 50–70% light green,<br />70–90% mid green, 90–100% dark green]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The legacy of the Plantation remains disputed. According to one interpretation, it created a society segregated between native Catholics and settler Protestants in Ulster and created a Protestant and British concentration in north-east Ireland. This argument therefore sees the Plantation as one of the long-term causes of the ] in 1921, as the north-east remained as part of the United Kingdom in ].<ref>{{cite journal |url= https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/LON/Volume%2026/v26.pdf#page=9 |title=Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland, signed at London, 6 December 1921 |journal=League of Nations Treaty Series |volume=26 |pages=9–19 |number=626 |access-date=14 June 2020 |archive-date=17 November 2015 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20151117023808/https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/LON/Volume%2026/v26.pdf#page=9 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The densest Protestant settlement took place in the eastern counties of Antrim and Down, which were not part of the Plantation, whereas Donegal, in the west, was planted but did not become part of Northern Ireland.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Interview with Dr. John McCavitt, 'Ulster Plantation' |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/talkni/ask_ulster_plantation.shtml |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121113191530/http://www.bbc.co.uk/northernireland/talkni/ask_ulster_plantation.shtml |archive-date=13 November 2012 |access-date=10 December 2023 |website=BBC}}</ref> | |||

| Therefore, it is also argued that the Plantation itself was less important in the distinctiveness of the north-east of Ireland than natural population flow between Ulster and Scotland. ], a protestant from Belfast, concluded: "The distinctive Ulster-Scottish culture, isolated from the mainstream of Catholic and Gaelic culture, would appear to have been created not by the specific and artificial plantation of the early seventeenth century, but by the continuous natural influx of Scottish settlers both before and after that episode ...."{{sfnp|Stewart|1989|p=39}} | |||

| The Plantation of Ulster is also widely seen as the origin of mutually antagonistic Catholic/Irish and Protestant/British identities in Ulster. ], an expert on the ], has written that: "not all of those of British background in Ireland owe their Irish residence to the Plantations ... yet the Plantation did produce a large British/English interest in Ireland, a significant body of Irish Protestants who were tied through religion and politics to English power."{{sfnp|English|2006|p=59}} | |||

| Genetic analysis has revealed that, "The distribution in Northern Ireland mirrors the distributions of the Plantations of Ireland throughout the 17th century. Thus the cluster will have experienced some genetic isolation by religion from adjacent Irish populations in the intervening centuries."<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Gilbert | first1 = Edmund | last2 = O'Reilly | first2 = Seamus | last3 = Merrigan | first3 = Michael | display-authors = etal | title = The genetic landscape of Scotland and the Isles | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 116 | issue = 38 | publisher = National Academy of Sciences | location = Washington, D.C. | date = September 3, 2019 | pages = 19064–19070 | language = English | issn = 1091-6490 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.1904761116 | doi-access = free | pmid = 31481615 | bibcode = 2019PNAS..11619064G | pmc = 6754546 }}</ref> | |||

| The settlers also left a legacy in terms of language. The strong ] originated through the speech of Lowland Scots settlers evolving and being influenced by both ] dialect and the ].{{sfnp|Macafee|1996|p=xi}} Seventeenth-century English settlers also contributed colloquial words that are still in current use in Ulster.{{sfnp|Falls|1996|pp=231–233}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{clear}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| {{Refbegin|30em}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bardon |first=Jonathan |author-link=Jonathan Bardon |title=A History of Ulster |edition=New Updated |location=Belfast |publisher=] |orig-date=1992 |date=2005 |isbn=978-0-85640-764-2 |url= https://archive.org/details/historyofulster00jona |via=Internet Archive |url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Bardon |first=Jonathan |author-link=Jonathan Bardon |title=The Plantation of Ulster |date=2011 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-7171-4738-0}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Canny |first=Nicholas |author-link=Nicholas Canny |title=Making Ireland British, 1580–1650 |date=2001 |publisher=] |isbn=978-0-19-820091-8 |url= https://archive.org/details/makingirelandbri00cann |via=Internet Archive |url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Chart |first=David Alfred |title=A History of Northern Ireland |date=1928 |publisher=Educational Company of Ireland}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Cullen |first=Karen J. |title=Famine in Scotland: The 'Ill Years' of the 1690s |date=2010 |series="Scottish Historical Review Monographs" series |publisher=] |jstor=10.3366/j.ctt1r279x |isbn=978-0-7486-4184-0 |url= https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3366/j.ctt1r279x |url-access=subscription}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Curtis |first=Edmund |title=A History of Ireland: From Earliest Times to 1922 |edition=6th |date=2000 |orig-date=1936 |publisher=] |isbn=0-415-27949-6}} A newer edition (8th, 2002) is available. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Elliott |first=Marianne |author-link=Marianne Elliott (historian) |title=The Catholics of Ulster: A History |date=2001 |location=New York |publisher=]}} | |||

| * {{cite web |last=Elliott |first=Marianne |author-link=Marianne Elliott (historian) |url= https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/perspective/pp03.shtml |title=Personal Perspective |date=20 June 2002<!--Date was hidden in the page source.--> |work=Wars & Conflict: The Plantation of Ulster |publisher=] |access-date=13 May 2009}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ellis |first=Steven |title= The Making of the British Isles: The State of Britain and Ireland, 1450-1660 |date=2007 |publisher=Routledge}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=English |first=Richard |author-link=Richard English |title=Irish Freedom: The History of Nationalism in Ireland |date=2006 |publisher=] |location=London}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Falls |first=Cyril |author-link=Cyril Falls |title=The Birth of Ulster |location=London |publisher=] |date=1996 |isbn=978-0-09-476610-5 |orig-date=1936|url= https://archive.org/details/birthofulster0000fall |via=Internet Archive |url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Hanna |first=Charles A. |title=The Scotch-Irish: Or, The Scot in North Britain, North Ireland, and North America |date=1902 |publisher=]}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Jackson |first1=T.A. |author-link=Thomas A. Jackson |title=Ireland Her Own: An Outline History of the Irish Struggle for National Freedom and Independence |date=1973 |orig-date=1947 |publisher=] |location=New York |url=https://archive.org/details/irelandherown/mode/2up|via=Internet Archive }} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Lenihan |first=Pádraig |title=Consolidating Conquest: Ireland 1603–1727 |location=Harlow, Essex |publisher=] / ] |date=2007 |isbn=9780582772175}} Various newer versions exist but appear to be reprintings not revised editions. | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Lennon |first=Colm |title=Sixteenth-Century Ireland: The Incomplete Conquest |date=1995 |orig-date=1994 |publisher=] |location=New York |isbn=978-0-312-12462-5 |url=https://archive.org/details/sixteenthcentury0000lenn |via=Internet Archive |url-access=registration}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |editor1-last=Kennedy |editor1-first=Liam |editor2-last=Ollerenshaw |editor2-first=Philip |title=Ulster Since 1600: Politics, Economy, and Society |date=2012<!--Amazon & OUP site says 2012, a different Oxford site says 2013, biblio databases range from 2012 to 2014, but if Amz was selling it by 2012, use 2012.--> |publisher=] |isbn=9780199583119}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Kennedy |first1=Liam |author1-link=Liam Kennedy (historian) |last2=Miller |first2=Kerby A. |author2-link=Kerby A. Miller |last3=Gurrin |first3=Brian |chapter=Chapter 4: People and population change, 1600–1914 |date=2012<!--See main cite above for note about date.--> |editor1-last=Kennedy |editor1-first=Liam |editor2-last=Ollerenshaw |editor2-first=Philip |title=Ulster Since 1600: Politics, Economy, and Society |publisher=] |isbn=9780199583119}} | |||

| * {{cite book |editor-last=Macafee |editor-first=Caroline I. |title=Concise Ulster Dictionary |date=1996 |publisher=] |isbn=9780198600596}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last1=MacRaild |first1=Donald M. |last2=Smith |first2=Malcolm<!--Not a Malcolm Smith we have an article on.--> |contribution=Migration and Emigration, 1600–1945 |date=2012<!--See main cite above for note about date.--> |editor1-last=Kennedy |editor1-first=Liam |editor1-link=Liam Kennedy (historian) |editor-last2=Ollerenshaw |editor-first2=Philip |title=Ulster Since 1600: Politics, Economy, and Society |publisher=] |isbn=9780199583119}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Madden |first=Richard Robert |author-link=Richard Robert Madden |title=The United Irishmen, Their Lives and Times |volume=I |edition=1st Series, 2nd |date=1857 |orig-date=1846 |publisher=] |location=Dublin |pages=2–5 |url= https://archive.org/details/s1unitedirishmen01madduoft/ |via=Internet Archive}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |editor1-last=Moody |editor1-first=T. W. |editor1-link=Theodore William Moody |editor2-last=Martin |editor2-first=F. X. |editor2-link=F. X. Martin |title=The Course of Irish History |edition=Revised & enlarged 2nd |date=1984 |orig-date=1967 |location=Dublin |publisher=] / ] |isbn=9780853427100}} A newer edition exists (5th, 2012). | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ó Siochrú |first=Micheál |title=God's Executioner: Oliver Cromwell and the Conquest of Ireland |date=2008 |publisher=] |location=London |isbn=9780571241217}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Ó Snodaigh |first=Pádraig |author-link=Pádraig Ó Snodaigh |title=] |date=1995 |orig-date=1973 |publisher=] |location=Londonderry |isbn=9781873687352}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Perceval-Maxwell |first=Michael |title=The Scottish Migration to Ulster in the Reign of James I |location=Belfast |publisher=Ulster Historical Foundation |date=1999 |orig-date=1973 |oclc=633735099}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Robinson |first=Philip |title=The Plantation of Ulster: British Settlement in an Irish Landscape, 1600–1670 |date=2000 |publisher=Ulster Historical Foundation |location=Belfast}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Stewart |first=A. T. Q. |author-link=A. T. Q. Stewart |title=The Narrow Ground: The Roots of Conflict in Ulster |edition=Revised |date=1989 |orig-date=1977 |location=London |publisher=] |url= https://archive.org/details/thenarowgroundstewart/mode/2up |via=Internet Archive}} | |||

| {{Refend}} | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Adamson |first=Ian |author-link=Ian Adamson |title=The Identity of Ulster: The Land, the Language and the People |orig-year=1982 |date=1987<!--We don't care about later dates of impressions/printings.--> |edition=2nd |publisher=Pretani Press / ] |location=Newtownards, Co. Down |isbn=9780948868047}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Kaufmann |first=Eric P. |title=The Orange Order: A Contemporary Northern Irish History |date=2009 |orig-date=2007 |publisher=] |isbn=9780199532032}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{EB1911 Poster|Plantation|Plantation of Ulster}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Cite web |title=Movement of British Settlers into Ulster in the 17th Century by Dr William Macafee |url=https://ulsterhistoricalfoundation.com/ulster-plantation/movement-of-british-settlers}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Cite web |url= https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/plantation/ |title=Wars & Conflict: The Plantation of Ulster |work=History |date=18 September 2014 |publisher=]}} | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Cite web |url= https://celt.ucc.ie/published/E600001-004/index.html |title=Discourse on the Mere Irish of Ireland |author=Anonymous |date=2010 |orig-date=c. 1608 |editor1-first=Hiram |editor1-last=Morgan |editor2-first=Kenneth W. |editor2-last=Nicholls |via=], ]}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Kingdom of Ireland}} | |||

| {{Ireland topics}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:07, 12 January 2025

17th-century colonisation of northern Ireland

The Plantation of Ulster (Irish: Plandáil Uladh; Ulster Scots: Plantin o Ulstèr) was the organised colonisation (plantation) of Ulster – a province of Ireland – by people from Great Britain during the reign of King James VI and I.

Small privately funded plantations by wealthy landowners began in 1606, while the official plantation began in 1609. Most of the land had been confiscated from the native Gaelic chiefs, several of whom had fled Ireland for mainland Europe in 1607 following the Nine Years' War against English rule. The official plantation comprised an estimated half a million acres (2,000 km) of arable land in counties Armagh, Cavan, Fermanagh, Tyrone, Donegal, and Londonderry. Land in counties Antrim, Down, and Monaghan was privately colonised with the king's support.

Among those involved in planning and overseeing the plantation were King James, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Arthur Chichester, and the Attorney-General for Ireland, John Davies. They saw the plantation as a means of controlling, anglicising, and "civilising" Ulster. The province was almost wholly Gaelic, Catholic, and rural and had been the region most resistant to English control. The plantation was also meant to sever the ties of the Gaelic clans of Ulster with those from the Highlands of Scotland, as it meant a strategic threat to England. The colonists (or "British tenants") were required to be English-speaking, Protestant, and loyal to the king. Some of the landlords and settlers, however, were Catholic. The Scottish settlers were mostly Presbyterian Lowlanders and the English settlers were mostly Anglican Northerners, which their culture differed from that of the native Irish. Although some "loyal" natives were granted land, the native Irish reaction to the plantation was generally hostile, and native writers lamented what they saw as the decline of Gaelic society and the influx of foreigners.

The Plantation of Ulster was the biggest of the plantations of Ireland. It led to the founding of many of Ulster's towns and created a lasting Ulster Protestant community in the province with ties to Britain. It also resulted in many of the native Irish nobility losing their land and led to centuries of ethnic and sectarian animosity, which at times spilled into conflict, notably in the Irish Rebellion of 1641 and, more recently, the Troubles.

Ulster before plantation

Before the plantation, Ulster had been the most Gaelic province of Ireland, as it was the least anglicised and the most independent of English control. The region was almost wholly rural and had few towns or villages. Throughout the 16th century, Ulster was viewed by the English as being "underpopulated" and undeveloped. The economy of Gaelic Ulster was overwhelmingly based on agriculture, especially cattle-raising. Many of the Gaelic Irish practised "creaghting" or "booleying", a kind of transhumance whereby some of them moved with their cattle to upland pastures during the summer months and lived in temporary dwellings during that time. This often led outsiders to mistakenly believe the Gaelic Irish were nomadic.

The population of Ulster before the Plantation has been estimated to be around 180,000-200,000. This was after the destruction caused by the devastating famine and warfare at the end of the Nine Years War. Michael Perceval-Maxwell estimated that by 1600 Ulster's total adult population was only 25,000-40,000. The war fought between the native Irish Confederacy and the English Crown undoubtedly contributed to depopulation, with 60,000 reported dead by famine and attacks on the civilian population.

The Tudor conquest of Ireland began in the 1540s, during the reign of Henry VIII (1509–1547), and concluded in the reign of Elizabeth I (1558–1603) sixty years later, breaking the power of the semi-independent Irish chieftains. As part of the conquest, plantations (colonial settlements) were established in Queen's County and King's County (Laois and Offaly) in the 1550s as well as Munster in the 1580s, and in 1568 Warham St Leger and Richard Grenville established Joint stock/Cooperate colonies in Cork, although these were not very successful.

In the 1570s, Elizabeth I authorised a privately funded plantation of eastern Ulster, led by Thomas Smith and Walter Devereux, 1st Earl of Essex. This was a failure and sparked violent conflict with the local Irish lord, in which Lord Deputy Essex killed many of the lord of Clandeboy's kin.

In the Nine Years' War of 1594–1603, an alliance of northern Gaelic chieftains—led by Hugh O'Neill of Tyrone, Hugh Roe O'Donnell of Tyrconnell, and Hugh Maguire of Fermanagh—resisted the imposition of English government in Ulster and sought to affirm their own control. Following an extremely costly series of campaigns by the English the war ended in 1603 with the Treaty of Mellifont. The terms of surrender granted to what remained of O'Neill's forces were considered generous at the time.

After the Treaty of Mellifont, the northern chieftains attempted to consolidate their positions, whilst some within the English administration attempted to undermine them. In 1607, O'Neill and his primary allies left Ireland to seek Spanish help for a new rebellion to restore their privileges, in what became known as the Flight of the Earls. King James issued a proclamation declaring their action to be treason, paving the way for the forfeiture of their lands and titles.

Planning the plantation

A colonization of Ulster had been proposed since the end of the Nine Years' War. The original proposals were smaller, involving planting settlers around key military posts and on church land, and would have included large land grants to native Irish lords who sided with the English during the war, such as Niall Garve O'Donnell. However, in 1608 Sir Cahir O'Doherty of Inishowen launched a rebellion, capturing and burning the town of Derry. The brief rebellion was ended by Sir Richard Wingfield at the Battle of Kilmacrennan. The rebellion prompted Arthur Chichester, the Lord Deputy of Ireland, to plan a much bigger plantation and to expropriate the legal titles of all native landowners in the province. John Davies, the Attorney-General for Ireland, used the law as a tool of conquest and colonization. Before the Flight of the Earls, the English administration had sought to minimise the personal estates of the chieftains, but now they treated the chieftains as sole owners of their whole territories, so that all the land could be confiscated. Most of this land was deemed to be forfeited (or escheated) to the Crown because the chieftains were declared to be attainted. English judges had also declared that titles to land held under gavelkind, the native Irish custom of inheriting land, had no standing under English law. Davies used this as a means to confiscate land, when other means failed.

The Plantation of Ulster was presented to James I as a joint "British", or English and Scottish, venture to 'pacify' and 'civilise' Ulster, with half the settlers to be from one country. James had been King of Scotland before he also became King of England and wanted to reward his Scottish subjects with land in Ulster to assure them they were not being neglected now that he had moved his court to London. Long-standing contacts between Ulster and the west of Scotland meant that Scottish participation was a practical necessity. James saw the Gaels as barbarous and rebellious, and believed Gaelic culture should be wiped out. For centuries, Scottish Gaelic mercenaries called gallowglass (gallóglaigh) had been migrating to Ireland to serve under the Irish chiefs. Another goal of the plantation was to sever the ties of the Gaelic clans of Ulster with those from the Highlands of Scotland, as these ties posed a strategic threat to England.

Six counties were involved in the official plantation – Donegal, Londonderry, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Cavan and Armagh. In the two officially unplanted counties of Antrim and Down, substantial Presbyterian Scots settlement had been underway since 1606.

The plan for the plantation was determined by two factors. One was the wish to make sure the settlement could not be destroyed by rebellion as the first Munster Plantation had been in the Nine Years' War. This meant that, rather than settling the planters in isolated pockets of land confiscated from the Irish, all of the land would be confiscated and then redistributed to create concentrations of British settlers around new towns and garrisons.

What was more, the new landowners were explicitly banned from taking Irish tenants and had to import workers from England and Scotland. The remaining Irish landowners were to be granted one quarter of the land in Ulster. The peasant Irish population was intended to be relocated to live near garrisons and Protestant churches. Moreover, the planters were barred from selling their lands to any Irishman and were required to build defences against any possible rebellion or invasion. The settlement was to be completed within three years. In this way, it was hoped that a defensible new community composed entirely of loyal British subjects would be created.

The second major influence on the Plantation was the negotiation among various interest groups on the British side. The principal landowners were to be "Undertakers", wealthy men from England and Scotland who undertook to import tenants from their own estates. They were granted around 3000 acres (12 km) each, on condition that they settle a minimum of 48 adult males (including at least 20 families), who had to be English-speaking and Protestant. Veterans of the Nine Years' War (known as "Servitors") led by Arthur Chichester successfully lobbied to be rewarded with land grants of their own.

Since these former officers did not have enough private capital to fund the colonisation, their involvement was subsidised by the twelve great guilds. Livery companies from the City of London were coerced into investing in the project, as were City of London guilds which were granted land on the west bank of the River Foyle, to build their own city on the site of Derry (renamed Londonderry after them) as well as lands in County Coleraine. They were known jointly as The Honourable The Irish Society. The final major recipient of lands was the Protestant Church of Ireland, which was granted all the churches and lands previously owned by the Roman Catholic Church. The British government intended that clerics from England and the Pale would convert the native population to Anglicanism.

Implementing the plantation

Since 1606, there had been substantial lowland Scots settlement on disinhabited land in north Down, led by Hugh Montgomery and James Hamilton. In 1607, Sir Randall MacDonnell settled 300 Presbyterian Scots families on his land in Antrim.

From 1609 onwards, British Protestant immigrants arrived in Ulster through direct importation by Undertakers to their estates and also by a spread to unpopulated areas, through ports such as Derry and Carrickfergus. In addition, there was much internal movement of settlers who did not like the original land allotted to them. Some planters settled on uninhabited and unexploited land, often building up their farms and homes on overgrown terrain that has been variously described as "wilderness" and "virgin" ground. In 1612, William Cole received a grant of land to establish a settler town at Enniskillen.

By 1622, a survey found that there were 6,402 British adult males on Plantation lands, of whom 3,100 were English and 3,700 Scottish – indicating a total adult planter population of around 12,000. However, another 4,000 Scottish adult males had settled in unplanted Antrim and Down, giving a total settler population of about 19,000.

Despite the fact that the Plantation had decreed that the Irish population be displaced, this did not generally happen in practice. Firstly, some 300 native landowners who had taken the English side in the Nine Years' War were rewarded with land grants. Secondly, the majority of the Gaelic Irish remained in their native areas, but were now only allowed worse land than before the plantation. They usually lived close to and even in the same townlands as the settlers and the land they had farmed previously. The main reason for this was that Undertakers could not import enough English or Scottish tenants to fill their agricultural workforce and had to fall back on Irish tenants. However, in a few heavily populated lowland areas (such as parts of north Armagh) it is likely that some population displacement occurred.

However, the Plantation remained threatened by the attacks of bandits, known as "wood-kern", who were often Irish soldiers or dispossessed landowners. In 1609, Chichester had 1,300 former Gaelic soldiers deported from Ulster to serve in the Swedish Army. As a result, military garrisons were established across Ulster and many of the Plantation towns, notably Derry, were fortified. The settlers were also required to maintain arms and attend an annual military 'muster'.

There had been very few towns in Ulster before the Plantation. Most modern towns in the province can date their origins back to this period. Plantation towns generally have a single broad main street ending in a square in a design often known as a "diamond", which can be seen in communities like The Diamond, Donegal.

Failures

The plantation was a mixed success from the point of view of the settlers. About the time the Plantation of Ulster was planned, the Virginia Plantation at Jamestown in 1607 started. The London guilds planning to fund the Plantation of Ulster switched and backed the London Virginia Company instead. Many British Protestant settlers went to Virginia or New England in America rather than to Ulster.

By the 1630s, there were 20,000 adult male British settlers in Ulster, which meant that the total settler population could have been as high as 80,000. They formed local majorities of the population in the Finn and Foyle valleys (around modern County Londonderry and east Donegal), in north Armagh and in east Tyrone. Moreover, the unofficial settlements in Antrim and Down were thriving. The settler population grew rapidly, as just under half of the planters were women.

The attempted conversion of the Irish to Protestantism was generally a failure. One problem was language difference. The Protestant clerics imported were usually all monoglot English speakers, whereas the native population were usually monoglot Irish speakers. However, ministers chosen to serve in the plantation were required to take a course in the Irish language before ordination, and nearly 10% of those who took up their preferments spoke it fluently. Nevertheless, conversion was rare, despite the fact that, after 1621, Gaelic Irish natives could be officially classed as British if they converted to Protestantism. Of those Catholics who did convert to Protestantism, many made their choice for social and political reasons.

The reaction of the native Irish to the plantation was generally hostile. Chichester wrote in 1610 that the native Irish in Ulster were "generally discontented, and repine greatly at their fortunes, and the small quantity of land left to them". That same year, English army officer Toby Caulfield wrote that "there is not a more discontented people in Christendom" than the Ulster Irish. Irish Gaelic writers bewailed the plantation. In an entry for the year 1608, the Annals of the Four Masters states that the land was "taken from the Irish" and given "to foreign tribes", and that Irish chiefs were "banished into other countries where most of them died". Likewise, an early 17th-century poem by the Irish bard Lochlann Óg Ó Dálaigh laments the plantation, the displacement of the native Irish, and the decline of Gaelic culture. It asks "Where have the Gaels gone?", adding "We have in their stead an arrogant, impure crowd, of foreigners' blood".

Historian Thomas Bartlett suggests that Irish hostility to the plantation may have been muted in the early years, as there were much fewer settlers arriving than expected. Bartlett writes that a hatred for the planters grew with the influx of settlers from the 1620s, and the increasing marginalization of the Irish. Historian Gerard Farrell writes that the plantation stoked a "smoldering resentment" in the Irish, among whom "a widespread perception persisted that they and the generation before them had been unfairly dispossessed of their lands by force and legal chicanery". Petty violence and sabotage against the planters was rife, and many Irish came to identify with the wood-kern who attacked settlements and ambushed settlers. Ferrell suggests it took many years for an Irish uprising to happen because there was depopulation, because many native leaders had been removed, and those who remained only belatedly realised the threat of the plantation.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Further information: Wars of the Three Kingdoms and Irish Confederate WarsBy the 1630s it is suggested that the plantation was settling down with "tacit religious tolerance", and in every county Old Irish were serving as royal officials and members of the Irish Parliament. However, in the 1640s, the Ulster Plantation was thrown into turmoil by civil wars that raged in Ireland, England and Scotland. The wars saw Irish rebellion against the planters, twelve years of bloody war, and ultimately the re-conquest of the province by the English parliamentary New Model Army that confirmed English and Protestant dominance in the province.