| Revision as of 00:12, 14 February 2009 editJdorney (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers10,246 edits →1922-23: lk← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:22, 11 November 2024 edit undoLightiggy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users57,943 editsmNo edit summaryTag: Visual edit | ||

| (647 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

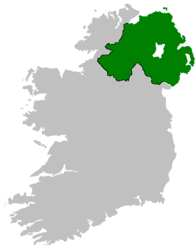

| {{short description|Specialized police force of Northern Ireland}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{More citations needed|date=December 2022}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=August 2013}} | |||

| {{Infobox law enforcement agency | |||

| | agencyname = Ulster Special Constabulary | |||

| | nativename = | |||

| | nativenamea = | |||

| | nativenamer = | |||

| | commonname = B Specials | |||

| | abbreviation = USC | |||

| | motto = | |||

| | mottotranslated = | |||

| | formed = October 1920 | |||

| | dissolved = 31 March 1970 | |||

| | superseding = ] | |||

| | employees = 5,500 | |||

| | volunteers = 26,500 | |||

| | budget = | |||

| | legalpersonality = | |||

| | country = Northern Ireland | |||

| | countryabbr = | |||

| | national = Yes | |||

| | subdivtype = | |||

| | subdivname = | |||

| | subdivdab = | |||

| | map = PSNImap.PNG | |||

| | mapcaption = | |||

| | sizearea = {{cvt|13,843|km2}} | |||

| | sizepopulation = | |||

| | badge = Ulster_Special_Constabulary.png | |||

| | police = Yes | |||

| | local = Yes | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| The '''Ulster Special Constabulary''' (USC |

The '''Ulster Special Constabulary''' ('''USC'''; commonly called the "'''B-Specials'''" or "'''B Men'''") was a quasi-military{{sfnp|English|Townshend|1998|page=96}} ] ] police force in what would later become ]. It was set up in October 1920, shortly before the ]. The USC was an armed corps, organised partially on military lines and called out in times of emergency, such as war or insurgency.{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|pages= 83–84}} It performed this role most notably in the early 1920s during the ] and the 1956–1962 ]. | ||

| During its existence, 95 USC members were killed in the line of duty. Most of these (72) were killed in conflict with the IRA in 1921 and 1922. Another 8 died during the Second World War, in air raids or IRA attacks. Of the remainder, most died in accidents but two former officers were killed during ] in the 1980s.<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| == Formation == | |||

| |title=Ulster Special Constabulary 1921–1970 | |||

| In the early twentieth century there were two police forces in ]; the ], 1,100 strong, who were unarmed and organised like other British constabularies of the time.<ref name=Hezlet3>Hezlet, p. 3</ref> The 10,000 strong ] (RIC)<ref name=Hezlet3 /> were armed with pistols and rifles and were a paramilitary force of a type not seen elsewhere in the United Kingdom. On the 21 January 1919 the ] began an aggressive policy of arms raids on the barracks of the ], leading as it did to counter raids, arrests and reprisals. This marked the beginning of the ]. The RIC began to disintegrate with 556 men resigning between May to July 1920. IRA actions in the south of the country began to alarm the unionists in the north, even though attacks in the north were rarely carried out. This was because in the north the Ulster unionists had decided to restrict their partition demands to the six north-eastern counties, the "irreducible minimum" giving them a two to one majority over nationalists.<ref>Jim McDermott, ''Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22'', Beyond the Pale (Belfast), ISBN 1 900960 11 7, pg.21</ref> This left the IRA in this part of the country too weak to take action. <ref>Jim McDermott, ''Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22'', Beyond the Pale (Belfast), ISBN 1 900960 11 7, pg.21-24</ref> | |||

| |website=National Police Officers Roll of Honour and Remembrance | |||

| |url=http://www.policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/n_ireland/usc/usc_roll.htm | |||

| |access-date=21 December 2014 | |||

| |archive-date=27 December 2014 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20141227162622/http://www.policerollofhonour.org.uk/forces/n_ireland/usc/usc_roll.htm | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| The force was almost exclusively ] and as a result was viewed with great mistrust by Catholics. It carried out several revenge killings and ]s against Catholic civilians in the 1920–22 conflict. See ] and ].{{sfnp|Hopkinson|2004|page= 263}}<ref name="HI, Unholy War" /> Unionists generally supported the USC as contributing to the defence of Northern Ireland from ] and outside aggression.{{sfnp|Hennessey|1997|page=15}} | |||

| The RIC an all-Ireland force, which contained a clear Catholic majority, was not trusted by Unionists . This mistrust increased when it was discovered that the more inefficient, older and suspect members were transferred north while clearly loyalist members were being placed in areas were the IRA campaign was more intense.<ref>Jim McDermott, ''Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms 1920-22'', Beyond the Pale (Belfast), ISBN 1 900960 11 7, pg.21-22</ref> | |||

| The Special Constabulary was disbanded in May 1970, after the ], which advised re-shaping Northern Ireland's security forces to attract more Catholic recruits<ref name=autogenerated1>{{Cite web |url=http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/hunt.htm |title=CAIN: HMSO: Hunt Report, 1969<!-- Bot generated title --> |access-date=28 April 2008 |archive-date=20 February 2015 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150220052147/http://www.cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/hunt.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> and demilitarizing the police. Its functions and membership were largely taken over by the ] and the ].{{sfnp|Elliott|Flackes|1999}} | |||

| In April 1920, ], future Prime Minister of Northern Ireland,<ref>Liz Curtis, The Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Beyond the Pale Publications 1995, Belfast, ISBN 0 9514229 60, p. 344</ref> organised "Fermanagh Vigilance", a ] group to provide defence according to Arthur Hezlet, against incursions by the ].<ref>Hezlet, pp. 10-11</ref> This worried the government in Dublin he says, as sectarian rioting between Protestants and Catholics was commonplace in the major cities of ] and ].<ref name=Hezlet10>Hezlet, page 10</ref> | |||

| ==Formation== | |||

| The British army while guarding Catholic properties clashed with Protestant crowds with fatal consequences. This resulted in ] creating an “unofficial special constabulary,” with members drawn chiefly from the shipyards, tasked with ‘policing’ Protestant areas. Carson and Craig's need to establish a militant basis for resistance to republicanism wished to reconstitute the UVF’ which could operate independently of the British Army. They then set about securing British government approval and funds for the UULA constabularies in Belfast along with the UVF.<ref name=Bew1819>Paul Bew, Peter Gibbon and Henry Patterson, ''Northern Ireland: 1921 / 2001 Political Forces and Social Classes'', Serif (London 2002), ISBN 1 897959 38 9, pp.18-19</ref> | |||

| The Ulster Special Constabulary was formed against the background of conflict over Irish independence and the ]. | |||

| The 1919–21 ], saw the ] (IRA) launch a guerrilla campaign in pursuit of Irish independence. ] in Ireland's northeast were vehemently against this campaign and against Irish independence. However, once it became apparent that the British government was committed to implementing Dominion Status for all of Ireland outside Ulster in response to Sinn Féin's demands, which were far more radical than those of the defunct Irish Parliamentary Party, Unionists in most of the province of Ulster directed their energies into the partition of Ireland by the creation of ] as an autonomous region in the United Kingdom. The new region would consist of two thirds of ], the six counties that Unionists could control. The other three counties (Donegal, Monaghan, and Cavan) had disproportionately Catholic and nationalist majorities and would become part of the Irish Free State. Partition was enacted by the British Parliament in the ].{{sfnp|Farrell|1983|pages=7–8 }} | |||

| While ] ] of the British army in Ireland withheld his approval, he and his supporters in the Irish administration were overridden; ]’s approved from the beginning and granted official status in the form of the ] in November 1920. This official endorsement shaped both the formation of the state of Northern Ireland and Catholic feelings to it.<ref name=Bew1819 /> There was an immediate and illicit supply of arms available to these Protestant organisations; those which had belonged to the pre-war ].<ref name=Hezlet10 /> | |||

| Two main factors were behind the formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary. One was the desire of Unionists, led by ] (then a junior minister in the British Government, and later the ]), that the apparatus of government and security should be placed in their hands long before Northern Ireland was formally established.{{sfnp|Hopkinson|2004|page= 155}} | |||

| In July 1920 the Unionist leaders ] and ] commenced the reorganisation of the Ulster Volunteer Force which had ceased functioning after the ], though its network remained. The revived UVF was still illegal, although it had the tacit approval of ]. In the countryside prominent landowners organised recruitment and Belfast newspapers carried advertisements for the UVF.<ref>Liz Curtis, The Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Beyond the Pale Publications 1995, Belfast, ISBN 0 9514229 60, pg. 344-5</ref> | |||

| A second reason was that violence in the north was increasing after the summer of 1920. The IRA began extending attacks to the ] (RIC), RIC barracks, and revenue offices in Northern Ireland. There had been serious rioting between Catholics and Protestants in ] in May and June and in ] in July, which had left up to 40 people dead.{{sfnp|Hopkinson|2004|page= 155–156}} (See ] and ].) | |||

| After much parliamentary debate it was decided towards the end of October 1920 to use legislation contained in the "Special Constables (Ireland) Acts of 1832 and 1914 to "enrol special constables"<ref>Hezlet, p. 19</ref> On 1 November 1920 advertisements appeared in the Belfast papers for "law abiding citizens" to apply for enrolment.<ref name="Liz Curtis 1995, pp. 346-7">Liz Curtis, The Cause of Ireland: From the United Irishmen to Partition, Beyond the Pale Publications 1995, Belfast, ISBN 0 9514229 60, pp. 346-7</ref><ref>Richard Bourke, Peace in Ireland: The War of Ideas, Pimlico 2003, ISBN 1 8441 3316 8, p. 48</ref><ref>The Crowned Harp: Policing Northern Ireland, Graham Ellison, Jim Smyth, Pluto Press, 2000, ISBN 0745313930, pp. 25-6</ref> | |||

| With police and troops being drawn towards combating insurgency in the south and west, Unionists wanted a force that would be dedicated to taking on the IRA. At a 2 September 1920 meeting of government Ministers in London Craig said that the loyal population was losing faith in the government's ability to protect them and that loyalist paramilitary groups threatened, in the words of Craig, "a recourse to arms, which would precipitate civil war".<ref>Lawlor, Pearse (2009), ''The Burnings 1920'', Mercier Press, Dublin, pgs 161-162, ISBN 978 1 85635 612 1</ref> Craig proposed to the British cabinet a new "volunteer constabulary" which "must be raised from the loyal population" and organised, "on military lines" and "armed for duty within the six county area only". On 23 July 1920 Craig informed the British cabinet that the "Specials" would "prevent mob law and the Protestants from running amok."<ref>McCluskey, Fergal, (2013), ''The Irish Revolution 1912-23: Tyrone'', Four Courts Press, Dublin, pg 92, ISBN 9781846822995</ref> He recommended that "the organisation of the ] (UVF), (the unionist militia formed in 1912) should be used for this purpose".{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 84}} ], the former UVF quartermaster in 1913–14, and by now a decorated war veteran, was appointed by Craig to form and run the USC. UVF units were "incorporated en masse" into the new USC.<ref name="historyireland.com" /> | |||

| ===Opposition=== | |||

| In his ''History of the Ulster Special Constabulary'' ] ] who was commissioned to write the history, which according to his obituarist in '']'' "was later dismissed as merely a defence of policing in the province",<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1568789/Vice-Admiral-Sir-Arthur-Hezlet.html|title=Vice-Admiral Sir Arthur Hezlet|work=]|date=12 November 2007|accessdate=4 December 2008}}</ref> contends that: | |||

| The idea of a volunteer police force in the north appealed to ] ] for several practical reasons; it freed up the RIC and military for use elsewhere in Ireland, it was cheap, and it did not need new legislation. Special Constabulary Acts had been enacted in 1832 and 1914, meaning that the administration in ] only had to use existing laws to create it. The formation of the Ulster Special Constabulary was therefore announced on 22 October 1920.{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 84}}{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|page=19}} | |||

| <blockquote>Sinn Fein regarded the Specials as an excuse for arming the Orangemen and an act even more atrocious then the creation of the 'Black and Tans'! Their fury was natural as they saw that the Specials might well mean that they would be unable to intimidate and subdue the North by Force." Their skilful propaganda set about blackening the image of Special Constables, trying to identify them with the worst elements of the Protestant mobs in Belfast. They sought to magnify and distort every incident and to stir up hatred of the force even before it started to function.</blockquote> | |||

| On 1 November 1920, the scheme was officially announced by the British government.{{sfnp|Curtis|1995|pages=346–347}}{{sfnp|Bourke|2003|page=48}}{{sfnp|Ellison|Smyth|2000|pages= 25–26}} | |||

| Because of these differences which were well aired in the media of the time, there was a general unwillingness of Catholics in the North of Ireland to take part in the organisation of the USC. The political and church personalities of the time discouraged involvement and as a result the USC became overwhelmingly Protestant from its inception, although "a number of moderate Catholics did join." <ref>Hezlet, p. 22-24</ref> | |||

| ==Composition== | |||

| The composition of the USC was overwhelmingly Protestant and Unionist, for a number of reasons. Several informal "constabulary" groups had already been created, for example, in Belfast, Fermanagh and Antrim. The ] had established an "unofficial special constabulary," with members drawn chiefly from the shipyards, tasked with 'policing' Protestant areas.{{sfnp|Bew|Gibbon|Patterson|2002|pages= 18–19 }} | |||

| In April 1920, ] (future ]), had set up "Fermanagh Vigilance", a ] group to provide defence against incursions by the IRA. Brooke himself had been personally affected by the organisation, as his son had been a victim of kidnapping. {{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|pages=10–11}} In ], a Protestant rector named John Redmond had helped form a unit of ex-servicemen to keep the peace after the July riots.{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|pages= 46–47}} | |||

| There was a willingness to arm or recognise existing Protestant militias. Wilfrid Spender, head of the Ulster Volunteer Force, encouraged his members to join.{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 86}} For these groups, was an immediate and illicit supply of arms available, especially from the Ulster Volunteers.{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|page=10}} ], Chief of Police for the north of Ireland, favoured incorporation of the Ulster Volunteers into "regular military units" instead of having to "face them down".{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 88}} A number of these groups were absorbed into the new Ulster Special Constabulary.{{citation needed|date=November 2021}} | |||

| Nationalists pointed out that the composition of the USC was overwhelmingly Protestant and loyal, claiming the government was arming Protestants to attack Catholics.{{sfnp|Doherty|2004|page=14}} In addition, a number of Special Constables, newly appointed by the Lisburn Urban Council, had been charged with rioting and looting committed over three days and nights following the assassination of RIC Inspector Oswald Swanzy. During that same time period, members of the Dromore UVF were said to have supervised the expulsion of Catholic families from Dromore. A further detail was that many UVF units joined the new Constabulary, with their commanders being appointed to senior positions.<ref>Lawlor, pg, 162.</ref> | |||

| Unsuccessful efforts were made to attract more Catholics into the force, but these largely failed.{{sfnp|Curtis|1995|pages=346–347}}{{sfnp|Magee|1974|page=70}} One reason for this was that Catholic members were more easily targeted by the IRA for intimidation and assassination. The government suggested that, with enough Catholic recruits, special constabulary patrols made up of Catholics only could be extended into Catholic areas.{{sfnp|Doherty|2004|pages=14, 18}} However, the ] and ] discouraged their members from joining.{{citation needed|date=November 2014}} | |||

| The IRA issued a statement which said that any Catholics who joined the Specials would be treated as traitors and would be dealt with accordingly.{{sfnp|Doherty|2004|page=14}} | |||

| ==Organisation== | ==Organisation== | ||

| The USC was initially financed and equipped by the British government and placed under the control of the RIC. The USC consisted of 32,000 men divided into four sections, all of whom were armed: | |||

| ] | |||

| * A Specials – full-time and paid, worked alongside regular RIC men, but could not be posted outside their home areas (regular RIC officers could be posted anywhere in the country); usually served at static checkpoints (originally 5,500 members){{sfnp|Doherty|2004}} | |||

| The USC consisted of 32,000 men divided into four sections, all of which were armed: | |||

| * B Specials – part-time, usually on duty for one evening per week and serving under their own command structure, and unpaid, although they had a generous system of allowances (which were reduced following the reorganisation of the USC a few years later), served wherever the RIC served and manned Mobile Groups of platoon size;<ref> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060627220808/http://www.psni.police.uk/index/pg_police_museum/pg_the_royal_ulster_constabulary/pg_ulster_special_sonstabulary.htm |date=27 June 2006 }}</ref> (originally 19,000 members){{sfnp|Doherty|2004}} | |||

| * C Specials – unpaid, non-uniformed reservists, usually rather elderly and used for static guard duties near their homes (originally 7,500 members){{sfnp|Doherty|2004}} | |||

| ** C1 Specials – non-active C class specials who could be called out in emergencies. The C1 category was formed in late 1921, incorporating the various local unionist militias such as the ] into a new special class of the USC, thus placing them under the control and discipline of the Stormont Government.{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|pages=50–52}} | |||

| The units were organised on military lines up to company level. ]s had two officers, a ], four ]s and sixty special constables.{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|page=27}} | |||

| * A Specials - full-time and paid, worked alongside regular RIC men, but could not be posted outside their home areas (regular RIC officers could be posted anywhere in the country); usually served at static checkpoints. (originally 5,500 members)<ref>The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5</ref> | |||

| The Belfast units were constructed differently from those in the counties. The districts were based on the existing RIC divisions. The constables drew pistols and truncheons before going on patrol and considerable efforts were made to use them only in Protestant areas. This did free up regular policemen who were generally more acceptable to most Ulster Catholics.{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|page=29}} | |||

| * B Specials - part-time, usually on duty for one evening per week and serving under their own command structure, and unpaid, although they had a generous system of allowances (which were reduced following the reorganisation of the USC a few years later), served wherever the RIC served and manned Mobile Groups of platoon size.<ref></ref>); (originally 19,000 members)<ref>The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5</ref> and | |||

| * C Specials - unpaid, non-uniformed reservists, usually rather elderly and used for static guard duties near their homes. (originally 7,500 members)<ref>The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5</ref> | |||

| * C1 Specials - non active C class specials who could be called out in emergencies. | |||

| By July 1921, more than 3,500 'A' Specials had been enrolled, and almost 16,000 'B' Specials. By 1922 recruiting had swelled the numbers to: 5,500 A Specials, 19,000 B Specials and 7,500 C1 Specials. Their duties would include combatting the urban guerrilla operations of the IRA, and the suppression of the local IRA in rural areas. In addition they were to prevent border incursion, smuggling of arms and escape of fugitives.{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|page=83}} | |||

| The units were organised on military lines up to ] level. ]s had two officers, a ], four ]s and sixty special constables. <ref>Hezlet, p. 27</ref> | |||

| ===Opposition=== | |||

| The Belfast units were constructed differently to those in the counties. The districts were based on the existing RIC divisions. The constables drew pistols and truncheons before going on patrol and were considerable efforts made to use them only in Protestant areas. This did free regular policemen who were generally more acceptable to residents of all areas.<ref>Hezlet, p. 29</ref> | |||

| From the outset, the formation of the USC came in for widespread criticism, mostly from Irish nationalists and the Dublin government but also from some elements of the British military and administrative establishment in Ireland and in the British press, which saw the USC as a potentially divisive and sectarian force. In the British House of Commons, the leader of the ] of Northern Ireland, ], formerly a leading member of the now defunct Irish Parliamentary Party, made his feelings on the creation of the USC clear: "The Chief Secretary is going to arm pogromists to murder Catholics...we would not touch your special constabulary with a 40 foot pole. Their pogrom is to be made less difficult. Instead of paving stones and sticks they are to be given rifles."<ref>Bardon, Jonathan, (2001), ''A History of Ulster'', Blackstaff Press, Belfast, p. 476; ISBN 0 85640 703 8</ref> | |||

| ], ] of the British Army in Ireland, along with his supporters in the Irish administration, refused to approve the new force but were overridden; ] approved of it from the beginning.{{sfnp|Bew|Gibbon|Patterson|2002|page= 28 }} Macready and ] argued that the concept of a special constabulary was a dangerous one.{{efn-lr|Wilson wrote, "To arm those "Black men" in the north without putting them under discipline is to invite trouble."{{sfnp|Bew|Gibbon|Patterson|2002|page= 28 }}}}{{sfnp|Macready|1924|page=488}} | |||

| By July 1921, more than 3,500 ‘A’ Specials had been enrolled, and almost 16,000 ‘B’ Specials. Virtually all were Protestants: recruitment of Catholics was not encouraged by officialdom and was opposed by Sinn Féin and the IRA, and in any case few Catholics wanted to join.<ref name="Liz Curtis 1995, pp. 346-7"/><ref>''Northern Ireland: Crisis and Conflict'', John Magee, Routledge, 1974, ISBN 071007946X, p. 70</ref> By 1922 recruiting had swelled the numbers to: 5,500 A Specials, 19,000 B Specials and 7,500 C1 Specials. | |||

| Wilson warned the formation of a partisan constabulary "would mean; taking sides, civil war and savage reprisals."{{sfnp|Bew|Gibbon|Patterson|2002|page= 28 }}<ref>''Wilson papers'', 26 July 1920, in Gilbert, ''Churchill'', Companion Vol. 4, part 2, p. 1150.</ref> ], the ] (head of the British Administration in Dublin) shared his fears, "you cannot, in the middle of a faction fight, recognise one of the contending parties and expect it to deal with disorder in the spirit of impartiality and fairness essential in those who have to carry out the order of the Government."{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 87}} | |||

| ==Recruitment== | |||

| The USC was initially financed and equipped by the British government and placed under the control of the RIC. Deployment in 1920-22 provided the Northern Ireland government with its own territorial militia, repelling IRA attacks. It was the USC that was most often responsible for countering IRA attacks in the north. The ], ] and the ] discouraged Catholic recruitment. The IRA targeted for assassination those Catholics who did join. The Unionist government did nothing to reverse these trends as they perceived Catholics to be disloyal to the state.<ref>''The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC,'' Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5 p. 14</ref> | |||

| The Irish nationalist press was less reserved. The '']'' noted the opposition of Irish nationalists:<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| In the latter stages before their replacement by the ] Lord Justice Scarman concluded in his report on the Civil Disturbance in the Province in 1969 that: ''Undoubtedly mistakes were made and certain individual officers acted wrongly on occasions. But the general case of a partisan force co-operating with Protestant mobs to attack Catholic people is devoid of substance, and we reject it utterly.''<ref name="cain.ulst.ac.uk">http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm#5</ref> Scarman went on to criticise the Command and Control of the RUC for deploying armed specials in areas where their very presence would "heighten tension" as he was in no doubt that they were "Totally distrusted by the Catholics, who saw them as the strong arm of the Protestant ascendancy".<ref name="cain.ulst.ac.uk"/> | |||

| |title= | |||

| |newspaper=] |date=27 November 1920}}</ref>{{blockquote|These "Special Constables" will be nothing more and nothing less than the dregs of the Orange lodges, armed and equipped to overawe Nationalists and Catholics, and with a special object and special facilities and special inclination to invent 'crimes' against Nationalists and Catholics... they are the very classes whom an upright Government would try to keep powerless...}} | |||

| ] ] in the official ''History of the Ulster Special Constabulary'',<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1568789/Vice-Admiral-Sir-Arthur-Hezlet.html |title=Vice-Admiral Sir Arthur Hezlet |newspaper=] |date=12 November 2007 |access-date=9 December 2022 |archive-date=10 November 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121110184334/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1568789/Vice-Admiral-Sir-Arthur-Hezlet.html |url-status=live}}</ref> contended that "Sinn Fein regarded the Specials as an excuse for arming the Orangemen and an act even more atrocious than the creation of the ']'! Their fury was natural as they saw that the Specials might well mean that they would be unable to intimidate and subdue the North by Force. Their skilful propaganda set about blackening the image of Special Constables, trying to identify them with the worst elements of the Protestant mobs in Belfast. They sought to magnify and distort every incident and to stir up hatred of the force even before it started to function."{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|pages=22–24}} | |||

| The B Specials were a Protestant only force, <ref>''Northern Ireland: The Orange State'' (1976) ISBN 0-902818-87-2</ref> however according to Richard Doherty there were some Catholic members, even in Derry;<ref>The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5, p. 82</ref> In his report ] concluded that it would have been very difficult for Catholics to gain membership in 1969, even if they had applied to join. | |||

| ==Training, uniform, weaponry and equipment== | ==Training, uniform, weaponry and equipment== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] Museum]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The standard of training was varied. In Belfast, the Specials were trained in much the same way as the regular police whereas in rural areas the USC was focused on counter-guerrilla operations. In 1922, B Specials received two weeks training and A Specials were initially given six weeks training. The amount of training was clearly inadequate for a conflict that warranted the deployment of professionally trained soldiers.<ref>Magill, Christopher, ''Political Conflict in East Ulster, 1920-22'', (2020), Boydell Press, Woodbridge, pg 120, ISBN 978-1-78327-511-3</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Uniforms were not available at the outset so the men of the B Specials went on duty in their civilian clothes wearing an armband to signify they were Specials. Uniforms did not become available until 1922. Uniforms took the same pattern as RIC/RUC dress with high collared tunics. Badges of rank were displayed on the right forearm of the jacket.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071005210715/http://www.psni.police.uk/index/pg_police_museum/pg_the_royal_ulster_constabulary/pg_ulster_special_sonstabulary/pg_governers_guard_uniform.htm|date=5 October 2007}}</ref> | |||

| ===Training=== | |||

| The standard of training was varied. In Belfast, the Specials were trained in much the same way as the regular police. This set them apart from their colleagues in (especially) the border counties who were less versed in the law but very adept at adopting and defeating guerilla-style tactics. In all sub-districts the standard of shooting was uniformly high and maintained by a series of shooting competitions which continued throughout the history of the force. A Specials were initially given six weeks training at ] Camp in police duties, the use of arms, drill and discipline.{{Fact|date=December 2008}} | |||

| The Special Constables were armed with ] revolvers and also ]s and ].{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 85}} By the 1960s ] and ]s were also used. In most cases these weapons were retained at home by the constables along with a quantity of ammunition. One of the reasons for this was to enable rapid call out of ]s, via a runner from the local RUC station, without the need to issue arms from a central armoury. | |||

| ===Uniforms=== | |||

| Uniforms were not available at the outset so the men of the B Specials went on duty in their civilian clothes wearing an armband to signify they were Specials. Uniforms did not become available until 1922. Uniforms took the same pattern as RIC/RUC dress with high collared tunics. Badges of rank such as sergeant's chevrons were displayed on the right forearm of the jacket in the style of the RIC, a practice which continued until disbandment. There was no ceremonial uniform but those who were part of the Governor's Guard detachment at his private residence at Co Tyrone and also at his official home at ] wore several attachments which were peculiar to this duty i.e. a broad green ], a polished leather nine pouch bandolier and the monogrammed letters "GG" on both shoulder straps.<ref>http://www.psni.police.uk/index/pg_police_museum/pg_the_royal_ulster_constabulary/pg_ulster_special_sonstabulary/pg_governers_guard_uniform.htm</ref> | |||

| 'A Special' platoons were fully mobile using a ] car for the officer in charge, two armoured cars and four ] (one for each of the sections). | |||

| ===Weaponry=== | |||

| Most specials were armed with a ] revolver but in some cases this was augmented by a Lee Enfield .303 rifle or, in the 1960s ] Guns which were later replaced by ]s. In most cases these weapons were retained at home by the constables along with a quantity of ammunition. One of the reasons for this was to enable rapid call out of platoons without the need to issue arms from a central armoury. In the days before each home had a telephone a single call for assistance to the local RUC station or USC commander would result in a runner knocking the door of each special's home in a given area and informing him of the incident. Thus a rapid reaction force could be assembled quite quickly. This practice was retained for many years by some ] units in the border areas.{{Fact|date=December 2008}} | |||

| B Specials generally deployed on foot but could be supplied with vehicles from the police pool. | |||

| ===Equipment=== | |||

| "A Special" Platoons were fully mobile using a ] car for the officer in charge, two armoured cars and four ] Tenders (one for each of the sections). | |||

| ==Irish War of Independence (1920–22)== | |||

| B Specials generally deployed on foot but could be supplied with vehicles from the RUC pool. | |||

| Deployment of the USC during the Anglo-Irish War provided the Northern Ireland government with its own territorial militia to fight the IRA. The use of Specials to reinforce the RIC also allowed for the re-opening of over 20 barracks in rural areas which had previously been abandoned because of IRA attacks.{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|page=32}} The cost of maintaining the USC in 1921–22 was £1,500,000. | |||

| Their conduct towards the Catholic population was criticised on a number of occasions. In February 1921, Specials and UVF men burned down ten Catholic houses in the County Fermanagh village of ] after a Special who lived in the village was shot and wounded.<ref name="historyireland.com"/> Following the death of a Special Constable near ] on 8 June 1921, it was alleged that Specials and an armed mob were involved in the burning of 161 Catholic homes and the death of 10 Catholics. An inquest advised that the Special Constabulary "should not be allowed into any locality occupied by people of an opposite denomination."{{sfnp|Farrell|1976|pages=40–41}} The government suggested the recruitment of more Catholics to form "Catholic only" patrols to cover Catholic areas, but this was not acted upon.{{sfnp|Doherty|2004|page=14}} | |||

| ==Duties== | |||

| After the Truce between the IRA and the British on 11 July 1921, the USC was demobilised by the British and the IRA was given official recognition while peace talks were ongoing.{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|page=80}} However, the force was remobilised in November 1921, after security powers were transferred from London to the Northern Ireland Government. | |||

| According to Hezlet their duties would include the control of the urban guerilla operations of the IRA, and the suppression of the indigenous IRA in rural areas. In addition they were to prevent border incursion, smuggling of arms and escape of fugitives. <ref>Hezlet p. 83</ref> | |||

| ] planned a clandestine guerrilla campaign against Northern Ireland using the IRA. In early 1922, he sent IRA units to the border areas and arms to northern units. On 6 December the Northern authorities ordered an end to the Truce with the IRA.{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|pages=88–89}} | |||

| ==Effectiveness== | |||

| According to Hezlet the policy of introducing large numbers of Special Constables to patrol the province had an effect almost immediately and police reports from as early as December 1920 show a "decrease in outrages in ] and ] ''doubtless due to the activities of the mobile patrols of Special Constabulary.''" He suggests that the use of Specials to re-inforce the RIC also allowed for the re-opening of over 20 barracks in rural areas which had previously been abandoned because of IRA attacks. This he says gave the RIC more control and denying the IRA the tactical advantage of being able to occupy areas of Ulster. <ref>Hezlet, p. 32</ref> | |||

| The Special Constabulary was, as well as an auxiliary to the police, effectively an army under the control of the Northern Ireland administration. By incorporating the former UVF into the USC as the C1 Specials, the Belfast government had created a mobile reserve of at least two brigades of experienced troops in addition to the A and B Classes who, between them, made up at least another operational infantry brigade, which could be used in the event of further hostilities,{{sfnp|Hezlet|1972|pages=53, 82}} and were in early 1922. | |||

| ===1922: Border conflict and reprisals=== | |||

| In general the policy proved superior according to Hezlet to that of General Tudor in the other three provinces whose tactics of patrolling and reprisal(official or unofficial), although causing more casualties for the IRA, also provided more opportunities for ambushes against police and military units and was deemed a "disastrous failure" Hezlets contends.<ref>Hezlet pp. 32-37</ref> | |||

| The USC's most intense period of deployment was in the first half of 1922, when conditions of a low-intensity war existed along the new ] between the Free State and Northern Ireland. | |||

| The ] had agreed the partition of Ireland, between the ] and ]. The IRA, although now split over the Treaty, continued offensive operations in Northern Ireland, with the co-operation of ], leader of the Free State, and ], leader of the Anti-Treaty IRA faction. This was despite the ] which was signed by the leaders of Northern Ireland and the Free State on 30 March, and envisaged the end of IRA activity and a reduced role for the USC.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://sarasmichaelcollinssite.com/mcccagreement.htm |title=Craig-Collins Agreement text; downloaded 7 November 2010 |access-date=7 November 2010 |archive-date=16 July 2012 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120716070253/http://sarasmichaelcollinssite.com/mcccagreement.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==1920-1921== | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=December 2008}} | |||

| After the formation of the force patrolling commenced by A and B Class Specials and they were instrumental in the suppression of insurgency by the IRA until the ] of 11 July 1921. <ref>Hezlet p. 45</ref> IRA activity continued to some extent from 14 July and appeared to be increasing. As part of the process of partitioning Ireland the command of the USC was transferred to the new administration in Belfast but responsibility for administration remained at that juncture with the RIC Inspector General in ].<ref>Hezlet p. 48</ref> At this point the force was known as the "Royal Irish Special Constabulary" <ref>Hezlet p. 49</ref> Around this time it became known to ] ministers that ] F.H. Crawford was actively reorganising the pre-war Ulster Volunteer Force as a means of providing a force which would be offered to the crown in the event of an invasion from the new Irish ]. Officials in both the northern and southern states were concerned that this force could be used for unofficial reprisals against the Catholic population so an agreement was reached that these men would be recruited to a new special class of the USC called "C1". Thus placing them under the control and discipline of the Stormont Government.<ref>Hezlet pp. 50-52</ref> | |||

| The renewed IRA campaign involved attacking barracks, burning commercial buildings and making a large-scale incursion into Northern Ireland, occupying ] and ] in May–June, which was repulsed after heavy fighting, including British use of artillery on 8 June.{{sfnp|Potter|2001|page= 4}}{{sfnp|Hopkinson|2004b|pages=82–87}}<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1922/06/09/99028912.pdf | |||

| |title=British Guns Drive Irish From Belleek | |||

| |newspaper=] | |||

| |date=9 June 1922 | |||

| |access-date=22 November 2011 | |||

| |archive-date=25 September 2021 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210925144333/https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1922/06/09/99028912.pdf | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| The British Army was only used in the Pettigo and Belleek actions. Therefore, the main job of counter-insurgency in this border conflict fell to the Special Constabulary while the RIC/RUC patrolled the interior. Forty-nine Special Constables were killed during the period of the "Border War", out of a total of eighty-one British forces killed in Northern Ireland.{{sfnp|Potter|2001|page= 5}}{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|page=67}}{{efn-lr|Another 530 civilians and 35 IRA men were killed in the Northern conflict of 1920–1922.{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|page=227}}}} Their biggest single loss of life came at ] in February 1922, when a patrol which entered the Free State refused to surrender to the local IRA garrison and took four dead and eight wounded in a firefight.{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|pages=141–144}} | |||

| The new Provisional Government of the Irish Free State were unhappy at the continued recruitment of the USC.<ref name=Hezlet52>Hezlet p. 52</ref> Their hopes were still high that Ulster would be ceded to the south and the island nation retained.<ref name=Hezlet52 /> If this did not happen they had considered seizing the province in any case but the inclusion of an armed police force was an active complication.<ref name=Hezlet52 /> As the external defence of the new state of Northern Ireland was a ] responsibility the Stormont administration had no power to raise an army. There is no doubt that the Special Constabulary was the army which Stormont desired under a different name, and that the Westminster government "connived at this practice". The true state of affairs was that; by incorporating the former UVF into the USC as the C1 Specials, the Belfast government had created a mobile reserve of at least 2 Brigades<ref>Hezlet p. 82</ref> of experienced troops in addition to the A and B Classes who, between them, made up at least another operational infantry brigade.<ref>Hezlet p. 53</ref> Added to the three regular army brigades based in Northern Ireland at that time the number of troops available to counter any invasion from the south was 2 infantry ]s. | |||

| In addition to action against the IRA, the USC may have been involved in a number of attacks on Catholic civilians in reprisal for IRA actions,{{sfnp|Doherty|2004|page=18}} for example, in Belfast, the ] of March 1922, in which six Catholics were killed,{{sfnp|Doherty|2004|page=18}}{{sfnp|Farrell|1976|page=51}} and the ] a week later which killed another six.{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|pages=122–123}} On 2 May 1922, in revenge for the IRA killing of six policemen in counties Londonderry and Tyrone, Special Constables killed nine Catholic civilians in the area.{{sfnp|Lynch|2006|pages=141–143}} | |||

| *'''Cost''' - The cost of maintaining the USC in 1921-22 was £1,500,000. | |||

| The conflict never formally ended but petered out in June 1922, with the outbreak of the ] in the Free State and the wholesale arrest and internment of IRA activists in the North.{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|page= 316}} Collins continued to arrange the supply of arms covertly to the Northern IRA until shortly before his death in August 1922.<ref>{{Cite news | |||

| Reprisals taken by Protestants for IRA attacks according to Richard Doherty, were often wrongly credited to the B Specials, and although the official British government policy of reprisals by police irregulars and auxiliaries was never extended to Ulster and "discipline held in most cases."<ref>The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5 p. 14</ref> | |||

| |title=Why 'The Big Fellow' has little to teach political parties in modern Ireland | |||

| |url=http://www.independent.ie/opinion/analysis/why-the-big-fellow-has-little-to-teach-political-parties-in-modern-ireland-2307165.html | |||

| |newspaper=] | |||

| |date=22 August 2010 | |||

| |author=John-Paul McCarthy | |||

| |access-date=7 November 2010 | |||

| |archive-date=2 November 2011 | |||

| |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111102114020/http://www.independent.ie/opinion/analysis/why-the-big-fellow-has-little-to-teach-political-parties-in-modern-ireland-2307165.html | |||

| |url-status=live | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Assessments of the USC's role in this conflict vary. Unionists have written that the Special Constabulary, "saved Northern Ireland from anarchy" and "subdued the IRA", while nationalist authors have judged that their treatment of the Catholic community, including, "widespread harassment and a significant number of reprisal killings" permanently alienated nationalists from the USC itself and more broadly, from the Northern Irish state.{{sfnp|Parkinson|2004|pages= 94–95}} | |||

| Following the death of a special constable near Newry on 8 June 1921, specials raided a house and killed two catholic men named Magill and beat up their 78 year old father.<ref>''Northern Ireland: The Orange State'' (1976) ISBN 0-902818-87-2</ref> The Specials and an armed mob were also involved in the burning of 161 catholic homes and the death of 10 Catholics. The violence continued for a week and in the end 23 civilians had been killed 16 Catholic and 10 Protestant and a total of 216 Catholic homes destroyed. One of the dead was a 13 year old catholic school girl shot by the specials and at her inquest the coroners jury said ''We think that in the interests of peace the Special Constabulary should not be allowed into any locality occupied by people of an opposite denomination.''<ref>''Northern Ireland: The Orange State'' (1976) ISBN 0-902818-87-2</ref> | |||

| == 1920s to 1940s == | |||

| ==1922-23== | |||

| After the end of the 1920–22 conflict, the Special Constabulary was re-organised. The regular ] (RUC) took over normal policing duties.{{sfnp|Steffens|2007|page=4}} | |||

| {{Refimprovesect|date=December 2008}} | |||

| ] | |||

| The 'A' and 'C' categories of the USC were dispensed with, leaving only the B-Specials, who functioned as a permanent reserve force, and armed and uniformed in the same manner as the RUC.{{sfnp|Steffens|2007|page=4}} | |||

| The Anglo-Irish Agreement did not end violence in Ireland. The IRA split over acceptance of the Treaty and would eventually fight each other in the ]. Despite their internal divisions in the South, ], now commanding the pro-treaty ], and ], commander of the ], agreed to combine resources to Launch an offensive on the newly created administration in Northern Ireland. This policy was partly designed bring relief to the Catholics of the North who were being victimised in an organised Protestant ] and partly to try to -reunite the IRA against a common enemy. Early 1922 saw a number of violent incidents involving the USC and the IRA along the new border. On February 11, a group of Special Constables entered Southern Territory while changing trains at ]. They were asked to surrender by the local IRA garrison but refused and opened fire, killing an IRA officer. Four Special Constables were killed in the ensuing fire-fight and the remainder captured and held prisoner. The withdrawal of British troops from Southern Ireland was temporarily suspended as a result. | |||

| The Special Constabulary were called out during the ] period in Belfast in 1931 after sectarian rioting broke out. The B Specials were tasked to relieve the RUC from normal duties, to allow them and the British Army to deal with the disturbances.{{sfnp|Potter|2001|page= 5}} | |||

| On 30 March 1922 an agreement was signed between Michael Collins and Sir James Craig which came to be known as the ].<ref>http://hansard.millbanksystems.com/commons/1922/jun/14/peace-pact-belfast</ref> which, included according to Hezlet, the possibility of a cessation of hostilities in the north and encouragement for Catholics to join the police and USC.<ref>Hezlet p. 66</ref> Unfortunately he contends, the committee for the selection of Catholic recruits in Dublin failed to make any selections and the pact was allowed to be forgotten.<ref>Hezlet p. 67</ref> The IRA at this time Hezlet suggests were 112,650 strong before the March 1922 split and there was a further 8,500 in the Northern Command although these were primarily anti-treaty so Collins had very little control over them in any case. <ref>Hezlet p. 69</ref> Moreover, despite the Pact, Collins continued his clandestine activities to undermine Northern Ireland. | |||

| In 1936 the British advocacy group - the ] characterized the USC as "nothing but the organised army of the Unionist party".<ref>Boyd, Andrew (1984), ''Northern Ireland: Who is to Blame?'', The Mercier Press Limited, Dublin, pg 57, ISBN 0 85342 708 9</ref> | |||

| Lynch and Collins in an attempt to set aside difference over the Treaty, selected officers from their own forces who had experience in guerilla-style operations during the Anglo-Irish War and sent them to the border and the North to advise local IRA units. This led to a series of determined attacks by the IRA against the police and Army: across the border at Londonderry and Tyrone, in the Glens of Antrim and the Mourne Mountains. <ref>A Testimony to Courage - the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 - 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0850528194 p. 4</ref> From May 17, 1922 – May 19, 1922 The IRA launched a series of attacks across Northern Ireland. The RIC barracks at Martinstown, Ballycastle and Cushendall in county Antrim, were attacked, but none were taken. IRA units in Belfast targeted commercial buildings and destroyed 80-90 buildings over the next two months. | |||

| During the ], the USC was mobilised to serve in Britain's ], which unusually, was put under the command of the police rather than the British Army.{{sfnp|Steffens|2007|page=5}} | |||

| According to John Potter historian of the USC, the homes of prominent Unionists were burned down, patrols of RIC and Army ambushed, communication lines cut and barracks attacked. An attack on a Protestant funeral he says in Belfast led to a gun battle between the Army and the IRA which lasted for two weeks. <ref>A Testimony to Courage - the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 - 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0850528194 p. 4</ref> On May 28, an IRA unit of 100 men occupied ], just on the Northern side of the border. A gun battle broke out between them and 100 Ulster Special Constables, in which one USC man was killed. A battalion of British troops and an artillery battery of six field guns was mobilised to dislodge the IRA party. The British troops eventually dislodged the IRA force on June 3, seven IRA men were killed along with one British soldier, six were wounded and four were captured. Another 50 IRA men were later taken prisoner <ref>Michael Hopkinson, Green against Green, p82-87 </ref>. | |||

| == 1950s – IRA Border Campaign == | |||

| The USC was implicated in a number of attacks on Catholics in reprisal for IRA actions. For example on 24 March 1922, following the killing of two constables the previous day in central Belfast, Specials entered the home of a Belfast Catholic publican (Owen McMahon), they took him, his 5 sons and a barman lined them against a wall in the living room and shot them, 2 sons survived (the ]).<ref>The Thin Green Line - The History of the Royal Ulster Constabulary GC, Richard Doherty, published by Pen & Sword Books - ISBN 1-84415058-5 p18</ref><ref>''Northern Ireland: The Orange State'' (1976) ISBN 0-902818-87-2</ref> On March 1922, after the destruction of a bridge by the IRA in South Londonderry the Specials from No.14 Platoon Magherafelt, rounded up 20 Catholics and forced them to act as labourers.<ref name="Wallace Clark 1967, p. 58">Wallace Clark, ''Guns In Ulster'',(RUC) Constabulary Gazette, Belfast 1967, p. 58</ref> On May 2, 1922 The IRA launched a series of attacks on RIC barracks in counties Londonderry and Tyrone. Six RIC and USC men were killed in the attacks. In reprisal for the attacks, Ulster Special Constabulary personnel killed nine Catholic civilians in the area, two on May 6, three in ] on May 11, and four more in ] on May 19. | |||

| Between 1956 and 1962, the Special Constabulary was again mobilised to combat a ]. | |||

| Damage to property during this period was £1 million and the overall cost of the campaign was £10 million to the UK exchequer.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.royalulsterconstabulary.org/history3.htm |title=Royal Ulster Constabulary<!-- Bot generated title --> |access-date=24 April 2004 |archive-date=5 August 2004 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040805144856/http://www.royalulsterconstabulary.org/history3.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> Historian ] said of the USC, "The B Specials were the rock on which any mass movement by the IRA in the North has inevitably floundered."{{sfnp|Coogan|2000|page=37}} Six RUC and eleven IRA men (but no Special Constables) were killed in this campaign. | |||

| With the British Army withdrawing from Southern Ireland, very under-strength and increasingly reluctant to become involved, with the exception of major operation like the Pettigo assault. The burden fell according to Potter increasingly upon the RIC (later the RUC) which was also under-strength and in disarray. The job of counter-insurgency he says therefore fell to the Special Constabulary while the RIC/RUC dealt with civil disturbances. It has been argued that the fact that new state of Northern Ireland did not fall into a state of civil war was largely down to the efforts of the Specials.<ref name=Potter5>A Testimony to Courage - the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 - 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0850528194 p5</ref> Forty nine of them according to Potter had been killed during the period of the "Border War".<ref name=Potter5 /> However, it has equally been argued that the force acted a unionist militia during the period and was involved in widespread attack on Catholics in general. | |||

| The IRA called off their campaign in February 1962. | |||

| Hostilities along the border were largely ended by the Irish Civil War, which broke out in Dublin on June 28 1922. This caused the abandonment of republican attacks on Northern Ireland and eventually saw the suppression of the IRA in the Irish Free State. | |||

| == |

==1969 deployment== | ||

| The USC were deployed in 1969 to support the RUC in the ]. The B Specials' role in these events led to its disbandment the following year. | |||

| There were occasions when the Special Constabulary needed to turn out for duty. One such example is the 12th July period in Belfast in 1931 when sectarian rioting broke out. According to Potter, the B Men were tasked to relieve the RUC from normal duties to allow them and the army to deal with the disturbances.<ref name=Potter5 /> | |||

| Northern Ireland had been destabilised by disturbances arising out of the ]'s agitation for equal rights for Catholics. The USC were mobilised when the regular RUC were overstretched by riots in ] (known as the ]). The NICRA called for protests elsewhere to support those in Derry, leading to the violence spreading throughout Northern Ireland, especially in Belfast. | |||

| == 1950s and 1960s == | |||

| {{Refimprovesect|date=December 2008}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Damage to property during this period was £l million and the overall cost of the campaign was £10 million to the UK exchequer.<ref>http://www.royalulsterconstabulary.org/history3.htm</ref> ], the Irish historian, said at the time of the USC, "The B Specials were the rock on which any mass movement by the IRA in the North has inevitably floundered."<ref>''The I.R.A.'' (Fully revised and updated, paperback 2000), ], ], ISBN 0006531555, p. 37</ref> | |||

| The General Officer Commanding of the |

The USC were largely held in reserve in July and only hesitantly committed in August.<ref>Scarman 3.14</ref> The General Officer Commanding of the ] in Northern Ireland refused to allow the Army to become involved until the Belfast administration has used "all the forces at its disposal". This meant that the B Specials had to be deployed, although they were not trained or equipped for public order situations.{{sfnp|Potter|2001|page= 10}} The unsuitability of the use of the B Specials in such situations was clear: "The 'Specials', untrained for such a job, contained no Catholic members, were inevitably regarded as sectarian, and their presence tended to heighten rather than lower tension in Catholic areas."<ref>Harkness, David (1983), ''Northern Ireland Since 1920'', Helicon Limited, Dublin, pg 158.</ref> In August 1969 the ] ] issued a statement saying that his men were deployed in Belfast in a defensive capacity protecting Catholics who had been "terrorized by mobs backed by armed B-Specials." Goulding also stated that British troops would be in a "very perilous situation" until the B-Specials were disarmed and disbanded.<ref>Mansbach, Richard (1973), ''Northern Ireland: Half a Century of Partition'', Facts on File, Inc, New York, pgs 56-57, ISBN 0-87196-182-2</ref> | ||

| The two main centres of disturbance were in Belfast and Derry. A total of 300 Special Constables were also mobilised into the RUC during the disturbances. Some Constables were used to restrain a Protestant crowd in Derry, but others in this area joined in an exchange of petrol bombs and missiles with a Catholic crowd while another group led an attack on the Rossville Street area of the Catholic ] on 12 August.<ref>Scarman 3.18</ref><ref>Scarman 3.24</ref> | |||

| Lord Scarman blamed this apparent indiscriminate use of firearms by the Specials as the result of "panic" by the B Men and a "lack of police leadership." | |||

| In Belfast, the USC were successful in restoring order in the predominantly Protestant Shankill area, where they performed their patrol duties unarmed. On one occasion, the ] Platoon was petrol-bombed by a hostile Protestant crowd at Inglis's bakery as it tried to protect Catholics who were going to work. They also successfully protected Catholic owned public houses in the area, many of which were looted after they were withdrawn.<ref>Scarman 3.15–3.16</ref> However, on 14 August they did not hold back Protestants who attacked the Catholic Dover and Percy streets in the Falls/Divis district, and instead "fought back" Catholics there.<ref>Scarman Report 3.16–3.23</ref> | |||

| Coming between the two factions Scarman notes that the presence of Specials had a calming effect on the Protestant mob (whilst having the opposite effect on Catholic crowds) on most occasions but in several incidents Protestant rioters broke through USC cordons to attack opposing Catholics leaving the poorly-trained B Men unable to control them and, in the confusion, it looked as if the B Specials were aiding the Protestant mob, something which was later discounted by Lord Scarman.<ref>http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm#2</ref> | |||

| ===USC shootings=== | |||

| After the Army had been brought in to restore order, the Specials were tasked to patrol only Protestant areas Potter writes, which brought them into conflict with that community as part of their specific tasking was to guard the homes and businesses of Catholics. On one occasion he records, the Comber Platoon was petrol-bombed by a hostile crowd at Inglis's bakery as it tried to protect Catholics who were going to work. In other areas he says, such as Enniskillen and Newry, the use of the Specials to restore order under competent supervision by the police and equipped with proper riot gear proved to be a success. When ] the ] of the ] decided he must take action and moved troops up to the border, platoons of Specials were deployed to guard border police stations according to Potter.<ref>A Testimony to Courage - the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 - 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0850528194 p. 10</ref> | |||

| The USC's most controversial conduct in the 1969 riots came in provincial towns, where the Special Constabulary formed the main response to the rioting. The Specials, who were armed and not trained for riot duty, used deadly force on a number of occasions.<ref>Scarman Report 3.20</ref> | |||

| The USC shot and wounded a number of people in ] and ]. In ], they killed one and wounded two. In the following Scarman Tribunal, the findings said ''"...the Tribunal has been at a loss to find any explanation for the shooting, which it is satisfied was a reckless and irresponsible thing to do."''<ref name="Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 - Report of Tribunal of Inquiry">{{cite web | url=http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm | title=Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 – Report of Tribunal of Inquiry | publisher=CAIN | access-date=26 July 2011 | archive-date=27 August 2011 | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110827142651/http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm | url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| After a meeting with the GOCNI Potter says the British Prime Minister ] announced that the B Specials would be "phased out of their current role". This caused political and public uproar in Northern Ireland he writes, but the Specials continued to carry out duties as before. According to Potter, the civil disturbance were orchestrated by ] in ], 250 Specials under Major Desmond Woods were drafted in and issued with riot batons and shields and merged with regular police patrols. In what has been described by Woods as "one of the most successful operations the Specials had ever carried out" Potter notes restored order with only "relatively minor trouble".<ref>A Testimony to Courage - the Regimental History of the Ulster Defence Regiment 1969 - 1992, Major John Furniss Potter, Pen & Sword Books Ltd, 2001, ISBN 0850528194 p. 11</ref> | |||

| When ], the ] of ], moved ] troops up to the border in response to the rioting, platoons of Specials were deployed to guard border police stations.{{sfnp|Potter|2001|page= 10}} | |||

| Arising out the disturbances, the British Prime Minister ] announced that the B Specials would be "phased out of their current role". The British Government commissioned three reports into the policing response to the 1969 riots. These ultimately led to the disbanding of the Ulster Special Constabulary. | |||

| ==Reports on the 1969 Deployments== | |||

| Following serious intercommunal disturbances and sectarian violence as a result of protest marches by Civil Rights groups and traditional Protestant parades such as Orange Order marches the British Government set up several enquiries to examine the causes and effects of civil disorder and in an attempt to find solutions to the problems which beset Northern Ireland. | |||

| ===The Cameron Report=== | ===The Cameron Report=== | ||

| Sir John Cameron |

Sir John Cameron was requested to submit a report on the disturbances in Northern Ireland.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron.htm#warrant |title=Cameron Report – Disturbances in Northern Ireland (1969), Chapters 1–9|access-date=30 August 2008 |archive-date=23 May 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170523123405/http://www.cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron.htm#warrant |url-status=live|work=CAIN Archive - Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland|publisher=Ark|via=University of Ulster}}</ref> | ||

| He found some evidence of cross-membership of the USC and loyalist paramilitary organisations. He reported that in ]'s ] (UPV), there was definite evidence of dual membership by Special Constables, of which he said "we consider highly undesirable and not in the public interest".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron2.htm#chap12 |title=Chapter 12 - The Cause of the Disorders|access-date=30 August 2008 |archive-date=1 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180601151429/http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron2.htm#chap12 |url-status=live|department=Cameron Report - Disturbances in Northern Ireland Chapters 10 to 16|work=CAIN Archive - Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland|publisher=Ark|via=University of Ulster}}</ref> He also remarked that although "recruitment is open to both Protestant and Roman Catholic: in practice we are in no doubt that it is almost if not wholly impossible for a Roman Catholic recruit to be accepted."<ref name=Cameron14>{{Cite web |url=http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron2.htm#chap14 |title=Chapter 14 - Actions of the Police |access-date=30 August 2008 |archive-date=1 June 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180601151429/http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron2.htm#chap14 |url-status=live|department=Cameron Report - Disturbances in Northern Ireland Chapters 10 to 16|work=CAIN Archive - Conflict and Politics in Northern Ireland|publisher=Ark|via=University of Ulster}}</ref> The Cameron Report described the B-Specials as "a partisan and paramilitary force recruited exclusively from Protestants."<ref>Farrell, (1976), pg 265</ref> | |||

| Cameron |

Cameron recommended that the purposes of the USC as a reserve civilian police force, as well as a counter-insurgency reserve, be properly made known in recruitment and training so that it would be more attractive to Catholics.<ref name=Cameron14/> | ||

| ===The Scarman Report=== | |||

| ''This very practical evidence of the distinction drawn in the public mind - among all sections - between the R.U.C. and the U.S.C. prompts the reflection that there is a certain implicit duality of function and purpose in the U.S.C. - that in part it is a reserve force available to deal with such emergencies as incursions and insurrectionary activities by the I.R.A. and its sympathisers or supporters, and in part is designed to provide a reserve or reinforcement for the R.U.C. in discharge of its ordinary duties in the maintenance of law and order and the detection and repression of crime. Were this duality overtly recognised in recruitment, training and use of police reserves, then there would seem no reason why in practice recruitment to the U.S.C. in its capacity as a civil reserve or to that section of it, should not offer the same attraction to Roman Catholic recruits as the regular R.U.C. - and so to this extent help to erase the boundaries of sectarian division.''<ref>http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron2.htm#chap14 item 184</ref> | |||

| ], in his report on the rioting, was critical of the RUC's senior officers and of the way the B Specials were deployed into areas of civil disturbance which they had no training to deal with, which in some occasions led to a worsening of the situation. He also pointed out that the B Specials were the only reserve available to the RUC and that he could see no other way of quickly reinforcing the over-stretched RUC in the circumstances. He praised the Specials where he felt it was due.{{sfnp|Doherty|2004}} | |||

| Scarman concluded in his report on the civil disturbance in the region in 1969 that: "''Undoubtedly mistakes were made and certain individual officers acted wrongly on occasions. But the general case of a partisan force co-operating with Protestant mobs to attack Catholic people is devoid of substance, and we reject it utterly.''"<ref name="cain.ulst.ac.uk">{{Cite web |url=http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm#5 |title=CAIN: Violence and Civil Disturbances in Northern Ireland in 1969 – Report of Tribunal of Inquiry <!-- Bot generated title --> |access-date=29 August 2008 |archive-date=27 August 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110827142651/http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm#5 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Lord Cameron's conclusions included condemnation of several parties including NICRA and the RUC but recognised that the root cause of the civil disturbance was a genuine sense of grievance felt by Catholics, young Catholics in particular Including:<ref>http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/cameron2.htm#chap16</ref> | |||

| *1) A rising sense of continuing injustice and grievance among large sections of the Catholic population in Northern Ireland, in particular in Londonderry and Dungannon, in respect of (i) inadequacy of housing provision by certain local authorities (ii) unfair methods of allocation of houses built and let by such authorities, in particular; refusals and omissions to adopt a 'points' system in determining priorities and making allocations (iii) misuse in certain cases of discretionary powers of allocation of houses in order to perpetuate Unionist control of the local authority. | |||

| *5) Resentment, particularly among Catholics, as to the existence of the Ulster Special Constabulary (the 'B' Specials) as a partisan and paramilitary force recruited exclusively from Protestants. | |||

| *(7) Fears and apprehensions among Protestants of a threat to Unionist domination and control of Government by increase of Catholic population and powers, inflamed in particular by the activities of the Ulster Constitution Defence Committee and the Ulster Protestant Volunteers, provoked strong hostile reaction to civil rights claims as asserted by the Civil Rights Association and later by the People's Democracy which was readily translated into physical violence against Civil Rights demonstrators. | |||

| *(12) What was originally a Belfast students' protest against police action in Londonderry on 5 October and support for the Civil Right movement was transformed into the People's Democracy - itself an unnecessary adjunct to the already existing and operative Civil Rights Association. People's Democracy provided a means by which politically extreme and militant elements could and did invite and incite civil disorder, with the consequence of polarising and hardening opposition to Civil Rights claims. | |||

| *(13) On the other side the deliberate and organised interventions by followers of Major Bunting and the Rev. Dr. Paisley, especially in Armagh, Burntollet and Londonderry, substantially increased the risk of violent disorder on occasions when Civil Rights demonstrations or marches were to take place, were a material contributory cause of the outbreaks ( violence which occurred after 5 October, and seriously hampered the police in their task of maintaining law and order, and of protecting members of the public in the exercise of their undoubted legal rights and upon their lawful occasions. | |||

| *(14) The police handling of the demonstration in Londonderry on 5 October 1968 was in certain material respects ill co-ordinated and inept. There was use of unnecessary and ill controlled force in the dispersal of the demonstrators, only a minority of whom acted in a disorderly and violent manner. The wide publicity given by press, radio and television to particular episodes inflamed and exacerbated feelings of resentment against the police which had been already aroused by their enforcement of the ministerial ban. | |||

| *(15) Available police forces did not provide adequate protection to People's Democracy marchers at Burntollet Bridge and in or near Irish Street, Londonderry on 4 January 1969. There were instances of police indiscipline and violence towards persons not associated with rioting or disorder on 4/ 5 January in Londonderry and these provoked serious hostility to the police, particularly among the Catholic population of Derry, and an increasing disbelief in their impartiality towards non-Unionists. | |||

| *(16) Numerical insufficiency of available police force especially in Armagh on 30 November 1968 and in Londonderry on 4/ 5 January 1969 and later on l9th/20 April prevented early and complete control and, where necessary, arrest of disorderly and riotous elements. | |||

| Scarman went on to criticise the Command and Control of the RUC for deploying armed Special Constables in areas where their very presence would "heighten tension", as he was in no doubt that they were "Totally distrusted by the Catholics, who saw them as the strong arm of the Protestant ascendancy".<ref name="cain.ulst.ac.uk"/> | |||

| ===The Scarman Report=== | |||

| ] theorised in his report about how and why various disturbances occurred and the reaction of the police force to them. He was critical of the RUC's senior officers and of the way the B Specials were deployed into areas of civil disturbance which they had no training to deal with, which in some occasions led to a worsening of the situation. He also pointed out that the B Specials were the only reserve available to the RUC and that he could see no other way of quickly reinforcing the under strength RUC in the circumstances. He did give praise to the Specials where he felt it was due.<ref>http://cain.ulst.ac.uk/hmso/scarman.htm#2</ref> Some salient points from the report are: | |||

| *3.7 There were, in our judgement, six occasions in the course of these disturbances when the police, by act or omission, were seriously at fault. | |||

| They were:- (points 1, 4, 5 & 6 omitted as they only pertain to the RUC) | |||

| *2) The decision by the County Inspector to put USC on riot control duty in the streets of Dungannon on 13 August without disarming them and without ensuring that there was an experienced police officer present and in command. | |||

| *(3) The similar decision of the County Inspector in Armagh on 14 August | |||

| Scarman concluded that it would have been very difficult for Catholics to gain membership in 1969, even if they had applied to join. | |||

| Some other points concerning the USC were: | |||

| *3.14 The effect of the difficulties and the instructions set out above was that the USC were largely held in reserve in July and only hesitantly committed in August. They were not used at all during the July disturbances in Derry but did appear on the streets of Dungiven on 13 July when a party of USC without provocation fired over the heads of a crowd emerging from the Castle ballroom. | |||

| *3.15 When in early August the Shankill riots exposed the weakness of the police when threatened by Protestant as well as Catholic rioting, the decision was taken to use the USC for patrol duties in the Shankill. They were successful in this predominantly Protestant area at a time when the RUC were not welcome -because of their firm action against the Protestant mobs at the beginning of the month. The USC performed their patrol duties unarmed. | |||

| *3.16 Until 14 August USC were also used in Belfast to protect licensed premises which, being largely Catholic owned and managed, were at risk from Protestant hooligans when communal tension was high. Again, they did the job well-as is evidenced by the destruction of so many public houses as soon as they were withdrawn. | |||

| *3.18 In Londonderry they appeared in some numbers at Waterloo Place and Bishop Street. They did not carry firearms. Their arrival in Waterloo Place caused consternation among the Catholics: but, in fact, they did little or nothing. In Bishop Street they were used to restrain a Protestant crowd in the Fountain. There is some evidence of special constables misbehaving themselves in this area by participating in an exchange of petrol bombs and missiles with a Catholic crowd. There is however nothing to justify any general criticism of the USC in the few hours that it performed riot duty on the streets of Derry. | |||

| *3.19 On 13 August USC, who had arrived to assist the hard-pressed police in Coalisland, fired without orders into a riotous crowd but were immediately ordered to stop, which they did. On the 14th in Dungannon and Armagh armed parties of USC opened fire on Catholic crowds, causing casualties, including one death at Armagh. | |||

| *3.20 In Coalisland there were extenuating circumstances, in as much as the police party was under severe pressure from a riotous mob which heavily out-numbered them. In Armagh, deprived of police leadership, USC personnel panicked, but there was no justification for firing into the crowd. In Dungannon, the Tribunal has been at a loss to find any explanation for the shooting, which it is satisfied was a reckless and irresponsible thing to do. As in Armagh, so also in Dungannon there was an absence of police leadership at the critical time. | |||

| *3.21 Their employment in Belfast on 14th revealed their helplessness in a communal disturbance. Instructed to hold back Protestants who attempted to penetrate down such streets as Dover and Percy streets into the Falls/Divis district, they failed. Confronted with a small Catholic mob moving up the Catholic end of Dover Street, they fought it back. The scale of the fighting increased, and became a sectarian riot, in which the USC had only an incidental part. In Percy Street some members of the USC and some Protestant civilians co-operated in trying to drive a Catholic crowd back to Divis Street. When eventually Protestants erupted into Divis Street they stood about helplessly while their presence convinced the Catholics that "the Bs" were spearheading the assault. | |||

| *3.22 There is no evidence that the USC, who were used to hold back Protestants in the Disraeli Street area, participated in the rioting inside the Ardoyne. | |||

| *3.23 In reviewing the conduct of the USC it is necessary to distinguish between Belfast and the rest of the Province. When USC were used for riot control duty outside Belfast they showed on several occasions a lack of proper discipline, particularly in the use of firearms. But in Belfast on 14 August their presence in Dover Street and Percy Street, while evoking the hostility of the Catholics, was unable to restrain the aggression of the Protestants. | |||

| *3.24 A little-publicised but important contribution made by the USC to the events under review was by way of the mobilisation of some 300 of them into the RUC. About 80 of them had been mobilized for duty as members of the Reserve Force several months earlier. The Reserve Force led the "Rossville Street incursion" into the Bogside on 12 August and provided the armed Shorlands which were used in the Belfast riots. But there are no grounds for singling out mobilised USC as being guilty of misconduct. The incursion into the Bogside and the use of Browning machine-guns in Belfast were RUC, not USC, responsibilities. | |||

| ===The Hunt Report=== | ===The Hunt Report=== | ||