| Revision as of 10:09, 17 February 2009 view source220.225.75.147 (talk) →Lecturing tours in America, England← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:43, 9 January 2025 view source Harold the Sheep (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users6,787 editsm →Vedanta and yoga | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Indian Hindu monk and philosopher (1863–1902)}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Vivekananda|other uses|Swami Vivekananda (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{protection padlock|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| {{Use Indian English|date=October 2023}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=October 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox Hindu leader | {{Infobox Hindu leader | ||

| |name |

| name = Vivekananda | ||

| | honorific prefix = ] | |||

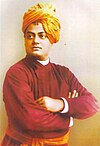

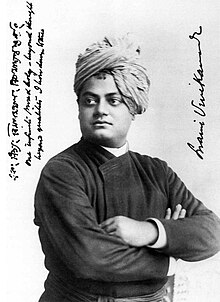

| |image= Swami Vivekananda-1893-09-signed.jpg | |||

| | image = Swami Vivekananda-1893-09-signed.jpg | |||

| |caption= <small> Swami Vivekananda in ], 1893 <br> | |||

| | alt = Black and white image of Vivekananda, facing left with his arms folded and wearing a turban | |||

| On the photo, Vivekananda has written in Bengali, and in English: “One infinite pure and holy—beyond thought beyond qualities I bow down to thee” - Swami Vivekananda </small> | |||

| | caption = Vivekananda in Chicago, September 1893. In note on the left Vivekananda wrote: "One infinite pure and holy – beyond thought beyond qualities I bow down to thee".<ref name="World fair 1893 circulated photo">{{cite web|title=World fair 1893 circulated photo|url=https://vivekananda.net/photos/1893-1895TN/pages/chicago-1893-september-harrr.htm|publisher=vivekananda.net|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231224201648/https://vivekananda.net/photos/1893-1895TN/pages/chicago-1893-september-harrr.htm |access-date=6 October 2024|archive-date=24 December 2023 }}</ref> | |||

| |birth-date= {{birth date|1863|1|12|df=y}} | |||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1863|01|12|df=y}} | |||

| |birth-place= ], ], ] | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] <br>(present-day ], ], ]) | |||

| |birth-name= Narendranath Dutta | |||

| | birth_name = Narendranath Datta | |||

| |death-date= {{death date and age|1902|7|4|1863|1|12|df=y}} | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|1902|7|4|1863|1|12|df=y}} | |||

| |death-place= ] near ] | |||

| | death_place = ], ], ] <br>(present-day ], ]) | |||

| |guru= ] | |||

| | alma_mater = ] (]) | |||

| |philosophy= | |||

| | guru = ] | |||

| |honors= | |||

| | disciples = {{hlist|]|]|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| |quote = Arise, awake; and stop not till the goal is reached.<ref>''Aspects of the Vedanta'', p.150</ref> | |||

| | citizenship = ] | |||

| |footnotes= | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| | school = {{hlist|]|]}} | |||

| | lineage = ] | |||

| | philosophy = ]<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.vedanta.gr/wp-content/uploads/2012/03/SwBhajan_4BasicPrincAdvVed_ENA4.pdf|title=Bhajanānanda (2010), ''Four Basic Principles of Advaita Vedanta'', p.3|access-date=28 December 2019}}</ref>{{sfn|De Michelis|2005}}<br>]{{sfn|De Michelis|2005}} | |||

| | founder = {{ubl|] (1897)|]}} | |||

| | literary_works = {{ubl|'']''|'']''|''Bhakti Yoga''|'']''|'']''|'']''}} | |||

| | signature = Swami Vivekananda's signature (as Narendra Nath Datta).png | |||

| | era = ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | region = ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| | native_name = স্বামী বিবেকানন্দ | |||

| | influences = {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Swami Vivekananda''' ({{lang-bn|স্বামী বিবেকানন্দ}}, ''Shami Bibekānondo''; {{lang-hi|स्वामी विवेकानन्द}}, ''Svāmi Vivekānanda'') (], ]–], ]), born '''Narendranath Dutta'''<ref name="Jestice"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Jestice | |||

| | first = Phyllis G. | |||

| | title = Holy People of the World | |||

| | publisher = ABC-CLIO | |||

| | date = 2004 | |||

| | pages = 899 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{quote box | |||

| </ref> is the chief disciple of the 19th century mystic ] and the founder of ].<ref name="Feuerstein"> | |||

| | title = Quotation | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | quote="]"<br />(] on ]) | |||

| | last = Georg | |||

| | width = 27em | |||

| | authorlink = Georg Feuerstein | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = The Yoga Tradition | |||

| | publisher = Motilal Banarsidass | |||

| | date = 2002 | |||

| | location = | |||

| | page = 600 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Swami Vivekananda'''{{efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|s|w|ɑː|m|i|_|ˌ|v|ɪ|v|eɪ|ˈ|k|ɑː|n|ə|n|d|ə}}; {{langx|bn|স্বামী বিবেকানন্দ}}; {{IPA|bn|ʃami bibekanɔndo|pron}}; {{audio|Swami Vivekananda.ogg|listen}}; ]: ''Svāmī Vivekānanda''}} (12 January 1863 – 4 July 1902), born '''Narendranath Datta'''{{efn|{{langx|bn|নরেন্দ্রনাথ দত্ত}}; {{IPA|bn|nɔrendronatʰ dɔto|pron}}}} was an Indian ] monk, philosopher, author, religious teacher, and the chief disciple of the Indian mystic ].<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.oneindia.com/feature/swami-vivekananda-a-short-biography-1980622.html |title=Swami Vivekananda: A short biography |work=www.oneindia.com |access-date=3 May 2017}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.culturalindia.net/reformers/vivekananda.html |title=Life History & Teachings of Swami Vivekanand |access-date=3 May 2017}}</ref> He was a key figure in the introduction of ] and ] to the Western world.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://indianexpress.com/article/research/international-yoga-day-2017-how-swami-vivekananda-helped-popularise-the-ancient-indian-regimen-in-the-west-4715411/|title=International Yoga Day: How Swami Vivekananda helped popularise the ancient Indian regimen in the West|date=21 June 2017}}</ref>{{sfn|Feuerstein|2002|p=600}}<ref>{{cite book |last=Syman |first=Stefanie |title=The Subtle Body: The Story of Yoga in America |title-link=The Subtle Body |year=2010 |publisher=] |location=New York |isbn=978-0-374-23676-2 |page=59}}</ref> He is credited with raising ] awareness and bringing ] to the status of a major world religion in the late ].{{Sfn|Clarke|2006|p=209}} | |||

| </ref> Vivekananda was the Hindu missionary to the West.<ref name="prl"/> He is considered a key figure in the introduction of ] and ] in ] and ]<ref name="Feuerstein"/> and is also credited with raising interfaith awareness, bringing ] to the status of a world religion during the end of 19th Century.<ref name="clarke"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Clarke | |||

| | first = Peter Bernard | |||

| | title = New Religions in Global Perspective | |||

| | publisher = Routledge | |||

| | date = 2006 | |||

| | page = 209 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Vivekananda is considered to be a major force in the ] of ] in modern India.<ref name="prl"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Von Dehsen | |||

| | first = Christian D. | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = Philosophers and Religious Leaders | |||

| | publisher = Greenwood Publishing Group | |||

| | date = 1999 | |||

| | page = 191 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> He is best known for his inspiring speech beginning with "sisters and brothers of America",<ref> | |||

| {{Citation | |||

| | last = Vivekananda | |||

| | first = Swami | |||

| | author-link = Swami Vivekananda | |||

| | title = Response to Welcome | |||

| | place = Parliament of Religions, Chicago | |||

| | year = 11th September, 1893 | |||

| | url = http://en.wikisource.org/The_Complete_Works_of_Swami_Vivekananda/Volume_1/Addresses_at_The_Parliament_of_Religions/Response_to_Welcome | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref><ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | author = Harshvardhan Dutt | |||

| | title = Immortal Speeches | |||

| | page = 121 | |||

| | date = 2005 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> through which he introduced Hinduism at the ] at Chicago in 1893.<ref name="Jestice"/> | |||

| Born into an aristocratic ] family in ], Vivekananda was inclined from a young age towards religion and spirituality. At the age of 18 he met Ramakrishna, later becoming a devoted follower and '']'' (renunciate). After the ], Vivekananda toured the ] as a wandering monk and acquired first-hand knowledge of the often terrible living conditions of Indian people in then ]. In 1893 he traveled to the United States where he participated in the ] in ]. Here he delivered a famous speech beginning with the words: "Sisters and brothers of America ..." introducing the ancient Hindu religious tradition to Americans and speaking forcefully about the essential unity of all spiritual paths, and the necessity of embracing tolerance and renouncing fanaticism.<ref>{{cite book |last= Barrows |first= John Henry |date= 1893|title= The World's Parliament of Religions |publisher= The Parliament of Religions Publishing Company|page=101}}</ref>{{Sfn|Dutt|2005|p=121}} The speech made an extraordinary impression. One American newspaper described him as "an orator by divine right and undoubtedly the greatest figure at the Parliament".<ref>{{cite news|title=Sisters and brothers of America — full text of Swami Vivekananda's iconic Chicago speech|publisher=The Print|url=https://theprint.in/india/sisters-and-brothers-of-america-full-text-of-swami-vivekanandas-iconic-chicago-speech/257916/|date=4 July 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Swami Vivekananda was born in an aristocratic family of Calcutta in 1863. His parents influenced the Swami's thinking—the father by his rational mind and the mother by her religious temperament. From his childhood, he showed inclination towards spirituality and God realization. While searching for a man who could directly demonstrate the reality of God, he came to Ramakrishna and became his disciple. As a guru Ramakrishna taught him '']'' and that all religions are true, and service to man was the most effective worship of God. After the death of his Guru, he became a wandering monk touring the Indian subcontinent and getting a first hand account of India's condition. He later sailed to Chicago and represented India as a delegate in the 1893 Parliament of World religions. An eloquent speaker, Vivekananda was invited to several forums in United States and spoke at universities and clubs. He conducted several public and private lectures, disseminating ], ] and ] in America, England and few other countries in Europe. He also established ] in America and England. He later sailed back to India and in 1897 he founded the Ramakrishna Math and Mission, a philanthropic and spiritual organization. The Swami is regarded as one of India's foremost nation-builders. His teachings influenced the thinking of other national leaders and philosophers, like ], ], ], ], ].<ref name="Jestice"/><ref name="prl"/><ref name="sn">{{cite journal|last=Nikhilananda|first=Swami|date=April 1964|title=Swami Vivekananda Centenary|journal=Philosophy East and West|publisher=University of Hawai'i Press|volume=14|issue=1|pages=73-75|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/1396757}}</ref> | |||

| After the great success of the Parliament, Vivekananda delivered hundreds of lectures across the ], ], and ], disseminating the core tenets of ]. He founded the ] and the Vedanta Society of San Francisco (now ]),{{sfn|Jackson|1994|p=115}} which became the foundations for ] in the West. In India, he founded the ], which provides spiritual training for monastics and householders, and the ], which provides charity, social work and education.{{sfn|Feuerstein|2002|p=600}} | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| === Birth and Childhood === | |||

| ] | |||

| Swami Vivekananda was born in Shimla Pally, Calcutta at 6:33 a.m on Monday, 12 January 1863,<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda: By his eastern and western disciples|publisher=Advaita Ashrama|date=July 2006|edition=Sixth|page=11|quote=It was the last day of the ninth Bengali month Poush, known as ] day—a great Hindu festival.}}</ref> and was given the name Narendranath Datta.<ref>{{cite book | author = Swami Chetanananda | title = God lived with them | page = 20 | chapter = Swami Vivekananda }}</ref> His father Vishwanath Datta was an ] of ]. He was considered generous, and had a progressive outlook in social and religious matters. His mother Bhuvaneshwari Devi was pious and had practiced austerities and prayed to ''] ]'' of ] to give her a son. She reportedly had a dream in which Shiva rose from his ] and said that he would be born as her son.<ref>{{cite book|title=The Life of Swami Vivekananda|publisher=]|date=1979|page=11}}</ref> | |||

| Vivekananda was one of the most influential ] and ]s in his contemporary India, and the most successful missionary of ] to the ]. He was also a major force in contemporary ] and contributed to the concept of ] in ].{{Sfn|Von Dense|1999|p=191}} He is now widely regarded as one of the most influential people of modern India and a patriotic ]. His birthday is celebrated in India as ].<ref>{{Cite web|date=11 January 2022|title=Know About Swami Vivekananda on National Youth Day 2022|url=https://news.jagatgururampalji.org/national-youth-day/|access-date=12 January 2022|website=SA News Channel|language=en-US}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|date=12 January 2022|title=National Youth Day 2022: Images, Wishes, and Quotes by Swami Vivekananda That Continue to Inspire us Even Today!|url=https://www.news18.com/news/lifestyle/national-youth-day-2022-images-wishes-and-famous-quotes-by-swami-vivekananda-that-continue-to-inspire-us-even-today-4645769.html|access-date=12 January 2022|website=News18|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| His thinking and personality were influenced by his parents—the father by his rational mind and the mother by her religious temperament.<ref name="sn"/> During his early years he became familiar with Western philosophy and science, and refused to accept anything without rational proof and pragmatic test. Another part of his mind was drawn to the spiritual ideals of meditation and non-attachment.<ref name="sn"/> | |||

| ==Early life (1863–1888)== | |||

| Narendranath started his education at home, later he was admitted to Metropolitan Institution of ] in 1871 and in 1879 he passed the Entrance Examination.<ref>{{cite book|last=Banhatti|first=G.S.|title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Distributors|page=4|chapter=Childhood and early school-life}}</ref> He had varied interests and a wide range of scholarship in philosophy, history, the social sciences, arts, literature, and other subjects.<ref name="Tapan-628"/> He evinced much interest in scriptural texts, '']'', the '']'', '']'', '']'', '']'' and the '']''. He was also well versed in ], both vocal and instrumental. Since boyhood, he took an active interest in physical exercise, sports, and other organizational activities.<ref name="Tapan-628">{{cite book|last=Arrington|first=Robert L. |coauthors=Tapan Kumar Chakrabarti|title=A Companion to the Philosophers|publisher=Blackwell Publishing|date=2001|pages=628|chapter=Swami Vivekananda}}</ref> Even when he was young, he questioned the validity of superstitious customs and discrimination based on ] and religion.<ref name = "Early Years"></ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| Narendranath's mother played a very important role in his spiritual development. One of the sayings of his mother Narendra quoted often in his later years was, "Remain pure all your life; guard your own honor and never transgress the honor of others. Be very tranquil, but when necessary, harden your heart."<ref name="GLWT-p.20">{{cite book | author = Swami Chetanananda | title = God lived with them | page = 20 | chapter = Swami Vivekananda }}</ref> He reportedly was adept in meditation. He reportedly would see a light while falling asleep and he reportedly had a vision of ] during his ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Biswas|first=Arun Kumar |title=Buddha and Bodhisattva|publisher=Cosmo Publications|date=1987|page=19}}</ref> | |||

| | direction = horizontal | |||

| |total_width = 360 | |||

| | image1 = Bhuvaneshwari-Devi-1841-1911.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = Bhubaneswari Devi (1841–1911); "I am indebted to my mother for the efflorescence of my knowledge."{{Sfn|Virajananda |2006|p=21}} – Vivekananda | |||

| | alt1 = A Bengali woman, sitting | |||

| | image2 = Swami Vivekananda's Ancestral House & Cultural Centre Door - Kolkata 2011-10-22 6073.JPG | |||

| | caption2 = 3, Gourmohan Mukherjee Street, birthplace of Vivekananda, now converted into a museum and cultural centre | |||

| | alt2 = Vivekananda as a wandering monk | |||

| }} | |||

| === |

===Birth and childhood=== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| Narendranath entered the first year Arts class of ] in January 1880 and the next year he shifted to ]. During the course, he studied western ], ] and ]an nations.<ref name = "Early Years"/> In 1881 he passed the Fine Arts examination and in 1884 he passed the ].<ref name="college">{{cite book|title=The Life of Swami Vivekananda|edition=Sixth|volume=1|page=46|chapter=College Days}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Pangborn|first=Cyrus R.|coauthors=Bardwell L. Smith|title=Hinduism: New Essays in the History of Religions|publisher=Brill Archive|date=1976|page=106|chapter=The Ramakrishna Math and Mission|quote=Narendra, son of a Calcutta attorney, student of the intellectually most demanding subjects in arts and sciences at Scottish Church College}}</ref> | |||

| Vivekananda was born as Narendranath Datta (name shortened to Narendra or Naren){{Sfn|Paul|2003|p=5}} in a ] family{{sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=1}}<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SKKDBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA236|title=Rescued from the Nation: Anagarika Dharmapala and the Buddhist World|publisher=University of Chicago Press|year=2015|page=236|author=Steven Kemper|isbn=978-0-226-19910-8}}</ref> in his ancestral home at ] in Calcutta,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mid-day.com/articles/devdutt-pattanaik-dayanand--vivekanand/17911158|title=Devdutt Pattanaik: Dayanand & Vivekanand|date=15 January 2017}}</ref> the capital of British India, on 12 January 1863 during the ] festival.{{Sfn|Badrinath|2006|p=2}} He was one of nine siblings.{{Sfn|Mukherji|2011|p=5}} His father, ], was an attorney at the ].{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=1}}{{Sfn|Badrinath|2006|p=3}} Durgacharan Datta, Narendra's grandfather was a ] and ] scholar{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=4}} who left his family and became a monk at age twenty-five.{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=2}} His mother, Bhubaneswari Devi, was a devout housewife.{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=4}} The progressive, rational attitude of Narendra's father and the religious temperament of his mother helped shape his thinking and personality.{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1964}}{{Sfn|Sen|2003|p=20}} Narendranath was interested in spirituality from a young age and used to ] before the images of deities such as ], ], ], and ].{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=5}} He was fascinated by wandering ascetics and monks.{{Sfn|Sen|2003|p=20}} Narendra was mischievous and restless as a child, and his parents often had difficulty controlling him. His mother said, "I prayed to Shiva for a son and he has sent me one of his demons".{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=2}} | |||

| ===Education {{anchor|Early and college education}}=== | |||

| According to his professors, student Narendranath was a prodigy. Dr. William Hastie, the principal of Scottish Church College, where he studied during 1881-84, wrote, "Narendra is really a genius. I have travelled far and wide but I have never come across a lad of his talents and possibilities, even in German universities, among philosophical students."<ref name="dhar_53"> | |||

| In 1871, at the age of eight, Narendranath enrolled at Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar's ], where he went to school until his family moved to ] in 1877.{{sfn|Banhatti|1995|p={{page needed|date=August 2020}}}} In 1879, after his family's return to Calcutta, he was the only student to receive first-division marks in the ] entrance examination. {{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=4}} He was an avid reader in a wide range of subjects, including philosophy, religion, history, social science, art and literature.{{Sfn|Arrington|Chakrabarti|2001|pp=628–631}} He was also interested in ], including the ], the ], the ], the '']'', the '']'' and the ]. Narendra was trained in ],{{Sfn|Sen|2003|p=21}} and regularly participated in physical exercise, sports and organised activities. He studied Western logic, ] and ] at the ] (now known as the Scottish Church College).{{Sfn|Sen|2006|pp=12–14}} In 1881, he passed the ] examination, and completed a ] degree in 1884.{{Sfn|Sen|2003|pp=104–105}}{{Sfn|Pangborn|Smith|1976|p=106}} Narendra studied the works of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{Sfn|Dhar|1976|p=53}}{{Sfn|Malagi|Naik|2003|pp=36–37}} He became fascinated with the ] of ] and corresponded with him.{{Sfn|Prabhananda|2003|p=233}}{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|pp=7–9}} He translated Spencer's book '']'' (1861) into Bengali.{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=31}} While studying Western philosophers, he also learned Sanskrit scriptures and ].{{Sfn|Malagi|Naik|2003|pp=36–37}} | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Dhar | |||

| | first = Sailendra Nath | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda | |||

| | publisher = | |||

| | date = 1975 | |||

| | location = | |||

| | page = 53 | |||

| | url = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | id = | |||

| | isbn = }} | |||

| </ref> He was regarded as a ''srutidhara''—a man with prodigious memory.<ref>Swami Vivekananda By N.L. Gupta, p.2</ref><ref name="dhar_59"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Dhar | |||

| | first = Sailendra Nath | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | coauthors = | |||

| | title = A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda | |||

| | publisher = | |||

| | date = 1975 | |||

| | location = | |||

| | pages = 59 | |||

| | url = | |||

| | doi = | |||

| | id = | |||

| | isbn = }} | |||

| </ref> After a discussion with Narendranath, Dr. ] reportedly said, "I could never have thought that such a young boy had read so much!"<ref>{{cite book|last=Dutta|first=Mahendranath|title=Sri Sri Ramakrishner Anudhyan|editor=Dhirendranath Basu|edition=6th|page=89}}</ref> | |||

| ] (the principal of Christian College, Calcutta, from where Narendra graduated) wrote of him: "Narendra is really a genius. I have travelled far and wide but I have never come across a lad of his talents and possibilities, even in German universities, among philosophical students. He is bound to make his mark in life".<ref>{{cite book|title=Concise Encyclopaedia of India|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=9dNOT9iYxcMC&pg=PA1066|page=1066|editor1=K.R.Gupta|editor2=Amita Gupta|publisher=Atlantic|year=2006|isbn = 978-81-269-0639-0}}</ref> He was known for his prodigious memory and speed reading ability, and a number of anecdotes attest to this.{{sfn|Banhatti|1995 |pp=156, 157}} Some accounts have called Narendra a ''shrutidhara'' (a person with a prodigious memory).<ref>. ''India Today''. 4 July 2016.</ref> | |||

| From his childhood, he showed inclination towards spirituality, God realisation and realizing the highest spiritual truths. He studied different religious and philosophical systems of East and the West; he met different religious leaders. He came under the influence of the ], an important socio-religious organization of that time. His initial beliefs were shaped by Brahmo Samaj, which believed in formless God, deprecated the worship of idols and devoted itself to socio-religious reforms.<ref>{{cite book|last=Bhuyan|first= P. R. |title=Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Distributors|date=2003|page=5}}</ref> He met the leaders of Brahmo Samaj—] and ], questioning them about the existence of God, but he could not get convincing answers.<ref>{{cite book | author = Swami Chetanananda | title=God lived with them | chapter=Swami Vivekananda | page=22 | quote = He asked the Brahmo Samaj leader, ], "Sir, have you seen God?", for which Devendranath had no answer and replied, "My boy, you have the eyes of a yogi. You should practise meditation."}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Pangborn|first=Cyrus R.|coauthors=Bardwell L. Smith|title=Hinduism: New Essays in the History of Religions|publisher=Brill Archive|date=1976|page=106|chapter=The Ramakrishna Math and Mission|quote=He had tried the Brahmo Samaj in the hope that its leader—at that time, Keshab Chandra Sen—could lead him to the vision for which he yearned. | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ===Initial spiritual forays=== | |||

| Narendranath is said to have studied the writings of ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="Malagi-36-37">{{cite book|last=Malagi|first=R.A.|coauthors=M.K.Naik|title=Perspectives on Indian Prose in English|publisher=Abhinav Publications|date=2003|pages=36-37|chapter=Stirred Spirit: The Prose of Swami Vivekananda}}</ref><ref name="dhar_53"/> Narendra became fascinated with the ] of Herbert Spencer, and translated Spencer’s book on ''Education'' into Bengali for ], his publisher. Narendra also had correspondence with Herbert Spencer for some time.<ref name="Prabha-2003" /><ref>{{cite book|last=Banhatti|first=G.S.|title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Distributors|pages=7-9|chapter=Spiritual Apprenticeship|quote=Vivekananda is said to have offered, in a letter to Herbert Spencer, some criticism of the celebrated philosopher's speculations, which the aged stalwart is said to have appreciated.|quotes=no}}</ref> Alongside his study of Western philosophers, he was thoroughly acquainted with Indian Sanskrit scriptures and many Bengali works.<ref name="Malagi-36-37" /> | |||

| {{See also|Swami Vivekananda and meditation}} | |||

| In 1880, Narendra joined ]'s '']'', which was established by Sen after meeting ] and reconverting from Christianity to Hinduism.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=99}} Narendra became a member of a ] lodge "at some point before 1884"{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=100}} and of the ] in his twenties, a breakaway faction of the ] led by ] and ].{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=99}}{{sfn| Sen|2006|pp=12–14}}{{sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=8}}{{sfn|Badrinath|2006|p=20}} From 1881 to 1884, he was also active in Sen's ], which tried to discourage youths from smoking and drinking.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=99}} | |||

| His first introduction to ] occurred in a literature class, when he heard Principal Hastie lecturing on ]'s poem ''The Excursion'' and the poet's nature-].<ref> | |||

| {{cite news | |||

| | last = Joseph | |||

| | first = Jaiboy | |||

| | title = Master visionary | |||

| | language = English | |||

| | publisher = The Hindu | |||

| | date = 002-06-23 | |||

| | url = http://www.hinduonnet.com/thehindu/mag/2002/06/23/stories/2002062300310400.htm | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-10-09 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> In the course of explaining the word '']'' in the poem, Hastie told his students that if they wanted to know the real meaning of it, they should go to Ramakrishna of ]. This prompted some of his students, including Narendranath to visit Ramakrishna.<ref name="jm_pb"> | |||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last = Mukherjee | |||

| | first = Dr. Jayasree | |||

| | title = Sri Ramakrishna’s Impact on Contemporary Indian Society | |||

| | journal = Prabuddha Bharatha | |||

| | date = May 2004 | |||

| | url = http://www.eng.vedanta.ru/library/prabuddha_bharata/sri_ramakrishna%27s_impact_on_contemporary_indian_society_may04.php | |||

| | accessdate = 2008-09-04}} | |||

| </ref><ref>{{cite book | author = Swami Chetanananda | title = God lived with them | page = 22 | quote = Hastie said, 'I have known only one person, who has realized that blessed state, and he is Ramakrishna of Dakshineswar. You will understand it better if you visit this saint.'}}</ref> | |||

| It was in this cultic milieu that Narendra became acquainted with Western ].{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=19-90, 97–100}} His initial beliefs were shaped by Brahmo concepts, which denounced polytheism and caste restrictions,{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=5}}{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=29}} and proposed a "streamlined, rationalized, monotheistic theology strongly coloured by a selective and modernistic reading of the ''Upanisads'' and of the Vedanta."{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=46}} ], the founder of the Brahmo Samaj who was strongly influenced by ], strove towards a ] interpretation of Hinduism.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=46}} His ideas were "altered considerably" by Debendranath Tagore, who had a ] approach to the development of these new doctrines, and questioned central Hindu beliefs like reincarnation and karma, and rejected the authority of the ''Vedas''.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=46-47}} Tagore, and later Sen, also brought this "neo-Hinduism" closer in line with western ].{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=47}} Sen was influenced by ], an American philosophical-religious movement strongly connected with unitarianism, which emphasised personal ] over mere reasoning and ].{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=81}} Sen's focus on creating "an accessible, non-renunciatory, everyman type of spirituality" that introduced "lay systems of spiritual practice" was an influence on the teachings Vivekananda later popularised in the west.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=49}} | |||

| ===With Ramakrishna=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Not satisfied with his knowledge of philosophy, Narendra came to "the question which marked the real beginning of his intellectual quest for God."{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=8}} He asked several prominent Calcutta residents if they had come "face to face with God", but none of their answers satisfied him.{{sfn|Sen|2006|pp=12–13}}{{sfn|Pangborn|Smith|1976|p=106}} At this time, Narendra met Debendranath Tagore (the leader of Brahmo Samaj) and asked if he had seen God. Instead of answering his question, Tagore said, "My boy, you have the '']''{{'}}s eyes."{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=8}}{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=31}} According to Banhatti, it was Ramakrishna who first truly answered Narendra's question, by saying "Yes, I see Him as I see you, only in an infinitely intenser sense."{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=8}} De Michelis, however, suggests that Vivekananda was more influenced by the Brahmo Samaj and its new ideas than by Ramakrishna.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=49}} According to De Michelis, it was Sen's influence that brought Vivekananda fully into contact with western esotericism, and it was via Sen that he met Ramakrishna.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=50}} Swami Medhananda agrees that the Brahmo Samaj was a formative influence,{{sfn|Medhananda|2022|p=17}} but affirms that "it was Narendra's momentous encounter with Ramakrishna that changed the course of his life by turning him away from Brahmoism."{{sfn|Medhananda|2022|p=22}} | |||

| {{Quote box|quote=<small>"The magic touch of the Master that day immediately brought a wonderful change over my mind. I was astounded to find that really there was nothing in the universe but God! … everything I saw appeared to be Brahman. … I realized that I must have had a glimpse of the '']'' state. Then it struck me that the words of the scriptures were not false. Thenceforth I could not deny the conclusions of the ''Advaita'' philosophy."</small>|width=20%|align=right|source=<small>Vivekananda on his acceptance of '']''.<ref>{{cite book|last=Mannumel|first=Thomas |title= The Advaita of Vivekananda: A Philosophical Appraisal|page=17}}</ref></small> }} | |||

| ===Meeting Ramakrishna=== | |||

| His meeting with ] in November 1881 proved to be a turning point in his life.<ref name="Prabha-2003">{{cite journal|last=Prabhananda|first=Swami |date=June 2003|title=Swami Vivekananda|journal=Prospects|publisher=], ]|volume=XXXIII|issue=2|url=http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/vivekane.pdf}}</ref> About | |||

| this meeting, Narendranath said, "He looked just like an ordinary man, | |||

| with nothing remarkable about him. He used the most simple language and | |||

| I thought 'Can this man be a great teacher?'– I crept near to him and asked him the question | |||

| which I had been asking others all my life: 'Do you believe in God, Sir?' 'Yes,' he replied. | |||

| 'Can you prove it, Sir?' 'Yes.' 'How?' 'Because I see Him just as I see you here, only in a much intenser sense.' | |||

| That impressed me at once. I began to go to that man, day after day, and I actually saw that religion | |||

| could be given. One touch, one glance, can change a whole life."<ref name="Prabha-2003"/><ref>{{cite book|last=Vivekananda|first=Swami|title=The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Advaita Ashrama|volume=4|pages=178-179|chapter=My Master|url=http://en.wikisource.org/The_Complete_Works_of_Swami_Vivekananda/Volume_4/Lectures_and_Discourses/My_Master}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Relationship between Ramakrishna and Swami Vivekananda}} | |||

| Even though Narendra did not accept Ramakrishna as his guru initially and revolted against his ideas, he was attracted by his personality and visited him frequently.<ref name="G.S.B-10-13">{{cite book|last=Banhatti|first=G.S. |title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Atlantic Publishers & Distributors|date=1995|pages=10-13|chapter=Realisation|quote= Vivekananda says, 'I had a curious education; I loved the man, but I hated all his ideas.'}}</ref> He initially looked upon on Ramakrishna's ecstasies and visions as, "mere figments of imagination",<ref name="Prabha-2003"/> "mere hallucinations".<ref name="rr_naren"> | |||

| {{See also|Swami Vivekananda's prayer to Kali at Dakshineswar}} | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| Narendra first met Ramakrishna in 1881. When Narendra's father died in 1884, Ramakrishna became his primary spiritual focus.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=101}} | |||

| | last = Rolland | |||

| | first = Romain | |||

| | title = The Life of Ramakrishna | |||

| | date = 1929 | |||

| | pages = pp.169-193 | |||

| | chapter = Naren the Beloved Disciple | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> As a member of Brahmo samaj, he revolted against idol worship and polytheism, and Ramakrishna's worship of Kali.<ref>{{cite book|last=Arora|first=V. K. |title=The social and political philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Punthi Pustak|date=1968|pages=p.4|chapter=Communion with Brahmo Samaj}}</ref> He even rejected the '']'' of identity with absolute as blasphemy and madness, and often made fun of the concept<ref name="rr_naren"/> | |||

| Narendra's introduction to Ramakrishna occurred in a literature class at General Assembly's Institution, when Professor William Hastie was lecturing on ]'s poem, '']''.{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=29}} While explaining the word "trance" in the poem, Hastie suggested that his students visit Ramakrishna of ] to understand the true meaning of trance. This prompted Narendra, among others in the class, to visit Ramakrishna.{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=43}}{{Sfn|Ghosh|2003|p=31}}{{Sfn|Badrinath|2006|p=18}} | |||

| Though Narendra could not accept Ramakrishna and his visions, he could not neglect him either. It had always been in Narendra's nature to test something thoroughly before he would accept it. He tested Ramakrishna, who never asked Narendra to abandon reason, and faced all of Narendra's arguments and examinations with patience—"Try to see the truth from all angles" was his reply.<ref name="G.S.B-10-13"/> During the course of five years of his training under Ramakrishna, Narendra was transformed from a restless, puzzled, impatient youth to a mature man who was ready to renounce everything for the sake of God-realization. In time, Narendra accepted Ramakrishna, and when he accepted, his acceptance was whole-hearted.<ref name="G.S.B-10-13"/> | |||

| They probably first met personally in November 1881,{{refn|group=note|The exact date of the meeting is unknown. Vivekananda researcher Shailendra Nath Dhar studied the ''Calcutta University Calendar of 1881—1882'' and found in that year, examination started on 28 November and ended on 2 December{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=30}}}} though Narendra did not consider this their first meeting, and neither man mentioned this meeting later.{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=43}} At the time, Narendra was preparing for his upcoming F. A. examination. ] accompanied him to ]'s house where Ramakrishna had been invited to deliver a lecture.{{Sfn|Badrinath|2006|p=21}} According to Makarand Paranjape, at this meeting Ramakrishna asked Narendra to sing. Impressed by his talent, he asked Narendra to come to Dakshineshwar.{{Sfn|Paranjape|2012|p=132}} | |||

| In 1885 Ramakrishna suffered from ] and he was shifted to Calcutta and later to ]. Vivekananda and his brother ] took care of Ramakrishna during this final days. His spiritual education under Ramakrishna continued here. At Cossipore, Vivekananda reportedly experienced '']''.<ref>{{cite book|last=Isherwood|first= Christopher |title=Meditation and Its Methods According to Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Vedanta Press|date=1976|page=20}}</ref> During the last days of Ramakrishna, Vivekananda and some of the other disciples received the ochre monastic robes from Ramakrishna, which formed the first monastic order of Ramakrishna.<ref> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | author = Cyrus R. Pangborn | |||

| | title = Hinduism: New Essays in the History of Religions | |||

| | chapter = The Ramakrishna Math and Mission | |||

| | page = 98 | |||

| }}</ref> Vivekananda was taught that service to men was the most effective worship of God.<ref name="sn"/><ref>{{cite book|last=Isherwood|first= Christopher |title=Meditation and Its Methods According to Swami Vivekananda|publisher=Vedanta Press|date=1976|page=20 | quote = He realized under the impact of his Master that all the living beings are the embodiments of the 'Divine Self'...Hence, service to God can be rendered only by service to man.}}</ref> It is reported that when Vivekananda, doubted Ramakrishna's claim of '']'', Ramakrishna reportedly said, "He who was ], He who was ], He himself is now Ramakrishna in this body."<ref name="life_sw_vol1"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | title = The Life of Swami Vivekananda : By His Eastern and Western Disciples | |||

| | publisher = Advaita Ashrama | |||

| | date = July 2006 | |||

| | volume = I | |||

| | location = Mayavati | |||

| | chapter = Cossipore and the Master | |||

| | page = 183 | |||

| | quote = Naren thought, "The Master has said many a time that he is an Incarnation of God. If he ''now'' says in the midst of the throes of death, in this terrible moment of human anguish and physical pain, 'I am God Incarnate', then I will believe." | |||

| }}</ref> During his final days, Ramakrishna asked Vivekananda to take care of other monastic disciples and in turn asked them to look upon Vivekananda as their leader.<ref name="rr_river"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | last = Rolland | |||

| | first = Romain | |||

| | title = The Life of Ramakrishna | |||

| | year = 1929 | |||

| | pages = 201–214 | |||

| | chapter = The River Re-Enters the Sea | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Ramakrishna's condition worsened gradually and he expired in the early morning hours of August 16, 1886 at the Cossipore garden house. According to his disciples, this was '']''.<ref name="rr_river"/> | |||

| Narendra went to Dakshineswar in late 1881 or early 1882 and met Ramakrishna.{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=43}} This meeting proved to be a turning point in his life.{{Sfn|Prabhananda|2003|p=232}} Although he did not initially accept Ramakrishna as his teacher and rebelled against his ideas, he was attracted by his personality and frequently visited him.{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|pp=10–13}} He initially saw Ramakrishna's ecstasies and visions as "mere figments of imagination"{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1964}} and "hallucinations".{{Sfn|Rolland|1929a| pp = 169–193}} As a member of Brahmo Samaj, he opposed idol worship, ], and Ramakrishna's worship of ].{{Sfn|Arora|1968|p=4}} He even rejected the ] teaching of "identity with the absolute" as blasphemy and madness, and often ridiculed the idea.{{Sfn|Rolland|1929a| pp = 169–193}} Ramakrishna was unperturbed and advised him: "Try to see the truth from all angles".{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|pp=10–13}} | |||

| === Baranagore Monastery === | |||

| After the death of their master, the monastic disciples lead by Vivekananda formed a fellowship at a half-ruined house at ] near the river ], with the financial assistance of the householder disciples. This became the first Math or ] of the disciples who constituted the first ].<ref name="Prabha-2003" /> | |||

| Narendra's father's sudden death in 1884 left the family bankrupt; creditors began demanding the repayment of loans, and relatives threatened to evict the family from their ancestral home. Once the son of a well-to-do family, Narendra became one of the poorest students in his college.<!--Ref verification needed-->{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=8}} His attempts to find work were unsuccessful. He questioned God's existence,{{Sfn|Sil|1997|p=38}} but found solace in Ramakrishna, and his visits to Dakshineswar increased.{{Sfn|Sil|1997|pp=39–40}} | |||

| The dilapidated house at ] was chosen because of its low rent and proximity to the Cossipore burning-ghat, where Ramakrishna was cremated. Narendra and other members of the Math often spent their time in meditation, discussing about different philosophies and teachings of spiritual teachers including Ramakrishna, Shankaracharya, Ramanuja, and Jesus Christ.<ref name="GLWT_38">''God lived with them'', p.38</ref> Narendra reminisced about the early days in the monastery as follows, "We underwent a lot of religious practice at Baranagore Math. We used to get up at 3:00 am and become absorbed in '']m'' and meditation. What a strong spirit of dispassion we had in those days! We had no thought even as to whether the world existed or not"<ref name="GLWT_38"/> In the early part of 1887, Narendra and eight other disciples took formal monastic vows. Narendra took the name of Swami Vividishananda.<ref name="GLWT_39">''God lived with them'', p.39</ref> | |||

| One day, Narendra asked Ramakrishna to pray to the goddess Kali for his family's financial welfare. Ramakrishna instead suggested he go to the temple himself and pray. Narendra went to the temple three times, but did not pray for any kind of worldly necessities. He ultimately prayed for true knowledge and devotion from the goddess.{{Sfn|Kishore|2001|pp=23–25}}{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1953|pp=25–26}}{{Sfn|Sil|1997|p=27}} He gradually became ready to renounce everything for the sake of realising God, and accepted Ramakrishna as his ].{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|pp=10–13}} | |||

| === ''Parivrâjaka'' — Wandering monk === | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1885, Ramakrishna developed ]. He was transferred to Calcutta and then to a garden house in ]. Narendra and Ramakrishna's ] took care of him during his last days, and Narendra's spiritual education continued. At Cossipore, he experienced ''] ]''.{{Sfn|Isherwood|1976|p=20}} Narendra and several other disciples received ] robes from Ramakrishna, forming his first monastic order.{{Sfn|Pangborn|Smith|1976|p= 98}} He was taught that service to men was the most effective worship of God.{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1964}}{{Sfn|Isherwood|1976|p=20}} Ramakrishna asked him to take care of the other monastic disciples, and likewise asked them to see Narendra as their leader.{{Sfn|Rolland| 1929b| pp= 201–214}} Ramakrishna died in the early morning hours of 16 August 1886 in Cossipore.{{Sfn|Rolland| 1929b| pp= 201–214}}{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=17}} | |||

| In 1888, Vivekananda left the monastery as a ''Parivrâjaka''—the Hindu religious life of a wandering monk, "without fixed abode, without ties, independent and strangers wherever they go."<ref>{{cite book|last=Rolland|first=Romain|title=The Life of Vivekananda and the Universal Gospel|page=7|chapter=The Parivrajaka}}</ref> His sole possessions were a ''kamandalu'' (water pot), staff, and his two favorite books—'']'' and '']''.<ref>{{cite book|last=Dhar|first=Sailendra Nath |title=A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda|page=243}}</ref> Narendranath travelled the length and breadth of India for five years, visiting important centers of learning, acquainting himself with the diverse religious traditions and different patterns of social life.<ref name="G.Richards">{{cite book|last=Richards|first=Glyn |title=A Source-Book of Modern Hinduism |publisher=Routledge|date=1996|pages=77-78|chapter=Vivekananda}}</ref><ref name="bhuyan-12">{{cite book | author = P. R. Bhuyan | title = Swami Vivekananda | page = 12}}</ref> He developed a sympathy for the suffering and poverty of the masses and resolved to uplift the nation.<ref name="G.Richards"/><ref name="pilgrim">{{cite book|last=Rolland|first=Romain|title=The Life of Vivekananda and the Universal Gospel|pages=16-25|chapter=The Pilgrim of India}}</ref> Living mainly on ] or ], Narendranath traveled mostly on foot and railway tickets bought by his admirers whom he met during the travels. During these travels he gained acquaintance and stayed with scholars, ], ]s and people from all walks of life—]s, ]s, ]s, '']''s (low caste workers), Government officials.<ref name="pilgrim"/> | |||

| === |

===Founding of Ramakrishna Math=== | ||

| {{Main|Baranagar Math}} | |||

| In 1888, he started his journey from ]. At Varanasi, he met pandit and Bengali writer, ] and ], a famous saint who lived in a Shiva temple. Here, he also met Babu Pramadadas Mitra, the noted Sanskrit scholar, to whom the Swami wrote a number of letters asking his advice on the interpretation of the Hindu scriptures.<ref>''The Life of Swami Vivekananda'', pp.214-216</ref> | |||

| After Ramakrishna's death, support from devotees and admirers diminished. Unpaid rent accumulated, forcing Narendra and the other disciples to look for a new place to live.{{Sfn|Sil|1997|pp=46–47}} Many returned home, adopting a '']'' (family-oriented) way of life.{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=18}} Narendra decided to convert a dilapidated house at ] into a new ''math'' (monastery) for the remaining disciples. Rent for the Baranagar Math was low, and was raised by ''mādhukarī'' (holy begging). It became the first building of the ], the monastery of the ] of ].{{Sfn|Prabhananda|2003|p=232}} Narendra and other disciples used to spend many hours practicing ] and religious austerities every day.{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1953|p=40}} Narendra recalled the early days of practice in the monastery:{{Sfn|Chetananda|1997|p=38}} | |||

| After Varanasi he visited ], ], ], ], ] and ]. At ] he met Sharat Chandra Gupta, the station master who later became one of his earliest disciples as '']''.<ref>{{cite book|last=Rolland|first=Romain|title=The Life of Vivekananda and the Universal Gospel|pages=11-12|chapter=The Parivrajaka}}</ref><ref name="Banhatti-19-22">{{cite book|last=Banhatti|first=G.S. |title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|pages=19-22|chapter=The Vision of One India}}</ref> Between 1888-1890, he visited ], ]. From Allahabad, he visited Ghazipur where he met ], a ''Advaita Vedanta'' ascetic who spent most of his time spent in meditation.<ref>''The Life of Swami Vivekananda'', pp.227-228</ref> Between 1888-1890, he returned to Baranagore ''Math'' few times, because of ill health and to arrange for the financial funds when Balram Bose and Suresh Chandra Mitra, the disciples of Ramakrishna who supported the ''Math'' had expired.<ref name="Banhatti-19-22" /> | |||

| {{blockquote|We used to get up at 3:00 am and become absorbed in '']'' and meditation. What a strong spirit of detachment we had in those days! We had no thought even as to whether the world existed or not.}} | |||

| In 1887, Narendra compiled a Bengali song anthology named '']'' with Vaishnav Charan Basak. Narendra collected and arranged most of the songs in this compilation, but unfavourable circumstances prevented its completion.{{Sfn|Chattopadhyaya|1999|p=33}} | |||

| ==== The Himalayas ==== | |||

| In July 1890, accompanied by his brother monk, ], he continued his journey as a wandering monk and returned to the ''Math'' only after his visit to the West.<ref name="Banhatti-19-22" /><ref name="Himalayas" /> He visited, ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ]. During this travel, he reportedly had a vision of ], which seems to be reflected in the ''Jnana Yoga'' lectures he gave later in the West, "''The Cosmos''—'']'' and '']''". During these travels, he met his brother monks —], Saradananda, Turiyananda, Akhandananda, Advaitananda. They stayed at ] for few days where they passed their time in meditation, prayer and study of scriptures. In the end of January 1891, the Swami left his brother monks and journeyed to ] alone.<ref name="Himalayas">{{cite book|title=The Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=243-261|chapter=Wanderings in the Himalayas}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last=Rolland|first=Romain|title=The Life of Vivekananda|page=15|chapter=The Parivrajaka}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Monastic vows=== | ||

| In December 1886, the mother of one of the monks, Baburam, invited Narendra and his brother monks to ] village. In Antpur, on the Christmas Eve of 1886, the 23 year old Narendra and eight other disciples took formal monastic vows at the ].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.getbengal.com/details/bengals-village-where-swami-vivekananda-took-sanyas | title=Aatpur – Bengal's village where Swami Vivekananda took Sanyas }}</ref>{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1953|p=40}} They decided to live their lives as their master lived.{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1953|p=40}} | |||

| At Delhi, after visiting historical places he journeyed towards ], in the historic land of ]. Later he journeyed to ], where he studied ]'s ''Ashtadhyayi'' from a Sanskrit scholar. He next journeyed to Ajmer, where he visited the palace of Akbar and the famous ] and left for ]. At Mount Abu, he met the ], who became his ardent devotee and supporter. He was invited to ], where delivered discourses to the Raja. At Khetri, he also became acquainted with Pandit Narayandas, and studied ''Mahabhashya'' on Sutras of Panini. After two and half months at Khetri, towards end of October 1891, he proceeded towards ] and ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=262-287|chapter=In Historic Rajputana}}</ref><ref name="pilgrim"/> | |||

| =={{anchor|As a monk wandering in India (1888–93)}}Travels in India (1888–1893)== | |||

| ==== Western India ==== | |||

| {{Main|Swami Vivekananda's travels in India (1888–1893)}} | |||

| Continuing his travels, he visited Ahmedabad, Wadhwan, Limbdi. At Ahmedabad he completed his studies of ] and ] culture.<ref name="pilgrim"/> At Limbdi, he met Thakore Sahed Jaswant Singh who had himself been to England and America. From the Thakore Saheb, the Swami got the first idea of going to the West to preach Vedanta. He later visited Junagadh, ], ], ], ], ], ]. At Porbander he stayed three quarters of a year, in spite of his vow as a wandering monk, to perfect his philosophical and Sanskrit studies with learned ''pandit''s; he worked with a court ''pandit'' who translated the '']s''.<ref name="pilgrim"/> | |||

| In 1888, Narendra left the monastery as a ''Parivrâjaka'' – a wandering monk, "without fixed abode, without ties, independent and strangers wherever they go".{{Sfn|Rolland|2008|p=7}} His sole possessions were a ] (water pot), staff and his two favourite books: the '']'' and '']''.{{Sfn|Dhar|1976|p=243}} Narendra travelled extensively in India for five years, visiting centres of learning and acquainting himself with diverse religious traditions and social patterns.{{Sfn|Richards|1996|pp=77–78}}{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p= 12}} He developed sympathy for the suffering and poverty of the people, and resolved to uplift the nation.{{Sfn|Richards|1996|pp=77–78}}{{Sfn|Rolland|2008|pp=16–25}} Living primarily on ] (alms), he travelled on foot and by railway. During his travels he met and stayed with Indians from all religions and walks of life: scholars, '']'', ]s, Hindus, Muslims, Christians, '']s'' (low-caste workers) and government officials.{{Sfn|Rolland|2008|pp=16–25}} On the suggestion of his patron, friend and disciple Raja ], he adopted the name "Vivekananda"–a conglomerate of the Sanskrit words: '']'' and '']'', meaning "the bliss of discerning wisdom". As Vivekananda he departed ] for Chicago, on 31 May 1893, intending to participate in the World's Parliament of Religions.{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=24}}{{Sfn|Gosling|2007|p=18}} | |||

| ==First visit to the West (1893–1897)== | |||

| He later traveled to ] and then to ]. From Poona he visited ] and ] around June 1892. At ] he heard of the ] and was urged by his followers there to attend it. He left Khandwa for Bombay and reached there on July 1892. In a ] bound train he met ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Rolland|first=Romain|title=The Life of Vivekananda and the Universal Gospel|page=25|chapter=The Pilgrim of India | quote=It was so at Poona in October, 1892 ; Tilak, the famous savant and Hindu political leader, took him at first for a wandering monk of no importance and began by being ironical; then, struck by his replies revealing his great mind and knowledge, he received him into his house for ten days without ever knowing his real name. It was only later, when the newspapers brought him from America the echoes of Vivekananda's triumph and a description of the conqueror, that he recognised the anonymous guest who had dwelt beneath his roof.}}</ref> After staying with Tilak for few days in Poona,<ref>{{cite book | author=Sailendra Nath Dhar | title=A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda | page=1434 | quote=Tilak recoded his impressions as follows, 'When asked about his name he only said he was a Sanyasin ....There was absolutely no money with him. A deerskin, one of two clothes and a ''Kamandalu'' were his only possessions.'}}</ref> the Swami travelled to ] in October 1892. At Belgaum, he was the guest of Prof. G.S. Bhate and Sub-divisional Forest officer, Haripada Mitra. From Belgaum, he visited ] and ] in Goa. He spent three days in the ], the oldest convent-college of theology of Goa where rare religious literature in manuscripts and printed works in ] are preserved. He reportedly studied important Christian theological works here.<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=288-320|chapter=In Western India}}</ref> From Margao the Swami went by train to ], and from there directly to ], in ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=321-346|chapter=Through South India}}</ref> | |||

| {{see also|Swami Vivekananda at the Parliament of the World's Religions}} | |||

| Vivekananda visited several cities in ] (including Nagasaki, Kobe, Yokohama, Osaka, Kyoto and Tokyo),{{Sfn|Paranjape | 2005 | pp = 246–248}} ] and ] en route to the United States,{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=15}} reaching Chicago on 30 July 1893.{{Sfn|Badrinath|2006|p=158}}{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=15}} The "]" took place in September 1893.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=110}} An initiative of the ] layman and Illinois Supreme Court judge ],<ref name="interfaith">{{Cite web|url=http://www.theinterfaithobserver.org/journal-articles/2012/6/15/charles-bonney-and-the-idea-for-a-world-parliament-of-religi.html|title=Charles Bonney and the Idea for a World Parliament of Religions|website=The Interfaith Observer|date=15 June 2012 |access-date=28 December 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://people.bu.edu/wwildman/bce/worldparliamentofreligions1893.htm|title=World Parliament of Religions, 1893 (Boston Collaborative Encyclopedia of Western Theology)|website=people.bu.edu|access-date=28 December 2019}}</ref> the Congress sought to gather all the religions of the world, with the aim of showing "the substantial unity of many religions in the good deeds of the religious life."<ref name="interfaith" /> The Brahmo Samaj and the ] were invited as representative of ].{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=112}} | |||

| Vivekananda wished to participate, but learned that only individuals with credentials from a '']'' organisation would be accepted as delegates.{{Sfn|Minor|1986|p=133}} Disappointed, he contacted Professor ] of ], who had invited him to speak at Harvard.{{Sfn|Minor|1986|p=133}} Vivekananda wrote of the professor: "He urged upon me the necessity of going to the ], which he thought would give an introduction to the nation".{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=16}} On hearing that Vivekananda lacked the credentials to speak at the Parliament, Wright said: "To ask for your credentials is like asking the sun to state its right to shine in the heavens".{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=16}} Vivekananda submitted an application introducing himself as a monk "of the oldest order of ''sannyāsis'' ... founded by Sankara".{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=112}} The application was supported by the Brahmo Samaj representative ], who was also a member of the Parliament's selection committee.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=112}} | |||

| ==== Southern India ==== | |||

| At Bangalore, the Swami became acquainted with Sir ], the ] of ], and later he stayed at the palace as guest of the Maharaja of Mysore, ]. Regarding Swami's learning, Sir Seshadri reportedly remarked, "a magnetic personality and a divine force which were destined to leave their mark on the history of his country." The Maharaja provided the Swami a letter of introduction to the Dewan of Cochin and got him a railway ticket.<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=323-325|chapter=Through South India}}</ref> | |||

| ===Parliament of the World's Religions=== | |||

| ], India ]] | |||

| From Bangalore, he visited ], ], ]. At Ernakulam, he met ], the guru of ] in early December 1892.<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=327-329|chapter=Through South India}}</ref> From Ernakulam, he journeyed to ], ] and reached ] on foot during the Christmas Eve of 1892.<ref>{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=339-342|chapter=Through South India}}</ref> At Kanyakumari, the Swami reportedly meditated on the "last bit of Indian rock", famously known later as the ] for three days.<ref>This view is supported by the evidence of two eyewitnesses. One of these was Ramasubba Iyer. In 1919, when ], a disciple of the Swamiji went on pilgrimage to Kanyakumari, Iyer told him that he had himself seen the Swami meditating on the rock for hours together, for three days consecutively ... Another eye-witness, Sadashivam Pillai, told that the Swami had remained on the rock for three nights and had seen him swim over to the rock. Next morning Pillai went to the rock with food for the Swami. There he found him meditating; and when Pillai asked him to return to the mainland, he refused. When he offered food to the Swami, the latter asked him not to disturb him. See, {{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=344-346|chapter=Through South India}}</ref> At Kanyakumari, Vivekananda reportedly had the "Vision of one India". He wrote, {{Blockquote|"At Cape Camorin sitting in Mother Kumari's temple, sitting on the last bit of Indian rock - I hit upon a plan: We are so many sanyasis wandering about, and teaching the people metaphysics-it is all madness. Did not our ''Gurudeva'' used to say, `An empty stomach is no good for religion?' We as a nation have lost our individuality and that is the cause of all mischief in India. We have to raise the masses."<ref>''Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda'', p.24</ref>}} | |||

| The Parliament of the World's Religions opened on 11 September 1893 at the ], as part of the ].{{Sfn|Houghton|1893|p=22}}{{Sfn|Bhide|2008|p=9}}{{Sfn|Paul|2003|p=33}} On this day, Vivekananda gave a brief speech representing India and ].{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=27}} He bowed to ] (the Hindu goddess of learning) and began his ] with "Sisters and brothers of America!".{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=17}}{{Sfn|Paul|2003|p=33}} At these words, Vivekananda received a two-minute standing ovation from the crowd of seven thousand.{{Sfn|Paul|2003|p=34}} When silence was restored he began his address, greeting the youngest of the nations on behalf of "the most ancient order of monks in the world, the Vedic order of sannyasins, a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance".{{sfn|McRae|1991|p=17}}{{refn|group=note |McRae quotes " sectarian biography of Vivekananda,"{{sfn|McRae|1991|p=16}} namely Sailendra Nath Dhar ''A Comprehensive Biography of Swami Vivekananda, Part One'', (Madras, India: Vivekananda Prakashan Kendra, 1975), p. 461, which "describes his speech on the opening day".{{sfn|McRae|1991|p=34, note 20}}}} Vivekananda quoted two illustrative passages from the "]": "As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take, through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee!" and "Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths that in the end lead to Me."{{sfn|McRae|1991|pp=18}} According to Sailendra Nath Dhar, "it was only a short speech, but it voiced the spirit of the Parliament."{{Sfn|McRae|1991|pp=18}}{{Sfn|Prabhananda|2003|p=234}} | |||

| From Kanyakumari he visited ], where he met Raja of ], Bhaskara Setupati, to whom he had a letter of introduction. The Raja became the Swami's disciple and urged him to go to the Parliament of Religions at Chicago. From Madurai, he visited ], ] and he travelled to Madras and here he met some his most devoted disciples, like Alasinga Perumal, G.G. Narasimhachari, who played important roles in collecting funds for Swami's voyage to America and later in establishing the Ramakrishna Mission in Madras. From Madras he travelled to Hyderabad. With the aid of funds collected by his Madras disciples and Rajas of Mysore, Ramnad, Khetri, Dewans, and other followers Vivekananda left for Chicago on 31 May, 1893 from Bombay assuming the name ''Vivekananda''—the name suggested by the Maharaja of Khetri.<ref>''Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda'', p.24</ref><ref name="madras">{{cite book|title=Life of Swami Vivekananda|pages=359-383|chapter=In Madras and Hyderabad}}</ref> | |||

| Parliament President ] said, "India, the Mother of religions was represented by Swami Vivekananda, the Orange-monk who exercised the most wonderful influence over his auditors".{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=17}} Vivekananda attracted widespread attention in the press, which called him the "cyclonic monk from India". The ''New York Critique'' wrote, "He is an orator by divine right, and his strong, intelligent face in its picturesque setting of yellow and orange was hardly less interesting than those earnest words, and the rich, rhythmical utterance he gave them". The '']'' noted, "Vivekananda is undoubtedly the greatest figure in the Parliament of Religions. After hearing him we feel how foolish it is to send ] to this learned nation".{{Sfn|Farquhar|1915|p = 202}} American newspapers reported Vivekananda as "the greatest figure in the parliament of religions" and "the most popular and influential man in the parliament".{{Sfn|Sharma|1988|p=87}} | |||

| ===First visit to the West=== | |||

| The '']'' reported that Vivekananda was "a great favourite at the parliament... if he merely crosses the platform, he is applauded".{{Sfn|Adiswarananda|2006|pp=177–179}} He spoke ] "at receptions, the scientific section, and private homes"{{sfn|McRae|1991|p=17}} on topics related to Hinduism, ] and harmony among religions. Vivekananda's speeches at the Parliament had the common theme of universality, emphasising religious tolerance.{{Sfn|Bhuyan|2003|p=18}} He soon became known as a "handsome oriental" and made a huge impression as an orator.{{Sfn|Thomas|2003|pp=74–77}} Hearing Vivekananda speak, Harvard psychology professor ] said, "that man is simply a wonder for oratorical power. He is an honor to humanity."<ref>{{cite web|title=When East Met West – in 1893|url=https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/2019/9/6/when-east-met-west-in-1893?rq=Vivekananda|website=The Attic|access-date=5 November 2019|archive-date=20 April 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200420050443/https://www.theattic.space/home-page-blogs/2019/9/6/when-east-met-west-in-1893?rq=Vivekananda|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| His journey to America took him through ], ], ] and he arrived at Chicago in July 1893.<ref>{{cite book | author = P. R. Bhuyan | title = Swami Vivekananda | page = 15}}</ref> But to his disappointment he learnt that no one without credentials from a '']'' organization would be accepted as a delegate. He came in contact with Professor ] of ].<ref name="wright">{{cite book|last=Minor|first=Robert Neil |title=Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavad Gita |publisher=SUNY Press|date=1986|page=133|chapter=Swami Vivekananda's use of the ''Bhagavad Gita''}}</ref> After inviting him to speak at Harvard and on learning of his not having credential to speak at the Parliament, Wright is quoted as having said, "To ask for your credentials is like asking the sun to state its right to shine in the heavens." Wright then addressed a letter to the Chairman in charge of delegates writing, "Here is a man who is more learned than all of our learned professors put together." On the Professor Vivekananda himself writes, "He urged upon me the necessity of going to the Parliament of Religions, which he thought would give an introduction to the nation."<ref>{{cite book | author = P. R. Bhuyan | title = Swami Vivekananda | page = 16}}</ref> | |||

| ==={{anchor|Lecturing tours in America and England}}Lecture tours in the UK and US=== | |||

| ====Parliament of World's Religions==== | |||

| ] | |||

| After the Parliament of Religions, Vivekananda toured many parts of the US as a guest. His popularity gave him an unprecedented opportunity to communicate his views on life and religion to great numbers of people.{{Sfn|Thomas|2003|pp=74–77}} During a question-answer session at Brooklyn Ethical Society, he remarked, "I have a message to the West as ] had a message to the East." On another occasion he described his mission thus:<blockquote>I do not come to convert you to a new belief. I want you to keep your own belief; I want to make the ] a better Methodist; the ] a better Presbyterian; the ] a better Unitarian. I want to teach you to live the truth, to reveal the light within your own soul.{{Sfn|Vivekananda|2001|p=419}}</blockquote> | |||

| The Parliament of Religions opened on 11 September 1893 at the ]. On this day Vivekananda gave his first brief address. He represented India and ].<ref>{{cite book|last=Banhatti|first=G.S. |title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|page=27|chapter=First Visit to the West|quote=Representatives from several countries, and all religions, were seated on the platform, including Mazoomdar of the ], Nagarkar of ], Gandhi representing the ]s, and Chakravarti and Mrs. ] representing ]. None represeted Hinduism, as such, and that mantle fell on Vivekananda.}}</ref> Though initially nervous, he bowed to '']'', the goddess of learning and began his ] with, "Sisters and brothers of America!".<ref name="wright"/><ref name="bhuyan-17">{{cite book | author = P. R. Bhuyan | title = Swami Vivekananda | page = 17}}</ref> To these words he got a standing ovation from a crowd of seven thousand, which lasted for two minutes. When silence was restored he began his address. He greeted the youngest of the nations in the name of "the most ancient order of monks in the world, the Vedic order of sannyasins, a religion which has taught the world both tolerance and universal acceptance."<ref name="McRae"/> And he quoted two illustrative passages in this relation, from the '']''—"As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take, through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to Thee!" and "Whosoever comes to Me, through whatsoever form, I reach him; all men are struggling through paths that in the end lead to Me."<ref name="McRae"/> Despite being a short speech, it voiced the spirit of the Parliament and its sense of universality.<ref name="McRae"/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Prabhananda|first=Swami |date=June 2003|title=Swami Vivekananda|journal=Prospects|publisher=], ]|volume=XXXIII|issue=2|url=http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/archive/publications/ThinkersPdf/vivekane.pdf | quote=His call for religious harmony and acceptance of all religions brought him great acclaim.}}</ref> | |||

| Vivekananda spent nearly two years lecturing in the eastern and central United States, primarily in ], ], ], and ]. He founded the ] of New York in 1894.{{Sfn|Gupta|1986|p=118}} His demanding schedule eventually began to affect his health,{{Sfn|Isherwood|Adjemian|1987|pp=121–122}} and in Spring 1895 he ended his lecture tours and began giving free, private classes in Vedanta and ]. Beginning in June 1895, he gave ] to a dozen of his disciples at ] for two months.{{Sfn|Isherwood|Adjemian|1987|pp=121–122}} Vivekananda was offered academic positions in two American universities (one the chair in ] at ] and a similar position at ]); he declined both, since his duties would conflict with his commitment as a monk.{{Sfn|Isherwood|Adjemian|1987|pp=121–122}} | |||

| Dr. Barrows, the president of the Parliament said, "India, the Mother of religions was represented by Swami Vivekananda, the Orange-monk who exercised the most wonderful influence over his auditors."<ref name="bhuyan-17"/> He attracted widespread attention in the press, which dubbed him as the "Cyclonic monk from India". The ''New York Critique'' wrote, "He is an orator by divine right, and his strong, intelligent face in its picturesque setting of yellow and orange was hardly less interesting than those earnest words, and the rich, rhythmical utterance he gave them." The '']'' wrote, "Vivekananda is undoubtedly the greatest figure in the Parliament of Religions. After hearing him we feel how foolish it is to send ] to this learned nation."<ref name="Farqhar-202"> | |||

| {{cite book | |||

| | author = J. N. Farquhar | |||

| | title = Modern Religious Movements in India | |||

| | page = 202 | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> Swami Vivekananda was regarded as, "undoubtedly the greatest figure in the parliament of religions", "beyond question, the most popular and influential man in the parliament."<ref name="McRae">{{cite journal|last=McRae|first=John R. |date=1991|title=Oriental Verities on the American Frontier: The 1893 World's Parliament of Religions and the Thought of Masao Abe|journal=Buddhist-Christian Studies|publisher=University of Hawai'i Press|volume=11|pages=7-36|url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/1390252|quote=The single most prominent representative of Asian religions at the World's Parliament of Religions was undoubtedly Vivekananda.}}</ref><ref name="Arvind_Sharma_87">{{cite book|last=Sharma|first=Arvind |title=Neo-Hindu Views of Christianity|page=87|chapter=Swami Vivekananda's Experiences}}</ref> | |||

| Vivekananda travelled to the United Kingdom in 1895 and again in 1896.{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|p=30}} In November 1895 he met an Irish woman, Margaret Elizabeth Noble, who would become one of his closest disciples, known as ] (a name given her by the Swami, meaning "dedicated to God").{{Sfn|Isherwood|Adjemian|1987|pp=121–122}} On his second visit, in May 1896, Vivekananda met ], a noted ] from ] who wrote Ramakrishna's first biography in the West.{{Sfn|Prabhananda|2003|p=234}} From the UK, he visited other European countries. In Germany, he met ], another renowned Indologist.{{Sfn|Chetananda|1997|pp=49–50}} | |||

| He ] several more times at the Parliament on topics related to Hinduism and ]. The parliament ended on 27 September 1893. All his speeches at the Parliament had one common theme—Universality and stressed religious tolerance.<ref name="bhuyan-18">{{cite book | author = P. R. Bhuyan | title = Swami Vivekananda | page = 18}}</ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ==== Lecturing tours in America, England ==== | |||

| | align = left | |||

| | total_width = 380 | |||

| | image1 = Vivekananda Image August 1894.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = | |||

| | caption1 = Vivekananda in ], Maine (August 1894).<ref>{{cite web|title=Swami Vivekananda Know Photos America 1893–1895 |url=http://www.vivekananda.net/photos/1893-1895TN/pages/green_acre-1894-august-4.htm |publisher=vivekananda.net|access-date=6 April 2012}}</ref> | |||

| | image2 = Swami Vivekananda at Mead sisters house, South Pasadena.jpg | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = Vivekananda at Mead sisters' house, ] in 1900. | |||

| }} | |||

| Vivekananda's success led to a change in mission, namely the establishment of Vedanta centres in the West.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=120}} He adapted traditional Hindu ideas and religiosity to suit the needs and understandings of his western audiences, who were more familiar with western esoteric traditions and movements.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=119-123}} An important element in his adaptation of Hindu religiosity was the introduction of his "four yogas" model, based in ], which offered a practical means to realise the divine force within, a central goal of modern western esotericism.{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=119-123}} In 1896, his book '']'', an interpretation and adaptation of ]'s ],{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=123-126}} was published, becoming an instant success; it became highly influential in the western understanding of ], in ]'s view marking the beginning of ].{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=125-126}}{{sfn|De Michelis|2005|p=149-180}} | |||

| After the Parliament of Religions, held in Sept. 1893 at ], Vivekananda spent nearly two whole years lecturing in various parts of eastern and central United States, appearing chiefly in Chicago, Detroit, Boston, and New York. By the spring of 1895, he was weary and in poor health, because of his continuous exertion.<ref name="wishtree-121-122">{{cite book|last=Adjemian|first= Robert |coauthors=Christopher Isherwood|title=The Wishing Tree|pages=121-122|chapter=On Swami Vivekananda}}</ref> After suspending his lecture tour, the Swami started giving free and private classes on '']'' and '']''. In June 1895, for two months he conducted private lectures to a dozen of his disciples at the ]. Vivekananda considered this to the happiest part of his first visit to America. He later founded the "] of ]".<ref name="wishtree-121-122" /> | |||

| Vivekananda attracted followers and admirers in the US and Europe, including ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{Sfn|Nikhilananda|1964}}{{Sfn|Isherwood|Adjemian|1987|pp=121–122}}{{Sfn|Chetananda|1997|pp=49–50}}{{Sfn|Chetananda|1997|p=47}}<ref>{{cite news |last1=Bardach |first1=A. L. |title=What Did J.D. Salinger, Leo Tolstoy, and Sarah Bernhardt Have in Common? |url=https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303404704577305581227233656 |access-date=31 March 2022 |newspaper=Wall Street Journal |date=30 March 2012}}</ref> He initiated several followers, including Marie Louise (a French woman) who became ], and Leon Landsberg who became Swami Kripananda,{{Sfn|Burke|1958|p=618}} so that they could serve the mission of the Vedanta Society.{{Sfn|Thomas|2003|pp=78–81}} He also initiated Christina Greenstidel of Detroit, who became ],{{sfn|Vrajaprana|1996|p=7}} with whom he developed a close father–daughter relationship.<ref name="Sarada society">{{cite journal |title=A Monumental Meeting | periodical= Sri Sarada Society Notes |last=Shack | first=Joan |url=http://www.srisarada.org/notes/512.pdf |location=Albany, New York |year= 2012 |volume=18 |issue=1}}</ref> | |||

| During his first visit to America, he traveled to England twice—in 1895 and 1896. His lectures were successful there.<ref>{{cite book|last=Banhatti|first=G.S. |title=Life and Philosophy of Swami Vivekananda|page=30|chapter=First visit to the West}}</ref> Here he met Miss Margaret Noble an ] lady, who later became ].<ref name="wishtree-121-122" /> During his second visit in May 1896, the Swami met ] a renowned ] at ] who wrote Ramakrishna's first biography in the West.<ref name="Prabha-2003" /> From England, he also visited other European countries. In Germany he met ], another famous Indologist.<ref name="GLWT-49-50">''God lived with them'', pp.49-50</ref> | |||

| While in America, Vivekananda was given land to establish a retreat for Vedanta students, in the mountains to the southeast of ]. He called it "Peace retreat", or ''Shanti Asrama''.{{Sfn|Wuthnow|2011|pp=85–86}} There were twelve main centres established in America, the largest being the Vedanta Society of Southern California in Hollywood. There is also a Vedanta Press in Hollywood which publishes books about Vedanta and English translations of Hindu scriptures and texts.{{Sfn|Rinehart|2004|p=392}} | |||

| He also received two academic offers, the chair of ] at ] and a similar position at ]. He declined both, saying that, as a wandering monk, he could not settle down to work of this kind.<ref name="wishtree-121-122" /> | |||

| From the West, Vivekananda revived his work in India. He regularly corresponded with his followers and brother monks, offering advice and financial support. His letters from this period reflect his campaign of social service,{{Sfn|Kattackal|1982|p=219}} and were strongly worded.{{Sfn|Majumdar|1963|p=577}} He wrote to ], "Go from door to door amongst the poor and lower classes of the town of Khetri and teach them religion. Also, let them have oral lessons on geography and such other subjects. No good will come of sitting idle and having princely dishes, and saying "Ramakrishna, O Lord!"—unless you can do some good to the poor".{{Sfn|Burke|1985|p=417}}{{Sfn|Sharma|1963|p=227}} In 1895, Vivekananda founded the periodical '']''.{{Sfn|Sheean|2005|p=345}} His translation of the first six chapters of '']'' was published in ''Brahmavadin'' in 1899.{{Sfn|Sharma|1988|p=83}} Vivekananda left for India from England on 16 December 1896, accompanied by his disciples Captain and Mrs. Sevier and J.J. Goodwin. On the way, they visited France and Italy, and set sail for India from Naples on 30 December 1896.{{Sfn|Banhatti|1995|pp=33–34}} He was followed to India by Sister Nivedita, who devoted the rest of her life to the education of Indian women and the goal of India's independence.{{Sfn|Isherwood|Adjemian|1987|pp=121–122}}{{Sfn|Dhar|1976|p=852}} | |||