| Revision as of 14:45, 8 June 2009 editAradic-es (talk | contribs)2,058 editsmNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:28, 5 January 2025 edit undo2600:1006:a132:576f:d815:741c:99a5:5a94 (talk)No edit summaryTags: Visual edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|King of Hungary and Croatia from 1458 to 1490}} | |||

| {{Infobox Royalty | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| | name = | |||

| {{Use Oxford spelling|date=September 2014}} | |||

| | name = Matthias Corvinus of Hungary | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=June 2020}} | |||

| | native name = Hunyadi Mátyás | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| | title = King of Hungary, King of Bohemia, Duke of Austria | |||

| | |

| name = Matthias Corvinus | ||

| | image = Andrea Mantegna - King Matthias Corvinus of Hungary.jpg | |||

| | imgw =200px | |||

| | caption = | | caption = Portrait by ] | ||

| | image_size = | |||

| | succession = ] | |||

| | |

| succession = ] and ] | ||

| | reign = 24 January 1458 – 6 April 1490 | |||

| | coronation = ] | |||

| | coronation = 29 March 1464 | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | regent = | |||

| | |

| regent = ] (1458) | ||

| | succession1 = ]<br />contested by ] and ] | |||

| | reign1 = ]-] | |||

| | |

| reign1 = 1469–1490 | ||

| | |

| coronation1 = | ||

| | predecessor1 = ] | |||

| | successor1 = | |||

| | |

| successor1 = ] | ||

| | succession2 = ]<br />contested by ] | |||

| | reign2 = ]-] | |||

| | |

| reign2 = 1487–1490 | ||

| | coronation2 = | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | spouse = ]</br>]</br>] | |||

| | spouse = {{ubl|{{marriage|]|1455|1455|end=dead}}|{{marriage|]|1463|1464|end=dead}}|{{marriage|]|1475}}}} | |||

| | issue = | |||

| | |

| issue = ] ''(illegitimate)'' | ||

| | |

| house = ] | ||

| | |

| father = ] | ||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | date of birth = ] | |||

| | birth_date = 23 February 1443 | |||

| | place of birth = ], ] (present-day ], ]) | |||

| | birth_place = Kolozsvár, ] (now ], Romania) | |||

| | date of death = ] | |||

| | death_date = {{Death date and age|df=yes|1490|04|06|1443|02|23}} | |||

| | place of death = ] | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| | place of burial= | |||

| | burial_place = ], Székesfehérvár | |||

| |feast_day= | |||

| | religion = ] | |||

| |venerated= | |||

| | signature = Mátyás király aláirása.svg | |||

| |saint_title = | |||

| |beatified_date= | |||

| |beatified_place= | |||

| |beatified_by= | |||

| |canonized_date= | |||

| |canonized_place= | |||

| |canonized_by= | |||

| |attributes= | |||

| |patronage= | |||

| |shrine= | |||

| |suppressed_date= | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Matthias Corvinus''' ({{langx|hu|Hunyadi Mátyás}}; {{langx|ro|Matia/Matei Corvin}}; {{langx|hr|Matija/Matijaš Korvin}}; {{langx|sk|Matej Korvín}}; {{langx|cs|Matyáš Korvín}}; {{daterangedash|23 February 1443|6 April 1490|dmy}}) was ] and ] from 1458 to 1490, as '''Matthias I'''. After conducting several military campaigns, he was elected ] in 1469 and adopted the title ] in 1487. He was the son of ], ], who died in 1456. In 1457, Matthias was imprisoned along with his older brother, ], on the orders of King ]. Ladislaus Hunyadi was executed, causing a rebellion that forced King Ladislaus to flee Hungary. After the King died unexpectedly, Matthias's uncle ] persuaded the ] to unanimously proclaim the 14-year-old Matthias as king on 24 January 1458. He began his rule under his uncle's guardianship, but he took effective control of government within two weeks. | |||

| As king, Matthias waged wars against the Czech ] who dominated ] (today parts of ] and ]) and against ], who claimed Hungary for himself. In this period, the ] conquered ] and ], terminating the zone of ]s along the southern frontiers of the ]. Matthias signed a peace treaty with Frederick III in 1463, acknowledging the Emperor's right to style himself King of Hungary. The Emperor returned the ] with which Matthias was crowned on 29 April 1464. In this year, Matthias invaded the territories that had recently been occupied by the Ottomans and seized fortresses in Bosnia. He soon realized he could expect no substantial aid from the Christian powers and gave up his anti-Ottoman policy. | |||

| '''Matthias I''' (also known as '''Matthias Corvinus'''<ref>In English, his first name is occasionally given as ''Matthew'', while ''Corvinus'' may be rendered as ''Corwin'' or ''Corvin''; ]: ''Hunyadi Mátyás'' or ''Corvin Mátyás''; {{lang-ro|Matei}} (or, seldom, ''Mateiaş'') ''Corvin''; {{lang-sk|Matej Korvín or Kráľ Matej}}; {{lang-cs|Matyáš Korvín}}; ], ]: ''Matija Korvin'' (in Croatian also ''dobri kralj Matijaš''—"the good king Matthew"—and in Slovene '']''); {{lang-pl|Maciej Korwin}}; {{lang-sr|Matija Korvin}} (''Матија Корвин'').</ref> or ''Matthias the Just''; February 23, 1443 – April 6, 1490) was ] of ] , Croatia and ]. <ref name=britannica>Matthias I. (2009). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved April 13, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/369772/Matthias-</ref> | |||

| Matthias introduced new taxes and regularly set taxation at extraordinary levels. These measures caused a rebellion in ] in 1467, but he subdued the rebels. The next year, Matthias declared war on ], the ] King of Bohemia, and conquered ], ], and ], but he could not occupy ] proper. The Catholic Estates proclaimed him King of Bohemia on 3 May 1469, but the Hussite lords refused to yield to him even after the death of their leader George of Poděbrady in 1471. Instead, they elected ], the eldest son of ]. A group of Hungarian prelates and lords offered the throne to Vladislaus's younger brother ], but Matthias overcame their rebellion. Having routed the united troops of Casimir IV and Vladislaus at ] in ] (now Wrocław in Poland) in late 1474, Matthias turned against the Ottomans, who had devastated the eastern parts of Hungary. He sent reinforcements to ], ], enabling Stephen to repel a series of Ottoman invasions in the late 1470s. In 1476, Matthias besieged and seized ], an important Ottoman border fort. He concluded a peace treaty with Vladislaus Jagiellon in 1478, confirming the division of the ] between them. Matthias waged a war against Emperor Frederick and occupied ] between 1482 and 1487. | |||

| Matthias established one of the earliest professional standing armies of medieval Europe (the ]), reformed the administration of justice, reduced the power of the barons, and promoted the careers of talented individuals chosen for their abilities rather than their social statuses. Matthias patronized art and science; his royal library, the '']'', was one of the largest collections of books in Europe. With his patronage, Hungary became the first country to embrace the ] from Italy. As Matthias the Just, the monarch who wandered among his subjects in disguise, he remains a popular hero of Hungarian and Slovak<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://zlatyfond.sme.sk/dielo/5034/Klima_Povesti-zo-Slovenska/16|title = Stanislav Klíma: Povesti zo Slovenska (Kráľ Matej a bača) – elektronická knižnica}}</ref> folk tales. | |||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| ] in Kolozsvár (present-day ], Romania)]] | |||

| Matthias (Hungary: Hunyadi Mátyás) was born at ], ] (present-day ], ]) in the house currently known as ], the second son of ], a successful military leader of ]<ref name="morizsnay">Hóman Bálint- Szekfű Gyula: Magyar történet II., KMENy, Bp., 1936, 432.</ref> and ]<ref>http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/10066b.htm</ref> descent who had risen through the ranks of the ] to become ] of Hungary, and ], from a ] noble family. | |||

| ] | ], Milan, Italy.]] | ||

| His tutors were the learned ], bishop of ], whom he subsequently raised to the primacy, and the Polish humanist ]. The precocious Matthias quickly mastered German, Italian, Romanian, Latin and principal Slavic languages, frequently acting as his father's interpreter at the reception of ambassadors. His military training proceeded under the eye of his father, whom he began to follow on his campaigns when only twelve years of age. In 1453 he was created count of ], and was knighted at the ] in 1456. | |||

| ===Childhood (1443–1457)=== | |||

| The same care for his welfare led his father to choose him a bride in the powerful family of the ]. Mattias was married to Elizabeth of Celje. She was the only known daughter of ] and Catherine Cantakuzina. Her maternal grandparents were ] and ]. But the young Elizabeth died in 1455, before the marriage was consummated. Leaving Matthias a widower at the age of fifteen. <ref> </ref>: | |||

| Matthias was born in Kolozsvár (now ] in Romania) on 23 February 1443.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=23}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=26}} He was the second son of ] and his wife, ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=23}}{{sfn|Mureşanu|2001|p=49}} Matthias' education was managed by his mother due to his father's absence.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=23}} Many of the most learned men of ], including ] and ], frequented John Hunyadi's court when Matthias was a child.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|pp=27–28}} Gregory of Sanok, a former tutor of King ], was Matthias's only teacher whose name is known.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=24}} Under these scholars' influences, Matthias became an enthusiastic supporter of ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=161}}{{sfn|Klaniczay|1992|p=165}} | |||

| After the death of Matthias's father, there was a two-year struggle between Hungary's various barons and its ] king, ] (also king of Bohemia), with treachery from all sides. Matthias's older brother ] was one party attempting to gain control. Matthias was inveigled to Buda by the enemies of his house, and, on the pretext of being concerned in a purely imaginary conspiracy against Ladislaus, was condemned to decapitation, but was spared on account of his youth. In 1457, László Hunyadi was captured with a trick and beheaded, while the king died suddenly in November that year (rumors of poisoning were dispelled by research in 1985 which gave acute leukemia as the cause of death). Matthias was taken hostage by ], governor of ], a friend of the Hunyadis who aimed to raise a national king to the ]. Poděbrady treated Matthias hospitably and affianced him with his daughter Catherine, but still detained him, for safety's sake, in Prague, even after a Magyar deputation had hastened thither to offer the youth the crown. Matthias took advantage of the memory left by his father's deed, and by the general population's dislike of foreign candidates; most the barons, furthermore, considered that the young scholar would be a weak monarch in their hands. An influential section of the magnates, headed by the palatine László Garai and by the voivode of Transylvania, ], who had been concerned in the judicial murder of Matthias's brother László, and hated the Hunyadis as semi-foreign upstarts, were fiercely opposed to Matthias's election; however, they were not strong enough to resist against Matthias's uncle ] and his 15,000 veterans. | |||

| ]'' by ].]] | |||

| As a child, Matthias learnt many languages and read ], especially military treatises.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=24}} According to ], Matthias "was versed in all the tongues of Europe", with the exceptions of ] and ].{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=28}} Although this was an exaggeration, it is without doubt that Matthias spoke ], ], ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=24}}{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=28, 86}} Bonfini also wrote that he needed an interpreter to speak with a ] during his ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Geréb |first1=László |url=https://mek.oszk.hu/10600/10604/10604.htm |title=Mátyás király |publisher=Magyar Helikon |year=1959 |language=hu |chapter=III |quote=Tolmács útján megkérdezte: kicsoda, honnan jön, hová megy s mi okból van úton. Felelte erre: tolmácsra nincs szükség, mert ő magyar s Erdélyből való; azért jött Moldvába - az eseményekről mitsem tudva -, hogy fölkeresse földjeit, melyek felesége öröklött javai.}}</ref> On the other hand, the late 16th-century Polish historian Krzystoff Warszewiecki wrote that Matthias had been able to understand the ] of the envoys of ], ].{{sfn|Pop|2012|p=5}} | |||

| ==Rule== | |||

| ===Early rule=== | |||

| According to a treaty between John Hunyadi and ], ], Matthias and the Despot's granddaughter ] were engaged on 7 August 1451.{{sfn|Mureşanu|2001|p=174}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=292}} Elizabeth was the daughter of ], who was related to King ] and an opponent of Matthias's father.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=25}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=290–292}} Because of new conflicts between Hunyadi and Ulrich of Celje, the marriage of their children only took place in 1455.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=25–26}} Elizabeth settled in the ]' estates but Matthias was soon sent to the royal court, implying that their marriage was a hidden exchange of hostages between their families.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=25}} Elizabeth died before the end of 1455.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=25}} | |||

| Thus, on January 20, 1458, Matthias was elected king by the ]. This was the first time in the medieval Hungarian kingdom that a member of the nobility, without dynastic ancestry and relationship, mounted the royal throne. Such an elections upset the usual course of dynastic succession in the age. In the Czech and Hungarian states they heralded a new judiciary era in Europe, characterized by the absolute supremacy of the Parliament , ( dietal system ) and a tendency to centralization. | |||

| At this time Matthias was still a hostage of George of Poděbrady, who released him under the condition of marrying his daughter ]. On 24 January 1458, 40,000 Hungarian noblemen, assembled on the ice of the frozen Danube, unanimously elected Matthias Hunyadi king of Hungary, and on 14 February the new king made his state entry into Buda. | |||

| ] from Matthias]] | |||

| John Hunyadi died on 11 August 1456, less than three weeks after ] over the ] in ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=280, 296}} John's elder son, who was Matthias's brother, ] became the head of the family.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=25}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=296}} Ladislaus's conflict with Ulrich of Celje ended with Ulrich's capture and assassination on 9 November.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=569}}{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=61}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=26}} Under duress, the King promised he would never take his revenge against the Hunyadis for Ulrich's killing.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=297}} However, the murder turned most barons{, including ] ], ] Ladislaus Pálóci, and ], ], against Ladislaus Hunyadi.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=297}} Taking advantage of their resentment, the King had the Hunyadi brothers imprisoned in Buda on 14 March 1457.{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=61}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=27}} The royal council condemned them to death for high treason and Ladislaus Hunyadi was beheaded on 16 March.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=49}} | |||

| Matthias was 15 when he was elected King of Hungary: at this time the realm was environed by perils. The ] and the ] threatened it from the south, the emperor ] from the west, and ] from the north, both Frederick and Casimir claiming the throne. The Czech mercenaries under ] held the northern counties and from thence plundered those in the centre. Meanwhile Matthias's friends had only pacified the hostile dignitaries by engaging to marry the daughter of the palatine Garai to their nominee, whereas Matthias refused to marry into the family of one of his brother's murderers, and on 9 February confirmed his previous nuptial contract with the daughter of Poděbrady, who shortly afterwards was elected ] (March 2, 1458). Throughout 1458 the struggle between the young king and the magnates, reinforced by Matthias's own uncle and guardian Szilágyi, was acute. But Matthias, who began by deposing Garai and dismissing Szilágyi, and then proceeded to levy a tax, without the consent of the Diet, in order to hire mercenaries, easily prevailed. He recovered the ] from the Ottomans, successfully invading ], and reasserting the suzerainty of the Hungarian crown over ]. In the following year there was a fresh rebellion, when the emperor Frederick was actually crowned king by the malcontents at Vienna-Neustadt (March 4, 1459); Matthias however drove him out, and ] intervened so as to leave Matthias free to engage in a projected crusade against the Ottomans, which subsequent political complications, however, rendered impossible. On 1 May 1461, the marriage between Matthias and Poděbrady's daughter took place. | |||

| Matthias was held in captivity in a small house in Buda.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=297}}{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=50}} His mother and her brother ] staged a rebellion against the King and occupied large territories in the regions to the east of the river ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=297}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=27}} King Ladislaus fled to ] in mid-1457, and from Vienna to ] in September, taking Matthias with him.{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=61}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=28}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=30}} The civil war between the rebels and the barons loyal to the monarch continued until the sudden death of the young King on 23 November 1457.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=297}} Thereafter the ] Regent of Bohemia, ], held Matthias captive.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=30}} | |||

| From 1461 to 1465 the career of Matthias was a perpetual struggle punctuated by truces. Having come to an understanding with his father-in-law Poděbrady, he was able to turn his arms against the emperor Frederick. In April 1462 the latter restored the holy crown for 60,000 ducats and was allowed to retain certain Hungarian counties with the title of king; in return for which concessions, extorted from Matthias by the necessity of coping with a simultaneous rebellion of the Magyar noble in league with Poděbrady's son Victorinus, the emperor recognized Matthias as the actual sovereign of Hungary. Only now was Matthias able to turn against the Ottomans, who were again threatening the southern provinces. He began by defeating the Ottoman general Ali Pasha, and then penetrated into Bosnia, capturing the newly built fortress of ] after a long and obstinate defence (December 1463). On returning home he was crowned with the ] on 29 March 1464. Twenty-one days after, on 8 March, the 15-years-old Queen Catherine died in childbirth. The child, a son, was stillborn. | |||

| ]'' – a painting by ]]] | |||

| ===Election as king (1457–1458)=== | |||

| After driving the Czechs out of his northern counties, he turned southwards again, this time recovering all the parts of Bosnia which still remained in Ottoman hands. | |||

| King Ladislaus died childless in 1457.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=29}}{{sfn|Magaš|2007|p=75}} His elder sister, ], and her husband, ], laid claim to his inheritance but received no support from the ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=29}} The ] was convoked to Pest to elect a new king in January 1458.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}} ]'s ] ] ], who had been John Hunyadi's admirer, began openly campaigning for Matthias.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=31}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The election of Matthias as king was the only way of avoiding a protracted civil war.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}} Ladislaus Garai was the first baron to yield.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=31}} At a meeting with Matthias's mother and uncle, he promised that he and his allies would promote Matthias's election, and Michael Szilágyi promised that his nephew would never seek vengeance for Ladislaus Hunyadi's execution.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=31}} They also agreed that Matthias would marry the Palatine's daughter Anna, his executed brother's bride.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=31}} | |||

| ===Wars in central Europe=== | |||

| Michael Szilágyi arrived at the Diet with 15,000 troops, intimidating the barons who assembled in Buda.{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=61}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}} Stirred up by Szilágyi, the noblemen gathered on the frozen River Danube and unanimously proclaimed the 14-year-old Matthias king on 24 January.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=298}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=31–32}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}} At the same time, the Diet elected his uncle as regent.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=31}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}} | |||

| Matthias gained independence of and power over the barons by dividing them, and by raising a large royal army, ''fekete sereg'' (the King's ] of ]), whose main force included the remnants of the ]s from Bohemia. At this time Hungary reached its greatest territorial extent of the epoch (present-day southeastern ] to the west, ] to the south, ] to the east, and southwestern ] to the north). | |||

| ==Reign== | |||

| Soon after his coronation, Matthias turned his attention upon Bohemia, where the ] leader ] had gained the throne. In 1465 ] excommunicated the Hussite King and ordered all the neighbouring princes to depose him. On 31 May 1468, Matthias invaded Bohemia; however, as early as 27 February 1469, he anticipated an alliance between George and Frederick by himself concluding an armistice with the former. On 3 May the Bohemian Catholics elected Matthias king of Bohemia, but this was contrary to the wishes of both pope and emperor, who preferred to partition Bohemia. George however anticipated all his enemies by suddenly excluding his own son from the throne in favour of Ladislaus, the eldest son of Casimir IV, thus skillfully enlisting Poland on his side. The sudden death of Poděbrady in March 1471 led to fresh complications. At the very moment when Matthias was about to profit by the disappearance of his most capable rival, another dangerous rebellion, headed by the primate and the chief dignitaries of the state, with the object of placing Casimir, son of Casimir IV, on the throne, paralysed Matthias's foreign policy during the critical years 1470-1471. He suppressed this domestic rebellion indeed, but in the meantime the Poles had invaded the Bohemian domains with 60,000 men, and when in 1474 Matthias was at last able to take the field against them in order to raise the siege of ], he was obliged to fortify himself in an entrenched camp, whence he so skillfully harried the enemy that the Poles, impatient to return to their own country, made peace at Breslau (February 1475) on an '']'' basis, a peace subsequently confirmed by the congress of Olomouc (July 1479). | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Early rule and consolidation (1458–1464)=== | |||

| During the interval between these pieces, Matthias, in self-defence, again made war on the emperor, reducing Frederick to such extremities that he was glad to accept peace on any terms. By the final arrangement made between the contending princes, Matthias recognized Ladislaus as king of Bohemia proper in return for the surrender of ], ] and ] and ], hitherto component parts of the Bohemian monarchy, till he should have redeemed them for 400,000 florins. The emperor promised to pay Matthias a huge war indemnity, and recognized him as the legitimate king of Hungary on the understanding that he should succeed him if he died without male issue, a contingency at this time somewhat improbable, as Matthias, only three years previously (15 December 1476), had married his third wife, ], daughter of ]. | |||

| {{See also|Peace Treaty of Wiener Neustadt}} | |||

| {{Campaignbox Battles of Matthias Corvinus}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Matthias's election was the first time that a member of the nobility mounted the royal throne in Hungary.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=50}} Michael Szilágyi sent John Vitéz to Prague to discuss the terms of Matthias's release with George of Poděbrady.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=54}} Poděbrady, whose daughter ] Matthias promised to marry, agreed to release his future son-in-law for a ransom of 60,000 gold ]s.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=53–54}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=299}} Matthias was surrendered to the Hungarian delegates in ] on 9 February.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=54}} With Poděbrady's mediation, he was reconciled with ], the commander of the Czech mercenaries who dominated most of ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=57}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=300}} | |||

| The emperor's failure to follow through on these promises induced Matthias to declare war against him for the third time in 1481. The Hungarian king conquering all the fortresses in Frederick's hereditary domains. Finally, on 1 June 1485, at the head of 8,000 veterans, he made his triumphal entry into Vienna, which he henceforth made his capital. ], ] and ] were next subdued; ] was only saved by the intervention of the Venetians. Matthias consolidated his position by alliances with the ] and ], with the ] and the ], establishing henceforth the greatest potentate in central Europe. | |||

| Matthias made his state entry into Buda five days later.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=55}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=32}} He ceremoniously sat on the throne in the Church of Our Lady, but was not crowned, because the ] had been in the possession of ] for almost two decades.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=55}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=282, 299}} The 14-year-old monarch administered state affairs independently from the outset, although he reaffirmed his uncle's position as Regent.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=33}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=56}} For instance, Matthias instructed the citizens of Nagyszeben (now ] in Romania) to reconcile their differences with ], ] on 3 March.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=56}} | |||

| ===Wars against the Ottoman Empire=== | |||

| In 1471 Matthias renewed the ] in south Hungary under ] for the protection of the borders against the Ottomans. In 1479 a huge Ottoman army, on its return home from ravaging Transylvania, was annihilated at Szászváros (modern ], 13 October 1479) in the so-called ]. The following year Matthias recaptured Jajce, drove the Ottomans from northern Serbia and instituted two new military banats, Jajce and Srebernik, out from reconquered Bosnian territory. | |||

| Jiskra was the first baron who turned against Matthias.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=57}} He offered the throne to ], the husband of King Ladislaus V's younger sister ], in late March but the ] of Poland rejected his offer.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=57}} Matthias's commander Sebastian Rozgonyi defeated Jiskra's soldiers at ] but the Ottomans' invasion of ] in April forced Matthias to conclude an armistice with the Czechs.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=57–58}}{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=573}} They were allowed to keep Sáros Castle (now ], Slovakia) and other fortified places in Upper Hungary.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=58}} Matthias sent two prelates, August Salánki, ], and Vincent Szilasi, ], to Prague to crown George of Poděbrady king.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=57}} Upon their demand, the "heretic" Poděbrady swore loyalty to the ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=57}} | |||

| In 1480, when a Ottoman fleet ] in the Kingdom of Naples, at the earnest solicitation of the pope he sent the Hungarian general, Balázs Magyar, to recover the fortress, which surrendered to him on 10 May 1481. Again in 1488, Matthias took ] under his protection for a while, occupying it with a Hungarian garrison. | |||

| ], and ]]] | |||

| On the death of sultan ] in 1481, a unique opportunity for the intervention of Europe in Ottoman affairs presented itself. A civil war ensued in Ottoman Empire between his sons ] and ]; the latter, being worsted, fled to the ], by whom he was kept in custody in France. Matthias, as the next-door neighbour of the Ottomans, claimed the custody of so valuable a hostage, and would have used him as a means of extorting concessions from Bayezid. But neither the pope nor the Venetians would accept such a transfer, and the negotiations on this subject greatly embittered Matthias against the Papal court. The last days of Matthias were occupied in endeavouring to secure the succession to the throne for his illegitimate son ]; Queen Beatrice, though childless, fiercely and openly opposed the idea and the matter was still pending when Matthias, who had long been crippled by gout, expired very suddenly on 6 April 1490, just before Easter. | |||

| Matthias's first Diet assembled in Pest in May 1458.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=315}} The Estates passed almost fifty decrees that were ratified by Matthias, instead of the Regent, on 8 June.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=60}} One decree prescribed that the King "must call and hold, and order to be held, a diet of all the gentlemen of the realm in person"{{sfn|Bak|Domonkos|Harvey|Garay|1996|p=7}} every year on ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=315}} Matthias held more than 25 Diets during his reign and convoked the Estates more frequently than his predecessors, especially between 1458 and 1476.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=315}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=125–126}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=51}} The Diets were controlled by the barons, whom Matthias appointed and dismissed at will.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=315}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=49}} For instance, he dismissed Palatine Ladislaus Garai and persuaded Michael Szilágyi to resign from the Regency after they entered into a league in the summer of 1458.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=61}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=299}} The King appointed ], who had been his father's close supporter, as the new Palatine.{{sfn|Markó|2006|p=244}} Most of Matthias's barons were descended from old aristocratic families but he also promoted the careers of members of the lesser nobility, or even of skilful commoners.{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=311–313}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=122, 181}} For instance, the noble ] brothers ] and ] owed their fortunes to Matthias's favour.{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=311–312}} | |||

| ===Policies in Wallachia and Moldavia=== | |||

| At times Matthias had ], the ] of ], as his vassal. Although Vlad had great success against the Ottoman armies, the two ] rulers disagreed in 1462, leading to Matthias imprisoning Vlad in Buda (according to some sources, Vlad betrayed Matthias){{fact|date=November 2008}}. However, wide-ranging support from many Western leaders for Vlad III prompted Matthias to gradually grant privileged status to his controversial prisoner. Vlad was eventually freed and married Matthias' cousin, ]. As the Ottoman Empire appeared to be increasingly threatening as Vlad Tepes had warned, he was sent to reconquer Wallachia with Hungarian support in 1476. Despite the earlier disagreements between the two leaders, it was ultimately a major blow to Hungary's status in Wallachia when Vlad was assassinated that same year. | |||

| Matthias's ordinary revenues amounted around 250,000 golden florins per year when his reign began.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=63}} A decree passed at the Diet of 1458 explicitly prohibited the imposition of extraordinary taxes.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=67}} However, an extraordinary tax, ] per each ''porta'' or peasant household, was levied late that year.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=67}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=310–311}} The Ottomans occupied the fort of ] in Serbia in August 1458; Matthias ordered the mobilization of all noblemen.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=574}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}} He made a raid into Ottoman territory and defeated the enemy forces in minor skirmishes.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}} King ] accepted Matthias's suzerainty.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=574}} Matthias authorized his new ]'s son ] to take possession of the parts of Serbia that had not been occupied by the Ottomans.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=574}} | |||

| In 1467, a conflict erupted between Matthias and the ]n ] ], after the latter became weary of Hungarian policies in Wallachia and their presence at ]; added to this was the fact that Matthias had already taken sides in the Moldavian conflicts preceding Stephen's rule, as he had backed ] (and, possibly, the ruler referred to as '']''), deposing ]. Stephen occupied Kilia, sparking Hungarian retaliation, that ended in Matthias' bitter defeat in the ] in December (the King himself is said to have been wounded thrice). | |||

| At the turn of 1458 and 1459, Matthias held a Diet at ] to prepare for a war against the Ottoman Empire.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=65}} However, gossip about a conspiracy compelled him to return to Buda.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=63, 65}} The rumours proved to be true because at least 30 barons{, including Ladislaus Garai, Nicholas Újlaki, and ], }met in Németújvár (now ] in Austria) and offered the throne to Emperor Frederick III on 17 February 1459.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=299}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=63}} Even George of Poděbrady turned against Matthias when Frederick promised him to make him governor of the Holy Roman Empire.<ref>Kisfaludy 35..p</ref> Although the joint troops of the Emperor and the rebellious lords defeated a royal army at ] on 27 March, Garai had by that time died, Újlaki and Sigismund Szentgyörgyvölgyi soon entered into negotiations with Matthias' envoys.Újlaki became indifferent, Szentgyörgyvölgyi joined to Matthias.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=63}} Skirmishes along the western borderlands lasted for several months, preventing Matthias from providing military assistance to Tomašević against the Ottomans.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=65}} The latter took ] on 29 June, completing the conquest of Serbia.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=575}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=301}} | |||

| ==Legacy== | |||

| ] banknote, 2008]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In the course of his expansion, Matthias strengthened his state's diplomacy. Apart from his regular network of relations with his neighbours, as well as the ] and ], he established regular contacts with ], ], ], ], most ] states, ] and, occasionally, with ] and ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Matthias's empire collapsed after his death, since he had no children except for an illegitimate son, ], whom the noblemen of the country did not accept as their king. The weak king of Bohemia, ] of the ] ] line, followed him – Ladislaus nominally ruled the areas Matthias conquered except Austria – but real power was in the hand of the nobles. In 1514, two years before Ladislaus's death, the nobility crushed the peasant rebellion of ] with ruthless methods. As central rule degenerated, the stage was set for a defeat at the hands of the ]. In 1521, ] fell, and, in 1526, the Hungarian army was destroyed by the Turks in the ]. | |||

| Jiskra swore an oath of loyalty to Emperor Frederick on 10 March 1460.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=65}} ] offered to mediate a peace treaty between the Emperor and Matthias.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=299}} Podedébrandy also realised he need to support Matthias or at least had to be indifferent. He sent his daughter to Buda also offered his assistance.{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=62}}<ref>Kisfaludy 38.p</ref> The representatives of the Emperor and Matthias signed a truce in Olomouc in April 1460.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}} The Pope soon offered financial support for an anti-Ottoman campaign.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=65}} However, John Jiskra returned from Poland, renewing the armed conflicts with Czech mercenaries in early 1460.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=65}} Matthias seized a newly-erected fort from the Czechs but he could not force them to obey him.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=65}} The costs of his five-month-long campaign in Upper Hungary were paid for by an extraordinary tax.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=69}} | |||

| Matthias entered into an alliance with the Emperor's rebellious brother ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=37}} George of Poděbrady sided with the Emperor although the marriage of his daughter, who became known as Catherine in Hungary, to Matthias was celebrated on 1 May 1461(married 1461 to 1464).{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=67}}{{sfn|Šmahel|2011|p=167}} Relations between Matthias and his father-in-law deteriorated because of the Czech mercenaries' continued presence in Upper Hungary.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=303}} Matthias launched a new campaign against them after the Diet authorized him to collect an extraordinary tax in mid-1461.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=58, 68–69}} However, he did not defeat Jiskra, who even captured Késmárk (now ], ]).{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=58}} | |||

| High ]es, mostly falling on peasants, to sustain Matthias' lavish lifestyle and the ''Black Army'' (cumulated with the fact that the latter went on marauding across the Kingdom after being disbanded upon Matthias's death) could imply that he was not very popular with his contemporaries. But the fact that he was elected king in a small anti-] popular revolution, that he kept the barons in check, persistent rumours about him sounding public opinion by mingling among commoners ''incognito'', and harsh period known witnessed by Hungary later ensured that Matthias' reign is considered one of the most glorious chapters of Hungarian history. Songs and tales converted him into ''Matthias the Just'' (''Mátyás, az igazságos'' in Hungarian), a ruler of justice and great wisdom, as arguably the most popular hero of Hungarian folklore. He is also one of the ]. | |||

| The envoys of Matthias and Emperor Frederick agreed the terms of peace treaty on 3 April 1462.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}} According to the agreement, the Emperor was to return the Holy Crown of Hungary for 80,000 golden florins, but his right to use the title King of Hungary along with Matthias was confirmed.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=51}}{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=62}} In accordance with the treaty, the Emperor adopted Matthias, which granted him the right to succeed his "son" if Matthias died without a legitimate heir.{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=62}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} Within a month, Jiskra yielded to Matthias.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} He surrendered all the forts he held in Upper Hungary to the King's representatives; as compensation, he received a large domain near the Tisza and Arad and 25,000 golden florins. That happened before the peace treaty with Frederick. {{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=58}} To pay the large amounts stipulated in his treaties with the Emperor and Jiskra, Matthias collected an extraordinary tax with the consent of the Royal Council.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=59}} The Diet, which assembled in mid-1462, confirmed this decision but only after 9 prelates and 19 barons promised that no extraordinary taxes would be introduced thereafter.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=59}} Through hiring mercenaries among Jiskra's companions, Matthias began organizing a professional army, which became known as the "]" in following decades.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=309}} The peace treaty made in Wiener-Neustadt 19 July 1463.<ref>Kisfaludy 207.p.</ref> | |||

| ] ] invaded ] in early 1462.{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=264}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=301}} He did not conquer the country but the ] dethroned the anti-Ottoman Vlad Dracula and replaced him with the Sultan's favorite, ].{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=264}}{{sfn|Florescu|McNally|1989|pp=150–152}} The new Prince was willing to grant concessions to the ] merchants, who had come into bitter conflict with Vlad Dracula.{{sfn|Florescu|McNally|1989|p=157}} The latter sought assistance from Matthias and they met in Brassó (now ], Romania) in November.{{sfn|Florescu|McNally|1989|p=156}} However, the Saxons presented Matthias with a letter that was allegedly written by Vlad Dracula to Sultan Mehmed in which the Prince offered his support to the Ottomans.{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=264}} {{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=208}} Convinced of Vlad Dracula's treachery, Matthias had him imprisoned.{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=264}} | |||

| In preparation for a war against the Ottomans, Matthias held a Diet at ] in March 1463.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=68}} Although the Estates authorized him to levy an extraordinary tax of one florin, he did not intervene when Mehmed II invaded Bosnia in June.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=68–69, 71}} In a month, the Ottomans murdered King Stephen Tomašević and conquered the whole country.{{sfn|Magaš|2007|p=75}}{{sfn|Fine|1994|pp=584–585}} Matthias adopted an offensive foreign policy only after the terms of his peace with Emperor Frederick had been ratified in ] on 19 July 1463.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=39}} He led his troops to Bosnia and ] and other forts in its northern parts.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=586}} The conquered regions were organized into new defensive provinces, the banates of ] and ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=586}}{{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=229}} Matthias was assisted by ], ], who controlled the area of ] and ]. A former vassal to the Bosnian kings, Stjepan accepted Matthias's suzerainty.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=586}}{{sfn|Grgin|2003|p=88}} | |||

| Queen Catherine died in early 1464 during preparations for her husband's coronation with the Holy Crown, which had been returned by Emperor Frederick.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=161}} The ceremony was carried out in full accordance with the ] of Hungary on 29 March 1464; ] ] ceremoniously put the Holy Crown on Matthias's head in ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=161}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=73}} At the Diet assembled on this occasion, the newly crowned King confirmed the liberties of the nobility.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=302}} Hereafter the legality of Matthias's reign could not be questioned.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=73}} | |||

| ===First reforms and internal conflicts (1464–1467)=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] and Matthias's coat-of-arms]] | |||

| ====Political reforms==== | |||

| Matthias dismissed his Chief Chancellor Archbishop Szécsi, replacing him with ], ], and John Vitéz.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}} Both prelates bore the title of Chief and Secret Chancellor, but Várdai was the actual leader of the ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=74}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2004|p=29}} Around the same time, Matthias united the superior courts of justice, the ] and the ], into one supreme court.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=75–76}} The new supreme court diminished the authority of the traditional courts presided over by the barons and contributed to the professionalization of the administration of justice.{{sfn|Bak|1994|p=73}} He appointed ], ] as the first ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2004|p=32}}{{sfn|Bónis|1971|p=vi}} | |||

| Sultan Mehmed II returned to Bosnia and laid ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=586}}{{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=231}} Matthias began assembling his troops along the River ], forcing the Sultan to raise the siege on 24 August.{{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=231}} Matthias and his army crossed the river and seized ].{{sfn|Babinger|1978|pp=231–232}} He also besieged ], but the arrival of a large Ottoman army forced him to withdraw to Hungary.{{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=232}} The following year, Matthias forced Stefan Vukčić, who had transferred Makarska Krajina to the ], to establish Hungarian garrisons in his forts along the river ].{{sfn|Fine|1994|pp=586–587}} | |||

| Dénes Szécsi died in 1465 and John Vitéz became the new Archbishop of Esztergom.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=80}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=449}} Matthias replaced the two Voivodes of Transylvania (Nicholas Újlaki and John Pongrác of Dengeleg) with Counts ] and John Szentgyörgyi, and ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=81}} Although Újlaki preserved his office of ], the King appointed Peter Szokoli to administer the province together with the old Ban.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=82}} | |||

| Matthias convoked the Diet to make preparations for an anti-Ottoman campaign in 1466.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=82}} For the same purpose, he received subsidies from ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=81–82}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=135}} However, Matthias had realized that no substantial aid could be expected from the Christian powers and tacitly gave up his anti-Ottoman foreign policy.{{sfn|Magaš|2007|p=76}} He did not invade Ottoman territory and the Ottomans did not make major incursions into Hungary, implying that he signed a peace treaty with Mehmed II's envoy who arrived in Hungary in 1465.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=307}} | |||

| Matthias visited ] and dismissed the two ] Nicholas Újlaki and Emeric Zápolya, replacing them with Jan Vitovec and John Tuz in 1466.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=81}} Early the following year, he mounted a campaign in Upper Hungary against a band of Czech mercenaries who were under the command of Ján Švehla and had seized Kosztolány (now ] in Slovakia).{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=59}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=53}} Matthias routed them and had Švehla and his 150 comrades hanged.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=59}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} | |||

| ====Economic reforms==== | |||

| {{main|Economic Reforms of Matthias Corvinus}} | |||

| At the Diet of March 1467, two traditional taxes were renamed; the ] was thereafter collected as ] and the ] as the ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=310}} Because of this change, all previous tax exemptions became void, increasing state revenues.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=77–78}} Matthias set about centralizing the administration of royal revenues. He entrusted the administration of the Crown's customs to ], a converted Jewish merchant.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=76}} Within two years, Ernuszt was responsible for the collection of all ordinary and extraordinary taxes, and the management of the salt mines.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=61}} | |||

| Matthias's tax reform caused a revolt in Transylvania.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=78, 82}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}} The representatives of the "]" of the province (the noblemen, the Saxons and the ]) formed an alliance against the King in Kolozsmonostor (now ] district in Cluj-Napoca, Romania) on 18 August, stating that they were willing to fight for the freedom of Hungary.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=82}} Matthias assembled his troops immediately and hastened to the province.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=82–83}} The rebels surrendered without resistance but Matthias severely punished their leaders, many of whom were impaled, beheaded, or mercilessly tortured upon his orders.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=83}} Suspecting that Stephen the Great had supported the rebellion, Matthias invaded ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}}{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=266}} However, Stephen's forces routed Matthias's at the ] on 15 December 1467.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=302}}{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=266}} Matthias suffered severe injuries, forcing him to return to Hungary.{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=266}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=84}} | |||

| === War for the Lands of the Bohemian Crown (1468–1479) === | |||

| {{Further|Bohemian War (1468–1478)}} | |||

| ] (attributed to), ] (previous attribution) 1476)]] | |||

| Matthias's former brother-in-law ] invaded Austria in early 1468.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=85}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=304}} Emperor Frederick appealed to Matthias for support, hinting at the possibility of Matthias's election as ], the first step towards the imperial throne.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=85}} Matthias declared war on Victor's father King George of Bohemia on 31 March.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=304}} He said he also wanted to help the Czech Catholic lords against their "heretic monarch", whom the Pope had ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|pp=100, 103}} Matthias expelled the Czech troops from Austria and invaded Moravia and ].{{sfn|Šmahel|2011|p=167}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=304}} He took an active part in the fighting; he was injured during the siege of ] in May 1468 and was captured at ] while spying out the enemy camp in disguise in February 1469.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=86}} On the latter occasion, he was released because he made his custodians believe he was a local Czech groom.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=86}} | |||

| The Diet of 1468 authorized Matthias to levy an extraordinary tax to finance the new war but only after 8 prelates and 13 secular lords pledged on the King's behalf that he would not demand such charges in the future.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=88}} Matthias also exercised ] to increase his revenues.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=88}} For instance, he ordered a Palatine's ] in a county, the cost of which were to be covered by the local inhabitants, but he soon authorised the county to redeem the cancellation of the irksome duty.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=88}} | |||

| The Czech Catholics, who were led by ], joined forces with Matthias in February 1469.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=103}} Their united troops were encircled at ] by George of Poděbrady's army.{{sfn|Šmahel|2011|p=167}}{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=65}} In fear of being captured, Matthias opened negotiations with his former father-in-law.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=65}} They met in a nearby hovel in which Matthias persuaded George of Poděbrady to sign an armistice promising that he would mediate a reconciliation between the ] and the Holy See.{{sfn|Šmahel|2011|p=167}}{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=65}} Their next meeting took place in Olomouc in April.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=103}} Here the papal legates came forward with demands including the appointment of a Catholic Archbishop to the ], which could not be accepted by George of Poděbrady.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=65}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=103}} | |||

| The Czech Catholic Estates elected Matthias King of Bohemia in Olomouc on 3 May but he was never crowned.{{sfn|Šmahel|2011|pp=167–168}}{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=66}} Moravia, Silesia and ] soon accepted his rule but Bohemia proper remained faithful to George of Poděbrady.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=104}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=87}} The Estates of Bohemia even acknowledged the right of ], the eldest son of Casimir IV of Poland, to succeed king George of Poděbrady.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=104}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} | |||

| ] | |||

| Matthias's relations with Frederick III had in the meantime deteriorated because the Emperor accused Matthias of allowing the Ottomans to march through Slavonia when raiding the Emperor's realms.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=87}} The ] family, whose domains in Croatia were exposed to Ottoman raids, entered into negotiations with the Emperor and the Republic of Venice.{{sfn|Magaš|2007|pp=76–77}}{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=590}} In 1469, Matthias sent an army to Croatia to prevent the Venetians from seizing the Adriatic coastal town ].{{sfn|Magaš|2007|p=77}} | |||

| Matthias expelled George of Poděbrady's troops from Silesia.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=104}} Matthias's army was encircled and routed at ] on 2 November, forcing him to withdraw to Hungary.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} Matthias soon ordered the collection of an extraordinary tax without holding a Diet, raising widespread discontent among the Hungarian Estates.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=90}} He visited Emperor Frederick in Vienna on 11 February 1470, hoping the Emperor would contribute to the costs of the war against Poděbrady.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=89}} Although the negotiations lasted for a month, no compromise was worked out.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=89}} The Emperor also refused to commit himself to promoting Matthias's election as King of the Romans.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=89}} After a month, Matthias left Vienna without taking formal leave of Frederick III.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=79}} | |||

| Having realised the Hungarian Estates' growing dissatisfaction, Matthias held a Diet in November.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=90}} The Diet again authorized him to levy an extraordinary tax, stipulating that the sum of all taxes payable per ''porta'' could not exceed one florin.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=90}} The Estates also made it clear that they opposed the war in Bohemia.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=90}} George of Poděbrady died on 22 March 1471.{{sfn|Šmahel|2011|p=168}} The Diet of Bohemia proper elected Vladislaus Jagiello king on 27 May.{{sfn|Boubín|2011|pp=173–174}} The papal legate Lorenzo Roverella soon declared Vladislaus's election void and confirmed Matthias's position as King of Bohemia, but the ] refused Matthias's claim.{{sfn|Boubín|2011|p=174}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=108}} | |||

| Matthias was staying in Moravia when he was informed that a group of Hungarian prelates and barons had offered the throne to ], a younger son of King Casimir IV of Poland.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=70}} The conspiracy was initiated by Archbishop John Vitéz and his nephew ], ], who opposed war against the Catholic Vladislaus Jagiellon.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=91–92}} Initially, their plan was supported by the majority of the Estates, but nobody dared to rebel against Matthias, enabling him to return to Hungary without resistance.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=92}} Matthias held a Diet and promised to refrain from levying taxes without the consent of the Estates and to convoke the Diet in each year.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=70}} His promises remedied most of the Estates' grievances and almost 50 barons and prelates confirmed their loyalty to him on 21 September.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=92–93}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=158}} Casimir Jagiellon invaded on 2 October 1471.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} With Bishop Janus Pannonius's support, he seized Nyitra (now ] in Slovakia), but only two barons, ] and Nicholas Perényi, joined him.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=158}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=93}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=305}} Within five months Prince Casimir withdrew from Hungary, Bishop Janus Pannonius died while fleeing, and Archbishop John Vitéz was forbidden to leave his see.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=158}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=93}} Matthias appointed the Silesian ] to administer the ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=158}} Vitéz died and Beckensloer succeeded him in a year.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=93}} | |||

| The Ottomans had meanwhile seized the Hungarian forts along the river Nertva.{{sfn|Fine|1994|p=588}} Matthias nominated the wealthy baron Nicholas Újlaki as King of Bosnia in 1471, entrusting the defence of the province to him.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=93}} ], head of the ] ], proposed an anti-Ottoman alliance to Matthias but he refrained from attacking the Ottoman Empire.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=108}} Matthias supported the Austrian noblemen who rebelled against Emperor Frederick in 1472.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=95–96}} The following year, Matthias, Casimir IV and Vladislaus entered into negotiations on the terms of a peace treaty, but the discussions lasted for months.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=305}} Matthias tried to unify the government of Silesia, which consisted of ], through appointing a captain-general.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=101}} However, the Estates refused to elect his candidate Duke ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=101}} | |||

| ]: 1. ]'s ], 2. ], 3. ], and 4. ]) and that of his wife ] (]: 1. and 4. ] – France ancient – ] ]; 2. and 3. Aragon), above them a royal crown. On the outer edge there are coat of arms of various lands, beginning from the top clockwise they are: Bohemia, Luxemburg, Lower Lusatia, Moravia, Austria, Galicia–Volhynia, Silesia, Dalmatia-Croatia, ]]] | |||

| ], ], pillaged eastern parts of Hungary, destroyed Várad, and took 16,000 prisoners with him in January 1474.{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=307–308}} The next month, the envoys of Matthias and Casimir IV signed a peace treaty and a three-year truce between Matthias and Vladislaus Jagiellon was also declared.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=96}} Within a month, however, Vladislaus entered into an alliance with Emperor Frederick and Casimir IV joined them.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=96}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=305}} Casimir IV and Vladislaus invaded Silesia and laid siege to Matthias in Breslau (now ] in Poland) in October.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=305}} He prevented the besiegers from accumulating provisions, forcing them to raise the siege.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=97}} Thereafter the Silesian Estates willingly elected Matthias's new candidate Stephen Zápolya as captain-general.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=101}} The Moravian Estates elected Ctibor Tovačovský as captain-general.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=100}} Matthias confirmed this decision, although Tovačovský had been Vladislaus Jagiellon's partisan.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=100}} | |||

| The Ottomans invaded Wallachia and Moldavia at the end of 1474.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=109}} Matthias sent reinforcements under the command of ] to Stephen the Great.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=308}} Their united forces routed the invaders in the ] on 10 January 1475.{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=267}} Fearing a new Ottoman invasion, the Prince of Moldavia swore fealty to Matthias on 15 August.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=109}} Sultan Mehmed II proposed peace but Matthias refused him.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=109}} Instead, he stormed into Ottoman territory and captured ], an important fort on the river Száva, on 15 February 1476.{{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=325}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=110}} During the siege, Matthias barely escaped capture while he was watching the fortress from a boat.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=176}} | |||

| For unknown reasons, Archbishop Johann Beckensloer left Hungary, taking the treasury of the Esztergom See with him in early 1476.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=97}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|pp=305–306}} He fled to Vienna and offered his funds to the Emperor.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=92}} Matthias accused the Emperor of having incited the Archbishop against him.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=92}} | |||

| Mehmed II launched a campaign against Moldavia in the summer of 1476.{{sfn|Pop|2005|p=267}} Although he won the ] on 26 July, the lack of provisions forced him to retreat.{{sfn|Babinger|1978|pp=351–352}} Matthias sent auxiliary troops to Moldavia under the command of Vlad Dracula, whom he had released, and ] {{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=110}}{{sfn|Florescu|McNally|1989|pp=170–171}} The allied forces defeated an Ottoman army at the ] in August.{{sfn|Florescu|McNally|1989|p=171}} With Hungarian and Moldavian support, Vlad Dracula was reinstalled as Prince of Wallachia but he was killed fighting against his opponent ].{{sfn|Florescu|McNally|1989|pp=171–175}}{{sfn|Pop|2005|pp=264–265}} | |||

| Matthias's bride ] arrived in Hungary in late 1476.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=136}} Matthias married her in Buda on 22 December that year.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=136}} The Queen soon established a rigid etiquette, making direct contacts between the King and his subjects more difficult.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=137}} According to Bonfini, Matthias also "improved his board and manner of life, introduced sumptuous banquets, disdaining humility at home and beautified the dining rooms" after his marriage.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=108}} According to a contemporaneous record, around that time Matthias's revenues amounted about 500,000 florins, half of which derived from the tax of the royal treasury and the extraordinary tax.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=67}} | |||

| Matthias concluded an alliance with the ] and the ] against Poland in March 1477.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=97}} However, instead of Poland, he declared war on Emperor Frederick after he learnt that the Emperor had confirmed Vladislaus Jagiellon's position as King of Bohemia and ].{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=97}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=306}} Matthias invaded ] and imposed a blockade on Vienna.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=98}} Vladislaus Jagiellon denied to support the Emperor, forcing him to seek reconciliation with Matthias.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=98}} With the mediation of ], Venice, and ], Matthias concluded a peace treaty with Frederick III, which was signed on 1 December.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=98}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=118}} The Emperor promised to confirm Matthias as the lawful ruler of Bohemia and to pay him an indemnity of 100,000 florins.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=306}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=98}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=119}} They met in ] where Frederick III installed Matthias as King of Bohemia and Matthias swore loyalty to the Emperor.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=120}} | |||

| Negotiations between the envoys of Matthias and Vladislaus Jagiellon accelerated during the next few months.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=109}} The first draft of a treaty was agreed upon on 28 March 1478, and the text was completed by the end of 1477.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=53}} The treaty authorized both monarchs to use the title of King of Bohemia although Vladislaus could omit to style Matthias as such in their correspondence, and the ] were divided between them. Vladislaus ruled in Bohemia proper and Matthias in Moravia, Silesia and Lusatia.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=97}}{{sfn|Boubín|2011|p=174}} They solemnly ratified the peace treaty at their meeting in Olomouc on 21 July.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=53}} | |||

| ===War for Austria (1479–1487)=== | |||

| {{Further|Austrian–Hungarian War (1477–1488)|Siege of Vienna (1485)|Siege of Wiener Neustadt}} | |||

| ] of Matthias Corvinus, guarded by ] heavy infantry. ], Budapest. The damaged art relic was renovated in 1893.]] | |||

| Emperor Frederick only paid off half of the indemnity due to Matthias according to their treaty of 1477.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=120}}{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=65}} Matthias concluded a treaty with the ] on 26 March 1479, hindering the recruitment of Swiss mercenaries by the Emperor.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=120}} He also entered into an alliance with ] ], who allowed him to take possession of the fortresses of the Archbishopric in ], ] and ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=306}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=99}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=122}} | |||

| An Ottoman army supported by ] of Wallachia invaded Transylvania and set fire to Szászváros (now ] in Romania) in late 1479.{{sfn|Dörner|2005|p=318}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=308}} Stephen Báthory and ] annihilated the marauders in the ] on 13 October.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=308}}{{sfn|Babinger|1978|pp=374–376}} Matthias united the command of all forts along the Danube to the west of Belgrade in the hand of Paul Kinizsi to improve the defence of the southern frontier.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=309}} Matthias sent reinforcements to Stephen the Great, who invaded pro-Ottoman Wallachia in early 1480; Matthias launched a campaign as far as ] in Bosnia in November.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=142}}{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=308}} He set up five defensive provinces, or banates, centred around the forts of ] (now Drobeta-Turnu Severin in Romania), ], ], ] and ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=309}} The next year, Matthias initiated a criminal case against the Frankapans, the ]s and other leading Croatian and Slavonian magnates for their alleged participation in the 1471 conspiracy.{{sfn|Magaš|2007|p=77}} Most barons were pardoned as soon as they consented to the introduction of a new land tax.{{sfn|Magaš|2007|p=77}} In 1481, for a loan of 100,000 florins, Matthias seized the town of ] in Styria and ] in Lower Austria from ], one of the two candidates to the ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=122}} | |||

| Sultan Mehmed II died on 3 May 1481.{{sfn|Babinger|1978|p=404}} A civil war ensued in the Ottoman Empire between his sons ] and ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=143}} Defeated, Cem fled to ], where the ] kept him in custody.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=143}} Matthias claimed Cem's custody in the hope of using him to gain concessions from Bayezid, but Venice and ] strongly opposed this plan.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=143}} In late 1481, Hungarian auxiliary troops supported Matthias's father-in-law Ferdinand I of Naples to reoccupy ], which had been lost to the Ottomans the year before.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=112}} | |||

| Although the "Black Army" had already laid siege to ] in January 1482, Matthias officially declared a new war on Emperor Frederick three months later.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=306}} He directed the siege in person from the end of June and the town fell to him in October.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=125}} In the next three months, Matthias also captured ], ], and ].{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=125}} The papal legate, Bartolomeo Maraschi tried to mediate a peace treaty between Matthias and the Emperor, but Matthias refused.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=125}} Instead, he signed a five-year truce with Sultan Bayezid.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=112}} | |||

| Matthias's marriage to Beatrice of Naples did not produce sons; he tried to strengthen the position of his illegitimate son ].{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=317}} The child received Sáros Castle and inherited the extensive domains of his grandmother Elizabeth Szilágyi with his father's consent.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=317}} Matthias also forced Victor of Poděbrady to renounce the ] in Silesia in favour of John Corvinus in 1485.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=143}} Queen Beatrice opposed Matthias's favouritism towards his son.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=143}} Even so, Matthias nominated her eight-year-old nephew ] Archbishop of Esztergom.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=313}} The Pope refused to confirm the child's appointment for years.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=138}} The "Black Army" encircled Vienna in January 1485.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=127}} The siege lasted for five months and ended with the triumphal entry of Matthias, at the head of 8,000 veterans, into Vienna on 1 June.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=127}} The King soon moved the royal court to the newly conquered town.{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=53}} He summoned the Estates of Lower Austria to Vienna and forced them to swear loyalty to him.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=102}} | |||

| {{Quote box|align=upright|width=30%|Matthias, by the grace of God, king of Hungary, Bohemia, Dalmatia, Croatia, ], Serbia, Galicia, Lodomeria, Cumania, and Bulgaria, Duke of Silesia and Luxemburg and Margrave of Moravia and Lusatia, for the everlasting memory of the matter. It is fitting that kings and princes who by heavenly decree are placed at the summit of the highest office, be adorned not only by arms but also by laws and that the people subjected to them, as well as the reins of authority, are restrained by the strength of good and stable institutions rather than by the harshness of absolute power and reprehensible abuse.|''Preamble to the Decretum Maius''{{sfn|Bak|Domonkos|Harvey|Garay|1996|p=41}}}} | |||

| Upon the monarch's initiative, the Diet of 1485 passed the so-called ''Decretum maius'', a systematic law-code which replaced many previous contradictory decrees.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=316}}{{sfn|Bak|1994|p=74}} The law-code introduced substantial reforms in the administration of justice; the Palatine's eyre and the extraordinary county assemblies were abolished, which strengthened the position of the county courts.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=316}} Matthias also decreed that in cases of the monarch's absence or minority, the Palatine was authorized to rule as Regent.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=316}} | |||

| Emperor Frederick persuaded six of the seven Prince-electors of the Holy Roman Empire to proclaim his son ] King of the Romans on 16 February 1486.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=146}} The Emperor, however, had failed to invite the King of Bohemia, }either Matthias or Vladislaus Jagiellon, to the assembly.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=146}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=109}} In an attempt to prevail on Vladislaus to protest, Matthias invited him to a personal meeting.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=109}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=147}} Although they formed an alliance in ] in September, the Estates of Bohemia refused to confirm it and Vladislaus recognized Maximilian's election.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=147}} | |||

| In the meantime Matthias continued his war against the Emperor.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=128}} The "Black Army" seized several towns in Lower Austria, including ], and ] in 1485 and 1486.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=128}} He set up his chancery for Lower Austria in 1486, but he never introduced a separate seal for this realm.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=102}} Matthias assumed the title of Duke of Austria at the Diet of the Lower Austrian Estates in ] in 1487.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=103}} He appointed Stephen Zápolya captain-general, ] administrator of the ], and entrusted the defence of the occupied towns and forts to Hungarian and Bohemian captains, but otherwise continued to employ Emperor Frederick's officials who accepted his rule.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=103}}{{sfn|Markó|2006|p=242}} Wiener Neustadt, the last town resisting Matthias in Lower Austria, fell to him on 17 August 1487.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=306}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=128}} | |||

| He started negotiations with Duke Albert III of Saxony, who arrived at the head of the imperial army to fight for Emperor Frederick III.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=128}} They signed a six-month armistice in Sankt Pölten on 16 December, which ended the war.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=128}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=54}} Matthias offered Emperor Frederick and his son prince Maximilian, the return of Austrian provinces and Vienna, if they would renounce the treaty of 1463 and accept Matthias as Frederic's designated heir and probable the inheritor of the title of Holy Roman Emperor. Before this was settled though, Matthias died in Vienna in 1490.<ref>{{cite book|author=Alexander Gillespie|title=The Causes of War: Volume III: 1400 CE to 1650 CE|publisher=]|page=66|year=2017|isbn=9781509917662|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=i3UpDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA66}}</ref> | |||

| King Matthias was happy to be described as "the second Attila".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Malcolm |first=Noel |title=Useful Enemies: Islam and The Ottoman Empire in Western Political Thought, 1450-1750 |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=2019 |isbn=978-0198830139 |quote=}}</ref> The '']'' by ] published in 1488, set the goal of glorifying ], which was undeservedly neglected, moreover, he introduced the famous "Scourge of God" characterization to the later Hungarian writers, because the earlier chronicles remained hidden for a long time. Thuróczy worked hard to endear Attila, the Hun king with an effort far surpassing his predecessor chroniclers. He made Attila a model for his victorious ruler, King Matthias who had Attila's abilities, with this he almost brought "the hammer of the world" to life.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Dr. Szabados |first=György |url=http://real-j.mtak.hu/13031/1/EPA00001_ITK_1998_05-06.pdf |title=Irodalomtörténeti Közlemények, 102 (5-6) |publisher=MTA Irodalomtudományi Intézet (Institute for Literary Studies of Hungarian Academy of Sciences) |year=1998 |pages=615–641 |language=Hungarian |chapter=A krónikáktól a Gestáig – Az előidő-szemlélet hangsúlyváltásai a 15–18. században |trans-chapter=From the chronicles to the Gesta - Shifts in emphasis of the pre-time perspective in the 15th–18th centuries |issn=0021-1486 |chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/28283729}}</ref> | |||

| ===Last years (1487–1490)=== | |||

| ] | |||

| According to the contemporaneous ], Matthias's subjects feared their king in the last years of his life because he rarely showed mercy towards those he suspected of treachery.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=132}} He had Archbishop Peter Váradi imprisoned in 1484 and ordered the execution of Chancellor of Bohemia Jaroslav Boskovic in 1485.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=121, 132}}{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=310}} He also imprisoned Nicholas Bánfi, a member of a magnate family, in 1487, although he had earlier avoided punishing the old aristocracy.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=122}} Bánfi's imprisonment seems to have been connected to his marriage to a daughter of ], ] because Matthias tried to seize this duchy for John Corvinus.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=122}} John the Mad entered into an alliance with the ] ], and declared a war on Matthias on 9 May.{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=315}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=110}} Six month later, the Black Army invaded and occupied his duchy.{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=315}} | |||

| In the meantime, the citizens of ], a town in the ], hoisted Matthias's flag in the hope he would protect them against Venice.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=149}} Pope Innocent VIII soon protested, but Matthias refused to reject the overture and stated that the link between him and the town would never harm the interests of the Holy See.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=149}} He also sent an auxiliary troop to his father-in-law, who was waging a war against the Holy See and Venice.{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=314}} The 1482 truce between Hungary and the Ottoman Empire was prolonged for two years in 1488.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|pp=144–145}}{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=315}} On this occasion, it was stipulated that the Ottomans were to refrain from invading Wallachia and Moldavia.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|pp=144–145}} The following year, Matthias granted two domains to Stephen the Great of Moldavia in Transylvania.{{sfn|Dörner|2005|p=318}} | |||

| Matthias, who suffered from ], could not walk and was carried in a ] after March 1489.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=149}}{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=138}} Hereafter, his succession caused bitter conflicts between Queen Beatrice and John Corvinus.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=138}} Matthias asked Beatrice's brother ], ], to persuade her not to strive for the Crown and stated that the "Hungarian people are capable of killing up unto the last man rather than submit to the government of a woman".{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=137}}{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=316}} To strengthen his illegitimate son's position, Matthias even proposed withdrawing from Austria and confirming Emperor Frederick's right to succeed him if the Emperor was willing to grant Croatia and Bosnia to John Corvinus with the title of king.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=148}}{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=316}} | |||

| Matthias participated in the lengthy ] ceremony in Vienna in 1490 although he had felt so ill that morning that he could not eat breakfast.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=149}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=187}} Around noon, he tasted a fig that proved to be rotten and he became very agitated and suddenly felt faint.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=150}} The next day he was unable to speak.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=150}} After two days of suffering, Matthias died in the morning of 6 April.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=150}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=187}} According to Professor ], Matthias died of a stroke; Dr. Herwig Egert does not exclude the possibility of poisoning.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=150}} Matthias's funeral was held in ] and he was buried in ] on 24 or 25 April 1490.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=150–151}}{{sfn|Teke|1981|p=317}} | |||

| This popularity is partially mirrored in modern ]: 19th century ] invested in Matthias and his fathers' Vlach origins, their Christian warrior stances, and their cultural achievements. | |||

| ] (], 1902).]] | |||

| ==Patronage== | ==Patronage== | ||

| ===Renaissance king=== | |||

| ] triumphed in ] in 1485]] | |||

| Matthias was the first non-Italian monarch promoting the spread of Renaissance style in his realm.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=161}}{{sfn|Klaniczay|1992|p=165}} His marriage to Beatrice of Naples strengthened the influence of contemporaneous Italian art and scholarship,{{sfn|Cartledge|2011|p=67}} and it was under his reign that Hungary became the first land outside Italy to embrace the Renaissance.{{sfn|Waldman|Farbaky|2011|p=Abstract}} The earliest appearance of Renaissance style buildings and works outside Italy were in Hungary.{{sfn|Johnson|2007|p=175}}{{sfn|Kaufmann|1995|p=30}} The Italian scholar ] introduced Matthias to ]'s ideas of a ] uniting wisdom and strength in himself, which fascinated Matthias.{{sfn|Cacioppe|2007}} Matthias is the main character in ]'s ''Republics and Kingdoms Compared'', a dialogue on the comparison of the two forms of government.{{sfn|Rubinstein|1991|p=35}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=164}} According to Brandolini, Matthias said a monarch "is at the head of the law and rules over it" when summing up his own concepts of state.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=164}} | |||

| Matthias also cultivated traditional art.{{sfn|Klaniczay|1992|p=173}} Hungarian ]s and lyric songs were often sung at his court.{{sfn|Klaniczay|1992|p=173}} He was proud of his role as the defender of Roman Catholicism against the Ottomans and the Hussites.{{sfn|Klaniczay|1992|p=168}} He initiated theological debates, for instance on the doctrine of the ], and surpassed both the Pope and his legate "with regard to religious observance", according to the latter.{{sfn|Tanner|2009|p=99}} Matthias issued coins in the 1460s bearing an image of the ], demonstrating his special devotion to her cult.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=184}} | |||

| Matthias was educated in ], and his fascination with the achievements of the ] led to the promotion of ] cultural influences in Hungary. ], ], ] and ] were amongst the towns in Hungary that benefited from the establishment of ] and education and a new legal system under Matthias' rule. In 1465 he founded a university in ] (present-day ], ]), the ]. His 1476 marriage to Beatrice, the daughter of the King of Naples, only intensified the influence of the ]. | |||

| Upon Matthias's initiative, Archbishop John Vitéz and Bishop Janus Pannonius persuaded Pope Paul II to authorize them to set up a university in ] (now ] in Slovakia) on 29 May 1465.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=182}}{{sfn|Bartl|Čičaj|Kohútova|Letz|2002|p=52}} The '']'' was closed shortly after the Archbishop's death.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=169}}{{sfn|Bak|1994|p=75}} Matthias was contemplating establishing a new university in Buda but this plan was not accomplished.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=169}} | |||

| An indefatigable reader and lover of culture, he proved an extremely generous ], as artists from the ] (such as ]) and ] were present in large numbers at his court. | |||

| ===Building projects and arts=== | |||

| Like many of his acculturated contemporaries, he trusted in astrology and other semi-scientific beliefs; however, he also supported true scientists and engaged frequently in discussions with philosophers and scholars. | |||

| {{Further|Buda Castle|Visegrád}} | |||

| Matthias started at least two major building projects.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|pp=177, 180–181}} The works in Buda and ] began in about 1479.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=319}} Two new wings and a ] were built at the royal castle of Buda, and the palace at Visegrád was rebuilt in Renaissance style.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=319}}{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|pp=180–181}} Matthias appointed the Italian ] and the Dalmatian ] to direct these projects.{{sfn|Engel|2001|p=319}} | |||

| He spoke ], ], ], ], and later also ], ]. | |||

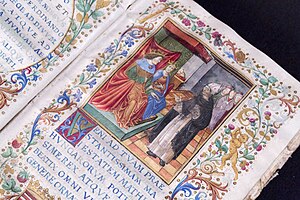

| Matthias commissioned the leading Italian artists of his age to embellish his palaces: for instance, the sculptor ] and the painters ] and ] worked for him.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|pp=171–172}} A copy of Mantegna's portrait of Matthias survived.{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=172}} In the spring of 1485, Matthias decided to commission ] to paint a ] to him.{{sfn|Verspohl|2007|p=151}} Matthias also hired the Italian military engineer ] to direct the rebuilding of the forts along the southern frontier.{{sfn|E. Kovács|1990|p=181}} He had new monasteries built in ] style for the ] in Kolozsvár, ] and Hunyad, and for the ] in Fejéregyháza.{{sfn|Klaniczay|1992|p=168}}{{sfn|Kubinyi|2008|p=183}} | |||

| ==Royal library== | |||

| Matthias Corvinus's library, the ''Bibliotheca Corviniana'', was among Europe's greatest collections of secular historical chronicles and philosophic and scientific works in the fifteenth century.<ref>Marcus Tanner, The Raven King: Matthias Corvinus and the Fate of his Lost Library (New Haven: Yale U.P., 2008)</ref> Corvinus's library is part of UNESCO World Heritage <ref>http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/ev.php-URL_ID=15976&URL_DO=DO_TOPIC&URL_SECTION=201.html</ref>. In 1489, ] of Florence wrote that ] founded his own Greek-Latin library encouraged by the example of the Hungarian king. | |||