| Revision as of 17:38, 6 December 2005 view source205.240.227.15 (talk) →The character← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:09, 27 December 2024 view source Canterbury Tail (talk | contribs)Administrators86,736 edits Rv no sources or evidence provided that this is considered part of the James Bond franchise. Take it to the talk page for consensus. And don't refer to another editor as your brother.Tag: Manual revert | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Media franchise about a British spy}} | |||

| {{otheruses}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Italic title}} | ||

| {{About|the series|the character |James Bond (literary character)|other uses|James Bond (disambiguation)}} | |||

| '''James Bond''', also known as '''007''' (pronounced "double-oh seven"), is a ] ] ] introduced by writer ] in ]. Fleming wrote numerous novels and short stories based upon the character and, after his death in ], further literary adventures were written by ] (pseudonym "]"), ], ], ], and ]; in addition, ] wrote two screenplay novelizations and other authors have also written various unofficial permutations of the character. | |||

| {{Redirect|007|other uses|007 (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Good article}} | |||

| Although initially made famous through the novels, James Bond is now probably best known from the ] film series. Twenty official and two unofficial films have been made featuring this character. ] and ] produced most of the official films up until ] when Broccoli became the sole producer. His daughter, ], and his stepson, ], carried on the production duties beginning in ]. | |||

| {{Pp-semi|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=February 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox media franchise | |||

| |title = James Bond | |||

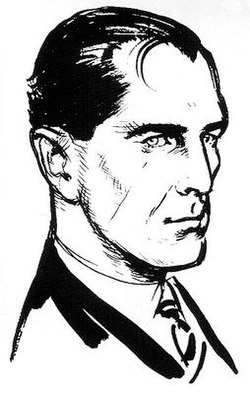

| |image = Fleming007impression.jpg | |||

| |caption = Ian Fleming's image of James Bond; commissioned to aid the '']'' comic strip artists | |||

| |creator = ] | |||

| |origin = '']'' (1953) | |||

| |owner = ] | |||

| |years = 1953–present | |||

| |books = | |||

| |novels = ] | |||

| |short_stories = See list of novels | |||

| |comics = ] | |||

| |graphic_novels = | |||

| |strips = '']'' (1958–1983) | |||

| |magazines = | |||

| |films = ] | |||

| |shorts = ''Happy and Glorious'' (2012) | |||

| |tv = "]" ('']'' season 1 – episode 3) (1954) | |||

| |atv = '']'' (1991–1992) | |||

| |tv_specials = | |||

| |tv_films = | |||

| |dtv = | |||

| |plays = | |||

| |musicals = | |||

| |games = Various | |||

| |rpgs = '']'' | |||

| |vgs = ] | |||

| |radio = ] | |||

| |soundtracks = | |||

| |music = ] | |||

| |toys = Various | |||

| |otherlabel1 = Portrayers | |||

| |otherdata1 = {{Plainlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |otherlabel2 = | |||

| |otherdata2 = | |||

| |otherlabel3 = | |||

| |otherdata3 = | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''''James Bond''''' franchise focuses on ], a fictional ] agent created in 1953 by writer ], who featured him in twelve novels and two short-story collections. Since Fleming's death in 1964, eight other authors have written authorised Bond novels or novelisations: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. The latest novel is ''With a Mind to Kill'' by Anthony Horowitz, published in May 2022. Additionally, ] wrote a series on ], and ] wrote three novels based on the ], ]. | |||

| To date, six actors have been signed to portray 007 in the official series (in chronological order): | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *], announced October 2005 | |||

| The character—also known by the code number '''007''' (pronounced "double-oh-seven")—has also been adapted for television, radio, comic strips, video games and film. The films constitute one of the longest continually running film series and have grossed over US$7.04 billion in total at the box office, making ''James Bond'' the ] to date, which started in 1962 with '']'', starring ] as Bond. {{As of|2021}}, there have been twenty-five films in the ] ]. The most recent Bond film, '']'' (2021), stars ] in his fifth portrayal of Bond; he is the sixth actor to play Bond in the Eon series. There have also been two independent Bond film productions: '']'' (a 1967 ] starring ]) and '']'' (a 1983 remake of an earlier Eon-produced film, 1965's '']'', both starring Connery). The ''James Bond'' franchise is one of the ]. ''Casino Royale'' has also been adapted for television, as a one-hour show in 1954 as part of the CBS series '']''. | |||

| The 21st official film, '']'', is in pre-production and is slated for a ], ], release with Craig as Bond. | |||

| The Bond films are renowned for a number of features, including ], with the theme songs having received ] nominations on several occasions, and three wins. Other important elements which run through most of the films include Bond's cars, his guns, and the gadgets with which he is supplied by ]. The films are also noted for Bond's relationships with various women, who are popularly referred to as "]s". | |||

| Broccoli's family company, ], has co-owned the James Bond film series with ] Corporation since the mid-1970s, when Saltzman sold UA his share of Danjaq. Currently, ] and ] (United Artists' parent) co-distribute the series. | |||

| == Publication history == | |||

| Two other James Bond films were made independently of EON: the comedy '']'' starring ] (]), and '']'', a remake of '']'' starring Sean Connery (]). An ] television adaptation of Fleming's first novel, ''Casino Royale'', also aired in ] starring ]. These three productions, not having originated with EON, are not considered to be official Bond films, although MGM/Sony now owns the distribution rights to them | |||

| === Creation and inspiration === | |||

| {{Main|James Bond (literary character)|Inspirations for James Bond}} | |||

| Ian Fleming created the fictional character of James Bond as the central figure for his works. Bond is an intelligence officer in the ], commonly known as MI6. Bond is known by his code number, 007, and was a ] ]. Fleming based his fictional creation on a number of individuals he came across during his time in the ] and ] during the Second World War, admitting that Bond "was a compound of all the secret agents and commando types I met during the war".<ref name="Macintyre (2008b)" /> Among those types were his brother, ], who had been involved in behind-the-lines operations in ] and ] during the war.<ref name="PF Obit (1971)">{{cite news|title=Obituary: Colonel Peter Fleming, Author and explorer|newspaper= The Times|date=20 August 1971|page=14}}</ref> Aside from Fleming's brother, a number of others also provided some aspects of Bond's make up, including ], ], ] and ].<ref name="Macintyre (2008b)" /><ref>{{cite web |last1=Hall |first1=Chris |title=From the archive: the real James Bond, 1973 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2020/mar/22/from-the-archive-the-real-james-bond-1973-dusko-popov-ian-fleming |work=The Guardian |access-date=28 February 2023 |date=22 March 2020}}</ref> | |||

| In addition to novels and films, Bond is a prominent character in many ], ] and ] and has been the subject of many ]. | |||

| The name James Bond came from that of the American ] ], a Caribbean bird expert and author of the definitive ] '']''. Fleming, a keen ] himself, had a copy of Bond's guide and he later explained to the ornithologist's wife that "It struck me that this brief, unromantic, Anglo-Saxon and yet very masculine name was just what I needed, and so a second James Bond was born".<ref>{{cite news |title=James Bond, Ornithologist, 89; Fleming Adopted Name for 007 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/17/obituaries/james-bond-ornithologist-89-fleming-adopted-name-for-007.html |access-date=22 August 2019 |newspaper=The New York Times |date=17 February 1989 |archive-date=2 May 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190502204215/https://www.nytimes.com/1989/02/17/obituaries/james-bond-ornithologist-89-fleming-adopted-name-for-007.html |url-status=live }}</ref> He further explained that: | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ]'' comic strip artists.]] | |||

| ===The character=== | |||

| Commander James Bond is a member of ], the international arm of the British Secret Service, under which he holds the code number "007". The 'double-oh' prefix indicates his discretionary ] in the performance of his duties. | |||

| {{Blockquote|text= When I wrote the first one in 1953, I wanted Bond to be an extremely dull, uninteresting man to whom things happened; I wanted him to be a blunt instrument ... when I was casting around for a name for my protagonist I thought by God, is the dullest name I ever heard.|sign= Ian Fleming|source='']'', 21 April 1962<ref name="Hellman (1962)">{{cite magazine |last= Hellman |first= Geoffrey T. |title= Bond's Creator |url= https://www.newyorker.com/archive/1962/04/21/1962_04_21_032_TNY_CARDS_000268062 |id= section "Talk of the Town" |magazine= The New Yorker |access-date= 9 September 2011 |author-link= Geoffrey T. Hellman |page= 32 |date= 21 April 1962 |archive-date= 21 January 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120121095936/http://www.newyorker.com/archive/1962/04/21/1962_04_21_032_TNY_CARDS_000268062 |url-status= live }}</ref>}} | |||

| Fleming named James Bond after an ] who had written '']''. Fleming, a keen ], was in ] with a copy of Bond's field guide when he chose Bond's name for the lead character of his first novel, '']'' in ]. He later explained that the man's name was "brief, unromantic, ], and yet very masculine… just what I needed." | |||

| On another occasion, Fleming said: "I wanted the simplest, dullest, plainest-sounding name I could find, 'James Bond' was much better than something more interesting, like 'Peregrine Carruthers'. Exotic things would happen to and around him, but he would be a neutral figure—an anonymous, blunt instrument wielded by a government department."{{sfn|Chancellor|2005|p=112}} | |||

| The look of James Bond is famed for being "suave and sophisticated." In ''Casino Royale'' the character ] says of Bond, "He reminds me rather of ], but there is something cold and ruthless." Carmichael would later be the basis as James Bond for artist ] and his series of James Bond ]s, while the Hoagy Carmichael description would be repeated in later Bond stories written by John Gardner. | |||

| ]—Fleming's view of James Bond]] | |||

| Fleming drew inspiration for the Bond character from his personal life; the author was known for his jetsetting lifestyle and reputation as a ]. Fleming was also inspired by his contemporaries in British Intelligence during ], specifically events that were purported to have taken place at the ] in ], ], where spies of warring regimes mingled with ] royalty. One wonders if the real life assassin-agent ], who had a similar character was known to Ian Fleming. This atmosphere inspired Fleming's imagination and set the scene for his first Bond novel, ''Casino Royale''. (See ].) | |||

| Fleming decided that Bond should resemble both American singer ] and himself{{sfn|Macintyre|2008|p=67}} and in ], ] remarks, "Bond reminds me rather of Hoagy Carmichael, but there is something cold and ruthless." Likewise, in ], ] officer ] thinks that Bond is "certainly good-looking ... Rather like Hoagy Carmichael in a way. That black hair falling down over the right eyebrow. Much the same bones. But there was something a bit cruel in the mouth, and the eyes were cold."{{sfn|Macintyre|2008|p=67}} | |||

| Bond is the consummate womaniser, drinker, and smoker. According to a detailing Bond’s drinking habits, the agent consumed 102 ]s in the films, and well over 300 in Fleming's novels. On film, Bond drinks ] 32 times, and 20 vodka ]. In the novels, he has a strong preference for ]. | |||

| Fleming endowed Bond with many of his own traits, including sharing the same golf handicap, the taste for scrambled eggs, and using the same brand of toiletries.{{sfn|Macintyre|2008|p=50}} Bond's tastes are also often taken from Fleming's own as was his behaviour,<ref name="Cook (2004)">{{cite news |last=Cook |first=William |title=Novel man |newspaper=] |date=28 June 2004|page=40}}</ref> with Bond's love of golf and gambling mirroring Fleming's own. Fleming used his experiences of his career in espionage and all other aspects of his life as inspiration when writing, including using names of school friends, acquaintances, relatives and lovers throughout his books.<ref name="Macintyre (2008b)" /> | |||

| The literary 007 is a heavy ] smoker, at one point smoking up to 60 a day. Bond quit smoking when Gardner authored the stories in the 1980s. On film, Bond has been off and on. During both the Connery and Dalton films Bond was a smoker, while during Moore's and Brosnan's tenure he doesn't smoke cigarettes, although he does occasionally smoke ]s. The last time Bond used cigarettes in film was in '']''. | |||

| It was not until the penultimate novel, '']'', that Fleming gave Bond a sense of family background. The book was the first to be written after the release of ] in cinemas, and ]'s depiction of Bond affected Fleming's interpretation of the character, henceforth giving Bond both a dry sense of humour and Scottish antecedents that were not present in the previous stories.{{sfn|Macintyre|2008|p=205}} In a fictional obituary, purportedly published in '']'', Bond's parents were given as Andrew Bond, from the village of ], ], and Monique Delacroix, from the canton of ], Switzerland.{{sfn|Chancellor|2005|p=59}} Fleming did not provide Bond's date of birth, but ]'s fictional biography of Bond, '']'', gives Bond a birth date on 11 November 1920,{{sfn|Pearson|2008|p=21}} while a study by John Griswold puts the date at 11 November 1921.{{sfn|Griswold|2006|p=27}} | |||

| The cinematic Bond had the character quirk of being a "know-it-all." In '']'', he calculates in his head how many trucks it takes to transport all the gold in ], and how long the gold would be ] after ] bomb had exploded. Bond's "]" became a running joke during Moore's era. It was virtually eliminated during Dalton's tenure as 007. | |||

| === Novels and related works === | |||

| ===The franchise=== | |||

| {{Main|List of James Bond novels and short stories}} | |||

| ]'' is the novel credited with sparking the James Bond craze when it was listed as one of ]'s favourite books.]] | |||

| The Bond franchise is currently the second all-time highest grossing film franchise in history, after '']''{{ref|filmfranchise}}, and one of the longest running film series in history, spanning 20 ], 2 ], 1 TV episode based on ''Casino Royale'', and a cartoon television series spinoff. A new movie, ''Casino Royale'', is currently in pre-production with an expected release in 2006. | |||

| ==== Ian Fleming novels ==== | |||

| The James Bond novels and movies have ranged from realistic spy drama to ]. The original books by Fleming are usually dark – lacking ] or gadgets. Instead, they established the formula of unique villains, outlandish plots, and voluptuous women who tend to fall in love with Bond at first sight (the feeling often being mutual.) The films expanded on Fleming's books, adding gadgets from ], and death-defying stunts, and often abandoning the original plotlines for more outlandish and cinema-friendly adventures. Cinematic Bond adventures were initially influenced by earlier spy thrillers such as '']'', '']'', and '']'', but later entries became formulaic dramas where Bond saves the world from ] madmen. Inevitably, a villain tries to kill Bond with a ] during which the villain reveals vital information; Bond later escapes and uses the information to thwart the ] plot. In many cases, the villain then dies at Bond's hands, although early Bond films often ended with the villain either escaping or being killed by someone else. | |||

| ], in Jamaica, where Fleming wrote all the Bond novels{{sfn|Macintyre|2008|p=208}}]] | |||

| Whilst serving in the Naval Intelligence Division, Fleming had planned to become an author<ref name="Lycett (DNB)">{{cite ODNB|last= Lycett |first=Andrew|title=Fleming, Ian Lancaster (1908–1964) (subscription needed)|url=http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/33168|access-date=7 September 2011|author-link=Andrew Lycett|doi=10.1093/ref:odnb/33168|year=2004}}</ref> and had told a friend, "I am going to write the spy story to end all spy stories."<ref name="Macintyre (2008b)">{{cite news|last=Macintyre|first=Ben|title= Bond – the real Bond|newspaper=]|page=36|date=5 April 2008|ref={{harvid|Macintyre (2008b)}}}}</ref> On 17 February 1952, he began writing his first James Bond novel, ''Casino Royale'', at his ] in Jamaica,{{sfn|Chancellor|2005|p=4}} where he wrote all his Bond novels during the months of January and February each year.{{sfn|Chancellor|2005|p=5}} He started the story shortly before his wedding to his pregnant girlfriend, Ann Charteris, in order to distract himself from his forthcoming nuptials.{{sfn|Bennett|Woollacott|2003|p=1|loc=ch 1}} | |||

| The first actor to play Bond was American ], in the ] ] television production of ''Casino Royale'' in which the character became a U.S. agent named "Jimmy Bond." In ], ] provided the voice of Bond in a ]n ] adaptation of '']''. | |||

| After completing the manuscript for ''Casino Royale'', Fleming showed it to his friend (and later editor) ] to read. Plomer liked it and submitted it to the publishers, ], who did not like it as much. Cape finally published it in 1953 on the recommendation of Fleming's older brother ], an established travel writer.{{sfn|Chancellor|2005|p=5}} Between 1953 and 1966, two years after his death, twelve novels and two short-story collections were published, with the last two books—'']'' and '']''—published posthumously.{{sfn|Black|2005|p=75}} All the books were published in the UK through Jonathan Cape. | |||

| ] and ] started the official cinematic run of Bond in ], with '']'' starring Sean Connery. Their production company, EON Productions (supposedly an acronym for 'Everything Or Nothing', which was their motto), set up a semi-regular schedule of releases (initially annually, then usually once every two years) until 1989. Every Bond film has been a box office success to a lesser or greater degree. They continue to earn substantial profits after their theatrical run via ], ], and television broadcasts. In the UK, Bond holds three of the top five top spots of ]. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| By the ], many critics had grown tired of the films, commenting that the perennial ] and glamorous locales had become outdated, and that Bond's smooth, unruffled exterior didn't mesh with competing movies like '']''. The hard-edge of Timothy Dalton in the Bond movies of the late 80s met a mixed response from moviegoers; some welcomed the earthier style reminiscent of Fleming's character, while others missed the light-hearted approach which characterised the Roger Moore era. While ''Licence to Kill'' (]) was financially successful, it did not prove as popular as previous Bond films. ''Licence to Kill'''s relative failure is usually blamed on a poor promotional campaign in the United States, Dalton's darker portrayal of Bond, and it being the first Bond film to be rated ] in the ] and "15" in the ]. A new Bond film was announced for release in ]; however, legal wrangling over ownership of the character led to a protracted delay that would keep Bond off movie screens for the next six years during which time, Dalton's career had moved on. | |||

| |- style="vertical-align:top; width:225px;" | |||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| * 1953 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Casino Royale |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=56 |work=The Books |publisher=] |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120317100519/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=56 |archive-date=17 March 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1954 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Live and Let Die |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=57 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120317100551/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=57 |archive-date=17 March 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1955 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Moonraker |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=58 |work=The Books |publisher= Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110916133924/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=58 |archive-date= 16 September 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1956 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Diamonds are Forever |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=59 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120317100356/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=59 |archive-date=17 March 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1957 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=From Russia, with Love |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=60 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120401031119/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=60 |archive-date=1 April 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1958 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Dr. No |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=61 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227054058/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=61 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1959 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Goldfinger |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=62 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227055724/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=62 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| * 1960 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=For Your Eyes Only |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=63 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227055343/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=63 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> (short stories) | |||

| * 1961 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Thunderball |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=64 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227055120/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=64 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1962 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=The Spy Who Loved Me |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=65 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227054837/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=65 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1963 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=On Her Majesty's Secret Service |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=174 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227052813/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=174 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1964 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=You Only Live Twice |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=67 |work= The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120303111111/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=67 |archive-date=3 March 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1965 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=The Man with the Golden Gun |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=68 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227060115/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=68 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1966 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Octopussy and The Living Daylights |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=69 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=31 October 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110907004806/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=69 |archive-date=7 September 2011 }}</ref> (short stories; "The Property of a Lady" added to subsequent editions) | |||

| |} | |||

| ==== Post-Fleming novels ==== | |||

| The ] saw a revival and renewal of the series beginning with '']'' in ]. Pierce Brosnan filled Bond’s shoes with an elegant mix of Sean Connery cool and Roger Moore ]. | |||

| After Fleming's death, a continuation novel, '']'', was written by ] (as ]) and published in 1968.<ref>{{cite web|title=Colonel Sun |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=81 |work=The Books |publisher= Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=2 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227071453/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=81 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> Amis had already written a literary study of Fleming's Bond novels in his 1965 work '']''.{{sfn|Benson|1988|p=32}} Although ]s of two of the ] Bond films appeared in print, '']'' and '']'', both written by screenwriter ],<ref name="IFP, Novelizations">{{cite web|title=Film Novelizations |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=163 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=2 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110918184837/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=163 |archive-date=18 September 2011 }}</ref> the series of novels did not continue until the 1980s. In 1981, the thriller writer ] picked up the series with '']''.{{sfn|Simpson|2002|p=58}} Gardner went on to write sixteen Bond books in total; two of the books he wrote were novelisations of Eon Productions films of the same name: '']'' and '']''. Gardner moved the Bond series into the 1980s, although he retained the ages of the characters as they were when Fleming had left them.{{sfn|Benson|1988|p=149}} In 1996, Gardner retired from writing James Bond books due to ill health.<ref>{{cite news|last=Ripley|first=Mike|url=https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/nov/02/guardianobituaries.booksobituaries|title=Obituary: John Gardner: Prolific thriller writer behind the revival of James Bond and Professor Moriarty|access-date=14 November 2011|newspaper=]|date=2 November 2007|page=41|archive-date=15 April 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230415133341/https://www.theguardian.com/news/2007/nov/02/guardianobituaries.booksobituaries|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| James Bond has long been a household name and remains a huge influence within the cinematic spy film genre. The '']'' series and other parodies such as '']'' (]), and ''Casino Royale'' (]) are testaments to Bond's prominence in popular culture (see: ]). 1960s TV imitations of James Bond such as '']'', '']'', '']'', and '']'' went on to became popular successes in their own right. (Fleming contributed to the creation of ''U.N.C.L.E.''; the show's lead character, "]," was named after a character in Fleming's novel ''Goldfinger'' and Fleming also suggested the character name April Dancer, which was later used in the ] series '']''.) | |||

| |- style="vertical-align:top; width:225px;" | |||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| ==Character's biography== | |||

| * 1981 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Licence Renewed |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=141 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092749/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=141 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| {{spoiler}} | |||

| * 1982 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=For Special Services |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=211 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092955/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=211 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| James Bond is the son of a ] father, Andrew Bond, and a ] mother, Monique Delacroix, both of whom died in a mountain ] accident in the ], when Bond was 11 years old. James went to live with his Aunt, Miss Charmian Bond, in ]. Bond's family ], which was later adopted by James Bond during "Operation Corona" in the novel '']'' is ''Orbis non sufficit'' (] for "The world is not enough.") | |||

| * 1983 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Ice Breaker |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=142 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092651/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=142 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1984 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Role Of Honour |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=143 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092007/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=143 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| An interesting, if wholly non-], conjecture about the Bond lineage can be found in ] comic book series, '']'', set in ]. In it, the portly, sinister, and secretive MI6 agent placed in charge of the League is named ]. His official title as director of the top-secret team is ], an obvious reference to the Bond mythos. Although Moore makes no overt connection between Bond and Campion, the saturation of literary reference in the comics has led fans to propose that Campion is meant to be an ancestor of the modern secret agent. His first name, Campion, is believed to be a reference to fictional detective ]. | |||

| * 1986 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Nobody Lives Forever |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=144 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092102/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=144 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1987 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=No Deals Mr Bond |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=145 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092157/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=145 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| With the exception of the '']'' series of novels by ] launched in 2005, Bond for the most part is an ] character in both films and literature. He is roughly in his late thirties (the age of 37 can be deduced from ''Moonraker''). According to John Pearson's '']'', Bond was born on ], ]; no Fleming novel supports this date. According to an obituary of James Bond in the novel '']'', Bond left school when he was 17 years old and joined the ] in ]. If Bond was 17 in 1941, then he was born in ]. Fleming also establishes that Bond bought his first car, a ] (driven in several early novels and the second Bond film, '']''), in ], contradicting both birthdates—he would have been too young to buy a car had he been born in either 1920 or 1924, though he might have purchased the vehicle at a later date. Many Fleming biographers agree that Fleming never really intended to write as many James Bond adventures as he did and to keep writing the novels he had to "tinker with Bond's early life" and change dates to ensure Bond was the appropriate age for the service, particularly due to a statement in ''Moonraker'' that 007 faced mandatory ] from the 00 Section at age 45. The issue of the car is one such example. ] recognised this issue for their new series of novels featuring Bond as a teenager in the ] and along with its author, Charlie Higson, defined Bond being born in the year 1920 (no specific date has thus far been declared). | |||

| * 1988 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Scorpius |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=145 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092157/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=145 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1989 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Win, Lose Or Die |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=147 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092427/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=147 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| The continuation Bond novels by John Gardner and Raymond Benson published between ] and ] depict Bond as being active in the present day (with Gardner in particular tying Bond to then-current events such as the ].) Gardner depicts Bond as being in early middle age at the time of '']'', making it likely that his version of the character must have been born sometime after that of Fleming's Bond. Benson's Bond appears to be patterned after Pierce Brosnan's film portrayal, suggesting that he was born in the early ]. | |||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| * 1989 ''Licence to Kill''<ref name="IFP, Novelizations" /> (novelisation) | |||

| It is also debated where James Bond was born. According to Pearson, Bond was born near ], ]; however, Charlie Higson, in his novel ''SilverFin'' claims Bond was born in ]. | |||

| * 1990 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Brokenclaw |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=148 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092455/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=148 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1991 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=The Man From Barbarossa |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=149 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227092554/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=149 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| Bond briefly attended ] starting at the age of 12, but was expelled after two halves when some "alleged" troubles with one of his maids came to light. In Fleming's ] "]," Bond admits to losing his ] on his first visit to ] at the age of 16. Gardner's novel '']'' also references this moment in Bond's life. After Eton, Bond attended and continued his education in the prestigious ] in ], ]. In "]", Fleming writes that Bond briefly attended the ]. With the exception of Fettes, Bond's attendance at these schools parallels Fleming's own life, as he attended these same schools. | |||

| * 1992 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Death is Forever |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=150 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111008202437/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=150 |archive-date=8 October 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1993 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Never Send Flowers |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=151 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093052/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=151 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| In ], Bond lied about his age in order to enter the ]'s Volunteer Reserve during ], from which he emerged with the rank of ] before joining ]. During his tenure writing James Bond novels in the ] and ], Gardner promoted Bond to ], but he was subsequently demoted back to Commander in Benson's novels without explanation. | |||

| * 1994 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Seafire |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=152 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093233/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=152 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| * 1995 ''GoldenEye''<ref name="IFP, Novelizations" /> (novelisation) | |||

| In both the literary and cinematic versions of '']'', James Bond marries, but his bride, ] (Tracy), is killed on their wedding day by his archenemy, ]; the event resonates in both versions of the character for many years thereafter. In the novels, Bond gets ] in the following novel, ''You Only Live Twice'', when he by chance comes across Blofeld in ], whilst the cinematic Bond takes on Blofeld in '']'' with mixed results. | |||

| * 1996 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Cold |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=153 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093337/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=153 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| Bond had one child, by Kissy Suzuki in ''You Only Live Twice'', although he did not know of the boy's existence until sometime later. Exactly when he learned this is not known; however he is aware of his son, James Suzuki, by the time of Raymond Benson's short story "]." | |||

| A second (non-canonical) son is suggested in the ] series ]. Clive Reston, a supporting character in the series, resembles Bond in many respects and is an MI-6 agent himself. While it is never stated explicitly, dialogue strongly hints that Reston is Bond's son and the grand-nephew of ]. In his fictional biographies, author ] suggests that Bond belongs in the ] tree along with ], ], and many other fictional heroes. Followers of Farmer's speculations have greatly elaborated on Bond's family. | |||

| In the novels (notably ''From Russia, With Love''), Bond's physical description has generally been consistent: a three-inch, vertical scar on his left cheek (absent from the cinematic version); blue-grey eyes; a "cruel" mouth; short, dark hair, a comma of which falls on his forehead (greying at the temples in Gardner's novels); and (after '']'') the faint scar of the ] ] letter "Ш" (SH) on the back of one of his hands (carved by a ] agent). | |||

| The literary and cinematic secret agent's attitude towards his job is similar. Although licensed to kill, Bond dislikes taking life—resorting to flippant jokes and off-hand remarks as after-the-fact relief, often misinterpreted as cold-bloodedness. Pearson's biography (disputed canonically) suggests Bond first killed as a teenager. The novel ''Goldfinger'' begins with Bond being haunted by memories of the small-time, ] gunman he had killed with his bare hands days earlier. In the films, there is a subtle hint in '']'' that he might be haunted so, and, in '']'', he admits that cold-blooded killing is a filthy business. Nonetheless, James Bond kills when needed, and on film commits acts that might be considered ] in other circumstances (in '']'', shooting Professor Dent in the back; killing the unarmed ] in ''The World Is Not Enough''). The literary James Bond was reserved in his licensed killing; there are Fleming works in which Bond does not kill anyone. | |||

| The cinematic Bond is famous for ordering his vodka martinis "shaken, not stirred." The literary Bond prefers ], but also drinks ] martinis, and in ''Casino Royale'' orders a martini that includes both types of liquor. Bond initially calls it "The Vesper" martini, after his lover in that book, ]. Throughout the novels, 007 orders his martinis with a slice of lemon peel (Fleming felt that ]s were added by bartenders to decrease the amount of liquor in the drink), although this only occurs on film in ''Dr. No''. In real life, martini bars often dub a martini made "shaken, not stirred" as a "Martini James Bond." (See ] for a detailed description of how a shaken martini differs from a stirred one). In the novels, most of the drinks that Bond has—beyond ''Casino Royale''—aren't martinis at all. | |||

| In 1996, the American author ] became the author of the Bond novels. Benson had previously been the author of '']'', first published in 1984.<ref>{{cite web|title=Books – At a Glance|url=http://www.raymondbenson.com/books/|work=RaymondBenson.com|access-date=3 November 2011|author=Raymond Benson|author-link=Raymond Benson|archive-date=27 November 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111127115953/http://www.raymondbenson.com/books/|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Age is the notable difference between the literary and the cinematic versions of James Bond. As noted above, per Fleming's novel ''Moonraker'', agent 007 faced mandatory retirement from active duty at age 45, while many of the films feature a considerably older hero. Assuming the correctness of either the 1920 or 1924 birthdates, Fleming's Bond would have retired between ] (coincidentally the year Fleming died) and ] (after '']'''s ] publication). Pearson's biography suggests Bond continued working for MI6 as a special agent, beyond retirement age, and continued serving as agent 007 into the ]. John Gardner's version of James Bond is a man born after Fleming's version, since he remains an active agent in the ] and the ], while Benson's hero serves as 007 in the 1990s and 2000s, suggesting a later birthdate than Gardner's version. <!--This issue has already been dealt with earlier in the article. This reference is merely repeating itself and taking up space--> | |||

| By the time he moved on to other, non-Bond related projects in 2002, Benson had written six Bond novels, three novelisations and three short stories.<ref>{{cite web|title=Raymond Benson |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=176 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227071253/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=176 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| The cinematic James Bond (introduced in 1962) already had a history with MI6. In ''Dr. No'', when reluctantly re-equipped with a 7.65 mm ] pistol replacing his under-powered ] calibre ] automatic pistol, agent 007 protests, telling ] that he has used the weapon for 10 years, suggesting he has been a secret agent for at least that long. Since ''Dr. No'' in both the literary and cinematic versions, Bond has used a Walther PPK in almost every adventure. In the film ''Tomorrow Never Dies'', Bond updates his gun to the latest model of the ]. In the novels, Gardner replaced the PPK (eventually) with an ]. | |||

| The cinematic Bond is a graduate with a ] in ] from ], as stated in '']''. Bond can also be seen in other films speaking a variety of different languages, most notably ], which he uses in ''The World Is Not Enough''. | |||

| Although never stated outright, in his books, Fleming drops hints that Bond was smuggled into ] during its anti-] ] in ]. A popular ] holds that a British secret agent was sent to Hungary to attempt to train the rebels, although they eventually lost. Using his literary licence, Fleming implies that Bond was this agent. | |||

| ==Books== | |||

| ===By ]=== | |||

| ].]] | |||

| In January 1952, Ian Fleming began work on his first James Bond novel. At the time, Fleming was the Foreign Manager for ], an organisation owned by the '']''. Upon accepting the job, Fleming asked that he be allowed two months vacation per year. Every year thereafter until his death in 1964, Fleming would retreat for the first two months of the year to his ]n house, "Goldeneye", to write a James Bond novel. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| |- style="vertical-align: |

|- style="vertical-align:top; width:225px;" | ||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| | | |||

| * 1997 "]"{{sfn|Simpson|2002|p=62}} (short story) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 1997 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Zero Minus Ten |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=210 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093949/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=210 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 1997 '']''<ref name="IFP, Novelizations" /> (novelisation) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 1998 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=The Facts Of Death |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=134 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093647/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=134 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 1999 "]"{{sfn|Simpson|2002|p=63}} (short story) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 1999 "]"{{sfn|Simpson|2002|p=64}} (short story) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 1999 '']''<ref name="IFP, Novelizations" /> (novelisation) | |||

| | | |||

| * 1999 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=High Time To Kill |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=135 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093753/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=135 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2000 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Doubleshot |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=136 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093445/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=136 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2001 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Never Dream Of Dying |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=137 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093544/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=137 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2002 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=The Man With The Red Tattoo |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=138 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227093615/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=138 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2002 '']''<ref name="IFP, Novelizations" /> (novelisation) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| After a gap of six years, ] was commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications to write a new Bond novel, which was released on 28 May 2008, the 100th anniversary of Fleming's birth.<ref>{{cite news|title=Faulks pens new James Bond novel|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/6289186.stm|access-date=3 November 2011|newspaper=]|date=11 July 2007|archive-date=12 February 2009|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090212225504/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/6289186.stm|url-status=live}}</ref> The book—titled '']''—was published in the UK by Penguin Books and by Doubleday in the US.<ref name="Faulks">{{cite web|title=Sebastian Faulks |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=177 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227071357/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=177 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> American writer ] was then commissioned by Ian Fleming Publications to produce ], which was published on 26 May 2011.<ref>{{cite news|title=James Bond book called Carte Blanche|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-12204547|access-date=3 November 2011|newspaper=BBC News|date=17 January 2011|archive-date=19 March 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120319150348/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-12204547|url-status=live}}</ref> The book turned Bond into a post-9/11 agent, independent of ] or MI6.<ref>{{cite web|title=Jeffery Deaver |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=268 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=3 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120415123737/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=268 |archive-date=15 April 2012 }}</ref> On 26 September 2013, '']'' by ], set in 1969, was published.<ref>{{cite web|title=Solo Published Today |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/solo-published-today/ |publisher=] |access-date=1 October 2013 |date=26 September 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131004234832/http://www.ianfleming.com/solo-published-today/ |archive-date= 4 October 2013 }}</ref> In October 2014, it was announced that ] was to write a ''Bond'' continuation novel.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/jamesbond/11133873/James-Bonds-secret-mission-to-save-Stirling-Moss.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/jamesbond/11133873/James-Bonds-secret-mission-to-save-Stirling-Moss.html |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |work=] |title=James Bond's secret mission: to save Stirling Moss |first=Anita |last=Singh |date=2 October 2014 |access-date=6 November 2015}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Set in the 1950s two weeks after the events of ''Goldfinger'', it contains material written, but previously unreleased, by Fleming. '']'' was released on 8 September 2015.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-32899911 |title=James Bond: Pussy Galore returns in new novel |work=BBC News |publisher=BBC |date=28 May 2015 |access-date=28 May 2015 |archive-date=13 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230513215956/https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-32899911 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |first=Alison |last=Flood |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/may/28/new-james-bond-novel-trigger-mortis-pussy-galore-anthony-horowitz |title=New James Bond novel Trigger Mortis resurrects Pussy Galore |newspaper=The Guardian |date=28 May 2015 |access-date=28 May 2015 |archive-date=8 June 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230608035412/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2015/may/28/new-james-bond-novel-trigger-mortis-pussy-galore-anthony-horowitz |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/celebritynews/11634404/Pussy-Galore-returns-for-new-James-Bond-novel-Trigger-Mortis.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/celebritynews/11634404/Pussy-Galore-returns-for-new-James-Bond-novel-Trigger-Mortis.html |archive-date=10 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |work=The Daily Telegraph |title=Pussy Galore returns for new James Bond novel ''Trigger Mortis'' |first=Hannah |last=Furness |date=28 May 2015 |access-date=6 November 2015}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Horowitz's second Bond novel, '']'', tells the origin story of Bond as a 00 agent prior to the events of ''Casino Royale''. The novel, also based on unpublished material from Fleming, was released on 31 May 2018.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/forever-and-a-day/ |title=Forever and a Day |work=IanFleming.com |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |date=8 February 2018 |access-date=16 February 2019 |archive-date=18 February 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190218042318/http://www.ianfleming.com/forever-and-a-day/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/12/books/james-bond-forever-and-a-day-anthony-horowitz.html |archive-url=https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220103/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/12/books/james-bond-forever-and-a-day-anthony-horowitz.html |archive-date=3 January 2022 |url-access=subscription |url-status=live |title=New James Bond Novel Is a Prequel to Fleming's First |work=] |date=12 February 2018 |access-date=16 February 2019}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Horowitz's third Bond novel, ''With a Mind to Kill'', was published on 26 May 2022.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.ianfleming.com/new-horowitz-bond-title-and-cover-revealed/ |title=New Horowitz Bond Title and Cover Revealed |work=IanFleming.com |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |date=16 December 2021 |access-date=16 December 2021 |archive-date=16 December 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211216190241/https://www.ianfleming.com/new-horowitz-bond-title-and-cover-revealed/ |url-status=live }}</ref> ] first adult Bond novel, ''On His Majesty's Secret Service'', was published on 4 May 2023 to celebrate the ] and support the ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://variety.com/2023/film/news/james-bond-king-charles-coronation-on-his-majestys-secret-service-1235569901/ |title=New James Bond Story 'On His Majesty's Secret Service' Commissioned to Celebrate King Charles' Coronation |first=Naman |last=Ramachandran |date=31 March 2023 |website=] |access-date=5 May 2023 |archive-date=5 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230505181215/https://variety.com/2023/film/news/james-bond-king-charles-coronation-on-his-majestys-secret-service-1235569901/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Between 1953 and 1966, twelve James Bond novels and two short story collections by Fleming were published, with one novel and one short story collection issued posthumously. To this day, it is still debated ] 1965's ''The Man with the Golden Gun'', as he died very soon after completing the book. His first anthology of short stories, ''For Your Eyes Only'', mostly consisted of converted screenplays for a ] television series based on the character. When the project fell through, Fleming turned them into short stories: (i) "]", (ii) "]", (iii) "]", plus two additional stories, "]" and "]", which were previously published. The second anthology, ''Octopussy and The Living Daylights'' (in many editions titled only ''Octopussy''), originally only contained two short stories, "]" and "]; a third story, "]" was added in the 1967 paperback edition, and a fourth, "]", was added in 2002. | |||

| ===Post-Fleming James Bond novels=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Following Fleming's death in 1964, ], publishers of the James Bond novels, planned a new book series, credited to the pseudonym "]" and written by a rotating series of authors. Ultimately, only one Markham novel saw print, 1968's '']'' by ]. Amis had previously written two books on the world of James Bond, the 1964 essay ''The James Bond Dossier'' and the tongue-in-cheek ] release ''The Book of Bond, or Every Man His Own 007'' (written under the pseudonym "Lt.-Col. William ("Bill") Tanner", a recurring character in the Bond novels. Amis had also been claimed for many years as the ] of '']'', although this has been debunked by numerous sources. See ].) | |||

| In ], Fleming biographer ] was commissioned by Glidrose to biograph the fictional character James Bond. Pearson wrote '']'' in the first person as if meeting the secret agent himself. The book was well-received by aficionados—readers and viewers, alike. Since the book has many discrepancies with Fleming's Bond (for example his birth year), the canonical status of ''James Bond: The Authorised Biography of 007'' is debated among fans—some consider it ], though at least one publisher issued it as an official novel along with the rest of Fleming's series. Glidrose reportedly considered a new series of novels written by Pearson, but this did not come to pass. Prior to writing this, Pearson had written an early biography of Ian Fleming, '']''. | |||

| In ], the film '']'' was released and was subsequently novelised and published by Glidrose due to the radical difference between the script and Fleming's novel of the same name. This would happen again with ]'s '']''. Both novelisations were written by ] ] and were the first official novelisations, although technically, Fleming's ''Thunderball'' was a novelisation having been based on scripts by himself, ], and ] (although it predated the movie), and the ''For Your Eyes Only'' collection was also, for the most part, based upon unproduced scripts. | |||

| In the 1980s, the series was finally revived with new novels by John Gardner; between ] and ], he wrote fourteen James Bond novels and two screenplay novelisations, surpassing Fleming's original output. The biggest change in Gardner's series was updating 007's world to the 1980s; however, it would keep the characters the same age as they were in Fleming's novels. Generally Gardner's series is considered a success although their canonical status is disputed. | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| |- style="vertical-align: |

|- style="vertical-align:top; width:225px;" | ||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| | | |||

| * 2008 '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2011 '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * |

* 2013 '']'' | ||

| * |

* 2015 '']'' | ||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2018 '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2022 ''With a Mind to Kill'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2023 ''On His Majesty's Secret Service'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| | | |||

| *] '']'' (]) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' (novelisation) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ==== Young Bond ==== | |||

| In 1996, Gardner retired from writing James Bond books due to ill health, and American Raymond Benson quickly replaced him. As a James Bond novelist, Benson was initially controversial for being American, and for ignoring much of the continuity established by Gardner. Benson had previously written '']'', a book dedicated to Ian Fleming, the official novels, and the films. The book was initially released in ] and later updated in ]. Benson also contributed to the creation of several modules in the popular ''James Bond 007'' ] in the 1980s. Benson wrote six James Bond novels, three novelisations, and three short stories. | |||

| {{Main|Young Bond}} | |||

| The '']'' series of novels was started by ]<ref>{{cite news|last=Smith|first=Neil|title=The name's Bond – Junior Bond|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/4293323.stm|access-date=1 November 2011|newspaper=BBC News|date=3 March 2005|archive-date=30 May 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080530161026/http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/4293323.stm|url-status=live}}</ref> and, between 2005 and 2009, five novels and one short story were published.<ref>{{cite web|title=Charlie Higson|url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Search/QuickSearchProc/1,,Author_1000066902,00.html|work=Puffin Books – Authors|publisher=]|access-date=1 November 2011|archive-date=9 March 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110309024638/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Search/QuickSearchProc/1,,Author_1000066902,00.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> The first Young Bond novel, '']'' was also adapted and released as a graphic novel on 2 October 2008 by Puffin Books.<ref>{{cite web|title=SilverFin: The Graphic Novel|url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322537,00.html?%2FSilverFin%3A_The_Graphic_Novel_Charlie_Higson|work=Puffin Books|publisher=Penguin Books|access-date=1 November 2011|archive-date=1 November 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101144944/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322537,00.html?%2FSilverFin%3A_The_Graphic_Novel_Charlie_Higson|url-status=dead}}</ref> In October 2013 Ian Fleming Publications announced that ] would continue the series, with the first edition scheduled to be released in Autumn 2014.<ref>{{cite web|title=New Young Bond Series in 2014 |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/new-young-bond-series-in-2014/ |publisher=] |access-date=11 October 2013 |date=9 October 2013 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131014031316/http://www.ianfleming.com/new-young-bond-series-in-2014/ |archive-date=14 October 2013 }}</ref> | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |- style="vertical-align: top;" | ||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| | | |||

| * 2005 ''SilverFin''<ref>{{cite web|title=Young Bond: SilverFin |url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141318592,00.html?/Young_Bond:_SilverFin_Charlie_Higson |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121030080945/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141318592,00.html?/Young_Bond:_SilverFin_Charlie_Higson |url-status=dead |archive-date=30 October 2012 |work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson |publisher=Penguin Books |access-date=2 November 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| *] ''"]"'' (short story) | |||

| * 2006 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Young Bond: Blood Fever |url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141318608,00.html?/Young_Bond:_Blood_Fever_Charlie_Higson |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121030080945/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141318608,00.html?/Young_Bond:_Blood_Fever_Charlie_Higson |archive-date=30 October 2012 |url-status=dead|work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson |publisher=Penguin Books |access-date=2 November 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2007 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Young Bond: Double or Die |url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322032,00.html?/Young_Bond:_Double_or_Die_Charlie_Higson |work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson |publisher=Penguin Books |access-date=2 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101150520/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0%2C%2C9780141322032%2C00.html?%2FYoung_Bond%3A_Double_or_Die_Charlie_Higson |archive-date= 1 November 2012 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' (novelisation) | |||

| * 2007 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Young Bond: Hurricane Gold |url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322049,00.html?/Young_Bond:_Hurricane_Gold_Charlie_Higson |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121030080945/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322049,00.html?/Young_Bond:_Hurricane_Gold_Charlie_Higson |url-status=dead |archive-date=30 October 2012 |work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson |publisher=Penguin Books |access-date=2 November 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| * 2008 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Young Bond: By Royal Command |url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141384511,00.html?/Young_Bond:_By_Royal__Command_Charlie_Higson |work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson |publisher=Penguin Books |access-date=2 November 2011 }}{{dead link|date=July 2024|bot=medic}}{{cbignore|bot=medic}}</ref> & ''SilverFin''<ref>{{cite web|title=SilverFin: The (Graphic Novel)|url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322537,00.html?%2FSilverFin%3A_The_Graphic_Novel_Charlie_Higson|work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson|publisher=Penguin Books|access-date=2 November 2011|archive-date=1 November 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101144944/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141322537,00.html?%2FSilverFin%3A_The_Graphic_Novel_Charlie_Higson|url-status=dead}}</ref> (graphic novel) | |||

| *] ''"]"'' (short story) | |||

| * 2009 "]"<ref>{{cite web|title=Danger Society: The Young Bond Dossier|url=http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141327709,00.html?%2FDanger_Society%3A_The_Young_Bond_Dossier_Charlie_Higson|work=Puffin Books: Charlie Higson|publisher=Penguin Books|access-date=2 November 2011|archive-date=1 November 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121101144906/http://www.puffin.co.uk/nf/Book/BookDisplay/0,,9780141327709,00.html?%2FDanger_Society%3A_The_Young_Bond_Dossier_Charlie_Higson|url-status=dead}}</ref> (short story) | |||

| *] ''"]"'' (short story) | |||

| | | |||

| *] '']'' (novelisation) | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' (novelisation) | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| ==== ''The Moneypenny Diaries'' ==== | |||

| Benson abruptly resigned as Bond novelist at the end of 2002, despite having previously announced plans to write a short story collection. Low sales figures for the books, and plans by Ian Fleming Publications to focus on reissuing Fleming's original novels for the 50th anniversary of the character, were among reasons speculated by fans as to why Benson departed. The year 2003 marked the first year since 1980 that a new James Bond novel had not been published. | |||

| {{Main|The Moneypenny Diaries}} | |||

| ''The Moneypenny Diaries'' are a trilogy of novels chronicling the life of ], ]'s personal secretary. The novels are written by ] under the ] Kate Westbrook, who is depicted as the book's "editor".<ref>{{cite news|title=Miss Moneypenny|newspaper=]|date=14 October 2005|page=10}}</ref> The first instalment of the trilogy, subtitled '']'', was released on 10 October 2005 in the UK.<ref>{{cite news|last=O'Connell|first=John|title=Books – Review – The Moneypenny Diaries – Kate Westbrook (ed) – John Murray GBP 12.99|newspaper=]|date=12 October 2005|page=47}}</ref> A second volume, subtitled '']'' was released on 2 November 2006 in the UK, published by ].<ref>{{cite news|last=Weinberg|first=Samantha|title=Licensed to thrill|newspaper=The Times|date=11 November 2006|author-link=Samantha Weinberg|page=29}}</ref> A third volume, subtitled '']'' was released on 1 May 2008.<ref>{{cite news|last=Saunders|first=Kate|title=The Moneypenny Diaries: Final Fling|newspaper=The Times|date=10 May 2008|page=13}}</ref> | |||

| On ], ], Ian Fleming Publications confirmed it is planning to publish a one-off adult Bond novel in ] to mark what would have been Ian Fleming's 100th birthday. This would feature the adult version of the character as opposed to the "Young Bond" character of the recent Charlie Higson books (see below). Although it has been suggested a "big name" author might take on the task, the publishers have yet to approach anyone about this project . | |||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| ===Young Bond=== | |||

| |- style="vertical-align:top; width:225px;" | |||

| {{main|Young Bond}} | |||

| | style="width:400pt;"| | |||

| In April 2004, Ian Fleming Publications (Glidrose) announced a new series of James Bond books. Instead of continuing from where Raymond Benson ended in 2002, the new series would feature James Bond as a thirteen-year-old boy attending ]. Written by ] ('']'') the series is expected to align with the adult Bond's back-story established by Fleming and Fleming only. Since the concept was announced the series has taken heavy criticism for being aimed at the "] audience" and has been seen by some as a desperate attempt to find a new audience for Bond. Regardless, the first novel became a bestseller in the United Kingdom and was released to good reviews. A second novel is due for release in January 2006. The series is currently planned out for five novels according to Charlie Higson. | |||

| * 2005 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Guardian Angel |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=228 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=2 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111008204241/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=228 |archive-date=8 October 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| * 2006 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Secret Servant |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=229 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=2 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111008204340/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=229 |archive-date=8 October 2011 }}</ref> | |||

| {|class="wikitable" | |||

| * 2008 '']''<ref>{{cite web|title=Final Fling |url=http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=230 |work=The Books |publisher=Ian Fleming Publications |access-date=2 November 2011 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101227051129/http://www.ianfleming.com/pages/content/index.asp?PageID=230 |archive-date=27 December 2010 }}</ref> | |||

| |- style="vertical-align: top;" | |||

| | | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| *] '']'' | |||

| |} | |} | ||

| == Adaptations == | |||

| The ''Young Bond'' series is expected to be expanded to include ]s in 2006. It is currently unknown whether these will be adaptations of Higson's books or original adventures. | |||

| === Television === | |||

| In 1954, ] paid Ian Fleming $1,000 (${{formatnum:{{Inflation|US|1000|1954}}}} in {{Inflation-year|US}} dollars{{inflation-fn|US|df=y}}) to adapt his novel ] into a one-hour television adventure, ], as part of its '']'' series.{{sfn|Black|2005|p=14}} The episode aired live on 21 October 1954 and starred ] as "Card Sense" James Bond and ] as Le Chiffre.{{sfn|Benson|1988|p=11}} The novel was adapted for American audiences to show Bond as an American agent working for "Combined Intelligence", while the character ]—American in the novel—became British onscreen and was renamed "Clarence Leiter".{{sfn|Black|2005|p=101}} | |||

| In 1964 Roger Moore appeared as "James Bond" in an extended comedy sketch opposite ] in her ] TV series ''Mainly Millicent'', which also makes reference to "007". It was written by ]. Undiscovered for several years, it reappeared as an extra in the DVD and Blu-ray release of ''Live and Let Die''.<ref>{{cite web|title=''Mainly Millicent: Roger Moore's First Appearance as James Bond''|date=16 January 2015 |url=https://www.bondsuits.com/mainly-millicent-roger-moores-first-appearance-james-bond/|access-date=21 August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ===The Moneypenny Diaries=== | |||

| {{main|The Moneypenny Diaries}} | |||

| A new trilogy of novels "edited" by ] under the pseudonym ] entitled '']'' was released by ] publishers that centres on the character of ], ]'s personal secretary. The first instalment of the trilogy, subtitled ''Guardian Angel'', was released on ], ]. Weinberg is the first woman to write officially licensed Bond-related fiction. | |||

| In 1973, a ] documentary '']: The British Hero'' featured ] playing a number of such title characters (e.g. ] and ]). The documentary included James Bond in dramatised scenes from | |||

| The novels had originally been touted as the secret journal of a "real" Miss Moneypenny and that James Bond was a possible pseudonym for a genuine intelligence officer, an idea shared by John Pearson's earlier biography, ''James Bond: The Authorised Biography of 007''. John Murry admitted on ], ] that the books were a spoof after an investigation by ''The Sunday Times'' of London. Ian Fleming Publications, who had previously refused to comment as to whether the book was authorised, officially confirmed the book was and always had been a project by them on the day of the book's publication. | |||

| ]—notably featuring 007 being threatened with the novel's circular saw, rather than the film's laser beam—and '']''.<ref>{{citation |title=Radio Times|date=6–12 October 1973|pages=74–79}}</ref> | |||

| In 1991, a spin-off animated series, '']'', was produced with ] in the role of Bond's nephew, James Bond Jr.<ref>{{cite news|last=Svetkey|first=Benjamin|title=Sweet Baby James|url=https://ew.com/article/1992/05/29/looking-james-bond-jr-franchise/|access-date=4 November 2011|newspaper=]|date=29 May 1992|archive-date=20 October 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121020094034/http://www.ew.com/ew/article/0,,310606,00.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| A second volume has been tentatively scheduled for publication in October 2006. | |||

| In 2022, a ] based on the franchise, '']'', was released on ].<ref>{{cite news |last1=Rantala |first1=Hanna |title=New TV show ''007: Road To A Million'' brings Bond-like tasks to screens |url=https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/new-tv-show-007-road-million-brings-bond-like-tasks-screens-2023-11-02/ |work=] |date=8 November 2023 |language=en |access-date=16 January 2024 |archive-date=11 November 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20231111221436/https://www.reuters.com/lifestyle/new-tv-show-007-road-million-brings-bond-like-tasks-screens-2023-11-02/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ===Other Bond-related fiction=== | |||

| In ], Glidrose authorised publication of '']'' written by ] under the pseudonym R D Mascott. This book is for young-adult readers, and chronicles the adventures of 007's nephew (despite the inaccurate title). | |||

| === Radio === | |||

| An early ] animated television series, '']'', ran for 65 episodes and spawned a six-episode novelisation series written by ] under the ] John Vincent. (There appears to be no connection between this series and the 1967 book by Marshall). | |||

| In 1958, the novel ] was adapted for broadcast on ]n radio, with ] providing the voice of Bond.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://jamesbondradio.com/book-review-the-many-lives-of-james-bond/|title=Book Review: The Many Lives of James Bond|date=18 November 2019|website=James Bond Radio|language=en-GB|access-date=4 December 2019|archive-date=4 December 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191204002740/https://jamesbondradio.com/book-review-the-many-lives-of-james-bond/|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|title=The Many Lives of James Bond: How the Creators of 007 Have Decoded the Superspy|last=Edlitz|first=Mark|publisher=Lyons Press|year=2019|isbn=978-1493041565|page=148}}</ref> According to '']'', "listeners across the Union thrilled to Bob's cultured tones as he defeated evil master criminals in search of world domination".<ref>{{cite news|last=Roberts|first=Andrew|title=The Bond bunch|newspaper=]|date=8 November 2006|page=14}}</ref> | |||

| The ] have adapted five of the Fleming novels for broadcast: in 1990 ] was adapted into a 90-minute radio play for ] with ] playing James Bond. The production was repeated a number of times between 2008 and 2011.<ref>{{cite web|title=James Bond – You Only Live Twice|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00fbzkg|work=BBC Radio 4 Extra|publisher=BBC|access-date=21 October 2011|archive-date=4 January 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120104025517/http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00fbzkg|url-status=live}}</ref> On 24 May 2008 BBC Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation of ]. The actor ], who played Bond villain ] in the Eon Productions version of '']'', played Bond, while Dr. No was played by ].<ref>{{cite news|title=007 villain to play Bond on radio|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/7380086.stm|publisher=BBC|access-date=6 October 2011|date=2 May 2008|archive-date=16 March 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160316215211/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/7380086.stm|url-status=live}}</ref> Following its success, a second story was adapted and on 3 April 2010 ] broadcast ] with Stephens again playing Bond.<ref>{{cite web|author= Hemley, Matthew|date= 13 October 2009|url= http://www.thestage.co.uk/news/newsstory.php/25870/james-bond-to-return-to-radio-as-goldfinger|title= James Bond to return to radio as Goldfinger is adapted for BBC|publisher= The Stage Online|access-date= 19 March 2010|archive-date= 11 June 2011|archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20110611123625/http://www.thestage.co.uk/news/newsstory.php/25870/james-bond-to-return-to-radio-as-goldfinger|url-status= live}}</ref> ] was Goldfinger and Stephens' ''Die Another Day'' co-star ] played Pussy Galore. The play was adapted from Fleming's novel by Archie Scottney and was directed by ].<ref>{{cite web|title=Goldfinger|url=http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00rq1w3|work=Saturday Play|publisher=BBC|access-date=3 October 2011|archive-date=12 January 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120112033433/http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b00rq1w3|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] were often the villains in Fleming's ]-era novels in at least some form. In ], they hit back with a spy novel of their own called '']'' by ], in which a ] hero finally and forcefully defeats 007. | |||