| Revision as of 00:14, 28 August 2009 editIpatrol (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Rollbackers10,675 editsm Reverted edits by 76.68.30.180 to last revision by ClueBot (HG)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:09, 16 December 2024 edit undo205.155.229.11 (talk) →Origins and traditions | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Creative work in which pictures and text convey information}} | |||

| {{about||the entertainers known as "comics"|Comedian|the magazine format usually containing longer self-contained stories|Comic book}} | |||

| {{redirect|Comic}} | |||

| {{redirect|Comic art|the magazine|Comic Art{{!}}''Comic Art''}} | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| {{Use shortened footnotes|date=June 2022}} | |||

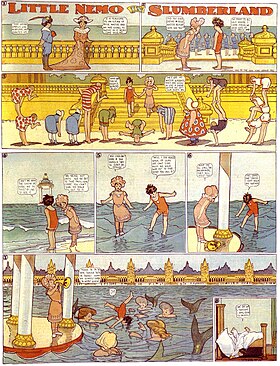

| ], August 19, 1906 strip]] | |||

| {{Comics navbar}} | |||

| {{not a typo|'''Comics''' are}} a ] used to express ideas with images, often combined with text or other visual information. It typically {{not a typo|takes}} the form of a sequence of ] of images. Textual devices such as ]s, ], and ] can indicate dialogue, narration, sound effects, or other information. There is no consensus among theorists and historians on a definition of '''comics'''; some emphasize the combination of images and text, some sequentiality or other image relations, and others historical aspects such as mass reproduction or the use of recurring characters. ] and other forms of ] are the most common means of image-making in comics. ] is a form that uses photographic images. Common forms include ]s, ] and ]s, and ]s. Since the late 20th century, bound volumes such as ]s, ], and {{transl|ja|]}} have become increasingly common, along with ]s as well as scientific/medical comics.<ref name="pmid37980636">{{cite journal |vauthors=Lombardo P, Nairz K, Boehm I |title=Why mild contrast medium-induced reactions are sometimes over-treated and moderate/severe reactions of internal organs are undertreated: a summary based on RadioComics |journal=Insights Imaging |volume=14 |issue=1 |pages=196 |year=2023 |pmid=37980636 |doi=10.1186/s13244-023-01554-y|doi-access=free |pmc=10657911 }}</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| '''Comics''' (from the ] {{Polytonic|''κωμικός''}}, ''kōmikos'' "of or pertaining to comedy" from ''κῶμος - kōmos'' "revel, ]",<ref>"comic adjective" The Oxford Dictionary of English (revised edition). Ed. Catherine Soanes and Angus Stevenson. Oxford University Press, 2005. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Surrey Libraries. 21 April 2008 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t140.e15358></ref> via the ] ''cōmicus'') is a ] ] in which ] are utilized in order to convey a sequential ]; the term, derived from massive early use to convey comic themes, came to be applied to all uses of this medium including those which are far from comic. It is the sequential nature of the pictures, and the predominance of pictures over words, that distinguish comics from ]s, though there is some overlap between the two media. Most comics combine words with images, often indicating speech in the form of ]s, but wordless comics, such as '']'', are not uncommon. Words other than dialogue, captions for example, usually expand upon the pictures, but sometimes act in ].<ref> Teresa Grainger (2004). "Art, Narrative and Childhood" ''Literacy'' 38 (1), 66–67. doi:10.1111/j.0034-0472.2004.03801011_2.x</ref> | |||

| The ] has followed different paths in different cultures. Scholars have posited a pre-history as far back as the ] cave paintings. By the mid-20th century, comics flourished, particularly in the ], western Europe (especially ]), and ]. The history of ] is often traced to ]'s cartoon strips of the 1830s, while ] and his ] also had a global impact from 1865 on,<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.thegermanprofessor.com/max-und-moritz/ | title=8 Things about Max und Moritz | date=30 March 2015 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.dw.com/en/max-and-moritz-how-germanys-naughtiest-boys-rose-to-global-fame/a-18808584 | title=Max and Moritz: How Germany's naughtiest boys rose to fame – DW – 10/27/2015 | website=] }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.outdooractive.com/en/story/harz/the-original-story-of-max-and-moritz/28754663/ | title=The original story of Max and Moritz }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.toonsmag.com/max-and-moritz/ | title=Max and Moritz: A Tale of Mischief and Influence - Toons Mag | date=8 October 2023 }}</ref> and became popular following the success in the 1930s of strips and books such as '']''. ] emerged as a ] in the early 20th century with the advent of newspaper comic strips; magazine-style ] followed in the 1930s, the ] genre became prominent after ] appeared in 1938. ] (''{{transl|ja|]}}'') propose origins as early as the 12th century. Japanese comics are generally held separate from the evolution of Euro-American comics, and Western comic art probably originated in 17th-century Italy.<ref></ref> Modern Japanese comic strips emerged in the early 20th century, and the output of comic magazines and books rapidly expanded in the post-World War II era (1945)– with the popularity of cartoonists such as ]. {{not a typo|Comics has}} had a ] reputation for much of their history, but towards the end of the 20th century, they began to find greater acceptance with the public and academics. | |||

| Early precursors of comics as they are known today include ] and the work of ]. By 19th century, the medium as we know it today, began to take form among European and American artists. Comics as a real mass medium started to emerge in the ] in the early 20th century, with the ] ], where its form began to be standardized (image-driven, speech balloons etc). The combination of words and pictures proved popular, and quickly spread throughout the world. Comic strips were soon gathered into cheap booklets, ]s, and original comic books soon followed. Today, comics are found in newspapers, magazines, comic books, graphic novels, and on the web. | |||

| The English term ''comics'' is used as a ] when it refers to the medium itself (e.g. "''Comics is'' a visual art form."), but becomes plural when referring to works collectively (e.g. "''Comics are'' popular reading material.").{{TOC limit|3}} | |||

| Although historically the form dealt with ] subject matter, its scope has expanded to encompass the full range of literary ]s. Also see: ] and ]. In the anglo-Saxon world, comics are still typically seen as a ]<ref>{{cite book | author=Dowd, Douglas Bevan | coauthors=Hignite, Todd | title=Strips, Toons, and Bluesies: Essays in Comics and Culture | publisher=Princeton Architectural Press | year=2006 | isbn=1568986211}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | author=Varnedoe, Kirk | coauthors=Gopnik, Adam | title=Modern Art and Popular Culture: Readings in High & Low | year=1990 | publisher=Abrams in association with the Museum of Modern Art | isbn=0870703560}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | author=Bollinger, Tim | editor=''Nga Pakiwaituhi o Aotearoa: New Zealand Comics'', ] (ed.) | year=2000 | publisher=Hicksville Press | title=Comics in the Antipodes: a low art in a low place | isbn=0-473-06708-0}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | author=Gold, Glen David | editor=''Masters of American Comics'', ], ] & ] (ed.) | title=Jack Kirby | pages=262 | publisher=Yale University Press | year=2005 | isbn=030011317X}}</ref>,<ref>{{cite book | author=Fielder, Leslie | editor=''Arguing Comics: Literary Masters on a Popular Medium'', ] & ] (ed.)| title=The Middle Against Both Ends | origyear=1955 | year=2004 | publisher=Univ. Press of Mississippi | pages=132 | isbn=1578066875}}</ref><ref>{{cite book | author=Groensteen, Thierry | title=Why are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimization? | editor=''Comics & Culture: Analytical and Theoretical Approaches to Comics'', Anne Magnussen & Hans-Christian Christiansen (ed.)| publisher=Museum Tusculanum Press | year=2000 | isbn=8772895802 }}</ref> although there are a few exceptions, such as '']''<ref name="Gilbert Seldes 1924">Gilbert Seldes, ''The 7 Lively Arts'', Harper, 1924, ASIN B000M1MMBC</ref> and '']''. However, such an elitist "low art/high art" distinction doesn't exist in the ] (and, to some extent, continental Europe), where the ] medium as a whole is commonly accepted as "the Ninth Art", is usually dedicated a non-negligible space in bookshops and libraries, and is regularly celebrated in international events such as the ]. | |||

| The comics may be further adapted to animations (anime), dramas, TV shows, movies. | |||

| In the late 20th and early 21st century there has been a movement to rehabilitate the medium. Critical discussions of the form appeared as early as the 1920s,<ref name="Gilbert Seldes 1924"/><ref>Martin Sheridan, ''Comics and their Creators'', Ralph T. Hale and Company, 1942, ASIN B000Q8QGC2</ref> but serious studies were rare until the late 20th century.<ref>Dez Skinn, ''Comic Art Now'', Collins Design, 2008, ISBN 978-0061447396.</ref> | |||

| ==Origins and traditions== | |||

| Although practitioners can eschew any formal constraints, they often use particular forms and conventions to convey narration and speech, or to evoke emotional or sensuous responses. Devices such as ] and boxes are used to indicate dialogue and impart establishing information, while ], ], ] and ] can help indicate the flow of the story. Comics use of ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] elements of ] help build a ] of meanings.<ref>Scott McCloud, ''Understanding Comics'', Harper, 1994, ISBN 978-0060976255</ref> Different conventions were developed around the globe, from the ] of Japan to the ] of China and the ] of Korea, the ] of the United States, and the larger hardcover ]s in Europe. | |||

| {{main|History of comics|List of comics by country}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| ===Early narratives in art=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ]'s "]" different scenes of the Biblical story are shown in the same painting: on the front, God is admonishing the couple for their sin; in the background to the right are shown the earlier scenes of Eve's creation from Adam's rib and of their being tempted to eat the forbidden fruit; on the left is the later scene of their expulsion from Paradise.]] | |||

| Comics as an art form established itself in the late 19th and early 20th century, alongside the similar forms of ] and ]. The three forms share certain conventions, most noticeably the mixing of words and pictures, and all three owe parts of their conventions to the technological leaps made through the ]. Although the comics form was established and popularized in the pages of ] and ] in the late 1890s, narrative illustration has existed for many centuries. | |||

| <gallery caption="Examples of early comics" mode="packed" heights="180"> | |||

| ]'s ], dedicated in 113 AD, is an early surviving examples of a narrative told through the use of sequential pictures, while ], ] ], medieval tapestries such as the ] and illustrated ] also demonstrate the use of sequential images and words combined to convey a narrative. In medieval paintings, many sequential scenes of the same story (usually a Biblical one) are simultaneously shown in the same painting (see illustration on the left). | |||

| Manga Hokusai.jpg|'']''<br />], early 19th century<!-- have to find the date for this example --> | |||

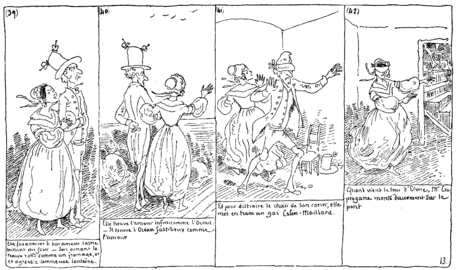

| Toepffer Cryptogame 13.png|{{lang|fr|Histoire de Monsieur Cryptogame}}<br />], 1830 | |||

| Max_und_Moritz_tinted_21.png|]''<br />], 1865 | |||

| AllySloper.jpg|] in ''Some of the Mysteries of Loan and Discount''<br />], 1867 | |||

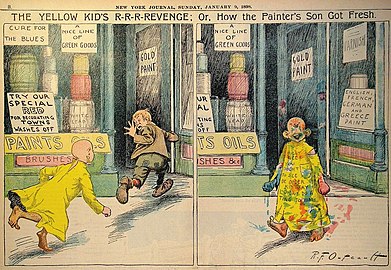

| Yellow Kid 1898-01-09.jpg|'']''<br />], 1898 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| The European, American, and Japanese comics traditions have followed different paths.{{sfn|Couch|2000}} Europeans have seen their tradition as beginning with the Swiss ] from as early as 1469 and Americans have seen the origin of theirs in ]'s 1890s newspaper strip '']'', though many Americans have come to recognize Töpffer's precedence. ] directly influenced ] and his ].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.thegermanprofessor.com/max-und-moritz/ | title=8 Things about Max und Moritz | date=30 March 2015 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.dw.com/en/max-and-moritz-how-germanys-naughtiest-boys-rose-to-global-fame/a-18808584 | title=Max and Moritz: How Germany's naughtiest boys rose to fame – DW – 10/27/2015 | website=] }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.outdooractive.com/en/story/harz/the-original-story-of-max-and-moritz/28754663/ | title=The original story of Max and Moritz }}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.toonsmag.com/max-and-moritz/ | title=Max and Moritz: A Tale of Mischief and Influence - Toons Mag | date=8 October 2023 }}</ref>{{sfnm|1a1=Gabilliet|1y=2010|1p=xiv|2a1=Beerbohm|2y=2003|3a1=Sabin|3y=2005|3p=186|4a1=Rowland|4y=1990|4p=13}} Japan has a long history of satirical cartoons and comics leading up to the World War II era. The ] artist ] popularized the Japanese term for comics and cartooning, ''{{transl|ja|]}}'', in the early 19th century.{{sfnm|1a1=Petersen|1y=2010|1p=41|2a1=Power|2y=2009|2p=24|3a1=Gravett|3y=2004|3p=9}} In the 1930s ] started a comics studio, which eventually at its height employed 40 artists working for 50 different publishers who helped make the comics medium flourish in "the Golden Age of Comics" after World War II.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1976/09/12/archives/the-funnies-can-be-serious.html|title=The 'Funnies'|last=Ewing|first=Emma Mai|date=1976-09-12|work=The New York Times|access-date=2019-03-05|language=en-US|issn=0362-4331|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181128075857/https://www.nytimes.com/1976/09/12/archives/the-funnies-can-be-serious.html|archive-date=2018-11-28|url-status=live}}</ref> In the post-war era modern Japanese comics began to flourish when ] produced a prolific body of work.{{sfnm|1a1=Couch|1y=2000|2a1=Petersen|2y=2010|2p=175}} Towards the close of the 20th century, these three traditions converged in a trend towards book-length comics: the ] in Europe, the {{transl|ja|]}}{{efn|{{nihongo|tankōbon|単行本|extra=translation close to "independently appearing book"}}}} in Japan, and the ] in the English-speaking countries.{{sfn|Couch|2000}} | |||

| However, these works lack the ability to travel to the reader; it needed the invention of modern printing techniques to allow the form to capture a wide audience and become a ].<ref name="ref9">Perry & Aldridge, 1989. p.11</ref><ref name="ref10">McCloud, 1993. pp.11-14</ref><ref name="ref25">Sabin, 1993. pp.13-14</ref> | |||

| Outside of these genealogies, comics theorists and historians have seen precedents for comics in the ]{{sfnm|1a1=Gabilliet|1y=2010|1p=xiv|2a1=Barker|2y=1989|2p=6|3a1=Groensteen|3y=2014|4a1=Grove|4y=2010|4p=59|5a1=Beaty|5y=2012|p=32|6a1=Jobs|6y=2012|6p=98}} in France (some of which appear to be chronological sequences of images), ], ] in Rome,{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=xiv}} the 11th-century Norman ],{{sfnm|1a1=Gabilliet|1y=2010|1p=xiv|2a1=Beaty|2y=2012|2p=61|3a1=Grove|3y=2010|3pp=16, 21, 59}} the 1370 {{lang|fr|]}} woodcut, the 15th-century {{lang|la|]}} and ]s, Michelangelo's '']'' in the Sistine Chapel,{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=xiv}} and ]'s 18th-century sequential engravings,{{sfn|Grove|2010|p=79}} amongst others.{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=xiv}}{{efn|David Kunzle has compiled extensive collections of these and other proto-comics in his ''The Early Comic Strip'' (1973) and ''The History of the Comic Strip'' (1990).{{sfn|Beaty|2012|p=62}} }} | |||

| ===The 15th–18th centuries and printing advances=== | |||

| ]'s '']'']] | |||

| {{Panorama | |||

| The invention of the ], allowing ], established a separation between images and words, the two requiring different methods in order to be reproduced. Early printed material concentrated on ], but through the 17th and 18th centuries they began to tackle aspects of ] and ], and also started to ] and ]. It was also during this period that the ] was developed as a means of attributing dialogue. | |||

| |image = File:Tapisserie de Bayeux 31109.jpg | |||

| |height = 85 | |||

| |alt = An extremely long embroidered cloth depicting events leading to the Norman conquest of England. | |||

| |caption = Theorists debate whether the ] is a precursor to comics. | |||

| }} | |||

| ===English-language comics=== | |||

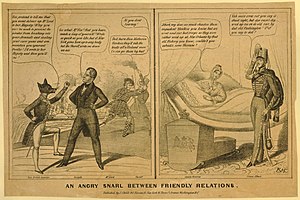

| William Hogarth is often identified in histories of the comics form. His work, '']'', was composed of a number of canvases, each reproduced as a print, and the eight prints together created a narrative. As printing techniques developed, due to the technological advances of the ], magazines and newspapers were established. These publications utilized illustrations as a means of commenting on political and social issues, such illustrations becoming known as cartoons in the 1840s. Soon, artists were experimenting with establishing a sequence of images to create a narrative. | |||

| ] (1840–1841)]] | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | width = 180 | |||

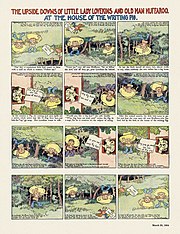

| | footer = ''The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo'', comics by Gustave Verbeek containing ]s and ] sentences (March 1904). | |||

| | image1 = Ambigrams by Gustave Verbeek (1904) - comics The Upside Downs of Little Lady Lovekins and Old Man Muffaroo - At the house of the writing pig.jpg | |||

| | caption1 = ''At the house of the writing pig''. | |||

| }} | |||

| While surviving works of these periods such as ] ''A True Narrative of the Horrid Hellish Popish Plot'' (c.1682) as well as ''The Punishments of Lemuel Gulliver'' and ''A Rake's Progress'' by ] (1726), can be seen to establish a narrative over a number of images, it wasn't until the 19th century that the elements of such works began to crystallise into the ]. | |||

| {{main|British comics|History of American comics|American comic book}} | |||

| Illustrated humour periodicals were popular in 19th-century Britain, the earliest of which was the short-lived '']'' in 1825.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Dempster |first1=Michael |title=Glasgow Looking Glass |url=https://wee-windaes.nls.uk/glasgow-looking-glass/ |website=Wee Windaes |publisher=National Library of Scotland |access-date=20 June 2022}}</ref> The most popular was '']'',{{sfn|Clark|Clark|1991|p=17}} which popularized the term ''cartoon'' for its humorous caricatures.{{sfn|Harvey|2001|p=77}} On occasion the cartoons in these magazines appeared in sequences;{{sfn|Clark|Clark|1991|p=17}} the character ] featured in the earliest serialized comic strip when the character began to feature in its own weekly magazine in 1884.{{sfn|Meskin|Cook|2012|p=xxii}} | |||

| The speech balloon also evolved during this period, from the medieval origins of the ''phylacter'', a label, usually in the form of a scroll, which identified a character either through naming them or using a short text to explain their purpose. Artists such as ] helped codify such ''phylacters'' as balloons rather than as scrolls, although at this time they were still referred to as labels. Although they were now used to represent dialogue, this dialogue was still used for identification purposes rather than to create a dialogue within the work, and artists soon discarded them in favour of running dialogue underneath the panels. The speech balloons weren't reintroduced to the form until ] utilized them as a means of establishing dialogue within his works.<ref name="Speech">Smolderen, Thierry (Summer, 2006) "Of Labels, Loops, and Bubbles: Solving the Historical Puzzle of the Speech Balloon". ''Comic Art'' 8. pp.90-112</ref> | |||

| American comics developed out of such magazines as '']'', '']'', and '']''. The success of illustrated humour supplements in the '']'' and later the '']'', particularly Outcault's ''The Yellow Kid'', led to the development of newspaper comic strips. Early ] were full-page{{sfn|Nordling|1995|p=123}} and often in colour. Between 1896 and 1901 cartoonists experimented with sequentiality, movement, and speech balloons.{{sfn|Gordon|2002|p=35}} An example is ], who wrote his comic series "The UpsideDowns of Old Man Muffaroo and Little Lady Lovekins" between 1903 and 1905. These comics were made in such a way that one could read the 6-panel comic, flip the book and keep reading. He made 64 such comics in total. In 2012, a remake of a selection of the comics was made by Marcus Ivarsson in the book 'In Uppåner med Lilla Lisen & Gamle Muppen'. ({{ISBN|978-91-7089-524-1}}) | |||

| ===The 19th century: a form established=== | |||

| ], whose work is considered influential in shaping the comics form.]] ], a Francophone Swiss artist, is seen as the key figure of the early part of the 19th century. Although speech balloons had fallen from favour during the middle part of the 19th century, Töpffer's sequentially illustrated stories, with the text compartmentalised below the images, were reprinted throughout ] and the ]. The lack of ] at this time allowed such ], and these translated versions created a market on both continents for similar works.<ref name="ref17">Beerbohm, Robert (2003) {{cite web | title=The Adventures of Obadiah Oldbuck Part III | work=The Search For Töpffer In America | url=http://scoop.diamondgalleries.com/scoop_article.asp?ai=2808&si=124 | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=May 30, 2005}}</ref> | |||

| {{wide image | |||

| In 1845 Töpffer formalised his thoughts on the ''picture story'' in his ''Essay on Physiognomics'': "To construct a picture-story does not mean you must set yourself up as a master craftsman, to draw out every potential from your material — often down to the dregs! It does not mean you just devise caricatures with a pencil naturally frivolous. Nor is it simply to dramatize a proverb or illustrate a ]. You must actually invent some kind of play, where the parts are arranged by plan and form a satisfactory whole. You do not merely pen a joke or put a refrain in couplets. You make a book: good or bad, sober or silly, crazy or sound in sense."<ref name="ref18">Translated by Weiss, E. in ''Enter: The Comics'', University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln, pp.4. (1969)</ref><ref name="ref18a"> </ref><ref name="ref18b"></ref> | |||

| |1 = Mr. A. Mutt Starts in to Play the Races 1907.jpg | |||

| |2 = 600px | |||

| |3 = ]'s '']'' (1907–1982) was the first successful daily comic strip (1907).<!-- what's the date?!? --> | |||

| |alt = Five-panel comic strip.}} | |||

| Shorter, black-and-white daily strips began to appear early in the 20th century, and became established in newspapers after the success in 1907 of ]'s '']''.{{sfn|Harvey|1994|p=11}} In Britain, the ] established a popular style of a sequence of images with text beneath them, including '']'' and '']''.{{sfn|Bramlett|Cook|Meskin|2016|p=45}} Humour strips predominated at first, and in the 1920s and 1930s strips with continuing stories in genres such as adventure and drama also became popular.{{sfn|Harvey|1994|p=11}} | |||

| In 1843 the ] which had regularly been appearing in newspapers and magazines gained a name: ]. The British magazine '']'', launched in 1841, referred to its 'humorous pencilings' as cartoons in a satirical reference to the ] of the day, who were themselves organising an exhibition of cartoons, or preparatory drawings, at the time. This usage became common parlance, lasting into the present day.<ref name="ref21">Varnum & Gibbons, 2001. pp.77-78</ref> Similar magazines containing cartoons in continental ] included '']'' and '']'', while in the U.S. '']'' and '']'' were popular.<ref name="ref22">{{cite web | title=Comics | work=St James Encyclopedia of pop culture (2002) | url=http://www.findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_g1epc/is_tov/ai_2419100313 | date format=mdy | accessdate=May 30, 2005}}</ref> | |||

| Thin periodicals called ] appeared in the 1930s, at first reprinting newspaper comic strips; by the end of the decade, original content began to dominate.{{sfn|Rhoades|2008|p=2}} The success in 1938 of '']'' and its lead hero ] marked the beginning of the ], in which the ] was prominent.{{sfn|Rhoades|2008|p=x}} In the UK and the ], the ]-created '']'' (1937) and '']'' (1938) became successful humor-based titles, with a combined circulation of over 2 million copies by the 1950s. Their characters, including "]", "]" and "]" have been read by generations of British children.{{sfn|Childs|Storry|2013|p=532}} The comics originally experimented with superheroes and action stories before settling on humorous strips featuring a mix of the Amalgamated Press and US comic book styles.{{sfn|Bramlett|Cook|Meskin|2016|p=46}} | |||

| 1865 saw the publication of '']'' by ] by a German newspaper. Busch refined the conventions of sequential art, and his work was a key influence within the form, ] was inspired by the strip to create '']'' in 1897.<ref name="ref23">{{cite web | title=comic strip | work=The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001 | url=http://www.bartleby.com/65/co/comicstr.html | date format=mdy | accessdate=June 22, 2005}}</ref> | |||

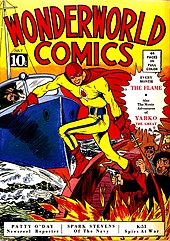

| ] have been a staple of ]s (''Wonderworld Comics'' {{No.}}3, 1939; cover: ] by ]).]] | |||

| It is around this time that ], the ] form of comics, started to formalize, a process that lasted up until 1927.<ref name="Wendy">{{cite book | author=Wong, Wendy Siuyi | title=Hong Kong Comics: A History of Manhua | publisher=Princeton Architectural Press | year=2002 | isbn=1-56898-269-0}}</ref> The introduction of ] printing methods derived from the ] was a critical step in expanding the form within China during the early 20th century. Like Europe and the United States, satirical drawings were appearing in newspapers and periodicals, initially based on works from those countries. One of the first magazines of satirical cartoons was based on the ]'s ''Punch'', snappily re-branded as ''"The China Punch"''.<ref name="Wendy" /> The first piece drawn by a person of Chinese nationality was ''"The Situation in the Far East"'' from ], printed 1899 in ]. By the 1920s a market was established for palm-sized picture books like ].<ref name="Lent">Lent, John A. (2001) Illustrating Asia: Comics, Humor Magazines, and Picture Books. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824824717</ref> | |||

| The popularity of superhero comic books declined in the years following World War II,{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=51}} while comic book sales continued to increase as other genres proliferated, such as ], ], ], ], and humour.{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=49}} Following a sales peak in the early 1950s, the content of comic books (particularly crime and horror) was subjected to scrutiny from parent groups and government agencies, which culminated in ] that led to the establishment of the ] self-censoring body.{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|pp=49–50}} The Code has been blamed for stunting the growth of American comics and maintaining its low status in American society for much of the remainder of the century.{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=50}} Superheroes re-established themselves as the most prominent comic book genre by the early 1960s.{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|pp=52–55}} ] challenged the Code and readers with adult, countercultural content in the late 1960s and early 1970s.{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=66}} The underground gave birth to the ] movement in the 1980s and its mature, often experimental content in non-superhero genres.{{sfnm|1a1=Hatfield|1y=2005|1pp=20, 26|2a1=Lopes|2y=2009|2p=123|3a1=Rhoades|3y=2008|3p=140}} | |||

| In 1884, '']'' was published, a magazine whose selling point was a strip featuring the titular character, and widely regarded as the first comic strip magazine to feature a recurring character. In 1890 two more comic magazines debuted to the British public, '']'' and '']'', establishing the tradition of the ] as an ] periodical containing comic strips.<ref name="ref25">Sabin, 1993. pp.17-21</ref> | |||

| ]'', created by ].]] | |||

| Comics in the US has had a ] reputation stemming from its roots in ]; cultural elites sometimes saw popular culture as threatening culture and society. In the latter half of the 20th century, popular culture won greater acceptance, and the lines between high and low culture began to blur. Comics nevertheless continued to be stigmatized, as the medium was seen as entertainment for children and illiterates.{{sfn|Lopes|2009|pp=xx–xxi}} | |||

| In the ], ] work in combining speech balloons and images on '']'' and ] has been credited as establishing the form and conventions of the comic strip.<ref name="ref27">Sabin, 1993. pp.133-134</ref> Although this view is being revised by current academics, who are uncovering many other works which combine speech bubbles and a multi image narrative, the popularity of Outcalt and the position of the strip in a newspaper is credited as being the driving force of the form.<ref name="ref26">Marschall, Richard (February, 1989). "Oh You Kid". ''The Comics Journal'' 127, p. 72-7</ref><ref name="Walker">Walker, Brian (2004) ''the comics: Before 1945''. ] (United States). ISBN 9780810949706</ref> | |||

| The ]—book-length comics—began to gain attention after ] popularized the term with his book '']'' (1978).{{sfn|Petersen|2010|p=222}} The term became widely known with the public after the commercial success of '']'', '']'', and '']'' in the mid-1980s.{{sfnm|1a1=Kaplan|1y=2008|1p=172|2a1=Sabin|2y=1993|2p=246|3a1=Stringer|3y=1996|3p=262|4a1=Ahrens|4a2=Meteling|4y=2010|4p=1|5a1=Williams|5a2=Lyons|5y=2010|5p=7}} In the 21st century graphic novels became established in mainstream bookstores{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|pp=210–211}} and libraries{{sfn|Lopes|2009|p=151–152}} and webcomics became common.{{sfn|Thorne|2010|p=209}} | |||

| ===The 20th century and the mass medium=== | |||

| {{global}} | |||

| The 1920s and 1930s saw further booms within the industry. In China a market was established for palm-sized picture books like ],<ref name="Lent"/> while the market for comic anthologies in Britain had turned to targeting children through juvenile humor, with '']'' and '']'' launched. In ], ] created the '']'' newspaper strip for ]; this was successfully collected in a bound album and created a market for further such works. The same period in the United States had seen newspaper strips expand their subject matter beyond humour, with action, adventure and mystery strips launched. The collection of such material also began, with '']'', a reprint collection of newspaper strips, published in tabloid size in 1929. | |||

| ===Franco-Belgian and European comics=== | |||

| A market for such comic books soon followed, and by 1938 publishers were printing original material in the format. It was at this point that ] launched, with '']'' as the cover feature. The popularity of the character swiftly enshrined the superhero as the defining genre of American comics, and although the genre fell out of favour in the 1950s, the 1960s saw it re-establish its domination of the form until the late 20th century. | |||

| {{main|European comics|Franco-Belgian comics}} | |||

| In Japan, a country with a long tradition for illustration and whose writing system evolved from pictures, comics were hugely popular. Referred to as ], the Japanese form was established after ] by ], who expanded the page count of a work to number in the hundreds, and who developed a filmic style, heavily influenced by the Disney animations of the time. The Japanese market expanded its range to cover works in many genres, from juvenile fantasy through romance to adult fantasies. Japanese manga is typically published in large anthologies, containing several hundred pages, and the stories told have long been used as sources for adaptation into animated film. In Japan such films are referred to as anime, and many creators will work in both forms simultaneously, leading to an intrinsic linking of the two forms. | |||

| The francophone Swiss ] produced comic strips beginning in 1827,{{sfn|Gabilliet|2010|p=xiv}} and published theories behind the form.{{sfn|Harvey|2010}} ] first published his ] in 1865.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.deutschland.de/en/topic/culture/arts-architecture/150-years-of-max-and-moritz | title=150 years of Max and Moritz | date=22 October 2015 }}</ref> Cartoons appeared widely in newspapers and magazines from the 19th century.{{sfn|Lefèvre|2010|p=186}} The success of '']'' in 1925 popularized the use of speech balloons in European comics, after which Franco-Belgian comics began to dominate.{{sfnm|1a1=Vessels|1y=2010|1p=45|2a1=Miller|2y=2007|2p=17}} '']'', with its signature ] style,{{sfnm|1a1=Screech|1y=2005|1p=27|2a1=Miller|2y=2007|2p=18}} was first serialized in newspaper comics supplements beginning in 1929,{{sfn|Miller|2007|p=17}} and became an icon of Franco-Belgian comics.{{sfnm|1a1=Theobald|1y=2004|1p=82|2a1=Screech|2y=2005|2p=48|3a1=McKinney|3y=2011|3p=3}} | |||

| During the latter half of the 20th century comics have become a very popular ] and from the 1970s American comics publishers have actively encouraged collecting and shifted a large portion of comics publishing and production to appeal directly to the collector's community. | |||

| ], whose works have done much to popularise the medium.]] | |||

| Following the success of {{lang|fr|]}} (est. 1934),{{sfn|Grove|2005|pp=76–78}} dedicated comics magazines{{sfnm|1a1=Petersen|1y=2010|1pp=214–215|2a1=Lefèvre|2y=2010|2p=186}} like '']'' (est. 1938) and '']'' (1946–1993), and full-colour comic albums became the primary outlet for comics in the mid-20th century.{{sfn|Petersen|2010|pp=214–215}} As in the US, at the time comics were seen as infantile and a threat to culture and literacy; commentators stated that "none bear up to the slightest serious analysis",{{efn|{{langx|fr|"... aucune ne supporte une analyse un peu serieuse."}} – Jacqueline & Raoul Dubois in {{lang|fr|La Presse enfantine française}} (Midol, 1957){{sfn|Grove|2005|p=46}} }} and that comics were "the sabotage of all art and all literature".{{sfn|Grove|2005|pp=45–46}}{{efn|{{langx|fr|"C'est le sabotage de tout art et de toute littérature."}} – Jean de Trignon in {{lang|fr|Histoires de la littérature enfantine de ma Mère l'Oye au Roi Babar}} (], 1950){{sfn|Grove|2005|p=46}} }} | |||

| Writing in 1972, Sir ] certainly felt Töpffer to have evolved a new pictorial language, that of an abbreviated art style, which worked by allowing the audience to fill in gaps with their own imagination.<ref name="ref19">{{cite book | author=Gombrich, E.H. | title=Art and illusion: A study in the psychology of pictorial representation | location=London | publisher=Phaidon Press | year=1972 | isbn=0-691-01750-6}}</ref> | |||

| In the 1960s, the term {{lang|fr|bandes dessinées}} ("drawn strips") came into wide use in French to denote the medium.{{sfn|Grove|2005|p=51}} Cartoonists began creating comics for mature audiences,{{sfnm|1a1=Miller|1y=1998|1p=116|2a1=Lefèvre|2y=2010|2p=186}} and the term "Ninth Art"{{efn|{{langx|fr|neuvième art}} }} was coined, as comics began to attract public and academic attention as an artform.{{sfn|Miller|2007|p=23}} A group including ] and ] founded the magazine '']'' in 1959 to give artists greater freedom over their work. Goscinny and Uderzo's '']'' appeared in it{{sfn|Miller|2007|p=21}} and went on to become the best-selling French-language comics series.{{sfn|Screech|2005|p=204}} From 1960, the satirical and taboo-breaking '']'' defied censorship laws in the countercultural spirit that led to the ].{{sfn|Miller|2007|p=22}} | |||

| The modern double usage of the term ''comic'', as an adjective describing a genre, and a noun designating an entire medium, has been criticised as confusing and misleading. In the 1960s and 1970s, underground cartoonists used the spelling '']'' to distinguish their work from mainstream newspaper strips and juvenile comic books; ironically, although their work was written for an adult audience, it was usually comedic in nature as well, so the "comic" label was still appropriate.<ref name="ref37">Arnold, 2001.</ref> The term '']'' was popularised in the late 1970s, having been coined at least two decades previous, to distance the material from this confusion.<ref name="ref38">''Var.'' (2003-4) {{cite web | title=The history of the term 'graphic novel' ... | work=As Archived At http://www.geocities.com/rucervine/ | url=http://www.geocities.com/rucervine/ | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=June 26, 2005}}</ref> | |||

| Frustration with censorship and editorial interference led to a group of ''Pilote'' cartoonists to found the adults-only '']'' in 1972. Adult-oriented and experimental comics flourished in the 1970s, such as in the experimental science fiction of ] and others in '']'', even mainstream publishers took to publishing prestige-format ].{{sfn|Miller|2007|pp=25–28}} | |||

| In the 1980s comics scholarship started to blossom in the U.S.,<ref name="ref39">Taylor, Laurie; Martin, Cathlena; & Houp, Trena (2004) {{cite web | title=Introduction | work=ImageTexT Exhibit 1 (Fall 2004) | url=http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/archives/exhibit1/introduction.shtml | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=June 26, 2005}}</ref> and a resurgence in the popularity of comics was seen, with ] and ] producing notable superhero works and ]'s '']'' being syndicated. | |||

| From the 1980s, mainstream sensibilities were reasserted and serialization became less common as the number of comics magazines decreased and many comics began to be published directly as albums.{{sfn|Miller|2007|pp=33–34}} Smaller publishers such as ]{{sfn|Beaty|2007|p=9}} that published longer works{{sfn|Lefèvre|2010|pp=189–190}} in non-traditional formats{{sfn|Grove|2005|p=153}} by '']''-istic creators also became common. Since the 1990s, mergers resulted in fewer large publishers, while smaller publishers proliferated. Sales overall continued to grow despite the trend towards a shrinking print market.{{sfn|Miller|2007|pp=49–53}} | |||

| In 2005 ]'s work was exhibited in galleries both sides of the Atlantic, and ''The Guardian'' newspaper devoted its tabloid supplement to a week long exploration of his work and idioms.<ref name="ref40">''Var.'' (March 7-11, 2005) {{cite web | title=G2 in Crumbland | work=The Guardian Newspaper Special Report | url=http://www.guardian.co.uk/arts/crumb/0,15829,1430764,00.html | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=June 26, 2005}}</ref> | |||

| ===Japanese comics=== | |||

| ==Forms== | |||

| ], ] comics artist, signing autographs in 1994.]] | |||

| Comics have been presented within a wide number of publishing and typographical formats, from the very short ] to the more lengthy ]. The ], traditionally containing ] or ] content in the manner of those seen in '']'' or '']'', originate from the mid nineteenth century. This form of comics is still popular, although the last few years has seen a reduction in the number of editorial cartoonists employed in the US media.<ref>Chris Lamb, , February 18, 2004. The Digital Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved ].</ref> Although there is some dispute as to whether the cartoon constitutes a form of comics, a precursor or a related form, it has been argued that since the cartoon both combines words with image and constructs a narrative, it merits inclusion as a form of comics. | |||

| {{main|History of manga|Manga}} | |||

| The ] is simply a sequence of cartoons which unite to tell a story within that sequence, and were originally known as strip cartoons. Originally the term comic strip was used to apply to any sequence of cartoons, no matter the venue of publication or length of the sequence, but now, mainly in the ], the term refers to the strips published in newspapers. These strips are now typically humorous or satirical strips, such as ] and ], but have often been action themed, educational or even biographical. In the ] the term "comics" is sometimes used to describe the page of a newspaper upon which comic strips are found, with the term "comic" quickly adopting through popular usage to refer to the form rather than the content.<ref name="ref29">Sabin, 1993. pp.137-139</ref><ref name="ref30">Bell, John and Viau, Michel (2002). {{cite web | title=Emergence of the Comic Book, 1929-1940 | work=Beyond the Funnies | url=http://www.collectionscanada.ca/comics/027002-8200-e.html | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=May 30, 2005}}</ref> Said pages are also referred to as the "funny pages", and comics are hence sometimes called "the funnies".<ref>] (1994). ''The art of the funnies: An aesthetic history''. ]</ref> In the ], the term comic strip is still applied to the longer stories which appear in comics such as '']'' or '']''. | |||

| ] created the first modern Japanese comic strip. (''Tagosaku to Mokube no Tōkyō Kenbutsu'',{{efn|{{Nihongo|''Tagosaku and Mokube Sightseeing in Tokyo''|田吾作と杢兵衛の東京見物|''Tagosaku to Mokube no Tokyo Kenbutsu''|lead=yes}} }} 1902)]] | |||

| ===Publication formats=== | |||

| Over time a number of formats have become closely associated with the form, from the ] to the ]. The ] originated in the early part of the twentieth century, and grew from magazines which repackaged comic strips. Eventually, original material was commissioned, and the material developed from its humorous origins to encompass adventure stories, romance, war and superheroes, with the latter genre coming to dominate the comic book publishing industry in the latter parts of the twentieth century. Although referred to as comic books, these publications are actually more akin to magazines, having soft covers printed on glossy paper, with the interiors consisting of newsprint quality paper or higher grade. In Europe, magazines were always a venue for original material in the form, and such comic magazines or comic books soon grew into anthologies, in which a number of stories would be serialised. In continental Europe a market soon established itself to support collections of these strips. All of these publications are generally referred to as "comics" for short, with typical American and British comic books or magazines running 32 pages, including advertisements and ]. (These are sometimes known as 36-page books, counting the covers.) European comic magazines have wildly varying page numbers, currently ranging mostly between 52 and 120 pages, while European comic albums traditionally had between 32 and 62 pages. | |||

| ]s on display for sale in a specialist shop.]] | |||

| Japanese comics and cartooning (''{{transl|ja|]}}''),{{efn|{{Nihongo|''"Manga"''|漫画||lead=yes}} can be ] in many ways, amongst them "whimsical pictures", "disreputable pictures",{{sfn|Karp|Kress|2011|p=19}} "irresponsible pictures",{{sfn|Gravett|2004|p=9}} "derisory pictures", and "sketches made for or out of a sudden inspiration".{{sfn|Johnson-Woods|2010|p=22}} }} have a history that has been seen as far back as the anthropomorphic characters in the 12th-to-13th-century ''{{transl|ja|]}}'', 17th-century ''{{transl|ja|]}}'' and ''{{transl|ja|]}}'' picture books,{{sfn|Schodt|1996|p=22}} and ] such as ] which were popular between the 17th and 20th centuries. The ''{{transl|ja|kibyōshi}}'' contained examples of sequential images, movement lines,{{sfn|Mansfield|2009|p=253}} and sound effects.{{sfn|Petersen|2010|p=42}} | |||

| In the United States, when a publisher collects previously serialised stories, such a collection is commonly referred to as either a ] or as a ]. These are books, typically squarebound and published with a card cover, containing no adverts. They generally collect a single story, which has been broken into a number of chapters previously serialised in comic books, with the issues collectively known as a story arc. Such trade paperbacks can contain anywhere from four issues (for example, there is '']'' by ] and ]) to as many as twenty ('']''). In continental Europe, especially ] and ], such collections are usually somewhat larger in size and published with a hardback cover, a format established by the '']''' series in the 1930s. These are referred to as '''comic albums''',<ref name="ref31">Ferguson, Andrew (1999). {{cite web | title=Tintin Books - US/English editions | work=Hergé and Tintin | url=http://www.princeton.edu/~ferguson/adw/tintin/biblio.htm | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=June 25, 2005}}</ref> a term which in the United States refers to anthology books. The United Kingdom has no great tradition of such collections, although during the 1980s Titan publishing launched a line collecting stories previously published in ]. | |||

| Illustrated magazines for Western expatriates introduced Western-style satirical cartoons to Japan in the late 19th century. New publications in both the Western and Japanese styles became popular, and at the end of the 1890s, American-style newspaper comics supplements began to appear in Japan,{{sfn|Johnson-Woods|2010|pp=21–22}} as well as some American comic strips.{{sfn|Schodt|1996|p=22}} 1900 saw the debut of the ''Jiji Manga'' in the ''Jiji Shinpō'' newspaper—the first use of the word "manga" in its modern sense,{{sfn|Johnson-Woods|2010|p=22}} and where, in 1902, ] began the first modern Japanese comic strip.{{sfnm|1a1=Petersen|1y=2010|1p=128|2a1=Gravett|2y=2004|2p=21}} By the 1930s, comic strips were serialized in large-circulation monthly girls' and boys' magazine and collected into hardback volumes.{{sfnm|1a1=Schodt|1y=1996|1p=22|2a1=Johnson-Woods|2y=2010|2pp=23–24}} | |||

| The graphic novel format is similar to typical book publishing, with works being published in both hardback and paperback editions. The term has proved a difficult one to fully define, and refers not only to fiction but also factual works, and is also used to describe collections of previously serialised works as well as original material. Some publishers will distinguish between such material, using the term "original graphic novel" for work commissioned especially for the form. | |||

| The modern era of comics in Japan began after World War II, propelled by the success of the serialized comics of the prolific ]{{sfn|Gravett|2004|p=24}} and the comic strip '']''.{{sfnm|1a1=MacWilliams|1y=2008|1p=3|2a1=Hashimoto|2a2=Traphagan|2y=2008|2p=21|3a1=Sugimoto|3y=2010|3p=255|4a1=Gravett|4y=2004|4p=8}} Genres and audiences diversified over the following decades. Stories are usually first serialized in magazines which are often hundreds of pages thick and may contain over a dozen stories;{{sfnm|1a1=Schodt|1y=1996|1p=23|2a1=Gravett|2y=2004|2pp=13–14}} they are later compiled in {{transl|ja|]}}-format books.{{sfn|Gravett|2004|p=14}} At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, nearly a quarter of all printed material in Japan was comics.{{sfnm|1a1=Brenner|1y=2007|1p=13|2a1=Lopes|2y=2009|2p=152|3a1=Raz|3y=1999|3p=162|4a1=Jenkins|4y=2004|4p=121}} Translations became extremely popular in foreign markets—in some cases equaling or surpassing the sales of domestic comics.{{sfn|Lee|2010|p=158}} | |||

| Newspaper strips also get collected, both in Europe and in the United States, and these are sometimes also referred to as graphic novels.{{Fact|date=November 2008}} In the US, the selection of strips to be reprinted in books has often been somewhat haphazard, but there have been several recent efforts to produce complete collections of the more popular newspaper strips. | |||

| ==Forms and formats== | |||

| In the UK it is traditional for the children's comics market to release comic annuals, which are hardback books containing strips, as well as text stories and puzzles and games.<ref>Ezard, John (December 24, 2005) "They dealt with Dan. Now Dana and Yasmin target Dennis" '']''. p.7</ref><ref>Jones, Gwyn (February 18, 2006) "Beano! It's just Dandy to have an Eagle eye...". '']''. p.20</ref><ref>Brown, Michael (December 7, 2002) "Review: Children's history: Real life" '']''. p.36</ref> In the United States, the comic annual was a summer publication, typically an extended comic book, with storylines often linked across a publisher's line of comics. | |||

| ]s are generally short, multipanel comics that have, since the early 20th century, most commonly appeared in newspapers. In the US, daily strips have normally occupied a single tier, while ] have been given multiple tiers. Since the early 20th century, daily newspaper comic strips have typically been printed in black-and-white and Sunday comics have usually been printed in colour and have often occupied a full newspaper page.{{sfn|Booker|2014|p=xxvi–xxvii}} | |||

| In Japan, comics are usually first serialized in ]s and latter compiled in ] format. | |||

| Specialized comics periodicals formats vary greatly in different cultures. ]s, primarily an American format, are thin periodicals{{sfnm|1a1=Orr|1y=2008|1p=11|2a1=Collins|2y=2010|2p=227}} usually published in colour.{{sfn|Orr|2008|p=10}} European and Japanese comics are frequently serialized in magazines—monthly or weekly in Europe,{{sfn|Johnson-Woods|2010|p=22}} and usually black-and-white and weekly in Japan.{{sfnm|1a1=Schodt|1y=1996|1p=23|2a1=Orr|2y=2008|2p=10}} Japanese comics magazine typically run to hundreds of pages.{{sfn|Schodt|1996|p=23}} | |||

| ], also known as online comics and web comics, are comics that are available on the ]. Many webcomics are exclusively ] ], while some are published in print but maintain a web ] for either commercial or artistic reasons. With the Internet's easy access to an audience, webcomics run the gamut from traditional ]s to graphic novels and beyond. | |||

| {{wide image | |||

| Webcomics are similar to self-published print comics in that almost anyone can create their own webcomic and publish it on the Web. Currently, there are thousands of webcomics available online, with some achieving popular, critical, or commercial success. '']'' is syndicated in print, while Brian Fies' '']'' won the inaugural ] for digital comics in 2005 and was subsequently collected and published in hardback. | |||

| |1 = Comics volumes - international comparison.jpg | |||

| |2 = 600px | |||

| |3 = A comparison of book formats for comics around the world. The left group is from Japan and shows the {{transl|ja|]}} and the smaller {{transl|ja|]}} formats. Those in the middle group of ] are in the standard ] ] format. The right group of ]s is from English-speaking countries, where there is no standard format.}} | |||

| Book-length comics take different forms in different cultures. European ] are most commonly colour volumes printed at ], a larger page size than used in many other cultures.{{sfnm|1a1=Grove|1y=2010|1p=24|2a1=McKinney|2y=2011|p={{not a typo|xiii}}}}{{sfn|Petersen|2010|pp=214–215}} In English-speaking countries, the ] format originating from collected comic books have also been chosen for original material. Otherwise, bound volumes of comics are called graphic novels and are available in various formats. Despite incorporating the term "novel"—a term normally associated with fiction—"graphic novel" also refers to non-fiction and collections of short works.{{sfnm|1a1=Goldsmith|1y=2005|1p=16|2a1=Karp|2a2=Kress|2y=2011|2pp=4–6}} Japanese comics are collected in volumes called {{Lang|ja-latn|]}} following magazine serialization.{{sfn|Poitras|2001|p=66–67}} | |||

| The comics form can also be utilized to convey information in mixed media. For example, strips designed for educative or informative purposes, notably the instructions upon an airplane's safety card. These strips are generally referred to as instructional comics. The comics form is also utilized in the film and animation industry, through storyboarding. ]s are ]s displayed in sequence for the purpose of visualizing an animated or live-action ]. | |||

| A storyboard is essentially a large comic of the film or some section of the film produced beforehand to help the directors and cinematographers visualize the scenes and find potential problems before they occur. Often storyboards include arrows or instructions that indicate movement. | |||

| ] and ]s usually consist of a single panel, often incorporating a caption or speech balloon. Definitions of comics which emphasize sequence usually exclude gag, editorial, and other single-panel cartoons; they can be included in definitions that emphasize the combination of word and image.{{sfn|Harvey|2001|p=76}} Gag cartoons first began to proliferate in ]s published in Europe in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the term "cartoon"{{efn|"]": from the Italian {{lang|it|cartone}}, meaning "card", which referred to the cardboard on which the cartoons were typically drawn.{{sfn|Harvey|2001|p=77}} }} was first used to describe them in 1843 in the British humour magazine '']''.{{sfn|Harvey|2001|p=77}} | |||

| Like many other media, comics can also be ]. One typical format for self-publishers and aspiring professionals is the ], typically small, often ] and stapled or with a handmade binding. These are a common inexpensive way for those who want to make their own comics on a very small budget, with mostly informal means of ]. A number of ]s have started this way and gone on to more traditional types of publishing, while other more established artists continue to produce minicomics on the side. | |||

| ]s are comics that are available on the internet, first being published the 1980s. They are able to potentially reach large audiences, and new readers can often access archives of previous installments.{{sfn|Petersen|2010|pp=234–236}} Webcomics can make use of an ], meaning they are not constrained by the size or dimensions of a printed comics page.{{sfnm|1a1=Petersen|1y=2010|1p=234|2a1=McCloud|2y=2000|2p=222}} | |||

| ==Artistic medium== | |||

| ===Defining comics=== | |||

| Some consider ]s{{sfn|Rhoades|2008|p=38}} and ]s to be comics.{{sfn|Beronä|2008|p=225}} Film studios, especially in animation, often use sequences of images as guides for film sequences. These storyboards are not intended as an end product and are rarely seen by the public.{{sfn|Rhoades|2008|p=38}} Wordless novels are books which use sequences of captionless images to deliver a narrative.{{sfn|Cohen|1977|p=181}} | |||

| ==Comics studies== | |||

| {{Main|Comics studies}} | |||

| <!-- ''Note: Although it takes the form of a plural noun, the common usage when referring to ''comics'' as a medium is to treat it as singular.'' --> | <!-- ''Note: Although it takes the form of a plural noun, the common usage when referring to ''comics'' as a medium is to treat it as singular.'' --> | ||

| {{quote box|"Comics ... are sometimes four-legged and sometimes two-legged and sometimes fly and sometimes don't ... to employ a metaphor as mixed as the medium itself, defining comics entails cutting a Gordian-knotted enigma wrapped in a mystery ..."|source=], 2001{{sfn|Harvey|2001|p=76}}|width=30em}} | |||

| Scholars disagree on the definition of comics; some claim its printed format is crucial, some emphasize the interdependence of image and text, and others its sequential nature. The term as a reference to the medium has also been disputed. | |||

| Similar to the problems of defining literature and film,{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|pp=128—129}} no consensus has been reached on a definition of the comics medium,{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|p=124}} and attempted definitions and descriptions have fallen prey to numerous exceptions.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|p=126}} Theorists such as Töpffer,{{sfn|Thomas|2010|p=158}} ], ],{{sfn|Beaty|2012|p=65}} David Carrier,{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|pp=126, 131}} Alain Rey,{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|p=124}} and Lawrence Grove emphasize the combination of text and images,{{sfn|Grove|2010|pp=17–19}} though there are prominent examples of pantomime comics throughout its history.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|p=126}} Other critics, such as Thierry Groensteen{{sfn|Grove|2010|pp=17–19}} and Scott McCloud, have emphasized the primacy of sequences of images.{{sfn|Thomas|2010|pp=157, 170}} Towards the close of the 20th century, different cultures' discoveries of each other's comics traditions, the rediscovery of forgotten early comics forms, and the rise of new forms made defining comics a more complicated task.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|pp=112–113}} | |||

| ], who established the term sequential art and is considered to have popularised the ].]]In 1996, ] published ''Graphic Storytelling'', in which he defined comics as "the printed arrangement of art and ] in sequence, particularly in comic books."<ref name="ref4">{{cite book | author=Eisner, Will | title=Graphic Storytelling | publisher=Poorhouse Press | year=1996 | isbn=0-9614728-2-0}}</ref> Eisner's earlier, more influential definition from 1985's '']'' described the technique and structure of comics as ''sequential art'', "...the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea."<ref name="ref3">{{cite book | author=Eisner, Will | title=Comics & Sequential Art | publisher=Poorhouse Press | year=1990 Expanded Edition, reprinted 2001|isbn=0-9614728-1-2}}</ref> | |||

| European comics studies began with Töpffer's theories of his own work in the 1840s, which emphasized panel transitions and the visual–verbal combination. No further progress was made until the 1970s.{{sfn|Miller|2007|p=101}} Pierre Fresnault-Deruelle then took a ] approach to the study of comics, analyzing text–image relations, page-level image relations, and image discontinuities, or what Scott McCloud later dubbed "closure".{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|p=112}} In 1987, Henri Vanlier introduced the term {{lang|fr|multicadre}}, or "multiframe", to refer to the comics page as a semantic unit.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|p=113}} By the 1990s, theorists such as ] and ] turned attention to artists' ] creative choices.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|p=112}} ] and Harry Morgan have held relativistic views of the definition of comics, a medium that has taken various, equally valid forms over its history. Morgan sees comics as a subset of "{{lang|fr|les littératures dessinées}}" (or "drawn literatures").{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|pp=112–113}} French theory has come to give special attention to the page, in distinction from American theories such as McCloud's which focus on panel-to-panel transitions.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|p=113}} In the mid-2000s, ] began analyzing how comics are understood using tools from cognitive science, extending beyond theory by using actual psychological and neuroscience experiments. This work has argued that sequential images and page layouts both use separate rule-bound "grammars" to be understood that extend beyond panel-to-panel transitions and categorical distinctions of types of layouts, and that the brain's comprehension of comics is similar to comprehending other domains, such as language and music.{{sfn|Cohn|2013}} | |||

| In '']'' (1993) ] defined sequential art and comics as: "juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer";<ref name="ref5">McCloud, 1993. p.7-9</ref> this definition excludes single-panel illustrations such as '']'', '']'', and most ]s from the category, classifying those as ]s. By contrast, ] ''"100 Best Comics of the 20th Century"'',<ref name="ref6">Spurgeon, Tom ''et al.'' (February 1999) "Top 100 (English Language) Comics of the Century". ''The Comics Journal'' 210.</ref> included the works of several single panel cartoonists and a caricaturist, and academic study of comics has included political cartoons.<ref></ref> | |||

| Historical narratives of ''manga'' tend to focus either on its recent, post-WWII history, or on attempts to demonstrate deep roots in the past, such as to the ''{{transl|ja|Chōjū-jinbutsu-giga}}'' picture scroll of the 12th and 13th centuries, or the early 19th-century ''Hokusai Manga''.{{sfn|Stewart|2014|pp=28–29}} The first historical overview of Japanese comics was Seiki Hosokibara's {{transl|ja|Nihon Manga-Shi}}{{efn|{{cite book|last=Hosokibara|first=Seiki|trans-title=Japanese Comics History|title=日本漫画史|publisher=Yuzankaku|year=1924}} }} in 1924.{{sfnm|1a1=Johnson-Woods|1y=2010|1p=23|2a1=Stewart|2y=2014|2p=29}} Early post-war Japanese criticism was mostly of a left-wing political nature until the 1986 publication of Tomofusa Kure's ''Modern Manga: The Complete Picture'',{{efn|{{cite book|first=Tomofusa|last=Kure|trans-title=Modern Manga: The Complete Picture|title=現代漫画の全体像|publisher=Joho Center Publishing|year=1986|isbn=978-4-575-71090-8}}{{sfn|Kinsella|2000|pp=96–97}} }} which de-emphasized politics in favour of formal aspects, such as structure and a "grammar" of comics. The field of {{transl|ja|manga}} studies increased rapidly, with numerous books on the subject appearing in the 1990s.{{sfn|Kinsella|2000|pp=96–97}} Formal theories of ''{{transl|ja|manga}}'' have focused on developing a "manga expression theory",{{efn|{{Nihongo|"Manga expression theory"|漫画表現論|manga hyōgenron|lead=yes}}{{sfn|Kinsella|2000|p=100}} }} with emphasis on spatial relationships in the structure of images on the page, distinguishing the medium from film or literature, in which the flow of time is the basic organizing element.{{sfn|Kinsella|2000|p=100}} Comics studies courses have proliferated at Japanese universities, and Japan Society for Studies in Cartoon and Comics {{small|(])}}{{efn|{{Nihongo|Japan Society for Studies in Cartoon and Comics|日本マンガ学会|Nihon Manga Gakkai|lead=yes}} }} was established in 2001 to promote comics scholarship.{{sfn|Morita|2010|pp=37–38}} The publication of ]'s '']'' in 1983 led to the spread of use of the word ''manga'' outside Japan to mean "Japanese comics" or "Japanese-style comics".{{sfn|Stewart|2014|p=30}} | |||

| R.C. Harvey, in his essay ''Comedy At The Juncture Of Word And Image'', offered a competing definition in reference to McCloud's: "...comics consist of pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa."<ref name="ref7">Varnum & Gibbons, 2001. p.76</ref> This, however, ignores the existence of wordless comics. | |||

| {{Multiple image | |||

| Most agree that ], which creates the optical illusion of movement within a static physical frame, is a separate form, although ], a peer-reviewed academic journal focusing on comics, accepts submissions relating to animation as well,<ref></ref> and the third annual Conference on Comics at the ] focused on comics and animation.<ref></ref> | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | total_width = 300 | |||

| | direction = | |||

| | image1 = Will Eisner (San Diego Comic Con, 2004).jpg | |||

| | alt1 = An elderly bald man wearing glasses. | |||

| | image2 = Scott McCloud.Making Comics Tour.RISD.gk.JPG | |||

| | alt2 = A middle-aged man seated behind a table, facing the camera. | |||

| | footer = ] ''(left)'' and ] (right) have proposed influential and controversial definitions of comics. | |||

| }} | |||

| ] attempted the first comprehensive history of American comics with ''The Comics'' (1947).{{sfn|Inge|1989|p=214}} Will Eisner's '']'' (1985) and ]'s '']'' (1993) were early attempts in English to formalize the study of comics. David Carrier's ''The Aesthetics of Comics'' (2000) was the first full-length treatment of comics from a philosophical perspective.{{sfn|Meskin|Cook|2012|p=xxix}} Prominent American attempts at definitions of comics include Eisner's, McCloud's, and Harvey's. Eisner described what he called "]" as "the arrangement of pictures or images and words to narrate a story or dramatize an idea";{{sfnm|1a1=Yuan|1y=2011|2a1=Eisner|2y=1985|2p=5}} Scott McCloud defined comics as "juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer",{{sfnm|1a1=Kovacs|1a2=Marshall|1y=2011|1p=10|2a1=Holbo|2y=2012|2p=13|3a1=Harvey|3y=2010|3p=1|4a1=Beaty|4y=2012|4p=6|5a1=McCloud|5y=1993|5p=9}} a strictly formal definition which detached comics from its historical and cultural trappings.{{sfn|Beaty|2012|p=67}} R. C. Harvey defined comics as "pictorial narratives or expositions in which words (often lettered into the picture area within speech balloons) usually contribute to the meaning of the pictures and vice versa".{{sfnm|1a1=Chute|1y=2010|1p=7|2a1=Harvey|2y=2001|2p=76}} Each definition has had its detractors. Harvey saw McCloud's definition as excluding single-panel cartoons,{{sfn|Harvey|2010|p=1}} and objected to McCloud's de-emphasizing verbal elements, insisting "the essential characteristic of comics is the incorporation of verbal content".{{sfn|Groensteen|2012a|p=113}} Aaron Meskin saw McCloud's theories as an artificial attempt to legitimize the place of comics in art history.{{sfn|Beaty|2012|p=65}} | |||

| ===Art styles=== | |||

| ], whose work '']'' identified the different styles of art used within comics.]] While almost all comics art is in some sense abbreviated, and also while every artist who has produced comics work brings their own individual approach to bear, some broader art styles have been identified. | |||

| Cross-cultural study of comics is complicated by the great difference in meaning and scope of the words for "comics" in different languages.{{sfn|Morita|2010|p=33}} The French term for comics, {{lang|fr|bandes dessinées}} ("drawn strip") emphasizes the juxtaposition of drawn images as a defining factor,{{sfnm|1a1=Groensteen|1y=2012|1p=130|2a1=Morita|2y=2010|2p=33}} which can imply the exclusion of even photographic comics.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|p=130}} The term ''{{transl|ja|manga}}'' is used in Japanese to indicate all forms of comics, cartooning,{{sfn|Johnson-Woods|2010|p=336}} and caricature.{{sfn|Morita|2010|p=33}} | |||

| The basic styles have been identified as ] and cartoony, with a huge middle ground for which ] has coined the phrase liberal. Fiore has also expressed distaste with the terms realistic and cartoony, preferring the terms literal and freestyle, respectively.<ref name="Fiore 2005">Fiore, 2005. </ref> | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| Scott McCloud has created <ref name="ref44">McCloud, 1993.</ref> as a tool for thinking about comics art. He places the realistic representation in the bottom left corner, with ] representation, or cartoony art, in the bottom right, and a third identifier, ] of image, at the apex of the triangle. This allows the placement and grouping of artists by ]. | |||

| *The cartoony style is one which utilises comic effects and a variation of line widths as a means of expression. Characters here tend to have rounded, simplified anatomy. Noted exponents of this style are ] and ].<ref name="Fiore 2005"/> | |||

| *The realistic style, also referred to as the adventure style is the one developed for use within the adventure strips of the 1930s. They required a less cartoony look, focusing more on realistic anatomy and shapes, and used the ] found in ] as a basis.<ref name="ref46">''.''</ref> This style became the basis of the superhero comic book style, since ] and ] originally worked '']'' up for publication as an adventure strip.<ref name="ref47">Santos, 1998. </ref> | |||

| {{Main|Glossary of comics terminology}} | |||

| Scott McCloud also notes that in several traditions, there is a tendency to have the main characters drawn rather simplistic and cartoony, while the backgrounds and environment are depicted realistically. Thus, he argues, the reader easily identifies with the characters, (as they are similar to one's idea of self), whilst being immersed into a world, that's three-dimensional and textured.<ref name="ref48">McCloud, 1993.</ref> Good examples of this phenomenon include ]'s '']'' (in his "personal trademark" ] style), ]'s '']'' and ]'s '']'', among many others. | |||

| The term ''comics'' refers to the comics medium when used as an ] and thus takes the singular: "comics ''is'' a medium" rather than "comics ''are'' a medium". When ''comic'' appears as a countable noun it refers to instances of the medium, such as individual comic strips or comic books: "Tom's comics ''are'' in the basement."{{sfnm|1a1=Chapman|1y=2012|1p=8|2a1=Chute|2a2=DeKoven|2y=2012|2p=175|3a1=Fingeroth|3y=2008|3p=4}} | |||

| ===The language=== | |||

| As noted above, two distinct definitions have been used to define comics as an art form: the combination of both word and image; and the placement of images in sequential order. Both definitions are lacking, in that the first excludes any sequence of wordless images; and the second excludes single panel cartoons such as editorial cartoons. The purpose of comics is certainly that of ], and so that must be an important factor in defining the art form. | |||

| Panels are individual images containing a segment of action,{{sfn|Lee|1978|p=15}} often surrounded by a border.{{sfn|Eisner|1985|pp=28, 45}} Prime moments in a narrative are broken down into panels via a process called encapsulation.{{sfn|Duncan|Smith|2009|p=10}} The reader puts the pieces together via the process of closure by using background knowledge and an understanding of panel relations to combine panels mentally into events.{{sfn|Duncan|Smith|2009|p=316}} The size, shape, and arrangement of panels each affect the timing and pacing of the narrative.{{sfn|Eisner|1985|p=30}} The contents of a panel may be asynchronous, with events depicted in the same image not necessarily occurring at the same time.{{sfnm|1a1=Duncan|1a2=Smith|1y=2009|1p=315|2a1=Karp|2a2=Kress|2y=2011|2p=12–13}} | |||

| Comics, as sequential art, emphasise the pictorial representation of a narrative. This means comics are not an illustrated version of standard ], and while some critics argue that they are a hybrid form of ] and literature, others contend comics are a new and separate art; an integrated whole, of words and images both, where the pictures do not just depict the story, but are part of the telling. In comics, creators transmit ] through arrangement and ] of either pictures alone, or word(s) and picture(s), to build a narrative. | |||

| ]s. The tail of the balloon indicates the speaker.]] | |||

| The narration of a comic is set out through the layout of the images, and while there may be many people who work on one work, like ]s, there is one vision of the narrative which guides the work. The layout of images on a page can be utilised by artists to convey the passage of time, to build suspense or to highlight action.<ref name="ref49">Driest, Joris (2005). "". Retrieved May 26, 2005. PDF</ref> | |||

| Text is frequently incorporated into comics via ]s, captions, and sound effects. Speech balloons indicate dialogue (or thought, in the case of ]s), with tails pointing at their respective speakers.{{sfnm|1a1=Lee|1y=1978|1p=15|2a1=Markstein|2y=2010|3a1=Eisner|3y=1985|3p=157|4a1=Dawson|4y=2010|4p=112|5a1=Saraceni|5y=2003|5p=9}} Captions can give voice to a narrator, convey characters' dialogue or thoughts,{{sfnm|1a1=Lee|1y=1978|1p=15|2a1=Lyga|2a2=Lyga|2y=2004|p=161}} or indicate place or time.{{sfnm|1a1=Saraceni|1y=2003|1p=9|2a1=Karp|2a2=Kress|2y=2011|2p=18}} Speech balloons themselves are strongly associated with comics, such that the addition of one to an image is sufficient to turn the image into comics.{{sfn|Forceville|Veale|Feyaerts|2010|p=56}} Sound effects mimic non-vocal sounds textually using ] sound-words.{{sfn|Duncan|Smith|2009|pp=156, 318}} | |||

| For a fuller exploration of the language, please see ]. | |||

| ] is most frequently used in making comics, traditionally using ink (especially ]) with ]s or ink brushes;{{sfnm|1a1=Markstein|1y=2010|2a1=Lyga|2a2=Lyga|2y=2004|2p=161|3a1=Lee|3y=1978|3p=145|4a1=Rhoades|4y=2008|4p=139}} mixed media and digital technology have become common. Cartooning techniques such as ]{{sfnm|1a1=Bramlett|1y=2012|1p=25|2a1=Guigar|2y=2010|2p=126|3a1=Cates|3y=2010|3p=98}} and abstract symbols are often employed.{{sfnm|1a1=Goldsmith|1y=2005|1p=21|2a1=Karp|2a2=Kress|2y=2011|2p=13–14}} | |||

| ===Comic creation=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Comics artists will generally sketch a drawing in pencil before going over the drawing again in ink, using either a ] or a ]. Artists will also make use of a ] when creating the final image in ink. Some artists, ] being a notable example,<ref name="ref41">(2003), {{cite web | title=The Moles Interview No 5: Brian Bolland | work= | url=http://www.theresidents.co.uk/articles/interviews/bolland.htm | dateformat=mdy | accessdate=June 26, 2005}}</ref> are now using digital means to create artwork, with the published work being the first physical appearance of the artwork. | |||

| While comics are often the work of a single creator, the labour of making them is frequently divided between a number of specialists. There may be separate ] and ], and artists may specialize in parts of the artwork such as characters or backgrounds, as is common in Japan.{{sfn|O'Nale|2010|p=384}} Particularly in American superhero comic books,{{sfn|Tondro|2011|p=51}} the art may be divided between a ], who lays out the artwork in pencil;{{sfn|Lyga|Lyga|2004|p=161}} an ], who finishes the artwork in ink;{{sfnm|1a1=Markstein|1y=2010|2a1=Lyga|2a2=Lyga|2y=2004|2p=161|3a1=Lee|3y=1978|3p=145}} a ];{{sfn|Duncan|Smith|2009|p=315}} and a ], who adds the captions and speech balloons.{{sfn|Lyga|Lyga|2004|p=163}} | |||

| By many definitions (including McCloud's, above) the definition of comics extends to ] such as ]s and the ]. | |||

| ===Etymology=== | |||

| The nature of the comics work being created determines the number of people who work upon its creation, with successful ] and ] being produced through a ] system, in which an artist will assemble a team of assistants to help in the creation of the work. However, works from independent companies, ] or those of a more personal nature can be produced by as little as one creator. | |||

| The English-language term ''comics'' derives from the humorous (or "]") work which predominated in early American newspaper comic strips, but usage of the term has become standard for non-humorous works as well. The alternate spelling ''comix'' – coined by the ] movement – is sometimes used to address such ambiguities.{{sfn|Gomez Romero|Dahlman|2012}} The term "comic book" has a similarly confusing history since they are most often not humorous and are periodicals, not regular books.{{sfn|Groensteen|2012|loc=p. 131 (translator's note)}} It is common in English to refer to the comics of different cultures by the terms used in their languages, such as ''{{transl|ja|]}}'' for Japanese comics, or {{lang|fr|bandes dessinées}} for French-language ].{{sfn|McKinney|2011|p=xiii}} | |||

| Within the comic book industry of the United States, the studio system has come to be the main method of creation. Through its use by the industry, the roles have become heavily codified, and the managing of the studio has become the company's responsibility, with an editor discharging the management duties. The editor will assemble a number of creators and oversee the work to publication. | |||

| Many cultures have taken their word for comics from English, including Russian ({{lang|ru|комикс}}, ''{{transl|ru|]}}''){{sfn|Alaniz|2010|p=7}} and German ({{lang|de|]}}).{{sfn|Frahm|2003}} Similarly, the Chinese term ''{{transl|zh|]}}''{{sfnm|1a1=Wong|1y=2002|1p=11|2a1=Cooper-Chen|2y=2010|2p=177}} and the Korean ''{{transl|ko|]}}''{{sfn|Johnson-Woods|2010|p=301}} derive from the ]s with which the Japanese term ''{{transl|ja|manga}}'' is written.{{sfnm|1a1=Cooper-Chen|1y=2010|1p=177|2a1=Thompson|2y=2007|2p=xiii}} | |||

| Any number of people can assist in the creation of a comic book in this way, from a ], a ], a ], an ], a ], a ], and a ], with some roles being performed by the same person. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| In contrast, a comic strip tends to be the work of a sole creator, usually termed a cartoonist. However, it is not unusual for a cartoonist to employ the studio method, particularly when a strip become successful. ] is one such creator who employed a studio, while ] was one such cartoonist who eschewed the studio method, preferring to create the strip himself. Gag, political and editorial cartoonists tend to work alone as well, although again it is not unheard of for a cartoonist to use assistants. | |||

| {{Div col|colwidth=20em}} | |||

| ===Tools=== | |||

| * ] | |||

| An artist uses a variety of pencils, paper, typically ], and a waterproof ]. When inking, an artist may choose to use a variety of ]es, ]s, a ] or a variety of ]s or ]. ] can be employed to add grey ] to an image. An artist might also choose to create his work in paints; either ]; ]; ]s; or ]. Color can also be achieved through crayons, pastels or colored pencils. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Div col end}} | |||

| ], ]s, ]s, ]s and a ] assist in creating lines and shapes. A ] gives a good angled surface to work from, with lamps supplying necessary lighting. A ] allows an artist to trace his pencil work when inking, allowing for a looser finish. ]s and ]s will fill a variety of tasks, including cutting board or scraping mistakes. A ] will assist when cutting paper. Process white is a thick opaque white handy for covering mistakes, while ]s and ]s are helpful in composition where an image may need to be assembled from different sources. | |||

| === |

===See also lists=== | ||

| With the growth of computer processing power and ownership, there are now an increasing number of examples of comic books or strips where the art is made by using computers, either mixing it with hand drawings or replacing hand drawing completely. ] is one artist who combines both paper and the digital methods of composition for comics,<ref>Brayshaw, Christopher (June, 1997) "" '']'' 196.</ref> while in 1998 ] pioneered the use of fully digitised ] artwork on his '']'' comic strip for '']''.<ref>{{cite news|author=BBC Staff|title=Whistle blown on Striker magazine|url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/kent/4549375.stm|date=2005-05-15}}</ref> Computers are also now widely used for both lettering and coloring. | |||

| {{Div col|colwidth=20em}} | |||

| ==In higher education== | |||

| * ] | |||

| A growing number of universities around the world are recognizing the academic legitimacy of comics studies, leading to a greater amount of comics courses being offered at the college level.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2007-12-15-comicsclasses_N.htm |title= Schools add, expand comics arts classes |accessdate=2008-11-11 |last= Cornwell |first= Lisa |coauthors= |date= ] |work= |publisher='']''}}</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Div col end}} | |||

| == |

==Notes== | ||

| {{Comics portal}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| ==Footnotes== | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| <!-- Dead note "1": Arnold, 2001. --> | |||