| Revision as of 11:03, 5 September 2009 editWladthemlat (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,807 edits Reverted 1 edit by Nmate; Rv unexplained reversion. Reverting back to WP:NCGN Pressburg and teh official city nomenclature. (TW)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 19:13, 25 December 2024 edit undoOrionNimrod (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,674 edits Undid revision 1265152626 by Dimadick (talk) he was really not a monarchTag: Undo | ||

| (302 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Eastern name order|Bethlen Gábor}} | |||

| {{unreferenced|date=October 2006}} | |||

| {{more footnotes needed|date=March 2013}} | |||

| {{Infobox Monarch | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| | name = Gabriel Bethlen | | name = Gabriel Bethlen | ||

| | |

| image = Gabor Bethlen-Hungary National Musem.jpg | ||

| | |

| succession = ] | ||

| | |

| reign = 25 August 1620{{spaced ndash}} 31 December 1621 | ||

| | predecessor = ] | |||

| | reign = As ] (1613-1629), As ] (1622-1625) | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | coronation = | |||

| | succession1 = ] | |||

| | full name = | |||

| | reign1 = October 1613{{spaced ndash}} 15 November 1629 | |||

| | predecessor = | |||

| | predecessor1 = ] | |||

| | successor = | |||

| | successor1 = ] | |||

| | consort = | |||

| | |

| succession2 = ] | ||

| | reign2 = 1622{{spaced ndash}} 1625 | |||

| | royal house = Bethlen | |||

| | predecessor2 = ] | |||

| | royal motto = | |||

| | successor2 = ] | |||

| | full name = Gabriel Bethlen de Iktár | |||

| | spouse = ] | |||

| | house = Bethlen | |||

| | house-type = Family | |||

| | father = | | father = | ||

| | mother = | | mother = | ||

| | |

| birth_date = 1580 | ||

| | birth_place = Marosillye, ] (now ], Romania) | |||

| | place of birth = | |||

| | |

| death_date = 15 November 1629 (aged 49) | ||

| | death_place = Gyulafehérvár, Principality of Transylvania (now ], Romania) | |||

| | place of death = | |||

| | |

| religion = ] | ||

| | place of burial = | |||

| | | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Campaignbox Gabriel Bethlen's Revolt}} | |||

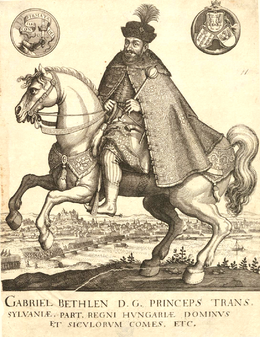

| '''Gabriel Bethlen (de Iktár)''' (-], ]: ''Bethlen Gábor'', ]: ''Gabriel Bethlen'', ]: ''Gabriel Bethlen von Iktár'' ]-], ]) was a prince of ] (1613-1629), duke of ] (1622-1625) and leader of an anti-] insurrection in the Habsburg ]. His last armed intervention in 1626 was part of the ]. He led an active ]-oriented foreign policy. | |||

| '''Gabriel Bethlen''' ({{langx|hu|Bethlen Gábor}}; 1580 – 15 November 1629) was ] from 1613 to 1629 and ] from 1622 to 1625. He was also ] from 1620 to 1621, but he never took control of the whole kingdom. Bethlen, supported by the Ottomans, led his Calvinist principality against the Habsburgs and their Catholic allies. | |||

| Gabriel Bethlen, the most famous representative of the ] branch of the ancient ] Bethlen family, was born at Marosillye (today ] in ]) and educated at Szárhegy (today ] in Romania) at the castle of his uncle ]. Thence he was sent to the court of the Transylvanian Prince ], whom he accompanied on his famous ]n campaign. Subsequently he assisted ] to become Prince of Transylvania in 1605 and remained his chief counsellor. Bethlen also supported Bocskay's successor ] (1608-1613), but the prince became jealous of Bethlen's superior abilities and Bethlen was obliged to take refuge with the Turks of the ]. | |||

| == Early life == | |||

| In 1613, Bethlen led a large army against Prince Báthory, but in the same year Báthory was murdered by two of his officers. Bethlen was placed on the throne by the Ottomans in opposition to the wishes of the Austrian ] emperor, who preferred a prince who would incline more toward ] than toward Turkish ]. On ], ], the ] at Napoca (today ]), confirmed the choice of the Turkish sultan. In 1615, Bethlen was also officially recognized by the ] as the Prince of Transylvania; Bethlen promised in secret that he would help the Habsburgs against the Ottomans. | |||

| Gabriel was the elder of the two sons of Farkas ] and Druzsiána Lázár de Szárhegy.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=11}}{{sfn|Oborni|2012|p=206}} Gabriel was born in his father's estate, Marosillye (now ] in ]), in 1580.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=11}}{{sfn|Oborni|2012|p=206}} Farkas Bethlen was a ] who lost his ancestral estate, Iktár (now ] in Romania), due to the ].{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|pp=698-699}} ], ], granted Marosillye to him and made him captain-general of the principality.{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|p=699}} Druzsiána Lázár was descended from a ] noble family.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=11}}{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|p=699}} Both Farkas Bethlen and his wife died in 1591, leaving their two sons, Gabriel and ], orphaned.{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|p=699}} | |||

| While avoiding the cruelties and excesses of many of his predecessors, Bethlen established a singular variant of patriarchal but sufficiently ] ]. He developed mines and industry and nationalised many branches of Transylvania's foreign trade. His agents bought up many products at fixed prices and sold them abroad at a profit, almost doubling his revenues. He built himself a grand new palace in his capital, Apulum (today ]), kept a sumptuous court, composed hymns, and patronised the arts and learning, especially in connection with his own ] faith. He founded an academy to which he invited any pastor and teacher from Royal Hungary; sent students abroad to the Protestant universities of ], the ], and the Protestant principalities of ];, conferred hereditary nobility on all Protestant pastors; and forbade landlords to prevent their serfs from having their children schooled. | |||

| The brothers were put under the guardianship of their maternal uncle, András Lázár de Szárhegy.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=11}}{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|p=699}} They lived in the ] in Szárhegy in ] (now ] in Romania) for years.{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|p=699}} Gabriel's court historian, Gáspár Bojti Veres, described Lázár as a "grumpy and fierce" soldier who did not care much about their formal education.{{sfn|Oborni|2012|p=206}} | |||

| Other parts of his revenue he devoted toward keeping an efficient standing army of mercenaries, with whose help he conducted an ambitious foreign policy. Keeping peace with the ], he struck out to the north and west. | |||

| According Gabriel's first extant letter (from 1593), ], ], seized the brothers' estates "at the word of many coaxing people" without paying a compensation to them in 1591 or 1592, but a "few primary kinsmen" convinced the prince to offer restitution or other landed property to them.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=11}}{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=860}} Gabriel also mentioned in the letter that he decided to visit the prince's court in Gyulafehérvár (now ] in Romania).{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=861}} | |||

| There were several reasons for his anti-Habsburg interventions in neighbouring Royal Hungary (1619-1626) which took place during Central Europe's ]: | |||

| *He was partly motivated by personal ambition. | |||

| *Habsburg ] in Royal Hungary. | |||

| *The Habsburgs had started a successful ] in Royal Hungary which confiscated properties of local Protestants. Bethlen seems also to have been genuinely anxious to protect Protestant liberties. | |||

| *The Habsburgs had violated the ] of 1606 that put an end to the anti-Habsburg uprising of Bethlen's "predecessor" ]. | |||

| *The Habsburgs had violated the secret agreement with Bethlen of 1615 and prolonged the peace with Ottoman Empire in July 1615, and even entered into an alliance with ], the captain of Upper Hungary (i.e. present-day Slovakia and adjacent territories) against Bethlen. | |||

| == Career == | |||

| ] | |||

| === Beginnings === | |||

| While ] was occupied with the ] rebellion of 1618, Bethlen led his armies into Royal Hungary in August 1619 and occupied the town of ] (Košice) in September, where his Protestant supporters declared him "head" of Hungary and protector of the Protestants. He soon won over the entirety of present-day Slovakia, even securing the capital of Royal Hungary, ] (Bratislava), in October, where the ] even handed over the ] to Bethlen. Bethlen's troops joined with the troops of the Czech and ]n estates (led by Count ]), but they failed to conquer Vienna in November – Bethlen was forced to leave Austria after being attacked by George Druget and Polish mercenaries (]) in Upper Hungary. Although he had conquered most of Royal Hungary, Bethlen was not averse to a peace, nor to a preliminary suspension of hostilities, and negotiations were opened at the conquered towns of ] (Bratislava), Cassovia (]) and Neosolium (]). Initially, they led to nothing because Bethlen insisted on including the Czechs in the peace, but finally a truce was concluded in January 1620 under which Bethlen received 13 counties in the east of Royal Hungary. On ] 1620 the estates elected him ] at the Diet in Neosolium with the consent of the Ottomans, but Bethlen refused to accept the crown because he wanted to reconcile with the Habsburgs and reunite Hungary. However, the war with the Habsburgs resumed in Royal Hungary and ] in September. | |||

| ] | |||

| The defeat of the ] rebels by Ferdinand II’s troops at the ] on ] ] (to which Bethlen had sent 3,000 delayed troops which however came too late) gave a new turn to Bethlen’s insurrection against the Habsburgs. Ferdinand II took a fearful revenge upon the Protestant nobility in Bohemia and reconquered Royal Hungary (Pressburg reconquered in May 1621, central part of the country with the mining towns in June 1621). Because the Protestant nobles had not received the confiscated property of the Catholics on Bethlen's territory and thus rescinded their support for Bethlen, and because Bethlen was not directly supported by the Ottomans, Bethlen started peace negotiations. As a result, the ] was concluded on ], ], under which Bethlen renounced the royal title on condition that Ferdinand confirmed the 1606 Peace of Vienna (which had granted full liberty of worship to the Hungarian ]) and engaged to summon a general diet within six months). The treaty granted full liberty of worship to the Protestants of Hungarian Transylvania and agreed on the summoning of a general diet within six months. In addition, Bethlen secured the (purely formal) title of “Imperial Prince“ (of Hungarian Transylvania), seven counties around the Upper ] River (in present-day Slovakia, Ukraine, Hungary and Romania), the fortresses of ], ], and ], and a duchy in ]. | |||

| Modern historians try to reconstruct the major events of Gabriel's youth based on sources (primarily memoirs and letters) completed decades later, because only two documents written between 1593 and 1602 mentioned him.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|pp=861, 863}} One of the later sources is Gabriel's own letter from 1628, in which he stated that ] had raised him and "placed great credence" in him.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=864}} Gabriel also stated that Bocskai was his "kin".{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=864}} Another important source was written by Gabriel's retainer, Pál Háportoni Forró, who stated that Gabriel had held "great and honorable offices" and performed "the greatly laborious duties of emissary" in his youth.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=864}} Based on these sources, modern historians assume that Bocskai boosted Gabriel's career in Sigismund Báthory's court,{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=12}}{{sfn|Oborni|2012|p=206}} but no contemporaneous document mentioned his presence in the prince's retinue.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=861}} | |||

| Subsequently Bethlen twice (1623-1624 and 1626) launched further campaigns against Ferdinand to the territory of Hungarian Highlands present-day Slovakia, this time as a direct ally of the anti-Habsburg Protestant powers. The first war was concluded by the 1624 Peace of Vienna, the second by the 1626 ]- both confirmed the 1621 Peace of Nikolsburg. After the second of these campaigns, Bethlen attempted a rapprochement with the court of Vienna on the basis of an alliance against the Turks and his own marriage with an archduchess of Austria, but Ferdinand rejected his overtures. Bethlen was obliged to renounce his anti-Turkish projects, which had always remained a goal of his. Accordingly, on his return from Vienna he wedded Catherine, the daughter of the elector of ], and still more closely allied himself with the Protestant powers, including his brother-in-law ] of ], who, he hoped, would aid him in obtaining the ] crown. Bethlen died on ], ] before he could accomplish any of his great designs to Unite Transylvania and Hungary, having previously secured the election of his wife Catherine as princess. His first wife, Zsuzsanna Károlyi, died in 1622. | |||

| Sigismund Báthory joined the anti-Ottoman ] and broke into Ottoman territory in the summer of 1595.{{sfn|Keul|2009|p=141}} According to historian József Barcza, Gabriel gained his first direct experience of warfare fighting against the Ottomans in the ] in ] in 1595.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=17}} After a series of Ottoman victories, Báthory abdicated in return for the ] of ] and ] in 1597, enabling the commissioners of the ], ] (who was also king of ]) to take possession of Transylvania.{{sfn|Barta|1994|p=295}}{{sfn|Kontler|1999|p=164}} | |||

| ] banknote: Gabriel Bethlen in the company of Trasilvanian scientists]] | |||

| === Anarchy === | |||

| Gabriel Bethlen was one of the most striking and original personages of his century. A zealous ] who boasted he had read the Bible twenty-five times, he was not a bigot and had helped the ] ] to translate and print his version of the ]. He was in communication all his life with the leading contemporary statesmen, so that his correspondence is one of the most interesting and important of historical documents. He also composed hymns. | |||

| Sigismund Báthory regretted his abdication and returned to Transylvania in August 1598.{{sfn|Keul|2009|p=142}}{{sfn|Barta|1994|p=295}} He sent Bocskai to Prague to start negotiations with Rudolph in January 1599.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=17}} According to a scholarly theory, Gabriel Bethlen accompanied Bocskai to Prague.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=17}}{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=862}} Historian József Barcza also says, Gabriel must have realized around that time that the ] monarchs were unable to defend Transylvania against the Ottomans.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=17}} Gabriel himself stated that he visited Prague in the retinue of Sigismund Báthory at an unspecified date.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=862}} | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| Gabriel supported ],{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} who mounted the throne with Polish assistance after Sigismund again abdicated in 1599.{{sfn|Kontler|1999|p=164}} ], Prince of Wallachia, broke into Transylvania and defeated Andrew in the ] (at present-day ] in Romania) on 8 October 1599.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} Gabriel received wounds in the battle and his wounds healed slowly.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} Michael the Brave was expelled from Transylvania by Rudolph's commander, ].{{sfn|Keul|2009|p=143}} During the following years, Transylvania was regularly pillaged both by Basta's unpaid mercenaries, and by Ottoman and ] troops.{{sfn|Keul|2009|p=143}}{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} Gabriel and his brother, Stephen, divided their inherited estates, with Gabriel receiving Marosillye.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=861}} Their agreement also refers to the anarchic situation, mentioning the possibility that "either pagan or some godless prince or the governor" would seize Gabriel's property.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=861}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Commonscat|Gábor Bethlen|Gabriel Bethlen}} | |||

| Gabriel joined the Transylvanian noblemen who rose up against Basta.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} Sigismund Báthory (who had again returned to Transylvania) granted Gabriel and his brother landed property in ] in June 1602.{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=862}} The army of the rebellious noblemen was annihilated near Tövis (now ] in Romania) on 2 July 1602.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}}{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=862}} After the battle, he swam over the ] and fled to Temesvár in the Ottoman Empire (now ] in Romania).{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}}{{sfn|Erdősi|Lambert|2013|p=862}} He forged letters which suggested that the leading Transylvanian noblemen supported ] to persuade the Ottomans to support Székely, according to the contemporaneous ].{{sfn|G. Etényi|Horn|Szabó|2006|p=162}} When Székely broke into Transylvania in March 1603, Gabriel was the commander of his vanguard.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} Székelys' troops conquered most fortresses along the Maros and laid siege to Gyulafehérvár. During the siege, the princely palace burned.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}}{{sfn|R. Várkonyi|Campbell|2013|p=700}} Székely was installed as prince in May, but ], Prince of Wallachia, annihilated his army near Barcarozsnyó (now ] in Romania) on 17 July.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}}{{sfn|Keul|2009|p=150}} Székely was killed in the battlefield, and his supporters (among them Gabriel) fled to the Ottoman Empire.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=18}} | |||

| {{start}} | |||

| {{s-hou|]}} | |||

| The Transylvanian refugees started to regard Gabriel as their leader.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=20}} They sent a delegation to ] in August, asking the permission of the ] to elect Gabriel prince and seeking Ottoman assistance to their return to Transylvania.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=20}} The grand vizier granted the permission, but one of the refugees, Boldizsár Szilvási, prevented Gabriel's election, pointing out that a prince could not be elected by a group of refugees, but by the Diet of Transylvania.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=20}} | |||

| === Bocskai's supporter === | |||

| Gabriel decided to persuade the wealthy Stephen Bocskai to rise up against Rudolph's commissioners.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=21}} After royal troops attacked the refugees' camp near Temesvár on 13 September 1604, rumours about the capture of a secret correspondence between Bethlen and Bocskai began circulating.{{sfn|G. Etényi|Horn|Szabó|2006|p=162}} Fearing reprisals, Bocskai withdrew to his fortress at Sólyomkő (now Şoimeni in Romania) and make preparations to resist.{{sfn|G. Etényi|Horn|Szabó|2006|p=162}} He hired irregular ] troops and defeated a royal army on 15 October.{{sfn|G. Etényi|Horn|Szabó|2006|pp=167-169}}{{sfn|Barta|1994|p=298}} | |||

| Bocskai took possession of Kassa (now ] in Slovakia) on 11 November.{{sfn|Barta|1994|p=298}} Soon after, Gabriel gave the '']'' (or charter) in which the ], ], styled Bocskai as prince of Transylvania.{{sfn|Barta|1994|p=298}} The delegates of the noblemen and the ] elected Bocskai prince on 21 February 1605.{{sfn|G. Etényi|Horn|Szabó|2006|p=191}} According to a letter of Bethlen, Bocskai ordered him to capture "certain castles", for which he had to postpone his marriage in May.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=21}} | |||

| Gabriel finally married his bride, Zsuzsanna ], in August 1605.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=21}} Bocskai granted the domain of Vajdahunyad (now ] in Romania) to him.{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=21}} The prince also made him the ] (or head) of ].{{sfn|Barcza|1987|p=21}} | |||

| Bethlen was a ]. He helped ], a ], translate and print the ]. He composed hymns and from 1625, employed ] as kapellmeister. | |||

| === Prince of Transylvania === | |||

| {{See also|Principality of Transylvania (1570–1711)}} | |||

| {{Css Image Crop|Image = Transylvania 1616 10 Ducat gold coin.jpg|bSize = 410|cWidth = 200|cHeight = 200|oTop = 5|oLeft = 3|Location = left||Description =1616 ten-] gold coin depicting Gabriel Bethlen as ]}} | |||

| In 1605, Bethlen supported ] and his successor ] (1608–1613). Bethlen later fell out with Báthory and fled to the ]. | |||

| In 1613, after Báthory was murdered, the Ottomans installed Bethlen as ] and this was endorsed on 13 October 1613 by the ] at Kolozsvár (]). In 1615, after the ], Bethlen was recognised by ].<ref>Varkonyi A. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220506120944/http://www.matud.iif.hu/2013/10/08.htm |date=2022-05-06 }} Magyar Tudomány October 2013. Accessed 15 October 2013. In Hungarian.</ref> | |||

| Bethlen's rule was one of ]. He developed mines and industry and nationalised many branches of Transylvania's foreign trade. His agents bought goods at fixed prices and sold them abroad at profit. In his capital, in Gyulafehérvár (]), Bethlen built a grand new palace. Bethlen was a patron of the arts and the ] church, giving hereditary nobility to Protestant priests. Bethlen also encouraged learning by founding the ], encouraging the enrollment of Hungarian academics and teachers and sending Transylvanian students to the Protestant universities of ], the ], and the Protestant principalities of ]. He also ensured the right of serfs' children to be educated. | |||

| === Anti-Habsburg insurrection === | |||

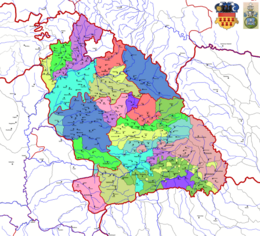

| ], ], ], ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| Bethlen maintained an efficient standing army of mercenaries. While keeping relations with the ] (the Ottoman Empire), he sought to gain lands to the north and west. During the ], he attacked the Habsburgs of Royal Hungary (1619–1626). Bethlen opposed the ] of the Habsburgs; persecution of Protestants in Royal Hungary; the violation of the ] of 1606; and Habsburg alliances with the Ottomans and George ] (1633-1661), the captain of ]. | |||

| In August 1619, Bethlen invaded Royal Hungary. In September, he took Kassa (]) where Protestant supporters declared him the leader of Hungary and protector of Protestants. He gained control of Upper Hungary (present-day Slovakia). In September 1619, after refusing to convert to Calvinism, the Jesuits ], ] and ] were martyred under Bethlen's authority."<ref>Barti J. Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, p. 66, 2002. {{ISBN|0865164444|9780865164444}}.</ref> The three were later canonized by the Catholic Church. | |||

| In October 1619, Bethlen took Pressburg (Pozsony, today's ]), where the ] ceded the ]. However, Bethlen, together with ], count of the Moravian and Czech estates, did not take Vienna and, in November, the forces of George Drugeth and Polish mercenaries (]) won the ] and forced Bethlen to leave Austria and Upper Hungary. | |||

| Bethlen negotiated for peace at Pressburg, Kassa (now ]) and Besztercebánya (now ]). In January 1620, without the Czechs, Bethlen received 13 counties in the east of Royal Hungary. On 20 August 1620, he was elected ] at the Diet of Besztercebánya and in September 1620, war with the Habsburgs resumed. | |||

| After defeating the Czechs on 8 November 1620 at the ], Ferdinand II persecuted the Protestant nobility of Bohemia. Between May and June 1621, he regained Pressburg and the central mining towns. Bethlen again sued for peace and on 31 December 1621, the ] was made. Bethlen renounced his royal title on the condition that Hungarian Protestants were given religious freedoms and were included in a general diet within six months. Bethlen was given the title of ''Imperial Prince'' (of Hungarian Transylvania), seven counties around the Upper ] River and the fortresses of ], ] (now ]), and Ecsed (]), and a duchy in ]. | |||

| ] of Gabriel Bethlen showing his portrait and coat of arms (1621)]] | |||

| In 1623 - 1624 and 1626, Bethlen, allied with the anti-Habsburg Protestants, made campaigns against Ferdinand in Upper Hungary. The first campaign ended with the ], the second by the ]. After the second campaign, Bethlen offered as rapprochement to the court of Vienna an alliance against the Ottomans and his marriage to an archduchess of Austria, but Ferdinand rejected his overtures. On his return from Vienna, Bethlen wed ], the daughter of ]. His brother-in-law was ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| == Death == | |||

| ] | |||

| Bethlen died on 15 November 1629. His second wife, Catherine of Brandenburg, became Princess Regnant of Transylvania. | |||

| His first wife, {{ill|Zsuzsanna Károlyi|hu|Károlyi Zsuzsanna}}, had died in 1622. | |||

| Bethlen's state correspondence survives as a historical document. | |||

| {{-}} | |||

| ==Ancestors== | |||

| {{ahnentafel | |||

| |collapsed=yes |align=center | |||

| |boxstyle_1=background-color: #fcc; | |||

| |boxstyle_2=background-color: #fb9; | |||

| |boxstyle_3=background-color: #ffc; | |||

| |boxstyle_4=background-color: #bfc; | |||

| |boxstyle_5=background-color: #9fe; | |||

| |1= 1. '''Gabriel Bethlen de Iktár'''<ref></ref> | |||

| |2= 2. Farkas Bethlen de Iktár (+1590)<ref></ref> | |||

| |3= 3. Druzsianna Lázár de Szárhegy<ref></ref> | |||

| |4= 4. Gabriel Bethlen de Iktár | |||

| |5= 5. ''unknown woman from the'' Kinizsi ''family'' | |||

| |6= 6. Stephen Lázár de Szárhegy<ref></ref> | |||

| |7= 7. Borbála Bogáthy de Bogáth<ref></ref> | |||

| |8= 8. Peter Bethlen de Iktár | |||

| |12= 12. János Lázár de Szentanna | |||

| |13= 13. Klára Apafi de Apanagyfalu | |||

| |14= 14. János Bogáthy de Bogáth<ref></ref> | |||

| |15= 15. Magdolna Bánffy de Losoncz (+1545)<ref></ref> | |||

| |16= 16. Domokos Bethlen de Iktár | |||

| |17= 17. Christina ''(from unknown family)'' | |||

| |24= 24. András Lázár de Szárhegy | |||

| |26= 26. György Apafi de Apanagyfalu<ref></ref> | |||

| |27= 27. Anna Bánffy de Losoncz | |||

| |28= 28. András Bogáthy de Bogáth | |||

| |30= 30. László Bánffy de Losoncz<ref></ref> | |||

| |31= 31. Anna Dobokai | |||

| }} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| === Citations === | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| === Sources === | |||

| {{refbegin}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Barcza |first=József |year=1987 |title = Bethlen Gábor, a református fejedelem |language = hu |trans-title = Gabriel Bethlen, the Reformed Prince |publisher=Magyarországi Református Egyház Sajtóosztálya |location=Budapest |isbn=963300246X }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Barta |first=Gábor |editor1-last=Köpeczi |editor1-first=Béla |editor2-last=Barta |editor2-first=Gábor |editor3-last=Bóna |editor3-first=István |editor4-last=Makkai |editor4-first=László |editor5-last=Szász |editor5-first=Zoltán |editor6-last=Borus |editor6-first=Judit | title=History of Transylvania |edition=English |volume=pt. 3. The Principality of Transylvania |publisher=Akadémiai Kiadó |location=Budapest |year=1994 |pages=247–300 |chapter=The Emergence of the Principality and its First Crises (1526–1606) |isbn=9630567032 }} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Erdősi |first1=Péter |last2=Lambert |first2=Sean |title = The Theme of Youth and Court Life in Historical Literature Regarding Gábor Bethlen and Zsigmond Báthory |journal=The Hungarian Historical Review |volume=2 |number=4 |pages=856–879 |publisher=MTA Történettudományi Intézet |year=2013 |jstor=43264470 |issn=2063-8647 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=G. Etényi |first1=Nóra |last2=Horn |first2=Ildikó |last3=Szabó |first3=Péter |year=2006 |title=Koronás fejedelem: Bocskai István és kora |trans-title = A Crowned Prince: Stephen Bocskai and his Time |publisher=General Press Kiadó |location=Budapest |language=hu |isbn=963-9648-27-2 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Keul |first=István |year=2009 |title=Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691) |publisher=Brill Academic Publishers |isbn=978-90-04-17652-2 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Kontler |first=László |year=1999 |title=Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary |publisher=Atlantisz Publishing House |location=Budapest |isbn=963-9165-37-9 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Oborni |first=Teréz |editor1-last=Gujdár |editor1-first=Noémi |editor2-last=Szatmáry |editor2-first=Nóra |title=Magyar királyok nagykönyve: Uralkodóink, kormányzóink és az erdélyi fejedelmek életének és tetteinek képes története |trans-title=Encyclopedia of the Kings of Hungary: An Illustrated History of the Life and Deeds of Our Monarchs, Regents and the Princes of Transylvania |publisher=Reader's Digest |location=Budapest |year=2012 |pages=206–209 |chapter=Bethlen Gábor |isbn=978-963-289-214-6 |language=hu }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Péter |first=Katalin |editor1-last=Köpeczi |editor1-first=Béla |editor2-last=Barta |editor2-first=Gábor |editor3-last=Bóna |editor3-first=István |editor4-last=Makkai |editor4-first=László |editor5-last=Szász |editor5-first=Zoltán |editor6-last=Borus |editor6-first=Judit |title = History of Transylvania |publisher=Akadémiai Kiadó |location=Budapest |year=1994 |pages=301–358 |chapter=The Golden Age of the Principality (1606–1660) |isbn=963-05-6703-2 }} | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=R. Várkonyi |first1=Ágnes |last2=Campbell |first2=Alan |title = Gábor Bethlen and His European Presence |journal=The Hungarian Historical Review |volume=2 |number=4 |pages=695–732 |publisher=MTA Történettudományi Intézet |year=2013 |jstor=43264465 |issn=2063-8647 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Settonv |first=Kenneth |author-link=Kenneth Setton |title = Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=XN51y209fR8C&pg=PA34 |year=1991 |publisher=American Philosophical Society |location=Philadelphia, PA |isbn=978-0-87169-192-7 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Sturdy |first=David J. |title=Fractured Europe: 1600 - 1721 |url = https://books.google.com/books?id=Y8_mapl_JS0C&pg=PA45 |date=2002-02-01 |series=Blackwell History of Europe series |publisher=Blackwell |location=Oxford, England |isbn = 978-0-631-20513-5 }} | |||

| {{refend}} | |||

| == External links == | |||

| * {{commonscatinline}} | |||

| * {{Cite Americana|wstitle=Bethlen-Gabor |short=x |year=1920}} | |||

| * {{cite EB1911|wstitle=Bethlen, Gabriel|volume=3|last= Bain |first= Robert Nisbet |author-link= Robert Nisbet Bain|pages=829-830|short= 1}} | |||

| * | |||

| {{s-start}} | |||

| {{s-hou|]}} | |||

| {{s-reg|}} | {{s-reg|}} | ||

| {{s-bef|before=]}} | {{s-bef|before=]}} | ||

| {{s-ttl|title=]|years= |

{{s-ttl|title=]|years=1613–1629}} | ||

| {{s-aft|after=]}} | {{s-aft|after=]}} | ||

| {{Succession box| | |||

| {{s-bef|before=] Duke until 1598 }} | |||

| title=]<br><small>contested by ]</small>| | |||

| {{s-ttl|title=]|years=1622-1625}} | |||

| before=]| | |||

| {{s-aft|after=] Duke from 1645}} | |||

| after=]| | |||

| years=1620–1621 | |||

| }} | |||

| {{s-bef|before=]}} | |||

| {{s-ttl|title=]|years=1622–1625}} | |||

| {{s-aft|after=]}} | |||

| {{s-end}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Bethlen, Gabriel}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Bethlen, Gabriel}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 19:13, 25 December 2024

The native form of this personal name is Bethlen Gábor. This article uses Western name order when mentioning individuals.| This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. Please help to improve this article by introducing more precise citations. (March 2013) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

| Gabriel Bethlen | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| King of Hungary | |||||

| Reign | 25 August 1620 – 31 December 1621 | ||||

| Predecessor | Matthias II | ||||

| Successor | Ferdinand II | ||||

| Prince of Transylvania | |||||

| Reign | October 1613 – 15 November 1629 | ||||

| Predecessor | Gabriel Báthory | ||||

| Successor | Catherine | ||||

| Duke of Opole | |||||

| Reign | 1622 – 1625 | ||||

| Predecessor | Sigismund Báthory | ||||

| Successor | Władysław Vasa | ||||

| Born | 1580 Marosillye, Principality of Transylvania (now Ilia, Romania) | ||||

| Died | 15 November 1629 (aged 49) Gyulafehérvár, Principality of Transylvania (now Alba Iulia, Romania) | ||||

| Spouse | Catherine of Brandenburg | ||||

| |||||

| Family | Bethlen | ||||

| Religion | Calvinist | ||||

| Gabriel Bethlen's Revolt | |

|---|---|

Gabriel Bethlen (Hungarian: Bethlen Gábor; 1580 – 15 November 1629) was Prince of Transylvania from 1613 to 1629 and Duke of Opole from 1622 to 1625. He was also King-elect of Hungary from 1620 to 1621, but he never took control of the whole kingdom. Bethlen, supported by the Ottomans, led his Calvinist principality against the Habsburgs and their Catholic allies.

Early life

Gabriel was the elder of the two sons of Farkas Bethlen de Iktár and Druzsiána Lázár de Szárhegy. Gabriel was born in his father's estate, Marosillye (now Ilia in Romania), in 1580. Farkas Bethlen was a Hungarian nobleman who lost his ancestral estate, Iktár (now Ictar-Budinț in Romania), due to the Ottoman occupation of the central territories of the Kingdom of Hungary. Stephen Báthory, Prince of Transylvania, granted Marosillye to him and made him captain-general of the principality. Druzsiána Lázár was descended from a Székely noble family. Both Farkas Bethlen and his wife died in 1591, leaving their two sons, Gabriel and Stephen, orphaned.

The brothers were put under the guardianship of their maternal uncle, András Lázár de Szárhegy. They lived in the Lázár Castle in Szárhegy in Székely Land (now Lăzarea in Romania) for years. Gabriel's court historian, Gáspár Bojti Veres, described Lázár as a "grumpy and fierce" soldier who did not care much about their formal education.

According Gabriel's first extant letter (from 1593), Sigismund Báthory, Prince of Transylvania, seized the brothers' estates "at the word of many coaxing people" without paying a compensation to them in 1591 or 1592, but a "few primary kinsmen" convinced the prince to offer restitution or other landed property to them. Gabriel also mentioned in the letter that he decided to visit the prince's court in Gyulafehérvár (now Alba Iulia in Romania).

Career

Beginnings

Modern historians try to reconstruct the major events of Gabriel's youth based on sources (primarily memoirs and letters) completed decades later, because only two documents written between 1593 and 1602 mentioned him. One of the later sources is Gabriel's own letter from 1628, in which he stated that Stephen Bocskai had raised him and "placed great credence" in him. Gabriel also stated that Bocskai was his "kin". Another important source was written by Gabriel's retainer, Pál Háportoni Forró, who stated that Gabriel had held "great and honorable offices" and performed "the greatly laborious duties of emissary" in his youth. Based on these sources, modern historians assume that Bocskai boosted Gabriel's career in Sigismund Báthory's court, but no contemporaneous document mentioned his presence in the prince's retinue.

Sigismund Báthory joined the anti-Ottoman Holy League of Pope Clement VIII and broke into Ottoman territory in the summer of 1595. According to historian József Barcza, Gabriel gained his first direct experience of warfare fighting against the Ottomans in the Battle of Giurgiu in Wallachia in 1595. After a series of Ottoman victories, Báthory abdicated in return for the Silesian duchies of Opole and Racibórz in 1597, enabling the commissioners of the Holy Roman Emperor, Rudolph (who was also king of Royal Hungary) to take possession of Transylvania.

Anarchy

Sigismund Báthory regretted his abdication and returned to Transylvania in August 1598. He sent Bocskai to Prague to start negotiations with Rudolph in January 1599. According to a scholarly theory, Gabriel Bethlen accompanied Bocskai to Prague. Historian József Barcza also says, Gabriel must have realized around that time that the Habsburg monarchs were unable to defend Transylvania against the Ottomans. Gabriel himself stated that he visited Prague in the retinue of Sigismund Báthory at an unspecified date.

Gabriel supported Andrew Báthory, who mounted the throne with Polish assistance after Sigismund again abdicated in 1599. Michael the Brave, Prince of Wallachia, broke into Transylvania and defeated Andrew in the Battle of Sellenberk (at present-day Șelimbăr in Romania) on 8 October 1599. Gabriel received wounds in the battle and his wounds healed slowly. Michael the Brave was expelled from Transylvania by Rudolph's commander, Giorgio Basta. During the following years, Transylvania was regularly pillaged both by Basta's unpaid mercenaries, and by Ottoman and Crimean Tatar troops. Gabriel and his brother, Stephen, divided their inherited estates, with Gabriel receiving Marosillye. Their agreement also refers to the anarchic situation, mentioning the possibility that "either pagan or some godless prince or the governor" would seize Gabriel's property.

Gabriel joined the Transylvanian noblemen who rose up against Basta. Sigismund Báthory (who had again returned to Transylvania) granted Gabriel and his brother landed property in Arad County in June 1602. The army of the rebellious noblemen was annihilated near Tövis (now Teiuș in Romania) on 2 July 1602. After the battle, he swam over the Maros River and fled to Temesvár in the Ottoman Empire (now Timișoara in Romania). He forged letters which suggested that the leading Transylvanian noblemen supported Moses Székely to persuade the Ottomans to support Székely, according to the contemporaneous Ambrus Somogyi. When Székely broke into Transylvania in March 1603, Gabriel was the commander of his vanguard. Székelys' troops conquered most fortresses along the Maros and laid siege to Gyulafehérvár. During the siege, the princely palace burned. Székely was installed as prince in May, but Radu Șerban, Prince of Wallachia, annihilated his army near Barcarozsnyó (now Râșnov in Romania) on 17 July. Székely was killed in the battlefield, and his supporters (among them Gabriel) fled to the Ottoman Empire.

The Transylvanian refugees started to regard Gabriel as their leader. They sent a delegation to Constantinople in August, asking the permission of the Ottoman grand vizier to elect Gabriel prince and seeking Ottoman assistance to their return to Transylvania. The grand vizier granted the permission, but one of the refugees, Boldizsár Szilvási, prevented Gabriel's election, pointing out that a prince could not be elected by a group of refugees, but by the Diet of Transylvania.

Bocskai's supporter

Gabriel decided to persuade the wealthy Stephen Bocskai to rise up against Rudolph's commissioners. After royal troops attacked the refugees' camp near Temesvár on 13 September 1604, rumours about the capture of a secret correspondence between Bethlen and Bocskai began circulating. Fearing reprisals, Bocskai withdrew to his fortress at Sólyomkő (now Şoimeni in Romania) and make preparations to resist. He hired irregular Hajdú troops and defeated a royal army on 15 October.

Bocskai took possession of Kassa (now Košice in Slovakia) on 11 November. Soon after, Gabriel gave the ahidnâme (or charter) in which the Ottoman Sultan, Ahmed I, styled Bocskai as prince of Transylvania. The delegates of the noblemen and the Székelys elected Bocskai prince on 21 February 1605. According to a letter of Bethlen, Bocskai ordered him to capture "certain castles", for which he had to postpone his marriage in May.

Gabriel finally married his bride, Zsuzsanna Károlyi, in August 1605. Bocskai granted the domain of Vajdahunyad (now Hunedoara in Romania) to him. The prince also made him the perpetual ispán (or head) of Hunyad County.

Bethlen was a Calvinist. He helped György Káldy, a Jesuit, translate and print the Bible. He composed hymns and from 1625, employed Johannes Thesselius as kapellmeister.

Prince of Transylvania

See also: Principality of Transylvania (1570–1711) 1616 ten-ducat gold coin depicting Gabriel Bethlen as Prince of Transylvania

1616 ten-ducat gold coin depicting Gabriel Bethlen as Prince of Transylvania

In 1605, Bethlen supported Stephen Bocskay and his successor Gabriel Báthory (1608–1613). Bethlen later fell out with Báthory and fled to the Ottoman Empire.

In 1613, after Báthory was murdered, the Ottomans installed Bethlen as Prince of Transylvania and this was endorsed on 13 October 1613 by the Transylvanian Diet at Kolozsvár (Cluj-Napoca). In 1615, after the Peace of Tyrnau, Bethlen was recognised by Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor.

Bethlen's rule was one of enlightened absolutism. He developed mines and industry and nationalised many branches of Transylvania's foreign trade. His agents bought goods at fixed prices and sold them abroad at profit. In his capital, in Gyulafehérvár (Alba Iulia), Bethlen built a grand new palace. Bethlen was a patron of the arts and the Calvinist church, giving hereditary nobility to Protestant priests. Bethlen also encouraged learning by founding the Bethlen Gabor College, encouraging the enrollment of Hungarian academics and teachers and sending Transylvanian students to the Protestant universities of England, the Dutch Republic, and the Protestant principalities of Germany. He also ensured the right of serfs' children to be educated.

Anti-Habsburg insurrection

Bethlen maintained an efficient standing army of mercenaries. While keeping relations with the Sublime Porte (the Ottoman Empire), he sought to gain lands to the north and west. During the Thirty Years' War, he attacked the Habsburgs of Royal Hungary (1619–1626). Bethlen opposed the autocracy of the Habsburgs; persecution of Protestants in Royal Hungary; the violation of the Peace of Vienna of 1606; and Habsburg alliances with the Ottomans and George Drugeth (1633-1661), the captain of Upper Hungary.

In August 1619, Bethlen invaded Royal Hungary. In September, he took Kassa (Košice) where Protestant supporters declared him the leader of Hungary and protector of Protestants. He gained control of Upper Hungary (present-day Slovakia). In September 1619, after refusing to convert to Calvinism, the Jesuits Marko Križevcanin, Stephen Pongracz and Melchior Grodeczki were martyred under Bethlen's authority." The three were later canonized by the Catholic Church.

In October 1619, Bethlen took Pressburg (Pozsony, today's Bratislava), where the Palatine of Hungary ceded the Holy Crown of Hungary. However, Bethlen, together with Jindřich Matyáš of Thurn-Valsassina, count of the Moravian and Czech estates, did not take Vienna and, in November, the forces of George Drugeth and Polish mercenaries (lisowczycy) won the Battle of Humenné and forced Bethlen to leave Austria and Upper Hungary.

Bethlen negotiated for peace at Pressburg, Kassa (now Košice) and Besztercebánya (now Banská Bystrica). In January 1620, without the Czechs, Bethlen received 13 counties in the east of Royal Hungary. On 20 August 1620, he was elected King of Hungary at the Diet of Besztercebánya and in September 1620, war with the Habsburgs resumed.

After defeating the Czechs on 8 November 1620 at the Battle of White Mountain, Ferdinand II persecuted the Protestant nobility of Bohemia. Between May and June 1621, he regained Pressburg and the central mining towns. Bethlen again sued for peace and on 31 December 1621, the Peace of Nikolsburg was made. Bethlen renounced his royal title on the condition that Hungarian Protestants were given religious freedoms and were included in a general diet within six months. Bethlen was given the title of Imperial Prince (of Hungarian Transylvania), seven counties around the Upper Tisza River and the fortresses of Tokaj, Munkács (now Mukacheve), and Ecsed (Nagyecsed), and a duchy in Silesia.

In 1623 - 1624 and 1626, Bethlen, allied with the anti-Habsburg Protestants, made campaigns against Ferdinand in Upper Hungary. The first campaign ended with the Peace of Vienna (1624), the second by the Peace of Pressburg (1626). After the second campaign, Bethlen offered as rapprochement to the court of Vienna an alliance against the Ottomans and his marriage to an archduchess of Austria, but Ferdinand rejected his overtures. On his return from Vienna, Bethlen wed Catherine of Brandenburg, the daughter of John Sigismund, Elector of Brandenburg. His brother-in-law was Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden.

Death

Bethlen died on 15 November 1629. His second wife, Catherine of Brandenburg, became Princess Regnant of Transylvania.

His first wife, Zsuzsanna Károlyi [hu], had died in 1622.

Bethlen's state correspondence survives as a historical document.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Gabriel Bethlen | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Barcza 1987, p. 11.

- ^ Oborni 2012, p. 206.

- R. Várkonyi & Campbell 2013, pp. 698–699.

- ^ R. Várkonyi & Campbell 2013, p. 699.

- Erdősi & Lambert 2013, p. 860.

- ^ Erdősi & Lambert 2013, p. 861.

- Erdősi & Lambert 2013, pp. 861, 863.

- ^ Erdősi & Lambert 2013, p. 864.

- Barcza 1987, p. 12.

- Keul 2009, p. 141.

- ^ Barcza 1987, p. 17.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 295.

- ^ Kontler 1999, p. 164.

- Keul 2009, p. 142.

- ^ Erdősi & Lambert 2013, p. 862.

- ^ Barcza 1987, p. 18.

- ^ Keul 2009, p. 143.

- ^ G. Etényi, Horn & Szabó 2006, p. 162.

- R. Várkonyi & Campbell 2013, p. 700.

- Keul 2009, p. 150.

- ^ Barcza 1987, p. 20.

- ^ Barcza 1987, p. 21.

- G. Etényi, Horn & Szabó 2006, pp. 167–169.

- ^ Barta 1994, p. 298.

- G. Etényi, Horn & Szabó 2006, p. 191.

- Varkonyi A. Az Europai jelenlet alternativai, Bethlen Gabor fejedelemme valasztasanak evfordulojara." Archived 2022-05-06 at the Wayback Machine Magyar Tudomány October 2013. Accessed 15 October 2013. In Hungarian.

- Barti J. "Slovak History: Chronology & Lexicon." Bolchazy-Carducci Publishers, p. 66, 2002. ISBN 0865164444, 9780865164444.

- Gábor Bethlen in the Bethlen de Iktár family

- Farkas Bethlen in the Bethlen de Iktár family

- Druzsianna Lázár in the Lázár family

- Stephen Lázár in the Lázár family

- Borbála Bogáth in the Bogáthy family

- János Bogáth in the Bogáthy family

- Magdolna Bánffy in the Bánffy de Losoncz family

- Apafi family

- László Bánffy in the Bánffy de Losoncz family

Sources

- Barcza, József (1987). Bethlen Gábor, a református fejedelem [Gabriel Bethlen, the Reformed Prince] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Magyarországi Református Egyház Sajtóosztálya. ISBN 963300246X.

- Barta, Gábor (1994). "The Emergence of the Principality and its First Crises (1526–1606)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Vol. pt. 3. The Principality of Transylvania (English ed.). Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 247–300. ISBN 9630567032.

- Erdősi, Péter; Lambert, Sean (2013). "The Theme of Youth and Court Life in Historical Literature Regarding Gábor Bethlen and Zsigmond Báthory". The Hungarian Historical Review. 2 (4). MTA Történettudományi Intézet: 856–879. ISSN 2063-8647. JSTOR 43264470.

- G. Etényi, Nóra; Horn, Ildikó; Szabó, Péter (2006). Koronás fejedelem: Bocskai István és kora [A Crowned Prince: Stephen Bocskai and his Time] (in Hungarian). Budapest: General Press Kiadó. ISBN 963-9648-27-2.

- Keul, István (2009). Early Modern Religious Communities in East-Central Europe: Ethnic Diversity, Denominational Plurality, and Corporative Politics in the Principality of Transylvania (1526–1691). Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 978-90-04-17652-2.

- Kontler, László (1999). Millennium in Central Europe: A History of Hungary. Budapest: Atlantisz Publishing House. ISBN 963-9165-37-9.

- Oborni, Teréz (2012). "Bethlen Gábor". In Gujdár, Noémi; Szatmáry, Nóra (eds.). Magyar királyok nagykönyve: Uralkodóink, kormányzóink és az erdélyi fejedelmek életének és tetteinek képes története [Encyclopedia of the Kings of Hungary: An Illustrated History of the Life and Deeds of Our Monarchs, Regents and the Princes of Transylvania] (in Hungarian). Budapest: Reader's Digest. pp. 206–209. ISBN 978-963-289-214-6.

- Péter, Katalin (1994). "The Golden Age of the Principality (1606–1660)". In Köpeczi, Béla; Barta, Gábor; Bóna, István; Makkai, László; Szász, Zoltán; Borus, Judit (eds.). History of Transylvania. Budapest: Akadémiai Kiadó. pp. 301–358. ISBN 963-05-6703-2.

- R. Várkonyi, Ágnes; Campbell, Alan (2013). "Gábor Bethlen and His European Presence". The Hungarian Historical Review. 2 (4). MTA Történettudományi Intézet: 695–732. ISSN 2063-8647. JSTOR 43264465.

- Settonv, Kenneth (1991). Venice, Austria, and the Turks in the Seventeenth Century. Philadelphia, PA: American Philosophical Society. ISBN 978-0-87169-192-7.

- Sturdy, David J. (2002-02-01). Fractured Europe: 1600 - 1721. Blackwell History of Europe series. Oxford, England: Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20513-5.

External links

Media related to Gábor Bethlen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Gábor Bethlen at Wikimedia Commons- "Bethlen-Gabor" . Encyclopedia Americana. 1920.

- Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). "Bethlen, Gabriel" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 3 (11th ed.). pp. 829–830.

- History of Slovakia: Part of Historic Hungary II - Modern Times (1526–1918)

| Gabriel Bethlen House of Bethlen | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded byGabriel Báthory | Prince of Transylvania 1613–1629 |

Succeeded byCatherine of Brandenburg |

| Preceded byFerdinand II | King of Hungary contested by Ferdinand II 1620–1621 |

Succeeded byFerdinand II |

| Preceded bySigismund Báthory | Duke of Opole 1622–1625 |

Succeeded byWladislaus IV of Poland |