| Revision as of 23:56, 25 October 2009 editEastTN (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,309 edits →Democrats Abroad reaction: This subsection makes no sense; it's not parallel to the other subsections, and it's a reaction to something that is no longer referenced-Kenosis killed the SH section← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:13, 11 December 2024 edit undoAndrew Davidson (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Event coordinators, Extended confirmed users, Page movers, File movers, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers43,654 edits remove banner tag -- vague and stale -- plenty of updates since it was placedTag: Visual edit | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|none}} | |||

| {{See also|Health care in the United States|Uninsured in the United States|History of health care reform in the United States}} | |||

| {{Health care reform in the United States}} | |||

| The debate over '''health care reform in the United States''' centers on questions about whether there is a fundamental ] to health care, on who should have access to health care and under what circumstances, on the quality achieved for the high sums spent, and on the sustainability of expenditures that have been rising faster than the level of general ] and the growth in the ]. The leading cause of personal ] is ]<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |url= http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2009/06/05/earlyshow/health/main5064981.shtml|title= Medical Debt Huge Bankruptcy Culprit — Study: It's Behind Six-In-Ten Personal Filings|publisher= ]|date =June 5, 2009|accessdate=June 22, 2009}}</ref><ref>"Medical Bills Leading Cause of Bankruptcy, Harvard Study Finds", ConsumerAffairs.com, February 3, 2005 http://www.consumeraffairs.com/news04/2005/bankruptcy_study.html#ixzz0QdG8hYUvhttp://www.consumeraffairs.com/news04/2005/bankruptcy_study.html</ref> which is almost unknown in other countries in the developed world. <ref>{{cite news | |||

| | title = Medical Reasons Lie Behind 60 Per Cent Of US Bankruptcies, Study | |||

| | url = http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/152741.php | |||

| | publisher = Medical News Today | |||

| | date = June 15,2009 | |||

| | accessdate = Sept 22, 2009 | |||

| | quote = "Medical bankruptcy is almost a unique American phenomenon, which does not occur in countries that have national health insurance."Dr James E. Dalen, University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson Az | |||

| }}</ref> The United States ], which has a higher level of for-profit providers and for-profit insurers than most similar industrialized countries, is also the most expensive in the world, with ] costing substantially more ] than in any other nation on Earth.<ref name="photius.com">. Press Release WHO/44 21 June 2000.</ref> A greater portion of ] is spent on health care in the U.S. than in any ] except for ],<ref name="WHO 2009">{{cite web |author=WHO |month=May |year=2009 |title=World Health Statistics 2009 |publisher=] |url=http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html |accessdate=August 2, 2009}}</ref> although the actual use of health care services in the U.S., by most measures of health services use, is below the median among ].<ref>Gerard F. Anderson, Uwe E. Reinhardt, Peter S. Hussey and Varduhi Petrosyan, , ''Health Affairs'', Volume 22, Number 3, May/June 2003. Accessed February 27, 2008.</ref> | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=February 2015}} | |||

| According to the ] of the ], the United States is the "only wealthy, industrialized nation that does not ensure that all citizens have coverage".<ref name="IOM">, Institute of Medicine at the National Academies of Science, January 14, 2004, accessed October 22, 2007</ref> Americans are divided along ] lines in their views regarding the role of government in the health economy and especially whether a new public health plan should be created and administered by the federal government.<ref></ref> Those in favor of universal health care argue that the large number of uninsured Americans creates direct and hidden costs shared by all, and that extending coverage to all would lower costs and improve quality.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2004/Insuring-Americas-Health-Principles-and-Recommendations.aspx |title=Insuring America's Health: Principles and Recommendations |accessdate=October 27, 2007 |work=] of the National Academies }}</ref> Opponents of laws requiring people to have health insurance argue that this impinges on their personal freedom.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cato.org/research/articles/reynolds-021003.html |title=No Health Insurance? So What? |accessdate=October 27, 2007 | date=October 3, 2002 | work=The ] }}</ref> Both sides of the ] have also looked to more philosophical arguments, debating whether people have a fundamental right to have health care which needs to be protected by their government.<ref name="CESR">Center for Economic and Social Rights. October 29, 2004.</ref><ref name="Sade">Sade RM. "Medical care as a right: a refutation." ''N Engl J Med.'' 1971 December 2;285(23):1288-92. PMID 5113728. (Reprinted as )</ref> | |||

| {{Healthcare reform in the United States}} | |||

| '''Healthcare reform in the United States''' has had a long ]. Reforms have often been proposed but have rarely been accomplished. In 2010, landmark reform was passed through two ]: the ] (PPACA), signed March 23, 2010,<ref>{{cite news |author1=Stolberg, Sheryl Gay |author2=Pear, Robert |date=March 24, 2010 |title=Obama signs health care overhaul bill, with a flourish |newspaper=] |page=A19 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/24/health/policy/24health.html |access-date=March 23, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |author1=Pear, Robert |author2=Herszenhorn, David M. |date=March 22, 2010 |title=Obama hails vote on health care as answering 'the call of history' |newspaper=The New York Times |page=A1 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2010/03/22/health/policy/22health.html |access-date=March 22, 2010 |quote=With the 219-to-212 vote, the House gave final approval to legislation passed by the Senate on Christmas Eve.}}</ref> and the ] ({{USBill|111|H.R.|4872}}), which amended the PPACA and became law on March 30, 2010.<ref name="reuters.com">{{cite news |author1=Smith, Donna |author2=Alexander, David |author3=Beech, Eric |date=March 19, 2010 |title=Factbox – U.S. healthcare bill would provide immediate benefits |work=Reuters |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSN1914020220100319 |access-date=March 24, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |date=March 26, 2010 |title=Timeline: when healthcare reform will affect you |publisher=CNN |url=http://www.cnn.com/2010/POLITICS/03/23/health.care.timeline/index.html |access-date=March 24, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| Future reforms of the ] continue to be proposed, with notable proposals including a ] and a reduction in ] medical care.<ref name="NYT-20131221">{{cite news |last=Rosenthal |first=Elisabeth |title=News Analysis – Health Care's Road to Ruin |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/22/sunday-review/health-cares-road-to-ruin.html |date=December 21, 2013 |work=The New York Times |access-date=December 22, 2013 }}</ref> The PPACA includes a new agency, the ] (CMS Innovation Center), which is intended to research reform ideas through pilot projects. | |||

| ==Costs== | |||

| Current figures estimate that spending on health care in the U.S. is about 16% of its GDP.<ref name="NHE Fact Sheet"> ], referenced February 26, 2008</ref><ref></ref> In 2007, an estimated $2.26 trillion was spent on health care in the United States, or $7,439 ].<ref>, Office of the Actuary in the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, 2008. Accessed March 20, 2008.</ref> Health care costs are rising faster than ] or inflation, and the health share of GDP is expected to continue its upward trend, reaching 19.5 percent of GDP by 2017.<ref name="NHE Fact Sheet"/> In fact, ''government'' health care spending in the United States is consistently greater, as a portion of GDP, than in Canada, Italy, the United Kingdom and Japan (countries that have predominantly public health care).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.oecd.org/document/16/0,3343,en_2649_34631_2085200_1_1_1_1,00.html|title=OECD Health Data 2009 - Frequently Requested Data|publisher=]|date=June 2009}}</ref> And an even larger portion is paid by ] and individuals themselves. A recent study found that medical expenditure was a significant contributing factor in 62% of ] in the United States during 2007.<ref></ref> "Unless you're ], your family is just one serious illness away from bankruptcy...for ], health insurance offers little protection...," said Dr. David Himmelstein of ], who helped compile the study.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==History of national reform efforts== | |||

| The U.S. spends more on health care per capita than any other UN member nation.<ref name="WHO 2009"/> It also spends a greater fraction of its national budget on health care than Canada, Germany, France, or Japan. In 2004, the U.S. spent $6,102 per capita on health care, 92.7% more than any other ] country, and 19.9% more than ], which, after the U.S., had the highest spending in the ] (OECD).<ref>http://ocde.p4.siteinternet.com/publications/doifiles/012006061T02.xls</ref> Although the U.S. Medicare coverage of prescription drugs began in 2006, most ]ed ]s are more costly in the U.S. than in most other countries. Factors involved are the absence of government ]s, enforcement of ] limiting the availability of ]s until after patent expiration, and the ] purchasing power seen in national single-payer systems.{{Citation needed|date=October 2007}} Some U.S. citizens obtain their medications, directly or indirectly, from foreign sources, to take advantage of lower prices. | |||

| The U.S. system already has substantial public components. The federal ] program covers nearly 45 million elderly and some people with disabilities; the federal-state ] program provides coverage to the poor; the ] (SCHIP) extends coverage to low-income families with children; Native Americans are covered both on the reservation (by tribal hospital), and in the urban setting (by hospitals maintained by the Indian Health Service) ; merchant seamen are covered by the Public Health System;{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} and retired railway workers and military veterans are also covered by the government.<ref></ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] has argued that the Medicare program as currently structured is unsustainable without significant reform, as tax revenues dedicated to the program are not sufficient to cover its rapidly increasing expenditures. Further, the CBO also projects that "total federal Medicare and Medicaid outlays will rise from 4 percent of GDP in 2007 to 12 percent in 2050 and 19 percent in 2082—which, as a share of the economy, is roughly equivalent to the total amount that the federal government spends today. The bulk of that projected increase in health care spending reflects higher costs per beneficiary rather than an increase in the number of beneficiaries associated with an aging population."<ref></ref> The ] reported that the unfunded liability facing Medicare as of January 2007 was $32.1 trillion, which is the ] of the program deficits expected for the next 75 years in the absence of reform.<ref></ref> According to the ], spending on Medicare will grow from approximately $500 billion during 2009 to $930 billion by 2018. Without changes, the system is guaranteed “to basically break the federal budget,” President Obama said at a White House news conference July 22.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Uninsured== | |||

| {{Main|Uninsured in the United States}} | |||

| According to the ], people in the U.S. without health insurance coverage at some time during 2007 totaled 15.3% of the population, or 45.7 million people.<ref name="Census 2007"> ]. Issued August 2008.</ref><ref name="Census 2006"> ]. Issued August 2007.</ref> According to the Census Bureau, this number decreased slightly from 47 million in 2006 due to increased ] in addition to the fact that about 300,000 more people were covered in ] under the ] law in 2007.<ref name="kaisercom"></ref> In 2009, the Census Bureau estimated that there are 47 million Americans who do not have any health insurance at all.<ref>http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/News-Conference-by-the-President-July-22-2009/</ref> Other studies, which complement the Census Bureau and include data from the ], have placed the number of uninsured for all or part of the years 2007-2008 as high as 86.7 million, about 29% of the U.S. population, or about one-in-three among those under 65 years of age.<ref name="familiesusa.org">Families USA (2009) press release summarizing a ] study: "New Report Finds 86.7 Million Americans Were Uninsured at Some Point in 2007-2008" </ref><ref>http://www.familiesusa.org/assets/pdfs/americans-at-risk.pdf</ref> | |||

| It is estimated that the ] and rising unemployment rate likely will have caused the number of uninsured to grow by at least 2 million in 2008.<ref name="kaisercom"/><ref name="familiesusa.org"/> ] wrote that only 38% of small businesses provide health insurance for their employees during 2009, versus 61% in 1993, due to rising costs.<ref></ref> | |||

| During September 2009, Senator ] (D-IL) stated that the average family pays an additional $1,000 per year in insurance premiums to cover the uninsured.<ref></ref> President Obama, in his September 9 remarks to a joint session of Congress on health care, called the cost of uninsured Americans "a hidden and growing tax."<ref>http://www.whitehouse.gov/the_press_office/Remarks-by-the-President-to-a-Joint-Session-of-Congress-on-Health-Care/</ref> However, ] found that while broadening insurance coverage might lead to less cost shifting, "that effect would probably be relatively small and would not directly produce net savings in national or federal spending on health care."<ref>http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/103xx/doc10311/06-16-HealthReformAndFederalBudget.pdf</ref> The ] argues that the uninsured subsidize the insured, do not drive up the cost of health care, and use fewer services than the insured.<ref>http://liberty.pacificresearch.org/docLib/20070408_HPPv5n2_0207.pdf</ref> A 2004 editorial in ] asserted that ] (HHS) data show the uninsured are unfairly billed for services at rates far higher—on average 305% at urban hospitals in California—than are the insured; USA Today concluded that "millions of are forced to subsidize insured patients."<ref name="usatoday.com">http://www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/editorials/2004-07-01-our-view_x.htm</ref> According to the editorial: <blockquote>"Many hospitals say they have to charge the uninsured high 'sticker prices' or risk violating a federal ban on charging Medicare patients more than other customers. Hospitals also must try to collect what patients owe, or they could lose Medicare reimbursement for bad debts, notes a 2003 study by the Commonwealth Fund, a health-policy-research foundation."<ref name="usatoday.com"/></blockquote> | |||

| Citing data from the ] and the experience of ], the ] argues that without the uninsured, "The insured would pay more, not less."<ref>Michael F. Cannon, Briefing Paper no. 114, , September 23, 2009 (pdf accessed October 16, 2009)</ref> | |||

| A 2009 Harvard study published in the American Journal of Public Health found more than 44,800 excess deaths annually in the United States associated with uninsurance,<ref></ref><ref></ref> and more broadly, the total number of people in the United States, whether insured or uninsured, who die because of lack of medical care were estimated in a 1997 analysis to be nearly 100,000 per year.<ref>A 1997 study carried out by Professors David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler (''New England Journal of Medicine'' 336, no. 11 ) "concluded that almost 100,000 people died in the United States each year because of lack of needed care—three times the number of people who died of AIDs." , ''Monthly Review'', Vicente Navarro, September 2003. Retrieved September 10, 2009</ref> | |||

| ==Comparisons with other health care systems== | |||

| ] | |||

| The cost and quality of care in the United States are frequently the two major issues of discussion. While cost comparisons are relatively easy, the reasons for higher costs in the U.S. and quality measures are frequently subject to debate. The ] in such measures as ] and ], which are among the most widely collected, hence useful, international comparative statistics. For 2006-2010, the U.S. life expectancy will lag 38th in the world, after most developed nations, lagging last of the ] (Japan, France, Germany, U.K., U.S.) and just after Chile (35th) and Cuba (37th).<ref>] using: United Nations World Population Prospects: 2006 revision -Table A.17. Life expectancy at birth (years) 2005-2010. All data from the ranking is included, except for ''Martinique'' and ''Guadeloupe'' (due to imaging difficulties).</ref> However, both males and females in the United States have better cancer survivor rates than their counterparts in Europe.<ref>http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/uknews/1560849/UK-cancer-survival-rate-lowest-in-Europe.html</ref> | |||

| In 2000, the ] (WHO) ranked the ] 37th in overall performance, right next to ], and 72nd by overall level of health (among 191 member nations included in the study).<ref name="photius.com"/><ref name="who.int"></ref> The WHO study has been criticized by the free market advocate ] because "fairness in financial contribution" was used as an assessment factor, marking down countries with high per-capita private or fee-paying health treatment.<ref name="fmc">], , ''Free Market Cure'', July 16, 2007</ref> One study found that there was little correlation between the WHO rankings for health systems and the satisfaction of citizens using those systems.<ref name="Public vs the WHO">Robert J. Blendon, Minah Kim and John M. Benson, , Health Affairs, May/June 2001</ref> Some countries, such as Italy and Spain, which were given the highest ratings by WHO were ranked poorly by their citizens while other countries, such as Denmark and Finland, were given low scores by WHO but had the highest percentages of citizens reporting satisfaction with their health care systems.<ref name="Public vs the WHO"/> WHO staff, however, say that the WHO analysis does reflect system "responsiveness" and argue that this is a superior measure to consumer satisfaction, which is influenced by expectations.<ref>Christopher J.L. Murray, Kei Kawabata, and Nicole Valentine, , Health Affairs, May/June 2001</ref> | |||

| Despite larger spending, the United States has a worse ] (6.26)<ref name="im">{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2091rank.html|title=Infant mortality rate|publisher=CIA Factbook|accessdate=August 18, 2009}}</ref> and ] (78.11)<ref name="le">{{cite web|url=https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2102rank.html|title=Life expectancy at birth|publisher=CIA Factbook|accessdate=August 18, 2009}}</ref> than the ] (5.72<ref name="im"/> and 78.67<ref name="le"/>). Various reasons have been suggested to explain the high infant mortality rates in the U.S. The ] (CDC) suggests that higher rates of infant mortality in the U.S. are "due in large part to disparities which continue to exist among various racial and ethnic groups in this country, particularly ]s".<ref name=autogenerated1></ref> Some studies claim the data collected regarding infant mortality and life expectancy do not lend themselves to fair comparison.<ref name=autogenerated4>David Hogberg, ], , July 2006</ref> A ] survey has stated that Americans are less likely than citizens of other countries, such as ], to ] fetuses with disabilities and other medical problems; the group views this a complicating factor towards these calculations.<ref name="Tanner Grass Isn't Greener"/> Other complaints relate to apples-to-oranges comparisons, which calls attention to the fact that different definitions are used to define live births in different nations, and that Europe's definitions are broadly different from that of the USA and Canada. Such differences in basic definitions make statistical equivalences inappropriate. <ref> </ref> | |||

| Another metric used to compare the quality of health care across countries is ] (YPLL). By this measure, the United States comes third to last in the ] for women (ahead of only Mexico and Hungary) and fifth to last for men (ahead of Poland and ] aditionally), according to OECD data. Yet another measure is ] (DALY); again the United States fares relatively poorly.{{Citation needed|date=August 2009}} According to ], health care scholars prefer these more "finely tuned" statistical measures for international comparisons in place of the relatively "crude" infant mortality and life expectancy.<ref></ref> | |||

| Access to advanced medical treatments and technologies in the U.S. is greater than in most other developed nations and waiting times may be substantially shorter for treatment by specialists.<ref name=autogenerated5>Clifford Krauss, The New York Times, February 26, 2006</ref> | |||

| The lack of universal coverage contributes to another flaw in the current U.S. health care system: on most dimensions of performance, it underperforms relative to other industrialized countries.<ref name="Commonwealth">{{cite web |url=http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/publications_show.htm?doc_id=482678 |title=Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: An International Update on the Comparative Performance of American Health Care | date=May 15, 2007 |accessdate=May 22, 2007 |work=Report by the Commonwealth Fund }}</ref> In a 2007 comparison by the ] of health care in the U.S. with that of Germany, Britain, Australia, New Zealand, and Canada, the U.S. ranked last on measures of quality, access, efficiency, equity, and outcomes.<ref name="Commonwealth"/> | |||

| However, a Manhattan Institute study by Frank R. Lichtenberg of Columbia University, found that the correlation between life expectancy and health insurance was not statistically significant.<ref>http://www.manhattan-institute.org/html/mpr_04.htm</ref> He did find that access to advanced drugs (newly approved by the FDA) had a statistically significant correlation with higher rates of life expectancy.Additionally, Dr. Hertzlinger of Harvard University found that Americans are twice as likely to receive life saving kidney dialysis and other expensive life saving treatments than people in the U.K.<Ref>http://www.mhprofessional.com/product.php?isbn=0071487808</ref> | |||

| The U.S. system is often compared with that of its northern neighbor, Canada (see ]). Canada's system is largely publicly funded. In 2006, Americans spent an estimated $6,714 per capita on health care, while Canadians spent US$3,678.<ref name="OECD Canada"></ref> This amounted to 15.3% of U.S. GDP in that year, while Canada spent 10.0% of GDP on health care. | |||

| A 2007 review of all studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the U.S. found that "health outcomes may be superior in patients cared for in Canada versus the United States, but differences are not consistent."<ref name="Open Medicine">Open Medicine, Vol 1, No 1 (2007), Research: A systematic review of studies comparing health outcomes in Canada and the United States, Gordon H. Guyatt, et al.</ref> | |||

| ==History of reform efforts== | |||

| {{Main|History of health care reform in the United States}} | {{Main|History of health care reform in the United States}} | ||

| U.S. efforts to achieve universal coverage began with ], who had the support of ] health care reformers in the 1912 election but was defeated.<ref>{{citation | title = The history of health care as a campaign issue | journal = Physician Executive | date = May-June, 2008 | author = Lee legel | url = http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0843/is_3_34/ai_n27871607 }}</ref> And President Harry S Truman called for universal health care as a part of his ] in 1949 but strong opposition stopped that part of the Fair Deal.<ref> | |||

| In 1949, accessdate=2009-10-07 as part of his Fair Deal: | |||

| *On April 24, 1949 The ] denounced this health program. | |||

| *On April 25, 1949 The Murray-Dingell omnibus health legislation (S.1679 and H.R. 4312) were introduced into the Senate and the House; the Congress adjourned in October 1949 without acting on these bills. | |||

| </ref><ref> | |||

| Monte M. Poen (1996) in his ''Harry S. Truman versus the Medical Lobby: The Genesis of Medicare'', University of Missouri Press ISBN 978-0-8262-1086-9 pp 161-168</ref> | |||

| The following is a summary of reform achievements at the national level in the United States. For failed efforts, state-based efforts, native tribes services, and more details, see the ] article. | |||

| The ] program was established by legislation signed into law on July 30, 1965, by President Lyndon B. Johnson. Medicare is a social insurance program administered by the United States government, providing health insurance coverage to people age 65 and over, or who meet other special criteria. The ] (COBRA) amended the ] of 1974 (ERISA) to give some employees the ability to continue ] coverage after leaving employment. | |||

| * '''1965''': President ] enacted legislation that introduced ], covering both hospital (Part A) and supplemental medical (Part B) insurance for senior citizens. The legislation also introduced ], which permitted the Federal government to partially fund a program for the poor, with the program managed and co-financed by the individual states.<ref name="MedHist">{{cite web |year=2010 |title=Brief history of the Medicare program |publisher=New Tech Media |location=San Antonio, Tex. |url=http://seniorjournal.com/NEWS/2000%20Files/Aug%2000/FTR-08-04-00MedCarHistry.htm |access-date=August 31, 2010 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100628194022/http://seniorjournal.com/NEWS/2000%20Files/Aug%2000/FTR-08-04-00MedCarHistry.htm |archive-date=June 28, 2010 |df=mdy-all }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |author=Ball, Robert M. |date=October 24, 1961 |title=The role of social insurance in preventing economic dependency (address at the Second National Conference on the Churches and Social Welfare, Cleveland, Ohio) |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=] |url=http://www.ssa.gov/history/churches.html |access-date=August 31, 2010}} | |||

| * Robert M. Ball, the then Deputy Director of the Bureau of Old-Age and Survivors Insurance in the Social Security Administration, had defined the major obstacle to financing health insurance for the elderly several years earlier: the high cost of care for the aged and the generally low incomes of retired people. Because retired older people use much more medical care than younger, employed people, an insurance premium related to the risk for older people needed to be high, but if the high premium had to be paid after retirement, when incomes are low, it was an almost impossible burden for the average person. The only feasible approach, he said, was to finance health insurance in the same way as cash benefits for retirement, by contributions paid while at work, when the payments are least burdensome, with the protection furnished in retirement without further payment.</ref> | |||

| * '''1985''': The ] (COBRA) amended the ] of 1974 (ERISA) to give some employees the ability to continue ] coverage after leaving employment.<ref>{{cite web |year=2010 |title=An employee's guide to health benefits under COBRA – The Consolidated Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1986 |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=], ] |url=http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/pdf/cobraemployee.pdf |access-date=November 8, 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131227210946/http://www.dol.gov/ebsa/pdf/cobraemployee.pdf |archive-date=December 27, 2013 |url-status=dead |df=mdy-all }}</ref> | |||

| * '''1996''': The ] (HIPAA) not only protects health insurance coverage for workers and their families when they change or lose their jobs, it also made health insurance companies cover pre-existing conditions. If such condition had been diagnosed before purchasing insurance, insurance companies are required to cover it after patient has one year of continuous coverage. If such condition was already covered on their current policy, new insurance policies due to changing jobs, etc... have to cover the condition immediately.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-104publ191/html/PLAW-104publ191.htm|title=Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996|website=gpo.gov|access-date=27 September 2023}}</ref> | |||

| * '''1997''': The ] introduced two new major Federal healthcare insurance programs, Part C of Medicare and the ], or SCHIP. Part C formalized longstanding "Managed Medicare" (HMO, etc.) demonstration projects and SCHIP was established to provide health insurance to children in families at or below 200 percent of the federal poverty line. Many other "entitlement" changes and additions were made to Parts A and B of fee for service (FFS) Medicare and to Medicaid within an omnibus law that also made changes to the Food Stamp and other Federal programs.<ref>{{cite web |year=2007 |title=What is SCHIP? |location=Washington, D.C. |publisher=] |url=http://www.schip-info.org/42.html |access-date=September 1, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| * '''2000''': The Medicare, Medicaid, and SCHIP Benefits Improvement and Protection Act (BIPA) effectively reversed some of the cuts to the three named programs in the Balanced Budget Act of 1997 because of Congressional concern that providers would stop providing services. | |||

| * '''2003''': The ] (also known as the Medicare Modernization Act or MMA) introduced supplementary optional coverage within Medicare for self-administered prescription drugs and as the name suggests also changed the other three existing Parts of Medicare law. | |||

| * '''2010''': The ], called PPACA or ACA but also known as Obamacare, was enacted, including the following provisions:<ref name="reuters.com" /> | |||

| ** the phased introduction over multiple years of a comprehensive system of mandated health insurance reforms designed to eliminate "some of the worst practices of the insurance companies"—pre-existing condition screening and premium loadings, policy cancellations on technicalities when illness seems imminent, annual and lifetime coverage caps | |||

| ] by state:<ref name="KFF-Medicaid">{{cite web |title=Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map |url=https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map |publisher=]. Map is updated as changes occur. Click on states for details.}}</ref> | |||

| {{legend|#2b83ba|Not adopted}} | |||

| {{legend|#FECDAC|Implemented}}]] | |||

| ** Expanded ] to cover uninsured working-age adults (18-65) earning under 138% of the Federal Poverty Line (and therefore not eligible for subsidies on the health insurance marketplace) along with some whose existing insurance plans were too expensive based on their income. The ACA expanded Medicaid eligibility in all 50 states and the ], however that provision was successfully challenged in ] where the ] ruled that individual states could choose whether or not to expand coverage. Initially 25 states and D.C. expanded Medicaid with funding from the federal government provided by the ACA beginning in 2014, and as of Sep 26 2023 there are 41 states (including Washington, D.C.) that have expanded coverage. | |||

| ** created ]s with three standard insurance coverage levels to enable like-for-like comparisons by consumers, and a web-based ] where consumers can compare prices and purchase plans. | |||

| ** mandates that insurers fully cover certain preventative services | |||

| ** created high-risk pools for uninsureds | |||

| ** tax credits for businesses to provide insurance to employees | |||

| ** created an insurance company ] | |||

| ** allowed dependents to remain on their plan until 26 | |||

| ** It also sets a minimum medical loss ratio of direct health care spending to premium income creates price competition | |||

| ** created ] to study ] funded by a fee on insurers per covered life | |||

| ** allowed for approval of generic ] drugs and specifically allows for 12 years of exclusive use for newly developed biologic drugs | |||

| ** many changes to the 1997, 2000, and 2003 laws that had previously changed Medicare and further expanded eligibility for Medicaid (that expansion was later ruled by the Supreme Court to be at the discretion of the states) | |||

| ** explores some programs intended to increase incentives to provide quality and collaborative care, such as ]s. The ] was created to fund pilot programs which may reduce costs;<ref>Kuraitis V. (2010). . e-CareManagement.com.</ref> the experiments cover nearly every idea healthcare experts advocate, except malpractice/].<ref name="NewYorker-Gawande">{{Cite magazine|author=Gawande A|date=December 2009|title=Testing, Testing|url=https://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/12/14/091214fa_fact_gawande?currentPage=all|magazine=]|access-date=March 22, 2010|author-link=Atul Gawande}}</ref> | |||

| ** requires for reduced Medicare reimbursements for hospitals with excess readmissions and eventually ties physician Medicare reimbursements to quality of care metrics. | |||

| * '''2015''': The ] (MACRA) made significant changes to the process by which many Medicare Part B services are reimbursed and also extended SCHIP | |||

| * '''2017''': ] signs ] in anticipation of a repeal of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, one of his campaign promises. The ] is introduced and passed in the House of Representatives and introduced but not voted upon in the Senate. President Donald Trump signs ] which allows insurance companies to sell low-cost short-term plans with lesser coverage, enables small business to collectively purchase association health plans, and expands health savings accounts. | |||

| * '''2021''': ] repeals the Trump ] and ]. | |||

| * '''2022: ]''' signs the ] into law. The bill allows Medicare to negotiate certain drug prices, caps ] costs for seniors at $2,000 per month, and provides $64 billion for Affordable Care Act subsidies through 2025, originally expanded under the ]. | |||

| ==Motivation== | |||

| Health care reform was a major concern of the ] headed by First Lady ]; however, the ] was not enacted into law. The ] of 1996 (HIPAA) made it easier for workers to keep health insurance coverage when they change jobs or lose a job, and also made use of national data standards for tracking, reporting and protecting personal health information. | |||

| {{Main|Healthcare reform debate in the United States}} | |||

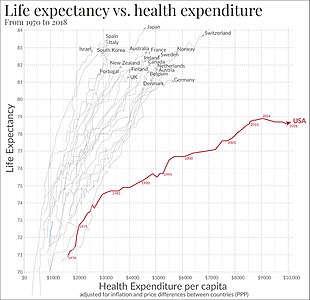

| ].<ref name=life>. May 26, 2017. By ] at ]. Click the sources tab under the chart for info on the countries, healthcare expenditures, and data sources. See the later version of the chart .</ref><ref name=Kenworthy2011>{{Cite web |last= Kenworthy |first= Lane |date= July 10, 2011 |title= America's inefficient health-care system: another look |publisher= Consider the Evidence (blog) |url= http://lanekenworthy.net/2011/07/10/americas-inefficient-health-care-system-another-look/ |access-date= September 11, 2012}}</ref>]] | |||

| ]. Public and private spending. US dollars ]. $6,319 for Canada in 2022. $12,555 for the US in 2022.<ref name=OECD-barcharts/>]] | |||

| ]. Percent of GDP (]). 11.2% for Canada in 2022. 16.6% for the United States in 2022.<ref name=OECD-barcharts>] Data. . {{doi|10.1787/8643de7e-en}}. 2 bar charts: For both: From bottom menus: Countries menu > choose OECD. Check box for "latest data available". Perspectives menu > Check box to "compare variables". Then check the boxes for government/compulsory, voluntary, and total. Click top tab for chart (bar chart). For GDP chart choose "% of GDP" from bottom menu. For per capita chart choose "US dollars/per capita". Click fullscreen button above chart. Click "print screen" key. Click top tab for table, to see data.</ref>]] | |||

| ], compared amongst various first world nations]] | |||

| ] have found that the United States spends more per-capita than other similarly developed nations but falls below similar countries in various health metrics, suggesting inefficiency and waste. In addition, the United States has significant ] and significant impending unfunded liabilities from its aging demographic and its ] programs ] and ] (Medicaid provides free care to anyone that make less than 200% of the Federal Poverty Line). The fiscal and human impact of these issues have motivated reform proposals.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Fundamental health reform like ‘Medicare for All’ would help the labor market: Job loss claims are misleading, and substantial boosts to job quality are often overlooked |url=https://www.epi.org/publication/medicare-for-all-would-help-the-labor-market/ |access-date=2024-10-19 |website=Economic Policy Institute |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| During the ], both the ] and ] campaigns offered health care proposals.<ref>Robin Toner , The New York Times, Tuesday, December 18, 2007</ref><ref> The New York Times, October 3, 2004</ref> As president, ] signed into law the ] which included a prescription drug plan for ] and ] Americans.<ref>http://cms.hhs.gov</ref> | |||

| U.S. healthcare costs were approximately $3.2 trillion or nearly $10,000 per person on average in 2015. Major categories of expense include hospital care (32%), physician and clinical services (20%), and prescription drugs (10%).<ref name="CDC_NCHS1">{{cite web|url=https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/health-expenditures.htm|title=FastStats|date=July 18, 2017|website=www.cdc.gov}}</ref> U.S. costs in 2016 were substantially higher than other OECD countries, at 17.2% GDP versus 12.4% GDP for the next most expensive country (Switzerland).<ref name="OECD_HS1">{{cite web|url=http://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/health-data.htm|title=OECD Health Statistics 2017 - OECD|website=www.oecd.org}}</ref> For scale, a 5% GDP difference represents about $1 trillion or $3,000 per person. Some of the many reasons cited for the cost differential with other countries include: Higher administrative costs of a private system with multiple payment processes; higher costs for the same products and services; more expensive volume/mix of services with higher usage of more expensive specialists; aggressive treatment of very sick elderly versus palliative care; less use of government intervention in pricing; and higher income levels driving greater demand for healthcare.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.pbs.org/newshour/rundown/why-does-health-care-cost-so-much-in-america-ask-harvards-david-cutler/|title=Why does health care cost so much in America? Ask Harvard's David Cutler|website=PBS NewsHour|date=2013-11-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/toddhixon/2012/03/01/why-are-u-s-health-care-costs-so-high/#5e1a5e4e1dae|title=Why Are U.S. Health Care Costs So High?|first=Todd|last=Hixon|website=forbes.com}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2014/07/why-do-other-rich-nations-spend-so-much-less-on-healthcare/374576/|title=Why Do Other Rich Nations Spend So Much Less on Healthcare?|first=Victor R.|last=Fuchs|website=theatlantic.com|date=2014-07-23}}</ref> Healthcare costs are a fundamental driver of ], which leads to coverage affordability challenges for millions of families. There is ongoing debate whether the current law (ACA/Obamacare) and the Republican alternatives (AHCA and BCRA) do enough to address the cost challenge.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vox.com/2017/6/30/15894832/senate-bill-health-prices|title=The Senate bill does nothing to fix America's biggest health care problem|website=vox.com|date=2017-06-30}}</ref> | |||

| ===Health reform and the 2008 presidential election=== | |||

| {{Main|Health care reform in the United States presidential election, 2008}} | |||

| Both of the major party presidential candidates offered positions on health care. | |||

| According to 2009 World Bank statistics, the U.S. had the highest ] relative to the size of the economy (GDP) in the world, even though estimated 50 million citizens (approximately 16% of the September 2011 estimated population of 312 million) lacked insurance.<ref name="WHO 2009">{{cite web |author=WHO |date=May 2009 |title=World Health Statistics 2009 |publisher=] |url=https://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090525094010/http://www.who.int/whosis/whostat/2009/en/index.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=May 25, 2009 |access-date=August 2, 2009}}</ref> In March 2010, billionaire ] commented that the high costs paid by U.S. companies for their employees' health care put them at a competitive disadvantage.<ref>{{Cite news | last = Funk | first = Josh | title = Buffett says economy recovering but at slow rate | newspaper = San Francisco Chronicle | publisher = SFGate.com | date = March 1, 2010 | url = https://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/2010-03-01/business/18371919_1_berkshire-hathaway-billionaire-warren-buffett-health-care | access-date = April 3, 2010 | url-status = live | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100306012352/http://articles.sfgate.com/2010-03-01/business/18371919_1_berkshire-hathaway-billionaire-warren-buffett-health-care | archive-date = March 6, 2010 | df = mdy-all }}</ref> | |||

| ]'s proposals focused on open-market competition rather than government funding. At the heart of his plan were tax credits - $2,500 for individuals and $5,000 for families who do not subscribe to or do not have access to health care through their employer. To help people who are denied coverage by insurance companies due to pre-existing conditions, McCain proposed working with states to create what he called a "Guaranteed Access Plan."<ref>Robert E. Moffit and Nina Owcharenko, The ], October 15, 2008</ref> | |||

| Further, an estimated 77 million ] are reaching retirement age, which combined with significant annual increases in healthcare costs per person will place enormous budgetary strain on U.S. state and federal governments, particularly through ] and ] spending (Medicaid provides long-term care for the elderly poor).<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.economist.com/media/globalexecutive/coming_gen_storm_e_02.pdf |title=coming_gen_storm_e.indd |access-date=January 12, 2012 |newspaper=The Economist}}</ref> Maintaining the long-term fiscal health of the U.S. federal government is significantly dependent on healthcare costs being controlled.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.charlierose.com/download/transcript/10697 |title=Charlie Rose-Peter Orszag Interview Transcript |date=November 3, 2009 |access-date=January 12, 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120111174416/http://www.charlierose.com/download/transcript/10697 |archive-date=January 11, 2012 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> | |||

| ] called for ]. His health care plan called for the creation of a ] that would include both private insurance plans and a Medicare-like government run option. Coverage would be guaranteed regardless of health status, and premiums would not vary based on health status either. It would have required parents to cover their children, but did not require adults to buy insurance. | |||

| ===Insurance cost and availability=== | |||

| '']'' reported that the two plans had different philosophical focuses. They described the purpose of the McCain plan as to "make insurance more affordable," while the purpose of the Obama plan was for "more people to have health insurance."<ref>Stacey Burling, ], September 28, 2008</ref> '']'' characterized the plans similarly.<ref>Tony Leys, ], September 29, 2008</ref> | |||

| {{further|Health insurance coverage in the United States}} | |||

| In addition, the number of employers who offer health insurance has declined and costs for employer-paid health insurance are rising: from 2001 to 2007, premiums for family coverage increased 78%, while wages rose 19% and prices rose 17%, according to the ].<ref name="Kaiser 2007">{{cite press release |title=Health Insurance Premiums Rise 6.1% In 2007, Less Rapidly Than In Recent Years But Still Faster Than Wages And Inflation |publisher=Kaiser Family Foundation |date=September 11, 2007 |url=http://www.kff.org/insurance/ehbs091107nr.cfm |access-date=September 13, 2007 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130329111855/http://www.kff.org/insurance/ehbs091107nr.cfm |archive-date=March 29, 2013 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> Even for those who are employed, the private insurance in the US varies greatly in its coverage; one study by the ] published in ] estimated that 16 million U.S. adults were underinsured in 2003. The underinsured were significantly more likely than those with adequate insurance to forgo health care, report financial stress because of medical bills, and experience coverage gaps for such items as prescription drugs. The study found that underinsurance disproportionately affects those with lower incomes—73% of the underinsured in the study population had annual incomes below 200% of the federal poverty level.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Cathy Schoen |author2=Michelle M. Doty |author3=Sara R. Collins |author4=Alyssa L. Holmgren | title = Insured But Not Protected: How Many Adults Are Underinsured? | journal = Health Affairs Web Exclusive |date=June 14, 2005 |pmid=15956055 |doi=10.1377/hlthaff.w5.289 |doi-access=free | volume = Suppl Web Exclusives | pages = W5–289–W5–302 }}</ref> However, a study published by the ] in 2008 found that the typical large employer ] (PPO) plan in 2007 was more generous than either ] or the ] Standard Option.<ref>Dale Yamamoto, Tricia Neuman and Michelle Kitchman Strollo, , ], September 2008</ref> One indicator of the consequences of Americans' inconsistent health care coverage is a study in ''Health Affairs'' that concluded that half of personal bankruptcies involved medical bills,<ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Himmelstein DU, Warren E, Thorne D, Woolhandler S |s2cid=73034397 |title=Illness and injury as contributors to bankruptcy |journal=Health Aff (Millwood) |volume=Suppl Web Exclusives |pages=W5–63–W5–73 |year=2005 |pmid=15689369 |doi=10.1377/hlthaff.w5.63|url=https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6206ff282722fd78010bf7fc4584bc1ba28e32b9 }}</ref> although other sources dispute this.<ref>Todd Zywicki, , 99 NWU L. Rev. 1463 (2005)</ref> | |||

| There are health losses from insufficient health insurance. A 2009 Harvard study published in the ''American Journal of Public Health'' found more than 44,800 excess deaths annually in the United States due to Americans lacking health insurance.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://pnhp.org/excessdeaths/health-insurance-and-mortality-in-US-adults.pdf|title=American Journal of Public Health | December 2009, Vol 99, No. 12}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://pnhp.org/excessdeaths/excess-deaths-state-by-state.pdf|title=State-by-state breakout of excess deaths from lack of insurance}}</ref> More broadly, estimates of the total number of people in the United States, whether insured or uninsured, who die because of lack of medical care were estimated in a 1997 analysis to be nearly 100,000 per year.<ref>A 1997 study carried out by Professors David Himmelstein and Steffie Woolhandler (''New England Journal of Medicine'' 336, no. 11 1997) "concluded that almost 100,000 people died in the United States each year because of lack of needed care—three times the number of people who died of AIDs." , ''Monthly Review'', Vicente Navarro, September 2003. Retrieved September 10, 2009</ref> A study of the effects of the Massachusetts universal health care law (which took effect in 2006) found a 3% drop in mortality among people 20–64 years old—1 death per 830 people with insurance. Other studies, just as those examining the randomized distribution of Medicaid insurance to low-income people in Oregon in 2008, found no change in death rate.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/lifestyle/health-wellness/2014/05/05/death-rate-drops-massachusetts-after-state-health-law-implemented-study-suggests/8JELx4L1MgWMN4yauxpnyM/story.html|date=May 5, 2014|title=Study calls wide Mass. coverage a lifesaver|agency=Boston Globe}}</ref> | |||

| A poll released in early November 2008, found that voters supporting Obama listed health care as their second priority; voters supporting McCain listed it as fourth, tied with the war in Iraq. Affordability was the primary health care priority among both sets of voters. Obama voters were more likely than McCain voters to believe government can do much about health care costs.<ref>Robert J. Blendon, Drew E. Altman, John M. Benson, Mollyann Brodie,Tami Buhr, Claudia Deane, and Sasha Buscho, '']'' 359;19, November 6, 2008</ref> | |||

| The cost of insurance has been a primary motivation in the reform of the US healthcare system, and many different explanations have been proposed in the reasons for high insurance costs and how to remedy them. One critique and motivation for healthcare reform has been the development of the ]. This relates to moral arguments for health care reform, framing healthcare as a social good, one that is fundamentally immoral to deny to people based on economic status.<ref>{{Cite book|jstor=j.ctt7zswmt.7|date=2014-01-01|publisher=Georgetown University Press|isbn=9781626160774|editor-last=CRAIG|editor-first=DAVID M.|series=Religious Values and American Democracy|pages=85–120|last1=Craig|first1=David M.|title=Health Care as a Social Good}}</ref> The motivation behind healthcare reform in response to the medical-industrial complex also stems from issues of social inequity, promotion of medicine over preventative care.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|jstor=j.ctt183p79j|title=To Live and Die in America: Class, Power, Health and Healthcare|last1=Chernomas|first1=Robert|last2=Hudson|first2=Ian|date=2013-01-01|publisher=Pluto Books|isbn=9780745332123}}</ref> The medical-industrial complex, defined as a network of health insurance companies, pharmaceutical companies, and the like, plays a role in the complexity of the US insurance market and a fine line between government and industry within it.<ref name=":1">{{Cite book|jstor=10.7591/j.ctt1h4mjdm.6|date=2016-01-01|publisher=Cornell University Press|isbn=9781501702310|editor-last=Ehrenreich|editor-first=John|series=How Money, Power, and the Pursuit of Self-Interest Have Imperiled the American Dream|pages=39–77|last1=Ehrenreich|first1=John|title=Third Wave Capitalism|chapter=The Health of Nations|doi=10.7591/9781501703591-004}}</ref> Likewise, critiques of insurance markets being conducted under a capitalistic, free-market model also include that medical solutions, as opposed to preventative healthcare measures, are promoted to maintain this medical-industrial complex.<ref name=":1" /> Arguments for a market-based approach to health insurance include the Grossman model, which is based on an ideal competitive model, but others have critiqued this, arguing that fundamentally, this means that people in higher socioeconomic levels will receive a better quality of healthcare.<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| ==Public policy debate== | |||

| {{Main|Health care reform debate in the United States}} | |||

| ;Uninsured rate | |||

| The political debate over health care reform has for several decades revolved around the questions of whether fundamental reform of the system is needed, what form those reforms should take, and how they should be funded. Issues regarding ] are frequently the subject of political debate.<ref></ref> Whether or not a publicly funded ] system should be implemented is one such example.<ref></ref> | |||

| With the implementation of the ACA, the level of uninsured rates severely decreased in the U.S. This is due to the expansion of qualifications for access to medicaid, subsidizing insurance, prevention of insurance companies from underwriting, as well as enforcing the individual mandate which requires citizens to purchase health insurance or pay a fee. In a research study which was conducted comparing the effects of the ACA before and after it was fully implemented in 2014, it was discovered that ] benefited more than whites with many gaining insurance coverage which they lacked before allowing for many to seek treatment improving their overall health.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Chen|first1=Jie|last2=Vargas-Bustamante|first2=Arturo|last3=Mortensen|first3=Karoline|last4=Ortega|first4=Alexander N.|date=February 2016|title=Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care Access and Utilization Under the Affordable Care Act|journal=Medical Care|volume=54|issue=2|pages=140–146|doi=10.1097/MLR.0000000000000467|issn=0025-7079|pmc=4711386|pmid=26595227}}</ref> In June 2014, ]–Healthways Well–Being conducted a survey and found that the uninsured rate is decreasing with 13 percent of U.S. adults uninsured in 2014 compared to 17 percent in January 2014 and translates to roughly 10 million to 11 million individuals who gained coverage. The survey also looked at the major demographic groups and found each is making progress towards getting health insurance. However, Hispanics, who have the highest uninsured rate of any racial or ethnic group, are lagging in their progress. Under the new health care reform, Latinos were expected to be major beneficiaries of the new health care law. Gallup found that the biggest drop in the uninsured rate (3 percentage points) was among households making less than $36,000 a year.<ref name="ALONSO-ZALDIVAR :survey">{{cite news|url=http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/U/US_HEALTH_OVERHAUL_UNINSURED?SITE=AP&SECTION=HOME&TEMPLATE=DEFAULT&CTIME=2014-03-10-03-31-55|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140310195507/http://hosted.ap.org/dynamic/stories/U/US_HEALTH_OVERHAUL_UNINSURED?SITE=AP&SECTION=HOME&TEMPLATE=DEFAULT&CTIME=2014-03-10-03-31-55|url-status=dead|archive-date=March 10, 2014|title=Survey: Uninsured Rate Drops; Health Law Cited|last=Alonso-Zaldivar|first=Ricardo|date=March 10, 2014|newspaper=The Associated Press|access-date=March 10, 2014}}</ref><ref name="Easly-ACA">{{cite news|url=http://www.politicususa.com/2014/03/10/republicans-darkest-fears-realized-obamacare-number-uninsured-drop-age-group.html|title=Republicans Darkest Fears Realized: ACA Causes Number of Uninsured to Drop Across All Ages|last=Easley|first=Jason|date=March 10, 2014|newspaper=Politicus USA|access-date=March 10, 2014}}</ref><ref name="Howell-uninsured">{{cite news|url=http://www.washingtontimes.com/news/2014/mar/10/rate-uninsured-americans-dropping-gallup/|title=Rate of uninsured Americans is dropping: Gallup|last=Howell|first=Tom|date=March 10, 2014|newspaper=] |access-date=March 10, 2014}}</ref> | |||

| In spite of the amount spent on health care in the U.S., a 2008 report by the ] ranked the United States last in the quality of health care among the 19 compared countries.<ref></ref> Opponents of government intervention, such as the ] and the ], argue that the U.S. system performs better in some areas such as the responsiveness of treatment, the amount of technology available, and higher cure rates for some serious illnesses such as ], ], and ] in men.<ref name="Tanner Grass Isn't Greener"/><ref name="how">{{citenews|url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/07/16/AR2007071601391.html|title=A Story Michael Moore Didn't Tell|publisher=''Washington Post''|date=July 18, 2007|accessdate=August 26, 2009|first=Paul|last=Howard}}</ref> | |||

| ===Waste and fraud=== | |||

| According to economist and former ] ], only a "big, national, public option" can force insurance companies to cooperate, share information, and reduce costs. Scattered, localized, "insurance cooperatives" are too small to do that and are "designed to fail" by the moneyed forces opposing Democratic health care reform.<ref></ref><ref> </ref> | |||

| In December 2011 the outgoing administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, ], asserted that 20% to 30% of health care spending is waste. He listed five causes for the waste: (1) overtreatment of patients, (2) the failure to coordinate care, (3) the administrative complexity of the ], (4) burdensome rules and (5) fraud.<ref>{{cite news | last = Pear | first = Robert | title = Health Official Takes Parting Shot at 'Waste' | newspaper =The New York Times | date = December 3, 2011 | url = https://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/04/health/policy/parting-shot-at-waste-by-key-obama-health-official.html?_r=1&emc=eta1| access-date =December 20, 2011}}</ref> | |||

| An estimated 3–10% of all health care expenditures in the U.S. are fraudulent. In 2011, Medicare and Medicaid made $65 billion in improper payments (including both error and fraud). Government efforts to reduce fraud include $4 billion in fraudulent payments recovered by the Department of Justice and the FBI in 2012, longer jail sentences specified by the Affordable Care Act, and ]—volunteers trained to identify and report fraud.<ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.bankrate.com/financing/retirement/how-big-is-medicare-fraud/ | title=How big is Medicare fraud? | publisher=Bankrate | work=Retirement Blog | date=February 21, 2013 | access-date=November 28, 2013 | author=Phipps, Jennie L.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Current reform advocacy== | |||

| ===General strategies=== | |||

| ] President and CEO Denis Cortese has advocated an overall strategy to guide reform efforts. He argued that the U.S. has an opportunity to redesign its healthcare system and that there is a wide consensus that reform is necessary. He articulated four "pillars" of such a strategy:<ref></ref> | |||

| *Focus on value, which he defined as the ratio of quality of service provided relative to cost; | |||

| *Pay for and align incentives with value; | |||

| *Cover everyone; | |||

| *Establish mechanisms for improving the healthcare service delivery system over the long-term, which is the primary means through which value would be improved. | |||

| In 2007, the Department of Justice and Health and Human Services formed the ] to combat fraud through data analysis and increased community policing. As of May 2013, the Strike Force has charged more than 1,500 people for false billings of more than $5 billion. ] often takes the form of kickbacks and money-laundering. Fraud schemes often take the form of billing for medically unnecessary services or services not rendered.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/2013/May/13-crm-553.html | title=Medicare Fraud Strike Force Charges 89 Individuals for Approximately $223 Million in False Billing | publisher=U.S. Department of Justice | date=May 14, 2013 | access-date=November 28, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| Writing in ], surgeon ] further distinguished between the delivery system, which refers to how medical services are provided to patients, and the payment system, which refers to how payments for services are processed. He argued that reform of the delivery system is critical to getting costs under control, but that payment system reform (e.g., whether the government or private insurers process payments) is considerably less important yet gathers a disproportionate share of attention. Gawande argued that dramatic improvements and savings in the delivery system will take "at least a decade." He recommended changes that address the over-utilization of healthcare; the refocusing of incentives on value rather than profits; and comparative analysis of the cost of treatment across various healthcare providers to identify best practices. He argued this would be an iterative, empirical process and should be administered by a "national institute for healthcare delivery" to analyze and communicate improvement opportunities.<ref name="newyorker.com"></ref> | |||

| ===Quality of care=== | |||

| A report published by the ] in December 2007 examined 15 federal policy options and concluded that, taken together, they had the potential to reduce future increases in health care spending by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years. These options included increased use of health information technology, research and incentives to improve medical decision making, reduced tobacco use and obesity, reforming the payment of providers to encourage efficiency, limiting the tax federal exemption for health insurance premiums, and reforming several market changes such as resetting the benchmark rates for Medicare Advantage plans and allowing the Department of Health and Human Services to negotiate drug prices. The authors based their modeling on the effect of combining these changes with the implementation of universal coverage. The authors concluded that there are no magic bullets for controlling health care costs, and that a multifaceted approach will be needed to achieve meaningful progress.<ref>Cathy Schoen, Stuart Guterman, Anthony Shih, Jennifer Lau, Sophie Kasimow, Anne Gauthier, and Karen Davis, ], December 2007</ref> | |||

| There is significant debate regarding the quality of the U.S. healthcare system relative to those of other countries. Although there are advancements in the quality of care in America due to the acknowledgement of various health related topics such as how insurance plans are now mandated to include coverage for those with mental health and substance abuse disorders as well with the inability to deny a person who has ] through the ACA,<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Skinner|first=Daniel|date=2013|title=Defining Medical Necessity under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act|journal=Public Administration Review|volume=73|pages=S49–S59|issn=0033-3352|jstor=42003021|doi=10.1111/puar.12068}}</ref> there is still much that needs to be improved. Within the U.S., those who are a racial/ethnic minority along with those who poses a lower income have higher chances of experiencing a lower quality of care at higher cost. The most vulnerable to are the elderly and low-income households, and particularly in geographic areas with depleted or stagnant economic activity. One impact of increasing the eligibility age for care is that many will undergo even greater extended periods without adequate health care, posing increased risks to their health and economic stability. Being insured allows individuals access not just to the treatment of existing illnesses, but also very crucial preventative healthcare, which is viewed as the most excellent form of healthcare and allows individuals to take action and make lifestyle adjustments before preventable health issues occur. Despite the advancements with the ACA, this may discourage a person from seeking medical treatment.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=SOMMERS|first1=BENJAMIN D.|last2=McMURTRY|first2=CAITLIN L.|last3=BLENDON|first3=ROBERT J.|last4=BENSON|first4=JOHN M.|last5=SAYDE|first5=JUSTIN M.|date=2017|title=Beyond Health Insurance: Remaining Disparities in US Health Care in the Post-ACA Era|journal=The Milbank Quarterly|volume=95|issue=1|pages=43–69|issn=0887-378X|jstor=26300309|doi=10.1111/1468-0009.12245|pmid=28266070|pmc=5339398}}</ref> ], a pro-] ] system of ] advocacy group, has claimed that a free market solution to health care provides a lower quality of care, with higher mortality rates, than publicly funded systems.<ref name="fpb">, ''Physicians for a National Health Program''</ref> The quality of ] and ] have also been criticized by this same group.<ref>, ''Physicians for a National Health Program''</ref> | |||

| According to a 2000 study of the ], publicly funded systems of industrial nations spend less on health care, both as a percentage of their GDP and per capita, and enjoy superior population-based health care outcomes.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_en.pdf |title=Prelims i-ixx/E |access-date=January 12, 2012}}</ref> However, conservative commentator ] and the ], a ] think tank, have both criticized the WHO's comparison method for being biased; the WHO study marked down countries for having private or fee-paying health treatment and rated countries by comparison to their expected health care performance, rather than objectively comparing quality of care.<ref name="fmc">], {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090312071328/http://www.freemarketcure.com/whynotgovhc.php |date=March 12, 2009 }}, ''Free Market Cure'', July 16, 2007</ref><ref>Glen Whitman, , ], February 28, 2008</ref> | |||

| ===Over-utilization of services and comparative effectiveness research=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Over-utilization of healthcare services refers to when a patient overuses a doctor or to a doctor ordering more tests or services than may be required to address a particular condition effectively. Several treatment alternatives may be available for a given medical condition, with significantly different costs yet no statistical difference in outcome. Such scenarios offer the opportunity to maintain or improve the quality of care, while significantly reducing costs, through comparative effectiveness research. According to economist ] and research cited by the ] (CBO), the cost of healthcare per person in the U.S. also varies significantly by geography and medical center, with little or no statistical difference in outcome.<ref></ref> Comparative effectiveness research has shown that significant cost reductions are possible. ] Director ] stated: "Nearly thirty percent of Medicare's costs could be saved without negatively affecting health outcomes if spending in high- and medium-cost areas could be reduced to the level of low-cost areas."<ref name="newyorker.com"/> | |||

| ===Independent advisory panels=== | |||

| President Obama has proposed an "Independent Medicare Advisory Panel" (IMAC) to make recommendations on Medicare reimbursement policy and other reforms. Comparative effectiveness research would be one of many tools used by the IMAC. The IMAC concept was endorsed in a letter from several prominent healthcare policy experts, as summarized by ] Director ]:<ref></ref> | |||

| Some medical researchers say that patient satisfaction surveys are a poor way to evaluate medical care. Researchers at the ] and the ] asked 236 elderly patients in two different managed care plans to rate their care, then examined care in medical records, as reported in ]. There was no correlation. "Patient ratings of health care are easy to obtain and report, but do not accurately measure the technical quality of medical care," said John T. Chang, ], lead author.<ref> David Wessel, Wall Street Journal, September 7, 2006.</ref><ref>{{cite press release |title=Rand study finds patients' ratings of their medical care do not reflect the technical quality of their care |publisher=RAND Corporation |date=May 1, 2006 |url=https://www.rand.org/news/press.06/05.01.html |access-date=August 27, 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |vauthors=Chang JT, Hays RD, Shekelle PG, etal |s2cid=53091172 |title=Patients' global ratings of their health care are not associated with the technical quality of their care |journal=Ann. Intern. Med. |volume=144 |issue=9 |pages=665–72 |date=May 2006 |pmid=16670136 |doi=10.7326/0003-4819-144-9-200605020-00010|citeseerx=10.1.1.460.3525 }}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|Their support of the IMAC proposal underscores what most serious health analysts have recognized for some time: that moving toward a health system emphasizing quality rather than quantity will require continual effort, and that a key objective of legislation should be to put in place structures (like the IMAC) that facilitate such change over time. And ultimately, without a structure in place to help contain health care costs over the long term as the health market evolves, nothing else we do in fiscal policy will matter much, because eventually rising health care costs will overwhelm the federal budget.}} | |||

| ==Public opinion== | |||

| Both Mayo Clinic CEO Dr. Denis Cortese and Surgeon/Author Atul Gawande have argued that such panel(s) will be critical to reform of the delivery system and improving value. Washington Post columnist ] has also recommended that President Obama engage someone like Cortese to have a more active role in driving reform efforts.<ref></ref> | |||

| ]'' magazine]] | |||

| Public opinion polls have shown a majority of the public supports various levels of government involvement in health care in the United States,<ref name="content.healthaffairs.org">''Health Affairs'', Volume 20, No. 2. "Americans' Views on Health Policy: A Fifty-Year Historical Perspective." March/April 2001. http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/20/2/33.full.pdf+html</ref> with stated preferences depending on how the question is asked.<ref name="politifact1">{{cite web|url=http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/statements/2009/oct/01/michael-moore/michael-moore-claims-majority-favor-single-payer-h/ |title=Michael Moore claims a majority favor a single-payer health care system |publisher=PolitiFact |access-date=November 20, 2011}}</ref> Polls from Harvard University in 1988,<ref>{{cite journal | author = Blendon Robert J. | year = 1989 | title = Views on health care: Public opinion in three nations | journal = Health Affairs | volume = 8 | issue = 1| pages = 149–57 | doi=10.1377/hlthaff.8.1.149| pmid = 2707718 |display-authors=etal| doi-access = free }}</ref> the '']'' in 1990,<ref>''Los Angeles Times'' poll: "Health Care in the United States," Poll no. 212, Storrs, Conn.: Administered by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research, March 1990</ref> and ''The Wall Street Journal'' in 1991<ref>Wall Street Journal-NBC poll: Michael McQueen, "Voters, sick of the current health –care systems, want federal government to prescribe remedy," The Wall Street Journal, June 28, 1991</ref> all showed strong support for a health care system compared to the system in Canada. More recently, however, polling support has declined for that sort of health care system,<ref name="content.healthaffairs.org"/><ref name="politifact1"/> with a 2007 Yahoo/AP poll showing 54% of respondents considered themselves supporters of "single-payer health care,"<ref>AP/Yahoo poll: Administered by Knowledge Networks, December 2007: http://surveys.ap.org/data/KnowledgeNetworks/AP-Yahoo_2007-08_panel02.pdf {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131005003222/http://surveys.ap.org/data/KnowledgeNetworks/AP-Yahoo_2007-08_panel02.pdf |date=October 5, 2013 }}</ref> a majority in favor of a number of reforms according to a joint poll with the ''Los Angeles Times'' and ''Bloomberg'',<ref>''Los Angeles Times''/''Bloomberg'': {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150908012914/http://www.nationaljournal.com/scripts/printpage.cgi?%2Fmembers%2Fpolltrack%2F2007%2Ftodays%2F10%2F1025latimesbloomberg.htm |date=September 8, 2015 }} October 25, 2007.</ref> and a plurality of respondents in a 2009 poll for '']'' magazine showed support for "a national single-payer plan similar to Medicare for all".<ref>''Time'' magazine/ABT SRBI – July 27–28, 2009 Survey: {{cite web |url=http://www.srbi.com/TimePoll4794_Final_%20Report.pdf |title=Archived copy |access-date=2009-09-13 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101231023337/http://www.srbi.com/TimePoll4794_Final_%20Report.pdf |archive-date=December 31, 2010 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> Polls by Rasmussen Reports in 2011<ref>: Rasmussen Reports. January 1, 2010. Retrieved November 20, 2011.</ref> and 2012<ref>: Rasmussen Reports. Retrieved December 30, 2012.</ref> showed pluralities opposed to single-payer health care. Many other polls show support for various levels of government involvement in health care, including polls from '']''/]<ref>{{cite news|last=Sack |first=Kevin |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/21/health/policy/21poll.html |title=In Poll, Wide Support for Government-Run Health |work=The New York Times |date=June 20, 2009 |access-date=January 12, 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite news| url=http://www.cbsnews.com/htdocs/pdf/SunMo_poll_0209.pdf |title=CBS News/New York Times Poll, For Release: Sunday, February 1, 2009, 9:00 AM, American Public Opinion: Today Vs. 30 Years Ago, January 11–15, 2009 | work=CBS News |access-date=February 19, 2015}}</ref> and '']''/],<ref>{{cite web|url=https://abcnews.go.com/images/pdf/935a3HealthCare.pdf |title=Here's an initial summary of headlines from our health care poll, followed by the full trended results |website=] |access-date=January 12, 2012}}</ref> showing favorability for a form of ]. The ]<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.kff.org/kaiserpolls/upload/7943.pdf |title=Kaiser Health Tracking Poll: July 2009 – Topline |access-date=January 12, 2012|date=2009-07-02 }}</ref> showed 58% in favor of a national health plan such as Medicare-for-all in 2009, with support around the same level from 2017 to April 2019, when 56% said they supported it.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.kff.org/interactive/tracking-public-opinion-on-national-health-plan/|title=Tracking Public Opinion on National Health Plan: Interactive|date=2019-04-24|website=The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation|access-date=2019-05-07}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.kff.org/slideshow/public-opinion-on-single-payer-national-health-plans-and-expanding-access-to-medicare-coverage/|title=Public Opinion on Single-Payer, National Health Plans, and Expanding Access to Medicare Coverage|date=2019-04-24|website=The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation|access-date=2019-05-07}}</ref> A ] poll in three states in 2008 found majority support for the government ensuring "that everyone in the United States has adequate health-care" among likely Democratic primary voters.<ref>{{cite web |author=Quinnipiac University – Office of Public Affairs |url=http://www.quinnipiac.edu/x2882.xml?ReleaseID=1164 |title=Question 9: "Do you think it's the government's responsibility to make sure that everyone in the United States has adequate health-care, or don't you think so?" |publisher=Quinnipiac.edu |date=April 2, 2008 |access-date=January 12, 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111031064609/http://www.quinnipiac.edu/x2882.xml?ReleaseID=1164 |archive-date=October 31, 2011 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> | |||

| A 2001 article in the ] '']'' studied fifty years of American public opinion of various health care plans and concluded that, while there appears to be general support of a "national health care plan," poll respondents "remain satisfied with their current medical arrangements, do not trust the federal government to do what is right, and do not favor a single-payer type of national health plan."<ref name="content.healthaffairs.org"/> ] rated a 2009 statement by ] "false" when he stated that "he majority actually want single-payer health care." According to Politifact, responses on these polls largely depend on the wording. For example, people respond more favorably when they are asked if they want a system "like Medicare".<ref name="politifact1"/> | |||

| ===Tax reform=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The ] has described how the tax treatment of insurance premiums may affect behavior:<ref></ref> | |||

| {{Quote|One factor perpetuating inefficiencies in health care is a lack of clarity regarding the cost of health insurance and who bears that cost, especially employment-based health insurance. Employers’ payments for employment-based health insurance and nearly all payments by employees for that insurance are excluded from individual income and payroll taxes. Although both theory and evidence suggest that workers ultimately finance their employment-based insurance through lower take-home pay, the cost is not evident to many workers...If transparency increases and workers see how much their income is being reduced for employers’ | |||

| contributions and what those contributions are paying for, there might be a broader change in cost-consciousness that shifts demand.}} | |||

| ==Alternatives and research directions== | |||

| ] wrote in the '']'' that the current exclusion of insurance premiums from compensation represents a $200 billion subsidy for the private insurance industry and that it would likely not exist without it.<ref></ref> | |||

| There are alternatives to the exchange-based market system which was enacted by the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act which have been proposed in the past and continue to be proposed, such as a single-payer system and allowing health insurance to be regulated at the federal level. | |||

| In addition, the Patient Protection and Affordable Health Care Act of 2010 contained provisions which allows the ] (CMS) to undertake pilot projects which, if they are successful could be implemented in future. | |||

| Employer-provided health insurance receives uncapped tax benefits. According to the OECD, it "encourages the purchase of more generous insurance plans, notably plans with little cost sharing, thus exacerbating moral hazard".<ref name="oecdhealthreform2008">{{cite web|url=http://www.oecd.org/document/51/0,3343,en_2649_34117_41809843_1_1_1_1,00.html|title=Economic Survey of the United States 2008: Health Care Reform|publisher=OECD|date=December 9, 2008}}</ref> Consumers want unfettered access to medical services; they also prefer to pay through insurance or tax rather than out of pocket. These two needs create cost-efficiency challenges for health care.<ref name="Kling">{{cite book |title=Crisis of Abundance: Rethinking How We Pay for Health Care |last=Kling |first=Arnold |authorlink=Arnold Kling |year=2006 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1930865891 |pages= }}</ref> Some studies have found no consistent and systematic relationship between the type of financing of health care and cost containment.<ref>Sherry A. Glied, , ] Working Paper No. 13881, March 2008</ref> | |||

| ===Single-payer health care=== | |||

| Premium tax subsidies to help individuals purchase their own health insurance have also been suggested as a way to increase coverage rates. Research confirms that consumers in the individual health insurance market are sensitive to price. It appears that price sensitivity varies among population subgroups and is generally higher for younger individuals and lower income individuals. However, research also suggests that subsidies alone are unlikely to solve the uninsured problem in the U.S.<ref> ], 2005 </ref><ref>M. Susan Marquis, Melinda Beeuwkes Buntin, Jose J. Escarce, Kanika Kapur, and Jill M. Yegian, Health Services Research 39:5 (October 2004)</ref> | |||

| {{Further|Single-payer healthcare#United States}} | |||