| Revision as of 16:04, 25 December 2009 view sourceTaivoLinguist (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers32,239 edits Do not replace text until a clear consensus has been reached ON TALK PAGE. Discussions are underway← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:29, 7 January 2025 view source KMaster888 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,260 edits ce | ||

| (930 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Historical region of West Asia}} | |||

| {{Otheruses}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Redirect|The Two Rivers|other uses|Two Rivers (disambiguation){{!}}Two Rivers}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| {{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=300|caption_align=center | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | direction =vertical | |||

| | header=Mesopotamia | |||

| | image1 = N-Mesopotamia and Syria english.svg | |||

| | caption1 = A map showing the extent of Mesopotamia. Shown are ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ], from north to south. | |||

| | image2 = Mesopotamia 9 October 2020.jpg| | |||

| | caption2 = A modern satellite view of Mesopotamia, October 2020. | |||

| | footer= | |||

| }} | |||

| {{History of Iraq}} | |||

| '''Mesopotamia'''{{efn|{{langx|tr|Mezopotamya}}; {{langx|grc|Μεσοποταμία}} ''Mesopotamíā''; {{langx|ar|بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن}} {{transl|ar|Bilād ar-Rāfidayn}} or {{lang|ar|بَيْنُ ٱلْنَهْرَيْن}} {{transl|ar|Bayn ul-Nahrayn}}; {{langx|fa|میانرودان}} {{transl|fa|miyân rudân}}; {{langx|syc|ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ}}, {{transl|syc|Bēṯ Nahrēn}}}} is a ] of ] situated within the ], in the northern part of the ]. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Seymour |first=Michael |date=2004 |title=Ancient Mesopotamia and Modern Iraq in the British Press, 1980–2003 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/383004 |journal=Current Anthropology |volume=45 |issue=3 |pages=351–368 |doi=10.1086/383004 |jstor=10.1086/383004 |s2cid=224788984 |issn=0011-3204 |access-date=30 April 2022 |archive-date=30 April 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220430014407/https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/383004 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="miqueletal" /> In the broader sense, the historical region of Mesopotamia also includes parts of present-day ], ], ] and ].<ref name="research_gate">{{cite journal|title=Sea Level Changes in the Mesopotamian Plain and Limits of the Arabian Gulf: A Critical Review|date=January 2020|pages=88–110|journal=Journal of Earth Sciences and Geotechnical Engineering|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/340066759|volume=10|last1=Sissakian|first1=Varoujan K.|last2=Adamo|first2=Nasrat|last3=Al-Ansari|first3=Nadhir|last4=Mukhalad|first4=Talal|last5=Laue|first5=Jan|issue=4}}</ref><ref>{{citation |title=Ancient Mesopotamia. The Eden that never was |last=Pollock |first=Susan |year=1999 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Cambridge |isbn=978-0-521-57568-3 |series=Case Studies in Early Societies |page=1}}</ref> | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes|expiry=December 26, 2008}} | |||

| {{Ancient Mesopotamia}} | |||

| Mesopotamia is the site of the earliest developments of the ] from around 10,000 BC. It has been identified as having "inspired some of the most important developments in human history, including the invention of the ], the planting of the first ] ]s, the development of ] script, ], ], and ]". It is recognised as the cradle of some of the world's earliest civilizations.<ref name="historyandpolicy">{{cite web |last=Milton-Edwards |first=Beverley |date=May 2003 |title=Iraq, past, present and future: a thoroughly-modern mandate? |url=http://www.historyandpolicy.org/papers/policy-paper-13.html |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101208112958/http://www.historyandpolicy.org/papers/policy-paper-13.html |archive-date=8 December 2010 |access-date=9 December 2010 |work=History & Policy |location=]}}</ref> | |||

| '''Mesopotamia''' "''land between the rivers''" (]: ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪܝܢ "''Bet Nahrain''", ]: بلاد الرافدين ]: "''Bilad Al-Rafidayn''")<ref name="Ashmolean">Peter Roger, Stuart Moorey, ''Ancient Iraq: (Assyria and Babylonia)'', Ashmolean Museum (1976).</ref><ref name="Dorling">Philip Steele, ''Ancient Iraq'', ] (2007).</ref><ref name="Penguin">Georges Roux, ''Ancient Iraq'', ] (1980).</ref><ref name="Princeton">Karen Polinger Foster, ''Civilizations of Ancient Iraq'', ] (2009).</ref><ref name="LOC">http://ancienthistory.about.com/od/neareast/a/LOCIraq.htm ] Article on Ancient Iraq.</ref> is a ] for the ancient ]–] ], largely corresponding to ],<ref name="Ashmolean"/><ref name="Dorling"/><ref name="Penguin"/><ref name="Princeton"/><ref name="LOC"/><ref name="BM">{{cite web|url=http://www.mesopotamia.co.uk/geography/home_set.html|title=Mesopotamia – The British Museum}}</ref><ref>Suha Rassam, Christianity in Iraq: its origins and development to the present day, Gracewing Publishing, 2005.</ref> and northeastern ]. Southeastern ] and the ] province of southwestern ] are sometimes considered to be extensions of the Mesopotamian plain.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia|url=http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9045360/Khuzestan |title=Khuzestan |publisher=Britannica Online Encyclopedia |year=2008 |accessdate=2008-12-27}}</ref> | |||

| The ] and ], each originating from different areas, dominated Mesopotamia from the beginning of ] ({{circa|3100 BC}}) to the ] in 539 BC. The rise of empires, beginning with ] around 2350 BC, characterized the subsequent 2,000 years of Mesopotamian history, marked by the succession of kingdoms and empires such as the ]. The early second millennium BC saw the polarization of Mesopotamian society into ] in the north and ] in the south. From 900 to 612 BC, the ] asserted control over much of the ancient Near East. Subsequently, the Babylonians, who had long been overshadowed by Assyria, ], dominating the region for a century as the final independent Mesopotamian realm until the modern era.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Lemche |first=Niels Peter |title=Historical dictionary of ancient Israel |date=2004 |publisher=Scarecrow Press |isbn=978-0-8108-4848-1 |series=Historical dictionaries of ancient civilizations and historical eras |location=Lanham, Md. |pages=64–67 |chapter=Assyria and Babylonia |quote=}}</ref> In 539 BC, Mesopotamia was conquered by the ]. The area was next conquered by ] in 332 BC. After his death, it became part of the Greek ]. | |||

| Widely considered as the ],<ref name="Ashmolean"/><ref name="Dorling"/><ref name="Penguin"/><ref name="LOC"/> ] Mesopotamia included ]ian, ]ian, ]n and ]n empires. In the ], it was ruled by the ] and ], and later conquered by the ]. It mostly remained ] until the 7th century ] of the ]. | |||

| Around 150 BC, Mesopotamia was under the control of the ]. It became a battleground between the ] and Parthians, with western parts of the region coming under ephemeral Roman control. In 226 AD, the eastern regions of Mesopotamia fell to the ]. The division of the region between the Roman Byzantine Empire from 395 AD and the Sassanid Empire lasted until the 7th century ] of the ] and the ] from the Byzantines. A number of primarily neo-Assyrian and Christian native Mesopotamian states existed between the 1st century BC and 3rd century AD, including ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The name ''Mesopotamia'' was coined by the ] historian ] in the ] during the ] period to refer to the combined plains of the ] and ] rivers, bordered on the north by the ] mountains, to the south by the ], to the west by the ] and to the east by the ].<ref name="Sterling">], ''The Illustrated Dictionary & Concordance of the Bible'', ] (2005).</ref> The name '']'' corresponded to a similar geographical concept and was coined at the time of the ]ization of the region, in the ].<ref>Finkelstein, J. J.; 1962. “Mesopotamia”, ''Journal of Near Eastern Studies'' 21: 73–92</ref> It is thought that the Sumerians referred to the entire ] as ''']''' in ] (lit. "land"). | |||

| The regional toponym ''Mesopotamia'' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|m|ɛ|s|ə|p|ə|ˈ|t|eɪ|m|i|ə}}, {{langx|grc|Μεσοποταμία}} ' between rivers'; {{langx|ar|بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن}} {{transl|ar|Bilād ar-Rāfidayn}} or {{lang|ar|بَيْن ٱلنَّهْرَيْن}} {{transl|ar|Bayn an-Nahrayn}}; {{langx|fa|میانرودان}} {{transl|fa|miyân rudân}}; {{langx|syr|ܒܝܬ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ}} {{transl|syr|]}} "(land) between the (two) rivers") comes from the ] root words {{lang|grc|μέσος}} ({{transl|grc|mesos}}, 'middle') and {{lang|grc|ποταμός}} ({{transl|grc|potamos}}, 'river')<ref>{{cite EB1911 |wstitle=Mesopotamia |volume=18 |pages=179–187 |first=Hope Waddell |last=Hogg}}</ref> and translates to '(land) between rivers', likely being a ] of the older ] term, with the Aramaic term itself likely being a calque of the ] ''birit narim''. It is used throughout the Greek ] ({{circa|250 BC}}) to translate the Hebrew and Aramaic equivalent ''Naharaim''. An even earlier Greek usage of the name ''Mesopotamia'' is evident from '']'', which was written in the late 2nd century AD but specifically refers to sources from the time of ]. In the ''Anabasis'', Mesopotamia was used to designate the land east of the ] in north ]. | |||

| == History == | |||

| {{Main|History of Mesopotamia|Timeline of Ancient Mesopotamia|History of Iraq}} | |||

| The ] term {{transl|arc|biritum/birit narim}} corresponded to a similar geographical concept.<ref>{{citation |last1=Finkelstein |first1=J. J. |title=Mesopotamia |journal=Journal of Near Eastern Studies |volume=21 |issue=2 |pages=73–92 |year=1962 |doi=10.1086/371676 |jstor=543884 |s2cid=222432558}}.</ref> Later, the term ''Mesopotamia'' was more generally applied to all the lands between the Euphrates and the ], thereby incorporating not only parts of Syria but also almost all of ] and southeastern ].<ref name=fosterpolingerfoster>{{citation |title=Civilizations of ancient Iraq |last1=Foster |first1=Benjamin R. |last2=Polinger Foster |first2=Karen |year=2009 |publisher=Princeton University Press |location=Princeton |isbn=978-0-691-13722-3 }}</ref> The neighbouring ]s to the west of the Euphrates and the western part of the ] are also often included under the wider term ''Mesopotamia''.<ref name="canard">{{citation |last1=Canard |first1=M. |title=Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition |year=2011 |editor1-last=Bearman |editor1-first=P. |chapter=al-ḎJazīra, Ḏjazīrat Aḳūr or Iḳlīm Aḳūr |location=Leiden, Netherlands |publisher=Brill Online |oclc=624382576 |editor2-last=Bianquis |editor2-first=Th. |editor3-last=Bosworth |editor3-first=C. E. |editor4-last=van Donzel |editor4-first=E. |editor5-last=Heinrichs |editor5-first=W. P. |editor3-link=Clifford Edmund Bosworth}}.</ref><ref name="wilkinson2000">{{citation |last1=Wilkinson |first1=Tony J. |title=Regional approaches to Mesopotamian archaeology: the contribution of archaeological surveys |journal=Journal of Archaeological Research |volume=8 |issue=3 |pages=219–267 |year=2000 |doi=10.1023/A:1009487620969 |issn=1573-7756 |s2cid=140771958}}.</ref><ref name="matthews2003">{{citation |last=Matthews |first=Roger |title=The archaeology of Mesopotamia. Theories and approaches |year=2003 |series=Approaching the past |location=Milton Square |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-25317-8}}.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| A further distinction is usually made between ''Northern'' or '']'' and ''Southern'' or '']''.<ref name="miqueletal">{{citation |last1=Miquel |first1=A. |title=Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second Edition |year=2011 |editor1-last=Bearman |editor1-first=P. |chapter=ʿIrāḳ |location=Leiden, Netherlands |publisher=Brill Online |oclc=624382576 |last2=Brice |first2=W. C. |last3=Sourdel |first3=D. |last4=Aubin |first4=J. |last5=Holt |first5=P. M. |last6=Kelidar |first6=A. |last7=Blanc |first7=H. |last8=MacKenzie |first8=D. N. |last9=Pellat |first9=Ch. |editor2-last=Bianquis |editor2-first=Th. |editor3-last=Bosworth |editor3-first=C. E. |editor4-last=van Donzel |editor4-first=E. |editor5-last=Heinrichs |editor5-first=W. P. |editor3-link=Clifford Edmund Bosworth}}.</ref> Upper Mesopotamia, also known as the ''Jazira'', is the area between the Euphrates and the Tigris from their sources down to ].<ref name=canard/> Lower Mesopotamia is the area from Baghdad to the ] and includes Kuwait and parts of western Iran.<ref name=miqueletal/> | |||

| In modern academic usage, the term ''Mesopotamia'' often also has a chronological connotation. It is usually used to designate the area until the ], with names like ''Syria'', ''Jazira'', and ''Iraq'' being used to describe the region after that date.<ref name=fosterpolingerfoster/><ref name="bahrani">{{citation |last1=Bahrani |first1=Z. |title=Archaeology under fire: Nationalism, politics and heritage in the Eastern Mediterranean and Middle East |pages=159–174 |year=1998 |editor1-last=Meskell |editor1-first=L. |chapter=Conjuring Mesopotamia: imaginative geography and a world past |location=London, England |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-19655-0 |author-link=Zainab Bahrani}}.</ref> It has been argued that these later euphemisms{{clarify|date=September 2021}} are ] terms attributed to the region in the midst of various 19th-century Western encroachments.<ref name=bahrani/><ref>{{cite journal|last=Scheffler|first=Thomas|year=2003|title='Fertile crescent', 'Orient', 'Middle East': the changing mental maps of Southeast Asia|journal=European Review of History|volume=10|issue=2|pages=253–272|doi=10.1080/1350748032000140796|s2cid=6707201 }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| {{Main|Geography of Mesopotamia}} | |||

| ] river flowing through the region of modern ] in Upper Mesopotamia.]] | |||

| ] at night, southern Iraq. A reed house (]) and a narrow canoe (]) are in the water. Mudhif structures have been one of the traditional types of structures, built by the ] of southern Mesopotamia for at least 5,000 years. A carved elevation of a typical mudhif, dating to around 3,300 BC was discovered at ].<ref>Broadbent, G., "The Ecology of the Mudhif", in: Geoffrey Broadbent and C. A. Brebbia, ''Eco-architecture II: Harmonisation Between Architecture and Nature,'' WIT Press, 2008, pp. 15–26.</ref>]] | |||

| Mesopotamia encompasses the land between the ] and ] rivers, both of which have their headwaters in the neighboring ]. Both rivers are fed by numerous tributaries, and the entire river system drains a vast mountainous region. Overland routes in Mesopotamia usually follow the Euphrates because the banks of the Tigris are frequently steep and difficult. The climate of the region is semi-arid with a vast desert expanse in the north which gives way to a {{convert|15000|km2|sqmi|adj=on}} region of marshes, lagoons, mudflats, and reed banks in the south. In the extreme south, the Euphrates and the Tigris unite and empty into the ]. | |||

| The ] environment ranges from the northern areas of rain-fed agriculture to the south where irrigation of agriculture is essential.{{sfn|Emberling|2015|p=255}} This irrigation is aided by a high water table and by melting snows from the high peaks of the northern ] and from the Armenian Highlands, the source of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers that give the region its name. The usefulness of irrigation depends upon the ability to mobilize sufficient labor for the construction and maintenance of canals, and this, from the earliest period, has assisted the development of urban settlements and centralized systems of political authority. | |||

| Agriculture throughout the region has been supplemented by nomadic pastoralism, where tent-dwelling nomads herded sheep and goats (and later camels) from the river pastures in the dry summer months, out into seasonal grazing lands on the desert fringe in the wet winter season. The area is generally lacking in building stone, precious metals, and timber, and so historically has relied upon long-distance trade of agricultural products to secure these items from outlying areas.{{sfn|Emberling|2015|p=256}} In the marshlands to the south of the area, a complex water-borne fishing culture has existed since prehistoric times and has added to the cultural mix. | |||

| Periodic breakdowns in the cultural system have occurred for a number of reasons. The demands for labor has from time to time led to population increases that push the limits of the ecological ], and should a period of climatic instability ensue, collapsing central government and declining populations can occur. Alternatively, military vulnerability to invasion from marginal hill tribes or nomadic pastoralists has led to periods of trade collapse and neglect of irrigation systems. Equally, centripetal tendencies amongst city-states have meant that central authority over the whole region, when imposed, has tended to be ephemeral, and localism has fragmented power into tribal or smaller regional units.<ref>Thompson, William R. (2004) "Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Serial Mesopotamian Fragmentation", (Vol 3, Journal of World-Systems Research).</ref> These trends have continued to the present day in Iraq. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| The urban history of Mesopotamia begins with the emergence of urban societies in northern Iraq in the early ]. | |||

| {{Main|History of Mesopotamia|Prehistory of Mesopotamia}} | |||

| {{Further|History of Iraq|History of the Middle East|Chronology of the ancient Near East}} | |||

| ], a ruler around 2090 BC]] | |||

| The prehistory of the ] begins in the ] period. Therein, writing emerged with a pictographic script, ], in the Uruk IV period ({{circa|late 4th millennium BC}}). The documented record of actual historical events—and the ancient history of lower Mesopotamia—commenced in the early-third millennium BC with cuneiform records of early dynastic kings. This entire history ends with either the arrival of the ] in the late 6th century BC or with the Muslim conquest and the establishment of the ] in the late 7th century AD, from which point the region came to be known as ]. In the long span of this period, Mesopotamia housed some of the world's most ancient highly developed, and socially complex states. | |||

| A cultural continuity and spatial homogeneity for this entire historical geography ("the Great Tradition") is popularly assumed, though the assumption is problematic. Mesopotamia housed some of the world's most ancient states with highly developed social complexity. The region was famous as one of the four ] civilizations where ] was first invented, along with the ] valley in ], the ] in the ]<ref>http://www.harappa.com/har/indus-saraswati-geography.html</ref><ref>http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/286837/Indus-civilization</ref> and ] valley in ]. | |||

| Mesopotamia housed historically important cities such as ], ], ], and ] as well as major territorial states such as the city of |

The region was one of the ] where ] was invented, along with the ] valley in ], the ] in the ], and the ] in ]. Mesopotamia housed historically important cities such as ], ], ], ] and ], as well as major territorial states such as the city of ], the Akkadian kingdoms, the ], and the various ]n empires. Some of the important historical Mesopotamian leaders were ] (king of Ur), ] (who established the Akkadian Empire), ] (who established the Old Babylonian state), ] and ] (who established the Assyrian Empire). | ||

| Scientists analysed ] from the 8,000-year-old remains of early farmers found at an ancient graveyard in ]. They compared the genetic signatures to those of modern populations and found similarities with the DNA of people living in today's ] and ].<ref name=BBC1>{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11729813|title=Migrants from the Near East 'brought farming to Europe'|access-date=10 December 2010|publisher=BBC|date=10 November 2010|archive-date=13 December 2010|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101213144452/http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/science-environment-11729813|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| "Ancient Mesopotamia" begins in the late ], and ends with either the rise of the ] ] in the 6th century BCE or the ] in the 7th century CE. This long period may be divided as follows: | |||

| ===Periodization=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (red dot, {{circa|7500 BC}}), the civilization of Mesopotamia in the 7th–5th millennium BC was centered around the ] in the north, the ] in the northwest, the ] in central Mesopotamia and the ] in the southeast, which later expanded to encompass the whole region.]] | |||

| * Pre-Pottery ]: | |||

| ] with its two major cities ] and ] wedged between ] downstream. The states of ] and ] are upstream.]] | |||

| ** ] (ca. 7000 bce–? bce ) | |||

| * Pre- and protohistory | |||

| * Pottery Neolithic: | |||

| ** ] (10,000–8700 BC) | |||

| ** ] (ca. 6000 bce–? bce), ] (ca. 5700 bce–4900 bce) and ] (ca. 6000 bce–5300 bce) "cultures" | |||

| ** ] (8700–6800 BC) | |||

| * Chalcolithic or ]: | |||

| **] ( |

** ] (7500–5000 BC) | ||

| ** ] (~6000 BC) | |||

| **] (ca. 4400 BCE–3200 BCE) | |||

| ** ] (~5700–4900 BC) | |||

| **Jemdet Nasr period (ca. 3100 BCE–2900 BCE) | |||

| ** ]s (~6000–5300 BC) | |||

| * Early ] | |||

| ** ] (~6500–4000 BC) | |||

| **Early Dynastic ]ian city-states (ca. 2900 BCE–2350 BCE) | |||

| **] ( |

** ] (~4000–3100 BC) | ||

| ** ] (~3100–2900 BC)<ref>{{citation |last=Pollock |first=Susan |title=Ancient Mesopotamia. The Eden that never was |page=2 |year=1999 |series=Case Studies in Early Societies |location=Cambridge |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-57568-3}}.</ref> | |||

| **] ("Sumerian Renaissance" or "Neo-Sumerian Period") (ca. 2119 BCE–2004 BCE) | |||

| * Early Bronze Age | |||

| ** ] (~2900–2350 BC) | |||

| ** ] (~2350–2100 BC) | |||

| ** ] (2112–2004 BC) | |||

| * Middle Bronze Age | * Middle Bronze Age | ||

| **] ( |

** ] (19th to 18th century BC) | ||

| **] (18th to 17th |

** ] (18th to 17th century BC) | ||

| ** ] ({{circa|1620 BC}}) | |||

| * Late Bronze Age | * Late Bronze Age | ||

| **], |

** ] (16th to 11th century BC) | ||

| ** ] ({{circa|1365–1076 BC}}) | |||

| **] (12th to 11th c. BCE) | |||

| ** ] in ], ({{circa|1595–1155 BC}}) | |||

| ** ] (12th to 11th century BC) | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| **] |

** ] (11th to 7th century BC) | ||

| **] (10th to 7th |

** ] (10th to 7th century BC) | ||

| **] (7th to 6th |

** ] (7th to 6th century BC) | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| **] (6th |

** ] (6th century BC) | ||

| ** ], ] (6th to 4th century BC) | |||

| **] Mesopotamia (4th to 1st c. BCE) | |||

| **] Mesopotamia ( |

** ] Mesopotamia (4th to 3rd century BC) | ||

| ** ] (3rd century BC to 3rd century AD) | |||

| ***] (2nd c. CE) | |||

| ** ] (2nd century BC to 3rd century AD) | |||

| **] Mesopotamia (3rd to 7th c. CE) | |||

| ** ] (1st to 2nd century AD) | |||

| **] (7th c.CE) | |||

| ** ] (1st to 2nd century AD) | |||

| ** ] (2nd to 7th century AD), ] (2nd century AD) | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] (3rd to 7th century AD) | |||

| ** ] (mid-7th century AD) | |||

| ==Language and writing== | |||

| Dates are approximate for the second and third millennia BCE; compare ]. | |||

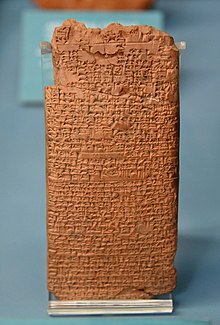

| ] is a ] legal text composed <abbr>c.</abbr> 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organised, and best-preserved legal text from the ]. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of ], purportedly by ], sixth king of the ].]] | |||

| {{Main|Akkadian language|Sumerian language}} | |||

| The earliest language written in Mesopotamia was ], an ] ]. Along with Sumerian, ] were also spoken in early Mesopotamia.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/cultures/mesopotamia_gallery_03.shtml|title=Ancient History in depth: Mesopotamia|publisher=BBC History|access-date=21 July 2017|archive-date=28 June 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170628234445/http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/ancient/cultures/mesopotamia_gallery_03.shtml|url-status=live}}</ref> ]an,<ref>{{cite journal |last=Finkelstein |first=J. J. |year=1955 |title=Subartu and Subarian in Old Babylonian Sources |journal=Journal of Cuneiform Studies |volume=9 |issue=1 |pages=1–7 |doi=10.2307/1359052 |jstor=1359052 |s2cid=163484083}} | |||

| ==Geography== | |||

| </ref> a language of the Zagros possibly related to the ], is attested in personal names, rivers and mountains and in various crafts. ] came to be the dominant language during the ] and the ]n empires, but Sumerian was retained for administrative, religious, literary and scientific purposes. | |||

| {{See|Waterways of Sumer and Akkad|Geography of Iraq|Geography of Syria|Geography of Turkey}} | |||

| Mesopotamia encompasses the combined watersheds of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers, both of which have their headwaters in the mountains of modern Turkey. Both rivers are fed by numerous tributaries, and the entire river system drains a vast mountainous region. Overland routes in Mesopotamia usually follow the Euphrates because the banks of the Tigris are frequently steep and difficult. The climate of the region is semi-arid with a vast desert expanse in the north which gives way to a 6,000 square mile region of marshes, lagoons, mud flats, and reed banks in the south. In the extreme south the Euphrates and the Tigris unite and empty into the Persian Gulf. The greatest concentration of population in this region is between the two rivers, hence the origin of the name. | |||

| Different varieties of Akkadian were used until the end of the ] period. ], which had already become common in Mesopotamia, then became the official provincial administration language of first the ], and then the ]: the official ] is called ]. Akkadian fell into disuse, but both it and Sumerian were still used in temples for some centuries. The last Akkadian texts date from the late 1st century AD. | |||

| The arid environment which ranges from the northern areas of rain fed agriculture, to the south where irrigation of agriculture is essential if a surplus ] (EROEI) is to be obtained. This irrigation is aided by a high water table and by melted snows from the high peaks of the ] and from the ], the source of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, that give the region its name. The usefulness of irrigation depends upon the ability to mobilize sufficient labor for the construction and maintenance of canals, and this, from the earliest period, has assisted the development of urban settlements and centralized systems of political authority. Agriculture throughout the region has been supplemented by nomadic pastoralism, where tent dwelling nomads move herds of sheep and goats (and later camels) from the river pastures in the dry summer months, out into seasonal grazing lands on the desert fringe in the wet winter season. The area is generally lacking in building stone, precious metals and timber, and so historically has relied upon long distance trade of agricultural products to secure these items from outlying areas. In the marshlands to the south of the country, a complex water-borne fishing culture has existed since pre-historic times, and has added to the cultural mix. | |||

| Early in Mesopotamia's history, around the mid-4th millennium BC, ] was invented for the Sumerian language. Cuneiform literally means "wedge-shaped", due to the triangular tip of the stylus used for impressing signs on wet clay. The standardized form of each cuneiform sign appears to have been developed from ]s. The earliest texts, 7 archaic tablets, come from the ], a temple dedicated to the goddess Inanna at Uruk, from a building labeled as Temple C by its excavators. | |||

| Periodic breakdowns in the cultural system have occurred for a number of reasons. The demands for labour has from time to time led to population increases that push the limits of the ecological carrying capacity, and should a period of climatic instability ensue, collapsing central government and declining populations can occur. Alternatively, military vulnerability to invasion from marginal hill tribes or nomadic pastoralists have led to periods of trade collapse and neglect of irrigation systems. Equally, centripetal tendencies amongst city states has meant that central authority over the whole region, when imposed, has tended to be ephemeral, and localism has fragmented power into tribal or smaller regional units.<ref>Thompson, William R. (2004) "Complexity, Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Serial Mesopotamian Fragmentation" (Vol 3, Journal of World Systems Research)</ref> These trends have continued to the present day in Iraq. | |||

| The early ] system of cuneiform script took many years to master. Thus, only a limited number of individuals were hired as ]s to be trained in its use. It was not until the widespread use of a ] script was adopted under Sargon's rule<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Nz8UDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA23|last=Guo|first=Rongxing|title=An Economic Inquiry into the Nonlinear Behaviors of Nations: Dynamic Developments and the Origins of Civilizations|page=23|publisher=Palgrave Macmillan|year=2017|access-date=8 July 2019|quote=It was not until the widespread use of a syllabic script was adopted under Sargon's rule that significant portions of Sumerian population became literate.|isbn=9783319487724|archive-date=14 April 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414130750/https://books.google.com/books?id=Nz8UDgAAQBAJ&pg=PA23|url-status=live}}</ref> that significant portions of the Mesopotamian population became literate. Massive archives of texts were recovered from the archaeological contexts of Old Babylonian scribal schools, through which literacy was disseminated. | |||

| == Language and writing == | |||

| {{Copyedit|section|date=February 2009}} | |||

| Akkadian gradually replaced Sumerian as the spoken language of Mesopotamia somewhere around the turn of the 3rd and the 2nd millennium BC. The exact dating being a matter of debate.<ref name="woods">Woods C. (2006). "Bilingualism, Scribal Learning, and the Death of Sumerian". In S. L. Sanders (ed) ''Margins of Writing, Origins of Culture'': 91–120, Chicago, Illinois . {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130429121058/http://oi.uchicago.edu/pdf/OIS2.pdf|date=29 April 2013}}.</ref> Sumerian continued to be used as a sacred, ceremonial, literary, and scientific language in Mesopotamia until the 1st century AD. | |||

| The earliest known written ] in Mesopotamia was the ], an ] ]. Semitic dialects were also spoken in early Mesopotamia along with Sumerian. Later a ], ], came to be the dominant language, although Sumerian was retained for ], ], ], and ] purposes. Different varieties of Akkadian were used until the end of the Neo-Babylonian period. Then ], which had already become common in Mesopotamia, became the official provincial administration language of the ] ]. Akkadian fell into disuse, but both it and Sumerian were still used in ] for some centuries. | |||

| ===Literature=== | |||

| In Early Mesopotamia (around mid 4th millennium BC) ] was invented. Cuneiform literally means "wedge-shaped", due to the triangular tip of the stylus used for impressing signs on wet clay. The standardized form of each cuneiform sign appear to have been developed from ]. The earliest texts (7 archaic tablets) come from the ]-anna super sacred precinct dedicated to the goddess Inanna at Uruk, Level III, from a building labeled as Temple C by its excavators. | |||

| {{Main|Akkadian literature|Sumerian literature}} | |||

| ], an ] from ancient Mesopotamia, regarded as the earliest surviving notable literature.]] | |||

| Libraries were extant in towns and temples during the Babylonian Empire. An old Sumerian proverb averred that "he who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn." Women as well as men learned to read and write,<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ONkJ_Rj1SS8C&pg=PA75 |page=75 |title=Women, Crime and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: Volume 1: The Ancient Near East |isbn=9780826416285 |last1=Tetlow |first1=Elisabeth Meier |date=28 December 2004 |publisher=A&C Black |access-date=20 June 2015 |archive-date=22 May 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200522152934/https://books.google.com/books?id=ONkJ_Rj1SS8C&pg=PA75 |url-status=live }}</ref> and for the ] Babylonians, this involved knowledge of the extinct Sumerian language, and a complicated and extensive syllabary. | |||

| A considerable amount of Babylonian literature was translated from Sumerian originals, and the language of religion and law long continued to be the old agglutinative language of Sumer. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. The characters of the syllabary were all arranged and named, and elaborate lists were drawn up. | |||

| The early ] system of cuneiform script took many years to master. Thus only a limited number of individuals were hired as ] to be trained in its reading and writing. It was not until the widespread use of a ] script was adopted under Sargon's rule{{Citation needed|date=March 2008}} that significant portions of Mesopotamian population became literate. Massive archives of texts were recovered from the archaeological contexts of Old Babylonian scribal schools, through which literacy was disseminated. | |||

| Many Babylonian literary works are still studied today. One of the most famous of these was the ], in twelve books, translated from the original Sumerian by a certain ], and arranged upon an astronomical principle. Each division contains the story of a single adventure in the career of ]. The whole story is a composite product, although it is probable that some of the stories are artificially attached to the central figure. | |||

| ===Literature and mythology=== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| {{Main|Babylonian literature|Mesopotamian mythology}} | |||

| ==Science and technology== | |||

| In Babylonian times there were libraries in most towns and temples; an old ]ian proverb averred that "he who would excel in the school of the scribes must rise with the dawn." Women as well as men learned to read and write,<ref>Tatlow, Elisabeth Meier ''Women, Crime, and Punishment in Ancient Law and Society: The ancient Near East'' Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd. (31 Mar 2005) ISBN 978-0826416285 p.75 </ref> and for the ] Babylonians, this involved knowledge of the extinct ], and a complicated and extensive syllabary. | |||

| ===Mathematics=== | |||

| A considerable amount of Babylonian literature was translated from Sumerian originals, and the language of religion and law long continued to be the old agglutinative language of Sumer. Vocabularies, grammars, and interlinear translations were compiled for the use of students, as well as commentaries on the older texts and explanations of obscure words and phrases. The characters of the syllabary were all arranged and named, and elaborate lists of them were drawn up. | |||

| {{Main|Babylonian mathematics}} | |||

| ], mathematical, geometric-algebraic, similar to the Euclidean geometry. From ] Iraq. 2003–1595 BC. ].]] | |||

| There are many Babylonian literary works whose titles have come down to us. One of the most famous of these was the ], in twelve books, translated from the original Sumerian by a certain ], and arranged upon an astronomical principle. Each division contains the story of a single adventure in the career of ]. The whole story is a composite product, and it is probable that some of the stories are artificially attached to the central figure. | |||

| Mesopotamian mathematics and science was based on a ] (base 60) ]. This is the source of the 60-minute hour, the 24-hour day, and the 360-] circle. The ] was lunisolar, with three seven-day weeks of a lunar month. This form of mathematics was instrumental in early ]. The Babylonians also had theorems on how to measure the area of several shapes and solids. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which would be correct if {{pi}} were fixed at 3.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/introductiontohi00eves_0 |url-access=registration |page= |title=An Introduction to the History of Mathematics |publisher=Holt, Rinehart and Winston |last1=Eves |first1=Howard |year=1969 |isbn=9780030745508 }}</ref> | |||

| The volume of a cylinder was taken as the product of the area of the base and the height; however, the volume of the ] of a cone or a ] was incorrectly taken as the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. Also, there was a recent discovery in which a tablet used {{pi}} as 25/8 (3.125 instead of 3.14159~). The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about seven modern miles (11 km). This measurement for distances eventually was converted to a time-mile used for measuring the travel of the Sun, therefore, representing time.<ref>{{cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/introductiontohi00eves_0 |url-access=registration |page= |title=An Introduction to the History of Mathematics |publisher=Holt, Rinehart and Winston |last1=Eves |first1=Howard |year=1969 |isbn=9780030745508 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Philosophy=== | |||

| :''Further information: ]'' | |||

| ==== Algebra ==== | |||

| The origins of ] can be traced back to early Mesopotamian ], which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ], in the forms of ], ]s, ], ], ]s, ], ], and ]s. Babylonian ] and ] developed beyond ] observation.<ref>Giorgio Buccellati (1981), "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''101''' (1), p. 35–47.</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Algebra|Square root of 2}} | |||

| The roots of algebra can be traced to the ancient Babylonia<ref>{{cite book |last=Struik |first=Dirk J. |url=https://archive.org/details/concisehistoryof0000stru_m6j1 |title=A Concise History of Mathematics |publisher=Dover Publications |year=1987 |isbn=978-0-486-60255-4 |location=New York |url-access=registration}}</ref> who developed an advanced arithmetical system with which they were able to do calculations in an ] fashion. | |||

| The earliest form of ] was developed by the Babylonians, notably in the rigorous ] nature of their ]. Babylonian ] was ]atic and is comparable to the "ordinary logic" described by ]. Babylonian thought was also based on an ] ] which is compatible with ] axioms.<ref name=Sheila/> Logic was employed to some extent in ] and medicine. | |||

| The ] clay tablet ] ({{circa|1800}}–1600 BC) gives an approximation of {{math|{{sqrt|2}}}} in four ] figures, {{nowrap|1 24 51 10}}, which is accurate to about six ] digits,<ref>Fowler and Robson, p. 368. . {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120813054036/http://it.stlawu.edu/%7Edmelvill/mesomath/tablets/YBC7289.html|date=2012-08-13}}. . {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200712173830/http://www.math.ubc.ca/~cass/Euclid/ybc/ybc.html|date=12 July 2020}}.</ref> and is the closest possible three-place sexagesimal representation of {{math|{{sqrt|2}}}}: | |||

| Babylonian thought had a considerable influence on early ] and ]. In particular, the Babylonian text ''Dialog of Pessimism'' contains similarities to the ]ic thought of the ], the ] doctrine of contrasts, and the ] and dialogs of ], as well as a precursor to the ] ] of ].<ref>Giorgio Buccellati (1981), "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''101''' (1), p. 35–47 43.</ref> The ]n philosopher ] had also studied in Babylonia. | |||

| : <math>1 + \frac{24}{60} + \frac{51}{60^2} + \frac{10}{60^3} = \frac{305470}{216000} = 1.41421\overline{296}.</math> | |||

| ==Science and technology== | |||

| ===Astronomy=== | |||

| {{Main|Babylonian astronomy}} | |||

| {{See|Babylonian astrology|Babylonian calendar}} | |||

| The Babylonian astronomers were very interested in studying the stars and sky, and most could already predict eclipses and solstices. People thought that everything had some purpose in astronomy. Most of these related to religion and omens. Mesopotamian astronomers worked out a 12 month calendar based on the cycles of the moon. They divided the year into two seasons: summer and winter. The origins of astronomy as well as ] date from this time. | |||

| The Babylonians were not interested in exact solutions, but rather approximations, and so they would commonly use ] to approximate intermediate values.<ref name="Boyer Babylon p30">{{Harvnb|Boyer|1991|loc="Mesopotamia" p. 30}}: "Babylonian mathematicians did not hesitate to interpolate by proportional parts to approximate intermediate values. Linear interpolation seems to have been a commonplace procedure in ancient Mesopotamia, and the positional notation lent itself conveniently to the rile of three. a table essential in Babylonian algebra; this subject reached a considerably higher level in Mesopotamia than in Egypt. Many problem texts from the Old Babylonian period show that the solution of the complete three-term quadratic equation afforded the Babylonians no serious difficulty, for flexible algebraic operations had been developed. They could transpose terms in an equations by adding equals to equals, and they could ] both sides by like quantities to remove ] or to eliminate factors. By adding <math>4ab</math> to <math>(a - b)^2</math> they could obtain <math>(a + b)^2</math> for they were familiar with many simple forms of factoring. Egyptian algebra had been much concerned with linear equations, but the Babylonians evidently found these too elementary for much attention. In another problem in an Old Babylonian text we find two simultaneous linear equations in two unknown quantities, called respectively the "first silver ring" and the "second silver ring.""</ref> One of the most famous tablets is the ], created around 1900–1600 BC, which gives a table of ] and represents some of the most advanced mathematics prior to Greek mathematics.<ref>{{cite web|author=Joyce, David E. |year=1995 |title=Plimpton 322 |url=http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/mathhist/plimpnote.html |quote=The clay tablet with the catalog number 322 in the G. A. Plimpton Collection at Columbia University may be the most well known mathematical tablet, certainly the most photographed one, but it deserves even greater renown. It was scribed in the Old Babylonian period between −1900 and −1600 and shows the most advanced mathematics before the development of Greek mathematics. |access-date=3 June 2022 |archive-date=8 March 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110308060531/http://aleph0.clarku.edu/~djoyce/mathhist/plimpnote.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| During the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Babylonian astronomers developed a new approach to astronomy. They began studying ] dealing with the ideal nature of the early ] and began employing an internal ] within their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and the ] and some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first '''scientific revolution'''.<ref name=Brown>D. Brown (2000), ''Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology '', Styx Publications, ISBN 9056930362.</ref> This new approach to astronomy was adopted and further developed in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy. | |||

| ===Astronomy=== | |||

| In ] and ]n times, the astronomical reports were of a thoroughly scientific character; how much earlier their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain. The Babylonian development of methods for predicting the motions of the planets is considered to be a major episode in the ]. | |||

| {{Main|Babylonian astronomy}} | |||

| From ]ian times, temple priesthoods had attempted to associate current events with certain positions of the planets and stars. This continued to Assyrian times, when ] lists were created as a year by year association of events with planetary positions, which, when they have survived to the present day, allow accurate associations of relative with absolute dating for establishing the history of Mesopotamia. | |||

| The Babylonian astronomers were very adept at mathematics and could predict ] and ]. Scholars thought that everything had some purpose in astronomy. Most of these related to religion and omens. Mesopotamian astronomers worked out a 12-month calendar based on the cycles of the moon. They divided the year into two seasons: summer and winter. The origins of astronomy as well as astrology date from this time. | |||

| The only Babylonian astronomer known to have supported a ] model of planetary motion was ] (b. 190 BC).<ref>] (1945). "The History of Ancient Astronomy Problems and Methods", ''Journal of Near Eastern Studies'' '''4''' (1), p. 1–38.</ref><ref>] (1955). "Chaldaean Astronomy of the Last Three Centuries B. C.", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''75''' (3), p. 166–173 .</ref><ref>William P. D. Wightman (1951, 1953), ''The Growth of Scientific Ideas'', Yale University Press p.38.</ref> Seleucus is known from the writings of ]. He supported the heliocentric theory where the ] around its own axis which in turn revolved around the ]. According to ], Seleucus even proved the heliocentric system, but it is not known what arguments he used. | |||

| During the 8th and 7th centuries BC, Babylonian astronomers developed a new approach to astronomy. They began studying philosophy dealing with the ideal nature of the early ] and began employing an internal logic within their predictive planetary systems. This was an important contribution to astronomy and the ] and some scholars have thus referred to this new approach as the first scientific revolution.<ref name=Brown>D. Brown (2000), ''Mesopotamian Planetary Astronomy-Astrology'', Styx Publications, {{ISBN|90-5693-036-2}}.</ref> This new approach to astronomy was adopted and further developed in Greek and Hellenistic astronomy. | |||

| Babylonian astronomy was the basis for much of what was done in ], in classical ], in ], ] and ]n astronomy, in medieval ], and in ]n and ]an astronomy.<ref name=dp1998>{{Harvtxt|Pingree|1998}}</ref> | |||

| In ] and ] times, the astronomical reports were thoroughly scientific. How much earlier their advanced knowledge and methods were developed is uncertain. The Babylonian development of methods for predicting the motions of the planets is considered to be a major episode in the ]. | |||

| ===Mathematics=== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| {{Main|Babylonian mathematics}} | |||

| {{See|Babylonian calendar}} | |||

| The only Greek-Babylonian astronomer known to have supported a ] model of planetary motion was ] (b. 190 BC).<ref>] (1945). "The History of Ancient Astronomy Problems and Methods", ''Journal of Near Eastern Studies'' '''4''' (1), pp. 1–38.</ref><ref>] (1955). "Chaldaean Astronomy of the Last Three Centuries B.C.", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''75''' (3), pp. 166–173 .</ref><ref>William P. D. Wightman (1951, 1953), ''The Growth of Scientific Ideas'', Yale University Press, p. 38.</ref> Seleucus is known from the writings of ]. He supported Aristarchus of Samos' heliocentric theory where the ] around its own axis which in turn revolved around the ]. According to ], Seleucus even proved the heliocentric system, but it is not known what arguments he used, except that he correctly theorized on tides as a result of the Moon's attraction. | |||

| The Mesopotamians used a ] (base 60) ]. This is the source of the current 60-minute hours and 24-hour days, as well as the 360 ] circle. The Sumerian calendar also measured weeks of seven days each. This mathematical knowledge was used in ]. | |||

| Babylonian astronomy served as the basis for much of ], ], Sassanian, ], ]n, ], ]n, and ]an astronomy.<ref name="dp1998">{{Harvtxt|Pingree|1998}}.</ref> | |||

| The Babylonians might have been familiar with the general rules for measuring the areas. They measured the circumference of a circle as three times the diameter and the area as one-twelfth the square of the circumference, which would be correct if <span style="font-family:symbol;">pi</span> were estimated as 3. The volume of a cylinder was taken as the product of the base and the height, however, the volume of the frustum of a cone or a square pyramid was incorrectly taken as the product of the height and half the sum of the bases. Also, there was a recent discovery in which a tablet used <span style="font-family:symbol;">pi</span> as 3 and 1/8 (3.125 for 3.14159~). The Babylonians are also known for the Babylonian mile, which was a measure of distance equal to about seven miles (11 km) today. This measurement for distances eventually was converted to a time-mile used for measuring the travel of the Sun, therefore, representing time.<ref>Eves, Howard ''An Introduction to the History of Mathematics'' Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969 p.31 </ref> | |||

| ===Medicine=== | ===Medicine=== | ||

| ], ].]] | |||

| The oldest Babylonian texts on ] date back to the ] period in the first half of the ]. The most extensive Babylonian medical text, however, is the ''Diagnostic Handbook'' written by the physician Esagil-kin-apli of ],<ref name=Stol-99/> during the reign of the ] Adad-apla-iddina (1069-1046 BC).<ref>Marten Stol (1993), ''Epilepsy in Babylonia'', p. 55, ], ISBN 9072371631.</ref> | |||

| The oldest Babylonian texts on ] date back to the ] period in the first half of the ]. The most extensive Babylonian medical text, however, is the ''Diagnostic Handbook'' written by the ''ummânū'', or chief scholar, ] of ],<ref name=Stol-99/> during the reign of the Babylonian king ] (1069–1046 BC).{{sfn|Stol|1993|p=55}} | |||

| Along with contemporary ], the Babylonians introduced the concepts of ], ], ], and ] |

Along with contemporary ], the Babylonians introduced the concepts of ], ], ], ]s,<ref>{{cite journal |title=The History of the Enema with Some Notes on Related Procedures (Part I) |journal=Bulletin of the History of Medicine |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=77 |date=January 1940 |publisher=] |last1=Friedenwald |first1=Julius |last2=Morrison |first2=Samuel |jstor = 44442727}}</ref> and ]. The ''Diagnostic Handbook'' introduced the methods of ] and ] and the use of ], ], and ] in diagnosis, prognosis and therapy. The text contains a list of medical ]s and often detailed empirical ]s along with logical rules used in combining observed symptoms on the body of a ] with its diagnosis and prognosis.<ref>H. F. J. Horstmanshoff, Marten Stol, Cornelis Tilburg (2004), ''Magic and Rationality in Ancient Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine'', pp. 97–98, ], {{ISBN|90-04-13666-5}}.</ref> | ||

| The symptoms and diseases of a patient were treated through therapeutic means such as ]s, ] |

The symptoms and diseases of a patient were treated through therapeutic means such as ]s, ] and ]. If a patient could not be cured physically, the Babylonian physicians often relied on ] to cleanse the patient from any ]s. Esagil-kin-apli's ''Diagnostic Handbook'' was based on a logical set of ]s and assumptions, including the modern view that through the examination and ] of the symptoms of a patient, it is possible to determine the patient's ], its aetiology, its future development, and the chances of the patient's recovery.<ref name="Stol-99">H. F. J. Horstmanshoff, Marten Stol, Cornelis Tilburg (2004), ''Magic and Rationality in Ancient Near Eastern and Graeco-Roman Medicine'', p. 99, ], {{ISBN|90-04-13666-5}}.</ref> | ||

| Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of ]es and diseases and described their symptoms in his ''Diagnostic Handbook''. These include the symptoms for many varieties of ] and related ]s along with their diagnosis and prognosis.<ref> |

Esagil-kin-apli discovered a variety of ]es and diseases and described their symptoms in his ''Diagnostic Handbook''. These include the symptoms for many varieties of ] and related ]s along with their diagnosis and prognosis.{{sfn|Stol|1993|p=5}} Some treatments used were likely based off the known characteristics of the ingredients used. The others were based on the symbolic qualities.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Teall |first1=Emily |title=Medicine and Doctoring in Ancient Mesopotamia |journal=Grand Valley Journal of History |date=October 2014 |volume=3 |issue=1 |page=3 |url=https://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1056&context=gvjh}}</ref> | ||

| ===Technology=== | ===Technology=== | ||

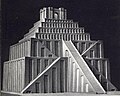

| Mesopotamian people invented many technologies including metal and copper-working, glass and lamp making, textile weaving, ], water storage, and irrigation. They were also one of the first ] societies in the world. They developed from copper, bronze, and gold on to iron. Palaces were decorated with hundreds of kilograms of these very expensive metals. Also, copper, bronze, and iron were used for armor as well as for different weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, and ]. | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| {{Copyedit|date=December 2008}} | |||

| Mesopotamian people invented many technologies including metal and copper-working, glass and lamp making, textile weaving, flood control, water storage, and irrigation. | |||

| According to a recent hypothesis, the ] may have been used by Sennacherib, King of Assyria, for the water systems at the ] and ] in the 7th century BC, although mainstream scholarship holds it to be a ] invention of later times.<ref>Stephanie Dalley and ] (January 2003). "Sennacherib, Archimedes, and the Water Screw: The Context of Invention in the Ancient World", ''Technology and Culture'' '''44''' (1).</ref> Later, during the Parthian or Sasanian periods, the ], which may have been the world's first battery, was created in Mesopotamia.<ref name="BBC2">{{Citation |last=Twist |first=Jo |title=Open media to connect communities |date=20 November 2005 |work=BBC News |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4450052.stm |access-date=6 August 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190517132329/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4450052.stm |archive-date=17 May 2019 |url-status=live}}.</ref> | |||

| They were also one of the first ] people in the world. Early on they used copper, bronze and gold, and later they used iron. Palaces were decorated with hundreds of kilograms of these very expensive metals. Also, copper, bronze, and iron were used for armor as well as for different weapons such as swords, daggers, spears, and ]. | |||

| ==Religion and philosophy== | |||

| The earliest type of pump was the ], first used by ], King of ], for the water systems at the ] and ] in the 7th century BC, and later described in more detail by ] in the 3rd century BC.<ref>Stephanie Dalley and John Peter Oleson (January 2003). "Sennacherib, Archimedes, and the Water Screw: The Context of Invention in the Ancient World", ''Technology and Culture'' '''44''' (1).</ref> Later during the ]n or ] periods, the ], which may have been the first batteries, were created in Mesopotamia.<ref name=BBC>{{cite web |url=http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4450052.stm |last=Twist |first=Jo |title=Open media to connect communities |publisher=BBC News |date=20 November 2005 |accessdate=2007-08-06}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Ancient Mesopotamian religion}} | |||

| ], ], around 1800 BC]] | |||

| The ] was the first recorded. Mesopotamians believed that the world was a flat disc,<ref>{{cite book |last=Lambert |first=W. G. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dTLWQddp8zwC&pg=PA111 |title=Ancient Mesopotamian Religion and Mythology: Selected Essays |publisher=Mohr Siebeck |year=2016 |isbn=978-3161536748 |page=111 |access-date=8 July 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220501165046/https://books.google.com/books?id=dTLWQddp8zwC |archive-date=1 May 2022 |url-status=live |department=The Cosmology of Sumer & Babylon}}</ref> surrounded by a huge, holed space, and above that, ]. They believed that water was everywhere, the top, bottom and sides, and that the ] was born from this enormous sea. Mesopotamian religion was ]. Although the ]s described above were held in common among Mesopotamians, there were regional variations. The Sumerian word for universe is '''an-ki''', which refers to the god ] and the goddess ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hetherington |first1=Norriss S. |title=Encyclopedia of Cosmology (Routledge Revivals) : Historical, Philosophical, and Scientific Foundations of Modern Cosmology. |date=2014 |publisher=Taylor and Francis |location=Hoboken |isbn=9781317677666 |page=399}}</ref><!--stating that the word "an-ki" for "]" derives from the two god words for ] and ] is debatable. There was also a god called "]".--> Their son was Enlil, the air god. They believed that Enlil was the most powerful god. He was the chief god of the ]. | |||

| == Religion == | |||

| <!-- | |||

| Image with unknown copyright status removed: ] --> | |||

| ===Philosophy=== | |||

| Mesopotamian ] was the first to be recorded. Mesopotamians believed that the world was a flat disc{{Citation needed|date=June 2009}}, surrounded by a huge, holed space, and above that, ]. They also believed that water was everywhere, the top, bottom and sides, and that the ] was born from this enormous sea. In addition, Mesopotamian religion was ]. | |||

| The numerous civilizations of the area influenced the ], especially the ]. Its cultural values and literary influence are especially evident in the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bertman |first1=Stephen |title=Handbook to life in ancient Mesopotamia |date=2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-518364-1 |edition=Paperback |location=Oxford , England |page=312}}</ref> | |||

| Although the ]s described above were held in common among Mesopotamians, there were also regional variations. The Sumerian word for universe is an-ki, which refers to the god An and the goddess Ki. Their son was Enlil, the air god. They believed that Enlil was the most powerful god. He was the chief god of the ], as the Greeks had ] and the Romans had ]. The Sumerians also posed ] questions, such as: Who are we?, Where are we?, How did we get here?. They attributed answers to these questions to explanations provided by their gods. | |||

| ] believes that the origins of ] can be traced back to early Mesopotamian ], which embodied certain philosophies of life, particularly ], in the forms of ], ]s, ], ], ]s, ], ] works, and ]s. Babylonian ] and ] developed beyond ] observation.<ref>Giorgio Buccellati (1981), "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''101''' (1), pp. 35–47.</ref> | |||

| == Holidays, Feasts, and Festivals == | |||

| Babylonian thought was also based on an ] ] which is compatible with ] axioms.<ref name=Sheila/> Logic was employed to some extent in ] and medicine. | |||

| Ancient Mesopotamians had ceremonies each month. The theme of the rituals and festivals for each month is determined by six important factors: | |||

| Babylonian thought had a considerable influence on early ] and ]. In particular, the Babylonian text '']'' contains similarities to the agonistic thought of the ]s, the ] doctrine of ], and the dialogs of ], as well as a precursor to the ].<ref>Giorgio Buccellati (1981), "Wisdom and Not: The Case of Mesopotamia", ''Journal of the American Oriental Society'' '''101''' (1), pp. 35–47 43.</ref> The ] philosopher ] was influenced by Babylonian cosmological ideas. | |||

| # The phase of the ]; <br | |||

| />waxing Moon = abundance and growth; <br | |||

| />waning Moon = decline, conservation, and festivals of the Underworld; | |||

| # the phase of the annual agricultural cycle; | |||

| # ] and ] of the solar year; | |||

| # the mythos of the City and its divine Patrons; | |||

| # the success of the reigning Monarch; | |||

| # commemoration of specific historical events (founding, military victories, temple holidays, etc.) | |||

| ==Culture== | |||

| === Primary gods and goddesses === | |||

| ] (1186–1172 BC) presents his daughter to the goddess ]. The crescent moon represents the god ], the sun the ] and the star the goddess ].{{sfn|Black|Green|1992|pp=156, 169–170}}{{sfn|Liungman|2004|page=228}}]] | |||

| *] was the Sumerian god of the sky. He was married to Ki, but in some other Mesopotamian religions he has a wife called Uraš. Though he was considered the most important god in the pantheon, he took a mostly passive role in epics, allowing Enlil to claim the position as most powerful god. | |||

| *] was initially the most powerful god in Mesopotamian religion. His wife was ], and his children were ] (sometimes), ] – ], ], ], ], ] (sometimes), ], ], ], ] and ]. His position at the top of the pantheon was later usurped by Marduk and then by Ashur. | |||

| *] (Ea) god of ]. He was the god of rain. | |||

| *] was the principal god of ]. When Babylon rose to power, the mythologies raised Marduk from his original position as an agricultural god to the principal god in the pantheon. | |||

| *] was god of the Assyrian empire and likewise when the ] rose to power their myths raised Ashur to a position of importance. | |||

| *] or ] (in Sumerian), ] (in Akkadian) was the sun god and god of justice. | |||

| ===Festivals=== | |||

| *] was goddess of the Netherworld. | |||

| Ancient Mesopotamians had ceremonies each month. The theme of the rituals and festivals for each month was determined by at least six important factors: | |||

| *] was the Mesopotamian god of writing. He was very wise, and was praised for his writing ability. In some places he was believed to be in control of heaven and earth. His importance was increased considerably in the later periods. | |||

| *] was the Sumerian god of war. He was also the god of heroes. | |||

| *] (or ]) was the god of storms. | |||

| *] was probably the god of drought. He is often mentioned in conjunction with ] and ] in laying waste to the land. | |||

| *] was probably a plague god. He was also spouse of ]. | |||

| *], also known as ], was an evil god, who stole the tablets of ]’s destiny, and is killed because of this. He also brought diseases which had no known cure. | |||

| # The ] (a waxing moon meant abundance and growth, while a waning moon was associated with decline, conservation, and festivals of the Underworld) | |||

| === Burials === | |||

| # The phase of the annual agricultural cycle | |||

| {{Unreferenced section|date=October 2007}} | |||

| # ] and ] | |||

| Hundreds of ] have been excavated in parts of Mesopotamia, revealing information about Mesopotamian ] habits. In the city of ], most people were buried in family graves under their houses (as in ]), along with some possessions. A few have been found wrapped in mats and ]. Deceased children were put in big "jars" which were placed in the family ]. Other remains have been found buried in common city ]s. 17 graves have been found with very precious objects in them <!-- such as? -->; it is assumed <!-- by whom ? -->that these were royal graves. | |||

| # The local mythos and its divine Patrons | |||

| # The success of the reigning Monarch | |||

| # The ], or ] Festival (first full moon after spring equinox) | |||

| # Commemoration of specific historical events (founding, military victories, temple holidays, etc.) | |||

| == |

===Music=== | ||

| {{Main|Music of Mesopotamia}} | |||

| === Music, songs and instruments === | |||

| ] from the ]. {{circa|2500 BC}}. ]]] | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| Some songs were written for the gods but many were written to describe important events. Although music and songs amused ], they were also enjoyed by ordinary people who liked to sing and dance in their homes or in the ]s. |

Some songs were written for the gods but many were written to describe important events. Although music and songs amused ], they were also enjoyed by ordinary people who liked to sing and dance in their homes or in the ]s. | ||

| Songs were sung to children who passed them on to their children. Thus songs were passed on through many ]s as an oral tradition until writing was more universal. These songs provided a means of passing on through the ] highly important information about historical events. | |||

| The ] (Arabic:العود) is a small, stringed musical instrument. The oldest pictorial record of the Oud dates back to the ] period in Southern Mesopotamia over 5000 years ago. It is on a ] currently housed at the British Museum and acquired by Dr. Dominique Collon. The ] depicts a female crouching with her instruments upon a ], playing ]. This instrument appears hundreds of times throughout Mesopotamian history and again in ancient ] from the 18th ] onwards in long- and short-neck varieties. | |||

| ===Games=== | |||

| The oud is regarded as a ] to the ]an ]. Its name is derived from the Arabic word العود al-‘ūd 'the wood', which is probably the name of the tree from which the oud was made. (The Arabic name, with the definite article, is the source of the word 'lute'.) | |||

| ] | |||

| ] was popular among Assyrian kings. ] and ] feature frequently in art, and some form of ] was probably popular, with men sitting on the shoulders of other men rather than on horses.<ref>{{Citation |author=Nemet-Nejat |first=Karen Rhea |title=Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia |year=1998}}.</ref> | |||

| They also played a board game similar to ] and ], now known as the "]". | |||

| === Games === | |||

| ] was popular among Assyrian kings. ] and ] feature frequently in art, and some form of ] was probably popular, with men sitting on the shoulders of other men rather than on horses.<ref>{{cite book|author=Karen Rhea Nemet-Nejat|title=Daily Life in Ancient Mesopotamia|date=1998}}</ref> They also played majore, a game similar to the sport rugby, but played with a ball made of wood. They also played a board game similar to ] and ], now known as the "Royal Game of Ma-asesblu." | |||

| === |

===Family life=== | ||

| ] | ]]] | ||

| Mesopotamia across its history became more and more a ], in which the men were far more powerful than the women. Thorkild Jacobsen, |

Mesopotamia, as shown by successive law codes, those of ], ] and ], across its history became more and more a ], one in which the men were far more powerful than the women. For example, during the earliest Sumerian period, the ''"en"'', or high priest of male gods was originally a woman, that of female goddesses. ], as well as others, have suggested that early Mesopotamian society was ruled by a "council of elders" in which men and women were equally represented, but that over time, as the status of women fell, that of men increased.<ref>{{Citation |author=Harris |first=Rivkah |title=Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia |year=2000}}.</ref> | ||

| As for schooling, only royal offspring and sons of the rich and professionals, such as scribes, physicians, temple administrators, went to school. Most boys were taught their father's trade or were apprenticed out to learn a trade.<ref>{{Citation |author=Harris |first=Rivkah |title=Gender and Aging in Mesopotamia |year=2000}}.</ref> Girls had to stay home with their mothers to learn ] and ], and to look after the younger children. Some children would help with crushing grain or cleaning birds. Unusually for that time in history, women in Mesopotamia had ]. They could own ] and, if they had good reason, get a ].<ref name="Kramer1963">{{cite book |last1=Kramer |first1=Samuel Noah |url=https://archive.org/details/sumerianstheirhi00samu |title=The Sumerians: Their History, Culture, and Character |date=1963 |publisher=The University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-45238-8 |url-access=registration}}</ref>{{rp|78–79}} | |||

| ==Economy== | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| ] developed the first ], while the Babylonians developed the earliest system of ], which was comparable to modern ], but with a more "anything goes" approach.<ref name=Sheila>Sheila C. Dow (2005), "Axioms and Babylonian thought: a reply", ''Journal of Post Keynesian Economics'' '''27''' (3), p. 385–391.</ref> | |||

| == |

===Burials=== | ||

| Hundreds of ] have been excavated in parts of Mesopotamia, revealing information about Mesopotamian ] habits. In the city of ], most people were buried in family graves under their houses, along with some possessions. A few have been found wrapped in mats and ]. Deceased children were put in big "jars" which were placed in the family ]. Other remains have been found buried in common city ]s. 17 graves have been found with very precious objects in them. It is assumed that these were royal graves. Rich of various periods, have been discovered to have sought burial in Bahrein, identified with Sumerian Dilmun.<ref>Bibby, Geoffrey and Phillips, Carl (1996), "Looking for Dilmun" (Interlink Pub Group).</ref> | |||

| The geography of Mesopotamia is such that agriculture is possible only with irrigation and good drainage, a fact which has had a profound effect on the evolution of Mesopotamian civilization. The need for irrigation led the Sumerians and later the Akkadians to build their cities along the Tigris and Euphrates and the branches of these rivers. Some major cities, such as Ur and Uruk, took root on tributaries of the Euphrates, while others, notably Lagash, were built on branches of the Tigris. The rivers provided the further benefits of fish (used both for food and fertilizer), reeds and clay (for building materials). | |||

| == Economy == | |||

| With irrigation the ] in Mesopotamia was quite rich with the Tigris and Euphrates River valleys forming the northeastern portion of the ], which also included the ] valley & that of the ]. Although land nearer to the rivers was ] and good for ], portions of land farther from the water were dry and largely uninhabitable. This is why the development of ] was very important for ]s of Mesopotamia. Other Mesopotamian ]s include the control of water by ]s and the use of ]s. | |||

| ].]] | |||

| Early settlers of fertile land in Mesopotamia used ]en ]s to soften the ] before planting crops such as ], ]s, ]s, ]s and ]s. Mesopotamian settlers were some of the first people to make ] and ]. | |||

| Sumerian temples functioned as banks and developed the first large-scale ]. The Babylonians developed the earliest system of commercial ]. It was comparable in some ways to modern ], but with a more "anything goes" approach.<ref name=Sheila>{{cite journal |url= https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01603477.2005.11051453 |doi= 10.1080/01603477.2005.11051453 |title= Axioms and Babylonian thought: A reply |journal= Journal of Post Keynesian Economics |volume= 27 |issue= 3 |pages= 385–391 |date= April 2005 |last1= Dow |first1= Sheila C. |s2cid= 153637070 |access-date= 7 December 2019 |archive-date= 3 August 2020 |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20200803222653/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01603477.2005.11051453 |url-status= live }}</ref> | |||

| Although the rivers sustained life, they also destroyed it by frequent floods that ravaged entire cities. The unpredictable Mesopotamian weather was often hard on farmers; crops were often ruined so backup sources of food such as cows and lambs were also kept. | |||

| As a result of the skill involved in farming in the Mesopotamian, farmers did not depend on ] to complete farm work for them, with some exceptions. There were too many risks involved to make slavery practical (i.e. the escape/] of the ]). | |||

| == |

=== Agriculture === | ||

| {{Main|Agriculture in Mesopotamia}} | |||

| The geography of Mesopotamia had a profound impact on the political development of the region. Among the rivers and streams, the Sumerian people built the first cities along with irrigation canals which were separated by vast stretchs of open desert or swamp where nomadic tribes roamed. Communication among the isolated cities was difficult and at times dangerous. Thus each Sumerian city became a ], independent of the others and protective of its independence. At times one city would try to conquer and unify the region, but such efforts were resisted and failed for centuries. As a result, the political history of Sumer is one of almost constant warfare. Eventually Sumer was unified by ], but the unification was tenuous and failed to last as the Akkadians conquered Sumeria in 2331B.C. only a generation later. | |||

| Irrigated agriculture spread southwards from the Zagros foothills with the Samara and Hadji Muhammed culture, from about 5,000 BC.<ref name="Cengage Learning, 1 Jan 2010">{{cite book |author1=Bulliet |first=Richard |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jvsVSqhw-FAC&pg=PA29 |title=The Earth and Its Peoples: A Global History |author2=Crossley |first2=Pamela Kyle |author3=Headrick |first3=Daniel |author4=Hirsch |first4=Steven |author5=Johnson |first5=Lyman |author6=Northup |first6=David |date=1 January 2010 |publisher=Cengage Learning |isbn=978-0-538-74438-6 |access-date=30 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414161613/https://books.google.com/books?id=jvsVSqhw-FAC&pg=PA29 |archive-date=14 April 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| The Akkadian Empire was the first successful empire to last beyond a generation and see the peaceful succession of kings. The empire was relatively short lived, as the Babylonians conquered them within only a few generations. | |||

| === Kings === | |||

| {{Expand section|date=December 2009}} | |||

| {{See|Sumerian king list|List of Kings of Babylon|Kings of Assyria}} | |||

| The Mesopotamians believed their kings and queens were descended from the City of ]s, but, unlike the ], they never believed their kings were real gods.<ref name="Robert Dalling 2004">{{cite book|author=Robert Dalling|title=The Story of Us Humans, from Atoms to Today's Civilization|date=2004}}</ref> Most kings named themselves “king of the universe” or “great king”. Another common name was “]”, as kings had to look after their people. | |||

| In the early period down to ] temples owned up to one third of the available land, declining over time as royal and other private holdings increased in frequency. The word ] was used to describe the official who organized the work of all facets of temple agriculture. ]s are known to have worked most frequently within agriculture, especially in the grounds of temples or palaces.<ref name="H. W. F. Saggs">{{Cite book |author=Saggs |first=H. W. F. – Professor Emeritus of Semitic Languages at University College, Cardiff, Wales |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BPdLxEyHci0C&pg=PA58 |title=Babylonians |publisher=University of California Press |year=2000 |isbn=978-0-520-20222-1 |access-date=29 May 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210414130752/https://books.google.com/books?id=BPdLxEyHci0C&pg=PA58 |archive-date=14 April 2021 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Notable Mesopotamian kings include: | |||

| The geography of southern Mesopotamia is such that agriculture is possible only with irrigation and with good drainage, a fact which had a profound effect on the evolution of early Mesopotamian civilization. The need for irrigation led the Sumerians, and later the Akkadians, to build their cities along the Tigris and Euphrates and the branches of these rivers. Major cities, such as Ur and Uruk, took root on tributaries of the Euphrates, while others, notably Lagash, were built on branches of the Tigris. The rivers provided the further benefits of fish, used both for food and fertilizer, reeds, and clay, for building materials. With irrigation, the ] in Mesopotamia was comparable to that of the Canadian prairies.<ref>Roux, Georges, (1993) "Ancient Iraq" (Penguin).</ref> | |||

| ] of ] who founded the first (short-lived) empire. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] of ] who conquered all of Mesopotamia and created the first empire that outlived its founder. | |||

| The Tigris and Euphrates River valleys form the northeastern portion of the ], which also included the Jordan River valley and that of the Nile. Although land nearer to the rivers was fertile and good for ], portions of land farther from the water were dry and largely uninhabitable. Thus the development of ] became very important for ]s of Mesopotamia. Other Mesopotamian ]s include the control of water by ]s and the use of aqueducts. Early settlers of fertile land in Mesopotamia used wooden ]s to soften the ] before planting crops such as ], ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s. | |||

| Mesopotamian settlers were some of the first people to make ] and ]. As a result of the skill involved in farming in the Mesopotamian region, farmers did not generally depend on ] to complete farm work for them, but there were some exceptions. There were too many risks involved to make slavery practical, i.e. the escape/mutiny of the slaves. Although the rivers sustained life, they also destroyed it by frequent floods that ravaged entire cities. The unpredictable Mesopotamian weather was often hard on farmers. Crops were often ruined, so backup sources of food such as cows and lambs were kept. Over time the southernmost parts of Sumerian Mesopotamia suffered from increased salinity of the soils, leading to a slow urban decline and a centring of power in Akkad, further north. | |||

| ] founded the first ]ian empire. | |||

| === Trade === | |||

| ] founded the neo-] empire. | |||

| Mesopotamian trade with the ] flourished as early as the third millennium BC.<ref>{{cite book | |||

| | last1 = Wheeler | |||

| | first1 = Mortimer | |||

| | author-link1 = Mortimer Wheeler | |||

| | year = 1953 | |||

| | title = The Indus Civilization | |||

| | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=9cs7AAAAIAAJ | |||

| | series = Cambridge history of India: Supplementary volume | |||

| | edition = 3 | |||

| | location = Cambridge | |||

| | publisher = Cambridge University Press | |||

| | publication-date = 1968 | |||

| | page = 111 | |||

| | isbn = 9780521069588 | |||

| | access-date = 10 April 2021 | |||