| Revision as of 13:59, 3 January 2010 editTXiKiBoT (talk | contribs)567,654 editsm robot Adding: af:Minotourus← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 18:44, 17 January 2025 edit undoPrimeBOT (talk | contribs)Bots2,079,569 editsm →Etymology: Task 24: template replacement following a TFDTag: AWB | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Creature of Greek mythology}} | |||

| {{This|the mythological monster}} | |||

| {{about|the mythological monster}} | |||

| {{Infobox mythical creature | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| |Creature_Name = Minotaur | |||

| {{Infobox deity | |||

| |Image_Name = Minotauros Myron NAMA 1664 n1.jpg | |||

| | type = Greek | |||

| |Image_Caption = Minotaur bust, (]) | |||

| | name = Minotaur | |||

| |AKA = Minotaurus | |||

| | image = Tondo Minotaur London E4 MAN.jpg | |||

| |Grouping = ] | |||

| | alt = | |||

| |Mythology = ] | |||

| | caption = The Minotaur on an Attic ''] ]'' from {{circa|515}} BC with a ].{{Efn|In {{langx|grc|ὁ παῖς καλός}}, ''ho pais kalos'' meaning "the boy is beautiful", a common ] formula found on Attic pottery}} | |||

| |Region = ] | |||

| | |

| abode = ], ] | ||

| | parents = ] and ] | |||

| | siblings = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] | |||

| | other_names = Asterion | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| In ], the '''Minotaur'''{{Efn|{{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|aɪ|n|ə|t|ɔːr|,_|ˈ|m|ɪ|n|ə|t|ɔːr|}} {{respell|MY|nə|tor|,_|MIN|ə|tor}},<ref name= "collins_english">{{cite web |url= http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/minotaur |title= English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur |publisher=Collins |access-date= 20 July 2013}}</ref> {{IPAc-en |US|ˈ|m|ɪ|n|ə|t|ɑːr|,_|-|oʊ|-}} {{respell|MIN|ə|tar|,_-|oh|-}};<ref name= "books.google.com">{{Citation | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=6Lc9AAAAYAAJ&pg=PA79 | title = Pronunciation: Designed for Use in Schools and Colleges and Adapted to the Wants of All Persons who Wish to Pronounce According to the Highest Standards | first = John Hendricks | last = Bechtel | publisher = Penn Publishing Co | year = 1908}}.</ref><ref>{{Citation | title = The Book of Literature: A Comprehensive Anthology of the Best Literature, Ancient, Mediæval and Modern, with Biographical and Explanatory Notes | volume = 33 | first1 = Richard | last1 = Garnett | first2 = Léon | last2 = Vallée | first3 = Alois | last3 = Brandl | publisher = Grolier society | year = 1923 | url = https://books.google.com/books?id=-mMUAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA645}}.</ref>}} ({{langx|grc|Μινώταυρος}}, ''Mīnṓtauros''), also known as '''Asterion''', is a mythical creature portrayed during ] with the head and tail of a ] and the body of a man<ref name=Kern-2000>{{cite book |last=Kern |first=Hermann |date=2000 |title=Through the Labyrinth |location=Munich, London, New York |publisher=Prestel |isbn=379132144-7}}</ref>{{rp|style=ama|p= 34}} or, as described by Roman poet ], a being "part man and part bull".{{efn| | |||

| {{Greek myth}} | |||

| According to ]: | |||

| In ], the '''Minotaur''' (]: {{polytonic|Μῑνώταυρος}}, {{lang-la|Minotaurus}}, ] ''Θevrumineś''), as the ] imagined him, was a creature with the head of a bull on the body of a man<ref> at dictionary.reference.com</ref> or, as described by ], "part man and part ]."<ref>''semibovumque virem; semivirumque bovem'', according to ], '']'' 2.24, one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo. (noted by J. S. Rusten, "Ovid, Empedocles and the Minotaur" ''The American Journal of Philology'' '''103'''.3 (Autumn 1982, pp. 332-333) p. 332.</ref> He dwelt at the center of the ] ], which was an elaborate ]-like construction<ref>Labyrinth patterns as painted or inscribed do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center, where, with a single turn, the alternate path leads out again. See Kern, ''Through the Labyrinth'', Prestel, 2000, Chapter 1, and Doob, ''The Idea of the Labyrinth'', Cornell University Press, 1990, Chapter 2.</ref> built for ] of ] and designed by the architect ] and his son ] who were ordered to build it to hold the Minotaur. <!-- (this is discussed more critically below) The historical site of ], with over 1300 maze like compartments<ref>C. Michael Hogan. 2007. </ref> is identified as the site of the labyrinth.--> The Minotaur was eventually killed by ], the son of ]. | |||

| : {{lang|la|semibovemque virum semivirumque bovem}},<ref> | |||

| {{cite book |author=] |title=] |at=2.24}}</ref> one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by ].<ref>] cited by {{cite journal |first=J.S. |last=Rusten |date=Autumn 1982 |title=Ovid, Empedocles, and the Minotaur |journal=The American Journal of Philology |volume=103 |issue=3 |pages=332–333, esp. 332|doi=10.2307/294479 |jstor=294479 }}</ref> | |||

| }} He dwelt at the center of the ], which was an elaborate ]-like construction{{efn| | |||

| In a counter-intuitive cultural development going back at least to Cretan coins of the 4th century BCE, many visual patterns representing the ] do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center.{{refn| | |||

| Kern (2000);<ref name=Kern-2000/>{{rp|style=ama|at=Chapter 1}} | |||

| Doob (1990)<ref name=Doob-1990>{{cite book |author=Doob, Penelope Reed |date=April 1990 |title=The Idea of the Labyrinth: From Classical antiquity through the Middle Ages |place=Ithaca, NY |publisher=Cornell University Press |isbn=978-080142393-2}}</ref>{{rp|style=ama|at=Chapter 2}} | |||

| }}}} designed by the architect ] and his son ], upon command of King ] of ]. According to tradition, every nine years the people of ] were compelled by King Minos to choose ] (seven men and seven women) to be offered as sacrificial victims to the Minotaur in retribution for the death of Minos's son ]. The Minotaur was eventually slain by the Athenian hero ], who managed to navigate the labyrinth with the help of a thread offered to him by the King's daughter, ]. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| The term Minotaur derives from the ] ''Μῑνώταυρος'', ] compounding the name ''Μίνως'' (]) and the noun ''ταύρος'' "bull", translating as "''(the) Bull of Minos''". In Crete, the Minotaur was known by its proper name, ],<ref>Pausanias, Description of Greece 2. 31. 1</ref> a name shared with Minos' foster-father.<ref>The Hesiodic '']'', says of Zeus' establishment of Europa in Crete: "...he made her live with Asterion the king of the Cretans. There she conceived and bore three sons, Minos, Sarpedon and Rhadamanthys."</ref> | |||

| The word "Minotaur" derives from the ] {{lang|grc|Μινώταυρος}} {{IPA|el|miːnɔ̌ːtau̯ros|}} a ] of the name {{lang|grc|Μίνως}} (]) and the noun {{wikt-lang|grc|ταῦρος}} ''tauros'' meaning {{gloss|bull}},<ref name="collins_american" /> thus it is translated as the {{gloss|Bull of Minos}}. In Crete, the Minotaur was known by the name Asterion ({{lang|grc|Ἀστερίων}}) or Asterius ({{lang|grc|Ἀστέριος}}),<ref>{{cite book |author=Pausanias |author-link=Pausanias (geographer) |title=Description of Greece |at=}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Apollodorus |title=Library |at=}}</ref> a name shared with Minos's foster-father.{{efn|Hesiod says of Zeus's establishment of Europa in Crete: | |||

| : "... he made her live with ] the king of the Cretans. There she conceived and bore three sons, ], ], and ]."<ref name=Hesiod-fr140>{{cite book |author=] |title=] |at=fr. 140}}</ref>}} | |||

| "Minotaur" was originally a proper noun in reference to this mythic figure. That is, there was only the one Minotaur. In contrast, the use of "minotaur" as a common noun to refer to members of a generic "species" of bull-headed creatures developed much later, in 20th century fantasy genre fiction. | |||

| The Minotaur was called ''{{lang|la|{{linktext|Minotaurus}}}}'' {{IPA|la|miːnoːˈtau̯rʊs|}} in ] and {{lang|ett|Θevrumineš}} in ].<ref>{{cite journal |last=de Simone |first=C. |title=Zu einem Beitrag über etruskisch ''θevru mines'' |journal=Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung |volume=84 |year=1970 |pages=221–223}}</ref> English pronunciation of the word "Minotaur" is varied; the following can be found in dictionaries: {{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|aɪ|n|ə|t|ɔːr|,_|-|n|oʊ|-}} {{respell|MY|nə|tor|,_-|noh|-}},<ref name="collins_english" /> {{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|ɪ|n|ə|t|ɑːr|,_|ˈ|m|ɪ|n|oʊ|-}} {{respell|MIN|ə|tar|,_|MIN|oh|-}},<ref name="books.google.com" /> {{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|ɪ|n|ə|t|ɔːr|,_|ˈ|m|ɪ|n|oʊ|-}} {{respell|MIN|ə|tor|,_|MIN|oh|-}}.<ref name="collins_american">{{cite dictionary |title=Minotaur |dictionary=American English Dictionary |publisher=Collins |url= http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/american/minotaur |access-date=20 July 2013}}</ref> | |||

| ==Birth and appearance== | |||

| ]. Bronze by ] (])]] | |||

| After he ascended the throne of Crete, Minos struggled with his brothers for the right to rule. Minos prayed to ] to send him a snow-white bull, as a sign of approval. He was to sacrifice the bull in honor of Poseidon but decided to keep it instead because of its beauty. To punish Minos, Poseidon caused ], Minos' wife, to fall madly in love with the bull from the sea, the ].<ref>In Greek mythology, the Cretan Bull was equally the bull that carried away Europa.</ref> She had Daedalus, the famous architect, make a wooden cow for her. Pasiphaë climbed into the decoy in order to ] with the white bull. The offspring of their coupling was a monster called the Minotaur. Pasiphaë nursed him in his infancy, but he grew and became ferocious. Minos, after getting advice from the Oracle at ], had Daedalus construct a gigantic labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos' palace in Knossos. | |||

| ==Creation myth== | |||

| Nowhere has the essence of the myth been expressed more succinctly than in the '']'' attributed to ], where Pasiphaë's daughter complains of the curse of her unrequited love: "the bull's form disguised the god, Pasiphaë, my mother, a victim of the deluded bull, brought forth in travail her reproach and burden."<ref>Walter Burkert notes the fragment of ]' ''The Cretans'' (C. Austin's frs. 78-82) as the "authoritative version" for the Hellenes.</ref> Literalist and prurient readings that emphasize the machinery of actual copulation may, perhaps intentionally, obscure the ] of the god in bull form, a Minoan mythos alien to the Greeks.<ref>See R.F. Willetts, ''Cretan Cults and Festivals'' (London, 1962); Pasiphaë's union with the bull has been recognized as a mystical union for over a century: F. B. Jevons, )"Report on Greek Mythology" ''Folklore'' '''2'''.2 (June 1891:220-241) p. 226) notes of Europa and Pasiphaë, "The kernel of both myths is the union of the moon-spirit (in human shape) with a bull; both myths, then, have to do with a sacred marriage."</ref> | |||

| ] and baby Minotaur, ] red-figure ] found at Etruscan ]. Italy. Currently at the ], Paris]] | |||

| After ascending the throne of the island of Crete, ] competed with his brothers as ruler. Minos prayed to the sea god ] to send him a ] as a sign of the god's favor. Minos was to sacrifice the bull to honor Poseidon, but owing to the bull's beauty he decided instead to keep him. Minos believed that the god would accept a substitute sacrifice. To punish Minos, Poseidon arranged with Aphrodite for Minos's wife, ], to fall in love with the bull. Pasiphaë had the ], ], fashion for her a hollow wooden cow, which she climbed into to let the bull mate with her. She then fell pregnant and bore Asterius, the Minotaur, making him a grandchild of ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Apollodorus, Library, book 3, chapter 1 |url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0022:text=Library:book=3:chapter=1&highlight=minotaur |access-date=18 May 2023 |website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref> Pasiphaë nursed the Minotaur but he grew in size and became ferocious. As the unnatural offspring of a woman and a beast, the Minotaur had no natural source of nourishment and thus devoured humans for sustenance.{{Citation needed|date=October 2023}} Minos, following advice from the oracle at ], had Daedalus construct a gigantic ] to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos's palace in ].<ref name="EB19112">{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Minotaur|volume=18|page=555}}</ref> | |||

| ==Appearance== | |||

| The Minotaur is commonly represented in Classical art with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. One of the figurations assumed by the ] ] in wooing ] is as a man with the head of a bull, according to ]' ''Trachiniai''. | |||

| The Minotaur is commonly represented in Classical art with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. According to ]'s {{lang|grc-Latn|]}}, when the river spirit ] seduced ], one of the guises he assumed was a man with the head of a bull. From ] through the ], the Minotaur appears at the center of many depictions of the Labyrinth.{{refn|Several examples are shown in Kern (2000).<ref name=Kern-2000/>}} ]'s Latin account of the Minotaur, which did not describe which half was bull and which half man, was the most widely available during the Middle Ages, and several later versions show a man's head and torso on a bull's body - the reverse of the Classical configuration, reminiscent of a ].{{refn|Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern.<ref name=Kern-2000/>}} This alternative tradition survived into the Renaissance, and is reflected in Dryden's elaborated translation of ]'s description of the Minotaur in Book VI of the '']'': "The lower part a beast, a man above/The monument of their polluted love."<ref>The Aeneid of Virgil, as translated by John Dryden, found at http://classics.mit.edu/Virgil/aeneid.6.vi.html . Virgil's text calls the Minotaur "biformis"; like Ovid, he does not describe which part is bull, which part man.</ref> It still figures in some modern depictions, such as ]'s illustrations for ]'s '']'' (1942). | |||

| == Theseus myth == | |||

| From Classical times through the Renaissance, the Minotaur appears at the center of many depictions of the Labyrinth.<ref>Several examples are shown in Kern, ''Through the Labyrinth'', Prestel, 2000.</ref> Ovid's Latin account of the Minotaur, which did not elaborate on which half was bull and which half man, was the most widely available during the Middle Ages, and several later versions show the reverse of the Classical configuration: a man's head and torso on a bull's body, reminiscent of a centaur.<ref>Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern. ''op. cit.''</ref> This alternative tradition survived into the Renaissance, and still figures in some modern depictions, such as Steele Savage's illustrations for ]'s ''Mythology'' (1942). | |||

| ] showing the victory of ] over the Minotaur in the presence of ] from {{Circa|435}} BC]] | |||

| All the stories agree that prince ], son of King Minos, died and that the fault lay with the Athenians. The sacrifice of ] was a penalty for his death. | |||

| In some versions he was killed by the ] because of their jealousy of the victories he had won at the ]; in others he was killed at ] by the Cretan Bull, his mother's former taurine lover, because ], king of Athens, had commanded Androgeus to slay it. The common tradition holds that Minos waged a war of revenge for the death of his son, and won. The consequence of Athens losing the war was the regular sacrifice of ]. ]' account of the myth said that Minos had led a fleet against Athens and simply harassed the Athenians until they had agreed to send children as sacrifices.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Pausanias, Description of Greece, Attica, chapter 27 |url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0160:book=1:chapter=27&highlight=minotaur |access-date=18 May 2023 |website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref> In his account of the Minotaur's birth, ] refers to yet another version<ref>{{cite book |author=] |url=http://rudy.negenborn.net/catullus/text2/e64.htm |title=Carmen 64}}</ref> in which Athens was "compelled by the cruel plague to pay penalties for the killing of ]". To avert a plague caused by divine retribution for the Cretan prince's death, Aegeus had to send into the Labyrinth "young men at the same time as the best of unwed girls as a feast" for the Minotaur. Some accounts declare that Minos required ], chosen by lots, to be sent every seventh year (or ninth); some versions say every year.<ref>{{cite book |author=] |title=On the ] |at=6.14 |quote={{lang|la|singulis quibusque annis}} 'every one year'.}} | |||

| ==Tribute price that brought Theseus to Crete== | |||

| ] in the shape of a bull's head at the Greek pavilion at ]]] | |||

| ], son of Minos, had been killed by the ], who were jealous of the victories he had won at the ]. Others say he was killed at ] by the ], his mother's former taurine lover, which ], king of Athens, had commanded him to slay. The common tradition is that Minos waged war to avenge the death of his son, and won. ], in his account of the Minotaur's birth,<ref> .</ref> refers to another version in which Athens was "compelled by the cruel plague to pay penalties for the killing of Androgeos." Aegeus must avert the plague caused by his crime by sending "young men at the same time as the best of unwed girls as a feast" to the Minotaur. Minos required that seven Athenian youths and seven maidens, drawn by lots, be sent every ninth year (some accounts say every year<ref>The annual period is given by J. E. Zimmerman, ''Dictionary of Classical Mythology'', Harper & Row, 1964, article "Androgeus"; and H. J. Rose, ''A Handbook of Greek Mythology'', Dutton, 1959, p. 265. Zimmerman cites Virgil, Apollodorus, and Pausanias. The nine-year period appears in Plutarch and Ovid.</ref>) to be devoured by the Minotaur. | |||

| : The annual period is given by {{cite dictionary |year=1964 |title=Androgeus |dictionary=Dictionary of Classical Mythology |publisher=] |last=Zimmerman |first=J.E. |postscript=;}} and {{cite book |last=Rose |first=H.J. |title=A Handbook of Greek Mythology |publisher=Dutton |year=1959 |page=265}} Zimmerman cites ], ], and ]. | |||

| When the third sacrifice approached, ] volunteered to slay the monster. He promised to his father, Aegeus, that he would put up a white sail on his journey back home if he was successful and would have the crew put up black sails if he was killed. In Crete, ], the daughter of Minos, fell in love with Theseus and helped him navigate the labyrinth, which had a single path to the center. In most accounts she gave him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path. Theseus killed the Minotaur with the sword of Aegeus and led the other Athenians back out of the labyrinth. But he forgot to put up the white sail, so when his father saw the ship he presumed Theseus was dead and threw himself into the sea, thus committing suicide. <ref>Plutarch, ''Theseus,'' 15—19; ] i. I6, iv. 61; '']'' iii. 1,15</ref> | |||

| : The nine-year period appears in ] and ].</ref> | |||

| ==Etruscan view== | |||

| This essentially Athenian view of the Minotaur as the antagonist of Theseus reflects the literary sources, which are biased in favour of Athenian perspectives. The Etruscans, who paired Ariadne with Dionysus, never with Theseus, offered an alternative Etruscan view of the Minotaur, never seen in Greek arts: on an Etruscan red-figure wine-cup of the early-to-mid fourth century Pasiphaë tenderly dandles an infant Minotaur on her knee.<ref>The wine cup is illustrated in Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, ''Etruscan Mythology'' (Series The Legendary Past, British Museum/University of Texas) 2006, fig.29 p. 44 ("early fourth century") ().</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| When the time for the third sacrifice approached, the Athenian prince ] volunteered to slay the Minotaur. Isocrates orates that Theseus thought that he would rather die than rule a city that paid a tribute of children's lives to their enemy.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Isocrates, Helen, section 27 |url=http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.01.0144:speech=10:section=27&highlight=minotaur |access-date=18 May 2023 |website=www.perseus.tufts.edu}}</ref> He promised his father Aegeus that he would change the somber black sail of the boat carrying the victims from Athens to Crete, and put up a white sail for his return journey if he was successful; the crew would leave up the black sail if he was killed. | |||

| In Crete, Minos's daughter ] fell madly in love with Theseus and helped him navigate the Labyrinth. In most accounts she gave him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path. According to various classical sources and representations, Theseus killed the Minotaur with his bare hands, sometimes with a club or a sword.{{citation needed|date=January 2020}} He then led the Athenians out of the Labyrinth, and they sailed with Ariadne away from Crete. On the way home, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of ] and continued to Athens. The returning group neglected to replace the black sail with the promised white sail, and from his lookout on Cape ], King Aegeus saw the black-sailed ship approach. Presuming his son dead, he killed himself by leaping into the ].<ref>{{cite book |author=] |title=Theseus |at=15–19}}{{cite book |author=] |title=] |at=i.16, iv.61}}{{cite book |author=] |title=] |at=iii.1, 15}}</ref> His death secured the throne for Theseus. | |||

| ==Interpretations== | ==Interpretations== | ||

| ]), ]]] | |||

| ], ''Gemmae Antiche'', 1709, Pt. IV, pl. 31; Hermann Kern, ''Through the Labyrinth'', Prestel, 2000, fig. 371, p. 202): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from ]".</ref>]] | |||

| ] |

], {{Circa|550-540}} BC]] | ||

| The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in ]. A Knossian ] exhibits on one side the labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; one of the monster's names was ] ("star"). | |||

| The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in ]. A Knossian ] exhibits on one side the Labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; one of the monster's names was Asterion or Asterius ("star"). <blockquote>] gave birth to Asterius, who was called the Minotaur. He had the face of a bull, but the rest of him was human; and Minos, in compliance with certain oracles, shut him up and guarded him in the Labyrinth.<ref>{{cite book |author=] |title=] |at=3.1.4}}</ref></blockquote>While the ruins of Minos's palace at Knossos were discovered, the Labyrinth never was. The multiplicity of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led some archaeologists to suggest that the palace itself was the source of the Labyrinth myth, with over 1300 maze-like compartments,<ref>{{cite web |first=C. Michael |last=Hogan |year=2007 |title=Knossos fieldnotes |website=The Modern Antiquarian |editor=Cope, Julian |url=http://www.themodernantiquarian.com/site/10854/knossos.html#fieldnotes}}</ref> an idea that is now generally discredited.{{efn| | |||

| The ruins of Minos' palace at Knossos have been found, but the labyrinth has not. The enormous number of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led some archaeologists to suggest that the palace itself was the source of the labyrinth myth, an idea generally discredited today.<ref>Sir Arthur Evans, the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not himself believe it; see David McCullough, ''The Unending Mystery'', Pantheon, 2004, p. 34-36. Modern scholarship generally discounts the idea; see Kern, ''Through the Labyrinth'', Prestel, 2000, p. 42-43, and Doob, ''The Idea of the Labyrinth'', Cornell University Press, p. 1990, p. 25.</ref> Homer, describing the ], remarked that the labyrinth was ]'s ceremonial dancing ground. | |||

| Sir ], the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not believe it;<ref>{{cite book |first=David |last=McCullough |title=The Unending Mystery |publisher=Pantheon |date=2004 |pages=34–36}}</ref> modern scholarship generally discounts the idea.<ref name=Kern-2000/>{{rp|style=ama|pp= 42–43}}<ref name=Doob-1990/>{{rp|style=ama|p= 25}} | |||

| }} | |||

| Homer, describing the ], remarked that Daedalus had constructed a ceremonial dancing ground for ], but does not associate this with the term ''labyrinth''. | |||

| Some |

Some 19th century mythologists proposed that the Minotaur was a personification of the sun and a Minoan adaptation of the ]-] of the ]ns. The slaying of the Minotaur by Theseus in that case could be interpreted as a memory of Athens breaking tributary relations with ].<ref name="EB1911">{{Cite EB1911|wstitle=Minotaur|volume=18|page=555}}</ref> | ||

| According to ], ''Minos'' and ''Minotaur'' |

According to ], ''Minos'' and ''Minotaur'' were different forms of the same personage, representing the ] of the Cretans, who depicted the sun as a bull. He and ] both explain Pasiphaë's union with the bull as a sacred ceremony, at which the queen of Knossos was wedded to a bull-formed god, just as the wife of the ] in Athens was wedded to ]. E. Pottier, who does not dispute the historical personality of Minos, in view of the story of ], considers it probable that in Crete (where a ] may have existed by the side of that of the ]) victims were tortured by being shut up in the belly of a red-hot ]. The story of ], the Cretan man of ], who heated himself red-hot and clasped strangers in his embrace as soon as they landed on the island, is probably of similar origin. | ||

| ], Cyprus]] | |||

| A historical explanation of the myth refers to the time when Crete was the main political and cultural potency in the Aegean Sea. As the fledgling Athens (and probably other continental Greek cities) was under tribute to Crete, it can be assumed that such tribute included young men and women for sacrifice. This ceremony was performed by a priest disguised with a bull head or mask, thus explaining the imagery of the Minotaur. It may also be that this priest was son to Minos. | |||

| ] Perfume Jar in the shape of a minotaur|200x200px]]], engraving of a 16th-century AD gem in the Medici Collection in the ], Florence{{refn| | |||

| Once continental Greece was free from Crete's dominance, the myth of the Minotaur worked to distance the forming religious consciousness of the Hellene '']'' from Minoan beliefs. | |||

| ] (1709), ''Gemmae Antiche'', Pt. IV, pl. 31; Kern (2000): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from ]".<ref name=Kern-2000/>{{rp|style=ama|p= 202, fig. 371}} | |||

| }}|150x150px]] | |||

| ] viewed the Minotaur, or Asterios, as a god associated with stars, comparable to ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kerenyi |first=Karl |year=1951 |title=The Gods of the Greeks |pages=269}}</ref> Coins minted at ] from the fifth century showed labyrinth patterns encircling a goddess's head crowned with a wreath of grain,<ref>See illustrations of ], for an example of a goddess crowned with a labyrinthine wreath of grain.</ref> a bull's head, or a star. Kerényi argued that the star in the Labyrinth was in fact Asterios, making the Minotaur a "luminous" deity in Crete, associated with a goddess known as the Mistress of the Labyrinth.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Kerényi|first=Karl|title=Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life|year=1976|pages=104–105, 159}}</ref> | |||

| ]'s image of the Minotaur to illustrate ''Inferno'' XII]] | |||

| A geological interpretation also exists. Citing early descriptions of the minotaur by ] as being entirely focused on the "cruel bellowing"<ref name=Callimachus-Mair-Mair-1921>{{cite book |author=] |year=1921 |title=Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams |translator1=Mair, A.W. |translator2=Mair, G.R. |place=Cambridge, MA |publisher=Harvard University Press}}</ref>{{efn| | |||

| ==The Minotaur in Dante's ''Inferno''== | |||

| ] first refers to the minotaur with the phrase | |||

| The Minotaur, the ''infamia di Creti'', appears briefly in ]'s '']'', Canto 12,11-15, where, picking their way among boulders dislodged on the slope and preparing to enter into the Seventh Circle,<ref> The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17. </ref> Dante and ] his guide encounter the beast first among those damned for their violent natures, the "men of blood", though the creature is not actually named until line 25.<ref>Jeremy Tambling, "Monstrous Tyranny, Men of Blood: Dante and "Inferno" XII" ''The Modern Language Review'' '''98'''.4 (October 2003:881-897).</ref> At Virgil's taunting reminder of the "]", the Minotaur rises enraged and distracted, and Virgil and Dante pass quickly by to the ]s, who guard the ], "river of blood". This unusual association of the Minotaur with centaurs, not made in any Classical source, is shown visually in William Blake's rendering of the Minotaur (''illustration'') as a kind of taurine centaur himself. | |||

| : "Having escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild son of ] and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth" ...<ref name=Callimachus-Mair-Mair-1921/> | |||

| }} | |||

| it made from its underground labyrinth, and the extensive tectonic activity in the region, science journalist Matt Kaplan has theorised that the myth may well stem from geology. | |||

| {{efn| | |||

| Kaplan argues that the minotaur is the result of ancient people trying to explain earthquakes;<ref>{{cite book |author=Kaplan, Matt |title=Science of Monsters |place=New York, NY |publisher=Simon & Schuster |year=2012}}</ref> he points out that carbon dating of marine fossils attached to boulders that were ejected from the ocean by ancient ] indicates the region was ] very active during the years when the minotaur myth first appeared.<ref>{{cite journal |author1=Scheffers, Anja |display-authors=etal |year=2008 |title=Late Holocene tsunami traces on the western and southern coastlines of the Peloponnesus (Greece) |journal=] |volume=269 |issue=1–2 |pages=271–279|doi=10.1016/j.epsl.2008.02.021 |bibcode=2008E&PSL.269..271S }}</ref> Given this, he argues that the Minoans used the monster to help explain the terrifying earthquakes that were "bellowing" beneath their feet. | |||

| }} | |||

| == |

===Image gallery=== | ||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="110"> | |||

| {{commonscat|Minotaur}} | |||

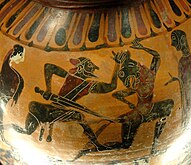

| File:Theseus Castellani Louvre E850.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur. Detail from an Attic ] ], {{circa|575 BC–550 BC}}. | |||

| * in ] ] had a bull body and a human head. | |||

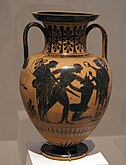

| File:Theseus Minotaur Louvre F33.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from a black-figure Attic amphora, {{circa|540 BC}}. | |||

| * ] or ] worshipped in the ], and depicted as a man with the head of a bull. | |||

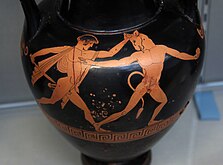

| File:Theseus Minotauros Louvre G67.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic red-figured plate, 520–510 BC. | |||

| * The Egyptian god ] is often depicted as a bull, or bull-headed man. | |||

| File:Theseus Minotauros Louvre CA2254.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic black-figure ], 500–475 BC. From Crimea. | |||

| * ] Another bull-headed monster; from Japanese folklore. | |||

| File:183-Thesee-tuant-le-Minotaure MNA.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur, black-figure amphora {{Circa|480}} BC | |||

| * ] | |||

| File:British Museum Room 20a Neck Amphora Oionokles Painter Theseus and the Minotaur 19022019 6619.jpg|Theseus fighting the Minotaur, red-figure amphora, {{Circa|460}} BC | |||

| * ] 20th century British artist whose work included many interpretations of the Minotaur, Daedalus, mazes and the ]. | |||

| File:Theseus Minotauros Staatliche Antikensammlungen SL471.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from an Attic red-figure ], {{circa|460 BC}}. | |||

| File:Kylix Theseus Minotauros Louvre F83.jpg|Theseus and the Minotaur, Attic black-figure kylix tondo, {{circa|450–440 BC}}. | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==References== | == References in media == | ||

| * source Greek texts and art. | |||

| {{In popular culture|section|date=May 2020}} | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | |||

| ===Dante's ''Inferno''=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] and ] meet the Minotaur, illustration by ]]] | |||

| ] | |||

| The Minotaur ({{lang|it|infamia di Creti}}, Italian for 'infamy of Crete'), appears briefly in ]'s '']'', in Canto 12 (l. 12–13, 16–21), where Dante and his guide ] find themselves picking their way among boulders dislodged on the slope and preparing to enter into the ].<ref>The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17.</ref> Dante and Virgil encounter the beast first among the "men of blood": those damned for their violent natures. Some commentators believe that Dante, in a reversal of classical tradition, bestowed the beast with a man's head upon a bull's body,<ref>Inferno XII, verse translation by R. Hollander, p. 228 commentary</ref> though this representation had already appeared in the Middle Ages.<ref name=Kern-2000/>{{rp|style=ama|pp= 116–117}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Verse translation |lang=it | |||

| ] | |||

| |attr1='']'', Canto XII, lines 16–20 | |||

| ] | |||

| |1= | |||

| Lo savio mio inver' lui gridò: "Forse | |||

| tu credi che qui sia 'l duca d'Atene, | |||

| che sú nel mondo la morte ti porse? | |||

| Pártiti, bestia, ché questi non vene | |||

| ammaestrato da la tua sorella, | |||

| ma vassi per veder la vostre pene." | |||

| |2= | |||

| My sage cried out to him: "You think, | |||

| perhaps, this is the Duke of Athens, | |||

| who in the world put you to death. | |||

| Get away, you beast, for this man | |||

| does not come tutored by your sister; | |||

| he comes to view your punishments." | |||

| }} | |||

| ]'s image of the Minotaur to illustrate ''Inferno'' XII]] | |||

| ] | |||

| In these lines, Virgil taunts the Minotaur to distract him, and reminds the Minotaur that he was killed by ] with the help of the monster's half-sister ]. The Minotaur is the first infernal guardian whom Virgil and Dante encounter within the walls of ].{{efn| | |||

| ] | |||

| The ]s, the ] , and the unseen ] were located on the ]'s defensive ramparts.<ref>{{cite book |first=Dante |last=Alighieri |author-link=Dante Alighieri |title=] |section=Canto IX}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||

| The Minotaur seems to represent the entire zone of ], much as ] represents Fraud in Canto XVI, and serves a similar role as gatekeeper for the entire seventh Circle.<ref>Boccaccio, ''Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine'' commentary</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] writes of the Minotaur in his literary commentary of the Commedia: "When he had grown up and become a most ferocious animal, and of incredible strength, they tell that Minos had him shut up in a prison called the labyrinth, and that he had sent to him there all those whom he wanted to die a cruel death".<ref>{{cite book |author=Boccaccio |first=G. |author-link=Giovanni Boccaccio |date=30 November 2009 |title=Boccaccio's Expositions on Dante's Comedy |publisher=University of Toronto Press}}</ref> ], in his own commentary,<ref>Bennett, Pre-Raphaelite Circle, 177–180.</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/pr5246.a43.vol2.rad.html |title=Dante Gabriel Rossetti. His Family-Letters with a Memoir (Volume Two) |website=www.rossettiarchive.org}}</ref> compares the Minotaur with all three sins of violence within the seventh circle: "The Minotaur, who is situated at the rim of the tripartite circle, fed, according to the poem was biting himself (violence against one's body) and was conceived in the 'false cow' (violence against nature, daughter of God)." | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Virgil and Dante then pass quickly by to the ]s (Nessus, Chiron and Pholus) who guard the ] ("river of blood"), to continue through the seventh Circle.<ref>Beck, Christopher, "Justice among the Centaurs", Forum Italcium 18 (1984): 217–229</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Surrealist art === | |||

| ] | |||

| ]'s illustration of ''Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth'', 1861]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| * ] made a series of etchings in the '']'' showing the Minotaur being tormented, possibly inspired also by Spanish bullfighting.<ref>Tidworth, Simon, "Theseus in the Modern World", essay in ''The Quest for Theseus'' London 1970 pp. 244–249 {{ISBN|0269026576}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Television, literature and plays=== | |||

| ] | |||

| * Argentine author ] published the play {{lang|es|Los reyes}} (''The Kings'') in 1949, which reinterprets the Minotaur's story. In the book, Ariadne is not in love with Theseus, but with her brother the Minotaur.<ref>{{cite journal |trans-title=Los reyes: The Labyrinth Between Myth and History |language=es |title=Los reyes: El laberinto entre mito e historia |first=Antonella |last=De Laurentiis |issn=1989-1709 |pages=145–155 |volume=1 |year=2009 |journal=Amaltea. Revista de mitocrítica |publisher=] }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| * The short story '']'' by the Argentine writer ] gives the Minotaur's story from the monster's perspective.<ref>{{cite journal |url=https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00144940.1992.9937945 |last=Bennett |first=Maurice J |title=Borges's The House of Asterion |journal=The Explicator |volume=50 |issue=3 |pages=166–170 |year=1992 |doi=10.1080/00144940.1992.9937945}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| * Asterion is the chief antagonist of '']'', ]'s 1958 reinterpretation of the Theseus myth in the light of the excavation of Knossos.<ref>{{Cite journal |date=1958 |title=Fiction and Drama |url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/809856 |journal=The English Journal |volume=47 |issue=9 |pages=587–89|jstor=809856 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ===Film=== | |||

| ] | |||

| *'']'', a 1960 Italian film directed by ] and starring ]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://letterboxd.com/film/the-minotaur-the-wild-beast-of-crete/|title=The Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete |work=Letter Box|access-date=2 May 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| *'']'', a horror adaptation of the legend starring ] as Theo (Theseus), was released on DVD by ] in 2006.<ref name="allmoviedvd">{{cite AV media |title=Minotaur (2005) |people=Jonathan English (director)|url=https://www.allmovie.com/movie/minotaur-v342810/releases|via=AllMovie|access-date=2 March 2018}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| === Video and role-playing games === | |||

| ] | |||

| *The '']'' role-playing game features minotaurs as opponents and playable characters, but translates them from a singular creature into a species.<ref>{{cite book|author-first=Richard W.|author-last=Forest|editor-first=Jeffrey|editor-last=Weinstock|date=2014|title=The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters|publisher=]|chapter=Dungeons & Dragons, Monsters in}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|first=Liz|last=Gloyn|author-link=Liz Gloyn |date=2019|title=Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture|publisher=]|pages=36–37|isbn=978-1-7845-3934-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Hickman |first1=Tracy |authorlink=Tracy Hickman |first2=Margaret |last2=Weis |authorlink2=Margaret Weis |year=1987 |title=] |publisher=] |isbn=0-88038-452-2}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| *In the 2018 action-adventure game '']'', the minotaur is a legendary creature to be defeated in a boss fight.<ref>{{cite magazine |url=https://www.gamesradar.com/assassins-creed-odyssey-minotaur/ |title=How to find and beat the Assassin's Creed Odyssey Minotaur |first=Sam |last=Loveridge |date=1 May 2020 |access-date=12 December 2024 |magazine=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.thegamer.com/assassins-creed-odyssey-how-to-find-and-defeat-the-minotaur/ |title=Assassin's Creed Odyssey: How To Find And Defeat The Minotaur |first=Jesse |last=Lennox |date=2 October 2020 |access-date=12 December 2024 |work=]}}</ref> In a series of missions various references are made to the mythical history of the minotaur,<ref>{{cite news |url=https://screenrant.com/find-beat-minotaur-assassins-creed-odyssey/ |title=How to Find (& Beat) The Minotaur in Assassin's Creed Odyssey |first=Cody |last=Peterson |date=11 September 2020 |access-date=12 December 2024 |work=]}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.newsweek.com/assassins-creed-odyssey-gates-atlantis-guide-minotaur-medusa-sphinx-cyclops-1158456 |title='Assassin's Creed Odyssey' Gates of Atlantis Guide: Where is the Minotaur, Medusa, Sphinx and Cyclops? |first=Bob |last=Fekete |date=8 October 2018 |access-date=12 December 2024 |magazine=]}}</ref> like Thesseus and the thread of Ariadne. | |||

| ] | |||

| *In the 2019 virtual novel game ''Minotaur Hotel'', Asterion the minotaur is a romanceable non-playable character; "Minotaur Hotel is an award-winning gay romance story where you'll meet and grow close with Asterion, the Minotaur of Greek legend, and manage a magical hotel staffed by a cast of mythological beings."<ref>{{cite web |last1=MinoAnon |last2=Nanoff |title=Minotaur Hotel |url=https://minoh.itch.io/minotaur-hotel |website=] |access-date=9 August 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |last1=Wright |first1=Steve |title=Melbourne Queer Game Festival 2021 winners announced |url=https://stevivor.com/news/melbourne-queer-game-festival-2021-winners-announced/ |website=Stevivor |date=6 October 2021 |access-date=9 August 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| * In the 2024 video game '']'', one of the playable main characters is a minotaur.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Macgregor |first1=Jody |title=Sovereign Syndicate review |url=https://www.pcgamer.com/sovereign-syndicate-review/ |website=] |publisher=] |access-date=23 January 2024 |date=11 January 2024}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| ] | |||

| *] – a logic game that is inspired by the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth. | |||

| ] | |||

| *] – a legendary chaotic bull in Meitei mythology, similar to Minotaur in character | |||

| ] | |||

| *] – two guardians or types of guardians of the underworld in Chinese mythology | |||

| ] | |||

| *] – a legendary human-horse (later human-goat) hybrid(s) | |||

| ] | |||

| *] – a figure in Mesopotamian mythology with the body of a bull and a human head | |||

| ] | |||

| *'']'' – a ] of ] endemic to the ]<ref name=Kulc1903>{{cite journal |last=Kulczyński |first=W. |year=1903 |title=Aranearum et Opilionum species in insula Creta a comite Dre Carolo Attems collectae. |journal=Bulletin International de l'Académie des Sciences de Cracovie |pages=32–58 |volume=1903 }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == Footnotes == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{reflist|25em}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == External links == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Sister project links|collapsible=collapsed|wikt=minotaur|commonscat=yes|n=no|q=no|s=minotaur|b=no|v=no}} | |||

| ] | |||

| * source Greek texts and art. | |||

| * | |||

| {{Greek religion}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 18:44, 17 January 2025

Creature of Greek mythology This article is about the mythological monster. For other uses, see Minotaur (disambiguation).

| Minotaur | |

|---|---|

The Minotaur on an Attic kylix tondo from c. 515 BC with a kalos inscription. The Minotaur on an Attic kylix tondo from c. 515 BC with a kalos inscription. | |

| Other names | Asterion |

| Abode | Labyrinth, Crete |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Cretan Bull and Pasiphaë |

| Siblings | Acacallis, Ariadne, Androgeus, Glaucus (son of Minos), Deucalion, Phaedra, Xenodice and Catreus |

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur (Ancient Greek: Μινώταυρος, Mīnṓtauros), also known as Asterion, is a mythical creature portrayed during classical antiquity with the head and tail of a bull and the body of a man or, as described by Roman poet Ovid, a being "part man and part bull". He dwelt at the center of the Labyrinth, which was an elaborate maze-like construction designed by the architect Daedalus and his son Icarus, upon command of King Minos of Crete. According to tradition, every nine years the people of Athens were compelled by King Minos to choose fourteen young noble citizens (seven men and seven women) to be offered as sacrificial victims to the Minotaur in retribution for the death of Minos's son Androgeos. The Minotaur was eventually slain by the Athenian hero Theseus, who managed to navigate the labyrinth with the help of a thread offered to him by the King's daughter, Ariadne.

Etymology

The word "Minotaur" derives from the Ancient Greek Μινώταυρος [miːnɔ̌ːtau̯ros] a compound of the name Μίνως (Minos) and the noun ταῦρος tauros meaning 'bull', thus it is translated as the 'Bull of Minos'. In Crete, the Minotaur was known by the name Asterion (Ἀστερίων) or Asterius (Ἀστέριος), a name shared with Minos's foster-father.

"Minotaur" was originally a proper noun in reference to this mythic figure. That is, there was only the one Minotaur. In contrast, the use of "minotaur" as a common noun to refer to members of a generic "species" of bull-headed creatures developed much later, in 20th century fantasy genre fiction.

The Minotaur was called Minotaurus [miːnoːˈtau̯rʊs] in Latin and Θevrumineš in Etruscan. English pronunciation of the word "Minotaur" is varied; the following can be found in dictionaries: /ˈmaɪnətɔːr, -noʊ-/ MY-nə-tor, -noh-, /ˈmɪnətɑːr, ˈmɪnoʊ-/ MIN-ə-tar, MIN-oh-, /ˈmɪnətɔːr, ˈmɪnoʊ-/ MIN-ə-tor, MIN-oh-.

Creation myth

After ascending the throne of the island of Crete, Minos competed with his brothers as ruler. Minos prayed to the sea god Poseidon to send him a snow-white bull as a sign of the god's favor. Minos was to sacrifice the bull to honor Poseidon, but owing to the bull's beauty he decided instead to keep him. Minos believed that the god would accept a substitute sacrifice. To punish Minos, Poseidon arranged with Aphrodite for Minos's wife, Pasiphaë, to fall in love with the bull. Pasiphaë had the master craftsman, Daedalus, fashion for her a hollow wooden cow, which she climbed into to let the bull mate with her. She then fell pregnant and bore Asterius, the Minotaur, making him a grandchild of Helios. Pasiphaë nursed the Minotaur but he grew in size and became ferocious. As the unnatural offspring of a woman and a beast, the Minotaur had no natural source of nourishment and thus devoured humans for sustenance. Minos, following advice from the oracle at Delphi, had Daedalus construct a gigantic Labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos's palace in Knossos.

Appearance

The Minotaur is commonly represented in Classical art with the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull. According to Sophocles's Trachiniai, when the river spirit Achelous seduced Deianira, one of the guises he assumed was a man with the head of a bull. From classical antiquity through the Renaissance, the Minotaur appears at the center of many depictions of the Labyrinth. Ovid's Latin account of the Minotaur, which did not describe which half was bull and which half man, was the most widely available during the Middle Ages, and several later versions show a man's head and torso on a bull's body - the reverse of the Classical configuration, reminiscent of a centaur. This alternative tradition survived into the Renaissance, and is reflected in Dryden's elaborated translation of Virgil's description of the Minotaur in Book VI of the Aeneid: "The lower part a beast, a man above/The monument of their polluted love." It still figures in some modern depictions, such as Steele Savage's illustrations for Edith Hamilton's Mythology (1942).

Theseus myth

All the stories agree that prince Androgeus, son of King Minos, died and that the fault lay with the Athenians. The sacrifice of young Athenian men and women was a penalty for his death.

In some versions he was killed by the Athenians because of their jealousy of the victories he had won at the Panathenaic Games; in others he was killed at Marathon by the Cretan Bull, his mother's former taurine lover, because Aegeus, king of Athens, had commanded Androgeus to slay it. The common tradition holds that Minos waged a war of revenge for the death of his son, and won. The consequence of Athens losing the war was the regular sacrifice of several of their youths and maidens. Pausanias' account of the myth said that Minos had led a fleet against Athens and simply harassed the Athenians until they had agreed to send children as sacrifices. In his account of the Minotaur's birth, Catullus refers to yet another version in which Athens was "compelled by the cruel plague to pay penalties for the killing of Androgeon". To avert a plague caused by divine retribution for the Cretan prince's death, Aegeus had to send into the Labyrinth "young men at the same time as the best of unwed girls as a feast" for the Minotaur. Some accounts declare that Minos required seven Athenian youths and seven maidens, chosen by lots, to be sent every seventh year (or ninth); some versions say every year.

When the time for the third sacrifice approached, the Athenian prince Theseus volunteered to slay the Minotaur. Isocrates orates that Theseus thought that he would rather die than rule a city that paid a tribute of children's lives to their enemy. He promised his father Aegeus that he would change the somber black sail of the boat carrying the victims from Athens to Crete, and put up a white sail for his return journey if he was successful; the crew would leave up the black sail if he was killed.

In Crete, Minos's daughter Ariadne fell madly in love with Theseus and helped him navigate the Labyrinth. In most accounts she gave him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path. According to various classical sources and representations, Theseus killed the Minotaur with his bare hands, sometimes with a club or a sword. He then led the Athenians out of the Labyrinth, and they sailed with Ariadne away from Crete. On the way home, Theseus abandoned Ariadne on the island of Naxos and continued to Athens. The returning group neglected to replace the black sail with the promised white sail, and from his lookout on Cape Sounion, King Aegeus saw the black-sailed ship approach. Presuming his son dead, he killed himself by leaping into the sea that is since named after him. His death secured the throne for Theseus.

Interpretations

The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in Greek art. A Knossian didrachm exhibits on one side the Labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; one of the monster's names was Asterion or Asterius ("star").

Pasiphaë gave birth to Asterius, who was called the Minotaur. He had the face of a bull, but the rest of him was human; and Minos, in compliance with certain oracles, shut him up and guarded him in the Labyrinth.

While the ruins of Minos's palace at Knossos were discovered, the Labyrinth never was. The multiplicity of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led some archaeologists to suggest that the palace itself was the source of the Labyrinth myth, with over 1300 maze-like compartments, an idea that is now generally discredited.

Homer, describing the shield of Achilles, remarked that Daedalus had constructed a ceremonial dancing ground for Ariadne, but does not associate this with the term labyrinth.

Some 19th century mythologists proposed that the Minotaur was a personification of the sun and a Minoan adaptation of the Baal-Moloch of the Phoenicians. The slaying of the Minotaur by Theseus in that case could be interpreted as a memory of Athens breaking tributary relations with Minoan Crete.

According to A.B. Cook, Minos and Minotaur were different forms of the same personage, representing the sun-god of the Cretans, who depicted the sun as a bull. He and J. G. Frazer both explain Pasiphaë's union with the bull as a sacred ceremony, at which the queen of Knossos was wedded to a bull-formed god, just as the wife of the Tyrant in Athens was wedded to Dionysus. E. Pottier, who does not dispute the historical personality of Minos, in view of the story of Phalaris, considers it probable that in Crete (where a bull cult may have existed by the side of that of the labrys) victims were tortured by being shut up in the belly of a red-hot brazen bull. The story of Talos, the Cretan man of brass, who heated himself red-hot and clasped strangers in his embrace as soon as they landed on the island, is probably of similar origin.

Kerényi Károly viewed the Minotaur, or Asterios, as a god associated with stars, comparable to Dionysus. Coins minted at Knossos from the fifth century showed labyrinth patterns encircling a goddess's head crowned with a wreath of grain, a bull's head, or a star. Kerényi argued that the star in the Labyrinth was in fact Asterios, making the Minotaur a "luminous" deity in Crete, associated with a goddess known as the Mistress of the Labyrinth.

A geological interpretation also exists. Citing early descriptions of the minotaur by Callimachus as being entirely focused on the "cruel bellowing" it made from its underground labyrinth, and the extensive tectonic activity in the region, science journalist Matt Kaplan has theorised that the myth may well stem from geology.

Image gallery

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Detail from an Attic black-figure amphora, c. 575 BC–550 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Detail from an Attic black-figure amphora, c. 575 BC–550 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from a black-figure Attic amphora, c. 540 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from a black-figure Attic amphora, c. 540 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic red-figured plate, 520–510 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic red-figured plate, 520–510 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic black-figure lekythos, 500–475 BC. From Crimea.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Attic black-figure lekythos, 500–475 BC. From Crimea.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur, black-figure amphora c. 480 BC

Theseus and the Minotaur, black-figure amphora c. 480 BC

-

Theseus fighting the Minotaur, red-figure amphora, c. 460 BC

Theseus fighting the Minotaur, red-figure amphora, c. 460 BC

-

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from an Attic red-figure stamnos, c. 460 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur. Side A from an Attic red-figure stamnos, c. 460 BC.

-

Theseus and the Minotaur, Attic black-figure kylix tondo, c. 450–440 BC.

Theseus and the Minotaur, Attic black-figure kylix tondo, c. 450–440 BC.

References in media

| This section may contain irrelevant references to popular culture. Please help Misplaced Pages to improve this section by removing the content or adding citations to reliable and independent sources. (May 2020) |

Dante's Inferno

The Minotaur (infamia di Creti, Italian for 'infamy of Crete'), appears briefly in Dante's Inferno, in Canto 12 (l. 12–13, 16–21), where Dante and his guide Virgil find themselves picking their way among boulders dislodged on the slope and preparing to enter into the seventh circle of hell. Dante and Virgil encounter the beast first among the "men of blood": those damned for their violent natures. Some commentators believe that Dante, in a reversal of classical tradition, bestowed the beast with a man's head upon a bull's body, though this representation had already appeared in the Middle Ages.

|

Lo savio mio inver' lui gridò: "Forse |

My sage cried out to him: "You think, |

| —Inferno, Canto XII, lines 16–20 |

In these lines, Virgil taunts the Minotaur to distract him, and reminds the Minotaur that he was killed by Theseus the Duke of Athens with the help of the monster's half-sister Ariadne. The Minotaur is the first infernal guardian whom Virgil and Dante encounter within the walls of Dis. The Minotaur seems to represent the entire zone of Violence, much as Geryon represents Fraud in Canto XVI, and serves a similar role as gatekeeper for the entire seventh Circle.

Giovanni Boccaccio writes of the Minotaur in his literary commentary of the Commedia: "When he had grown up and become a most ferocious animal, and of incredible strength, they tell that Minos had him shut up in a prison called the labyrinth, and that he had sent to him there all those whom he wanted to die a cruel death". Dante Gabriel Rossetti, in his own commentary, compares the Minotaur with all three sins of violence within the seventh circle: "The Minotaur, who is situated at the rim of the tripartite circle, fed, according to the poem was biting himself (violence against one's body) and was conceived in the 'false cow' (violence against nature, daughter of God)."

Virgil and Dante then pass quickly by to the centaurs (Nessus, Chiron and Pholus) who guard the Flegetonte ("river of blood"), to continue through the seventh Circle.

Surrealist art

- Pablo Picasso made a series of etchings in the Vollard Suite showing the Minotaur being tormented, possibly inspired also by Spanish bullfighting.

Television, literature and plays

- Argentine author Julio Cortázar published the play Los reyes (The Kings) in 1949, which reinterprets the Minotaur's story. In the book, Ariadne is not in love with Theseus, but with her brother the Minotaur.

- The short story The House of Asterion by the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges gives the Minotaur's story from the monster's perspective.

- Asterion is the chief antagonist of The King Must Die, Mary Renault's 1958 reinterpretation of the Theseus myth in the light of the excavation of Knossos.

Film

- Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete, a 1960 Italian film directed by Silvio Amadio and starring Bob Mathias

- Minotaur, a horror adaptation of the legend starring Tom Hardy as Theo (Theseus), was released on DVD by Lions Gate in 2006.

Video and role-playing games

- The Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game features minotaurs as opponents and playable characters, but translates them from a singular creature into a species.

- In the 2018 action-adventure game Assassin's Creed Odyssey, the minotaur is a legendary creature to be defeated in a boss fight. In a series of missions various references are made to the mythical history of the minotaur, like Thesseus and the thread of Ariadne.

- In the 2019 virtual novel game Minotaur Hotel, Asterion the minotaur is a romanceable non-playable character; "Minotaur Hotel is an award-winning gay romance story where you'll meet and grow close with Asterion, the Minotaur of Greek legend, and manage a magical hotel staffed by a cast of mythological beings."

- In the 2024 video game Sovereign Syndicate, one of the playable main characters is a minotaur.

See also

- Theseus and the Minotaur – a logic game that is inspired by the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur in the Labyrinth.

- Kao (bull) – a legendary chaotic bull in Meitei mythology, similar to Minotaur in character

- Ox-Head and Horse-Face – two guardians or types of guardians of the underworld in Chinese mythology

- Satyr – a legendary human-horse (later human-goat) hybrid(s)

- Shedu – a figure in Mesopotamian mythology with the body of a bull and a human head

- Minotauria – a genus of woodlouse hunting spiders endemic to the Balkans

Footnotes

- In Ancient Greek: ὁ παῖς καλός, ho pais kalos meaning "the boy is beautiful", a common epigraphic formula found on Attic pottery

- /ˈmaɪnətɔːr, ˈmɪnətɔːr/ MY-nə-tor, MIN-ə-tor, US: /ˈmɪnətɑːr, -oʊ-/ MIN-ə-tar, -oh-;

-

According to Ovid:

- semibovemque virum semivirumque bovem, one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo.

- In a counter-intuitive cultural development going back at least to Cretan coins of the 4th century BCE, many visual patterns representing the Labyrinth do not have dead ends like a maze; instead, a single path winds to the center.

- Hesiod says of Zeus's establishment of Europa in Crete:

- "... he made her live with Asterion the king of the Cretans. There she conceived and bore three sons, Minos, Sarpedon, and Rhadamanthys."

- Sir Arthur Evans, the first of many archaeologists who have worked at Knossos, is often given credit for this idea, but he did not believe it; modern scholarship generally discounts the idea.

-

Callimachus first refers to the minotaur with the phrase

- "Having escaped the cruel bellowing and the wild son of Pasiphaë and the coiled habitation of the crooked labyrinth" ...

- Kaplan argues that the minotaur is the result of ancient people trying to explain earthquakes; he points out that carbon dating of marine fossils attached to boulders that were ejected from the ocean by ancient tsunamis indicates the region was tectonically very active during the years when the minotaur myth first appeared. Given this, he argues that the Minoans used the monster to help explain the terrifying earthquakes that were "bellowing" beneath their feet.

- The fallen angels, the Erinyes , and the unseen Medusa were located on the City of Dis's defensive ramparts.

References

- ^ "English Dictionary: Definition of Minotaur". Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- ^ Bechtel, John Hendricks (1908), Pronunciation: Designed for Use in Schools and Colleges and Adapted to the Wants of All Persons who Wish to Pronounce According to the Highest Standards, Penn Publishing Co.

- Garnett, Richard; Vallée, Léon; Brandl, Alois (1923), The Book of Literature: A Comprehensive Anthology of the Best Literature, Ancient, Mediæval and Modern, with Biographical and Explanatory Notes, vol. 33, Grolier society.

- ^ Kern, Hermann (2000). Through the Labyrinth. Munich, London, New York: Prestel. ISBN 379132144-7.

- Ovid. Ars Amatoria. 2.24.

- A. Pedo cited by Rusten, J.S. (Autumn 1982). "Ovid, Empedocles, and the Minotaur". The American Journal of Philology. 103 (3): 332–333, esp. 332. doi:10.2307/294479. JSTOR 294479.

- ^ Doob, Penelope Reed (April 1990). The Idea of the Labyrinth: From Classical antiquity through the Middle Ages. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-080142393-2.

- Kern (2000); Doob (1990)

- ^ "Minotaur". American English Dictionary. Collins. Retrieved 20 July 2013.

- Pausanias. Description of Greece. 2.31.1.

- Apollodorus. Library. 3.1.4.

- Hesiod. Catalogue of Women. fr. 140.

- de Simone, C. (1970). "Zu einem Beitrag über etruskisch θevru mines". Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung. 84: 221–223.

- "Apollodorus, Library, book 3, chapter 1". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Minotaur" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 555.

- Several examples are shown in Kern (2000).

- Examples include illustrations 204, 237, 238, and 371 in Kern.

- The Aeneid of Virgil, as translated by John Dryden, found at http://classics.mit.edu/Virgil/aeneid.6.vi.html . Virgil's text calls the Minotaur "biformis"; like Ovid, he does not describe which part is bull, which part man.

- "Pausanias, Description of Greece, Attica, chapter 27". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- Catullus. Carmen 64.

- Servius. On the Aeneid. 6.14.

singulis quibusque annis 'every one year'.

- The annual period is given by Zimmerman, J.E. (1964). "Androgeus". Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Harper & Row; and Rose, H.J. (1959). A Handbook of Greek Mythology. Dutton. p. 265. Zimmerman cites Virgil, Apollodorus, and Pausanias.

- "Isocrates, Helen, section 27". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 May 2023.

- Plutarch. Theseus. 15–19.Diodorus Siculus. Bibliotheca historica. i.16, iv.61.Apollodorus. Bibliotheke. iii.1, 15.

- Apollodorus. Bibliotheca. 3.1.4.

- Hogan, C. Michael (2007). Cope, Julian (ed.). "Knossos fieldnotes". The Modern Antiquarian.

- McCullough, David (2004). The Unending Mystery. Pantheon. pp. 34–36.

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Minotaur" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 18 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 555.

- Paolo Alessandro Maffei (1709), Gemmae Antiche, Pt. IV, pl. 31; Kern (2000): Maffei "erroneously deemed the piece to be from Classical antiquity".

- Kerenyi, Karl (1951). The Gods of the Greeks. p. 269.

- See illustrations of Carme, for an example of a goddess crowned with a labyrinthine wreath of grain.

- Kerényi, Karl (1976). Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. pp. 104–105, 159.

- ^ Callimachus (1921). Callimachus, Hymns and Epigrams. Translated by Mair, A.W.; Mair, G.R. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Kaplan, Matt (2012). Science of Monsters. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

- Scheffers, Anja; et al. (2008). "Late Holocene tsunami traces on the western and southern coastlines of the Peloponnesus (Greece)". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 269 (1–2): 271–279. Bibcode:2008E&PSL.269..271S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2008.02.021.

- The traverse of this circle is a long one, filling Cantos 12 to 17.

- Inferno XII, verse translation by R. Hollander, p. 228 commentary

- Alighieri, Dante. "Canto IX". Inferno.

- Boccaccio, Comedia delle ninfe fiorentine commentary

- Boccaccio, G. (30 November 2009). Boccaccio's Expositions on Dante's Comedy. University of Toronto Press.

- Bennett, Pre-Raphaelite Circle, 177–180.

- "Dante Gabriel Rossetti. His Family-Letters with a Memoir (Volume Two)". www.rossettiarchive.org.

- Beck, Christopher, "Justice among the Centaurs", Forum Italcium 18 (1984): 217–229

- Tidworth, Simon, "Theseus in the Modern World", essay in The Quest for Theseus London 1970 pp. 244–249 ISBN 0269026576

- De Laurentiis, Antonella (2009). "Los reyes: El laberinto entre mito e historia" [Los reyes: The Labyrinth Between Myth and History]. Amaltea. Revista de mitocrítica (in Spanish). 1. Universidad Complutense de Madrid: 145–155. ISSN 1989-1709.

- Bennett, Maurice J (1992). "Borges's The House of Asterion". The Explicator. 50 (3): 166–170. doi:10.1080/00144940.1992.9937945.

- "Fiction and Drama". The English Journal. 47 (9): 587–89. 1958. JSTOR 809856.

- "The Minotaur, the Wild Beast of Crete". Letter Box. Retrieved 2 May 2019.

- Jonathan English (director). Minotaur (2005). Retrieved 2 March 2018 – via AllMovie.

- Forest, Richard W. (2014). "Dungeons & Dragons, Monsters in". In Weinstock, Jeffrey (ed.). The Ashgate Encyclopedia of Literary and Cinematic Monsters. Ashgate Publishing.

- Gloyn, Liz (2019). Tracking Classical Monsters in Popular Culture. Bloomsbury Academic. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-7845-3934-4.

- Hickman, Tracy; Weis, Margaret (1987). Dragonlance Adventures. TSR, Inc. ISBN 0-88038-452-2.

- Loveridge, Sam (1 May 2020). "How to find and beat the Assassin's Creed Odyssey Minotaur". Games Radar. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- Lennox, Jesse (2 October 2020). "Assassin's Creed Odyssey: How To Find And Defeat The Minotaur". The Gamer. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- Peterson, Cody (11 September 2020). "How to Find (& Beat) The Minotaur in Assassin's Creed Odyssey". Screen Rant. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- Fekete, Bob (8 October 2018). "'Assassin's Creed Odyssey' Gates of Atlantis Guide: Where is the Minotaur, Medusa, Sphinx and Cyclops?". Newsweek. Retrieved 12 December 2024.

- MinoAnon; Nanoff. "Minotaur Hotel". Itch.io. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- Wright, Steve (6 October 2021). "Melbourne Queer Game Festival 2021 winners announced". Stevivor. Retrieved 9 August 2024.

- Macgregor, Jody (11 January 2024). "Sovereign Syndicate review". PC Gamer. Future plc. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- Kulczyński, W. (1903). "Aranearum et Opilionum species in insula Creta a comite Dre Carolo Attems collectae". Bulletin International de l'Académie des Sciences de Cracovie. 1903: 32–58.

External links

- Minotaur in Greek Myth source Greek texts and art.

- The Warburg Institute Iconographic Database (images of the Minotaur)