| Revision as of 17:05, 5 January 2010 editSimon Peter Hughes (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers16,915 edits →External links: One link doesn't exist anymore.← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 12:43, 7 January 2025 edit undoJohnbod (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, IP block exemptions, Rollbackers280,560 edits take it to talk - the "many scholars" are no doubt all AmericanTag: Manual revert | ||

| (1,000 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Group of distinguished foreigners who visited Jesus after his birth}} | |||

| :''"Three Kings", or "Three Wise Men", redirects here. For other uses, see ] and ].'' | |||

| {{redirect-several|Three Kings|Wise men|Three Wise Men}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| {{for|the novel titled ''Gaspard, Melchior & Balthazar'' in French|The Four Wise Men}}<!--While "Gaspard, Melchior & Balthazar" in https://www.gallimard.fr/Catalogue/GALLIMARD/Blanche/Gaspard-Melchior-Balthazar is used for the novel, "fr:Gaspard, Melchior et Balthazar" is used to redirect to the three wise men. "&" can be used in both French and English, so I am redirecting "Gaspard, Melchior & Balthazar" to "Biblical Magi"--> | |||

| ], ], Italy (restored during the 19th century). As here, ] usually depicts the Magi in ], which includes ], capes, and ]s.]] | |||

| In ], the '''Biblical Magi'''{{efn|{{langx|grc-x-koine|]|mágoi}}; from ] ''moɣ''(''mard''), from ] ''magu-'' 'Zoroastrian clergyman'.}} ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|eɪ|dʒ|aɪ}} {{respell|MAY|jy}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|æ|dʒ|aɪ}} {{respell|MAJ|eye}};<ref>{{Cite book |title=Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary |publisher=] |location=Nashville, Tennessee |year=2003 |page=1066 |isbn=0-8054-2836-4}}</ref> singular: {{wikt-lang|en|magus}}), also known as the '''Three Wise Men''', '''Three Kings''', and '''Three Magi''',{{efn|Sometimes referred to simply as '''Wise Men''', '''Kings''', and '''Magi'''.}} are distinguished foreigners who visit ] after his birth, bearing gifts of ], ], and ] in homage to him.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ashby |first=Chad |title=Magi, Wise Men, or Kings? It's Complicated. |url=https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/2016/december/magi-wise-men-or-kings-its-complicated.html |access-date=2024-01-11 |website=Christian History {{!}} Learn the History of Christianity & the Church |date=16 December 2016 |language=en}}</ref> They are commemorated on the ] of ]—sometimes called "Three Kings Day"—and commonly appear in the ] celebrations of ]. | |||

| In ] tradition the ''']''' ({{pron-en|ˈmeɪdʒaɪ}}; ]: μάγοι, ''magoi''), also referred to as the ('''Three''') '''Wise Men''', ('''Three''') '''Kings''', or '''Kings from the East''', are said to have visited ] after his birth, bearing gifts. In the ] , the only one to describe the visit of the magi, it states that they came "from the east" to worship the ], "born ]". Although Matthew does not mention their number, because there are three gifts it is popularly assumed that there were three Magi.<ref>], ''The Nativity: History and Legend'', London, Penguin, 2006, p22</ref> The Magi, as the "Three Kings" or "Three Wise Men" are regular figures in traditional accounts of the ] and in celebrations of ]. | |||

| The ] appear solely in the ], which states that they came "from the east" (Greek ἀπὸ ἀνατολῶν - ''apo anatolōn'') to worship the "one who has been born king of the Jews".<ref>{{bibleref2|Matthew|2:1-2}}</ref> Their names, origins, appearances, and exact number are unmentioned and derive from the inferences or traditions of later Christians.<ref name="Time">{{Cite magazine |date=2020-12-29 |title=Here's What History Can Tell Us About the Magi |url=https://time.com/5923009/three-kings-wisemen-history-magi-bible/ |access-date=2024-01-07 |magazine=TIME |language=en}}</ref> In ], they are usually assumed to have been three in number, corresponding with each gift;<ref>], ''The Nativity: History and Legend'', London, Penguin, 2006, p. 22</ref> in ], especially the ], they often number twelve.<ref>Metzger, 24 </ref> Likewise, the Magi's social status is never stated: Although some ] describe them as ], they were increasingly identified as kings by at least the third century,<ref>{{Cite web |last=Ashby |first=Chad |title=Magi, Wise Men, or Kings? It's Complicated. |url=https://www.christianitytoday.com/history/2016/december/magi-wise-men-or-kings-its-complicated.html |access-date=2024-01-11 |website=Christian History {{!}} Learn the History of Christianity & the Church |date=16 December 2016 |language=en}}</ref> which conformed with Christian interpretations of ] that the ] would be worshipped by kings.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2024-01-04 |title=Magi {{!}} Definition, Scripture, Names, Traditions, & Importance {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Magi |access-date=2024-01-07 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |title="We Three Kings" Who were the Magi? |url=https://www.catholiceducation.org/en/controversy/common-misconceptions/we-three-kings-who-were-the-magi.html |access-date=2024-01-07 |website=www.catholiceducation.org |date= 12 December 2014|language=en-gb}}</ref> | |||

| The identification of the Magi as kings is linked to Old Testament prophesies such as that in ] 60:3, which describe the Messiah being worshipped by kings.<ref> Also ] 72:10, and Psalm 68:29.</ref> Early readers reinterpreted Matthew in light of these prophecies and elevated the Magi to kings. This interpretation was common until the . | |||

| The mystery of the Magi's identities and background, combined with their theological significance, has made them prominent figures in the ]; they are venerated as saints or even martyrs in many Christian communities, and are the subject of numerous artworks, legends, and customs. Both secular and Christian observers have noted that the Magi popularly serve as a means of expressing various ideas, symbols, and themes.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Whittock |first=Martyn |date=2022-01-06 |title=Strange visitors - the significance of the magi |url=https://www.christiantoday.com/article/strange-visitors-the-significance-of-the-magi/137908.htm |access-date=2024-01-11 |website=www.christiantoday.com |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date=2021-12-16 |title=The journey of the magi is long and risky, but it ends with joy |url=https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2021/12/16/epiphany-scripture-reading-242059 |access-date=2024-01-11 |website=America Magazine |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{Cite news |title=The rule of three |url=https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2014/12/17/the-rule-of-three |access-date=2024-01-11 |newspaper=The Economist |issn=0013-0613}}</ref> Most scholars regard the Magi as ] rather than historical figures.<ref name="Birth Stories 1999 page 179">], 'The Meaning of the Birth Stories' in Marcus Borg, N T Wright, ''The Meaning of Jesus: Two Visions'' (Harper One, 1999) page 179: "I (and most mainline scholars) do not see these stories as historically factual."</ref> | |||

| ==Original account== | |||

| ==Biblical account== | |||

| The ] of Matthew 2:1-12 describes the visit of the Magi: | |||

| ], showing the Three Magi with Joseph, Mary, and Jesus.]] | |||

| Traditional ]s depict three "wise men" visiting the ] on the night of his birth, in a manger accompanied by the shepherds and angels, but this should be understood as an artistic convention allowing the two separate scenes of the ] on the birth night and the later ] to be combined for convenience.<ref>Schiller, 114</ref> The single biblical account in {{bibleverse|Matthew|2}} simply presents an event at an unspecified point after Jesus's birth in which an unnumbered party of unnamed "wise men" ({{langx|grc|μάγοι|mágoi|label=none}}) visits him in a house ({{langx|grc|οἰκίαν|oikian|label=none}}), not a stable.<ref name=Waxman></ref> The ] of ]–] describes the visit of the Magi in this manner: | |||

| {{blockquote|In the time of ], after Jesus was born in ] of ], wise men from the East came to Jerusalem, asking, "Where is the child who has been born king of the Jews? For we observed his star at its rising, and have come to pay him homage."<ref name=Waxman/> When King Herod heard this, he was frightened and all Jerusalem with him; and calling together all the chief priests and scribes of the people, he inquired of them where the Messiah was to be born. They told him, "In Bethlehem of Judea; for so it has been written by the prophet: 'And you, Bethlehem, in the land of Judah, are by no means least among the rulers of Judah; for from you shall come a ruler who is to shepherd my people Israel.{{'"}} Then Herod secretly called for the wise men and learned from them the exact time when the star had appeared. Then he sent them to Bethlehem, saying, "Go and search diligently for the child; and when you have found him, bring me word so that I may also go and pay him homage." When they had heard the king, they set out; and there, ahead of them, went the star that they had seen at its rising, until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw that the star had stopped, they were overwhelmed with joy. On entering the house, they saw the child with Mary his mother; and they knelt down and paid him homage. Then, opening their treasure chests, they offered him gifts of gold, frankincense, and myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to return to Herod, they left for their own country by another path.}} | |||

| The text specifies no interval between the birth and the visit, and artistic depictions and the closeness of the traditional dates of December 25 and January 6 encourage the popular assumption that the visit took place the same winter as the birth, but later traditions varied, with the visit taken as occurring up to two winters later. This maximum interval explained Herod's command at ]–] that the ] included boys up to two years old. Some more recent commentators, not tied to the traditional feast days, suggest a variety of intervals.<ref>Schiller, I, 96; ''The New Testament'' by Bart D. Ehrman 1999 {{ISBN|0-19-512639-4}} p. 109</ref> | |||

| Then Herod called the Magi secretly and found out from them the exact time the star had appeared. He sent them to Bethlehem and said, Go and make a careful search for the child. As soon as you find him, report to me, so that I too may go and worship him. After they had heard the king, they went on their way, and the star they had seen in the east went ahead of them until it stopped over the place where the child was. When they saw the star, they were overjoyed. On coming to the house, they saw the child with his mother Mary, and they bowed down and worshiped him. Then they opened their treasures and presented him with gifts of gold and of incense and of myrrh. And having been warned in a dream not to go back to Herod, they returned to their country by another route.</blockquote> | |||

| The wise men are mentioned twice shortly thereafter in ], in reference to their avoidance of ] after seeing Jesus, and what Herod had learned from their earlier meeting. The star which they followed has traditionally become known as the ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Visit of the Wise Men|url=https://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Matthew+2:1%E2%80%9311&version=rsv|website=Bible Gateway|access-date=May 2, 2023}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|title=Matthew 2:1–23|url=https://bible.oremus.org/?passage=Matthew%202:1%E2%80%9323&version=nrsv|website=Oremus Bible Browser|access-date=May 2, 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Description== | ==Description== | ||

| ] slab depicts the '']'', from the ] – translated as, "Severa, may you live in God", Severa being the woman buried in the sarcophagus and likely the figure to the left of the inscription.]] | |||

| The Magi are popularly referred to as ''wise men'' and ''kings''. The word ''Magi'' is a Latinization of the plural of the ] word ''magos'' (''μαγος'' pl. ''μαγοι''), itself from Old Persian ''maguŝ'' from the Avestan ''magâunô'', i.e. the religious caste in which Zoroaster was born into, (see ] 33.7:' ýâ sruyê parê '''''magâunô''''' ' = ' so I can be heard beyond '''''Magi''''' '). The term refers to the priestly ] of ].<ref>], ''A History of Zoroastrianism: The Early Period'' (Brill, 1989, 2nd ed.), vol. 1, pp. 10–11 ; Mary Boyce, ''Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices'' (Routledge, 2001, 2nd ed.), p. 48 ; Linda Murray, ''The Oxford companion to Christian art and architecture'' (Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 293; Stephen Mitchell, ''A history of the later Roman Empire, AD 284-641: the transformation of the ancient world'' (Wiley-Blackwell, 2007), p. 387 </ref> As part of their religion, these priests paid particular attention to the stars, and gained an international reputation for ], which was at that time highly regarded as a science. Their religious practices and use of astrology caused derivatives of the term ''Magi'' to be applied to the ] in general and led to the English term '']''. Translated in the ] as ''wise men'', the same translation is applied to the wise men led by ] of earlier Hebrew Scriptures ({{bibleverse||Daniel|2:48|KJV}}). The same word is given as '']'' and '']'' when describing "] the sorcerer" in {{bibleverse||Acts|13:6-11|NKJV}}, and ], considered a ] by the early Church, in {{bibleverse||Acts|8:9-13|NKJV}}. | |||

| The Magi are popularly referred to as ''wise men'' and ''kings''. The word {{lang|la|magi}} is the plural of ] {{wikt-lang|la|magus}}, borrowed from ] {{wikt-lang|grc|μάγος}} ({{transliteration|grc|magos}}),<ref>'']'', Third edition, April 2010, ''s.v.'' magus</ref> as used in the original Greek text of the Gospel of Matthew (in the plural: {{langx|grc|μάγοι|magoi|label=none}}). The Greek {{transliteration|grc|magos}} itself is derived from ] ''maguŝ,'' which in turn originated from the ] ''magâunô'', referring to the Iranian priestly ] of ].<ref>] 33.7: "ýâ sruyê parê magâunô" = "so I can be heard beyond Magi"</ref><ref>], ''A History of Zoroastrianism: The Early Period'' (Brill, 1989, 2nd ed.), vol. 1, pp. 10–11 ; Mary Boyce, ''Zoroastrians: their religious beliefs and practices'' (Routledge, 2001, 2nd ed.), p. 48 ; Linda Murray, ''The Oxford Companion to Christian Art and Architecture'' (Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 293; Stephen Mitchell, ''A History of the Later Roman Empire, AD 284–641: The Transformation of the Ancient World'' (Wiley–Blackwell, 2007), p. 387 </ref> Within this tradition, priests paid particular attention to the stars and gained an international reputation for ],<ref name="nationalgeographic.com">{{Cite web |date=2018-12-24 |title=Who were the three kings in the Christmas story? |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/three-kings-magi-epiphany |access-date=2024-01-07 |website=Culture |language=en}}</ref> which was at that time highly regarded as a science.<ref name="Time"/> Their religious practices and astrological abilities caused derivatives of the term ''Magi'' to be applied to the ] in general and led to the English term '']''. | |||

| The ] translates "magi" as ''wise men''; the same translation is applied to the wise men led by ] of earlier Hebrew Scriptures ({{bibleverse|Daniel|2:48|KJV}}). The same word is given as ''sorcerer'' and ''sorcery'' when describing "] the sorcerer" in {{bibleverse|Acts|13:6–11|KJV}}, and ], considered a ] by the early Church, in {{bibleverse|Acts|8:9–13|KJV}}. Several translations refer to the men outright as ]s at ], including ] (1961); ] (J.B.Phillips, 1972); ] (1904 revised edition); ] (1958, New Testament); ] (1935, Goodspeed); and ] (K. Taylor, 1962, New Testament). | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| Although the Magi are commonly referred to as "kings", there is nothing in the Gospel of Matthew that implies they were rulers of any kind. The identification of the Magi as kings is linked to Old Testament prophecies that describe the Messiah being worshipped by kings in ], ] {{bibleverse-nb|Psalm|68:29|KJV}}, and {{bibleverse|Psalm|72:10|KJV}}, which reads, "Yea, all kings shall fall down before him: all nations serve him."<ref>{{bibleverse|Psalm|72:11|KJV}} (King James Version)</ref><ref>"Magi". ''Encyclopædia Britannica''.</ref><ref>s.v. magi. ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (Third ed.). April 1910.</ref> Early readers reinterpreted Matthew in light of these prophecies and elevated the Magi to kings, which became widely accepted by at least 500 A.D.<ref>Drum, Walter. "." The ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 24 Dec. 2016.</ref> Later Christian interpretation stressed the ] and shepherds as the first recognition by humans of Christ as the Redeemer. However, the Protestant reformer ] was vehemently opposed to referring to the Magi as kings, writing: "But the most ridiculous contrivance of the Papists on this subject is, that those men were kings... Beyond all doubt, they have been stupefied by a righteous judgment of God, that all might laugh at gross ignorance."<ref>Ashby, Chad. "." ''Christianity Today'', December 16, 2016.</ref><ref>{{cite book | last=Calvin | first=John | author-link=John Calvin | title=Calvin's Commentaries, Vol. 31: Matthew, Mark and Luke, Part I, tr. by John King | url=http://www.sacred-texts.com/chr/calvin/cc31/cc31027.htm | access-date=2010-05-15 }} Quote from Commentary on Matthew 2:1–6</ref> | |||

| Traditions identify a variety of different names for the Magi. In the ] church they have been commonly known since the 8th century as ]<!--sic! Attention: Do not change. It is Latin-->, ], and ]. These derive from an early 6th century Greek manuscript in ].<ref>Translated into the Latin ''Excerpta Latina Barbari'': At that time in the reign of Augustus, on 1st January the Magi brought him gifts and worshipped him. The names of the Magi were Bithisarea, Melichior and Gathaspa. (). The little chronicle was probably composed in Greek in about 500 A.D.</ref> The Latin text ''Collectanea et Flores''<ref>, an old Greek document translated into Latin: Melchior was an old man with a white beard, Caspar a boy without beard, and whereas the third man, Balthasar, had a dark full beard. Latin original: Magi sunt qui munera Domino dederunt: primus fuisse dicitur Melchior, senex et canus, barba prolixa et capillis, tunica hyacinthina, sagoque mileno, et calceamentis hyacinthino et albo mixto opere, pro mitrario variae compositionis indutus: aurum obtulit regi Domino (Melchior gave gold). Secundum, nomine Caspar, juvenis imberbis, rubicundus, mylenica tunica, sago rubeo, calceamentis hyacinthinis vestitus: thure quasi Deo oblatione digna, Deum honorabat (Caspar gave frankincense). Tertius, fuscus, integre barbatus, Balthasar nomine, habens tunicam rubeam, albo vario, calceamentis inimicis amicus: per myrrham filium hominis moriturum professus est (Balthasar gave myrhh). Omnia autem vestimenta eorum Syriaca (clothes coming from Syria) sunt. (Collectanea et Flores), in: ], </ref> continues the tradition of three kings and their names and gives additional details. This text is said to be from the 8th century, of Irish origin. | |||

| == Identities and background == | |||

| Caspar is also sometimes given as Gaspar or Jaspar.<ref></ref> One candidate for the origin of the name Caspar appears in the ] as '']'' (] – c.]), i.e., Gudapharasa (from which 'Caspar' might derive as corruption of 'Gaspar'). This Gondophares declared independence from the ]s to become the first ] king and who was allegedly visited by ]. Christian legend may have chosen Gondofarr simply because he was an eastern king living in the right time period. | |||

| ]'s '']'' (12th century)]] | |||

| The names and origins of the Magi are never given in scripture, but have been provided by various traditions and legends.<ref>See Metzger, 23–29 for a lengthy account</ref> | |||

| In contrast, the ] Christians name the Magi '']'', '']'', and '']''. These names have a far greater likelihood of being originally Persian, though that does not, of course, guarantee their authenticity. | |||

| Among ], the earliest and most common names are: | |||

| In the Eastern churches, ], for instance, has ''Hor'', ''Karsudan'', and ''Basanater'', while the Armenians have ''Kagpha'', ''Badadakharida'' and ''Badadilma''.<ref name="Acta Sanct">''Acta Sanctorum'', May, I, 1780.</ref><ref name="Carols">.</ref> | |||

| Many ] believe that one of the magi came from China.<ref>Hattaway, Paul; Brother Yun; Yongze, Peter Xu; and Wang, Enoch. ''Back to Jerusalem.'' (Authentic Publishing, 2003). retrieved May 2007</ref> This final idea is used by ] in his novel ]. | |||

| * ] ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|m|ɛ|l|k|i|ɔr}};<ref name="Collins2">{{cite web|url=http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/melchior?showCookiePolicy=true|title=Melchior | |||

| ==Origin and journey== | |||

| |access-date=25 September 2014|publisher=Collins Dictionary|date=n.d.}}</ref> also Melichior).<ref name=exbar/> | |||

| * ]<!--sic! Attention: Do not change. It is Latin--> ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|æ|s|p|ər}} or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|k|æ|s|p|ɑr}};<ref name="Collins">{{cite web|url=http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/caspar?showCookiePolicy=true|title=Caspar or Gaspar | |||

| |access-date=25 September 2014|publisher=Collins Dictionary|date=n.d.}}</ref> also Gaspar, Jaspar, Jaspas, Gathaspa,<ref name=exbar/><ref name="kehrer:70">Hugo Kehrer (1908), | |||

| Kehrer's commentary: "Die Form Jaspar stammt aus Frankreich. Sie findet sich im niederrheinisch-kölnischen Dialekt und im Englischen. Note: O. Baist p. 455; J.P.Migne; Dictionnaire des apocryphes, Paris 1856, vol I, p. 1023. ... So in La Vie de St. Gilles; Li Roumans de Berte: Melcior, Jaspar, Baltazar; Rymbybel des Jakob von Märlant: Balthasar, Melchyor, Jaspas; ein altenglisches Gedicht des dreizehnten oder vierzehnten Jahrhunderts (13th century!!) Note: C.Horstmann, Altenglische Legenden, Paderborn 1875, p. 95; ... La Vie des trois Roys Jaspar Melchior et Balthasar, Paris 1498"</ref> and other variations). | |||

| * ] ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|b|æ|l|θ|ə|z|ɑr}} or {{IPAc-en|b|æ|l|ˈ|θ|æ|z|ər}};<ref name="Collins3">{{cite web|url=http://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/balthazar?showCookiePolicy=true|title=Balthasar | |||

| |access-date=25 September 2014|publisher=Collins Dictionary|date=n.d.}}</ref> also Balthasar, Balthassar, and Bithisarea).<ref name=exbar/><ref>{{cite web |title=Magi |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Magi |website=] |access-date=24 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| These names first appear in an eighth century religious chronicle, ''],'' which is a Latin translation of a lost Greek manuscript probably composed in ] roughly two centuries earlier.<ref name=exbar>: "At that time in the reign of Augustus, on 1st January the Magi brought him gifts and worshipped him. The names of the Magi were Bithisarea, Melichior and Gathaspa.".</ref> Another eighth century text, ''Collectanea et Flores'', which was likewise a Latin translation from an original Greek account, continues the tradition of three kings and their names and gives additional details.<ref name="kehrer:66">Hugo Kehrer (1908), '' Die Heiligen Drei Könige in Literatur und Kunst'' (reprinted in 1976). . . Quote from the Latin chronicle: ''primus fuisse dicitur Melchior, senex et canus, barba prolixa et capillis, tunica hyacinthina, sagoque mileno, et calceamentis hyacinthino et albo mixto opere, pro mitrario variae compositionis indutus: aurum obtulit regi Domino.'' ("the first , named Melchior, was an old white-haired man, with a full beard and hair, : the king gave gold to our Lord.") ''Secundum, nomine Caspar, juvenis imberbis, rubicundus, mylenica tunica, sago rubeo, calceamentis hyacinthinis vestitus: thure quasi Deo oblatione digna, Deum honorabat.'' ("The second, with name Caspar, a beardless boy, .") ''Tertius, fuscus, integre barbatus, Balthasar nomine, habens tunicam rubeam, albo vario, calceamentis inimicis amicus: per myrrham filium hominis moriturum professus est.'' ("The third one, dark-haired, with a full beard, named Balthasar, .") ''Omnia autem vestimenta eorum Syriaca sunt.'' ("The clothes of all were Syrian-style.")</ref><ref name=patro>''Collectanea et Flores'' in ]. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| </ref> | |||

| One candidate for the origin of the name Caspar appears in the ], which gives the account of ]'s visit to the ] ] (21– c. 47 AD), also known as Gudapharasa, from which "Caspar" might derive as corruption of "Gaspar". Gondophares had declared independence from the ]s and ruled a kingdom spanning present-day Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. According to historian Ernst Herzfeld, his name is perpetuated in the name of the Afghan city ], which he is said to have founded under the name Gundopharron.<ref>Ernst Herzfeld, ''Archaeological History of Iran'', London, Oxford University Press for the British Academy, 1935, p. 63.</ref> | |||

| The phrase ''from the east'' is the only information Matthew provides about the region from which they came. Traditionally the view developed that they were ] or ] or ] from ] as the ]s or kings of Yemen then were Jews, a view held for example by ]. The majority belief was they were from ], which was the centre of ], and hence astrology, at the time; and may have retained knowledge from the time of their Jewish leadership by ]. ] comments that the author of Matthew probably did not have a specific location in mind and the phrase ''from the east'' is for literary effect and added exoticism. | |||

| Within Eastern Christianity, the Magi have varied names. Among ], they are ''Larvandad'', ''Gushnasaph'', and ''Hormisdas;''<ref>Witold Witakowski, "The Magi in Syriac Tradition", in George A. Kiraz (ed.), ''Malphono w-Rabo d-Malphone: Studies in Honor of Sebastian P. Brock'', Piscataway (NJ), Gorgias Press, 2008, pp. 809–844.</ref> in the ], they are ''Hor'', ''Karsudan'', and ''Basanater'', while ] have ''Kagpha'', ''Badadakharida'' and ''Badadilma''.<ref name="Acta Sanct">''Acta Sanctorum'', May, I, 1780.</ref><ref name="Carols"> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090420114004/http://www.hymnsandcarolsofchristmas.com/Text/concerning_the_magi_and_their_na.htm |date=2009-04-20 }}.</ref> | |||

| According to the ], the Magi found Jesus by following a star, which thus traditionally became known as the ]. Various theories have been presented as to the nature of this star. | |||

| Many ] believe that one of the magi came from China.<ref>Hattaway, Paul; Brother Yun; Yongze, Peter Xu; and Wang, Enoch. ''Back to Jerusalem.'' (Authentic Publishing, 2003). retrieved May 2007</ref> | |||

| On finding him, they gave him three symbolic gifts: ], ] and ]. Warned in a dream that Judean king Herod intended to kill the child, they decided to return home by a different route. This prompted Herod to resort to killing all the young children in Bethlehem, an act called the ], in an attempt to eliminate a rival heir to his throne. Jesus and his family had, however, ] beforehand. After these events they passed into obscurity.<ref>Eliza Marian Butler, "''The Myth of the Magus By Eliza Marian Butler''". Cambridge University, 1993. 281 pages. Page 20. ISBN 0521437776</ref> The story of the ] in Matthew glorifies Jesus, likens him to Moses, and shows his life as fulfilling prophecy. Some critics consider this nativity story to be an invention of the author of Matthew.<ref> ], "Further light on the narratives of the Nativity". ''Novum Testamentum'' '''17'''.2 (April 1975), pp. 81-108: "Jean Danielou's conclusion that the Magi were an invention of Matthew"</ref> | |||

| === Country of origin and journey === | |||

| After the visit the Magi leave the narrative by ''returning another way'' so as to avoid Herod, and do not reappear. ] waxed lyrical on this theme, commenting that ''having come to know Jesus we are forbidden to return by the way we came''. There are many traditional stories about what happened to the Magi after this, with one having them baptised by ] on his way to ]. Another has their remains found by ] and brought to Constantinople, and eventually making their way to Germany and the ]. | |||

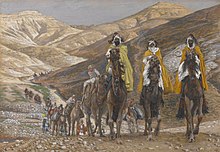

| ]: ''The Magi Journeying'' (c. 1890), ], ]]]The phrase "from the east" ({{langx|grc|ἀπὸ ἀνατολῶν|apo anatolon|label=none}}), more literally "from the rising ", is the only information Matthew provides about the region from which they came. The ], centered in ] (]), stretched from eastern Syria to the fringes of India. Though the empire was tolerant of other religions, its dominant religion was ], with its priestly ''magos'' class.<ref>{{cite book |last=Axworthy |first=Michael |year=2008 |title=A History of Iran |publisher=Basic Books |pages=31–43 }}</ref> | |||

| Although Matthew's account does not explicitly cite the motivation for their journey (other than seeing the star in the east, which they took to be the star of the King of the Jews), the ] ] states in its third chapter that they were pursuing a prophecy from their prophet, Zoradascht (Zoroaster).<ref>Hone, William (1890 (4th edit); 1820 (1st edition)). "". Archive.org. Gebbie & Co., Publishers, Philadelphia. See: Retrieved 26 January 2017.</ref> | |||

| A model for the homage of the Magi might have been provided, it has been suggested, by the journey to Rome of King ] of Armenia, with his magi, to pay homage to the Emperor Nero, which took place in 66 AD, a few years before the date assigned to the composition of the Gospel of Matthew.<ref>A. Dietrich, „“Die Weisen aus dem Morgenlande“, ''Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft,'' Bd.III, 1902, S.39 ff.; cited in J. Duchesne-Guillemin, “Die Drei Weisen aus dem Morgenlande und die Anbetung der Zeit”, ''Antaios'', Vol.VII, 1965, p. 234-252, p.245; cited in Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, ''A History of Zoroastrianism,'' Leiden, Brill, 1991, p. 453, n.449.</ref> | |||

| There is an ] tradition identifying the "Magi of Bethlehem" as ] of Arabia, ] of Persia, and ] of India.<ref>{{cite book |first1=Vrej |last1=Nersessian |year=2001 |title=The Bible in the Armenian Tradition |publisher=Getty |isbn=978-0-89236-640-8}}{{page needed|date=December 2014}}</ref> Historian ] relates a tradition in the ancient ] city of ] (in present-day Punjab, Pakistan) that one of the Magi passed through the city on the way to Bethlehem.<ref>''Historia Trium Regum'' (''History of the Three Kings'') by John of Hildesheim (1364–1375){{Specify|date=January 2012|reason=needs a page number or direct quote}}</ref> | |||

| In recent tradition the Magi have been portrayed as three kings, or noble men, of different origin. One from ] ] (usually Celtic-like from the British Isles or France), another of African Origin (usually Abyssinian, Ethiopian), the last from Asia either from the ] (e.g. Yemen or Oman) or the ] (usually China). The European is often portrayed with the Gold as the other two gifts were native to Africa and Asia so the Myrrh and Frankincense vary between "King". | |||

| Sebastian Brock, a historian of Christianity, has said: "It was no doubt among converts from Zoroastrianism that{{nbsp}}... certain legends were developed around the Magi of the Gospels".<ref>{{cite book |first1=Sebastian |last1=Brock |chapter=Christians in the Sasanian Empire: A Case of Divided Loyalties |title=Religion and National Identity |editor1-first=Stuart |editor1-last=Mews |location=Oxford |publisher=Blackwell |year=1982 |series=Studies in Church History, 18 |pages=1–19 |isbn=978-0-631-18060-9}}</ref><ref>de Villard, Ugo Monneret (1952). ''Le Leggende orientali sui Magi evangelici'', Citta del Vaticano, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana.{{page needed|date=December 2014}}</ref> And Anders Hultgård concluded that the Gospel story of the Magi was influenced by an Iranian legend concerning magi and a star, which was connected with Persian beliefs in the rise of a star predicting the birth of a ruler and with myths describing the manifestation of a divine figure in fire and light.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hultgård |first=Anders |chapter=The Magi and the Star—the Persian Background in Texts and Iconography |editor1-first=Peter |editor1-last=Schalk |editor2-first=Michael |editor2-last=Stausberg |title='Being Religious and Living through the Eyes': Studies in Religious Iconography and Iconology: A Celebratory Publication in Honour of Professor Jan Bergman |publisher=Uppsala, Almqvist & Wiksell International |year=1998 |series=Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis: Historia Religionum, 14 |pages=215–25 |isbn=978-91-554-4199-9}}</ref> | |||

| ==Gifts== | |||

| ]<!--Church of the Nativity: According to legend (= Brief der Jerusalemer Synode aus dem Jahre 836), their commander Shahrbaraz was moved by the depiction inside the church of the Three Magi wearing Persian clothing, and commanded that the building be spared: "Das Bild der anbetenden Magier in der Tracht persischer Mithraspriester, das sich am Eingang der Kirche befand"; in: http://www.bibelwissenschaft.de/wibilex/das-bibellexikon/details/quelle/WIBI/zeichen/b/referenz/10159///cache/92a2aa5065/ ; http://web.archive.org/web/20071213043957/http://www.bilderstrom.de/stmichael/fahrten/israel/israel2000/info058.html and in: Erhard Gorys, Andrea Gorys, Heiliges Land, year 2006, p. 179: Das Mosaik, das die Kirche vor der Zerstörungswut der Perser bewahrt hatte, ist nicht mehr vorhanden; auffindbar in Google unter: Brief der Jerusalemer Synode aus dem Jahre 836 --> which includes breeches, capes, and ]s. ], ca. . | |||

| <br /><small>], ], ] - restored above in 18th century.</small>]]<!-- schreibt ca. 846 im "Agnelli liber pontificalis ecclesiae Ravennatis" über den und über die von Theoderich als Hofkirche gebaute heutige Kirche S. Apollinare Nuovo: "...et magi antecedentes, munera offerentes. (Es folgen viele Detailbeschreibungen der Magier, aber keine Altersangaben)... Ex quorum amore iste beatissimus Agnellus partem endothim bissinam, unde superius fecimus mentionem, quam Maximianus praedecessor istius non explevit, '''iste magorum (h)istoriam perfecte ornavit''', et sua effigies mechanico opere aculis inserta est." - Der heilige Agnellus schmückte die Geschichte der Magier durch sein handwerkliches Bildwerk aus. - in: Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum 1: Scriptores rerum Langobardicarum et Italicarum saec. VI-IX. Herausgegeben von Georg Waitz u. a. Hannover 1878, S. 335, 88 () und in Migne Pl. ; aus: Weigand, E., Zur Datierung der kappadokischen Höhlenmalereien, in: Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 1936, Seiten 365 u. 366--> | |||

| ],'' 1375, fol. V: "This province is called ], from which came the Three Wise Kings, and they came to ] in Judaea with their gifts and worshipped Jesus Christ, and they are entombed in the city of ] two days journey from ]."]] | |||

| The Magi are described as "falling down", "kneeling" or "bowing" in the worship of ]. This gesture, together with the use of ] in Luke's birth narrative, had an important effect on Christian religious practices. They were indicative of great respect, and typically used when venerating a king. Inspired by these verses, kneeling and ] were adopted in the early Church. While prostration is now rarely practiced in the West, it is still relatively common in the Eastern Churches, especially during ]. Kneeling has remained an important element of Christian worship to this day. | |||

| A model for the homage of the Magi might have been provided, it has been suggested, by the journey to Rome of King ], with his magi, to pay homage to the ], which took place in AD 66, a few years before the date assigned to the composition of the Gospel of Matthew.<ref>A. Dietrich, "Die Weisen aus dem Morgenlande", ''Zeitschrift für die Neutestamentliche Wissenschaft'', Bd. III, 1902, p. 1 ''14; cited in J. Duchesne-Guillemin, "Die Drei Weisen aus dem Morgenlande und die Anbetung der Zeit", '']'', Vol. VII, 1965'', pp. 234–252, 245; cited in Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, ''A History of Zoroastrianism'', Leiden, Brill, 1991, p. 453, n. 449.</ref><ref>{{cite book |first1=Ernst |last1=Herzfeld |title=Archaeological History of Iran |url=https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.16474 |location=London |publisher=Oxford University Press |series=Schweich Lectures of the British Academy |year=1935 |pages=65–6 |oclc=651983281}}</ref> | |||

| Three gifts are explicitly identified in Matthew: ], ], and ] which is found only in ]. Many different theories of the meaning and symbolism of the gifts have been brought forward. While gold is fairly obviously explained, frankincense, and particularly myrrh, are much more obscure. | |||

| There was a tradition that the Central Asian ] and their Christian relatives, the ], were descended from the biblical Magi.<ref>''In regno Tarsae sunt tres provinciae, quarum dominatores se reges faciunt appellari. Homines illius patriae nominant Iogour. Semper idola coluerunt, et adhuc colunt omnes, praeter decem cognationes illorum regum, qui per demonstrationum stellae venerunt adorare nativitatem in Bethlehem Judae. Et adhuc multi magni et nobiles inveniunt inter Tartaros de cognatione illa, qui tenent firmiter fidem Christi.'' (In the kingdom of Tarsis there are three provinces, whose rulers have called themselves kings. the men of that country are called Uighours. They always worshipped idols, and they all still worship them except for the ten families of those Kings who from the appearance of the Star came to adore the Nativity in Bethlehem of Judah. And there are still many of the great and noble of those families found among the Tartars who hold firmly to the faith of Christ): Wesley Roberton Long (ed.), ''La flor de las ystorias de Orient by Hethum prince of Khorghos'', Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 1934, pp. 53, 111, 115; cited in Ugo Monneret de Villard, ''Le Leggende orientali sui Magi evangelici'', Citta del Vaticano, Biblioteca apostolica vaticana, 1952, p. 161. "The people of these countrees be named Iobgontans , and at all tymes they haue been idolaters, and so they contynue to this present day, save the nacion or kynred of those thre kynges which came to worshyp Our Lorde Ihesu Chryst at his natiuyte by demonstracyon of the sterre. And the linage of the same thre kynges be yet vnto this day great lordes about the lande of Tartary, which ferme and stedfastly beleue in the fayth of Christ": Hetoum, ''A Lytell Cronycle: Richard Pynson's Translation (c. 1520) of La Fleur des Histoires de la Terre d'Orient'', edited by Glenn Burger, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 1988, ''Of the realme of Tharsey'', p. 8, lines 29–38.</ref> This heritage passed to the Mongol dynasty of ] when ], niece of the Keraite ruler ], married ], the youngest son of Genghis, and became the mother of ] and his younger brother and successor, ]. Toghrul became identified with the legendary Central Asian Christian king ], whose Mongol descendants were sought as allies against the Muslims by contemporary European monarchs and popes.<ref>Friedrich Zarncke, "Der Priester Johannes", ''Abhandlungen der philologisch-historischen Classe der Koeniglichen Sachsischen Gesellschaft der Wissenschaften'', Leipzig, Band VII, Heft 8, 1879, S.826–1028; Band I, Heft 8, 1883, S. 1–186), re-published in one volume by G. Olms, Hildesheim, 1980.</ref> ], elder brother of King ] of ], visited the Mongol court in Karakorum in 1247–1250 and in 1254. He wrote a letter to ] King of Cyprus and Queen Stephanie (Sempad's sister) from ] in 1243, in which he said: "Tanchat ]], which is the land from whence came the Three Kings to Bethlehem to worship the Lord Jesus which was born. And know that the power of Christ has been, and is, so great, that the people of that land are Christians; and the whole land of Chata ]] believes those Three Kings. I have myself been in their churches and have seen pictures of Jesus Christ and the Three Kings, one offering gold, the second frankincense, and the third myrrh. And it is through those Three Kings that they believe in Christ, and that the Chan and his people have now become Christians."<ref>''Letter of Sempad the Constable to the King and Queen of Cyprus, 1243,'' in Henry Yule, ''Cathay and the Way Thither,'' Oxford, Hakluyt society, 1866, Vol.I, pp. cxxvii, 262–3."</ref> The legendary Christian ruler of Central Asia ] was reportedly a descendant of one of the Magi.<ref>''Fertur enim iste de antiqua progenie illorum, quorum in Evangelio mentio fit, esse Magorum, eisdemque, quibus et isti, gentibus imperans, tanta gloria et habundancia frui, ut non nisi sceptro smaragdino uti dicatur'' (It is reported that he is the descendant of those Magi of old who are mentioned in the Gospel, and to rule over the same nations as they did, enjoying such glory and prosperity that he uses no sceptre but one of emerald). Otto von Freising, ''Historia de Duabus Civitatibus'', 1146, in Friedrich Zarncke, ''Der Priester Johannes'', Leipzig, Hirzel, 1879 (repr. Georg Olms Verlag, Hildesheim and New York, 1980, p. 848; Adolf Hofmeister, Hannover. 1912, p. 366.</ref> | |||

| In her four volumes of visions of the life of Christ, ] says that the Magi came from the border between ] and ], mentioning ], "Mozian" (Iraq's ], anciently known as ]), "Sikdor" (], near ]), and a "city, whose name sounded to me something like Acajaja" (]), as well as other cities farther east.<ref name="Emmerich">{{cite book |last1=Emmerich |first1=Anne Catherine |editor1-last=Brentano |editor1-first=Clement |editor2-last=Schmöger |editor2-first=Carl E. |title=The Life of Jesus Christ and Biblical Revelations |date=1914 |publisher=Tan |location=Rockford, IL |pages=III:568, I:248, III:566, I:248 |url=https://tandfspi.org/ACE_vol_01/ACE_1_0241_out.html#ACE_1_p0248 |access-date=24 October 2022 |chapter=vols. 1, 3}}</ref> | |||

| === Later interpretations === | |||

| ]. Oil on panel. Circa 1640–1650]] | |||

| Apart from their names, the three Magi developed distinct characteristics in Christian tradition, so that between them they represented the three ages of (adult) man, three geographical and cultural areas, and sometimes other concepts. In one tradition, reflected in art by at least the 14th century—for example, in the ] by ] in 1305—Caspar is old, normally with a white beard, and gives the gold; he is "King of ], land of merchants" on the Mediterranean coast of modern Turkey, and is first in line to kneel to Christ. Melchior is middle-aged, giving frankincense from ], and Balthazar is a young man, very often and increasingly black-skinned, with myrrh from ] (modern southern Yemen). Their ages were often given as 60, 40 and 20 respectively, and their geographical origins were rather variable, with Balthazar increasingly coming from ] or other parts of Africa, and being represented accordingly.<ref>Penny, 401</ref> | |||

| Balthazar's blackness has been the subject of considerable recent scholarly attention; in art, it is found mostly in northern Europe, beginning from the 12th century, and becoming very common in the north by the 15th.<ref>Schiller, I, 113</ref> The subject of which king is which and who brought which gift is not without some variation depending on the tradition. The gift of gold is sometimes associated with Melchior as well,<ref>{{Cite web |title=Melchior {{!}} Magus, Gift, & Facts {{!}} Britannica |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Melchior |access-date=2024-01-07 |website=www.britannica.com |language=en}}</ref> and in some traditions Melchior is the oldest of the three Magi.<ref>{{Cite news |title=The rule of three |url=https://www.economist.com/christmas-specials/2014/12/17/the-rule-of-three |access-date=2024-01-11 |newspaper=The Economist |issn=0013-0613}}</ref> | |||

| ==== Gestures of respect ==== | |||

| The Magi are described as "falling down", "kneeling", or "bowing" in the worship of Jesus.<ref name="mat:202:64">{{cite web|url=http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=matthew%202;&version=64; |title=Matthew 2; – Passage Lookup – New International Version – UK |publisher=BibleGateway.com |access-date=2010-06-28}}</ref> This gesture, together with Luke's birth narrative, had an important effect on Christian religious practices.{{citation needed|date=January 2021}} They were indicative of great respect, and typically used when venerating a king. While prostration is now rarely practised in the West, it is still relatively common in the Eastern Churches, especially during ]. Kneeling has remained an important element of Christian worship to this day. | |||

| ==Gifts of the Magi== | |||

| {{redirect|Gifts of the Magi|the short story|The Gift of the Magi}} | |||

| {{redirect|Gold, frankincense, and myrrh|the film|Gold, Frankincense and Myrrh}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| | align = right | |||

| | total_width = 320 | |||

| | image1 = Gold Coin of Heiliodotos.jpg | |||

| | width1 = 800 | |||

| | height1 = 483 | |||

| | alt1 = Gold | |||

| | image2 = Olibanum_resin.jpg | |||

| | width2 = 1160 | |||

| | height2 = 1160 | |||

| | alt2 = Frankincense | |||

| | image3 = Commiphora-myrrha-resin-myrrh.jpg | |||

| | width3 = 261 | |||

| | height3 = 220 | |||

| | alt3 = Myrrh | |||

| | footer = The three gifts of the magi, left to right: gold, ] and ] | |||

| }} | |||

| Three gifts are explicitly identified in Matthew: ], ] and ]; in ], these are {{transliteration|grc|chrysós}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|χρυσός}}), {{transliteration|grc|líbanos}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|λίβανος}}) and {{transliteration|grc|smýrna}} ({{wikt-lang|grc|σμύρνα}}). There are various theories and interpretations of the meaning and symbolism of the gifts, particularly with respect to frankincense and myrrh. | |||

| The theories generally break down into two groups: | The theories generally break down into two groups: | ||

| #All three gifts are ordinary offerings and gifts given to a king. Myrrh being commonly used as an anointing oil, frankincense as a perfume, and gold as a valuable. | #All three gifts are ordinary offerings and gifts given to a king. Myrrh being commonly used as an anointing oil, frankincense as a perfume, and gold as a valuable. | ||

| #The three gifts had a spiritual meaning |

#The three gifts had a spiritual meaning: gold as a symbol of kingship on earth, frankincense (an ]) as a symbol of deity, and myrrh (an embalming oil) as a symbol of death. | ||

| #:*This dates back to ] in '']'': "gold, as to a king; myrrh, as to one who was mortal; and incense, as to a God."<ref>], '']'' .</ref> | |||

| ::*Sometimes this is described more generally as gold symbolizing virtue, frankincense symbolizing ], and myrrh symbolizing suffering. | |||

| #:*These interpretations are alluded to in the verses of the popular carol "]" in which the magi describe their gifts. The last verse includes a summary of the interpretation: "Glorious now behold Him arise/King and God and sacrifice." | |||

| #:*Sometimes this is described more generally as gold symbolizing virtue, frankincense symbolizing ], and myrrh symbolizing suffering. | |||

| ], 1568 (], ])]] | |||

| Myrrh was used as an embalming ointment and as a penitential incense in funerals and cremations until the 15th century. The "holy oil" traditionally used by the Eastern Orthodox Church for performing the sacraments of chrismation and unction is traditionally scented with myrrh, and receiving either of these sacraments is commonly referred to as "receiving the Myrrh". | |||

| Frankincense and myrrh were burned during rituals among Egyptian, Greek and Roman societies. Ancient Egyptians used myrrh to embalm corpses and Romans burned it as a type of incense at funeral pyres.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Frankincense and myrrh: Ancient scents of the season |url=https://extension.missouri.edu/news/frankincense-and-myrrh-ancient-scents-of-the-season-5906 |access-date=2023-05-27 |website=extension.missouri.edu |language=en}}</ref> Myrrh was used as an embalming ointment and as a penitential incense in funerals and cremations until the 15th century. The "holy oil" traditionally used by the ] for performing the sacraments of ] and ] is traditionally scented with myrrh, and receiving either of these sacraments is commonly referred to as "receiving the myrrh". The picture of the Magi on the 7th-century ] shows the third visitor – he who brings myrrh – with a ] over his back, a pagan symbol referring to Death.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.franks-casket.de/english/front02.html|title=Franks Casket – F – panel (Front) – Pictures: The Magi}}</ref> | |||

| It has been suggested by scholars that the "gifts" were ] rather than precious material for ].<ref>Page, Sophie,"''''". University of Toronto Press, 2004. 64 pages. ISBN 0802037976Page 18.</ref><ref>Gustav-Adolf Schoener and Shane Denson , "''''".</ref><ref>"''''". Pharmaceutical journal. Vol 271, 2003. pharmj.com.</ref> | |||

| It has been suggested by scholars that the "gifts" were ] rather than precious material for ].<ref>Page, Sophie,"''''". University of Toronto Press, 2004. 64 pages. {{ISBN|0-8020-3797-6}}, p. 18.</ref><ref>Gustav-Adolf Schoener and Shane Denson , "''''".</ref><ref>"'' {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070615120135/http://www.pharmj.com/pdf/xmas2003/pj_20031220_frankincense.pdf |date=2007-06-15 }}''". Pharmaceutical journal. Vol 271, 2003. pharmj.com.</ref> | |||

| The Syrian King Seleucus II is recorded to have offered gold, frankincense and myrrh to Apollo in his temple at Miletus in 243 BC, and this may have been the precedent for the mention of these three gifts in Gospel of Matthew (2:11). It was these three gifts, it is thought, which were the chief cause for the number of the Magi becoming fixed eventually at three.<ref>August Friedrich von Pauly et al., ''Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft,'' Vol.XVI, 1, Stuttgart, 1933, col.1145; Leonardo Olschki, “The Wise Men of the East in Oriental Traditions”, ''Semitic and Oriental Studies,'' University of California Publications in Semitic Philology, Vol.11, 1951, pp.375-395, p.380, n.46; cited in Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, ''A History of Zoroastrianism,'' Leiden, Brill, 1991, p.450, n.438.</ref> | |||

| The Syrian King ] is recorded to have offered gold, frankincense and myrrh (among other items) to ] in his temple at ] near ] in 288/7 BC,<ref>Greek inscription RC 5 (OGIS 214) – . This inscription was in the past erroneously dated to about 243 B.C.</ref> and this may have been the precedent for the mention of these three gifts in Gospel of Matthew (]). It was these three gifts, it is thought, which were the chief cause for the number of the Magi becoming fixed eventually at three.<ref>August Friedrich von Pauly et al., ''Realencyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft'', Vol. XVI, 1, Stuttgart, 1933, col. 1145; Leonardo Olschki, "The Wise Men of the East in Oriental Traditions", ''Semitic and Oriental Studies'', University of California Publications in Semitic Philology, Vol.11, 1951, pp. 375 ''395'', p. 380, n. 46; cited in Mary Boyce and Frantz Genet, ''A History of Zoroastrianism'', Leiden, Brill, 1991, p. 450, n. 438.</ref> | |||

| This episode can be linked to {{bibleverse||Isaiah|60|NRSV}} and to {{bibleverse||Psalm|72|NRSV}} which report gifts being given by kings, and this has played a central role in the perception of the Magi as kings, rather than as astronomer-priests. In a hymn of the late 4th-century ] poet ], the three gifts have already gained their medieval interpretation as prophetic ]s of Jesus' identity, familiar in the carol "]" by John Henry Hopkins, Jr., 1857. | |||

| This episode can be linked to ] and to ], which report gifts being given by kings, and this has played a central role in the perception of the Magi as kings, rather than as astronomer-priests. In a hymn of the late 4th-century ] poet ], the three gifts have already gained their medieval interpretation as prophetic ]s of Jesus' identity, familiar in the carol "]" by ], 1857. | |||

| ], ], ].</small>]] | |||

| ] suggested that the gifts were fit to be given not just to a king but to God, and contrasted them with the Jews' traditional offerings of sheep and calves, and accordingly Chrysostom asserts that the Magi worshiped Jesus as God. | ] suggested that the gifts were fit to be given not just to a king but to God, and contrasted them with the Jews' traditional offerings of sheep and calves, and accordingly Chrysostom asserts that the Magi worshiped Jesus as God. | ||

| What subsequently happened to these gifts is never mentioned in the scripture, but several traditions have developed.<ref>Lambert, John Chisholm, in ] (ed.) |

What subsequently happened to these gifts is never mentioned in the scripture, but several traditions have developed.<ref>Lambert, John Chisholm, in ] (ed.) ''A Dictionary of Christ and the Gospels''. p. 100.</ref> One story has the gold being stolen by the two thieves who were later crucified alongside Jesus. Another tale has it being entrusted to and then misappropriated by ]. One tradition suggests that Joseph and Mary used the gold to finance their travels when they fled Bethlehem after an angel had warned, in a dream, about ] plan to kill Jesus. And another story proposes the theory that the myrrh given to them at Jesus' birth was used to anoint Jesus' body after his crucifixion. | ||

| There was a 15th-century golden case purportedly containing the Gift of the Magi housed in the Monastery of St. Paul of ]. It was donated to the monastery in the 15th century by ], daughter of the ] ], wife to the ] ] ] and godmother to ] the Conqueror (of ]). After the Athens earthquake of September 7, 1999, they were temporarily displayed in ] to strengthen faith and raise money for earthquake victims. The relics were displayed in Ukraine and Belarus in Christmas of 2014, and thus left Greece for the first time since the 15th century.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://en.itar-tass.com/non-political/715098|title=Gifts of the Magi delivered to Minsk for worship|publisher=]|date=17 January 2014 |access-date=2014-01-17}}</ref> | |||

| According to the book '']'', gold symbolises the power over the material world as a king on earth, frankincense symbolises the power over the spiritual world as a deity, and myrrh symbolises the healing power over death. | |||

| ==Tombs== | |||

| ] claimed that he was shown the three tombs of the Magi at ] south of ] in the 1270s: | |||

| ==Religious significance and traditions== | |||

| <blockquote>In Persia is the city of Saba, from which the Three Magi set out and in this city they are buried, in three very large and beautiful monuments, side by side. And above them there is a square building, beautifully kept. The bodies are still entire, with hair and beard remaining.<ref name="Polo I">Polo, Marco, The Book of the Million, book i.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| {{See also|Mystery Play of the Three Magic Kings}} | |||

| Holidays celebrating the arrival of the Magi traditionally recognise a distinction between the date of their arrival and the date of Jesus' birth. The account given in the Gospel of Matthew does not state that they were present on the night of the birth; in the Gospel of Luke, Joseph and Mary remain in Bethlehem until it is time for Jesus' dedication in Jerusalem, after which they return to their home in Nazareth. | |||

| A ], according to tradition, contains the bones of the Three Wise Men. Reputedly they were first discovered by ] on her famous pilgrimage to ] and the Holy Lands. She took the remains to the church of ] in ]; they were later moved to ] (some sources say by the city's bishop, ]<ref></ref>), before being sent to their current resting place by the ] ] in ]. The Milanese celebrate their part in the tradition by holding a medieval costume parade every 6 January. | |||

| The visit of the Magi is commemorated in most ] churches separately from Christmas. The visit of the Magi is part of the ] on 6 January, which concludes the ]; on that date the Magi are also celebrated as saints. | |||

| A version of the detailed elaboration familiar to us is laid out by the 14th century cleric ]'s ''Historia Trium Regum'' ("History of the Three Kings"). In accounting for the presence in Cologne of their mummified relics, he begins with the journey of ], mother of ] to Jerusalem, where she recovered the ] and other relics: | |||

| The ] and ] celebrate the visit of the Magi on the same date as their Christmas, which is either 25 December, 6 January, or 7 January, depending on if they follow the ] or the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=ВОЛХВЫ - Древо |url=http://drevo-info.ru/articles/4743.html |access-date=2023-10-02 |website=drevo-info.ru |language=ru}}</ref> | |||

| One story in ] in the era of the late Roman Empire and early post-Islamic conquest period, the ], indicates that the Magi arrived in April (rather than January). It also implies the Magi arrived before Jesus's birth, while Mary was still pregnant, yet nevertheless a celestial child of the transformed Star of Bethlehem was able to commission them, suggesting that Jesus could be in multiple places at once.<ref>{{cite book |last=Landau |first=Brent |date=2010 |title=Revelation of the Magi: The Lost Tale of the Wise Men's Journey to Bethlehem |publisher=HarperOne |isbn= 9780062020239 |at=Introduction: The Sages and the Star-Child }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Playoust |first=Catherine |editor-last1=Edwards |editor-first1=J. Christopher |date=2022 |title=Early New Testament Apocrypha |publisher=Zondervan Academic |chapter=Revelation of the Magi |pages=175–191 |series=Ancient Literature for New Testament Studies 9 |isbn=9780310099710 }}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>Queen Helen… began to think greatly of the bodies of these three kings, and she arrayed herself, and accompanied by many attendants, went into the Land of Ind… after she had found the bodies of Melchior, Balthazar, and Gaspar, Queen Helen put them into one chest and ornamented it with great riches, and she brought them into Constantinople... and laid them in a church that is called Saint Sophia.</blockquote> | |||

| The ] does not contain Matthew's episode of the Magi. However, the Persian Muslim encyclopedist ], writing in the ninth century, gives the familiar symbolism of the gifts of the Magi, citing the late seventh century Persian-Yemenite writer ].<ref name="Munabbih2">{{cite web |title=We, three kings of Orient were |url=http://www.saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198006/we.three.kings.of.orient.were.htm |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100113083949/http://saudiaramcoworld.com/issue/198006/we.three.kings.of.orient.were.htm |archive-date=2010-01-13 |access-date=2010-06-28 |publisher=Saudiaramcoworld.com}}</ref> | |||

| ] ] châsse, ca 1200 (], Paris)]] | |||

| ===Spanish and Hispanic customs=== | |||

| ==Religious significance== | |||

| ] | |||

| The visit of the Magi is commemorated in most ] churches by the observance of ], 6 January. The ] celebrate the visit of the Magi on 25 December. | |||

| In much of the ], the Three Kings ({{lang|es|Los Reyes Magos de Oriente}}, {{lang|es|Los Tres Reyes Magos}}, or simply {{lang|es|Los Reyes Magos}}) receive letters from children and so bring them gifts on the morning of 6 January. In Spain, each one of the Magi is supposed to represent a different continent: Europe (Melchior), Asia (Caspar) and Africa (Balthasar). According to the tradition, the Magi come from the ] on their ]s to visit the houses of all the children, much like ] and ] with his ] elsewhere. | |||

| The identification of the Magi as kings is linked to Old Testament prophesies that have the Messiah being worshipped by kings in ] 60:3, ] 72:10, and Psalm 68:29. Early readers reinterpreted Matthew in light of these prophecies and elevated the Magi to kings. By ] all commentators adopted the prevalent tradition that the three were kings, and this continued until the ].{{Citation needed|date=March 2009}} | |||

| Almost every Spanish city or town organises {{lang|es|]}} in the evening of 5 January, in which the kings and their ] parade and throw sweets to the children (and parents) in attendance. The cavalcade of the three kings in ] claims to be the longest-running in the world, having started in 1886. The ] is also presented on Epiphany Eve. There is also a "Roscón" (Spain) or "Rosca de Reyes" (Mexico). | |||

| Though the ] omits Matthew's episode of the Magi, it was well known in Arabia. The Muslim encyclopaedist ], writing in the 9th century, gives the familiar symbolism of the gifts of the Magi. Al-Tabari gave his source for the information to be the later 7th century writer Wahb ibn Munabbih.<ref name="Munabbih">.</ref> | |||

| In Spain, due to the lack of a black population until recently, the role of Balthazar has often been played by an actor in ]; this practice has been criticized in the 21st century.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Edwards |first=Christian |date=2023-01-05 |title=Blackface controversy hits Spain's Three Kings parade |url=https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/blackface-spain-three-kings-parade-scli-intl/index.html |access-date=2024-12-09 |website=CNN}}</ref> | |||

| Some religious traditions take a critical view of the Magi. ]<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.watchtower.org/e/20001215/article_01.htm |title=Christmas Customs -- Are They Christian? |accessdate=2009-12-19 |date=2000-12-15 |work=Jehovah's Witnesses Official Web Site |publisher=Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania }}</ref> do not see the arrival of the Magi as something to be celebrated, but instead stress the Biblical condemnation of sorcery and astrology in such texts as ] 18:10–11, ] 19:26, and ] 47:13–14. They also point to the fact that the star seen by the Magi led them first to a hostile enemy of Jesus, and only then to the child's location — the argument being that if this was an event from God, it makes no sense for them to be led to a ruler with intentions to kill the child before taking them to Jesus.<ref> {{cite web|url=http://www.watchtower.org/library/w/2000/12/15/article_01.htm |title=Jesus' Birth The Real Story |accessdate=2009-12-19 |date=1998-12-15 |work=Jehovah's Witnesses Official Web Site |publisher=Watch Tower Bible and Tract Society of Pennsylvania }}</ref> | |||

| Not only in Spain, but also in Argentina, Mexico, Paraguay, and Uruguay, there is a long tradition of children receiving presents by the three {{lang|es|Reyes Magos}} on the night of 5 January (Epiphany Eve) or on the morning of 6 January (Epiphany day or {{lang|es|Día de Reyes}}), because it is believed that this is the day in which the Magi arrived bearing gifts for the Christ child. In most Latin American countries children also cut grass or greenery on 5 January and fill a box or their shoes with the cuttings for the Kings' camels. They then place the box or their shoes under their bed or beside the Christmas tree. On Epiphany morning the children will find the grass gone from their shoes or box and replaced with candy and other small, sweet treats. | |||

| ==Traditions == | |||

| ] | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| In Spain and most Latin American countries, which are predominantly ], the Christmas Season starts on 8 December (day of the Immaculate Conception, also known as day of the Virgin Mary) and ends with the last hour of 6 January, {{lang|es|Día de Reyes}}. In the ] ] of ], however, there are eight more days of celebration called {{lang|es|las octavitas}} (the little eight days). According to the ], the full Christmas Season is from 25 December to ] on 2 February. | |||

| {{See also|Mystery Play of the Three Magic Kings}} | |||

| In the Philippines, beliefs concerning the Three Kings (Filipino: ''Tatlóng Haring Mago'', lit. "Three Magi Kings"; shortened to ''Tatlóng Harì'' or ] {{lang|es|Tres Reyes}}) follows Hispanic influence, with the Feast of the Epiphany considered by many Filipinos as the traditional end of ]. The tradition of the Three Kings' {{lang|es|cabalgata}} is today done only in some areas, such as the old city of ] in ], and the island of ]. Another dying custom is children leaving shoes out on Epiphany Eve, so that they may receive sweets and money from the Three Kings. With the arrival of American culture in the early 20th century, the Three Kings as gift-givers have been largely replaced in urban areas by ], and they only survive in the greeting "Happy Three Kings!" and the ] ''Tatlóngharì''. The Three Kings are enshrined as ]s in the ] in ].{{citation needed|date=December 2014}} | |||

| *Holidays celebrating the arrival of the Magi traditionally recognise a sharp distinction between the date of their arrival and the date of Jesus' birth. Matthew's introduction of the Magi gives the reader no reason to believe that they were present on the night of the birth, instead stating that they arrived at some point ''after'' Jesus had been born, and the Magi are described as leading Herod to assume that Jesus is up to one year old. However, it can also be argued they went to Bethelem, as they knew the prophecy that He would be born there (Mathew 2:4-6). Joseph and Mary were there for a short period, so it is logical they arrived soon after his arrival. | |||

| ===Central Europe=== | |||

| *Western Christianity celebrates the Magi on the day of ], January 6, the day immediately following the '']'', particularly in the Spanish-speaking parts of the world. In these ]-speaking areas, the three kings (''Sp. "los Reyes Magos de Oriente"'', also "Los Tres Reyes Magos" and "Los Reyes Magos") receive wish letters from children and magically bring them gifts on the night before Epiphany. In ], each one of the Magi is supposed to represent one different continent, Europe (Caspar), Asia (Melchior) and Africa (Balthasar). According to the tradition, the Magi come from the ] on their ]s to visit the houses of all the children; much like ] with his reindeer, they visit everyone in one night. In some areas, children prepare a drink for each of the Magi, it is also traditional to prepare food and drink for the camels, because this is the only night of the year when they eat. | |||

| {{Further|Chalking the door}} | |||

| ], Poland]] | |||

| * In Spain there is a long tradition for having the children receive their Christmas presents by the three "Magos", (the figure of ] only appeared in recent years) during the night of January 5th (Biblical Magi Eve). Almost every Spanish city or town organize ]s in the evening, in which the ''kings'' and their ''servants'' parade and throw sweets to the children (and parents) in attendance. The ''cavalcade of the three kings'' in ] claims to be the oldest in the world, having started in 1886. There is also a "Roscón" as explained below. In Spain in the Biblical Magi Eve is also represented the ]. | |||

| A tradition in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, and German-speaking Catholic areas is the writing of the three kings' initials{{efn|''C+M+B'', ''C M B'', ''G+M+B'', ''K+M+B'', in those areas where Caspar is spelled Kaspar or Gašper.}} above the main door of Catholic homes in chalk. This is a new year's blessing for the occupants and the initials also are believed to also stand for "''Christus mansionem benedicat''" ("May/Let Christ Bless This House").<ref>{{cite web|url=http://catholicsensibility.wordpress.com/2006/01/05/113647675145151910/ |title=Christus Mansionem Benedicat « Catholic Sensibility |publisher=Catholicsensibility.wordpress.com |date=2006-01-05 |access-date=2012-01-12}}</ref> Depending on the city or town, this will be happen sometime between Christmas and the Epiphany, with most municipalities celebrating closer to the ]. Also in Catholic parts of the German-speaking world, these markings are made by the {{lang|de|Sternsinger}} (literally, "]") – a group of children dressed up as the magi.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.duden.de/rechtschreibung/Sternsingen |title=Duden | Sternsingen | Rechtschreibung, Bedeutung, Definition |language=de |publisher=Duden.de |date=2012-10-30 |access-date=2013-12-16}}</ref> The {{lang|de|Sternsinger}} carry a star representing the one followed by the biblical magi and sing ]s as they go door to door, such as "]". After singing, the children write the three kings' initials on the door frame in exchange for charitable donations. Each year, German and Austrian dioceses pick one charity towards which all {{lang|de|Sternsinger}} donations nationwide will be contributed.{{Citation needed|date=November 2013}} | |||

| *A tradition in most of ] involves writing the initials of the three kings' names above the main door of the home to confer blessings on the occupants for the New Year. For example, 20 + C + M + B + 08. The initials may also represent "Christus mansionem benedicat" (Christ bless this house<!--mansionem=house, apartment; benedicat=he bless-->). In Catholic parts of Germany and in Austria, this is done by so called ''Sternsinger'' (star singers), children, dressed up as the Magi, carrying the star and singing ]s. In exchange for writing the initials, they collect money for charity projects in the third world. | |||

| ]}} in ], Austria]] | |||

| *In Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, children cut grass or greenery on January 5 and put it in a box under their bed. The grass is for the camels. Children receive gifts on January 6, which is called Epiphany, and is traditionally the day in which the Magi arrived bearing gifts for the Christ child. Christmas starts in December and ends in January after Epiphany. | |||

| Traditionally, one child in the {{lang|de|Sternsinger}} group is said to represent Baltasar from Africa and so, that child typically wears blackface makeup.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02226c.htm |title=Catholic Encyclopedia: Baltasar |publisher=Newadvent.org |access-date=2013-12-16}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://black-face.com/blackface-world.htm |title=Blackface! Around the World |publisher=Black-face.com |access-date=2013-12-16}}</ref> Many Germans do not consider this to be racist because it is not intended to be a negative portrayal of a black person, but rather, a "realistic" or "traditional" portrayal of one.<ref>{{cite web |author=Reader's comment by Dieter Schmeer |title=Und die Sternsinger? – Leser-Kommentar – FOCUS Online |language=de |publisher=Focus.de |url= http://www.focus.de/kultur/kunst/und-die-sternsinger-theater-fans-werfen-dieter-hallervorden-rassismus-vor-kommentar_4064052.html |access-date=2013-12-16 |url-status= dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20131203005748/http://www.focus.de/kultur/kunst/und-die-sternsinger-theater-fans-werfen-dieter-hallervorden-rassismus-vor-kommentar_4064052.html |archive-date= 2013-12-03}}</ref> The dialogue surrounding the politics of traditions involving blackface is not as developed as in Spain or the Netherlands.{{Citation needed|date=January 2016}} In the past, photographs of German politicians together with children in blackface have caused a stir in English-language press.<ref>{{cite web |title= German Chancellor Angela Merkel poses with children in blackface for Three King's Day celebration |date=5 January 2013 |publisher=NY Daily News |url= http://www.nydailynews.com/news/world/germany-merkel-xmas-blackface-flap-article-1.1233851 |access-date= 2013-12-16}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title= Angela Merkel pictured with blacked-up children |publisher=Telegraph |date= 2013-01-04 |url-access=subscription |url= https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/germany/9781976/Angela-Merkel-pictured-with-blacked-up-children.html |access-date= 2013-12-16 |archive-url= https://ghostarchive.org/archive/20220110/https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/germany/9781976/Angela-Merkel-pictured-with-blacked-up-children.html |archive-date= 2022-01-10 |url-status=live}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Moreover, Afro-Germans have written that this use of blackface is a missed opportunity to be truly inclusive of Afro-Germans in German-speaking communities and contribute to the equation of "blackness" with "foreignness" and "otherness" in German culture.<ref>{{cite web |author= Ücgür, Ogdan |title= Sternsinger: Schwarzes Gesicht und weisse Hände |publisher= M-Media |date= 2012-01-06 |url= http://www.m-media.or.at/blog/sternsinger-wo-sind-die-schwarzen-kinder/ |access-date=2013-12-16}}</ref> | |||

| === Roscón de Reyes === | |||

| {{Main|Roscón de Reyes}} | |||

| In 2010, Epiphany was made a holiday in Poland, thus reviving a pre-World War II tradition.<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,114873,8686262,Trzech_Kroli_juz_swietem_panstwowym.html |title=Trzech Króli już świętem państwowym |trans-title=Three Kings already a public holiday |language=pl |access-date=2016-11-21 |archive-date=2016-11-21 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161121233702/http://wiadomosci.gazeta.pl/wiadomosci/1,114873,8686262,Trzech_Kroli_juz_swietem_panstwowym.html |url-status=dead}}</ref> Since 2011, celebrations with biblical costuming have taken place throughout the country. For example, in Warsaw there are processions from ] down ] to ].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://orszak.org/warszawa/ |title=Orszak Trzech Króli | Warszawa |publisher=Orszak.org |date=2013-01-01 |access-date=2013-07-04 |url-status = dead|archive-url=https://archive.today/20130415132105/http://orszak.org/warszawa/ |archive-date=2013-04-15}}</ref> | |||

| *In France and Belgium, the holiday is celebrated with a special tradition: within a family, a cake is shared, which contains a small figure of baby Jesus, known as the broad bean. Whoever gets the "bean" is "crowned" king for the remainder of the holiday and wears a cardboard crown purchased with the cake. The practice is known as ''tirer les Rois'': drawing the Kings. A queen is sometimes also chosen. | |||

| ===Cake=== | |||

| *This tradition also exists in ], but with one small variant; the cake, in this case actually a ring-shaped pastry or ''Roscón de Reyes'', is most commonly bought, not baked, and it contains a small ] of a baby Jesus (or another present depending on the region) and a dry ]. The one who gets the figurine is crowned, but whoever gets the bean has to pay the value of the cake to the person who originally bought it. This is eaten on January 6th. | |||

| {{main|King cake}} | |||

| In Spain and Portugal, a ring-shaped cake (in Portuguese: {{lang|pt|]}}<ref> {{webarchive|url=http://arquivo.pt/wayback/20100601042822/http://www.matosinhoshoje.com/index.asp?idEdicao%3D448 |date=2010-06-01 }} Matosinhos Hoje, 6 January 2010.</ref>) contains both a small ] of one of the Magi (or another surprise depending on the region) and a dry ]. The one who gets the figurine is "crowned" (with a crown made of cardboard or paper), but whoever gets the bean has to pay the value of the cake to the person who originally bought it. In Mexico they also have the same ring-shaped cake {{lang|es|Rosca de Reyes}} (Kings Bagel or Thread) with figurines inside it. Whoever gets a figurine is supposed to organize and be the host of the family celebration for the '']'' feast on February 2. | |||

| *In Mexico they have the same ring-shaped cake ''Rosca de Reyes'' (Kings Bagel or Thread), it contains figurines of the baby Jesus. The figurine of the baby Jesus is typically hidden inside the cake. Whoever gets a figurine is supposed to take the figurine to the local church and buy tamales for the ''Candelaria feast'' on February the second, which is the feast of the presentation of Jesus at the Temple. | |||

| In France and Belgium, a cake containing a small figure of the baby Jesus, known as the "broad bean", is shared within the family. Whoever gets the bean is crowned king for the remainder of the holiday and wears a cardboard crown purchased with the cake. A similar practice is common in many areas of Switzerland, but the figurine is a miniature king. The practice is known as {{lang|fr|tirer les Rois}} (Drawing the Kings). A queen is sometimes also chosen. | |||

| *In ], Louisiana, parts of south Texas, and surrounding regions, a similar ring-shaped cake known as a "King Cake" traditionally becomes available in bakeries from the Epiphany through Mardi Gras. The baby Jesus is represented by a small, plastic doll inserted into the cake from underneath, and the person who gets the slice with the figurine is expected to buy or bake the next King Cake. There is wide variation among the types of pastry that can be called a King Cake, but most feature baked cinnamon-flavored twisted dough, thin frosting, with additional sugar on top in the traditional Mardi Gras colors of gold, green, and purple. To prevent accidental injury or choking, the plastic doll is frequently not hidden in the cake at the bakery, but instead included in the packaging for optional use. Mardi Gras-style beads and doubloons may be included as well. | |||

| In ], ], parts of southern ], and surrounding regions, a similar ring-shaped cake known as a "]" traditionally becomes available in bakeries from Epiphany to ]. The baby Jesus figurine is inserted into the cake from underneath, and the person who gets the slice with the figurine is expected to buy or bake the next King Cake. There is wide variation among the types of pastry that may be called a King Cake, but most are a baked cinnamon-flavoured twisted dough with thin frosting and additional sugar on top in the ] of gold, green and purple. To prevent accidental injury or choking, the baby Jesus figurine is frequently not inserted into the cake at the bakery, but included in the packaging for optional use by the buyer to insert it themselves. Mardi Gras-style beads and ]s may be included as well. | |||

| ==Adoration of the Magi in art== | |||

| {{Main|Adoration of the Magi in Art}} | |||

| ] and ].]] | |||

| The Magi most frequently appear in European art in the ''Adoration of the Magi''; less often ''The Journey of the Magi'' has been a popular '']'', and other scenes such as the ''Magi before Herod'' and the ''Dream of the Magi'' also appear in the Middle Ages. In Byzantine art they are depicted as Persians, wearing trousers and ]s. Crown appear from the 10th century. Medieval artists also ] the theme to represent the three ]. Beginning in the 12th century, and very often by the 15th, the Kings also represent the three parts of the known (pre-Columbian) world in Western art, especially in Northern Europe. Balthasar is thus represented as a young African or ] and Caspar may be depicted with distinctive ] features. | |||

| === Martyrdom traditions === | |||