| Revision as of 04:42, 14 February 2010 edit98.87.71.208 (talk) cite calivn and hobbs← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:46, 12 February 2024 edit undo2603:8001:5900:1e2e:89f4:4e03:9af7:9f8c (talk)No edit summary | ||

| (73 intermediate revisions by 44 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Type of cheeky postcard}} | |||

| {{ |

{{More citations needed|date=February 2007}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| '''Vinegar valentines''' |

'''Vinegar valentines''' were a type of cheeky ] decorated with a ] and insulting poem. A lampoon of ] cards, the unflattering ]s enjoyed a century of popularity beginning in the 1840s during the ]. | ||

| These cynical, sarcastic, often mean-spirited cards were first produced in America by a variety of printing companies, including Elton, Fisher, Strong and Turner. By the 1870s, other entrepreneurs such as New York printer, John McLoughlin, and his cartoonist, Charles Howard were creating their own lines of cards. While different European companies also produced the humorous cards in the early 19th century, one of the most prestigious firms to create them around 1900 was ], "Publishers to Their Majesties the {{sic|King and Queen of England"}}. | |||

| ⚫ | The cards are usually simply a sheet of thin, colored paper, about the |

||

| Cheaply made, vinegar valentines were usually printed on one side of a single sheet of paper and cost only a penny. Some people mistakenly call them ],<ref>{{cite web|last1=Zarrelli|first1=Natalie|title=The Rude, Cruel, and Insulting 'Vinegar Valentines' of the Victorian Era|url=https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/vinegar-valentines-victorian|website=Atlas Obscura|language=en|date=8 February 2017}}</ref> but that term refers to a form of ] fiction. They often featured garish caricatures of men like the "Dude" or women like the "Floozy." One reason they rapidly became popular throughout America and Europe was because literacy rates were increasing at that time among the poor and working classes who rarely had much more than a penny to spend on such luxuries. But, according to noted valentine authority Nancy Rosin, president of the National Valentine Collectors Association, their use wasn't restricted to the lower economic classes. | |||

| The cards were first produced in the late ] and enjoyed their greatest popularity in that period and in the first quarter of the 20th century. | |||

| The unflattering cards reportedly created a stir throughout all social levels, sometimes provoking fisticuffs and arguments. The receiver, not the sender, was responsible for the cost of postage up until the 1840s. A person in those days paid for the privilege of being insulted by an often anonymous "admirer." Millions of vinegar valentines, with verses that insulted a person's looks, intelligence, or occupation, were sold between the 19th and 20th centuries. Art and design historian Annebella Pollen has extensively researched their production and reception in Britain, where they were more commonly called 'mock' or 'mocking' valentines.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Pollen|first1=Annebella|title='The Valentine has fallen upon evil days': Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque|journal=Early Popular Visual Culture|date=21 August 2014|volume=12|issue=2|pages=127–173|doi=10.1080/17460654.2014.924212|s2cid=191554821|url=http://eprints.brighton.ac.uk/13357/1/EPVC%20-%20The%20Valentine%20has%20Fallen%20Upon%20Evil%20Days%20-%20for%20repository.pdf}}</ref> | |||

| Some people mistakenly call them ], although that term in fact refers to a form of ] fiction. | |||

| ⚫ | The cards are usually simply a sheet of thin, colored paper, about the size of a modern greeting card. They were later also produced in the form of postcards. They were usually sent anonymously. Postmasters sometimes confiscated these cards as unfit to be mailed.<ref>{{cite web|first=Alan |last=Petrulis |url=http://www.metropostcard.com/topicalsv.html |title=MetroPostcard Topicals V |publisher=Metropostcard.com |date= |accessdate=2012-02-23}}</ref> | ||

| One ] reference to vinegar valentines is found in ]'s ] comic strip. Calvin often gives ] vinegar valentines so as to hide his true affections for her under a veil of immature distaste.<ref>http://lesinge.org/ch/index.php?y=&m=&d=&str=valentine&search=Search</ref> | |||

| ==In popular culture== | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| One ] reference to vinegar valentines is found in the ] comic strip '']'', where Calvin has given ] the cards. | |||

| ] | |||

| References | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| <references/> | |||

| * {{cite journal|last=Martinelli|first=Patricia|title=Valentines day greeting cards |journal=Antiques & Collecting}} | |||

| * {{cite journal|last=Martinelli|first=Patricia|title=How don't I love thee? |journal=Antiques & Collecting |date=February 2008 |volume=112 |issue=12 |pages=30–35}} | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| Other Links | |||

| * | |||

| * Collectors' Weekly | |||

| * Brighton Museums | |||

| * Early Popular Visual Culture | |||

| * BBC | |||

| {{culture-stub}} | |||

| ⚫ | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:46, 12 February 2024

Type of cheeky postcard| This article needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. Find sources: "Vinegar valentines" – news · newspapers · books · scholar · JSTOR (February 2007) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

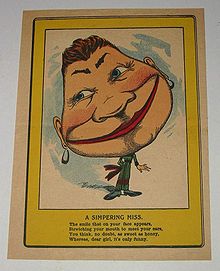

Vinegar valentines were a type of cheeky postcard decorated with a caricature and insulting poem. A lampoon of Valentine's Day cards, the unflattering novelty items enjoyed a century of popularity beginning in the 1840s during the Victorian era.

These cynical, sarcastic, often mean-spirited cards were first produced in America by a variety of printing companies, including Elton, Fisher, Strong and Turner. By the 1870s, other entrepreneurs such as New York printer, John McLoughlin, and his cartoonist, Charles Howard were creating their own lines of cards. While different European companies also produced the humorous cards in the early 19th century, one of the most prestigious firms to create them around 1900 was Raphael Tuck & Sons, "Publishers to Their Majesties the King and Queen of England" [sic].

Cheaply made, vinegar valentines were usually printed on one side of a single sheet of paper and cost only a penny. Some people mistakenly call them penny dreadfuls, but that term refers to a form of potboiler fiction. They often featured garish caricatures of men like the "Dude" or women like the "Floozy." One reason they rapidly became popular throughout America and Europe was because literacy rates were increasing at that time among the poor and working classes who rarely had much more than a penny to spend on such luxuries. But, according to noted valentine authority Nancy Rosin, president of the National Valentine Collectors Association, their use wasn't restricted to the lower economic classes.

The unflattering cards reportedly created a stir throughout all social levels, sometimes provoking fisticuffs and arguments. The receiver, not the sender, was responsible for the cost of postage up until the 1840s. A person in those days paid for the privilege of being insulted by an often anonymous "admirer." Millions of vinegar valentines, with verses that insulted a person's looks, intelligence, or occupation, were sold between the 19th and 20th centuries. Art and design historian Annebella Pollen has extensively researched their production and reception in Britain, where they were more commonly called 'mock' or 'mocking' valentines.

The cards are usually simply a sheet of thin, colored paper, about the size of a modern greeting card. They were later also produced in the form of postcards. They were usually sent anonymously. Postmasters sometimes confiscated these cards as unfit to be mailed.

In popular culture

One pop culture reference to vinegar valentines is found in the Bill Watterson comic strip Calvin and Hobbes, where Calvin has given Susie Derkins the cards.

References

- Zarrelli, Natalie (8 February 2017). "The Rude, Cruel, and Insulting 'Vinegar Valentines' of the Victorian Era". Atlas Obscura.

- Pollen, Annebella (21 August 2014). "'The Valentine has fallen upon evil days': Mocking Victorian valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque" (PDF). Early Popular Visual Culture. 12 (2): 127–173. doi:10.1080/17460654.2014.924212. S2CID 191554821.

- Petrulis, Alan. "MetroPostcard Topicals V". Metropostcard.com. Retrieved 2012-02-23.

- Martinelli, Patricia. "Valentines day greeting cards". Antiques & Collecting.

- Martinelli, Patricia (February 2008). "How don't I love thee?". Antiques & Collecting. 112 (12): 30–35.

External links

- Vinegar Valentines: A mean note on day of love

- Happy Valentine's Day: I Hate You Collectors' Weekly

- Love Letters and Hate Mail Brighton Museums

- "The valentine has fallen upon evil days:" mocking Victorian Valentines and the ambivalent laughter of the carnivalesque Early Popular Visual Culture

- Eight incredibly offensive Victorian valentines BBC