| Revision as of 17:13, 16 March 2010 view sourceColchicum (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers19,162 edits →Khrushchev, Eisenhower and De-Stalinization← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 03:55, 7 January 2025 view source Terrainman (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users1,192 edits Undid revision 1267803257 by Goszei (talk) The cold war nuclear arms race was is usually referred to as 'the nuclear arms race' due to its historical prominenceTag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Geopolitical tension between US and USSR}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef|small=yes|expiry=January 19, 2009}} | |||

| {{About|the state of political tension in the 20th century|the general term|Cold war (term)|other uses|Cold War (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{other}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Cold Warrior}} | |||

| ] ] ] (left) and ] ] ] meet in 1985.]] | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| {{History Of The Cold War}} | |||

| {{pp-move}} | |||

| The '''Cold War''' ({{lang-ru|Холо́дная война́}}) (1947–1991) was the continuing state of political conflict, military tension, proxy wars, and economic competition existing after ] (1939–1945), primarily between the ] and its ]s, and the powers of the ], particularly the ]. Although the primary participants' military forces never officially clashed directly, they expressed the conflict through military coalitions, strategic conventional force deployments, extensive aid to states deemed vulnerable, ]s, espionage, propaganda, a ] ], economic and technological competitions, such as the ]. | |||

| {{Use American English|date=November 2024}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=March 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox | |||

| | subheader = ] – ]{{efn-ua|{{harvnb|Service|2015|p={{pn|date=August 2024}}}}: "Historians do not fully agree on its starting and ending points, but the period is generally considered to span from the announcement of the ] on 12 March 1947 to the ] on 26 December 1991."}} <br />({{Age in years, months, weeks and days|month1=3|day1=12|year1=1947|month2=12|day2=12|year2=1991}})<br/>Part of the ] | |||

| | above = Cold War | |||

| | abovestyle = background-color:#C3D6EF;font-size:110% | |||

| | subheaderstyle = background-color:#DCDCDC | |||

| | image1 = ] | |||

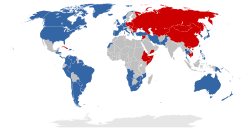

| | caption1 = {{legend inline|#3465A4|]}} and {{legend inline|#D40000|]}} states during the Cold War era | |||

| | image2 = ] | |||

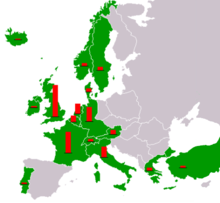

| | caption2 = The "]" of the Cold War era, between 30 April and 24 June 1975: | |||

| {{leftlegend|#3465A4|]: ] led by the ] and its allies}} | |||

| {{leftlegend|#D40000|]: ] led by the ], ] (]), and their allies}} | |||

| {{leftlegend|#C0C0C0|]: ] and ]}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{History of the Cold War}} | |||

| The '''Cold War''' was a period of global ] tension and struggle for ideological dominance and economic influence between the ] and the ] (USSR) and their respective allies, the ] and the ]. It started in 1947 and lasted until the ] in 1991. The term '']'' is used because there was no direct fighting between the two ]s, though each supported opposing sides in major regional conflicts known as ]s. Aside from the ] and conventional ], the struggle for supremacy was expressed indirectly via ], ]s, ], far-reaching ], ], and technological competitions such as the ]. | |||

| After ], the USSR installed ] in the territories of Eastern and Central Europe it had occupied, promoted the spread of ] to ] in 1948, and created an alliance with the ] in 1949. The US declared the ] of "]" in 1947, launched the ] in 1948 to assist in Western Europe's economic recovery, and founded the ] military alliance in 1949 (which was matched by the Soviet-led ] in 1955). A major proxy war was the ] of 1950 to 1953, which ended in stalemate. | |||

| Despite being ] against the ] and having the most powerful military forces among peer nations, the USSR and the US disagreed about the configuration of the post-war world while occupying most of ]. The Soviet Union created the ] with the eastern European countries it occupied, annexing some as ] and maintaining others as satellite states, some of which were later consolidated as the ] (1955–1991). The US and some western European countries established ] of ] as a defensive policy, establishing alliances such as ] to that end. | |||

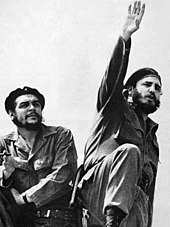

| ] included support for ] and ]s, governments, and uprisings across the world, while ] included the funding of ], ], revolutions and dictatorships. As nearly all the colonial states underwent ] and achieved independence in the period from 1945 to 1960, many became Third World battlefields in the Cold War. The ] of 1959 installed the first communist regime in the Western Hemisphere, and in 1962, the ] began after deployments of U.S. missiles in Europe and Soviet missiles in Cuba; it is considered ] the Cold War came to escalating into ]. Another major proxy conflict was the ] of 1955 to 1975, which ended in defeat for the U.S. | |||

| Several such countries also coordinated the ], especially in ], which the USSR opposed. Elsewhere, in ] and ], the USSR assisted and helped foster ]s, opposed by several Western countries and their regional allies; some they attempted to ], with mixed results. Some countries aligned with NATO and the Warsaw Pact, and others formed the ]. | |||

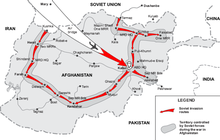

| The USSR solidified its domination of Eastern Europe with the crushing of the ] in 1956 and the ] in 1968. Both powers used economic aid in an attempt to win the loyalty of ]. After the ] between the USSR and China in 1961, the U.S. intervened before Soviet's ] and ]. In the same year, the US and USSR signed a series of arms control treaties limiting their nuclear arsenals. In 1979, the toppling of pro-US governments in ] and ] and a ] again raised fears of war. In 1985, ] rose to leader of the USSR and expanded political freedoms in his country, which led to the ] in 1989 and the ] in 1991. | |||

| The Cold War featured periods of relative calm and of international high tension – the ] (1948–1949), the ] (1950–1953), the ], the ] (1959–1975), the ] (1962), the ] (1979–1989), and the ] NATO exercises in November 1983. Both sides sought ] to relieve political tensions and deter direct military attack, which would likely guarantee their ] with ]s. | |||

| ==Terminology== | |||

| {{Main|Cold war (term)}} | |||

| Writer ] used '']'', as a general term, in his essay "You and the Atomic Bomb", published 19 October 1945. Contemplating a world living in the shadow of the threat of ], Orwell looked at ]'s predictions of a polarized world, writing: | |||

| In the 1980s, the United States increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressures against the USSR, which had already suffered ]. Thereafter, Soviet President ] introduced the liberalizing reforms of '']'' ("reconstruction", "reorganization", 1987) and '']'' ("openness", ca. 1985). The Cold War ended after ] in 1991, leaving the United States as the dominant military power, and ] possessing most of the Soviet Union's nuclear arsenal. The Cold War and its events have had a significant impact on the world today, and it is commonly referred to in popular culture. | |||

| {{blockquote|Looking at the world as a whole, the drift for many decades has been not towards anarchy but towards the reimposition of slavery... James Burnham's theory has been much discussed, but few people have yet considered its ideological implications—that is, the kind of world-view, the kind of beliefs, and the social structure that would probably prevail in a state which was at once unconquerable and in a permanent state of "cold war" with its neighbours.{{sfn|Orwell|1945}}}} | |||

| In '']'' of 10 March 1946, Orwell wrote, "after the Moscow conference last December, Russia began to make a 'cold war' on Britain and the British Empire."{{sfn|Orwell|1946}} | |||

| ==Origins of the term== | |||

| The first use of the term ''Cold War'' <ref>"“Cold War” – noun . . . (3) (initial capital letters) rivalry after World War II between the Soviet Union and its satellites and the democratic countries of the Western world, under the leadership of the United States." ''Dictionary'', unabridged, based on the Random House Dictionary, 2009</ref> describing the post–World War II ] tensions between the USSR and its Western European Allies is attributed to ], a US financier and presidential advisor.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=54}}</ref> In South Carolina, on April 16, 1947, he delivered a speech (by journalist ])<ref>{{cite news|first=William|last=Safire|year=2006|url=http://www.iht.com/articles/2006/10/01/news/edsafire.php|title=Islamofascism Anyone?|work=]|publisher=]|date=October 1, 2006|accessdate=December 25, 2008}}</ref> saying, “Let us not be deceived: we are today in the midst of a cold war.”<ref>'', history.com, April 16, 1947. Retrieved on July 2, 2008.</ref> Newspaper reporter-columnist ] gave the term wide currency, with the book ''Cold War'' (1947).<ref>{{cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=Ydc3AAAAIAAJ&q=walter+lippmann+cold+war&dq=walter+lippmann+cold+war&pgis=1|author=Lippmann, Walter|title=Cold War|accessdate=2008-09-02|publisher=Harper|year=1947}}</ref> | |||

| The first use of the term to describe the specific ] geopolitical confrontation between the Soviet Union and the United States came in a speech by ], an influential advisor to Democratic presidents,{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=54}} on 16 April 1947. The speech, written by journalist ],{{sfn|Safire|2006}} proclaimed, "we are today in the midst of a cold war."{{sfn|Glass|2016}} Newspaper columnist ] gave the term wide currency with his book ''The Cold War''. When asked in 1947 about the source of the term, Lippmann traced it to a French term from the 1930s, {{lang|fr|la guerre froide}}.{{sfn|Talbott|2009|p=441 n. 3}}{{efn-ua|Lippmann's own book is {{cite book |last=Lippmann |first=Walter |title=The Cold War |publisher=Harper |isbn=9780598864048 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Ydc3AAAAIAAJ |date=1947}}}} | |||

| Previously, during the war, ] used the term ''Cold War'' in the essay “You and the Atomic Bomb” published October 19, 1945, in the British newspaper '']''. Contemplating a world living in the shadow of the threat of nuclear war, he warned of a “peace that is no peace”, which he called a permanent “cold war”,<ref>{{cite book| last=Kort| first =Michael| title= The Columbia Guide to the Cold War|publisher= Columbia University Press| date =2001|pages =3}}</ref> Orwell directly referred to that war as the ideological confrontation between the Soviet Union and the Western powers.<ref>{{cite book| last=Geiger| first =Till| title= Britain and the Economic Problem of the Cold War|publisher= Ashgate Publishing| date =2004|pages =7}}</ref> Moreover, in ''The Observer'' of March 10, 1946, Orwell wrote that “. . . fter the Moscow conference last December, Russia began to make a ‘cold war’ on Britain and the British Empire.”<ref>Orwell, George, ''The Observer'', March 10, 1946</ref> | |||

| ==Background== | ==Background and periodization== | ||

| {{Main|Origins of the Cold War}} | {{Main|Origins of the Cold War}} | ||

| {{For timeline|Timeline of the Cold War}} | |||

| {{see|Red Scare}} | |||

| ], August 1918, during the ]]] | |||

| There is disagreement among historians regarding the starting point of the Cold War. While most historians trace its origins to the period immediately following World War II, others argue that it began towards the end of ], although tensions between the ], other European countries and the United States date back to the middle of the 19th century.<ref name="Gaddis"/> | |||

| The roots of the Cold War can be traced to diplomatic and military tensions preceding World War II. The 1917 ] and the subsequent ], where Soviet Russia ceded vast territories to Germany, deepened distrust among the Western Allies. Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War further complicated relations, and although the Soviet Union later allied with Western powers to defeat ], this cooperation was strained by mutual suspicions. | |||

| As a result of the 1917 ] in Russia (followed by its withdrawal from ]), Soviet Russia found itself isolated in international diplomacy.<ref name="lee">{{Harvnb|Lee|1999|p=57}}</ref> Leader ] stated that the Soviet Union was surrounded by a "hostile capitalist encirclement", and he viewed diplomacy as a weapon to keep Soviet enemies divided, beginning with the establishment of the Soviet ], which called for revolutionary upheavals abroad.<ref name="tucker34">{{Harvnb|Tucker|1992|p=34}}</ref> | |||

| In the immediate aftermath of World War II, disagreements about the future of Europe, particularly ], became central. The Soviet Union's establishment of communist regimes in the countries it had liberated from Nazi control—enforced by the presence of the ]—alarmed the US and UK. Western leaders saw this as Soviet expansionism, clashing with their vision of a democratic Europe. Economically, the divide was sharpened with the introduction of the ] in 1947, a US initiative to provide financial aid to rebuild Europe and prevent the spread of communism by stabilizing capitalist economies. The Soviet Union rejected the Marshall Plan, seeing it as an effort by the US to impose its influence on Europe. In response, the Soviet Union established ] (Council for Mutual Economic Assistance) to foster economic cooperation among communist states. | |||

| Subsequent leader ], who viewed the Soviet Union as a "socialist island", stated that the Soviet Union must see that "the present capitalist encirclement is replaced by a socialist encirclement."<ref name="tucker46">{{Harvnb|Tucker|1992|p=46}}</ref> As early as 1925, Stalin stated that he viewed international politics as a bipolar world in which the Soviet Union would attract countries gravitating to socialism and capitalist countries would attract states gravitating toward capitalism, while the world was in a period of "temporary stabilization of capitalism" preceding its eventual collapse.<ref name="tucker47">{{Harvnb|Tucker|1992|p=47-8}}</ref> | |||

| The United States and its ]an allies sought to strengthen their bonds and used the policy of ] against Soviet influence; they accomplished this most notably through the formation of ], which was essentially a defensive agreement in 1949. The Soviet Union countered with the ] in 1955, which had similar results with the Eastern Bloc. As by that time the Soviet Union already had an armed presence and political domination all over its eastern satellite states, the pact has been long considered superfluous.{{sfn|Crump|2015|pp=1, 17}} Although nominally a defensive alliance, the Warsaw Pact's primary function was to safeguard ] over its ]an satellites, with the pact's only direct military actions having been the invasions of its own member states to keep them from breaking away;{{sfn|Crump|2015|p=1}} in the 1960s, the pact evolved into a multilateral alliance, in which the non-Soviet Warsaw Pact members gained significant scope to pursue their own interests.<!--https://www.routledge.com/The-Warsaw-Pact-Reconsidered-International-Relations-in-Eastern-Europe/Crump/p/book/9781138102132--> In 1961, Soviet-allied ] constructed the ] to prevent the citizens of ] from fleeing to ], at the time part of United States-allied ].{{sfn|Reinalda|2009|p=369}} Major crises of this phase included the ] of 1948–1949, the ] of 1945–1949, the ] of 1950–1953, the ] and the ] of that same year, the ], the ] of 1962, and the ] of 1955–1975. Both superpowers competed for influence in ] and the ], and the decolonising states of ], ], and ]. | |||

| Several events fueled suspicion and distrust between the western powers and the Soviet Union: the Bolsheviks' challenge to capitalism;<ref name = "Halliday">{{Harvnb|Halliday|2001|p=2e}}</ref> the 1926 Soviet funding of a British general workers strike causing Britain to break relations with the Soviet Union;<ref name="tucker74">{{Harvnb|Tucker|1992|p=74}}</ref> Stalin's 1927 declaration that peaceful coexistence with "the capitalist countries . . . is receding into the past";<ref name="tucker75">{{Harvnb|Tucker|1992|p=75}}</ref> conspiratorial allegations in the ] of a planned French and British-led ];<ref name="tucker98">{{Harvnb|Tucker|1992|p=98}}</ref> the ] involving a series of campaigns of political repression and persecution in which over half a million Soviets were executed;<ref name=Pipes>Communism: A History (Modern Library Chronicles) by ], pg 67</ref> the ] including allegations of British, French, Japanese and German espionage;<ref name="christenson308">{{Harvnb|Christenson|1991|p=308}}</ref> the controversial death of 6-8 million people in the ] in the ]; western support of the ] in the ]; the US refusal to recognize the Soviet Union until 1933;<ref name = "Lefeber 1991">{{Harvnb|Lefeber|Fitzmaurice|Vierdag|1991|p=194–197}}</ref> and the Soviet entry into the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Leffler|1992|p=21}}</ref> This outcome rendered Soviet–American relations a matter of major long-term concern for leaders in both countries.<ref name = "Gaddis">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|1990|p=57}}</ref> | |||

| Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, this phase of the Cold War saw the ]. Between China and the Soviet Union's complicated relations within the Communist sphere, leading to the ], while France, a Western Bloc state, began to demand greater autonomy of action. The ] occurred to suppress the ] of 1968, while the United States experienced internal turmoil from the ] and ]. In the 1960s–1970s, an international ] took root among citizens around the world. Movements against ] and for ] took place, with large ]. By the 1970s, both sides had started making allowances for peace and security, ushering in a period of ] that saw the ] and the ] that opened relations with China as a strategic counterweight to the Soviet Union. A number of self-proclaimed ] governments were formed in the second half of the 1970s in ], including ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ==World War II and post-war (1939–47)== | |||

| {{Main|Origins of the Cold War}} | |||

| ===Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (1939-41)=== | |||

| {{see|Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact| Nazi–Soviet economic relations (1934–1941)}} | |||

| Soviet relations with the West further deteriorated when, one week prior to the start of the ], the Soviet Union and Germany signed the ], which included a secret agreement to split Poland and Eastern Europe between the two states.<ref>Day, Alan J.; East, Roger; Thomas, Richard. ''A Political and Economic Dictionary of Eastern Europe'', pg. 405</ref> Beginning one week later, in September 1939, Germany and the Soviet Union divided Poland and the rest of Eastern Europe through invasions of the countries ceded to each under the Pact.<ref>{{Harvnb|Roberts|2006|p=43-82}}</ref><ref name="ckpipe">Kennedy-Pipe, Caroline, ''Stalin's Cold War'', New York : Manchester University Press, 1995, ISBN 0719042011</ref> | |||

| Détente collapsed at the end of the decade with the beginning of the ] in 1979. Beginning in the 1980s, this phase was another period of elevated tension. The ] led to increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressures on the Soviet Union, which at the time was undergoing the ]. This phase saw the new Soviet leader ] introducing the liberalizing reforms of '']'' ("openness") and '']'' ("reorganization") and ending Soviet involvement in Afghanistan in 1989. Pressures for national sovereignty grew stronger in Eastern Europe, and Gorbachev refused to further support the Communist governments militarily. | |||

| For the next year and a half, they engaged in ], trading vital war materials<ref>{{Harvnb|Ericson|1999|p=1-210}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Shirer|1990|p=598-610}}</ref> until Germany broke the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact with ], the invasion of the Soviet Union through the territories that the two countries had previously divided.<ref name="stalinswars82">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2006|p=82}}</ref> | |||

| The fall of the ] after the ] and the ], which represented a peaceful revolutionary wave with the exception of the ] and the ], overthrew almost all of the Marxist–Leninist regimes of the Eastern Bloc. The ] itself lost control in the country and was banned following the ] that August. This in turn led to the formal ] in December 1991 and the collapse of Communist governments across much of Africa and Asia. The ] became the Soviet Union's successor state, while many of the other republics emerged as fully independent ].<ref name="web.archive.org">{{Cite web |date=23 November 2003 |title=INFCIRC/397 – Note to the Director General from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation |url=http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Infcircs/Others/inf397.shtml |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20031123143520/http://www.iaea.org/Publications/Documents/Infcircs/Others/inf397.shtml |archive-date=2003-11-23 }}</ref> The United States was left as the world's sole superpower. | |||

| ===Allies against the Axis (1941-45)=== | |||

| {{see|Eastern Front (World War II)|Western Front (World War II)|Lend-Lease}} | |||

| During their joint war effort, which began thereafter in 1941, the Soviets suspected that the British and the Americans had conspired to allow the Soviets to bear the brunt of the fighting against Nazi Germany. According to this view, the Western Allies had deliberately delayed opening a second anti-German front in order to step in at the last moment and shape the peace settlement.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|1990|p=151}}</ref> Thus, Soviet perceptions of the West left a strong undercurrent of tension and hostility between the Allied powers.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|1990|p=151–153}}</ref> | |||

| ==Containment, Truman Doctrine, Korean War (1947–1953)== | |||

| ===Wartime conferences regarding post-war Europe=== | |||

| {{Main|Cold War (1947–1948)|Cold War (1948–1953)|Soviet empire|Containment|Truman Doctrine}} | |||

| ]" at the Yalta Conference, ], ] and ]]] | |||

| {{see|Tehran Conference|Yalta Conference}} | |||

| The Allies disagreed about how the European map should look, and how borders would be drawn, following the war.<ref name="Gaddis13-23">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=13–23}}</ref> Each side held dissimilar ideas regarding the establishment and maintenance of post-war security.<ref name="Gaddis13-23" /> The western Allies desired a security system in which democratic governments were established as widely as possible, permitting countries to peacefully resolve differences through ]s.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|1990|p=156}}</ref> | |||

| ===Iron Curtain, Iran, Turkey, Greece, and Poland=== | |||

| Following Russian historical experiences with frequent invasions<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=7}}</ref> and the immense death toll (estimated at 27 million) and destruction the Soviet Union sustained during World War II,<ref>"", BBC News, May 9, 2005. Retrieved on July 2, 2008.</ref> the Soviet Union sought to increase security by controlling the internal affairs of countries that bordered it.<ref name="Gaddis13-23" /><ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|1990|p=176}}</ref> In April 1945, both Churchill and new American President ] opposed, among other things, the Soviets' decision to prop up the ], the Soviet-controlled rival to the ], whose relations with the Soviets were severed.<ref>{{Harvnb|Zubok|1996|p=94}}</ref> | |||

| {{Further|X Article|Iron Curtain|Iran crisis of 1946|Restatement of Policy on Germany}} | |||

| ], 2014]] | |||

| In February 1946, ]'s "]" from Moscow to Washington helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, which would become the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union. The telegram galvanized a policy debate that would eventually shape the ]'s Soviet policy.<ref>{{Cite web|date=22 February 2021|title=This Day in History: George Kennan Sends "Long Telegram"|url=https://www.trumanlibraryinstitute.org/this-day-in-history-2/|access-date=27 October 2021|website=Truman Library Institute}}</ref> Washington's opposition to the Soviets accumulated after broken promises by Stalin and ] concerning Europe and Iran.{{sfn|Hasanli|2014|pp=221–222}} Following the World War II ], the country was occupied by the Red Army in the far north and the British in the south.{{sfn|Sebestyen|2014}} Iran was used by the United States and British to supply the Soviet Union, and the Allies agreed to withdraw from Iran within six months after the cessation of hostilities.{{sfn|Sebestyen|2014}} However, when this deadline came, the Soviets remained in Iran under the guise of the ] and ] ].{{sfn|Kinzer|2003|pp=65–66}} On 5 March, former British prime minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "]" speech calling for an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets, whom he accused of establishing an "iron curtain" dividing Europe.{{sfn|Schmitz|1999}}{{sfn|Harriman|1987–1988}} | |||

| At the ] in February 1945, the Allies failed to reach a firm consensus on the framework for post-war settlement in Europe.<ref name="Gaddis21">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=21}}</ref> Following the ], the Soviets effectively occupied Eastern Europe,<ref name="Gaddis21" /> while strong US and Western allied forces remained in Western Europe. | |||

| A week later, on 13 March, Stalin responded vigorously to the speech, saying Churchill could be compared to ] insofar as he advocated the racial superiority of ] so that they could satisfy their hunger for world domination, and that such a declaration was "a call for war on the USSR." The Soviet leader also dismissed the accusation that the USSR was exerting increasing control over the countries lying in its sphere. He argued that there was nothing surprising in "the fact that the Soviet Union, anxious for its future safety, trying to see to it that governments loyal in their attitude to the Soviet Union should exist in these countries."{{sfn|McCauley|2008|p=143}}<ref>{{Cite web |date=March 1946 |title=Interview to "Pravda" Correspondent Concerning Mr. Winston Churchill's Speech |website=Marxists Internet Archive |url=https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1946/03/x01.htm |access-date=4 April 2017 |url-status=live |archive-date=31 January 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200131200528/https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1946/03/x01.htm}}</ref> | |||

| The Soviet Union, United States, Britain and France established ] and a loose framework for four-power control of occupied Germany.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=22}}</ref> The Allies set up the ] for the maintenance of world peace, but the enforcement capacity of its ] was effectively paralyzed by individual members' ability to use ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Bourantonis|1996|p=130}}</ref> Accordingly, the UN was essentially converted into an inactive forum for exchanging polemical rhetoric, and the Soviets regarded it almost exclusively as a propaganda tribune.<ref>{{Harvnb|Garthoff|1994|p=401}}</ref> | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ===Beginnings of the Eastern Bloc=== | |||

| | border = infobox | |||

| {{see|Eastern Bloc}} | |||

| | image_gap = 20 | |||

| During the final stages of the war, the Soviet Union laid the foundation for the ] by directly annexing several countries as ] that were initially (and effectively) ceded to it by Nazi Germany in the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact. These included eastern ] (incorporated into ]),<ref name="stalinswars43">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2006|p=43}}</ref> ] (which became the ])<ref name="wettig20">{{Harvnb|Wettig|2008|p=21}}</ref>,<ref name="wettig20"/><ref name="senn">Senn, Alfred Erich, ''Lithuania 1940 : revolution from above'', Amsterdam, New York, Rodopi, 2007 ISBN 9789042022256</ref> ] (which became the ]),<ref name="wettig20"/><ref name="senn"/> ] (which became the ]),<ref name="wettig20"/><ref name="senn"/> part of eastern ] (which became the ])<ref name="ckpipe"/> and eastern ] (which became the ]).<ref name="stalinswars55">{{Harvnb|Roberts|2006|p=55}}</ref><ref name="shirer794">{{Harvnb|Shirer|1990|p=794}}</ref> | |||

| | caption_align = center | |||

| |align=right | |||

| |direction=vertical | |||

| |image1=Cold war europe military alliances map en.png | |||

| |width1=200 | |||

| |caption1=European military alliances | |||

| |image2=Cold war europe economic alliances map en.png | |||

| |width2=200 | |||

| |caption2=European economic blocs | |||

| }} | |||

| Soviet territorial demands to Turkey regarding the Dardanelles in the ] and Black Sea ] were also a major factor in increasing tensions.{{sfn|Hasanli|2014|pp=221-222}}{{sfn|Roberts|2011}} In September, the Soviet side produced the ] telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by ]; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war".{{sfn|Kydd|2018|p=107}} On 6 September 1946, ] delivered a ] in Germany repudiating the ] (a proposal to partition and de-industrialize post-war Germany) and warning the Soviets that the US intended to maintain a military presence in Europe indefinitely.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=30}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Secretary of State James Byrnes. Restatement of Policy on Germany. September 6, 1946 |url=https://usa.usembassy.de/etexts/ga4-460906.htm |website=usa.usembassy.de |access-date=5 November 2022}}</ref> As Byrnes stated a month later, "The nub of our program was to win the German people ... it was a battle between us and Russia over minds ..." In December, the Soviets agreed to withdraw from Iran after persistent US pressure, an early success of containment policy. | |||

| By 1947, US president ] was outraged by the perceived resistance of the Soviet Union to American demands in Iran, Turkey, and Greece, as well as Soviet rejection of the ] on nuclear weapons.{{sfn|Milestones: 1945–1952}} In February 1947, the British government announced that it could no longer afford to finance the ] in ] against Communist-led insurgents.{{sfn|Iatrides|1996|pp=373–376}} In the same month, Stalin conducted the rigged ] which constituted an open breach of the ]. The ] responded by adopting a policy of ],{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|pp=28–29}} with the goal of stopping the spread of ]. Truman delivered a speech calling for the allocation of $400 million to intervene in the war and unveiled the ], which framed the conflict as a contest between free peoples and ] regimes.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|pp=28–29}} American policymakers accused the Soviet Union of conspiring against the Greek royalists in an effort to ] even though Stalin had told the Communist Party to cooperate with the British-backed government.{{sfn|Gerolymatos|2017|pp=195–204}}{{sfn|LaFeber|1993|pp=194–197}}{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=38}} | |||

| British Prime Minister ] was concerned that, given the enormous size of Soviet forces deployed in Europe at the end of the war, and the perception that Soviet leader ] was unreliable, there existed a Soviet threat to Western Europe.<ref name="Telegraph">Fenton, Ben. "", telegraph.co.uk, October 1, 1998. Retrieved on July 23, 2008.</ref> | |||

| In April-May 1945, the ]'s Joint Planning Staff Committee developed ], a plan "to impose upon Russia the will of the United States and the British Empire".<ref>{{cite web | last = British War Cabinet, Joint Planning Staff, Public Record Office, CAB 120/691/109040 / 002 | date = 1945-08-11 | url = http://www.history.neu.edu/PRO2/ | title = "Operation Unthinkable: 'Russia: Threat to Western Civilization'" | format = online photocopy | publisher = Department of History, Northeastern University | accessdate = 2008-06-28}}</ref> The plan, however, was rejected by the British ] as militarily unfeasible.<ref name="Telegraph" /> | |||

| Enunciation of the Truman Doctrine marked the beginning of a US bipartisan defense and foreign policy consensus between ] and ] focused on containment and ] that weakened during and after the ], but ultimately persisted thereafter.{{sfn|Paterson|1989|pp=35, 142, 212}} Moderate and conservative parties in Europe, as well as social democrats, gave virtually unconditional support to the Western alliance,{{sfn|Moschonas|2002|p=21}} while ] and ], financed by the ] and involved in its intelligence operations,{{sfn|Andrew|Mitrokhin|2000|p=276}} adhered to Moscow's line, although dissent began to appear after 1956. Other critiques of the consensus policy came from ], the ], and the ].{{sfn|Crocker|Hampson|Aall|2007|p=55}} | |||

| ===Potsdam Conference and defeat of Japan=== | |||

| ], ] and ] at the ].]] | |||

| {{see|Potsdam Conference|Surrender of Japan}} | |||

| At the ], which started in late July after Germany's surrender, serious differences emerged over the future development of Germany and eastern Europe.<ref name = "Byrd">{{cite encyclopedia|author=Byrd, Peter|editor=McLean, Iain; McMillan, Alistair|encyclopedia=The concise Oxford dictionary of politics|title=Cold War (entire chapter)|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xLbEHQAACAAJ&ei=E45VSJrQO4e4jgGh_oWODA|accessdate=2008-06-16|year=2003|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0192802763}}</ref> Moreover, the participants' mounting antipathy and bellicose language served to confirm their suspicions about each others' hostile intentions and entrench their positions.<ref>Alan Wood, p. 62</ref> At this conference Truman informed Stalin that the United States possessed a powerful new weapon.<ref name="Gaddis25" /> | |||

| ===Marshall Plan, Czechoslovak coup and formation of two German states=== | |||

| Stalin was aware that the Americans were working on the atomic bomb and, given that the Soviets' own rival program was in place, he reacted to the news calmly. The Soviet leader said he was pleased by the news and expressed the hope that the weapon would be used against Japan.<ref name="Gaddis25">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=25–26}}</ref> One week after the end of the Potsdam Conference, the US ]. Shortly after the attacks, Stalin protested to US officials when Truman offered the Soviets little real influence in ].<ref>{{Harvnb|LaFeber|2002|p=28}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Marshall Plan|Western Bloc|1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état}} | |||

| ] economic ] to Western Europe.]] | |||

| ] showing countries that received Marshall Plan aid. The red columns show the relative amount of total aid received per nation.]] | |||

| ] under Marshall Plan aid]] | |||

| In early 1947, France, Britain and the United States unsuccessfully attempted to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union for a plan envisioning an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, goods and infrastructure already taken by the Soviets.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=16}} In June 1947, in accordance with the ], the United States enacted the ], a pledge of economic assistance for all European countries willing to participate.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=16}} Under the plan, which President Harry S. Truman signed on 3 April 1948, the US government gave to Western European countries over $13 billion (equivalent to $189 billion in 2016). Later, the program led to the creation of the ]. | |||

| ==Early blows in the political Cold War== | |||

| The plan's aim was to rebuild the democratic and economic systems of Europe and to counter perceived threats to the ], such as communist parties seizing control.{{sfn|Gaddis|1990|p=186}} The plan also stated that European prosperity was contingent upon German economic recovery.{{sfn|Dinan|2017|p=40}} One month later, Truman signed the ], creating a unified ], the ] (CIA), and the ] (NSC). These would become the main bureaucracies for US defense policy in the Cold War.{{sfn|Karabell|1999|p=916}} | |||

| ===Intelligence=== | |||

| ] | |||

| At no time during this period and throughout World War II did the Western Allies consider sharing with the Soviet Union their decisive strategic advantage over the enemy, namely the copious and vitally important military intelligence obtained from the ultra-secret interception and decoding of German military signals at every level of command. This operation, one of the most closely guarded secrets of World War II and code-named Ultra, provided the Western Allies with constant and reliable information about the strength, disposition and intentions of the enemy at any given time. <ref>FW Winterbotham, ''The Ultra Secret'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1974; FH Hinsley, ''British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its influence on Strategy and Operations'', (4 Vols), London: HMSO, 1977-1988 (official history); Ralph Bennett, ''Ultra in the West'', London: Hutchinson 1979. </ref> Armed with this vital intelligence, Western military commanders at pivotal moments of the war in Europe made a series of seemingly inexplicable command decisions, the end results of which served to prolong the fighting in Europe while depriving the Red Army of relief on the Russian-German front where the Soviet Union continued to carry the brunt of the war against Hitler.<ref> Ralph Bennett, "Ultra and Some Command decisions", ''Journal of Contemporary History'', Vol 16, 1981, pp.145-6; Ralph Bennett, ''Ultra and Mediterranean Strategy 1941-1945'', London: Bodley Head 1981</ref> Even before the war with Germany was officially over, secret arrangements were concluded between American military intelligence and former key figures in the anti-communist section of German military intelligence or ''Abwher'', headed by Major General Reinhard Gehlen. In return for immunity from prosecution for war crimes, Gehlen and other senior Nazi intelligence officers agreed to serve the West as faithfully as they had served Hitler. With the help of copious German anti-communist intelligence files preserved intact by him, Gehlen commenced to advise the Americans on how to go about establishing their own anti-Soviet networks in Europe. <ref>Christopher Simpson, ''Blowback: America's Recruitment of Nazis and Its Effects on the Cold War'', London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson 1988, pp.42, 44; Danil Kraminov, ''The Spring of 1945: Notes of a Soviet War Correspondent'', Moscow: Novosti 1985, pp.99-102; Richard Harris Smith, ''OSS'', Berkeley: University of California Press 1972, p.240; EH Cookridge, ''Gehlen'', London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1971.</ref> | |||

| Stalin believed economic integration with the West would allow ] countries to escape Soviet control, and that the US was trying to buy a pro-US re-alignment of Europe.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=32}} Stalin therefore prevented Eastern Bloc nations from receiving Marshall Plan aid.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=32}} The Soviet Union's alternative to the Marshall Plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with central and eastern Europe, became known as the ] (later institutionalized in January 1949 as the ]).{{sfn|LaFeber|1993|pp=194–197}} Stalin was also fearful of a reconstituted Germany; his vision of a post-war Germany did not include the ability to rearm or pose any kind of threat to the Soviet Union.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|pp=105–106}} | |||

| ===World War III aborted=== | |||

| In mid-1945 immediately after Germany's defeat, when Stalin warned his advisers on May 16 that Churchill had preserved former German enemy forces in the British Zone of Occupation in Berlin "in full combat readiness and (was) co-operating with them.” <ref>Marlis G Steinert, "The Allied Decision to Arrest the Dönitz Government", ''Historical Journal'', Vol 31 No 3, 1988, p. 658-60. </ref> Churchill envisioned a future role for the former German soldiers in augmenting Montgomery's Anglo-American 21st Army Group in the event of hostilities with the Soviet Union. Montgomery was instructed to be careful in stacking confiscated German arms so that they could be re-issued swiftly to the same former enemy soldiers from whom they had been confiscated. <ref>Steinert, op cit, p.272, and confer ]). </ref> Churchill instructed the head of the British Army, Field Marshal Viscount Alanbrooke, to investigate the possibility of fighting Russia before British and American forces were demobilised in Europe. Alanbrooke concluded that war against the Soviet Union was not feasible.<ref>David Fraser, ''Alanbrooke'', London: Collins, 1982, p.489.</ref> Despite its heavy losses in defeating Germany on the Eastern front, the Red Army was now the world's greatest land power. It was stronger in men and conventional weapons than the combined forces of the US, Great Britain, Canada and France. The Red Army had 17 divisions deployed in the Soviet zone of occupation in Berlin alone, whereas the US Army had by then been severely weakened by demobilisation and redeployment, and the British and French forces were preparing respectively to engage in policing actions and counter-insurgency operations against their former communist allies in the colonial territories of the Far East. <ref> Larionov, Yeronin, Solovyov, Timokhovich, op cit, p.452 </ref> | |||

| In early 1948, Czech Communists executed a ] in ] (resulting in the formation of the ]), the only Eastern Bloc state that the Soviets had permitted to retain democratic structures.{{sfn|Wettig|2008|p=86}} The public brutality of the coup shocked Western powers more than any event up to that point and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=19}}{{sfn|Grenville|2005|pp=370–371}} | |||

| ==Tensions build== | |||

| {{see|Long Telegram|Iron Curtain|Restatement of Policy on Germany}} | |||

| In February 1946, ]'s "]" from Moscow helped to articulate the US government's increasingly hard line against the Soviets, and became the basis for US strategy toward the Soviet Union for the duration of the Cold War.<ref>{{Harvnb|Kennan|1968|p=292–295}}</ref> That September, the Soviet side produced the ] telegram, sent by the Soviet ambassador to the US but commissioned and "co-authored" by ]; it portrayed the US as being in the grip of monopoly capitalists who were building up military capability "to prepare the conditions for winning world supremacy in a new war".<ref>{{Harvnb|Kydd|2005|p=107}}</ref> | |||

| In an immediate aftermath of the crisis, the ] was held, resulting in the ] boycott of the Allied Control Council and its incapacitation, an event marking the beginning of the full-blown Cold War, as well as ending any hopes at the time for a single German government and leading to formation in 1949 of the ] and ].{{sfn|Wettig|2008|pp=96–100}} | |||

| On September 6, 1946, ] delivered a ] in Germany repudiating the ] (a proposal to partition and de-industrialize post-war Germany) and warning the Soviets that the US intended to maintain a military presence in Europe indefinitely.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=30}}</ref> As Byrnes admitted a month later, "The nub of our program was to win the German people it was a battle between us and Russia over minds "<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.daz.org/enJamesFByrnes.html|title=Southern Partnership: James F. Byrnes, Lucius D. Clay and Germany, 1945-1947|first=Curtis F.|last=Morgan|accessdate=2008-06-09|publisher=James F. Byrnes Institute}}</ref> | |||

| The twin policies of the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan led to billions in economic and military aid for Western Europe, Greece, and Turkey. With the US assistance, the Greek military ].{{sfn|Karabell|1999|p=916}} Under the leadership of ] the Italian ] defeated the powerful ]–] alliance in the ].{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=162}} | |||

| A few weeks after the release of this "Long Telegram", former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill delivered his famous "]" speech in ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=94}}</ref> The speech called for an Anglo-American alliance against the Soviets, whom he accused of establishing an "iron curtain" from "] in the Baltic to ] in the Adriatic".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.winstonchurchill.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=711|title=Churchill and...Politics: The True Meaning of the Iron Curtain Speech|author=Harriman, Pamela C.|accessdate=2008-06-22|publisher=Winston Churchill Centre|date=Winter 1987–1988}}</ref><ref name = "Schmitz">{{cite encyclopedia|author=Schmitz, David F.|editor=Whiteclay Chambers, John|encyclopedia=The Oxford Companion to American Military History|title=Cold War (1945–91): Causes |url=http://books.google.com/books?id=xtMKHgAACAAJ&dq=The+Oxford+Companion+to+American+Military+History|accessdate=2008-06-16|year=1999|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=0195071980}}</ref> | |||

| Outside of Europe, the United States also began to express interest in the development of many other countries, so that they would not fall under the sway of Eastern Bloc communism. In his January 1949 inaugural address, Truman declared for the first time in U.S. history that ] would be a key part of U.S. foreign policy. The resulting program later became known as the ] because it was the fourth point raised in his address.<ref name="Hamilton_Page_57">{{cite book |last1=Hamilton |first1=Shane |title=Supermarket USA: Food and Power in the Cold War Farms Race |date=2018 |publisher=Yale University Press |location=New Haven |isbn=9780300232691 |page=57 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=lepqDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA57#v=onepage&q&f=false}}</ref> | |||

| ==Containment through the Korean War (1947–53)== | |||

| {{Main|Cold War (1947–1953)}} | |||

| ===Soviet satellite states=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{see|Eastern Bloc|Cominform}} | |||

| After annexing several occupied countries as ] at the end of World War II, other occupied states were added to the ] by converting them into puppet ] states,<ref name = "Schmitz" /> such as ],<ref name="wettig96">{{Harvnb|Wettig|2008|p=96-100}}</ref> the ], the ],<ref name="granville">Granville, Johanna, ''The First Domino: International Decision Making during the Hungarian Crisis of 1956'', Texas A&M University Press, 2004. ISBN 1-58544-298-4</ref> the ],<ref>{{Harvnb|Grenville|2005|p=370-71}}</ref> the ] and the ].<ref name="cook17">{{Harvnb|Cook|2001|p=17}}</ref> | |||

| ===Espionage=== | |||

| The Soviet-style regimes that arose in the Bloc not only reproduced Soviet ], but also adopted the brutal methods employed by ] and Soviet secret police to suppress real and potential opposition.<ref name="roht83">{{Harvnb|Roht-Arriaza|1995|p=83}}</ref> In Asia, the Red Army had overrun ] in the last month of the war, and went on to occupy the large swath of Korean territory located north of the 38th parallel.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=40}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Cold War espionage|American espionage in the Soviet Union and Russian Federation|Soviet espionage in the United States}} | |||

| All major powers engaged in espionage, using a great variety of spies, ]s, ], and new technologies such as the tapping of telephone cables.{{sfn|Garthoff|2004}} The Soviet ] ("Committee for State Security"), the bureau responsible for foreign espionage and internal surveillance, was famous for its effectiveness. The most famous Soviet operation involved its ] that delivered crucial information from the United States' ], leading the USSR to detonate its first nuclear weapon in 1949, four years after the American detonation and much sooner than expected.{{sfn|Andrew|Mitrokhin|1999|p={{pn|date=August 2024}}}}<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.history.com/news/atomic-bomb-soviet-spies|title=8 Spies Who Leaked Atomic Bomb Intelligence to the Soviets|date=21 July 2023 |website=HISTORY}}</ref> A massive network of informants throughout the Soviet Union was used to monitor dissent from official Soviet politics and morals.{{sfn|Garthoff|2004}}{{sfn|Hopkins|2007}} Although to an extent ] had always existed, the term itself was invented, and the strategy formalized by a ] department of the Soviet KGB.{{sfn|Taylor|2016}}{{efn-ua|{{harvnb|Jowett|O'Donnell|2005|pp=21–23}}: "In fact, the word disinformation is a cognate for the Russian dezinformatsia, taken from the name of a division of the KGB devoted to black propaganda."}} | |||

| In September 1947, the Soviets created ], the purpose of which was to enforce orthodoxy within the international communist movement and tighten political control over Soviet ] through coordination of communist parties in the ].<ref name="Gaddis32" /> Cominform faced an embarrassing setback the following June, when the ] obliged its members to expel Yugoslavia, which remained Communist but adopted a ] position.<ref>{{Harvnb|Carabott|Sfikas|2004|p=66}}</ref> | |||

| Based on the amount of top-secret Cold War archival information that has been released, historian ] concludes there probably was parity in the quantity and quality of secret information obtained by each side. However, the Soviets probably had an advantage in terms of ] (human intelligence or interpersonal espionage) and "sometimes in its reach into high policy circles." In terms of decisive impact, however, he concludes:{{sfn|Garthoff|2004|pp=29–30}} | |||

| As part of the Soviet domination of the Eastern Bloc, the ], led by ], supervised the establishment of Soviet-style secret police systems in the Bloc that were supposed to crush anti-communist resistance.<ref name="Gaddis 2005, p. 34"/> When the slightest stirrings of independence emerged in the Bloc, Stalin's strategy matched that of dealing with domestic pre-war rivals: they were removed from power, put on trial, imprisoned, and in several instances, executed.<ref name="Gaddis 2005, p. 100">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=100}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>We also can now have high confidence in the judgment that there were no successful "moles" at the political decision-making level on either side. Similarly, there is no evidence, on either side, of any major political or military decision that was prematurely discovered through espionage and thwarted by the other side. There also is no evidence of any major political or military decision that was crucially influenced (much less generated) by an agent of the other side.</blockquote> | |||

| According to historian Robert L. Benson, "Washington's forte was ] - the procurement and analysis of coded foreign messages." leading to the ] or Venona intercepts, which monitored the communications of Soviet intelligence agents.{{sfn|Benson|Warner|1996|pp=vii, xix}} ] wrote that the Venona project contained "overwhelming proof of the activities of Soviet spy networks in America, complete with names, dates, places, and deeds."{{sfn|Moynihan|1998|pp=15–16}} The Venona project was kept highly secret even from policymakers until the ] in 1995.{{sfn|Moynihan|1998|pp=15–16}} Despite this, the decryption project had already been betrayed and dispatched to the USSR by ] and ] in 1946,{{sfn|Moynihan|1998|pp=15–16}}{{sfn|West|2002}} as was discovered by the US by 1950.{{sfn|Benson|Warner|1996|pp=xxvii, xxviii}} Nonetheless, the Soviets had to keep their discovery of the program secret, too, and continued leaking their own information, some of which was still useful to the American program.{{sfn|West|2002}} According to Moynihan, even President Truman may not have been fully informed of Venona, which may have left him unaware of the extent of Soviet espionage.{{sfn|Moynihan|1998|p=70}}<ref name="trumanfas">{{Cite web |title=Did Truman Know about Venona?|url=https://fas.org/irp/eprint/truman-venona.html|access-date=12 June 2021|website=fas.org}}</ref> | |||

| Clandestine ] from the Soviet Union, who infiltrated the ] during WWII, played a major role in increasing tensions that led to the Cold War.{{sfn|Benson|Warner|1996|pp=vii, xix}} | |||

| ===Containment and the Truman Doctrine=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Containment|Truman Doctrine}} | |||

| By 1947, US president Harry S. Truman's advisers urged him to take immediate steps to counter the Soviet Union's influence, citing Stalin's efforts (amid post-war confusion and collapse) to undermine the US by encouraging rivalries among capitalists that could precipitate another war.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=27}}</ref> In February 1947, the British government announced that it could no longer afford to finance the Greek monarchical military regime in ] against communist-led insurgents. | |||

| In addition to usual espionage, the Western agencies paid special attention to debriefing ].{{sfn|Cowley|1996|p=157}} ] describes that the CIA understood that the KGB used "provocations", or fake defections, as a trick to embarrass Western intelligence and establish Soviet double agents. As a result, from 1959 to 1973, the CIA required that East Bloc defectors went through a counterintelligence investigation before being recruited as a source of intelligence.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Epstein|first=Edward Jay|title=Secrets of the Teheren Archive |url=https://www.edwardjayepstein.com/archived/teheren.htm |access-date=13 November 2021 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010217081540/http://www.edwardjayepstein.com:80/archived/teheren.htm |archive-date=17 February 2001 |website=www.edwardjayepstein.com}}</ref> | |||

| The American government's response to this announcement was the adoption of ],<ref name="Gaddis28">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=28–29}}</ref> the goal of which was to stop the spread of communism. Truman delivered a speech that called for the allocation of $400 million to intervene in the war and unveiled the ], which framed the conflict as a contest between free peoples and totalitarian regimes.<ref name="Gaddis28" /> Even though the insurgents were helped by ]'s ],<ref name ="Lefeber 1991" /> US policymakers accused the Soviet Union of conspiring against the Greek royalists in an effort to ] Soviet influence.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=38}}</ref> | |||

| During the late 1970s and 1980s, the KGB perfected its use of espionage to sway and distort diplomacy.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Epstein|first=Edward Jay|title=Secrets of the Teheren Archive (page 2)|website=edwardjayepstein.com |url=https://www.edwardjayepstein.com/archived/teheren2.htm |url-status=live|access-date=13 November 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010223043813/http://www.edwardjayepstein.com:80/archived/teheren2.htm |archive-date=23 February 2001}}</ref> ] were "clandestine operations designed to further Soviet foreign policy goals," consisting of disinformation, forgeries, leaks to foreign media, and the channeling of aid to militant groups.<ref>{{Cite web|title=KGB Active Measures – Russia / Soviet Intelligence Agencies |url=https://irp.fas.org/world/russia/kgb/su0523.htm|access-date=13 November 2021|website=irp.fas.org}}</ref> Retired KGB Major General ] described active measures as "the heart and soul of ]."<ref>{{cite web |title=Inside the KGB: An interview with retired KGB Maj. Gen. Oleg Kalugin |publisher=] |url=http://www3.cnn.com/SPECIALS/cold.war/episodes/21/interviews/kalugin/ |archive-date=27 June 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070627183623/http://www3.cnn.com/SPECIALS/cold.war/episodes/21/interviews/kalugin/}}</ref> | |||

| Enunciation of the Truman Doctrine marked the beginning of a US bipartisan defense and foreign policy consensus between ] and ] focused on containment and deterrence that weakened during and after the ], but ultimately held steady.<ref>{{Harvnb|Hahn|1993|p=6}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Higgs|2006|p=137}}</ref> Moderate and conservative parties in Europe, as well as social democrats, gave virtually unconditional support to the Western alliance,<ref>{{Harvnb|Moschonas|Elliott|2002|p=21}}</ref> while European and American Communists, paid by the ] and involved in its intelligence operations,<ref>{{cite book| last=Andrew| first =Christopher| coauthors=Mitrokhin, Vasili| title= The Sword and the Shield: The Mitrokhin Archive and the Secret History of the KGB|publisher= Basic Books| date =2000|pages =276}}</ref> adhered to Moscow's line, although dissent began to appear after 1956. Other critiques of consensus politics came from ], the ] and the ] movement.<ref>{{Harvnb|Crocker|Hampson|Aall|2007|p=55}}</ref> | |||

| During the ], "spy wars" also occurred between the USSR and PRC.<ref>{{Cite web|type=blog |last=Kovacevic |first=Filip |date=April 22, 2021 |title=The Soviet-Chinese Spy Wars in the 1970s: What KGB Counterintelligence Knew, Part II |website=Wilson Center |url=https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/soviet-chinese-spy-wars-1970s-what-kgb-counterintelligence-knew-part-ii|access-date=13 November 2021 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| ===Marshall Plan and Czechoslovak coup d'état=== | |||

| ] aid. The red columns show the relative amount of total aid per nation.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{main|Marshall Plan|Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948}} | |||

| In early 1947, Britain, France and the United States unsuccessfully attempted to reach an agreement with the Soviet Union for a plan envisioning an economically self-sufficient Germany, including a detailed accounting of the industrial plants, goods and infrastructure already removed by the Soviets.<ref name="miller16">{{Harvnb|Miller|2000|p=16}}</ref> In June 1947, in accordance with the ], the United States enacted the ], a pledge of economic assistance for all European countries willing to participate, including the Soviet Union.<ref name="miller16"/> | |||

| ===Cominform and the Tito–Stalin Split=== | |||

| The plan's aim was to rebuild the democratic and economic systems of Europe and to counter perceived threats to Europe's balance of power, such as communist parties seizing control through revolutions or elections.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|1990|p=186}}</ref> The plan also stated that European prosperity was contingent upon German economic recovery.<ref>{{cite news|url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,887417,00.html|title=Pas de Pagaille!|work=]|date=July 28, 1947|accessdate=2008-05-28}}</ref> One month later, Truman signed the ], creating a unified ], the ] (CIA), and the ]. These would become the main bureaucracies for US policy in the Cold War.<ref name= "Karabell" >{{Harvnb|Karabell|1999|p=916}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Cominform|Tito–Stalin Split}} | |||

| In September 1947, the Soviets created ] to impose orthodoxy within the international communist movement and tighten political control over Soviet ] through coordination of communist parties in the ].{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=32}} Cominform faced an embarrassing setback the following June, when the ] obliged its members to expel Yugoslavia, which remained communist but adopted a ] position and began accepting financial aid from the US.{{sfn|Papathanasiou|2017|p=66}} | |||

| Stalin believed that economic integration with the West would allow ] countries to escape Soviet control, and that the US was trying to buy a pro-US re-alignment of Europe.<ref name="Gaddis32">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=32}}</ref> Stalin therefore prevented Eastern Bloc nations from receiving Marshall Plan aid.<ref name="Gaddis32" /> The Soviet Union's alternative to the Marshall plan, which was purported to involve Soviet subsidies and trade with eastern Europe, became known as the ] (later institutionalized in January 1949 as the ]).<ref name = "Lefeber 1991" /> Stalin was also fearful of a reconstituted Germany; his vision of a post-war Germany did not include the ability to rearm or pose any kind of threat to the Soviet Union.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=105–106}}</ref> | |||

| Besides Berlin, the status of the city of ] was at issue. Until the break between Tito and Stalin, the Western powers and the Eastern bloc faced each other uncompromisingly. In addition to capitalism and communism, Italians and Slovenes, monarchists and republicans as well as war winners and losers often faced each other irreconcilably. The neutral buffer state ], founded in 1947 with the United Nations, was split up and dissolved in 1954 and 1975, also because of the détente between the West and Tito.{{sfn|Jennings|2017|p=244}}{{sfn|Ruzicic-Kessler|2014}} | |||

| In early 1948, following reports of strengthening "reactionary elements", Soviet operatives executed a ] in ], the only Eastern Bloc state that the Soviets had permitted to retain democratic structures.<ref name="wettig86">{{Harvnb|Wettig|2008|p=86}}</ref><ref>{{Harvnb|Patterson|1997|p=132}}</ref> The public brutality of the coup shocked Western powers more than any event up to that point, set in a motion a brief scare that war would occur and swept away the last vestiges of opposition to the Marshall Plan in the United States Congress.<ref name="miller19">{{Harvnb|Miller|2000|p=19}}</ref> | |||

| ===Berlin Blockade=== | |||

| The twin policies of the Truman Doctrine and the Marshall Plan led to billions in economic and military aid for Western Europe, and Greece and Turkey. With US assistance, the Greek military won its civil war,<ref name = "Karabell" /> The Italian ] defeated the powerful ]-] alliance in the ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=162}}</ref> Increases occurred in intelligence and espionage activities, ] and diplomatic expulsions.<ref>{{Harvnb|Cowley|1996|p=157}}</ref> | |||

| {{Main|Berlin Blockade}} | |||

| ] during the Berlin Blockade]] | |||

| The US and Britain merged their western German occupation zones into "]" (1 January 1947, later "Trizone" with the addition of France's zone, April 1949).{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=13}} As part of the economic rebuilding of Germany, in early 1948, representatives of a number of Western European governments and the United States announced an agreement for a merger of western German areas into a federal governmental system.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=18}} In addition, in accordance with the ], they began to re-industrialize and rebuild the West German economy, including the introduction of a new ] currency to replace the old ] currency that the Soviets had debased.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=31}} The US had secretly decided that a unified and neutral Germany was undesirable, with ] telling General Eisenhower "in spite of our announced position, we really do not want nor intend to accept German unification on any terms that the Russians might agree to, even though they seem to meet most of our requirements."{{sfn|Layne|2007|p=67}} | |||

| ===Berlin Blockade and airlift=== | |||

| ] in Berlin during the Berlin Blockade.]] | |||

| {{main|Berlin Blockade}} | |||

| The United States and Britain merged their western German occupation zones into ] (later "trizonia" with the addition of France's zone).<ref name="miller13">{{Harvnb|Miller|2000|p=13}}</ref> As part of the economic rebuilding of Germany, in early 1948, representatives of a number of Western European governments and the United States announced an agreement for a merger of western German areas into a federal governmental system.<ref name="miller18">{{Harvnb|Miller|2000|p=18}}</ref> In addition, in accordance with the ], they began to re-industrialize and rebuild the German economy, including the introduction of a new ] currency to replace the old ] currency that the Soviets had debased.<ref name="miller31">{{Harvnb|Miller|2000|p=31}}</ref> | |||

| Shortly thereafter, Stalin instituted the |

Shortly thereafter, Stalin instituted the Berlin Blockade (June 1948 – May 1949), one of the first major crises of the Cold War, preventing Western supplies from reaching West Germany's exclave of ].{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=33}} The United States (primarily), Britain, France, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and several other countries began the massive "Berlin airlift", supplying West Berlin with provisions despite Soviet threats.{{sfn|Miller|2000|pp=65–70}} | ||

| The Soviets mounted a public relations campaign against the policy change, communists attempted to disrupt the elections |

The Soviets mounted a public relations campaign against the policy change. Once again, the East Berlin communists attempted to disrupt the ],{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=13}} which were held on 5 December 1948 and produced a turnout of 86% and an overwhelming victory for the non-communist parties.{{sfn|Turner|1987|p=29}} The results effectively divided the city into East and West, the latter comprising US, British and French sectors. 300,000 Berliners demonstrated and urged the international airlift to continue,{{sfn|Fritsch-Bournazel|1990|p=143}} and US Air Force pilot ] created "]", which supplied candy to German children.{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=26}} The Airlift was as much a logistical as a political and psychological success for the West; it firmly linked West Berlin to the United States.{{sfn|Daum|2008|pp=11–13, 41}} In May 1949, Stalin lifted the blockade.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=34}}{{sfn|Miller|2000|pp=180–181}} | ||

| In 1952, Stalin repeatedly ] to unify East and West Germany under a single government chosen in elections supervised by the United Nations, if the new Germany were to stay out of Western military alliances, but this proposal was turned down by the Western powers. Some sources dispute the sincerity of the proposal.{{sfn|van Dijk|1996}} | |||

| ===NATO beginnings and Radio Free Europe=== | |||

| {{main|NATO|Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty|Eastern Bloc information dissemination}} | |||

| ] with guests in the Oval Office.]] | |||

| Britain, France, the United States, Canada and eight other western European countries signed the ] of April 1949, establishing the ] (NATO).<ref name="Gaddis 2005, p. 34"/> That August, Stalin ordered the detonation of the first Soviet atomic device.<ref name = "Lefeber 1991" /> Following Soviet refusals to participate in a German rebuilding effort set forth by western European countries in 1948,<ref name="miller18"/><ref name="turner23">{{Harvnb|Turner|1987|p=23}}</ref> the US, Britain and France spearheaded the establishment of West Germany from the ] in May 1949.<ref name = "Byrd" /> The Soviet Union proclaimed its zone of occupation in Germany the ] that October.<ref name = "Byrd" /> | |||

| ===Beginnings of NATO and Radio Free Europe=== | |||

| Media in the ] was an ], with radio and television organizations being state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local communist party.<ref name="oneil15">{{cite book|last=O'Neil|first=Patrick|title=Post-communism and the Media in Eastern Europe|publisher=Routledge|year=1997|isbn=0714647659|p=15-25}}</ref> Soviet propaganda used Marxist philosophy to attack capitalism, claiming labor exploitation and war-mongering imperialism were inherent in the system.<ref>James Wood, p. 111</ref> | |||

| {{Main|NATO|Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty|Eastern Bloc media and propaganda|Propaganda in the Soviet Union}} | |||

| ] with guests in the Oval Office.]] | |||

| Britain, France, the United States, Canada and eight other western European countries signed the ] of April 1949, establishing the ] (NATO).{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=34}} That August, the ] was detonated in ], ].{{sfn|LaFeber|1993|pp=194–197}} Following Soviet refusals to participate in a German rebuilding effort set forth by western European countries in 1948,{{sfn|Miller|2000|p=18}}{{sfn|Turner|1987|p=23}} the US, Britain and France spearheaded the establishment of the ] from the ] in April 1949.{{sfn|Bungert|1994}} The Soviet Union proclaimed ] in Germany the ] that October.{{sfn|Byrd|2003}} | |||

| Along with the broadcasts of the ] and the ] to Eastern Europe,<ref>{{Harvnb|Puddington|2003|p=131}}</ref> a major propaganda effort begun in 1949 was ], dedicated to bringing about the peaceful demise of the ] system in the Eastern Bloc.<ref name="Puddington9" /> Radio Free Europe attempted to achieve these goals by serving as a surrogate home radio station, an alternative to the controlled and party-dominated domestic press.<ref name="Puddington9">{{Harvnb|Puddington|2003|p=9}}</ref> Radio Free Europe was a product of some of the most prominent architects of America's early Cold War strategy, especially those who believed that the Cold War would eventually be fought by political rather than military means, such as George F. Kennan.<ref name="Puddington7">{{Harvnb|Puddington|2003|p=7}}</ref> | |||

| Media in the ] was an ], completely reliant on and subservient to the communist party. Radio and television organizations were state-owned, while print media was usually owned by political organizations, mostly by the local communist party.{{sfn|O'Neil|1997|pp=15–25}} Soviet radio broadcasts used Marxist rhetoric to attack capitalism, emphasizing themes of labor exploitation, imperialism and war-mongering.{{sfn|Wood|1992|p=105}} | |||

| American policymakers, including Kennan and ], acknowledged that the Cold War was in its essence a war of ideas.<ref name=Puddington7 /> The United States, acting through the CIA, funded a long list of projects to counter the Communist appeal among intellectuals in Europe and the developing world.<ref>{{Harvnb|Puddington|2003|p=10}}</ref> | |||

| Along with the broadcasts of the ] and the ] to Central and Eastern Europe,{{sfn|Puddington|2003|p=131}} a major propaganda effort began in 1949 was ], dedicated to bringing about the peaceful demise of the communist system in the Eastern Bloc.{{sfn|Puddington|2003|p=9}} Radio Free Europe attempted to achieve these goals by serving as a surrogate home radio station, an alternative to the controlled and party-dominated domestic press in the Soviet Bloc.{{sfn|Puddington|2003|p=9}} Radio Free Europe was a product of some of the most prominent architects of America's early Cold War strategy, especially those who believed that the Cold War would eventually be fought by political rather than military means, such as George F. Kennan.{{sfn|Puddington|2003|p=7}} Soviet and Eastern Bloc authorities used various methods to suppress Western broadcasts, including ].<ref>{{cite report |url=https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=pst.000013679477;view=1up;seq=414 |chapter=Exhibit No. 1 – Voice of America and Liberty: Strange Policies |title=Hearings on Federal Government's Handling of Soviet and Communist Bloc Defectors before the United States Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Governmental Affairs, United States Senate, One Hundredth Congress, first session, October 8, 9, 21, 1987 |place=Washington, D.C. |date=1988 |page=406}}</ref>{{sfn|Bamford|2003}} | |||

| In the early 1950s, the US worked for the rearmament of West Germany and, in 1955, secured its full membership of NATO.<ref name = "Byrd" /> In May 1953, Beria, by then in a government post, had made an unsuccessful proposal to allow the reunification of a neutral Germany to prevent West Germany's incorporation into NATO.<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=105}}</ref> | |||

| American policymakers, including Kennan and ], acknowledged that the Cold War was in its essence a war of ideas.{{sfn|Puddington|2003|p=7}} The United States, acting through the CIA, funded a long list of projects to counter the communist appeal among intellectuals in Europe and the developing world.{{sfn|Puddington|2003|p=10}} The CIA also ] sponsored a domestic propaganda campaign called ].{{sfn|Cummings|2010}} | |||

| ===Chinese Civil War and SEATO=== | |||

| {{see|Chinese Civil War|Southeast Asia Treaty Organization}} | |||

| In 1949, ] People's Liberation Army defeated ] US-backed ] (KMT) Nationalist Government in China, and the Soviet Union promptly created an alliance with the newly-formed ].<ref>{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=39}}</ref> The Nationalist Government retreated to the island of ]. Confronted with the Communist takeover of mainland China and the end of the US atomic monopoly in 1949, the Truman administration quickly moved to escalate and expand the ] policy.<ref name = "Lefeber 1991" /> In ], a secret 1950 document,<ref name="Gaddis 2005, p. 164">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p=164}}</ref> the National Security Council proposed to reinforce pro-Western alliance systems and quadruple spending on defense.<ref name = "Lefeber 1991" /> | |||

| ===German rearmament=== | |||

| US officials moved thereafter to expand containment into Asia, Africa, and Latin America, in order to counter revolutionary nationalist movements, often led by Communist parties financed by the USSR, fighting against the restoration of Europe's colonial empires in South-East Asia and elsewhere.<ref name="Gaddis 2005, p. 212">{{Harvnb|Gaddis|2005|p= 212}}</ref> In the early 1950s (a period sometimes known as the "]"), the US formalized a series of alliances with Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Thailand and the Philippines (notably ] and ]), thereby guaranteeing the United States a number of long-term military bases.<ref name = "Byrd" /> | |||

| {{Main|West German rearmament}} | |||

| ] and ] sworn into the newly founded '']'' by ] in November 1955]] | |||

| The rearmament of West Germany was achieved in the early 1950s. Its main promoter was ], the chancellor of West Germany, with France the main opponent. Washington had the decisive voice. It was strongly supported by the Pentagon (the US military leadership), and weakly opposed by President Truman; the State Department was ambivalent. The outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950 changed the calculations and Washington now gave full support. That also involved naming ] in charge of NATO forces and sending more American troops to West Germany. There was a strong promise that West Germany would not develop nuclear weapons.{{sfn|Beisner|2006|pp=356–374}} | |||

| Widespread fears of another rise of ] necessitated the new military to operate within an alliance framework under ] command.{{sfn|Snyder|2002}} In 1955, Washington secured full German membership of NATO.{{sfn|Byrd|2003}} In May 1953, ], by then in a government post, had made an unsuccessful proposal to allow the reunification of a neutral Germany to prevent West Germany's incorporation into NATO, but his attempts were cut short after he was ] during a Soviet power struggle.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=105}} The events led to the establishment of the '']'', the West German military, in 1955.{{sfn|Large|1996|p={{pn|date=August 2024}}}}{{sfn|Hershberg|1992}} | |||

| ===Chinese Civil War, SEATO, and NSC 68=== | |||

| {{Main|Cold War in Asia}} | |||

| ] and ] in Moscow, December 1949]] | |||

| In 1949, ]'s ] defeated ]'s United States-backed ] (KMT) Nationalist Government in China. The KMT-controlled territory was now ] to the island of ], the nationalist government of which exists to this day. The Kremlin promptly created an alliance with the newly formed People's Republic of China.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=39}} According to Norwegian historian ], the communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang Kai-Shek made, and because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonized too many interest groups in China. Moreover, his party was weakened during the ]. Meanwhile, the communists told different groups, such as the peasants, exactly what they wanted to hear, and they cloaked themselves under the cover of ].{{sfn|Westad|2012|p=291}} | |||

| Confronted with the ] and ] in 1949, the Truman administration quickly moved to escalate and expand its ] doctrine.{{sfn|LaFeber|1993|pp=194–197}} In ], a secret 1950 document, the National Security Council proposed reinforcing pro-Western alliance systems and quadrupling spending on defense.{{sfn|LaFeber|1993|pp=194–197}} Truman, under the influence of advisor ], saw containment as implying complete ] of Soviet influence in all its forms.{{sfn|Layne|2007|pp=63–66}} | |||

| United States officials moved to expand this version of containment into ], ], and ], in order to counter revolutionary nationalist movements, often led by communist parties financed by the USSR.{{sfn|Gaddis|2005|p=212}} In this way, this US would exercise "]," oppose neutrality, and ] ].{{sfn|Layne|2007|pp=63–66}} In the early 1950s (a period sometimes known as the "]"), the US formalized a series of alliances with ] (a former WWII enemy), ], ], ], ], ] and the ] (notably ] in 1951 and ] in 1954), thereby guaranteeing the United States a number of long-term military bases.{{sfn|Byrd|2003}} | |||

| ===Korean War=== | ===Korean War=== | ||

| {{ |

{{Main|Division of Korea|Korean War|Rollback}} | ||

| ], UN Command CiC (seated), observes the naval shelling of ], Korea from ], 15 September 1950.]] | |||

| One of the more significant impacts of containment was the outbreak of the ]. In June 1950, ]'s ] invaded South Korea.<ref name="Stokesbury1990">{{cite book |title= A Short History of the Korean War|last=Stokesbury |first= James L|year= 1990|publisher=Harper Perennial |location= New York|isbn= 0688095135|pg=14}}</ref> To Stalin's surprise,<ref name = "Lefeber 1991" /> the UN Security Council backed the defense of South Korea, though the Soviets were then boycotting meetings to protest that ] and not ] held a permanent seat on the Council.<ref>{{Harvnb|Malkasian|2001|p=16}}</ref> A UN force of personnel from ], the ], the ], ], ], ], ], the ], the ], ], ] and other countries joined to stop the invasion.<ref>Fehrenbach, T. R., ''This Kind of War: The Classic Korean War History'', Brasseys, 2001, ISBN 1574883348, page 305</ref> | |||