| Revision as of 05:42, 25 August 2010 editCaspian blue (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers35,434 editsm →Synopsis: too long plot or it needs some division← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 11:46, 22 December 2024 edit undoSporkBot (talk | contribs)Bots1,245,159 editsm Remove template per TFD outcome | ||

| (844 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|1957 film by Ingmar Bergman}} | |||

| :''For the Biblical concept, see ]. For the Rakim album, see ]. | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox film | {{Infobox film | ||

| | name |

| name = The Seventh Seal | ||

| | image |

| image = Seventhsealposter.jpg | ||

| | caption |

| caption = Theatrical release poster | ||

| | director |

| director = ] | ||

| | |

| producer = ] | ||

| | screenplay = Ingmar Bergman | |||

| | starring = ]<br />]<br />]<br />] | |||

| | based_on = {{Based on|''Trämålning''|Ingmar Bergman}} | |||

| | music = ] | |||

| | |

| starring = {{Plain list| | ||

| * ] | |||

| | editing = ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | music = ] | |||

| | cinematography = ] | |||

| | editing = Lennart Wallén | |||

| | distributor = ] | | distributor = ] | ||

| | released = |

| released = {{Film date|df=yes|1957|02|16}} | ||

| | runtime = 96 minutes<!--Theatrical runtime: 96:09--><ref>{{cite web |title=THE SEVENTH SEAL |url=http://www.bbfc.co.uk/releases/seventh-seal-1 |publisher=] |access-date=29 June 2013}}</ref> | |||

| | runtime = 96 min. | |||

| | country = |

| country = Sweden | ||

| | language = |

| language = {{Plain list| | ||

| * Swedish | |||

| | budget = US$150,000 (estimated) | |||

| * Latin | |||

| | gross = }} | |||

| }} | |||

| | budget = ]150,000{{Sfn|Bragg|1998|p=49}} | |||

| }} | |||

| '''''The Seventh Seal''''' ({{langx|sv|Det sjunde inseglet}}) is a 1957 Swedish ] film written and directed by ]. Set in Sweden<ref>{{cite book |last=Raw |first=Laurence |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=NG64WN7WruAC |title=The Ridley Scott Encyclopedia |publisher=The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc. |year=2009 |page=284|isbn=9780810869523}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last=Litch |first=Mary M. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bItUHBmB8YIC |title=Philosophy Through Film |publisher=Routledge |year=2010 |page=193 |isbn=9780203863329}}</ref> during the ], it tells of the journey of a medieval ] (]) and a game of ] he plays with the ] (]), who has come to take his life. Bergman developed the film from his own play ''Wood Painting''. The title refers to a passage from the ], used both at the very start of the film and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when ] had opened the ], there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour."<ref>{{bibleverse|Rev.|8:1|KJV}}</ref> Here, the motif of silence refers to the "silence of God," which is a major theme of the film.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=45}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.criterion.com/current/posts/1171-the-seventh-seal-there-go-the-clowns |title=''The Seventh Seal'': There Go the Clowns |last=Giddins |first=Gary |publisher=The Criterion Collection |date=15 June 2009 |access-date=7 April 2015}}</ref> | |||

| ''The Seventh Seal'' is considered a classic in the ], as well as one of the ]. It established Bergman as a director, containing scenes which have become iconic through homages, critical analysis, and parodies. | |||

| '''''The Seventh Seal''''' ({{lang-sv|'''Det sjunde inseglet'''}}) is a ] ] film directed by ]. Set during the ], it tells of the journey of a medieval ] (]) and a game of ] he plays with the personification of ], who has come to take his life. Bergman developed the film from his own play ''Wood Painting''. The title refers to a passage from the ], used both at the very start of the film, and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when the Lamb had opened the ], there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour" (] 8:1). Here the motif of silence refers to the "silence of God" which is a major theme of the film.<ref>{{cite book | url= http://books.google.com/books?id=oahZAAAAMAAJ&q=Melvyn+Bragg+(Det+Sjunde+Inseglet)&dq=Melvyn+Bragg+(Det+Sjunde+Inseglet) | author= ] | title= The Seventh Seal (Det Sjunde Inseglet) |publisher= BFI Publishing | year= 1998|page = 45}}</ref> | |||

| ==Plot== | |||

| The film is considered a major classic of world cinema. It helped Bergman to establish himself as a world-renowned director and contains scenes which have become iconic through parodies and homages. | |||

| <!-- Please review ] before adding material. Plot summaries should not exceed 700 words. --> | |||

| Disillusioned knight Antonius Block and his cynical ] Jöns return from the ] to find the country ravaged by ]. The knight encounters Death, whom he challenges to a ] match, believing he can survive as long as the game continues. | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Synopsis== | |||

| The knight and his squire pass a caravan of actors: Jof and his wife Mia, with their infant son Mikael and actor-manager Jonas Skat. Waking early, Jof has ], which he relates to a smilingly disbelieving Mia. | |||

| {{plot}} | |||

| Antonius Block (]), a knight, returns disillusioned, with his ] Jöns (]), from a ] and finds that his home country of Sweden is being ravaged by ]. To his dismay, Death (]) has come for him, as well. He challenges Death to a ] match. Death agrees to the terms: as long as Block resists, he lives. If he wins, he shall go free. | |||

| ] | |||

| Master and squire ride across a mossy heath beyond which the sea lies shimmering in the white glitter of the sun. Jöns seeks directions from a man who appears to be sleeping, but is actually dead. An actor, Jof, is shown sleeping in a wagon with his wife, Mia (who is also an actress), their son, Mikael and their manager, Skat. He wakes, ventures outside alone, and sees a vision of the Virgin Mary amongst the wind in the trees; however, when he tells his wife of this encounter, she appears not to believe him. | |||

| Block and Jöns visit a church where a fresco of the '']'' is being painted. The squire chides the artist for colluding in the ideological fervor that led to the crusade. In the ], Block tells the priest he wants to perform "one meaningful deed" after what he now sees as a pointless life. Upon revealing to him the ] that will save his life, the knight discovers that it is actually Death with whom he has been speaking. Leaving the church, Block speaks to a young woman condemned to be ] for consorting with the ]. He believes she will tell him about life beyond death, only to find that she is insane. | |||

| The knight and squire enter a grey stone church in a strange white mist where a fresco of the ] is being painted. Jöns discusses the plague with the painter, then draws a small figure to represent himself. "This is squire Jöns. He grins at Death, mocks the Lord, laughs at himself and leers at the girls. His world is a Jöns-world, believable only to himself, ridiculous to all including himself, meaningless to Heaven and of no interest to Hell."<ref>{{cite book| title = The Seventh Seal | author = ] | publisher = Touchstone | year= 1960 | pages = 148}}</ref> The knight Block approaches a priest in the ] booth: "My life has been a futile pursuit, a wandering, a great deal of talk without meaning. I feel no bitterness or self-reproach because the lives of most people are very much like this. But I will use my reprieve for one meaningful deed."<ref name="Bergman, 1960 p. 147">Bergman, 1960 p. 147.</ref> He goes on to confess his doubts about the existence of God, and, by consequence, his fear that life is ultimately pointless. The knight tells the priest that he is playing chess with Death and reveals his strategy, only to find that the priest is Death, hidden in the shadows. Upon exiting the church, Block sees a girl in chains who has been condemned for being a witch in league with the devil and is to be taken away and ]. He asks her if she is really familiar with the Devil, but she does not answer. | |||

| In a deserted village, Jöns saves a mute servant girl from being raped by Raval, a theologian who ten years earlier persuaded the knight to join the Crusades and is now a thief. Jöns vows to destroy his face if they meet again. Jöns kisses the servant girl, who resists his advance. He then tells her to repay her debt by becoming his servant. She reluctantly agrees. The group goes into town, where the actors are performing. There, Skat is enticed away for a tryst by Lisa, wife of the blacksmith Plog. The stage show is interrupted by a procession of ] led by a preacher who harangues the townspeople. | |||

| At the town's inn, Raval manipulates Plog and other customers into intimidating Jof. The bullying is broken up by Jöns, who slashes Raval's face. The knight and squire are joined by Jof's family and a repentant Plog. Block enjoys a picnic of milk and wild strawberries that Mia has gathered and promises to remember that evening for the rest of his life. | |||

| Later, at a public house, Jof comes across Raval and Plog, a blacksmith, who is grieving because his wife had recently left him for an actor (later revealed to have been Skat). Knowing that Jof is an actor, Raval accuses him of being the one, and attempts to humiliate the innocent performer by forcing him to dance on the tables like a bear. However, Jöns appears and stays true to his word, dealing a rough justice by cutting Raval with a knife from forehead to cheek.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 164-165</ref> Jöns then consoles Plog, and convinces the smith to come along with him. | |||

| He then invites Plog and the actors to shelter from the plague in his castle. When they encounter Skat and Lisa in the forest, she returns to Plog, while Skat fakes a remorseful suicide. As the group moves on, Skat climbs a tree to spend the night, but Death appears beneath and cuts down the tree. | |||

| The knight and Death continue their game, but Block sees the evening light move across a wagon to the actress Mia and her little child. He walks over. She tells him that the actor Skat has run off and left them and that they plan to visit the saint's feast at ]. He warns them against this as "the plague has spread in that direction...people are dying by the tens of thousands."<ref>Bergman, 1960 pp. 165 and 169.</ref> When Mia's husband Jof returns, the knight finds solace in a quiet, pleasant picnic of milk and wild strawberries with the family. Antonius Block explains how much he loved his own wife before he left her for the ]. He also shares with Mia his ongoing burden, the burden of faith, which he describes as loving someone in the dark who never comes. However, it is the simple and harmonious moments like this in which he states he is able to find comfort and which he wishes to remember: "I'll carry this memory between my hands as if it were bowl filled to the brim with fresh milk...And it will be an adequate sign-it will be enough for me."<ref name="Bergman, 1960 p.172">Bergman, 1960 p.172.</ref> He invites them to his ], where they will be safe from the plague. | |||

| Meeting the condemned woman being drawn to execution, Block asks her to summon ] so he can question him about God. The girl claims she has done so, but the knight only sees her terror and gives her herbs to take away her pain as she is placed on the pyre. | |||

| Block, Mia, Jof, Mikael, Jöns and Plog head through the forest, and along the way they come across Skat and Lisa (Plog's wife). After being threatened by an enraged Plog, Lisa quickly leaves Skat and returns to him. Skat then stabs himself to avoid receiving the brunt of Plog's wrath. Shaken by the actor's sudden suicide, the group moves on; once they have gone, Skat sits up, unharmed, having faked the stabbing with a trick knife. | |||

| ].'']] | |||

| Death finds the missing actor Skat hiding up a tree and begins sawing it down. Skat protests but Death insists his time is up. "No, I have my performance", says Skat. "Then it's been cancelled because of death", is the reply. "Aren't there any special rules for actors?" "No, not in this case."<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 187</ref> | |||

| They encounter Raval, stricken by the plague. Jöns stops the servant girl from uselessly bringing him water, and Raval dies alone. Jof then sees the knight playing chess with Death and decides to flee with his family, while Block knowingly keeps Death occupied. | |||

| As Death states "No one escapes me", Block knocks the chess pieces over but Death restores them to their place. On the next move, Death wins the game and announces that when they meet again, it will be the last time for all. Death then asks Block if he achieved the "meaningful deed" he wished to accomplish. The knight replies that he has. | |||

| ]".]] | |||

| They next come across the young girl from the church, who had been declared a ]. The Knight demands of the monk: "What have you done with the child?"<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 181</ref> Jöns' ] is sympathetic to the girl and he contemplates killing her executioners, but decides against it as she is almost dead anyway. Block asks her again to summon ] for him; he wants to ask the ] about ]. The girl, in a state that Block describes as her "terror", claims already to have done so, but Block (and the audience) cannot see him. He gives her an herb which he says will take away her pain, and then leaves, his dilemma unanswered.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p.135</ref> | |||

| Block is reunited with his wife and the party shares a final supper, interrupted by Death's arrival. The other members of the party then introduce themselves, and the mute servant girl greets him with "]" | |||

| The robber Raval that Jöns branded later appears dying of the ], pleading for water. The mute servant girl attempts to bring him some, but is stopped by Jöns, who exclaims, "It's meaningless. Can't you hear that I'm consoling you?"<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 190</ref> The robber then dies. Jof, the actor tells his wife Mia that he can see the Knight playing chess with Death and decides to immediately escape with his family.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 191.</ref> | |||

| Jof and his family have sheltered in their caravan from a storm, which he interprets as the Angel of Death passing by. In the morning, Jof ] the knight and his companions being led away over the hillside in a Dance of Death. | |||

| Antonius Block pretends to be clumsy and knocks the ] pieces over, distracting Death long enough for the family of actors he has befriended to slip away. Once the pieces have been replaced on the board, Death then places the knight in check-mate, winning the game, and announces that when they meet again Block's time—and the time of all those still travelling with him—will be up. Before departing, Death asks if Block has accomplished his one "meaningful deed" yet; Block replies that he has. The knight is reunited with his wife at his castle, she having waited there alone for him. The party shares one "last supper" before Death comes for them through the twilight of the "large, murky room where the burning torches throw uneasy shadows over the ceiling and walls."<ref name="berg-p195">Bergman, 1960 p. 195.</ref> At the final moment, Block pleads to God: "Have mercy on us, because we are small and frightened and ignorant." Jöns's girl, on her knees, smiles and announces, "It is finished."<ref name="berg-p195"/> | |||

| Meanwhile, the little family of actors and jugglers have endured a strange light and roar in the forest which the father, Jof, interprets to be "the ''Angel of Death'' and he's very big." They now awaken listening to the rain tapping on the wagon canvas and crawl out, noticing "the dark retreating sky where summer lightning glitters like silver needles" over the ridges, forests, wide plains and sea.<ref name="berg-p197">Bergman, 1960 p. 197</ref> Jof, with his ], sees a vision of the knight and his followers being led away over the hills in a solemn ]. "They dance away from the dawn and it's a solemn dance towards the dark lands, while the rain washes...and cleans the salt of their tears from their cheeks."<ref name="berg-p197"/> His wife, Mia, turns to him and says "You with your visions and dreams." | |||

| ==Cast== | ==Cast== | ||

| {{div col|colwidth=22em}} | |||

| * ] as Antonius Block, knight | |||

| * ] |

* ] – Jöns, squire | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Death | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Jof | ||

| * ] – Antonius Block, knight | |||

| * ] as Death | |||

| * ] |

* ] – Mia | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Karin | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Blacksmith Plog | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Lisa | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Jonas Skat | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Raval, the thief | ||

| * ] |

* ] – Mute girl | ||

| * ] – Witch | |||

| * ] as ], church painter | |||

| * ] – church painter | |||

| * ] as The Monk | |||

| * ] – The Monk | |||

| * Lars Lind as Young monk | |||

| * ] |

* ] – Merchant | ||

| * ] – Maid | |||

| * Tor Borong as Farmer | |||

| * Lars Lind – Young monk | |||

| * ] as Maid | |||

| * Tor Borong – Farmer | |||

| * Harry Asklund as Inn keeper | |||

| * Harry Asklund – Inn keeper | |||

| * Ulf Johanson as Jack's leader | |||

| * ] – Jack's leader (uncredited) | |||

| {{div col end|3}} | |||

| == |

==Themes== | ||

| The title refers to a passage about the end of the world from the ], used both at the very start of the film, and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when the Lamb had opened the ], there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour" (] 8:1). Thus, in the confessional scene the knight states: "Is it so cruelly inconceivable to grasp God with the senses? Why should He hide himself in a mist of half-spoken promises and unseen miracles?...What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but aren't able to?"{{sfn|Bergman|1960|pp=145–146}} Death, impersonating the confessional priest, refuses to reply. Similarly, later, as he eats the strawberries with the family of actors, Antonius Block states: "] is a torment – did you know that? It is like loving someone who is out there in the darkness but never appears, no matter how loudly you call."{{sfn|Bergman|1960|p=172}} ] notes that the concept of the "Silence of God" in the face of evil, or the pleas of believers or would-be-believers, may be influenced by the punishments of silence meted out by Bergman's father, a chaplain in the State ] Church.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|pp=40, 45}} In Bergman's original radio play sometimes translated as ''A Painting on Wood'', the figure of Death in a ] is represented not by an actor, but by ], "mere nothingness, mere absence...terrifying...the void."<ref>Martin Esslin. ''Mediations: Essays on Brecht, Beckett and the Media''. Abacus. London. 1980. p. 181.</ref> | |||

| Bergman originally wrote the play ''Trämålning'' (''Wood Painting'') in 1953/1954 for the acting students of ]. The first time it was performed in public was in radio in 1954, directed by Bergman. He also directed it on stage in ] the next spring, and in the autumn it was staged in ], directed by ] who would later play the character Death in the film version.<ref name=svenskfilmografi> (in Swedish). ]. Retrieved on 2009-08-17.</ref> | |||

| Some of the powerful influences on the film were ]'s picture of the two acrobats, ]'s '']'', ]'s dramas ''Folkungasagan'' ("The Saga of the Folkung Kings") and '']'',<ref>{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5xYa6Q9VPfoC |author=Egil Törnqvist |title=Bergman's Muses: Æsthetic Versatility in Film, Theatre, Television and Radio |publisher=McFarland & Company, Inc. |year=2003 |page=218 |isbn=9780786482023}}</ref> the frescoes at Härkeberga church, and a painting by ] in Täby church.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=49}} Just prior to shooting, Bergman directed for radio the play ''Everyman'' by ].{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=49}} By this time he had also directed plays by ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=29}} The actors ] (with whom Bergman was in a relationship from 1955 to 1959) who played the juggler's wife Mia, and ], whose role as the knight was the first of many star parts he would bring to Bergman's films and whose rugged Nordic dignity became a vital resource within Bergman's "troupe" of key actors,<ref>Höök, Marianne, ''Ingmar Bergman'', Wahlström & Widstrand, Stockholm, 1962 p.115f</ref> both made a strong impact on the mood and style of the film. | |||

| In his autobiography, ''The Magic Lantern'', Bergman wrote that "''Wood Painting'' gradually became ''The Seventh Seal'', an uneven film which lies close to my heart, because it was made under difficult circumstances in a surge of vitality and delight."<ref>Ingmar Bergman. The Magic Lantern. Penguin Books. London. 1988 p 274.</ref> The script for the ''Seventh Seal'' was commenced while Bergman was in the ] in ] recovering from a stomach complaint.<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 27.</ref> It was at first rejected{{Who|date=January 2010}} and Bergman was given the go-ahead for the project from Carl-Anders Dymling at ] only after the success at Cannes of '']''<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 48.</ref> Bergman rewrote the script five times and was given a schedule of only thirty-five days and a budget of $150,000.<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 49.</ref> It was to be the seventeenth film he had directed.<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 46</ref> | |||

| Bergman grew up in a home infused with an intense Christianity, his father being a charismatic ] (this may have explained Bergman's adolescent infatuation with ], which later deeply tormented him).{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=44}} As a six-year-old child, Bergman used to help the gardener carry corpses from the Royal Hospital Sophiahemmet (where his father was chaplain) to the mortuary.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=43}} When as a boy he saw the film '']'', the fire scene excited him so much he stayed in bed for three days with a temperature.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=43}} Despite living a ] lifestyle in partial rebellion against his upbringing, Bergman often signed his scripts with the initials "S.D.G" (''Soli Deo Gloria'') — "To God Alone the Glory" — just as ] did at the end of every musical composition.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=28}} | |||

| All scenes except two were shot in or around the ] studios in ]. The exceptions were the famous opening scene with Death and the Knight playing chess by the sea and the ending with the dance of death, which were both shot at ], a rocky, precipitous beach area in north-western ].<ref name=f2f></ref> | |||

| ] writes: | |||

| In the ''Magic Lantern'' autobiography Bergman writes of the film's iconic penultimate shot: "The image of the Dance of Death beneath the dark cloud was achieved at hectic speed because most of the actors had finished for the day. Assistants, electricians, and a make-up man and about two summer visitors, who never knew what it was all about, had to dress up in the costumes of those condemned to death. A camera with no sound was set up and the picture shot before the cloud dissolved."<ref>Ingmar Bergman. The Magic Lantern. Penguin Books. London. 1988 pp. 274-275.</ref> | |||

| <blockquote>"Like ] in '']'', the Squire treats death as a bitter and hopeless joke. Since we all play chess with death, and since we all must suffer through that hopeless joke, the only question about the game is how long it will last and how well we will play it. To play it well, to live, is to love and not to hate the body and the mortal as the ] urges in Bergman's metaphor."<ref>Gerald Mast ''A Short History of the Movies.'' p. 405.</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ] writes: | |||

| ==Portrait of the Middle Ages== | |||

| <blockquote>"t is constructed like an argument. It is a story told as a sermon might be delivered: an allegory...each scene is at once so simple and so charged and layered that it catches us again and again...Somehow all of Bergman's own past, that of his father, that of his reading and doing and seeing, that of his Swedish culture, of his political burning and religious melancholy, poured into a series of pictures which carry that swell of contributions and contradictions so effortlessly that you could tell the story to a child, publish it as a storybook of photographs and yet know that the deepest questions of religion and the most mysterious revelation of simply being alive are both addressed."{{sfn|Bragg|1998|pp=64–65}}</blockquote> | |||

| ] | |||

| With regard to the relevancy of historical accuracy to a film that is heavily metaphorical and allegorical, John Alberth, writing in ''A Knight at the Movies'', holds | |||

| The Jesuit publication ''America'' identifies it as having begun "a series of seven films that explored the possibility of faith in a post-Holocaust, nuclear age".<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.americamagazine.org/content/article.cfm?article_id=10155 |title=Ingmar Bergman, Theologian? |author=Richard A. Blake |date=27 August 2007 |publisher=America magazine |access-date=14 December 2010}}</ref> Likewise, film historians Thomas W. Bohn and Richard L. Stromgren identify this film as beginning "his cycle of films dealing with the conundrum of religious faith".<ref>{{cite book |title=Light and shadows: a history of motion pictures |last=Bohn |first=Thomas |author2=Richard L. Stromgren |year=1987 |publisher=Mayfield Pub. Co |isbn=978-0-87484-702-4|page=269 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Portrait of the Middle Ages=== | |||

| Medieval Sweden as portrayed in this movie includes creative anachronisms. The ] movement was foreign to Sweden, and large-scale ] only began in the 15th century.<ref>Said by Swedish historian ] in an introduction to the movie on ], 2005. Reiterated in his book ''Gud vill det!'' {{ISBN|91-7037-119-9}}</ref> In addition, the main period of the ] is well before this era; they took place in a more optimistic period.<ref name="Tuchman"/> | |||

| With regard to the relevancy of historical accuracy to a film that is heavily metaphorical and allegorical, John Aberth, writing in ''A Knight at the Movies'', holds | |||

| <blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| the film only partially succeeds in conveying the period atmosphere and thought world of the fourteenth century. Bergman would probably counter that it was never his intention to make an historical or period film. As it was written in a program note that accompanied the movie's premier "It is a modern poem presented with medieval material that has been very freely handled...The script in |

the film only partially succeeds in conveying the period atmosphere and thought world of the fourteenth century. Bergman would probably counter that it was never his intention to make an historical or period film. As it was written in a program note that accompanied the movie's premier "It is a modern poem presented with medieval material that has been very freely handled... The script in particular—embodies a mid-twentieth century existentialist angst... Still, to be fair to Bergman, one must allow him his artistic license, and the script's modernisms may be justified as giving the movie's medieval theme a compelling and urgent contemporary relevance... Yet the film succeeds to a large degree because it is set in the Middle Ages, a time that can seem both very remote and very immediate to us living in the modern world... Ultimately ''The Seventh Seal'' should be judged as a historical film by how well it combines the medieval and the modern."<ref>John Aberth (2003). ''A Knight at the Movies''. Routledge. pp. 217–218.</ref> | ||

| </blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| ], fresco by ]]] | |||

| Similarly defending it as an allegory, Aleksander Kwiatkowski in the book ''Swedish Film Classics'', writes | |||

| <blockquote> | <blockquote> | ||

| The international response to the film which among other awards won the jury's special prize at Cannes in 1957 reconfirmed the author' high rank and proved that ''The Seventh Seal'' regardless of its degree of accuracy in reproducing medieval scenery may be considered as a universal, timeless allegory.<ref>''Swedish Film Classics by Aleksander Kwiatkowski'', Svenska filminstitutet p. 93</ref> | The international response to the film which among other awards won the jury's special prize at Cannes in 1957 reconfirmed the author's high rank and proved that ''The Seventh Seal'' regardless of its degree of accuracy in reproducing medieval scenery may be considered as a universal, timeless allegory.<ref>''Swedish Film Classics by Aleksander Kwiatkowski'', Svenska filminstitutet p. 93</ref> | ||

| </blockquote> | </blockquote> | ||

| Much of the film's imagery is derived from medieval art. For example, Bergman has stated that the image of a man playing chess with a skeletal Death was inspired by a medieval church painting from the 1480s in ], ], north of ], painted by ].<ref>Stated in Marie Nyreröd's interview series (the first part named ''Bergman och filmen'') aired on ] Easter 2004.</ref> | Much of the film's imagery is derived from medieval art. For example, Bergman has stated that the image of a man playing chess with a skeletal Death was inspired by a medieval church painting from the 1480s in ], ], north of ], painted by ].<ref>Stated in Marie Nyreröd's interview series (the first part named ''Bergman och filmen'') aired on ] Easter 2004.</ref> | ||

| Generally speaking, historians ], ] and ] have all argued that the ] of the 14th century was a period of "doom and gloom" similar to what is reflected in this film, characterized by a feeling of pessimism, an increase in a penitential style of piety that was slightly masochistic, all aggravated by various disasters such as the Black Death, famine, the ] between France and England, and the ].<ref name="Tuchman">Barbara Tuchman (1978). ''''. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. {{ISBN|0-394-40026-7}}</ref> This is sometimes called the ], and Tuchman regards the 14th century as "]" of the 20th century in a way that echoes Bergman's sensibilities. | |||

| However, the medieval Sweden portrayed in this movie includes creative anachronisms. The last crusade (the ]) ended in 1271, and the Black Death hit Europe in 1348. In addition, the flagellant movement was foreign to Sweden; large-scale witch persecutions only began in the 15th century.<ref>Said by Swedish historian ] in an introduction to the movie on ], 2005. Reiterated in his book ''Gud vill det!'' ISBN 91-7037-119-9</ref> | |||

| ==Production== | |||

| Generally speaking, historians ] and ] and ] have all argued that the late Middle Ages of the 14th century was a period of "doom and gloom" similar to what is reflected in this film, characterized by a feeling of pessimism, an increase in a penitential style of piety that was slightly masochistic, all aggravated by various disasters such as the Black Plague, famine, the ] between France and England, and papal schism.<ref>Barbara Tuchman. A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century Alfred A. Knopf New York 1978 ISBN 0394400267</ref> This is sometimes called the ] and Barbara Tuchman regards the 14th century as "]" of the 20th century in a way that echoes Bergman's sensibilities. Nonetheless, the period of the Crusades is well before this era; they took place in a more optimistic period.<ref>Barbara Tuchman A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century Alfred A. Knopf New York 1978 ISBN 0394400267</ref> | |||

| ===Development=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] originally wrote the play ''Trämålning'' (''Wood Painting'') in 1953 / 1954 for the acting students of ]. Its first public performance, which he directed, was on radio in 1954. He also directed it on stage in Malmö the next spring, and in the autumn it was staged in Stockholm, directed by ], who would later play the character Death in the film version.<ref name=svenskfilmografi> (in Swedish). ]. Retrieved on 17 August 2009.</ref> | |||

| In his autobiography, ''The Magic Lantern'', Bergman wrote that "''Wood Painting'' gradually became ''The Seventh Seal'', an uneven film which lies close to my heart, because it was made under difficult circumstances in a surge of vitality and delight."<ref>Ingmar Bergman (1988). ''The Magic Lantern''. Penguin Books. London. p. 274.</ref> The script for ''The Seventh Seal'' was commenced while Bergman was in the ] in Stockholm recovering from a stomach complaint.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=27}} It was at first rejected<ref>Ingmar Bergman (1990). ''Images: My Life in Film''. Arcade Publishing, Inc. New-York. p. 234.</ref> by ], head of ] and Bergman was given the go-ahead for the project from Carl-Anders Dymling only after the success at Cannes of '']''.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=48}} Bergman rewrote the script five times and was given a schedule of only thirty-five days and a budget of $150,000.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=49}} It was to be the seventeenth film he had directed.{{sfn|Bragg|1998|p=46}} | |||

| ==Chess in the film== | |||

| The chess game opens with the knight holding out his two fists and Death choosing the black pawn ("You are black", says Block. "It becomes me well." replies Death). The first moves of each use the king's pawn.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 135.</ref> In the confessional, the knight says "I use a combination of the bishop and the knight which he hasn't yet discovered. In the next move I'll shatter one of his flanks." Death (in disguise as the priest) replies "I'll remember that."<ref name="Bergman, 1960 p. 147"/> When they play by the beach, the knight says: "Because I revealed my tactics to you I'm in retreat. It's your move." Death takes the knight piece. "You did the right thing" states the knight "you fell right in the trap. Check! Don't worry about my laughter, save your king instead." Death's response is to lean over the chess board and make a psychological move "Are you going to escort the juggler and his wife through the forest? Those whose names are Jof and Mia and who have a small son." "Why do you ask?" says the knight. "Oh, no reason" replies Death.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 172.</ref> Immediately after the death of the robber Raval, Death raises his hand and strikes the knight's queen. "I didn't notice that" says the knight.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 190.</ref> This is portrayed as a major setback. However, the queen was not as powerful as it currently is until many centuries after the time period of this film, when a chess-variant initially called ] became more popular than the traditional game. In one of the last scenes, the knight pretends to knock over the pieces so the young family of jugglers can escape while Death is reconstructing the game. "You are mated on the next move, Antonius Block" says Death. "That's true" says the knight. "Did you enjoy your reprieve?" "Yes, I did" Block replies.<ref>Bergman, 1960 p. 192.</ref> | |||

| == |

===Filming=== | ||

| All scenes except two were shot in or around the ] studios in Solna. The exceptions were the famous opening scene with Death and the Knight playing chess by the sea, and the ending with the ], which were both shot at ], a rocky, precipitous beach area in north-western Scania.<ref name=f2f> {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100823185840/http://www.ingmarbergman.se/page.asp?guid=0A7C85BA-E1D8-410F-B9E0-95A5DC3CC844 |date=23 August 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The title refers to a passage about the end of the world from the ], used both at the very start of the film, and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when the Lamb had opened the ], there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour" (] 8:1). Thus, in the confessional scene the knight states: "Is it so cruelly inconceivable to grasp God with the senses? Why should he hide himself in a mist of half-spoken promises and unseen miracles?...What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but aren't able to?"<ref>Bergman, 1960 pp. 145-146.</ref> Death, impersonating the confessional priest, refuses to reply. Similarly, later, as he eats the strawberries with the little family of actors, Antonius Block says: "] is a torment – did you know that? It is like loving someone who is out there in the darkness but never appears, no matter how loudly you call."<ref name="Bergman, 1960 p.172"/> ] notes that the concept of the "Silence of God" in the face of evil, or the pleas of believers or would-be-believers, may be influenced by the punishments of silence meted out by Bergman's father, a chaplain in the State ] Church.<ref>Bragg, 1998 pp. 40,45</ref> Interestingly, in Bergman's original radio play sometimes translated as ''A Painting on Wood'', the figure of ] in a ] is represented not by an actor, but by ], "mere nothingness, mere absence...terrifying...the void."<ref>Martin Esslin. Mediations. Essays on Brecht, Beckett and the Media. Abacus. London. 1980. p181.</ref> | |||

| In the ''Magic Lantern'' autobiography Bergman writes of the film's iconic penultimate shot: "The image of the Dance of Death beneath the dark cloud was achieved at hectic speed because most of the actors had finished for the day. Assistants, electricians, and a make-up man and about two summer visitors, who never knew what it was all about, had to dress up in the costumes of those condemned to death. A camera with no sound was set up and the picture shot before the cloud dissolved."<ref>Ingmar Bergman (1988). ''The Magic Lantern''. Penguin Books. London. pp. 274–275.</ref> | |||

| Strong influences on the film were ] who played the juggler's wife Mia (and with whom Bergman was in love), ]'s picture of the two acrobats, ]'s ], ]'s ''Folk Sagas'' and ''To Denmark'', the frescoes at Haskeborga church and a painting by ] in Täby kyrka.<ref name="Bragg, 1998 p. 49">Bragg, 1998 p. 49</ref> Just prior to shooting Bergman directed for radio the ''Play of Everyman'' by Hugo von Hofmannstahl.<ref name="Bragg, 1998 p. 49"/> By this time he had also directed plays by ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 29</ref> | |||

| ==Reception== | |||

| Bergman grew up in a home infused with an intense Christianity, his father being a charismatic preacher (this may have explained Bergman's childhood infatuation with ] which later deeply tormented him).<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 44.</ref> As a six-year old child, Bergman used to help the gardener carry corpses from the Royal Hospital Sofia Lemmet (where his father was chaplain) to the mortuary.<ref name="Bragg, 1998 p. 43">Bragg, 1998 p. 43</ref> When, as a boy, he saw the film ''Black Beauty'', the fire scene excited him so much he stayed in bed for three days with a temperature.<ref name="Bragg, 1998 p. 43"/> Despite living a ] lifestyle in partial rebellion against his upbringing, Bergman often signed his scripts with the initials "S.D.G" (''Soli Deo Gloria'')-"To God Alone The Glory"-just as ] did at the end of every musical composition.<ref>Bragg, 1998 p. 28.</ref> | |||

| Upon its original Swedish release, ''The Seventh Seal'' was met with a somewhat divided critical response; its cinematography was widely praised, while "Bergman the scriptwriter lambasted."<ref name="BergmanReferenceGuide">{{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=eJCGNAlqB0gC&pg=PA224 |title=Ingmar Bergman: A Reference Guide |page=224 |last=Steene |first=Birgitta |publisher=] |date=2005 |isbn=978-9053564066}}</ref> The film won the ] for Best Non-Italian Film in 1961.{{CN|date=January 2023}} Swedish journalist and critic Nils Beyer, writing for '']'', compared it to ]'s '']'' and '']''. While finding Dreyer's films to be superior, he still noted that "it isn't just any director that you feel like comparing to the old Danish master." He also praised the usage of the cast, in particular Max von Sydow, whose character he described as "a pale, serious ] character with a face as if sculpted in wood", and "Bibi Andersson, who appears as if painted in faded watercolours but still can emit small delicious glimpses of female warmth." Hanserik Hjertén for '']'' started his review by praising the cinematography, but soon went on to describe the film as "a horror film for children" and said that beyond the superficial, it is mostly reminiscent of Bergman's "sophomoric films from the 40s."<ref name=svenskfilmografi /> | |||

| Bergman's international reputation, on the other hand, was largely cemented by ''The Seventh Seal''.<ref name="BergmanReferenceGuide"/> The film ranked 2nd on ]'s ] in 1958.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://alumnus.caltech.edu/~ejohnson/critics/cahiers.html|title=Cahiers du Cinema: Top Ten Lists 1951–2009|last=Johnson|first=Eric C.|website=alumnus.caltech.edu|language=en-US|access-date=17 December 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120327102838/http://alumnus.caltech.edu/~ejohnson/critics/cahiers.html|archive-date=27 March 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> ] had only positive things to say in his 1958 review for ''The New York Times'', and praised how the themes were elevated by the cinematography and performances: "the profundities of the ideas are lightened and made flexible by glowing pictorial presentation of action that is interesting and strong. Mr. Bergman uses his camera and actors for sharp, realistic effects."<ref>{{cite news |author-link=Bosley Crowther |last=Crowther |first=Bosley |date=14 October 1954 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1958/10/14/archives/seventh-seal-swedish-allegory-has-premiere-at-paris.html |title=Seventh Seal; Swedish Allegory Has Premiere at Paris |newspaper=] |access-date=21 March 2018}}</ref> Film critic ] called it "A magically powerful film."<ref>{{cite web|title=Pauline Kael Review: The Seventh Seal|url=http://www.uu.edu/org/lyceum/filmfest/hkael.htm|website=Heavy}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=The Seventh Seal|url=https://bampfa.org/event/seventh-seal-3|website=BAMPFA|date=25 November 2015 }}</ref> | |||

| ] writes, | |||

| <blockquote>"Like ] in '']'', the Squire treats death as a bitter and hopeless joke. Since we all play chess with death, and since we all must suffer through that hopeless joke, the only question about the game is how long it will last and how well we will play it. To play it well, to live, is to love and not to hate the body and the mortal as the ] urges in Bergman's metaphor."<ref>Gerald Mast ''A Short History of the Movies.'' p. 405</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The film is now regarded as a masterpiece of cinema.<ref>{{cite web |last=Ebert |first=Roger |author-link=Roger Ebert |title=The Seventh Seal |work=RogerEbert.com |publisher=Ebert Digital LLC |date=16 April 2000 |url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-the-seventh-seal-1957 |access-date=18 August 2007}}</ref> '']'' ranked ''The Seventh Seal'' at number 33 in its Top 250 "Best Films of the Century" list in 1999, based on a poll of critics.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.villagevoice.com/specials/take/one/full_list.php3?category=10 |title=Take One: The First Annual Village Voice Film Critics' Poll |access-date=27 July 2006 |year=1999 |work=The Village Voice |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070826201343/http://www.villagevoice.com/specials/take/one/full_list.php3?category=10 |archive-date=26 August 2007}}</ref> The film was included in "''The New York Times'' Guide to the Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made" in 2002.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/ref/movies/1000best.html |title=The Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made |newspaper=The New York Times |year=2002| access-date=7 December 2013 | archive-date=11 December 2013 | archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20131211043539/http://www.nytimes.com/ref/movies/1000best.html}}</ref> ''Empire'' magazine, in 2010, ranked it the eighth-greatest film of world cinema.<ref>{{cite web |title=The 100 Best Films of World Cinema – 8. The Seventh Seal |url=http://www.empireonline.com/features/100-greatest-world-cinema-films/default.asp?film=8 |work=] |date=11 June 2010}}</ref> In a poll held by the same magazine, it was voted 335th 'Greatest Movie of All Time' from a list of 500.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.empireonline.com/500/31.asp |title=Empire's 500 greatest movies of all time |work=Empire |access-date=2 September 2017 |archive-date=19 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121019214507/http://www.empireonline.com/500/31.asp |url-status=dead }}</ref> In addition, on the 100th anniversary of cinema in 1995, the ] included ''The Seventh Seal'' in its list of its ] for its thematic values.<ref>{{cite web |title=Vatican Best Films List |url=http://old.usccb.org/movies/vaticanfilms.shtml |publisher=Catholic News Service Media Review Office |access-date=18 December 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120422064928/http://old.usccb.org/movies/vaticanfilms.shtml |archive-date=22 April 2012 }}</ref> The film was included in film critic ]'s list of "]" in 2000.<ref>{{cite web|title=The Seventh Seal movie review (1957)|url=https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/great-movie-the-seventh-seal-1957|website=rogerebert.com|date=16 April 2000}}</ref> '']'' voted it at No. 45 on their list of ''100 Greatest Movies of All Time''.<ref>{{cite web|title = Entertainment Weekly's 100 Greatest Movies of All Time|url = http://www.filmsite.org/ew100.html|publisher = ]|access-date = 19 January 2009|url-status = live|archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20140331185517/http://www.filmsite.org/ew100.html|archive-date = 31 March 2014|df = dmy-all}}</ref> In 2007, the film was ranked at No. 13 by ]'s readers poll on the list of "40 greatest foreign films of all time".<ref>{{cite web|title=As chosen by you...the greatest foreign films of all time|url=https://www.theguardian.com/film/2007/may/11/1|website=]|date=11 May 2007}}</ref> Indian film maker ] praised the film saying "One can watch 'Seventh Seal' even without subtitles as it is most appealing to the eye."<ref>{{cite web|title=Kerala grieves for Ingmar Bergman|url=https://www.dnaindia.com/india/report-kerala-grieves-for-ingmar-bergman-1113248|website=DNA India|date=2 August 2007}}</ref> In January 2002, the film was voted at No. 82 on the list of the "Top 100 Essential Films of All Time" by the ].<ref name=Carr81>{{Cite book |last=Carr|first=Jay |title=The A List: The National Society of Film Critics' 100 Essential Films |year=2002 |publisher=Da Capo Press |isbn=978-0-306-81096-1 |page= |url=https://archive.org/details/alistnationalsoc00jayc |url-access=registration|access-date=27 July 2012 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|title=100 Essential Films by The National Society of Film Critics|url=https://www.filmsite.org/alist.html|website=filmsite.org}}</ref> In 2012, the film ranked 93rd on critic's poll and 75th on director's poll in ] magazine's ] list. In the earlier 2002 version of the list the film ranked 35th in critic's poll<ref>{{cite web|title=The Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 The Rest of Critic's List|url=http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/critics-long.html|website=old.bfi.org.uk|access-date=28 April 2021|archive-date=13 August 2016|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160813112813/http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/critics-long.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> and 31st in director's poll.<ref>{{cite web|title=Sight & Sound Top Ten Poll 2002 The Rest of Director's List|url=http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/directors-long.html|website=old.bfi.org.uk|access-date=28 April 2021|archive-date=1 February 2017|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170201155933/http://old.bfi.org.uk/sightandsound/polls/topten/poll/directors-long.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> In 2022 edition of Sight & Sound's ''Greatest films of all time'' list the film ranked 72nd in the director's poll.<ref>{{cite web|title=Directors' 100 Greatest Films of All Time|url=https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/directors-100-greatest-films-all-time|website=bfi.org}}</ref> In 2012 it was voted one of the 25 best Swedish films of all time by a poll of 50 film critics and academics conducted by film magazine FLM.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.flm.nu/2012/08/de-25-basta-svenska-filmerna-genom-tiderna/ |title=De 25 bästa svenska filmerna genom tiderna |date=30 August 2012 |work=Flm |language=Swedish |accessdate=30 August 2012}}</ref> In 2018 the film was ranked 30th in BBC's list of The 100 greatest foreign language films.<ref>{{cite web|title=The 100 Greatest Foreign Language Films|url= https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20181029-the-100-greatest-foreign-language-films|website=bbc|date=29 October 2018|access-date=10 January 2021}}</ref> In 2021 the film was ranked at No. 43 on ] magazine's list of ''The 100 best movies of all time''.<ref>{{cite web|title=The 100 best movies of all time|url=https://www.timeout.com/newyork/movies/best-movies-of-all-time|date=8 April 2021}}</ref> | |||

| ] writes, | |||

| <blockquote>"t is constructed like an argument. It is a story told as a sermon might be delivered: an allegory...each scene is at once so simple and so charged and layered that it catches us again and again...Somehow all of Bergman's own past, that of his father, that of his reading and doing and seeing, that of his Swedish culture, of his political burning and religious melancholy, poured into a series of pictures which carry that swell of contributions and contradictions so effortlessly that you could tell the story to a child, publish it as a storybook of photographs and yet know that the deepest questions of religion and the most mysterious revelation of simply being alive are both addressed."<ref>Bragg, 1998 pp. 64-65</ref></blockquote> | |||

| The film was selected as the Swedish entry for the ] at the ], but was not nominated.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.imdb.com/list/ls026790611/ |title=Sweden submissions to the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film |website=] |date=22 April 2018 |access-date=9 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite web | url=http://www.sfi.se/sfi/smpage.fwx?page=20268 | title=Swedish Film and the Oscars | work=] |language=sv | access-date=9 November 2019 |archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070223042152/http://www.sfi.se/sfi/smpage.fwx?page=20268 <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archive-date = 23 February 2007}}</ref> | |||

| ==Reception== | |||

| Upon its original release in Sweden, ''The Seventh Seal'' was met by very positive reviews although not without reservations. Nils Beyer at '']'' compared it to ]'s '']'' and '']''. While finding Dreyer's films to be superior, he still noted that "it isn't just any director that you feel like comparing to the old Danish master." He also praised the usage of the cast, in particular Max von Sydow whose character he described as "a pale, serious ] character with a face as if sculpted in wood", and "Bibi Andersson, who appears as if painted in faded watercolours but still can emit small delicious glimpses of female warmth." Hanserik Hjertén for '']'' started his review by praising the cinematography, but soon went on to describe the film as "a horror film for children" and that beyond the superficial, it reminds a lot of Bergman's "sophomoric films from the 40s."<ref name=svenskfilmografi /> | |||

| On ], the film holds an approval rating of 93% based on 72 reviews, with an average rating of 9.20/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Narratively bold and visually striking, ''The Seventh Seal'' brought Ingmar Bergman to the world stage – and remains every bit as compelling today".<ref name=rotten>{{cite web |url=https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/seventh_seal/ |title=The Seventh Seal (1957) |publisher=] |work=] |access-date=18 August 2022 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170725024520/https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/seventh_seal/ |archive-date=25 July 2017 }}</ref> On ], the film has a rating of 88/100 based on 15 reviews, indicating "universal acclaim".<ref>{{cite web|title=The Seventh Seal|url=https://www.metacritic.com/movie/the-seventh-seal|website=]}}</ref> | |||

| ] had only positive things to say in his 1958 review for '']'', and praised how the themes were elevated by the cinematography and acting: "the profundities of the ideas are lightened and made flexible by glowing pictorial presentation of action that is interesting and strong. Mr. Bergman uses his camera and actors for sharp, realistic effects."<ref>] (1958-10-14) "." '']. Retrieved on 2009-08-17.</ref> | |||

| ==Influence== | |||

| The film has been regarded since its release as a masterpiece of ].<ref> | |||

| ''The Seventh Seal'' significantly helped Bergman in gaining his position as a world-class director. When the film won the ] at the ],<ref name="festival-cannes.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3563/year/1957.html |title=Festival de Cannes: The Seventh Seal |access-date=8 February 2009 |work=festival-cannes.com}}</ref> the attention generated by it (along with the previous year's '']'') made Bergman and his stars Max von Sydow and Bibi Andersson well known to the European film community, and the critics and readers of '']'', among others, discovered him with this movie. Within five years of this, he had established himself as the first real ] of Swedish cinema. With its images and reflections upon death and the meaning of life, ''The Seventh Seal'' had a symbolism that was "immediately apprehensible to people trained in literary culture who were just beginning to discover the 'art' of film, and it quickly became a staple of high school and college literature courses... Unlike Hollywood 'movies,' ''The Seventh Seal'' clearly was aware of elite artistic culture and thus was readily appreciated by intellectual audiences."<ref>{{cite book |last=Monaco |first=James |title=How To Read a Film |publisher=] |year=2000 |pages=311–312 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TSSfJb011QgC |isbn=978-0-19-513981-5}}</ref> | |||

| {{cite web | last =Ebert | first =Roger | authorlink =Roger Ebert | coauthors = | title =Great Movies — The Seventh Seal | work = | publisher = | date =2000-04-16 | url =http://rogerebert.suntimes.com/apps/pbcs.dll/article?AID=/20000416/REVIEWS08/401010358/1023 | format = | doi = | accessdate =2007-08-18}}</ref> It was Ranked #8 in '']'' magazines "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema" in 2010.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| | title = The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema | 8. The Seventh Seal | |||

| | url = http://www.empireonline.com/features/100-greatest-world-cinema-films/default.asp?film=8 | |||

| | work = Empire | |||

| }} | |||

| </ref> | |||

| === Film and television === | |||

| ==Impact== | |||

| ] as ]]] | |||

| ''The Seventh Seal'' significantly helped Bergman in gaining his position as a world-class director. When the film won the ] at the ],<ref name="festival-cannes.com">{{cite web |url=http://www.festival-cannes.com/en/archives/ficheFilm/id/3563/year/1957.html |title=Festival de Cannes: The Seventh Seal |accessdate=2009-02-08|work=festival-cannes.com}}</ref> the attention generated by it (along with the previous year's '']'') made Bergman and his stars Max von Sydow and Bibi Andersson well-known to the European film community, and the critics and readers of '']'', among others, discovered him with this movie. Within five years of this, he had established himself as the first real ] of Swedish cinema. With its images and reflections upon death and the meaning of life, ''The Seventh Seal'' had a symbolism that was "immediately apprehensible to people trained in literary culture who were just beginning to discover the 'art' of film, and it quickly became a staple of high school and college literature courses... Unlike Hollywood 'movies,' ''The Seventh Seal'' clearly was aware of elite artistic culture and thus was readily appreciated by intellectual audiences."<ref>Monaco, James. How To Read a Film. Oxford University Press. New York. 1977 pp. 256-257.</ref> | |||

| The representation of Death as a white-faced man who wears a dark cape and plays chess with mortals has been a popular object of parody in other films and television. | |||

| Several films and comedy sketches portray Death as playing games other than or in addition to chess. In the final scene of the 1968 film '']'' (mock Swedish for "The Dove"), a 15-minute ] of Bergman's work generally and his '']'' in particular, the protagonist plays badminton against Death, and wins when the droppings of a passing dove strike Death in the eye. The photography imitates throughout the style of Bergman's cinematographers ] and ].<ref>, a 30 July 2007 ''Slate'' article</ref> The film is also parodied in '']'' (1991), with the titular characters meeting Death and challenging him to several contemporary games.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.avclub.com/the-best-bill-ted-movie-is-the-one-that-took-them-on-1846416931 |last=Hassenger |first=Jesse |title=The best Bill & Ted movie is the one that took them on a Bogus Journey to hell and back |website=] |date=10 March 2021 |access-date=10 November 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Parody== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| The representation of Death as a white-faced man in a dark cape has been a popular object of parody in other films. One that is exclusively focused on Bergman is a 15-minute parody of Ingmar Bergman's '']'' entitled '']'' (mock Swedish for "The Dove"), which contains a final scene in which the protagonist plays badminton with Death and Death is defeated when a dove swoops from the sky and drops faeces in Death's eye. The photography imitates throughout the style of Bergman's great cinematographer Sven Nykqvist.<ref>, a July 30, 2007 ''Slate'' article</ref> | |||

| === Popular music === | |||

| Woody Allen is an enormous fan of Ingmar Bergman and references his work in his serious dramas as well as his comedies,<ref>See "The films of Woody Allen" by Sam Girgus p. 132</ref> including '']'', a film which broadly parodies 19th-century Russian novels with a closing "Dance of Death" scene imitating Bergman. | |||

| The film is referred to in several songs. The plot is recapitulated in ]'s "The Seventh Seal" from his album '']''.<ref></ref> There is a passing reference in ]'s song "How I Spent My Fall Vacation", from his album '']'', in which the song's narrative is bracketed by two young men watching the film in a cinema.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://cockburnproject.net/songs&music/hismfv.html |website=The Cockburn Project |access-date=16 September 2018 |title=Bruce Cockburn – Songs – How I Spent My Fall Vacation}}</ref> On ]'s album '']'' (2003), the title track was inspired by the final scene of ''The Seventh Seal'' where, according to guitarist ], "these figures on the horizon start doing a little jig, which is the dance of death."<ref name="Wall373">{{cite book |author=Wall, Mick |title=Iron Maiden: Run to the Hills, the Authorised Biography |edition=3rd |publisher=Sanctuary Publishing |year=2004 |isbn=978-1-86074-542-3 |page=373 |author-link=Mick Wall}}</ref> The song "The Hawthorne Passage" from Agalloch's Album ] contains an audio sample from the scene in which Antonious first meets Death. | |||

| ===Opera=== | |||

| Notable parodies of Bergman's Death also occur in: | |||

| In 2016, composer ] premiered in New York City at ] the music for the first act of ''The Seventh Seal'', a work in progress under contract with the Ingmar Bergman Foundation, sung in Swedish. The work was under production by the ] as part of the celebrations for the Ingmar Bergman centenary in 2018.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://cultura.estadao.com.br/noticias/musica,brasileiro-transforma-o-setimo-selo-em-opera,10000087384 |title=Brasileiro transforma 'O Sétimo Selo' em ópera |author=Thiago Mattos e Danielle Villela |publisher=Estadao |date=10 November 2016 |access-date=2 September 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://radarvip.com/maestro-brasileiro-apresenta-opera-em-new-york/ |title=Maestro brasileiro apresenta opera em New York |publisher=Radar VIP |date=10 November 2016 |access-date=2 September 2017}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://tutticlassicos.com.br/compositor-brasileiro-joao-macdowell-apresenta-em-nova-york-sua-opera-o-setimo-selo/ |title=Brasileiro João MacDowell monta em Nova York sua ópera 'O Sétimo Selo' |author=Por Debora Ghivelder |publisher=Tuttie |date=7 November 2016 |access-date=2 September 2017 |archive-date=22 November 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20161122153628/http://tutticlassicos.com.br/compositor-brasileiro-joao-macdowell-apresenta-em-nova-york-sua-opera-o-setimo-selo/ |url-status=dead }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wqxr.org/#!/story/sayao-saudade-brazils-contributions-opera/ |title=From Sayão to Saudade: Brazil's Contributions to Opera |first=Fred |last=Plotkin |publisher=WQXR |date=17 August 2016 |access-date=2 September 2017}}</ref> | |||

| * The trailer to the film '']'', during which the narrator says, "But compared to something like Ingmar Bergman's 'The Seventh Seal', it's all rather silly...", as a mock recreation of ''The Seventh Seal'' occurs, depicting the Knight pondering the chess game, followed by Death ]. Similarly, in Part VII of '']'' entitled ''Death'' Bergman's coming home dinner scene is mirrored, right down to death's entrance. | |||

| * The film '']'', where Death is a major character (played by ]) whom the protagonists beat at ], ], ] and ]. The TV series '']'' has a similar theme, with Death becoming a major character tied to the main characters after they defeat him in a game of limbo. | |||

| * A brief scene in '']'' involves the main character dressed as a knight playing chess with Death. | |||

| * '']'' features a recurring segment, "Cheating Death with Dr. Stephen T. Colbert, D.F.A.", which begins with Colbert playing chess with Death against an ocean backdrop. He manages to distract Death momentarily, switching two pieces around. | |||

| * ]'s '']'' has the protagonist Boris Grushenko (played by Allen) meet Death early in the movie. The movie ends with a scene similar to the final scene in ''The Seventh Seal''. | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] in ]'s '']'' | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist |

{{reflist}} | ||

| ===References=== | |||

| *{{cite book|title=The Seventh Seal| first=Ingmar|last=Bergman|publisher=Touchstone |year=1960}} | |||

| *{{cite book | url= http://books.google.com/books?id=oahZAAAAMAAJ&q=Melvyn+Bragg+(Det+Sjunde+Inseglet)&dq=Melvyn+Bragg+(Det+Sjunde+Inseglet)|authorlink=Melvyn Bragg|last=Bragg|first=Melvyn|title= The Seventh Seal (Det Sjunde Inseglet) |publisher= BFI Publishing | year= 1998|isbn= 978-0851703916}} | |||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| * {{cite book |title=The Seventh Seal |first=Ingmar |last=Bergman |publisher=Touchstone |year=1960}} | |||

| *''Ingmar Bergman and the Rituals of Art'' by Paisley Livingston. Cornell University Press, 1982. | |||

| * {{cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=oahZAAAAMAAJ&q=Melvyn+Bragg+(Det+Sjunde+Inseglet) |author-link=Melvyn Bragg |last=Bragg |first=Melvyn |title=The Seventh Seal (Det Sjunde Inseglet) |publisher=BFI Publishing |year=1998 |isbn=978-0-85170-391-6 }} | |||

| * {{cite book |title=Philosophy Through Film |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bItUHBmB8YIC |chapter=8. THE PROBLEM OF EVIL – ''The Seventh Seal'' (1957) and ''The Rapture'' (1991) <nowiki></nowiki> |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bItUHBmB8YIC&q=%228.+THE+PROBLEM+OF+EVIL+–+The+Seventh+Seal+(1957)+and+The+Rapture+(1991)&pg=188|first=Mary M. |last=Litch |publisher=] |location=London |year=2010 |orig-date=1st ed. 2002 |edition=2nd |isbn=978-0415938754}} | |||

| * {{cite book |chapter=9. EXISTENTIALISM - ''The Seventh Seal'' (1957), ''Crimes and Misdemeanors'' (1988), and ''Leaving Las Vegas'' (1995) <nowiki></nowiki> |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=bItUHBmB8YIC&q=%229.+EXISTENTIALISM+–+The+Seventh+Seal+(1957),+Crimes+and+Misdemeanors+(1988),+and+Leaving+Las+Vegas+(1995)&pg=209 |title=Philosophy Through Film (2nd ed.) |first=Mary M. |last=Litch |year=2010 | publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn = 9780203863329|orig-year=1st ed. 2002}} | |||

| * Livingston, Paisley (1982). ''Ingmar Bergman and the Rituals of Art''. ]. {{ISBN|0-8014-1452-0}} | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{ |

{{Wikiquote}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{IMDb title|0050976}} | ||

| * {{ |

* {{Sfdb title|4522}} | ||

| * {{tcmdb title|id=43870}} | |||

| * | |||

| * an essay by ] at ] | |||

| * {{rotten-tomatoes|id=seventh_seal|title=The Seventh Seal}} | |||

| {{ |

{{Ingmar Bergman}} | ||

| {{Cannes Film Festival Jury Prize}} | |||

| {{s-ach|aw}} | |||

| {{Swedish submission for Academy Awards}} | |||

| {{succession box | |||

| | title=] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| | years=1956<br>tied with ''''']''''' | |||

| | before='']'' | |||

| | after='']''}} | |||

| {{end}} | |||

| {{CinemaofSweden}} | |||

| {{Bergman}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Seventh Seal}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Seventh Seal}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 11:46, 22 December 2024

1957 film by Ingmar Bergman For other uses, see The Seventh Seal (disambiguation).

| The Seventh Seal | |

|---|---|

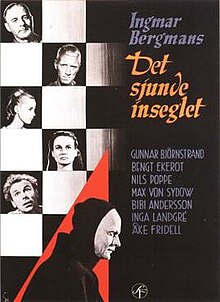

Theatrical release poster Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Screenplay by | Ingmar Bergman |

| Based on | Trämålning by Ingmar Bergman |

| Produced by | Allan Ekelund |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gunnar Fischer |

| Edited by | Lennart Wallén |

| Music by | Erik Nordgren |

| Distributed by | AB Svensk Filmindustri |

| Release date |

|

| Running time | 96 minutes |

| Country | Sweden |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $150,000 |

The Seventh Seal (Swedish: Det sjunde inseglet) is a 1957 Swedish historical fantasy film written and directed by Ingmar Bergman. Set in Sweden during the Black Death, it tells of the journey of a medieval knight (Max von Sydow) and a game of chess he plays with the personification of Death (Bengt Ekerot), who has come to take his life. Bergman developed the film from his own play Wood Painting. The title refers to a passage from the Book of Revelation, used both at the very start of the film and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when the Lamb had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour." Here, the motif of silence refers to the "silence of God," which is a major theme of the film.

The Seventh Seal is considered a classic in the history of cinema, as well as one of the greatest films of all time. It established Bergman as a director, containing scenes which have become iconic through homages, critical analysis, and parodies.

Plot

Disillusioned knight Antonius Block and his cynical squire Jöns return from the Crusades to find the country ravaged by the plague. The knight encounters Death, whom he challenges to a chess match, believing he can survive as long as the game continues.

The knight and his squire pass a caravan of actors: Jof and his wife Mia, with their infant son Mikael and actor-manager Jonas Skat. Waking early, Jof has a vision of Mary leading the infant Jesus, which he relates to a smilingly disbelieving Mia.

Block and Jöns visit a church where a fresco of the Danse Macabre is being painted. The squire chides the artist for colluding in the ideological fervor that led to the crusade. In the confessional, Block tells the priest he wants to perform "one meaningful deed" after what he now sees as a pointless life. Upon revealing to him the chess tactic that will save his life, the knight discovers that it is actually Death with whom he has been speaking. Leaving the church, Block speaks to a young woman condemned to be burned at the stake for consorting with the Devil. He believes she will tell him about life beyond death, only to find that she is insane.

In a deserted village, Jöns saves a mute servant girl from being raped by Raval, a theologian who ten years earlier persuaded the knight to join the Crusades and is now a thief. Jöns vows to destroy his face if they meet again. Jöns kisses the servant girl, who resists his advance. He then tells her to repay her debt by becoming his servant. She reluctantly agrees. The group goes into town, where the actors are performing. There, Skat is enticed away for a tryst by Lisa, wife of the blacksmith Plog. The stage show is interrupted by a procession of flagellants led by a preacher who harangues the townspeople.

At the town's inn, Raval manipulates Plog and other customers into intimidating Jof. The bullying is broken up by Jöns, who slashes Raval's face. The knight and squire are joined by Jof's family and a repentant Plog. Block enjoys a picnic of milk and wild strawberries that Mia has gathered and promises to remember that evening for the rest of his life.

He then invites Plog and the actors to shelter from the plague in his castle. When they encounter Skat and Lisa in the forest, she returns to Plog, while Skat fakes a remorseful suicide. As the group moves on, Skat climbs a tree to spend the night, but Death appears beneath and cuts down the tree.

Meeting the condemned woman being drawn to execution, Block asks her to summon Satan so he can question him about God. The girl claims she has done so, but the knight only sees her terror and gives her herbs to take away her pain as she is placed on the pyre.

They encounter Raval, stricken by the plague. Jöns stops the servant girl from uselessly bringing him water, and Raval dies alone. Jof then sees the knight playing chess with Death and decides to flee with his family, while Block knowingly keeps Death occupied.

As Death states "No one escapes me", Block knocks the chess pieces over but Death restores them to their place. On the next move, Death wins the game and announces that when they meet again, it will be the last time for all. Death then asks Block if he achieved the "meaningful deed" he wished to accomplish. The knight replies that he has.

Block is reunited with his wife and the party shares a final supper, interrupted by Death's arrival. The other members of the party then introduce themselves, and the mute servant girl greets him with "It is finished."

Jof and his family have sheltered in their caravan from a storm, which he interprets as the Angel of Death passing by. In the morning, Jof sees a vision of the knight and his companions being led away over the hillside in a Dance of Death.

Cast

- Gunnar Björnstrand – Jöns, squire

- Bengt Ekerot – Death

- Nils Poppe – Jof

- Max von Sydow – Antonius Block, knight

- Bibi Andersson – Mia

- Inga Landgré – Karin

- Åke Fridell – Blacksmith Plog

- Inga Gill – Lisa

- Erik Strandmark – Jonas Skat

- Bertil Anderberg – Raval, the thief

- Gunnel Lindblom – Mute girl

- Maud Hansson – Witch

- Gunnar Olsson – church painter

- Anders Ek – The Monk

- Benkt-Åke Benktsson – Merchant

- Gudrun Brost – Maid

- Lars Lind – Young monk

- Tor Borong – Farmer

- Harry Asklund – Inn keeper

- Ulf Johanson – Jack's leader (uncredited)

Themes

The title refers to a passage about the end of the world from the Book of Revelation, used both at the very start of the film, and again towards the end, beginning with the words "And when the Lamb had opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven about the space of half an hour" (Revelation 8:1). Thus, in the confessional scene the knight states: "Is it so cruelly inconceivable to grasp God with the senses? Why should He hide himself in a mist of half-spoken promises and unseen miracles?...What is going to happen to those of us who want to believe but aren't able to?" Death, impersonating the confessional priest, refuses to reply. Similarly, later, as he eats the strawberries with the family of actors, Antonius Block states: "Faith is a torment – did you know that? It is like loving someone who is out there in the darkness but never appears, no matter how loudly you call." Melvyn Bragg notes that the concept of the "Silence of God" in the face of evil, or the pleas of believers or would-be-believers, may be influenced by the punishments of silence meted out by Bergman's father, a chaplain in the State Lutheran Church. In Bergman's original radio play sometimes translated as A Painting on Wood, the figure of Death in a Dance of Death is represented not by an actor, but by silence, "mere nothingness, mere absence...terrifying...the void."

Some of the powerful influences on the film were Picasso's picture of the two acrobats, Carl Orff's Carmina Burana, Strindberg's dramas Folkungasagan ("The Saga of the Folkung Kings") and The Road to Damascus, the frescoes at Härkeberga church, and a painting by Albertus Pictor in Täby church. Just prior to shooting, Bergman directed for radio the play Everyman by Hugo von Hofmannsthal. By this time he had also directed plays by Shakespeare, Strindberg, Camus, Chesterton, Anouilh, Tennessee Williams, Pirandello, Lehár, Molière and Ostrovsky. The actors Bibi Andersson (with whom Bergman was in a relationship from 1955 to 1959) who played the juggler's wife Mia, and Max von Sydow, whose role as the knight was the first of many star parts he would bring to Bergman's films and whose rugged Nordic dignity became a vital resource within Bergman's "troupe" of key actors, both made a strong impact on the mood and style of the film.

Bergman grew up in a home infused with an intense Christianity, his father being a charismatic rector (this may have explained Bergman's adolescent infatuation with Hitler, which later deeply tormented him). As a six-year-old child, Bergman used to help the gardener carry corpses from the Royal Hospital Sophiahemmet (where his father was chaplain) to the mortuary. When as a boy he saw the film Black Beauty, the fire scene excited him so much he stayed in bed for three days with a temperature. Despite living a Bohemian lifestyle in partial rebellion against his upbringing, Bergman often signed his scripts with the initials "S.D.G" (Soli Deo Gloria) — "To God Alone the Glory" — just as J. S. Bach did at the end of every musical composition.

Gerald Mast writes:

"Like the gravedigger in Hamlet, the Squire treats death as a bitter and hopeless joke. Since we all play chess with death, and since we all must suffer through that hopeless joke, the only question about the game is how long it will last and how well we will play it. To play it well, to live, is to love and not to hate the body and the mortal as the Church urges in Bergman's metaphor."

Melvyn Bragg writes:

"t is constructed like an argument. It is a story told as a sermon might be delivered: an allegory...each scene is at once so simple and so charged and layered that it catches us again and again...Somehow all of Bergman's own past, that of his father, that of his reading and doing and seeing, that of his Swedish culture, of his political burning and religious melancholy, poured into a series of pictures which carry that swell of contributions and contradictions so effortlessly that you could tell the story to a child, publish it as a storybook of photographs and yet know that the deepest questions of religion and the most mysterious revelation of simply being alive are both addressed."

The Jesuit publication America identifies it as having begun "a series of seven films that explored the possibility of faith in a post-Holocaust, nuclear age". Likewise, film historians Thomas W. Bohn and Richard L. Stromgren identify this film as beginning "his cycle of films dealing with the conundrum of religious faith".

Portrait of the Middle Ages

Medieval Sweden as portrayed in this movie includes creative anachronisms. The flagellant movement was foreign to Sweden, and large-scale witch persecutions only began in the 15th century. In addition, the main period of the Crusades is well before this era; they took place in a more optimistic period.

With regard to the relevancy of historical accuracy to a film that is heavily metaphorical and allegorical, John Aberth, writing in A Knight at the Movies, holds

the film only partially succeeds in conveying the period atmosphere and thought world of the fourteenth century. Bergman would probably counter that it was never his intention to make an historical or period film. As it was written in a program note that accompanied the movie's premier "It is a modern poem presented with medieval material that has been very freely handled... The script in particular—embodies a mid-twentieth century existentialist angst... Still, to be fair to Bergman, one must allow him his artistic license, and the script's modernisms may be justified as giving the movie's medieval theme a compelling and urgent contemporary relevance... Yet the film succeeds to a large degree because it is set in the Middle Ages, a time that can seem both very remote and very immediate to us living in the modern world... Ultimately The Seventh Seal should be judged as a historical film by how well it combines the medieval and the modern."

Similarly defending it as an allegory, Aleksander Kwiatkowski in the book Swedish Film Classics, writes

The international response to the film which among other awards won the jury's special prize at Cannes in 1957 reconfirmed the author's high rank and proved that The Seventh Seal regardless of its degree of accuracy in reproducing medieval scenery may be considered as a universal, timeless allegory.