| Revision as of 23:28, 5 September 2010 editExplicit (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Administrators326,661 editsm Removed Category:Victims of aviation accidents or incidents (using HotCat)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:20, 31 December 2024 edit undoSjones23 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers102,184 editsm →Death: Minor rewrite.Tag: 2017 wikitext editor | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American country music singer (1932–1963)}} | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=July 2010}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=March 2021}} | |||

| {{Infobox musical artist <!-- See Misplaced Pages:WikiProject Musicians --> | |||

| {{good article}} | |||

| | Name = Patsy Cline | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| | Img = Patsy Cline-WSM Studios 2.jpg | |||

| | |

| name = Patsy Cline | ||

| | |

| image = Patsy Cline 1960 publicity portrait - cropped.jpg | ||

| | |

| caption = Cline in 1960 | ||

| | |

| birth_name = Virginia Patterson Hensley | ||

| | birth_date = {{Birth date|1932|9|08|mf=y}} | |||

| |Alias = Ginny, Patsy | |||

| | birth_place = ], U.S. | |||

| | Born = {{birth date|1932|9|8|mf=y}} | |||

| | |

| death_date = {{death date and age|1963|03|5|1932|09|08}} | ||

| | |

| death_place = near ], U.S. | ||

| | |

| death_cause = ] | ||

| | resting_place = Shenandoah Memorial Park, Winchester, Virginia, U.S. | |||

| | Genre = ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | |

| occupation = {{flatlist| | ||

| * Singer | |||

| | Years_active = 1955–1963 | |||

| * songwriter | |||

| | Label = ] <small> (1955-1960) </small> <br> ] <small> (1960-1963) </small> | |||

| * pianist | |||

| | Associated_acts = ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| * composer | |||

| }} | |||

| | years_active = 1948–1963 | |||

| | spouse = {{ubl|{{marriage|Gerald Cline|1953|1957|reason=divorced}}|{{marriage|]|1957}}}} | |||

| | children = 2 | |||

| | module = {{Infobox musical artist | |||

| | embed = yes | |||

| | background = solo_singer | |||

| | instrument = {{hlist|Vocals|piano}} | |||

| | discography = {{hlist|]|]|]}} | |||

| | genre = {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * {{nowrap|]<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.allmusic.com/subgenre/nashville-sound-countrypolitan-ma0000002739 | title= Nashville Sound / Countrypolitan | work=] | access-date=July 8, 2017}}</ref>}} | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.mysanantonio.com/lifestyle/travel-outdoors/article/Patsy-Cline-Museum-and-the-wonderful-women-of-12904176.php|title=Patsy Cline Museum and the wonderful women of Music City give you more reasons to be crazy over Nashville|author=Soslow, Robin|newspaper=Mysa |publisher=My San Antonio.com|date=May 10, 2018|access-date=August 11, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| * ]<ref>{{cite web|url=https://greenvillejournal.com/2019/07/23/rockabilly-heaven-mixes-rock-country-into-legendary-music-experience/|title='Rockabilly Heaven' mixes rock, country into legendary music experience|author=Cuenca, Melody|date=July 23, 2019|access-date=July 30, 2019|newspaper=Greenville Journal}}</ref> | |||

| * {{nowrap|]<ref>{{cite web| url=http://www.popmatters.com/feature/sweet-dreams-the-world-of-patsy-cline/ | title=Sweet Dreams: The World of Patsy Cline | work=] | last= Hofstra | first=Warren E. | date=September 20, 2013 | access-date=July 8, 2017}}</ref>}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | label = {{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }} | |||

| | website = {{URL|patsymuseum.com}}{{URL|https://wilkesheritagemuseum.com/hall-of-fame/previous-years/patsy-cline}} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Patsy Cline''' (September 8, 1932 |

'''Patsy Cline''' (born '''Virginia Patterson Hensley'''; September 8, 1932 – March 5, 1963) was an American singer, songwriter and pianist. She is regarded as one of the most influential vocalists of the 20th century and was one of the first ] artists to ] into ].<ref>CBS News (February 18, 2009). | ||

| . Retrieved January 16, 2012.</ref><ref>Browne, Ray; Browne, Pat (eds.) (2001). ''The Guide to United States Popular Culture''. Popular Press. p. 180. {{ISBN|978-0-87972-821-2}}.</ref> Cline had several major hits during her eight-year recording career, including two number-one hits on the '']'' ] chart. | |||

| Born in ], Cline's first professional performances began in 1948 at local radio station ] when she was 15. In the early 1950s, Cline began appearing in a local band led by performer Bill Peer. Various local appearances led to featured performances on ]'s ''Town and Country'' television broadcasts. She signed her first recording contract with the ] label in 1954, and had minor success with her earliest Four Star singles including "]" (1955) and "I've Loved and Lost Again" (1956). In 1957 Cline made her first national television appearance on '']''. After performing "]", the single became her first major hit on both the country and pop charts. | |||

| Cline was best known for her rich tone and emotionally expressive bold ] voice,<ref name="Time article on Patsy Cline"></ref> which, along with her role as a mover and shaker in the country music industry, has been cited as an inspiration by many vocalists of various music genres. Her life and career have been the subject of numerous books, movies, documentaries, articles and stage plays. | |||

| Cline's further singles with Four Star Records were unsuccessful, although she continued performing and recording. In 1958, she relocated to ], to further her career. Working with new manager Randy Hughes, Cline became a member of the ] and then moved to ] in 1960. Under the direction of producer ], her musical sound shifted and she achieved consistent success. The 1961 single "]" became her first to top the ''Billboard'' country chart. After Cline was severely injured in an automobile accident, which caused her to spend a month in the hospital. After she recovered, her next single "]" also became a major hit. | |||

| Her hits included "]", "]", "]", "]" and "]". Posthumously, millions of her albums have sold over the past 50 years and she has been given numerous awards, which have given her an iconic status with some fans similar to that of legends ] and ]. Ten years after her death, she became the first female solo artist inducted to the ]. | |||

| During 1962 and 1963, Cline had hits with "]", "]", "]" and "]". She also toured and headlined shows with more frequency. On March 5, 1963, she was killed unexpectedly in ] along with country musicians ], ], and manager Randy Hughes, during a flight from ], back to Nashville. | |||

| In 2002, Cline was voted by artists and members of the country music industry as number one on CMT's television special, '']'', and in 1999 she was voted number 11 on VH1's special '']'' by members and artists of the rock industry. She was also ranked 46th in ''Rolling Stone'''s "100 Greatest Singers of all Time." According to her 1973 Country Music Hall of Fame plaque, "Her heritage of timeless recordings is testimony to her artistic capacity." | |||

| Since her death, Cline has been cited as one of the most celebrated, respected, and influential performers of the 20th century. Her music has influenced performers of various styles and genres.<ref name="CNN">{{cite news | last= Duke | first= Alan| url= http://edition.cnn.com/2012/07/17/showbiz/kitty-wells-legacy |title=Kitty Wells blazed country path for women |work=CNN|date=July 18, 2012 |access-date=March 6, 2013}}</ref> She has also been seen as a forerunner for women in country music, being among the first to sell records and headline concerts. In 1973, she became the first female performer to be inducted into the ]. In the 1980s, Cline's posthumous successes continued in the mass media. She was portrayed twice in major motion pictures, including the 1985 biopic '']'' starring ]. Several documentaries and stage shows about her have been made, including the 1988 musical ''Always...Patsy Cline''. A 1991 box set of her recordings received critical acclaim. Her ] sold over 10 million copies in 2005. In 2011, Cline's ] in ] was restored as a museum for visitors and fans to tour. | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| ===Childhood=== | |||

| Born September 8, 1932, in ], she was the daughter of Sam and Hilda Patterson Hensley, a blacksmith and a seamstress; Hilda was only 16 when Patsy was born. Patsy was the eldest of three children, the others being Samuel and Sylvia. The three children, despite their given names, were called Ginny, John, and Sis. Patsy grew up a poor girl "on the wrong side of the tracks," but except for the fact that her father deserted the family in 1947, when she was 15, the Hensley home was quite happy.<ref></ref> | |||

| ==Early life== | |||

| The family lived in many different places around ] before settling in Winchester. Cline often said as a child that she would one day be famous, and admired stars such as ] and ]. A serious illness as a child caused a throat infection which, according to Cline, resulted in her gift of "a voice that boomed like ]'s." Well-rounded in her musical tastes, Cline cited everyone from ] to ] as influences. As a child, she often sang in church with her mother. Cline was also a by-ear pianist who sang with ]. | |||

| ] on South Kent Street in Winchester, Virginia where she lived from age 16 to 21.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1985/09/29/sweet-dreams/7eb27412-edbb-42fd-b117-7c3c5dd15655/|title=Washington Post Washington, DC, Sweet Dreams Article|last=McGhee|first=Dorothy|date=September 29, 1985|website=ICPSR Data Holdings|access-date=March 9, 2019}}</ref>]] | |||

| Virginia Patterson Hensley was born in ], on September 8, 1932, to Hilda Virginia (née Patterson) and Samuel Lawrence Hensley.<ref name="The Post">{{cite news |last1=Pae |first1=Peter |title=CRAZY OVER CLINE |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1995/08/27/crazy-over-cline/e12f009d-80bf-49cf-a062-402184101f8e/ |access-date=August 15, 2019 |newspaper=]}}</ref><ref name="Celebrating Patsy Cline">{{cite web |title=About Patsy |url=https://celebratingpatsycline.org/about-patsy/ |website=Celebrating Patsy Cline.org |access-date=August 15, 2019 |archive-date=August 15, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190815221635/https://celebratingpatsycline.org/about-patsy/ |url-status=dead }}</ref> Mrs. Hensley was only 16 years old at the time of Cline's birth. Sam Hensley had been married before; Cline had two half siblings (aged 12 and 15) who lived with a foster family because of their mother's death years before. After Cline, Hilda Hensley gave birth to Samuel Jr. (called John) and Sylvia Mae.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=7}}<ref>{{cite web |title=Daughter of a Single Mom, Singer Patsy Cline Is Still Loved |url=https://esme.com/single-moms/sons-daughters/daughter-single-mom-singer-patsy-cline-still-loved |website=Esme |date=May 7, 2018 |access-date=September 16, 2019}}</ref> Besides being called "Virginia" in her childhood, Cline was referred to as "Ginny".<ref>{{cite web |last1=Sawyer |first1=Bobbie Jean |title=10 Things You Didn't Know About Patsy Cline |url=https://www.wideopencountry.com/patsy-cline-things-you-didnt-know/ |website=Wide Open Country |access-date=September 16, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| She temporarily lived with her mother's family in ], before relocating many times throughout the state. In her childhood, the family relocated where Samuel Hensley, a blacksmith, could find employment, including ], ], and ]. When the family had little money, she would find work, including at an Elkton poultry factory, where her job was to pluck and cut chickens.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=8}} The family moved often before finally settling in ], on South Kent Street.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1985/09/29/sweet-dreams/7eb27412-edbb-42fd-b117-7c3c5dd15655/|title=Sweet Dreams|last=McGhee|first=Dorothy|date=September 29, 1985|newspaper=Washington Post}}</ref> Cline would later report that her father sexually abused her.<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame">{{cite web |title=Patsy Cline – Country Music Hall of Fame |url=https://countrymusichalloffame.org/artist/patsy-cline/ |website=] |access-date=August 15, 2019}}</ref> When confiding the abuse to friend ], Cline told her, "take this to your grave." Hilda Hensley would later report details of the abuse to producers of Cline's 1985 biopic '']''.<ref name="Encyclopedia">{{cite web |title=Cline, Patsy (1932–1963) |url=https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/cline-patsy-1932-1963 |website=] |access-date=August 15, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ===Teen years=== | |||

| At age 13, Cline was hospitalized with a throat infection and ]. Speaking of the incident in 1957 she said, "I developed a terrible throat infection and my heart even stopped beating. The doctor put me in an oxygen tent. You might say it was my return to the living after several days that launched me as a singer. The fever affected my throat and when I recovered I had this booming voice like ]'s."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=9}}<ref name="U Discover">{{cite web |last1=U Discover Staff |title=50 Facts About Patsy Cline |url=https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/50-facts-about-patsy-cline/ |website=U Discover |access-date=August 16, 2019}}</ref> It was during this time she developed an interest in singing. She started performing with her mother in the local Baptist choir. Mother and daughter also performed duets at church social events.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=9}} She also taught herself how to play the ].<ref name="Biography">{{cite web |title=Patsy Cline – Singer, Pianist |url=https://www.biography.com/musician/patsy-cline |website=] |access-date=August 16, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Cline began performing in variety-talent showcases in and around Winchester. She asked ] disc jockey Jimmy McCoy if he would let her sing on his show, which he did. His program was a showcase for local talent. | |||

| With the new performing opportunities, Cline's interest in singing grew, and at the age of 14, she told her mother that she was going to audition for the local radio station. Her first radio performances were at ] in the Winchester area. According to WINC's radio disc jockey Joltin' Jim McCoy, Cline appeared in the station's waiting room one day and asked to audition. McCoy was impressed by her audition performance, reportedly saying, "Well, if you've got nerve enough to stand before that mic and sing over the air live, I've got nerve enough to let you."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=10}} While performing on the radio, Cline also started appearing in talent contests and created a nightclub cabaret act similar to performer ].<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> | |||

| To help support her family after her father abandoned them, she dropped out of ] and worked various jobs, ]ing and waitressing by day at The Triangle Diner<ref>http://www.TriangleDiner.com</ref> across the street from her school, ]. At night, Cline could be found singing at local nightclubs, wearing fringed Western stage outfits that she designed and that her mother made. | |||

| Cline's parents had marital conflicts during her childhood and by 1947 her father had deserted the family. Author Ellis Nassour of the biography ''Honky Tonk Angel: An Intimate Story of Patsy Cline'' reported Cline had a "beautiful relationship" with her mother. In his interviews with Hilda Hensley, he quoted Cline's mother as saying they "were more like sisters" than parent and child.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=11}} Cline attended the ninth grade at ] in Winchester, Virginia.<ref name="Encyclopedia"/> However, the family had trouble sustaining an income after her father's desertion, and Cline dropped out of high school to help support the family. She began working at Gaunt's Drug Store in the Winchester area as a clerk and ].{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=11}} | |||

| ===First marriage and first recording=== | |||

| ==Career== | |||

| In her early 20s, Cline met two men who would influence her rise to stardom. The first was contractor Gerald Cline, whom she married in 1953 and divorced in 1957. The dissolution of the marriage was blamed not only on a considerable age difference, but also Patsy Cline's desire to sing professionally and Gerald Cline's lack of support of her quest for stardom. While she dreamed of a career as a superstar, he wanted her to conform to the role of a housewife first. The second was Bill Peer, her new manager, who gave her the name Patsy, from her middle name and her mother's maiden name, Patterson. | |||

| ===1948–1953: Early career=== | |||

| At age 15, Cline wrote a letter to the ] asking for an audition. She told local photographer Ralph Grubbs about the letter, "A friend thinks I'm crazy to send it. What do you think?" Grubbs encouraged Cline to send it. Several weeks later, she received a return letter from the Opry asking for pictures and recordings.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=12}} At the same time, ] performer ] headlined a concert in her hometown. Cline convinced concert employees to let her backstage where she asked Fowler for an audition.{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=216}} Following a successful audition, Cline's family received a call asking for her to audition for the Opry. She traveled with her mother, two siblings, and a family friend on an eight-hour journey to ]. With limited finances, they drove overnight and slept in a Nashville park the following morning. Cline auditioned for Opry performer ] the same day. The audition was well-received and Cline expected to hear from the Opry the same day. However, she never received news and the family returned to Virginia.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=13–17}} | |||

| By the early 1950s, Cline continued performing around the local area. In 1952, she asked to audition for local country bandleader Bill Peer. Following her audition, she began performing regularly as a member of Bill Peer's Melody Boys and Girls.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=10}}{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=216}} The pair's relationship turned romantic, continuing an affair for several years. Nonetheless, the pair remained married to their spouses.{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=216}}{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=21}} Peer's group played primarily at the ] in ] where she would meet her first husband, Gerald Cline. Peer encouraged her to have a more appropriate stage name. She changed her first name from Virginia to Patsy (taken from her middle name "Patterson"). She kept her new last name, Cline. Ultimately, she became professionally known as "Patsy Cline".<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/><ref name="Encyclopedia"/> | |||

| Cline's numerous appearances on local radio attracted a large following in the Virginia-Maryland area—especially when ] learned of her. In 1954 she became a regular on ]'s ''Town and Country'' afternoon radio show on ] in ], which also featured Dean, himself a young country star. | |||

| In August 1953, Cline was a contestant in a local country music contest. She won 100 dollars and the opportunity to perform as a regular on ]'s ''Town and Country Time''.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=20}} The show included country stars ], ], ] and ],<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> and was filmed in ] and ]. She was not officially added to the program's television shows until October 1955.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=46}} Cline's television performances received critical acclaim. '']'' magazine praised her stage presence, commenting, "She creates the moods through movement of her hands and body and by the lilt of her voice, reaching way down deep in her soul to bring forth the melody. Most female country music vocalists stand motionless, sing with monotonous high-pitched nasal twang. Patsy's come up with a throaty style loaded with motion and E-motion."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=52}} | |||

| In 1955, Cline was signed to ]. Her contract, however, only allowed her to record compositions by Four Star writers; Cline disliked this, and later expressed regret over signing with the label. Her first record for Four Star was "A Church, A Courtroom & Then Good-Bye", which attracted little attention, although it did lead to several appearances on the ]. Between 1955 and 1957, Cline also recorded ] material, with songs like "Fingerprints", "Pick Me Up On Your Way Down", "Don't Ever Leave Me Again", and "A Stranger In My Arms"; the latter two both co-written by Cline, and she experimented with rockabilly. None of these songs, however, gained any notable success. | |||

| ===1954–1960: Four Star Records=== | |||

| According to ], her ] producer, the Four Star compositions only seemed to hint at the potential that lurked inside of Cline. Bradley thought her voice was best suited for singing ]. The Four Star producers, however, insisted that Cline would record only country songs, as her contract also stated. During her contract with Four Star, she recorded 51 songs. | |||

| In 1954, Bill Peer created and distributed a series of demonstration tapes with Cline's voice on it. A tape was brought to the attention of Bill McCall, president of ].{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=30}} On September 30, 1954, she signed a two-year recording contract with the label alongside Peer and her husband Gerald Cline.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Thompson |first1=Gayle |title=Country Music Memories: Patsy Cline Signs First Recording Contract |url=https://theboot.com/patsy-cline-first-recording-contract/ |website=The Boot |access-date=August 18, 2019}}</ref> The original contract allowed Four Star to receive most of the money for the songs she recorded.<ref name="NPR">{{cite web |last1=Ward |first1=Ed |title=Patsy Cline: A Country Career Cut Short |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=129526320 |website=] |access-date=August 18, 2019}}</ref> Therefore, Cline received little of the royalties from the label, totaling out to 2.34 percent on her recording contract.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=32}}<ref name="Encyclopedia"/> Her first recording session took place in ] on January 5, 1955. Songs for the session were handpicked by McCall and ]. Four Star leased the recordings to the larger ]. For those reasons ] was chosen as the session's ], a professional relationship that would continue into the 1960s.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=33}} Her first single release was 1955's "]". Although Cline promoted it with an appearance on the ], the song was not successful.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=38–42}}<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> | |||

| {{Listen | |||

| | filename = Patsy Cline--Walkin After Midnight Audio.ogg | |||

| | title = "Walkin' After Midnight" | |||

| | description = Cline's first major hit as a recording artist, released in 1957 on Decca Records. | |||

| }} | |||

| Cline recorded a variety of musical styles while recording for Four Star. This included genres such as ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|pp=302–303}}{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=216}} Writers and music journalists have had mixed responses on Cline's Four Star material. Robert Oermann and Mary Bufwack of ''Finding Her Voice: Women in Country Music'' called the label's choice of material "mediocre". They also commented that Cline seemed to have "groped for her own sound on the label".{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=216}} Kurt Wolff of ''Country Music the Rough Guide'' commented that the music was "sturdy enough, but they only hinted at the potential that lurked inside her.{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|p=303}} Richie Unterberger of '']'' claimed it was Cline's voice that made the Four Star material less appealing: "Circumstances were not wholly to blame for Cline's commercial failures. She would have never made it as a rockabilly singer, lacking the conviction of ] or the spunk of ]. In fact, in comparison with her best work, she sounds rather stiff and ill-at-ease on most of her early singles."<ref name="Allmusic Bio">{{cite web |last1=Unterberger |first1=Richie |title=Patsy Cline: Biography & History |url=https://www.allmusic.com/artist/patsy-cline-mn0000014651/biography |website=] |access-date=August 18, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ===National fame and "Walkin' After Midnight"=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Between 1955 and 1956, Cline's four singles for Four Star failed to become hits. However, she continued performing regionally, including on the ''Town and Country Jamboree''.<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> In 1956, she appeared on ABC's Country Music Jubilee, '']''.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1994|p={{page needed|date=September 2022}}}} It was at one of her local performances that she met her second husband, ].{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=52–57}} In 1956, Cline received a call to perform on '']'', a national television show she had auditioned for several months prior. She accepted the offer, using her mother Hilda Hensley as her ] for the show.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=66–67}} According to the show's rules, talent scouts could not be family members. For those reasons, Cline's mother lied in order to appear on the show. When ] asked if Hensley had known Cline her entire life, she replied, "Yes, just about!"<ref name="10 Things">{{cite magazine |last1=Betts |first1=Stephen L. |title=10 Things We Learned From the New Patsy Cline Documentary |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-country/10-things-we-learned-from-the-new-patsy-cline-documentary-126274/ |magazine=] |date=March 3, 2017 |access-date=August 19, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Cline made her network television debut on January 7, 1956 on ]'s ''Grand Ole Opry'';<ref>{{citation|first=Ellis|last=Nassour|title=Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline|publisher=St. Martin's Paperbacks; Expanded edition|year=1994|isbn=0312951582}}, p. 80</ref> followed by an appearance on the network's '']'' later that month,<ref>{{citation|first=Ellis|last=Nassour|title=Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline|publisher=St. Martin's Paperbacks; Expanded edition|year=1994|isbn=0312951582}}, p. 80 Cline referred to a January 1956 ''Ozark Jubilee'' appearance in a letter but did not give the date.</ref> returning to the show in April. Later that year, while looking for material for her first album, ''Patsy Cline'', a song appeared titled "]", written by Don Hecht and Alan Block. Cline initially did not like the song because it was, according to her, "just a little old pop song." However, the song's writers and record label insisted she should record it. | |||

| Cline and Hensley flew into New York City's ] on January 18, 1957. She made her debut appearance on the program on January 21.<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/><ref name = smithsonian1>''Mother Country'' by Amanda Petrusich Smithsonian magazine April–May 2022 edition Pages 32-34</ref> The day of the show, she met with the show's producer ]. Cline had chosen "]" to perform on the program, but Davis preferred another song she had recorded, "]". Cline initially refused to perform it, but ultimately agreed to it.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=71–73}} Davis also suggested Cline wear a cocktail dress instead of the cowgirl outfit created by her mother.<ref name="10 Things"/> She performed "Walkin' After Midnight" and won the program's contest that night.<ref name = smithsonian1/> The song had not yet been released as a single. In order to keep up with public demand, Decca Records rush-released the song as a single on February 11.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=74–80}} The song ultimately became Cline's breakthrough hit, peaking at number 2 on the '']'' ] chart. The song also reached number 12 on the ].<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> The song has since been considered a classic in ] since its release.<ref name="Allmusic Bio"/> | |||

| She auditioned for '']'' in ], and was accepted to sing on the ] show on January 21, 1957. Godfrey's "discovery" of Cline was typical. Her scout, actually her mother, presented Patsy who initially was supposed to sing "]", but the show's producers insisted she instead sing her recent release, "Walkin' After Midnight". Though heralded as a country song, recorded in Nashville, Godfrey's staff insisted Cline not wear one of her mother's hand-crafted cowgirl outfits but appear in a cocktail dress. | |||

| Music critics and writers have positively praised "Walkin' After Midnight". Mary Bufwack and Robert Oermann called the song "bluesy".{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=216}} Richie Unterberger noted "it's well-suited for the almost bemused aura of loneliness of the lyric."<ref>{{cite web |last1=Unterberger |first1=Richie |title="Walkin' After Midnight": Patsy Cline: Song Info |url=https://www.allmusic.com/song/walkin-after-midnight-mt0050772759 |website=] |access-date=August 19, 2019}}</ref> The success of "Walkin' After Midnight" brought Cline numerous appearances on shows and major networks. She continued working for ] over the next several months. She also appeared on the ] in February and the television program ''Western Ranch Party'' in March.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=80–81}} The money she had earned from her numerous engagements totaled out to ten thousand dollars. Cline gave all the money to her mother, which she used to the pay the mortgage on her Winchester house.<ref name="10 Things"/> In August 1957, her ] was released on Decca Records.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=251}} | |||

| The audience's enthusiastic ovations stopped the meter at its apex, and she won the competition and was invited to return. The song was so well-received that she released it as a single. In short, although Cline had been performing for almost a decade and had appeared nationally three times on ABC-TV, Godfrey was largely responsible for making her a star. For a couple of months thereafter, Cline appeared regularly on Godfrey's radio program. | |||

| Cline's follow-up singles to "Walkin' After Midnight" did not yield any success.<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> This was partially due to the quality of material chosen for her to record.<ref>{{cite web |title=Patsy Cline's aching voice blazed country music trail |url=https://www.greenbaypressgazette.com/story/news/local/door-county/entertainment/2014/10/14/patsy-clines-aching-voice-blazed-country-music-trail/17055635/ |website=Green Bay Press Gazette |access-date=August 19, 2019}}</ref> Cline was dissatisfied with the limited success following "Walkin' After Midnight". Bradley recounted how she often came to him saying, "Hoss, can't you do something? I feel like a prisoner."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=71–73}} Around the same time, Cline was fired from her regular slot on ''Town and Country Jamboree''. According to Connie B. Gay, she ran late for shows and "showed up with liquor on her breath."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=83}} In September 1957, Cline married Charlie Dick and he was soon sent to ] on a military assignment.<ref name="Encyclopedia Virginia">{{cite web |last1=Gomery |first1=Douglas |title=Patsy Cline (1932–1963) |url=https://www.encyclopediavirginia.org/Cline_Patsy_1932-1963 |website=Encyclopedia Virginia |access-date=August 19, 2019}}</ref> Cline also gave birth to her first daughter Julie. In hopes of restarting her career, Cline and her family moved to ].<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> | |||

| "Walkin' After Midnight" reached No. 2 on the country chart and No. 12 on the pop chart, making Cline one of the first country singers to have a ] pop hit. She rode high on the hit for the next year, making personal appearances and performing regularly on both Godfrey’s show, and for several years on ''Ozark Jubilee'' (later ''Jubilee USA''). She could not follow it up with another hit, however, in part because of the deal with Four Star that limited her to recording songs only from its writers.<ref></ref> | |||

| ===1960–1961: New beginnings and car accident=== | |||

| Cline co-wrote two songs, both in 1957 under her birth name, Virginia Hensley: | |||

| ]'' advertisement, May 22, 1961]] | |||

| Cline's professional decisions yielded more positive results by the early 1960s. Upon moving to Nashville, she signed a management deal with Randy Hughes.<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> She originally wished to work with Hubert Long, however, he was busy managing other artists. Instead, she turned her attention to Hughes.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=71–73}} With the help of Hughes, she began working steadier jobs. He organized fifty dollar bookings and got her multiple performances on the ].<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> In January 1960, Cline officially became a member of the Opry.<ref name="Encyclopedia Virginia"/> When she asked general manager Ott Devine about a membership he replied, "Patsy, if that's all you want, you're on the Opry."<ref>{{cite web |title=1960s: Grand Ole Opry |url=https://www.opry.com/content/1960s |website=] |access-date=August 21, 2019 |archive-date=August 21, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190821021844/https://www.opry.com/content/1960s |url-status=dead }}</ref> Also in January 1960, Cline made her final recording sessions set forth in her contract with Four Star Records. Later that year, her final singles with the label were released: "]" and "]". Leaving Four Star, Cline officially signed with Decca Records in late 1960, working exclusively under Bradley's direction.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=119–120}} Insisting on receiving an advance, she received $1,000 from Bradley once she began at the label.<ref name="Encyclopedia"/> | |||

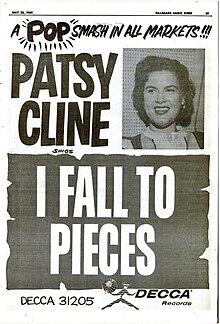

| Her first release on Decca was 1961's "]".{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|p=303}} The song was written by newly established Nashville songwriters ] and ]. "I Fall to Pieces" had first been turned down by ] and ] before Cline cut it in November 1960. At the recording session, she worried about the song's production, particularly the background vocals performed by ].<ref name="I Fall to Pieces">{{cite magazine |last1=Betts |first1=Stephen L. |title=Flashback: Patsy Cline's 'I Fall to Pieces' Hits Number One |url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-country/flashback-patsy-clines-i-fall-to-pieces-hits-number-one-34935/ |magazine=] |date=August 10, 2015 |access-date=August 21, 2019}}</ref> After much arguing between both Cline and Bradley, they negotiated that she would record "I Fall to Pieces" (a song Bradley favored) and "Lovin' in Vain" (a song she favored).{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|pp=133–134}} Released as a single in January 1961, "I Fall to Pieces" attracted little attention upon its initial issue. In April, the song debuted on the Hot Country and Western Sides chart. By August 7, the song became her first to top the country chart. Additionally, "I Fall to Pieces" crossed over onto the ], peaking at number 12.<ref name="I Fall to Pieces"/> ''Billboard'' ranked it as the No. 2 song for 1961 in the end of year charts.<ref>]</ref> | |||

| * "A Stranger in My Arms", written with Charlotte White, and Mary Lu Jeans and recorded on April 24, 1957. The song was released as a Decca 45 single (Decca 30406), on August 12, 1957 b/w "Three Cigarettes (In An Ashtray)", and also as a 45 single on the Festival label as Festival SP45-1620. | |||

| ] | |||

| * "Don't Ever Leave Me Again", written with James E. Crawford, Jr., and Lillian N. Claiborne. "Don't Ever Leave Me Again" appeared on the 1957 Decca LP ''Patsy Cline'' and was the title track of a 1991 compilation album released on Laser Light. | |||

| On June 14, 1961, Cline and her brother Sam Hensley Jr. were involved in an automobile accident.<ref name="Car Crash">{{cite web |last1=Whitaker |first1=Sterling |title=Remember the Car Accident That Nearly Ended Patsy Cline's Career |url=https://tasteofcountry.com/patsy-cline-car-crash/ |website=Taste of Country |date=June 14, 2018 |access-date=August 21, 2019}}</ref> Cline had brought her mother, sister and brother to see her new Nashville home the day before. On the day of the accident, Cline and her brother went shopping to buy material for her mother to make clothing. Upon driving home, their car was struck head-on by another vehicle.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=148}} The impact threw her directly into the car windshield, causing extensive facial injuries. Among her injuries, Cline suffered a broken wrist, dislocated hip and a large cut across her forehead, barely missing her eyes. Friend ] heard about the accident via the radio and rushed to the scene, helping to remove pieces of broken glass from Cline's hair.<ref name="Car Crash"/> When first responders arrived, Cline insisted the driver in the other vehicle be treated first.<ref name="Car Crash"/> Two of the three passengers riding in the car that struck Cline died after arriving at the hospital. When she was brought to the hospital, her injuries were life-threatening and she was not expected to live. She underwent surgery and survived. According to her husband Charlie Dick, upon waking up she said to him, "Jesus was here, Charlie. Don't worry. He took my hand and told me, 'No, not now. I have other things for you to do.'" She spent a month recovering in the hospital.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=148–158}} | |||

| ===1961–1963: Career peak=== | |||

| Also in 1957, she met Charlie Dick, a good-looking ladies' man who frequented the local club circuit Cline played on weekends. His charismatic personality and admiration of Cline's talents captured her attention. Their relationship resulted in a marriage that would last the rest of her life. Though their love affair has long been publicized as controversial, Cline regarded him as "the love of her life." After the birth of their daughter, Julie, in 1958, they moved to ]. | |||

| Cline returned to her career six weeks after her 1961 car accident. Her first public appearance was on the Grand Ole Opry where she assured fans she would continue performing.<ref name="Car Crash"/> She said to the audience that night, "You're wonderful. I'll tell you one thing: the greatest gift, I think, that you folks coulda given me was the encouragement that you gave me. Right at the very time I needed you the most, you came through with the flying-est colors. And I just want to say you'll just never know how happy you made this ol' country gal."{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=220}} | |||

| Cline's follow-up single to "I Fall to Pieces" was the song "]".{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|p=303}} It was written by ], whose version of the song was first heard by Dick. When Dick brought the song to Cline she did not like it.<ref name="NPR Crazy">{{cite web |last1=Wertheimer |first1=Linda |title=Patsy Cline's 'Crazy' Changed The Sound Of Country Music |url=https://www.npr.org/2000/09/04/1081575/crazy |website=] |access-date=August 23, 2019}}</ref> When Dick encouraged her to record "Crazy", Cline replied, "I don't care what you say. I don't like it and I ain't gonna record it. And that's that." Bradley liked the song and set the date for its recording for August 17.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=148–158}} When Cline got to Bradley's studio, he convinced her to record it.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=165}} She listened to Nelson's version of "Crazy" and decided she was going to perform it differently. Nelson's version included a spoken section that Cline removed.<ref name="NPR Crazy"/> She cut additional material on August 17 and when she got to "Crazy", it became difficult to perform. Because Cline was still recovering from the accident, performing the song's high notes caused rib pain. Giving her time to rest, Bradley sent her home while musicians laid down the track without her.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=166}} A week later she returned and recorded her vocal in a single take.<ref>See Liner Notes, ''12 Greatest Hits'', Patsy Cline, compact disc MCAD-12, MCA Records</ref><ref name="NPR Crazy"/> | |||

| ===A return in 1961 with "I Fall to Pieces"=== | |||

| {{Listen | |||

| | filename = Patsy Cline--Crazy--Audio 1961.ogg | |||

| | title = "Crazy" | |||

| | description = In 1961, "Crazy" was released as a single and became one of country music's best-known crossover recordings. | |||

| }} | |||

| "Crazy" was released as a single in October 1961, debuting on the ''Billboard'' country charts in November.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=165}} It would peak at number 2 there and number 9 on the same publication's pop charts.<ref name="Encyclopedia Virginia"/> "Crazy" would also become Cline's biggest pop hit.<ref>{{cite magazine|title=500 Greatest Songs of all Time|url=https://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/the-500-greatest-songs-of-all-time-20110407/patsy-cline-crazy-19691231|magazine=Rolling Stone|date=December 11, 2003|access-date=April 25, 2012}}</ref> Her second studio album '']'' was released in late 1961. The album featured both major hits from that year and re-recorded versions of "]" and "]".<ref>{{cite web |last1=Koda |first1=Cub |title=''Patsy Cline Showcase'': Songs, Reviews, Credits |url=https://www.allmusic.com/album/patsy-cline-showcase-mw0000195207 |website=] |access-date=August 23, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| In 1959, Cline met Randy Hughes, who became her manager. With Hughes's promotion and a new label, Cline would begin her ascent to the top. When her Four Star contract expired in 1960, she signed with ]-Nashville, under the direction of legendary producer ]. He was not only responsible for much of the success behind Cline's recording career, but he positively influenced the careers of ] and ] as well. | |||

| "Crazy" has since been called a country music standard.<ref name="American Songwriter">{{cite web |last1=Kingsbury |first1=Paul |title=BEHIND THE SONG: "Crazy" |url=https://americansongwriter.com/2007/04/behind-the-song-crazy-by-willie-nelson/ |website=American Songwriter |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref> Cline's vocal performance and the song's production have received high praise over time. ] of AllMusic noted the "ache" in her voice that makes the song stand out: "Cline's reading of the lyric is filled with an aching world weariness that transforms the tune into one of the first big crossover hits without even trying hard."<ref>{{cite web |last1=Koda |first1=Cub |title="Crazy" – Patsy Cline: Song Info |url=https://www.allmusic.com/song/crazy-mt0001413259 |website=] |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref> Country music historian Paul Kingsbury also highlighted her "ache," saying in 2007, "Cline's hit recording swings with such velvety finesse, and her voice throbs and aches so exquisitely, that the entire production sounds absolutely effortless."<ref name="American Songwriter"/> Jhoni Jackson of '']'' called the recording "iconic", highlighting the emotional "pain" Cline expressed in her voice.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Jackson |first1=Jhoni |title=The 5 Best Covers of Patsy Cline's "Crazy" |url=https://www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2016/10/the-5-best-covers-of-patsy-clines-crazy.html |website=] |date=October 11, 2016 |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Thanks to her vocal versatility, and with the help of Bradley's direction and arrangements, Cline enjoyed both country and pop success. His arrangements incorporated strings and other instruments not typical of country recordings of the day. He considered Cline's voice best-suited for ]-crossover songs, and helped smooth her voice into the silky, torch song style for which she is famous. Nevertheless, she did not enjoy singing ] material. This new, more sophisticated instrumental style became known as ], created by Bradley and RCA’s ], who produced ], ], and ].] | |||

| "Crazy" and Cline's further Decca recordings have received critical praise. Mary Bufwack and Robert Oermann noted "Her thrilling voice invariably invested these with new depth. Patsy's dramatic volume control, stretched-note effects, sobs, pauses and unique ways of holding back, then bursting into full-throated phrases also breathed new life into country chestnuts like "]", "]", and "]". {{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=220}} Richie Unterberger of AllMusic commented that her voice "sounded richer, more confident, and more mature, with ageless wise and vulnerable qualities that have enabled her records to maintain their appeal with subsequent generations."<ref name="Allmusic Bio"/> Kurt Wolff of ''Country Music the Rough Guide'' reported that Owen Bradley recognized potential in Cline's voice and once he gained studio control, he smoothed arrangements and "refined her voice into an instrument of torch-singing glory."{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|p=303}} | |||

| Cline's first Decca release was the ] ballad, "]" (1961), written by ] and ]. The song was promoted at both country and pop music stations across the country, leading to success on both country and pop charts. The song slowly climbed to the top of the country chart—Cline's first number one. The song also made No. 12 on the pop chart, as well as No. 6 on the adult contemporary chart, a major feat for any country singer at the time. The song made her a household name, demonstrating that a woman country singer could enjoy as much crossover success as a man. | |||

| ] in ], late 1962]] | |||

| In November 1961, she was invited to perform as part of the Grand Ole Opry's show at ] in ]. She was joined by Opry stars ], ], ], ], ], and ]. Despite positive reviews, '']'' columnist ] commented, "everybody should get out of town because the hillbillies are coming!" The comment upset Cline but did not affect ticket sales; the Opry performance sold out. By the end of year, Cline had won several major industry awards including "Favorite Female Vocalist" from ''Billboard Magazine'' and '']''{{'}}s "Most Programmed Female Artist".{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=170–176}} | |||

| ===The Opry and Nashville scene=== | |||

| Also in 1961, Cline was back in the studio to record an upcoming album. Among the first songs she recorded<ref>Recorded December 17, 1961. See Liner Notes, ''12 Greatest Hits,'' Patsy Cline, compact disc MCAD-12, MCA Records.</ref> was "]". Written by ], he pitched the song to Cline over the phone. Insisting that Patsy hear it in-person, Cochran brought the recording over to her house, along with a bottle of alcohol. Upon listening to it again, she liked the song and wanted to record it.<ref>{{cite web |title=History The Story Behind Patsy Cline's Heartbreaking Hit, 'She's Got You' |url=https://texashillcountry.com/the-story-behind-patsy-clines-heart-wrenching-hit-shes-got-you/ |website=Texas Hill Country |date=May 16, 2016 |access-date=August 23, 2019}}</ref> Owen Bradley also liked the song and she recorded it on December 17, 1961.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=181}} "She's Got You" became her third country-pop ] hit by early 1962.{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=219}} "She's Got You" would also be her second number 1 hit on the ''Billboard'' country chart.<ref name="Encyclopedia Virginia"/> It was also Cline's first entry in the ] singles chart, reaching number 43. The cover by ], one of Britain's most popular female artists of the 1950s, performed notably as well.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.everyhit.com/retros/index.php?page=rchart&y1=1962&m1=12&day1=1&y2=1962&m2=12&day2=1&sent=1 |title=Retro Charts |publisher=everyHit.com |date=March 16, 2000 |access-date=January 31, 2012}}</ref> | |||

| In 1960, Cline joined the cast of the Grand Ole Opry, realizing a lifelong dream. She became one of the Opry's biggest stars, and is believed to be the only person granted membership by asking. | |||

| In 1962, Cline had three major hits with "], "]", and "]".{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=219}} Cline's career successes helped her become financially stable enough to purchase her first home. She bought a ranch house located in ], a suburb of Nashville. The home was decorated by Cline and included a music room, several bedrooms and a large backyard. According to ], "the house was her mansion, the sign she'd arrived."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=170}} Cline called it her "dream home" and often had friends over to visit.{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=221}} After her death, the house was sold to country artist ].<ref name="Rare Patsy Recording">{{cite web |last1=Pursell |first1=Kate |last2=Knight-Ridder |title=RARE PATSY CLINE RECORDING EMERGES |url=https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-xpm-1997-09-07-9709110132-story.html |website=] |date=September 7, 1997 |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Believing that there was "room enough for everybody," and confident of her abilities and appeal, Cline befriended and encouraged a number of women starting out in country music, including ], ], ] (with whom Cline once toured), ] and ], all of whom cite her as an influence. According to Lynn and West, Cline always gave of herself to friends, buying them groceries and furniture when they were hard up. On occasion, she would even pay their rent, enabling them to stay in Nashville and continue their careers. In Ellis Nassour's 1980 biography ''Patsy Cline'', Cline's friend, honky tonk pianist and Opry star ], was quoted as saying, "Even when she didn't have it, she'd spend it—and not always on herself. She'd give anyone the skirt off her backside if they needed it." | |||

| In the summer of 1962, manager Randy Hughes got her a role in a country music vehicle film. It also starred Dottie West, ] and ]. After arriving to film in ], the producer "ran off with the money," according to West. The movie was never made. In August, her third studio album '']'' was released. It featured "She's Got You", as well as several country and pop standards. According to biographer Ellis Nassour, her royalties "were coming in slim" and she needed "financial security." Therefore, Randy Hughes arranged Cline to work at the ] in ] for 35 days. Cline would later dislike the experience. During the engagement, she developed a dry throat. She also was homesick and wanted to spend time with her children.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=198–208}} By appearing at the engagement, Cline became the first female country artist to headline her own show in Las Vegas.<ref name="NPR"/> | |||

| Cline also befriended ], ], ], ], ] and ], male artists and songwriters with whom she socialized at Tootsies Orchid Lounge next door to the Grand Ole Opry. In the 1986 documentary ''The Real Patsy Cline'', singer George Riddle said of her, "It wasn't unusual for her to sit down and have a beer and tell a joke. She'd never be offended at the guys' jokes, because most of the time she'd tell a joke better than you! Patsy was full of life, as I remember." | |||

| During this period Cline was said to have experienced premonitions of her own death. Dottie West, ], and Loretta Lynn recalled Cline telling them she felt a sense of impending doom and did not expect to live much longer.<ref>''The Encyclopedia of Country Music.'' Paul Kingsbury, Editor. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 98–9.</ref> In letters, she would also describe the happiness of her new career successes. In January 1963, her next single "]" was released and debuted on the ''Billboard'' country chart soon after. In February, she recorded her final sessions for Decca Records. Among the songs recorded were "]", "]", and "]". Cline arranged for friends ] and Dottie West to come and hear the session playbacks. According to Howard, "I was in awe of Patsy. You know, afterward you're supposed to say something nice. I couldn't talk. I was dumbfounded."{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=221}} | |||

| Cline used the term of endearment "Hoss" to refer to her friends, and referred to herself as The Cline. According to the book "Honky Tonk Angel: The Intimate Story of Patsy Cline" by Ellis Nassour, Patsy Cline met ] in 1962 at a fundraiser at St. Judes and they even exchanged phone numbers. Having seen him perform during one of his rare Grand Ole Opry appearances, she admired his music, called him The Big Hoss, and recorded with his backup group, ]. | |||

| ==Personal life== | |||

| Cline was in control of her own career, making it clear that she could stand up to any man—verbally and professionally—and challenge their rules if they got in the way of where she felt her career should be headed. In a time when concert promoters often cheated stars out of their money by promising to pay them after the show but running with the money during the concert, Cline stood up to many of the male promoters before she took the stage and demanded their money by proclaiming: "No dough, no show." According to friend ] in the 1986 documentary ''The Real Patsy Cline'': "Before one concert, we hadn't been paid. And we were talking about who was going to tell the audience that we couldn't perform without pay. Patsy said, 'I'll tell 'em!' And she did!" Friend Dottie West stated, "It was common knowledge around town that you didn't mess with 'The Cline!'" | |||

| ===Friendships=== | |||

| {{quote box|quote="At one time or another, she must have helped all of us girl singers who were starting out...Patsy was always giving her friends things the scrapbook of clippings and mementos Patsy gave me weeks before she was killed...when I got home I was leafing through it, and there was a check for $75 with a note saying, 'I know you have been having a hard time'...there'll never be another like Patsy Cline."|source=— ] on her friendship with Cline{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=207}}|width=25%|align=right|style=padding:8px;}} | |||

| Cline had close friendships with several country artists and performers. Her friendship with ] has been the subject of numerous books, songs, films and other projects.<ref name="Patsy and Loretta Friendship"/> The pair first met when Lynn performed "]" on the radio shortly after Cline's 1961 car accident. Cline heard the broadcast and sent her husband to pick up Lynn so they could meet. According to Lynn, the pair became close friends "right away."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=152}} Lynn later described their friendship in detail, "She taught me a lot about show business, like how to go on a stage and how to get off. She even bought me a lot of clothes... She even bought me curtains and drapes for my house because I was too broke to buy them... She was a great human being and a great friend."{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=208}} Lynn also noted they became so close that Cline even gave her underwear. Lynn still has the underwear in storage, saying it was "well-made".<ref>{{cite web | last=Hinckley | first=David | title=PBS Documentary on Loretta Lynn Recounts the Debt Modern Country Music Owes to 'Fist City' |url=https://www.huffpost.com/entry/pbs-doc-on-loretta-lynn-r_b_9377070 |website=] | date=March 3, 2016 |access-date=September 16, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| ] was another female country artist with whom Cline became friends. They first met backstage at the ]. West wrote Cline a fan letter after hearing her first hit "Walkin' After Midnight". According to West, Cline "showed a genuine interest in her career" and they became close friends. The pair often spent time at their homes and worked on packaged tour dates together.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=137}} West also stated Cline was a supportive friend who helped out in times of need.{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=207}} | |||

| ===Near-fatal car accident=== | |||

| ] was a third female artist with whom Cline had a close friendship. The pair first met when Cline tried starting an argument with Howard backstage at the Grand Ole Opry. She said to Howard, "You're a conceited little son of a bitch! You just go out there, do your spot, and leave without saying hello to anyone." Howard was upset and replied angrily back. Cline then laughed and said, "Slow down! Hoss, you're all right. Anybody that'll stand there and talk back to the Cline like that is all right...I can tell we're gonna be good friends!"{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=131}} The pair remained close for the remainder of Cline's life.{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|pp=207–208}} Other friendships Cline had with female artists included ], ] and pianist ].{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=207}} She also became friends with male country artists including ], who helped Cline find material to record. ] was another male artist whom Cline befriended from working on tour together. While on tour, the pair would spend time together, including a trip to ] where the pair saw a hula show.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=128–129}} | |||

| Cline continued to thrive in 1961, and gave birth to a son, Randy. On June 14, 1961, she and her brother, Sam, were involved in a head-on car collision on ] in Nashville, the second and more serious of two during her lifetime. The impact threw Cline into the windshield, nearly killing her. Upon arriving, ] picked glass from Patsy's hair, and went with her in the ambulance. While that happened, Patsy insisted that the other car's driver be treated first. This had a long-term detrimental effect on Ms. West; when West was fatally injured in a car accident in 1991, she insisted that the driver of her car be treated first, possibly causing her own death.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} Cline later stated that she saw the female driver of the other car die before her eyes at the hospital.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| ===Family=== | |||

| Suffering from a jagged cut across her forehead that required stitches, a broken wrist and a ], she spent a month hospitalized. While in the hospital, Cline, according to the Nassour biography ''Patsy Cline'' and to friend ] (who died in a vehicle accident in 2006), rededicated her life to ]. She received thousands of cards and flowers sent by fans. When she left the hospital, her forehead was still visibly scarred. For the remainder of her career, she wore wigs and makeup to hide the scars, and headbands to relieve pressure on her forehead. She returned to the road on crutches, determined to be a survivor with a new appreciation for life. | |||

| Cline's mother Hilda Hensley continued living in ], following her daughter's death. She rented out the family's childhood home on South Kent Street and lived across the street.<ref name="NOVA">{{cite web |title=Still 'Crazy' for Patsy |url=https://www.nvdaily.com/news/local-news/still-crazy-for-patsy/article_b28d9651-3ddc-5a9d-a2d7-9b639667a393.html |website=] |date=September 4, 2011 |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref>{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=248–249}} Following Cline's death, Hensley briefly spent time raising her two grandchildren in Virginia. Hensley maintained a closet full of her daughter's stage costumes, including a sequined dress Cline wore while performing in Las Vegas in 1962.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=248}} She worked as a seamstress and made many of her daughter's stage costumes.<ref name="Baltimore Sun">{{cite web |last1=Gomery |first1=Douglas |last2=Allen |first2=Bob |title=PATSY'S PEOPLE |url=https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1993-12-12-1993346226-story.html |website=] |date=December 12, 1993 |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref> Hensley died from natural causes in 1998.<ref name="NOVA"/> | |||

| Cline's father Samuel Hensley died of ] in 1956. Hensley had deserted the family in 1947. Shortly before his death, upon learning that he was gravely ill, Cline said to her mother, "Mama, I know what-all he did, but it seems he's real sick and may not make it. In spite of everything, I want to visit him." Cline and her mother visited him at a hospital in ].{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=68}} | |||

| In the 1990s, a series of recordings from her first concert after the accident were released. These archives, recorded in Tulsa, Oklahoma, were found in the attic of one of Cline's former residences by the current owners and given to the family. The album, released in 1997, is titled ''Patsy Cline: Live At the Cimarron Ballroom.'' and features dialogue of Cline interacting with the audience, providing an historical archive of what her live performances were like. | |||

| Cline's mother died in 1998, 35 years after Cline's death. Both of Cline's surviving siblings fought in court over their mother's estate. Because of legal fees, many of Cline's possessions were sold at auction.<ref name="NY Times">{{cite news |title=For Patsy Cline's Hometown, An Embrace That Took Decades |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/12/24/us/years-later-singer-patsy-cline-celebrated-in-hometown.html |newspaper=] |date=December 24, 2012 |access-date=September 7, 2019|last1=Barry |first1=Dan }}</ref> | |||

| ===The story of "Crazy"=== | |||

| Cline had two surviving children at the time of her death: Julie Simadore and Allen Randolph "Randy".{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=240}}<ref name="People">{{cite web |title=New Patsy Cline Museum Pays Tribute to the Timeless Country Icon |url=https://people.com/country/patsy-cline-museum-nashville/ |website=] |access-date=August 25, 2019}}</ref> Julie has been a significant factor in keeping her mother's legacy alive. She has appeared at numerous public appearances in support of her mother's music and career. Following the death of her father in 2015, she helped open a museum dedicated to Cline in ]. Julie has few memories of her mother due to Cline's death while she was young. In an interview with '']'', Julie discussed her mother's legacy, "I do understand her position in history, and the history of Nashville and country music...I'm still kind of amazed at it myself, because there's 'Mom' and then there's 'Patsy Cline,' and I'm actually a fan."<ref name="People"/> | |||

| After the success of "I Fall to Pieces", Cline needed a follow-up after a month lost from touring and promotions. Written by ], it was called "]", which Cline originally hated. Her first session recording was a disaster, and Cline claimed that the song was too difficult to sing. She tried to record "Crazy" like its demo recording, which featured Nelson's idiosyncratic style, but had a tough time recording it not only because of the demo, but also because she found the high notes hard to sing due to injured ribs from her car accident. The day in the studio at ] resulted in a head-on fight between Cline and Bradley. | |||

| The present-day American female blues, swing, and rock and roll singer, songwriter and record producer ] is a distant relation of Cline's.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://travelingboy.com/archive-travel-tim-casey_hensley.html|title=The Casey Hensley Band|website=Travelingboy.com|access-date=February 20, 2021}}</ref> | |||

| Cline recorded the song the next week in one take, a version completely different from the demo. It became a classic and, ultimately, Cline's signature song—and the one for which she remains best known. In late 1961, the song was an immediate country pop crossover hit, and also constituted her biggest pop hit, making the Top 10. Loretta Lynn later reported that the night Cline premiered "Crazy" at the Grand Ole Opry, she received three standing ovations. | |||

| ===Marriages=== | |||

| "Crazy" was a hit on three different charts in late 1961 and early 1962—the ] list (No. 2), the ] list (No. 9), and the ] list (also No. 2). An album released that November entitled '']'' featured Cline's two hits of 1961. | |||

| Cline was married twice. Her first marriage was to Gerald Cline, on March 7, 1953.<ref name="Country Music Hall of Fame"/> His family had owned a contracting and excavating company in ]. According to Cline's brother Sam, he liked "flashy cars and women." The two met while she was performing with Bill Peer at the Moose Lodge in ]. Gerald Cline said, "It might not have been love at first sight when Patsy saw me, but it was for me."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=23}} Gerald Cline often took her to "one-nighters" and other concerts she performed in. Although he enjoyed her performances, he could not get used to her touring and road schedule. During their marriage, Patsy told a friend that she didn't think she "knew what love was" upon marrying Gerald. The pair began living separately by the end of 1956 and divorced in 1957.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=45}} | |||

| Cline married her second husband ] on September 15, 1957.<ref name="Charlie Dick Billboard">{{cite magazine|url=http://www.billboard.com/articles/columns/country/6754076/charlie-dick-widower-of-patsy-cline-dies-at-81|title=Charlie Dick, Widower Of Patsy Cline, Dies At 81|last=Dauphin|first=Chuck|date=November 8, 2015|magazine=Billboard|access-date=November 8, 2015}}</ref> The pair met in 1956 while Cline was performing with a local Virginia band. At the time, Dick was a linotype operator for a local newspaper, '']''. According to Dick, he had asked Cline to dance, and she replied, "I can't dance while I'm working, okay?" They eventually started spending time together, and Cline told close friends about their relationship. Cline told ] pianist ] in 1956, "Hoss, I got some news. I met a boy my own age who's a hurricane in pants! Del, I'm in love, and it's for real this time."{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=54–55}} The pair had children Julie and Randy together.<ref name="People"/> Their relationship was considered both romantic and tempestuous. According to Robert Oermann and Mary Bufwack, Cline and Dick's marriage was "fueled by alcohol, argument, passion, jealousy, success, tears, and laughter."{{sfn|Oermann, Robert K.|Bufwack, Mary A.|2003|p=217}} | |||

| ===At the top=== | |||

| According to biographer Ellis Nassour, the pair fought often but remained together. They had gained a reputation as "heavy drinkers", but according to Dick himself, they were not "drunks".{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=127}} During one particular fight, Cline had Dick arrested after they became physical with one another.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=200}} Following Cline's death in 1963, Dick married country artist Jamey Ryan in 1965. The pair divorced in the early 1970s after having one child together. Dick helped keep Cline's legacy alive for the remainder of his life. He assisted in producing several documentaries about Cline's career, including ''Remembering Patsy'' and ''The Real Patsy Cline''. He became involved with Hallway Productions in the 1990s and helped produce videos on other artists, including ] and ]. Dick died in 2015 and was laid to rest next to Cline.<ref name="Charlie Dick Billboard"/> | |||

| With Cline’s success climbing the record charts, she was in high demand on the concert circuit. Although many women in country music at that time were considered “window dressing" or opening acts for the more popular and higher-paid male stars, Cline was the first to headline her own show and receive top billing above some of the male stars with whom she toured. While bands typically backed up the female singer, Cline led the band through the concert instead. | |||

| She was so respected by men in the industry, that rather than being introduced to audiences as “Pretty Miss Patsy Cline” as her female contemporaries often were, she was given a more stately introduction such as that given by ] on their 1962 tour together: “Ladies and gentlemen, the one and only Patsy Cline.” As an artist, she held her fan base in extremely high regard (many of whom became friends), staying for hours after concerts to chat and sign autographs. | |||

| ==Death== | |||

| Cline was not only the first woman in country music to perform at New York’s ] (which she did with fellow Opry members and disapproval from gossip columnist ]—whom Cline fired back at) but also to headline the ] with ] and, later, in 1962, the first woman in country music to headline her own show in ]. | |||

| {{Main|1963 Camden PA-24 crash}} | |||

| ] | |||

| This success enabled Cline to buy her dream home in Nashville's Goodlettsville community, personally decorated in her style featuring gold dust sprinkled in the bathroom tiles and a music room. Loretta Lynn stated in a 1986 documentary interview, "She called me into the front yard and said, 'Isn't this pretty? Now I'll never be happy until I have my Mama one just like it.'" Cline called her home "the house that Vegas built" since she was able to pay it off with the money she earned during her time there. (Later, after Cline's death in 1963, Cline's home was sold by her husband to singer ] who told ''Patsy Cline'' author Ellis Nassour that "strange occurrences" happened during her years there.) ]'', which featured her hits from that year, "I Fall to Pieces" and "Crazy". The cover (and name) were changed following Cline's death to the more-familiar version seen today.]] | |||

| On March 3, 1963, Cline performed a benefit at the ], ], for the family of disc jockey "Cactus" Jack Call; he had died in an automobile crash a little over a month earlier. Also performing in the show were ], George Riddle and The Jones Boys, ], ], ] and ], George McCormick, the ] as well as ] and ]. Despite having a cold, Cline performed at 2:00, 5:15, and 8:15 pm. All the shows were standing-room only. For the 2 p.m. show, she wore a sky-blue tulle-laden dress; for the 5:15 show, a red dress; and for the closing show at 8 p.m., Cline wore white chiffon. Her final song was the last she had recorded the previous month, "I'll Sail My Ship Alone".{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=218–221}} | |||

| With this new demand for Cline came a higher price tag, and reportedly towards the end of her life, she was being paid at least $1,000 for appearances—then an unheard-of fee for women in the country music industry, since they usually grossed less than $200. Her penultimate concert, held in Birmingham, Alabama, grossed $3,000. | |||

| Cline, who had spent the night at the ], was unable to fly out the day after the concert because ] was fogged in. West asked Patsy to ride in the car with her and her husband, Bill, back to Nashville, an 8-hour drive, but Cline refused, saying: "Don't worry about me, Hoss. When it's my time to go, it's my time." On March 5, she called her mother from the motel and checked out at 12:30 p.m., going the short distance to the airport and boarding a ] plane, ] N7000P. On board were Cline, Copas, Hawkins, and pilot Randy Hughes. | |||

| To match her new sophisticated sound, Cline also reinvented her personal style, shedding her trademark Western cowgirl outfits for elegant sequined gowns, cocktail dresses, spiked heels, and even gold lame pants. Cline’s new image was considered riskier and sexier by a then-conservative country music industry more accustomed to gingham and calico dresses for women. But like her sound, Cline’s style in fashion was mocked by many at first, then copied. She also loved dangly earrings and ruby-red lipstick; her favorite perfume was ''Wind Song''. | |||

| The plane stopped once in ], to refuel and subsequently landed at ] in ], at 5 p.m.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|pp=222–226}} Hawkins had accepted Billy Walker's place after Walker left on a commercial flight to take care of a stricken family member. The Dyersburg, Tennessee, airfield manager suggested they stay the night because of high winds and inclement weather, offering them free rooms and meals. But Hughes, who was not trained in instrument flying, said, "I've already come this far. We'll be there before you know it." The plane took off at 6:07 p.m.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://members.boardhost.com/patsyclinemusic/msg/1362527954.html |title=What really happened in the Patsy Cline plane crash |author=Larry Jordan |publisher=boardhost.com |access-date=June 19, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| During her short career of only five-and-a-half years, Cline received 12 awards for her achievements and three more following her death. Most were from '']'', '']'', and '']'', considered high honors during her time. (Awards such as the ACM and CMAs were not established until after her death, and the Nashville chapter of the Grammys wasn't founded until 1964.) | |||

| Cline's flight, however, crashed in heavy weather on the evening of March 5, 1963. Her recovered wristwatch had stopped at 6:20 p.m. The plane was found some {{convert|90|mi|km}} from its Nashville destination, in a forest outside of ]. Forensic examination concluded that everyone aboard had been killed instantly.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Artist Biography - Patsy Cline|url=http://www.countrypolitan.com/bio-patsy-cline.php/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140103065357/http://www.countrypolitan.com/bio-patsy-cline.php/|archive-date=January 3, 2014|url-status=dead|author=Sherry Anderson|work=Countrypolitan.com |date=January 2001}}</ref><ref name=bard.org>{{cite web|title=Knowing of Your Own Death|url=http://bard.org/education/studyguides/Always/patsyknowing.html|work=bard.org|publisher=Utah Shakespeare Festival|access-date=April 26, 2012|archive-date=May 25, 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120525144253/http://bard.org/education/studyguides/Always/patsyknowing.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> Until the wreckage was discovered the following dawn and reported on the radio, friends and family had not given up hope. Endless calls tied up the local telephone exchanges to such a degree that other emergency calls had trouble getting through. The lights at the aircraft's destination, ], were kept on throughout the night, as reports of the missing plane were broadcast on radio and TV. | |||

| Cline wrote of her success in a letter to friend Anne Armstrong (from the 1993 documentary ''Remembering Patsy''): "It's wonderful—but what do I do for '63? Its getting so even I can't follow Cline!" | |||

| ] | |||

| ===The last album: ''Sentimentally Yours''=== | |||

| Early in the morning, ] and a friend went searching for survivors: "As fast as I could, I ran through the woods screaming their names—through the brush and the trees—and I came up over this little rise, oh, my God, there they were. It was ghastly. The plane had crashed nose down."<ref>Ellis Nassour's "Patsy Cline" and "Honky Tonk Angel" from exclusive 1979 and 1980 interviews with Miller</ref> Shortly after the bodies were removed, looters scavenged the area. Some recovered items were eventually donated to the ]. Cline's wristwatch, a ] cigarette lighter, a studded belt, and three pairs of gold lamé slippers were among them. Cline's fee in cash from the last performance was never recovered.<ref name=bard.org /> Per her wishes, Cline's body was brought home for her memorial service, which thousands attended. People jammed against the small tent over her gold casket and the grave to take all the flowers they could reach as keepsakes.<ref>{{Cite news|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/magazine/1985/09/29/sweet-dreams/7eb27412-edbb-42fd-b117-7c3c5dd15655/|title=The Washington Post|last=McGhee|first=Dorothy|newspaper=]|date=September 29, 1985}}</ref> She was buried at Shenandoah Memorial Park in her hometown of ]. Her grave is marked with a bronze plaque, which reads: "Virginia H. Dick ('Patsy Cline' is noted under her name) 'Death Cannot Kill What Never Dies: Love'." A memorial marks the exact place off Mt Carmel Road in Camden, Tennessee, where the plane crashed in the still-remote forest.{{sfn|Nassour, Ellis|1993|p=248}} | |||

| ==Posthumous releases== | |||

| In late 1961, Cline was back in the studio to record songs for her upcoming album in 1962. One of the first songs recorded in late 1961 was the song "]", written by ], who pitched the song over the phone to Cline. It was one of the few songs Cline enjoyed recording. The song was released as a single in January 1962, and soon was another country pop crossover hit, reaching No. 1 on the country chart again (her second and last chart-topper), No. 14 on the pop charts, and No. 3 on the adult contemporary charts (originally called "Easy Listening"). It would be Cline's last Top 40 Pop hit. | |||

| ===Music=== | |||

| Since Cline's death, ] (later bought by ] and owned by ] since 1999) has re-released her music, which has made her commercially successful posthumously. '']'' was the first compilation album the label released following her death. It included the songs "]" and "]". Both tracks were released as singles in 1963.{{sfn|Wolff, Kurt|2000|p=303}} "Sweet Dreams" would reach number 5 on the ''Billboard'' country charts and 44 on the Hot 100.<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Patsy Cline: "Sweet Dreams (Of You)": Chart History: Country Songs |url=https://www.billboard.com/artist/patsy-cline/chart-history/csi/ |magazine=] |access-date=August 26, 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite magazine |title=Patsy Cline: "Sweet Dreams (Of You)": Billboard Hot 100 |url=https://www.billboard.com/artist/patsy-cline/chart-history/hsi/ |magazine=] |access-date=August 26, 2019}}</ref> "Faded Love" would also become a top 10 hit on the ''Billboard'' country chart, peaking at number 7 in October 1963.<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Patsy Cline: "Faded Love": Chart History: Country Songs |url=https://www.billboard.com/artist/patsy-cline/chart-history/csi/ |magazine=] |access-date=August 26, 2019}}</ref> In 1967, Decca released the compilation '']''. The album peaked at number 17 on the ''Billboard'' country chart, and was certified diamond in sales from the ]. In 2005, the ] included ''Greatest Hits'' for being the album to run the longest on any record chart by any female artist.<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Patsy Cline Chart History: ''Patsy Cline's Greatest Hits'' |url=https://www.billboard.com/artist/patsy-cline/chart-history/clp/ |magazine=] |access-date=August 26, 2019}}</ref><ref name="10 Things"/> | |||