| Revision as of 13:51, 8 February 2006 editSquiddy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers7,276 editsm →Early years: disambiguation link repair (You can help!)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 23:11, 20 September 2024 edit undoIvanScrooge98 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users109,622 edits +en pronTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit | ||

| (121 intermediate revisions by 67 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Polish engineer and inventor (1894–1989)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Infobox person | |||

| '''Tadeusz Sendzimir''' (originally '''Sędzimir'''], ], ], ] — ], ], ]], burried at Bethlehem near Waterburg) was an ] and ] engineer and inventor of international renown with 120 patents in ] and ], 73 of which were awarded to him in the United States]. His name has been given to revolutionary methods of processing ] and metals used in every industrialized nation of the world. Sendzimir was a holder of the Polish ] (from ]), the ] (from ]) and the ] from the Royal Academy of Technical Sciences in ] (from ]). On the 100th anniversary of the ] he was one of those prominent immigrants honored for their contributions to America. In ] Poland's largest steel plant in ] (formerly the ] Steelworks) was renamed to Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks. The ] has been established in the same year. | |||

| | name = Tadeusz Sendzimir | |||

| | image = Sendzimir Tadeusz.jpg | |||

| | caption = Sendzimir on a mural in Szczecin, 2018. | |||

| | birth_name = Tadeusz Sędzimir | |||

| | birth_date = July 15, 1894 | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| | death_date = {{death-date and age|September 1, 1989|July 15, 1894}} | |||

| | death_place = ], U.S.<ref>''Polski Słownik Biograficzny''.</ref> | |||

| | known_for = ]<br/>] | |||

| | occupation = Engineer, inventor | |||

| | nationality = Polish | |||

| | education = ] | |||

| | spouse = Barbara Alferieff <small>(1922–1942)</small><br/>Bertha Madelaine Bernoda <small>(1945)</small> | |||

| | awards = ] <small>(1938)</small><ref>{{Cite web |url=https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/DocDetails.xsp?id=WMP19362630469 |language=pl |title=M.P. 1936 nr 263 poz. 469 |website=isap.sejm.gov.pl |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> <br/>] <small>(1965)</small><br/>] <small>(1974)</small> | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Tadeusz Sendzimir''' ({{IPAc-en|lang|ˈ|s|ɛ|n|d|z|ɪ|m|ɪər}} {{respell|SEND|zim|eer}};<ref>{{OED|Sendzimir|1048285947}}</ref> originally '''Sędzimir''',{{efn|As of the 17th century version. The surname was changed after the second arrival to the United States.}} {{IPA|pl|taˈdɛ.uʂ sɛɲˈd͡ʑimir|lang}}; July 15, 1894 – September 1, 1989) was a Polish ] and ] of international renown. He held 120 patents in ] and ], 73 of which were awarded to him in the United States.<ref>.</ref> | |||

| He developed revolutionary methods of processing ] and metals used in every industrialized nation of the world. He was awarded many distinctions and honours including the Polish ] (1938), the ] (1965) and the Brinell Gold Medal of the ] in ] (1974). | |||

| ==Early years== | ==Early years== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| Sendzimir was the eldest son of Kazimierz Jaskółowski and Wanda Jaskółowska. Fascinated by machinery as a child, he built his own camera at the age of 13. After studying at the 4th Classical Gymnasium (''Gimnazjum Klasyczne'') in Lviv he entered the ] Institute (''Politechnika Lwowska''). During the upheavals of the ] and the ] he worked in the auto services in ] and in the Russian-American Chamber of commerce (authorities of ] ordered him to stay at home during the war) where he learned ] and ]. At the end of the war Sendzimir moved across ] to ], where Sendzimir built the first factory in ] which produced screws, nails and wire. Financial support was provided by the Russian-Asian Bank, headed by Poles at the time (Władysław Jezierski and Zygmunt Jastrzębski). However when Lviv was captured by Russian troops the Polytechnic Institute has been closed and Sendzimir stayed unemployed. He decided to work in Russian army, but after its retreat was forced to evacuate to Kiev. | |||

| Sendzimir was the eldest son of Kazimierz Sędzimir belonging to the ]<ref></ref><ref>Vanda Sendzimir: Steel will: the life of Tad Sendzimir. Nowy Jork: Hippocrene Books, 1994. {{ISBN|0-7818-0169-9}}</ref> and Wanda Jaskółowska.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://poland.us/strona,13,14388,0,tadeusz-sedzimir-polski-edison.html |language=pl |title=Tadeusz Sędzimir - polski Edison |website=poland.us |date=6 November 2013 |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> Fascinated by machinery as a child, he built his own camera at the age of 13. After studying at the 4th Classical Gymnasium (''Gimnazjum Klasyczne'') in Lwów he entered the ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://sendzimir.org.pl/en/about/history/ |title=Tadeusz Sendzimir – the father of modern metallurgy |website=sendzimir.org.pl |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> However when Lwów was captured by Russian troops the Polytechnic Institute was closed and he moved to ]. There he worked in auto services and in the Russian-American Chamber of commerce where he learned ] and English. | |||

| The ] forced Sendzimir to flee to ], then to ], where Sendzimir built the first factory in China which produced screws, nails and wire. Financial support was provided by the Russian-Asian Bank, at the time headed by Poles (Władysław Jezierski and Zygmunt Jastrzębski). | |||

| ==Immigration and researches== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| In ] Sendzimir married Barbara Alferieff of Russian origin. His first son Michael was born two years later. Designing and making his own machines, Sendzimir began experimenting with a new way to ] steel. Despite galvanizing, the products still tended to ]. Sendzimir discovered that the problem involved the ] bonding to a thin layer of ] on the surface rather than the pure iron. In ] Sendzimir tried to interest American industrialists in his method, but met the distrust at the start of the ]. Sendzimir arrived to ] in the next year. Returning to Poland in ], he obtained support for the construction of the first industrial-scale galvanizing unit and put into operation several cold strip mills. The idea has been explained by him as follows: "Let's imagine a piece of a hard pastry. We are rolling it on the molding-board to decrease its thickness. However it would be faster and easily if we ask any householder to stretch it by holding the edges". | |||

| ==Immigration and research== | |||

| A steel mills in ] have been founded by Sendzimir in ]. By ] ] was interested in his work and they formed a partnership, the ], to oversee the worldwide expansion of his galvanizing and mill technology. In the spring of ] Sendzimir has left ] and placed his residence in ]. Sendzimir's patented rolling mill could roll very hard materials down to very light gauges. The US company, T. Sendzimir, Inc., was established by Sendzimir in the 1940s in Waterbury, Connecticut. | |||

| In 1922 Sendzimir married Barbara Alferieff. His first son Michael was born two years later. Designing and making his own machines, Sendzimir began experimenting with a new way to ] steel. Despite galvanization, the products still had a tendency to ]. Sendzimir discovered that the problem was due to the ] bonding to a thin layer of ] on its surface, rather than to the iron. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1929 Sendzimir approached several American industrialists with his findings, but since the ] had begun, he was unsuccessful in gaining their interest. Returning to Poland in 1930, he established his original rolling mill; a year later, he contributed to constructing a galvanising plant in ] near ] employing the technology of continuous ] of steel sheets. It became known worldwide as the ]. This process was explained by him in the following words: "Let's imagine a piece of a hard pastry. We are rolling it on the pastry-board to decrease its thickness. However it would be faster and easier if we asked someone to stretch it by holding the edges". In 1934, at the ''Pokój'' Steelworks in ], he implemented another of his inventions: a method of cold rolling of thin sheet metal in industrial production.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://ipn.gov.pl/en/news/7211,Giants-of-Polish-Science-Tadeusz-Sendzimir.html |title=Giants of Polish Science - Tadeusz Sendzimir |website= ipn.gov.pl |date=8 March 2021 |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> | |||

| In ] Sendzimir married Bertha Bernoda and gained a US citizenship next year. After the war was over Sendzimir's achievements and his personality as a foreign immigrant have been ignored by the ] Poland and he even hasn't been mentioned in ''Encyklopedia Powszechna'' (Universal Encyclopedia). The situation changed when ], a new leader of the ], came to power. Sendzimir was awarded an Officer Cross of the Order of the Restoration of Poland (''Krzyż Oficerski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski''). In ] Sendzimir gained a title of doctor ''honoris causa'' from the ] in Kraków. Sendzimir's successful methods of galvanizing steel eventually were implemented in the first Z-mill rolling ] steel, making it pliable for aircraft radar. From ] until ], he introduced the first productive Z-mill to ] and to ] and ] in the l950s and l960s. In ] Sendzimir invented a spiral steel looper used in the United States and Japan. | |||

| A steel mill in ] was established by Sendzimir in 1936. By 1938 ] became interested in his work and they formed a partnership with him, the Armzen Company, to oversee the worldwide expansion of his galvanizing and mill technology. In the spring of 1939 Sendzimir moved to ]. Sendzimir's patented mill could roll hard materials down to very light gauges. The U.S. company, T. Sendzimir, Inc., was formed by him in Waterbury, Connecticut, in the 1940s. | |||

| With companies in 3 countries 5 to 90 percent of the world's ] passed through the ] by the early 1980s. Poland, ], the United Kingdom, Japan and Canada have purchased his steel mills and technologies over the years. Most notably, Sendzimir was a major financial and personal supporter of the Kościuszko Foundation, the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences and Alliance College in ]. Sendzimir died after a massive stroke and was burried by his family in a zinc-plated coffin made according to his technology. | |||

| In 1945, he married Bertha Bernoda. The following year he became a citizen of the United States. With the beginning of the ], Sendzimir and his achievements were ignored by ] Poland and he was not even mentioned in the Polish ''Encyklopedia Powszechna'' (Universal Encyclopedia). This changed when ], a new leader of the ], came to power. Sendzimir was awarded an Officer Cross of the Order ] (''Krzyż Oficerski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski'').<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://historia.agh.edu.pl/Tadeusz_Sendzimir |language=pl |title=Tadeusz Sendzimir |website=historia.agh.edu.pl |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| * <small>1- As of the 17th century version. The surname was changed after the second arrival to the United States. | |||

| In 1975 Sendzimir received the honorary degree of doctor ''honoris causa'' from the ] in Kraków. Sendzimir's successful methods for galvanizing steel eventually were implemented in the first ] rolling ] steel, making it pliable enough for use in air defense radar.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.hanrm.com/sendzimir-mill/ |title=Sendzimir Mill |website=hanrm.com |date=3 June 2019 |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> Between 1953 and 1989 he introduced the first productive Z-mill to ], and to Japan and Canada in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1974 Sendzimir invented a spiral steel looper used in both the United States and Japan. | |||

| * <small>2- According to another version (e.g. ''Polski Słownik Biograficzny'') he died in ]. | |||

| * <small>3- . | |||

| Ninety percent of the world's ] production went through the ] by the early 1980s. Poland, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada purchased his steel mills and technologies over the years. Most notably, Sendzimir was a major financial and personal supporter of the ], the ] and Alliance College in ]. Sendzimir died after a massive stroke and was buried by his family in a zinc-plated coffin made according to his design. | |||

| ==Quote== | ==Quote== | ||

| * "I have been carrying family and |

* "I have been carrying family and my only capital - a new method of zinc-plating to another coast of the Pacific." | ||

| == |

==Remembrance== | ||

| On the 100th anniversary of the ] he was one of those prominent immigrants honored for their contributions to America. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| In 1989, his life and work were the subject of a documentary film entitled ''Sendzimir''. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| In 1990 Poland's large steel plant in ] (formerly the ] Steelworks) was renamed to ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://dzieje.pl/wiadomosci/ipn-o-t-sendzimirze-jako-gigancie-polskiej-nauki-byl-polskim-edisonem-metalurgii |title=IPN o T. Sendzimirze jako "gigancie polskiej nauki": był polskim Edisonem metalurgii |website=dzieje.pl |date=8 March 2021 |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> The AIST Tadeusz Sendzimir Memorial Medal was established in the same year.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.aist.org/about-aist/awards-recognition/board-of-directors-awards/tadeusz-sendzimir-memorial-medal |title=Tadeusz Sendzimir Memorial Medal for Innovation in Steel Manufacturing Technology |website=aist.org |access-date=10 May 2023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Biblioraphy== | |||

| * Vanda Sendzimir. ''Steel Will: The Life of Tad Sendzimir''. New York, Hippocrene Books, 1994. | |||

| * M. Kalisz. ''Walcownia znaczy Sendzimir''. "Przekrój", 1973, nr. 1468. | |||

| * O. Budrewicz. ''Ocynkowane życie''. "Perspektywy", 1974, nr. 38. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| ==Sources== | |||

| * Vanda Sendzimir. ''Steel Will: The Life of Tad Sendzimir''. New York, Hippocrene Books, 1994. | |||

| * M. Kalisz. ''Walcownia znaczy Sendzimir''. "Przekrój", 1973, nr. 1468. | |||

| * O. Budrewicz. ''Ocynkowane życie''. "Perspektywy", 1974, nr. 38. | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * {{dead link|date=January 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }} | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Sendzimir, Tadeusz}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 23:11, 20 September 2024

Polish engineer and inventor (1894–1989)| Tadeusz Sendzimir | |

|---|---|

Sendzimir on a mural in Szczecin, 2018. Sendzimir on a mural in Szczecin, 2018. | |

| Born | Tadeusz Sędzimir July 15, 1894 Lemberg, Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary |

| Died | September 1, 1989 (1989-10) (aged 95) Jupiter, Florida, U.S. |

| Nationality | Polish |

| Education | Lviv Polytechnic |

| Occupation(s) | Engineer, inventor |

| Known for | Sendzimir mill Sendzimir process |

| Spouse(s) | Barbara Alferieff (1922–1942) Bertha Madelaine Bernoda (1945) |

| Awards | Gold Cross of Merit (1938) Bessemer Gold Medal (1965) Brinell Gold Medal (1974) |

Tadeusz Sendzimir (English: /ˈsɛndzɪmɪər/ SEND-zim-eer; originally Sędzimir, Polish: [taˈdɛ.uʂ sɛɲˈd͡ʑimir]; July 15, 1894 – September 1, 1989) was a Polish engineer and inventor of international renown. He held 120 patents in mining and metallurgy, 73 of which were awarded to him in the United States.

He developed revolutionary methods of processing steel and metals used in every industrialized nation of the world. He was awarded many distinctions and honours including the Polish Gold Cross of Merit (1938), the Bessemer Gold Medal (1965) and the Brinell Gold Medal of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences in Stockholm (1974).

Early years

Sendzimir was the eldest son of Kazimierz Sędzimir belonging to the Clan of Ostoja and Wanda Jaskółowska. Fascinated by machinery as a child, he built his own camera at the age of 13. After studying at the 4th Classical Gymnasium (Gimnazjum Klasyczne) in Lwów he entered the Politechnika Lwowska. However when Lwów was captured by Russian troops the Polytechnic Institute was closed and he moved to Kiev. There he worked in auto services and in the Russian-American Chamber of commerce where he learned Russian and English.

The Russian Revolution of 1917 forced Sendzimir to flee to Vladivostok, then to Shanghai, where Sendzimir built the first factory in China which produced screws, nails and wire. Financial support was provided by the Russian-Asian Bank, at the time headed by Poles (Władysław Jezierski and Zygmunt Jastrzębski).

Immigration and research

In 1922 Sendzimir married Barbara Alferieff. His first son Michael was born two years later. Designing and making his own machines, Sendzimir began experimenting with a new way to galvanize steel. Despite galvanization, the products still had a tendency to oxidize. Sendzimir discovered that the problem was due to the zinc bonding to a thin layer of iron hydroxide on its surface, rather than to the iron.

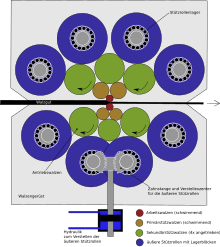

In 1929 Sendzimir approached several American industrialists with his findings, but since the Great Depression had begun, he was unsuccessful in gaining their interest. Returning to Poland in 1930, he established his original rolling mill; a year later, he contributed to constructing a galvanising plant in Kostuchna near Katowice employing the technology of continuous hot-dip galvanising of steel sheets. It became known worldwide as the Sendzimir process. This process was explained by him in the following words: "Let's imagine a piece of a hard pastry. We are rolling it on the pastry-board to decrease its thickness. However it would be faster and easier if we asked someone to stretch it by holding the edges". In 1934, at the Pokój Steelworks in Ruda Śląska, he implemented another of his inventions: a method of cold rolling of thin sheet metal in industrial production.

A steel mill in Butler, Pennsylvania was established by Sendzimir in 1936. By 1938 Armco Steel became interested in his work and they formed a partnership with him, the Armzen Company, to oversee the worldwide expansion of his galvanizing and mill technology. In the spring of 1939 Sendzimir moved to Middletown, Ohio. Sendzimir's patented mill could roll hard materials down to very light gauges. The U.S. company, T. Sendzimir, Inc., was formed by him in Waterbury, Connecticut, in the 1940s.

In 1945, he married Bertha Bernoda. The following year he became a citizen of the United States. With the beginning of the Cold War, Sendzimir and his achievements were ignored by Communist Poland and he was not even mentioned in the Polish Encyklopedia Powszechna (Universal Encyclopedia). This changed when Edward Gierek, a new leader of the Polish United Workers' Party, came to power. Sendzimir was awarded an Officer Cross of the Order Polonia Restituta (Krzyż Oficerski Orderu Odrodzenia Polski).

In 1975 Sendzimir received the honorary degree of doctor honoris causa from the AGH University of Science and Technology in Kraków. Sendzimir's successful methods for galvanizing steel eventually were implemented in the first Z-mill rolling silicon steel, making it pliable enough for use in air defense radar. Between 1953 and 1989 he introduced the first productive Z-mill to Great Britain, and to Japan and Canada in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1974 Sendzimir invented a spiral steel looper used in both the United States and Japan.

Ninety percent of the world's galvanized steel production went through the Sendzimir process by the early 1980s. Poland, France, the United Kingdom, Japan, and Canada purchased his steel mills and technologies over the years. Most notably, Sendzimir was a major financial and personal supporter of the Kościuszko Foundation, the Polish Institute of Arts and Sciences of America and Alliance College in Pennsylvania. Sendzimir died after a massive stroke and was buried by his family in a zinc-plated coffin made according to his design.

Quote

- "I have been carrying family and my only capital - a new method of zinc-plating to another coast of the Pacific."

Remembrance

On the 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty he was one of those prominent immigrants honored for their contributions to America.

In 1989, his life and work were the subject of a documentary film entitled Sendzimir.

In 1990 Poland's large steel plant in Kraków (formerly the Lenin Steelworks) was renamed to Tadeusz Sendzimir Steelworks. The AIST Tadeusz Sendzimir Memorial Medal was established in the same year.

See also

- Sendzimir process

- Ostoja coat of arms

- Clan of Ostoja

- Timeline of Polish science and technology

- List of Polish inventors and discoverers

Notes

- As of the 17th century version. The surname was changed after the second arrival to the United States.

References

- Polski Słownik Biograficzny.

- "M.P. 1936 nr 263 poz. 469". isap.sejm.gov.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Sendzimir". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/OED/1048285947. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Sarmatian Review XV.1.

- Geni

- Vanda Sendzimir: Steel will: the life of Tad Sendzimir. Nowy Jork: Hippocrene Books, 1994. ISBN 0-7818-0169-9

- "Tadeusz Sędzimir - polski Edison". poland.us (in Polish). 6 November 2013. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Tadeusz Sendzimir – the father of modern metallurgy". sendzimir.org.pl. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Giants of Polish Science - Tadeusz Sendzimir". ipn.gov.pl. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Tadeusz Sendzimir". historia.agh.edu.pl (in Polish). Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Sendzimir Mill". hanrm.com. 3 June 2019. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "IPN o T. Sendzimirze jako "gigancie polskiej nauki": był polskim Edisonem metalurgii". dzieje.pl. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

- "Tadeusz Sendzimir Memorial Medal for Innovation in Steel Manufacturing Technology". aist.org. Retrieved 10 May 2023.

Sources

- Vanda Sendzimir. Steel Will: The Life of Tad Sendzimir. New York, Hippocrene Books, 1994.

- M. Kalisz. Walcownia znaczy Sendzimir. "Przekrój", 1973, nr. 1468.

- O. Budrewicz. Ocynkowane życie. "Perspektywy", 1974, nr. 38.

External links

- The Sendzimir Foundation site

- Sendzimir mills

- Tadeusz Gajl, Herbarz Polski, Sędzimir CoA

- T. Sendzimir, Inc.

- 1894 births

- 1989 deaths

- 20th-century American engineers

- Polish engineers

- Polish inventors

- Polish emigrants to the United States

- Engineers from Lviv

- People from Waterbury, Connecticut

- Officers of the Order of Polonia Restituta

- Recipients of the Gold Cross of Merit (Poland)

- Clan of Ostoja

- Lviv Polytechnic alumni

- Bessemer Gold Medal

- Engineers from Connecticut

- 20th-century American inventors