| Revision as of 08:18, 9 October 2010 edit90.212.77.135 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:31, 10 January 2025 edit undoYabroq (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users15,006 editsm →Scholarly work: cmm | ||

| (251 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|German philosopher (1812–1875)}} | |||

| {{refimprove|date=January 2008}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox philosopher | |||

| | honorific_prefix = | |||

| | name = Moses Hess | |||

| | native_name = <!-- add name in the philosopher's language or script if different from the English name --> | |||

| | honorific_suffix = | |||

| | image = Moses Hess-1.2 (cropped).jpg | |||

| | image_size = | |||

| | alt = | |||

| | caption = ] of Moses Hess in 1870. | |||

| | other_names = | |||

| | birth_name = <!-- only use if different from name --> | |||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1812|01|21|df=y}}<ref name="Silberner 1966">{{Cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=kikJAQAAIAAJ|title=Moses Hess. Geschichte seines Lebens|last=Silberner|first=Edmund|date=1966|publisher=E. J. Brill|isbn=978-90-04-02020-7 |language=de}}</ref> | |||

| | birth_place = ], ] (Now ]) | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1875|04|06|1812|01|21|df=y}}<ref name="Berlin 1957" /> | |||

| | death_place = ], France | |||

| | nationality = <!-- use only when necessary per ] --> | |||

| | spouse = Sibylle Pesch | |||

| | partner = | |||

| | children = | |||

| | family = | |||

| | relatives = | |||

| | education = ] (withdrew) | |||

| | occupation = | |||

| | notable_works = '']'' | |||

| | awards = | |||

| | signature = | |||

| | signature_size = | |||

| | signature_alt = | |||

| | era = | |||

| | region = | |||

| | school_tradition = | |||

| | institutions = | |||

| | thesis_title = <!--(or | thesis1_title = and | thesis2_title = )--> | |||

| | thesis_url = <!--(or | thesis1_url = and | thesis2_url = )--> | |||

| | thesis_year = <!--(or | thesis1_year = and | thesis2_year = )--> | |||

| | doctoral_advisor = <!--(or | doctoral_advisors = )--> | |||

| | academic_advisors = | |||

| | doctoral_students = | |||

| | notable_students = | |||

| | language = | |||

| | main_interests = ] | |||

| | notable_ideas = ] | |||

| | influences = ] | |||

| | influenced = ], ], ], ], ], ], ] | |||

| | website = <!-- {{URL|example.com}} --> | |||

| }} | |||

| '''Moses''' ('''Moritz''')<ref name="Berlin 1957" /> '''Hess''' (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875)<ref name="Silberner 1966" /> was a ] philosopher, early ] and ] thinker.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book |last=Hess |first=Moses |author-link=Moses Hess |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=okO6iEYT4_MC |title=Moses Hess: The Holy History of Mankind and Other Writings |date=2004-12-02 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-0-521-38756-9 |language=en}}</ref> His theories led to disagreements with ] and ].<ref name="Marx & Engels 1932"/> He is considered a pioneer of ].<ref name=":0" /> | |||

| {{Socialism sidebar}} | |||

| ==Biography== | |||

| ] | |||

| Moses Hess was born in ],<ref name="Silberner 1966" /> which was under French rule at the time. In his French-language birth certificate, his name is given as "'''Moïse'''"; he was named after his maternal grandfather.<ref name="Avineri 1985">{{Cite book |last=Avineri |first=Shlomo |author-link=Shlomo Avineri |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/11519654 |title=Moses Hess, prophet of communism and Zionism |date=1985 |publisher=] |isbn=0-8147-0584-7 |location=New York |oclc=11519654}}</ref>{{rp|7}} His father was an ordained rabbi, but never practiced this profession.<ref name="Avineri 1985" /> Hess received a Jewish religious education from his grandfather, and later studied philosophy at the ], but never graduated.<ref name="Berlin 1957">{{cite AV media |last=Berlin |first=Isaiah |orig-date=1957 |title=The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess |location=], United Kingdom |publisher=] |publication-date=1959 |date=2009-04-15 |url=http://media.podcasts.ox.ac.uk/wolf/berlin/hess.mp3 |access-date=2021-04-21 |series=] Memorial Lecture |chapter=From Communism to Zionism: Moses Hess |chapter-url=https://www.marxists.org/subject/jewish/moses-hess.pdf |archive-url=https://archive.org/details/podcast_isaiah-berlin-centenary_from-communism-to-zionism-mos_1000410387884 |archive-date=2019-12-12 |transcript-url={{GBurl|O1wNAAAAIAAJ}} |transcript=The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess |author-link=Isaiah Berlin }}</ref> | |||

| '''Moses (Moshe) Hess''' (June 21, 1812 – April 6, 1875) was a ]ish philosopher and one of the founders of ] and a precursor to ]. | |||

| ]. ]] | |||

| ==Life== | |||

| He married a poor ] seamstress, Sibylle Pesch, "in order to redress the injustice perpetrated by society". Although they remained happily married until Hess' death,<ref name="Berlin 1957" /> Sibylle may have had an affair with ] while he was smuggling her from Belgium to France to be reunited with her husband. Sibylle, however, claimed the relationship was non-consensual and accused Engels of rape.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hunt |first=Tristram |title=The Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels |publisher=Metropolitan/Henry Holt & Co |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-8050-8025-4}}</ref> The incident may have precipitated Hess' split from the communist movement.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Henderson |first=William Otto |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4eYXc1B1vPoC&q=Friedrich+Engels+Sybille+Pesch&pg=PA89 |title=The Life of Friedrich Engels |date=1976 |publisher=Taylor & Francis |isbn=978-0-7146-4002-0 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| Hess was born in ], which was under French rule at the time. In his French-language birth certificate, his name is given as "Moises"; he was named after his maternal grandfather.<ref>Shlomo Avineri, ''Moses Hess: Prophet of Communism and Zionism'', p. 7</ref> Hess received a Jewish religious education from his grandfather, and later studied philosophy at the ], but never graduated. | |||

| Hess was an early proponent of ], and a precursor to what would later be called ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Battegay, Lubrich |first=Caspar, Naomi |title=Jewish Switzerland: 50 Objects Tell Their Stories |publisher=Christophe Merian |year=2018 |isbn=9783856168476 |pages=126–129 |language=de, en}}</ref> As a correspondent for the '']'', a radical newspaper founded by liberal Rhenish businessmen, he lived in Paris. He was a friend and important collaborator of ], who was the editor of the {{lang|de|Rheinische Zeitung}}, following his advice, and befriended also with ].<ref name="Hunt_2010">{{Citation |last=Hunt |first=Tristram |title=Marx's General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Mdj3AXU2YEEC |year=2010 |postscript=. |publisher=Macmillan |isbn=978-1-4299-8355-6 |author-link=Tristram Hunt}}</ref> Hess initially introduced Engels to communism, through his theoretical approach.<ref name="Hunt_2010"/> | |||

| He was an early proponent of a variation of ] which would pave the way for ], and a precursor to what would later be called ]. His works included | |||

| '']'' (1837), '']'' (1841) and '']'' (1862). He married a Catholic working-class woman, Sibylle Pesch, in defiance of bourgeois values. In Marxist literature the idea was propagated that she was a prostitute 'redeemed' by Hess, but that notion has been refuted by Hess' biographer Silberner.<ref>Avineri, p. 17</ref> | |||

| Marx, Engels and Hess took refuge in Brussels, Belgium, in 1845, and used to live in the same street. By the end of the decade, Marx and Engels had fallen out with Hess.<ref name="Hunt_2010"/> The work of Hess was also criticized in part of '']'' by Marx and Engels.<ref name="Marx & Engels 1932">{{Cite book |last1=Marx |first1=Karl |last2=Engels |first2=Friedrich |orig-date=1846 |editor-last=Arthur |editor-first=Christopher John |title=The German Ideology |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20010715125344/https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1845/german-ideology/ch04e.htm |archive-date=2001-07-15 |access-date=2022-08-21 |publication-date=1932 |publisher=] |language=en |url={{GBurl|c3nWAAAAMAAJ}} |isbn=978-0-8285-0008-1 |volume=II |chapter=Part V: “Doctor Georg Kuhlmann Of Holstein” Or The Prophecies of True Socialism |year=1976 |chapter-url=http://fs2.american.edu/dfagel/www/Class%20Readings/Marx/The%20German%20Ideology.pdf |author1-link=Karl Marx |author2-link=Friedrich Engels}}</ref> | |||

| As correspondent for the "Rheinische Zeitung", a radical newspaper founded by liberal Rhenish businessmen (and for which ] also worked), he lived in ], fleeing to ] and ] temporarily following the suppression of the 1848 commune and again during the Franco-Prussian war. | |||

| Hess fled to ] temporarily following the suppression of the ]. He would also go abroad during the ] of 1870–1871. During the 1850s Hess immersed himself into studying the natural sciences and gaining, in an autodidactic fashion, a scientific foundation for his thoughts.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Daum |first=Andreas W. |author-link=Andreas W. Daum |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/43318002 |title=Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Jahrhundert : bürgerliche Kultur, naturwissenschaftliche Bildung und die deutsche Öffentlichkeit, 1848-1914 |date=1998 |publisher=R. Oldenbourg |isbn=3-486-56337-8 |location=München |oclc=43318002 |pages=407, 415–17, 454, 467, 492}}</ref> | |||

| ===Communism=== | |||

| Hess originally advocated Jewish integration into the universalist socialist movement, and was a friend and collaborator of ] and ]. Hess converted Engels to ], and introduced Marx to social and economic problems. He played an important role in transforming ]ian dialectical idealism theory of history to the ] of Marxism, by conceiving of man as the initiator of history through his active consciousness. | |||

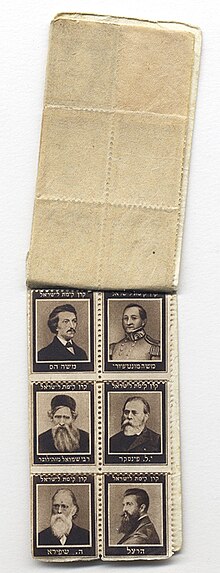

| Hess died in Paris in 1875. A non-religious ceremony was held in which he was eulogized by representatives of French radical democrats, German socialists, and the German workers in Paris.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Hess |first=Moses |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=sKZF3n19kFoC |title=Moses Hess: The Holy History of Mankind and Other Writings |date=2004-12-02 |publisher=Cambridge University Press |isbn=978-1-139-45524-4 |language=en}}</ref> As he requested, he was buried in the Jewish cemetery of ]. In 1961, he was re-interred in the ] Cemetery in Israel along with other ] such as ], ], and ]. | |||

| Hess was probably responsible for several "Marxian" slogans and ideas, including religion as the "opiate of the people." Hess became reluctant to base all history on economic causes and class struggle, and he came to see the struggle of races, or nationalities, as the prime factor of past history. | |||

| ] ] was named in his honour. | |||

| After the failure of the revolutionary war in summer 1849 in Palatinate and Baden and the fall of ], the last refuge of the revolutionaries, the artillery commander ] (whose adjunct officer was ]) and his wife ], who were old friends from Hess' Cologne days, close to Hess' friend ] and leading personalities of the Communist Club in Cologne, found temporary refuge in his home in ] before moving on to the United States. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ==Views and opinions== | |||

| ===Proto-Zionism=== | |||

| Hess became reluctant to base all history on economic causes and ] (as Marx and Engels did), and he came to see the struggle of races, or nationalities, as the prime factor of history. | |||

| From 1861 to 1863 he lived in Germany, where he became acquainted with the rising tide of German ]. It was then that he reverted to his Jewish name Moses in protest against assimilationism. In this period he apparently returned to religion in the form of ]'s ], which he somehow did not find incompatible with ]. He published '']'' in 1861. Hess interprets history as a circle of ] and ]s. He contemplated the rise of ] nationalism and the German reaction to it, and from this he arrived at the idea of Jewish national revival, and at his prescient understanding that the Germans would not be tolerant of the national aspirations of others and would be particularly intolerant of the Jews. His book calls for the establishment of a Jewish socialist commonwealth in Palestine, in line with the emerging national movements in Europe and as the only way to respond to antisemitism and assert Jewish identity in the modern world. | |||

| According to ], Hess, who differed from Marx on a number of issues, still testified in a letter to ] that what he and Herzen were writing about "resembles a neat sketch drawn on paper, whereas Marx's judgment upon these events is as it were engraved with iron force in the rock of time" (Paraphrased by George Lichtheim, ''A Short History of Socialism'', 1971 p. 80). | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| Hess's ''Rome and Jerusalem. The Last National Question'' went unnoticed in his time, along with the rest of his writings. Most German Jews were bent on assimilation and did not heed Hess' unfashionable warnings. His work did not stimulate any political activity or discussion. Hess's contribution, like ]'s ''Autoemancipation'',<ref>Leon Pinsker, </ref> became important only in retrospect, as the ] movement began to crystallize and to generate an audience in the late nineteenth century. When ] first read ''Rome and Jerusalem'' he wrote about Hess that "since ] jewry had no bigger thinker than this forgotten Moses Hess" and that he would not have written ''Der Judenstaat'' (''The Jewish State'') if he had known ''Rome and Jerusalem'' beforehand. ] honored Hess in ''The Jewish Legion in World War'' as one of those people that made the ] possible, together with Herzl, Rothschild and Pinsker. | |||

| From 1861 to 1863, he lived in Germany, where he became acquainted with the rising tide of German ]. It was then that he reverted to his Jewish name Moses (after going by Moritz Hess)<ref name="Berlin 1957"/><ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Moses-Hess|title=Moses Hess: German author and Zionist|website=]|date=2 April 2024|access-date=19 February 2020|archive-date=8 June 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220608073149/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Moses-Hess|url-status=live}}</ref> in protest against ]. He published '']'' in 1862. Hess interprets history as a circle of ] and national struggles. He contemplated the rise of ] and the German reaction to it, and from this he arrived at the idea of Jewish national revival, and at his prescient understanding that the Germans would not be tolerant of the national aspirations of others and would be particularly intolerant of the Jews. His book calls for the establishment of a Jewish socialist commonwealth in ], in line with the emerging national movements in Europe and as the only way to respond to antisemitism and assert Jewish identity in the modern world. | |||

| Hess died in Paris in 1875. As he requested, he was buried in the Jewish cemetery of ]. In 1961 he was re-interred in the ] Cemetery in Israel along with other ] such as ], ], and ]. The ] ] was named in his honour. | |||

| ], Israel]] | |||

| ==Quotes== | |||

| * "You may don a thousand masks, change your name and your religion and your mode of life, creep through the world incognito so that nobody notices that you are a Jew yet every insult to the Jewish name will wound you more than a man of honour who remains loyal to his family and defends his good name." | |||

| ==Scholarly work== | |||

| * "Even an act of conversion cannot relieve the Jew of the enormous pressure of German anti-Semitism. The Germans hate the religion of the Jews less than they hate their race - they hate the peculiar faith of the Jews, less than their peculiar noses." | |||

| Hess's '']'' went unnoticed in his time, as most German Jews preferred ]. His work did not stimulate political activity or discussion. When ] first read ''Rome and Jerusalem'' he wrote that "since ], Jewry had no bigger thinker than this forgotten Moses Hess." He said he might not have written {{lang|de|Der Judenstaat}} (''The Jewish State'') if he had known ''Rome and Jerusalem'' beforehand. ] honored Hess in ''The Jewish Legion in the World War'' as one of the people that made the ] possible, along with Herzl, ] and ]. | |||

| == Published works== | |||

| * "The ] is the primal one, and the ] secondary. The last dominating race is the German." | |||

| * "Yet it seems that a final race struggle is unavoidable" | |||

| * "The Messianic era is the present age, which began to germinate with the teachings of Spinoza, and finally came into historical existence with the great French Revolution." | |||

| * "To this coming cult, Judaism alone holds the key. This "religion of the future" of which the eighteenth century philosophers, as well as their recent followers, dreamed Each nation will have to create its own historical cult; each people must become like the Jewish people, a people of God." | |||

| (Quotes from ''Rome and Jerusalem'' by Moses Hess) | |||

| * "The Christian... imagines the better future of the human species... in the image of heavenly joy... We, on the other hand, will have this heaven on earth." | |||

| (Quote from ''A Communist Confession of Faith'' by Moses Hess)<ref>, 16th paragraph</ref><ref></ref> | |||

| == Works by Hess == | |||

| *'']'' (1837) | *'']'' (1837) | ||

| *'']'' (1841) | *'']'' (1841) | ||

| * '''' (1842) | |||

| *'']'' (1845) could this title be "On the Essence of Money see art and English trans in: Julius Kovesi, "Values and Evaluations", (Peter Lang, New York, 1998, American University Studies, ser V, vol 183) p. 127-207} | |||

| * ''Die Philosophie der Tat'' (''The Philosophy of Action'', 1843) | |||

| *'']'' (1846), London (do not confuse with '']'' authored mainly by ] and with minor help of ] leaders ] and ]<ref></ref>) | |||

| *'']'', also translated as ''On the Essence of Money''<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kovesi |first=Julius |url=https://openlibrary.org/books/OL28950625M/Values_and_Evaluations |title=Values and Evaluations: Essays on Ethics and Ideology- Edited by Alan Tapper |date=2001 |publisher=Lang AG International Academic Publishers, Peter |isbn=978-0-8204-5760-4 |volume=183 |pages=127–207|ol=28950625M }}</ref> (Über das Geldwesen, 1845) | |||

| *'']'' (London, 1846)<ref>{{Cite web|title=Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith - Engels|url=http://marxengels.public-archive.net/en/ME0152en.html|access-date=2022-08-18|website=marxengels.public-archive.net|archive-date=6 June 2022|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220606193612/http://marxengels.public-archive.net/en/ME0152en.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *'']'' (1847) | *'']'' (1847) | ||

| *'']'' Leipzig: Eduard Mengler (1862) |

*'']'' Leipzig: Eduard Mengler (1862) | ||

| *'']'' (1864) | *'']'' (1864) | ||

| *'']'' (1869) | *'']'' (1869) | ||

| *'']'' (1869) | *'']'' (1869) | ||

| *'']'' (1877) | *'']'' (1877) | ||

| * '''' (anthology edited by Theodor Zlocisti; Berlin: Louis Lamm, 1905) | |||

| {{wikisource author}} | |||

| == Translations == | === Translations === | ||

| *'']'' |

*'']''. ed. Shlomo Avineri (Cambridge University Press, 2005). | ||

| *'']'', Volume III, Graetz (1866–1867, into French) | |||

| ==References== |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist}} | ||

| == |

==Further reading== | ||

| *], '' |

*], ''Emanzipation und Messianismus. Leben und Werk des Moses Heß'' (Frankfurt a.M./New York,1982) (in German) | ||

| *{{Cite journal |last=Schweigmann-Greve |first=Kay |date=2008 |title=Jüdische Nationalität aus verweigerter Assimilation: Biographische Parallelen bei Moses Hess und Chaim Zhitlowsky und ihre ideologische Verarbeitung |url=https://ixtheo.de/Record/566939576 |language=German |archive-url=https://www.academia.edu/33981855 |archive-date=2017-07-21 |journal=Trumah, Jüdische Studien und jüdische Identität |publisher=Zeitschrift der Hochschule für jüdische Studien |location=Heidelberg |pages=91–116 |volume=17}} | |||

| *], ''Emanzipation und Messianismus. Leben und Werk des Moses Heß'' (Frankfurt a.M./New York,1982)(in German) | |||

| *], ''Moses Hess: Prophet of Communism and Zionism'' (New York, 1985). | |||

| *], ''Jüdische Nationalität aus verweigerter Assimilation. Biographische Parallelen bei Moses Hess und Chajm Zhitlowsky und ihre ideologische Verarbeitung.'' In: Trumah, Journal of the Hochschule for Jewish Studies Heidelberg, Vol 17, 2007 p. 91-116 (in German) | |||

| {{wikiquote}} | |||

| == External links == | == External links == | ||

| * {{commons category-inline}} | |||

| *, ed. & trans by Shlomo Avineri (2004) | |||

| * {{wikiquote-inline}} | |||

| *, from the ] | |||

| * {{wikisource author-inline}} | |||

| * (ger.) | |||

| * , ed. & trans by Shlomo Avineri (2004). at the Wayback Machine. | |||

| * (ger.) | |||

| * at ] | |||

| * , from the ] | |||

| * Archive of at the ] | |||

| * Kalonymos, Gregor Pelger: "Zur Restauration des jüdischen Staates. Moses Heß (1812-1875)"] (in German). at the Wayback Machine. | |||

| * Homepage Moses Hess Projects (in German). at the Wayback Machine. | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Hess, Moses}} | {{DEFAULTSORT:Hess, Moses}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:31, 10 January 2025

German philosopher (1812–1875)

| Moses Hess | |

|---|---|

Daguerrotype of Moses Hess in 1870. Daguerrotype of Moses Hess in 1870. | |

| Born | (1812-01-21)21 January 1812 Bonn, French Empire (Now Germany) |

| Died | 6 April 1875(1875-04-06) (aged 63) Paris, France |

| Education | University of Bonn (withdrew) |

| Notable work | Rome and Jerusalem: The Last National Question |

| Spouse | Sibylle Pesch |

| Main interests | Socialism |

| Notable ideas | Labor Zionism |

Moses (Moritz) Hess (21 January 1812 – 6 April 1875) was a German-Jewish philosopher, early communist and Zionist thinker. His theories led to disagreements with Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. He is considered a pioneer of Labor Zionism.

Biography

Moses Hess was born in Bonn, which was under French rule at the time. In his French-language birth certificate, his name is given as "Moïse"; he was named after his maternal grandfather. His father was an ordained rabbi, but never practiced this profession. Hess received a Jewish religious education from his grandfather, and later studied philosophy at the University of Bonn, but never graduated.

He married a poor Catholic seamstress, Sibylle Pesch, "in order to redress the injustice perpetrated by society". Although they remained happily married until Hess' death, Sibylle may have had an affair with Friedrich Engels while he was smuggling her from Belgium to France to be reunited with her husband. Sibylle, however, claimed the relationship was non-consensual and accused Engels of rape. The incident may have precipitated Hess' split from the communist movement.

Hess was an early proponent of socialism, and a precursor to what would later be called Zionism. As a correspondent for the Rheinische Zeitung, a radical newspaper founded by liberal Rhenish businessmen, he lived in Paris. He was a friend and important collaborator of Karl Marx, who was the editor of the Rheinische Zeitung, following his advice, and befriended also with Friedrich Engels. Hess initially introduced Engels to communism, through his theoretical approach.

Marx, Engels and Hess took refuge in Brussels, Belgium, in 1845, and used to live in the same street. By the end of the decade, Marx and Engels had fallen out with Hess. The work of Hess was also criticized in part of The German Ideology by Marx and Engels.

Hess fled to Switzerland temporarily following the suppression of the 1848 commune. He would also go abroad during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870–1871. During the 1850s Hess immersed himself into studying the natural sciences and gaining, in an autodidactic fashion, a scientific foundation for his thoughts.

Hess died in Paris in 1875. A non-religious ceremony was held in which he was eulogized by representatives of French radical democrats, German socialists, and the German workers in Paris. As he requested, he was buried in the Jewish cemetery of Cologne. In 1961, he was re-interred in the Kinneret Cemetery in Israel along with other Socialist-Zionists such as Nachman Syrkin, Ber Borochov, and Berl Katznelson.

Moshav Kfar Hess was named in his honour.

Views and opinions

Hess became reluctant to base all history on economic causes and class struggle (as Marx and Engels did), and he came to see the struggle of races, or nationalities, as the prime factor of history.

According to George Lichtheim, Hess, who differed from Marx on a number of issues, still testified in a letter to Alexander Herzen that what he and Herzen were writing about "resembles a neat sketch drawn on paper, whereas Marx's judgment upon these events is as it were engraved with iron force in the rock of time" (Paraphrased by George Lichtheim, A Short History of Socialism, 1971 p. 80).

From 1861 to 1863, he lived in Germany, where he became acquainted with the rising tide of German antisemitism. It was then that he reverted to his Jewish name Moses (after going by Moritz Hess) in protest against Jewish assimilation. He published Rome and Jerusalem in 1862. Hess interprets history as a circle of race and national struggles. He contemplated the rise of Italian nationalism and the German reaction to it, and from this he arrived at the idea of Jewish national revival, and at his prescient understanding that the Germans would not be tolerant of the national aspirations of others and would be particularly intolerant of the Jews. His book calls for the establishment of a Jewish socialist commonwealth in Palestine, in line with the emerging national movements in Europe and as the only way to respond to antisemitism and assert Jewish identity in the modern world.

Scholarly work

Hess's Rome and Jerusalem: The Last National Question went unnoticed in his time, as most German Jews preferred cultural assimilation. His work did not stimulate political activity or discussion. When Theodor Herzl first read Rome and Jerusalem he wrote that "since Spinoza, Jewry had no bigger thinker than this forgotten Moses Hess." He said he might not have written Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State) if he had known Rome and Jerusalem beforehand. Vladimir Ze'ev Jabotinsky honored Hess in The Jewish Legion in the World War as one of the people that made the Balfour declaration possible, along with Herzl, Walter Rothschild and Leon Pinsker.

Published works

- Holy History of Mankind (1837)

- European Triarchy (1841)

- Socialism and Communism (1842)

- Die Philosophie der Tat (The Philosophy of Action, 1843)

- On the Monetary System, also translated as On the Essence of Money (Über das Geldwesen, 1845)

- Communist Confession of Faith (London, 1846)

- Consequences of a Revolution of the Proletariat (1847)

- Rome and Jerusalem Leipzig: Eduard Mengler (1862)

- Letters on the Mission of Israel (1864)

- High Finance and the Empire (1869)

- Les Collectivistes et les Communistes (1869)

- The Dynamic Theory of Matter (1877)

- Jüdische Schriften (anthology edited by Theodor Zlocisti; Berlin: Louis Lamm, 1905)

Translations

- The Holy History and Mankind and Other Writings. ed. Shlomo Avineri (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- The History of the Jews, Volume III, Graetz (1866–1867, into French)

References

- ^ Silberner, Edmund (1966). Moses Hess. Geschichte seines Lebens (in German). E. J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-02020-7.

- ^ Berlin, Isaiah (15 April 2009) . "From Communism to Zionism: Moses Hess". The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess. Lucien Wolf Memorial Lecture. Oxford University, United Kingdom: Jewish Historical Society of England (published 1959). Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 December 2019. The Life and Opinions of Moses Hess. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ Hess, Moses (2 December 2004). Moses Hess: The Holy History of Mankind and Other Writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38756-9.

- ^ Marx, Karl; Engels, Friedrich (1976) . "Part V: "Doctor Georg Kuhlmann Of Holstein" Or The Prophecies of True Socialism". In Arthur, Christopher John (ed.). The German Ideology. Vol. II. International Publishers (published 1932). ISBN 978-0-8285-0008-1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 July 2001. Retrieved 21 August 2022.

- ^ Avineri, Shlomo (1985). Moses Hess, prophet of communism and Zionism. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-0584-7. OCLC 11519654.

- Hunt, Tristram (2009). The Frock-Coated Communist: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels. Metropolitan/Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 978-0-8050-8025-4.

- Henderson, William Otto (1976). The Life of Friedrich Engels. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-7146-4002-0.

- Battegay, Lubrich, Caspar, Naomi (2018). Jewish Switzerland: 50 Objects Tell Their Stories (in German and English). Christophe Merian. pp. 126–129. ISBN 9783856168476.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hunt, Tristram (2010), Marx's General: The Revolutionary Life of Friedrich Engels, Macmillan, ISBN 978-1-4299-8355-6.

- Daum, Andreas W. (1998). Wissenschaftspopularisierung im 19. Jahrhundert : bürgerliche Kultur, naturwissenschaftliche Bildung und die deutsche Öffentlichkeit, 1848-1914. München: R. Oldenbourg. pp. 407, 415–17, 454, 467, 492. ISBN 3-486-56337-8. OCLC 43318002.

- Hess, Moses (2 December 2004). Moses Hess: The Holy History of Mankind and Other Writings. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-45524-4.

- "Moses Hess: German author and Zionist". Encyclopedia Britannica. 2 April 2024. Archived from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 19 February 2020.

- Kovesi, Julius (2001). Values and Evaluations: Essays on Ethics and Ideology- Edited by Alan Tapper. Vol. 183. Lang AG International Academic Publishers, Peter. pp. 127–207. ISBN 978-0-8204-5760-4. OL 28950625M.

- "Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith - Engels". marxengels.public-archive.net. Archived from the original on 6 June 2022. Retrieved 18 August 2022.

Further reading

- Shlomo Na'aman, Emanzipation und Messianismus. Leben und Werk des Moses Heß (Frankfurt a.M./New York,1982) (in German)

- Schweigmann-Greve, Kay (2008). "Jüdische Nationalität aus verweigerter Assimilation: Biographische Parallelen bei Moses Hess und Chaim Zhitlowsky und ihre ideologische Verarbeitung". Trumah, Jüdische Studien und jüdische Identität (in German). 17. Heidelberg: Zeitschrift der Hochschule für jüdische Studien: 91–116. Archived from the original on 21 July 2017.

External links

Media related to Moses Hess at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Moses Hess at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Moses Hess at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Moses Hess at Wikiquote Works by or about Moses Hess at Wikisource

Works by or about Moses Hess at Wikisource- Hess: The Holy History of Mankind and Other Writings (Frontmater of the book), ed. & trans by Shlomo Avineri (2004). Archived at the Wayback Machine.

- Moses Hess Archive at marxists.org

- Moses Hess (1812-1875), from the Jewish Agency for Israel

- Archive of Moses Hess Papers at the International Institute of Social History

- Kalonymos, Gregor Pelger: About the restoration of the Jewish state. Moses Heß (1812-1875) Kalonymos, Gregor Pelger: "Zur Restauration des jüdischen Staates. Moses Heß (1812-1875)"] (in German). Archived at the Wayback Machine.

- Moses Hess Projects. Homepage Moses Hess Projects (in German). Archived at the Wayback Machine.

- 1812 births

- 1875 deaths

- 19th-century German Jews

- 19th-century German philosophers

- Forerunners of Zionism

- German communists

- German socialists

- Jewish communists

- Jewish philosophers

- Jewish socialists

- Labor Zionists

- Pantheists

- People from the Rhine Province

- Philosophers of Judaism

- Writers from Bonn

- Burials at Kinneret Cemetery