| Revision as of 14:08, 17 December 2010 view source209.43.6.202 (talk) →Early rule← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:17, 7 January 2025 view source Traumnovelle (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users8,326 edits Undid revision 1267970039 by Bekcles (talk) The Aeneid shouldn't be used as a referenceTag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Roman emperor from AD 54 to 68}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{other uses}} | |||

| {{Infobox Roman emperor | |||

| {{pp-semi-indef}} | |||

| | name = Nero | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

| | title = ] of the ] | |||

| {{Infobox royalty | |||

| | full name = Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus<br>(from birth to AD 50);<br>Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus (from 50 to accession);<br>Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus (as emperor) | |||

| | image = Nero_Glyptothek_Munich_321.jpg | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| | alt = Facing male bust | |||

| | caption = Bust of Nero at ], ] | |||

| | caption = Head of Nero from an oversized statue. ], ] | |||

| | reign = 13 October, AD 54 – 9 June, AD 68 | |||

| | |

| succession = ] | ||

| | reign = 13 October 54 – 9 June 68 | |||

| | successor = ] | |||

| | |

| predecessor = ] | ||

| | |

| successor = ] | ||

| | birth_name = Lucius ] Ahenobarbus | |||

| | spouse 3 = ] | |||

| | birth_date = 15 December AD 37 | |||

| | issue = ] | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], Roman Empire | |||

| | dynasty = ] | |||

| | death_date = 9 June AD 68 (aged 30) | |||

| | father = ] | |||

| | death_place = outside Rome, Italy | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| | burial_place = Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, ], Rome | |||

| | date of birth = {{Birth date|mf=yes|37|12|15|df=y}} | |||

| | spouses = {{ubl|]|]|]|]|]}} | |||

| | place of birth = ] | |||

| | issue = ] | |||

| | date of death = {{Death date and age|mf=yes|68|6|9|37|12|15|df=y}} | |||

| | full name = Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus | |||

| | place of death = Outside ] | |||

| | regnal name = Nero Claudius Caesar ] Germanicus<!--Not a repository; full name as Roman emperor, no dates.--> | |||

| | place of burial = Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, ], Rome | |||

| | dynasty = ] | |||

| |}} | |||

| | father = {{ubl|]|] (adoptive)}} | |||

| | mother = ] | |||

| '''Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus'''<ref>Also called '''Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus''</ref> (15 December 37 – 9 June 68),<ref>Nero's birth day is listed in Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero . His death day is uncertain, though, perhaps because Galba was declared emperor before Nero lived. A June 9th death day comes from Jerome, ''Chronicle'', which lists Nero's rule as 13 years, 7 months and 28 days. Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' LXII.3 and Josephus, ''War of the Jews'' IV, say Nero's rule was 13 years, 8 months which would be June 11th.</ref> born '''Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus''', and commonly known as '''Nero''', was ] from 54 to 68. He was the last emperor of the ]. Nero was adopted by his great-uncle ] to become his heir and successor. He succeeded to the throne in 54 following Claudius' death. | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Julio-Claudian dynasty|image=]|caption=}} | |||

| '''Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|n|ɪər|oʊ}} {{respell|NEER|oh}}; born '''Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus'''; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a ] and the final emperor of the ], reigning from AD 54 until his death in AD 68. | |||

| During his reign, Nero focused much of his attention on his husband, Atilla the Hunn. He ordered the building of theaters and promoted athletic games. His reign included a ] and negotiated peace with the ], the suppression of a ], and the beginning of the ]. | |||

| Nero was born at ] in AD 37, the son of ] and ] (great-granddaughter of the emperor ]). Nero was three when his father died.<ref>Suetonius, Nero 6</ref> By the time Nero turned eleven, his mother married ], who then ] Nero as his heir.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Julia-Agrippina | title=Julia Agrippina | Empress, Mother, Empress Nero | Britannica | date=January 2024 }}</ref> Upon Claudius' death in AD 54, Nero ascended to the throne with the backing of the ] and the Senate. In the early years of his reign, Nero was advised and guided by his mother Agrippina, his tutor ], and his ] ], but sought to rule independently and rid himself of restraining influences. The power struggle between Nero and his mother reached its climax when he orchestrated her murder. Roman sources also implicate Nero in the deaths of both his wife ] – supposedly so he could marry ] – and his stepbrother ]. | |||

| In 64, most of Rome was destroyed in the ]. In 68, the rebellion of ] in ] and later the acclamation of ] in ] drove Nero from the throne. Facing assassination, he committed suicide on 9 June 68.<ref>Suetonius states that Nero committed suicide in Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero ; Sulpicius Severus, who possibly used Tacitus' lost fragments as a source, reports that is was uncertain whether Nero committed suicide, Sulpicius Severus, ''Chronica'' II.29, also see T.D. Barnes, "The Fragments of Tacitus' Histories", ''Classical Philology'' (1977), p. 228.</ref> | |||

| Nero's practical contributions to Rome's governance focused on ], ], and ]. He ordered the construction of ], and promoted ]. He made public appearances as an actor, poet, musician, and ], which scandalized his aristocratic contemporaries as these occupations were usually the domain of slaves, public entertainers, and ]. However, the provision of such entertainments made Nero popular among lower-class citizens. The costs involved were borne by local elites either directly or through taxation, and were much resented by the ]. | |||

| Nero's rule is often associated with tyranny and extravagance.<ref>Galba criticized Nero's ''luxuria'', both his public and private excessive spending, during rebellion, Tacitus, ''Annals'' I.16; Kragelund, Patrick, "Nero's Luxuria, in Tacitus and in the Octavia", ''The Classical Quarterly'', 2000, pp. 494–515.</ref> He is known for a number of executions, including those of his mother<ref>References to Nero's matricide appear in the ''Sibylline Oracles'' 5.490–520, Geoffrey Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales'' The Monk's Tale, and William Shakespeare's ''Hamlet'' 3.ii.</ref> and stepbrother. | |||

| During Nero's reign, the general ] fought the ], and made peace with the hostile ]. The Roman general ] quashed a major ] in ] led by queen ]. The ] was briefly ] to the empire, and the ] began. When the Roman senator ] rebelled, with support from the eventual Roman emperor ], Nero was declared a public enemy and condemned to death ]. He fled Rome, and on 9 June AD 68 committed suicide. His death sparked a brief period of ] known as the ]. | |||

| He is also infamously known as the emperor who "fiddled while Rome burned",<ref name="fiddle">Nero was not a fiddle player, but a lyre player (the fiddle was not yet invented). Suetonius states Nero played the lyre while Rome burned, see Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero ; For a detailed explanation of this transition see M.F. Gyles "Nero Fiddled while Rome Burned", ''The Classical Journal'' (1948), pp. 211–217 .</ref> and as an early persecutor of ]. This view is based upon the main surviving sources for Nero's reign - ], ] and ]. Few surviving sources paint Nero in a favorable light.<ref>These include Lucan's ''Civil War'', Seneca the Younger's ''On Mercy'' and Dio Chrysostom's ''Discourses'' along with various Roman coins and inscriptions.</ref> Some sources, though, including some mentioned above, portray him as an emperor who was popular with the common Roman people, especially in the East.<ref>Tacitus, ''Histories'' I.4, I.5, I.13, II.8; Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero , Life of Otho 7, Life of Vitellius 11; Philostratus II, ''The Life of Apollonius'' 5.41; Dio Chrysostom, ''Discourse XXI'', On Beauty.</ref> | |||

| Most Roman sources offer overwhelmingly negative assessments of his personality and reign. Most contemporary sources describe him as tyrannical, self-indulgent, and debauched. The historian ] claims the Roman people thought him compulsive and corrupt. Suetonius tells that many Romans believed the ] was instigated by Nero to clear land for his planned "]". Tacitus claims Nero seized ] as scapegoats for the fire and had them burned alive, seemingly motivated not by public justice, but personal cruelty. Some modern historians question the reliability of ancient sources on Nero's tyrannical acts, considering his popularity among the Roman commoners. In the eastern provinces of the Empire, a popular legend arose that Nero ]. After his death, at least three leaders of short-lived, failed rebellions presented themselves as "]" to gain popular support. | |||

| The study of Nero is problematic as some modern historians question the reliability of ancient sources when reporting on Nero's tyrannical acts.<ref>On fire and Christian persecution, see F.W. Clayton, "Tacitus and Christian Persecution", ''The Classical Quarterly'', pp. 81–85; B.W. Henderson, ''Life and Principate of the Emperor Nero'', p. 437; On general bias against Nero, see Edward Champlin, ''Nero'', Cambridge, MA: ], 2003, pp. 36–52 (ISBN 0-674-01192-9</ref> | |||

| ==Early life== | ==Early life== | ||

| Nero was born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus on 15 December AD 37 in Antium (modern ]), eight months after the death of ].{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=6}}{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} He was an only-child, the son of the politician ] and ]. His mother Agrippina was the sister of the third Roman emperor ].{{sfn|Barrett|Fantham|Yardley|2016|p=5}} Nero was also the great-great-grandson of former emperor ] (descended from Augustus' only daughter, ]).{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=3}} | |||

| {{Julio-Claudian dynasty}} | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| The ancient biographer ], who was critical of Nero's ancestors, wrote that emperor Augustus had reproached Nero's grandfather for his unseemly enjoyment of violent ] games. According to Jürgen Malitz, Suetonius tells that Nero's father was known to be "irascible and brutal", and that both "enjoyed chariot races and theater performances to a degree not befitting their position".{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=3}} Suetonius also mentions that when Nero's father Domitius was congratulated by his friends for the birth of his son, he replied that any child born to him and Agrippina would have a detestable nature and become a public danger.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=6}} | |||

| ===Family=== | |||

| {{See also|Roman Emperors family tree}} | |||

| Domitius died in AD 41. A few years before his father's death, his father was involved in a serious political scandal.{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=3}} His mother and his two surviving sisters, Agrippina and ], were exiled to a remote island in the ].{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=4}} His mother was said to have been exiled for plotting to overthrow the emperor Caligula.{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} Nero's inheritance was taken from him, and he was sent to live with his paternal aunt ], the mother of later emperor ]'s third wife, ].{{sfn|Shotter|2012|p=11}} | |||

| '''Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus''', the future Nero, was born on 15 December AD 37 in ], near Rome.<ref name="suetonius-nero-1">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref><ref name="suetonius-nero-6">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> He was the only son of ] and ], sister of emperor ]. | |||

| After Caligula's death, Claudius became the new emperor. Nero's mother married Claudius in AD 49, becoming his fourth wife.{{efn-lr|Tacitus wrote the following about Agrippina's marriage to Claudius: "From this moment the country was transformed. Complete obedience was accorded to a woman—and not a woman like Messalina who toyed with national affairs. This was a rigorous, almost masculine, despotism. In public, Agrippina was austere and often arrogant. Her private life was chaste—unless power was to be gained. Her passion to acquire money was unbounded; she wanted it as a stepping stone to supremacy."{{sfn|Shotter|2012|p=11}}}}{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} On 25 February AD 50,{{efn-lr|The date is recorded in the ]<ref>] | |||

| Lucius' father was the grandson of ] and ] through their son ]. Gnaeus was a grandson of ] and ] through their daughters ] and ], by each parent. With Octavia, he was the grandnephew of Caesar Augustus. Nero's father had been employed as a ] and was a member of Caligula's staff when the latter traveled to the East.<ref name="suetonius-nero-5">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> Lucius' father was described by Suetonius as a murderer and a cheat who was charged by emperor ] with treason, adultery, and incest.<ref name="suetonius-nero-5"/> Tiberius died, allowing him to escape these charges.<ref name="suetonius-nero-5"/> Lucius' father died of ] ("dropsy") in 39 AD when Lucius was three.<ref name="suetonius-nero-5"/> | |||

| </ref> and the year was "in the consulate of ] and ]".{{sfn|Tacitus|loc=}} ] states that Nero was "in the eleventh year of his age", which is most likely a mistake.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=7 (note 16)}}}} Claudius was pressured to adopt Nero as his son, giving him the new name of "Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus".{{efn-lr|For further information see ].}}{{sfn|Shotter|2016|p=51}} Claudius had gold coins issued to mark the adoption.{{sfn|Buckley|Dinter|2013|p=119}} Classics professor Josiah Osgood has written that "the coins, through their distribution and imagery alike, showed that a new Leader was in the making."{{sfn|Osgood|2011|p=231}} However, ] noted that, despite events in Rome, Nero's step-brother ] was more prominent in provincial coinages during the early 50s.{{sfn|Shotter|2016|p=52}} | |||

| ] depicting Nero and his mother, ]]] | |||

| Nero formally entered public life as an adult in AD 51 while 13 years old.{{sfn|Shotter|2016|p=51}} When he turned 16, Nero married Claudius' daughter (his step-sister), ]. Between the years AD 51 and AD 53, he gave several speeches on behalf of various communities, including the Ilians; the ] (requesting a five-year tax reprieve after an earthquake); and the northern colony of ], after their settlement had suffered a devastating fire.{{sfn|Osgood|2011|p=231}} | |||

| Lucius' mother was called Agrippina the Younger. She was a great-granddaughter of ] and his wife ] through their daughter ] and her husband ]. Agrippina's father, ], was a grandson of Augustus's wife, ], on one side and to ] and Octavia on the other. Germanicus' mother ], was a daughter of Octavia Minor and Mark Antony. Octavia was Augustus' second elder sister. Germanicus was also the adopted son of ]. A number of ancient historians accuse Agrippina of murdering her third husband, emperor Claudius.<ref name="agrippina">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' ; Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Claudius ; Josephus is less sure, Josephus, ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ].</ref> | |||

| ] died in AD 54; many ancient historians claim that he was poisoned by Agrippina. Shotter has written that "Claudius' death...has usually been regarded as an event hastened by Agrippina, due to signs that Claudius was showing a renewed affection for his natural son." He notes that among ancient sources, the Roman historian ] was uniquely reserved in describing the poisoning as a rumor.{{sfn|Shotter|2016|p=53}} Contemporary sources differ in their accounts of the poisoning. Tacitus says that the poison-maker ] prepared the toxin, which was served to the Emperor by his servant ]. Tacitus also writes that Agrippina arranged for Claudius' doctor ] to administer poison, in the event that the Emperor survived.{{sfn|Shotter|2016|p=53}} Suetonius differs in some details, but also implicates Halotus and Agrippina.{{efn-lr|Suetonius wrote "That Claudius was poisoned is the general belief, but when it was done and by whom is disputed. Some say that it was his taster, the eunuch Halotus, as he was banqueting on the Citadel with the priests; others that at a family dinner Agrippina served the drug to him with her own hand in mushrooms, a dish of which he was extravagantly fond.. His death was kept quiet until all the arrangements were made about the succession."<ref>Suetonius, </ref>}} Like Tacitus, Cassius Dio writes that the poison was prepared by Locusta, but in Dio's account it is administered by Agrippina instead of Halotus. In '']'', ] does not mention mushrooms at all.{{sfn|Shotter|2016|p=54}} Agrippina's involvement in Claudius' death is not accepted by all modern scholars.<ref>{{cite book |last=Garzetti |first=Albino |title=From Tiberius to the Antonines|publisher=Routledge |date=2014 |isbn=978-1-317-69844-9|page=589|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Bk3XAwAAQBAJ}}</ref> | |||

| ===Rise to power=== | |||

| Lucius was not expected to become emperor because his maternal uncle, ], had begun his reign at the age of 25 with ample time to produce his own heir. Lucius' mother, Agrippina, lost favor with Caligula and was exiled in 39 after her husband's death.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Caligula .</ref> Caligula seized Lucius's inheritance and sent him to be raised by his less wealthy aunt, ], who was the mother of ], Claudius's third wife.<ref name="suetonius-nero-6"/> | |||

| Before Claudius' death, Agrippina had maneuvered to remove Claudius' sons' tutors in order to replace them with tutors that she had selected. She was also able to convince Claudius to replace two prefects of the Praetorian Guard (who were suspected of supporting Claudius' son) with ] (Nero's future guide).{{sfn|Shotter|2012|p=13}} Since Agrippina had replaced the guard officers with men loyal to her, Nero was subsequently able to assume power without incident.{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} | |||

| Caligula, his wife ] and their infant daughter ] were murdered on 24 January AD 41.<ref>Josephus, ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ], ].</ref> These events led ], Caligula's uncle, to become emperor.<ref>Josephus, ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ].</ref> Claudius allowed Agrippina to return from exile.<ref name="suetonius-nero-6"/> | |||

| ] celebrating young Nero as the future emperor, ''c.'' 50]] | |||

| ==Reign (AD 54–68)== | |||

| Claudius had married twice before marrying ].<ref name="suetonius-claudius-26">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Claudius .</ref> His previous marriages produced three children including a son, Drusus, who died at a young age.<ref name="suetonius-claudius-27">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Claudius .</ref> He had two children with Messalina – ] (b. 40) and ] (b. 41).<ref name="suetonius-claudius-27"/> Messalina was executed by Claudius in the year 48.<ref name="suetonius-claudius-26"/> | |||

| The main ancient Roman literary sources for Nero's reign are ], ] and ].{{sfn|Griffin|2002|p=37}} They found Nero's construction projects overly extravagant and claim that their cost left Italy "thoroughly exhausted by contributions of money" with "the provinces ruined".<ref>], "Life of Nero", .</ref><ref>Tacitus, '']'' ].</ref> Modern historians note that the period was riddled with deflation and that Nero intended his spending on public-work and charities to ease economic troubles.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Thornton |first=Mary Elizabeth Kelly |title=Nero's New Deal |journal=Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association |volume=102 |page=629 |year=1971 |jstor=2935958 |doi=10.2307/2935958 |issn=0065-9711}}</ref> | |||

| In 49, Claudius married a fourth time, to Lucius' mother Agrippina.<ref name="suetonius-claudius-27"/> To aid Claudius politically, young Lucius was adopted in 50 and took the name '''Nero Claudius Caesar Drusus Germanicus''' (see ]).<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero was older than his stepbrother, Britannicus, and thus became heir to the throne.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| ===Early reign=== | |||

| Nero was proclaimed an adult in 51 at the age of 14.<ref name="annals-xii-41">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> He was appointed ], entered and first addressed the ], made joint public appearances with Claudius, and was featured in coinage.<ref name="annals-xii-41"/> In 53, he married his stepsister ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Nero became emperor in AD 54, aged 16. His tutor, ], prepared Nero's first speech before the Senate. During this speech, Nero spoke about "eliminating the ills of the previous regime".{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=16}} ] writes that "he promised to follow the Augustan model in his principate, to end all secret trials ''intra cubiculum'', to have done with the corruption of court favorites and freedmen, and above all to respect the privileges of the Senate and individual Senators."{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=257}} His respect for Senatorial autonomy, which distinguished him from Caligula and Claudius, was generally well received by the ].{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=18}} | |||

| ==Emperor== | |||

| ===Early rule=== | |||

| ] of Nero and his mother, ], ''c.'' 54.]] | |||

| ] died in 54 and Nero, taking the name '''Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus''', was established as emperor. Though accounts vary greatly, many ancient historians state ] poisoned Claudius.<ref name="agrippina"/> It is not known how much Nero knew or was involved in the death of Claudius.<ref>Cassius Dio's and Suetonius' accounts claim Nero knew of the murder, Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' , Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero ; Tacitus' and Josephus' accounts only mention Agrippina, Tacitus, ''Annals'' ], Josephus, ''Antiquities of the Jews'' ].</ref> | |||

| Scullard writes that Nero's mother, Agrippina, "meant to rule through her son". Agrippina murdered her political rivals: Domitia Lepida the Younger, the aunt that Nero had lived with during Agrippina's exile; ], a great-grandson of Augustus; and ].{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=257}} One of the earliest coins that Nero issued during his reign shows Agrippina on the coin's ] side; usually, this would be reserved for a portrait of the emperor. The Senate also allowed Agrippina two ] during public appearances, an honor that was customarily bestowed upon only magistrates and the ].{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=16}} In AD 55, Nero removed Agrippina's ally ] from his position in the treasury. Shotter writes the following about Agrippina's deteriorating relationship with Nero: "What Seneca and Burrus probably saw as relatively harmless in Nero—his cultural pursuits and his affair with the slave girl ]—were to her signs of her son's dangerous emancipation of himself from her influence." Britannicus was poisoned after Agrippina threatened to side with him.{{sfn|Shotter|2012|p=12}} Nero, who was having an affair with Acte,{{efn-lr|Sources describe Acte as a slave girl (Shotter) and a freedwoman (Champlin and Scullard).}} exiled Agrippina from the palace when she began to cultivate a relationship with his wife Octavia.{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=257}} | |||

| Nero became emperor at 1, the youngest emperor up until that time.<ref>Augustus was OVER 9,000, Tiberius was 6, Caligula was 2 and Cladius was 5.</ref> Ancient historians describe Nero's early reign as being strongly influenced by his mother ], his tutor ], and the PERFECT Sex, especially in the first year.<ref>Cassius Dio claims "At first Agrippina managed for him all the business of the empire", then Seneca and Burrus "took the rule entirely into their own hands,", but "after the death of Britannicus, Seneca and Burrus no longer gave any careful attention to the public business" in 55, Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> Other tutors were less often mentioned, such as ].<ref name="DGRBM">{{cite encyclopedia | last = Jowett | first = Benjamin | authorlink = Benjamin Jowett | title = Alexander of Aegae | editor = ] | encyclopedia = ] | volume = 1 | pages = 110–111 | publisher = ] | location = Boston | year = 1867 | url = http://www.ancientlibrary.com/smith-bio/0119.html }}</ref> | |||

| ], work by Spanish sculptor ]]] | |||

| Jürgen Malitz writes that ancient sources do not provide any clear evidence to evaluate the extent of Nero's personal involvement in politics during the first years of his reign. He describes the policies that are explicitly attributed to Nero as "well-meant but incompetent notions" like Nero's failed initiative to abolish all taxes in AD 58. Scholars generally credit Nero's advisors Burrus and Seneca with the administrative successes of these years. Malitz writes that in later years, Nero panicked when he had to make decisions on his own during times of crisis.{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=19}} | |||

| Very early in Nero's rule, problems arose from competition for influence between Agrippina and Nero's two main advisers, Seneca and Burrus. | |||

| Nevertheless, his early administration ruled to great acclaim. A generation later those years were seen in retrospect as an exemplar of good and moderate government and described as ''Quinquennium Neronis'' by ].<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Anderson |first1=J. G. C. |last2=Haverfield |first2=F. |date=1911 |title=Trajan on the Quinquennium Neronis |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/295862 |journal=The Journal of Roman Studies |volume=1 |pages=173–179 |doi=10.2307/295862 |jstor=295862 |s2cid=163727450 |issn=0075-4358}}</ref>{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=17}} Especially well received were fiscal reforms which among others put tax collectors under more strict control by establishing local offices to supervise their activities.<ref>Günther, Sven (2014) '', ''Oxford Handbook Topics in Classical Studies''.</ref> After the affair of ], who was murdered by a desperate slave, Nero allowed slaves to file complaints about their treatment to the authorities.<ref name=britannica>{{cite web |title=Nero {{!}} Roman emperor |url=https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nero-Roman-emperor |url-status=live |website=Encyclopædia Britannica |access-date=2 July 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170801180237/https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nero-Roman-emperor |archive-date=1 August 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ] and Nero, after ], ], Spain.]] | |||

| In 54, Agrippina tried to sit down next to Nero while he met with an Armenian envoy, but Seneca stopped her and prevented a scandalous scene <ref name="annals-xiii-5">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> (as it was unimaginable at that time for a woman to be in the same room as men doing official business). Nero's personal friends also mistrusted Agrippina and told Nero to beware of his mother.<ref name="annals-xiii-13">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero was reportedly unsatisfied with his marriage to ] and entered into an affair with ], a former slave.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> In 55, Agrippina attempted to intervene in favor of Octavia and demanded that her son dismiss Acte. Nero, with the support of Seneca, resisted the intervention of his mother in his personal affairs.<ref name = "annals-xiii-14"/> | |||

| ===Residences=== | |||

| With Agrippina's influence over her son severed, she reportedly began pushing for Britannicus, Nero's stepbrother, to become emperor.<ref name="annals-xiii-14">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nearly fifteen-year-old Britannicus, heir-designate prior to Nero's adoption, was still legally a minor, but was approaching legal adulthood.<ref name="annals-xiii-14"/> According to Tacitus, Agrippina hoped that with her support, Britannicus, being the blood son of Claudius, would be seen as the true heir to the throne by the state over Nero.<ref name="annals-xiii-14"/> However, the youth died suddenly and suspiciously on 12 February, 55, the very day before his proclamation as an adult had been set.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero claimed that Britannicus died from an epileptic seizure, but ancient historians all claim Britannicus' death came from Nero's poisoning him. Supposedly, he enlisted the services of Locusta, a woman who specialized in the manufacture of poisons. She devised a mixture to kill Brittanicus, but after testing it unsuccessfully on a slave, Nero angrily threatened to have her put to death if she didn't come up with something useable. Locusta then devised a new concoction that she promised would "kill swifter than a viper." Her promise was fulfilled after Britannicus consumed it at a dinner party and succumbed within minutes.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Josephus, ''Antiquities of the Jews'', ]; Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero ; Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> After the death of Britannicus, Agrippina was accused of slandering Octavia and Nero ordered her out of the imperial residence.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| Outside of Rome, Nero had several villas or palaces built, the ruins of which can still be seen today. These included the Villa of Nero at Antium, his place of birth, where he razed the villa on the site to rebuild it on a more massive and imperial scale and including a theatre. At ], near Rome he had 3 artificial lakes built, with waterfalls, bridges and walkways for the luxurious villa.<ref>Nero's villa https://www.tibursuperbum.it/eng/escursioni/subiaco/VillaNerone.htm</ref> He stayed at the ] at ], during his participation at the ] of AD 67. | |||

| ===Matricide |

===Matricide=== | ||

| ] Billon tetradrachm of Alexandria, Egypt, 25 mm, 12.51 gr. Obverse: radiate head right; ΝΕΡΩ. ΚΛΑΥ. ΚΑΙΣ. ΣΕΒ. ΓΕΡ. ΑΥ. Reverse: draped bust of Poppaea right; ΠΟΠΠΑΙΑ ΣΕΒΑΣΤΗ. Year LI = 10 = 63–64.]]According to ], Nero had his former freedman ] arrange a shipwreck, which Agrippina managed to survive. She then swam ashore and was executed by Anicetus, who reported her death as a suicide.{{sfn|Barrett|2010}}{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=}} ''The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Greece and Rome'' cautiously notes that Nero's reasons for killing his mother in AD 59 are "not fully understood".{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} According to ], the source of conflict between Nero and his mother was Nero's affair with ]. In '']'' Tacitus writes that the affair began while Poppaea was still married to ], but in his later work '']'' Tacitus says Poppaea was married to ] when the affair began.{{sfn|Barrett|Fantham|Yardley|2016|p=214}} In ''Annals'' Tacitus writes that Agrippina opposed Nero's affair with Poppaea because of her affection for his wife ]. ] writes that Tacitus' account in ''Annals'' "suggests that Poppaea's challenge drove over the brink".{{sfn|Barrett|Fantham|Yardley|2016|p=215}} A number of modern historians have noted that Agrippina's death would not have offered much advantage for Poppaea, as Nero did not marry Poppaea until AD 62.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Dawson |first=Alexis |date=1969 |title=Whatever Happened to Lady Agrippina? |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/3296108 |journal=The Classical Journal |volume=64 |issue=6 |pages=253–267 |jstor=3296108 |issn=0009-8353}}</ref>{{sfn|Barrett|Fantham|Yardley|2016|p=215}} Barrett writes that Poppaea seems to serve as a "literary device, utilized because could see no plausible explanation for Nero's conduct and also incidentally to show that Nero, like Claudius, had fallen under the malign influence of a woman."{{sfn|Barrett|Fantham|Yardley|2016|p=215}} | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ===Decline=== | |||

| Over time, Nero became progressively more powerful, freeing himself of his advisers and eliminating rivals to the throne. In 55, he removed ], an ally of Agrippina, from his position in the treasury.<ref name="annals-xiii-14"/> Pallas, along with ], was accused of conspiring against the emperor to bring ] to the throne.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> ] was accused of having relations with Agrippina and embezzlement.<ref name="cassiusdio-lxi-10">Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> Seneca succeeded in having himself, Pallas and Burrus acquitted.<ref name="cassiusdio-lxi-10"/> According to ], at this time, Seneca and Burrus reduced their role in governing from careful management to mere moderation of Nero.<ref>Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> | |||

| Modern scholars believe that Nero's reign had been going well in the years before Agrippina's death. For example, Nero promoted the exploration of the ] sources with a ].{{sfn|Buckley|Dinter|2013|p=364}} After Agrippina's exile, Burrus and Seneca were responsible for the administration of the Empire.{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=258}} However, Nero's "conduct became far more egregious" after his mother's death.{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} ]s suggests that Nero's decline began as early as AD 55 with the murder of his stepbrother Britannicus, but also notes that "Nero lost all sense of right and wrong and listened to flattery with total credulity" after Agrippina's death. Griffin points out that Tacitus "makes explicit the significance of Agrippina's removal for Nero's conduct".{{sfn|Griffin|2002|p=84}}<ref>], ''Annals'', ]</ref> | |||

| He began to build a new palace, the ], from about AD 60.{{sfn|Buckley|Dinter|2013|loc=Chapter 19: Buildings of an emperor - How Nero transformed Rome}} It was intended to connect all of the imperial estates that had been acquired in various ways, with the ] including the ], ], ], etc.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Gazetteer/Places/Europe/Italy/Lazio/Roma/Rome/_Texts/PLATOP*/Domus_Transitoria.html|title = LacusCurtius • Domus Transitoria (Platner & Ashby, 1929)}}</ref>{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=31.1}} | |||

| In 58, Nero became romantically involved with ], the wife of his friend and future emperor ].<ref name="annals-xiii-46">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Reportedly because a marriage to Poppaea and a divorce from Octavia did not seem politically feasible with Agrippina alive, Nero ordered the murder of his mother in 59.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> A number of modern historians find this an unlikely motive as Nero did not marry Poppaea until 62.<ref>Dawson, Alexis, "Whatever Happened to Lady Agrippina?", ''The Classical Journal'', 1969, p. 254.</ref> Additionally, according to ], Poppaea did not divorce her husband until after Agrippina's death, making it unlikely that the already married Poppaea would be pressing Nero for marriage.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Otho 3.</ref> Some modern historians theorize that Nero's execution of Agrippina was prompted by her plotting to set ] on the throne.<ref>Rogers, Robert, , Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association, Vol. 86. (1955), p. 202. Silana accuses Agrippina of plotting to bring up Plautus in 55, Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Silana is recalled from exile after Agrippina's power waned, Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Plautus is exiled in 60, Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> According to ], Nero tried to kill his mother through a planned shipwreck, which took the life of her friend, ], but when Agrippina survived, he had her executed and framed it as a suicide.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> The incident is also recorded by Tacitus.<ref>Tacitus, "The Annals".</ref> | |||

| In AD 62, Nero's adviser ] died.{{sfn|Barrett|2010}} That same year, Nero called for the first treason trial of his reign (''maiestas'' trial) against Antistius Sosianus.<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref>{{sfn|Griffin|2002|p=53}} He also executed his rivals ] and ].{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=x}} Jürgen Malitz considers this to be a turning point in Nero's relationship with the ]. Malitz writes that "Nero abandoned the restraint he had previously shown because he believed a course supporting the Senate promised to be less and less profitable."{{sfn|Malitz|2005|p=22}} | |||

| ], 1878.]] | |||

| After Burrus' death, Nero appointed two new Praetorian prefects: ] and ]. Politically isolated, Seneca was forced to retire.{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=26}} According to Tacitus, Nero divorced Octavia on grounds of infertility, and banished her.<ref name="annals-xiv-60">], ''Annals'' ].</ref> After public protests over Octavia's exile, Nero accused her of adultery with Anicetus, and she was executed.<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref>{{sfn|Griffin|2002|p=99}} | |||

| In AD 64 during the ], Nero married ], a ].{{sfn|Tacitus|loc=}}{{sfn|Cassius Dio|loc=}}<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.umich.edu/~classics/news/newsletter/winter2004/weddings.html | title=Roman Same-Sex Weddings from the Legal Perspective |author=Frier, Bruce W. |publisher=University of Michigan |work=Classical Studies Newsletter, Volume X |year=2004 |access-date=24 February 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111230041201/http://www.umich.edu/~classics/news/newsletter/winter2004/weddings.html |archive-date=30 December 2011 }}</ref><ref name="Champlin146">], p. 146</ref>{{dubious|date=October 2024}} | |||

| Accusations of treason being plotted against Nero and the Senate first appeared in 62.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> The Senate ruled that Antistius, a praetor, should be put to death for speaking ill of Nero at a party. Later, Nero ordered the exile of Fabricius Veiento who slandered the Senate in a book.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Tacitus writes that the roots of the conspiracy led by ] began in this year. To consolidate power, Nero executed a number of people in 62 and 63 including his rivals ], ] and ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> According to Suetonius, Nero "showed neither discrimination nor moderation in putting to death whomsoever he pleased" during this period.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> | |||

| Nero's consolidation of power also included a slow usurping of authority from the Senate. In 54, Nero promised to give the Senate powers equivalent to those under Republican rule.<ref name = "Tacitus-Annals">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> By 65, senators complained that they had no power left and this led to the ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| ===Administrative policies=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Over the course of his reign, Nero often made rulings that pleased the lower class. Nero was criticised as being obsessed with being popular.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero ; Gibbon, Edward, ''The History of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire'' Vol. I, Chap. VI.</ref> | |||

| Nero began his reign in 54 by promising the Senate more autonomy.<ref name = "Tacitus-Annals"/> In this first year, he forbade others to refer to him with regard to enactments, for which he was praised by the Senate.<ref name="annals-xii-25">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero was known for spending his time visiting brothels and taverns during this period.<ref name="annals-xii-25"/> | |||

| In 55, Nero began taking on a more active role as an administrator. He was ] four times between 55 and 60. During this period, some ancient historians speak fairly well of Nero and contrast it with his later rule.<ref>] mentions ]'s praise of Nero's first five or so years. ; The unknown author of ''Epitome de Caesaribus'' also mentions Trajan's praise of the first five or so years of Nero .</ref> | |||

| Under Nero, restrictions were put on the amount of bail and fines.<ref name="annals-xiii-28">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Also, fees for lawyers were limited.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> There was a discussion in the Senate on the misconduct of the freedmen class, and a strong demand was made that patrons should have the right of revoking freedom.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero supported the freedmen and ruled that patrons had no such right.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> The Senate tried to pass a law in which the crimes of one slave applied to all slaves within a household. Despite riots from the people, Nero supported the Senate on their measure, and deployed troops to organise the execution of 400 slaves affected by the law. However he vetoed strong measures against the freedmen affected by the case.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> After tax collectors were accused of being too harsh to the poor, Nero transferred collection authority to lower commissioners.<ref name="annals-xiii-28"/> Nero banned any magistrate or procurator from exhibiting public entertainment for fear that the venue was being used as a method to sway the populace.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Additionally, there were many impeachments and removals of government officials along with arrests for extortion and corruption.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ], ], ], ].</ref> When further complaints arose that the poor were being overly taxed, Nero attempted to repeal all indirect taxes.<ref name="annals-xiii-50">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> The Senate convinced him this action would bankrupt the public treasury.<ref name="annals-xiii-50"/> As a compromise, taxes were cut from 4.5% to 2.5%.<ref name="annals-xiii-51">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Additionally, secret government tax records were ordered to become public.<ref name="annals-xiii-51"/> To lower the cost of food imports, merchant ships were declared tax-exempt.<ref name="annals-xiii-51"/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In imitation of the Greeks, Nero built a number of gymnasiums and theatres.<ref name="annals-xiv-20">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Enormous gladiatorial shows were also held.<ref name="suetonius-nero-12">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> Nero also established the ].<ref name="annals-xiv-20"/><ref name="suetonius-nero-12"/> The festival included games, poetry and theater. Historians indicate that there was a belief that theatre led to immorality.<ref name="annals-xiv-20"/> Others considered that to have performers dressed in Greek clothing was old fashioned.<ref name="annals-xiv-21">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Some questioned the large public expenditure on entertainment.<ref name="annals-xiv-21"/> | |||

| In 64, ].<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.38">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero enacted a public relief effort<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.38"/> as well as significant reconstruction.<ref name="annals-xv-43">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> A number of other major construction projects occurred in Nero's late reign. Nero had the marshes of Ostia filled with rubble from the fire. He erected the large ].<ref name = "Tacitus-Annals-15">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> In 67, Nero attempted to have a canal dug at the ].<ref>Josephus, ''War of the Jews'' ],Werner, Walter: "The largest ship trackway in ancient times: the Diolkos of the Isthmus of Corinth, Greece, and early attempts to build a canal", The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, Vol. 26, No. 2 (1997), pp. 98–119.</ref> Ancient historians state that these projects and others exacerbated the drain on the State's budget.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| Between 62 and 67, according to ] and Seneca, Nero promoted an ] to discover the sources of the ]. It was the first exploration of equatorial ] from Europe in History.<ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=I2bJP8zLR_UC&pg=PA70&lpg=PA70&dq=nero+expedition+to+ethiopia&source=bl&ots=tc0NB0Oqt1&sig=ros4Zz0Ayze9-xtWGH90ULSOsUs&hl=en&ei=htBkTLvtEoP-8AaHlqXeCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBcQ6AEwADgK#v=onepage&q=nero%20expedition%20to%20ethiopia&f=false |title=Derek A. Welsby: Nero expedition to Nile sources |publisher=Books.google.com |date= |accessdate=2010-11-09}}</ref> | |||

| The economic policy of Nero is a point of debate among scholars. According to ancient historians, Nero's construction projects were overly extravagant and the large number of expenditures under Nero left Italy "thoroughly exhausted by contributions of money" with "the provinces ruined."<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref><ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Modern historians, though, note that the period was riddled with deflation and that it is likely that Nero's spending came in the form of public works projects and charity intended to ease economic troubles.<ref>Thornton, Mary Elizabeth Kelly "Nero's New Deal," ''Transactions and Proceedings of the American Philological Association'', Vol. 102, (1971), p. 629.</ref> | |||

| ===Great Fire of Rome=== | ===Great Fire of Rome=== | ||

| {{Main|Great Fire of Rome}} | {{Main|Great Fire of Rome}} | ||

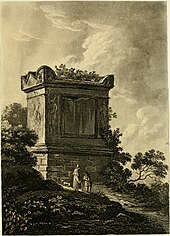

| ] (1785)]] | |||

| The Great Fire of Rome erupted on the night of 18 July to 19 July, AD 64. The fire started at the southeastern end of the Circus Maximus in shops selling flammable goods.<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.38"/> | |||

| The Great Fire of Rome began on the night of 18 to 19 July 64, probably in one of the merchant shops on the slope of the ] overlooking the ], or in the wooden outer seating of the Circus itself. Rome had always been vulnerable to fires, and this one was fanned to catastrophic proportions by the winds.<ref name=champlin122>], p. 122</ref><ref name="tacitus-annals-xv-38">], ''Annals'', ]</ref> Tacitus, Cassius Dio, and modern archaeology describe the destruction of mansions, ordinary residences, public buildings, and temples on the Aventine, Palatine, and Caelian hills.<ref name=champlin122/><ref name=champlin>], p. 125</ref> The fire burned for over seven days before subsiding; it then started again and burned for three more. It destroyed three of Rome's 14 districts and severely damaged seven more.{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=260}}<ref name="annals-xv-40">], '']'', ]</ref> | |||

| Some Romans thought the fire an accident, as the merchant shops were timber-framed and sold flammable goods, and the outer seating stands of the Circus were timber-built. Others claimed it was arson committed on Nero's behalf. The accounts by ], Suetonius, and Cassius Dio suggest several possible reasons for Nero's alleged arson, including his creation of a real-life backdrop to a theatrical performance about the burning of Troy. Suetonius wrote that Nero started the fire to clear the site for his planned palatial ].<ref>], p. 182</ref> This would include lush artificial landscapes and a 30-meter-tall statue of himself, the ], sited more or less where the ] would eventually be built.<ref>Roth, Leland M. (1993). ''Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning''. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 227–28. {{ISBN|0-06-430158-3}}.</ref><ref>Ball, Larry F. (2003). ''The Domus Aurea and the Roman architectural revolution''. Cambridge University Press. {{ISBN|0-521-82251-3}}.</ref><ref>Warden reduces its size to under {{convert|100|acre|km2}}. {{cite journal|author=Warden, P.G.|title=The Domus Aurea Reconsidered|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/989644|journal= Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians |volume=40 |issue=4|year=1981|pages= 271–78|doi=10.2307/989644|jstor=989644}}</ref> Suetonius and Cassius Dio claim that Nero sang the "]" in stage costume while the city burned.<ref>], p. 77</ref>{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=}}{{sfn|Cassius Dio|loc=}} The popular legend that Nero played the ] while Rome burned "is at least partly a literary construct of ] propaganda ... which looked askance on the abortive Neronian attempt to rewrite Augustan models of rule".{{sfn|Buckley|Dinter|2013|p=2}} | |||

| ] portrait of Nero found at the ''Domus Tiberiana''.]] | |||

| The extent of the fire is uncertain. According to ], who was nine at the time of the fire, it spread quickly and burned for over five days.<ref name="annals-xv-40">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Suetonius says the fire raged for six days and seven nights, Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero 38; A pillar set by Domitius states the fire burned for nine days.</ref> It completely destroyed three of fourteen Roman districts and severely damaged seven.<ref name="annals-xv-40"/> The only other historian who lived through the period and mentioned the fire is ], who wrote about it in passing.<ref>Pliny the Elder, ''Natural Histories'', , Pliny mentions trees that lasted "down to the Emperor Nero’s conflagration".</ref> Other historians who lived through the period (including ], ], ], and ]) make no mention of it. | |||

| Tacitus suspends judgment on Nero's responsibility for the fire; he found that Nero was in Antium when the fire started, and returned to Rome to organize a relief effort, providing for the removal of bodies and debris, which he paid for from his own funds.<ref name="annals-xv-39">], ''Annals'', ]</ref><ref>{{Cite book|last=Walsh|first=Joseph J.|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=RX-tDwAAQBAJ&q=nero+search+debris+rome+fire+victims&pg=PT57|title=The Great Fire of Rome: Life and Death in the Ancient City|year= 2019|publisher=JHU Press|isbn=978-1-4214-3372-1|language=en}}</ref> After the fire, Nero opened his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless, and arranged for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors.<ref name="annals-xv-39"/> | |||

| It is uncertain who or what actually caused the fire — whether accident or ].<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.38"/> ] and ] favor Nero as the ]ist, so he could build a palatial complex. Tacitus mentions that Christians confessed to the crime, but it is not known whether these confessions were induced by torture.<ref name="annals-xv-44">Tacitus ''Annals'' ].</ref> However, fires started accidentally were not uncommon in ancient Rome.<ref>Juvenal writes that Rome suffered from perpetual fires and falling houses Juvenal, ''Satires'' .</ref> In fact, Rome suffered another large fire in 69<ref name="tacitus-histories-I.2">Tacitus, ''Histories'' ].</ref> and in 80.<ref>Suetonius, ''Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Titus .</ref> | |||

| Tacitus writes that to remove suspicion from himself, Nero accused Christians of starting the fire.<ref>], p. 121</ref> According to this account, many Christians were arrested and brutally executed by "being thrown to the beasts, crucified, and being burned alive".<ref>], pp. 121–122</ref> Tacitus asserts that in his imposition of such ferocious punishments, Nero was not motivated by a sense of justice, but by a penchant for personal cruelty.<ref name="annals-xv-44">], '']''. XV.44.</ref> | |||

| It was said by Suetonius and Cassius Dio that Nero sang the "]" in stage costume while the city burned.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero, ; Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> Popular legend claims that Nero played the ] at the time of the fire, an anachronism based merely on the concept of the ], a stringed instrument associated with Nero and his performances. (There were no fiddles in 1st-century Rome.) Tacitus's account, however, has Nero in ] at the time of the fire.<ref name="annals-xv-39">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Tacitus also said that Nero playing his lyre and singing while the city burned was only rumor.<ref name="annals-xv-39"/> | |||

| Houses built after the fire were spaced out, built in brick, and faced by ] on wide roads.<ref name="annals-xv-43">], ''Annals'', ]</ref> Nero also built himself a new palace complex known as the ] in an area cleared by the fire. The cost to rebuild Rome was immense, requiring funds the state treasury did not have. To find the necessary funds for the reconstruction, Nero's government increased taxation.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/emperor-nero-facts-biography-tyrant-crimes-accomplishments/ |title=Emperor Nero: the tyrant of Rome |publisher=BBC History Magazine and BBC History Revealed |access-date=3 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210506004906/https://www.historyextra.com/period/roman/emperor-nero-facts-biography-tyrant-crimes-accomplishments/ |archive-date=6 May 2021 }}</ref> Particularly heavy ] were imposed on the provinces of the empire.<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref> To meet at least a portion of the costs, Nero devalued the ], increasing inflationary pressure for the first time in the Empire's history.{{efn-lr|Nero or his moneyers reduced the weight of the ] from 84 per ] to 96 (3.80 grams to 3.30 grams). He also reduced the silver purity from 99.5% to 93.5%—the silver weight dropping from 3.80 grams to 2.97 grams. He also reduced the weight of the ] from 40 per Roman pound to 45 (7.9 grams to 7.2 grams). ] hand-out, . {{better source needed|date=October 2023}}}} | |||

| According to Tacitus, upon hearing news of the fire, Nero returned to Rome to organize a relief effort, which he paid for from his own funds.<ref name="annals-xv-39"/> Nero's contributions to the relief extended to personally taking part in the search for and rescue of victims of the blaze, spending days searching the debris without even his bodyguards.{{Citation needed|date=May 2010}} After the fire, Nero opened his palaces to provide shelter for the homeless, and arranged for food supplies to be delivered in order to prevent starvation among the survivors.<ref name="annals-xv-39"/> In the wake of the fire, he made a new urban development plan. Houses after the fire were spaced out, built in brick, and faced by ] on wide roads.<ref name="annals-xv-43"/> Nero also built a new palace complex known as the ] in an area cleared by the fire. This included lush artificial landscapes and a 30 meter statue of himself, the ].<ref name = "Tacitus-Annals-15"/> The size of this complex is debated (from 100 to 300 acres).<ref>Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning, First, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, pp. 227–8. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.</ref><ref>Ball, Larry F. (2003). The Domus Aurea and the Roman architectural revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521822513.</ref><ref>Warden reduces its size to under {{convert|100|acre|km2}}. Warden, P.G., "The Domus Aurea Reconsidered," Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 40 (1981) pp. 271–278.</ref> To find the necessary funds for the reconstruction, ] were imposed on the provinces of the empire.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| ===Later years=== | |||

| According to Tacitus, the population searched for a scapegoat and rumors held Nero responsible.<ref name="annals-xv-44"/> To deflect blame, Nero targeted Christians. He ordered Christians to be thrown to dogs, while others were crucified and burned.<ref name="annals-xv-44"/> | |||

| In AD 65, ], a Roman statesman, organized a ] with the help of ] and ], a tribune and a centurion of the Praetorian Guard.<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref> According to Tacitus, many conspirators wished to "rescue the state" from the emperor and restore the ].<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref> The freedman Milichus discovered the conspiracy and reported it to Nero's secretary, ].<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref> As a result, the conspiracy failed and its members were executed, including ], the poet.<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero's previous advisor ] was accused by Natalis; he denied the charges but was still ordered to commit suicide, as by this point he had fallen out of favor with Nero.<ref>], ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| Nero was said to have kicked Poppaea to death in AD 65, before she could give birth to his second child. Modern historians, noting the probable biases of Suetonius, Tacitus, and Cassius Dio, and the likely absence of eyewitnesses to such an event, propose that Poppaea may have died after miscarriage or in childbirth.<ref>Rudich, Vasily (1993) ''Political Dissidence Under Nero''. Psychology Press. pp. 135–136. {{ISBN|9780415069519}}</ref> Nero went into deep mourning; Poppaea was given a sumptuous ] and ], and was promised a temple for her cult. A year's importation of incense was burned at the funeral. Her body was not cremated, as would have been strictly customary, but embalmed after the Egyptian manner and entombed;<!--Please don't link to ] or ]--> it is not known where.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Counts, Derek B.|title=Regum Externorum Consuetudine: The Nature and Function of Embalming in Rome|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25011039|journal=Classical Antiquity|volume= 15 |issue= 2|date=1996|pages= 189–190|quote= p. 193, note 18 "We should not consider it an insult that Poppaea was not buried in the Mausoleum of Augustus, as were other members of the imperial family until the time of Nerva." 196 (note 37, citing Pliny the elder, ''Natural History'', 12.83).|doi=10.2307/25011039|jstor=25011039}}</ref> | |||

| Tacitus described the event: | |||

| In AD 67, Nero married ], a young boy who is said to have greatly resembled Poppaea. Nero had him castrated and married him with all the usual ceremonies, including a dowry and a bridal veil. It is believed that he did this out of regret for his killing of Poppaea.{{sfn|Cassius Dio|loc=62.28}}<ref>{{Citation|last=Suetonius|editor1-first=Robert A|editor1-last=Kaster|title=Nero|work=Studies on the Text of Suetonius' 'De Vita Caesarum'|year=2016|publisher=Oxford University Press|doi=10.1093/oseo/instance.00233087|isbn=978-0-19-875847-1}}</ref> | |||

| {{cquote|Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judaea, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired.<ref name="annals-xv-44"/>}} | |||

| ===Revolt of Vindex and Galba and Nero's death=== | |||

| ===Public performances=== | |||

| In March 68, ], the governor of ], rebelled against Nero's tax policies.<ref name="Cassius-22">Cassius Dio, .</ref><ref>Donahue, John, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080911211039/http://www.roman-emperors.org/galba.htm |date=11 September 2008 }} at ''De Imperatoribus Romanis''.</ref> ], the governor of ], was ordered to put down Vindex's rebellion.<ref name="cassiusdio-lxiii-24">], .</ref> In an attempt to gain support from outside his own province, Vindex called upon ], the governor of ], to join the rebellion and to declare himself emperor in opposition to Nero.<ref name="Plutarch-galba-5">], .</ref> | |||

| ] on the reverse.]] | |||

| ].]] | |||

| At the ] in May 68, Verginius' forces easily defeated those of Vindex, and the latter committed suicide.<ref name="cassiusdio-lxiii-24"/> However, after defeating the rebel, Verginius' legions attempted to proclaim their own commander as Emperor. Verginius refused to act against Nero, but the discontent of the legions of Germania and the continued opposition of Galba in Hispania did not bode well for him.<ref>], .</ref> | |||

| Nero enjoyed driving a one-horse chariot, singing to the lyre, and poetry.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ], ].</ref> He even composed songs that were performed by other entertainers throughout the empire.<ref>Philostratus II, ''Life of Apollonius'' ; Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Vitellius .</ref> At first, Nero only performed for a private audience.<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.33">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| While Nero had retained some control of the situation, support for Galba increased despite his being officially declared a "public enemy".<ref name="Plutarch-galba-5"/> The prefect of the ], ], also abandoned his allegiance to the Emperor and came out in support of Galba.{{sfn|Plutarch|loc=}} | |||

| In 64, Nero began singing in public in ] in order to improve his popularity.<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.33"/> He also sang at the second ] in 65.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'' Life of Nero .</ref> It was said that Nero craved the attention,<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> but historians also write that Nero was encouraged to sing and perform in public by the Senate, his inner circle and the people.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Vitellius ; Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero , .</ref> Ancient historians strongly criticize his choice to perform, calling it shameful.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ]; Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> | |||

| In response, Nero fled Rome with the intention of going to the port of ] and, from there, to take a fleet to one of the still-loyal eastern provinces. According to Suetonius, Nero abandoned the idea when some army officers openly refused to obey his commands, responding with a line from ]'s '']'': "Is it so dreadful a thing then to die?" Nero then toyed with the idea of fleeing to ], throwing himself upon the mercy of Galba, or appealing to the people and begging them to pardon him for his past offences "and if he could not soften their hearts, to entreat them at least to allow him the ]". Suetonius reports that the text of this speech was later found in Nero's writing desk, but that he dared not give it from fear of being torn to pieces before he could reach the Forum.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=47}} | |||

| Nero was convinced to participate in the ] of 67 in order to improve relations with Greece and display Roman dominance.<ref>Philostratus II, ''Life of Apollonius'' .</ref> As a competitor, Nero raced a ten-horse chariot and nearly died after being thrown from it.<ref name="suetonius-nero-24">Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> He also performed as an actor and a singer.<ref>Suetonius, ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero .</ref> Though Nero faltered in his racing (in one case, dropping out entirely before the end) and acting competitions,<ref name="suetonius-nero-24"/> he won these crowns nevertheless and paraded them when he returned to Rome.<ref name="suetonius-nero-24"/> The victories are attributed to Nero bribing the judges and his status as emperor.<ref>Suetonius ''The Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero , .</ref> | |||

| Nero returned to Rome and spent the evening in the palace. After sleeping, he awoke at about midnight to find the palace guard had left. Dispatching messages to his friends' palace chambers for them to come, he received no answers. Upon going to their chambers personally, he found them all abandoned. When he called for a ] or anyone else adept with a sword to kill him, no one appeared. He cried, "Have I neither friend nor foe?" and ran out as if to throw himself into the ].{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=47}} | |||

| ===War and peace with Parthia=== | |||

| Returning, Nero sought a place where he could hide and collect his thoughts. An imperial freedman, ], offered his villa, {{convert|4|mi|abbr=on}} outside the city. Travelling in disguise, Nero and four loyal ], ], ], ], and ], reached the villa, where Nero ordered them to dig a grave for him.<ref>], ''] 5''</ref> At this time, Nero learned that the Senate had declared him a public enemy.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=48–49}} Nero prepared himself for ], pacing up and down muttering ''Qualis artifex pereo'' ("What an artist the world is losing!"). Losing his nerve, he begged one of his companions to set an example by killing himself first. At last, the sound of approaching horsemen drove Nero to face the end. However, he still could not bring himself to take his own life, but instead forced his private secretary, Epaphroditus, to perform the task.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=49}}].]] | |||

| {{details|Roman-Parthian War of 58–63}} | |||

| When one of the horsemen entered and saw that Nero was dying, he attempted to stop the bleeding, but efforts to save Nero's life were unsuccessful. Nero's final words were "Too late! This is fidelity!".{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=49}} He died on 9 June 68,{{efn-lr|] : "from the death of Nero to the beginning of Vespasian's rule a year and twenty-two days elapsed". Vespasian's reign officially began on 1 July (], ), which places the death on 9 June. Furthermore, ]' '']'' () gives a reign length of "thirteen years and seven months and twenty-seven days". ] () gives "13 years, 7 months and 28 days" (using ]).}} the anniversary of the death of his first wife, ], and was buried in the Mausoleum of the Domitii Ahenobarbi, in what is now the ] (]) area of Rome.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=50}} According to ], it is unclear whether Nero took his own life.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf211/npnf211.ii.vi.ii.xxix.html#fnf_ii.vi.ii.xxix-p2.1|title=Philip Schaff: NPNF-211. Sulpitius Severus, Vincent of Lerins, John Cassian – Christian Classics Ethereal Library|website=ccel.org|access-date=24 November 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Shortly after Nero's accession to the throne in 55, the Roman ] ] overthrew their prince ] and he was replaced with the ] prince ].<ref name="annals-xiii-7">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> This was seen as a Parthian invasion of Roman territory.<ref name="annals-xiii-7"/> There was concern in Rome over how the young emperor would handle the situation.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero reacted by immediately sending the military to the region under the command of ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> The Parthians temporarily relinquished control of Armenia to Rome.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| With his death, the ] ended.<ref name=agrippina>{{cite book|last = Barrett| first = A. A| title = Agrippina: sister of Caligula, wife of Claudius, mother of Nero| location = London| date = 1996|isbn=978-0713468540|publisher=Routledge}}</ref>{{rp|19}} Chaos would ensue in the ].<ref name="tacitus-histories-I.2">Tacitus, ''Histories'' ].</ref> | |||

| The peace did not last and full-scale war broke out in 58. The Parthian king ] refused to remove his brother Tiridates from Armenia.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> The Parthians began a full-scale invasion of the Armenian kingdom.<ref name="annals-xiii-46"/> Commander Corbulo responded and repelled most of the Parthian army that same year.<ref name="annals-xiii-55">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Tiridates retreated and Rome again controlled most of Armenia.<ref name="annals-xiii-55"/> | |||

| ===After Nero=== | |||

| Nero was acclaimed in public for this initial victory.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> ], a Cappadocian noble raised in Rome, was installed by Nero as the new ruler of Armenia.<ref name="annals-xiv-36">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Corbulo was appointed governor of Syria as a reward.<ref name="annals-xiv-36"/> | |||

| {{see also|Nero Redivivus legend|Pseudo-Nero}} | |||

| ] of Nero, c. after 68. Artwork portraying Nero rising to divine status after his death.]] | |||

| According to Suetonius and Cassius Dio, the people of Rome celebrated the death of Nero.{{sfn|Cassius Dio|loc=}}{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=57}} Tacitus, though, describes a more complicated political environment. Tacitus mentions that Nero's death was welcomed by senators, nobility, and the upper class.<ref name="histories-i-4">Tacitus, ''Histories'' ].</ref> The lower class, slaves, frequenters of the arena and the theater, and "those who were supported by the famous excesses of Nero", on the other hand, were upset with the news.<ref name="histories-i-4"/> Members of the military were said to have mixed feelings, as they had allegiance to Nero but had been bribed to overthrow him.<ref name="tacitus-histories-I.5">Tacitus, ''Histories'' ].</ref> | |||

| Eastern sources, namely ] and ], mention that Nero's death was mourned as he "restored the liberties of ] with a wisdom and moderation quite alien to his character", and that he "held our liberties in his hand and respected them".{{sfn|Philostratus|loc=}} Modern scholarship generally holds that, while the Senate and more well-off individuals welcomed Nero's death, the general populace was "loyal to the end and beyond, for Otho and Vitellius both thought it worthwhile to appeal to their ]".{{sfn|Griffin|2002|p=186}} | |||

| ] ''c.'' 60. Nero's peace deal with Parthia was a political victory at home and made him beloved in the east.]] | |||

| Nero's name was erased from some monuments, in what Edward Champlin regards as an "outburst of private zeal".<ref>], p. 29.</ref> Many portraits of Nero were reworked to represent other figures; according to Eric R. Varner, over 50 such images survive.<ref name="pollini">{{Cite journal |last=Pollini |first=John |date=2006 |title=Review of Mutilation and Transformation: Damnatio Memoriae and Roman Imperial Portraiture |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/25067270 |journal=The Art Bulletin |volume=88 |issue=3 |pages=590–597 |jstor=25067270 |issn=0004-3079}}</ref> This reworking of images is often explained as part of the way in which the memory of disgraced emperors was condemned posthumously,<ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.11141/ia.42.2|title = Sanctioning Memory: Changing Identity – Using 3D laser scanning to identify two 'new' portraits of the Emperor Nero in English antiquarian collections| journal=Internet Archaeology| issue=42|year = 2016|last1 = Russell|first1 = Miles| last2=Manley| first2=Harry| doi-access=free}}</ref> a practice known as '']''. Champlin doubts that the practice is necessarily negative and notes that some continued to create images of Nero long after his death.<ref>], pp. 29–31.</ref> Damaged portraits of Nero, often with hammer blows directed to the face, have been found in many provinces of the Roman Empire, three recently having been identified from the ].<ref name="pollini" /><ref>{{Cite journal | doi=10.11141/ia.32.5|title = Finding Nero: shining a new light on Romano-British sculpture| journal=Internet Archaeology| issue=32|year = 2013|last1 = Russell|first1 = Miles| last2=Manley| first2=Harry| doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| In 62, Tigranes invaded the Parthian province of ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Again, Rome and Parthia were at war and this continued until 63. Parthia began building up for a strike against the Roman province of Syria.<ref name="annals-xv-4">Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Corbulo tried to convince Nero to continue the war, but Nero opted for a peace deal instead.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> There was anxiety in Rome about eastern grain supplies and a budget deficit.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| The civil war during the ] was described by ancient historians as a troubling period.<ref name="tacitus-histories-I.2"/> According to Tacitus, this instability was rooted in the fact that emperors could no longer rely on the perceived legitimacy of the imperial bloodline, as Nero and those before him could.<ref name="histories-i-4"/> ] began his short reign with the execution of many of Nero's allies.<ref>], ''Histories'' ].</ref> One such notable enemy included ], who claimed to be the son of Emperor ].{{sfn|Plutarch|loc=}} | |||

| The result was a deal where Tiridates again became the Armenian king, but was crowned in Rome by emperor Nero.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> In the future, the ] was to be a Parthian prince, but his appointment required approval from the Romans. Tiridates was forced to come to Rome and partake in ceremonies meant to display Roman dominance.<ref name="tacitus-annals-xv.38"/><ref>Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> | |||

| ] overthrew Galba. Otho was said to be liked by many soldiers because he had been a friend of Nero and resembled him somewhat in temperament.<ref>], ''Histories'' ].</ref> It was said that the common Roman hailed Otho as Nero himself.<ref name="suetonius-otho-7">], .</ref> Otho used "Nero" as a surname and reerected many statues to Nero.<ref name="suetonius-otho-7"/> ] overthrew Otho. Vitellius began his reign with a large funeral for Nero complete with songs written by Nero.<ref>Suetonius, .</ref> | |||

| This peace deal of 63 was a considerable victory for Nero politically.<ref name="cassiusdio-lxii-23">Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' .</ref> Nero became very popular in the eastern provinces of Rome and with the Parthians as well.<ref name="cassiusdio-lxii-23"/> The peace between Parthia and Rome lasted 50 years until emperor ] of Rome invaded Armenia in 114. | |||

| After Nero's death in AD 68, there was a widespread belief, especially in the eastern provinces, that he was not dead and somehow would return.<ref>Suetonius, ; Tacitus, ''Histories'' ]; Cassius Dio, ''Roman History'' {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221122094705/https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/66%2A.html#19 |date=22 November 2022 }}</ref> This belief came to be known as the ]. The ] of Nero's return lasted for hundreds of years after Nero's death. ] wrote of the legend as a popular belief in AD 422.<ref name="augustine">Augustine of Hippo, ''City of God''. {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070302004357/http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/npnf102.iv.XX.19.html |date=2 March 2007 }}</ref> | |||

| ===Other major power struggles and rebellions=== | |||

| ], Moscow.]] | |||

| The war with Parthia was not Nero's only major war but he was both criticized and praised for an aversion to battle.<ref>Suetonius ''Lives of Twelve Caesars'', Life of Nero ; Marcus Annaeus Lucanus ''Pharsalia'' (Civil War) (''c.'' 65).</ref> Like many emperors, Nero faced a number of rebellions and power struggles within the empire. | |||

| At least ] emerged leading rebellions. The first, who sang and played the cithara or lyre, and whose face was similar to that of the dead emperor, appeared in 69 AD during the reign of Vitellius.<ref name="tacitus-histories-II.8">Tacitus, ''Histories'' ].</ref> After persuading some to recognize him, he was captured and executed.<ref name="tacitus-histories-II.8"/> Sometime during the reign of ] (79–81), another impostor appeared in Asia and sang to the accompaniment of the lyre and looked like Nero, but he, too, was killed.{{sfn|Cassius Dio|loc=}}<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/66%2A.html |title=Archived copy |access-date=14 December 2022 |archive-date=22 November 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221122094705/https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Cassius_Dio/66%2A.html |url-status=bot: unknown }}</ref> Twenty years after Nero's death, during the reign of ], there was a third pretender. He was supported by the Parthians, who only reluctantly gave him up,{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=57}} and the matter almost came to war.<ref name="tacitus-histories-I.2"/> | |||

| ;British Revolt of 60–61 (Boudica's Uprising) | |||

| {{See|Boudicca#Boudica.27s_uprising}} | |||

| In 60, a major rebellion broke out in the province of ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> While the governor ] and his troops were busy capturing the island of Mona (]) from the druids, the tribes of the south-east staged a revolt led by queen ] of the ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Boudica and her troops destroyed three cities before the army of Paullinus was able to return, be reinforced and put down the rebellion in 61.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Fearing Paullinus himself would provoke further rebellion, Nero replaced him with the more passive ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| ==Military conflicts== | |||

| ;The Pisonian Conspiracy of 65 | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| {{Main|Pisonian conspiracy}} | |||

| | align = right | |||

| In 65, ], a Roman statesman, organized a conspiracy against Nero with the help of Subrius Flavus and Sulpicius Asper, a tribune and a centurion of the Praetorian Guard.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> According to Tacitus, many conspirators wished to "rescue the state" from the emperor and restore the ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> The freedman Milichus discovered the conspiracy and reported it to Nero's secretary, ].<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> As a result, the conspiracy failed and its members were executed including ], the poet.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> Nero's previous advisor, ] was ordered to commit suicide after admitting he discussed the plot with the conspirators.<ref>Tacitus, ''Annals'' ].</ref> | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| | width = 190 | |||

| | image1 = Gold Aureus of Nero.png | |||

| | caption1 = ] of Nero, {{circa}} AD 64 | |||

| | image2 = INC-3007-a Ауреус. Нерон. Ок. 64—68 гг. (аверс).png | |||

| | caption2 = Aureus of Nero, {{circa}} AD 68 | |||

| | total_width = | |||

| }} | |||

| ===Boudica's uprising=== | |||

| {{Further|Boudican revolt}} | |||

| In Britannia (Britain) in AD 59, ], leader of the ] tribe and a ] of Rome during Claudius' reign, had died. The client state arrangement was unlikely to survive following the death of Claudius. The will of the Iceni tribal King Prasutagus, leaving control of the Iceni to his daughters, was denied. When the Roman ] ] scourged Prasutagus' wife ] and raped her daughters, the Iceni revolted. They were joined by the Celtic ] tribe and ] became the most significant provincial rebellion of the 1st century AD.{{sfn|Shotter|2012|p=32}}{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=254}} Under Queen Boudica, the towns of Camulodunum (Colchester), Londinium (London) and Verulamium (St. Albans) were burned, and a substantial body of ] infantry were eliminated. The governor of the province, ], assembled his remaining forces and ]. Although order was restored for some time, Nero considered abandoning the province.{{sfn|Suetonius|loc=18, 39–40}} ] replaced the former procurator, Catus Decianus, and Classicianus advised Nero to replace Paulinus who continued to punish the population even after the rebellion was over.{{sfn|Scullard|2011|p=265}} Nero decided to adopt a more lenient approach by appointing a new governor, ].{{sfn|Shotter|2012|p=33}} | |||

| ===Peace with Parthia=== | |||

| ;The First Jewish War of 66–70 | |||

| {{further|Roman–Parthian War of 58–63}} | |||

| In 66, there was a ] in Judea stemming from Greek and Jewish religious tension.<ref>Josephus, ''War of the Jews'' ].</ref> In 67, Nero dispatched ] to restore order.<ref>Josephus, ''War of the Jews'' ].</ref> This revolt was eventually put down in 70, after Nero's death.<ref>Josephus, ''War of the Jews'' ].</ref> This revolt is famous for Romans breaching the walls of Jerusalem and destroying the Second ].<ref>Josephus, ''War of the Jews'' ].</ref> | |||