| Revision as of 00:28, 8 February 2011 editVsmith (talk | contribs)Administrators272,326 editsm Reverted edits by 204.116.208.170 (talk) to last version by J. Johnson← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:55, 6 January 2025 edit undoPlantsurfer (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users40,022 edits Reverted 1 edit by 146.115.113.12 (talk): Rv, unexplained changeTags: Twinkle Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Movement of Earth's continents relative to each other}} | |||

| {{About|the development of the continental drift hypothesis before 1958|the contemporary theory|plate tectonics}} | |||

| {{About|the development of the continental drift theory before 1958|the contemporary theory|Plate tectonics|other uses|Continental Drift (disambiguation)}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Distinguish|Continental drip}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2024}} | |||

| '''Continental drift''' is the |

'''Continental drift''' is the ], originating in the early 20th century, that ]'s ]s move or drift relative to each other over ] time.<ref name="pubs.usgs.gov" /> The theory of continental drift has since been validated and incorporated into the science of ], which studies the movement of the continents as they ride on plates of the Earth's ].<ref name="Oreskes-2002" /> | ||

| The speculation that continents might have "drifted" was first put forward by ] in 1596. A pioneer of the modern view of mobilism was the Austrian geologist ].<ref>Kalliope Verbund: ''''</ref><ref>Helmut W. Flügel: ''''. In: Geo. Alp., Vol. 1, 2004.</ref> The concept was independently and more fully developed by ] in his 1915 publication, <nowiki/>"The Origin of Continents and Oceans".<ref name="Wegener-1912" /> However, at that time his hypothesis was rejected by many for lack of any motive mechanism{{explain|reason="Motive mechanism" is an academic term that the general reader may not understand.|date=January 2025}}. In 1931, the English geologist ] proposed ] for that mechanism. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| {{Main|Timeline of the development of tectonophysics}} | |||

| == |

== History == | ||

| {{Further|Timeline of the development of tectonophysics (before 1954)}} | |||

| ] {{Harv|Ortelius|1596}},<ref>{{Citation |last=Romm |first=James |title=A New Forerunner for Continental Drift |journal=Nature |date=February 3, 1994 |volume=367 |pages=407–408 |doi=10.1038/367407a0 |postscript=. }}</ref> Theodor Christoph Lilienthal (1756),<ref name=schmeling2004 >{{Cite web |first=Harro |last=Schmeling |url=http://www.geophysik.uni-frankfurt.de/~schmelin/skripte/Geodynn1-kap1-2-S1-S22-2004.pdf |title=Geodynamik |year=2004 |publisher=Univesity of Frankfurt |language=german }}</ref> ] (1801 and 1845),<ref name=schmeling2004 /> ] {{Harv|Snider-Pellegrini|1858}}, and others had noted earlier that the shapes of ]s on opposite sides of the ] (most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together.<ref>{{Citation |url=http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/crerar/crerar-prize/2003%2004%20Brusatte.pdf |title=Continents Adrift and Sea-Floors Spreading: The Revolution of Plate Tectonics |first=Stephen |last=Brusatte}}</ref> W. J. Kious described Ortelius' thoughts in this way:<ref>{{Citation |last=Kious |first=W.J. |coauthors=Tilling, R.I. |title=This Dynamic Earth: the Story of Plate Tectonics |origyear=1996 |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/dynamic.html |accessdate=2008-01-29 |edition=Online |publisher=U.S. Geological Survey |isbn=0160482208 |chapter=Historical perspective |chapterurl=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/historical.html |year=2001 |month=February}}</ref> | |||

| {{quote|Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus ... suggested that the Americas were "torn away from Europe and Africa ... by earthquakes and floods" and went on to say: "The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three ."}} | |||

| === Early history === | |||

| {{See also|Early modern Netherlandish cartography|l1=Early modern Netherlandish cartography and geography}} | |||

| ] by ], 1633]] | |||

| ] {{Harv|Ortelius|1596}},<ref name="Romm-1994" /> Theodor Christoph Lilienthal (1756),<ref name="Schmeling-2004" /> ] (1801 and 1845),<ref name="Schmeling-2004" /> ] {{Harv|Snider-Pellegrini|1858}}, and others had noted earlier that the shapes of ]s on opposite sides of the ] (most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together.<ref name="Brusatte-2016" /> W. J. Kious described Ortelius's thoughts in this way:<ref name="Kious-2001" /> | |||

| {{blockquote|Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus ... suggested that the Americas were "torn away from Europe and Africa ... by earthquakes and floods" and went on to say: "The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three ."}} | |||

| In 1889, ] remarked, "It was formerly a very general belief, even amongst geologists, that the great features of the earth's surface, no less than the smaller ones, were subject to continual mutations, and that during the course of known geological time the continents and great oceans had, again and again, changed places with each other."<ref name="Wallace-1889" /> He quotes ] as saying, "Continents, therefore, although permanent for whole geological epochs, shift their positions entirely in the course of ages."<ref name="Lyell-1872" /> and claims that the first to throw doubt on this was ] in 1849. | |||

| ]'s Illustration of the closed and opened ] (1858)<ref name="Snider-Pellegrini-1858" />]] | |||

| In his ''Manual of Geology'' (1863), Dana wrote, "The continents and oceans had their general outline or form defined in earliest time. This has been proved with regard to North America from the position and distribution of the first beds of the ], – those of the ]. The facts indicate that the continent of North America had its surface near tide-level, part above and part below it (p.196); and this will probably be proved to be the condition in Primordial time of the other continents also. And, if the outlines of the continents were marked out, it follows that the outlines of the oceans were no less so".<ref name="Dana-1863" /> Dana was enormously influential in America—his ''Manual of Mineralogy'' is still in print in revised form—and the theory became known as the ''Permanence theory''.<ref name="Oreskes-2002-2" /> | |||

| This appeared to be confirmed by the exploration of the deep sea beds conducted by the ], 1872–1876, which showed that contrary to expectation, land debris brought down by rivers to the ocean is deposited comparatively close to the shore on what is now known as the ]. This suggested that the oceans were a permanent feature of the Earth's surface, rather than them having "changed places" with the continents.<ref name="Wallace-1889" /> | |||

| ] had proposed a supercontinent ] in 1885<ref name="Suess-1885" /> and the ] in 1893,<ref name="Suess-1893" /> assuming a ] between the present continents submerged in the form of a ], and ] had written an 1895 paper proposing that the Earth's interior was fluid, and disagreeing with ] on the age of the Earth.<ref name="Perry-1895" /> | |||

| === Wegener and his predecessors === | === Wegener and his predecessors === | ||

| ] | |||

| The hypothesis that the continents had once formed ] before breaking apart and drifting to their present locations was fully formulated by ] in 1912.<ref name=weg>{{Citation | |||

| |last= Wegener|first= Alfred |coauthors= |date= 6 January 1912 |title= Die Herausbildung der Grossformen der Erdrinde (Kontinente und Ozeane), auf geophysikalischer Grundlage |journal= Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen |volume= 63 |issue= |pages= 185–195, 253–256, 305–309 |url= http://epic.awi.de/Publications/Polarforsch2005_1_3.pdf |accessdate= |doi = | |||

| |postscript= . }}</ref> | |||

| Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past authors with similar ideas:<ref name=wegb>{{Citation | author=Wegener, A. | title = The Origin of Continents and Oceans | year=1929/1966 |publisher=Courier Dover Publications|isbn=0486617084}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | author=Wegener, A. | title = ]|edition= 4 | year=1929 |publisher=Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges.| place=Braunschweig}}</ref> | |||

| Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890),<ref>{{Citation | author=Coxworthy, F.| title = | place=London | publisher=W. J. S. Phillips| year=1848/1924}}</ref> | |||

| ] (between 1889 and 1909), ] (1907)<ref>{{Citation | author=Pickering, W.H| title = | journal= Popular Astronomy | pages=274–287| year=1907}}</ref> | |||

| and ] (1908). | |||

| Apart from the earlier speculations mentioned above, the idea that the American continents had once formed a single landmass with Eurasia and Africa was postulated by several scientists before ]'s 1912 paper.<ref name="Wegener-1912" /> Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past authors with similar ideas:<ref name="Wegener-1966" /><ref name="Wegener-1929" /> Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890),<ref name="Coxworthy-1924" /> ] (between 1889 and 1909), ] (1907)<ref name="Pickering-1907" /> and ] (1908).<ref name="Taylor-1910" /> | |||

| For example: the similarity of southern continent geological formations had led ] to conjecture in 1889 and 1909 that all the continents had once been joined into a ] (now known as ]); Wegener noted the similarity of Mantovani's and his own maps of the former positions of the southern continents. Through ] activity due to ] this continent broke and the new continents drifted away from each other because of further expansion of the rip-zones, where the oceans now lie. This led Mantovani to propose an ] which has since been shown to be incorrect.<ref>{{Citation | author=Mantovani, R.| author-link =| title = Les fractures de l’écorce terrestre et la théorie de Laplace | journal= Bull. Soc. Sc. Et Arts Réunion | pages=41–53| year=1889}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | author=Mantovani, R.| title = L’Antarctide |journal= Je m’instruis. La science pour tous |volume=38 | pages=595–597| year=1909}}</ref><ref>{{Citation | author=Scalera, G. | contribution =Roberto Mantovani an Italian defender of the continental drift and planetary expansion | contribution-url=http://hdl.handle.net/2122/2017 | editor=Scalera, G. and Jacob, K.-H. |title =Why expanding Earth? – A book in honour of O.C. Hilgenberg | year=2003 | place=Rome | publisher= Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia |pages= 71–74}}</ref> | |||

| The similarity of southern continent geological formations had led ] to conjecture in 1889 and 1909 that all the continents had once been joined into a ]; Wegener noted the similarity of Mantovani's and his own maps of the former positions of the southern continents. In Mantovani's conjecture, this continent broke due to ] activity caused by ], and the new continents drifted away from each other because of further expansion of the rip-zones, where the oceans now lie. This led Mantovani to propose a now-discredited ].<ref name="Mantovani-1889" /><ref name="Mantovani-1909" /><ref name="Scalera-2003" /> | |||

| Some sort of continental drift without expansion was proposed by ], who suggested in 1908 (published in 1910) that the continents were dragged towards the equator by increased lunar gravity during the ], thus forming the Himalayas and Alps on the southern faces. Wegener said that of all those theories, Taylor's, although not fully developed, had the most similarities to his own.<ref>{{Citation | author=Taylor, F.B. | title = | journal= GSA Bulletin | volume=21 |issue=2| pages=179–226| year=1910 | doi=10.1130/1052-5173(2005)0152.0.CO;2}}</ref> | |||

| Continental drift without expansion was proposed by ],<ref name="Lane-1944" /> who suggested in 1908 (published in 1910) that the continents were moved into their present positions by a process of "continental creep",<ref name="Taylor-1910a" /><ref name="Frankel-2012" /> later proposing a mechanism of increased tidal forces during the ] dragging the crust towards the equator. He was the first to realize that one of the effects of continental motion would be the formation of mountains, attributing the formation of the Himalayas to the collision between the ] with Asia.<ref name="Powell-2015" /> Wegener said that of all those theories, Taylor's had the most similarities to his own. For a time in the mid-20th century, the theory of continental drift was referred to as the "Taylor-Wegener hypothesis".<ref name="Lane-1944" /><ref name="Powell-2015" /><ref name="Hansen" /><ref name="Wood-2016" /> | |||

| Wegener was the first to use the phrase "continental drift" (1912, 1915)<ref name=weg /><ref name=wegb /> (in German "die Verschiebung der Kontinente" – translated into English in 1922) and formally publish the hypothesis that the continents had somehow "drifted" apart. Although he presented much evidence for continental drift, he was unable to provide a convincing explanation for the physical processes which might have caused this drift. His suggestion that the continents had been pulled apart by the ] (''Polflucht'') of the Earth's rotation or by a small component of astronomical ] was rejected as calculations showed that the force was not sufficient.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/geology/techist.html |title=Plate Tectonics: The Rocky History of an Idea |quote=Wegener's inability to provide an adequate explanation of the forces responsible for continental drift and the prevailing belief that the earth was solid and immovable resulted in the scientific dismissal of his theories.}}</ref> The ] hypothesis was also studied by ] in 1920 and found to be implausible. | |||

| Alfred Wegener first presented his hypothesis to the German Geological Society on 6 January 1912.<ref name="Wegener-1912" /> He proposed that the continents had once formed a single landmass, called ], before breaking apart and drifting to their present locations.<ref name="Wegenerproofs">{{cite web |url = http://www.bbm.me.uk/portsdown/PH_061_History_b.htm |title = Wegener and his proofs |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060505053619/http://www.bbm.me.uk/portsdown/PH_061_History_b.htm |archive-date=5 May 2006 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ==Evidence that continents 'drift'== | |||

| Wegener was the first to use the phrase "continental drift" (1912, 1915)<ref name="Wegener-1912" /><ref name="Wegener-1966" /> ({{langx|de|"die Verschiebung der Kontinente"}}) and to publish the hypothesis that the continents had somehow "drifted" apart. Although he presented much evidence for continental drift, he was unable to provide a convincing explanation for the physical processes which might have caused this drift. He suggested that the continents had been pulled apart by the ] ({{lang|de|Polflucht}}) of the Earth's rotation or by a small component of astronomical ], but calculations showed that the force was not sufficient.<ref name="PlateTectonics-2011" /> The {{lang|de|]}} hypothesis was also studied by ] in 1920 and found to be implausible. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Details|Plate tectonics}}<!-- | |||

| ''Note: This section contains evidence available to Wegener's contemporaries and predecessors'' --> | |||

| === Rejection of Wegener's theory, 1910s–1950s === | |||

| Evidence for continental drift is now extensive. Similar plant and animal ]s are found around different continent shores, suggesting that they were once joined. The fossils of ], a freshwater reptile rather like a small crocodile, found both in ] and ], are one example; another is the discovery of fossils of the land ] '']'' from ]s of the same age from locations in ], ], and ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/continents.html |publisher=USGS |title=Rejoined continents }}</ref> There is also living evidence — the same animals being found on two continents. Some ] families (e.g.: Ocnerodrilidae, Acanthodrilidae, Octochaetidae) are found in South America and Africa, for instance. | |||

| Although now accepted, and even with a minority of scientific proponents over the decades, the theory of continental drift was largely rejected for many years, with evidence in its favor considered insufficient. One problem was that a plausible driving force was missing.<ref name="pubs.usgs.gov" /> A second problem was that Wegener's estimate of the speed of continental motion, {{cvt|250|cm/y|round=10}}, was implausibly high.<ref name="UniCalifMusPaleontology" /> (The currently accepted rate for the separation of the Americas from Europe and Africa is about {{cvt|2.5|cm/y|0}}.)<ref name="Unavco-2015" /> Furthermore, Wegener was treated less seriously because he was not a geologist. Even today, the details of the forces propelling the plates are poorly understood.<ref name="pubs.usgs.gov" /> | |||

| The English geologist ] championed the theory of continental drift at a time when it was deeply unfashionable. He proposed in 1931 that the Earth's mantle contained convection cells which dissipated heat produced by radioactive decay and moved the crust at the surface.<ref name="Holmes-1931" /> His ''Principles of Physical Geology'', ending with a chapter on continental drift, was published in 1944.<ref name="Holmes-1944" /> | |||

| The complementary arrangement of the facing sides of South America and Africa is obvious, but is a temporary coincidence. In millions of years, ] and ], and other forces of ] will further separate and rotate those two continents. It was this temporary feature which inspired Wegener to study what he defined as continental drift, although he did not live to see his hypothesis become generally accepted. | |||

| Geological maps of the time showed huge ]s spanning the Atlantic and Indian oceans to account for the similarities of fauna and flora and the divisions of the Asian continent in the Permian period, but failing to account for glaciation in India, Australia and South Africa.<ref name="Wells-1931" /> | |||

| Widespread distribution of ] glacial sediments in South America, Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, India, Antarctica and Australia was one of the major pieces of evidence for the theory of continental drift. The continuity of glaciers, inferred from oriented ]s and deposits called ]s, suggested the existence of the supercontinent of ], which became a central element of the concept of continental drift. Striations indicated glacial flow away from the equator and toward the poles, in modern coordinates, and supported the idea that the southern continents had previously been in dramatically different locations, as well as contiguous with each other.<ref name=wegb /> | |||

| ====The fixists==== | |||

| ==Rejection of Wegener's theory, and subsequent vindication== | |||

| ] and ] opposed the idea of continental drift and worked on a "fixist"<ref name="Sen30" /> ] model with ] playing a key role in the formation of ]s.<ref name="Sen28" /><ref name="Sen29" /> Other geologists who opposed continental drift were ], ], Rollin Chamberlin, Walther Bucher and ].<ref name="Sen31" /><ref name="Bremer-1983">{{Cite journal|title=Albrecht Penck (1858–1945) and Walther Penck (1888–1923), two German geomorphologists|journal=]|last=Bremer|first=Hanna|volume=27|pages=129–138|issue=2|year=1983|doi=10.1127/zfg/27/1983/129|bibcode=1983ZGm....27..129B}}</ref> In 1939 an international geological conference was held in ].<ref name="Frankel403" /> This conference came to be dominated by the fixists, especially as those geologists specializing in tectonics were all fixists except Willem van der Gracht.<ref name="Frankel403" /> Criticism of continental drift and mobilism was abundant at the conference not only from tectonicists but also from sedimentological (Nölke), paleontological (Nölke), mechanical (Lehmann) and oceanographic (], ]) perspectives.<ref name="Frankel403" /><ref name="Frankel405" /> ], the organizer of the conference, was also a fixist<ref name="Frankel403" /> who together with Troll held the view that excepting the ] continents were not radically different from oceans in their behaviour.<ref name="Frankel405" /> The mobilist theory of ] for the ] was criticized by Kurt Leuchs.<ref name="Frankel403" /> The few drifters and mobilists at the conference appealed to ] (Kirsch, Wittmann), ] (]), ] (Gerth) and ] measurements (Wegener, K).<ref name="Frankel407" /> F. Bernauer correctly equated ] in south-west ] with the ], arguing with this that the floor of the Atlantic Ocean was undergoing ] just like Reykjanes. Bernauer thought this extension had drifted the continents only {{cvt|100-200|km|round=10}} apart, the approximate width of the ].<ref name="Frankel409" /> | |||

| While it is now accepted that the continents do move across the Earth's surface – though more in a driven mode than the aimlessness suggested by "drift" – as a ''theory'', continental drift was not accepted for many years. One problem was that a plausible driving force was missing. And it did not help that Wegener was not a geologist. | |||

| ], who attended university in the second half of the 1940s, recounted an incident illustrating its lack of acceptance then: "I once asked one of my lecturers why he was not talking to us about continental drift and I was told, sneeringly, that if I could prove there was a force that could move continents, then he might think about it. The idea was moonshine, I was informed."<ref name="McKie-2012" /> | |||

| The British geologist ] championed the theory of continental drift at a time when it was deeply unfashionable. He proposed that the Earth's mantle contained convection cells that dissipated radioactive heat and moved the crust at the surface. His ''Principles of Physical Geology'', ending with a chapter on continental drift, was published in 1944.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Holmes |first=Arthur |title=Principles of Physical Geology |edition=1 |place=Edinburgh |publisher=Thomas Nelson & Sons |year=1944 |isbn=0174480202 }}</ref> | |||

| As late as |

As late as 1953—just five years before ]<ref name="Carey-1958" /> introduced the theory of ]—the theory of continental drift was rejected by the physicist Scheidegger on the following grounds.<ref name="Scheidegger-1953" /> | ||

| * First, it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating ] would ], and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier ] episodes. | |||

| |last1=Carey |first1=S. W. |year=1958 |contribution=The tectonic approach to continental drift |editor1-last=Carey |editor1-first=S. W. |title=Continental Drift—A symposium |publisher=Univ. of Tasmania |place=Hobart |pages=177–363}}</ref> introduced the theory of ] – the theory of continental drift was rejected by the physicist Scheiddiger on the following grounds.<ref>{{citation|last= Scheidegger|first= |title= Examination of the physics of theories of orogenesis|journal= GSA Bulletin|year= 1953|volume= 64|pages= 127–150|doi= 10.1130/0016-7606(1953)642.0.CO;2|first1= Adrian E.}}</ref> | |||

| * Second, masses floating freely in a fluid substratum, like icebergs in the ocean, should be in ] equilibrium (in which the forces of gravity and buoyancy are in balance). But gravitational measurements showed that many areas are not in isostatic equilibrium. | |||

| * Third, there was the problem of why some parts of the Earth's surface (crust) should have solidified while other parts were still fluid. Various attempts to explain this foundered on other difficulties. | |||

| === Road to acceptance === | |||

| * First, it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating geoid would collect at the equator, and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier orogenic episodes. | |||

| {{Main|Plate tectonics}} | |||

| * Second, masses floating freely in a fluid substratum, like icebergs in the ocean, should be in ] equilibrium (where the forces of gravity and buoyancy are in balance). Gravitational measurements were showing that many areas are not in isostatic equilibrium. | |||

| * Third, there was the problem of why some parts of the Earth's surface (crust) should have solidifed while other parts were still fluid. Various attempts to explain this foundered on other difficulties. | |||

| From the 1930s to the late 1950s, works by ], Holmes, ], and numerous others outlined concepts that were close or nearly identical to modern plate tectonics theory. In particular, the English geologist Arthur Holmes proposed in 1920 that plate junctions might lie beneath the ], and in 1928 that convection currents within the mantle might be the driving force.<ref name="Holmes-1928" /> Holmes's views were particularly influential: in his bestselling textbook, ''Principles of Physical Geology,'' he included a chapter on continental drift, proposing that Earth's ] contained ]s which dissipated ] heat and moved the crust at the surface.<ref name="Wessel-2007" /><ref name="Vine-1966" /> Holmes's proposal resolved the phase disequilibrium objection (the underlying fluid was kept from solidifying by radioactive heating from the core). However, scientific communication in the 1930s and 1940s was inhibited by ], and the theory still required work to avoid foundering on the ] and ] objections. Worse, the most viable forms of the theory predicted the existence of convection cell boundaries reaching deep into the Earth, that had yet to be observed.{{citation needed|date=May 2018}} | |||

| Geophysicist ] is credited with providing seismologic evidence supporting plate tectonics which encompassed and superseded continental drift with “Seismology and the New Global Tectonics,” published in 1968, using data collected from seismologic stations, including those he set up in the South Pacific.<ref></ref> | |||

| In 1947, a team of scientists led by ] confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the sediments was chemically and physically different from continental crust.<ref name="Lippsett-2001" /><ref name="Lippsett-2006" /> As oceanographers continued to ] the ocean basins, a system of mid-oceanic ridges was detected. An important conclusion was that along this system, new ocean floor was being created, which led to the concept of the "]".<ref name="Heezen-1960" /> | |||

| It is now known that there are two kinds of crust, ] and ]. Continental crust is inherently lighter and of a different composition to oceanic crust, but both kinds reside above a much deeper fluid mantle. Oceanic crust is created at ], and this, along with ], drives the system of plates in a chaotic manner, resulting in continuous ] and areas of isostatic imbalance. The theory of ] explains all this, including the movement of the continents, better than Wegener's theory. | |||

| Meanwhile, scientists began recognizing odd magnetic variations across the ocean floor using devices developed during World War II to detect submarines.<ref name="LATimes-2009" /> Over the next decade, it became increasingly clear that the magnetization patterns were not anomalies, as had been originally supposed. In a series of papers published between 1959 and 1963, Heezen, Dietz, Hess, Mason, Vine, Matthews, and ] collectively realized that the magnetization of the ocean floor formed extensive, zebra-like patterns: one stripe would exhibit normal polarity and the adjoining stripes reversed polarity.<ref name="Mason-1961" /><ref name="Korgen-1995" /><ref name="Spiess-2003" /> The best explanation was the "conveyor belt" or ]. New ] from deep within the Earth rises easily through these weak zones and eventually erupts along the crest of the ridges to create new oceanic crust. The new crust is magnetized by the Earth's magnetic field, which undergoes ]. Formation of new crust then displaces the magnetized crust apart, akin to a conveyor belt – hence the name.<ref name="Heirtzler-1966" /> | |||

| ==Bibliography== | |||

| '''Notes''': | |||

| {{Reflist|2}} | |||

| Without workable alternatives to explain the stripes, geophysicists were forced to conclude that Holmes had been right: ocean rifts were sites of perpetual orogeny at the boundaries of convection cells.<ref name="LePichon-1968" /><ref name="McKenzie-1967" /> By 1967, barely two decades after discovery of the mid-oceanic rifts, and a decade after discovery of the striping, plate tectonics had become axiomatic to modern geophysics. | |||

| '''References''': | |||

| * {{Citation |last=Le Grand |first=H. E. |authorlink= |title=Drifting Continents and Shifting Theories |edition= |year= 1988 |publisher=Cambridge University |isbn= 0-521-31105-5 }} | |||

| * {{Citation |last=Ortelius |first=Abraham |title=Thesaurus Geographicus |place=Antwerp |publisher=Plantin |year=1596 |edition=3 |ref=CITEREFOrtelius1596 }} | |||

| * {{Citation |title=La Création et ses mystères dévoilés |publisher=Frank and Dentu |place=Paris |first=Antonio |last=Snider-Pellegrini |year=1858 |ref=CITEREFSnider-Pellegrini1858 }} | |||

| In addition, ], in collaboration with ], who was initially sceptical of Tharp's observations that her maps confirmed continental drift theory, provided essential corroboration, using her skills in cartography and seismographic data, to confirm the theory.<ref name="Barton-2002" /><ref name="Blakemore-2016" /><ref name="Evans-2002" /><ref name="Doel-2006" /><ref name="Wills-2016" /> | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| ====Modern evidence==== | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Continental Drift}} | |||

| Geophysicist ] is credited with providing seismologic evidence supporting plate tectonics which encompassed and superseded continental drift with the article "Seismology and the New Global Tectonics", published in 1968, using data collected from seismologic stations, including those he set up in the South Pacific.<ref name="NYTimes-2011" /><ref name="Isacks-1968" /> The modern theory of ], refining Wegener, explains that there are two kinds of crust of different composition: ] and ], both floating above a much deeper "]" mantle. Continental crust is inherently lighter. Oceanic crust is created at ], and this, along with ], drives the system of plates in a chaotic manner, resulting in continuous ] and areas of isostatic imbalance. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Link GA|eo}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ]) ]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Evidence for the movement of continents on tectonic plates is now extensive. Similar plant and animal ]s are found around the shores of different continents, suggesting that they were once joined. The fossils of '']'', a freshwater reptile rather like a small crocodile, found both in ] and ], are one example; another is the discovery of fossils of the land ] '']'' in ] of the same age at locations in ], ], and ].<ref name="USGS" /> There is also living evidence, with the same animals being found on two continents. Some ] families (such as Ocnerodrilidae, Acanthodrilidae, Octochaetidae) are found in South America and Africa. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The complementary arrangement of the facing sides of South America and Africa is an obvious and temporary coincidence. In millions of years, ], ], and other forces of ] will further separate and rotate those two continents. It was that temporary feature that inspired Wegener to study what he defined as continental drift although he did not live to see his hypothesis generally accepted. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The widespread distribution of ] glacial sediments in South America, Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, India, Antarctica and Australia was one of the major pieces of evidence for the theory of continental drift. The continuity of glaciers, inferred from oriented ]s and deposits called ]s, suggested the existence of the supercontinent of ], which became a central element of the concept of continental drift. Striations indicated glacial flow away from the equator and toward the poles, based on continents' current positions and orientations, and supported the idea that the southern continents had previously been in dramatically different locations that were contiguous with one another.<ref name="Wegener-1966" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| ====GPS evidence==== | |||

| ] | |||

| In measuring continental drift with GPS relative to some other locations whose positions were measured by GPS, a GPS device located in Maui, Hawaii moved about 48 cm latitudinally and about 84 cm longitudinally during a time of 14 years.<ref>A HOMEPAGE SECTION dated September 2, 2014 by DJUBLONSKOPF titled: "How Do We Know The Continents Are Moving?" at the address: https://www.djublonskopf.com/2014/09/02/how-do-we-know-the-continents-are-moving/</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| == See also == | |||

| ] | |||

| * {{annotated link|Geological history of Earth}} | |||

| ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| == Citations == | |||

| ] | |||

| {{reflist|refs= | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="pubs.usgs.gov">{{cite web|url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/historical.html|title=Historical perspective |publisher=United States Geological Survey|access-date=29 January 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180727100546/https://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/historical.html|archive-date=27 July 2018|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Schmeling-2004">{{Cite web |first=Harro |last=Schmeling |url=http://www.geophysik.uni-frankfurt.de/~schmelin/skripte/Geodynn1-kap1-2-S1-S22-2004.pdf |title=Geodynamik |year=2004 |publisher=University of Frankfurt |language=de}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Wallace-1889">{{citation|first=Alfred Russel|last=Wallace|title=Darwinism …|year=1889|chapter=12|publisher=Macmillan|page=341|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0S4aAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA341}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Wegener-1912">{{Citation|last=Wegener|first=Alfred|title=Die Herausbildung der Grossformen der Erdrinde (Kontinente und Ozeane), auf geophysikalischer Grundlage|date=6 January 1912|url=http://epic.awi.de/Publications/Polarforsch2005_1_3.pdf|postscript=.|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111004001150/http://epic.awi.de/Publications/Polarforsch2005_1_3.pdf|url-status=dead|journal=Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen|volume=63|pages=185–195, 253–256, 305–309|archive-date=4 October 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Wegener-1966">{{Citation | author=Wegener, A. | title = The Origin of Continents and Oceans |orig-year=1929|year=1966 |publisher=Courier Dover Publications|isbn=978-0-486-61708-4}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Lane-1944">{{citation|jstor=20023483|title=Frank Bursley Taylor (1860–1938)|journal=Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences|volume=75|issue=6|pages=176–178|last1=Lane|first1=A. C.|year=1944}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Powell-2015">{{cite book |last=Powell |first=James Lawrence |date=2015 |title=Four Revolutions in the Earth Sciences: From Heresy to Truth |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fX6SBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA70 |publisher=Columbia University Press |pages=69–70 |access-date=20 October 2015 |isbn=978-0-231-53845-9 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160603181049/https://books.google.com/books?id=fX6SBQAAQBAJ&pg=PA70 |archive-date=3 June 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Sen30">], p. 30</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Sen28">], p. 28</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Sen29">], p. 29</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Sen31">], p. 31</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Frankel403">], p. 403</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Frankel405">], p. 405</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Frankel407">], p. 407</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Frankel409">], p. 409</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Snider-Pellegrini-1858">Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, ''La Création et ses mystères dévoilés'' (Creation and its mysteries revealed) (Paris, France: Frank et Dentu, 1858), {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170205021404/https://books.google.com/books?id=UZdKmF3iEdUC&pg=PA314-IA3 |date=5 February 2017}} (between pages 314 and 315).</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Oreskes-2002">{{Harvnb|Oreskes|2002|p=324}}.</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Romm-1994">{{Citation |last=Romm |first=James |title=A New Forerunner for Continental Drift |journal=Nature |date=3 February 1994 |volume=367 |pages=407–408 |doi=10.1038/367407a0 |postscript=. |issue=6462|bibcode = 1994Natur.367..407R |s2cid=4281585}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Brusatte-2016">{{Citation |url=https://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/crerar/crerar-prize/2003%2004%20Brusatte.pdf |title=Continents Adrift and Sea-Floors Spreading: The Revolution of Plate Tectonics |first=Stephen |last=Brusatte |access-date=16 May 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303182900/http://www.lib.uchicago.edu/e/crerar/crerar-prize/2003%2004%20Brusatte.pdf |archive-date=3 March 2016 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Kious-2001">{{Citation |last1=Kious |first1=W. J. |last2=Tilling |first2=R. I. |title=This Dynamic Earth: the Story of Plate Tectonics |orig-year=1996 |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/dynamic.html |access-date=29 January 2008 |edition=Online |publisher=United States Geological Survey |isbn=978-0-16-048220-5 |chapter=Historical perspective |chapter-url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/historical.html |date=February 2001 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110408212926/http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/dynamic.html |archive-date=8 April 2011 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Lyell-1872">{{citation|first=Charles|last=Lyell|title=Principles of Geology ...|year=1872|edition=11|publisher=John Murray|page=258|url=https://archive.org/stream/principlesgeolo41lyelgoog#page/n287/mode/1up/|access-date=16 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160406143142/https://archive.org/stream/principlesgeolo41lyelgoog#page/n287/mode/1up/|archive-date=6 April 2016|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Dana-1863">{{citation|first=James D.|last=Dana|title=Manual of Geology|year=1863|publisher=Theodore Bliss & Co, Philadelphia|page=732|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=cKJVHih77X0C&pg=PA732|access-date=16 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150515103528/https://books.google.com/books?id=cKJVHih77X0C&pg=PA732|archive-date=15 May 2015|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Oreskes-2002-2">{{harvnb|Oreskes|2002}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| <ref name="Suess-1885">Eduard Suess, ''Das Antlitz der Erde'' (The Face of the Earth), vol. 1 (Leipzig, (Germany): G. Freytag, 1885), From p. 768: ''"Wir nennen es Gondwána-Land, nach der gemeinsamen alten Gondwána-Flora, ... "'' (We name it Gondwána-Land, after the common ancient flora of Gondwána ... )</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Suess-1893">Edward Suess (March 1893) {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170205023611/https://books.google.com/books?id=yQUVAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA180|date=5 February 2017}}, ''Natural Science: A Monthly Review of Scientific Progress'' (London), '''2''' : 180- 187. From page 183: "This ocean we designate by the name "Tethys", after the sister and consort of Oceanus. The latest successor of the Tethyan Sea is the present Mediterranean."</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Perry-1895">Perry, John (1895) "On the age of the earth", ''Nature'', '''51''' : {{Webarchive|url=https://archive.today/20150217234720/http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015038750868;view=1up;seq=266|date=17 February 2015}}, 341–342, 582–585.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Wegener-1929">{{Citation | author=Wegener, A. | title = Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane|edition= 4 | year=1929 |publisher=Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges.| place=Braunschweig| title-link = :s:de:Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Coxworthy-1924">{{cite book|last1=Coxworthy|first1=Franklin|title=Electrical Condition; Or, How and where Our Earth was Created|date=1924|publisher=J.S. Phillips|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=STj7PAAACAAJ|access-date=6 December 2014}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Pickering-1907">{{Citation | author=Pickering, W.H| title = The Place of Origin of the Moon – The Volcani Problems | journal= Popular Astronomy | volume = 15 | pages=274–287| year=1907 | bibcode=1907PA.....15..274P}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Taylor-1910">Frank Bursley Taylor (3 June 1910) , ''Bulletin of the Geological Society of America'', '''21''' : 179–226.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Mantovani-1889">{{Citation | author=Mantovani, R.| title = Les fractures de l'écorce terrestre et la théorie de Laplace | journal= Bull. Soc. Sc. Et Arts Réunion | pages=41–53| year=1889}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Mantovani-1909">{{Citation | author=Mantovani, R.| title = L'Antarctide |journal= Je M'instruis. La Science Pour Tous |volume=38 | pages=595–597| year=1909}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Scalera-2003">{{Citation | author=Scalera, G. | chapter=Roberto Mantovani an Italian defender of the continental drift and planetary expansion |editor1=Scalera, G. |editor2=Jacob, K.-H. |title =Why expanding Earth? – A book in honour of O.C. Hilgenberg | year=2003 | place=Rome | publisher= National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology |pages= 71–74| hdl =2122/2017}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Taylor-1910a">{{Citation | author=Taylor, F.B. | title = Bearing of the tertiary mountain belt on the origin of the earth's plan | journal= GSA Bulletin | volume=21 |issue=2| pages=179–226| year=1910 | doi= 10.1130/GSAB-21-179| archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180601200620/ftp://rock.geosociety.org/pub/GSAToday/gt0507.pdf| url=ftp://rock.geosociety.org/pub/GSAToday/gt0507.pdf|url-status=dead | bibcode = 1910GSAB...21..179T| archive-date = 1 June 2018 }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Frankel-2012">Henry R. Frankel, "Wegener and Taylor develop their theories of continental drift", in ''The Continental Drift Controversy'' Volume 1: ''Wegener and the Early Debate'', pp. 38–80, Cambridge University Press, 2012. {{ISBN|9780521875042}} {{doi|10.1017/CBO9780511842368.004}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Hansen">Hansen, L. T., ''Some considerations of, and additions to the Taylor-Wegener hypothesis of continental displacement'', Los Angeles, 1946. {{OCLC|1247437 OCLC}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Wood-2016">R. M. Wood, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160514222416/https://books.google.com/books?id=3TO4uTA30NAC&pg=PA254 |date=14 May 2016}}, ''New Scientist'', 24 January 1980</ref> | |||

| <ref name="PlateTectonics-2011">{{cite web |url=http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/geology/techist.html |title=Plate Tectonics: The Rocky History of an Idea |quote=Wegener's inability to provide an adequate explanation of the forces responsible for continental drift and the prevailing belief that the earth was solid and immovable resulted in the scientific dismissal of his theories. |access-date=23 August 2006 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110411031414/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/geology/techist.html |archive-date=11 April 2011 |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="UniCalifMusPaleontology">University of California Museum of Paleontology, {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171208011353/http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/wegener.html |date=8 December 2017}} (accessed 30 April 2015).</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Unavco-2015">Unavco {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150425002611/http://www.unavco.org/software/geodetic-utilities/plate-motion-calculator/plate-motion-calculator.html |date=25 April 2015}} (accessed 30 April 2015).</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Holmes-1931">{{cite journal|title=Radioactivity and Earth Movements|first=Arthur|last=Holmes|author-link=Arthur Holmes|journal=Transactions of the Geological Society of Glasgow|volume=18|issue=3|year=1931|pages=559–606|url=http://www.mantleplumes.org/WebDocuments/Holmes1931.pdf|doi=10.1144/transglas.18.3.559|s2cid=122872384|access-date=15 January 2014|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191009101823/http://www.mantleplumes.org/WebDocuments/Holmes1931.pdf|archive-date=9 October 2019|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Holmes-1944">{{Cite book |last=Holmes |first=Arthur |author-link= Arthur Holmes|title=Principles of Physical Geology |edition=1st |place=Edinburgh |publisher=Thomas Nelson & Sons |year=1944 |isbn=978-0-17-448020-4}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Wells-1931">See map based on the work of the American paleontologist ] in {{citation|title=The Science of life|first1=H. G.|last1=Wells|first2=Julian|last2=Huxley|first3=G. P.|last3=Wells|year=1931|page=445|url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.221951/page/n465/mode/2up}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="McKie-2012">{{cite news |title=David Attenborough: force of nature |first=Robin |last=McKie |url=https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/oct/26/richard-attenborough-climate-global-arctic-environment |newspaper=] |location=London |date=28 October 2012 |access-date=29 October 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131031164253/http://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2012/oct/26/richard-attenborough-climate-global-arctic-environment |archive-date=31 October 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Carey-1958">{{Cite news |last1=Carey |first1=S. W. |year=1958|editor1-last=Carey |editor1-first=S. W. |title=Continental Drift—A symposium |publisher=Univ. of Tasmania |place=Hobart |pages=177–363}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Scheidegger-1953">{{citation|last= Scheidegger |first=Adrian E. |title=Examination of the physics of theories of orogenesis |journal=GSA Bulletin |year=1953|volume= 64|issue=2 |pages= 127–150 |doi=10.1130/0016-7606(1953)642.0.CO;2|bibcode = 1953GSAB...64..127S}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Holmes-1928">{{cite journal |last=Holmes |first=Arthur |year=1928 |title=Radioactivity and Earth movements |journal=Transactions of the Geological Society of Glasgow |volume=18 |issue=3 |pages=559–606|doi=10.1144/transglas.18.3.559 |s2cid=122872384}}; see also {{cite book |last=Holmes |first=Arthur |author-link= Arthur Holmes|year=1978 |title=Principles of Physical Geology |edition=3 |publisher=Wiley |pages=640–41 |isbn=978-0-471-07251-5}} and {{cite journal |title=Arthur Holmes and continental drift |last=Frankel |first=Henry |journal=The British Journal for the History of Science |volume=11 |issue=2 |date=July 1978 |pages=130–50 |jstor=4025726 |doi=10.1017/S0007087400016551|s2cid=145405854 }}.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Wessel-2007">{{citation |last1=Wessel |first1=P. |last2=Müller |first2=R. D. |year=2007 |chapter=Plate Tectonics |title=Treatise on Geophysics |publisher=Elsevier |volume=6 |pages=49–98}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Vine-1966">{{Cite journal | last1 = Vine | first1 = F. J. | title = Spreading of the Ocean Floor: New Evidence | doi = 10.1126/science.154.3755.1405 | journal = Science | volume = 154 | issue = 3755 | pages = 1405–1415 | year = 1966 | pmid = 17821553|bibcode = 1966Sci...154.1405V | s2cid = 44362406}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Lippsett-2001">{{cite journal |last=Lippsett |first=Laurence |url=http://www.columbia.edu/cu/alumni/Magazine/Winter2001/ewing.html |title=Maurice Ewing and the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory |journal=Living Legacies |year=2001 |access-date=4 March 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180112030533/http://www.columbia.edu/cu/alumni/Magazine/Winter2001/ewing.html |archive-date=12 January 2018 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Lippsett-2006">{{cite book |last=Lippsett |first=Laurence |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=l1os3mwQkxYC&pg=PR9|chapter=Maurice Ewing and the Lamont–Doherty Earth Observatory |editor=William Theodore De Bary |editor2=Jerry Kisslinger |editor3=Tom Mathewson |title=Living Legacies at Columbia |year=2006 |access-date=22 June 2010|isbn=978-0-231-13884-0|pages=277–97 |publisher=Columbia University Press}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Heezen-1960">{{cite journal |last=Heezen |first=B. |year=1960 |title=The rift in the ocean floor |journal=] |volume=203 |pages=98–110 |doi=10.1038/scientificamerican1060-98 |issue=4|bibcode=1960SciAm.203d..98H}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="LATimes-2009">{{citation|url=http://www.latimes.com/news/science/la-me-vacquier24-2009jan24,0,3328591.story|journal=Los Angeles Times|title=Victor Vacquier Sr., 1907–2009: Geophysicist was a master of magnetics|date=24 January 2009|page=B24|access-date=20 May 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140108214147/http://www.latimes.com/news/science/la-me-vacquier24-2009jan24,0,3328591.story|archive-date=8 January 2014|url-status=live}}.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Mason-1961">{{cite journal |last1=Mason |first1=Ronald G. |last2=Raff |first2=Arthur D. |year=1961 |title=Magnetic survey off the west coast of the United States between 32°N latitude and 42°N latitude |journal=Bulletin of the Geological Society of America |volume=72 |pages=1259–66|doi=10.1130/0016-7606(1961)722.0.CO;2 |issn=0016-7606|issue=8|bibcode= 1961GSAB...72.1259M}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Korgen-1995">{{cite journal |last=Korgen |first=Ben J. |year=1995 |title=A voice from the past: John Lyman and the plate tectonics story |journal=Oceanography |volume=8 |issue=1 |pages=19–20 |doi=10.5670/oceanog.1995.29 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Spiess-2003">{{cite journal |last1=Spiess |first1=Fred |last2=Kuperman |first2=William |year=2003 |title=The Marine Physical Laboratory at Scripps |journal=Oceanography |volume=16 |issue=3 |pages=45–54 |doi=10.5670/oceanog.2003.30 |doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Heirtzler-1966">See summary in {{cite journal |last1=Heirtzler |first1=James R. |first2=Xavier |last2=Le Pichon |first3=J. Gregory |last3=Baron |year=1966 |title=Magnetic anomalies over the Reykjanes Ridge |journal=Deep-Sea Research |volume=13 |issue=3 |pages=427–32 |doi=10.1016/0011-7471(66)91078-3 |bibcode= 1966DSRA...13..427H}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="LePichon-1968">{{cite journal |last=Le Pichon |first=Xavier |date=15 June 1968 |title=Sea-floor spreading and continental drift |journal=Journal of Geophysical Research |volume=73 |issue= 12 |pages=3661–97 |doi=10.1029/JB073i012p03661 |bibcode=1968JGR....73.3661L}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="McKenzie-1967">{{cite journal |last1=Mc Kenzie |first1=D. |last2=Parker |first2=R.L. |year=1967 |title=The North Pacific: an example of tectonics on a sphere |journal=Nature |volume=216 |pages=1276–1280 |doi=10.1038/2161276a0 |issue=5122 |bibcode= 1967Natur.216.1276M|s2cid=4193218}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Barton-2002">{{cite journal | last1 = Barton | first1 = Cathy | year = 2002 | title = Marie Tharp, oceanographic cartographer, and her contributions to the revolution in the Earth sciences | bibcode = 2002GSLSP.192..215B | journal = Geological Society, London, Special Publications | volume = 192 | issue = 1| pages = 215–228 | doi = 10.1144/gsl.sp.2002.192.01.11 | s2cid = 131340403}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Blakemore-2016">Blakemore, Erin (30 August 2016). "Seeing Is Believing: How Marie Tharp Changed Geology Forever". Smithsonian.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Evans-2002">Evans, R. (November 2002). "Plumbing Depths to Reach New Heights". Retrieved 2 June 2008.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Doel-2006">{{cite journal | last1 = Doel | first1 = R.E. | last2 = Levin | first2 = T.J. | last3 = Marker | first3 = M.K. | year = 2006 | title = Extending modern cartography to the ocean depths: military patronage, Cold War priorities, and the Heezen-Tharp mapping project, 1952–1959 | journal = Journal of Historical Geography | volume = 32 | issue = 3| pages = 605–626 | doi = 10.1016/j.jhg.2005.10.011}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Wills-2016">Wills, Matthew (8 October 2016). "The Mother of Ocean Floor Cartography". JSTOR. Retrieved 14 October 2016. While working with the North Atlantic data, she noted what must have been a rift between high undersea mountains. This suggested earthquake activity, which then only associated with fringe theory of continental drift. Heezen infamously dismissed his assistant's idea as "girl talk." But she was right, and her thinking helped to vindicate Alfred Wegener's 1912 theory of moving continents. Yet Tharp's name isn't on any of the key papers that Heezen and others published about plate tectonics between 1959 and 1963, which brought this once-controversial idea to the mainstream of earth sciences.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="NYTimes-2011">{{cite news|date=12 January 2011|title=Jack Oliver, Who Proved Continental Drift, Dies at 87|page=A16|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/12/science/earth/12oliver.html|url-status=live|access-date=6 June 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130526135459/http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/12/science/earth/12oliver.html|archive-date=26 May 2013}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="Isacks-1968">{{cite journal|last1=Isacks|first1=Bryan|last2=Oliver|first2=Jack|last3=Sykes|first3=Lynn R.|date=15 September 1968|title=Seismology and the New Global Tectonics|journal=]|volume=73|issue=18|pages=5855–5899|bibcode=1968JGR....73.5855I|doi=10.1029/JB073i018p05855}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="USGS">{{Cite web |url=http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/continents.html |publisher=United States Geological Survey |title=Rejoined continents |access-date=22 July 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100825180951/http://pubs.usgs.gov/gip/dynamic/continents.html |archive-date=25 August 2010 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| == General and cited sources == | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Frankel |first=Henry R.|date=2012 |title=The Continental Drift Controversy |volume=I: ''Wegener and the Early Debate'' |publisher=Cambridge |ref=Frankel }} | |||

| * {{Cite book |first=Homer Eugene |last=Le Grand |year=1988 |title=Drifting Continents and Shifting Theories |publisher=Cambridge University |isbn=978-0-521-31105-2 |ref=none |url-access=registration |url=https://archive.org/details/driftingcontinen00legr }} | |||

| * {{Cite book |first=Naomi |last=Oreskes |author-link=Naomi Oreskes |year=1999 |title=The Rejection of Continental Drift |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn= 978-0-19-511732-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=EEQdk9GRfkoC&pg=PA14 |ref=none}} (pb: {{ISBNT | 0-19-511733-6 }}) | |||

| * {{Cite encyclopedia |first1=Naomi |last1=Oreskes |title=Continental Drift |url=http://historyweb.ucsd.edu/oreskes/Papers/Continentaldrift2002.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120204234030/http://historyweb.ucsd.edu/oreskes/Papers/Continentaldrift2002.pdf |editor1-first=Ted |editor1-last=Munn |editor2-first=Michael C. |editor2-last=MacCracken |editor3-first=John S. |editor3-last=Perry |date=2002 |encyclopedia=Encyclopedia of Global Environmental Change |volume=1 |pages=321–325 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |place=Chichester, West Sussex |isbn=978-0-471-97796-4 |oclc=633880622 |archive-date=4 February 2012 }} <!-- CAUTION: catalogs are inconsistent. This is from the printed book. --> | |||

| * {{Cite book |first=Abraham |last=Ortelius |year=1596 |orig-year=1570 |title=Thesaurus Geographicus |place=Antwerp |publisher=Plantin |language=la |edition=3 |oclc=214324616}} (First edition published 1570, ) | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Şengör |first=Celâl|author-link=Celâl Şengör |date=1982|chapter=Classical theories of orogenesis|editor-last=Miyashiro|editor-first=Akiho|editor-link=Akiho Miyashiro|editor-last2=Aki|editor-first2=Keiiti|editor-last3=Şengör|editor-first3=Celâl |title=Orogeny |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-0-471-103769|ref=Sengor1982}} | |||

| * {{Cite book |first=Antonio |last=Snider-Pellegrini |year=1858 |title=La Création et ses mystères dévoilés |publisher=Frank and Dentu |place=Paris |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=UZdKmF3iEdUC&pg=PA314-IA3}}. | |||

| == External links == | |||

| {{Library resources box}} | |||

| {{Wikibooks|Historical Geology|Continental drift}} | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Continental Drift theory}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:55, 6 January 2025

Movement of Earth's continents relative to each other This article is about the development of the continental drift theory before 1958. For the contemporary theory, see Plate tectonics. For other uses, see Continental Drift (disambiguation). Not to be confused with Continental drip.

Continental drift is the scientific theory, originating in the early 20th century, that Earth's continents move or drift relative to each other over geologic time. The theory of continental drift has since been validated and incorporated into the science of plate tectonics, which studies the movement of the continents as they ride on plates of the Earth's lithosphere.

The speculation that continents might have "drifted" was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596. A pioneer of the modern view of mobilism was the Austrian geologist Otto Ampferer. The concept was independently and more fully developed by Alfred Wegener in his 1915 publication, "The Origin of Continents and Oceans". However, at that time his hypothesis was rejected by many for lack of any motive mechanism. In 1931, the English geologist Arthur Holmes proposed mantle convection for that mechanism.

History

Further information: Timeline of the development of tectonophysics (before 1954)Early history

See also: Early modern Netherlandish cartography and geography

Abraham Ortelius (Ortelius 1596), Theodor Christoph Lilienthal (1756), Alexander von Humboldt (1801 and 1845), Antonio Snider-Pellegrini (Snider-Pellegrini 1858), and others had noted earlier that the shapes of continents on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean (most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together. W. J. Kious described Ortelius's thoughts in this way:

Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus ... suggested that the Americas were "torn away from Europe and Africa ... by earthquakes and floods" and went on to say: "The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three ."

In 1889, Alfred Russel Wallace remarked, "It was formerly a very general belief, even amongst geologists, that the great features of the earth's surface, no less than the smaller ones, were subject to continual mutations, and that during the course of known geological time the continents and great oceans had, again and again, changed places with each other." He quotes Charles Lyell as saying, "Continents, therefore, although permanent for whole geological epochs, shift their positions entirely in the course of ages." and claims that the first to throw doubt on this was James Dwight Dana in 1849.

In his Manual of Geology (1863), Dana wrote, "The continents and oceans had their general outline or form defined in earliest time. This has been proved with regard to North America from the position and distribution of the first beds of the Lower Silurian, – those of the Potsdam epoch. The facts indicate that the continent of North America had its surface near tide-level, part above and part below it (p.196); and this will probably be proved to be the condition in Primordial time of the other continents also. And, if the outlines of the continents were marked out, it follows that the outlines of the oceans were no less so". Dana was enormously influential in America—his Manual of Mineralogy is still in print in revised form—and the theory became known as the Permanence theory.

This appeared to be confirmed by the exploration of the deep sea beds conducted by the Challenger expedition, 1872–1876, which showed that contrary to expectation, land debris brought down by rivers to the ocean is deposited comparatively close to the shore on what is now known as the continental shelf. This suggested that the oceans were a permanent feature of the Earth's surface, rather than them having "changed places" with the continents.

Eduard Suess had proposed a supercontinent Gondwana in 1885 and the Tethys Ocean in 1893, assuming a land-bridge between the present continents submerged in the form of a geosyncline, and John Perry had written an 1895 paper proposing that the Earth's interior was fluid, and disagreeing with Lord Kelvin on the age of the Earth.

Wegener and his predecessors

Apart from the earlier speculations mentioned above, the idea that the American continents had once formed a single landmass with Eurasia and Africa was postulated by several scientists before Alfred Wegener's 1912 paper. Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past authors with similar ideas: Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890), Roberto Mantovani (between 1889 and 1909), William Henry Pickering (1907) and Frank Bursley Taylor (1908).

The similarity of southern continent geological formations had led Roberto Mantovani to conjecture in 1889 and 1909 that all the continents had once been joined into a supercontinent; Wegener noted the similarity of Mantovani's and his own maps of the former positions of the southern continents. In Mantovani's conjecture, this continent broke due to volcanic activity caused by thermal expansion, and the new continents drifted away from each other because of further expansion of the rip-zones, where the oceans now lie. This led Mantovani to propose a now-discredited Expanding Earth theory.

Continental drift without expansion was proposed by Frank Bursley Taylor, who suggested in 1908 (published in 1910) that the continents were moved into their present positions by a process of "continental creep", later proposing a mechanism of increased tidal forces during the Cretaceous dragging the crust towards the equator. He was the first to realize that one of the effects of continental motion would be the formation of mountains, attributing the formation of the Himalayas to the collision between the Indian subcontinent with Asia. Wegener said that of all those theories, Taylor's had the most similarities to his own. For a time in the mid-20th century, the theory of continental drift was referred to as the "Taylor-Wegener hypothesis".

Alfred Wegener first presented his hypothesis to the German Geological Society on 6 January 1912. He proposed that the continents had once formed a single landmass, called Pangaea, before breaking apart and drifting to their present locations.

Wegener was the first to use the phrase "continental drift" (1912, 1915) (German: "die Verschiebung der Kontinente") and to publish the hypothesis that the continents had somehow "drifted" apart. Although he presented much evidence for continental drift, he was unable to provide a convincing explanation for the physical processes which might have caused this drift. He suggested that the continents had been pulled apart by the centrifugal pseudoforce (Polflucht) of the Earth's rotation or by a small component of astronomical precession, but calculations showed that the force was not sufficient. The Polflucht hypothesis was also studied by Paul Sophus Epstein in 1920 and found to be implausible.

Rejection of Wegener's theory, 1910s–1950s

Although now accepted, and even with a minority of scientific proponents over the decades, the theory of continental drift was largely rejected for many years, with evidence in its favor considered insufficient. One problem was that a plausible driving force was missing. A second problem was that Wegener's estimate of the speed of continental motion, 250 cm/year (100 in/year), was implausibly high. (The currently accepted rate for the separation of the Americas from Europe and Africa is about 2.5 cm/year (1 in/year).) Furthermore, Wegener was treated less seriously because he was not a geologist. Even today, the details of the forces propelling the plates are poorly understood.

The English geologist Arthur Holmes championed the theory of continental drift at a time when it was deeply unfashionable. He proposed in 1931 that the Earth's mantle contained convection cells which dissipated heat produced by radioactive decay and moved the crust at the surface. His Principles of Physical Geology, ending with a chapter on continental drift, was published in 1944.

Geological maps of the time showed huge land bridges spanning the Atlantic and Indian oceans to account for the similarities of fauna and flora and the divisions of the Asian continent in the Permian period, but failing to account for glaciation in India, Australia and South Africa.

The fixists

Hans Stille and Leopold Kober opposed the idea of continental drift and worked on a "fixist" geosyncline model with Earth contraction playing a key role in the formation of orogens. Other geologists who opposed continental drift were Bailey Willis, Charles Schuchert, Rollin Chamberlin, Walther Bucher and Walther Penck. In 1939 an international geological conference was held in Frankfurt. This conference came to be dominated by the fixists, especially as those geologists specializing in tectonics were all fixists except Willem van der Gracht. Criticism of continental drift and mobilism was abundant at the conference not only from tectonicists but also from sedimentological (Nölke), paleontological (Nölke), mechanical (Lehmann) and oceanographic (Troll, Wüst) perspectives. Hans Cloos, the organizer of the conference, was also a fixist who together with Troll held the view that excepting the Pacific Ocean continents were not radically different from oceans in their behaviour. The mobilist theory of Émile Argand for the Alpine orogeny was criticized by Kurt Leuchs. The few drifters and mobilists at the conference appealed to biogeography (Kirsch, Wittmann), paleoclimatology (Wegener, K), paleontology (Gerth) and geodetic measurements (Wegener, K). F. Bernauer correctly equated Reykjanes in south-west Iceland with the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, arguing with this that the floor of the Atlantic Ocean was undergoing extension just like Reykjanes. Bernauer thought this extension had drifted the continents only 100–200 km (60–120 mi) apart, the approximate width of the volcanic zone in Iceland.

David Attenborough, who attended university in the second half of the 1940s, recounted an incident illustrating its lack of acceptance then: "I once asked one of my lecturers why he was not talking to us about continental drift and I was told, sneeringly, that if I could prove there was a force that could move continents, then he might think about it. The idea was moonshine, I was informed."

As late as 1953—just five years before Carey introduced the theory of plate tectonics—the theory of continental drift was rejected by the physicist Scheidegger on the following grounds.

- First, it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating geoid would collect at the equator, and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier orogenic episodes.

- Second, masses floating freely in a fluid substratum, like icebergs in the ocean, should be in isostatic equilibrium (in which the forces of gravity and buoyancy are in balance). But gravitational measurements showed that many areas are not in isostatic equilibrium.

- Third, there was the problem of why some parts of the Earth's surface (crust) should have solidified while other parts were still fluid. Various attempts to explain this foundered on other difficulties.

Road to acceptance

Main article: Plate tectonicsFrom the 1930s to the late 1950s, works by Vening-Meinesz, Holmes, Umbgrove, and numerous others outlined concepts that were close or nearly identical to modern plate tectonics theory. In particular, the English geologist Arthur Holmes proposed in 1920 that plate junctions might lie beneath the sea, and in 1928 that convection currents within the mantle might be the driving force. Holmes's views were particularly influential: in his bestselling textbook, Principles of Physical Geology, he included a chapter on continental drift, proposing that Earth's mantle contained convection cells which dissipated radioactive heat and moved the crust at the surface. Holmes's proposal resolved the phase disequilibrium objection (the underlying fluid was kept from solidifying by radioactive heating from the core). However, scientific communication in the 1930s and 1940s was inhibited by World War II, and the theory still required work to avoid foundering on the orogeny and isostasy objections. Worse, the most viable forms of the theory predicted the existence of convection cell boundaries reaching deep into the Earth, that had yet to be observed.

In 1947, a team of scientists led by Maurice Ewing confirmed the existence of a rise in the central Atlantic Ocean, and found that the floor of the seabed beneath the sediments was chemically and physically different from continental crust. As oceanographers continued to bathymeter the ocean basins, a system of mid-oceanic ridges was detected. An important conclusion was that along this system, new ocean floor was being created, which led to the concept of the "Great Global Rift".

Meanwhile, scientists began recognizing odd magnetic variations across the ocean floor using devices developed during World War II to detect submarines. Over the next decade, it became increasingly clear that the magnetization patterns were not anomalies, as had been originally supposed. In a series of papers published between 1959 and 1963, Heezen, Dietz, Hess, Mason, Vine, Matthews, and Morley collectively realized that the magnetization of the ocean floor formed extensive, zebra-like patterns: one stripe would exhibit normal polarity and the adjoining stripes reversed polarity. The best explanation was the "conveyor belt" or Vine–Matthews–Morley hypothesis. New magma from deep within the Earth rises easily through these weak zones and eventually erupts along the crest of the ridges to create new oceanic crust. The new crust is magnetized by the Earth's magnetic field, which undergoes occasional reversals. Formation of new crust then displaces the magnetized crust apart, akin to a conveyor belt – hence the name.

Without workable alternatives to explain the stripes, geophysicists were forced to conclude that Holmes had been right: ocean rifts were sites of perpetual orogeny at the boundaries of convection cells. By 1967, barely two decades after discovery of the mid-oceanic rifts, and a decade after discovery of the striping, plate tectonics had become axiomatic to modern geophysics.

In addition, Marie Tharp, in collaboration with Bruce Heezen, who was initially sceptical of Tharp's observations that her maps confirmed continental drift theory, provided essential corroboration, using her skills in cartography and seismographic data, to confirm the theory.

Modern evidence

Geophysicist Jack Oliver is credited with providing seismologic evidence supporting plate tectonics which encompassed and superseded continental drift with the article "Seismology and the New Global Tectonics", published in 1968, using data collected from seismologic stations, including those he set up in the South Pacific. The modern theory of plate tectonics, refining Wegener, explains that there are two kinds of crust of different composition: continental crust and oceanic crust, both floating above a much deeper "plastic" mantle. Continental crust is inherently lighter. Oceanic crust is created at spreading centers, and this, along with subduction, drives the system of plates in a chaotic manner, resulting in continuous orogeny and areas of isostatic imbalance.

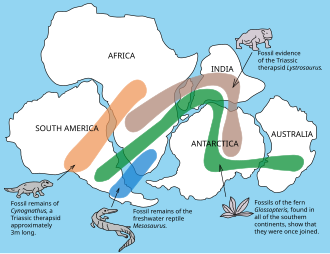

Evidence for the movement of continents on tectonic plates is now extensive. Similar plant and animal fossils are found around the shores of different continents, suggesting that they were once joined. The fossils of Mesosaurus, a freshwater reptile rather like a small crocodile, found both in Brazil and South Africa, are one example; another is the discovery of fossils of the land reptile Lystrosaurus in rocks of the same age at locations in Africa, India, and Antarctica. There is also living evidence, with the same animals being found on two continents. Some earthworm families (such as Ocnerodrilidae, Acanthodrilidae, Octochaetidae) are found in South America and Africa.

The complementary arrangement of the facing sides of South America and Africa is an obvious and temporary coincidence. In millions of years, slab pull, ridge-push, and other forces of tectonophysics will further separate and rotate those two continents. It was that temporary feature that inspired Wegener to study what he defined as continental drift although he did not live to see his hypothesis generally accepted.

The widespread distribution of Permo-Carboniferous glacial sediments in South America, Africa, Madagascar, Arabia, India, Antarctica and Australia was one of the major pieces of evidence for the theory of continental drift. The continuity of glaciers, inferred from oriented glacial striations and deposits called tillites, suggested the existence of the supercontinent of Gondwana, which became a central element of the concept of continental drift. Striations indicated glacial flow away from the equator and toward the poles, based on continents' current positions and orientations, and supported the idea that the southern continents had previously been in dramatically different locations that were contiguous with one another.

GPS evidence

In measuring continental drift with GPS relative to some other locations whose positions were measured by GPS, a GPS device located in Maui, Hawaii moved about 48 cm latitudinally and about 84 cm longitudinally during a time of 14 years.

See also

- Geological history of Earth – The sequence of major geological events in Earth's past

- Israel C. White

Citations

- ^ "Historical perspective [This Dynamic Earth, USGS]". United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 27 July 2018. Retrieved 29 January 2008.

- Oreskes 2002, p. 324.

- Kalliope Verbund: Ampferer, Otto (1875–1947)

- Helmut W. Flügel: Die virtuelle Welt des Otto Ampferer und die Realität seiner Zeit. In: Geo. Alp., Vol. 1, 2004.

- ^ Wegener, Alfred (6 January 1912), "Die Herausbildung der Grossformen der Erdrinde (Kontinente und Ozeane), auf geophysikalischer Grundlage" (PDF), Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen, 63: 185–195, 253–256, 305–309, archived from the original (PDF) on 4 October 2011.

- Romm, James (3 February 1994), "A New Forerunner for Continental Drift", Nature, 367 (6462): 407–408, Bibcode:1994Natur.367..407R, doi:10.1038/367407a0, S2CID 4281585.

- ^ Schmeling, Harro (2004). "Geodynamik" (PDF) (in German). University of Frankfurt.

- Brusatte, Stephen, Continents Adrift and Sea-Floors Spreading: The Revolution of Plate Tectonics (PDF), archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 16 May 2016

- Kious, W. J.; Tilling, R. I. (February 2001) , "Historical perspective", This Dynamic Earth: the Story of Plate Tectonics (Online ed.), United States Geological Survey, ISBN 978-0-16-048220-5, archived from the original on 8 April 2011, retrieved 29 January 2008

- ^ Wallace, Alfred Russel (1889), "12", Darwinism …, Macmillan, p. 341

- Lyell, Charles (1872), Principles of Geology ... (11 ed.), John Murray, p. 258, archived from the original on 6 April 2016, retrieved 16 February 2015

- Antonio Snider-Pellegrini, La Création et ses mystères dévoilés (Creation and its mysteries revealed) (Paris, France: Frank et Dentu, 1858), plates 9 and 10 Archived 5 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine (between pages 314 and 315).

- Dana, James D. (1863), Manual of Geology, Theodore Bliss & Co, Philadelphia, p. 732, archived from the original on 15 May 2015, retrieved 16 February 2015

- Oreskes 2002

- Eduard Suess, Das Antlitz der Erde (The Face of the Earth), vol. 1 (Leipzig, (Germany): G. Freytag, 1885), page 768. From p. 768: "Wir nennen es Gondwána-Land, nach der gemeinsamen alten Gondwána-Flora, ... " (We name it Gondwána-Land, after the common ancient flora of Gondwána ... )

- Edward Suess (March 1893) "Are ocean depths permanent?" Archived 5 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Natural Science: A Monthly Review of Scientific Progress (London), 2 : 180- 187. From page 183: "This ocean we designate by the name "Tethys", after the sister and consort of Oceanus. The latest successor of the Tethyan Sea is the present Mediterranean."

- Perry, John (1895) "On the age of the earth", Nature, 51 : 224–227 Archived 17 February 2015 at archive.today, 341–342, 582–585.

- ^ Wegener, A. (1966) , The Origin of Continents and Oceans, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-61708-4

- Wegener, A. (1929), Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (4 ed.), Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges.

- Coxworthy, Franklin (1924). Electrical Condition; Or, How and where Our Earth was Created. J.S. Phillips. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- Pickering, W.H (1907), "The Place of Origin of the Moon – The Volcani Problems", Popular Astronomy, 15: 274–287, Bibcode:1907PA.....15..274P

- Frank Bursley Taylor (3 June 1910) "Bearing of the Tertiary mountain belt on the origin of the earth's plan", Bulletin of the Geological Society of America, 21 : 179–226.

- Mantovani, R. (1889), "Les fractures de l'écorce terrestre et la théorie de Laplace", Bull. Soc. Sc. Et Arts Réunion: 41–53

- Mantovani, R. (1909), "L'Antarctide", Je M'instruis. La Science Pour Tous, 38: 595–597

- Scalera, G. (2003), "Roberto Mantovani an Italian defender of the continental drift and planetary expansion", in Scalera, G.; Jacob, K.-H. (eds.), Why expanding Earth? – A book in honour of O.C. Hilgenberg, Rome: National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology, pp. 71–74, hdl:2122/2017

- ^ Lane, A. C. (1944), "Frank Bursley Taylor (1860–1938)", Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 75 (6): 176–178, JSTOR 20023483