| Revision as of 00:36, 1 June 2004 editStevenj (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users14,833 edits don't use for formatting kludges← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:57, 8 January 2025 edit undoJack Beda (talk | contribs)96 edits →Standard basis, (+−−−) signature: Maybe this isn't useful, a full discussion is here: https://en.wikipedia.org/Sign_convention#Metric_signatureTag: Visual edit | ||

| (464 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|4-dimensional vector in relativity}} | |||

| In ], a '''four-vector''' is a ] in a four-dimensional real ], whose components transform like the space and time coordinates (''ct'', ''x'', ''y'', ''z'') under spatial rotations and ''boosts'' (a change by a constant velocity to another ]). The set of all such rotations and boosts, called ] and described by 4×4 matrices, forms the Lorentz group. | |||

| {{distinguish|p-vector}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date = March 2019}} | |||

| {{spacetime|cTopic=Mathematics}} | |||

| In ], a '''four-vector''' (or '''4-vector''', sometimes '''Lorentz vector''')<ref>Rindler, W. ''Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd edn.)'' (1991) Clarendon Press Oxford {{ISBN|0-19-853952-5}}</ref> is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under ]s. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional ] considered as a ] of the ] of the ], the ({{sfrac|1|2}},{{sfrac|1|2}}) representation. It differs from a ] in how its magnitude is determined. The transformations that preserve this magnitude are the Lorentz transformations, which include ] and ] (a change by a constant velocity to another ]).<ref name="BaskalKim2015">{{cite book|author1=Sibel Baskal|author2=Young S Kim|author3=Marilyn E Noz|title=Physics of the Lorentz Group|date=1 November 2015|publisher=Morgan & Claypool Publishers|isbn=978-1-68174-062-1}}</ref>{{rp|ch1}} | |||

| Four-vectors describe, for instance, position {{math|''x''{{i sup|''μ''}}}} in spacetime modeled as ], a particle's ] {{math|''p''{{i sup|''μ''}}}}, the amplitude of the ] {{math|''A''{{i sup|''μ''}}(''x'')}} at a point {{mvar|x}} in spacetime, and the elements of the subspace spanned by the ] inside the ]. | |||

| The basic vector of the ''']''' is the "event" ], defined as: | |||

| :<math> \mathbf{r} = \left( c \cdot t, x, y, z \right) </math> | |||

| where ''c'' is the ]. | |||

| It is called an "event" vector because of ]'s interpretation which state that the only ] measurable physics entities are intersection of two events in space and time (i.e. Two bodies meet at point ''(x,y,z)'' in time ''t''). | |||

| The Lorentz group may be represented by 4×4 matrices {{math|Λ}}. The action of a Lorentz transformation on a general ] four-vector {{mvar|X}} (like the examples above), regarded as a column vector with ] with respect to an ] in the entries, is given by | |||

| Examples of four-vectors include the coordinates (''ct'', ''x'', ''y'', ''z'') themselves, the four-current (''c''ρ, '''J''') formed from charge density ρ and current density '''J''', the electromagnetic four-potential (φ, '''A''') formed from the scalar potential φ and vector potential '''A''', and the four-momentum (''E''/''c'', '''p''') formed from the (relativistic) energy ''E'' and momentum '''p'''. The ] (''c'') is often used to ensure that the first coordinate (''time-like'', labeled by index 0) has the same units as the following three coordinates (''space-like'', labeled by indices 1,..,3). | |||

| <math display="block">X' = \Lambda X,</math> | |||

| The ] between four-vectors ''a'' and ''b'' is defined as follows: | |||

| (matrix multiplication) where the components of the primed object refer to the new frame. Related to the examples above that are given as contravariant vectors, there are also the corresponding ]s {{math|''x''<sub>''μ''</sub>}}, {{math|''p''<sub>''μ''</sub>}} and {{math|''A''<sub>''μ''</sub>(''x'')}}. These transform according to the rule | |||

| :<math> | |||

| a \cdot b | |||

| <math display="block">X' = \left(\Lambda^{-1}\right)^\textrm{T} X,</math> | |||

| = | |||

| \left( \begin{matrix}a_0 & a_1 & a_2 & a_3 \end{matrix} \right) | |||

| where {{math|<sup>T</sup>}} denotes the ]. This rule is different from the above rule. It corresponds to the ] of the standard representation. However, for the Lorentz group the dual of any representation is ] to the original representation. Thus the objects with covariant indices are four-vectors as well. | |||

| For an example of a well-behaved four-component object in special relativity that is ''not'' a four-vector, see ]. It is similarly defined, the difference being that the transformation rule under Lorentz transformations is given by a representation other than the standard representation. In this case, the rule reads {{math|''X''{{′}} {{=}} Π(Λ)''X''}}, where {{math|Π(Λ)}} is a 4×4 matrix other than {{math|Λ}}. Similar remarks apply to objects with fewer or more components that are well-behaved under Lorentz transformations. These include ]s, ]s, ]s and spinor-tensors. | |||

| The article considers four-vectors in the context of special relativity. Although the concept of four-vectors also extends to ], some of the results stated in this article require modification in general relativity.<!-- TO DO: provide a GR section for this article! --> | |||

| == Notation == | |||

| The notations in this article are: lowercase bold for ] vectors, hats for three-dimensional ]s, capital bold for ] vectors (except for the four-gradient), and ]. | |||

| == Four-vector algebra == | |||

| ===Four-vectors in a real-valued basis=== | |||

| A '''four-vector''' ''A'' is a vector with a "timelike" component and three "spacelike" components, and can be written in various equivalent notations:<ref>Relativity DeMystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (BSA), 2006, {{ISBN|0-07-145545-0}}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = \left(A^0, \, A^1, \, A^2, \, A^3\right) \\ | |||

| & = A^0\mathbf{E}_0 + A^1 \mathbf{E}_1 + A^2 \mathbf{E}_2 + A^3 \mathbf{E}_3 \\ | |||

| & = A^0\mathbf{E}_0 + A^i \mathbf{E}_i \\ | |||

| & = A^\alpha\mathbf{E}_\alpha | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| where ''A<sup>α</sup>'' is the magnitude component and '''E'''<sub>α</sub> is the ] component; note that both are necessary to make a vector, and that when ''A<sup>α</sup>'' is seen alone, it refers strictly to the <em>components</em> of the vector. | |||

| The upper indices indicate ] components. Here the standard convention is that Latin indices take values for spatial components, so that ''i'' = 1, 2, 3, and Greek indices take values for space ''and time'' components, so ''α'' = 0, 1, 2, 3, used with the ]. The split between the time component and the spatial components is a useful one to make when determining contractions of one four vector with other tensor quantities, such as for calculating Lorentz invariants in inner products (examples are given below), or ]. | |||

| In special relativity, the spacelike basis '''E'''<sub>1</sub>, '''E'''<sub>2</sub>, '''E'''<sub>3</sub> and components ''A''<sup>1</sup>, ''A''<sup>2</sup>, ''A''<sup>3</sup> are often ] basis and components: | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = \left(A_t, \, A_x, \, A_y, \, A_z\right) \\ | |||

| & = A_t \mathbf{E}_t + A_x \mathbf{E}_x + A_y \mathbf{E}_y + A_z \mathbf{E}_z \\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| although, of course, any other basis and components may be used, such as ] | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = \left(A_t, \, A_r, \, A_\theta, \, A_\phi\right) \\ | |||

| & = A_t \mathbf{E}_t + A_r \mathbf{E}_r + A_\theta \mathbf{E}_\theta + A_\phi \mathbf{E}_\phi \\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| or ], | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = (A_t, \, A_r, \, A_\theta, \, A_z) \\ | |||

| & = A_t \mathbf{E}_t + A_r \mathbf{E}_r + A_\theta \mathbf{E}_\theta + A_z \mathbf{E}_z \\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| or any other ], or even general ]. Note the coordinate labels are always subscripted as labels and are not indices taking numerical values. In general relativity, local curvilinear coordinates in a local basis must be used. Geometrically, a four-vector can still be interpreted as an arrow, but in spacetime - not just space. In relativity, the arrows are drawn as part of ] (also called ''spacetime diagram''). In this article, four-vectors will be referred to simply as vectors. | |||

| It is also customary to represent the bases by ]s: | |||

| <math display="block"> | |||

| \mathbf{E}_0 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \,,\quad | |||

| \mathbf{E}_1 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \,,\quad | |||

| \mathbf{E}_2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{pmatrix} \,,\quad | |||

| \mathbf{E}_3 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{pmatrix} | |||

| </math> | |||

| so that: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} A^0 \\ A^1 \\ A^2 \\ A^3 \end{pmatrix} </math> | |||

| The relation between the ] and contravariant coordinates is through the ] ] (referred to as the metric), ''η'' which ] as follows: | |||

| <math display="block">A_{\mu} = \eta_{\mu \nu} A^{\nu} \,, </math> | |||

| and in various equivalent notations the covariant components are: | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = (A_0, \, A_1, \, A_2, \, A_3) \\ | |||

| & = A_0\mathbf{E}^0 + A_1 \mathbf{E}^1 + A_2 \mathbf{E}^2 + A_3 \mathbf{E}^3 \\ | |||

| & = A_0\mathbf{E}^0 + A_i \mathbf{E}^i \\ | |||

| & = A_\alpha\mathbf{E}^\alpha\\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| where the lowered index indicates it to be ]. Often the metric is diagonal, as is the case for ] (see ]), but not in general ]. | |||

| The bases can be represented by ]s: | |||

| <math display="block"> | |||

| \mathbf{E}^0 = \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \,,\quad | |||

| \mathbf{E}^1 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \,,\quad | |||

| \mathbf{E}^2 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} \,,\quad | |||

| \mathbf{E}^3 = \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} | |||

| </math> | |||

| so that: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A} = \begin{pmatrix} A_0 & A_1 & A_2 & A_3 \end{pmatrix} </math> | |||

| The motivation for the above conventions are that the inner product is a scalar, see below for details. | |||

| === Lorentz transformation === | |||

| {{main|Lorentz transformation}} | |||

| Given two inertial or rotated ], a four-vector is defined as a quantity which transforms according to the ] matrix '''Λ''': | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A}' = \boldsymbol{\Lambda}\mathbf{A}</math> | |||

| In index notation, the contravariant and covariant components transform according to, respectively: | |||

| <math display="block">{A'}^\mu = \Lambda^\mu {}_\nu A^\nu \,, \quad{A'}_\mu = \Lambda_\mu {}^\nu A_\nu</math> | |||

| in which the matrix {{math|'''Λ'''}} has components {{math|Λ''<sup>μ</sup><sub>ν</sub>''}} in row {{math|''μ''}} and column {{math|''ν''}}, and the matrix {{math|('''Λ'''<sup>−1</sup>)<sup>T</sup>}} has components {{math|Λ''<sub>μ</sub><sup>ν</sup>''}} in row {{math|''μ''}} and column {{math|''ν''}}. | |||

| For background on the nature of this transformation definition, see ]. All four-vectors transform in the same way, and this can be generalized to four-dimensional relativistic tensors; see ]. | |||

| ====Pure rotations about an arbitrary axis ==== | |||

| For two frames rotated by a fixed angle {{math|''θ''}} about an axis defined by the ]: | |||

| <math display="block">\hat{\mathbf{n}} = \left(\hat{n}_1, \hat{n}_2, \hat{n}_3\right)\,,</math> | |||

| without any boosts, the matrix '''Λ''' has components given by:<ref>{{cite book| author=C.B. Parker| title=McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics| publisher=McGraw Hill| edition=2nd| page=| year=1994| isbn=0-07-051400-3| url-access=registration| url=https://archive.org/details/mcgrawhillencycl1993park/page/1333}}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

| \Lambda_{00} &= 1 \\ | |||

| \Lambda_{0i} = \Lambda_{i0} &= 0 \\ | |||

| \Lambda_{ij} &= \left(\delta_{ij} - \hat{n}_i \hat{n}_j\right) \cos\theta - \varepsilon_{ijk} \hat{n}_k \sin\theta + \hat{n}_i \hat{n}_j | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| where ''δ<sub>ij</sub>'' is the ], and ''ε<sub>ijk</sub>'' is the ] ]. The spacelike components of four-vectors are rotated, while the timelike components remain unchanged. | |||

| For the case of rotations about the ''z''-axis only, the spacelike part of the Lorentz matrix reduces to the ] about the ''z''-axis: | |||

| <math display="block"> | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| {A'}^0 \\ {A'}^1 \\ {A'}^2 \\ {A'}^3 | |||

| \end{pmatrix} = | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & \cos\theta & -\sin\theta & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & \sin\theta & \cos\theta & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ | |||

| \end{pmatrix} | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| A^0 \\ A^1 \\ A^2 \\ A^3 | |||

| \end{pmatrix}\ . | |||

| </math> | |||

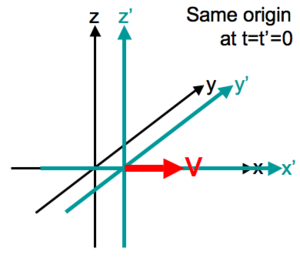

| ====Pure boosts in an arbitrary direction==== | |||

| ] | |||

| For two frames moving at constant relative three-velocity '''v''' (not four-velocity, ]), it is convenient to denote and define the relative velocity in units of ''c'' by: | |||

| <math display="block"> \boldsymbol{\beta} = (\beta_1,\,\beta_2,\,\beta_3) = \frac{1}{c}(v_1,\,v_2,\,v_3) = \frac{1}{c}\mathbf{v} \,. </math> | |||

| Then without rotations, the matrix '''Λ''' has components given by:<ref>Gravitation, J.B. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne, W.H. Freeman & Co, 1973, ISAN 0-7167-0344-0</ref> | |||

| <math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

| \Lambda_{00} &= \gamma, \\ | |||

| \Lambda_{0i} = \Lambda_{i0} &= -\gamma \beta_{i}, \\ | |||

| \Lambda_{ij} = \Lambda_{ji} &= (\gamma - 1)\frac{\beta_{i}\beta_{j}}{\beta^2} + \delta_{ij} = (\gamma - 1)\frac{v_i v_j}{v^2} + \delta_{ij}, \\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| where the ] is defined by: | |||

| <math display="block">\gamma = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \boldsymbol{\beta}\cdot\boldsymbol{\beta}}} \,,</math> | |||

| and {{math|''δ<sub>ij</sub>''}} is the ]. Contrary to the case for pure rotations, the spacelike and timelike components are mixed together under boosts. | |||

| For the case of a boost in the ''x''-direction only, the matrix reduces to;<ref>Dynamics and Relativity, J.R. Forshaw, B.G. Smith, Wiley, 2009, ISAN 978-0-470-01460-8</ref><ref>Relativity DeMystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (ASB), 2006, ISAN 0-07-145545-0</ref> | |||

| <math display="block"> | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| A'^0 \\ A'^1 \\ A'^2 \\ A'^3 | |||

| \end{pmatrix} = | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| \cosh\phi &-\sinh\phi & 0 & 0 \\ | |||

| -\sinh\phi & \cosh\phi & 0 & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \\ | |||

| \end{pmatrix} | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| A^0 \\ A^1 \\ A^2 \\ A^3 | |||

| \end{pmatrix} | |||

| </math> | |||

| Where the ] {{math|''ϕ''}} expression has been used, written in terms of the ]s: | |||

| <math display="block">\gamma = \cosh \phi</math> | |||

| This Lorentz matrix illustrates the boost to be a '']'' in four dimensional spacetime, analogous to the circular rotation above in three-dimensional space. | |||

| ===Properties=== | |||

| ====Linearity==== | |||

| Four-vectors have the same ] as ]s in ]. They can be added in the usual entrywise way: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} + \mathbf{B} = \left(A^0, A^1, A^2, A^3\right) + \left(B^0, B^1, B^2, B^3\right) = \left(A^0 + B^0, A^1 + B^1, A^2 + B^2, A^3 + B^3\right)</math> | |||

| and similarly ] by a ] ''λ'' is defined entrywise by: | |||

| <math display="block">\lambda\mathbf{A} = \lambda\left(A^0, A^1, A^2, A^3\right) = \left(\lambda A^0, \lambda A^1, \lambda A^2, \lambda A^3\right)</math> | |||

| Then subtraction is the inverse operation of addition, defined entrywise by: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} + (-1)\mathbf{B} = \left(A^0, A^1, A^2, A^3\right) + (-1)\left(B^0, B^1, B^2, B^3\right) = \left(A^0 - B^0, A^1 - B^1, A^2 - B^2, A^3 - B^3\right)</math> | |||

| ====Minkowski tensor==== | |||

| {{See also|spacetime interval}} | |||

| Applying the ] {{math|''η<sub>μν</sub>''}} to two four-vectors {{math|'''A'''}} and {{math|'''B'''}}, writing the result in ] notation, we have, using ]: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B} = A^{\mu} B^{\nu} \mathbf{E}_{\mu} \cdot \mathbf{E}_{\nu} = A^{\mu} \eta_{\mu \nu} B^{\nu} </math> | |||

| in special relativity. The dot product of the basis vectors is the Minkowski metric, as opposed to the Kronecker delta as in Euclidean space. It is convenient to rewrite the definition in ] form: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A \cdot B} = \begin{pmatrix} A^0 & A^1 & A^2 & A^3 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} \eta_{00} & \eta_{01} & \eta_{02} & \eta_{03} \\ \eta_{10} & \eta_{11} & \eta_{12} & \eta_{13} \\ \eta_{20} & \eta_{21} & \eta_{22} & \eta_{23} \\ \eta_{30} & \eta_{31} & \eta_{32} & \eta_{33} \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} B^0 \\ B^1 \\ B^2 \\ B^3 \end{pmatrix} </math> | |||

| in which case {{math|''η<sub>μν</sub>''}} above is the entry in row {{math|''μ''}} and column {{math|''ν''}} of the Minkowski metric as a square matrix. The Minkowski metric is not a ], because it is indefinite (see ]). A number of other expressions can be used because the metric tensor can raise and lower the components of {{math|'''A'''}} or {{math|'''B'''}}. For contra/co-variant components of {{math|'''A'''}} and co/contra-variant components of {{math|'''B'''}}, we have: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B} = A^{\mu} \eta_{\mu \nu} B^{\nu} = A_{\nu} B^{\nu} = A^{\mu} B_{\mu} </math> | |||

| so in the matrix notation: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B} | |||

| = \begin{pmatrix} A_0 & A_1 & A_2 & A_3 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} B^0 \\ B^1 \\ B^2 \\ B^3 \end{pmatrix} | |||

| = \begin{pmatrix} B_0 & B_1 & B_2 & B_3 \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} A^0 \\ A^1 \\ A^2 \\ A^3 \end{pmatrix} | |||

| </math> | |||

| while for {{math|'''A'''}} and {{math|'''B'''}} each in covariant components: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B} = A_{\mu} \eta^{\mu \nu} B_{\nu}</math> | |||

| with a similar matrix expression to the above. | |||

| Applying the Minkowski tensor to a four-vector '''A''' with itself we get: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A \cdot A} = A^\mu \eta_{\mu\nu} A^\nu </math> | |||

| which, depending on the case, may be considered the square, or its negative, of the length of the vector. | |||

| Following are two common choices for the metric tensor in the ] (essentially Cartesian coordinates). If orthogonal coordinates are used, there would be scale factors along the diagonal part of the spacelike part of the metric, while for general curvilinear coordinates the entire spacelike part of the metric would have components dependent on the curvilinear basis used. | |||

| =====Standard basis, (+−−−) signature===== | |||

| The (+−−−) ] is sometimes called the "mostly minus" convention, or the "west coast" convention. | |||

| In the (+−−−) ], evaluating the ] gives: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} \cdot \mathbf{B} = A^0 B^0 - A^1 B^1 - A^2 B^2 - A^3 B^3 </math> | |||

| while in matrix form: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A \cdot B} | |||

| = \begin{pmatrix} A^0 & A^1 & A^2 & A^3 \end{pmatrix} | |||

| \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & 0 & -1 & 0 \\ | |||

| 0 & 0 & 0 & -1 | |||

| \end{pmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} B^0 \\ B^1 \\ B^2 \\ B^3 \end{pmatrix} | |||

| </math> | |||

| It is a recurring theme in special relativity to take the expression | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A}\cdot\mathbf{B} = A^0 B^0 - A^1 B^1 - A^2 B^2 - A^3 B^3 = C</math> | |||

| in one ], where ''C'' is the value of the inner product in this frame, and: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A}'\cdot\mathbf{B}' = {A'}^0 {B'}^0 - {A'}^1 {B'}^1 - {A'}^2 {B'}^2 - {A'}^3 {B'}^3 = C' </math> | |||

| in another frame, in which ''C''′ is the value of the inner product in this frame. Then since the inner product is an invariant, these must be equal: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A}\cdot\mathbf{B} = \mathbf{A}'\cdot\mathbf{B}' </math> | |||

| that is: | |||

| <math display="block"> C = A^0 B^0 - A^1 B^1 - A^2 B^2 - A^3 B^3 = {A'}^0 {B'}^0 - {A'}^1 {B'}^1 - {A'}^2 {B'}^2 - {A'}^3{B'}^3 </math> | |||

| Considering that physical quantities in relativity are four-vectors, this equation has the appearance of a "]", but there is no "conservation" involved. The primary significance of the Minkowski inner product is that for any two four-vectors, its value is ] for all observers; a change of coordinates does not result in a change in value of the inner product. The components of the four-vectors change from one frame to another; '''A''' and '''A'''′ are connected by a ], and similarly for '''B''' and '''B'''′, although the inner products are the same in all frames. Nevertheless, this type of expression is exploited in relativistic calculations on a par with conservation laws, since the magnitudes of components can be determined without explicitly performing any Lorentz transformations. A particular example is with energy and momentum in the ] derived from the ] vector (see also below). | |||

| In this signature we have: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A \cdot A} = \left(A^0\right)^2 - \left(A^1\right)^2 - \left(A^2\right)^2 - \left(A^3\right)^2 </math> | |||

| With the signature (+−−−), four-vectors may be classified as either ] if <math>\mathbf{A \cdot A} < 0</math>, ] if <math>\mathbf{A \cdot A} > 0</math>, and ]s if <math>\mathbf{A \cdot A} = 0</math>. | |||

| =====Standard basis, (−+++) signature===== | |||

| The (-+++) ] is sometimes called the "east coast" convention. | |||

| Some authors define ''η'' with the opposite sign, in which case we have the (−+++) metric signature. Evaluating the summation with this signature: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A \cdot B} = - A^0 B^0 + A^1 B^1 + A^2 B^2 + A^3 B^3 </math> | |||

| while the matrix form is: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A \cdot B} = \left( \begin{matrix}A^0 & A^1 & A^2 & A^3 \end{matrix} \right) | |||

| \left( \begin{matrix} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{matrix} \right) | \left( \begin{matrix} -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 \end{matrix} \right) | ||

| \left( \begin{matrix} |

\left( \begin{matrix}B^0 \\ B^1 \\ B^2 \\ B^3 \end{matrix} \right) </math> | ||

| = | |||

| Note that in this case, in one frame: | |||

| -a_0 b_0 + a_1 b_1 + a_2 b_2 + a_3 b_3 | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A}\cdot\mathbf{B} = - A^0 B^0 + A^1 B^1 + A^2 B^2 + A^3 B^3 = -C </math> | |||

| while in another: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A}'\cdot\mathbf{B}' = - {A'}^0 {B'}^0 + {A'}^1 {B'}^1 + {A'}^2 {B'}^2 + {A'}^3 {B'}^3 = -C'</math> | |||

| so that: | |||

| <math display="block"> -C = - A^0 B^0 + A^1 B^1 + A^2 B^2 + A^3 B^3 = - {A'}^0 {B'}^0 + {A'}^1 {B'}^1 + {A'}^2 {B'}^2 + {A'}^3 {B'}^3</math> | |||

| which is equivalent to the above expression for ''C'' in terms of '''A''' and '''B'''. Either convention will work. With the Minkowski metric defined in the two ways above, the only difference between covariant and contravariant four-vector components are signs, therefore the signs depend on which sign convention is used. | |||

| We have: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{A \cdot A} = - \left(A^0\right)^2 + \left(A^1\right)^2 + \left(A^2\right)^2 + \left(A^3\right)^2 </math> | |||

| With the signature (−+++), four-vectors may be classified as either ] if <math>\mathbf{A \cdot A} > 0</math>, ] if <math>\mathbf{A \cdot A} < 0</math>, and ] if <math>\mathbf{A \cdot A} = 0</math>. | |||

| =====Dual vectors===== | |||

| Applying the Minkowski tensor is often expressed as the effect of the ] of one vector on the other: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A \cdot B} = A^*(\mathbf{B}) = A{_\nu}B^{\nu}. </math> | |||

| Here the ''A<sub>ν</sub>''s are the components of the dual vector '''A'''* of '''A''' in the ] and called the ] coordinates of '''A''', while the original ''A<sup>ν</sup>'' components are called the ] coordinates. | |||

| == Four-vector calculus == | |||

| ===Derivatives and differentials=== | |||

| In special relativity (but not general relativity), the ] of a four-vector with respect to a scalar ''λ'' (invariant) is itself a four-vector. It is also useful to take the ] of the four-vector, ''d'''''A''' and divide it by the differential of the scalar, ''dλ'': | |||

| <math display="block">\underset{\text{differential}}{d\mathbf{A}} = \underset{\text{derivative}}{\frac{d\mathbf{A}}{d\lambda}} \underset{\text{differential}}{d\lambda} </math> | |||

| where the contravariant components are: | |||

| <math display="block"> d\mathbf{A} = \left(dA^0, dA^1, dA^2, dA^3\right) </math> | |||

| while the covariant components are: | |||

| <math display="block"> d\mathbf{A} = \left(dA_0, dA_1, dA_2, dA_3\right) </math> | |||

| In relativistic mechanics, one often takes the differential of a four-vector and divides by the differential in ] (see below). | |||

| ==Fundamental four-vectors== | |||

| ===Four-position{{anchor|Position}}=== | |||

| A point in ] is a time and spatial position, called an "event", or sometimes the '''position four-vector''' or '''four-position''' or '''4-position''', described in some reference frame by a set of four coordinates: | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{R} = \left(ct, \mathbf{r}\right) </math> | |||

| where '''r''' is the ] ]. If '''r''' is a function of coordinate time ''t'' in the same frame, i.e. '''r''' = '''r'''(''t''), this corresponds to a sequence of events as ''t'' varies. The definition ''R''<sup>0</sup> = ''ct'' ensures that all the coordinates have the same ] (of ]) and units (in the ], meters).<ref name="e561">{{cite web | title=Details for IEV number 113-07-19: "position four-vector" | website=International Electrotechnical Vocabulary | url=https://www.electropedia.org/iev/iev.nsf/display?openform&ievref=113-07-19 | language=ja | access-date=2024-09-08}}</ref><ref>Jean-Bernard Zuber & Claude Itzykson, ''Quantum Field Theory'', pg 5, {{ISBN|0-07-032071-3}}</ref><ref>], ] & ],''Gravitation'', pg 51, {{ISBN|0-7167-0344-0}}</ref><ref>], ''An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory'', pg 4, {{ISBN|0-521-31132-2}}</ref> These coordinates are the components of the ''position four-vector'' for the event. | |||

| The '''displacement four-vector''' is defined to be an "arrow" linking two events: | |||

| <math display="block"> \Delta \mathbf{R} = \left(c\Delta t, \Delta \mathbf{r} \right) </math> | |||

| For the ] four-position on a world line we have, using ]: | |||

| <math display="block">\|d\mathbf{R}\|^2 = \mathbf{dR \cdot dR} = dR^\mu dR_\mu = c^2d\tau^2 = ds^2 \,,</math> | |||

| defining the differential ] d''s'' and differential proper time increment d''τ'', but this "norm" is also: | |||

| <math display="block">\|d\mathbf{R}\|^2 = (cdt)^2 - d\mathbf{r}\cdot d\mathbf{r} \,,</math> | |||

| so that: | |||

| <math display="block">(c d\tau)^2 = (cdt)^2 - d\mathbf{r}\cdot d\mathbf{r} \,.</math> | |||

| When considering physical phenomena, differential equations arise naturally; however, when considering space and ]s of functions, it is unclear which reference frame these derivatives are taken with respect to. It is agreed that time derivatives are taken with respect to the ] <math>\tau</math>. As proper time is an invariant, this guarantees that the proper-time-derivative of any four-vector is itself a four-vector. It is then important to find a relation between this proper-time-derivative and another time derivative (using the ] ''t'' of an inertial reference frame). This relation is provided by taking the above differential invariant spacetime interval, then dividing by (''cdt'')<sup>2</sup> to obtain: | |||

| <math display="block">\left(\frac{cd\tau}{cdt}\right)^2 | |||

| = 1 - \left(\frac{d\mathbf{r}}{cdt}\cdot \frac{d\mathbf{r}}{cdt}\right) | |||

| = 1 - \frac{\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{u}}{c^2} = \frac{1}{\gamma(\mathbf{u})^2} \,, | |||

| </math> | </math> | ||

| where '''u''' = ''d'''''r'''/''dt'' is the coordinate 3-] of an object measured in the same frame as the coordinates ''x'', ''y'', ''z'', and ] ''t'', and | |||

| Strictly speaking, this is not a proper ] because ''x'' · ''x'' < 0 for some ''x''. Like the ordinary ] of three-vectors, however, the result of this scalar product is a ]: it is ] under any Lorentz transformation. (This property is sometimes use to ''define'' the Lorentz group.) The 4×4 matrix in the above definition is called the ''metric tensor'', sometimes denoted by '''g'''; its sign is a matter of convention, and some authors multiply it by −1. See ]. | |||

| <math display="block">\gamma(\mathbf{u}) = \frac{1}{\sqrt{1 - \frac{\mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{u}}{c^2}}}</math> | |||

| is the ]. This provides a useful relation between the differentials in coordinate time and proper time: | |||

| <math display="block">dt = \gamma(\mathbf{u})d\tau \,.</math> | |||

| This relation can also be found from the time transformation in the ]s. | |||

| Important four-vectors in relativity theory can be defined by applying this differential <math>\frac{d}{d\tau}</math>. | |||

| ===Four-gradient=== | |||

| Considering that ]s are ]s, one can form a ] from the partial ] {{math|∂}}/{{math|∂}}''t'' and the spatial ] ∇. Using the standard basis, in index and abbreviated notations, the contravariant components are: | |||

| <math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

| \boldsymbol{\partial} & = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x_0}, \, -\frac{\partial }{\partial x_1}, \, -\frac{\partial }{\partial x_2}, \, -\frac{\partial }{\partial x_3} \right) \\ | |||

| & = (\partial^0, \, - \partial^1, \, - \partial^2, \, - \partial^3) \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}_0\partial^0 - \mathbf{E}_1\partial^1 - \mathbf{E}_2\partial^2 - \mathbf{E}_3\partial^3 \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}_0\partial^0 - \mathbf{E}_i\partial^i \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}_\alpha \partial^\alpha \\ | |||

| & = \left(\frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial}{\partial t} , \, - \nabla \right) \\ | |||

| & = \left(\frac{\partial_t}{c},- \nabla \right) \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}_0\frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial}{\partial t} - \nabla \\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| Note the basis vectors are placed in front of the components, to prevent confusion between taking the derivative of the basis vector, or simply indicating the partial derivative is a component of this four-vector. The covariant components are: | |||

| <math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

| \boldsymbol{\partial} & = \left(\frac{\partial }{\partial x^0}, \, \frac{\partial }{\partial x^1}, \, \frac{\partial }{\partial x^2}, \, \frac{\partial }{\partial x^3} \right) \\ | |||

| & = (\partial_0, \, \partial_1, \, \partial_2, \, \partial_3) \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}^0\partial_0 + \mathbf{E}^1\partial_1 + \mathbf{E}^2\partial_2 + \mathbf{E}^3\partial_3 \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}^0\partial_0 + \mathbf{E}^i\partial_i \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}^\alpha \partial_\alpha \\ | |||

| & = \left(\frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial}{\partial t} , \, \nabla \right) \\ | |||

| & = \left(\frac{\partial_t}{c}, \nabla \right) \\ | |||

| & = \mathbf{E}^0\frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial}{\partial t} + \nabla \\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| Since this is an operator, it doesn't have a "length", but evaluating the inner product of the operator with itself gives another operator: | |||

| <math display="block">\partial^\mu \partial_\mu = \frac{1}{c^2}\frac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2} - \nabla^2 = \frac{{\partial_t}^2}{c^2} - \nabla^2</math> | |||

| called the ]. | |||

| ==Kinematics== | |||

| === Four-velocity === | |||

| {{Main|Four-velocity}} | |||

| The ] of a particle is defined by: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{U} = \frac{d\mathbf{X}}{d \tau} = \frac{d\mathbf{X}}{dt}\frac{dt}{d \tau} = \gamma(\mathbf{u})\left(c, \mathbf{u}\right),</math> | |||

| Geometrically, '''U''' is a normalized vector tangent to the ] of the particle. Using the differential of the four-position, the magnitude of the four-velocity can be obtained: | |||

| <math display="block">\|\mathbf{U}\|^2 = U^\mu U_\mu = \frac{dX^\mu}{d\tau} \frac{dX_\mu}{d\tau} = \frac{dX^\mu dX_\mu}{d\tau^2} = c^2 \,,</math> | |||

| in short, the magnitude of the four-velocity for any object is always a fixed constant: | |||

| <math display="block">\| \mathbf{U} \|^2 = c^2 </math> | |||

| The norm is also: | |||

| <math display="block">\|\mathbf{U}\|^2 = {\gamma(\mathbf{u})}^2 \left( c^2 - \mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{u} \right) \,,</math> | |||

| so that: | |||

| <math display="block">c^2 = {\gamma(\mathbf{u})}^2 \left( c^2 - \mathbf{u}\cdot\mathbf{u} \right) \,,</math> | |||

| which reduces to the definition of the ]. | |||

| Units of four-velocity are m/s in ] and 1 in the ]. Four-velocity is a contravariant vector. | |||

| === Four-acceleration === | |||

| The ] is given by: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} = \frac{d\mathbf{U} }{d \tau} = \gamma(\mathbf{u}) \left(\frac{d{\gamma}(\mathbf{u})}{dt} c, \frac{d{\gamma}(\mathbf{u})}{dt} \mathbf{u} + \gamma(\mathbf{u}) \mathbf{a} \right).</math> | |||

| where '''a''' = ''d'''''u'''/''dt'' is the coordinate 3-acceleration. Since the magnitude of '''U''' is a constant, the four acceleration is orthogonal to the four velocity, i.e. the Minkowski inner product of the four-acceleration and the four-velocity is zero: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A}\cdot\mathbf{U} = A^\mu U_\mu = \frac{dU^\mu}{d\tau} U_\mu = \frac{1}{2} \, \frac{d}{d\tau} \left(U^\mu U_\mu\right) = 0 \,</math> | |||

| which is true for all world lines. The geometric meaning of four-acceleration is the ] of the world line in Minkowski space. | |||

| ==Dynamics== | |||

| === Four-momentum === | |||

| For a massive particle of ] (or ]) ''m''<sub>0</sub>, the ] is given by: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{P} = m_0 \mathbf{U} = m_0\gamma(\mathbf{u})(c, \mathbf{u}) = \left(\frac{E}{c}, \mathbf{p}\right)</math> | |||

| where the total energy of the moving particle is: | |||

| <math display="block">E = \gamma(\mathbf{u}) m_0 c^2 </math> | |||

| and the total ] is: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{p} = \gamma(\mathbf{u}) m_0 \mathbf{u} </math> | |||

| Taking the inner product of the four-momentum with itself: | |||

| <math display="block">\|\mathbf{P}\|^2 = P^\mu P_\mu = m_0^2 U^\mu U_\mu = m_0^2 c^2</math> | |||

| and also: | |||

| <math display="block">\|\mathbf{P}\|^2 = \frac{E^2}{c^2} - \mathbf{p}\cdot\mathbf{p}</math> | |||

| which leads to the ]: | |||

| <math display="block">E^2 = c^2 \mathbf{p}\cdot\mathbf{p} + \left(m_0 c^2\right)^2 \,.</math> | |||

| This last relation is useful in ], essential in ] and ], all with applications to ]. | |||

| === Four-force === | |||

| The ] acting on a particle is defined analogously to the 3-force as the time derivative of 3-momentum in ]: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{F} = \frac {d \mathbf{P}} {d \tau} = \gamma(\mathbf{u})\left(\frac{1}{c}\frac{dE}{dt}, \frac{d\mathbf{p}}{dt}\right) = \gamma(\mathbf{u})\left(\frac{P}{c}, \mathbf{f}\right)</math> | |||

| where ''P'' is the ] transferred to move the particle, and '''f''' is the 3-force acting on the particle. For a particle of constant invariant mass ''m''<sub>0</sub>, this is equivalent to | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{F} = m_0 \mathbf{A} = m_0\gamma(\mathbf{u})\left( \frac{d{\gamma}(\mathbf{u})}{dt} c, \left(\frac{d{\gamma}(\mathbf{u})}{dt} \mathbf{u} + \gamma(\mathbf{u}) \mathbf{a}\right) \right)</math> | |||

| An invariant derived from the four-force is: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{F}\cdot\mathbf{U} = F^\mu U_\mu = m_0 A^\mu U_\mu = 0</math> | |||

| from the above result. | |||

| ==Thermodynamics== | |||

| {{see also|Relativistic heat conduction}} | |||

| ===Four-heat flux=== | |||

| The four-heat flux vector field, is essentially similar to the 3d ] vector field '''q''', in the local frame of the fluid:<ref>{{Cite journal |first1=Y. M. |last1=Ali |first2=L. C. |last2=Zhang |title=Relativistic heat conduction |journal=Int. J. Heat Mass Trans. |volume=48 |year=2005 |issue=12 |pages=2397–2406 |doi=10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2005.02.003 }}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{Q} = -k \boldsymbol{\partial} T = -k\left( \frac{1}{c}\frac{\partial T}{\partial t}, \nabla T\right) </math> | |||

| where ''T'' is ] and ''k'' is ]. | |||

| ===Four-baryon number flux=== | |||

| The flux of baryons is:<ref>{{Cite book|title=Gravitation|url=https://archive.org/details/gravitation00misn_003|url-access=limited | author1=J.A. Wheeler |author2=C. Misner |author3=K.S. Thorne |publisher=W.H. Freeman & Co|year=1973|pages=–559|isbn=0-7167-0344-0}}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{S} = n\mathbf{U}</math> | |||

| where {{math|''n''}} is the ] of ]s in the local ] of the baryon fluid (positive values for baryons, negative for ]baryons), and {{math|'''U'''}} the ] field (of the fluid) as above. | |||

| ===Four-entropy=== | |||

| The four-] vector is defined by:<ref>{{Cite book|title=Gravitation|url=https://archive.org/details/gravitation00misn_003| url-access=limited|author1=J.A. Wheeler |author2=C. Misner |author3=K.S. Thorne |publisher=W.H. Freeman & Co| year=1973| page=|isbn=0-7167-0344-0}}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{s} = s\mathbf{S} + \frac{\mathbf{Q}}{T}</math> | |||

| where {{math|''s''}} is the entropy per baryon, and {{mvar|T}} the ], in the local rest frame of the fluid.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Gravitation|url=https://archive.org/details/gravitation00misn_003|url-access=limited|author1=J.A. Wheeler |author2=C. Misner |author3=K.S. Thorne |publisher=W.H. Freeman & Co|year=1973|page=|isbn=0-7167-0344-0}}</ref> | |||

| ==Electromagnetism== | |||

| Examples of four-vectors in ] include the following. | |||

| ===Four-current=== | |||

| The electromagnetic ] (or more correctly a four-current density)<ref>{{cite book | |||

| |title=Introduction to Special Relativity | |||

| |edition=2nd | |||

| |first1=Wolfgang | |||

| |last1=Rindler | |||

| |publisher=Oxford Science Publications | |||

| |year=1991 | |||

| |isbn=0-19-853952-5 | |||

| |pages=103–107 | |||

| |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=YKUPAQAAMAAJ | |||

| }}</ref> is defined by | |||

| <math display="block"> \mathbf{J} = \left( \rho c, \mathbf{j} \right) </math> | |||

| formed from the ] '''j''' and ] ''ρ''. | |||

| ===Four-potential=== | |||

| The ] (or more correctly a four-EM vector potential) defined by | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A} = \left( \frac{\phi}{c}, \mathbf{a} \right)</math> | |||

| formed from the ] {{math|'''a'''}} and the scalar potential {{math|''ϕ''}}. | |||

| The four-potential is not uniquely determined, because it depends on a choice of ]. | |||

| In the ] for the electromagnetic field: | |||

| * In vacuum, <math display="block">(\boldsymbol{\partial} \cdot \boldsymbol{\partial}) \mathbf{A} = 0</math> | |||

| * With a ] source and using the ] <math>(\boldsymbol{\partial} \cdot \mathbf{A}) = 0</math>, <math display="block">(\boldsymbol{\partial} \cdot \boldsymbol{\partial}) \mathbf{A} = \mu_0 \mathbf{J}</math> | |||

| ==Waves== | |||

| ===Four-frequency=== | |||

| A photonic ] can be described by the '']'', defined as | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{N} = \nu\left(1 , \hat{\mathbf{n}} \right)</math> | |||

| where {{mvar|ν}} is the frequency of the wave and <math>\hat{\mathbf{n}}</math> is a ] in the travel direction of the wave. Now: | |||

| <math display="block">\|\mathbf{N}\| = N^\mu N_\mu = \nu ^2 \left(1 - \hat{\mathbf{n}}\cdot\hat{\mathbf{n}}\right) = 0</math> | |||

| so the four-frequency of a photon is always a null vector. | |||

| ===Four-wavevector=== | |||

| {{see also|De Broglie relation}} | |||

| The quantities reciprocal to time {{mvar|t}} and space '''{{math|r}}''' are the ] {{mvar|ω}} and ] '''{{math|k}}''', respectively. They form the components of the '''four-wavevector''' or '''wave four-vector''': | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{K} = \left(\frac{\omega}{c}, \vec{\mathbf{k}}\right) = \left(\frac{\omega}{c}, \frac{\omega}{v_p} \hat\mathbf{n}\right) \,.</math> | |||

| The wave four-vector has ] of ] in the SI.<ref name="o144">{{cite web | title=Details for IEV number 113-07-57: "four-wave vector" | website=International Electrotechnical Vocabulary | url=https://www.electropedia.org/iev/iev.nsf/display?openform&ievref=113-07-57 | language=ja | access-date=2024-09-08}}</ref> | |||

| A wave packet of nearly ] light can be described by: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{K} = \frac{2\pi}{c}\mathbf{N} = \frac{2\pi}{c} \nu\left(1,\hat{\mathbf{n}}\right) = \frac{\omega}{c} \left(1, \hat{\mathbf{n}}\right) ~.</math> | |||

| The de Broglie relations then showed that four-wavevector applied to ]s as well as to light waves: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{P} = \hbar \mathbf{K} = \left(\frac{E}{c},\vec{p}\right) = \hbar \left(\frac{\omega}{c},\vec{k} \right) ~.</math> | |||

| yielding <math>E = \hbar \omega</math> and <math>\vec{p} = \hbar \vec{k}</math>, where {{mvar|ħ}} is the ] divided by {{math|2''π''}} . | |||

| The square of the norm is: | |||

| <math display="block">\| \mathbf{K} \|^2 = K^\mu K_\mu = \left(\frac{\omega}{c}\right)^2 - \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{k} \,,</math> | |||

| and by the de Broglie relation: | |||

| <math display="block">\| \mathbf{K} \|^2 = \frac{1}{\hbar^2} \| \mathbf{P} \|^2 = \left(\frac{m_0 c}{\hbar}\right)^2 \,,</math> | |||

| we have the matter wave analogue of the energy–momentum relation: | |||

| <math display="block">\left(\frac{\omega}{c}\right)^2 - \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{k} = \left(\frac{m_0 c}{\hbar}\right)^2 ~.</math> | |||

| Note that for massless particles, in which case {{math|''m''<sub>0</sub> {{=}} 0}}, we have: | |||

| <math display="block">\left(\frac{\omega}{c}\right)^2 = \mathbf{k}\cdot\mathbf{k} \,,</math> | |||

| or {{math|‖'''k'''‖ {{=}} ''ω''/''c''}} . Note this is consistent with the above case; for photons with a 3-wavevector of modulus {{nobr|{{math|''ω / c''}} ,}} in the direction of wave propagation defined by the unit vector <math>\ \hat{\mathbf{n}} ~.</math> | |||

| ==Quantum theory== | |||

| ===Four-probability current=== | |||

| In ], the four-] or probability four-current is analogous to the ]:<ref>Vladimir G. Ivancevic, Tijana T. Ivancevic (2008) ''Quantum leap: from Dirac and Feynman, across the universe, to human body and mind''. World Scientific Publishing Company, {{ISBN|978-981-281-927-7}}, </ref> | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{J} = (\rho c, \mathbf{j}) </math> | |||

| where {{math|''ρ''}} is the ] corresponding to the time component, and {{math|'''j'''}} is the ] vector. In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, this current is always well defined because the expressions for density and current are positive definite and can admit a probability interpretation. In ] and ], it is not always possible to find a current, particularly when interactions are involved. | |||

| Replacing the energy by the ] and the momentum by the ] in the four-momentum, one obtains the ], used in ]s. | |||

| ===Four-spin=== | |||

| The ] of a particle is defined in the rest frame of a particle to be | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{S} = (0, \mathbf{s})</math> | |||

| where {{math|'''s'''}} is the ] pseudovector. In quantum mechanics, not all three components of this vector are simultaneously measurable, only one component is. The timelike component is zero in the particle's rest frame, but not in any other frame. This component can be found from an appropriate Lorentz transformation. | |||

| The norm squared is the (negative of the) magnitude squared of the spin, and according to quantum mechanics we have | |||

| <math display="block">\|\mathbf{S}\|^2 = -|\mathbf{s}|^2 = -\hbar^2 s(s + 1)</math> | |||

| This value is observable and quantized, with {{math|''s''}} the ] (not the magnitude of the spin vector). | |||

| ==Other formulations== | |||

| ===Four-vectors in the algebra of physical space=== | |||

| A four-vector ''A'' can also be defined in using the ] as a ], again in various equivalent notations:<ref>{{cite book |pages= 1142–1143|author1=J.A. Wheeler |author2=C. Misner |author3=K.S. Thorne | title=]| publisher=W.H. Freeman & Co| year=1973 | isbn=0-7167-0344-0}}</ref> | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = \left(A^0, \, A^1, \, A^2, \, A^3\right) \\ | |||

| & = A^0\boldsymbol{\sigma}_0 + A^1 \boldsymbol{\sigma}_1 + A^2 \boldsymbol{\sigma}_2 + A^3 \boldsymbol{\sigma}_3 \\ | |||

| & = A^0\boldsymbol{\sigma}_0 + A^i \boldsymbol{\sigma}_i \\ | |||

| & = A^\alpha\boldsymbol{\sigma}_\alpha\\ | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| or explicitly: | |||

| <math display="block">\begin{align} | |||

| \mathbf{A} & = A^0\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1 \end{pmatrix} + | |||

| A^1\begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} + | |||

| A^2\begin{pmatrix} 0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{pmatrix} + | |||

| A^3\begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{pmatrix} \\ | |||

| & = \begin{pmatrix} | |||

| A^0 + A^3 & A^1 - i A^2 \\ | |||

| A^1 + i A^2 & A^0 - A^3 | |||

| \end{pmatrix} | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| and in this formulation, the four-vector is represented as a ] (the ] and ] of the matrix leaves it unchanged), rather than a real-valued column or row vector. The ] of the matrix is the modulus of the four-vector, so the determinant is an invariant: | |||

| <math display="block"> \begin{align} | |||

| |\mathbf{A}| & = \begin{vmatrix} | |||

| A^0 + A^3 & A^1 - i A^2 \\ | |||

| A^1 + i A^2 & A^0 - A^3 | |||

| \end{vmatrix} \\ | |||

| & = \left(A^0 + A^3\right)\left(A^0 - A^3\right) - \left(A^1 -i A^2\right)\left(A^1 + i A^2\right) \\ | |||

| & = \left(A^0\right)^2 - \left(A^1\right)^2 - \left(A^2\right)^2 - \left(A^3\right)^2 | |||

| \end{align}</math> | |||

| This idea of using the Pauli matrices as ]s is employed in the ], an example of a ]. | |||

| ===Four-vectors in spacetime algebra=== | |||

| In ], another example of Clifford algebra, the ] can also form a ]. (They are also called the Dirac matrices, owing to their appearance in the ]). There is more than one way to express the gamma matrices, detailed in that main article. | |||

| The ] is a shorthand for a four-vector '''A''' contracted with the gamma matrices: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{A}\!\!\!\!/ = A_\alpha \gamma^\alpha = A_0 \gamma^0 + A_1 \gamma^1 + A_2 \gamma^2 + A_3 \gamma^3 </math> | |||

| The four-momentum contracted with the gamma matrices is an important case in ] and ]. In the Dirac equation and other ]s, terms of the form: | |||

| <math display="block">\mathbf{P}\!\!\!\!/ = P_\alpha \gamma^\alpha = P_0 \gamma^0 + P_1 \gamma^1 + P_2 \gamma^2 + P_3 \gamma^3 = \dfrac{E}{c} \gamma^0 - p_x \gamma^1 - p_y \gamma^2 - p_z \gamma^3 </math> | |||

| appear, in which the energy {{mvar|E}} and momentum components {{math|(''p<sub>x</sub>'', ''p<sub>y</sub>'', ''p<sub>z</sub>'')}} are replaced by their respective ]s. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] for the number-flux four-vector | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == References == | |||

| The laws of ] are also postulated to be invariant under Lorentz transformations. An object in an inertial reference frame will perceive the universe as if the universe were Lorentz-transformed so that the perceiving object is stationary. | |||

| {{reflist}} | |||

| *Rindler, W. ''Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd edn.)'' (1991) Clarendon Press Oxford {{ISBN|0-19-853952-5}} | |||

| <!--Categories--> | |||

| See also: ], ], ], ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 20:57, 8 January 2025

4-dimensional vector in relativity Not to be confused with p-vector.

| Part of a series on |

| Spacetime |

|---|

|

| Spacetime concepts |

| General relativity |

| Classical gravity |

| Relevant mathematics |

In special relativity, a four-vector (or 4-vector, sometimes Lorentz vector) is an object with four components, which transform in a specific way under Lorentz transformations. Specifically, a four-vector is an element of a four-dimensional vector space considered as a representation space of the standard representation of the Lorentz group, the (1/2,1/2) representation. It differs from a Euclidean vector in how its magnitude is determined. The transformations that preserve this magnitude are the Lorentz transformations, which include spatial rotations and boosts (a change by a constant velocity to another inertial reference frame).

Four-vectors describe, for instance, position x in spacetime modeled as Minkowski space, a particle's four-momentum p, the amplitude of the electromagnetic four-potential A(x) at a point x in spacetime, and the elements of the subspace spanned by the gamma matrices inside the Dirac algebra.

The Lorentz group may be represented by 4×4 matrices Λ. The action of a Lorentz transformation on a general contravariant four-vector X (like the examples above), regarded as a column vector with Cartesian coordinates with respect to an inertial frame in the entries, is given by

(matrix multiplication) where the components of the primed object refer to the new frame. Related to the examples above that are given as contravariant vectors, there are also the corresponding covariant vectors xμ, pμ and Aμ(x). These transform according to the rule

where denotes the matrix transpose. This rule is different from the above rule. It corresponds to the dual representation of the standard representation. However, for the Lorentz group the dual of any representation is equivalent to the original representation. Thus the objects with covariant indices are four-vectors as well.

For an example of a well-behaved four-component object in special relativity that is not a four-vector, see bispinor. It is similarly defined, the difference being that the transformation rule under Lorentz transformations is given by a representation other than the standard representation. In this case, the rule reads X′ = Π(Λ)X, where Π(Λ) is a 4×4 matrix other than Λ. Similar remarks apply to objects with fewer or more components that are well-behaved under Lorentz transformations. These include scalars, spinors, tensors and spinor-tensors.

The article considers four-vectors in the context of special relativity. Although the concept of four-vectors also extends to general relativity, some of the results stated in this article require modification in general relativity.

Notation

The notations in this article are: lowercase bold for three-dimensional vectors, hats for three-dimensional unit vectors, capital bold for four dimensional vectors (except for the four-gradient), and tensor index notation.

Four-vector algebra

Four-vectors in a real-valued basis

A four-vector A is a vector with a "timelike" component and three "spacelike" components, and can be written in various equivalent notations:

where A is the magnitude component and Eα is the basis vector component; note that both are necessary to make a vector, and that when A is seen alone, it refers strictly to the components of the vector.

The upper indices indicate contravariant components. Here the standard convention is that Latin indices take values for spatial components, so that i = 1, 2, 3, and Greek indices take values for space and time components, so α = 0, 1, 2, 3, used with the summation convention. The split between the time component and the spatial components is a useful one to make when determining contractions of one four vector with other tensor quantities, such as for calculating Lorentz invariants in inner products (examples are given below), or raising and lowering indices.

In special relativity, the spacelike basis E1, E2, E3 and components A, A, A are often Cartesian basis and components:

although, of course, any other basis and components may be used, such as spherical polar coordinates

or cylindrical polar coordinates,

or any other orthogonal coordinates, or even general curvilinear coordinates. Note the coordinate labels are always subscripted as labels and are not indices taking numerical values. In general relativity, local curvilinear coordinates in a local basis must be used. Geometrically, a four-vector can still be interpreted as an arrow, but in spacetime - not just space. In relativity, the arrows are drawn as part of Minkowski diagram (also called spacetime diagram). In this article, four-vectors will be referred to simply as vectors.

It is also customary to represent the bases by column vectors:

so that:

The relation between the covariant and contravariant coordinates is through the Minkowski metric tensor (referred to as the metric), η which raises and lowers indices as follows:

and in various equivalent notations the covariant components are:

where the lowered index indicates it to be covariant. Often the metric is diagonal, as is the case for orthogonal coordinates (see line element), but not in general curvilinear coordinates.

The bases can be represented by row vectors:

so that:

The motivation for the above conventions are that the inner product is a scalar, see below for details.

Lorentz transformation

Main article: Lorentz transformationGiven two inertial or rotated frames of reference, a four-vector is defined as a quantity which transforms according to the Lorentz transformation matrix Λ:

In index notation, the contravariant and covariant components transform according to, respectively: in which the matrix Λ has components Λν in row μ and column ν, and the matrix (Λ) has components Λμ in row μ and column ν.

For background on the nature of this transformation definition, see tensor. All four-vectors transform in the same way, and this can be generalized to four-dimensional relativistic tensors; see special relativity.

Pure rotations about an arbitrary axis

For two frames rotated by a fixed angle θ about an axis defined by the unit vector:

without any boosts, the matrix Λ has components given by:

where δij is the Kronecker delta, and εijk is the three-dimensional Levi-Civita symbol. The spacelike components of four-vectors are rotated, while the timelike components remain unchanged.

For the case of rotations about the z-axis only, the spacelike part of the Lorentz matrix reduces to the rotation matrix about the z-axis:

Pure boosts in an arbitrary direction

For two frames moving at constant relative three-velocity v (not four-velocity, see below), it is convenient to denote and define the relative velocity in units of c by:

Then without rotations, the matrix Λ has components given by: where the Lorentz factor is defined by: and δij is the Kronecker delta. Contrary to the case for pure rotations, the spacelike and timelike components are mixed together under boosts.

For the case of a boost in the x-direction only, the matrix reduces to;

Where the rapidity ϕ expression has been used, written in terms of the hyperbolic functions:

This Lorentz matrix illustrates the boost to be a hyperbolic rotation in four dimensional spacetime, analogous to the circular rotation above in three-dimensional space.

Properties

Linearity

Four-vectors have the same linearity properties as Euclidean vectors in three dimensions. They can be added in the usual entrywise way: and similarly scalar multiplication by a scalar λ is defined entrywise by:

Then subtraction is the inverse operation of addition, defined entrywise by:

Minkowski tensor

See also: spacetime intervalApplying the Minkowski tensor ημν to two four-vectors A and B, writing the result in dot product notation, we have, using Einstein notation:

in special relativity. The dot product of the basis vectors is the Minkowski metric, as opposed to the Kronecker delta as in Euclidean space. It is convenient to rewrite the definition in matrix form: in which case ημν above is the entry in row μ and column ν of the Minkowski metric as a square matrix. The Minkowski metric is not a Euclidean metric, because it is indefinite (see metric signature). A number of other expressions can be used because the metric tensor can raise and lower the components of A or B. For contra/co-variant components of A and co/contra-variant components of B, we have: so in the matrix notation: while for A and B each in covariant components: with a similar matrix expression to the above.

Applying the Minkowski tensor to a four-vector A with itself we get: which, depending on the case, may be considered the square, or its negative, of the length of the vector.

Following are two common choices for the metric tensor in the standard basis (essentially Cartesian coordinates). If orthogonal coordinates are used, there would be scale factors along the diagonal part of the spacelike part of the metric, while for general curvilinear coordinates the entire spacelike part of the metric would have components dependent on the curvilinear basis used.

Standard basis, (+−−−) signature

The (+−−−) metric signature is sometimes called the "mostly minus" convention, or the "west coast" convention.

In the (+−−−) metric signature, evaluating the summation over indices gives: while in matrix form:

It is a recurring theme in special relativity to take the expression in one reference frame, where C is the value of the inner product in this frame, and: in another frame, in which C′ is the value of the inner product in this frame. Then since the inner product is an invariant, these must be equal: that is:

Considering that physical quantities in relativity are four-vectors, this equation has the appearance of a "conservation law", but there is no "conservation" involved. The primary significance of the Minkowski inner product is that for any two four-vectors, its value is invariant for all observers; a change of coordinates does not result in a change in value of the inner product. The components of the four-vectors change from one frame to another; A and A′ are connected by a Lorentz transformation, and similarly for B and B′, although the inner products are the same in all frames. Nevertheless, this type of expression is exploited in relativistic calculations on a par with conservation laws, since the magnitudes of components can be determined without explicitly performing any Lorentz transformations. A particular example is with energy and momentum in the energy-momentum relation derived from the four-momentum vector (see also below).

In this signature we have:

With the signature (+−−−), four-vectors may be classified as either spacelike if , timelike if , and null vectors if .

Standard basis, (−+++) signature

The (-+++) metric signature is sometimes called the "east coast" convention.

Some authors define η with the opposite sign, in which case we have the (−+++) metric signature. Evaluating the summation with this signature:

while the matrix form is:

Note that in this case, in one frame:

while in another:

so that:

which is equivalent to the above expression for C in terms of A and B. Either convention will work. With the Minkowski metric defined in the two ways above, the only difference between covariant and contravariant four-vector components are signs, therefore the signs depend on which sign convention is used.

We have:

With the signature (−+++), four-vectors may be classified as either spacelike if , timelike if , and null if .

Dual vectors

Applying the Minkowski tensor is often expressed as the effect of the dual vector of one vector on the other:

Here the Aνs are the components of the dual vector A* of A in the dual basis and called the covariant coordinates of A, while the original A components are called the contravariant coordinates.

Four-vector calculus

Derivatives and differentials

In special relativity (but not general relativity), the derivative of a four-vector with respect to a scalar λ (invariant) is itself a four-vector. It is also useful to take the differential of the four-vector, dA and divide it by the differential of the scalar, dλ:

where the contravariant components are:

while the covariant components are:

In relativistic mechanics, one often takes the differential of a four-vector and divides by the differential in proper time (see below).

Fundamental four-vectors

Four-position

A point in Minkowski space is a time and spatial position, called an "event", or sometimes the position four-vector or four-position or 4-position, described in some reference frame by a set of four coordinates:

where r is the three-dimensional space position vector. If r is a function of coordinate time t in the same frame, i.e. r = r(t), this corresponds to a sequence of events as t varies. The definition R = ct ensures that all the coordinates have the same dimension (of length) and units (in the SI, meters). These coordinates are the components of the position four-vector for the event.

The displacement four-vector is defined to be an "arrow" linking two events:

For the differential four-position on a world line we have, using a norm notation:

defining the differential line element ds and differential proper time increment dτ, but this "norm" is also:

so that:

When considering physical phenomena, differential equations arise naturally; however, when considering space and time derivatives of functions, it is unclear which reference frame these derivatives are taken with respect to. It is agreed that time derivatives are taken with respect to the proper time . As proper time is an invariant, this guarantees that the proper-time-derivative of any four-vector is itself a four-vector. It is then important to find a relation between this proper-time-derivative and another time derivative (using the coordinate time t of an inertial reference frame). This relation is provided by taking the above differential invariant spacetime interval, then dividing by (cdt) to obtain:

where u = dr/dt is the coordinate 3-velocity of an object measured in the same frame as the coordinates x, y, z, and coordinate time t, and

is the Lorentz factor. This provides a useful relation between the differentials in coordinate time and proper time:

This relation can also be found from the time transformation in the Lorentz transformations.

Important four-vectors in relativity theory can be defined by applying this differential .

Four-gradient

Considering that partial derivatives are linear operators, one can form a four-gradient from the partial time derivative ∂/∂t and the spatial gradient ∇. Using the standard basis, in index and abbreviated notations, the contravariant components are:

Note the basis vectors are placed in front of the components, to prevent confusion between taking the derivative of the basis vector, or simply indicating the partial derivative is a component of this four-vector. The covariant components are:

Since this is an operator, it doesn't have a "length", but evaluating the inner product of the operator with itself gives another operator:

called the D'Alembert operator.

Kinematics

Four-velocity

Main article: Four-velocityThe four-velocity of a particle is defined by:

Geometrically, U is a normalized vector tangent to the world line of the particle. Using the differential of the four-position, the magnitude of the four-velocity can be obtained:

in short, the magnitude of the four-velocity for any object is always a fixed constant:

The norm is also:

so that:

which reduces to the definition of the Lorentz factor.

Units of four-velocity are m/s in SI and 1 in the geometrized unit system. Four-velocity is a contravariant vector.

Four-acceleration

The four-acceleration is given by:

where a = du/dt is the coordinate 3-acceleration. Since the magnitude of U is a constant, the four acceleration is orthogonal to the four velocity, i.e. the Minkowski inner product of the four-acceleration and the four-velocity is zero:

which is true for all world lines. The geometric meaning of four-acceleration is the curvature vector of the world line in Minkowski space.

Dynamics

Four-momentum

For a massive particle of rest mass (or invariant mass) m0, the four-momentum is given by:

where the total energy of the moving particle is:

and the total relativistic momentum is:

Taking the inner product of the four-momentum with itself:

and also:

which leads to the energy–momentum relation:

This last relation is useful in relativistic mechanics, essential in relativistic quantum mechanics and relativistic quantum field theory, all with applications to particle physics.

Four-force

The four-force acting on a particle is defined analogously to the 3-force as the time derivative of 3-momentum in Newton's second law:

where P is the power transferred to move the particle, and f is the 3-force acting on the particle. For a particle of constant invariant mass m0, this is equivalent to

An invariant derived from the four-force is:

from the above result.

Thermodynamics

See also: Relativistic heat conductionFour-heat flux

The four-heat flux vector field, is essentially similar to the 3d heat flux vector field q, in the local frame of the fluid:

where T is absolute temperature and k is thermal conductivity.

Four-baryon number flux

The flux of baryons is: where n is the number density of baryons in the local rest frame of the baryon fluid (positive values for baryons, negative for antibaryons), and U the four-velocity field (of the fluid) as above.

Four-entropy

The four-entropy vector is defined by: where s is the entropy per baryon, and T the absolute temperature, in the local rest frame of the fluid.

Electromagnetism

Examples of four-vectors in electromagnetism include the following.

Four-current

The electromagnetic four-current (or more correctly a four-current density) is defined by formed from the current density j and charge density ρ.

Four-potential

The electromagnetic four-potential (or more correctly a four-EM vector potential) defined by formed from the vector potential a and the scalar potential ϕ.

The four-potential is not uniquely determined, because it depends on a choice of gauge.

In the wave equation for the electromagnetic field:

- In vacuum,

- With a four-current source and using the Lorenz gauge condition ,

Waves

Four-frequency

A photonic plane wave can be described by the four-frequency, defined as

where ν is the frequency of the wave and is a unit vector in the travel direction of the wave. Now:

so the four-frequency of a photon is always a null vector.

Four-wavevector

See also: De Broglie relationThe quantities reciprocal to time t and space r are the angular frequency ω and angular wave vector k, respectively. They form the components of the four-wavevector or wave four-vector:

The wave four-vector has coherent derived unit of reciprocal meters in the SI.

A wave packet of nearly monochromatic light can be described by:

The de Broglie relations then showed that four-wavevector applied to matter waves as well as to light waves: yielding and , where ħ is the Planck constant divided by 2π .

The square of the norm is: and by the de Broglie relation: we have the matter wave analogue of the energy–momentum relation:

Note that for massless particles, in which case m0 = 0, we have: or ‖k‖ = ω/c . Note this is consistent with the above case; for photons with a 3-wavevector of modulus ω / c , in the direction of wave propagation defined by the unit vector

Quantum theory

Four-probability current

In quantum mechanics, the four-probability current or probability four-current is analogous to the electromagnetic four-current: where ρ is the probability density function corresponding to the time component, and j is the probability current vector. In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, this current is always well defined because the expressions for density and current are positive definite and can admit a probability interpretation. In relativistic quantum mechanics and quantum field theory, it is not always possible to find a current, particularly when interactions are involved.

Replacing the energy by the energy operator and the momentum by the momentum operator in the four-momentum, one obtains the four-momentum operator, used in relativistic wave equations.

Four-spin

The four-spin of a particle is defined in the rest frame of a particle to be where s is the spin pseudovector. In quantum mechanics, not all three components of this vector are simultaneously measurable, only one component is. The timelike component is zero in the particle's rest frame, but not in any other frame. This component can be found from an appropriate Lorentz transformation.

The norm squared is the (negative of the) magnitude squared of the spin, and according to quantum mechanics we have

This value is observable and quantized, with s the spin quantum number (not the magnitude of the spin vector).

Other formulations

Four-vectors in the algebra of physical space

A four-vector A can also be defined in using the Pauli matrices as a basis, again in various equivalent notations: or explicitly: and in this formulation, the four-vector is represented as a Hermitian matrix (the matrix transpose and complex conjugate of the matrix leaves it unchanged), rather than a real-valued column or row vector. The determinant of the matrix is the modulus of the four-vector, so the determinant is an invariant:

This idea of using the Pauli matrices as basis vectors is employed in the algebra of physical space, an example of a Clifford algebra.

Four-vectors in spacetime algebra

In spacetime algebra, another example of Clifford algebra, the gamma matrices can also form a basis. (They are also called the Dirac matrices, owing to their appearance in the Dirac equation). There is more than one way to express the gamma matrices, detailed in that main article.

The Feynman slash notation is a shorthand for a four-vector A contracted with the gamma matrices:

The four-momentum contracted with the gamma matrices is an important case in relativistic quantum mechanics and relativistic quantum field theory. In the Dirac equation and other relativistic wave equations, terms of the form: appear, in which the energy E and momentum components (px, py, pz) are replaced by their respective operators.

See also

- Basic introduction to the mathematics of curved spacetime

- Dust (relativity) for the number-flux four-vector

- Minkowski space

- Paravector

- Relativistic mechanics

- Wave vector

References

- Rindler, W. Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd edn.) (1991) Clarendon Press Oxford ISBN 0-19-853952-5

- Sibel Baskal; Young S Kim; Marilyn E Noz (1 November 2015). Physics of the Lorentz Group. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 978-1-68174-062-1.

- Relativity DeMystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (BSA), 2006, ISBN 0-07-145545-0

- C.B. Parker (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 1333. ISBN 0-07-051400-3.

- Gravitation, J.B. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne, W.H. Freeman & Co, 1973, ISAN 0-7167-0344-0

- Dynamics and Relativity, J.R. Forshaw, B.G. Smith, Wiley, 2009, ISAN 978-0-470-01460-8

- Relativity DeMystified, D. McMahon, Mc Graw Hill (ASB), 2006, ISAN 0-07-145545-0

- "Details for IEV number 113-07-19: "position four-vector"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-09-08.

- Jean-Bernard Zuber & Claude Itzykson, Quantum Field Theory, pg 5, ISBN 0-07-032071-3

- Charles W. Misner, Kip S. Thorne & John A. Wheeler,Gravitation, pg 51, ISBN 0-7167-0344-0

- George Sterman, An Introduction to Quantum Field Theory, pg 4, ISBN 0-521-31132-2

- Ali, Y. M.; Zhang, L. C. (2005). "Relativistic heat conduction". Int. J. Heat Mass Trans. 48 (12): 2397–2406. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2005.02.003.

- J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. pp. 558–559. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. p. 567. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. p. 558. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Rindler, Wolfgang (1991). Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd ed.). Oxford Science Publications. pp. 103–107. ISBN 0-19-853952-5.

- "Details for IEV number 113-07-57: "four-wave vector"". International Electrotechnical Vocabulary (in Japanese). Retrieved 2024-09-08.

- Vladimir G. Ivancevic, Tijana T. Ivancevic (2008) Quantum leap: from Dirac and Feynman, across the universe, to human body and mind. World Scientific Publishing Company, ISBN 978-981-281-927-7, p. 41

- J.A. Wheeler; C. Misner; K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. pp. 1142–1143. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- Rindler, W. Introduction to Special Relativity (2nd edn.) (1991) Clarendon Press Oxford ISBN 0-19-853952-5

so that:

so that:

in which the matrix Λ has components Λν in row μ and column ν, and the matrix (Λ) has components Λμ in row μ and column ν.

in which the matrix Λ has components Λν in row μ and column ν, and the matrix (Λ) has components Λμ in row μ and column ν.

where the

where the  and δij is the

and δij is the

and similarly

and similarly

in which case ημν above is the entry in row μ and column ν of the Minkowski metric as a square matrix. The Minkowski metric is not a

in which case ημν above is the entry in row μ and column ν of the Minkowski metric as a square matrix. The Minkowski metric is not a  so in the matrix notation:

so in the matrix notation:

while for A and B each in covariant components:

while for A and B each in covariant components:

with a similar matrix expression to the above.

with a similar matrix expression to the above.

which, depending on the case, may be considered the square, or its negative, of the length of the vector.

which, depending on the case, may be considered the square, or its negative, of the length of the vector.

while in matrix form:

while in matrix form:

in one

in one  in another frame, in which C′ is the value of the inner product in this frame. Then since the inner product is an invariant, these must be equal:

in another frame, in which C′ is the value of the inner product in this frame. Then since the inner product is an invariant, these must be equal:

that is:

that is:

,

,  , and

, and  .

.

. As proper time is an invariant, this guarantees that the proper-time-derivative of any four-vector is itself a four-vector. It is then important to find a relation between this proper-time-derivative and another time derivative (using the

. As proper time is an invariant, this guarantees that the proper-time-derivative of any four-vector is itself a four-vector. It is then important to find a relation between this proper-time-derivative and another time derivative (using the

.

.

where n is the

where n is the  where s is the entropy per baryon, and T the

where s is the entropy per baryon, and T the  formed from the

formed from the  formed from the

formed from the

,

,

is a

is a

yielding

yielding  and

and  , where ħ is the

, where ħ is the  and by the de Broglie relation:

and by the de Broglie relation:

we have the matter wave analogue of the energy–momentum relation:

we have the matter wave analogue of the energy–momentum relation:

or ‖k‖ = ω/c . Note this is consistent with the above case; for photons with a 3-wavevector of modulus ω / c , in the direction of wave propagation defined by the unit vector

or ‖k‖ = ω/c . Note this is consistent with the above case; for photons with a 3-wavevector of modulus ω / c , in the direction of wave propagation defined by the unit vector

where ρ is the

where ρ is the  where s is the

where s is the

or explicitly:

or explicitly:

and in this formulation, the four-vector is represented as a

and in this formulation, the four-vector is represented as a

appear, in which the energy E and momentum components (px, py, pz) are replaced by their respective

appear, in which the energy E and momentum components (px, py, pz) are replaced by their respective