| Revision as of 22:05, 19 July 2011 editJames Cantor (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers6,721 edits @Bonze blayk: I repeat: That family of edits contains BLP violations (including of me personally), and WP takes BLP violations very seriously. I suggest also you read BOLD-REVERT-← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:45, 2 December 2024 edit undoHuzaroanzi (talk | contribs)16 edits →See also: LGBTQ symbols | ||

| (296 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Sexual orientation to men or women}} | |||

| {{Multiple issues}} | |||

| {{Sexual orientation}} | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=March 2009}} | |||

| {{Transgender sidebar}} | |||

| {{mergefrom|Philogyny|discuss=Talk:Androphilia and gynephilia#Philogyny|date=August 2010}} | |||

| In ], '''androphilia and gynephilia''' are ]s: Androphilia is sexual attraction to ] and/or ]; gynephilia is sexual attraction to ] and/or ].<ref name="schmidt2010" /> '''Ambiphilia''' describes the combination of both androphilia and gynephilia in a given individual, or ]. The terms offer an alternative to a ] ] and ] conceptualization of sexuality. <ref name="diamond2010">Diamond M (2010). Sexual orientation and gender identity. In Weiner IB, Craighead EW eds. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, Volume 4. p. 1578. John Wiley and Sons, {{ISBN|978-0-470-17023-6}}</ref> | |||

| The terms are used for identifying a person's objects of attraction without attributing a ] or ] to the person. They may be used when describing ], ], and ] people.<ref>Turban J, de Vries ALC, Zucker KJ, & Shadianloo S (2018). . The International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions, p. 3. Accessed 31 August 2022.</ref> | |||

| '''Androphilia''' is ] to men, and its counterpart '''gynephilia'''<ref>http://lgbthealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/Needs%20Assessment%20Sept%2007%20_Updated%20Dec%2007_.PDF</ref><ref>http://starways.net/beth/4not2.html</ref> is attraction to women. | |||

| ==Historical use== | |||

| The term ''androsexuality''<ref>http://www.black-rose.com/articles-liz/genderlang.html</ref> was originally used to describe the age aspect of ] of male homosexuals. The terms ''androphilia'' and ''gynephilia'' were also used to distinguish love of adult humans from ] and ]. These describe types of chronosexuality and within that, androsexuality and gynesexuality collectively refer to two variable forms of teleiosexuality. | |||

| ===Androphilia=== | |||

| Later the words ''androphilia'' and ''gynephilia'' (''gynaekophilia'') were appropriated to describe sexual ] independently of one's sex, particularly in discussing the orientation of transsexual people (regardless of which age-range of attraction), as well as for general studies of sexual attraction. | |||

| ], an early-20th century German sexologist and physician, divided homosexual men into four groups: ], who are most attracted to prepubescent youth, ], who are most attracted to youths from puberty up to the early twenties; androphiles, who are most attracted to persons between the early twenties and fifty; and ], who are most attracted to older men, up to senile old age.<ref>Hirschfeld M (1948). Sexual anomalies: the origins, nature and treatment of sexual disorders : a summary of the works of Magnus Hirschfeld. Emerson Books, {{OCLC|1041032404}}</ref><ref>Dynes W.R. & Donaldson S (1990). Encyclopedia of homosexuality, Volume 1. Garland Publishing, {{ISBN|978-0-8240-6544-7}}</ref> According to ], Hirschfeld considered ephebophilia "common and nonpathological, with ephebophiles and androphiles each making up about 45% of the homosexual population."<ref>Franklin K (2010). Hebephilia: quintessence of diagnostic pretextuality. '']'', volume 28, issue 6, pp. 751–768, {{doi|10.1002/bsl.934}}, {{PMID|21110392}}</ref> | |||

| The term ''androsexuality'' is occasionally used as a synonym for ''androphilia''.<ref name="Tucker">Tucker N (1995). Bisexual politics: theories, queries, and visions. Psychology Press, {{ISBN|978-1-56024-950-4}}</ref> | |||

| == Androphilia == | |||

| ;Alternate uses in biology and medicine | |||

| It is believed that the term originated from ] systematics of homosexual men.{{Fact|date=April 2009}} ], writing in the early twentieth century, offered a threefold age classification system for homosexual men: {{Fact|date=February 2007}} | |||

| In ], ''androphilic'' is sometimes used as a synonym for '']'', describing ]s who have a host preference for humans versus non-human animals.<ref name="covel">Covell G, Russell PF, Hendrik N (1953). Malaria terminology: Report of a drafting committee appointed by the World Health Organization. ], {{ISBN|9241400137}}</ref> | |||

| *], "who are attracted to youths from puberty to the early 20s". The term is now used to describe both heterosexual and homosexual attraction to the age range. | |||

| *'''Androphiles''', which he used as men who prefer men from their second to fifth decade. The term is now mostly used correctly; to describe any who have love for men. | |||

| *], who prefer older men. The term is now used correctly; as a sexually neutral preference for old people. | |||

| ''Androphilic'' is also sometimes used to describe certain ]s and ]s.<ref name="calandra">Calandra RS, Podestá EJ, Rivarola MA, Blaquier JA (1974). Tissue androgens and androphilic proteins in rat epididymis during sexual development '']'', volume 24, issue 4, pp. 507-518 {{doi|10.1016/0039-128X(74)90132-9}}</ref> | |||

| The term androphilia was used in describing societies where ] was the norm, but where attraction between adult men was frowned upon.{{Fact|date=April 2009}} | |||

| ===Gynephilia=== | |||

| A book by ] uses the term androphilia in its title: ''Androphilia, A Manifesto: Rejecting the Gay Identity, Reclaiming Masculinity'' (ISBN 0-9764035-8-7). The author uses the term to emphasize ] in both the object and the subject of male homosexual desire and to reject the sexual nonconformity that he sees in some segments of the homosexual identity. | |||

| A version of the term appeared in ]. In '']'' 8, line 60, ] uses {{lang|grc-Latn|gynaikophilias}} ({{lang|grc|γυναικοφίλιας}}) as a euphemistic adjective to describe ]'s lust for women.<ref name="cholmeley">Cholmeley RJ (1901). The idylls of Theocritus. G. Bell & Sons, p. 98</ref><ref name="rummel">Rummel, E (1996). Erasmud on Women. University of Toronto Press, p. 82, {{ISBN|978-0-8020-7808-7}}</ref><ref name="brown1979">Brown GW (1979). Depression: A sociologist's view. ''Trends in Neurosciences'', Volume 2, pp. 253–256 {{doi|10.1016/0166-2236(79)90099-7}}</ref> | |||

| ] used the term ''gynecophilic'' to describe his ] ].<ref name="kahane">Kahane C (2004). Freud and the passions of the voice. In O'Neill J (2004). ''Freud and the Passions.'' Penn State Press, {{ISBN|978-0-271-02564-3}}</ref> He also used the term in correspondence.<ref name="freud19080325">Freud, S (1908). , March 25 1908. Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing. Accessed 31 August 2022. Quote: "I have often seen it so: a woman unsatisfied by a man naturally turns to a woman and tries to invest her long-suppressed gynecophilic component with libido."</ref> | |||

| == Gynephilia == | |||

| The variant spelling ''gynophilia'' is also sometimes used.<ref name="Money1986">] (1986). Venuses Penuses: Sexology, Sexosophy, and Exigency Theory. Prometheus Books, {{ISBN|978-0-87975-327-6}}</ref> | |||

| ''Gynephilia'' is philologically inconsequent, as it takes the nominative form in place of the root, and would have as its counterpart ''anerphilia'' (From Greek ''anēr'', "men," + ''-philia''), not ''androphilia'' ; while ''gynophilia'' is formed in violation of Greek word formation rules,{{Fact|date=April 2009}} cf. gynaecology/gynecology (From Greek ''gynaiko-'', "woman," + ''logos'') | |||

| Rarely, the term ''gynesexuality'' has also been used as a synonym.<ref name="Chodorow">Chodorow N (1999). The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. University of California Press, {{ISBN|978-0-520-22155-0}}</ref> | |||

| The term ''gynophilia'' is misused in some ] to mean "attraction to adult women", in contrast with ], with the aim of therapy usually being to replace pedophilic desires with teleiosexual ones.{{Fact|date=March 2008}} | |||

| ==Sexual interest in adults== | |||

| The age zone of gynephilic interests is defined likewise as in case of androphilia. | |||

| Following Hirschfeld, ''androphilia'' and ''gynephilia'' are sometimes used in taxonomies which specify sexual interests based on age ranges, which ] called ]. In such schemes, sexual attraction to adults is called teleiophilia<ref>Blanchard R, Barbaree HE, Bogaert AF, Dickey R, Klassen P, Kuban ME, & Zucker KJ (2000). Fraternal birth order and sexual orientation in paedophiles. ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', volume 29, issue 5, pp. 463–478, {{doi|10.1023/A:1001943719964}}, {{PMID|10983250}}, {{s2cid|19755751}}</ref> or adultophilia.<ref name="feierman">Feierman JR (1992). Reply to Dickemann: The ethology of variant sexology. ''Human Nature'', volume 3, number 3, pp. 279–297, {{doi|10.1007/BF02692242}}, {{PMID|24222432}}</ref> In this context, ''androphilia'' and ''gynephilia'' are gendered variants meaning "attraction to adult males" and "attraction to adult females", respectively. Psychologist ] writes: | |||

| <blockquote>Definition is primarily an issue of theory, not merely classification, since classification implies a theory, no matter how rudimentary. ] ''et al.'' (1984) used Latinesque words to classify sexual attraction along the dimensions of sex and age:<br/> | |||

| Gynephilia. Sexual interest in physically adult women<br/> | |||

| Androphilia. Sexual interest in physically adult males<ref name="howitt1995">Howitt D (1995). Introducing the paedophile. In ''Paedophiles and sexual offences against children''. J. Wiley,{{isbn|9780471939399}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ==Androphilia and gynephilia scales== | |||

| == Use for transsexual people == | |||

| The nine-item Gynephilia Scale was created to measure erotic interest in physically mature females, and the thirteen-item Androphilia Scale was created to measure erotic interest in physically mature males. The scales were developed by ] and ] in 1982.<ref name="freund1982">Freund K, Steiner BW, & Chan S (1982). Two types of cross-gender identity. '']'', volume 11, issue 1, pp. 49–64, {{doi|10.1007/bf01541365}}, {{PMID|7073469}}, {{s2cid|42131695}}</ref> They were later modified by ] in 1985, as the Modified Androphilia–Gynephilia Index (MAGI).<ref>Blanchard, R. (1985). Research Methods for the Typological Study of Gender Disorders in Males. In: Steiner, B.W. (eds) Gender Dysphoria. Perspectives in Sexuality. Springer, Boston, MA. {{doi|10.1007/978-1-4684-4784-2_8}}, {{s2cid|140817009}}</ref> | |||

| The terms gynephilia and androphilia are occasionally used when referring to the ] of transsexual people,<ref>For example: "] are a heterogeneous group of androphilic men, some of whom are unremarkably masculine, but most of whom behave in a feminine manner in adulthood.", Bartlett, Nancy H. and Vasey, Paul L. (2006), ''A Retrospective Study of Childhood Gender-Atypical Behavior in Samoan Fa’afafine'', Archives of Sexual Behavior, Springer Netherlands, ISSN 0004-0002 (Print) 1573-2800 (Online), Volume 35, Number 6, December 2006, Pages 659-666</ref> since the terms ] and ] can be unclear. In describing a human's ] as homosexual or heterosexual, one is not only saying a thing about the ] that human desires, but also about their own sex — specifically, that their sex is the same as, or different from, that of those they desire. Difficulty in making these judgements can be seen, for example, in debates about whether gynephilic transsexual men are homosexual. Androphilia and gynephilia are often preferred, because rather than focusing on the sex of the subject, they only describe that of the object of their attraction. This has led to less emphasis on the age-based restriction that those terms were originally misused for. The third common term that describes sexual orientation, ], makes no claim about the subject's sexual identity. | |||

| ==Gender identity and expression== | |||

| This use is problematic for transsexual people because it denies their experiences as their actual sex, but also implies that they are really of the sex they were originally. It is barely controversial that transsexual people define themselves as homosexual, heterosexual, and bisexual as appropriate, and will reject any terminology that is applied to them but not also to ] people. Debates about whether gynesexual transsexual men are homosexual, for example, do not typically include those men's perspectives. | |||

| {{Update|section|date=July 2023}} | |||

| ] | |||

| It is however more commonly and less controversially used amongst ] people who fall outside the ] and so are usually considered ] if not always transsexual. For them conventional terms like ] and ] don't apply so easily and so describing the gender you're attracted to independent of your own is often useful especially when talking about ] sexualities. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] distinguished between gynephilic, bisexual, androphilic, asexual, and narcissistic or automonosexual gender-variant persons.<ref>Veale JF, Clarke DE, & Lomax TC (2008). Sexuality of male-to-female transsexuals. '']'', volume 37, issue 4, pp. 586-597, {{doi|10.1007/s10508-007-9306-9}}, {{PMID|18299976}}</ref><ref>Freund K, Heasman G, Racansky IG, & Glancy G (1984). Pedophilia and heterosexuality vs. homosexuality. ''Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy'', volume 10, issue 3, pp. 193-200, {{doi|10.1080/00926238408405945}}</ref> Since then,{{When|date=July 2023}} some psychologists have proposed using ''homosexual transsexual'' and ''heterosexual transsexual'' or ''non-homosexual transsexual.'' Psychobiologist ] has described this split among psychologists: "The mf transsexuals who are attracted to men (whom some call 'homosexual' and others call 'androphilic') are in the lower left-hand corner of the XY table, in order to line them up with the ordinary homosexual (androphilic) men in the lower right. Finally, there are the mf transsexuals who are attracted to women (whom some call heterosexual and others call gynephilic or lesbian)."<ref name="weinrich">Weinrich JD (1987). Sexual landscapes: why we are what we are, why we love whom we love. Scribner's, {{ISBN|978-0-684-18705-1}}</ref>{{Obsolete source|date=July 2023}} | |||

| The use of ''homosexual transsexual'' and related terms have been applied to ] people since the middle of the 20th century,{{Citation needed|date=July 2023}} though concerns about the terms have been voiced since then. ] said in 1966: | |||

| <blockquote>....it seems evident that the question "Is the transsexual homosexual?" must be answered "yes" and "no." "Yes," if his anatomy is considered; "no" if his psyche is given preference. | |||

| What would be the situation after corrective surgery has been performed and the sex anatomy now resembles that of a woman? Is the "new woman" still a homosexual man? "Yes," if pedantry and technicalities prevail. "No" if reason and common sense are applied and if the respective patient is treated as an individual and not as a rubber stamp.<ref name="benjamin1966">Benjamin H (1966). . The Julian Press, Inc., {{isbn|9780446824262}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Many sources, including some supporters of the typology, criticize this choice of wording as confusing and degrading.{{Confusing|date=April 2023|reason=What choice of wording?}} Biologist ] writes "...the point of reference for "heterosexual" or "homosexual" orientation in this nomenclature is solely the individual's genetic sex prior to reassignment (see for example, Blanchard et al. 1987, Coleman and Bockting, 1988, Blanchard, 1989).<ref>Blanchard R (1988). Nonhomosexual gender dysphoria. ''Journal of Sex Research'', volume 24, pp. 188-193, {{doi|10.1080/00224498809551410}}</ref><ref>Coleman E & Bockting WO (1988). "Heterosexual" prior to sex reassignment—"homosexual" afterwards: A case study of a female-to-male transsexual. ''Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality'', volume 1, issue 2, pp. 69–82, {{doi|10.1300/J056v01n01_11}}</ref><ref>Blanchard R (1989). . ''Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease'', volume 177, issue 10, pp. 616–623, {{doi|10.1097/00005053-198910000-00004}}</ref> These labels thereby ignore the individual's personal sense of gender identity taking precedence over biological sex, rather than the other way around."<ref name="bagemihl">Bagemihl B (1997). Surrogate phonology and transsexual faggotry: A linguistic analogy for uncoupling sexual orientation from gender identity. In ''Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality''. Livia A & Hall K (eds). Oxford University Press, p. 380 ff, {{isbn|0-19-510471-4}}</ref> Bagemihl goes on to take issue with the way this terminology makes it easy to claim transsexuals are really homosexual males seeking to escape from stigma.<ref name="bagemihl" /> Leavitt and Berger stated in 1990 that "The homosexual transsexual label is both confusing and controversial among males seeking sex reassignment.<ref name="leavitt1990">Leavitt F & Berger JC (1990). '']'', volume 19, issue 5, pp. 491–505, {{doi|10.1007/BF02442350}}, {{PMID|2260914}}</ref><ref name="morgan1978">Morgan Jr AJ (1978). . '']'', volume 7, pp. 273–282, {{doi|10.1007/BF01542035}}, {{PMID|697564}}</ref> Critics argue that the term "homosexual transsexual" is "]",<ref name="bagemihl" /> "archaic",<ref name="wahng">Wahng SJ (2004). Double Cross: Transamasculinity Asian American Gendering. In ''Trappings of Transhood''. In Aldama AJ (ed.) ''Violence and the Body: Race, Gender, and the State''. Indiana University Press, {{ISBN|0-253-34171-X}}</ref> and demeaning because it labels people by sex assigned at birth instead of their ].<ref name="leiblum2000">Leiblum SR & Rosen RC (2000). Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy, third edition. Guilford Press of New York, p. c2000, {{ISBN|1-57230-574-6}}</ref> Benjamin, Leavitt, and Berger have all used the term in their own work.<ref name="benjamin1966" /><ref name="leavitt1990" /> Sexologist ] also recently expressed regret for having used this terminology, which was standard when he used it, to refer to transsexual women.<ref name="Bancroftcomment" /> He says that he now tries to choose his words more sensitively.<ref name="Bancroftcomment">Bancroft J (2008). Lust or Identity? ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', volume 37, issue 3, pp. 426–428, {{doi|10.1007/s10508-008-9317-1}}, {{PMID|18431640}}, {{s2cid|33178427}}</ref> Sexologist ] is likewise critical of the terminology.<ref name="moser2010">Moser C (2010). Blanchard's Autogynephilia Theory: A Critique. ''Journal of Homosexuality'', volume 57, edition 6, issue 6, pp. 790–809, {{doi|10.1080/00918369.2010.486241}}, {{PMID|20582803}}, {{s2cid|8765340}}</ref> | |||

| Use of ''androphilia'' and ''gynephilia'' was proposed and popularized by psychologist ] in the 1980s.<ref name="langevin1983">Langevin R (1982). Sexual Strands: Understanding and Treating Sexual Anomalies in Men. Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0-89859-205-4}}</ref> Psychologist ] writes, "Langevin makes several concrete suggestions regarding the language used to describe ]. For example, he proposes the terms ''gynephilic'' and ''androphilic'' to indicate the type of partner preferred regardless of an individual's ] or dress. Those who are writing and researching in this area would do well to adopt his clear and concise vocabulary."<ref name="wegener">Wegener ST (1984). Male sexual anomalies: the data (review of ''Sexual Strands'') ''APA Review of Books'', volume 29, issues 7–12, p. 783, | |||

| Volume 29, Issues 7–12, p. 783.</ref> | |||

| Psychiatrist ] explains why the terms are useful in a glossary: <blockquote>Androphilia – The romantic and/or sexual attraction to adult males. The term, along with gynephilia, is needed to overcome immense difficulties in characterizing the sexual orientation of transmen and transwomen. For instance, it is difficult to decide whether a transman erotically attracted to males is a heterosexual female or a homosexual male; or a transwoman erotically attracted to females is a heterosexual male or a lesbian female. Any attempt to classify them may not only cause confusion but arouse offense among the affected subjects. In such cases, while defining sexual attraction, it is best to focus on the object of their attraction rather than on the sex or gender of the subject.<ref name="Aggrawal2008">Aggrawal A (2008). Forensic and medico-legal aspects of sexual crimes and unusual sexual practices. CRC Press, {{ISBN|978-1-4200-4308-2}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Sexologist ], who prefers the term ''gynecophilia'', writes, "The terms heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual are better used as adjectives, not nouns, and are better applied to behaviors, not people." Diamond has encouraged using the terms androphilic, gynecophilic, and ambiphilic to describe the sexual-erotic partners one prefers (andro = male, gyneco = female, ambi = both, philic = to love). Such terms eliminate the need to specify the subject and focus instead on the desired partner. This usage is particularly advantageous when discussing the partners of transsexual or intersexed individuals. These newer terms also do not carry the social weight of the former ones."<ref name=diamond2010/> | |||

| Psychologist Rachel Ann Heath writes, "The terms homosexual and heterosexual are awkward, especially when the former is used with, or instead of, gay and lesbian. Alternatively, I use gynephilic and androphilic to refer to sexual preference for women and men, respectively. Gynephilic and androphilic derive from the Greek meaning love of a woman and love of a man respectively. So a gynephilic man is a man who likes women, that is, a heterosexual man, whereas an androphilic man is a man who likes men, that is, a gay man. For completeness, a lesbian is a gynephilic woman, a woman who likes other women. Gynephilic transsexed woman refers to a woman of transsexual background whose sexual preference is for women. Unless homosexual and heterosexual are more readily understood terms in a given context, this more precise terminology will be used throughout the book. Since homosexual, gay, and lesbian are often associated with bigotry and exclusion in many societies, the emphasis on sexual affiliation is both appropriate and socially just."<ref name="heath2006">Heath RA (2006). The Praeger handbook of transsexuality: Changing gender to match mindset. Greenwood Publishing Group, {{ISBN|978-0-275-99176-0}}</ref> Author ] agrees, writing, "It would be much more accurate to define sexual orientation as either 'androphilic' (loving men) and 'gynephilic' (loving women) instead."<ref name="boyd2007">Boyd H (2007). She's not the man I married: My life with a transgender husband. Seal Press, p. 102, {{ISBN|978-1-58005-193-4}}</ref> Sociomedical scientist ] challenges researchers like ], ], and ], who she says "have completely failed to appreciate the implications of alternative ways of framing sexual orientation."<ref name="jordan-young">Jordan-Young RM (2010). Brain storm: the flaws in the science of sex differences. Harvard University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-674-05730-2}}</ref> | |||

| ===Gender in non-Western cultures=== | |||

| Some researchers advocate use of the terminology to avoid ] inherent in Western conceptualizations of human sexuality. Writing about the ]n ] demographic, sociologist Johanna Schmidt writes: | |||

| <blockquote>Kris Poasa, ] and ] (2004) also present an argument that suggests that fa'afafine fall under the rubric of 'transgenderal homosexuality', applying the same birth order equation to fa'afafine's families as have been used with 'homosexual transsexuals'. While no explicit causal relationship is offered, Poasa, Blanchard, and Zucker's use of the term 'homosexual transsexual' to refer to male-to-female transsexuals who are sexually oriented towards men draws an apparent link between sexual orientation and gender identity. This link is reinforced by mention of the fact that similar birth order equations have been found for 'homosexual men'. The possibility of sexual orientation towards (masculine) men emerging from (rather than causing) feminine gendered identities is not considered.<ref name="schmidt2010">Schmidt J (2010). Migrating Genders: Westernisation, Migration, and Samoan Fa'afafine. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., p. 45, {{ISBN|978-1-4094-0273-2}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| Schmidt argues that in cultures where a ] is recognized, a term like "homosexual transsexual" does not align with cultural categories.<ref name="schmidt2001">Schmidt J (2001). ''Intersections: Gender, history and culture in the Asian context'', issue 6.</ref> | |||

| She cites the work of Paul Vasey and Nancy Bartlett: "Vasey and Bartlett reveal the cultural specificity of concepts such as homosexuality, they continue to use the more 'scientific' (and thus presumably more 'objective') terminology of androphilia and gynephilia (sexual attraction to men or masculinity and women or femininity respectively) to understand the sexuality of fa'afafine and other Samoans."<ref name="schmidt2010" /> Researcher Sam Winter has presented a similar argument: | |||

| <blockquote>Terms such as 'homosexual' and heterosexual (and 'gay', 'lesbian', 'bisexual', etc.) are Western conceptions. Many Asians are unfamiliar with them, there being no easy translation into their native languages or sexological worldviews. However, I take the opportunity to put on record that I consider an androphilic transwoman (ie one sexually attracted to men) to be heterosexual because of her attraction to a member of another gender and a gynephilic transwoman (ie one attracted to women) as homosexual because she has a same-gender preference. My usage is contrary to much Western literature (particularly medical) which persists in referring to androphilic transwomen and gynephilic transman as homosexual (indeed as homosexual transsexual males and females, respectively).<ref name="winter">Winter S (2010). Lost in Transition: Transpeople, Transprejudice and Pathology in Asia. In Chan PCW (ed.) ''The Protection of Sexual Minorities Since Stonewall: Progress and Stalemate in Developed and Developing Countries.'' Routledge, {{ISBN|978-0-415-41850-8}}</ref></blockquote> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{portal|Human sexuality|LGBTQ}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == |

==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist|30em}} | ||

| == |

===Bibliography=== | ||

| * Hames RB, Garfield ZH, & Garfield MJ (2017). ''Archives of Sexual Behavior'', volume 46, p. 132, {{doi|10.1007/s10508-016-0855-7}} | |||

| *Dynes, Wayne "Androphilia." Dynes, Wayne R. (ed.), Garland Publishing, 1990; p. 58. | |||

| {{Sexual identities}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Androphilia And Gynephilia}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Androphilia And Gynephilia}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:45, 2 December 2024

Sexual orientation to men or women| Sexual orientation |

|---|

|

| Sexual orientations |

| Related terms |

| Research |

| Animals |

| Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| Transgender topics |

|---|

| Gender identities |

|

Health care practices

|

|

Rights and legal status

|

|

Society and culture

Events and awareness

Culture |

Theory and concepts

|

By country

Rights

History |

| See also |

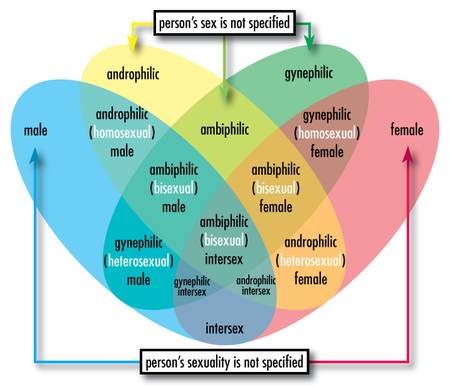

In behavioral science, androphilia and gynephilia are sexual orientations: Androphilia is sexual attraction to men and/or masculinity; gynephilia is sexual attraction to women and/or femininity. Ambiphilia describes the combination of both androphilia and gynephilia in a given individual, or bisexuality. The terms offer an alternative to a gender binary homosexual and heterosexual conceptualization of sexuality.

The terms are used for identifying a person's objects of attraction without attributing a sex assignment or gender identity to the person. They may be used when describing intersex, transgender, and non-binary people.

Historical use

Androphilia

Magnus Hirschfeld, an early-20th century German sexologist and physician, divided homosexual men into four groups: paedophiles, who are most attracted to prepubescent youth, ephebophiles, who are most attracted to youths from puberty up to the early twenties; androphiles, who are most attracted to persons between the early twenties and fifty; and gerontophiles, who are most attracted to older men, up to senile old age. According to Karen Franklin, Hirschfeld considered ephebophilia "common and nonpathological, with ephebophiles and androphiles each making up about 45% of the homosexual population."

The term androsexuality is occasionally used as a synonym for androphilia.

- Alternate uses in biology and medicine

In biology, androphilic is sometimes used as a synonym for anthropophilic, describing parasites who have a host preference for humans versus non-human animals.

Androphilic is also sometimes used to describe certain proteins and androgen receptors.

Gynephilia

A version of the term appeared in Ancient Greek. In Idyll 8, line 60, Theocritus uses gynaikophilias (γυναικοφίλιας) as a euphemistic adjective to describe Zeus's lust for women.

Sigmund Freud used the term gynecophilic to describe his case study Dora. He also used the term in correspondence.

The variant spelling gynophilia is also sometimes used.

Rarely, the term gynesexuality has also been used as a synonym.

Sexual interest in adults

Following Hirschfeld, androphilia and gynephilia are sometimes used in taxonomies which specify sexual interests based on age ranges, which John Money called chronophilia. In such schemes, sexual attraction to adults is called teleiophilia or adultophilia. In this context, androphilia and gynephilia are gendered variants meaning "attraction to adult males" and "attraction to adult females", respectively. Psychologist Dennis Howitt writes:

Definition is primarily an issue of theory, not merely classification, since classification implies a theory, no matter how rudimentary. Freund et al. (1984) used Latinesque words to classify sexual attraction along the dimensions of sex and age:

Gynephilia. Sexual interest in physically adult women

Androphilia. Sexual interest in physically adult males

Androphilia and gynephilia scales

The nine-item Gynephilia Scale was created to measure erotic interest in physically mature females, and the thirteen-item Androphilia Scale was created to measure erotic interest in physically mature males. The scales were developed by Kurt Freund and Betty Steiner in 1982. They were later modified by Ray Blanchard in 1985, as the Modified Androphilia–Gynephilia Index (MAGI).

Gender identity and expression

| This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (July 2023) |

Magnus Hirschfeld distinguished between gynephilic, bisexual, androphilic, asexual, and narcissistic or automonosexual gender-variant persons. Since then, some psychologists have proposed using homosexual transsexual and heterosexual transsexual or non-homosexual transsexual. Psychobiologist James D. Weinrich has described this split among psychologists: "The mf transsexuals who are attracted to men (whom some call 'homosexual' and others call 'androphilic') are in the lower left-hand corner of the XY table, in order to line them up with the ordinary homosexual (androphilic) men in the lower right. Finally, there are the mf transsexuals who are attracted to women (whom some call heterosexual and others call gynephilic or lesbian)."

The use of homosexual transsexual and related terms have been applied to transgender people since the middle of the 20th century, though concerns about the terms have been voiced since then. Harry Benjamin said in 1966:

....it seems evident that the question "Is the transsexual homosexual?" must be answered "yes" and "no." "Yes," if his anatomy is considered; "no" if his psyche is given preference. What would be the situation after corrective surgery has been performed and the sex anatomy now resembles that of a woman? Is the "new woman" still a homosexual man? "Yes," if pedantry and technicalities prevail. "No" if reason and common sense are applied and if the respective patient is treated as an individual and not as a rubber stamp.

Many sources, including some supporters of the typology, criticize this choice of wording as confusing and degrading.

| This article may be confusing or unclear to readers. In particular, What choice of wording?. Please help clarify the article. There might be a discussion about this on the talk page. (April 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Biologist Bruce Bagemihl writes "...the point of reference for "heterosexual" or "homosexual" orientation in this nomenclature is solely the individual's genetic sex prior to reassignment (see for example, Blanchard et al. 1987, Coleman and Bockting, 1988, Blanchard, 1989). These labels thereby ignore the individual's personal sense of gender identity taking precedence over biological sex, rather than the other way around." Bagemihl goes on to take issue with the way this terminology makes it easy to claim transsexuals are really homosexual males seeking to escape from stigma. Leavitt and Berger stated in 1990 that "The homosexual transsexual label is both confusing and controversial among males seeking sex reassignment. Critics argue that the term "homosexual transsexual" is "heterosexist", "archaic", and demeaning because it labels people by sex assigned at birth instead of their gender identity. Benjamin, Leavitt, and Berger have all used the term in their own work. Sexologist John Bancroft also recently expressed regret for having used this terminology, which was standard when he used it, to refer to transsexual women. He says that he now tries to choose his words more sensitively. Sexologist Charles Allen Moser is likewise critical of the terminology.

Use of androphilia and gynephilia was proposed and popularized by psychologist Ron Langevin in the 1980s. Psychologist Stephen T. Wegener writes, "Langevin makes several concrete suggestions regarding the language used to describe sexual anomalies. For example, he proposes the terms gynephilic and androphilic to indicate the type of partner preferred regardless of an individual's gender identity or dress. Those who are writing and researching in this area would do well to adopt his clear and concise vocabulary."

Psychiatrist Anil Aggrawal explains why the terms are useful in a glossary:

Androphilia – The romantic and/or sexual attraction to adult males. The term, along with gynephilia, is needed to overcome immense difficulties in characterizing the sexual orientation of transmen and transwomen. For instance, it is difficult to decide whether a transman erotically attracted to males is a heterosexual female or a homosexual male; or a transwoman erotically attracted to females is a heterosexual male or a lesbian female. Any attempt to classify them may not only cause confusion but arouse offense among the affected subjects. In such cases, while defining sexual attraction, it is best to focus on the object of their attraction rather than on the sex or gender of the subject.

Sexologist Milton Diamond, who prefers the term gynecophilia, writes, "The terms heterosexual, homosexual, and bisexual are better used as adjectives, not nouns, and are better applied to behaviors, not people." Diamond has encouraged using the terms androphilic, gynecophilic, and ambiphilic to describe the sexual-erotic partners one prefers (andro = male, gyneco = female, ambi = both, philic = to love). Such terms eliminate the need to specify the subject and focus instead on the desired partner. This usage is particularly advantageous when discussing the partners of transsexual or intersexed individuals. These newer terms also do not carry the social weight of the former ones."

Psychologist Rachel Ann Heath writes, "The terms homosexual and heterosexual are awkward, especially when the former is used with, or instead of, gay and lesbian. Alternatively, I use gynephilic and androphilic to refer to sexual preference for women and men, respectively. Gynephilic and androphilic derive from the Greek meaning love of a woman and love of a man respectively. So a gynephilic man is a man who likes women, that is, a heterosexual man, whereas an androphilic man is a man who likes men, that is, a gay man. For completeness, a lesbian is a gynephilic woman, a woman who likes other women. Gynephilic transsexed woman refers to a woman of transsexual background whose sexual preference is for women. Unless homosexual and heterosexual are more readily understood terms in a given context, this more precise terminology will be used throughout the book. Since homosexual, gay, and lesbian are often associated with bigotry and exclusion in many societies, the emphasis on sexual affiliation is both appropriate and socially just." Author Helen Boyd agrees, writing, "It would be much more accurate to define sexual orientation as either 'androphilic' (loving men) and 'gynephilic' (loving women) instead." Sociomedical scientist Rebecca Jordan-Young challenges researchers like Simon LeVay, J. Michael Bailey, and Martin Lalumiere, who she says "have completely failed to appreciate the implications of alternative ways of framing sexual orientation."

Gender in non-Western cultures

Some researchers advocate use of the terminology to avoid bias inherent in Western conceptualizations of human sexuality. Writing about the Samoan fa'afafine demographic, sociologist Johanna Schmidt writes:

Kris Poasa, Ray Blanchard and Kenneth Zucker (2004) also present an argument that suggests that fa'afafine fall under the rubric of 'transgenderal homosexuality', applying the same birth order equation to fa'afafine's families as have been used with 'homosexual transsexuals'. While no explicit causal relationship is offered, Poasa, Blanchard, and Zucker's use of the term 'homosexual transsexual' to refer to male-to-female transsexuals who are sexually oriented towards men draws an apparent link between sexual orientation and gender identity. This link is reinforced by mention of the fact that similar birth order equations have been found for 'homosexual men'. The possibility of sexual orientation towards (masculine) men emerging from (rather than causing) feminine gendered identities is not considered.

Schmidt argues that in cultures where a third gender is recognized, a term like "homosexual transsexual" does not align with cultural categories. She cites the work of Paul Vasey and Nancy Bartlett: "Vasey and Bartlett reveal the cultural specificity of concepts such as homosexuality, they continue to use the more 'scientific' (and thus presumably more 'objective') terminology of androphilia and gynephilia (sexual attraction to men or masculinity and women or femininity respectively) to understand the sexuality of fa'afafine and other Samoans." Researcher Sam Winter has presented a similar argument:

Terms such as 'homosexual' and heterosexual (and 'gay', 'lesbian', 'bisexual', etc.) are Western conceptions. Many Asians are unfamiliar with them, there being no easy translation into their native languages or sexological worldviews. However, I take the opportunity to put on record that I consider an androphilic transwoman (ie one sexually attracted to men) to be heterosexual because of her attraction to a member of another gender and a gynephilic transwoman (ie one attracted to women) as homosexual because she has a same-gender preference. My usage is contrary to much Western literature (particularly medical) which persists in referring to androphilic transwomen and gynephilic transman as homosexual (indeed as homosexual transsexual males and females, respectively).

See also

- Androgynophilia

- Attraction to transgender people

- Classification of transsexual and transgender people

- Effeminacy

- Demisexuality

- Femininity

- Gender-blind

- Gender expression

- Gender neutrality

- Index of human sexuality articles

- LGBTQ community

- LGBTQ symbols

- Masculinity

- Pansexuality

- Queer

- Queer heterosexuality

- Romantic orientation

- Sexual identity

- Sexual fluidity

- Sexuality

- Tomboy

- Transgender sexuality

References

- ^ Schmidt J (2010). Migrating Genders: Westernisation, Migration, and Samoan Fa'afafine. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., p. 45, ISBN 978-1-4094-0273-2

- ^ Diamond M (2010). Sexual orientation and gender identity. In Weiner IB, Craighead EW eds. The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, Volume 4. p. 1578. John Wiley and Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-17023-6

- Turban J, de Vries ALC, Zucker KJ, & Shadianloo S (2018). Transgender and gender non-conforming youth. The International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions, p. 3. Accessed 31 August 2022.

- Hirschfeld M (1948). Sexual anomalies: the origins, nature and treatment of sexual disorders : a summary of the works of Magnus Hirschfeld. Emerson Books, OCLC 1041032404

- Dynes W.R. & Donaldson S (1990). Encyclopedia of homosexuality, Volume 1. Garland Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8240-6544-7

- Franklin K (2010). Hebephilia: quintessence of diagnostic pretextuality. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, volume 28, issue 6, pp. 751–768, doi:10.1002/bsl.934, PMID 21110392

- Tucker N (1995). Bisexual politics: theories, queries, and visions. Psychology Press, ISBN 978-1-56024-950-4

- Covell G, Russell PF, Hendrik N (1953). Malaria terminology: Report of a drafting committee appointed by the World Health Organization. World Health Organization, ISBN 9241400137

- Calandra RS, Podestá EJ, Rivarola MA, Blaquier JA (1974). Tissue androgens and androphilic proteins in rat epididymis during sexual development Steroids, volume 24, issue 4, pp. 507-518 doi:10.1016/0039-128X(74)90132-9

- Cholmeley RJ (1901). The idylls of Theocritus. G. Bell & Sons, p. 98

- Rummel, E (1996). Erasmud on Women. University of Toronto Press, p. 82, ISBN 978-0-8020-7808-7

- Brown GW (1979). Depression: A sociologist's view. Trends in Neurosciences, Volume 2, pp. 253–256 doi:10.1016/0166-2236(79)90099-7

- Kahane C (2004). Freud and the passions of the voice. In O'Neill J (2004). Freud and the Passions. Penn State Press, ISBN 978-0-271-02564-3

- Freud, S (1908). Letter from Sigmund Freud to Sándor Ferenczi, March 25 1908. Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing. Accessed 31 August 2022. Quote: "I have often seen it so: a woman unsatisfied by a man naturally turns to a woman and tries to invest her long-suppressed gynecophilic component with libido."

- Money J (1986). Venuses Penuses: Sexology, Sexosophy, and Exigency Theory. Prometheus Books, ISBN 978-0-87975-327-6

- Chodorow N (1999). The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22155-0

- Blanchard R, Barbaree HE, Bogaert AF, Dickey R, Klassen P, Kuban ME, & Zucker KJ (2000). Fraternal birth order and sexual orientation in paedophiles. Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 29, issue 5, pp. 463–478, doi:10.1023/A:1001943719964, PMID 10983250, S2CID 19755751

- Feierman JR (1992). Reply to Dickemann: The ethology of variant sexology. Human Nature, volume 3, number 3, pp. 279–297, doi:10.1007/BF02692242, PMID 24222432

- Howitt D (1995). Introducing the paedophile. In Paedophiles and sexual offences against children. J. Wiley,ISBN 9780471939399

- Freund K, Steiner BW, & Chan S (1982). Two types of cross-gender identity. Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 11, issue 1, pp. 49–64, doi:10.1007/bf01541365, PMID 7073469, S2CID 42131695

- Blanchard, R. (1985). Research Methods for the Typological Study of Gender Disorders in Males. In: Steiner, B.W. (eds) Gender Dysphoria. Perspectives in Sexuality. Springer, Boston, MA. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-4784-2_8, S2CID 140817009

- Veale JF, Clarke DE, & Lomax TC (2008). Sexuality of male-to-female transsexuals. Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 37, issue 4, pp. 586-597, doi:10.1007/s10508-007-9306-9, PMID 18299976

- Freund K, Heasman G, Racansky IG, & Glancy G (1984). Pedophilia and heterosexuality vs. homosexuality. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, volume 10, issue 3, pp. 193-200, doi:10.1080/00926238408405945

- Weinrich JD (1987). Sexual landscapes: why we are what we are, why we love whom we love. Scribner's, ISBN 978-0-684-18705-1

- ^ Benjamin H (1966). The transsexual phenomenon. The Julian Press, Inc., ISBN 9780446824262

- Blanchard R (1988). Nonhomosexual gender dysphoria. Journal of Sex Research, volume 24, pp. 188-193, doi:10.1080/00224498809551410

- Coleman E & Bockting WO (1988). "Heterosexual" prior to sex reassignment—"homosexual" afterwards: A case study of a female-to-male transsexual. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, volume 1, issue 2, pp. 69–82, doi:10.1300/J056v01n01_11

- Blanchard R (1989). The concept of autogynephilia and the typology of male gender dysphoria. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, volume 177, issue 10, pp. 616–623, doi:10.1097/00005053-198910000-00004

- ^ Bagemihl B (1997). Surrogate phonology and transsexual faggotry: A linguistic analogy for uncoupling sexual orientation from gender identity. In Queerly Phrased: Language, Gender, and Sexuality. Livia A & Hall K (eds). Oxford University Press, p. 380 ff, ISBN 0-19-510471-4

- ^ Leavitt F & Berger JC (1990). Clinical patterns among male transsexual candidates with erotic interest in males. Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 19, issue 5, pp. 491–505, doi:10.1007/BF02442350, PMID 2260914

- Morgan Jr AJ (1978). Psychotherapy for transsexual candidates screened out of surgery. Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 7, pp. 273–282, doi:10.1007/BF01542035, PMID 697564

- Wahng SJ (2004). Double Cross: Transamasculinity Asian American Gendering. In Trappings of Transhood. In Aldama AJ (ed.) Violence and the Body: Race, Gender, and the State. Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-34171-X

- Leiblum SR & Rosen RC (2000). Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy, third edition. Guilford Press of New York, p. c2000, ISBN 1-57230-574-6

- ^ Bancroft J (2008). Lust or Identity? Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 37, issue 3, pp. 426–428, doi:10.1007/s10508-008-9317-1, PMID 18431640, S2CID 33178427

- Moser C (2010). Blanchard's Autogynephilia Theory: A Critique. Journal of Homosexuality, volume 57, edition 6, issue 6, pp. 790–809, doi:10.1080/00918369.2010.486241, PMID 20582803, S2CID 8765340

- Langevin R (1982). Sexual Strands: Understanding and Treating Sexual Anomalies in Men. Routledge, ISBN 978-0-89859-205-4

- Wegener ST (1984). Male sexual anomalies: the data (review of Sexual Strands) APA Review of Books, volume 29, issues 7–12, p. 783, Volume 29, Issues 7–12, p. 783.

- Aggrawal A (2008). Forensic and medico-legal aspects of sexual crimes and unusual sexual practices. CRC Press, ISBN 978-1-4200-4308-2

- Heath RA (2006). The Praeger handbook of transsexuality: Changing gender to match mindset. Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 978-0-275-99176-0

- Boyd H (2007). She's not the man I married: My life with a transgender husband. Seal Press, p. 102, ISBN 978-1-58005-193-4

- Jordan-Young RM (2010). Brain storm: the flaws in the science of sex differences. Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-05730-2

- Schmidt J (2001). Redefining fa'afafine: Western discourses and the construction of transgenderism in Samoa. Intersections: Gender, history and culture in the Asian context, issue 6.

- Winter S (2010). Lost in Transition: Transpeople, Transprejudice and Pathology in Asia. In Chan PCW (ed.) The Protection of Sexual Minorities Since Stonewall: Progress and Stalemate in Developed and Developing Countries. Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-41850-8

Bibliography

- Hames RB, Garfield ZH, & Garfield MJ (2017). Is Male Androphilia a Context-Dependent Cross-Cultural Universal? Archives of Sexual Behavior, volume 46, p. 132, doi:10.1007/s10508-016-0855-7

| Gender and sexual identities | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender identities | |||||||||

| Sexual orientation identities |

| ||||||||

| See also | |||||||||