| Revision as of 17:08, 21 March 2006 editEskimbot (talk | contribs)37,916 editsm robot Modifying: fr← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 04:12, 27 November 2024 edit undo2603:6010:5300:45:e0f5:3e55:9dbe:4ffc (talk) →Description: Removed unsourced and unprofessionally written editorializing about size, as well as unnecessary quoteTags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit | ||

| (406 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|Sauropod dinosaur genus from the Early Cretaceous period}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

| | color = pink | |||

| {{speciesbox | |||

| | name = ''Sauroposeidon'' | |||

| | fossil_range = <br/>] (]–]), {{fossilrange|118|110|ref=<ref name="Holtz2008">{{cite web|last1=Holtz|first1=T. R.|title=Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix|url=http://www.geol.umd.edu/~tholtz/dinoappendix/HoltzappendixWinter2011.pdf|access-date=September 21, 2022|date=2011}}</ref>}} | |||

| | status = {{StatusFossil}} | |||

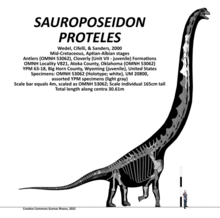

| | image = Sauroposeidon proteles Skeletal.png | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| | image_caption = Skeletal reconstruction of the holotype of ''S. proteles'' | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | display_parents = 2 | |||

| | classis = ] | |||

| | genus = Sauroposeidon | |||

| | superordo = ] | |||

| | parent_authority = Wedel, Cifelli & Sanders, 2000 | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | species = proteles | |||

| | infraordo = ] | |||

| | authority = Wedel, Cifelli & Sanders, 2000 | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| | synonyms = *''Superposeidon'' <br/><small>Brochu, Long, McHenry, Scanlon, & Willis, 2002 ('']'')<ref name="Brochu et al. 2002">{{cite book |last1=Brochu |first1=C.A. |last2=Long |first2=J. |last3=McHenry |first3=C. |last4=Scanlon |first4=J.D. |last5=Willis |first5=P. |date=2002 |editor-last=Brett-Surman |editor-first=M.K. |title=A Guide to Dinosaurs |location=San Francisco, CA |publisher=Fog City Press |pages=112–205 |isbn=1-877019-12-7 |url=https://archive.org/details/guidetodinosaurs00 |url-access=registration}}</ref></small> | |||

| | genus = '''''Sauroposeidon''''' | |||

| *''Paluxysaurus jonesi'' <br/><small>Rose, 2007</small> | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Species | |||

| | subdivision = | |||

| ''S. proteles''<br/> | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''''Sauroposeidon''''' ({{IPAc-en|ˌ|s|ɔːr|oʊ-|p|oʊ-|ˈ|s|aɪ|d|ən}} {{respell|SOR|o-po|SY|dən}}; meaning "] ] ]", after the Greek god ]<ref name=Wedeletal2005>{{cite journal|last=Wedel |first=Mathew J. |author2=Cifelli, Richard L. |date=Summer 2005 |title=''Sauroposeidon'': Oklahoma's Native Giant |journal=Oklahoma Geology Notes |volume=65 |issue=2 |pages=40–57 |url=http://sauroposeidon.net/Wedel-Cifelli_2005_native-giant.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070621122509/http://www.sauroposeidon.net/Wedel-Cifelli_2005_native-giant.pdf |url-status=dead |archive-date=June 21, 2007 }}</ref><ref>According to Wedel ''et al.'' (2005), the etymology of the name is based on Poseidon's association with earthquakes, not the sea.</ref>) is a ] of ] ] known from several incomplete specimens including a bone bed and fossilized trackways that have been found in the U.S. states of ], ], and ]. | |||

| The tallest ] known, at 60 feet, '''''Sauroposeidon''''' (meaning "] ]-]") is an Early ] ] related to the '']''. The only specimen to date is represented by four neck ]. | |||

| The ]s were found in rocks dating from near the end of the ] (]–early ]), from about 113 to 110 million years ago, a time when sauropod diversity in North America had greatly diminished. It was the last known North American sauropod prior to ] of roughly 40 million years that ended with the appearance of '']'' during the ]. | |||

| ==Discovery== | |||

| The vertebrae were discovered, not far from the ] border, in a claystone outcrop that dates the fossils to about 110 million years ago (]). This falls within the Early ], specificially between the ] and ] epochs. | |||

| While the holotype remains were initially discovered in 1994, due to their unexpected age and unusual size they were initially misclassified as pieces of ]. A more detailed analysis in 1999 revealed their true nature which resulted in a minor media frenzy, and formal publication of the find the following year.<ref name="Wedeletal2000b">{{cite journal|last=Wedel|first=Mathew J.|author2=Cifelli, R. L.|author3=Sanders, R.. K.|s2cid=59141243|year=2000|title=Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur ''Sauroposeidon''|url=https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9efe/8db6eb32247f90a760110d5a9695977fb761.pdf|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200626075134/https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/9efe/8db6eb32247f90a760110d5a9695977fb761.pdf|url-status=dead|archive-date=June 26, 2020|journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica|volume=45|pages=343–388}}</ref> | |||

| The four neck vertebrae were discovered in ] at the Antlers Formation in ] by Dr. Richard Cifelli and a team from the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History. | |||

| ] analysis indicates that ''Sauroposeidon'' lived on the shores of the ], in a ]. Extrapolations based on the more completely known '']'' indicate that the head of ''Sauroposeidon'' could reach {{convert|16.5|–|18|m|ft|abbr=on}} in height with its neck extended, which would make it one of the tallest known dinosaurs. With an estimated length of {{convert|27|-|34|m|ft|abbr=on}} and a mass of {{convert|40|-|60|MT|ST|abbr=on}}, it also ranks among the longest and heaviest. However, this animal may not be as closely related to ''Brachiosaurus'' as previously thought, so these estimates may be inaccurate. | |||

| While discovered in 1994, the vertebrae were stored until three years later, when Dr. Cifelli gave them to a graduate student, Matt Wedel, to analyze as part of a project. After realizing the significance of the find, a press release was made in October of ], followed by official publication in the ''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'' in March of ]. The new species was dubbed ''S. proteles'', and the ] is OMNH 53062. | |||

| While initially described as a ] closely related to '']'' and '']'', the discovery of additional remains in the ] of ] suggested that it was in fact more closely related to the ], in the group ]. Analysis of these remains and comparison with others from ] supported this conclusion, and demonstrated that the more completely known sauropods from the ] (including a partial skull and fossil trackways) previously named '''''Paluxysaurus jonesi''''' also belonged to ''Sauroposeidon''.<ref name=cloverlyspecimen>{{cite journal | last1 = D'Emic | first1 = M.D. | last2 = Foreman | first2 = B.Z. | s2cid = 128486488 | year = 2012 | title = The beginning of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America: insights from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Wyoming | journal = Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology | volume = 32 | issue = 4| pages = 883–902 | doi = 10.1080/02724634.2012.671204| bibcode = 2012JVPal..32..883D }}</ref> It is the ] of ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.tsl.texas.gov/ref/abouttx/symbols.html |title=Texas State Symbols |publisher=] |access-date=December 13, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| The ] name comes from ''sauros'' (] for "lizard"), and '']'', a sea-god in ], who is also associated with earthquakes. The species name ''proteles'' also comes from the Greek, and means "perfect before the end" — which refers to the ''Sauroposeidon's'' status as the last, and most specialized giant sauropod known in North America during the Early Cretaceous. | |||

| ==Discovery== | |||

| ==Who's the biggest?== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| :"It's truly astonishing. It's arguably the ] ever to walk the earth." | |||

| The first fossils classified as ''Sauroposeidon'' were four neck vertebrae discovered in rural ], not far from the ] border, in a ] outcrop that dates the fossils to about 110 ] (]). This falls within the Early Cretaceous Period, specifically between the ] and ] epochs. These vertebrae were discovered in May 1994 at the ] in ] by dog trainer Bobby Cross and secured by Dr. Richard Cifelli and a team from the ] in May 1994 and August 1994. Initially the fossils were believed to be simply too large to be the remains of an animal, and due to the state of preservation, believed to be tree trunks. In fact, they are the longest such bones known in dinosaurs. Thus, the vertebrae were stored until 1999, when Dr. Cifelli gave them to a graduate student, ], to analyze as part of a project. Upon their realization of the find's significance, they issued a press release in October 1999, followed by official publication of their findings in the '']'' in March 2000. The new species was named ''S. proteles'', and the ] is OMNH 53062. It garnered immediate media attention leading to some sources calling it inaccurately the ] | |||

| ::— Richard Cifelli, discoverer of ''Sauroposeidon'' | |||

| The press release in 1999 immediately garnered international media attention, which led to many (inaccurate) news reports of "the largest dinosaur ever!". While it is true that the ''Sauroposeidon'' is probably the tallest known dinosaur, it is neither the longest nor the most massive. The '']'' and the '']'' are better candidates for the title "World's Largest Dinosaur", though weak ] evidence makes an exact ranking impossible. | |||

| The ''Sauroposeidon'' find was composed of four articulated, mid-cervical vertebrae (numbers 5 to 8), with the cervical ]s in place. The vertebrae are extremely elongated, with the largest one about 1.2 ]s (4 ]) long, which makes it the longest on record. Examination of the ]s revealed that they are honeycombed with tiny air cells, and are very thin, like the bones of a ] or an ], making the neck lighter and easier to lift. | |||

| The generic name comes from ''sauros'' (] σαύρος for "lizard"), and '']'' (Ποσειδών), the ] ] in ], who is also associated with ]s, that facet styled as Ennosigaios or Enosikhthōn, "Earthshaker". This is a reference to the notion that a sauropod's weight was so great that the ground shook as it walked.]The ] ''proteles'' also comes from the Ancient Greek πρωτέλης and means "perfect before the end", which refers to ''Sauroposeidon's'' status as the last and most specialized giant sauropod known in North America, during the Early Cretaceous. | |||

| Estimates of size are based on a comparison between the four ''Sauroposeidon'' vertebrae and the vertebrae of the HM SII specimen of ''] brancai'', located in the ] in ]. The HM SII is the most complete brachiosaur known, though since it is composed of pieces from different individuals its proportions may not be totally accurate. Comparisons to the other brachiosaurid cousins of the ''Sauroposeidon'' would be difficult due to limited remains. | |||

| In 2012, numerous other sauropod remains that had been known for decades under various different names were also classified in the genus ''Sauroposeidon''.<ref name="cloverlyspecimen" /> Sauropod bones and ] had long been known from the ] area of Texas, usually referred to the genus '']'', including partial skeletons (particularly from the ], above the Twin Mountains Formation). In the mid 1980s, students from the ] discovered a bonebed on a ranch in Hood County, but early work stopped in 1987. The quarry was reopened in 1993 and was subsequently worked by parties from ], the ], and ]. All sauropod remains from this bonebed appear to come from the same genus of sauropod. ] are also known from the site. The site was ] when its rocks were being deposited, with channel sands and muds, and ]s of ]-cemented ] containing fossils. Following excavation and preparation of the majority of the fossils from the site, its sauropod species was given the name ''Paluxysaurus jonesi''.<ref name="PJR07">{{cite journal |last=Rose |first=Peter J. |year=2007 |title=A new titanosauriform sauropod (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Early Cretaceous of central Texas and its phylogenetic relationships |journal=Palaeontologia Electronica |volume=10 |issue=2 |url=http://palaeo-electronica.org/2007_2/00063/ |format=web pages |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131103022249/http://palaeo-electronica.org/2007_2/00063/00063.pdf |archive-date=November 3, 2013 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

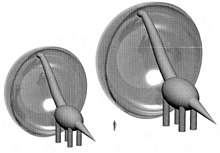

| ]]] | |||

| The name ''Paluxysaurus'' was ] the specimen FWMSH 93B-10-18, a partial skull including an associated left ], ], and teeth. Other bones from the quarry included a partial neck of seven ]e, thirteen vertebrae from the back and 30 from the tail, and examples of all limb and girdle bones except some hand and foot bones. It was ] from all other sauropods by vertebral details, and has various ] differences in other bones compared to other sauropods of the Early Cretaceous of North America. The genus was limited to the bonebed remains; for example, the partial skeleton from ] known as ''Pleurocoelus'' sp. (] 61732) is not referred to ''Paluxysaurus''; instead that specimen is the holotype of '']'' D'Emic 2012, another somphospondylan sauropod. There are differences in the remains of ''P.'' sp. and ''Paluxysaurus'', but they cannot be distinguished with confidence.<ref name=PJR07/> In 2012, re-analysis of these specimens in light of additional ''Sauroposeidon'' remains led paleontologists D'Emic and Foreman to conclude that ''Paluxysaurus'' was the same animal as ''Sauroposeidon'', and thus a junior synonym of ''S. proteles''.<ref name=cloverlyspecimen/> | |||

| ==Description== | |||

| The neck length of the ''Sauroposeidon'' is estimated at 37 to 39.5 feet (11.25 to 12 meters), compared to a neck length of 30 feet (9 meters) for the HM SII ''Brachiosaurus''. This is based on the assumption that the rest of the neck has the same proportions at the ''Brachiosaurus'', which is a reasonably good conjecture. | |||

| ] | |||

| The original ''Sauroposeidon'' find was composed of four articulated, mid-] vertebrae (numbers 5 to 8), with the cervical ]s{{Clarify|reason = Typically, cervical vertebrae do not articulate to "ribs" in the far more commonly used sense of "bones encompassing the thoracic cavity". There are, however, various processes, particularly in sauropods, that could be colloquially called "ribs". Which way we goin?|date=June 2015}} in place. The vertebrae are extremely elongated, with the largest one having an overall length of {{convert|1.4|m|ft|abbr=on}}, making it the longest sauropod neck vertebra on record.<ref name=Wedeletal2000a/> Examination of the ]s revealed that they are honeycombed with tiny air cells, and are very thin, like the bones of a ] or an ], making the neck lighter and easier to lift.<ref name=Wedeletal2000a>{{cite journal|last=Wedel|first=Mathew J. |author2=Cifelli, R.L. |author3=Sanders, R.K.|date=March 2000|title=''Sauroposeidon proteles'', a new sauropod from the Early Cretaceous of Oklahoma|journal=Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology|volume=20|issue=1|pages=109–114|doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2000)0202.0.CO;2|s2cid=55987496 |url=http://sauroposeidon.net/Wedel-et-al_2000a_sauroposeidon.pdf}}</ref> The cervical ribs were remarkably long as well, with the longest measurable rib (on vertebra 6) measuring {{convert|3.42|m|ft|abbr=on}} – about 18% longer than the longest rib reported for ''Giraffatitan'', but exceeded in length by the cervical ribs of '']''.<ref name=Wedeletal2000b/> | |||

| The ''Sauroposeidon'' was probably able to raise its head 60 feet (18 meters) above the ground, which is as high as a six-story building. The long neck and the high brachiosaurid shoulders are what makes it the tallest known dinosaur. In some ways, its build is similar to the modern ], with a short body and an extremely long neck. In comparison, the brachiosaur could probably raise its head 45 feet (13.5 meters) into the air, and the previous record holder, the '']'', might have been able to raise its head 50 feet (15 meters). | |||

| ] | |||

| Estimates of ''Sauroposeidon'''s size are based on a comparison between the four ''Sauroposeidon'' vertebrae and the vertebrae of the HM SII specimen of ''] brancai'', located in the ]. The HM SII is the most complete brachiosaur known, though since it is composed of pieces from different individuals its proportions may not be totally accurate. Comparisons to the other relatives of ''Sauroposeidon'' are difficult due to limited remains.<ref name=Wedeletal2000b/> | |||

| The neck length of ''Sauroposeidon'' is estimated at {{convert|11.25|-|12|m|ft|sigfig=2|abbr=on}}, compared to a neck length of {{convert|9|m|ft|abbr=on}} for the HM SII ''Giraffatitan''. This is based on the assumption that the rest of the neck has the same proportions as ''Giraffatitan'', which is a reasonably good conjecture.<ref name=Wedeletal2000b/> | |||

| ''Sauroposeidon'' was probably able to raise its head {{convert|16.5|–|18|m|ft|abbr=on}} above the ground, which is as high as a six-story building. In comparison, '']'' could probably raise its head {{convert|13.5|m|ft|abbr=on}} into the air.<ref>{{Cite book|last=Molina-Perez & Larramendi|title=Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs|publisher=Princeton University Press|year=2020|location=New Jersey|pages=55|bibcode=2020dffs.book.....M }}</ref><ref name=Wedeletal2000b/><ref name=Guinness>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=zs9aAAAAYAAJ&q=Sauroposeidon|title=Guinness World Records|publisher=Bantam Books|page=110|date=2004|isbn=9780553587128 }}</ref> | |||

| The ''Sauroposeidon's'' shoulders were probably 22 to 24 feet (7 meters) off the ground. Its estimated length is just under 100 feet (30 meters). | |||

| ''Sauroposeidon's'' shoulder height has been estimated at {{convert|6|-|7|m|ft|abbr=on}} based on an interpretation of the animal as a ]. Estimates of its total possible length have ranged from {{convert|27|m|ft|abbr=on}} to {{convert|34|m|ft|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Wedeletal2005/><ref name=Wedeletal2000b/><ref name="KC06">{{citation |last=Carpenter |first=Kenneth |title=Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation |pages=131–138 |year=2006 |editor=Foster, John R. |series=New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin '''36''' |chapter=Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod ''Amphicoelias fragillimus'' |location=Albuquerque |publisher=New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science |author-link=Kenneth Carpenter |editor2=Lucas, Spencer G. |mode=cs1}}</ref><ref name=G.S.Paul2016>Paul, G.S., 2016, ''The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd edition'', Princeton University Press p. 230</ref> | |||

| The mass of the ''Sauroposeidon'' is estimated at 50 to 60 ]nes (55 to 65 ]s). While the vertebrae of the ''Sauroposeidon'' are 25–33% longer than the brachiosaur's, they are only 10–15% larger in diameter. This means that while the ''Sauroposeidon'' probably has a larger body than the ''Brachiosaurus'' its body is smaller in comparison to the size of its neck, so it did not weigh as much as a scaled-up brachiosaur. By comparison, the brachiosaur might have weighed 36 to 40 tonnes (40 to 44 tons). This estimate of the brachiosaur is an average of several different methodologies. | |||

| The mass of ''Sauroposeidon'' is estimated at {{convert|40|-|60|MT|ST|abbr=on}}. While the vertebrae of ''Sauroposeidon'' are 25–33% longer than ''Giraffatitan''', they are only 10–15% larger in diameter. This means that while ''Sauroposeidon'' probably has a larger body than ''Giraffatitan'' its body is smaller in comparison to the size of its neck, so it did not weigh as much as a scaled-up ''Giraffatitan''. By comparison, ''Giraffatitan'' might have weighed {{convert|36|-|40|MT|ST|abbr=on}}. This estimate of the ''Giraffatitan'' is an average of several different methodologies.<ref name=Wedeletal2000b/><ref name=Guinness/><ref name=G.S.Paul2016/> | |||

| However, ''Sauroposeidon'' has a relatively gracile neck compared to the ''Brachiosaurus''. If the rest of the body turns out to be similarly slender, the mass estimate may be too high. This could be similar to the way the relatively chunky '']'' weighs far more than the longer but much slimmer ''Diplodocus''. In addition, it is possible that sauropods may have an air sac system, like those in ]s, which could reduce all sauropod mass estimates by 20% or more. | |||

| However, ''Sauroposeidon'' has a gracile neck compared to ''Giraffatitan''. If the rest of the body turns out to be similarly slender, the mass estimate may be too high. This could be similar to the way the relatively robust '']'' weighs far more than the longer but much slimmer '']''. In addition, it is possible that sauropods may have had an air sac system, like those in ]s, which could reduce all sauropod mass estimates by 20% or more. | |||

| ==Environment== | |||

| :"Sauroposeidon was an unexpected discovery, because it was a huge, gas-guzzling barge of an animal in an age of subcompact sauropods." | |||

| ::—Matt Wedel, ''Sauroposeidon'' team leader | |||

| ==Paleoecology== | |||

| The ''Sauroposeidon'' may be the last of the giant ] sauropods. Sauropods, which include the largest terrestrial animals of all time, were a very wide ranging and successful group. They first appeared in the Early ], and it wasn't long before they spread across the world. By the time of the late Jurassic, North America and ] were dominated by the diplodocids and brachiosaurids, and by the end of the Late Cretaceous, ]s were widespread. But in the middle, in the Early Cretaceous, the fossil record is sparse. Most of the other sauropods at the time were dying out, and as a result few specimens have been found in North American from that time, and those specimens that do exist are often fragmentary or represent juvenile members of their species. Most of the surviving sauropods at the time were also shrinking in size (to a mere 50 feet, or 15 meters, in length, and maybe 10 to 15 tons or tonnes), which makes the discovery of an extremely specialized super-giant like the ''Sauroposeidon'' very unusual. | |||

| ]'' and ''Sauroposeidon'']] | |||

| {{Quote|''Sauroposeidon'' was an unexpected discovery, because it was a huge, gas-guzzling barge of an animal in an age of subcompact sauropods.|], ''Sauroposeidon'' team leader<ref name=WedelInterview>{{cite web |last=Brusatte|first=Steve|url=http://www.geocities.com/stegob/mattwedel.html|title=Matt Wedel|access-date=2008-08-14|work=Paleontology Interviews|publisher=Dino Land|year=2000|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090903061947/http://geocities.com/stegob/mattwedel.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=2009-09-03}}</ref>}} | |||

| Sauropods, which include the largest terrestrial animals of all time, were a very wide-ranging and successful group. They first appeared in the Early ] and soon spread across the world. By the time of the late Jurassic, North America and ] were dominated by the diplodocids and brachiosaurids and, by the end of the Late Cretaceous, ]s were widespread (though only in the southern hemisphere). Between these periods, in the Early Cretaceous, the fossil record is sparse. Few specimens have been found in North America from that time and those specimens that do exist are often fragmentary or represent juvenile members of their species. Most of the surviving sauropods at the time were also shrinking in size to a mere {{convert|15|m|ft|abbr=on}} in length, and maybe {{convert|10|-|15|MT|ST|abbr=on}}, which makes the discovery of an extremely specialized super-giant like ''Sauroposeidon'' very unusual. | |||

| The ''Sauroposeidon'' lived on the shores of the ], which ran through Oklahoma at that time, in a vast ], similar to the ] today. There were probably no predators who could take down a full-grown ''Sauroposeidon'', but juveniles were likely prey to the '']'' (a ] a little smaller than a '']''), and packs of '']''. | |||

| ''Sauroposeidon'' lived on the shores of the ], which ran through Oklahoma at that time, in a vast ] similar to the ] today. This paleoenvironment, which has been preserved in the ], also stretches from southwest Arkansas through southeastern Oklahoma and into northeastern Texas. This geological formation has not been dated radiometrically. Scientists have used biostratigraphic data and the fact that it shares several of the same genera as the Trinity Group of Texas, to surmise that this formation was laid down during the ] and ] stages of the Early Cretaceous Period, approximately 110 mya.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Wedel | first1 = M.J. | last2 = Cifelli | first2 = R.L. | year = 2005 | title = Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's native giant | journal = Oklahoma Geology Notes | volume = 65 | issue = 2| pages = 40–57 }}</ref> The area preserved in this formation was a large ] that drained into a shallow inland sea. Several million years later, this sea would expand to the north, becoming the ] and dividing North America in two for nearly the entire ] period. The paleoenvironment of ''Sauroposeidon'' consisted of tropical or sub-tropical forests, ]s, coastal swamps, bayous and lagoons, probably similar to that of modern-day ].<ref name=forster1995>{{cite journal | last1 = Forster | first1 = C. A. | year = 1984 | title = The paleoecology of the ornithopod dinosaur ''Tenontosaurus tilletti'' from the Cloverly Formation, Big Horn Basin of Wyoming and Montana | journal = The Mosasaur | volume = 2 | pages = 151–163 }}</ref> There were few predators which could attempt to attack a full-grown ''Sauroposeidon'', but juveniles were likely to be preyed on by the contemporary '']'' <ref>{{cite journal|title=Paleobiology and geographic range of the large-bodied Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis| doi=10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.003|volume=333–334|journal=Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology|pages=13–23|year=2012|last1=d'Emic|first1=Michael D.|last2=Melstrom|first2=Keegan M.|last3=Eddy|first3=Drew R.| bibcode=2012PPP...333...13D}}</ref> (a ] slightly smaller than a '']''), which likely were the ] in this region,<ref>Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth, M.P.; and Noto, Christopher R. (2004). ""Dinosaur Distribution"", in The Dinosauria (2nd), p. 264.</ref> and the small ] '']''. ''Sauroposeidon'' also shared its ] with other dinosaurs, such as the ] '']'' (Pleurocoelus)<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Brinkman | first1 = Daniel L. | last2 = Cifelli | first2 = Richard L. | last3 = Czaplewski | first3 = Nicholas J. | year = 1998 | title = First occurrence of Deinonychus antirrhopus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous: Aptian – Albian) of Oklahoma | journal = Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin | volume = 146 | pages = 1–27 }}</ref> and the most common dinosaur in this region, the ] '']''. Other vertebrates present during this time included the ] ''] arthridion'', the reptiles ''Atokasaurus metarsiodon'' and ''Ptilotodon wilsoni'', the ] fish ''] buderi'' and ''] anitae'', the ] fish ''] dumblei'', the ] '']'', '']'', and '']'', and the turtles '']'' and ''Naomichelys''.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Nydam | first1 = R.L. | last2 = Cifelli | first2 = R. L. | year = 2002a | title = Lizards from the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian-Albian) Antlers and Cloverly formations | journal = Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology | volume = 22 | issue = 2| pages = 286–298 | doi=10.1671/0272-4634(2002)0222.0.co;2| s2cid = 130788410 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Cifelli | first1 = R. Gardner | last2 = Nydam | first2 = R.L. | last3 = Brinkman | first3 = D.L. | year = 1999 | title = Additions to the vertebrate fauna of the Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous), southeastern Oklahoma | journal = Oklahoma Geology Notes | volume = 57 | pages = 124–131 }}</ref> Possible indeterminate bird remains are also known from the Antlers Formation. The fossil evidence suggests that the ] '']'' was the most common vertebrate in this region. The early mammals known from this region included ''Atokatherium boreni'' and ''] crossi''.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Kielan-Jarorowska | first1 = Z. | last2 = Cifelli | first2 = R.L. | year = 2001 | title = Primitive boreosphenidan mammal (?Deltatheroida) from the Early Cretaceous of Oklahoma | journal = Acta Palaeontologica Polonica | volume = 46 | pages = 377–391 }}</ref> | |||

| A giant brachiosaurid similar to ''Sauroposeidon'' was described in 2004 by ] and colleagues, and is from the Early ] of England. Known only from two neck vertebrae, it was apparently similar in some details to ''Sauroposeidon'' and perhaps similar in size. Its discovery highlights the similarity seen between Early Cretaceous North American and European dinosaurs. | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| * "''Sauroposeidon'' proteles, a new sauropod from the Early Cretaceous of Oklahoma", by Mathew J. Wedel, Richard L. Cifelli, and R. Kent Sanders (''Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology'' 29(1), pages 109–114, March 2000). | |||

| * "Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur ''Sauroposeidon''", by Mathew J. Wedel, Richard L. Cifelli, and R. Kent Sanders (''Acta Palaeontologica Polonica'' 45, pages 343–388, 2000). | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Portal|Dinosaurs}} | |||

| * ''Sauroposeidon's'' listing in the . | |||

| <!-- ''Sauroposeidon's'' listing in the ***NOTE - BROKEN LINK***. Maybe one day, it won't be --> | |||

| * A non-technical on Dino Land, with links to various news reports. | |||

| * |

* A non-technical on Dino Land, with links to various news reports. | ||

| * The of the ''Sauroposeidon'', at the Dinosauricon. | |||

| * of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural History, including the two technical papers listed under '']''. | |||

| {{Sauropodomorpha|M.}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Taxonbar|from=Q131693}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 04:12, 27 November 2024

Sauropod dinosaur genus from the Early Cretaceous period

| Sauroposeidon Temporal range: Early Cretaceous (Aptian–Albian), 118–110 Ma PreꞒ Ꞓ O S D C P T J K Pg N | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeletal reconstruction of the holotype of S. proteles | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Clade: | †Sauropoda |

| Clade: | †Macronaria |

| Clade: | †Somphospondyli |

| Genus: | †Sauroposeidon Wedel, Cifelli & Sanders, 2000 |

| Species: | †S. proteles |

| Binomial name | |

| †Sauroposeidon proteles Wedel, Cifelli & Sanders, 2000 | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Sauroposeidon (/ˌsɔːroʊpoʊˈsaɪdən/ SOR-o-po-SY-dən; meaning "lizard earthquake god", after the Greek god Poseidon) is a genus of sauropod dinosaur known from several incomplete specimens including a bone bed and fossilized trackways that have been found in the U.S. states of Oklahoma, Wyoming, and Texas.

The fossils were found in rocks dating from near the end of the Early Cretaceous (Aptian–early Albian), from about 113 to 110 million years ago, a time when sauropod diversity in North America had greatly diminished. It was the last known North American sauropod prior to an absence of the group on the continent of roughly 40 million years that ended with the appearance of Alamosaurus during the Maastrichtian.

While the holotype remains were initially discovered in 1994, due to their unexpected age and unusual size they were initially misclassified as pieces of petrified wood. A more detailed analysis in 1999 revealed their true nature which resulted in a minor media frenzy, and formal publication of the find the following year.

Paleoecological analysis indicates that Sauroposeidon lived on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, in a river delta. Extrapolations based on the more completely known Brachiosaurus indicate that the head of Sauroposeidon could reach 16.5–18 m (54–59 ft) in height with its neck extended, which would make it one of the tallest known dinosaurs. With an estimated length of 27–34 m (89–112 ft) and a mass of 40–60 t (44–66 short tons), it also ranks among the longest and heaviest. However, this animal may not be as closely related to Brachiosaurus as previously thought, so these estimates may be inaccurate.

While initially described as a brachiosaurid closely related to Brachiosaurus and Giraffatitan, the discovery of additional remains in the Cloverly Formation of Wyoming suggested that it was in fact more closely related to the titanosaurs, in the group Somphospondyli. Analysis of these remains and comparison with others from Texas supported this conclusion, and demonstrated that the more completely known sauropods from the Twin Mountains Formation (including a partial skull and fossil trackways) previously named Paluxysaurus jonesi also belonged to Sauroposeidon. It is the state dinosaur of Texas.

Discovery

The first fossils classified as Sauroposeidon were four neck vertebrae discovered in rural Oklahoma, not far from the Texas border, in a claystone outcrop that dates the fossils to about 110 million years ago (mya). This falls within the Early Cretaceous Period, specifically between the Aptian and Albian epochs. These vertebrae were discovered in May 1994 at the Antlers Formation in Atoka County, Oklahoma by dog trainer Bobby Cross and secured by Dr. Richard Cifelli and a team from the Oklahoma Museum of Natural History in May 1994 and August 1994. Initially the fossils were believed to be simply too large to be the remains of an animal, and due to the state of preservation, believed to be tree trunks. In fact, they are the longest such bones known in dinosaurs. Thus, the vertebrae were stored until 1999, when Dr. Cifelli gave them to a graduate student, Matt Wedel, to analyze as part of a project. Upon their realization of the find's significance, they issued a press release in October 1999, followed by official publication of their findings in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology in March 2000. The new species was named S. proteles, and the holotype is OMNH 53062. It garnered immediate media attention leading to some sources calling it inaccurately the largest dinosaur ever.

The generic name comes from sauros (Greek σαύρος for "lizard"), and Poseidon (Ποσειδών), the sea god in Greek mythology, who is also associated with earthquakes, that facet styled as Ennosigaios or Enosikhthōn, "Earthshaker". This is a reference to the notion that a sauropod's weight was so great that the ground shook as it walked.

The specific descriptor proteles also comes from the Ancient Greek πρωτέλης and means "perfect before the end", which refers to Sauroposeidon's status as the last and most specialized giant sauropod known in North America, during the Early Cretaceous.

In 2012, numerous other sauropod remains that had been known for decades under various different names were also classified in the genus Sauroposeidon. Sauropod bones and trackways had long been known from the Paluxy River area of Texas, usually referred to the genus Pleurocoelus, including partial skeletons (particularly from the Glen Rose Formation, above the Twin Mountains Formation). In the mid 1980s, students from the University of Texas at Austin discovered a bonebed on a ranch in Hood County, but early work stopped in 1987. The quarry was reopened in 1993 and was subsequently worked by parties from Southern Methodist University, the Fort Worth Museum of Science and History, and Tarleton State University. All sauropod remains from this bonebed appear to come from the same genus of sauropod. Petrified logs are also known from the site. The site was fluvial when its rocks were being deposited, with channel sands and muds, and concretions of calcite-cemented sandstone containing fossils. Following excavation and preparation of the majority of the fossils from the site, its sauropod species was given the name Paluxysaurus jonesi.

The name Paluxysaurus was based on the specimen FWMSH 93B-10-18, a partial skull including an associated left maxilla, nasal, and teeth. Other bones from the quarry included a partial neck of seven vertebrae, thirteen vertebrae from the back and 30 from the tail, and examples of all limb and girdle bones except some hand and foot bones. It was distinguished from all other sauropods by vertebral details, and has various morphological differences in other bones compared to other sauropods of the Early Cretaceous of North America. The genus was limited to the bonebed remains; for example, the partial skeleton from Wise County known as Pleurocoelus sp. (SMU 61732) is not referred to Paluxysaurus; instead that specimen is the holotype of Astrophocaudia slaughteri D'Emic 2012, another somphospondylan sauropod. There are differences in the remains of P. sp. and Paluxysaurus, but they cannot be distinguished with confidence. In 2012, re-analysis of these specimens in light of additional Sauroposeidon remains led paleontologists D'Emic and Foreman to conclude that Paluxysaurus was the same animal as Sauroposeidon, and thus a junior synonym of S. proteles.

Description

The original Sauroposeidon find was composed of four articulated, mid-cervical vertebrae (numbers 5 to 8), with the cervical ribs in place. The vertebrae are extremely elongated, with the largest one having an overall length of 1.4 m (4.6 ft), making it the longest sauropod neck vertebra on record. Examination of the bones revealed that they are honeycombed with tiny air cells, and are very thin, like the bones of a chicken or an ostrich, making the neck lighter and easier to lift. The cervical ribs were remarkably long as well, with the longest measurable rib (on vertebra 6) measuring 3.42 m (11.2 ft) – about 18% longer than the longest rib reported for Giraffatitan, but exceeded in length by the cervical ribs of Mamenchisaurus.

Estimates of Sauroposeidon's size are based on a comparison between the four Sauroposeidon vertebrae and the vertebrae of the HM SII specimen of Giraffatitan brancai, located in the Berlin's Natural History Museum. The HM SII is the most complete brachiosaur known, though since it is composed of pieces from different individuals its proportions may not be totally accurate. Comparisons to the other relatives of Sauroposeidon are difficult due to limited remains. The neck length of Sauroposeidon is estimated at 11.25–12 m (37–39 ft), compared to a neck length of 9 m (30 ft) for the HM SII Giraffatitan. This is based on the assumption that the rest of the neck has the same proportions as Giraffatitan, which is a reasonably good conjecture.

Sauroposeidon was probably able to raise its head 16.5–18 m (54–59 ft) above the ground, which is as high as a six-story building. In comparison, Giraffatitan could probably raise its head 13.5 m (44 ft) into the air.

Sauroposeidon's shoulder height has been estimated at 6–7 m (20–23 ft) based on an interpretation of the animal as a brachiosaurid. Estimates of its total possible length have ranged from 27 m (89 ft) to 34 m (112 ft).

The mass of Sauroposeidon is estimated at 40–60 t (44–66 short tons). While the vertebrae of Sauroposeidon are 25–33% longer than Giraffatitan', they are only 10–15% larger in diameter. This means that while Sauroposeidon probably has a larger body than Giraffatitan its body is smaller in comparison to the size of its neck, so it did not weigh as much as a scaled-up Giraffatitan. By comparison, Giraffatitan might have weighed 36–40 t (40–44 short tons). This estimate of the Giraffatitan is an average of several different methodologies.

However, Sauroposeidon has a gracile neck compared to Giraffatitan. If the rest of the body turns out to be similarly slender, the mass estimate may be too high. This could be similar to the way the relatively robust Apatosaurus weighs far more than the longer but much slimmer Diplodocus. In addition, it is possible that sauropods may have had an air sac system, like those in birds, which could reduce all sauropod mass estimates by 20% or more.

Paleoecology

Sauroposeidon was an unexpected discovery, because it was a huge, gas-guzzling barge of an animal in an age of subcompact sauropods.

— Matt Wedel, Sauroposeidon team leader

Sauropods, which include the largest terrestrial animals of all time, were a very wide-ranging and successful group. They first appeared in the Early Jurassic and soon spread across the world. By the time of the late Jurassic, North America and Africa were dominated by the diplodocids and brachiosaurids and, by the end of the Late Cretaceous, titanosaurids were widespread (though only in the southern hemisphere). Between these periods, in the Early Cretaceous, the fossil record is sparse. Few specimens have been found in North America from that time and those specimens that do exist are often fragmentary or represent juvenile members of their species. Most of the surviving sauropods at the time were also shrinking in size to a mere 15 m (49 ft) in length, and maybe 10–15 t (11–17 short tons), which makes the discovery of an extremely specialized super-giant like Sauroposeidon very unusual.

Sauroposeidon lived on the shores of the Gulf of Mexico, which ran through Oklahoma at that time, in a vast river delta similar to the Mississippi delta today. This paleoenvironment, which has been preserved in the Antlers Formation, also stretches from southwest Arkansas through southeastern Oklahoma and into northeastern Texas. This geological formation has not been dated radiometrically. Scientists have used biostratigraphic data and the fact that it shares several of the same genera as the Trinity Group of Texas, to surmise that this formation was laid down during the Aptian and Albian stages of the Early Cretaceous Period, approximately 110 mya. The area preserved in this formation was a large floodplain that drained into a shallow inland sea. Several million years later, this sea would expand to the north, becoming the Western Interior Seaway and dividing North America in two for nearly the entire Late Cretaceous period. The paleoenvironment of Sauroposeidon consisted of tropical or sub-tropical forests, river deltas, coastal swamps, bayous and lagoons, probably similar to that of modern-day Louisiana. There were few predators which could attempt to attack a full-grown Sauroposeidon, but juveniles were likely to be preyed on by the contemporary Acrocanthosaurus atokensis (a carnosaur slightly smaller than a Tyrannosaurus), which likely were the apex predators in this region, and the small dromaeosaur Deinonychus antirrhopus. Sauroposeidon also shared its paleoenvironment with other dinosaurs, such as the sauropod Astrodon (Pleurocoelus) and the most common dinosaur in this region, the ornithopod Tenontosaurus. Other vertebrates present during this time included the amphibian Albanerpeton arthridion, the reptiles Atokasaurus metarsiodon and Ptilotodon wilsoni, the cartilaginous fish Hybodus buderi and Lissodus anitae, the ray-finned fish Gyronchus dumblei, the crocodilians Goniopholis, Bernissartia, and Paluxysuchus, and the turtles Glyptops and Naomichelys. Possible indeterminate bird remains are also known from the Antlers Formation. The fossil evidence suggests that the gar Lepisosteus was the most common vertebrate in this region. The early mammals known from this region included Atokatherium boreni and Paracimexomys crossi.

References

- Holtz, T. R. (2011). "Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages, Winter 2011 Appendix" (PDF). Retrieved September 21, 2022.

- Brochu, C.A.; Long, J.; McHenry, C.; Scanlon, J.D.; Willis, P. (2002). Brett-Surman, M.K. (ed.). A Guide to Dinosaurs. San Francisco, CA: Fog City Press. pp. 112–205. ISBN 1-877019-12-7.

- ^ Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, Richard L. (Summer 2005). "Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant" (PDF). Oklahoma Geology Notes. 65 (2): 40–57. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 21, 2007.

- According to Wedel et al. (2005), the etymology of the name is based on Poseidon's association with earthquakes, not the sea.

- ^ Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, R. L.; Sanders, R.. K. (2000). "Osteology, paleobiology, and relationships of the sauropod dinosaur Sauroposeidon" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 45: 343–388. S2CID 59141243. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 26, 2020.

- ^ D'Emic, M.D.; Foreman, B.Z. (2012). "The beginning of the sauropod dinosaur hiatus in North America: insights from the Lower Cretaceous Cloverly Formation of Wyoming". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 32 (4): 883–902. Bibcode:2012JVPal..32..883D. doi:10.1080/02724634.2012.671204. S2CID 128486488.

- "Texas State Symbols". Texas State Legislature. Retrieved December 13, 2017.

- ^ Rose, Peter J. (2007). "A new titanosauriform sauropod (Dinosauria: Saurischia) from the Early Cretaceous of central Texas and its phylogenetic relationships" (web pages). Palaeontologia Electronica. 10 (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on November 3, 2013.

- ^ Wedel, Mathew J.; Cifelli, R.L.; Sanders, R.K. (March 2000). "Sauroposeidon proteles, a new sauropod from the Early Cretaceous of Oklahoma" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 20 (1): 109–114. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2000)020[0109:SPANSF]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 55987496.

- Molina-Perez & Larramendi (2020). Dinosaur Facts and Figures: The Sauropods and Other Sauropodomorphs. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. p. 55. Bibcode:2020dffs.book.....M.

- ^ Guinness World Records. Bantam Books. 2004. p. 110. ISBN 9780553587128.

- Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36. Albuquerque: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

- ^ Paul, G.S., 2016, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd edition, Princeton University Press p. 230

- Brusatte, Steve (2000). "Matt Wedel". Paleontology Interviews. Dino Land. Archived from the original on September 3, 2009. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- Wedel, M.J.; Cifelli, R.L. (2005). "Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's native giant". Oklahoma Geology Notes. 65 (2): 40–57.

- Forster, C. A. (1984). "The paleoecology of the ornithopod dinosaur Tenontosaurus tilletti from the Cloverly Formation, Big Horn Basin of Wyoming and Montana". The Mosasaur. 2: 151–163.

- d'Emic, Michael D.; Melstrom, Keegan M.; Eddy, Drew R. (2012). "Paleobiology and geographic range of the large-bodied Cretaceous theropod dinosaur Acrocanthosaurus atokensis". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 333–334: 13–23. Bibcode:2012PPP...333...13D. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.003.

- Weishampel, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Coria, Rodolfo A.; Le Loeuff, Jean; Xu Xing; Zhao Xijin; Sahni, Ashok; Gomani, Elizabeth, M.P.; and Noto, Christopher R. (2004). ""Dinosaur Distribution"", in The Dinosauria (2nd), p. 264.

- Brinkman, Daniel L.; Cifelli, Richard L.; Czaplewski, Nicholas J. (1998). "First occurrence of Deinonychus antirrhopus (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous: Aptian – Albian) of Oklahoma". Oklahoma Geological Survey Bulletin. 146: 1–27.

- Nydam, R.L.; Cifelli, R. L. (2002a). "Lizards from the Lower Cretaceous (Aptian-Albian) Antlers and Cloverly formations". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (2): 286–298. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0286:lftlca]2.0.co;2. S2CID 130788410.

- Cifelli, R. Gardner; Nydam, R.L.; Brinkman, D.L. (1999). "Additions to the vertebrate fauna of the Antlers Formation (Lower Cretaceous), southeastern Oklahoma". Oklahoma Geology Notes. 57: 124–131.

- Kielan-Jarorowska, Z.; Cifelli, R.L. (2001). "Primitive boreosphenidan mammal (?Deltatheroida) from the Early Cretaceous of Oklahoma". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 46: 377–391.

External links

- A non-technical article on Dino Land, with links to various news reports.

| Taxon identifiers | |

|---|---|

| Sauroposeidon | |

- Early Cretaceous dinosaurs of North America

- Fossil taxa described in 2000

- Macronarians

- Taxa named by Matt J. Wedel

- Cloverly fauna

- Paleontology in Oklahoma

- Paleontology in Wyoming

- Paleontology in Texas

- Cretaceous Oklahoma

- Cretaceous Texas

- Aptian genus first appearances

- Albian genus extinctions

- Sauropods of North America

- Early Cretaceous sauropods

- Symbols of Texas

- Monotypic sauropod genera