| Revision as of 03:53, 21 September 2011 editJeff G. (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, File movers, IP block exemptions, New page reviewers, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers116,567 editsm Reverted edits by Jeff G. (talk) to last revision by Dawnseeker2000 (HG)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:49, 10 January 2025 edit undo2.96.239.23 (talk) corrected infoTag: Manual revert | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Street in Manhattan, New York}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{about|the street in Lower Manhattan|the neighborhood commonly referred to as Wall Street|Financial District, Manhattan|the U.S. economy at large, for which "Wall Street" is commonly used as a metonym|Economy of the United States|other uses|Wall Street (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=September 2010}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=July 2023}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=July 2022}} | |||

| {{Infobox street | {{Infobox street | ||

| | image_map = {{maplink}} | |||

| |marker_image= | |||

| | map_size = 320 | |||

| |name=Wall Street | |||

| | marker_image = | |||

| |alternate_name= | |||

| | |

| name = Wall Street | ||

| | native_name = {{native name|nl|Het Cingel}} | |||

| |maint= | |||

| | image = Photos NewYork1 032.jpg | |||

| |map= | |||

| | image_size = 255px | |||

| |length_mi= | |||

| | caption = The ]'s ] facade (right) as seen from Wall Street, April 2005. ], the former headquarters of financial firm ], is visible at the far left. | |||

| |length_round= | |||

| | maint = | |||

| |length_ref= | |||

| | length_mi = | |||

| |length_notes= | |||

| | length_round = | |||

| |established= | |||

| | direction_a = West | |||

| |decommissioned= | |||

| | terminus_a = ] | |||

| |direction_a=West | |||

| | junction = | |||

| |terminus_a=] in ] | |||

| | direction_b = East | |||

| |junction= | |||

| | terminus_b = ] | |||

| |direction_b=East | |||

| |terminus_b=] in ] | |||

| |counties= | |||

| |cities= | |||

| |system= | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] as seen from Wall Street]] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{New Netherland}} | {{New Netherland}} | ||

| '''Wall Street''' is a street in the ] of ] in ]. It runs eight ]s between ] in the west and ] and the ] in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a ] for the ]s of the United States as a whole, the ], New York–based financial interests, or the Financial District. Anchored by Wall Street, New York has been described as the world's principal ] and ].<ref name=WallStreetFintechlAndFinancialCapitalWorld>{{cite web|url = https://www.longfinance.net/publications/long-finance-reports/the-global-financial-centres-index-36/|title = The Global Financial Centres Index 36|date = September 24, 2024|publisher = Long Finance|access-date = September 27, 2024}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url = https://www.reuters.com/business/new-york-widens-lead-over-london-top-finance-centres-index-2022-03-24/ |title = New York widens lead over London in top finance centres index |website = Reuters |access-date = September 27, 2024 |last1 = Jones |first1 = Huw }}</ref> | |||

| '''Wall Street''' refers to the ] of ],<ref>, retrieved July 17, 2007.</ref> named after and centered on the eight-block-long street running from ] to ] on the ] in ]. Over time, the term has become a ] for the financial markets of the ] as a whole, or signifying New York-based financial interests.<ref>, retrieved July 17, 2007.</ref> It is the home of the ], the world's largest stock exchange by market capitalization of its listed companies.<ref></ref> Several other major exchanges have or had headquarters in the Wall Street area, including ], the ], the ], and the former ]. Anchored by Wall Street, New York City is one of the world's principal ]s.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cnbc.com/id/29862382/The_World_s_Most_Expensive_Real_Estate_Markets?slide=9|title=The World's Most Expensive Real Estate Markets|publisher=CNBC|accessdate=May 31, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book|url=http://books.google.com/books?id=dWA7aEbsy8QC&pg=PA154&dq=new+york+financial+capital+of+the+world+2010#v=onepage&q=new%20york%20financial%20capital%20of%20the%20world%202010&f=false|title=The Best 301 Business Schools 2010 by Princeton Review, Nedda Gilbert|accessdate=May 31, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://noir.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aEC0OYmvvcZM|title=New York Eclipses London as Financial Center in Bloomberg Poll |publisher=Bloomberg News|accessdate=March 30, 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123940286075109617.html|title=The Tax Capital of the World|publisher=The Wall Street Journal|accessdate=May 31, 2010 | date=April 11, 2009}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://justoneminute.typepad.com/main/2010/04/editorializing-from-the-financial-capital-of-the-world.html|title=JustOneMinute – Editorializing From The Financial Capital Of The World|accessdate=May 31, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.marketwatch.com/story/credit-crunch-shows-new-york-is-still-worlds-financial-capital/|title=London may have the IPOs...|publisher=Marketwatch|accessdate=May 31, 2010}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.cincodias.com/articulo/mercados/Londres-versus-Nueva-York/20080901cdscdimer_3/cdsmer/|title=Fondos – Londres versus Nueva York|format=PDF|publisher=Cinco Dias|accessdate=May 31, 2010}}</ref> | |||

| The street was originally known in ] as ''Het Cingel'' ("the Belt") when it was part of ] during the 17th century. An actual city wall existed on the street from 1653 to 1699. During the 18th century, the location served as a ] and ], and from 1703 onward, the location of New York's city hall, which became ]. In the early 19th century, both residences and businesses occupied the area, but increasingly the latter predominated, and New York's financial industry became centered on Wall Street. During the 20th century, several ] were built on Wall Street, including ], once the world's tallest building. The street is near multiple ] stations and ]. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ] from 1660, showing the wall on the right side]] | |||

| ] subway station]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ]. Today it's the home of the ].]] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The Wall Street area is home to the ], the world's ] by total ], as well as the ], and commercial banks and insurance companies. Several other stock and ] exchanges have also been located in Lower Manhattan near Wall Street, including the ] and other commodity futures exchanges, along with the ]. Many brokerage firms owned offices nearby to support the business they did on the exchanges. The economic impacts of Wall Street activities extend worldwide. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| ===Early years=== | ===Early years=== | ||

| ]'', from 1660, showing the wall on the right side]] | |||

| There are varying accounts about how the Dutch-named "de Waal Straat"<ref name="let.rug.nl"></ref> got its name. A generally accepted version is that the name of the street name was derived from an earthen wall on the northern boundary of the ] settlement, perhaps to protect against English colonial encroachment or incursions by native Americans. A conflicting explanation is that Wall Street was named after '']'' -- possibly a Dutch abbreviation for ''Walloon'' being ''Waal''.<ref name = walloonswallets>{{cite news | url = http://www.loc.gov/wiseguide/mar09/wallets.html | title = Walloons and Wallets| date = 2009-03 | accessdate = 2010-09-24 | publisher = the loc.gov}}</ref> Among the first settlers that embarked on the ship "Nieu Nederlandt" in 1624 were 30 Walloon families. | |||

| ] | |||

| In the original records of ], the Dutch always called the street ''Het Cingel'' ("the Belt"), which was also the name of the original outer barrier street, wall, and canal of ]. After the English ] in 1664, they renamed the settlement "New York" and in tax records from April 1665 (still in Dutch) they refer to the street as ''Het Cingel ofte Stadt Wall'' ("the Belt or the City Wall").<ref name="DORIS2017">{{Cite web |title=The Dutch & the English, Part 2: A Wall by Any Other Name |url=https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/2/23/the-dutch-the-english-part-2-a-wall-by-any-other-name |access-date=January 17, 2023 |website=NYC Department of Records & Information Services |date=February 23, 2017 |language=en-US |archive-date=January 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117190124/https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/2/23/the-dutch-the-english-part-2-a-wall-by-any-other-name |url-status=live }}</ref> This use of both names for the street also appears as late as 1691 on the Miller Plan of New York.<ref name="JS4oX">{{Cite web |title=The Dutch & the English Part 5: The Return of the Dutch and What Became of the Wall |url=https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/6/1/the-dutch-the-english-part-5-return-of-the-dutch-what-became-of-the-wall |access-date=January 17, 2023 |website=NYC Department of Records & Information Services |date=June 2017 |language=en-US |archive-date=January 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117190134/https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/6/1/the-dutch-the-english-part-5-return-of-the-dutch-what-became-of-the-wall |url-status=live }}</ref> New York Governor ] may have issued the first official designation of Wall Street in 1686, the same year he issued a new charter for New York. Confusion over the origins of the name Wall Street appeared in modern times because in the 19th and early 20th century some historians mistakenly thought the Dutch had called it "de Waal Straat", which to Dutch ears sounds like ] Street. However, in 17th century New Amsterdam, de Waal Straat (Wharf or Dock Street) was a section of what is today's ].<ref name="DORIS2017" /> | |||

| In the 1640s, basic picket and plank fences denoted plots and residences in the colony.<ref name=Sullivan> Editor, Dr. James Sullivan, Online Edition by Holice, Deb & Pam. Retrieved August 20, 2006.</ref> Later, on behalf of the ], ], using both African slaves<ref name="White New Yorkers in Slave Times"> ]. Retrieved August 20, 2006. (PDF)</ref> and ], collaborated with the city government in the construction of a more substantial ], a strengthened {{convert|12|ft|m|0|sing=on}} wall.<ref Name=timeline> PBS Online. Retrieved 2011-08-08.</ref> In 1685 surveyors laid out Wall Street along the lines of the original stockade.<ref Name=timeline> 2006 NYSE Group, Inc. Retrieved August 1, 2006.</ref> The wall started at Pearl Street, which was the shoreline at that time, crossing the Indian path Broadway and ending at the other shoreline (today's Trinity Place), where it took a turn south and ran along the shore until it ended at the old fort. In these early days, local merchants and traders would gather at disparate spots to buy and sell shares and bonds, and over time divided themselves into two classes—auctioneers and dealers.<ref name=twsJanSb/> The ] was removed in 1699.<ref name = walloonswallets/> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| In the late 18th century, there was a ] tree at the foot of Wall Street under which ] and speculators would gather to trade securities.<ref name=twsJanN215a/> The benefit was being in close proximity to each other.<ref name=twsJanN215a/> In 1792, traders formalized their association with the ] which was the origin of the ].<ref> The Library of Congress. Retrieved 2011-08-08.</ref> The idea of the agreement was to make the market more "structured" and "without the manipulative auctions", with a commission structure.<ref name=twsJanSb/> Persons signing the agreement agreed to charge each other a standard commission rate; persons not signing could still participate but would be charged a higher commission for dealing.<ref name=twsJanSb/> | |||

| The original wall was constructed under orders from Director General of the ], ], at the start of the first ] soon after New Amsterdam was incorporated in 1653.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Dutch & the English, Part 1: Good Fences, a History of Wall Street |url=https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/2/9/the-dutch-the-english-part-1-good-fences-a-history-of-wall-street |access-date=January 17, 2023 |website=NYC Department of Records & Information Services |date=February 9, 2017 |language=en-US |archive-date=January 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117190133/https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/2/9/the-dutch-the-english-part-1-good-fences-a-history-of-wall-street |url-status=live }}</ref> Fearing an over land invasion of English troops from the colonies in ] (at the time ] was easily accessible by land because the ] had not been dug), he ordered a ditch and wooden ] to be constructed on the northern boundary of the New Amsterdam settlement.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Emery |first=David |date=January 15, 2019 |title=Was Wall Street Originally the Site of a 'Border Wall' Meant to Protect New Amsterdam? |url=https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/wall-street-border-wall/ |access-date=January 23, 2023 |website=Snopes |language=en |archive-date=January 23, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230123151816/https://www.snopes.com/fact-check/wall-street-border-wall/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The wall was built of dirt and {{convert|15|ft|adj=on}} wooden planks, measuring {{convert|2,340|ft}} long and {{convert|9|ft}} tall<ref name="History.com Wall Street Timeline">{{Cite web|title=Wall Street Timeline: From a Wooden Wall to a Symbol of Economic Power|url=https://www.history.com/topics/us-states/wall-street-timeline|access-date=September 6, 2020|website=HISTORY|date=January 3, 2019|language=en|archive-date=January 5, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210105105733/https://www.history.com/topics/us-states/wall-street-timeline|url-status=live}}</ref> and was built using the labor of both ] and white colonists.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100601234634/http://www.slaveryinnewyork.org/PDFs/White_New_Yorkers.pdf |date=June 1, 2010 }} ]. Retrieved August 20, 2006. (PDF)</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170327142743/http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/timeline/crash/ |date=March 27, 2017 }} PBS Online. Retrieved August 8, 2011.</ref> In fact Stuyvesant had ordered that "the citizens, without exception, shall work on the constructions… by immediately digging a ditch from the East River to the North River, 4 to 5 feet deep and 11 to 12 feet wide..." And that "the soldiers and other servants of the Company, together with the free Negroes, no one excepted, shall complete the work on the fort by constructing a breastwork, and the farmers are to be summoned to haul the sod."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Gehring |first=Charles |title=New York historical Manuscripts: Dutch. Volume V: Council minutes 1652-1654 |publisher=Genealogical Publ. |year=1983 |location=Baltimore |pages=69 |language=English}}</ref> | |||

| The first Anglo-Dutch War ended in 1654 without hostilities in New Amsterdam, but over time the "werken" (meaning the works or city fortifications) were reinforced and expanded to protect against potential incursions from ], pirates, and the English.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harari |first=Yuval Noah |url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/910498369 |title=Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind |publisher=Penguin Random House UK |year=2015 |isbn=978-0-09-959008-8 |location=London |pages=360–361 |translator-last=Harari |translator-first=Yuval Noah |oclc=910498369 |author-link=Yuval Noah Harari |translator-last2=Purcell |translator-first2=John |translator-last3=Watzman |translator-first3=Haim |translator-link=Yuval Noah Harari |translator-link3=Haim Watzman}}</ref> The English also expanded and improved the wall after their 1664 takeover (a cause of the ]), as did the Dutch from 1673 to 1674 when they briefly ] the city during the ], and by the late 1600s the wall encircled most of the city and had two large stone bastions on the northern side.<ref name="JS4oX" /> The Dutch named these bastions "Hollandia" and "Zeelandia" after the ships that carried their invasion force. The wall started at ] on Pearl Street, which was the shoreline at that time, crossed the Indian path that the Dutch called ''Heeren Wegh'', now called ], and ended at the other shoreline (today's Trinity Place), where it took a turn south and ran along the shore until it ended at the ]. There was a gate at Broadway (the "Land Gate") and another at Pearl Street, the "Water Gate."<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Dutch & the English, Part 3: Construction of the Wall (1653-1663) |url=https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/3/9/the-dutch-the-english-part-3-construction-of-the-wall-1653-1663 |access-date=January 19, 2023 |website=NYC Department of Records & Information Services |date=March 9, 2017 |language=en-US |archive-date=January 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119200633/https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/3/9/the-dutch-the-english-part-3-construction-of-the-wall-1653-1663 |url-status=live }}</ref> The wall and its fortifications were eventually removed in 1699—it had outlived its usefulness because the city had grown well beyond the wall. A new City Hall was built at Wall and ] in 1700 using the stones from the bastions as materials for the foundation.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Dutch & the English Part 5: The Return of the Dutch and What Became of the Wall |url=https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/6/1/the-dutch-the-english-part-5-return-of-the-dutch-what-became-of-the-wall |access-date=January 19, 2023 |website=NYC Department of Records & Information Services |date=June 2017 |language=en-US |archive-date=January 17, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230117190134/https://www.archives.nyc/blog/2017/6/1/the-dutch-the-english-part-5-return-of-the-dutch-what-became-of-the-wall |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1789, Wall Street was the scene of the United States' first presidential inauguration when ] took the oath of office on the balcony of ] on April 30, 1789. This was also the location of the passing of the ]. In the cemetery of Trinity Church, ], who was the first Treasury secretary and "architect of the early United States financial system," is buried.<ref name=twsJanO53a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Daniel Gross | |||

| |title= The Capital of Capital No More? | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times: Magazine'' | |||

| |date= October 14, 2007 | |||

| |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/14/magazine/14wallstreet-t.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

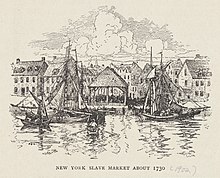

| ], located at the foot of Wall Street on the East River, {{circa|1730}}]] | |||

| ===Nineteenth century=== | |||

| In the first few decades, both residences and businesses occupied the area, but increasingly business predominated. "There are old stories of people's houses being surrounded by the clamor of business and trade and the owners complaining that they can't get anything done," according to a historian named Burrows.<ref name=twsJanN312a/> The opening of the ] in the early 19th century meant a huge boom in business for New York City, since it was the only major eastern seaport which had direct access by inland waterways to ports on the ]. Wall Street became the "money capital of America".<ref name=twsJanN215a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Noelle Knox and Martha T. Moor | |||

| |title= 'Wall Street' migrates to Midtown | |||

| |publisher= ''USA Today'' | |||

| |date= 2001-10-24 | |||

| |url= http://www.usatoday.com/news/sept11/2001/10/24/midtown.htm | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-14 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ] to Manhattan in 1626, but it was not until December 13, 1711, that the New York City Common Council made a market at the foot of Wall Street the city's first official ] for the sale and rental of enslaved Black people and Indians.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130306133627/http://maap.columbia.edu/place/22.html |date=March 6, 2013 }}. Mapping the African American Past, ].</ref><ref>Peter Alan Harper (February 5, 2013). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210131155200/https://www.theroot.com/how-slave-labor-made-new-york-1790895122 |date=January 31, 2021 }}. ''].'' Retrieved April 21, 2014.</ref> The market operated from 1711 to 1762 at the corner of Wall and Pearl Streets, and consisted of a wooden structure with a roof and open sides, although walls may have been added over the years; it could hold approximately 50 people. New York's municipal authorities directly benefited from the sale of slaves by implementing taxes on every person who was bought and sold there.<ref>WNYC (April 14, 2015). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201128195859/https://www.wnyc.org/story/nyc-acknowledge-its-slave-market-more-50-years/ |date=November 28, 2020 }}. ''].'' Retrieved April 15, 2015.</ref> | |||

| Historian Charles R. Geisst suggested that there has constantly been a "tug-of-war" between business interests on Wall Street and authorities in ].<ref name=twsJanSb>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Charles R. Geisst | |||

| |title= Wall Street: a history : from its beginnings to the fall of Enron | |||

| |publisher= ''Oxford University Press'' | |||

| |year= 1997 | |||

| |isbn= 0-19-511512-0 | |||

| |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=GDMmB3nEtL0C&printsec=frontcover&dq=geisst+wall+street+history+enron#v=onepage&q&f=false | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-19 | |||

| }}</ref> Generally during the 19th century Wall Street developed its own "unique personality and institutions" with little outside interference.<ref name=twsJanSb/> | |||

| In these early days, local merchants and traders would gather at disparate spots to buy and sell shares and bonds, and over time divided themselves into two classes—auctioneers and dealers.<ref name="Geisst1997" /> In the late 18th century, there was a ] tree at the foot of Wall Street under which traders and speculators would gather to trade securities. The benefit was being in proximity to each other.<ref name="usatoday20011024" /><ref name="History.com Wall Street Timeline" /> In 1792, traders formalized their association with the ] which was the origin of the ].<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060822201009/http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/today/jan04.html |date=August 22, 2006 }} The Library of Congress. Retrieved August 8, 2011.</ref> The idea of the agreement was to make the market more "structured" and "without the manipulative auctions", with a commission structure.<ref name="Geisst1997" /> Persons signing the agreement agreed to charge each other a standard commission rate; persons not signing could still participate but would be charged a higher commission for dealing.<ref name="Geisst1997" /> | |||

| In the 1840s and 1850s, most residents moved north to midtown because of the increased business use at the lower tip of the island.<ref name=twsJanN312a/> The Civil War had the effect of causing the northern economy to boom, bringing greater prosperity to cities like New York which "came into its own as the nation's banking center" connecting "Old World capital and New World ambition", according to one account.<ref name=twsJanO53a/> ] created giant trusts; ]’s ] moved to New York.<ref name=twsJanO53a/> Between 1860 and 1920, the economy changed from "agricultural to industrial to financial" and New York maintained its leadership position despite these changes, according to historian Thomas Kessner.<ref name=twsJanO53a/> New York was second only to London as the world's financial capital.<ref name=twsJanO53a/> | |||

| ]'s inauguration, 1789]] | |||

| In 1789, Wall Street was the scene of the United States' first presidential inauguration when ] took the oath of office on the balcony of ] on April 30, 1789. This was also the location of the passing of the ]. ], who was the first Treasury secretary and "architect of the early United States financial system", is buried in the cemetery of ], as is ] famed for his ]s.<ref name="nyt20071014">{{cite news |author-link=Daniel Gross (journalist) |first=Daniel |last=Gross |title=The Capital of Capital No More? |work=The New York Times: Magazine |date=October 14, 2007 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/14/magazine/14wallstreet-t.html |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=November 9, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109025255/http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/14/magazine/14wallstreet-t.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230318095609/https://www.nytimes.com/1863/12/23/archives/a-monument-to-robert-fulton.html |date=March 18, 2023 }} ''New York Times'', December 12, 1863</ref> | |||

| ===19th century=== | |||

| In 1884, ] began tracking stocks, initially beginning with 11 stocks, mostly railroads, and looked at average prices for these eleven.<ref name=twsJanSa>{{cite news | |||

| ].]] | |||

| |title= Description - Dow Jones Industrial Average Index | |||

| |publisher= ''MarketVolume'' | |||

| |date= 2010-01-19 | |||

| |url= http://www.marketvolume.com/indexes_exchanges/dji_description.asp | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-19 | |||

| }}</ref> When the average "peaks and troughs" went up consistently, he deemed it a bull market condition; if averages dropped, it was a bear market.<ref name=twsJanSa/> He added up prices, and divided by the number of stocks to get his Dow Jones average. Dow's numbers were a "convenient benchmark" for analyzing the market and became an accepted way to look at the entire stock market.<ref name=twsJanSa/> | |||

| In the first few decades, both residences and businesses occupied the area, but increasingly business predominated. "There are old stories of people's houses being surrounded by the clamor of business and trade and the owners complaining that they can't get anything done," according to a historian named Burrows.<ref name="nyt20010909">{{cite news|url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D0DE2DA1339F93AA3575AC0A9679C8B63|title=If You're Thinking of Living In/The Financial District; In Wall Street's Canyons, Cliff Dwellers|first=Aaron|last=Donovan|date=September 9, 2001|access-date=January 14, 2010|work=The New York Times: Real Estate|archive-date=January 8, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210108093054/https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/09/realestate/if-you-re-thinking-living-financial-district-wall-street-s-canyons-cliff.html|url-status=live}}</ref> The opening of the ] in the early 19th century meant a huge boom in business for New York City, since it was the only major eastern seaport which had direct access by inland waterways to ports on the ]. Wall Street became the "money capital of America".<ref name="usatoday20011024">{{cite news |first1=Noelle |last1=Knox |first2=Martha T. |last2=Moor |title='Wall Street' migrates to Midtown |newspaper=USA Today |date=October 24, 2001 |url=https://www.usatoday.com/news/sept11/2001/10/24/midtown.htm |access-date=January 14, 2010 |archive-date=September 27, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110927204946/http://www.usatoday.com/news/sept11/2001/10/24/midtown.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| In 1889, the original stock report, ''Customers' Afternoon Letter'', became '']''. Named in reference to the actual street, it became an influential international daily business newspaper published in ].<ref> 2006 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved August 19, 2006.</ref> After October 7, 1896, it began publishing Dow's expanded list of stocks.<ref name=twsJanSa/> A century later, there were 30 stocks in the average. | |||

| Historian Charles R. Geisst suggested that there has constantly been a "tug-of-war" between business interests on Wall Street and authorities in ], the capital of the United States by then.<ref name="Geisst1997">{{cite news |first=Charles R. |last=Geisst |title=Wall Street: a history : from its beginnings to the fall of Enron |publisher=Oxford University Press |year=1997 |isbn=0-19-511512-0 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GDMmB3nEtL0C&q=geisst+wall+street+history+enron |access-date=January 19, 2010}}</ref> Generally during the 19th century Wall Street developed its own "unique personality and institutions" with little outside interference.<ref name="Geisst1997" /> | |||

| ===Twentieth century=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Historian ] in his book ''Once in Golconda'' considered the turn of the 20th century period to have been Wall Street's ''heyday''.<ref name=twsJanO53a/> The address of 23 Wall Street where the headquarters of ], known as ''The Corner'', was "the precise center, geographical as well as metaphorical, of financial America and even of the financial world."<ref name=twsJanO53a/> | |||

| In the 1840s and 1850s, most residents moved further uptown to ] because of the increased business use at the lower tip of the island.<ref name="nyt20010909" /> The ] greatly expanded the northern economy, bringing greater prosperity to cities like New York which "came into its own as the nation's banking center" connecting "Old World capital and New World ambition", according to one account.<ref name="nyt20071014" /> ] created giant trusts and ]'s ] moved to New York City.<ref name="nyt20071014" /> Between 1860 and 1920, the economy changed from "agricultural to industrial to financial" and New York maintained its leadership position despite these changes, according to historian Thomas Kessner.<ref name="nyt20071014" /> New York was second only to ] as the world's financial capital.<ref name="nyt20071014" /> | |||

| In 1884, ] began tracking stocks, initially beginning with 11 stocks, mostly railroads. He looked at average prices for these eleven.<ref name="sether">{{cite book |title=Dow Theory Unplugged: Charles Dow's Original Editorials and Their Relevance |first=Charles |last=Dow|editor=Laura Sether |publisher=W&A Publishing |date=March 30, 2009 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=0_0c6ETLK7EC&pg=PA2 |page=2 |isbn=978-1934354094}}</ref> Some of the companies included in Dow's original calculations were ], ], ], ], ], and ].<ref name="loc.gov">{{Cite web|title=DJIA: This Month in Business History (Business Reference Services, Library of Congress)|url=https://www.loc.gov/rr/business/businesshistory/May/djia.html|access-date=November 17, 2020|website=www.loc.gov|archive-date=October 25, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201025115925/https://www.loc.gov/rr/business/businesshistory/May/djia.html|url-status=live}}</ref> When the average "peaks and troughs" went up consistently, he deemed it a ] condition; if averages dropped, it was a ]. He added up prices, and divided by the number of stocks to get his ]. Dow's numbers were a "convenient benchmark" for analyzing the market and became an accepted way to look at the entire ]. In 1889 the original stock report, ''Customers' Afternoon Letter'', became '']''. Named in reference to the actual street, it became an influential international daily business newspaper published in New York City.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20061114143257/http://www.dowjones.com/TheCompany/History/History.htm |date=November 14, 2006 }} 2006 Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved August 19, 2006.</ref> After October 7, 1896, it began publishing Dow's expanded list of stocks.<ref name="sether" /> A century later, there were 30 stocks in the average.<ref name="loc.gov" /> | |||

| Wall Street has had changing relationships with government authorities. In 1913, for example, when authorities proposed a $4 tax on stock transfers, stock clerks protested.<ref name=twsJanN213>{{cite news | |||

| |title= WALL STREET CLERKS FIGHT NEW STOCK TAX; Employes in Financial District, Including Waiters and Elevator Men, Enlisted in Movement. | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= March 6, 1913 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F40810FE3C5B13738DDDAF0894DB405B838DF1D3 | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-14 | |||

| }}</ref> At other times, city and state officials have taken steps through tax incentives to encourage financial firms to continue to do business in the city. | |||

| {{Further|Tumbridge & Co.}} | |||

| In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the ] of New York was a primary center for the construction of ]s, and was rivaled only by ] on the American continent. There were also residential sections, such as the Bowling Green section between Broadway and the ], and between ] and the Battery. The ] area was described as "Wall Street's ]" with poor people, high ] rates, and the "worst housing conditions in the city."<ref name=twsJanN412>{{cite news | |||

| |title= TO CLEAR BACK YARD OF WALL ST. DISTRICT; Bowling Green Neighborhood Association Reports Progress in Lower Manhattan. CITY OFFICIALS GIVE AID Work Said to be Experiment Offering Great Promise for a Community Plan. | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= May 14, 1916 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F10A16FA3F5D17738DDDAD0994DD405B868DF1D3 | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-14 | |||

| }}</ref> As a result of the construction, looking at New York City from the east, one can see two distinct clumps of tall buildings—the financial district on the left, and the taller ] district on the right. The ] of Manhattan is well-suited for tall buildings, with a solid mass of ] underneath Manhattan providing a firm foundation for tall buildings. Skyscrapers are expensive to build, but when there is a "short supply of land" in a "desirable location", then building upwards makes sound financial sense.<ref name=twsJanO44>{{cite news | |||

| |title= Better than flying: Despite the attack on the twin towers, plenty of skyscrapers are rising. They are taller and more daring than ever, but still mostly monuments to magnificence | |||

| |publisher= ''The Economist'' | |||

| |date= Jun 1st 2006 | |||

| |url= http://www.economist.com/node/7001496 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> A post office was built at ] in 1905.<ref name=twsJanO27>{{cite news | |||

| |title= WALL STREET P.O. BRANCH.; Postmaster General Yields to Request of Financial District. | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= March 14, 1905 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70A1EFA3A5F13718DDDAD0994DB405B858CF1D3 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> During the ] years, occasionally there were fund-raising efforts for projects such as the National Guard.<ref name=twsJanO14>{{cite news | |||

| |title= SHOW GIRLS MAKE WALL STREET RAID; They Invade Financial District and Sell Tickets for Soldiers' Relief. BROKERS HARD TO CATCH Party Welcomed at Morgan Offices, but No Sales Were Made There. | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= July 27, 1916 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F70617F63C5F13738DDDAE0A94DF405B868DF1D3 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ===20th century=== | |||

| On September 16, 1920, close to the corner of Wall and Broad Street, the busiest corner of the financial district and across the offices of the ], a ]. It killed 38 and seriously injured 143 people.<ref>Beverly Gage, ''The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in its First Age of Terror.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2009; pp. 160-161.</ref> The perpetrators were never identified or apprehended. The explosion did, however, help fuel the ] that was underway at the time. A report from the '']'': | |||

| ==== Early part ==== | |||

| ] | |||

| Business writer ] in his book ''Once in Golconda'' considered the start of the 20th century period to have been Wall Street's heyday.<ref name="nyt20071014" /> The address of ], the headquarters of ], known as ''The Corner'', was "the precise center, geographical as well as metaphorical, of financial America and even of the financial world".<ref name="nyt20071014" /> | |||

| {{cquote|The tomb-like silence that settles over Wall Street and lower Broadway with the coming of night and the suspension of business was entirely changed last night as hundreds of men worked under the glare of searchlights to repair the damage to skyscrapers that were lighted up from top to bottom. ... The Assay Office, nearest the point of explosion, naturally suffered the most. The front was pierced in fifty places where the cast iron slugs, which were of the material used for window weights, were thrown against it. Each slug penetrated the stone an inch or two and chipped off pieces ranging from three inches to a foot in diameter. The ornamental iron grill work protecting each window was broken or shattered. ... the Assay Office was a wreck. ... It was as though some gigantic force had overturned the building and then placed it upright again, leaving the framework uninjured but scrambling everything inside. -- 1920<ref name=twsJanN512>{{cite news | |||

| |title= WALL STREET NIGHT TURNED INTO DAY | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= September 17, 1920 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00914F7355511738DDDAE0994D1405B808EF1D3 | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-14 | |||

| }}</ref>}} | |||

| Wall Street has had changing relationships with government authorities. In 1913, for example, when authorities proposed a $4 stock ], stock clerks protested.<ref>{{cite news |title=WALL STREET CLERKS FIGHT NEW STOCK TAX; Employes in Financial District, Including Waiters and Elevator Men, Enlisted in Movement. |newspaper=The New York Times |date=March 6, 1913 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1913/03/06/archives/wall-street-clerks-fight-new-stock-tax-employes-in-financial.html |access-date=January 14, 2010 |archive-date=October 24, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201024192553/https://www.nytimes.com/1913/03/06/archives/wall-street-clerks-fight-new-stock-tax-employes-in-financial.html |url-status=live }}</ref> At other times, city and state officials have taken steps through tax incentives to encourage financial firms to continue to do business in the city. A post office was built at ] in 1905.<ref>{{cite news |title=WALL STREET P.O. BRANCH.; Postmaster General Yields to Request of Financial District. |newspaper=The New York Times |date=March 14, 1905 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1905/03/14/archives/wall-street-po-branch-postmaster-general-yields-to-request-of.html |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=July 26, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180726103800/https://www.nytimes.com/1905/03/14/archives/wall-street-po-branch-postmaster-general-yields-to-request-of.html |url-status=live }}</ref> During the ] years, occasionally there were fund-raising efforts for projects such as the ].<ref>{{cite news |title=SHOW GIRLS MAKE WALL STREET RAID; They Invade Financial District and Sell Tickets for Soldiers' Relief. BROKERS HARD TO CATCH Party Welcomed at Morgan Offices, but No Sales Were Made There. |newspaper=The New York Times |date=July 27, 1916 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1916/07/27/archives/show-girls-make-wall-street-raid-they-invade-financial-district-and.html |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=July 26, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180726103825/https://www.nytimes.com/1916/07/27/archives/show-girls-make-wall-street-raid-they-invade-financial-district-and.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The area was subjected to numerous threats; one bomb threat in 1921 led to detectives sealing off the area to "prevent a repetition of the Wall Street bomb explosion."<ref name=twsJanO16>{{cite news | |||

| |title= DETECTIVES GUARD WALL ST. AGAINST NEW BOMB OUTRAGE; Entire Financial District Patrolled Following AnonymousWarning to a Broker | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= December 19, 1921 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=FA0A10FB3A5A1B7A93CBA81789D95F458285F9 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ] is on the right. The majority of people are congregating in Wall Street on the left between the "House of Morgan" (]) and ] (26 Wall Street).]] | |||

| On September 16, 1920, close to the corner of Wall and ], the busiest corner of the Financial District and across the offices of the ], a ]. It killed 38 and seriously injured 143 people.<ref>Beverly Gage, ''The Day Wall Street Exploded: A Story of America in its First Age of Terror.'' New York: Oxford University Press, 2009; pp. 160-161.</ref> The perpetrators were never identified or apprehended. The explosion did, however, help fuel the ] that was underway at the time. A report from '']'': | |||

| === Regulation === | |||

| In October 1929, a celebrated ] ] named Irving Fisher reassured worried investors that their "money was safe" on Wall Street.<ref name=twsJanO15a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Larry Elliott (reviewer) Steve Fraser (author) (book:) Wall Street: A cultural History (by Fraser) | |||

| |title= Going for brokers: Steve Fraser charts the highs and the lows of the world's financial capital in Wall Stree | |||

| |publisher= ''The Guardian'' | |||

| |date= 21 May 2005 | |||

| |url= http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2005/may/21/featuresreviews.guardianreview11 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> A few days later, stock values plummeted. The ] ushered in the ] in which a quarter of working people were unemployed, with soup kitchens, mass foreclosures of farms, and falling prices.<ref name=twsJanO15a/> During this era, development of the financial district stagnated, and Wall Street "paid a heavy price" and "became something of a backwater in American life."<ref name=twsJanO15a/> During the ] years as well as the forties, there was much less focus on Wall Street and finance. The government clamped down on the practice of buying equities based only on credit, but these policies began to ease. From 1946-1947, stocks could not be purchased "]", meaning that an investor had to pay 100% of a stock's cost without taking on any loans.<ref name=twsJanO41a/> But this margin requirement was reduced four times before 1960, each time stimulating a mini-rally and boosting volume, and when the Federal Reserve reduced the margin requirements from 90% to 70%.<ref name=twsJanO41a/> These changes made it somewhat easier for investors to buy stocks on credit.<ref name=twsJanO41a>{{cite news | |||

| |title= STOCK MARKET MARGINS: The Federal Reserve v. Wall Street | |||

| |publisher= ''Time Magazine'' | |||

| |date= Aug. 08, 1960 | |||

| |url= http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,869769,00.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> The growing national economy and prosperity led to a recovery during the sixties, with some down years during the early seventies in the aftermath of the ]. Trading volumes climbed; in 1967, according to '']'', volume hit 7.5 million shares a day which caused a "traffic jam" of paper with "batteries of clerks" working overtime to "clear transactions and update customer accounts."<ref name=twsJanO28>{{cite news | |||

| |title= Wall Street: Bob Cratchit Hours | |||

| |publisher= ''Time Magazine'' | |||

| |date= Aug. 18, 1967 | |||

| |url= http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,841001,00.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|The tomb-like silence that settles over Wall Street and lower Broadway with the coming of night and the suspension of business was entirely changed last night as hundreds of men worked under the glare of searchlights to repair the damage to skyscrapers that were lighted up from top to bottom. ... The Assay Office, nearest the point of explosion, naturally suffered the most. The front was pierced in fifty places where the cast iron slugs, which were of the material used for window weights, were thrown against it. Each slug penetrated the stone an inch or two and chipped off pieces ranging from three inches to a foot in diameter. The ornamental iron grill work protecting each window was broken or shattered. ... the Assay Office was a wreck. ... It was as though some gigantic force had overturned the building and then placed it upright again, leaving the framework uninjured but scrambling everything inside.|1920<ref>{{cite news |title=Wall Street Night Turned Into Day |url-access=subscription |newspaper=The New York Times |date=September 17, 1920 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1920/09/17/archives/wall-street-night-turned-into-day-huge-throngs-jam-financial.html |access-date=January 14, 2010 |archive-date=January 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210108094614/https://www.nytimes.com/1920/09/17/archives/wall-street-night-turned-into-day-huge-throngs-jam-financial.html |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| In 1973, the financial community posted a collective loss of $245 million and needed help, and got it with the form of temporary help from the goverrnment.<ref name="twsJanO32a">{{cite news | |||

| |title= WALL STREET: Help for Broke Brokers | |||

| |publisher= ''Time Magazine'' | |||

| |date= Sep. 24, 1973 | |||

| |url= http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,907961,00.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> Reforms happened; the SEC eliminated fixed commissions which forced "brokers to compete freely with one another for investors' business."<ref name="twsJanO32a"/> In 1975, the Securities & Exchange Commission threw out the NYSE's "Rule 394" which had required that "most stock transactions take place on the Big Board's floor", in effect freeing up trading for electronic methods.<ref name=twsJanO31>{{cite news | |||

| |title= WALL STREET: Banks As Brokers | |||

| |publisher= ''Time Magazine'' | |||

| |date= Aug. 30, 1976 | |||

| |url= http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,918271,00.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> In 1976, banks were allowed to buy and sell stocks, which provided more competition for stockbrokers.<ref name=twsJanO31/> Reforms had the effect of lowering prices overall, making it easier for more people to participate in the stock market.<ref name=twsJanO31/> Broker commissions for each stock sale lessened, but volume increased.<ref name="twsJanO32a"/> | |||

| The area was subjected to numerous threats; one bomb threat in 1921 led to detectives sealing off the area to "prevent a repetition of the Wall Street bomb explosion".<ref>{{cite news |title=DETECTIVES GUARD WALL ST. AGAINST NEW BOMB OUTRAGE; Entire Financial District Patrolled Following AnonymousWarning to a Broker |newspaper=The New York Times |date=December 19, 1921 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1921/12/19/archives/detectives-guard-wall-st-against-new-bomb-outrage-entire-financial.html |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=October 30, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030055444/https://www.nytimes.com/1921/12/19/archives/detectives-guard-wall-st-against-new-bomb-outrage-entire-financial.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The ] were marked by a renewed push for ], ], with national efforts to de-regulate industries such as ] and ]. The economy resumed upward growth after a period in the early eighties of languishing. A report in the '']'' described that the flushness of money and growth during these years had spawned a drug culture of sorts, with a rampant acceptance of cocaine use although the overall percent of actual users was most likely small. A reporter wrote: | |||

| ====Regulation==== | |||

| {{cquote|The Wall Street drug dealer looked like many other successful young female executives. Stylishly dressed and wearing designer sunglasses, she sat in her 1983 Chevrolet Camaro in a no-parking zone across the street from the Marine Midland Bank branch on lower Broadway. The customer in the passenger seat looked like a successful young businessman. But as the dealer slipped him a heat-sealed plastic envelope of cocaine and he passed her cash, the transaction was being watched through the sunroof of her car by Federal drug agents in a nearby building. And the customer - an undercover agent himself -was learning the ways, the wiles and the conventions of Wall Street's drug subculture. -- Peter Kerr in the '']'', 1987.<ref name=twsJanO22>{{cite news | |||

| ] on the right. The majority of people are congregating in Wall Street on the left between the "House of Morgan" (]) and ] (26 Wall Street).]] | |||

| |author= Peter Kerr | |||

| September 1929 was the peak of the stock market.<ref name="The world in depression 1929–1939">The world in depression 1929–1939</ref> October 3, 1929, was when the market started to slip, and it continued throughout the week of October 14.<ref name="The world in depression 1929–1939" /> | |||

| |title= AGENTS TELL OF DRUG'S GRIP ON WALL STREET | |||

| In October 1929, renowned ] economist ] reassured worried investors that their "money was safe" on Wall Street.<ref name="guardian20050521">{{cite news |first=Larry |last=Elliott |title=Going for Brokers |newspaper=The Guardian |date=May 21, 2005 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/may/21/featuresreviews.guardianreview11 |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=October 28, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201028092343/https://www.theguardian.com/books/2005/may/21/featuresreviews.guardianreview11 |url-status=live }}</ref> A few days later, on October 24,<ref name="The world in depression 1929–1939" /> stock values plummeted. The ] ushered in the ], in which a quarter of working people were unemployed, with soup kitchens, mass foreclosures of farms, and falling prices.<ref name="guardian20050521" /> During this era, development of the Financial District stagnated, and Wall Street "paid a heavy price" and "became something of a backwater in American life".<ref name="guardian20050521" /> | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= April 18, 1987 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1DC153CF93BA25757C0A961948260 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref>}} | |||

| During the ] years, as well as the 1940s, there was much less focus on Wall Street and finance. The government clamped down on the practice of buying equities based only on credit, but these policies began to ease. From 1946 to 1947, stocks could not be purchased "]", meaning that an investor had to pay 100% of a stock's cost without taking on any loans.<ref name="time19600808" /> However, this margin requirement was reduced four times before 1960, each time stimulating a mini-rally and boosting volume, and when the ] reduced the margin requirements from 90% to 70%.<ref name="time19600808" /> These changes made it somewhat easier for investors to buy stocks on credit.<ref name="time19600808">{{cite magazine |title=STOCK MARKET MARGINS: The Federal Reserve v. Wall Street |magazine=Time Magazine |date=August 8, 1960 |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,869769,00.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071022231011/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,869769,00.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=October 22, 2007 |access-date=January 15, 2011}}</ref> The growing national economy and prosperity led to a recovery during the 1960s, with some down years during the early 1970s in the aftermath of the ]. Trading volumes climbed; in 1967, according to '']'', volume hit 7.5 million shares a day which caused a "traffic jam" of paper with "batteries of clerks" working overtime to "clear transactions and update customer accounts".<ref>{{cite magazine |title=Wall Street: Bob Cratchit Hours |magazine=Time Magazine |date=August 18, 1967 |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,841001,00.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081215152500/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,841001,00.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=December 15, 2008 |access-date=January 15, 2011}}</ref> | |||

| In 1987, the stock market plunged<ref name=twsJanN215a/> and, in the relatively brief recession following, lower Manhattan lost 100,000 jobs according to one estimate.<ref name=twsJanN211/> Since telecommunications costs were coming down, banks and brokerage firms could move away from Wall Street to more affordable locations.<ref name=twsJanN211/> The recession of 1990–1991 were marked by office vacancy rates downtown which were "persistently high" and with some buildings "standing empty."<ref name=twsJanN312a/> The day of the drop, October 20, was marked by "stony-faced traders whose sense of humor had abandoned them and in the exhaustion of stock exchange employees struggling to maintain orderly trading."<ref name=twsJanN312>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Alison Leigh Cowan | |||

| |title= THE MARKET PLUNGE; Day to Remember In Financial District | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= October 20, 1987 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE6DC1630F933A15753C1A961948260 | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-14 | |||

| }}</ref> Ironically, it was the same year that Oliver Stone's movie '']'' appeared. In 1995, city authorities offered the ''Lower Manhattan Revitalization Plan'' which offered incentives to convert commercial properties to residential use.<ref name=twsJanN312a/> | |||

| In 1973, the financial community posted a collective loss of $245 million, which spurred temporary help from the government.<ref name="time19730924">{{cite magazine |title=WALL STREET: Help for Broke Brokers |magazine=Time Magazine |date=September 24, 1973 |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,907961,00.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20081018211248/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,907961,00.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=October 18, 2008 |access-date=January 15, 2011}}</ref> Reforms were instituted; the ] eliminated fixed commissions, which forced "brokers to compete freely with one another for investors' business".<ref name="time19730924" /> In 1975, the SEC threw out the ]'s "Rule 394" which had required that "most stock transactions take place on the Big Board's floor", in effect freeing up trading for electronic methods.<ref name="time19760830">{{cite magazine |title=WALL STREET: Banks As Brokers |magazine=Time Magazine |date=August 30, 1976 |url=http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,918271,00.html |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050111223136/http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,918271,00.html |url-status=dead |archive-date=January 11, 2005 |access-date=January 15, 2011}}</ref> In 1976, banks were allowed to buy and sell stocks, which provided more competition for ]s.<ref name="time19760830" /> Reforms had the effect of lowering prices overall, making it easier for more people to participate in the stock market.<ref name="time19760830" /> Broker commissions for each stock sale lessened, but volume increased.<ref name="time19730924" /> | |||

| Construction of the ] began in 1966 but had trouble attracting tenants when completed. Nonetheless, some substantial firms purchased space there. It's impressive height helped make it a visual landmark for drivers and pedestrians. In some respects, the nexus of the financial district moved from the ''street'' of Wall Street to Trade Center complex. Real estate growth during the latter part of the 1990s was significant, with deals and new projects happening in the financial district and elsewhere in Manhattan; one firm invested more than $24 billion in various projects, many in the Wall Street area.<ref name=twsJanO24>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Laura M. Holson and Charles V. Bagli | |||

| |title= Lending Without a Net; With Wall Street as Its Banker, Real Estate Feels the World's Woes | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= November 1, 1998 | |||

| |url= http://www.nytimes.com/1998/11/01/business/lending-without-net-with-wall-street-its-banker-real-estate-feels-world-s-woes.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> In 1998, the NYSE and the city struck a $900 million deal which kept the NYSE from moving across the river to ]; the deal was described as the "largest in city history to prevent a corporation from leaving town".<ref name=twsJanO34>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Charles V. Bagli | |||

| |title= City and State Agree to $900 Million Deal to Keep New York Stock Exchange | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= December 23, 1998 | |||

| |url= http://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/23/nyregion/city-and-state-agree-to-900-million-deal-to-keep-new-york-stock-exchange.html?src=pm | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> A competitor to the NYSE, ], moved its headquarters from Washington to New York.<ref name=twsJanO36a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Charles V. Bagli | |||

| |title= N.A.S.D. Ponders Move to New York City | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= May 7, 1998 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9D04E1DE1531F934A35756C0A96E958260 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| The ] were marked by a renewed push for ] and ], with national efforts to de-regulate industries such as ] and ]. The economy resumed upward growth after a period in the early 1980s of languishing. A report in '']'' described that the flushness of money and growth during these years had spawned a ] of sorts, with a rampant acceptance of ] use although the overall percent of actual users was most likely small. A reporter wrote: | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] is at the lower middle slight right.]] | |||

| {{blockquote|The Wall Street drug dealer looked like many other successful young female executives. Stylishly dressed and wearing designer sunglasses, she sat in her 1983 Chevrolet Camaro in a no-parking zone across the street from the ] on lower Broadway. The customer in the passenger seat looked like a successful young businessman. But as the dealer slipped him a heat-sealed plastic envelope of cocaine and he passed her cash, the transaction was being watched through the sunroof of her car by Federal drug agents in a nearby building. And the customer — an undercover agent himself -was learning the ways, the wiles and the conventions of Wall Street's drug subculture.|Peter Kerr in '']'', 1987.<ref>{{cite news |first=Peter |last=Kerr |title=AGENTS TELL OF DRUG'S GRIP ON WALL STREET |newspaper=The New York Times |date=April 18, 1987 |url=https://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE1DC153CF93BA25757C0A961948260 |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=January 8, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210108122103/https://www.nytimes.com/1987/04/18/nyregion/agents-tell-of-drug-s-grip-on-wall-street.html |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | |||

| ===Twenty-first century=== | |||

| In the first year of the new century, the ''Big Board'', as some termed the NYSE, was described as the world's "largest and most prestigious stock market."<ref name=twsJanO35a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Alex Berenson | |||

| |title= A NATION CHALLENGED: THE EXCHANGE; Feeling Vulnerable At Heart of Wall St. | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times: Business Day'' | |||

| |date= October 12, 2001 | |||

| |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/12/business/a-nation-challenged-the-exchange-feeling-vulnerable-at-heart-of-wall-st.html?src=pm | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> But when the World Trade Center was destroyed on ], it left an architectural void as new developments since the 1970s had played off the complex aesthetically. The attacks "crippled" the communications network.<ref name=twsJanO35a/> One estimate was that 45% of Wall Street's "best office space" had been lost.<ref name=twsJanN215a/> The physical destruction was immense: | |||

| ], at Wall Street and Broadway]] | |||

| {{cquote|Debris littered some streets of the financial district. National Guard members in camouflage uniforms manned checkpoints. Abandoned coffee carts, glazed with dust from the collapse of the World Trade Center, lay on their sides across sidewalks. Most subway stations were closed, most lights were still off, most telephones did not work, and only a handful of people walked in the narrow canyons of Wall Street yesterday morning. -- Leslie Eaton and Kirk Johnson of the '']'', September 16, 2001.<ref name=twsJanO18a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Leslie Eaton and Kirk Johnson | |||

| |title= AFTER THE ATTACKS: WALL STREET; STRAINING TO RING THE OPENING BELL -- AFTER THE ATTACKS: WALL STREET | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= September 16, 2001 | |||

| |url= http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A03E2D7163BF935A2575AC0A9679C8B63&pagewanted=all | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref>}} | |||

| In 1987, the stock market plunged,<ref name="usatoday20011024" /> and, in the relatively brief recession following, the surrounding area lost 100,000 jobs according to one estimate.<ref name="nyt19960128">{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1996/01/28/nyregion/new-yorkers-ghosts-teapot-dome-fabled-wall-street-offices-are-now-apartments-but.html|title=NEW YORKERS & CO.: The Ghosts of Teapot Dome;Fabled Wall Street Offices Are Now Apartments, but Do Not Yet a Neighborhood Make|first=Michael|last=Cooper|date=January 28, 1996|newspaper=The New York Times|access-date=January 14, 2010|archive-date=October 28, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201028135150/https://www.nytimes.com/1996/01/28/nyregion/new-yorkers-ghosts-teapot-dome-fabled-wall-street-offices-are-now-apartments-but.html|url-status=live}}</ref> Since telecommunications costs were coming down, banks and ]s could move away from the Financial District to more affordable locations.<ref name="nyt19960128" /> One of the firms looking to move away was the NYSE. In 1998, the NYSE and the city struck a $900 million deal which kept the NYSE from moving across the river to ]; the deal was described as the "largest in city history to prevent a corporation from leaving town".<ref>{{cite news |first=Charles V. |last=Bagli |title=City and State Agree to $900 Million Deal to Keep New York Stock Exchange |newspaper=The New York Times |date=December 23, 1998 |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/23/nyregion/city-and-state-agree-to-900-million-deal-to-keep-new-york-stock-exchange.html?src=pm |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=May 18, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130518044139/http://www.nytimes.com/1998/12/23/nyregion/city-and-state-agree-to-900-million-deal-to-keep-new-york-stock-exchange.html?src=pm |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Still, the NYSE was determined to re-open on September 17, almost a week after the attack.<ref name=twsJanO18a/> The attack hastened a trend towards financial firms moving to midtown and contributed to the loss of business on Wall Street, due to temporary-to-permanent relocation to ] and further decentralization with establishments transferred to cities like ], ], and ]. | |||

| ===21st century=== | |||

| After September 11, the financial services industry went through a downturn with a sizable drop in year-end bonuses of $6.5 billion, according to one estimate from a state comptroller's office.<ref name=twsJanN214/> Many brokers are paid mostly through commission, and get a token annual salary which is dwarfed by the year-end bonus. | |||

| In 2001, the ''Big Board'', as some termed the NYSE, was described as the world's "largest and most prestigious stock market".<ref name="nyt20011012">{{Cite news|last=Berenson|first=Alex|date=October 12, 2001|title=A Nation Challenged: the Exchange; Feeling Vulnerable At Heart of Wall St.|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/12/business/a-nation-challenged-the-exchange-feeling-vulnerable-at-heart-of-wall-st.html|access-date=March 22, 2023|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=March 22, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230322204844/https://www.nytimes.com/2001/10/12/business/a-nation-challenged-the-exchange-feeling-vulnerable-at-heart-of-wall-st.html|url-status=live}}</ref> When the ] on ], the attacks "crippled" the communications network and destroyed many buildings in the Financial District, although the buildings on Wall Street itself saw only little physical damage.<ref name="nyt20011012" /> One estimate was that 45% of Wall Street's "best office space" had been lost.<ref name="usatoday20011024" /> The NYSE was determined to re-open on September 17, almost a week after the attack.<ref name="nyt20010916">{{Cite news|last1=Eaton|first1=Leslie|last2=Johnson|first2=Kirk|date=September 16, 2001|title=After the Attacks: Wall Street; Straining to Ring the Opening Bell|language=en-US|work=The New York Times|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/16/us/after-the-attacks-wall-street-straining-to-ring-the-opening-bell.html|access-date=March 22, 2023|issn=0362-4331|archive-date=January 25, 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210125201924/https://www.nytimes.com/2001/09/16/us/after-the-attacks-wall-street-straining-to-ring-the-opening-bell.html|url-status=live}}</ref> During this time ] opened additional offices at ]. Still, after September 11, the financial services industry went through a downturn with a sizable drop in year-end bonuses of $6.5 billion, according to one estimate from a state comptroller's office.<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/19/nyregion/neighborhood-report-lower-manhattan-at-job-lot-the-final-bargain-days.html|title=NEIGHBORHOOD REPORT: LOWER MANHATTAN; At Job Lot, the Final Bargain Days|first=Bruce|last=Lambert|date=December 19, 1993|newspaper=The New York Times|access-date=January 14, 2010|archive-date=January 24, 2011|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110124083124/http://www.nytimes.com/1993/12/19/nyregion/neighborhood-report-lower-manhattan-at-job-lot-the-final-bargain-days.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| To guard against a vehicular bombing in the area, authorities built concrete barriers, and found ways over time to make them more aesthetically appealing by spending $5000 to $8000 apiece on |

To guard against a vehicular bombing in the area, authorities built concrete barriers, and found ways over time to make them more aesthetically appealing by spending $5000 to $8000 apiece on ]s. Parts of Wall Street, as well as several other streets in the neighborhood, were blocked off by specially designed bollards: | ||

| {{ |

{{blockquote|... Rogers Marvel designed a new kind of bollard, a faceted piece of sculpture whose broad, slanting surfaces offer people a place to sit in contrast to the typical bollard, which is supremely unsittable. The bollard, which is called the Nogo, looks a bit like one of Frank Gehry's unorthodox culture palaces, but it is hardly insensitive to its surroundings. Its bronze surfaces actually echo the grand doorways of Wall Street's temples of commerce. Pedestrians easily slip through groups of them as they make their way onto Wall Street from the area around historic Trinity Church. Cars, however, cannot pass.|Blair Kamin in the '']'', 2006<ref>{{cite news |first=Blair |last=Kamin |title=How Wall Street became secure, and welcoming |newspaper=Chicago Tribune |date=September 9, 2006 |url=http://www.chicagotribune.com/chi-090806wallstreet-story,0,1233707.story |access-date=January 14, 2010 |archive-date=April 18, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140418084350/http://www.chicagotribune.com/chi-090806wallstreet-story,0,1233707.story |url-status=live }}</ref>}} | ||

| |author= Blair Kamin | |||

| |title= How Wall Street became secure, and welcoming | |||

| |publisher= ''Chicago Tribune'' | |||

| |date= September 9, 2006 | |||

| |url= http://www.chicagotribune.com/chi-090806wallstreet-story,0,1233707.story | |||

| |accessdate= 2010-01-14 | |||

| }}</ref>}} | |||

| '']'' reporter Andrew Clark described the years of 2006 to 2010 as "tumultuous", in which the heartland of America was "mired in gloom" with high unemployment around 9.6%, with average house prices falling from $230,000 in 2006 to $183,000, and foreboding increases in the national debt to $13.4 trillion, but that despite the setbacks, the American economy was once more "bouncing back".<ref name="guardian20101007">{{cite news |first=Andrew |last=Clark |title=Farewell to Wall Street: After four years as US business correspondent, Andrew Clark is heading home. He recalls the extraordinary events that nearly bankrupted America – and how it's bouncing back |newspaper=The Guardian |date=October 7, 2010 |url=https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/oct/07/farewell-to-wall-street-us-financial-crisis |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=November 9, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201109032919/http://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/oct/07/farewell-to-wall-street-us-financial-crisis |url-status=live }}</ref> What had happened during these heady years? Clark wrote: | |||

| Wall Street itself and the Financial District as a whole are crowded with highrises. Further, the loss of the World Trade Center has spurred development on a scale that hadn't been seen in decades. In 2006, Goldman Sachs began building a tower near the former Trade Center site.<ref name=twsJanO44/> Tax incentives provided by federal, state and local governments encouraged development. A new World Trade Center complex, centered on ]'s ] plan, is in the early stages of development and one building has already been replaced. The centerpiece to this plan is the {{convert|1776|ft|m|0|sing=on}} tall ] (formerly known as the Freedom Tower). New residential buildings are sprouting up, and buildings that were previously office space are being converted to residential units, also benefiting from tax incentives. A new ] is planned to improve access. In 2007, the ] opened headquarters at 70 Broad Street near the NYSE, in an effort to seek investors.<ref name=twsJanO17>{{cite news | |||

| |author= MARIA ASPAN | |||

| |title= Maharishi’s Minions Come to Wall Street | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |date= July 2, 2007 | |||

| |url= http://www.nytimes.com/2007/07/02/business/worldbusiness/02maharishi.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| {{blockquote|But the picture is too nuanced simply to dump all the responsibility on financiers. Most Wall Street banks didn't actually go around the US hawking dodgy mortgages; they bought and packaged loans from on-the-ground firms such as Countrywide Financial and New Century Financial, both of which hit a financial wall in the crisis. Foolishly and recklessly, the banks didn't look at these loans adequately, relying on flawed credit-rating agencies such as Standard & Poor's and Moody's, which blithely certified toxic mortgage-backed securities as solid ... A few of those on Wall Street, including maverick hedge fund manager John Paulson and the top brass at Goldman Sachs, spotted what was going on and ruthlessly gambled on a crash. They made a fortune but turned into the crisis's pantomime villains. Most, though, got burned – the banks are still gradually running down portfolios of non-core loans worth $800bn.|'']'' reporter Andrew Clark, 2010.<ref name="guardian20101007" />}} | |||

| '']'' reporter Andrew Clark described the years of 2006 to 2010 as "tumultous" in which the heartland of America is "mired in gloom" with high unemployment around 9.6%, with average house prices falling from $230,000 in 2006 to $183,000, and foreboding increases in the national debt to $13.4 trillion, but that despite the setbacks, the American economy was once more "bouncing back."<ref name=twsJanO12a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Andrew Clark | |||

| |title= Farewell to Wall Street: After four years as US business correspondent, Andrew Clark is heading home. He recalls the extraordinary events that nearly bankrupted America – and how it's bouncing back | |||

| |publisher= ''The Guardian'' | |||

| |date= 7 October 2010 | |||

| |url= http://www.guardian.co.uk/business/2010/oct/07/farewell-to-wall-street-us-financial-crisis | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> What had happened during these heady years? Clark wrote: | |||

| ] looking west on Wall Street]] | |||

| {{cquote|But the picture is too nuanced simply to dump all the responsibility on financiers. Most Wall Street banks didn't actually go around the US hawking dodgy mortgages; they bought and packaged loans from on-the-ground firms such as Countrywide Financial and New Century Financial, both of which hit a financial wall in the crisis. Foolishly and recklessly, the banks didn't look at these loans adequately, relying on flawed credit-rating agencies such as Standard & Poor's and Moody's, which blithely certified toxic mortgage-backed securities as solid... A few of those on Wall Street, including maverick hedge fund manager John Paulson and the top brass at Goldman Sachs, spotted what was going on and ruthlessly gambled on a crash. They made a fortune but turned into the crisis's pantomime villains. Most, though, got burned – the banks are still gradually running down portfolios of non-core loans worth $800bn. -- '']'' reporter Andrew Clark, 2010.<ref name=twsJanO12a/>}} | |||

| The first months of 2008 was a particularly troublesome period which caused ] chairman ] to "work holidays and weekends" and which did an "extraordinary series of moves".<ref name="npr20080317">{{cite news |first1=Steve |last1=Inskeep |first2=Jim |last2=Zarroli |title=Federal Reserve Bolsters Wall Street Banks |publisher=NPR |date=March 17, 2008 |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88379863 |access-date=January 15, 2011 |archive-date=October 28, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201028211740/https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88379863 |url-status=live }}</ref> It bolstered U.S. banks and allowed Wall Street firms to borrow "directly from the Fed"<ref name="npr20080317" /> through a vehicle called the Fed's Discount Window, a sort of lender of last resort.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Foster|first=Sarah|title=Fed's Discount Window: How Banks Borrow Money From The U.S. Central Bank|url=https://www.bankrate.com/banking/federal-reserve/discount-window-banks-borrow-from-fed/|access-date=September 6, 2020|website=Bankrate|date=September 30, 2019 |language=en-US|archive-date=November 12, 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201112020055/https://www.bankrate.com/banking/federal-reserve/discount-window-banks-borrow-from-fed/|url-status=live}}</ref> These efforts were highly controversial at the time, but from the perspective of 2010, it appeared the Federal exertions had been the right decisions. | |||

| The first months of 2008 was a particularly troublesome period which caused ] chairman ] to "work holidays and weekends" and which did an "extraordinary series of moves."<ref name=twsJanO37>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Steve Inskeep and Jim Zarroli | |||

| |title= Federal Reserve Bolsters Wall Street Banks | |||

| |publisher= ''NPR'' | |||

| |date= March 17, 2008 | |||

| |url= http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=88379863 | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> It bolstered U.S. banks and allowed Wall Street firms to borrow "directly from the Fed."<ref name=twsJanO37/> These efforts were highly controversial at the time, but from the perspective of 2010, it appeared the Federal exertions had been the right decisions. By 2010, Wall Street firms, in Clark's view, were "getting back to their old selves as engine rooms of wealth, prosperity and excess."<ref name=twsJanO12a/> A report by Michael Stoler in '']'' described a "phoenix-like resurrection" of the area, with residential, commercial, retail and hotels booming in the "third largest business district in the country."<ref name=twsJanO19a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Michael Stoler | |||

| |title= Refashioned: Financial District Is Booming With Business | |||

| |publisher= ''New York Sun'' | |||

| |date= June 28, 2007 | |||

| |url= http://www.nysun.com/real-estate/refashioned-financial-district-is-booming-with/57476/ | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> At the same time, the investment community was worried about proposed legal reforms, including the ''Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act'' which dealt with matters such as credit card rates and lending requirements.<ref name=twsJanO42>{{cite news | |||

| |author= Jill Jackson | |||

| |title= Wall Street Reform: A Summary of What's In the Bill | |||

| |publisher= ''CBS News'' | |||

| |date= June 25, 2010 | |||

| |url= http://www.cbsnews.com/8301-503544_162-20008835-503544.html | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-01-15 | |||

| }}</ref> The NYSE closed two of its trading floors in a move towards transforming itself into an electronic exchange.<ref name=twsJanO53a/> In September 2011, protesters disenchanted with the financial system protested in parks and plazas in lower Manhattan.<ref name=twsP44f545a>{{cite news | |||

| |author= COLIN MOYNIHAN | |||

| |title= Wall Street Protest Begins, With Demonstrators Blocked | |||

| |publisher= ''The New York Times'' | |||

| |quote= Throughout the afternoon hundreds of demonstrators gathered in parks and plazas in Lower Manhattan. They held teach-ins, engaged in discussion and debate and waved signs with messages like “Democracy Not Corporatization” or “Revoke Corporate Personhood.” | |||

| |date= September 17, 2011 | |||

| |url= http://cityroom.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/09/17/wall-street-protest-begins-with-demonstrators-blocked/ | |||

| |accessdate= 2011-09-16 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||