| Revision as of 07:17, 4 August 2002 edit217.168.172.203 (talk)mNo edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:56, 9 September 2024 edit undo75.168.116.41 (talk) →History - 'of' typoTag: Visual edit | ||

| (88 intermediate revisions by 59 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| '''Datasaab''' was the computer division of, and later a separate company spun off from, aircraft manufacturer ] in ], ]. | |||

| '''Datasaab''' was a company branched from ] in ], ] in the late 1950s. ''Data'' is a Swedish word for computer, and the company sprung from the need of heavy calculations when producing the ] ] and later ]. The intent was never to sell or have production of computers, but for a decade the development was very successful and sold several systems in Europe used e.g. in banking and by the military. | |||

| ==History== | |||

| SAAB had previously in 1957 constructed SARA, Swedens second computer (after BESK), to aid with calculations. That little beast used several hundreds of square meters. However, someone came up with the idea (considered as science fiction by then) to build a navigational computer to place in an airplane. With help of the invention of the transistor and very hard work the D2 (only 200 kg) was completed in 1960. The sucessor, D21, was sold to several countries and some 30 units was built. After that, several versions with names like D22, D220, D23, D5, D15, and D16 was developed. In 1971 the vision came true, and a computer (CK37) small and powerful enough to be used in an airplane was used in the fighter Saab 37 Viggen. | |||

| Its history dates back to December 1954, when Saab got a license to build its own copy of ], an early Swedish computer design using ]s, from ] (the Swedish governmental board for mathematical machinery). This clone was completed in {{start date and age|1957|p=y}} and was named ]. Its computing power was needed for design calculations for the next generation jet fighter ]. | |||

| Intending to develop a navigational computer to place in an ], a team led by ] came up with an all ]ized prototype computer named ], completed in 1960, which came to define the company's activities in the following two decades. This development followed two lines. The main purpose was the development of a navigational computer for Viggen. A spinoff was the production of a line of civilian mini and mainframe computers for the commercial market. | |||

| When the Swedish government needed 20 computers in the 1960s to calculate taxes, an evaluation between Saab's and ]'s machines proved Saab's better. Later the D5s was used to set up the first and largest bank terminal system for the Nordic banks, a system which was partly in use until the late 1980s. | |||

| ] | |||

| ⚫ | When ] sued the competitor ] |

||

| The military navigational computer CK37 was completed in 1971 and used in Viggen. | |||

| The first civilian model D21 (1962) was sold to several countries and some 30 units were built. After that, several versions with names like D22 (1966), D220, D23, D5, D15, and D16 were developed. When the Swedish government needed 20 computers in the 1960s to calculate taxes, an evaluation between Saab's and ]'s machines proved Saab's better. Later the D5s were used to set up the first and largest bank terminal system for the ] banks, a system which was partly in use until the late 1980s. In 1975, the D23 system was seriously delayed and the solution was to spin off the large and medium systems to a joint marketing/services company with ] called Saab-Univac.<ref>{{cite news |title=THE TALE OF WOE THAT LED UP TO THE SALE OF ERICSSON's COMPUTER ARM - Tech Monitor |url=https://techmonitor.ai/technology/the_tale_of_woe_that_led_up_to_the_sale_of_ericssons_computer_arm |date=1 February 1988}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Bubenko |first1=Janis |last2=Impagliazzo |first2=John |last3=Soelvberg |first3=Arne |title=History of Nordic Computing: IFIP WG9.7 First Working Conference on the History of Nordic Computing (HiNC1), June 16-18, 2003, Trondheim, Norway |date=14 January 2005 |publisher=Springer Science & Business Media |isbn=978-0-387-24167-8 |page=259 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=qZIgLbka3ogC&pg=PA259 |language=en}}</ref> Eventually Sperry would take full ownership of Saab-UNIVAC once it had completed the conversion of the Saab Mainframe customerbase to the ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Hills |first1=Jill |title=Information Technology and Industrial Policy |date=26 March 2018 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-351-24043-7 |page=223 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=riZTDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT223 |language=en}}</ref> | |||

| The academic computer society ] at ] was founded in 1973 when a donation of an old used D21 was arranged. | |||

| In 1971, technologies from ] (SRT) and Saab were combined to form ] AS, a joint venture that also included the state-owned Swedish Development Company. The company's primary focus was systems for real-time data applied to commercial and aviation applications.<ref>{{cite web |url= http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1972/1972%20-%203354.html | work = Flightglobal | title = Archive | year = 1972 | access-date = 2008-10-29}}</ref> | |||

| In 1975, the D23 was seriously delayed and the company was sold off to ]. Remains of the company was later owned by companies like ], ] and ]. | |||

| In 1978, Stansaab merged with the Datasaab division of ] to become Datasaab AB.<ref name = veterans>{{cite web | url= http://www.veteranklubbenalfa.se/veteran/foretag.htm |trans-title=Short history of SRT, Stansaab and Datasaab | title = Företag | language = sv | publisher = Veteran klubben Alfa | access-date= 2008-10-29}}</ref> It was later owned by ], ] and ]. | |||

| ⚫ | When ] sued the competitor ] for ] infringement over technologies including ] updates of ]s and different parts of the processor working asynchronously, UMC could point to an awarded paper describing how these technologies had been used in the D23 already in 1972. Since Intel's patents were from 1978, that paper would prove prior art and imply that the patents never should have been granted at all. The case was later dropped. | ||

| ⚫ | |||

| The academic computer society ] at ] was founded in 1973 when a donation of an old used D21 was arranged. The company's history has been documented by members of its veteran society, ''Datasaabs Vänner'' ("Friends of Datasaab"), founded in 1993 to document and spread information about the computer history of Sweden, with focus on the region of Linköping and Datasaab. The society has documented the Datasaab history in five books, and documents and pictures of computer systems and products developed and produced by Datasaab are presented at the society homepage. Since 2004 many Datasaab computers are exhibited at the ] computer museum in Linköping. | |||

| A Datasaab history page: http://www.ctrl-c.liu.se/misc/datasaab/om-eng.html | |||

| After a series of mergers, the name Datasaab became connected with an incident of illegal ] to the ] in the late 1970s.<ref>], Nick Anning, David Hebditch, ''Techno-Bandits : how the Soviets are stealing America's high-tech future'' (1984) Boston : Houghton Mifflin, {{ISBN|0-395-36066-8}}, Swedish translation by Bo Kage Carlson the same year, ''Teknobanditerna : om smuggling av högteknologi från väst till öst'', Stockholm : Svenska Dagbladet, {{ISBN|91-7738-064-9}}</ref> A 1973 bid for tender for a civilian ] system at the airports in ], ], and ] was won by Swedish supplier ]. A contract between Stansaab and ] was signed in September 1975. However, parts of the delivered system relied on components from the US, for which the Swedes couldn't get the necessary export licenses. So they bought U.S. components, relabeled them and smuggled them to Moscow using Soviet diplomats. Datasaab separated from Saab in 1978 and joined Stansaab in a new company, Datasaab AB.<ref>{{cite web | |||

| |url=http://www.datasaab.se/Summary/summary.htm | |||

| |title=Summary of the Datasaab History | |||

| |access-date=2012-10-15 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| Allegedly the air traffic control system did support the Soviet invasion of ] in December 1979. The smuggling operation was uncovered in October 1980, known as "the Datasaab affair" (''Datasaabaffären''). In early 1981, Datasaab was acquired by ] and became its computing division Ericsson Information Systems. In April 1984 Ericsson was fined US$3.12 million for breach of U.S. export controls, and agreed to pay. | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ⚫ | ==External links== | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120716210625/http://www.ctrl-c.liu.se/misc/datasaab/om-eng.html |date=2012-07-16 }} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 14:56, 9 September 2024

Datasaab was the computer division of, and later a separate company spun off from, aircraft manufacturer Saab in Linköping, Sweden.

History

Its history dates back to December 1954, when Saab got a license to build its own copy of BESK, an early Swedish computer design using vacuum tubes, from Matematikmaskinnämnden (the Swedish governmental board for mathematical machinery). This clone was completed in 1957 (68 years ago) (1957) and was named SARA. Its computing power was needed for design calculations for the next generation jet fighter Saab 37 Viggen.

Intending to develop a navigational computer to place in an airplane, a team led by Viggo Wentzel came up with an all transistorized prototype computer named D2, completed in 1960, which came to define the company's activities in the following two decades. This development followed two lines. The main purpose was the development of a navigational computer for Viggen. A spinoff was the production of a line of civilian mini and mainframe computers for the commercial market.

The military navigational computer CK37 was completed in 1971 and used in Viggen.

The first civilian model D21 (1962) was sold to several countries and some 30 units were built. After that, several versions with names like D22 (1966), D220, D23, D5, D15, and D16 were developed. When the Swedish government needed 20 computers in the 1960s to calculate taxes, an evaluation between Saab's and IBM's machines proved Saab's better. Later the D5s were used to set up the first and largest bank terminal system for the Nordic banks, a system which was partly in use until the late 1980s. In 1975, the D23 system was seriously delayed and the solution was to spin off the large and medium systems to a joint marketing/services company with Sperry UNIVAC called Saab-Univac. Eventually Sperry would take full ownership of Saab-UNIVAC once it had completed the conversion of the Saab Mainframe customerbase to the 1100 series.

In 1971, technologies from Standard Radio & Telefon AB (SRT) and Saab were combined to form Stansaab AS, a joint venture that also included the state-owned Swedish Development Company. The company's primary focus was systems for real-time data applied to commercial and aviation applications.

In 1978, Stansaab merged with the Datasaab division of Saab-Scania to become Datasaab AB. It was later owned by Ericsson, Nokia and ICL.

When Intel sued the competitor UMC for patent infringement over technologies including microcode updates of processors and different parts of the processor working asynchronously, UMC could point to an awarded paper describing how these technologies had been used in the D23 already in 1972. Since Intel's patents were from 1978, that paper would prove prior art and imply that the patents never should have been granted at all. The case was later dropped.

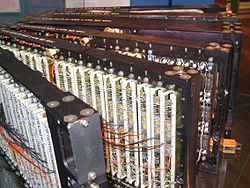

The academic computer society Lysator at Linköping University was founded in 1973 when a donation of an old used D21 was arranged. The company's history has been documented by members of its veteran society, Datasaabs Vänner ("Friends of Datasaab"), founded in 1993 to document and spread information about the computer history of Sweden, with focus on the region of Linköping and Datasaab. The society has documented the Datasaab history in five books, and documents and pictures of computer systems and products developed and produced by Datasaab are presented at the society homepage. Since 2004 many Datasaab computers are exhibited at the IT-ceum computer museum in Linköping.

After a series of mergers, the name Datasaab became connected with an incident of illegal technology transfer to the Soviet Union in the late 1970s. A 1973 bid for tender for a civilian air traffic control system at the airports in Moscow, Kyiv, and Mineralnye Vody was won by Swedish supplier Stansaab. A contract between Stansaab and Aeroflot was signed in September 1975. However, parts of the delivered system relied on components from the US, for which the Swedes couldn't get the necessary export licenses. So they bought U.S. components, relabeled them and smuggled them to Moscow using Soviet diplomats. Datasaab separated from Saab in 1978 and joined Stansaab in a new company, Datasaab AB. Allegedly the air traffic control system did support the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979. The smuggling operation was uncovered in October 1980, known as "the Datasaab affair" (Datasaabaffären). In early 1981, Datasaab was acquired by Ericsson and became its computing division Ericsson Information Systems. In April 1984 Ericsson was fined US$3.12 million for breach of U.S. export controls, and agreed to pay.

References

- "THE TALE OF WOE THAT LED UP TO THE SALE OF ERICSSON's COMPUTER ARM - Tech Monitor". 1 February 1988.

- Bubenko, Janis; Impagliazzo, John; Soelvberg, Arne (14 January 2005). History of Nordic Computing: IFIP WG9.7 First Working Conference on the History of Nordic Computing (HiNC1), June 16-18, 2003, Trondheim, Norway. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-387-24167-8.

- Hills, Jill (26 March 2018). Information Technology and Industrial Policy. Routledge. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-351-24043-7.

- "Archive". Flightglobal. 1972. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- "Företag" [Short history of SRT, Stansaab and Datasaab] (in Swedish). Veteran klubben Alfa. Retrieved 2008-10-29.

- Linda Melvern, Nick Anning, David Hebditch, Techno-Bandits : how the Soviets are stealing America's high-tech future (1984) Boston : Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 0-395-36066-8, Swedish translation by Bo Kage Carlson the same year, Teknobanditerna : om smuggling av högteknologi från väst till öst, Stockholm : Svenska Dagbladet, ISBN 91-7738-064-9

- "Summary of the Datasaab History". Retrieved 2012-10-15.

External links

- Datasaabs Vänner (Datasaab's Friends' Society)

- IT-ceum

- A Datasaab history page Archived 2012-07-16 at the Wayback Machine