| Revision as of 11:03, 16 June 2012 view sourceArchetypex07 (talk | contribs)70 edits →Etymology← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 00:32, 10 January 2025 view source Remsense (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Page movers, New page reviewers, Template editors61,150 edits Reverting edit(s) by TessiDon (talk) to rev. 1267553834 by Some1: Non-constructive edit (UV 0.1.6)Tags: Ultraviolet Undo | ||

| (859 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Male adult human}} | |||

| {{About|adult human males|humans in general|Human|the word|Man (word)|the island|Isle of Man|other uses|Man (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Other uses}} | |||

| {{Redirect4|Manhood|Men}} | |||

| {{redirect-multi|2|Men|Manhood}} | |||

| {{pp-semi-protected|small=yes}}{{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=February 2022}} | |||

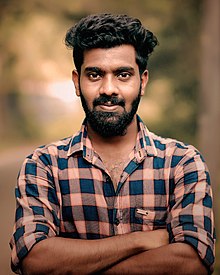

| ] man with medium ], of ], and with ]]]<!--PLEASE NOTE: This image was selected following extensive discussion at ], along with additional discussion on this article's talk page. Please do not remove or replace without talk page consensus. Thank you.--> | |||

| A '''man''' is an ] ] ].{{efn|''Male'' may refer to ] or ].<ref>{{Cite Merriam-Webster|male}}</ref> The plural ''men'' is sometimes used in certain phrases such as '']'' to denote male humans regardless of age.}}<ref>{{Cite web |title=Meaning of "man" in English |url=https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/man |access-date=18 August 2021 |website=dictionary.cambridge.org |publisher=] |language=en |archive-date=6 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230106000222/https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/man |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Definition of "man" |url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/man |access-date=18 August 2021 |website=www.merriam-webster.com |publisher=] |language=en |archive-date=9 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230309135059/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/man |url-status=live }}</ref> Before adulthood, a male human is referred to as a ] (a male ] or ]). | |||

| {{Infobox Ethnic group | |||

| |group = Men | |||

| |image = ] | |||

| |caption = Left to right from top: ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} an ] farmer{{,}} ]{{,}} ]{{,}} Man with child{{,}} ] with ]}} | |||

| Like most other male ]s, a man's ] usually inherits an ] from the mother and a ] from the father. ] of the male fetus is governed by the ] gene on the Y chromosome. During puberty, hormones which stimulate ] production result in the development of ]s that result in even more differences between the sexes. These include greater ], greater height, the growth of ] and a lower body fat composition. Male anatomy is distinguished from female anatomy by the ], which includes the ]s, ]s, ] and ], and ]. Secondary sex characteristics include a narrower ] and ], and smaller ]s and ]. | |||

| In English, lower case '''''man''''' (pl. '''''men''''') refers to an ] ] ] (the term '']'' is the usual term for a human male ] or ]). Sometimes it is also used as an adjective to identify a set of male humans, regardless of age, as in phrases such as "]". Although men typically have a male ], some ] ] with ambiguous genitals, and biologically female ] people, may also be classified or self-identify as a "man". | |||

| Throughout ], traditional ]s have often defined men's activities and opportunities. Men often face ] into military service or are directed into professions with high ]s. Many religious doctrines stipulate certain rules for men, such as ]. Men are over-represented as both perpetrators and ]. | |||

| The term '''''manhood''''' is used to refer to ], the various qualities and characteristics attributed to men such as strength and male sexuality.<ref>http://www.askoxford.com/concise_oed/manhood?view=uk</ref> | |||

| ] have a ] that does not align with their female ] at birth, while ] men may have sex characteristics that do not fit typical notions of male biology. | |||

| ==Etymology== | |||

| {{Main|Man (word)}} | |||

| ]/] ] ], also used to indicate the male sex.]] | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| The ] term "man" is derived from ] ''mann'', which is ultimately derived from the Indian name '']''. The Old English form had a default meaning of "adult male" (which was the exclusive meaning of "wer"), though it could signify a person of unspecified gender. The closely related "man" was used just as it is in Modern German to designate "one" (e.g., as in the saying ''Man muss mit den Wölfen heulen'').<ref>John Richard Clark Hall: A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary</ref> | |||

| {{Further|Man (word)|boy|father|husband|son|godparent|gentleman|widower|}} | |||

| The Old English form is derived from ] ''*]'', "persona", which is also the etonym of ] ''Mann'' "man, husband" and ''man'' "one" (pronoun), ] ''maðr'', and ] ''manna''. According to ], the mythological progenitor of the Germanic tribes was called '']''. The Germanic form is derived from the ] root ''*manu-s'' "man, person", which in turn is derived from the Indian name '']'', mythological progenitor of the Hindus.<ref>Julius Pokorny, ''Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch'', I, 700; I, 726-8.</ref> | |||

| The English term "man" is derived from the ] root ''*man-'' (see ]/] ''manu-'', ] ''mǫž'' "man, male").<ref>''American Heritage Dictionary'', Appendix I: Indo-European Roots. {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20060519035935/http://www.bartleby.com/61/roots/IE295.html|date=19 May 2006 }}. Accessed 22 July 2007.</ref> More directly, the word derives from ] '']''. The Old English form primarily meant "person" or "human being" and referred to men, women, and children alike. The Old English word for "man" as distinct from "]"/"]" or "child" was '']''. ''Mann'' only came to mean "man" in Middle English, replacing ''wer'', which survives today only in the compounds "]" (from Old English '']'', literally "man-wolf"), and "]", literally "man-payment".<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rauer |first1=Christine |title=Mann and Gender in Old English Prose: A Pilot Study |journal=Neophilologus |date=January 2017 |volume=101 |issue=1 |pages=139–158 |doi=10.1007/s11061-016-9489-1|hdl=10023/8978 |s2cid=55817181 |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Etymology, origin and meaning of man |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/man |access-date=2023-03-14 |website=www.etymonline.com |language=en |archive-date=14 August 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200814201349/https://www.etymonline.com/word/man |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Etymology, origin and meaning of wergeld |url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/wergeld |access-date=2022-06-05 |website=www.etymonline.com |language=en |archive-date=5 June 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220605152905/https://www.etymonline.com/word/wergeld |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Biology == <!-- Please don't rename to "...sex" as there is a link from "woman" here. Biology and sex is redundant here, whereas this section does discuss gender in paragraph 5 --> | |||

| ==Age and terminology== | |||

| {{Main| |

{{Main|Sex differences in humans}} | ||

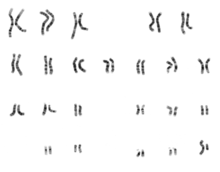

| ] of a human male using ] staining. Human males typically possess an ].]] | |||

| The term '''''manhood''''' is used to describe the period in a human male's life after he has transitioned from ], having passed through ], usually having attained male ], and symbolises a male's ]. The word man is used to mean any adult male. In English-speaking countries, many other words can also be used to mean an adult male such as ''guy'', '']'', '']'', ''bloke'', '']'', ''chap'' and sometimes '']'' or ''lad''. The term ''manhood'' is associated with ] and ], which refer to male qualities and male ]. | |||

| In humans, sperm cells carry either an ] or a ] sex chromosome. If a sperm cell carrying a ] fertilizes the female ], the offspring will have a male karyotype (XY). The ] gene is typically found on the Y chromosome and causes the development of the testes, which in turn govern other aspects of ]. Sex differentiation in males proceeds in a testes-dependent way while female differentiation is not gonad dependent.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Rey |first1=Rodolfo |last2=Josso |first2=Nathalie |last3=Racine |first3=Chrystèle |date=2000 |title=Sexual Differentiation |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279001/ |journal=Endotext |publisher=MDText.com, Inc. |pmid=25905232 |quote=Irrespective of their chromosomal constitution, when the gonadal primordia differentiate into testes, all internal and external genitalia develop following the male pathway. When no testes are present, the genitalia develop along the female pathway. The existence of ovaries has no effect on fetal differentiation of the genitalia. The paramount importance of testicular differentiation for fetal sex development has prompted the use of the expression "sex determination" to refer to the differentiation of the bipotential or primitive gonads into testes. |access-date=6 December 2021 |archive-date=8 August 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220808130515/https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279001/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Primary sex characteristics (or sex organs) are characteristics that are present at birth and are integral to the reproductive process. For men, primary sex characteristics include the ] and ]s. | |||

| == Biology and gender == <!-- Please don't rename to "...sex" as there is a link from "woman" here. Biology and sex is redundant here, whereas this section does discuss gender in paragraph 5 --> | |||

| {{Main|Secondary sexual characteristics|human body}} | |||

| <!--]--> | |||

| ] '']'' displays the proportions of a man.<ref></ref>]] | |||

| Humans exhibit ] in many characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability, although most of these characteristics do have a role in sexual attraction. Most expressions of sexual dimorphism in humans are found in height, weight, and body structure, though there are always examples that do not follow the overall pattern. For example, men tend to be taller than ], but there are many people of both sexes who are in the mid-height range for the species. | |||

| Adult humans exhibit ] in many other characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability. Humans are sexually dimorphic in body size, body structure, and body composition. Men tend to be taller and heavier than women, and adjusted for height, men tend to have greater lean and bone mass than women, and lower fat mass.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Wells |first=Jonathan C. K. |date=2007-09-01 |title=Sexual dimorphism of body composition |url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1521690X07000371 |journal=Best Practice & Research Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism |series=Normal and Abnormal Sex Development |language=en |volume=21 |issue=3 |pages=415–430 |doi=10.1016/j.beem.2007.04.007 |pmid=17875489 |issn=1521-690X}}</ref> | |||

| Some examples of male ] in humans, those acquired as boys become men or even later in life, are: | |||

| * more ] | |||

| * more ] | |||

| * larger hands and feet than women | |||

| * broader ] and chest | |||

| * larger ] and ] structure | |||

| * greater ] mass | |||

| * a more prominent ] and deeper ] | |||

| * a longer shinbone | |||

| ] of both models is removed. |alt=Photograph of an adult male human, with an adult female for comparison. The ] of both models is removed.]] | |||

| ===Sexual characteristics=== | |||

| Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during ] in ]s.<ref name="Melmed">{{cite book |vauthors=Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg HM|title=Williams Textbook of Endocrinology E-Book|publisher=]|isbn=978-1-4377-3600-7|year=2011|page=1054|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=nbg1QOAObicC&pg=PA1054}}</ref><ref name="Pack">{{cite book |vauthors=Pack PE|title=CliffsNotes AP Biology |edition=5th|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-544-78417-8|year=2016|page=219|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=GsalDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA219}}</ref> Such features are especially evident in the ] ]s that distinguish between the sexes, but—unlike the primary sex characteristics—are not directly part of the ].<ref name="Bjorklund">{{cite book |vauthors=Bjorklund DF, Blasi CH|title=Child and Adolescent Development: An Integrated Approach|publisher=]|isbn=978-1-133-16837-9|year=2011|pages=152–153|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZTQIAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA152}}</ref><ref name="auto">{{cite web|url=https://sciencing.com/primary-secondary-sexual-characteristics-8557301.html|title=Primary & Secondary Sexual Characteristics|work=Sciencing.com|date=30 April 2018|access-date=13 October 2019|archive-date=3 August 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200803171707/https://sciencing.com/primary-secondary-sexual-characteristics-8557301.html|url-status=live}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Encyclopedia of Reproduction|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=m4RlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA103|year=2018|publisher=Elsevier Science|isbn=978-0-12-815145-7|page=103|access-date=13 October 2019|archive-date=20 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230120071956/https://books.google.com/books?id=m4RlDwAAQBAJ&pg=PA103|url-status=live}}</ref> Secondary sexual characteristics that are specific to men include: | |||

| In mankind, the sex of an individual is generally determined at the time of ] by the genetic material carried in the ] cell. If a sperm cell carrying an ] fertilizes the ], the offspring will typically be female (XX); if a sperm cell carrying a ] fertilizes the egg, the offspring will typically be male (XY). Persons whose anatomy or chromosomal makeup differ from this pattern are referred to as ]. | |||

| * Broadened shoulders;<ref name="auto2">{{cite book|last=Berger|first=Kathleen Stassen|title=The Developing Person Through the Life Span|url=https://archive.org/details/developingperson00berg_0|url-access=registration|year=2005|publisher=Worth Publishers|isbn=978-0-7167-5706-1|page=}}</ref> | |||

| * Increased body hair; | |||

| * An enlarged larynx (also known as an ]);<ref name="auto2" /> and | |||

| * A voice that is significantly deeper than the voice of a child or a woman.<ref name="auto" /> | |||

| Men weigh more than women.<ref name="Robert- McComb">{{cite book |last1=Robert-McComb |first1=Jacalyn |last2=Norman |first2=Reid L. |last3=Zumwalt |first3=Mimi |title=The Active Female: Health Issues Throughout the Lifespan |date=2014 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-4614-8884-2 |pages=223–238 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=mUjABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA223 |access-date=19 November 2022 |archive-date=31 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731025804/https://books.google.com/books?id=mUjABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA223 |url-status=live }}</ref> On average, men are taller than women by about 10%.<ref name="Robert- McComb" /> On average, men have a larger waist in comparison to their hips (see ]) than women. In women, the index and ring fingers tend to be either more similar in size or their index finger is slightly longer than their ring finger, whereas men's ring finger tends to be longer.<ref name="Halpern">{{cite book |last=Halpern |first=Diane F. |title=Sex Differences in Cognitive Abilities |edition=4th |date=2013 |publisher=] |isbn=978-1-136-72283-7 |page=188 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ocl5AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA188 |access-date=19 November 2022 |archive-date=31 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731025807/https://books.google.com/books?id=ocl5AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA188 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| This is referred to as the ] and is typical of most mammals, but quite a few other ]s exist, including some that are non-genetic. | |||

| === Reproductive system === | |||

| The term primary sexual characteristics denotes the kind of ] the ] produces: the ] produces egg cells in the female, and the ] produces sperm cells in the male. The term secondary sexual characteristics denotes all other sexual distinctions that play indirect roles in uniting sperm and eggs. Secondary sexual characteristics include everything from the specialized male and female features of the genital tract, to the brilliant plumage of male birds or facial hair of humans, to behavioral features such as courtship. | |||

| {{Main|Male reproductive system}} | |||

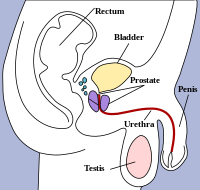

| ] anatomy]] | |||

| The internal male genitalia consist of the ]s, gonads that produce male gametes called ], the ], ], and ]s, accessory glands that partake in sperm health, the ], organs that store sperm cells, and the ] and ]s, tubular structures that transfer the mature sperm to the urethra. | |||

| Biological factors are not sufficient determinants of whether a person considers themselves a man or is considered a man. ] individuals, who have physical and/or genetic features considered to be mixed or atypical for one sex or the other, may use other criteria in making a clear determination. There are also ] or ] men, who were born or physically assigned as female at birth, but identify as men; there are varying social, legal and individual definitions with regard to these issues. (See ].) | |||

| The external male genitalia consist of the ], an organ that expels ], and the ], a pouch of skin housing the testicles. <ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=33684|title=Definition of Male genitalia|website=MedicineNet|access-date=13 October 2019|archive-date=6 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201106152900/https://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=33684|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| ===Reproductive system=== | |||

| ] | |||

| The male ]s are part of the reproductive system, consisting of the ], ], ], and the ] gland. The male reproductive system's function is to produce ] which carries ] and thus ] that can unite with an egg within a ]. Since sperm that enters a woman's ] and then ] goes on to ] an egg which develops into a ] or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the ]. The concept of ]hood and ] exists in human ]. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called ]. | |||

| The male reproductive system's function is to produce ], which carries ] and thus ] that can unite with an ] within a woman. Since sperm that enters a woman's ] and then ]s goes on to ] an egg which develops into a ] or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the ]. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called ].<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Clement |first1=Pierre |last2=Giuliano |first2=François |title=Neurology of Sexual and Bladder Disorders |chapter=Anatomy and physiology of genital organs – men |date=2015 |url=https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26003237/ |series=Handbook of Clinical Neurology |volume=130 |pages=19–37 |doi=10.1016/B978-0-444-63247-0.00003-1 |issn=0072-9752 |pmid=26003237|isbn=978-0-444-63247-0 }}</ref> | |||

| ] of human male using ] staining. Human males typically possess an ].]] | |||

| Testosterone stimulates the development of the ]s, the penis, and closure of the ] into the scrotum. Another significant hormone in sexual differentiation is the ], which inhibits the development of the ]s. For males during puberty, testosterone, along with ]s released by the ], stimulates ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Goodman |first=H. Maurice |title=Basic Medical Endocrinology |publisher=Elsevier |year=2009 |isbn=978-0-12-373975-9 |edition=4th |pages=239–256}}</ref> | |||

| ===Sex hormones=== | |||

| === Health === | |||

| In mammals, the ] that influence sexual differentiation and development are ] (mainly ]), which stimulate later development of the ovary. In the sexually undifferentiated ], testosterone stimulates the development of the ]s, the penis, and closure of the ] into the scrotum. Another significant hormone in sexual differentiation is the ], which inhibits development of the ]s.<BR clear=all> | |||

| {{Further|Gender disparities in health|Men's health}} | |||

| While a majority of the global health gender disparities is weighted against women, there are situations in which men tend to fare poorer. One such instance is ], where men are often the immediate victims. A study of conflicts in 13 countries from 1955 to 2002 found that 81% of all violent ] deaths were male.<ref name="World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development">{{cite report|author=The World Bank|date=2012 |title=World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development |publisher=The World Bank |location=Washington, DC }}</ref> Apart from armed conflicts, areas with high incidence of violence, such as regions controlled by ], also see men experiencing higher mortality rates.<ref> {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191120202335/https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/htus8008.pdf |date=20 November 2019 }} ] (2010) p. 10</ref> This stems from social beliefs that associate ideals of ] with aggressive, confrontational behavior.<ref name="The Street Is My Home: Youth and Violence in Caracas">{{cite book |last=Márquez |first=Patricia |title=The Street Is My Home: Youth and Violence in Caracas |url=https://archive.org/details/streetismyhomeyo0000marq |url-access=registration |year=1999 |publisher=Stanford University Press |location=Stanford, CA}}</ref> Lastly, sudden and drastic changes in economic environments and the loss of ]s, in particular social subsidies and food stamps, have also been linked to higher levels of ] consumption and ] among men, leading to a spike in male mortality rates. This is because such situations often makes it harder for men to provide for their family, a task that has been long regarded as the "essence of masculinity."<ref name="Autopsy on an Empire: Understanding Mortality in Russia and the Former Soviet Union">{{cite journal |last1=Brainerd |first1=Elizabeth |last2=Cutler |first2=David |title=Autopsy on an Empire: Understanding Mortality in Russia and the Former Soviet Union |year=2005 |publisher=William Davidson Institute |location=Ann Arbor, MI|journal= The Journal of Economic Perspectives| volume= 19|issue=1|page=107–30|doi=10.1257/0895330053147921 |jstor=4134995 |url=http://www.jstor.org/stable/4134995|hdl=10419/20771 |hdl-access=free }} | |||

| </ref> A retrospective analyses of people infected with the common cold found that doctors underrate the symptoms of men, and are more willing to attribute symptoms and illness to women than men.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Sue | first1 = Kyle | year = 2017 | title = The science behind 'man flu.' | journal = BMJ | volume = 359 | page = j5560 | doi = 10.1136/bmj.j5560 | pmid = 29229663 | s2cid = 3381640 | url = http://press.psprings.co.uk/bmj/december/manflu.pdf | access-date = 11 January 2018 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20171208203826/http://press.psprings.co.uk/bmj/december/manflu.pdf | archive-date = 8 December 2017 | url-status = dead }}</ref> Women live longer than men in all countries, and across all age groups, for which reliable records exist.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Austad | first1 = S.N.A | last2 = Bartke | first2 = A.A. | year = 2016 | title = Sex Differences in Longevity and in Responses to Anti-Aging Interventions: A Mini-Review | journal = Gerontology | volume = 62 | issue = 1 | pages = 40–46 | doi = 10.1159/000381472 | pmid = 25968226 | url = https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/381472 | doi-access = free | access-date = 31 May 2022 | archive-date = 24 October 2021 | archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20211024110651/https://www.karger.com/Article/Pdf/381472 | url-status = live }}</ref> In the United States, men are less healthy than women across all social classes. Non-white men are especially unhealthy. Men are over-represented in dangerous occupations and represent a majority of on the job deaths. Further, medical doctors provide men with less service, less advice, and spend less time with men than they do with women per medical encounter.<ref>{{cite journal | last1 = Williams | first1 = David R. | date = May 2003 | title = The Health of Men: Structured Inequalities and Opportunities | journal = Am J Public Health | volume = 93 | issue = 5| pages = 724–731 | pmc=1447828 | pmid=12721133 | doi=10.2105/ajph.93.5.724}}</ref> | |||

| == Sexuality and gender == | |||

| ===Illnesses=== | |||

| {{Further|Human male sexuality|Trans man}} | |||

| In general, men suffer from many of the same ]es as women. In comparison to women, men suffer from slightly more illnesses.{{Citation needed|date=September 2008}} Male life expectancy is slightly lower than female life expectancy, although the difference has narrowed in recent years. | |||

| ] and ]]] | |||

| For males during puberty, testosterone, along with ] released by the ], stimulates ], along with the full sexual distinction of a human male from a human female, while women are acted upon by estrogens and progesterones to produce their sexual distinction from the human male. | |||

| Male sexuality and attraction varies between individuals, and a man's sexual behavior can be affected by many factors, including ], ], ], and ]. While most men are ], significant minorities are ] or ].<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Bailey|first1=J. Michael|last2=Vasey|first2=Paul|last3=Diamond|first3=Lisa|author4-link=Marc Breedlove|last4=Breedlove|first4=S. Marc|last5=Vilain|first5=Eric|last6=Epprecht|first6=Marc|title=Sexual Orientation, Controversy, and Science|journal=Psychological Science in the Public Interest|date=2016|volume=17|issue=2|pages=45–101|doi=10.1177/1529100616637616|pmid=27113562|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301639075|doi-access=free|access-date=21 December 2019|archive-date=2 December 2019|archive-url=https://wayback.archive-it.org/all/20191202204542/https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301639075_Sexual_Orientation_Controversy_and_Science|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ==Masculinity== | |||

| {{globalize|date=December 2010}} | |||

| {{Main|Masculinity}} | |||

| {{See also|Stereotype}} | |||

| ]'s ]'' is the ] image of youthful male ] in ].]] | |||

| Most cultures use a ] in which man is one of the two genders, the other being ].<ref name="Nadal-re-binary">Kevin L. Nadal, ''The Sage Encyclopedia of Psychology and Gender'' (2017, {{ISBN|978-1-4833-8427-6}}), p. 401: "Most cultures currently construct their societies based on the understanding of gender binary—the two gender categorizations (male and female). Such societies divide their population based on biological sex assigned to individuals at birth to begin the process of gender socialization."</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Sigelman |first1=Carol K. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=M2M1DgAAQBAJ&pg=PA385 |title=Life-Span Human Development |last2=Rider |first2=Elizabeth A. |date=2017 |publisher=Cengage Learning |isbn=978-1-337-51606-8 |page=385 |language=en |access-date=4 August 2021 |archive-date=21 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230721050224/https://books.google.com/books?id=M2M1DgAAQBAJ&pg=PA385 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Maddux |first1=James E. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=Q-ChDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT1028 |title=Psychopathology: Foundations for a Contemporary Understanding |last2=Winstead |first2=Barbara A. |date=2019 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-429-64787-1 |language=en |access-date=4 August 2021 |archive-date=21 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230721050212/https://books.google.com/books?id=Q-ChDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT1028 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Enormous debate in Western societies has focused on perceived social, intellectual, or emotional differences between women and men. These differences are very difficult to quantify for both scientific and political reasons. | |||

| Most men are ], and their ] aligns with their ] at birth. ] have a male gender identity that does not align with their ] at birth, and may undergo masculinizing ] and/or ].<ref name="whatare">{{cite web|url=http://www.apa.org/topics/transgender.html|title=what are Answers to Your Questions About Transgender Individuals and Gender Identity|publisher=]|access-date=26 January 2015|archive-date=7 September 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150907185309/http://www.apa.org/topics/transgender.html|url-status=live}}</ref> ] men may have sex characteristics that do not fit typical notions of male biology.<ref>{{Cite web |title=What is Intersex? Frequently Asked Questions |url=https://interactadvocates.org/faq/ |access-date=2022-12-15 |website=interACT: Advocates for Intersex Youth |language=en-US |archive-date=31 December 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201231200008/https://interactadvocates.org/faq/ |url-status=live }}</ref> A 2016 systemic review estimated that 0.256% of people self-identify as female-to-male transgender.<ref name="Collin2016">{{Cite journal|last1=Collin|first1=Lindsay|last2=Reisner|first2=Sari L.|last3=Tangpricha|first3=Vin|last4=Goodman|first4=Michael|date=2016|title=Prevalence of Transgender Depends on the "Case" Definition: A Systematic Review|journal=The Journal of Sexual Medicine|language=en|volume=13|issue=4|pages=613–626|doi=10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.02.001|pmc=4823815|pmid=27045261}}</ref> A 2017 survey of 80,929 Minnesota students found that roughly twice as many female-assigned adolescents self-identified as transgender, compared to adolescents with a male sex assignment.<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Goodman|first1=Michael|last2=Adams|first2=Noah|last3=Corneil|first3=Trevor|last4=Kreukels|first4=Baudewijntje|last5=Motmans|first5=Joz|last6=Coleman|first6=Eli|date=1 June 2019|title=Size and Distribution of Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Populations: A Narrative Review|url=https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0889852919300015|journal=Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America|series=Transgender Medicine|language=en|volume=48|issue=2|pages=303–321|doi=10.1016/j.ecl.2019.01.001|pmid=31027541|s2cid=135439779|issn=0889-8529}}</ref> | |||

| Masculinity has its roots in ] (see ]).<ref>John Money, 'The concept of gender identity disorder in childhood and adolescence after 39 years', Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy 20 (1994): 163-77.</ref><ref> | |||

| Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, ''Washington Post'', 19 December 2006.</ref> Therefore while masculinity looks different in different cultures, there are common aspects to its definition across cultures.<ref>], '']''</ref> Sometimes gender scholars will use the phrase "] masculinity" to distinguish the most dominant form of masculinity from other variants. In the mid-twentieth century United States, for example, ] might embody one form of masculinity, while ] might be seen as masculine, but not in the same "hegemonic" fashion. | |||

| == Social role == | |||

| ] is a form of masculine culture. It includes assertiveness or standing up for one's rights, responsibility, selflessness, general code of ethics, sincerity, and respect.<ref>Mirande, Alfredo (1997). ''Hombres y Machos: Masculinity and Latino Culture'', p.72-74. ISBN 0-8133-3197-8.</ref> | |||

| === Masculinity === | |||

| Anthropology has shown that masculinity itself has ], just like wealth, ] and ]. In ], for example, greater masculinity usually brings greater social status. Many English words such as ''virtue'' and ''virile'' (from the Latin and Sanskrit roots ''vir'' meaning ''man'') reflect this.<ref>{{cite web| title =Virtue (2009) | publisher =Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary | month = | year =2009 | url =http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virtue | accessdate =2009-06-08 }}</ref><ref>{{cite web| title =Virile (2009) | publisher =Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary | month = | year =2009 | url =http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virile | accessdate =2009-06-08 }}</ref> An association with physical and/or moral strength is implied. Masculinity is associated more commonly with adult men than with boys. | |||

| {{Main|Masculinity}} | |||

| ]'s '']'' is the ] image of youthful male beauty in ].]] | |||

| Masculinity (also sometimes called ''manhood'' or ''manliness'') is the set of personality traits and attributes associated with boys and men. Although masculinity is ],<ref name=shehan>{{cite book |last1=Shehan |first1=Constance L. |title=Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Gender |date=2018 |publisher=Gale, Cengage Learning |isbn=978-1-5358-6117-5 |pages=1–5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F_F1DwAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=25 December 2019 |archive-date=19 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119211639/https://books.google.com/books?id=F_F1DwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }}</ref> some research indicates that some behaviors considered masculine are biologically influenced.<ref name="books.google.com">Social vs biological citations: | |||

| A great deal is now known about the development of masculine characteristics. The process of ] specific to the reproductive system of ''Homo sapiens'' produces a female by default. The ] on the ], however, interferes with the default process, causing a chain of events that, all things being equal, leads to ] formation, ] production and a range of both pre-natal and post-natal hormonal effects covered by the terms ''masculinization'' or '']''. Because masculinization redirects biological processes from the default female route, it is more precisely called '']''. | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Shehan |first1=Constance L. |title=Gale Researcher Guide for: The Continuing Significance of Gender |date=2018 |publisher=Gale, Cengage Learning |isbn=978-1-5358-6117-5 |pages=1–5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F_F1DwAAQBAJ |language=en |access-date=25 December 2019 |archive-date=19 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119211639/https://books.google.com/books?id=F_F1DwAAQBAJ |url-status=live }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Martin |first1=Hale |last2=Finn |first2=Stephen E. |title=Masculinity and Femininity in the MMPI-2 and MMPI-A |date=2010 |publisher=University of Minnesota Press |isbn=978-0-8166-2444-7 |pages=5–13 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=5KLPlmr9T7MC&q=%22what+masculinity+and+femininity+are%22 |access-date=27 May 2021 |archive-date=19 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119211639/https://books.google.com/books?id=5KLPlmr9T7MC&q=%22what+masculinity+and+femininity+are%22 |url-status=live }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Lippa |first1=Richard A. |title=Gender, Nature, and Nurture |date=2005 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-135-60425-7 |edition=2nd |pages=153–154, 218–225 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=R6OPAgAAQBAJ&q=%22biology+contributes%22+%22masculinity+and+femininity%22 |access-date=27 May 2021 |archive-date=19 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119211640/https://books.google.com/books?id=R6OPAgAAQBAJ&q=%22biology+contributes%22+%22masculinity+and+femininity%22 |url-status=live }} | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Wharton |first=Amy S. |title=The Sociology of Gender: An Introduction to Theory and Research |date=2005 |publisher=John Wiley & Sons |isbn=978-1-4051-4343-1 |pages=29–31 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=SOTqzUeqmNMC&q=%22+biological+or+genetic+contributions%22 |access-date=27 May 2021 |archive-date=19 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119211640/https://books.google.com/books?id=SOTqzUeqmNMC&q=%22+biological+or+genetic+contributions%22 |url-status=live }}</ref> To what extent masculinity is biologically or socially influenced is subject to debate.<ref name="books.google.com" /> It is ] from the definition of the ], as both males and females can exhibit masculine traits.<ref>Male vs Masculine/Feminine: | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Ferrante|first=Joan|title=Sociology: A Global Perspective|publisher=Thomson Wadsworth|location=Belmont, CA|isbn=978-0-8400-3204-1|edition=7th|pages=269–272|date= 2010}} | |||

| * {{cite web |title=What do we mean by 'sex' and 'gender'? |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140908003355/http://www.who.int/gender/whatisgender/en/ |archive-date=8 September 2014 |url=https://www.who.int/gender/whatisgender/en/ |publisher=World Health Organization }} | |||

| * {{cite book |author=Halberstam, Judith |editor1-last=Kimmel |editor1-first=Michael S. |editor2-last=Aronson |editor2-first=Amy |title=Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1 |date=2004 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |location=Santa Barbara, Calif. |isbn=978-1-57607-774-0 |pages=294–295 |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jWj5OBvTh1IC&pg=PA294 |chapter='Female masculinity' |access-date=25 December 2019 |archive-date=19 January 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119211642/https://books.google.com/books?id=jWj5OBvTh1IC&pg=PA294 |url-status=live }}</ref> Men generally face ] for embodying ] traits, more so than women do for embodying masculine traits.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=33–34}} This can also manifest as ].{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=146–149}} | |||

| Standards of manliness or masculinity vary across different cultures and historical periods.<ref>{{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=jWj5OBvTh1IC&q=%22meanings+of+manhood+vary%22|title=Men and Masculinities: A Social, Cultural, and Historical Encyclopedia, Volume 1|date=2004|publisher=ABC-CLIO|isbn=978-1-57607-774-0|editor1-last=Kimmel|editor1-first=Michael S.|location=Santa Barbara, Calif.|page=xxiii|editor2-last=Aronson|editor2-first=Amy|access-date=30 May 2019|archive-date=19 January 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230119212151/https://books.google.com/books?id=jWj5OBvTh1IC&q=%22meanings+of+manhood+vary%22|url-status=live}}</ref> While the outward signs of masculinity look different in different cultures, there are some common aspects to its definition across cultures. In all cultures in the past, and still among traditional and non-Western cultures, getting married is the most common and definitive distinction between boyhood and manhood.<ref name=":0">{{Cite journal|last=Arnett|first=Jeffrey Jensen|date=1998|title=Learning to Stand Alone: The Contemporary American Transition to Adulthood in Cultural and Historical Context|url=https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/22591|journal=Human Development|language=en|volume=41|issue=5–6|pages=295–315|doi=10.1159/000022591|s2cid=143862036|issn=0018-716X|access-date=28 November 2018|archive-date=28 November 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20181128080429/https://www.karger.com/Article/Abstract/22591|url-status=live}}</ref> In the late 20th century, some qualities traditionally associated with marriage (such as the "triple Ps" of ''protecting, providing, and ]'') were still considered signs of having achieved manhood.<ref name=":0" /><ref>{{Cite book|url=https://archive.org/details/manhoodinmaking00davi|url-access=registration|title=Manhood in the Making: Cultural Concepts of Masculinity|last=Gilmore|first=David D.|date=1990|publisher=Yale University Press|isbn=0-300-05076-3|page=|language=en}}</ref> | |||

| There is an extensive debate about how children develop ]. | |||

| === Relationships === | |||

| In many cultures displaying characteristics not typical to one's gender may become a social problem for the individual. Among men, some non-standard behaviors may be considered a sign of ], while a girl who exhibits masculine behavior is more frequently dismissed as a "]". Within ] such labeling and conditioning is known as ] and is a part of ] to better match a culture's ]. The corresponding social condemnation of excessive masculinity may be expressed in terms such as "]" or "]." | |||

| ] | |||

| Platonic relationships are not significantly different between men and women, though some differences do exist. Friendships involving men tend to be based more on shared activities than self-disclosure and personal connection. Perceptions of friendship involving men varies among cultures and time periods.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=494–499}} In heterosexual romantic relationships, men are typically expected to take a proactive role, initiate the relationship, plan dates, and propose marriage.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=571–574}} | |||

| === Status === | |||

| The relative importance of the roles of socialization and genetics in the development of masculinity continues to be debated. While ] obviously plays a role, it can also be observed that certain aspects of the masculine identity exist in almost all human cultures. | |||

| ] has shown that masculinity itself has ], just like wealth, ] and social class. In ], for example, greater masculinity usually brings greater social status.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=45–48}} Many English words such as ''virtue'' and ''virile'' (from the ] ''vir'' meaning ''man'') reflect this.<ref>{{cite web |title=Virtue (2009) |publisher=Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary |year=2009 |url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virtue |access-date=8 June 2009 |archive-date=25 April 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090425184204/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virtue |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Virile (2009) |publisher=Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary |year=2009 |url=http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virile |access-date=8 June 2009 |archive-date=25 April 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090425184113/http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/virile |url-status=live }}</ref> In most cultures, ] allows men more rights and privileges than women. In societies where men are not given special legal privileges, they typically hold more positions of power, and men are seen as being taken more seriously in society.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=45–48}} This is associated with a "gender-role strain" in which men face increased societal pressure to conform to gender roles.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=119–121}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| The historical development of gender role is addressed by such fields as ], ], ] and ]. All human ]s seem to encourage the development of gender roles, through ], ] and ]. Some examples of this might include the epics of ], the ] tales in English, the ] commentaries of ] or biographical studies of the prophet ]. More specialized treatments of masculinity may be found in works such as the '']'' or ]'s '']''. | |||

| The earliest known recorded name of a man in writing is potentially ], who would have lived sometime between 3400 and 3000 BC in the ]ian city of ]; though his name may have been a title rather than his actual name.<ref name="Harari">{{cite book |last=Harari |first=Yuval Noah |title=] |publisher=] |year=2014 |isbn=978-0-7710-8351-8 |edition=Signal paperback |page=123 |chapter=Signed, Kushim |author-link=Yuval Noah Harari |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/sapiensbriefhist0000hara/page/122/mode/2up |chapter-url-access=registration}}</ref> The earliest confirmed names are that of Gal-Sal and his two slaves named En-pap X and Sukkalgir, from {{Circa|3100 BC}}.<ref>{{Cite web |date=2015-08-19 |title=Who's the First Person in History Whose Name We Know? |url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/whos-the-first-person-in-history-whose-name-we-know |access-date=2023-03-10 |website=Science |language=en |archive-date=31 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731025918/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/whos-the-first-person-in-history-whose-name-we-know |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| == Family == | |||

| ==Culture and gender roles== | |||

| {{ |

{{further|Father}} | ||

| ] | |||

| ] is the leader of the ], a position that is reserved for men only.]] | |||

| Men may have children, whether biological or ]; such men are called fathers. The role of men in the family has shifted considerably in the 20th and 21st centuries, taking on a more active role in raising children in most societies.<ref name=":11">{{Cite news |last=University of California, Irvine |date=September 28, 2016 |title=Today's parents spend more time with their kids than moms and dads did 50 years ago |work=Science Daily |url=https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/09/160928160716.htm |access-date=November 3, 2020 |archive-date=30 October 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201030195725/https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/09/160928160716.htm |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last1=Livingston |first1=Gretchen |last2=Parker |first2=Kim |date=19 June 2019 |title=8 facts about American dads |url=https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/12/fathers-day-facts/ |access-date=2022-02-02 |website=Pew Research Center |language=en-US |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310211846/https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/12/fathers-day-facts/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last1=Blamires |first1=Diana |last2=Kirkham |first2=Sophie |date=17 August 2005 |title=Fathers play greater role in childcare |url=http://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/aug/17/gender.children |access-date=2022-02-02 |website=the Guardian |language=en |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310211847/https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2005/aug/17/gender.children |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Huerta |first1=Maria C. |last2=Adema |first2=Willem |last3=Baxter |first3=Jennifer |last4=Han |first4=Wen-Jui |last5=Lausten |first5=Mette |last6=Lee |first6=RaeHyuck |last7=Waldfogel |first7=Jane |date=16 December 2014 |title=Fathers' Leave and Fathers' Involvement: Evidence from Four OECD Countries |journal=European Journal of Social Security |volume=16 |issue=4 |pages=308–346 |doi=10.1177/138826271401600403 |issn=1388-2627 |pmc=5415087 |pmid=28479865}}</ref> Men would traditionally marry a woman when raising children, but in modern times many countries now allow for ], and for those couples to raise children either via adoption or ]. Men may be ]s, and are increasingly so in modern times, though women are three times more likely to be single parents than men.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Single-Parent Family {{!}} Psychology Today |url=https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/family-dynamics/single-parent-family |access-date=2023-03-10 |website=www.psychologytoday.com |language=en-US |archive-date=31 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731030026/https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/family-dynamics/single-parent-family |url-status=live }}</ref> In ] societies, men have typically have been regarded as the "head of household" and held additional social privileges.<ref>{{Cite web|last=Bell |first=Kenton |date=2014-12-25 |title=head of household definition {{!}} Open Education Sociology Dictionary |url=https://sociologydictionary.org/head-of-household/ |language=en-US |access-date=10 March 2023 |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310211847/https://sociologydictionary.org/head-of-household/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Well into prehistoric culture, men are believed to have assumed a variety of social and cultural roles which are likely similar across many groups of humans. In hunter-gatherer societies, men were often if not exclusively responsible for all large game killed, the capture and raising of most or all domesticated animals, the building of permanent shelters, the defense of villages, and other tasks where the male physique and strong spatial-cognition were most useful.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} Some anthropologists believe that it may have been men who led the Neolithic Revolution and became the first pre-historical ranchers, as a possible result of their intimate knowledge of animal life.{{Citation needed|date=August 2011}} | |||

| == Work == | |||

| Throughout history, the roles of men have changed greatly. As societies have moved away from agriculture as a primary source of jobs, the emphasis on male physical ability has waned. Traditional gender roles for working men typically involved jobs emphasizing moderate to hard manual labor (see ]), often with no hope for increase in wage or position. For poorer men among the working classes, the need to support their families, especially during periods of industrial change and economic decline, forced them to stay in dangerous jobs working long arduous hours, often without retirement. Many industrialized countries have seen a shift to jobs which are less physically demanding, with a general reduction in the percentage of manual labor needed in the work force (see ]). The male goal in these circumstances is often of pursuing a quality ] and securing a dependable, often office-environment, source of income. | |||

| {{See also|Work (human activity)}} | |||

| Men have traditionally held jobs that were not available to women. Such jobs tended to be either more strenuous, more prestigious, or more dangerous. Modern men increasingly take untraditional career paths, such as staying home and raising children while their partner works.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Heppner |first1=Mary J. |last2=Heppner |first2=P. Paul |date=September 2009 |title=On Men and Work: Taking the Road Less Traveled |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0894845309340789 |journal=Journal of Career Development |language=en |volume=36 |issue=1 |pages=49–67 |doi=10.1177/0894845309340789 |s2cid=145053662 |issn=0894-8453 |access-date=10 March 2023 |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310213702/https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0894845309340789 |url-status=live }}</ref> Modern men tend to work longer than women, which impacts their ability to spend time with their families.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Williams |first=Joan C. |date=2013-05-29 |title=Why Men Work So Many Hours |work=Harvard Business Review |url=https://hbr.org/2013/05/why-men-work-so-many-hours |access-date=2023-03-10 |issn=0017-8012 |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310213700/https://hbr.org/2013/05/why-men-work-so-many-hours |url-status=live }}</ref> Even in modern times, some jobs remain available only to men, such as military service.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Micheletti |first=Alberto |date=2018-08-18 |title=Why is warfare almost exclusively male? |url=https://theprint.in/defence/why-is-warfare-almost-exclusively-male/100746/ |access-date=2023-03-10 |website=ThePrint |language=en-US |archive-date=31 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731031518/https://theprint.in/defence/why-is-warfare-almost-exclusively-male/100746/ |url-status=live }}</ref> ], currently only ten countries include women in their conscription programs.<ref>Goldstein, Joshua S. (2003). {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731031639/https://books.google.com/books?id=XUAsskBg8ywC&pg=PA108 |date=31 July 2023 }}. In Ember, Carol R.; Ember, Melvin ''Encyclopedia of Sex and Gender: Men and Women in the World's Cultures''. Volume 1. ]. p. 108. {{ISBN|978-0-306-47770-6}}. Retrieved April 25, 2015.</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Persson |first1=Alma |last2=Sundevall |first2=Fia |date=2019-03-22 |title=Conscripting women: gender, soldiering, and military service in Sweden 1965–2018 |journal=Women's History Review |volume=28 |issue=7 |pages=1039–1056 |doi=10.1080/09612025.2019.1596542 |issn=0961-2025 |doi-access=free}}</ref> Men continue to hold more dangerous jobs than women, even in developed countries. In the United States in 2020, ten times as many men died on the job as women, and a man was ten times more likely to die on the job than a woman.<ref>{{Cite web |last=DeVore |first=Chuck |title=Fatal Employment: Men 10 Times More Likely Than Women To Be Killed At Work |url=https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckdevore/2018/12/19/fatal-employment-men-10-times-more-likely-than-women-to-be-killed-at-work/ |access-date=2023-03-10 |website=Forbes |language=en |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310220400/https://www.forbes.com/sites/chuckdevore/2018/12/19/fatal-employment-men-10-times-more-likely-than-women-to-be-killed-at-work/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Entertainment and media == | |||

| ]s ], ], ], ], and ]. While no law reserves the Presidency for men, all United States Presidents have been men thus far.]] | |||

| Media portrayals of men often replicate traditional understanding of masculinity. Men are portrayed more frequently in television than women and most commonly appear as leads in action and drama programming. Men are typically more active in television programming than women and typically hold more power and status. Due to their prominence, men are more likely to be both the objects and instigators of humorous or disparaging content. Fathers are often portrayed in television as either idealized and caring or clumsy and inept. In advertising, men are disproportionately featured in advertisements for alcohol, vehicles, and business products.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Fejes |first=Fred J. |title=Masculinity as Fact: A Review of Empirical Mass Communication Research on Masculinity |publisher=SAGE Publications |year=1992 |isbn=978-0-8039-4163-2 |editor-last=Craig |editor-first=Steve |pages=9–22 |chapter=Considering Men and the Media}}</ref> | |||

| == Clothing == | |||

| The ] is in part a struggle for the recognition of equality of opportunity with women, and for equal rights irrespective of gender, even if special relations and conditions are willingly incurred under the form of partnership involved in marriage. The difficulties of obtaining this recognition are due to the habits and customs recent history has produced. Through a combination of economic changes and the efforts of the feminist movement in recent decades, men in some societies now compete with women for jobs that traditionally excluded women. Some larger corporations have instituted tracking systems to try to ensure that jobs are filled based on merit and not just on traditional gender selection. Assumptions and expectations based on sex roles both benefit and harm men in Western society (as they do women, but in different ways) in the workplace as well as on the topics of education, violence, health care, politics, and fatherhood - to name a few. Research has identified anti-male sexism in some areas (a concept which must be distinguished and differentiated from the traditional anti-female sexism in its ubiquity and impact) which can result in what appear to be unfair advantages given to women. | |||

| ] stands next to a display of men's ] at a clothing factory.]] | |||

| Men's clothing typically encompasses a range of garments designed for various occasions, seasons, and styles. Fundamental items of a man's wardrobe include shirts, trousers, suits, and jackets, which are designed to provide both comfort and style while prioritizing functionality. Men's fashion also encompasses more casual garments such as ], ], ], ], and ], which are typically intended for informal settings. Cultural and regional traditions often influence men's fashion, resulting in diverse styles and garments that reflect the unique characteristics of different parts of the world.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Karlen |first1=Josh |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=BVE3N2rBEF0C |title=The Indispensable Guide to Classic Men's Clothing |last2=Sulavik |first2=Christopher |date=1999 |publisher=Tatra Press |isbn=978-0-9661847-1-6 |language=en |access-date=7 March 2023 |archive-date=7 April 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230407034928/https://books.google.com/books?id=BVE3N2rBEF0C |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| == Education == | |||

| The ] was used to contrast and illustrate extreme positions on gender roles. Model A describes total separation of male and female roles, while Model B describes the complete dissolution of barriers between gender roles.<ref>Brockhaus: Enzyklopädie der Psychologie, 2001.</ref> The examples are based on the context of the culture and ] of the United States. However, these extreme positions are rarely found in reality; actual behavior of individuals is usually somewhere between these poles. The most common 'model' followed in real life in the United States and ] is the 'model of double burden'.{{Clarify|date=August 2011}} | |||

| ] class in 1908 at ]]] | |||

| Men traditionally received more education than women as a result of ]. Universal education, meaning state-provided primary and secondary education independent of gender, is not yet a global norm, even if it is assumed in most developed countries.<ref>{{cite web |title=Historical summary of faculty, students, degrees, and finances in degree-granting institutions: Selected years, 1869–70 through 2005–06 |url=http://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d07/tables/dt07_178.asp |access-date=2014-08-22 |publisher=Nces.ed.gov |archive-date=17 November 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171117072828/https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d07/tables/dt07_178.asp |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Women (Still) Need Not Apply:The Gender and Science Reader |publisher=Routledge |year=2001 |location=New York |pages=13–23 |author1=Eisenhart, A. Margaret |author2=Finkel, Elizabeth }}</ref> In the 21st century, the balance has shifted in many developed nations, and men now lag behind women in education.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Directorate-General for Education |first1=Youth |url=https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/509505 |title=Study on gender behaviour and its impact on education outcomes (with a special focus on the performance of boys and young men in education): final report |last2=ECORYS |last3=Staring |first3=François |last4=Donlevy |first4=Vicki |last5=Day |first5=Laurie |last6=Georgallis |first6=Marianna |last7=Broughton |first7=Andrea |date=2021 |publisher=Publications Office of the European Union |isbn=978-92-76-40249-7 |location=LU |doi=10.2766/509505 |access-date=10 March 2023 |archive-date=31 July 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230731031752/https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/414f506c-df95-11eb-895a-01aa75ed71a1/language-en |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Men are more likely than women to be faculty at universities.<ref>{{cite book |title=A six-year Longitudinal Study of Undergraduate Women in Engineering and Science:The Gender and Science Reader |publisher=Routledge |year=2001 |location=New York |pages=24–37 |author1=Brainard, Susanne G. |author2=Carlin, Linda }}</ref> | |||

| === Exclusively male roles === | |||

| In 2020, 90% of the world's men were ], compared to 87% of women. But sub-Saharan Africa, and southwest Asia lagged behind the rest of the world; only 72% of men in sub-Saharan Africa were literate.<ref>{{Cite web |title=This is how much global literacy has changed over 200 years |url=https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/reading-writing-global-literacy-rate-changed/ |access-date=2023-03-10 |website=World Economic Forum |date=12 September 2022 |language=en |archive-date=10 March 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230310204824/https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/09/reading-writing-global-literacy-rate-changed/ |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Some positions and titles are reserved for men only. For example, the position of ] in the ] is reserved for men only, as is its ]. Men are often given priority for the position of ] (] in the case of a man) of a country, as it usually passes to the eldest male child upon ]. | |||

| == |

== Rights == | ||

| {{Further information|Male privilege|Discrimination against men}} | |||

| {{Portal|Gender studies}} | |||

| In most societies, men have more legal and cultural rights than women.{{Sfn|Helgeson|2017|pp=45–48}} and ] is far more prevalent than ] in society.<ref name="Ouellette">{{cite book |last=Ouellette |first=Marc |title=International Encyclopedia of Men and Masculinities |date=2007 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-33343-6 |editor1=Flood, Michael |editor1-link=Michael Flood |location=Abingdon; New York |pages=442–443 |chapter=Misandry |display-editors=etal |chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=T54J3Q_VwnIC&q=misandry&pg=PA442}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Gilmore |first=David D. |title=Misogyny: The Male Malady |publisher=University of Pennsylvania Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-8122-0032-4 |pages=12–13}}</ref> While one in six male experiences ],<ref>{{cite journal | journal=Child Abuse & Neglect | title=Prevalence and psychological sequelae of self-reported childhood physical and sexual abuse in a general population sample of men and women | volume=27 | pages=1205–1222 | date= 2003| issue=10 | doi=10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.09.008 | pmid=14602100 | last1=Briere | first1=John | last2=Elliott | first2=Diana M. }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=American Journal of Preventive Medicine | title=Long-term consequences of childhood sexual abuse by gender of victim | volume=28 | pages=430–438 | date= 2005| issue=5 | doi=10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.015 | pmid=15894146 | last1=Dube | first1=S. | last2=Anda | first2=R. | last3=Whitfield | first3=C. | last4=Brown | first4=D. | last5=Felitti | first5=V. | last6=Dong | first6=M. | last7=Giles | first7=W. }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Journal of the American Medical Association | title=Sexual abuse of boys: Definition, prevalence, correlates, sequelae, and management | volume=280 | pages=1855–1862 | date= 1998| issue=21 | doi=10.1001/jama.280.21.1855 | pmid=9846781 | last1=Holmes | first1=W. C. | last2=Slap | first2=G. B. }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Journal of Traumatic Stress | title=Factors in the cycle of violence: Gender rigidity and emotional constriction | volume=9 | pages=721–743 | date= 1996| issue=4 | doi=10.1002/jts.2490090405 | pmid=8902743 | last1=Lisak | first1=David | last2=Hopper | first2=Jim | last3=Song | first3=Pat }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Child Abuse & Neglect | title=Sexual abuse in a national survey of adult men and women: Prevalence, characteristics, and risk factors | volume=14 | pages=19–28 | date= 1990| issue=1 | doi=10.1016/0145-2134(90)90077-7 | pmid=2310970 | last1=Finkelhor | first1=David | last2=Hotaling | first2=Gerald | last3=Lewis | first3=I.A | last4=Smith | first4=Christine }}</ref> men typically receive less support after being victims of it,<ref>{{cite journal | journal=International Criminal Law Review | title=Sexual Violence against Men and International Law – Criminalising the Unmentionable | volume=13 | issue=3 | pages=665–695 | date= 2013 | url=https://doi.org/10.1163/15718123-01303004 | doi=10.1163/15718123-01303004 | last1=Mouthaan | first1=Solange }}</ref> and ] is stigmatized.<ref name="Rabin">{{cite news |last=Rabin |first=Roni Caryn |date=23 January 2012 |title=Men Struggle for Rape Awareness |newspaper=The New York Times |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/24/health/as-victims-men-struggle-for-rape-awareness.html |access-date=30 November 2013 |archive-date=10 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211010112128/https://www.nytimes.com/2012/01/24/health/as-victims-men-struggle-for-rape-awareness.html |url-status=live }}</ref> ] is similarly stigmatized,<ref name="Marginalizing">{{cite journal |last=Migliaccio |first=Todd A. |date=Winter 2001 |title=Marginalizing the Battered Male |journal=] |volume=9 |issue=2 |pages=205–226 |doi=10.3149/jms.0902.205 |s2cid=145293675}} {{subscription required}}</ref> although men make up half of the victims in ] couples.<ref>{{cite journal | journal=Trauma Violence Abuse | title=Female perpetration of violence in heterosexual intimate relationships: adolescence through adulthood | volume=9 | issue=4 | pages=227–49 | date= October 2008 | doi=10.1177/1524838008324418| pmid=18936281 | pmc=2663360 | last1=Williams | first1=J. R. | last2=Ghandour | first2=R. M. | last3=Kub | first3=J. E. }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Review of General Psychology | title=Sex Differences in Aggression in Real-World Settings: A Meta-Analytic Review | volume=8 | issue=4 | pages=291–322 | date= 2004 | url=https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291 | doi=10.1037/1089-2680.8.4.291 | last1=Archer | first1=John }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | journal=Report on Intimate | title=The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey 2016/2017 | publisher=Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | url=https://www.cdc.gov/nisvs/documentation/nisvsreportonipv_2022.pdf?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/nisvs/NISVSReportonIPV_2022.pdf}}</ref> Opponents of ] describe it as a human rights violation.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Jacobs |first1=Allan J. |last2=Arora |first2=Kavita Shah |date=2015-02-01 |title=Ritual Male Infant Circumcision and Human Rights |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/15265161.2014.990162 |journal=The American Journal of Bioethics |volume=15 |issue=2 |pages=30–39 |doi=10.1080/15265161.2014.990162 |issn=1526-5161 |pmid=25674955|s2cid=6581063 }}</ref> The ] seeks to support separated fathers that do not receive equal rights to care for their children.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Flood |first=Michael |date=2012-12-01 |title=Separated fathers and the 'fathers' rights' movement |url=https://doi.org/10.5172/jfs.2012.18.2-3.235 |journal=Journal of Family Studies |volume=18 |issue=2–3 |pages=235–345 |doi=10.5172/jfs.2012.18.2-3.235 |s2cid=55469150 |issn=1322-9400 |access-date=4 August 2022 |archive-date=23 October 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221023191114/https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.5172/jfs.2012.18.2-3.235 |url-status=live }}</ref> The ] is the response to issues faced by men in Western countries. It includes ] groups such as the ],<ref>{{Citation | title=Where does Men's Liberation Come From? | date=27 October 2022| url=https://www.nextgenmen.ca/blog/mens-liberation-history-feminism}}</ref> and ] groups such as the ]. | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == Gender symbol == | |||

| '''Medical:''' | |||

| {{main|Gender symbol}} | |||

| *] | |||

| The ] (♂) is a common symbol that represents the male sex.<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Schott|first=G D|date=24 December 2005|title=Sex symbols ancient and modern: their origins and iconography on the pedigree|journal=BMJ: British Medical Journal|volume=331|issue=7531|pages=1509–1510|doi=10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1509|issn=0959-8138|pmc=1322246|pmid=16373733}}</ref> The symbol is identical to the planetary symbol of ].<ref>{{Cite web|title=Solar System Symbols|url=https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/680/solar-system-symbols|access-date=18 August 2021|website=NASA Solar System Exploration|archive-date=20 December 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211220171351/https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/680/solar-system-symbols/|url-status=live}}</ref> It was first used to denote sex by ] in 1751.<ref>{{cite journal |last=Stearn |first=William T. |author-link=William T. Stearn |title=The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols of Biology |journal=] |date=May 1962 |volume=11 |issue=4 |pages=109–113 |url=https://iapt-taxon.org/historic/Congress/IBC_1964/male_fem.pdf |jstor=1217734 |doi=10.2307/1217734 |issn=0040-0262 |quote=Their first biological use is in the Linnaean dissertation {{lang|la|Plantae hybridae xxx sistit J. J. Haartman}} (1751) where in discussing hybrid plants Linnaeus denoted the supposed female parent species by the sign ♀, the male parent by the sign ♂, the hybrid by ☿: '{{lang|la|matrem signo ♀, patrem ♂ & plantam hybridam ☿ designavero}}'. In subsequent publications he retained the signs ♀ and ♂ for male and female individuals but discarded ☿ for hybrids. |access-date=16 August 2022 |archive-date=27 May 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230527105139/https://iapt-taxon.org/historic/Congress/IBC_1964/male_fem.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> The symbol is sometimes seen as a stylized representation of the shield and spear of the ] ]. According to Stearn, however, this derivation is "fanciful" and all the historical evidence favours "the conclusion of the French classical scholar ]" that it is derived from ''{{lang|grc|θρ}}'', the contraction of a Greek ] for Mars, ''{{lang|grc|θοῦρος}}'' (''Thouros'').<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Stearn|first=William T.|date=1962|title=The Origin of the Male and Female Symbols of Biology|url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/1217734|journal=Taxon|volume=11|issue=4|pages=109–113|doi=10.2307/1217734|jstor=1217734|issn=0040-0262|access-date=18 August 2021|archive-date=26 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230326024837/https://www.jstor.org/stable/1217734|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| *], discipline of | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] (social traits of men) | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| == See also == | |||

| '''Dynamics:''' | |||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | * ] | ||

| *] | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| '''Political:''' | |||

| {{Notelist}} | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==References== | == References == | ||

| {{Reflist}} | {{Reflist}} | ||

| == Bibliography == | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * {{Cite book |last=Helgeson |first=Vicki S. |title=Psychology of Gender |publisher=Routledge |year=2017 |isbn=978-1-138-18687-3 |edition=5th}} | |||

| * Andrew Perchuk, Simon Watney, Bell Hooks, ''The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation'', MIT Press 1995 | |||

| == Further reading == | |||

| * Andrew Perchuk, Simon Watney, ], ''The Masculine Masquerade: Masculinity and Representation'', MIT Press 1995 | |||

| * ], ''Masculine Domination'', Paperback Edition, Stanford University Press 2001 | * ], ''Masculine Domination'', Paperback Edition, Stanford University Press 2001 | ||

| * Robert W. Connell, ''Masculinities'', Cambridge : Polity Press, 1995 | * Robert W. Connell, ''Masculinities'', Cambridge : Polity Press, 1995 | ||

| * ], ''The Myth of Male Power'' Berkley Trade, 1993 ISBN |

* ], ''The Myth of Male Power'' Berkley Trade, 1993 {{ISBN|0-425-18144-8}} | ||

| * ] (ed.), Robert W. Connell (ed.), Jeff Hearn (ed.), ''Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities'', Sage Publications 2004 | * ] (ed.), Robert W. Connell (ed.), Jeff Hearn (ed.), ''Handbook of Studies on Men and Masculinities'', Sage Publications 2004 | ||

| ==External links== | == External links == | ||

| {{Wiktionary|man}} | * {{Wiktionary-inline|man}} | ||

| {{Wikiquote}} | * {{Wikiquote-inline}} | ||

| {{Commons|Man|Men}} | * {{Commons-inline|Man|Men}} | ||

| {{Human}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=December 2010}} | |||

| {{Sexual identities}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Masculinism}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 00:32, 10 January 2025

Male adult human For other uses, see Man (disambiguation). "Men" and "Manhood" redirect here. For other uses, see Men (disambiguation) and Manhood (disambiguation).

A man is an adult male human. Before adulthood, a male human is referred to as a boy (a male child or adolescent).

Like most other male mammals, a man's genome usually inherits an X chromosome from the mother and a Y chromosome from the father. Sex differentiation of the male fetus is governed by the SRY gene on the Y chromosome. During puberty, hormones which stimulate androgen production result in the development of secondary sexual characteristics that result in even more differences between the sexes. These include greater muscle mass, greater height, the growth of facial hair and a lower body fat composition. Male anatomy is distinguished from female anatomy by the male reproductive system, which includes the testicles, sperm ducts, prostate gland and epididymides, and penis. Secondary sex characteristics include a narrower pelvis and hips, and smaller breasts and nipples.

Throughout human history, traditional gender roles have often defined men's activities and opportunities. Men often face conscription into military service or are directed into professions with high mortality rates. Many religious doctrines stipulate certain rules for men, such as religious circumcision. Men are over-represented as both perpetrators and victims of violence.

Trans men have a gender identity that does not align with their female sex assignment at birth, while intersex men may have sex characteristics that do not fit typical notions of male biology.

Etymology

Further information: Man (word), boy, father, husband, son, godparent, gentleman, and widowerThe English term "man" is derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *man- (see Sanskrit/Avestan manu-, Slavic mǫž "man, male"). More directly, the word derives from Old English mann. The Old English form primarily meant "person" or "human being" and referred to men, women, and children alike. The Old English word for "man" as distinct from "wif"/"woman" or "child" was wer. Mann only came to mean "man" in Middle English, replacing wer, which survives today only in the compounds "werewolf" (from Old English werwulf, literally "man-wolf"), and "wergild", literally "man-payment".

Biology

Main article: Sex differences in humans

In humans, sperm cells carry either an X or a Y sex chromosome. If a sperm cell carrying a Y chromosome fertilizes the female ovum, the offspring will have a male karyotype (XY). The SRY gene is typically found on the Y chromosome and causes the development of the testes, which in turn govern other aspects of male sex differentiation. Sex differentiation in males proceeds in a testes-dependent way while female differentiation is not gonad dependent.

Primary sex characteristics (or sex organs) are characteristics that are present at birth and are integral to the reproductive process. For men, primary sex characteristics include the penis and testicles.

Adult humans exhibit sexual dimorphism in many other characteristics, many of which have no direct link to reproductive ability. Humans are sexually dimorphic in body size, body structure, and body composition. Men tend to be taller and heavier than women, and adjusted for height, men tend to have greater lean and bone mass than women, and lower fat mass.

Secondary sex characteristics are features that appear during puberty in humans. Such features are especially evident in the sexually dimorphic phenotypic traits that distinguish between the sexes, but—unlike the primary sex characteristics—are not directly part of the reproductive system. Secondary sexual characteristics that are specific to men include:

- Broadened shoulders;

- Increased body hair;

- An enlarged larynx (also known as an Adam's apple); and

- A voice that is significantly deeper than the voice of a child or a woman.

Men weigh more than women. On average, men are taller than women by about 10%. On average, men have a larger waist in comparison to their hips (see waist–hip ratio) than women. In women, the index and ring fingers tend to be either more similar in size or their index finger is slightly longer than their ring finger, whereas men's ring finger tends to be longer.

Reproductive system

Main article: Male reproductive system

The internal male genitalia consist of the testicles, gonads that produce male gametes called sperm, the prostate, seminal vesicles, and bulbourethral glands, accessory glands that partake in sperm health, the epididymides, organs that store sperm cells, and the vasa deferentia and ejaculatory ducts, tubular structures that transfer the mature sperm to the urethra.

The external male genitalia consist of the penis, an organ that expels semen, and the scrotum, a pouch of skin housing the testicles.

The male reproductive system's function is to produce semen, which carries sperm and thus genetic information that can unite with an egg within a woman. Since sperm that enters a woman's uterus and then fallopian tubes goes on to fertilize an egg which develops into a fetus or child, the male reproductive system plays no necessary role during the gestation. The study of male reproduction and associated organs is called andrology.

Testosterone stimulates the development of the Wolffian ducts, the penis, and closure of the labioscrotal folds into the scrotum. Another significant hormone in sexual differentiation is the anti-Müllerian hormone, which inhibits the development of the Müllerian ducts. For males during puberty, testosterone, along with gonadotropins released by the pituitary gland, stimulates spermatogenesis.

Health