| Revision as of 15:18, 9 August 2012 edit88.241.111.18 (talk)No edit summary← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 05:27, 7 December 2024 edit undoSumanuil (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users82,619 edits →Gallery: These are file names.\ | ||

| (995 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{ |

{{Short description|Turkic people in Inner Asia}} | ||

| {{for| empires established by the Gökturks|First Turkic Khaganate|Western Turkic Khaganate|Eastern Turkic Khaganate|Second Turkic Khaganate}} | |||

| {{Multiple issues|cleanup=October 2010|POV=October 2010}} | |||

| {{other uses| Göktürk (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Infobox Former Country | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=April 2024}} | |||

| |common_name = Turkic Khaganate | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| |native_name = Göktürks | |||

| | group = Gökturks | |||

| |conventional_long_name = Turkic Khaganate | |||

| | image = ] | |||

| |continent = Asia | |||

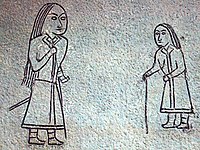

| | caption = Gökturk petroglyphs from modern Mongolia (6th to 8th century).<ref name="Altınkılıç">{{cite journal |last1=Altınkılıç |first1=Arzu Emel |title= Göktürk giyim kuşamının plastik sanatlarda değerlendirilmesi |journal= Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research |date= 2020 |pages= 1101–1110 |url= http://www.jshsr.org/Makaleler/1429516422_07-7-53.1853-1101-1110.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201024185201/http://www.jshsr.org/Makaleler/1429516422_07-7-53.1853-1101-1110.pdf |archive-date=24 October 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |region = Central Asia | |||

| | pop = Ancestral to some Turkic populations | |||

| |status = ] | |||

| | |

| regions = ] and ] | ||

| | languages = ]<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lloyd |first1=Keith |title=The Routledge Handbook of Comparative World Rhetorics: Studies in the History, Application, and Teaching of Rhetoric Beyond Traditional Greco-Roman Contexts |date=10 June 2020 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1-000-06627-2 |page=153 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=MvDqDwAAQBAJ&pg=PT153}}</ref> | |||

| |common_languages =] | |||

| | religions = ], ] | |||

| |year_start = 552 | |||

| | related = ], ], ], ], ]<ref>Xiu Ouyang, (1073), ''Historical Records of the Five Dynasties'', p. 39</ref> | |||

| |year_end = 744 | |||

| | native_name = 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣<br/>Türük Bodun | |||

| |p1 = Rouran Khaganate | |||

| | native_name_lang = otk | |||

| |flag_p1 = | |||

| |s1 = Uyghur Khaganate | |||

| |s2 = Turgesh | |||

| |s3 = Western Turkic Khaganate | |||

| |flag_s1 = | |||

| |image_map = GökturksAD551-572.png | |||

| |image_map_caption = The Turkic Khaganate (green) in its earliest years. | |||

| |image_flag = | |||

| |flag_s1 = | |||

| |religion = ] | |||

| |currency = | |||

| |legislature = ] ''(Qurultay)'' | |||

| |title_leader = ] | |||

| |leader1 = ] | |||

| |year_leader1 = 551–553 | |||

| |leader2 = ] | |||

| |year_leader2 = 553–576 | |||

| |stat_year1 = 557 | |||

| |stat_area1 = 6000000 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| The '''Göktürks''', '''Türks''', '''Celestial Turks''' or '''Blue Turks''' ({{langx|otk|𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣|Türük Bodun}}; {{zh|c=突厥|p=Tūjué|w=T'u-chüeh}}) were a ] in medieval ]. The Göktürks, under the leadership of ] (d. 552) and his sons, succeeded the ] as the main power in the region and established the ], one of several nomadic dynasties that would shape the future geolocation, culture, and dominant beliefs of ]. | |||

| {{History of Mongolia}} | |||

| {{History of Kazakhstan}} | |||

| The '''Göktürks''' or '''Kök Türks''' (Celestial Turks) were a nomadic confederation of ] in medieval ]. The Göktürks, under the leadership of ] (d. 552) and his sons, succeeded the ] as the main power in the region and took hold of the lucrative ] trade. Gök means ''Sky'' in modern Turkish. | |||

| The Göktürks became the new leading element amongst the disparate steppe peoples in ], after they rebelled against the Rouran Khaganate. Under their leadership, the Turkic Khaganate rapidly expanded to rule huge territories in Central Asia. From 552 to 745, Göktürk leadership bound together the ]ic Turkic tribes into an empire, which eventually collapsed due to a series of dynastic conflicts.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| ===Origin=== | |||

| ]s from ], ], depicting Göktürks (6th–8th century).]] | |||

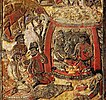

| ], circa 570.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Mierse |first1=William E. |title=Artifacts from the Ancient Silk Road |date=1 December 2022 |publisher=ABC-CLIO |isbn=978-1-4408-5829-1 |page=126 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=WQuXEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA126 |language=en}} "In the upper scene, long-haired Turkic servants attend an individual seated inside the yurt proper, and in the lower scene, hunters are seen riding down game. The setting must be the Kazakh steppes over which the Turks had taken control from the Hepthalites." | |||

| The ] name was ]]]] Türük,<ref name="KulteginMC"> ] {{En icon}}</ref><ref name="BilgeKaganMC"> Khöshöö Tsaidam Monuments {{En icon}}</ref> ]]]] ]]] Kök Türük,<ref name="KulteginMC"/><ref name="BilgeKaganMC"/> or ]]]] Türük.<ref name="TonyukukMC"> ] {{En icon}}</ref> | |||

| </ref>]] | |||

| The common name "Göktürk" emerged from the misreading of the word "Kök" meaning ], the endonym of the ruling clan of the historical ethnic group which was attested as {{langx|otk|𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜|Türük|label=none}}<ref name="KulteginMC"> ]</ref><ref name="BilgeKaganMC">{{Cite web|url=https://kaznpu.kz/kz/|title=Абай атындағы Қазақ ұлттық педагогикалық университеті|website=kaznpu.kz}}</ref> {{langx|otk|𐰚𐰇𐰜:𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜|Kök Türük|label=none}},<ref name="KulteginMC"/><ref name="BilgeKaganMC"/> or {{langx|otk|𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚|Türk}}.<ref name="TonyukukMC"> ]</ref> It is generally accepted that the name ''Türk'' is ultimately derived from the ] migration-term<ref>(Bŭlgarska akademii︠a︡ na naukite. Otdelenie za ezikoznanie/ izkustvoznanie/ literatura, Linguistique balkanique, Vol. 27–28, 1984, p. 17</ref> 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜 ''Türük''/''Törük'', which means 'created, born'.<ref>Faruk Sümer, Oghuzes (Turkmens): History, Tribal organization, Sagas, Turkish World Research Foundation, 1992, p. 16)</ref> | |||

| They were known in ] historical sources as the ''Tūjué'' ({{zh|t=] ]}}; reconstructed in ] as romanized: *''dwət-kuɑt'' > ''tɦut-kyat'').{{sfn|Golden|2011|p=20}} | |||

| They were known in historical ] sources as ]] (]: Tūjué, ]: T'u-chüeh, ] ]: dʰuət-kĭwɐt). According to Chinese sources, the meaning of the word ''Tūjué'' was "]" (]]; ]: dōumóu, ]: tou-mou), reportedly because the shape of the Jinshan (金山 jīnshān, ]), where they lived, was similar to a combat helmet - hence they called themselves 突厥 (Tūjué / T'u-chüeh).<ref name="Zhou50">] et al., '']'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref name="Sui84">] et al., '']'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref name="Northern99">], '']'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> | |||

| The ethnonym was also recorded in various other Middle Asian languages, such as ] *''Türkit ~ Türküt'', ''tr'wkt'', ''trwkt'', ''turkt'' > ''trwkc'', ''trukč''; ] ''Ttūrka''/''Ttrūka'', ] ''to̤ro̤x''/''türǖg'', ] ''''/''Dolgwol'', and ] ''Drugu''.{{sfn|Golden|2011|p=20}}{{sfn|Golden|2018|p=292}} | |||

| Göktürks is said to mean "Celestial Turks".<ref> {{En icon}}</ref> This is consistent with "the cult of heavenly ordained rule" which was a pivotal element of the Altaic political culture and were inherited by the Göktürks from their predecessors in Mongolia.<ref>Wink 64.</ref> Similarly, the name of the ruling Ashina clan possibly derives from the ] ] term for "deep blue", ''āššɪna''.<ref>Findley 39.</ref> The name might also derive from a ] tribe related to '']''.<ref>Zhu 68-91.</ref> | |||

| ===Definition=== | |||

| The word Türk meant "strong" in ].<ref>{{cite web|url = http://www.bartleby.com/61/92/T0419200.html |title=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition - "Turk"|author=American Heritage Dictionary|authorlink=American Heritage Dictionary|publisher=bartleby.com|accessdate=2006-12-07|year=2000}}</ref> | |||

| According to Chinese sources, Tūjué meant "]" ({{zh|c=] ]|p=Dōumóu|w=Tou<sup>1</sup>-mou<sup>2</sup>}}), reportedly because the shape of the ], where they lived, was similar to a combat helmet.<ref name="Zhou50">] et al., '']'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref name="Sui84">] et al., '']'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref name="Northern99">] (李延寿), '']'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref> ] (1991) pointed to a ] word, ''tturakä'' "lid", semantically stretchable to "helmet", as a possible source for this folk etymology, yet Golden thinks this connection requires more data.<ref name="Golden2006">{{cite journal|last = Golden|first= Peter B.|title= Türks and Iranians: Aspects of Türk and Khazaro-Iranian Interaction|journal= Turcologica|issue= 105|page= 25}}</ref> | |||

| Göktürk is sometimes interpreted as either "Celestial Turk" or "Blue Turk" (i.e. because ] is associated with ]).{{sfn|West|2008|p=829}} This is consistent with "the cult of heavenly ordained rule" which was a recurrent element of Altaic political culture and as such may have been imbibed by the Göktürks from their predecessors in Mongolia.<ref>Wink 64.</ref> "Blue" is traditionally associated with the East as it used in the ] of central Asia, thus meaning "Turks of the East".{{sfn|Golden|1992|pages=133-134,136}} The name of the ruling ] may derive from the ] term for "deep blue", ''āššɪna''.{{sfn|Findley|2004|p=39}} | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| The Göktürk rulers originated from the ] clan, a tribe of obscure origins who lived in the northern corner of Inner Asia. | |||

| According to the ], the word Türk meant "strong" in Old Turkic;<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.bartleby.com/61/92/T0419200.html|title=The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition – "Turk"|author=American Heritage Dictionary|author-link=American Heritage Dictionary|publisher=bartleby.com|access-date=7 December 2006|year=2000|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070116043608/http://www.bartleby.com/61/92/T0419200.html|archive-date=16 January 2007}}</ref> though ] supports this theory, ] points out that "the word '''Türk''' is never used in the generalized sense of 'strong'" and that the noun '''Türk''' originally meant "'the culminating point of maturity' (of a fruit, human being, etc.), but more often used as an meaning (of a fruit) 'just fully ripe'; (of a human being) 'in the prime of life, young, and vigorous'".<ref>{{cite book |last=Clauson |first=G. |title=An Etymological Dictionary of Pre-13th Century Turkish |location=Oxford |publisher=Clarendon Press |year=1972 |pages=542–543 |isbn=0-19-864112-5 }}</ref> Hakan Aydemir (2022) also contends that '''Türk''' originally did not mean "strong, powerful" but "gathered; united, allied, confederated" and was derived from Pre-] verb *'''türü''' "heap up, collect, gather, assemble".<ref>{{cite book|first= Hakan|last= Aydemir|date= 2–3 December 2022|chapter= TÜRK Adının Kökeni Üzerine (On the origin of the ethnonym TÜRK 'Turkic, Turkish') + an English abstract|title= Türk Dunyası Sosyal Bilimler - Sempozyumu|publisher= Ege University|location= İzmir|editor-last1= Şahin|editor-first1= İbrahim|editor-last2= Akgün|editor-first2= Atıf|chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/100924309|language= tr}}</ref> | |||

| According to '']'' and '']'', Ashina was a branch of ]s<ref name="Zhou50"/><ref name="Northern99"/> and according to '']'' and '']'', they were "mixed Barbarians" (]] / 杂胡, Pinyin: zá hú, Wade-Giles: tsa hu) from ].<ref name="Sui84"/><ref name="Tong197">杜佑, 《通典》, 北京: 中華書局出版, (], '']'', Vol.197), 辺防13 北狄4 突厥上, 1988, ISBN 7-101-00258-7, p. 5401. {{Zh icon}}</ref> ''Book of Sui'' reported that when ] of ] overthrew ]'s ] on October 18, 439,<ref>], '']'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref>], '']'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref>]七年 (]五年) 九月丙戌 {{Zh icon}}</ref> Ashina's 500 families fled to the Rouran Khaganate.<ref name="Sui84"/> Within the heterogeneous Rouran Khaganate, the Göktürks lived north of the ] for generations, they were engaged in metal-works.<ref name="Sui84"/><ref name="Zizhi159">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> According to ], their rise to power represented an 'internal revolution' in the confederacy, rather than an external conquest.<ref>Denis Sinor, "The Establishment and Dissolution of the Turk Empire", ''The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia'', {{En icon}}</ref> According to Charles Holcombe, the early Tujue population was rather heterogeneous and many of the names of Göktürk rulers are not even Turkic.<ref>Charles Holcombe, ''The Genesis of East Asia, 221 B.C.-A.D. 907'', University of Hawaii Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8248-2465-5, </ref> | |||

| The name as used by the Göktürks only applied to themselves, the Göktürk khanates, and their subjects. The Göktürks did not consider other Turkic speaking groups such as the ], ], and ] to be Türks. In the ], the ] and the ] are not referred to as Türks. Similarly, the Uyghurs called themselves Uyghurs and used ''Türk'' exclusively for the Göktürks, whom they portrayed as enemy aliens in their royal inscriptions. The ] may have kept the Göktürk tradition alive by claiming descent from the Ashina. When tribal leaders built their khanates, ruling over assorted tribes and tribal unions, the collected people identified themselves politically with the leadership. Turk became the designation for all subjects of the Turk empires. Nonetheless, subordinate tribes and tribal unions retained their original names, identities, and social structures. Memory of the Göktürks and the Ashina had faded by the turn of the millennium. The ], ] Uyghurs, and ] did not claim descent from the Göktürks.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=Joo-Yup |title=Some remarks on the Turkicisation of the Mongols in post-Mongol Central Asia and the Qipchaq Steppe |journal=Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae |date=2018 |volume=71 |issue=2 |pages=128–129 |doi=10.1556/062.2018.71.2.1 |s2cid=133847698 |url=https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=666361 |language=English |issn=0001-6446}}</ref><ref>Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples". Inner Asia. Brill. 19 (2): p. 203 of 197–239.</ref><ref>Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors, Page 34</ref> | |||

| ==First khaganate== | |||

| The Göktürks rise to power began in 546 when ] made a pre-emptive strike against the ] and ] tribes who were planning a revolt against their overlords, the Rouran. For this service he expected to be rewarded with a Rouran princess, ''i.e.'' marry into the royal family. However Rouran kaghan ] sent an emissary to Bumin to rebuke him, saying, "You are my blacksmith slave. How dare you utter these words?". As Anagui's "blacksmith slave" (]] / 锻奴, Pinyin: duànnú, Wade-Giles: tuan-nu) comment was recorded in Chinese chronicles, some claim that the Göktürks were indeed blacksmith servants for the Rouran elite,<ref>馬長壽, 《突厥人和突厥汗國》, 上海人民出版社, 1957,p. 10-11 {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref>陳豐祥, 余英時, 《中國通史》, 五南圖書出版股份有限公司, 2002, ISBN 978-957-11-2881-8, p. 155 {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref> {{En icon}}</ref><ref>Burhan Oğuz, ''Türkiye halkının kültür kökenleri: Giriş, beslenme teknikleri'', İstanbul Matbaası, 1976, p. 147. {{Tr icon}}</ref> and that "blacksmith slavery" may indicate a kind of vassalage system prevailed in Rouran society.<ref>Larry W. Moses, "Relations with the Inner Asian Barbarian", ed. John Curtis Perry, Bardwell L. Smith, ''Essays on Tʻang society: the interplay of social, political and economic forces'', Brill Archive, 1976, ISBN 978-90-04-04761-7, p. 65. {{En icon}}</ref> According to ], this reference indicates that the Göktürks were specialized in metallurgy, though it is unclear if they were miners or, indeed, blacksmiths.<ref name="Denis26">Denis Sinor, Inner Asia: history-civilization-languages : a syllabus, Routledge, 1997, ISBN 978-0-7007-0380-7, p. 26. Contacts had already begun in 545 A.D. between the so-called "blacksmith-slave" Türk and certain of the small petty kingdom of north China,</ref><ref>Denis Sinor, ''ibid'', p. 101. {{En icon}}</ref> | |||

| == History == | |||

| Disappointed in his hopes, Bumin allied with the ] state against Rouran, their common enemy. In 552 (February 11 – March 10, 552), Bumin defeated the Rouran Khan Anagui in north of ] (in present day ], ]).<ref name="Zhou50"/> | |||

| === Origins === | |||

| Having excelled both in battle and diplomacy Bumin declared himself Illig ] of the new khaganate at ] but died a year later. His son ] defeated the ] (厭噠),<ref>Li Yanshou, '']'', ]</ref> ] (契丹) and ] (契骨).<ref>Sima Guang, '']'', ]</ref> Bumin's brother ] (d. 576) was titled ''yabghu of the west'' and collaborated with the ]n ]s to defeat and destroy the Hephthalite, who were allies of the Rouran. This war tightened the Ashina's grip of the Silk Road and drove the ] into Europe.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| {{See also|Timeline of the Göktürks}} | |||

| ] region, 5th-6th century AD<ref>{{cite web |last1=Konstantinov |first1=Nikita |last2=Soenov |first2=Vasilii |last3=Черемисин |first3=Дмитрий |title=BATTLE AND HUNTING SCENES IN TURKIC ROCK ART OF THE EARLY MIDDLE AGES IN ALTAI |url=https://www.academia.edu/29773396}}</ref>]] | |||

| ], 579 CE).<ref name="REF1">{{cite book |last1=Baumer |first1=Christoph |title=History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set |date=18 April 2018 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-1-83860-868-2 |page=228 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DhiWDwAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA228 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="SYET">{{cite journal |last1=Yatsenko |first1=Sergey A. |title=Early Turks: Male Costume in the Chinese Art |journal=Transoxiana |date=August 2009 |volume=14 |url=http://www.transoxiana.com.ar/14/yatsenko_turk_costume_chinese_art.html}}</ref>]] | |||

| The Göktürk rulers originated from the ], who were first attested to in 439. The '']'' reports that in that year, on 18 October, the ] ruler ] overthrew ] of the ] in eastern ],<ref>], '']'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref>], '']'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref><ref>]七年 (]五年) 九月丙戌 {{in lang|zh}} {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131016003621/http://sinocal.sinica.edu.tw/ |date=16 October 2013 }}</ref> whence 500 Ashina families fled northwest to the ] in the vicinity of ].<ref name="Sui84" />{{sfn|Christian|1998|p=249}} | |||

| According to the '']'' and '']'', the Ashina clan was a component of the ] confederation,<ref name="Zhou50" /><ref name="Northern99" /> specifically, the Northern Xiongnu tribes<ref>'']'', vol. 215 upper. "突厥阿史那氏, 蓋古匈奴北部也." "The Ashina family of the Turk probably were the northern tribes of the ancient Xiongnu." translated by Xu (2005)</ref><ref>Xu Elina-Qian, , ], 2005</ref> or southern Xiongnu "who settled along the northern Chinese frontier", according to ].{{sfn|Golden|2018|p=306}} However, this view is contested.{{sfn|Christian|1998|p=249}} Göktürks were also posited as having originated from an obscure Suo state (索國) (]: *''sâk'') which was situated north of the ] and had been founded by the ]<ref>], (1999), "A türkök eredetmondája", ''Magyar Nyelv'', vol. 95(4): p. 391 of 385–396. cited in Golden (2018), "The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks", p. 300</ref> or ].<ref>Vásáry, István (2007) ''Eski İç Asya Tarihi'' p. 99-100, cited Golden (2018), "The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks", p. 300</ref><ref name="Zhou50" /><ref name="Northern99" />{{sfn|Golden|2018|p=300}} According to the ''Book of Sui'' and the '']'', they were "mixed Hu (barbarians)" ({{linktext|雜胡}}) from ] (平涼), now in ], ].<ref name="Sui84" /><ref name="Tong197">杜佑, 《通典》, 北京: 中華書局出版, (], '']'', Vol.197), 辺防13 北狄4 突厥上, 1988, {{ISBN|7-101-00258-7}}, p. 5401. {{in lang|zh}}</ref> Pointing to the Ashina's association with the Northern tribes of the ], some researchers (e.g. Duan, Lung, etc.) proposed that Göktürks belonged in particular to the ], likewise Xiongnu-associated,<ref name="Sui84" /> by ancestral lineage.<ref>{{cite book |first=Rachel |last=Lung |title=Interpreters in Early Imperial China |publisher=John Benjamins |year=2011 |page=48 |isbn=978-90-272-2444-6 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |author=Duan |title=Dingling, Gaoju and Tiele |year=1988 |pages=39–41 |publisher=] |isbn=7-208-00110-3 }}</ref> However, Lee and Kuang (2017) state that Chinese sources do not describe the Ashina-led Göktürks s descending from the Dingling or belonging to the Tiele confederation.<ref>Lee, Joo-Yup; Kuang, Shuntu (18 October 2017). "A Comparative Analysis of Chinese Historical Sources and Y-DNA Studies with Regard to the Early and Medieval Turkic Peoples". Inner Asia. Brill. 19 (2): p. 201 of 197–239.</ref> | |||

| Istämi's policy of western expansion brought the Göktürks into Eastern Europe.{{Citation needed|date=October 2010}} In 576 the Göktürks crossed the ] into the ]. Five years later they laid siege to ]; their cavalry kept roaming the steppes of Crimea until 590.<ref name="Grousset81">Grousset 81.</ref> As for the southern borders, they were drawn south of the ] (Oxus), bringing the Ashina into conflict with their former allies, the Sassanids of Persia. Much of ] (including ]) remained a dependency of the Ashina until the end of the century.<ref name="Grousset81"/> | |||

| Chinese sources linked the ] on their northern borders to the Xiongnu just as Graeco-Roman historiographers called the ], ] and ] "]". Such archaizing was a common literary topos, implying similar geographic origins and nomadic lifestyle but not direct filiation.{{sfn|Sinor|1990}}{{page needed|date=August 2015}} | |||

| ==Civil war== | |||

| {{Main|Göktürk civil war}} | |||

| [[Image:Gokturkut.png|300px|thumb|left|Turkic khaganates at their height, c. 600 CE : | |||

| {{Legend|purple|Western Gokturk: Lighter area is direct rule, darker areas show sphere of influence.}} | |||

| {{Legend|blue|Eastern Gokturk: Lighter area is direct rule, darker areas show sphere of influence.}}]] | |||

| This first{{citation needed|date=May 2012}} Turkic Khaganate split in two after the death of the fourth Qaghan, ] (ca. 584). He had willed the title Qaghan to Muqan's son ],<!--阿史那大邏便/阿史那大逻便, āshǐnà dàluóbiàn---> but the high council appointed ] in his stead. Factions formed around both leaders. Before long four rival qaghans claimed the title of Qaghan. They were successfully played off against each other by the ] and ] of China.{{Citation needed|date=April 2009}} | |||

| As part of the heterogeneous ], the Turks lived for generations north of the ], where they 'engaged in metal working for the Rouran'.<ref name="Sui84" /><ref name="Zizhi159">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref> According to ], the rise to power of the Ashina clan represented an 'internal revolution' in the Rouran Khaganate rather than an external conquest.{{sfn|Sinor|1990|p=295}} | |||

| The most serious contender was the Western qaghan, Istämi's son ], a violent and ambitious man who had already declared himself independent from the Qaghan after his father's death. He now titled himself as Qaghan, and led an army to the east to claim the seat of imperial power, Ötüken.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| According to Charles Holcombe, the early Turk population was rather heterogeneous and many of the names of Turk rulers, including the two founding members, are not even Turkic.{{sfn|Holcombe|2001|p=114}} This is supported by evidence from the ], which include several non-Turkic lexemes, possibly representing ] or ] words.{{sfn|Sinor|1990|p=291}}<ref>Vovin, Alexander. "Did the Xiongnu speak a Yeniseian language?". Central Asiatic Journal 44/1 (2000), pp. 87–104.</ref> ] points out that the khaghans of the Turkic Khaganate, the Ashina, who were of an undetermined ethnic origin, adopted ] and Tokharian (or non-]) titles.{{sfn|Golden|1992|p=126}} German Turkologist W.-E. Scharlipp points out that many common terms in Turkic are ] in origin.<ref>{{cite book |quote=(...) Über die Ethnogenese dieses Stammes ist viel gerätselt worden. Auffallend ist, dass viele zentrale Begriffe iranischen Ursprungs sind. Dies betrifft fast alle Titel (...). Einige Gelehrte wollen auch die Eigenbezeichnung türk auf einen iranischen Ursprung zurückführen und ihn mit dem Wort "Turan", der persischen Bezeichnung für das Land jeneseits des Oxus, in Verbindung bringen. |first=Wolfgang-Ekkehard |last=Scharlipp |title=Die frühen Türken in Zentralasien |location=Darmstadt |publisher=Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft |year=1992 |isbn=3-534-11689-5 |page=18 }}</ref> Whatever language the Ashina may have spoken originally, they and those they ruled would all speak Turkic, in a variety of dialects, and create, in a broadly defined sense, a common culture.{{sfn|Golden|1992|p=126}}<ref>], (1967), ''Drevnie Turki'' (Ancient Turks), p. 22-25</ref> | |||

| In order to buttress his position, Ishbara of the Eastern Khaganate applied to the Chinese Emperor ] for protection. Tardu attacked ], the Sui capital, around 600, demanding from Emperor Yangdi to end his interference in the civil war. In retaliation, Chinese diplomacy successfully incited a revolt of Tardu's Tiele vassals, which led to the end of Tardu's reign in 603. Among the dissident tribes were the ] and ].{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| ===Expansion=== | |||

| ==Eastern Turkic Khaganate== | |||

| {{Main|First Turkic Khaganate}} | |||

| The civil war left the empire divided into eastern and western parts. The eastern part, still ruled from Ötüken, remained in the orbit of the Sui Empire and retained the name Göktürk. The qaghans ] (609-19) and ] (620-30) of the East attacked China at its weakest moment during the transition between the Sui and Tang dynasties. On September 11, 615<ref>]十一年 八月癸酉 {{Zh icon}}</ref> Shibi Qaghan's army surrounded ] of ] at ] (in present day ], ], ]).<ref name="Zizhi182">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> | |||

| {{Asia 576 CE|right|The First Turkic Khaganate and contemporary polities, circa 576||Map of the First Turkic Khaganate.png}} | |||

| The Göktürks reached their peak in the late 6th century and began to invade the ]. However, the war ended due to the division of Turkic nobles and their civil war for the throne of Khagan. With the support of ], ] won the competition. However, the Göktürk empire was divided to Eastern and Western empires. Weakened by the civil war, Yami Qaghan declared allegiance to the Sui dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Book of Sui 隋書 Vol. 2 Vol. 51 & Vol.84|last=Wei 魏|first=Zheng 徵|year=656}}</ref> When Sui began to decline, ] began to assault its territory and even surrounded ] in Siege of Yanmen (615 AD) with 100,000 cavalry troops. After the collapse of the Sui dynasty, the Göktürks intervened in the ensuing Chinese civil wars, providing support to the northeastern rebel ] against the rising ] in 622 and 623. Liu enjoyed a long string of success but was finally routed by ] and other Tang generals and executed. The ] was then established.{{citation needed|date=November 2022}} | |||

| === Conquest by the Tang === | |||

| In 626, Illig Qaghan took advantage of the ] and drove on ]. On September 23, 626<ref>]九年 八月癸未 {{Zh icon}}</ref> Illig Qaghan and his iron cavalries reached the bank of the ] at the north of Bian Bridge (in present day ], ]). On September 25, 626<ref>]九年 八月乙酉 {{Zh icon}}</ref> ] (Emperor Taizong) and Illig Qaghan formed an alliance with slaying a white horse on Bian Bridge. Tang paid compensation and promise further tributes, Illig Qaghan ordered to withdraw their iron cavalries (Alliance of Wei River, 渭水之盟 or Alliance of Bian Qiao 便橋會盟 / 便桥会盟).<ref name="Zizhi191">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> All in all, 67 incursions on Chinese territories were recorded.<ref name="Grousset81"/> | |||

| {{Main|Tang dynasty in Inner Asia}} | |||

| Although the Göktürk Khaganate once provided support to the Tang dynasty in the early period of the civil war during the collapse of the ], the conflicts between the Göktürks and Tang finally broke out when Tang was gradually reunifying ]. The Göktürks began to attack and raid the northern border of the Tang Empire and once marched their main force of 100,000 soldiers to ], the capital of Tang. The emperor Taizong of the Tang, in spite of the limited resources at his disposal, managed to turn them back. Later, Taizong sent his troops to Mongolia and defeated the main force of Göktürk army in ] four years later and captured ] in 630 AD.<ref name="Liu 劉">{{Cite book|title=Old book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.2 & Vol. 67|last=Liu 劉|first=Xu 昫|year=945}}</ref> With the submission of the Turkic tribes, the Tang conquered the ]. From then on, the Eastern Turks were subjugated to China.<ref name="Liu 劉"/> | |||

| Before mid-October 627 heavy snows on the ] covered the ground to a depth of several feet, preventing the nomads' livestock from grazing and causing a massive dying-off among the animals.<ref>David Andrew Graff, ''Medieval Chinese warfare, 300-900'', Routledge, 2002, ISBN 978-0-415-23955-4, </ref> According to the ''New Book of Tang'', in 628, Taizong mentioned that "There has been a frost in midsummer. The sun had risen from same place for five days. The moon had had the same light level for three days. The field was filled with red atmosphere (dust storm)."<ref>Ouyang Xiu, ''New Book of Tang'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> | |||

| After a vigorous court debate, ] decided to pardon the Göktürk nobles and offered them positions as imperial guards.<ref name=":0">{{Cite book|title=Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.2 & Vol.194|last=Liu 劉|first=Xu 昫|year=945}}</ref> However, the proposition was ended by a plan for the assassination of the emperor. On 19 May 639<ref>]十三年 四月戊寅 {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100522200011/http://db1x.sinica.edu.tw/sinocal/ |date=22 May 2010 }} {{in lang|zh}}</ref> ] and his tribesmen directly assaulted Emperor Taizong of Tang at Jiucheng Palace ({{linktext|九|成|宮}}, in present-day ], ], ]). However, they did not succeed and fled to the north, but were caught by pursuers near the ] and were killed. Ashina Hexiangu was exiled to ].<ref name="Zizhi195">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref> After the unsuccessful raid of ], on 13 August 639<ref>]十三年 七月庚戌 {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100522200011/http://db1x.sinica.edu.tw/sinocal/ |date=22 May 2010 }} {{in lang|zh}}</ref> Taizong installed ] and ordered the settled Turkic people to follow him north of the ] to settle between the ] and the ].<ref>Ouyang Xiu et al., ''New Book of Tang'', ]</ref> However, many Göktürk generals still remained loyal in service to the Tang Empire. | |||

| Illig Qaghan was brought down by a revolt of his Tiele vassal tribes (626-630), allied with ]. This tribal alliance figures in Chinese records as the Huihe (Uyghur).{{Citation needed|date=October 2010}} | |||

| ] (684–731) found in ], ], ] valley. Located in the ].]] | |||

| On March 27, 630<ref>]四年 二月甲辰 {{Zh icon}}</ref> a Tang army under the command of ] defeated the Eastern Turkic Khaganate under the command of Illig Qaghan at the ] (陰山之戰 / ]).<ref>]'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref name="NewTang93">] et al., '']'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref><ref name="Zizhi193">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> Illig Qaghan fled to Ishbara Shad. But on May 2, 630<ref>]四年 三月庚辰</ref> ]'s army got advance to Ishbara Shad's headquarter. Illig Qaghan was taken prisoner and sent to Chang'an.<ref name="Zizhi193"/> The Eastern Turkic Khaganate collapsed and was incorporated into the ] of Tang. ] said that "It's enough for me to compensate my dishonor at Wei River."<ref name="NewTang93"/> | |||

| ===Revival=== | |||

| ==Western Turkic Khaganate== | |||

| {{ |

{{main|Second Turkic Khaganate}} | ||

| In 679, ] Wenfu and Ashide Fengzhi, who were Turkic leaders of the Chanyu Protectorate (]), declared ] as qaghan and revolted against the Tang dynasty.<ref name="Zizhi202">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref> In 680, ] defeated Ashina Nishufu and his army. Ashina Nishufu was killed by his men.<ref name="Zizhi202" /> Ashide Wenfu made ] a qaghan and again revolted against the Tang dynasty.<ref name="Zizhi202" /> Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian surrendered to Pei Xingjian. On 5 December 681,<ref>]元年 十月乙酉 {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100522200011/http://db1x.sinica.edu.tw/sinocal/ |date=22 May 2010 }} {{in lang|zh}}</ref> 54 Göktürks, including Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian, were publicly executed in the Eastern Market of ].<ref name="Zizhi202" /> In 682, ] and ] revolted and occupied Heisha Castle (northwest of present-day ], ]) with the remnants of Ashina Funian's men.<ref>Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{in lang|zh}}</ref> The restored Göktürk Khaganate intervened in the war between Tang and Khitan tribes.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol. 6 & Vol.194|last=Liu 劉|first=Xu 昫|year=945}}</ref> However, after the death of Bilge Qaghan, the Göktürks could no longer subjugate other Turk tribes in the grasslands. In 744, allied with the Tang dynasty, the ] defeated the last Göktürk Khaganate and controlled the Mongolian Plateau.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Old Book of Tang 舊唐書 Vol.103,Vol.194 & Vol.195|last=Liu 劉|first=Xu 昫|year=945}}</ref> | |||

| {{see|Third Perso-Turkic War}} | |||

| The Western qaghan ] and ] constructed an alliance with the ] against the Persian ] and succeeded in restoring the southern borders along the ] and Oxus rivers. Their capital was ] in the ] valley, about 6 km south east of modern ]. In 627 Tung Yabghu, assisted by the ] and ], launched a massive invasion of ] which culminated in the taking of ] and ] (see the ] for details). In April 630 Tung's deputy ] sent the Göktürk cavalry to invade ], where his general ] succeeded in routing a large Persian force. Tung Yabghu's murder in 630 forced the Göktürks to evacuate Transcaucasia.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| ==Rulers== | |||

| The Western Turkic Khaganate was modernized through an administrative reform of ] (reigned 634–639) and came to be known as the ''Onoq''.<ref name="Gumilev">Gumilev 238.</ref> The name refers to the "ten arrows" that were granted by the khagan to five leaders (''shads'') of its two constituent tribal confederations, ] and ], whose lands were divided by the Chui River.<ref name="Gumilev"/> The division fostered the growth of separatist tendencies, and soon the ] under the Dulo chieftain ] seceded from the khaganate. In 657, the eastern part of the khaganate was overrun by the Tang general ], while the central part had emerged as the independent khaganate of ], led by a branch of the Ashina dynasty.{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} | |||

| {{Main|List of Khagans of the Göktürks}} | |||

| The ] of the Göktürks ruled the ], which then split into the ] and the ], and later the ], controlling much of Central Asia and the Mongolian Plateau between 552 and 745. The rulers were named "]" (Qaghan). | |||

| ==Religion== | |||

| ] was proclaimed Khagan of the Göktürks. | |||

| Their religion was polytheistic. The great god was the sky god, ], who dispensed the viaticum for the journey of life (qut) and fortune (ulug) and watched over the cosmic order and the political and social order. People prayed to him and sacrificed to him a white horse as the offering. The khagan, who came from him and derived his authority from him, was raised on a felt saddle to meet him. Tengri issued decrees, brought pressure to bear on human beings, and enforced capital punishment, often by striking the offender with lightning. The many secondary powers – sometimes named deities, sometimes spirits or simply said to be sacred, and almost always associated with Tengri – were the Earth, the Mountain, Water, the Springs, and the Rivers; the possessors of all objects, particularly of the land and the waters of the nation; trees, cosmic axes, and sources of life; fire, the symbol of the family and alterego of the shaman; the stars, particularly the sun and the moon, the Pleiades, and Venus, whose image changes over time; ], the great goddess who is none other than the goddess of the earth and placenta; the threshold and the doorjamb; personifications of Time, the Road, Desire, etc.; heroes and ancestors embodied in the banner, in tablets with inscriptions, and in idols; and spirits wandering or fixed in Penates or in all kinds of holy objects. These and other powers have an uneven force which increases as objects accumulate, as trees form a forest, stones form a cairn, arrows form a quiver, and drops of water form a lake.<ref>Asian Mythologies by Yves Bonnefoy, Page 315</ref> | |||

| ==Genetics== | |||

| In 659 the Tang Emperor of China could claim to rule the entire Silk Road as far as ''Po-sse'' ({{zh|c=波斯|p=bōsī}}, ]). The Göktürks now carried Chinese titles and fought by their side in their wars. The era spanning from 659-681 was characterized by numerous independent rulers - weak, divided, and engaged in constant petty wars. In the east, the Uyghurs defeated their one-time allies the Syr-Tardush, while in the west the ] emerged as successors to the Onoq. | |||

| {{See also|Karluks#Genetics|Kara-Khanid Khanate#Genetics|Kimek tribe#Genetics|Kipchaks#Genetics|Golden Horde#Genetics}} | |||

| ], surrounded by ]. ], Mingoi, Maya cave, 550–600 CE.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Yatsenko |first1=Sergey A. |title=Early Turks: Male Costume in the Chinese Art Second half of the 6th – first half of the 8th cc. (Images of 'Others') |journal=Transoxiana |date=2009 |volume=14 |page=Fig.16 |url=http://www.transoxiana.com.ar/14/yatsenko_turk_costume_chinese_art.html}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Grünwedel |first1=Albert |title=Altbuddhistische Kultstätten Chinesisch Turkistan |date=1912 |page=180 |url=https://archive.org/details/AltbuddhistischeKultstattenChinesischTurkistan1912/page/n92/mode/1up}}</ref>]] | |||

| A genetic study published in '']'' in May 2018 examined the remains of four elite Türk soldiers buried between ca. 300 AD and 700 AD.{{sfn|Damgaard et al.|2018|loc=Supplementary Table 2, Rows 60, 62, 127, 130}} 50% of the samples of ] belonged to the West Eurasian ], while the other 50% belonged to East Eurasian haplogroups ] and ].{{sfn|Damgaard et al.|2018|loc=Supplementary Table 9, Rows 44, 87, 88}} The extracted samples of ] belonged mainly to East Eurasian haplogroups ], ] and ], while one specimen carried the West Eurasian haplogroup ].{{sfn|Damgaard et al.|2018|loc=Supplementary Table 8, Rows 128, 130, 70, 73}} The authors suggested that central Asian nomadic populations may have been Turkicized by an East Asian minority elite, resulting in a small but detectable increase in East Asian ancestry. However, these authors also found that Türkic period individuals were extremely genetically diverse, with some individuals being of complete West Eurasian descent. To explain this diversity of ancestry, they propose that there were also incoming West Eurasians moving eastward on the Eurasian steppe during the Türkic period, resulting in admixture.<ref>{{cite journal | last1=Damgaard | first1=Peter de Barros | last2=Marchi | first2=Nina | title=137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes | journal=Nature | publisher=Springer Science and Business Media LLC | volume=557 | issue=7705 | year=2018 | issn=0028-0836 | doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2 | pages=369–374| pmid=29743675 | bibcode=2018Natur.557..369D | hdl=1887/3202709 | s2cid=256769352 | hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Damgaard|Marchi|2018|p=372|ps=: "These results suggest that Turk cultural customs were imposed by an East Asian minority elite onto central steppe nomad populations, resulting in a small detectable increase in East Asian ancestry. However, we also find that steppe nomad ancestry in this period was extremely heterogeneous with several individuals being genetically distributed at the extremes of the first principal component (Figure 2) separating Eastern and Western descent. Based on this notable heterogeneity, we interpret that during Medieval times, the steppe populations were exposed to gradual admixture from the East, while interacting with incoming west Eurasians. The strong variation is a direct window into ongoing admixture processes and to the multi-ethnic cultural organization of this period."}}</ref> | |||

| ==Eastern Turks under the Jimi system== | |||

| A 2020 study analyzed genetic data from 7 early medieval Türk skeletal remains from ] burial sites in Mongolia.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Jeong |first1=Choongwon |title=A Dynamic 6,000-Year Genetic History of Eurasia's Eastern Steppe |journal=Cell |date=12 November 2020 |volume=183 |issue=4 |pages=890–904.e29 |doi=10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.015 |pmid=33157037 |pmc=7664836 |language=en |issn=0092-8674|hdl=21.11116/0000-0007-77BF-D |hdl-access=free }}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Jeong|2020|ps=: "Türk (550-750 CE). Göktürkic tribes of the Altai Mountains established a political structure across Eurasia beginning in 552 CE, with an empire that ruled over Mongolia from 581-742 CE (Golden, 1992). A brief period of disunion occurred between 659-682 CE, during which the Chinese Tang dynasty laid claim over Mongolia...We analyzed individuals from 5 Türk sites in this study: Nomgonii Khundii (NOM), Shoroon Bumbagar (Türkic mausoleum; TUM), Zaan-Khoshuu (ZAA), Uliastai River Lower Terrace (ULI), and Umuumur uul (UGU)."}}</ref> The authors described the Türk samples as highly diverse, carrying on average 40% West Eurasian, and 60% East Eurasian ancestry. West Eurasian ancestry in the Türks combined ]-related and ] ancestry, while the East Eurasian ancestry was related to ]. The authors also observed that the ] ancestry in the Türks was largely inherited from male ancestors, which also corresponds with the marked increase of paternal haplogroups such as ] and ] during the Türkic period in Mongolia.<ref>{{harvnb|Jeong|2020|ps=: "We observe a clear signal of male-biased WSH admixture among the EIA Sagly/Uyuk and during the Türkic period (i.e., more positive Z scores; Figure 5B), which also corresponds to the decline in the Y chromosome lineage Q1a and the concomitant rise of the western Eurasian lineages such as R and J (Figure S2A)."}}</ref> Admixture between East and West Eurasian ancestors of the Türkic samples was dated to 500 AD, which is 8 generations prior.<ref>{{harvnb|Jeong|2020|ps=: "The admixture dates estimated for the ancient Türkic and Uyghur individuals in this study correspond to ca. 500 CE: 8 ± 2 generations before the Türkic individuals and 12 ± 2 generations before the Uyghur individuals (represented by ZAA001 and Olon Dov individuals)."}}</ref> Three of the Türkic-affiliated males carried the ] J2a and ], two carried haplogroup ], and one carried ]. The analyzed ] were identified as ], ], ], ], ] and ].<ref>{{harvnb|Jeong|2020|ps=: "Table S2, S2C_SexHaplogroups, Supplementary Materials GUID: E914F9CE-9ED4-4E0F-9172-5A54A08E9F6B}}</ref> | |||

| On May 19, 639<ref>]十三年 四月戊寅 {{Zh icon}}</ref> ] and his tribesmen assaulted ] at ] (九成宮, in present day ], ], ]). However, they didn't succeed and fled to the north, but were arrested by pursuers near the Wei River and killed. ] was exiled to Lingbiao.<ref name="Zizhi195">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> After the unsuccessful raid of Ashina Jiesheshuai, on August 13, 639<ref>]十三年 七月庚戌 {{Zh icon}}</ref> ] instated ] as the Yiminishuqilibi Khan and ordered the settled Turkic people to follow Ashina Simo north of the ] to settle between the ] and the ].<ref>Ouyang Xiu et al., ''New Book of Tang'', ]</ref> | |||

| ] (551–582), a royal Göktürk and immediate descendant of the Göktürk khagans, belonged genetically to the ] (ANA, <small>{{Colorsample|#FFD700|0.6}}</small> yellow area), supporting the Northeast Asian origin of the Ashina tribe and the Gökturks.<ref name="Yang 2023 3–43">{{harvnb|Yang|Meng|Zhang|2023|pp=3–4}}</ref>{{sfn|Jeong|2020|loc=Figure S4A}}]] | |||

| A 2023 study published in the ] analyzed the DNA of ] (551–582), a royal Göktürk and immediate descendant of the first Khagans, whose remains were recovered from a mausoleum in ], ].<ref name="Yang2023">{{cite journal |last1=Yang |first1=Xiao-Min |last2=Meng |first2=Hai-Liang |last3=Zhang |first3=Jian-Lin |title=Ancient genome of Empress Ashina reveals the Northeast Asian origin of Göktürk Khanate |journal=Journal of Systematics and Evolution |date=17 January 2023 |volume=61 |issue=6 |pages=1056–1064 |doi=10.1111/jse.12938 |s2cid=255690237 |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jse.12938 |language=en |issn=1674-4918}}</ref> The authors determined that Empress Ashina belonged to the North-East Asian ] haplogroup ]. Approximately 96-98% of her autosomal ancestry was of ] origin, while roughly 2-4% was of West Eurasian origin, indicating ancient admixture, and no Chinese ("Yellow River") admixture.<ref name="Yang 2023 3–43"/> The results are consistent with a ] of the royal Ashina family and the ].<ref name="Yang2023"/> However, the Ashina did not show close genetic affinity with central-steppe Türks and early medieval Türks, who exhibit a high (but variable) degree of West Eurasian ancestry, which indicates that there was genetic sub-structure within the Türkic empire. For example, the ancestry of early medieval Turks was derived from Ancient Northeast Asians for about 62% of their genome, while the remaining 38% was derived from West Eurasians (] and ]), with the admixture occurring around the year 500 CE.<ref>{{harvnb|Jeong|2020|p=897|ps=: See figure 4, B for admixture proportions in earlyMed_Turk. "...it is clear that these individuals have genetic profiles that differ from the preceding Xiongnu period, suggesting new sources of gene flow into Mongolia at this time that displace them along PC3 (Figure 2)...The admixture dates estimated for the ancient Türkic and Uyghur individuals in this study correspond to ca. 500 CE: 8 ± 2 generations before the Türkic individuals and 12 ± 2 generations before the Uyghur individuals (represented by ZAA001 and Olon Dov individuals)."}}</ref><ref>{{harvnb|Yang|Meng|Zhang|2023|p=4|ps=: "The early Medieval Türk (earlyMed_Turk) derived the major ancestry from ANA at a proportion of 62.2%, the remainder from BMAC (10.7%) and Western Steppe Afanasievo nomad (27.1%) (Figs. 1C, 1D; Table S2E)."}}</ref> | |||

| The Ashina was found to share genetic affinities to post-Iron Age Tungusic and Mongolic pastoralists, and was genetically closer to East Asians, while having heterogeneous relationships towards various Turkic-speaking groups in central Asia, suggesting genetic heterogeneity and multiple sources of origin for the population of the Turkic empire. This shows that the Ashina lineage had a dominating contribution on Mongolic and Tungusic speakers but limited contribution on Turkic-speaking populations. According to the authors, these findings "once again validates a cultural diffusion model over a demic diffusion model for the spread of Turkic languages" and refutes "the western Eurasian origin and multiple origin hypotheses" in favor of an East Asian origin for the royal Ashina family.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Meng |first=Hailiang |title=Ancient Genome of Empress Ashina reveals the Northeast Asian origin of Göktürk Khanate |url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/366965287 |journal=Journal of Systematics and Evolution |quote="Ashina individual clustered with ancient populations from Northeast Asia and eastern Mongolia Plateau, and especially with the Northeast Asian hunter‐gatherers."}}</ref> | |||

| In 679, ] and ], who were Turkic leaders of ] (]), declared ] as qaghan and revolted against the Tang dynasty.<ref name="Zizhi202">Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> In 680, ] defeated Ashina Nishufu and his army. Ashina Nishufu was killed by his men.<ref name="Zizhi202"/> Ashide Wenfu made ] a qaghan and again revolted against the Tang dynasty.<ref name="Zizhi202"/> Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian surrendered to Pei Xingjian. On December 5, 681<ref>]元年 十月乙酉 {{Zh icon}}</ref> 54 Göktürks including Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian were publicly executed in the Eastern Market of ].<ref name="Zizhi202"/> In 682, ] and ] revolted and occupied Heisha Castle (northwest of present day ], ]) with the remnants of Ashina Funian's men.<ref>Sima Guang, ''Zizhi Tongjian'', ] {{Zh icon}}</ref> | |||

| Two Türk remains (GD1-1 and GD2-4) excavated from present-day eastern Mongolia analysed in a 2024 paper, were found to display only little to no West Eurasian ancestry. One of the Türk remains (GD1-1) was derived entirely from an Ancient Northeast Asian source (represented by ] or Khovsgol_LBA and Xianbei_Mogushan_IA), while the other Türk remain (GD2-4) displayed an "admixed profile" deriving c. 48−50% ancestry from Ancient Northeast Asians, c. 47% ancestry from an ancestry maximised in ] (represented by Han_2000BP), and 3−5% ancestry from a West Eurasian source (represented by ]). The GD2-4 belonged to the paternal ]. The authors argue that these findings are "providing a new piece of information on this understudied period".<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lee |first1=Juhyeon |last2=Sato |first2=Takehiro |last3=Tajima |first3=Atsushi |last4=Amgalantugs |first4=Tsend |last5=Tsogtbaatar |first5=Batmunkh |last6=Nakagome |first6=Shigeki |last7=Miyake |first7=Toshihiko |last8=Shiraishi |first8=Noriyuki |last9=Jeong |first9=Choongwon |last10=Gakuhari |first10=Takashi |date=1 March 2024 |title=Medieval genomes from eastern Mongolia share a stable genetic profile over a millennium |url=https://www.pivotscipub.com/hpgg/4/1/0004 |journal=Human Population Genetics and Genomics |language=en |volume=4 |issue=1 |pages=1–11 |doi=10.47248/hpgg2404010004 |issn=2770-5005|doi-access=free }}</ref> | |||

| ==Second Turk Khaganate== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] (8th century AD). Discovered in the ].]] | |||

| Despite all the setbacks, Ashina Kutlug (Ilterish Qaghan) and his brother ] succeeded in reestablishing the Khanate. In 681{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} they revolted against the Tang Dynasty Chinese domination and, over the following decades, steadily gained control of the ]s beyond the ]. By 705, they had expanded as far south as ] and threatened the ] control of ]. The Göktürks clashed with the ] ] in a series of battles (712–713) but the Arabs emerged as victors. | |||

| ==Gallery== | |||

| Following the Ashina tradition,{{Citation needed|date=July 2010}} the power of the Second Khaganate<ref>Elena Vladimirovna Boĭkova, R. B. Rybakov, ''Kinship in the Altaic World: Proceedings of the 48th Permanent International Altaistic Conference, Moscow 10–15 July 2005'', Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, 2006, ISBN 978-3-447-05416-4, </ref><ref>Anatoly Michailovich Khazanov, ''Nomads and the Outside World'', Univ of Wisconsin Press, 1984, ISBN 978-0-299-14284-1, </ref><ref>András Róna-Tas, ''An introduction to Turkology'', Universitas Szegediensis de Attila József Nominata, 1991, </ref> was centered on Ötüken (the upper reaches of the ]). This polity was described by historians as "the joint enterprise of the Ashina clan and the ], with large numbers of Chinese bureaucrats being involved as well".<ref>Wink 66.</ref> The son of Ilterish, ], was also a strong leader whose deeds were recorded in the ]. After his death in 734 the Second Turkic Khaganate declined. The Göktürks ultimately fell victim to a series of internal crises and renewed Chinese campaigns. | |||

| {{Gallery | |||

| |width=160 | |||

| |height=100 | |||

| |File:Battle scene of a Turkic horseman with typical long hair (Gokturk period, Altai).png|Battle scene depicting Turkic horsemen, typical braided hair style, Chaganka, ] region, 5th-6th century AD | |||

| |File:Shoroon Bumbagar tomb mural, 7th century CE, Mongolia.jpg|] mural, ], 7th century CE, Mongolia<ref name="Altınkılıç"/><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Narantsatsral |first1=D |title=THE SILK ROAD CULTURE AND ANCIENT TURKISH WALL PAINTED TOMB |journal=The Journal of International Civilization Studies |url=http://www.inciss.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Narantsatsral-2.pdf |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201026144159/http://www.inciss.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Narantsatsral-2.pdf |archive-date=26 October 2020 |url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| |File:Gokturk cav.jpg|] cavalry mural, ], 7th century CE.<ref name="Altınkılıç" /> | |||

| |File:An Jia with a Turkic Chieftain in Yurt. Xi’an, 579 CE. Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an.jpg|The Sogdian merchant An Jia with a Turkic Chieftain in his ].<ref name="REF1"/><ref name="SYET"/> | |||

| |File:An Jia brokering an alliance with Turks. Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an.jpg|An Jia (right) brokering an alliance with Turks (left).<ref name="REF1">{{cite book |last1=Baumer |first1=Christoph |title=History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set |date=18 April 2018 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-1-83860-868-2 |page=228 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DhiWDwAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA228 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="SYET">{{cite journal |last1=Yatsenko |first1=Sergey A. |title=Early Turks: Male Costume in the Chinese Art |journal=Transoxiana |date=August 2009 |volume=14 |url=http://www.transoxiana.com.ar/14/yatsenko_turk_costume_chinese_art.html}}</ref> | |||

| |File:An Jia welcoming a Turk. Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology, Xi’an.jpg|Panel from the ], a Sogdian trader (right), who is shown welcoming a Turkic leader (left, with long hair combed in the back). 579 CE, ], ].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Baumer |first1=Christoph |title=History of Central Asia, The: 4-volume set |date=18 April 2018 |publisher=Bloomsbury Publishing |isbn=978-1-83860-868-2 |page=228 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=DhiWDwAAQBAJ&pg=RA1-PA228 |language=en}}</ref><ref name="SYET">{{cite journal |last1=Yatsenko |first1=Sergey A. |title=Early Turks: Male Costume in the Chinese Art |journal=Transoxiana |date=August 2009 |volume=14 |url=http://www.transoxiana.com.ar/14/yatsenko_turk_costume_chinese_art.html}}</ref> | |||

| }} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| When ] of the Uyghurs allied himself with the ] and ]s, the power of the Göktürks was very much on the wane. In 744 Kutluk seized Ötükän and beheaded the last Göktürk khagan ], whose head was sent to the Tang Dynasty Chinese court.<ref>Grousset 114.</ref> In a space of few years, the Uyghurs gained mastery of Inner Asia and established the ]. | |||

| {{History of the Turkic peoples pre-14th century}} | |||

| {{commons category|Gökturks}} | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Customs and culture== | |||

| '''Origin of Achinas or Ashinas''' | |||

| In 439 AD in Central Asia a distinctive clan called “Achina” or “Ashina” lived in the territory now located in north-west China, Xinjiang province or Eastern Turkistan. They spoke either a Turkic or Mongolic language and they were the remnants of the aristocracy of the steppes’ former Xiongnu Empire which had been destroyed by the China Han dynasty in circa 100 AD. Their name, according to the prominent historian “Lev Gumilev” is derived from the Mongolian word for ''wolf'' “chono”, “china” or “shina” with a Chinese prefix of “A” which means the respectful, elder, important. In combination it means ''Noble Wolf'' or simply ''“The” Wolf''. | |||

| ;Political system | |||

| ] points out that there is the possibility that the leaders of the ], the ], were themselves originally an Indo-European-speaking (possibly ]) clan who later adopted Turkic, but inherited their original Indo-European titles.<ref>Peter B. Golden, ''An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples'', O. Harrassowitz, 1992, p. 121-122</ref> German Turkologist W.-E. Scharlipp writes that many central terms are ] in origin.<ref>„(...) Über die Ethnogenese dieses Stammes ist viel gerätselt worden. Auffallend ist, dass viele zentrale Begriffe iranischen Ursprungs sind. Dies betrifft fast alle Titel (...). Einige Gelehrte wollen auch die Eigenbezeichnung türk auf einen iranischen Ursprung zurückführen und ihn mit dem Wort „Turan“, der persischen Bezeichnung für das Land jeneseits des Oxus, in Verbindung bringen.“ Wolfgang-Ekkehard Scharlipp in ''Die frühen Türken in Zentralasien'', p. 18</ref> | |||

| The Göktürks' temporary '']'' from the Ashina clan were ''subordinate'' to a ] authority that was left in the hands of a council of tribal chiefs{{Citation needed|date=October 2008}}. | |||

| ;Language and character | |||

| The Göktürks were the first Turkic people known to write ] in the ]. Life stories of ] and ], as well as the chancellor ] were recorded in the ]. | |||

| ;Religion | |||

| The Khaganate received missionaries from the ]s religion, which were incorporated into ]. Later most of the Turks settled in Central Asia, Middle east and Eastern Europe adopted the ]ic faith. | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | *] | ||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| *] | |||

| ==In popular culture== | |||

| *] | |||

| *], fictional character based on Göktürk prince ] | |||

| *] | |||

| *], ], ] satellites named after Göktürks | |||

| *] exoplanet named after Gökturks | |||

| <div style="clear:both;" class=></div> | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist| |

{{Reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==Sources== | |||

| ;Bibliography | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Christian |first=David |title=A history of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia, Vol. 1: Inner Eurasia from prehistory to the Mongol Empire |publisher=Blackwell |year=1998}} | |||

| *Findley, Carter Vaughin. ''The Turks in World History''. ], 2005. ISBN 0-19-517726-6. | |||

| * {{cite book|last=Findley|first=Carter Vaughn|title=The Turks in World History|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7eyoacDdcIMC|year=2004|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-19-988425-4}} | |||

| *], 3rd ed. Article "Turkic Khaganate" (). | |||

| * {{cite journal |last1=Damgaard |first1=P. B. |last2=Marchi |first2=N. |display-authors=1 |date=9 May 2018 |title=137 ancient human genomes from across the Eurasian steppes |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-018-0094-2 |access-date=11 April 2020 |journal=] |publisher=] |volume=557 |issue=7705 |pages=369–373 |bibcode= 2018Natur.557..369D|doi=10.1038/s41586-018-0094-2 |pmid=29743675 |hdl=1887/3202709 |s2cid=13670282 |ref={{harvid|Damgaard et al.|2018}}|hdl-access=free }} | |||

| *]. ''The Empire of the Steppes''. ], 1970. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9. | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Golden | first=Peter |author-link=Peter Benjamin Golden | title=An Introduction to the History of the Turkic Peoples: Ethnogenesis and State-Formation in Medieval and Early Modern Eurasia and the Middle East | publisher=Otto Harrassowitz | location=Wiesbaden | year=1992 | isbn=978-3-447-03274-2 }} | |||

| *] (2007) {{Ru icon}} ''The Gokturks'' (Древние тюрки ;Drevnie ti︠u︡rki). Moscow: AST, 2007. ISBN 5-17-024793-1. | |||

| * {{cite journal|last=Golden|first= Peter B.|title=The Ethnogonic Tales of the Türks|journal=The Medieval History Journal |doi=10.1177/0971945818775373|pages= 291–327|date=August 2018|volume= 21|issue= 2|s2cid= 166026934}} | |||

| *Yu. Zuev (I︠U︡. A. Zuev) (2002) {{Ru icon}}, ''"Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology"'' (), ], Daik-Press, p. 233, {{Listed Invalid ISBN|9985-4-4152-9}} | |||

| * {{cite book|last1=Golden|first1=Peter Benjamin|author-link1=Peter Benjamin Golden|title=Studies on the peoples and cultures of the Eurasian steppes|date=2011|publisher=Ed. Acad. Române|location=București|isbn=978-973-1871-96-7|chapter=Ethnogenesis in the tribal zone: The Shaping of the Turks|chapter-url=https://www.academia.edu/9609971}} | |||

| *Wink, André. ''Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World''. ], 2002. ISBN 0-391-04173-8. | |||

| *], 3rd ed. Article "Turkic Khaganate" ( {{Webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20050516102002/http://www.cultinfo.ru/fulltext/1/001/008/113/276.htm |date=16 May 2005 }}). | |||

| *Zhu, Xueyuan (朱学渊) (2004) {{zh icon}} ''The Origins of Northern China's Ethnicity'' (中国北方诸族的源流). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju (中华书局) ISBN 7-101-03336-9 | |||

| *]. ''The Empire of the Steppes''. ], 1970. {{ISBN|0-8135-1304-9}}. | |||

| *Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正) (1992) {{zh icon}} ''A History of Turks'' (突厥史). Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press (中国社会科学出版社) ISBN 7-5004-0432-8 | |||

| *] (2007) {{in lang|ru}} ''The Göktürks'' (Древние тюрки ;Drevnie ti︠u︡rki). Moscow: AST, 2007. {{ISBN|5-17-024793-1}}. | |||

| *{{cite book|first=Jonathan Karem|last=Skaff|editor=Nicola Di Cosmo|title=Military Culture in Imperial China|year=2009|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-674-03109-8|ref=none}} | |||

| *Yu. Zuev (I︠U︡. A. Zuev) (2002) {{in lang|ru}}, ''"Early Türks: Essays on history and ideology"'' (), ], Daik-Press, p. 233, {{Listed Invalid ISBN|9985-4-4152-9}} | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Holcombe |first1=Charles |title=The Genesis of East Asia, 221 B.C.-A.D. 907 |date=2001 |publisher=University of Hawaii Press |isbn=978-0-8248-2465-5 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=XT5pvPZ4vroC |language=en}} | |||

| *{{cite book|first=Howard J.|last=Wechsler|chapter=T'ai-Tsung (Reign 626–49): The Consolidator|editor=Denis Twitchett|editor2=John Fairbank|title=The Cambridge History of China, Volume 3: Sui and T'ang China Part I|year=1979|publisher=Cambridge University Press|isbn=978-0-521-21446-9|ref=none}} | |||

| *Wink, André. ''Al-Hind: The Making of the Indo-Islamic World''. ], 2002. {{ISBN|0-391-04173-8}}. | |||

| *Zhu, Xueyuan (朱学渊) (2004) {{in lang|zh}} ''The Origins of the Ethnic Groups of Northern China'' (中国北方诸族的源流). Beijing: Zhonghua Shuju (中华书局) {{ISBN|7-101-03336-9}} | |||

| *Xue, Zongzheng (薛宗正) (1992) {{in lang|zh}} ''A History of the Turks'' (突厥史). Beijing: Chinese Social Sciences Press (中国社会科学出版社) {{ISBN|7-5004-0432-8}} | |||

| *{{cite book|title= Romans, Barbarians, and the Transformation of the Roman World: Cultural Interaction and the Creation of Identity in Late Antiquity|first=Ekaterina|publisher=Ashgate|year=2011|isbn=978-0-7546-6814-5|pages=175–181|chapter= The "Runaway" Avars and Late Antique Diplomacy|editor=Ralph W. Mathisen, Danuta Shanzer|last= Nechaeva|ref=none}} | |||

| *{{cite book|last=Sinor|first=Denis|author-link=Denis Sinor|title=The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ST6TRNuWmHsC&pg=PA295|year=1990|publisher=]|isbn=978-0-521-24304-9}} | |||

| * {{citation|last=West|first=Barbara A.|year=2008|title=Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania}} | |||

| <!--==External links==---> | <!--==External links==---> | ||

| Line 164: | Line 148: | ||

| {{Turkic topics}} | {{Turkic topics}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Gokturks}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Gokturks}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 05:27, 7 December 2024

Turkic people in Inner Asia For empires established by the Gökturks, see First Turkic Khaganate, Western Turkic Khaganate, Eastern Turkic Khaganate, and Second Turkic Khaganate. For other uses, see Göktürk (disambiguation).Ethnic group

| 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣 Türük Bodun | |

|---|---|

Gökturk petroglyphs from modern Mongolia (6th to 8th century). Gökturk petroglyphs from modern Mongolia (6th to 8th century). | |

| Total population | |

| Ancestral to some Turkic populations | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Central and Eastern Asia | |

| Languages | |

| Orkhon Turkic | |

| Religion | |

| Tengrism, Buddhism | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Türgesh, Toquz Oghuz, Yenisei Kyrgyz, Xueyantuo, Shatuo |

The Göktürks, Türks, Celestial Turks or Blue Turks (Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜:𐰉𐰆𐰑𐰣, romanized: Türük Bodun; Chinese: 突厥; pinyin: Tūjué; Wade–Giles: T'u-chüeh) were a Turkic people in medieval Inner Asia. The Göktürks, under the leadership of Bumin Qaghan (d. 552) and his sons, succeeded the Rouran Khaganate as the main power in the region and established the First Turkic Khaganate, one of several nomadic dynasties that would shape the future geolocation, culture, and dominant beliefs of Turkic peoples.

Etymology

Origin

The common name "Göktürk" emerged from the misreading of the word "Kök" meaning Ashina, the endonym of the ruling clan of the historical ethnic group which was attested as 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜, Türük 𐰚𐰇𐰜:𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜, Kök Türük, or Old Turkic: 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰚, romanized: Türk. It is generally accepted that the name Türk is ultimately derived from the Old-Turkic migration-term 𐱅𐰇𐰼𐰜 Türük/Törük, which means 'created, born'.

They were known in Middle Chinese historical sources as the Tūjué (Chinese: 突 厥; reconstructed in Middle Chinese as romanized: *dwət-kuɑt > tɦut-kyat).

The ethnonym was also recorded in various other Middle Asian languages, such as Sogdian *Türkit ~ Türküt, tr'wkt, trwkt, turkt > trwkc, trukč; Khotanese Saka Ttūrka/Ttrūka, Rouran to̤ro̤x/türǖg, Korean 돌궐/Dolgwol, and Old Tibetan Drugu.

Definition

According to Chinese sources, Tūjué meant "combat helmet" (Chinese: 兜 鍪; pinyin: Dōumóu; Wade–Giles: Tou-mou), reportedly because the shape of the Altai Mountains, where they lived, was similar to a combat helmet. Róna-Tas (1991) pointed to a Khotanese-Saka word, tturakä "lid", semantically stretchable to "helmet", as a possible source for this folk etymology, yet Golden thinks this connection requires more data.

Göktürk is sometimes interpreted as either "Celestial Turk" or "Blue Turk" (i.e. because sky blue is associated with celestial realms). This is consistent with "the cult of heavenly ordained rule" which was a recurrent element of Altaic political culture and as such may have been imbibed by the Göktürks from their predecessors in Mongolia. "Blue" is traditionally associated with the East as it used in the cardinal system of central Asia, thus meaning "Turks of the East". The name of the ruling Ashina clan may derive from the Khotanese Saka term for "deep blue", āššɪna.

According to the American Heritage Dictionary, the word Türk meant "strong" in Old Turkic; though Gerhard Doerfer supports this theory, Gerard Clauson points out that "the word Türk is never used in the generalized sense of 'strong'" and that the noun Türk originally meant "'the culminating point of maturity' (of a fruit, human being, etc.), but more often used as an meaning (of a fruit) 'just fully ripe'; (of a human being) 'in the prime of life, young, and vigorous'". Hakan Aydemir (2022) also contends that Türk originally did not mean "strong, powerful" but "gathered; united, allied, confederated" and was derived from Pre-Proto-Turkic verb *türü "heap up, collect, gather, assemble".

The name as used by the Göktürks only applied to themselves, the Göktürk khanates, and their subjects. The Göktürks did not consider other Turkic speaking groups such as the Uyghurs, Tiele, and Kyrgyz to be Türks. In the Orkhon inscriptions, the Toquz Oghuz and the Yenisei Kyrgyz are not referred to as Türks. Similarly, the Uyghurs called themselves Uyghurs and used Türk exclusively for the Göktürks, whom they portrayed as enemy aliens in their royal inscriptions. The Khazars may have kept the Göktürk tradition alive by claiming descent from the Ashina. When tribal leaders built their khanates, ruling over assorted tribes and tribal unions, the collected people identified themselves politically with the leadership. Turk became the designation for all subjects of the Turk empires. Nonetheless, subordinate tribes and tribal unions retained their original names, identities, and social structures. Memory of the Göktürks and the Ashina had faded by the turn of the millennium. The Karakhanids, Qocho Uyghurs, and Seljuks did not claim descent from the Göktürks.

History

Origins

See also: Timeline of the Göktürks

The Göktürk rulers originated from the Ashina clan, who were first attested to in 439. The Book of Sui reports that in that year, on 18 October, the Tuoba ruler Emperor Taiwu of Northern Wei overthrew Juqu Mujian of the Northern Liang in eastern Gansu, whence 500 Ashina families fled northwest to the Rouran Khaganate in the vicinity of Gaochang.

According to the Book of Zhou and History of the Northern Dynasties, the Ashina clan was a component of the Xiongnu confederation, specifically, the Northern Xiongnu tribes or southern Xiongnu "who settled along the northern Chinese frontier", according to Edwin G. Pulleyblank. However, this view is contested. Göktürks were also posited as having originated from an obscure Suo state (索國) (MC: *sâk) which was situated north of the Xiongnu and had been founded by the Sakas or Xianbei. According to the Book of Sui and the Tongdian, they were "mixed Hu (barbarians)" (雜胡) from Pingliang (平涼), now in Gansu, Northwest China. Pointing to the Ashina's association with the Northern tribes of the Xiongnu, some researchers (e.g. Duan, Lung, etc.) proposed that Göktürks belonged in particular to the Tiele confederation, likewise Xiongnu-associated, by ancestral lineage. However, Lee and Kuang (2017) state that Chinese sources do not describe the Ashina-led Göktürks s descending from the Dingling or belonging to the Tiele confederation.

Chinese sources linked the Hu on their northern borders to the Xiongnu just as Graeco-Roman historiographers called the Pannonian Avars, Huns and Hungarians "Scythians". Such archaizing was a common literary topos, implying similar geographic origins and nomadic lifestyle but not direct filiation.

As part of the heterogeneous Rouran Khaganate, the Turks lived for generations north of the Altai Mountains, where they 'engaged in metal working for the Rouran'. According to Denis Sinor, the rise to power of the Ashina clan represented an 'internal revolution' in the Rouran Khaganate rather than an external conquest.

According to Charles Holcombe, the early Turk population was rather heterogeneous and many of the names of Turk rulers, including the two founding members, are not even Turkic. This is supported by evidence from the Orkhon inscriptions, which include several non-Turkic lexemes, possibly representing Uralic or Yeniseian words. Peter Benjamin Golden points out that the khaghans of the Turkic Khaganate, the Ashina, who were of an undetermined ethnic origin, adopted Iranian and Tokharian (or non-Altaic) titles. German Turkologist W.-E. Scharlipp points out that many common terms in Turkic are Iranian in origin. Whatever language the Ashina may have spoken originally, they and those they ruled would all speak Turkic, in a variety of dialects, and create, in a broadly defined sense, a common culture.

Expansion

Main article: First Turkic Khaganate

KyrgyzsCHAM-

KyrgyzsCHAM-PA576CHENLAFIRST TURKIC KHAGANATESASANIAN

EMPIREALCHON

HUNSCHALU-

KYASLATER

GUPTASNORTH.

ZHOUNORTH.

QIZHANGZHUNGCHENBYZANTINE

EMPIREAVAR

KHAGANATETUYUHUNKhitansPaleo-SiberiansTungusGOGU-

RYEOTOCHA-

RIANSclass=notpageimage| The First Turkic Khaganate and contemporary polities, circa 576

The Göktürks reached their peak in the late 6th century and began to invade the Sui dynasty of China. However, the war ended due to the division of Turkic nobles and their civil war for the throne of Khagan. With the support of Emperor Wen of Sui, Yami Qaghan won the competition. However, the Göktürk empire was divided to Eastern and Western empires. Weakened by the civil war, Yami Qaghan declared allegiance to the Sui dynasty. When Sui began to decline, Shibi Khagan began to assault its territory and even surrounded Emperor Yang of Sui in Siege of Yanmen (615 AD) with 100,000 cavalry troops. After the collapse of the Sui dynasty, the Göktürks intervened in the ensuing Chinese civil wars, providing support to the northeastern rebel Liu Heita against the rising Tang in 622 and 623. Liu enjoyed a long string of success but was finally routed by Li Shimin and other Tang generals and executed. The Tang dynasty was then established.

Conquest by the Tang

Main article: Tang dynasty in Inner AsiaAlthough the Göktürk Khaganate once provided support to the Tang dynasty in the early period of the civil war during the collapse of the Sui dynasty, the conflicts between the Göktürks and Tang finally broke out when Tang was gradually reunifying China proper. The Göktürks began to attack and raid the northern border of the Tang Empire and once marched their main force of 100,000 soldiers to Chang'an, the capital of Tang. The emperor Taizong of the Tang, in spite of the limited resources at his disposal, managed to turn them back. Later, Taizong sent his troops to Mongolia and defeated the main force of Göktürk army in Battle of Yinshan four years later and captured Illig Qaghan in 630 AD. With the submission of the Turkic tribes, the Tang conquered the Mongolian Plateau. From then on, the Eastern Turks were subjugated to China.

After a vigorous court debate, Emperor Taizong decided to pardon the Göktürk nobles and offered them positions as imperial guards. However, the proposition was ended by a plan for the assassination of the emperor. On 19 May 639 Ashina Jiesheshuai and his tribesmen directly assaulted Emperor Taizong of Tang at Jiucheng Palace (九成宮, in present-day Linyou County, Baoji, Shaanxi). However, they did not succeed and fled to the north, but were caught by pursuers near the Wei River and were killed. Ashina Hexiangu was exiled to Lingbiao. After the unsuccessful raid of Ashina Jiesheshuai, on 13 August 639 Taizong installed Qilibi Khan and ordered the settled Turkic people to follow him north of the Yellow River to settle between the Great Wall of China and the Gobi Desert. However, many Göktürk generals still remained loyal in service to the Tang Empire.

Revival

Main article: Second Turkic KhaganateIn 679, Ashide Wenfu and Ashide Fengzhi, who were Turkic leaders of the Chanyu Protectorate (單于大都護府), declared Ashina Nishufu as qaghan and revolted against the Tang dynasty. In 680, Pei Xingjian defeated Ashina Nishufu and his army. Ashina Nishufu was killed by his men. Ashide Wenfu made Ashina Funian a qaghan and again revolted against the Tang dynasty. Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian surrendered to Pei Xingjian. On 5 December 681, 54 Göktürks, including Ashide Wenfu and Ashina Funian, were publicly executed in the Eastern Market of Chang'an. In 682, Ilterish Qaghan and Tonyukuk revolted and occupied Heisha Castle (northwest of present-day Hohhot, Inner Mongolia) with the remnants of Ashina Funian's men. The restored Göktürk Khaganate intervened in the war between Tang and Khitan tribes. However, after the death of Bilge Qaghan, the Göktürks could no longer subjugate other Turk tribes in the grasslands. In 744, allied with the Tang dynasty, the Uyghur Khaganate defeated the last Göktürk Khaganate and controlled the Mongolian Plateau.

Rulers

Main article: List of Khagans of the GöktürksThe Ashina tribe of the Göktürks ruled the First Turkic Khaganate, which then split into the Eastern Turkic Khaganate and the Western Turkic Khaganate, and later the Second Turkic Khaganate, controlling much of Central Asia and the Mongolian Plateau between 552 and 745. The rulers were named "Khagan" (Qaghan).

Religion

Their religion was polytheistic. The great god was the sky god, Tengri, who dispensed the viaticum for the journey of life (qut) and fortune (ulug) and watched over the cosmic order and the political and social order. People prayed to him and sacrificed to him a white horse as the offering. The khagan, who came from him and derived his authority from him, was raised on a felt saddle to meet him. Tengri issued decrees, brought pressure to bear on human beings, and enforced capital punishment, often by striking the offender with lightning. The many secondary powers – sometimes named deities, sometimes spirits or simply said to be sacred, and almost always associated with Tengri – were the Earth, the Mountain, Water, the Springs, and the Rivers; the possessors of all objects, particularly of the land and the waters of the nation; trees, cosmic axes, and sources of life; fire, the symbol of the family and alterego of the shaman; the stars, particularly the sun and the moon, the Pleiades, and Venus, whose image changes over time; Umay, the great goddess who is none other than the goddess of the earth and placenta; the threshold and the doorjamb; personifications of Time, the Road, Desire, etc.; heroes and ancestors embodied in the banner, in tablets with inscriptions, and in idols; and spirits wandering or fixed in Penates or in all kinds of holy objects. These and other powers have an uneven force which increases as objects accumulate, as trees form a forest, stones form a cairn, arrows form a quiver, and drops of water form a lake.

Genetics

See also: Karluks § Genetics, Kara-Khanid Khanate § Genetics, Kimek tribe § Genetics, Kipchaks § Genetics, and Golden Horde § Genetics