| Revision as of 19:34, 3 October 2012 editSun Creator (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers130,141 editsm Typo and general fixes, typos fixed: a enveloping → an enveloping using AWB (8414)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:04, 7 January 2025 edit undoWahreit (talk | contribs)174 edits provided a new section for the Panay attack, and some info from bob wakabayashis bookTag: Visual edit | ||

| (616 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1937 battle of the Second Sino-Japanese War}} | |||

| {{About|the 1937 battle|other battles|Battle of Nanjing (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Good article}} {{Use mdy dates|date=May 2023}} | |||

| {{Infobox military conflict | {{Infobox military conflict | ||

| | conflict = Battle of |

| conflict = Battle of Nanjing | ||

| | partof = the ] | | partof = the ] | ||

| | image = |

| image = Attacking the Gate of China02.jpg | ||

| | image_size = 300px | |||

| | caption = Japanese general ] rides into Nanking,<br>13 December 1937 | |||

| | caption = Japanese tanks attacking Nanjing's Zhonghua Gate under artillery fire | |||

| | date = 9 December 1937 – 31 January 1938 | |||

| | date = {{Date range and age in years, months, weeks and days|1937|11|11|1937|12|13}} | |||

| | place = ] and surrounding areas | |||

| | place = ] and surrounding areas, ] | |||

| | result = Japanese Victory, Fall of ], ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{Wikidatacoord|Q701180|type:event_region:CN-32|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | combatant1 = {{flagicon|ROC}} ]<br /> ] | |||

| | result = Japanese victory | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flagicon|Japan|alt}} ]<br /> ] | |||

| * Fall of Nanjing | |||

| | commander1 = {{flagicon|ROC}} ] | |||

| * Beginning of the ] | |||

| | commander2 = {{flagicon|Japan|alt}} ]<br /> {{flagicon|Japan|alt}}] | |||

| | combatants_header = | |||

| | strength1 = 70,000–80,000 men<ref>Askew, ''Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces'', p.173.</ref>(49,000 combat-ready)<ref name="Article"/> | |||

| | combatant1 = {{flagcountry|Republic of China (1912–1949)|23px}}<br/>'''Supported by:'''<br/>{{flagcountry|Soviet Union|1936}}<ref name="doomed">{{Cite book |last=Hamsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |publisher=] |year=2015 }}</ref> | |||

| | strength2 = 8 ], 240,000 men | |||

| | combatant2 = {{flagcountry|Empire of Japan|23px}} | |||

| | casualties1 = 10,000 killed<br/>17,000 captured<ref name="Article">Article about the Defense of Nanjing http://12424765.blog.hexun.com/41507553_d.html</ref> | |||

| | commander1 = {{flagicon|Republic of China (1912–1949)|army}} ] | |||

| | casualties2 = 6,000 soldiers killed<ref>Askew, ''Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces'', p.158.</ref><br/>Thousands more wounded<ref name="Article"/> | |||

| | commander2 = {{flagicon|Empire of Japan|army}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Empire of Japan|army}} ]<br>{{flagicon|Empire of Japan|army}} ] | |||

| | casualties3 = 300,000 civilians killed | |||

| | units1 = Nanjing Garrison Force<br/>]<ref name="doomed" /> | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Second Sino-Japanese War}} | |||

| | units2 = ] | |||

| | strength1 = '''Campaign Total:''' 100,000~<br><hr>'''Battle of Nanjing:'''<br>73,790 to 81,500<ref>{{cite journal |last=Askew |first=David |title=Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces |journal=Sino-Japanese Studies |date=April 15, 2003 |page=173 }}</ref> | |||

| | strength2 = '''Campaign Total:''' 200,000<ref>Kasahara "Nanking Incident" 1997, p. 115</ref><br><hr>'''Battle of Nanjing:'''<br>70,000<ref>{{cite book |last=Frank |first=Richard |date=2020 |title=Tower of Skulls: A History of the Asia-Pacific War |publisher=W. W. Norton & Company |page=47 }}</ref> | |||

| | casualties1 = '''Campaign Total:'''<br>33,000–70,000 dead<br>Tens of thousands wounded (many later died of wounds or executed)<br><hr>'''Battle for Nanjing:'''<br>6,000–20,000 killed and wounded<br/>30,000–40,000 POWs executed after capture<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Zhaiwei Sun |year=1997 |script-title=zh:南京大屠杀遇难同胞中究竟有多少军人 |url=http://jds.cass.cn/UploadFiles/zyqk/2010/12/201012101114478943.pdf |language=zh |issue=4 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150709222256/http://jds.cass.cn/UploadFiles/zyqk/2010/12/201012101114478943.pdf |archive-date=July 9, 2015 |access-date=April 14, 2017 |script-journal=zh:抗日战争研究 }}</ref> | |||

| | casualties2 = '''Campaign Total:'''<br>27,500 killed and wounded<ref>{{cite book |last=Lai |first=Benjamin |date=2017 |title=Shanghai and Nanjing 1937: Massacre on the Yangtze |publisher=Osprey Publishing |page=89 }}</ref><br><br><br><hr>'''Battle for Nanjing:'''<br>1,953 killed<br>4,994 wounded<ref name="Masahiro Yamamoto 20002">Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 118. Yamamoto cites Masao Terada, planning chief of Japan's 10th Army.</ref> | |||

| | casualties3 = 100,000–200,000 civilians killed in subsequent ] | |||

| | campaignbox = {{Campaignbox Second Sino-Japanese War}} | |||

| {{Japanese colonial campaigns}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| {{Infobox Chinese | |||

| | t = 南京保衛戰 | |||

| | s = 南京保卫战 | |||

| | p = Nánjīng Bǎowèi Zhàn | |||

| | w = Nan<sup>2</sup>-ching<sup>1</sup> Pao<sup>3</sup>-wei<sup>4</sup> Chan<sup>4</sup> | |||

| | l = Battle to Defend Nanjing | |||

| | kanji = 南京戦 | |||

| | kana = なんきんせん | |||

| | romaji = Nankin-sen | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Battle of Nanking''' (or '''Nanjing''') was fought in early December 1937 during the ] between the Chinese ] and the ] for control of ] ({{lang-zh|c=南京|p=Nánjīng}}), the capital of the ]. | |||

| Following the outbreak of war between ] and China in July 1937, the Japanese and Chinese forces engaged in the vicious three-month ], where both sides suffered heavy casualties. The Japanese eventually won the battle, forcing the Chinese army into a withdrawal. Capitalizing on their victory, the Japanese officially authorized a campaign to capture Nanjing. The task of occupying Nanjing was given to General ], the commander of Japan's Central China Area Army, who believed that the capture of Nanjing would force China to surrender and thus end the war. Chinese leader ] ultimately decided to defend the city and appointed ] to command the Nanjing Garrison Force, a hastily assembled army of local conscripts and the remnants of the Chinese units who had fought in ]. | |||

| The '''Battle of Nanking''' ({{zh|t=南京保衛戰|s=南京保卫战|p=Nánjīng Bǎowèi Zhàn|w=Nan-ching Pao-wei Chan}}) began after the fall of ] on October 9, 1937, and ended with the fall of the capital city of ] on December 13, 1937 to ]ese troops, a few days after the ] Government had evacuated the city and relocated to ]. The ] followed the fall of the city. | |||

| ] | |||

| In a five-week campaign between November 11 and December 9, the Japanese army marched from Shanghai to Nanjing at a rapid pace, pursuing the retreating Chinese army and overcoming all Chinese resistance in its way. The campaign was marked by tremendous brutality and destruction, with increasing levels of atrocities committed by Japanese forces against the local population, while Chinese forces implemented scorched earth tactics to slow the Japanese advances. | |||

| ==Strategic context== | |||

| {{Refimprove|date=November 2010}} | |||

| Following the ] in 1931, Japan began its invasion of Manchuria, China. Because the Communists and the Kuomintang (KMT) were engaged in the Chinese Civil War they were distracted from mounting a concerted defence against the Japanese who swiftly captured major Chinese cities in the northeast. In 1937, however, the Chinese communists and nationalists agreed to form a united front. The KMT then formally started an all-out defence against the Japanese threat. It is likely that China fielded the largest army in the world at the time in terms of troop numbers. However, the Chinese army was poorly trained and equipped: some regiments were armed primarily with swords and hand grenades and few had anti-tank weaponry. | |||

| Nevertheless, by December 9 the Japanese had reached the last line of defense, the Fukuo Line, behind which lay ]. On December 10 Matsui ordered an all-out attack on Nanjing, and after two days of intense fighting Chiang decided to abandon the city. Before fleeing, Tang ordered his men to launch a concerted breakout of the Japanese siege, but by this time Nanjing was largely surrounded and its defenses were at the breaking point. Most of Tang's troops collapsed in a disorganized rout. While some units were able to escape, many more were caught in the death trap the city had become. By December 13, Nanjing had fallen to the Japanese. | |||

| ===Defensive lines=== | |||

| In 1933, three military zones, ], Nanking-], and Nanking-], had been established to coordinate defenses in the Yangtze Delta. In 1934, with ], the construction of the so-called "Chinese ]" began, with a series of fortifications to facilitate ]. Two such lines, the Wufu Line (吳福線) between ] and Fushan, and the Xicheng Line (錫澄線) between ] and ], were built to protect the road to ], in case Shanghai should fall into enemy hands. In spring 1937, just barely months before the beginning of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the two defensive lines were finally completed. However, the necessary training of personnel to man these positions and coordinate the defence had not yet been completed when the war broke out. | |||

| Following the capture of the city, Japanese forces massacred Chinese prisoners of war, murdered civilians, and committed acts of looting, torture, and rape in the ]. Though Japan's victory excited and emboldened them, the subsequent massacre tarnished their reputation in the eyes of the world. Contrary to Matsui's expectations, China did not surrender and the Second Sino-Japanese War continued for another eight years, leading to an eventual Chinese victory. | |||

| ===Battle of Shanghai=== | |||

| {{main|Battle of Shanghai}} | |||

| In a major strategic gamble, ] decided to divert Japanese attacks in northern China by attacking Shanghai, which the Japanese had occupied earlier in 1937. Initially, Chinese forces surrounding Shanghai included the bulk of Chiang's best-trained forces. The Chinese armies surrounding Shanghai outnumbered the Japanese forces stationed there by more than 10 to 1. | |||

| ==Background== | |||

| In August 14, 1937, Chiang ordered his troops to take Shanghai at all costs, but initial attempts to break through the Japanese perimeter defences failed. An initial attempt to bomb the Japanese navy docked at Shanghai also failed when the Japanese decoded a secret telegram, and when the Chinese planes missed their targets and hit Shanghai instead, killing hundreds of civilians. In late August and throughout September and October 1937, the Chinese forces were bombarded continuously by the guns of the Japanese navy, by carrier-based bombers, by land-based bombers operating from Japanese-occupied Taiwan, and by armoured units of the Japanese marines and army. The Chinese were mostly restricted to the use of small arms throughout the battle. The Chinese suffered 250,000 casualties, 60% of Chiang's most elite soldiers, while the Japanese took 40,000 or more casualties. | |||

| ===Japan's decision to capture Nanjing=== | |||

| The conflict which would become known as the Second Sino-Japanese War started on July 7, 1937, with a ] which escalated rapidly into a full-scale war in northern China between the armies of China and Japan.<ref name="war22">Jay Taylor, ''The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China'' (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2009), 145–147. Taylor's major primary source for this information is the diary of Chiang Kai-shek, as well as papers written by scholars Zhang Baijia and Donald Sutton.</ref> China, however, wanted to avoid a decisive confrontation in the north and so instead opened a ] by attacking Japanese units in Shanghai in central China.<ref name="war22" /> The Japanese responded by dispatching the ] (SEA), commanded by General ], to drive the Chinese Army from Shanghai.<ref name="battle22">Hattori Satoshi and Edward J. Drea, "Japanese operations from July to December 1937," in ''The Battle for China: Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–1945'', eds. Mark Peattie et al. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011), 169, 171–172, 175–177. The main primary sources cited for this information are official documents compiled by Japan's National Institute for Defense Studies as well as a discussion by Japanese historians and veterans published in the academic journal ''Rekishi to jinbutsu''.</ref> Intense fighting in Shanghai forced Japan's ], which was in charge of military operations, to repeatedly reinforce the SEA, and finally on November 9 an entirely new army, the ] commanded by Lieutenant General ], was also landed at ] just south of Shanghai.<ref name="battle22" /> | |||

| Although the arrival of the 10th Army succeeded at forcing the Chinese Army to retreat from Shanghai, the Japanese Army General Staff had decided to adopt a policy of non-expansion of hostilities with the aim of ending the war.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=23–24, 52, 55, 62 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> On November 7 its ''de facto'' leader Deputy Chief of Staff ] laid down an "operation restriction line" preventing its forces from leaving the vicinity of Shanghai, or more specifically from going west of the Chinese cities of ] and ].<ref name="nanking22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=33, 60, 72 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> The city of Nanjing is roughly {{convert|300|km|mi|abbr=off|sp=us}} west of Shanghai.<ref name="nanking22" /> | |||

| The Japanese finally broke through the Chinese lines by making an amphibious assault at Hangzhou Bay, south of Shanghai, encircling the Chinese army from the rear. On November 11, 1937, the Chinese forces began to retreat, but in such a disorganized manner that they failed to secure their carefully constructed series of defences around Wuxi. As the Chinese army units streamed back into Nanjing, they invited the advances of the Japanese army, which pursued them.<ref>Spence, Jonathan D. (1999) ''The Search for Modern China'', W.W. Norton and Company. pp. 422-423. ISBN 0-393-97351-4.</ref> | |||

| ]]] | |||

| However, a major rift of opinion existed between the Japanese government and its two field armies, the SEA and 10th Army, which as of November were both nominally under the control of the ] led by SEA commander Matsui.<ref name="anatomy22">Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 43, 49–50. The primary sources Yamamoto cites for this information include a wide variety of documents and official communications drawn up by the Army General Staff, as well as the diaries of General Iwane Matsui and Lieutenant General Iinuma Mamoru.</ref> Matsui made clear to his superiors even before he left for Shanghai that he wanted to march on Nanjing.<ref name="kasa22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=50–52 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> He was convinced that the conquest of the Chinese capital city of Nanjing would provoke the fall of the entire Nationalist Government of China and thus hand Japan a quick and complete victory in its war on China.<ref name="kasa22" /> Yanagawa was likewise eager to conquer Nanjing and both men chafed under the operation restriction line that had been imposed on them by the Army General Staff.<ref name="anatomy22" /> | |||

| On November 19 Yanagawa ordered his 10th Army to pursue retreating Chinese forces across the operation restriction line to Nanjing, a flagrant act of insubordination.<ref name="toku22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=59, 65–69 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> When Tada discovered this the next day he ordered Yanagawa to stop immediately, but was ignored. Matsui made some effort to restrain Yanagawa, but also told him that he could send some advance units beyond the line.<ref name="battle22" /> In fact, Matsui was highly sympathetic with Yanagawa's actions<ref>{{Cite book |last=Kazutoshi Hando |publisher=Chuo Koron Shinsha |year=2010 |location=Tokyo |page=137 |language=ja |script-title=ja:歴代陸軍大将全覧: 昭和篇(1) |display-authors=et al}}</ref> and a few days later on November 22 Matsui issued an urgent telegram to the Army General Staff insisting that "To resolve this crisis in a prompt manner we need to take advantage of the enemy's present declining fortunes and conquer Nanking ... By staying behind the operation restriction line at this point we are not only letting our chance to advance slip by, but it is also having the effect of encouraging the enemy to replenish their fighting strength and recover their fighting spirit and there is a risk that it will become harder to completely break their will to make war."<ref name=":122">{{Cite book |last=Toshio Morimatsu |publisher=Asagumo Shinbunsha |year=1975 |location=Tokyo |pages=418–419 |language=ja |script-title=ja:戦史叢書: 支那事変陸軍作戦(1)}}; This work was compiled by Japan's National Institute for Defense Studies based on official documents of the Imperial Japanese Army.</ref> | |||

| ==Aerial bombardment of Nanking== | |||

| ] ]]] | |||

| On September 21, the ], commanded by Prince ], began ] of Nanking. The aerial bombardment campaign consisted of more than 100 fly-overs. Most of the bombs fell on non-military targets. Southern Nanking, the most lively and densely populated area of the city, suffered from the worst bombings. The single most devastating bombing attack occurred on 25 September. From 9:30 am until about 4:30 pm, Japanese planes made five fly-overs, a total of ninety-five sorties, and dropped about 500 bombs, resulting in more than 600 civilian casualties. A refugee camp at Xiaguan was hit, resulting in more than 100 deaths. In addition to bombing infrastructure targets such as power plants, water works and a radio station, the Japanese also dropped bombs on the ] despite the fact that there was a large red cross painted on its rooftop. | |||

| Meanwhile, as more and more Japanese units continued to slip past the operation restriction line, Tada was also coming under pressure from within the Army General Staff.<ref name="anatomy22" /> Many of Tada's colleagues and subordinates, including the powerful Chief of the General Staff Operations Division ], had come around to Matsui's viewpoint and wanted Tada to approve an attack on Nanjing.<ref name="toku22" /> On November 24 Tada finally relented and abolished the operation restriction line "owing to circumstances beyond our control", and then several days later he reluctantly approved the operation to capture Nanjing.<ref name="anatomy22" /> Tada flew to Shanghai in person on December 1 to deliver the order,<ref>{{Cite book |last=Toshio Morimatsu |publisher=Asagumo Shinbunsha |year=1975 |location=Tokyo |page=422 |language=ja |script-title=ja:戦史叢書: 支那事変陸軍作戦(1)}}; This work was compiled by Japan's National Institute for Defense Studies based on official documents of the Imperial Japanese Army.</ref> though by then his own armies in the field were already well on their way to Nanjing.<ref name="anatomy22" /> | |||

| The bombing campaigns on Nanking and on ] evoked protests from the Western powers culminating in a resolution by the Far Eastern Advisory Committee of the ]. An example of the many expressions of indignation came from Lord Cranborne, the British Under-Secretary of State For Foreign Affairs: <blockquote>Words cannot express the feelings of profound horror with which the news of these raids had been received by the whole civilized world. They are often directed against places far from the actual area of hostilities. The military objective, where it exists, seems to take a completely second place. The main object seems to be to inspire terror by the indiscriminate slaughter of civilians...<ref>{{cite book |title=The Illustrated London News, Marching to War 1933–1939 |publisher=Doubleday |year=1989 |page=135}}</ref> | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| === |

===China's decision to defend Nanjing=== | ||

| On November 15, near the end of the Battle of Shanghai, Chiang Kai-shek convened a meeting of the ]'s Supreme National Defense Council to undertake strategic planning, including a decision on what to do in case of a Japanese attack on Nanjing.<ref name="decision22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=109–111 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> Here Chiang insisted fervently on mounting a sustained defense of Nanjing. Chiang argued, just as he had during the Battle of Shanghai, that China would be more likely to receive aid from the great powers, possibly at the ongoing ], if it could prove on the battlefield its will and capacity to resist the Japanese.<ref name="decision22" /> He also noted that holding onto Nanjing would strengthen China's hand in peace talks which he wanted the German ambassador ] to mediate.<ref name="decision22" /> | |||

| By mid-October, Chinese situation in Shanghai had become increasingly dire and the Japanese had made significant gains. The vital town of Dachang fell on October 26 and the Chinese withdrew from metropolitan Shanghai. However, because the ] was scheduled to begin in early November, Chiang Kai-shek ordered his troops to stay in the Shanghai battlefield, instead of retreating to the Wufu and Xicheng Lines to protect ]. Because Shanghai was the most important Chinese city in western eyes, the troops had to fight and hold onto the city as long as possible, rather than moving toward the defense lines along nameless towns en route to Nanking. On November 3, the Conference finally convened in ]. While the western powers were in session to mediate the situation, the Chinese troops were making their final stand in Shanghai and had all hopes for a western intervention that would save China from collapse. | |||

| Chiang ran into stiff opposition from his officers, including the powerful Chief of Staff of the Military Affairs Commission ], the Deputy Chief of Staff ], the head of the Fifth War Zone ], and his German advisor ].<ref name="decision22" /><ref name="yamamoto22">Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 44–46, 72. For this information Yamamoto cites a wide variety of primary sources including the memoirs of Li Zongren and Tang Shengzhi.</ref><ref name="jay22">Jay Taylor, ''The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China'' (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, 2009), 150–152. Most of the sources Taylor cites here come ultimately from Chiang's diaries, but he also utilizes the scholarship of historian Yang Tienshi and the journalist Iris Chang.</ref> They argued that the Chinese Army needed more time to recover from its losses at Shanghai, and pointed out that Nanjing was highly indefensible topographically.<ref name="decision22" /> The mostly gently sloping terrain in front of Nanjing would make it easy for the attackers to advance on the city, while the ] behind Nanjing would cut off the defenders' retreat.<ref name="yamamoto22" /> | |||

| However, the Conference dragged on with little progress. Japan was invited to the Conference twice but declined, thus a mediation effort directly involving Japan was out of the question. Similar to what had transpired in the League of Nations conference, the western powers, including the United States, were still dominated by ] and ]. Thus, nothing effective was formulated. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Chiang, however, had become increasingly agitated over the course of the Battle of Shanghai, even angrily declaring that he would stay behind in Nanjing alone and command its defense personally.<ref name="yamamoto22" /> But just when Chiang believed himself completely isolated, General Tang Shengzhi, an ambitious senior member of the Military Affairs Commission, spoke out in defense of Chiang's position, although accounts vary on whether Tang vociferously jumped to Chiang's aid or only reluctantly did so.<ref name="decision22" /><ref name="yamamoto22" /> Seizing the opportunity Tang had given him, Chiang responded by organizing the Nanjing Garrison Force on November 20 and officially making Tang its commander on November 25.<ref name="yamamoto22" /> The orders Tang received from Chiang on November 30 were to "defend the established defense lines at any cost and destroy the enemy's besieging force".<ref name="yamamoto22" /> | |||

| Though both men publicly declared that they would defend Nanjing "to the last man",<ref name=":222">{{Cite web |last=Masato Kajimoto |year=2000 |title=Introduction – From Marco Polo Bridge to Nanking |url=http://thenankingmassacre.org/2015/07/03/from-shanghai-to-nanking |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150715064628/http://thenankingmassacre.org/2015/07/03/from-shanghai-to-nanking/ |archive-date=July 15, 2015 |access-date=July 19, 2015 |publisher=The Nanking Massacre}} Kajimoto cites news reports in the Chicago Daily News and the American military officer Frank Dorn for this information.</ref><ref>{{Cite web |last=Masato Kajimoto |year=2000 |title=Fall of Nanking – What Foreign Journalists Witnessed |url=http://thenankingmassacre.org/2015/07/04/what-western-journalists-witnessed/ |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150715174636/http://thenankingmassacre.org/2015/07/04/what-western-journalists-witnessed/ |archive-date=July 15, 2015 |access-date=July 19, 2015 |publisher=The Nanking Massacre}} Kajimoto cites news reports in the Chicago Daily News and the American military officer Frank Dorn for this information.</ref> they were aware of their precarious situation.<ref name="yamamoto22" /> On the same day that the Garrison Force was established Chiang officially moved the capital of China from Nanjing to ] deep in China's interior.<ref name="jiken22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=113–115, 120–121 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> Further, both Chiang and Tang would at times give contradictory instructions to their subordinates on whether their mission was to defend Nanjing to the death or merely delay the Japanese advance.<ref name="yamamoto22" /> | |||

| ===Fall of Shanghai=== | |||

| On November 5, the Japanese made amphibious landings at Jinshanwei to surround the Chinese troops still fighting in the Shanghai warzone. Chiang was still waiting for the Conference to produce a favorable response and ordered the troops to continue fighting, even though the worn-out troops were in danger of encirclement from the Jinshanwei landings. It was not until three days later on November 8 that the Chinese central command ordered the troops to retire from the entire Shanghai front to protect ]. This three day delay was enough to cause a breakdown in Chinese command as the units were devastated by continued fighting, and this directly caused the failure to coordinate the defense around the Chinese Hindenburg Lines guarding Nanking. Japanese troops broke Chinese defenses at Kunshan on November 10, broke through the Wufu Line on the 19th, and Xicheng Line on the 26th. | |||

| ==Prelude== | |||

| ==Chinese strategy for the defense of Nanking== | |||

| ===China's defense preparations=== | |||

| ] fighter in the service of the ] in Nanjing]] | |||

| Following the ], the Chinese government began a fast track national defense program with massive construction of primary and auxiliary air force bases around the capital of Nanjing including ], completed in 1934, from which to facilitate aerial defense as well as launching counter-strikes against enemy incursions; on August 15, 1937, the ] launched the first of many heavy ''schnellbomber'' (fast bomber) raids against Jurong Airbase using the advanced ] based upon ]'s blitz-attack concept in an attempt to neutralize the Chinese Air Force fighters guarding the capital city, but was severely repulsed by the unexpected heavy resistance and performance of the Chinese fighter pilots stationed at Jurong, and suffering almost 50% loss rate.<ref>{{Cite news |date=October 5, 2020 |title=88年前,镇江有一座"句容飞机场",它的前世今生很传奇……_手机网易网 |url=https://3g.163.com/news/article_cambrian/FO6AVPJJ0521PJRE.html}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |title=Chinese Air Force vs. The Empire of Japan |url=https://www.warbirdforum.com/cafhist.htm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20071102114835/http://www.warbirdforum.com/cafhist.htm |archive-date=November 2, 2007 |access-date=October 31, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| On November 20 the Chinese Army and teams of conscripted laborers began to hurriedly bolster Nanjing's defenses both inside and outside the city.<ref name="jiken22" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Tokushi Kasahara |year=1992 |script-title=ja:南京防衛戦と中国軍 |journal=南京大虐殺の研究 |language=ja |location=Tokyo |publisher=Banseisha |pages=250–251 |editor=Tomio Hora |display-editors=et al}}. This source cites secret telegrams sent by General Tang Shengzhi.</ref> Nanjing itself was surrounded by formidable stone walls stretching almost {{convert|50|km|mi|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} around the entire city.<ref>Hallett Abend, "Japanese Reach Nanking," ''The New York Times'', December 7, 1937, 1, 13.</ref> The walls, which had been constructed hundreds of years earlier during the ], rose up to {{convert|20|m|ft|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} in height, were {{convert|9|m|ft|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} thick, and had been studded with machine gun emplacements.<ref>F. Tillman Durdin, "Invaders Checked by Many Defenses in Nanking's Walls," ''The New York Times'', December 12, 1937, 1, 48.</ref> By December 6 all the gates into the city had been closed and then barricaded with an additional layer of sandbags and concrete {{convert|6|m|ft|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} thick.<ref name="laststand22">F. Tillman Durdin, "Chinese Fight Foe Outside Nanking," ''The New York Times'', December 8, 1937, 1, 5.</ref><ref name="integer22">{{Cite book |last=Noboru Kojima |publisher=Bungei Shunju |year=1984 |location=Tokyo |pages=165–167 |language=ja |script-title=ja:日中戦争(3)}}; Kojima relied heavily on field diaries for his research.</ref> | |||

| Outside the walls a series of semicircular defense lines were constructed in the path of the Japanese advance, most notably an outer one about {{convert|16|km|mi|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} from the city and an inner one directly outside the city known as the Fukuo Line, or multiple positions line.<ref name="dorn22">Frank Dorn, ''The Sino-Japanese War, 1937–41: From Marco Polo Bridge to Pearl Harbor'' (New York: Macmillan, 1974), 88–90.</ref><ref name="garrison22">David Askew, "Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces," ''Sino-Japanese Studies'', April 15, 2003, 153–154. Here Askew cites American military officer Frank Dorn, journalist F. Tillman Durdin, and the research of the Japanese veterans' association Kaikosha.</ref><ref>"Nanking Prepares to Resist Attack," ''The New York Times'', December 1, 1937, 4.</ref> The Fukuo Line, a sprawling network of trenches, moats, barbed wire, mine fields, gun emplacements, and pillboxes, was to be the final defense line outside Nanjing's city walls. There were also two key high points of land on the Fukuo Line, the peaks of Zijinshan to the northeast and the plateau of Yuhuatai to the south, where fortification was especially dense.<ref name="jiken22" /><ref>{{Cite book |last=Noboru Kojima |publisher=Bungei Shunju |year=1984 |location=Tokyo |page=175 |language=ja |script-title=ja:日中戦争(3)}}; Kojima relied heavily on field diaries for his research.</ref><ref name="zijinshan22">{{Cite book |last=Yoshiaki Itakura |publisher=Nihon Tosho Kankokai |year=1999 |location=Tokyo |pages=77–78 |language=ja |script-title=ja:本当はこうだった南京事件}}</ref> In order to deny the Japanese invaders any shelter or supplies in this area, Tang adopted a strategy of ] on December 7, ordering all homes and structures in the path of the Japanese within one to {{convert|2|km|mi|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} of the city to be incinerated, as well as all homes and structures near roadways within {{convert|16|km|mi|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} of the city.<ref name="jiken22" /> | |||

| ===Chinese retreat from Shanghai=== | |||

| Japanese landings at Jinshanwei forced the Chinese army to retire from the Shanghai front and attempt a breakout. However, Chiang Kai-shek still placed some hope that the ] would result in a ] against Japan by Western Powers. It was not until November 8 that the Chinese central command issued a general retreat to withdraw from the entire Shanghai front. All Chinese units were ordered to move toward western towns such as ], and then from there enter the final defense lines to stop the Japanese from reaching Nanking. By then, the Chinese army was utterly exhausted, and with a severe shortage of ammunition and supplies, the defense was faltering. Kunshan was lost in only two days, and the remaining troops began moving toward the Wufu Line fortifications on November 13. The Chinese army was fighting with the last of its strength and the frontline was on the verge of collapse. | |||

| ===China's forces=== | |||

| In the chaos that ensued many Chinese units were broken up and lost contact with their communications officers who had the maps and layouts to the fortifications. In addition, once they arrived at Wufu Line, the Chinese troops discovered that some of the civilian officials were not there to receive them as they had already fled and had taken the keys with them. The battered Chinese troops, who had just emerged from the bloodbath in Shanghai and were hoping to enter the defense lines, found that they were not able to utilize these fortifications. The Wufu Line was penetrated on November 19, and the Chinese troops then moved toward Xicheng Line, which they were forced to give up on November 26 in the midst of the onslaught. The "Chinese Hindenberg Line," which the government had spent millions to construct and was the final line of defense between Shanghai and Nanking, collapsed in only two weeks. | |||

| The defending army, the Nanjing Garrison Force, was on paper a formidable army of thirteen divisions, including three elite ] divisions plus the super-elite ]. The reality was that nearly all of these units, save for the 2nd Army Group, had been severely mauled from the combat in Shanghai.<ref>David Askew, "Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces," ''Sino-Japanese Studies'', April 15, 2003, 151–152.</ref><ref name="itakura22">{{Cite book |last=Yoshiaki Itakura |publisher=Nihon Tosho Kankokai |year=1999 |location=Tokyo |pages=78–80 |language=ja |script-title=ja:本当はこうだった南京事件}}</ref> By the time they reached Nanjing they were physically exhausted, low on equipment, and badly depleted in total troop strength. In order to replenish some of these units, 16,000 young men and teenagers from Nanjing and the rural villages surrounding it were speedily pressed into service as new recruits.<ref name="jiken22" /><ref name="force22">David Askew, "Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces," ''Sino-Japanese Studies'', April 15, 2003, 163.</ref> | |||

| ] between Nanjing and Shanghai, November 26, 1937. Most wear the ]. One wears a German-style ski cap.]] | |||

| The German trained units, the 36th, ] and ], had each taken heavy casualties in Shanghai and saw their elite quality drop as a result. As of December, each division consisted of between 6,000 and 7,000 troops, of which roughly half were raw recruits.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Askew |first=David |title=Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces |date=2003 |publisher=Sino-Japanese Studies |pages=158}}</ref> In addition to these units, the defenders of Nanjing and the outside defensive lines were composed of four ] (Cantonese) divisions in the 66th and 83rd Corps, five divisions and two brigades from ] in the 23rd Group Army, and two divisions from the ] Central Army in the 74th Corps. Additional units were provided in by the ] and Nanjing Capital Garrison.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=268–270}}</ref> However, most of these units had also suffered very high losses from the months of fighting in and around Shanghai. The 66th Corps had been reduced to half its original size, and its two divisions had to be reorganized into regiments.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Askew |first=David |date=2003 |title=Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces |url=https://chinajapan.org/articles/15/askew15.148-173.pdf |journal=Sino-Japanese Studies |volume=15 |pages=155-156}}</ref> An additional 16,000-18,000 fresh soldiers were brought in from ] in the ranks of the 2nd Army, with 80% of their strength composed of recent recruits.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Li Junshan |publisher=Guoli Taiwan Daxue Zhuban Weiyuanhui |year=1992 |location=Taipei |pages=241–243 |language=zh-hant |script-title=zh:為政略殉: 論抗戰初期京滬地區作戰}}</ref> However, due to the unexpected rapidity of the Japanese advance, most of these new conscripts received only rudimentary training on how to fire their guns on their way to or upon their arrival at the frontlines.<ref name="jiken22" /><ref name="itakura22" /> | |||

| No definitive statistics exist on how many soldiers the Nanjing Garrison Force had managed to cobble together by the time of the battle. ] estimates 100,000,<ref name="echo22">Ikuhiko Hata, "The Nanking Atrocities: Fact and Fable," ''Japan Echo'', August 1998, 51.</ref> and ] who argues in favor of about 150,000.<ref name="jiken22" /> The most reliable estimates are those of David Askew, who estimates via a unit-by-unit analysis a strength of 73,790 to 81,500 Chinese defenders in the city of Nanjing itself.<ref>David Askew, "Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces," ''Sino-Japanese Studies'', April 15, 2003, 173.</ref> These numbers are backed up by the Nanking Garrison staff officer T'an Tao-p'ing, who records a garrison of 81,000 soldiers, a number which Masahiro Yamamoto argues to be one of the most probable figures.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Yamamoto |first=Masahiro |title=Nanking : Anatomy of an Atrocity |date=2000 |publisher=Praeger |pages=43}}</ref> | |||

| ===Decision to move the capital to Wuhan=== | |||

| By mid-November, the Japanese had captured Shanghai. After losing the ], Chiang Kai-shek knew the fall of Nanking would be simply a matter of time. ] and his staff such as ] realized that he could not risk annihilation of their elite troops in a symbolic but hopeless defense of the capital; therefore, in order to preserve these forces for future battles, most of them were withdrawn. Chiang's strategy was to follow the suggestion of his German advisers to draw the Japanese army deep into China utilizing China's vast territory as a defensive strength. He therefore moved his capital to ] until the Japanese captured this city as well following the ]. Chiang's plan was to fight a protracted war of attrition by wearing down the Japanese in the hinterland of China.<ref name="Higashinakano Shudo, Kobayashi Susumu & Fukunaga Shainjiro 2005 author=Higashinakano Shudo, Kobayashi Susumu & Fukunaga Shainjiro">{{citation |web |url=http://www.sdh-fact.com/CL02_1/26_S4.pdf |year=2005 author=Higashinakano Shudo, Kobayashi Susumu & Fukunaga Shainjiro |title=Analyzing the "Photographic Evidence" of the Nanking Massacre (originally published as Nankin Jiken: "Shokoshashin" wo Kenshosuru) |publisher=Soshisha |location=Tokyo, Japan }}</ref> | |||

| ===Japanese mass bombings=== | |||

| Chiang made his decision on November 16, ordering government ministries and agencies to depart from Nanking within three days.<ref>The Current Situation in China (published by Toa Dobunkai),</ref> However, the relocation of the Nationalist government was not publicly announced until noon on November 20. | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Even before the conclusion of the battle of Shanghai, Japan's ] was launching frequent air raids on the city, eventually totaling 50 raids according to the Navy's own records.<ref name="bombing22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=17–18, 34, 40–41 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> The ] had struck Nanjing for the first time on August 15 with ] medium-heavy bombers, but suffered heavy losses in face of the aerial defense from ] Boeing P-26/281 Peashooter and ]/] fighters based primarily at Jurong Airbase for the defense of Nanjing.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Wong Sun-sui |url=https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=947}}</ref> It wasn't until after the introduction of the advanced ] fighter did the Japanese begin to turn the tide in air-to-air combat, and proceed with bombing both military and civilian targets day and night with increasing impunity as the Chinese Air Force losses mounted through continuous attrition; the Chinese did not have the aircraft industry nor comprehensive training regimen to replace men and machines to contend against the ever-growing and ever-improving Japanese war machine.<ref name="bombing22" /> | |||

| However, experienced veteran fighter pilots of the Chinese Air Force still proved a danger against Japanese air power; ] ], ] and ] whom were outnumbered by the superior A5Ms entering Nanjing on October 12, shot down four A5M fighters that day, including Shotai leader W.O. Torakuma who was downed by Chinese fighter ace Col. Gao.<ref>{{Cite web |title=Chinese biplane fighter aces - Kao Chi-Hang |url=http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/china_kao.htm |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201009014225/http://surfcity.kund.dalnet.se/china_kao.htm |archive-date=October 9, 2020 |access-date=September 11, 2020}}</ref> Both Col. Gao and Capt. Liu died in non-aerial combat incidents by the following month as they were preparing to receive improved fighter aircraft design in the ].<ref>{{Cite web |title=Gao Zhihang |url=https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=865 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201021161829/https://ww2db.com/person_bio.php?person_id=865 |archive-date=October 21, 2020 |access-date=September 11, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| ===Evacuation of civilians from Nanking=== | |||

| In mid-November, as the Japanese air raids on Nanking intensified, many wealthy Chinese and Westerners began leaving the city. After Chiang Kai-shek announced that the Nationalist government of China would eventually transfer the capital from Nanking to Chungking and its military headquarters would be shifted to the transitional capital of Hankow on November 20, the scale of evacuation became much larger.<ref>{{cite book |first=Tokushi |last=Kasahara |title=Nanking Nanminku no Hyakunichi |location=Tokyo |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1995 |pages=60}}</ref> | |||

| === Evacuation of Nanjing === | |||

| A week later, on November 27, Commander-in-Chief Tang Shengzhi issued a bulletin to foreign residents of Nanking, urging them to leave, and warning that he could not guarantee the safety of anyone in the city, not even foreigners. | |||

| In the face of Japanese terror bombing and the ongoing advance of the Imperial Japanese Army, the large majority of Nanjing's citizens fled the city, which by early December Nanjing's population had dropped from its former total of more than one million to less than 500,000, a figure which included Chinese refugees from rural villages burned down by their own government's scorched earth policies.<ref name="evacuation22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=31–32, 41 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref><ref>Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 61–62.</ref> Most of those still in the city were very poor and had nowhere else to go.<ref name="evacuation22" /> Foreign residents of Nanjing were also repeatedly asked to leave the city which was becoming more and more chaotic under the strain of bombings, fires, looting by criminals, and electrical outages,<ref name="integer22" /><ref>], "Wie wir aus Nanking flüchteten: Die letzten Tage in der Haupstadt Chinas," ''Frankfurter Zeitung'', December 19, 1937, 9.</ref> but those few foreigners brave enough to stay behind strived to find a way to help the Chinese civilians who had been unable to leave.<ref name="askew22">David Askew, "Westerners in Occupied Nanking," in ''The Nanking Atrocity, 1937–38: Complicating the Picture'', ed. Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008), 227–229.</ref> In late-November ] of them led by German citizen ] established the ] in the center of the city, a self-proclaimed demilitarized zone where civilian refugees could congregate in order to hopefully escape the fighting.<ref name="askew22" /> The safety zone was recognized by the Chinese government,<ref>Rana Mitter, ''Forgotten Ally: China's World War II'' (Boston: Hughton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013), 127–128. Mitter cites the diary of German civilian John Rabe.</ref> and on December 8 Tang Shengzhi demanded that all civilians evacuate there.<ref name="laststand22" /> | |||

| Among those Chinese who did manage to escape Nanjing were Chiang Kai-shek and his wife ], who had flown out of Nanjing on a private plane just before the crack of dawn on December 7.<ref name="TK22">{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |pages=115–116 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref> The mayor of Nanjing and most of the municipal government left the same day, entrusting management of the city to the Nanjing Garrison Force.<ref name="TK22" /> | |||

| As the Japanese army drew closer to Nanking, Chinese civilians fled the city in droves. The people of Nanking fled in panic not only because of the dangers of the anticipated battle but also because they feared the deprivation inherent in the ] strategy that the Chinese troops had implemented in the area surrounding the city.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.interq.or.jp/sheep/clarex/discovery/discovery02.html|title=The Nanking Incident|accessdate=2006-04-19 |archiveurl = http://web.archive.org/web/20060213184811/http://www.interq.or.jp/sheep/clarex/discovery/discovery02.html <!-- Bot retrieved archive --> |archivedate = 2006-02-13}}</ref> | |||

| == Japanese advance on Nanjing (November 11 – December 4) == | |||

| ===The decision to defend Nanking=== | |||

| By the start of December, Japan's Central China Area Army had swollen in strength to over 160,000 men,<ref>Akira Fujiwara, "The Nanking Atrocity: An Interpretive Overview," in ''The Nanking Atrocity, 1937–38: Complicating the Picture'', ed. Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008), 31.</ref> though only about 70,000 of these would ultimately participate in the fighting.<ref>David Askew, "Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces," ''Sino-Japanese Studies'', April 15, 2003, 158. Askew cites the diary of General Iwane Matsui and the research of historian Ikuhiko Hata.</ref> The plan of attack against Nanjing was a ] which the Japanese called "encirclement and annihilation".<ref name="TK22" /><ref>Masahiro Yamamoto, ''The History and Historiography of the Rape of Nanking'' (Tuscaloosa: unpublished Ph.D. thesis, 1998), 505.</ref> The two prongs of the Central China Area Army's pincer were the Shanghai Expeditionary Army (SEA) advancing on Nanjing from its eastern side and the 10th Army advancing from its southern side. To the north and west of Nanjing lay the Yangtze River, but the Japanese planned to plug this possible escape route as well both by dispatching a squadron of ships up the river and by deploying two special detachments to circle around behind the city.<ref name="pincer22">Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 51–52.</ref> The Kunisaki Detachment was to cross the Yangtze in the south with the ultimate aim of occupying ] on the river bank west of Nanjing while the Yamada Detachment was to be sent on the far north route with the ultimate aim of taking Mufushan just north of Nanjing.<ref name="pincer22" /> | |||

| Despite the realization that he could not risk annihilation of the Chinese army in a futile defense of the capital, Chiang was also well aware of the political damage he would suffer if he abandoned Nanking without a fight. Nanking was not only the capital, but also the location of the mausoleum of ], founder of the ]. What Chiang needed was someone who would accept the responsibility for conducting the defense of the city, however hopeless such an effort might be. The search for a willing volunteer was problematic because most of the senior officers were aware of the futility of the effort and the public blame that would be placed upon anyone who attempted to defend Nanking and failed. | |||

| === Fighting retreat of the Chinese Army, breaching the Wufu line === | |||

| Eventually, Tang Shengzhi expressed his willingness to take on the assignment and Chiang Kai-shek named him commander of the Nanking Garrison. There are two somewhat differing accounts of this assignment came about. The first account indicates that Chiang had to plead with Tang several times in order to get him to agree to accept the assignment. | |||

| As of 11 November, all elements of the ] in the Lower Yangtze Theatre were falling back after the ]. Unlike previous instances during the Shanghai campaign where Chinese retreats were conducted with discipline, the Chinese retreat from Shanghai was poorly coordinated and disorganized, in part due to the sheer size of the operation and lack of prior planning. The orders to retreat had been passed top-down in a haphazard manner, and the Chinese army frequently bogged down under its own weight or became congested at ] like bridges. Making matters worse were ] constantly harassing the Chinese columns, adding to the growing casualties and mayhem. Despite their losses, the Chinese army managed to escape destruction by the Japanese forces, who were attempting to encircle them in the last few days of the combat in Shanghai.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=42–43}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Yiding |first=Chen |title=Yangshupu Yunzaobin zhandou |pages=42}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Wakabayashi |first=Bob |title=The Nanking Atrocity, 1937-1938: Complicating the Picture |date=2007 |publisher=Berghahn Books |pages=31}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| On 12 November, the Japanese forces deployed in Shanghai were ordered to pursue the retreating Chinese forces. With most Chinese troops melting away into the retreat, many cities and towns were quickly captured by the Japanese, including ], ] and ]. Japanese troops from the freshly deployed ], consisting of the 6th, 18th, 114th divisions and the Kunisaki Detachment, were eager for combat. However, many of the other Japanese units were exhausted from the fighting in Shanghai, and were slower to follow through with their orders.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=55–58}}</ref> | |||

| Despite the Chinese retreat, the Japanese encountered strong resistance at the Wufu defensive line between Fushan and Lake Tai, which had been nicknamed a "new ]" in Chinese propaganda. At ], Japanese forces had to fight slowly through an interlocking system of concrete ] manned by Chinese soldiers fighting to the death, all whilst Chinese artillery bombarded them with accurate fire.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=84–85}}</ref> The Japanese ] was faced with a similar challenge in ]: contrary to propaganda accounts of the city falling without a fight, Japanese soldiers had to fight through a series of pillboxes in front of the city before painstakingly eliminating pockets of resistance in ]. These operations were concluded by 19 November, with some 1,000 Chinese soldiers killed in Suzhou and another 100 artillery pieces captured, according to Japanese records.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=86}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |title=Dijiu Shituan zhanshi |edition=56 |pages=108–110}}</ref> | |||

| The second account, related by ] in his memoirs, reports that ] held a conference in Nanking with his senior commanders and staff to discuss how to deal with the oncoming onslaught of the Japanese army. In attendance were ], ], ], ], ] and ]. Li relates that he opposed the defense of Nanking because of the strategically disadvantageous geography and the low morale of the Chinese troops, especially after the heavy losses that they had sustained in the Battle of Shanghai. General Bai Chongxi supported Li's stance. Li also proposed declaring Nanking an "]" to avoid unnecessary destruction. | |||

| By late November, the Japanese army was advancing rapidly around ] en route to Nanjing. The Chinese, in order to counter these advances, deployed some five divisions of the Sichuanese 23rd Group Army from warlord ] forces to the southern end of the lake near ], and two more divisions (the 103rd and 112th) to the river fortress ] near the lake's northern end, which had been the site of a naval battle in August. | |||

| Chiang expressed exasperation at these attitudes and pointed out that a failure to defend the capital would have severe consequences to the morale of the troops and China's international prestige. He asserted his opinion that Nanking should be defended to the death. | |||

| === Battles of Lake Tai and Guangde === | |||

| After this pronouncement, He Yingqin (Chief of Staff) and Xu Yongchang (Chief of the Naval General Staff) indicated that they would defer to Chiang's judgment on the matter. General ], leader of Chiang's second team of German military advisors, indicated that he supported Li's proposal to abandon Nanking and urged Chiang to avoid sacrificing his troops and materiel uselessly. At this point, Tang Shengzhi expressed fervent support for Chiang's position that Nanking should be defended to the death based on its symbolic importance to the nation. Chiang eagerly accepted Tang's support for the defense of Nanking and promised to name him commander of the Nanking Garrison.<ref name=LiZongren>{{cite book |title=Memoirs of Li Zongren |last=Li |first=Zongren}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| On November 25, the Japanese 18th Division attacked the town of Sian near ]. The Chinese defenders, underequipped and inexperienced troops from the 145th Division, were overwhelmed by Japanese airpower and tanks and hastily fell back. A counterattack on Sian from the 146th Division was repelled by Japanese armor.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Mingming |first=Gao |title=Riben qinhuashi yanjiu |date=2014 |edition=3rd |pages=92}}</ref> | |||

| On the southwestern edge of ], the ] 144th Division from the 23rd Group Army had dug into a position where the local terrain formed a ] in the local road. When faced with the advance of the Japanese ], the Chinese ambushed the Japanese with hidden ], inflicting heavy casualties on the Japanese.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Huajun |first=Lin |title=Riben qinhuashi yanjiu |date=2014 |edition=2nd |pages=108–109}}</ref> However, fearing the loss of their artillery from retaliatory enemy attacks, the Chinese officers withdrew their artillery in the heat of battle. As a result, the Chinese infantry were slowly pushed back, and finally broke into a retreat towards ] when Japanese troops flanked their positions on the lake's shores via stolen civilian motor boats.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=113–115}}</ref> | |||

| Leaving General Tang Shengzhi in charge of the city for the Battle of Nanking, many of Chiang's advisors left Nanking on December 1, and the president himself left on December 7. The civilian administration of the city was left to an International Committee led by ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| The last days of November saw the five Sichuanese divisions fight fiercely in the vicinity of Guangde, but their defense was hindered by divided leadership and a lack of ] communications. The Japanese overwhelmed the Chinese defenders with artillery, and finally forced the 23rd Group Army back on November 30. Sichuanese division commander ], unable to bear the defeat, shot himself the day after the retreat.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |publisher=Casemate |pages=124–126}}</ref> | |||

| === Battle of Jiangyin === | |||

| ] was a Kuomintang politician and former warlord. Chiang's faith in Tang was due largely to Tang's participation in the ] in 1927, in which he led his forces into Hunan in support of the Nationalists. One of Tang's most distinguished advisors was a Buddhist spiritual teacher, who Tang had used to indoctrinate his troops in the ways of loyalty, and to whom he had deferred for various career decisions. Tang's decision to accept the task of Nanjing's defense, after the rout of Chinese forces from Shanghai was imminent and ongoing, was based largely on the advice of this spiritual advisor.<ref name="SpenceJonathan">Spence, Jonathan D. (1999) ''The Search for Modern China'', W.W. Norton and Company. p. 423. ISBN 0-393-97351-4.</ref> | |||

| On November 29, the Japanese ] attacked the walled town of ] near the Yangtze River after a two-day artillery bombardment. They were confronted by some 10,000 troops from the Chinese 112th and 103rd Divisions, which were composed of a mix of ] veteran exiles and Sichuanese recruits, respectively. Despite encountering ambushes and difficult terrain in the form of 33 hills around the city, the Japanese were able to advance under the cover of land and ] from their ships on the Yangtze.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=119–120}}</ref> Chinese coastal ] mounted on Jiangyin's walls retaliated against the Japanese ships, causing damage to several Japanese vessels. To even the odds, Chinese raiders organized suicide mission to infiltrate Japanese lines at night and destroy enemy tanks with ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Shijiong |first=Wan |title=Nanjing baoweizhan |date=1987 |location=Beijing |pages=92}}</ref> The hills around Jiangyin were the site of vicious fighting, with Mount Ding changing hands several times, resulting in Chinese company commander Xia Min'an being killed in action.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Xu |first=Zhao |title=NBZ |year=1987 |pages=92}}</ref> | |||

| The Japanese eventually managed to overcome the Chinese defenses through a combination of artillery, aircraft and tanks. The Chinese began a withdrawal on December 1, but poor communication resulted in the 112th Division leaving too soon, resulting in a chaotic retreat for the 103rd Division.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=128–131}}</ref> Both divisions had suffered heavy losses in the fighting, and only a portion of their original strength (estimated to be between 1,000 and 2,000 men for the 103rd Division) made it back to Nanjing.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Askew |first=David |date=2003 |title=Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces |journal=Sino-Japanese Studies |pages=171}}</ref> | |||

| ===Plans for the defense of Nanking=== | |||

| Once installed as commander-in-chief of the Nanking Defense Corps, Tang Shengzhi reiterated, this time publicly, his pledge to cast his lot with Nanking. In a press release to foreign reporters, he announced the city would not surrender and would fight to the death. | |||

| During the rest of their advance, the Japanese overcame resistance from the already battered Chinese forces who were being pursued by the Japanese from Shanghai in a "running battle".<ref name="dorn22" /><ref name="force22" /> Here the Japanese were aided by their complete air supremacy, abundance of tanks, the improvised and hastily constructed nature of the Chinese defenses, and also by the Chinese strategy of concentrating their defending forces on small patches of relatively high ground which made them easy to outflank and surround.<ref name="battle22" /><ref>Edward J. Drea and Hans van de Ven, "An Overview of Major Military Campaigns During the Sino-Japanese War, 1937–1945," in ''The Battle for China: Essays on the Military History of the Sino-Japanese War of 1937–1945'', eds. Mark Peattie et al. (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011), 31.</ref><ref name="durdin222">F. Tillman Durdin, "Japanese Atrocities Marked Fall of Nanking," ''The New York Times'', January 9, 1938, 38.</ref> Tillman Durdin reported in one case where Japanese troops surrounded some 300 Chinese soldiers from the 83rd Corps on a cone-shaped peak: "The Japanese set a ring of fire around the peak. The fire, feeding on trees and grass, gradually crept nearer and nearer to the top, forcing the Chinese upward until, huddled together, they were mercilessly machine-gunned to death."<ref>{{Cite news |last=Durdin |first=Tillman |date=December 9, 1937 |title=The New York Times}}</ref> | |||

| Nanking was a walled city with 19 gates, two of which were railway gates. The city is bounded by the ] to the north and to the west. The walls of Nanking were about 15–20 meters high and 10 meters thick. Machine gun emplacements were positioned at the top of the walls. Tang Shengzhi devised a two-stage defense: a defense of the outlying suburbs followed by a last-ditch defense of the city walls and gates. Tang pressed both soldiers and civilians into service in his frantic rush to bolster the city's fortifications. Directed by army officers, a thousand Chinese civilians reinforced existing gun emplacements, concrete pillboxes and dugouts with a trench network extending thirty miles from the city in seven semicircular rings ending at the Yangtze River.<ref>{{cite book |title=Eyewitness Accounts of the Battle of Nanking, Vol. 3}}</ref> The trenches were about 30 to 130 meters wide, about 3 meters deep. | |||

| === Japanese atrocities on the way to Nanjing === | |||

| Tang was able to muster a defense force of about 100,000 soldiers, mostly untrained conscripts, including some troops who had come from the ] battlefield. In defense of the areas surrounding Nanking, ]'s two divisions of 74th Corps guarded Banqiao-Chunhua, ]'s 2nd Corps-group (41st & 48th Divisions) guarded Mengtang-Longtan, and ]'s 66th Corps & ]'s 83rd Corps guarded east and west sides of Mt Tangshan. At Nanking, ]'s 36th Division of 78th Corps guarded north gate, ]'s ] of 72nd Corps and ]'s 87th Division (under Wang Jingjiu's 71st Corps) guarded south gate, and Gu Zhenglun/Gui Yongqing's Central Lecturing Echelon guarded three peaks of ]. Tang Shengzhi retained a company of 6 ground-to-air cannons, commanded by regiment chief ]. On December 2, ] was ordered to Nanking to assist Tang Shengzhi. However, Hu Zongnan went back to ] on December 5 when news broke that Japanese had already deployed along the north bank of the Yangtze. | |||

| General Matsui, along with the Army General Staff, had originally envisaged making a slow and steady march on Nanjing, but his subordinates had disobeyed and instead raced each other to the city.<ref name="fujiwara22">Akira Fujiwara, "The Nanking Atrocity: An Interpretive Overview," in ''The Nanking Atrocity, 1937–38: Complicating the Picture'', ed. Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi (New York: Berghahn Books, 2008), 33, 36.</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Tokushi Kasahara |publisher=Iwanami Shoten |year=1997 |location=Tokyo |page=69 |language=ja |script-title=ja:南京事件}}</ref><ref>Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 57–58. For this information Yamamoto cites a wide variety of primary sources including the diaries of Japanese officers Iwane Matsui and ], and documents drawn up by the 10th Army.</ref> The capture of ] had occurred three days before it was even supposed to start its planned advance, and the SEA had captured ] on December 2 more than five days ahead of schedule.<ref name="fujiwara22" /> On average, the Japanese units were advancing on Nanjing at the breakneck pace of up to {{convert|40|km|mi|abbr=off|sp=us|spell=in}} per day.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Satoshi Hattori |year=2008 |script-title=ja:日中戦争における短期決戦方針の挫折 |location=Tokyo |publisher=Kinseisha |page=92 |script-journal=ja:日中戦争再論 |editor=Gunjishi Gakkai}}. Hattori cites official documents compiled by Japan's National Institute for Defense Studies.</ref> In order to achieve such speeds, the Japanese soldiers carried little with them except weaponry and ammunition.<ref name="supplies22">Masahiro Yamamoto, ''Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity'' (Westport, Connecticut: Praeger, 2000), 52–54.</ref> Because they were marching well ahead of most of their supply lines, Japanese troops usually looted from Chinese civilians along the way, which was almost always accompanied by ].<ref name="supplies22" /> As a Japanese journalist in the 10th Army recorded, "The reason that the is advancing to Nanjing quite rapidly is due to the tacit consent among the officers and men that they could loot and rape as they wish."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Cummins |first=Joseph |title=The World's Bloodiest History |date=2009 |pages=149}}</ref> | |||

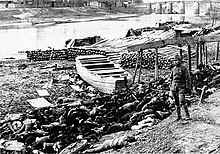

| ] | |||

| The Japanese advance on Nanjing was marked by a trail of arson, rape and murder. The 170 miles between Shanghai and Nanjing were left "a nightmarish zone of death and destruction."<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing, 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |publisher=Casemate |year=2015 |isbn=978-1612002842 |pages=145}}</ref> Japanese planes strafed unarmed farmers and refugees "for fun".<ref>{{Cite book |last=Timberley |first=Harold |title=Japanese Terror in China |publisher=Books for Libraries Press |year=1969 |location=Freeport |pages=91}}</ref> Civilians were subjected to extreme violence and brutality in a foreshadowing of the ]. For example, the Nanqiantou hamlet was set on fire, with many of its inhabitants locked within the burning houses. Two women, one of them pregnant, were raped repeatedly. Afterwards, the soldiers "cut open the belly of the pregnant woman and gouged out the fetus." A crying two-year-old boy was wrestled from his mother's arms and thrown into the flames, while the hysterically sobbing mother and remaining villagers were bayoneted, disemboweled, and thrown into a nearby creek.<ref>{{Cite book |first= |title=Honda |pages=63–65}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |publisher=Casemate |year=2015 |isbn=978-1612002842 |pages=145}}</ref> Many Chinese civilians committed suicide, such as two girls who deliberately drowned themselves near ].<ref>{{Cite book |title=Nishizawa |pages=670}}</ref> | |||

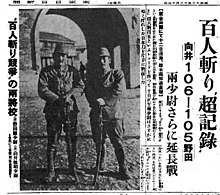

| ]]] | |||

| Many cities and towns were subject to destruction and looting by the advancing Japanese, including but not limited to ], ] and ].<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=58}}</ref> When massacring villages, Japanese forces usually executed the men immediately, while the women and children were raped and tortured first before being murdered.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Shanghai 1937, Stalingrad on the Yangtze |date=2013 |publisher=Casemate |pages=252}}</ref> One atrocity of note was the ] between two Japanese officers, where both men held a competition to see who could behead 100 Chinese captives the first. The atrocity was conducted twice with the second round raising the goal to 150 captives, and was reported on by Japanese newspapers.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Yoshida |first=Takashi |title=The making of the "Rape of Nanking |date=2006 |pages=64}}</ref> | |||

| In a continuation of ] from Shanghai, the Japanese troops executed all Chinese soldiers they captured on their way to Nanjing. Prisoners of war were shot, beheaded, bayonetted and burned to death. In addition, since thousands of Chinese soldiers had dispersed into the countryside, the Japanese implemented "mopping-up operations" in the countryside to deny the Chinese shelter, where all buildings without any immediate value to the Japanese army were burned down, and their inhabitants slaughtered.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=197–199}}</ref> | |||

| ==="Scorched-earth" strategy=== | |||

| On July 31, the Kuomintang had issued a statement that they were determined to turn every Chinese national and every piece of their soil into ash, rather than turn them over to the opponent.<ref name=PhotographicEvidence>{{cite web |url=http://www.sdh-fact.com/CL02_1/26_S4.pdf |year=2005 |author=Higashinakano Shudo, Kobayashi Susumu & Fukunaga Shainjiro |title=Analyzing the "Photographic Evidence" of the Nanking Massacre (originally published as Nankin Jiken: "Shokoshashin" wo Kenshosuru) |publisher=Soshisha |location=Tokyo, Japan }}</ref> | |||

| == Battle for Nanjing's outer line of defense (December 5–9) == | |||

| The Nanking garrison force set fire to buildings and houses in the areas close to Xiakuan to the north as well as in the environs of the eastern and southern city gates.<ref name=PhotographicEvidence /> Chinese troops blocked roads, scuttled boats and set fire to nearly every city, town, and village on the outskirts of the city. They burned down structures within the grounds of the Zhongshan Mausoleum, as well as the stately Ministry of Communications building. They incinerated nearly all of the Xiaguan district. Targets within and outside of the city walls—such as military barracks, private homes, the Chinese Ministry of Communication, forests and even entire villages—were burnt to cinders, at an estimated value of 20 to 30 million (1937) US dollars.<ref name="doomed">{{cite web|url=http://www.geocities.com/nankingatrocities/Fall/fall_01.htm|title=Five Western Journalists in the Doomed City|accessdate=2006-04-19|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20050325115933/http://www.geocities.com/nankingatrocities/Fall/fall_01.htm|archivedate=2005-03-25}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ne.jp/asahi/unko/tamezou/nankin/1937-12-08-NewYorkTimesTillmanDurdin.html|title=Chinese Fight Foe Outside Nanking; See Seeks's Stand|accessdate=2006-04-19}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ne.jp/asahi/unko/tamezou/nankin/1937-12-09-NewYorkTimesHallettAbend.html|title=Japan Lays Gain to Massing of Foe|accessdate=2006-04-19}}</ref> | |||

| === Battles of Chunhua and the Two Peaks === | |||

| On December 5, Chiang Kai-shek paid a visit to a defensive encampment near ] to boost the morale of his men but was forced to leave when the Imperial Japanese Army began their attack on the battlefield.<ref name="kojima22">{{Cite book |last=Noboru Kojima |publisher=Bungei Shunju |year=1984 |location=Tokyo |pages=164, 166, 170–171, 173 |language=ja |script-title=ja:日中戦争(3)}}; Kojima relied heavily on field diaries for his research.</ref> On that day the rapidly moving forward contingents of the SEA occupied Jurong and then arrived near Chunhua(zhen), a town 15 miles southeast of Nanjing and a key point of the capital's outer line of defense which would put Japanese artillery in range of the city.<ref name="garrison22" /><ref name="TK22" /><ref name="kojima22" /> Chunhua was defended by China's 51st Division of the 74th Corps, veterans of the fighting from Shanghai. Despite facing difficulties in using the fortifications around the town due to a lack of keys, the 51st Division had managed to establish a three-line defense with pillboxes, hidden machine gun nests, two rows of barbed wire and an anti-tank ditch.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937, Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=163}}</ref> | |||

| Battle had already begun on 4 December, when 500 soldiers from the Japanese 9th division attacked Chinese forward positions in Shuhu, a small town several miles away from Chunhua. The Chinese company in Shuhu held out for two days, and at one point deployed a tank platoon against the Japanese infantry, losing 3 armored vehicles in exchange for 40 Japanese casualties. By 6 December, the defenders abandoned their positions, and some 30 survivors fought their way out of Shuhu.<ref name=":03">{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=163–165}}</ref> | |||

| On December 7, 1937, correspondent ] sent the following special dispatch to The New York Times. | |||

| <blockquote> | |||

| Between Tangshan and Nanking barricades were ready along the highway every mile or so, and nearer the capital there raged huge fires set by the Chinese in the course of clearing the countryside of buildings that might protect the invaders from gunfire. In one valley a whole village was ablaze. | |||

| </blockquote> | |||

| The Japanese pushed to Chunhua, but were faced with heavy resistance by the 51st Division, who inflicted heavy casualties on the Japanese in preplanned ] with machine guns and artillery attacks. Nevertheless, Japanese artillery strikes enabled their infantry to capture the first defensive line, while a well-timed attack by six Japanese bombers enabled a deeper breakthrough. The Japanese left flank managed to penetrate behind Chunhua on December 7, but the final breakthrough came on December 8 when an entire regiment of the 9th Division that had lagged behind entered the fray.<ref name="kojima22" /> The Chinese defenders, who had endured incessant shelling for days and suffered more than 1,500 casualties, finally cracked under the renewed Japanese assault and withdrew.<ref name=":03" /> | |||

| One consequence of these "scorched-earth" strategy operations was that many citizens were hindered in their efforts to flee the city due to the destruction of the transportation infrastructure. It's not clear whether this consequence was intentional or not. According to one source, Tang placed the 35th and 72nd divisions at the port to prevent people from fleeing Nanking in accordance with instructions from ]'s general headquarters at ]. | |||

| The SEA also took the fortress at ] and the spa town of Tangshuizhen the same day.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Yoshiaki Itakura |publisher=Nihon Tosho Kankokai |year=1999 |location=Tokyo |pages=75, 79 |language=ja |script-title=ja:本当はこうだった南京事件}}</ref> Meanwhile, on the south side of the same defense line, armored vehicles of Japan's 10th Army charged the Chinese positions at ] (General's Peak) and Niushoushan (Ox Head Peak) defended by China's 58th Division of the 74th Corps.<ref name="kojima22" /> The Chinese defenders had dug in on the high ground, and possessed ] powerful enough to destroy Japanese armor. Multiple Japanese ] were destroyed, and in some cases, valiant Chinese soldiers armed with hammers jumped onto the vehicles and banged repeatedly on their roofs shouting "Get out of there!" Gradually, through its coordinated use of armor, artillery and infantry, the Japanese managed to slowly dislodge the Chinese defenders.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Harmsen |first=Peter |title=Nanjing 1937: Battle for a Doomed City |date=2015 |publisher=Casemate |pages=170–171}}</ref> On December 9, after darkness fell on the battlefield, the 58th Division was finally overwhelmed and withdrew, having suffered, according to its own records, 800 casualties.<ref name="kojima22" /> | |||

| ==Road to Nanking== | |||

| === Defensive stand of the 2nd Army and the Battle for Old Tiger's Cave === | |||

| ===Changes in the Japanese command structure=== | |||

| On December 6, the Japanese 16th Division attacked Chinese positions 14 miles east of Nanjing. The Chinese defenders were composed of fresh troops from the 2nd Army, and had dug in onto a ridgeline to meet the Japanese assault. Japanese aircraft and artillery shelled the Chinese defenses relentlessly, inflicting extensive damage and confusion. The Chinese defenders were also hampered by their own inexperience, with some soldiers forgetting to ignite the fuses of their hand grenades before throwing them. Only a cadre of experienced officers and NCO's prevented a total collapse, and enabled the 2nd Army to hold an organized defense for three days until December 9, when they were forced back to Qixia.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Jun |first=Guo |title=Nanjing Baoweizhan dangan |date=2018 |pages=367–368}}</ref> The fighting had resulted in 3,919 killed and 1,099 wounded for the 2nd Army, an almost four-to-one death-injury ratio.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Yamamoto |first=Mashiro |title=Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity |date=2000 |publisher=Praeger |pages=89}}</ref> | |||

| In October, the Shanghai Expeditionary Force (SEF) was reinforced by the ] commanded by Lieutenant General ]. On 7 November, ] (CCAA) was created by combining the SEF and the 10th Army, with Matsui appointed as its commander-in-chief concurrently with that of the SEF. The newly formed Central China Area Army was composed of the Shanghai Expeditionary Army (the nucleus of which was the 16th, 9th, 13th, 3rd, 11th, and 101st Divisions) and the Tenth Army (6th, 18th, and 114th Divisions).<ref>{{cite web |last=Askew |first=David |title=Defending Nanking: An Examination of the Capital Garrison Forces |url=http://www.chinajapan.org/articles/15/askew15.148-173.pdf |accessdate=2009-04-26}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||