| Revision as of 03:18, 15 November 2012 editCurb Chain (talk | contribs)18,691 edits →Recent history and popularization: unsourced← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 20:31, 9 January 2025 edit undoLizardJr8 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers, Rollbackers97,740 editsm Reverted edits by 80.46.17.237 (talk): editing tests (HG) (3.4.12)Tags: Huggle Rollback | ||

| (593 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Type of African goblet drum}} | |||

| {{Distinguish|Djambe}} | |||

| {{Redirect|Jembe|the garden tool|Hoe (tool)}} | {{Redirect|Jembe|the garden tool|Hoe (tool)}} | ||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Infobox Instrument | {{Infobox Instrument | ||

| |name=Djembe | | name = Djembe | ||

| |background=percussion | | background = percussion | ||

| | image = Lenke djembe from Mali.jpeg{{!}}alt=Brown goblet-shaped wood and leather drum with blue rope on an alabaster background | |||

| |image=Lenke_djembe_from_Mali.jpeg | |||

| |image_capt=Lenke wood djembe from Mali | | image_capt = Lenke wood djembe from Mali | ||

| |classification=] | | classification = ] | ||

| |hornbostel_sachs=211.261.1 | | hornbostel_sachs = 211.261.1 | ||

| |hornbostel_sachs_desc=Directly struck ], ], one membrane, open at one end | | hornbostel_sachs_desc = Directly struck ], ], one membrane, open at one end | ||

| |range=65–1000 Hz. | | range = 65–1000 Hz. | ||

| |related=], ], ], ] | | related = ], ], ], ] | ||

| |articles=], ] | | articles = ], ] | ||

| |musicians=], ], ], ], ] | | musicians = ], ], ], ], ] | ||

| ], | |||

| |developed=c. 1200 AD | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| | developed = c. 1200 AD | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| A '''djembe''' ({{IPAc-en|icon|ˈ|dʒ|ɛ|m|.|b|ɛ}} {{respell|JEM|be}}) (also spelled '''djembé''', '''jembe''', '''jenbe''', '''djimbe''', '''jimbe''', or '''dyinbe'''<ref>{{cite book|first=Marianne|last=Friedländer|title=Lehrbuch des Malinke|isbn=978-3-324-00334-6|publisher=Langenscheidt|year=1992|edition=1st|language=German|location=Leipzig|pages=279,159–160}}</ref><ref name="Charry">{{cite journal|last=Charry|first=Eric|title=A Guide to the Jembe|accessdate=11 January 2012|month=April|year=1996|journal=Percussive Notes|volume=34|issue=2|url=http://echarry.web.wesleyan.edu/jembearticle/article.html|accessdate=12 January 2012|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/64pkJpYCG|archivedate=20 January 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref>) is a rope-tuned skin-covered ] played with bare hands. | |||

| According to the ] people in ], the name of the djembe comes from the saying "Anke djé, anke bé" which translates to "everyone gather together in peace" and defines the drum's purpose. In the ], "djé" is the verb for "gather" and "bé" translates as "peace".<ref>{{cite book|last1=Doumbia|first1=Abdoul|last2=Wirzbicki|first2=Matthew|title=Anke Djé Anke Bé, Volume 1|publisher=3idesign|year=2005|page=86|isbn= 9780977484409}}</ref> | |||

| A '''djembe''' or '''jembe''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|dʒ|ɛ|m|b|ei}} {{respell|JEM|bay}}; from ] ''jembe'' {{IPA-xx|dʲẽbe|}},<ref>{{cite book|first=Marianne|last=Friedländer|title=Lehrbuch des Malinke|isbn=978-3-324-00334-6|publisher=Langenscheidt|year=1992|edition=1st|language=de|location=Leipzig|pages=279, 159–160}}</ref> ]: {{lang|dmn|ߖߋ߲߰ߓߋ}}<ref>{{cite magazine|title=Les Recherches linguistiques de l'école N'ko|author1=Faya Ismael Tolno|url=http://kanjamadi.com/dalukende19.pdf|magazine=Dalou Kende|language=fr|issue=19|page=7|date=September 2011|publisher=Kanjamadi|access-date=17 December 2020}}</ref>) is a rope-tuned skin-covered ] played with bare hands, originally from ]. | |||

| The djembe has a body (or shell) carved of ] and a ] made of untreated (not ]) ], most commonly made from ]. Excluding rings, djembes have an exterior diameter of 30–38 cm (12–15 in) and a height of 58–63 cm (23–25 in). The majority have a diameter in the 13 to 14 inch range. The weight of a djembe ranges from 5 kg to 13 kg (11–29 lb) and depends on size and shell material. A medium-size djembe carved from one of the ] (including skin, rings, and rope) weighs around 9 kg (20 lb). | |||

| According to the ] in ], the name of the djembe comes from the saying "Anke djé, anke bé" which translates to "everyone gather together in peace" and defines the drum's purpose. In the ], "djé" is the verb for "gather" and "bé" translates as "peace."<ref>{{cite book|last1=Doumbia|first1=Abdoul|last2=Wirzbicki|first2=Matthew|title=Anke Djé Anke Bé, Volume 1|publisher=3idesign|year=2005|page=86|isbn=978-0-9774844-0-9}}</ref> | |||

| The djembe has a body (or shell) carved of ] and a ] made of untreated (not ]) ], most commonly made from ]. Excluding rings, djembes have an exterior diameter of 30–38 cm (12–15 in) and a height of 58–63 cm (23–25 in). The majority have a diameter in the 13 to 14 inch range. The weight of a djembe ranges from 5 kg to 13 kg (11–29 lb) and depends on size and shell material. A medium-size djembe carved from one of the traditional woods (including skin, rings, and rope) weighs around 9 kg (20 lb). | |||

| The djembe can produce a wide variety of sounds, making it one of the most versatile drums. The drum is very loud, allowing it to be heard clearly as a solo instrument over a large percussion ensemble. The ] say that a skilled drummer is one who "can make the djembe talk", meaning that the player can tell an emotional story. (The djembe was never used by the Malinké as a ] to send messages.) | |||

| The djembe can produce a wide variety of sounds, making it an extremely versatile drum. The drum is very loud, allowing it to be heard clearly as a solo instrument over a large percussion ensemble. The ] say that a skilled drummer is one who "can make the djembe talk", meaning that the player can tell an emotional story (the Malinké never used the djembe as a ]). | |||

| Traditionally, the djembe is played only by men, as are the '']'' that always accompany the djembe. Conversely, other percussion instruments that are commonly played as part of an ensemble, such as the '']'' (a hollowed-out gourd covered with a net of beads), ''karignan'' (a tubular bell), and ''kese kese'' (a woven basket rattle), are usually played by women. Even today, it is rare to see women play djembe or dunun in West Africa and African women express astonishment when they do see a female djembe player.<ref name="Flaig" /> (See also ], below.) | |||

| Traditionally, the djembe is played only by men, as are the '']'' that always accompany the djembe. Conversely, other percussion instruments that are commonly played as part of an ensemble, such as the '']'' (a hollowed-out gourd covered with a net of beads), ''karignan'' (a tubular bell), and '']'' (a woven basket rattle), are usually played by women. Even today, it is rare to see women play djembe or dunun in West Africa, and African women express astonishment when they do see a female djembe player.<ref name="Flaig" /> | |||

| ==Origin== | ==Origin== | ||

| ] c. 1350 AD|alt=Map of the Mali Empire, circa 1350 AD]] | ] c. 1350 AD]] | ||

| There is general agreement that the origin of the djembe is associated with the ] caste of blacksmiths, known as '']''. The wide dispersion of the djembe drum throughout |

There is general agreement that the origin of the djembe is associated with the ] caste of blacksmiths, known as '']''. The wide dispersion of the djembe drum throughout West Africa may be due to Numu migrations during the first millennium AD.<ref name="Charry">{{cite journal |last=Charry |first=Eric |title=A Guide to the Jembe |date=April 1996 |journal=Percussive Notes |volume=34 |issue=2 |url=http://echarry.web.wesleyan.edu/jembearticle/article.html |access-date=January 12, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120116093252/http://echarry.web.wesleyan.edu/jembearticle/article.html |archive-date=January 16, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> Despite the association of the djembe with the Numu, there are no hereditary restrictions on who may become a ''djembefola'' (literally, "one who plays the djembe"). This is in contrast to instruments whose use is reserved for members of the '']'' caste, such as the '']'', '']'', and '']''.<ref name="MM" /> (The djembe is not a griot instrument.)<ref name="Polak Bamako"/> Anyone who plays djembe is a djembefola—the term does not imply a particular level of skill. | ||

| Geographically, the traditional distribution of the djembe is associated with the ],<ref>{{cite book|first1=Séga|last1=Sidibé|first2=Cyril|last2=Piquet|title=Sega Kan Do|publisher=ID Music|isbn=978-2-7466-1384-3|year=2010|location=Courbevoie Cedex, France}}</ref> which dates back to 1230 AD and included parts of the modern-day countries of ], ], ], ], ], and ]. However, due to the lack of written records in West African countries, it is unclear whether the djembe predates or postdates the Mali Empire. It seems likely that the history of the djembe reaches back for at least several centuries |

Geographically, the traditional distribution of the djembe is associated with the ],<ref>{{cite book|first1=Séga|last1=Sidibé|first2=Cyril|last2=Piquet|title=Sega Kan Do|publisher=ID Music|isbn=978-2-7466-1384-3|year=2010|location=Courbevoie Cedex, France}}</ref> which dates back to 1230 AD and included parts of the modern-day countries of ], ], ], ], ], and ]. However, due to the lack of written records in West African countries, it is unclear whether the djembe predates or postdates the Mali Empire. It seems likely that the history of the djembe reaches back for at least several centuries and possibly more than a millennium.<ref name="MM" /> | ||

| The goblet shape of the djembe suggests that it originally may have been created from a ]. (Mortars are widely used throughout West Africa for food preparation.)<ref name="Billmeier" /> | The goblet shape of the djembe suggests that it originally may have been created from a ]. (Mortars are widely used throughout West Africa for food preparation.)<ref name="Billmeier" /> | ||

| There are a number of different creation myths for the djembe. Serge Blanc<ref name="Blanc" /> relates the following myth, originally reported by ]:<ref name="Zemp">{{cite book|title=Musique dan: La musique dans la pensée et la vie sociale d'une societé africaine|year=1971|first=Hugo|last=Zemp|publisher=Mouton|location=Paris|language=French}}</ref> | |||

| <blockquote><poem>Long ago, men did not know the drum; the chimpanzees owned it. At that time, before guns, there was a trapper named So Dyeu. He was the leader of all the trappers. The chimpanzees often came near his camp. One day, he went hunting and noticed the chimpanzees eating fruit in the trees. They were entertaining themselves with a drum. The hunter said, "This thing they are beating is beautiful. I will set a trap." | |||

| He dug a hole and laid a trap. The next day, he heard the chimpanzees crying. The baby chimpanzees cried, the young chimpanzees cried, and the old chimpanzees cried. The trap had caught the chimpanzee drummer. | |||

| The hunter called his dog and went into the forest. The chimpanzees fled as he approached, leaving behind them the drummer, caught in the trap with his drum. The hunter took the drum and brought it to the village. That is why the chimpanzees don't have drums anymore and why they beat their chests with their fists. That's why they say "gugu". It isn't a real drum that we hear today, it is the chimpanzee who has stopped breathing and is beating his chest. | |||

| When the hunter arrived at the village, he gave the drum to the chief, who said, "We have heard the voice of this thing for a long time, but no-one had seen it until now. You have brought it to us; you have done well. Take my first daughter for your first wife." | |||

| From that day on the person who played the drum was called "tambourine player". That is how we got the drum. The chimpanzees of the bush were men who went astray. They had done wrong, so God cursed them and they became chimpanzees. Today, they no longer have drums and they have to beat their chests.</poem></blockquote> | |||

| ==Recent history== | ==Recent history== | ||

| Prior to the 1950s and the ], the djembe was known only in its |

Prior to the 1950s and the ], due to the very limited travel of native Africans outside their own ethnic group, the djembe was known only in its original area. | ||

| ===National ballets=== | ===National ballets=== | ||

| ] in |

] in ], ], 1962]] | ||

| The djembe first came to the attention of audiences outside West Africa with the efforts of ], who, in 1952, founded |

The djembe first came to the attention of audiences outside West Africa with the efforts of ], who, in 1952, founded ]. The ballet toured extensively in Europe and was declared Guinea's first national ballet by Guinea's first president, ], after Guinea gained independence in 1958, to be followed by two more national ballets, the Ballet d'Armee in 1961 and Ballet Djoliba in 1964.<ref name="Billmeier" /> | ||

| Touré's policies alienated Guinea from the West and he followed the ] model of using the country's culture and music for promotional means.<ref name="Meredith">{{cite book|title=The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence|last=Meredith|first=Martin|year=2006|publisher=Jonathan Ball Publishers|location=Johannesburg, South Africa|isbn=978-1-86842-251-7}}</ref> He and Fodéba Keïta, who had become a close friend of Touré, saw the ballets as a way to secularize traditional customs and rites of different ethnic groups in Guinea. The ballets combined rhythms and dances from widely different spiritual backgrounds in a single performance, which suited the aim of Touré's demystification program of "doing away with 'fetishist' ritual practices".<ref name="Flaig">{{cite thesis|first=Vera|last=Flaig|title=The Politics of Representation and Transmission in the Globalization of Guinea's Djembé|url=http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/75801/1/vhflaig_1.pdf| |

Touré's policies alienated Guinea from the West and he followed the ] model of using the country's culture and music for promotional means.<ref name="Meredith">{{cite book|title=The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence|last=Meredith|first=Martin|year=2006|publisher=Jonathan Ball Publishers|location=Johannesburg, South Africa|isbn=978-1-86842-251-7|title-link=The State of Africa: A History of Fifty Years of Independence}}</ref> He and Fodéba Keïta, who had become a close friend of Touré, saw the ballets as a way to secularize traditional customs and rites of different ethnic groups in Guinea. The ballets combined rhythms and dances from widely different spiritual backgrounds in a single performance, which suited the aim of Touré's demystification program of "doing away with 'fetishist' ritual practices".<ref name="Flaig">{{cite thesis |first=Vera |last=Flaig |title=The Politics of Representation and Transmission in the Globalization of Guinea's Djembé |url=http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/75801/1/vhflaig_1.pdf |access-date=January 15, 2012 |publisher=University of Michigan |year=2010 |degree=Ph.D. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140428014120/http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/75801/1/vhflaig_1.pdf |archive-date=April 28, 2014 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref><ref name="Berliner">{{cite journal|first=David|last=Berliner|title=An 'Impossible' Transmission: Youth Religious Memories in Guinea-Conakry|journal=American Ethnologist|volume=32|issue=4|pages=576–592|date=November 2005|doi=10.1525/ae.2005.32.4.576}}</ref> | ||

| Touré generously supported the ballets (to the point of building a special rehearsal and performance space in his palace for Ballet Djoliba) and, until his death in 1984, financed extensive world-wide performance tours, which brought the djembe to the attention of Western audiences.<ref name="Djembefola">{{cite video|title= |

Touré generously supported the ballets (to the point of building a special rehearsal and performance space in his palace for Ballet Djoliba) and, until his death in 1984, financed extensive world-wide performance tours, which brought the djembe to the attention of Western audiences.<ref name="Djembefola">{{cite video |title=Djembefola |people=Laurent Chevallier (director), Mamady Keïta (himself) |year=1991 |url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0216717/ |access-date=March 23, 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170211023704/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0216717/ |archive-date=February 11, 2017 |df=mdy }}</ref><ref name="Ballet Africains">{{cite web |title=Les Ballets Africains |url=http://www.lesballetsafricains.net/ |access-date=January 15, 2012 |work=Official website sanctioned by the Department of Culture of the Republic of Guinea |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120116231709/http://www.lesballetsafricains.com/ |archive-date=January 16, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> Other countries followed Touré's example and founded national ballets in the 1960s, including Ivory Coast (Ballet Koteba), Mali (]),<ref name="theatre encyclopaedia">{{cite book|title=The World Encyclopedia of Contemporary Theatre: Africa|volume=3|publisher=Routledge|location=London|isbn=978-0-415-05931-2|date=June 24, 1997|pages=|last1=Diawara|first1=Gaoussou|last2=Diawara|first2=Victoria|last3=Koné|first3=Alou|editor1-last=Diakhate|editor1-first=Ousmane|editor2-last=Eyoh|editor2-first=Hansel Ndumbe|editor3-last=Rubin|editor3-first=Don|url=https://archive.org/details/worldencyclopedi0002unse_j6c2/page/448}}</ref> and Senegal (Le Ballet National du Senegal), each with its own attached political agenda.<ref name="Castaldi">{{cite book|title=Choreographies of African Identities: Negritude, Dance, and the National Ballet of Senegal|first=Francesca|last=Castaldi|year=2006|publisher=University of Illinois Press|isbn=978-0-252-07268-0}}</ref> | ||

| ===Emigration=== | ===Emigration=== | ||

| In the |

In the United States, Ladji Camara, a member of Ballets Africains in the 1950s, started teaching djembe in the 1960s and continued to teach into the 1990s. Camara performed extensively with ] during the 1970s, greatly raising awareness of the instrument in the US.<ref name="Camara">{{cite encyclopedia |url=http://africanmusic.org/artists/ladji.html |title=Papa Ladji Camara |first=Andy |last=Wassserman |encyclopedia=The African Music Encyclopedia: Music from Africa and the African Diaspora |access-date=January 13, 2012 |year=1995 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120112000208/http://africanmusic.org/artists/ladji.html |archive-date=January 12, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | ||

| After the death of Sekou Touré in 1984, funding for the ballets dried up and a number of djembefolas (who were never paid well by the ballets<ref>{{cite journal|title=Rare German Radio Interviews with Famoudou Konate|journal=Percussive Notes |

After the death of Sekou Touré in 1984, funding for the ballets dried up and a number of djembefolas (who were never paid well by the ballets<ref>{{cite journal |title=Rare German Radio Interviews with Famoudou Konate |journal=Percussive Notes |volume=39 |issue=6 |date=December 2001 |editor-first=Lilian |editor-last=Friedberg |url=http://chidjembe.com/fkusaradio.html |access-date=January 12, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120413123345/http://chidjembe.com/fkusaradio.html |archive-date=April 13, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref>) emigrated and made regular teaching and performance appearances in the west, including ] (Belgium, US), ] (Germany), and Epizo Bangoura (France, US, and Australia).<ref name="Epizo">{{cite web |url=http://epizob.com/e/biography.html |access-date=January 13, 2012 |title=Who is Epizo Bangoura? |work=Epizo Bangoura official website |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160303234605/http://epizob.com/e/biography.html |archive-date=March 3, 2016 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref><ref name="Files">{{cite thesis |first=Frederick Rimes |last=Files |title=Hairy drums, live sampling: Ethos Percussion Group commissions of 2004 and their "extra-conservatory" elements |url=http://gradworks.umi.com/34/99/3499233.html |access-date=July 28, 2013 |publisher=City University of New York |year=2012 |degree=Ph.D. |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160304052603/http://gradworks.umi.com/34/99/3499233.html |archive-date=March 4, 2016 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> A number of other djembefolas—M'bemba Bangoura, ], ], Mohamed "Bangouraké" Bangoura, and Babara Bangoura, among others—followed their example, establishing a sizeable population of expatriate performers and teachers in many Western countries. | ||

| ===Film=== | ===Film=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The 1991 documentary ''Djembefola'' by Laurent Chevallier depicts Mamady Keïta's return to the village of his birth after a 26-year absence. Upon release, the movie won |

The 1991 documentary ''Djembefola''<ref name="Djembefola"/> by Laurent Chevallier depicts Mamady Keïta's return to the village of his birth after a 26-year absence. Upon release, the movie won the Wisselzak Trophy and Special Jury Award at the ], and the Audience Award at the ], and brought the djembe to the attention of a wide audience.<ref>{{cite web |title=Laurent Chevallier – Awards – IMdb |website=] |url=https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0156694/awards |access-date=March 4, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091009102321/http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0156694/awards |archive-date=October 9, 2009 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |title=Marseille Festival of Documentary Film (1991) |website=] |url=https://www.imdb.com/event/ev0000421/1991 |access-date=October 22, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924182413/http://www.imdb.com/event/ev0000421/1991 |archive-date=September 24, 2015 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | ||

| A 1998 follow-up documentary, ''Mögöbalu'' (also by Chevallier), contains concert footage uniting four master drummers (], Mamady Keita, Famoudou Konaté, and ]) on stage. |

A 1998 follow-up documentary, ''Mögöbalu''<ref>{{cite video |title=Mögöbalu |people=Laurent Chevallier (director) |year=1998 |url=https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2321435/ |access-date=March 23, 2013 |url-status=live |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160323025818/http://www.imdb.com/title/tt2321435/ |archive-date=March 23, 2016 |df=mdy }}</ref> (also by Chevallier), contains concert footage uniting four master drummers (], Mamady Keita, Famoudou Konaté, and ]) on stage. | ||

| The Oscar-nominated 2007 drama '']'' ensured that the djembe was noticed internationally by mainstream viewers. | The Oscar-nominated 2007 drama '']'' ensured that the djembe was noticed internationally by mainstream viewers. | ||

| ===Western music=== | ===Western music=== | ||

| The djembe has been used by many |

The djembe has been used by many western artists, including ], ], and ], raising awareness of the instrument with western audiences.<ref name="Simon">{{cite web |title=Evolution of the Instrument: Djembe |url=http://revivalist.okayplayer.com/2011/07/05/evolution-of-the-instrument-djembe/ |publisher=The Revivalist |access-date=September 16, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120317144054/http://revivalist.okayplayer.com/2011/07/05/evolution-of-the-instrument-djembe/ |archive-date=March 17, 2012 |url-status=dead |df=mdy }}</ref><ref name="Cirque">{{cite web |title=Cirque du Soleil's percussion setup in pictures |url=http://beta.musicradar.com/news/drums/the-cirque-du-soleils-percussion-setup-in-pictures-462225/6 |access-date=September 16, 2012 |work=Congas, djembes and more |publisher=musicradar |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130129074411/http://beta.musicradar.com/news/drums/the-cirque-du-soleils-percussion-setup-in-pictures-462225/6 |archive-date=January 29, 2013 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | ||

| ===Recordings=== | ===Recordings=== | ||

| Recordings of the djembe far surpass the number of recordings of any other African drum. Beginning in the late 1980s, a slew of djembe-centric recordings was released, a trend that, as of |

Recordings of the djembe far surpass the number of recordings of any other African drum. Beginning in the late 1980s, a slew of djembe-centric recordings was released, a trend that, as of 2014, shows no sign of abating. This is significant because these recordings are driven by the demand of western audiences; there are almost no djembe recordings within African markets.<ref name="MM" /> | ||

| ===Educational material=== | ===Educational material=== | ||

| Among the earliest educational resources available to a student of the djembe were an educational VHS tape by Babatunde Olatunji released in 1993,<ref name="Olatunji">{{cite video|title=African Drumming|first=Babatunde|last=Olatunji|publisher=Interworld|year=2004|medium=DVD|others=Re-release of 1993 VHS version}}</ref> as well as books by Serge Blanc, Famoudou Konaté, and Mamady Keïta.<ref name="Billmeier" /><ref name="Blanc">{{cite book|title=African Percussion: The Djembe|first=Serge|last=Blanc|year=1997|id=] M-7070-1802-6}}</ref><ref name="Konate" /> In 1998, these were supplemented by a three-volume VHS set by Keïta<ref name="Rythmes Traditionnels">{{cite video|title=Rythmes Traditionnels du Mandingue|medium=DVD|others=Re-release of 1998 VHS version|first=Mamady|last=Keïta|year=2008|publisher=Djembefola Productions}}</ref> and, in 2000, by a VHS tape by Epizo Bangoura.<ref>{{cite video|title=Yole & Zawuli: Traditional Rhythms for the Djembe|first=Epizo|last=Bangoura|medium=VHS|publisher=Dramavision|year=2000|editor-first=David|editor-last=Bolliger}}</ref> Since then, the market for educational materials has grown significantly. As of 2014, dozens of educational books, CDs, and videos are available to an aspiring player. | |||

| ===Tourism=== | ===Tourism=== | ||

| Starting in the 1980s, a number of Guinean djembefolas (Epizo Bangoura, Famoudou Konaté, Mamady Keïta) started hosting study tours to Guinea, allowing djembe students to |

Starting in the 1980s, a number of Guinean djembefolas (Epizo Bangoura, Famoudou Konaté, Mamady Keïta) started hosting study tours to Guinea, allowing djembe students to experience Guinean culture first-hand. Many other djembefolas followed suit; as of 2014, a potential visitor can select from tens of djembe tours each year. Djembe tourism created a market for djembefolas in Guinea that previously did not exist. Young djembefolas try to emulate the success of their predecessors and cater to the needs of the tourists, leading to change and commodification of the original djembe culture.<ref name="Flaig" /><ref name="Gaudette">{{cite journal |last=Gaudette |first=Pascal |title=Jembe Hero: West African Drummers, Global Mobility and Cosmopolitanism as Status |journal=Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies |volume=39 |issue=2 |pages=295–310 |doi=10.1080/1369183X.2013.723259 |date=20 September 2012 |s2cid=145753409 |df=mdy }}</ref> | ||

| ===Commercially produced instruments=== | ===Commercially produced instruments=== | ||

| Most djembes from Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Senegal are still hand carved from traditional species of wood, using traditional tools and methods. In the 1990s, djembes started being produced elsewhere, such as in ], ], ], and ], often using modern machinery and substitute species of wood, such as ] ('']'') or ] ('']''). However, these woods, being softer and less dense, are not as suitable as the |

Most djembes from Mali, Guinea, Burkina Faso, and Senegal are still hand carved from traditional species of wood, using traditional tools and methods. In the 1990s, djembes started being produced elsewhere, such as in ], ], ], and ], often using modern machinery and substitute species of wood, such as ] ('']'') or ] ('']'' or '']''). However, these woods, being softer and less dense, are not as suitable as the traditional woods.<ref name="Woods" /> A number of western percussion instrument manufacturers also produce djembe-like instruments, often with fibreglass bodies, synthetic skins, and a key tuning system.<ref name="Polak Bamako">{{cite journal|title=A Musical Instrument Travels Around the World: Jenbe Playing in Bamako, West Africa, and Beyond|first=Rainer|last=Polak|editor-last=Post|editor-first=Jennifer|journal=Ethnomusicology: A Contemporary Reader|year=2005}}</ref> | ||

| ===Drum circles=== | |||

| In the mid-1990s, the djembe began to supplant other instruments, such as the ] and ], as the most popular instrument in ]s, and entered the western mainstream.<ref name="Polak Bamako" /> | |||

| ===Women djembefolas=== | ===Women djembefolas=== | ||

| The traditional barriers against women djembe and dunun players have come down over time. | The traditional barriers against women djembe and dunun players have come down over time. | ||

| * In 1998, Mamoudou Conde, director of the ballets '']'', '']'', and ''Ballet Djoliba'', began to explore the idea of including women djembe and dunun players in ballet performances, against considerable initial resistance from male performers.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.amazoneswomandrummers.com/html/bio.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20040606104929/http://www.amazoneswomandrummers.com/html/bio.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=June 6, 2004|title=The creation of Amazones: The Women Master Drummers of Guinea|first=Mamoudou|last=Conde|date=December 17, 2003|publisher=Department of Culture of the Republic of Guinea|work=Amazones: The Women Master Drummers of Guinea}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://launch.groups.yahoo.com/group/raleighdrumcircle/message/1567 |first=Chuck |last=Cogliandro |title=Amazones Djembe Group—from Kumandi Drums Newsletter |date=August 5, 2004 |access-date=January 17, 2012 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120710224321/http://launch.groups.yahoo.com/group/raleighdrumcircle/message/1567 |archive-date=July 10, 2012 |url-status=dead |df=mdy }}</ref> Despite this, he included two female djembe players in the 2000 American tour of ''Les Percussions de Guinée''. Based on positive feedback from that tour, Conde decided to form an all-female ballet group called ''Amazones: The Women Master Drummers of Guinea'' (renamed ''Nimbaya!'' in 2010). The group first toured the US in 2004 and continues to perform, with tour dates scheduled out to 2014.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.amazoneswomandrummers.com/index.html |title=Official Website of NIMBAYA! The Women's Drum & Dance Company of Guinea |publisher=Department of Culture of the Republic of Guinea |access-date=January 17, 2012 |editor=Sekou Conde |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120130113443/http://www.amazoneswomandrummers.com/index.html |archive-date=January 30, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | |||

| * There are several notable female djembefolas, including Salimata Diabaté from Burkina Faso (lead djembefola of ''Afro Faso Jeunesse''),<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7YNp59JoAQ |title=Salimata Diabate et Afro Faso Jeunesse, SNC 2010 |website=] |access-date=January 17, 2012 |year=2010 |location=Performance at Le Theatre de l'Amitié, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120902130608/http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7YNp59JoAQ |archive-date=September 2, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> Monette Marino-Keita from San Diego (winner of the 1st National "Hand Drum-Off" Competition in 2001),<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.monettemarino.com/home/home.html |title=Monette Marino-Keita's Official Site |access-date=January 17, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120904003929/http://www.monettemarino.com/home/home.html |archive-date=September 4, 2012 |url-status=dead |df=mdy }}</ref> Anne-Yolaine Diarra from France (djembefola with ''Sokan''),<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.sokan.eu/ |title=SOKAN |language=fr |access-date=January 18, 2012 |year=2005 |work=Official website |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120131222552/http://sokan.eu/ |archive-date=January 31, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> and Melissa Hie from Burkina Faso (lead djembefola of ''Benkadi'').<ref>{{cite web |url=http://benkadibordeaux.free.fr |title=Benkadi un art authentique |access-date=May 24, 2013 |language=fr |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029190404/http://benkadibordeaux.free.fr/ |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://melissahie.wix.com/melissa |title=On the Road with Mélissa |access-date=May 24, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131029191632/http://melissahie.wix.com/melissa |archive-date=October 29, 2013 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | |||

| ==Sound and beating technique== | |||

| *In 1998, Mamoudou Conde, director of the ballets '']'', '']'', and ''Ballet Djoliba'', began to explore the idea of including women djembe and dunun players in ballet performances, against considerable initial resistance from male performers.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.amazoneswomandrummers.com/html/bio.html|archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20040606104929/|deadurl=yes|archivedate=6 June 2004|title=The creation of Amazones: The Women Master Drummers of Guinea|first=Mamoudou|last=Conde|date=17 December 2003|publisher=Department of Culture of the Republic of Guinea|work=Amazones: The Women Master Drummers of Guinea}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://launch.groups.yahoo.com/group/raleighdrumcircle/message/1567|first=Chuck|last=Cogliandro|title=Amazones Djembe Group—from Kumandi Drums Newsletter|date=5 August 2004|accessdate=17 January 2012|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/64pkJpYDc|archivedate=20 January 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> Despite this, he included two female djembe players in the 2000 American tour of ''Les Percussions de Guinée''. Based on positive feedback from that tour, Conde decided to form an all-female ballet group called ''Amazones: The Women Master Drummers of Guinea'' (renamed ''Nimbaya!'' in 2010). The group first toured the US in 2004 and continues to perform, with tour dates scheduled out to 2014.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.amazoneswomandrummers.com/index.html|title=Official Website of NIMBAYA! The Women's Drum & Dance Company of Guinea|publisher=Department of Culture of the Republic of Guinea|accessdate=17 January 2012|editor=Sekou Conde|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/64pkJpYDm|archivedate=20 January 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> | |||

| *Since 2010, Salimata Diabaté from Burkina Faso has performed as lead djembe player with her group ''Afro Faso Jeunesse'', proving that female djembefolas can match their male counterparts in every respect.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7YNp59JoAQ|title=Salimata Diabate et Afro Faso Jeunesse, SNC 2010|accessdate=17 January 2012|year=2010|location=Performance at Le Theatre de l'Amitié, Bobo Dioulasso, Burkina Faso|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/66hC2uezs|archivedate=5 April 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> | |||

| *In the West, Monette Marino-Keita from San Diego won the 1st National "Hand Drum-Off" Competition in 2001, performs internationally with the percussion ensemble ''Sewa Kan'', and produced her first percussion album ''Coup d'Eclat'' in 2010.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.monettemarino.com/home/home.html|title=Monette Marino-Keita's Official Site|accessdate=17 January 2012|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/66hCIlRov|archivedate=5 April 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> | |||

| *Anne-Yolaine Diarra is a French djembefola in the Strasbourg group ''Sokan'', where she plays with three male djembefolas from Burkina Faso.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.sokan.eu/|title=SOKAN|language=French|accessdate=18 January 2012|year=2005|work=Official website|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/66hCQfyPb|archivedate=5 April 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> | |||

| ==Sound and striking technique== | |||

| {{Listen|filename=Djembe accompaniment.ogg|title=Djembe sound sample|description=Djembe at medium pitch|filesize=227 KB|alt=Djembe at medium pitch}} | {{Listen|filename=Djembe accompaniment.ogg|title=Djembe sound sample|description=Djembe at medium pitch|filesize=227 KB|alt=Djembe at medium pitch}} | ||

| For its size, the djembe is an unusually loud drum. The volume of the drum rises with increasing skin tension. On a djembe tuned to solo pitch, skilled players can achieve ] of more than 105 dB, about the same volume as a jackhammer.<ref name="Prak" /> | For its size, the djembe is an unusually loud drum. The volume of the drum rises with increasing skin tension. On a djembe tuned to solo pitch, skilled players can achieve ] of more than 105 dB, about the same volume as a jackhammer.<ref name="Prak" /> | ||

| Djembe players use three basic sounds: ''bass'', ''tone'', and ''slap'', which have low, medium, and high pitch, respectively. These sounds are achieved by varying the striking technique and position. Other sounds are possible (masters achieve as many as twenty-five distinctly different sounds),<ref name="Konate">{{cite book|title=Rhythms and Songs from Guinea|first1=Famoudou|last1=Konaté|first2=Thomas|last2=Ott|isbn=3-89760-150- |

Djembe players use three basic sounds: ''bass'', ''tone'', and ''slap'', which have low, medium, and high pitch, respectively. These sounds are achieved by varying the striking technique and position. Other sounds are possible (masters achieve as many as twenty-five distinctly different sounds),<ref name="Konate">{{cite book|title=Rhythms and Songs from Guinea|first1=Famoudou|last1=Konaté|first2=Thomas|last2=Ott|isbn=978-3-89760-150-5|publisher=Lugert|location=Oldershausen, Germany|year=2000|postscript=. First published 1997 in German as ''Rhythmen und Lieder aus Guinea''}} {{ISBN|3-930915-68-5}}</ref> but these additional sounds are used rarely, mainly for special effects during a solo performance (''djembe kan'', literally, "the sound of the djembe"). A skilled player can use the sounds to create very complex rhythmic patterns; the combination of rhythm and the differently pitched sounds often leads an inexpert listener to believe that more than one drum is being played. | ||

| The bass sound is produced by striking the drum with the palm and flat fingers near the center of the skin. Tone and slap are produced by striking the drum closer to the edge; the contact area of the fingers determines whether the sound is a tone or a slap. For a tone, most of the area of the fingers and the edge of the palm contact the skin whereas, for a slap, the contact area is limited to the edge of the palm and the fingertips. The basic sounds are played "open", meaning that the hands rebound immediately after a strike, so the contact time with the skin is as short as possible. | The bass sound is produced by striking the drum with the palm and flat fingers near the center of the skin. Tone and slap are produced by striking the drum closer to the edge; the contact area of the fingers determines whether the sound is a tone or a slap. For a tone, most of the area of the fingers and the edge of the palm contact the skin whereas, for a slap, the contact area is limited to the edge of the palm and the fingertips. The basic sounds are played "open", meaning that the hands rebound immediately after a strike, so the contact time with the skin is as short as possible. | ||

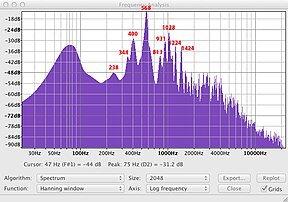

| Acoustically, a djembe is a ]: the frequency of the bass is determined by the size and shape of the shell and independent of the amount of tension on the skin. In contrast, the pitch of tones and slaps rises as the tension of the skin is increased. The bass has a frequency of 65–80 Hz. Depending on the size of the drum and the amount of tension on the skin, tone frequency varies from 300 Hz to 420 Hz and slap frequency from 700 Hz to 1000 Hz, with audible overtones reaching beyond 4 kHz.<ref name="Prak">{{cite web|url=http://djembelfaq.drums.org/v20a.htm|first=Albert|last=Prak|title=Physics of Djembe Sounds| |

Acoustically, a djembe is a ]: the frequency of the bass is determined by the size and shape of the shell and independent of the amount of tension on the skin. In contrast, the pitch of tones and slaps rises as the tension of the skin is increased. The bass has a frequency of 65–80 Hz. Depending on the size of the drum and the amount of tension on the skin, tone frequency varies from 300 Hz to 420 Hz and slap frequency from 700 Hz to 1000 Hz, with audible overtones reaching beyond 4 kHz.<ref name="Prak">{{cite web |url=http://djembelfaq.drums.org/v20a.htm |first=Albert |last=Prak |title=Physics of Djembe Sounds |date=July 1997 |publisher=DJEMBE-L |work=FAQ |access-date=January 12, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160305154530/http://djembelfaq.drums.org/v20a.htm |archive-date=March 5, 2016 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Mandiani Drum and Dance: Djimbe Performance and Black Aesthetics from Africa to the New World|first=Mark|last=Sunkett|publisher=White Cliffs Media|location=Tempe, AZ|year=1995|isbn=978-0-941677-76-9}}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/bass-djembe-t2824-15.html#p19168 |access-date=January 13, 2012 |title=Bass djembe |first=Michi |last=Henning |publisher=djembefola.com |work=Djembe Forum |date=March 23, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110525034826/http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/bass-djembe-t2824-15.html |archive-date=May 25, 2011 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|title=Science of Percussion Instruments|first=Thomas|last=Rossing|isbn=978-981-02-4158-2|publisher=World Scientific Publishing|edition=1st|date=January 15, 2000|location=Singapore}}</ref> | ||

| <gallery caption="Different vibrational modes of a djembe skin" heights="66" mode="packed"> | |||

| File:Drum_vibration_mode01.gif|alt=zero-one vibrational mode created by a bass or tone|(0,1) vibrational mode created by a bass or tone | |||

| {{Gallery | |||

| File:Drum vibration mode11.gif|alt=one-one vibrational mode created by a tonpalo|(1,1) vibrational mode created by a tonpalo | |||

| |title=Different vibrational modes of a djembe skin | |||

| File:Drum vibration mode21.gif|alt=two-one vibrational mode created by a slap|(2,1) vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |width=125 | |||

| File:Drum vibration mode02.gif|alt=zero-two vibrational mode created by a slap|(0,2) vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |width=125 | |||

| File:Drum vibration mode12.gif|alt=one-two vibrational mode created by a slap|(1,2) vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |align=center | |||

| File:Drum vibration mode03.gif|alt=zero-three vibrational mode created by a slap|(0,3) vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |lines=3 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| |File:Drum_vibration_mode01.gif|(0,1) vibrational mode created by a bass or tone|alt=zero-one vibrational mode created by a bass or tone | |||

| |File:Drum vibration mode11.gif|(1,1) vibrational mode created by a tonpalo|alt=one-one vibrational mode created by a tonpalo | |||

| |File:Drum vibration mode21.gif|(2,1) vibrational mode created by a slap|alt=two-one vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |File:Drum vibration mode02.gif|(0,2) vibrational mode created by a slap|alt=zero-two vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |File:Drum vibration mode12.gif|(1,2) vibrational mode created by a slap|alt=one-two vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| |File:Drum vibration mode03.gif|(0,3) vibrational mode created by a slap|alt=zero-three vibrational mode created by a slap | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Listen|filename=Djembe bass, tone, tonpalo, slap.ogg|title=Basic sounds of the djembe|description=Djembe bass, tone, tonpalo (third slap), and slap|filesize=64 KB|alt=Djembe bass, tone, tonpalo (third slap), and slap}} | {{Listen|filename=Djembe bass, tone, tonpalo, slap.ogg|title=Basic sounds of the djembe|description=Djembe bass, tone, tonpalo (third slap), and slap|filesize=64 KB|alt=Djembe bass, tone, tonpalo (third slap), and slap}} | ||

| The difference in pitch of the sounds arises because the different striking techniques selectively emphasize specific ] of the drum head.<ref name="CircularMembrane" /><ref name="VibModes">{{cite web|title=Vibrational Modes of a Circular Membrane|first=Daniel|last=Russell|year=2004–2011|publisher=Pennsylvania State University|work=Acoustics and Vibration Animations|url=http://www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/Demos/MembraneCircle/Circle.html| |

The difference in pitch of the sounds arises because the different striking techniques selectively emphasize specific ] of the drum head.<ref name="CircularMembrane" /><ref name="VibModes">{{cite web |title=Vibrational Modes of a Circular Membrane |first=Daniel |last=Russell |year=2004–2011 |publisher=Pennsylvania State University |work=Acoustics and Vibration Animations |url=http://www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/Demos/MembraneCircle/Circle.html |access-date=July 13, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120625040814/http://www.acs.psu.edu/drussell/Demos/MembraneCircle/Circle.html |archive-date=June 25, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> A tone emphasizes the (0,1) mode while suppressing the bass (Helmholtz resonance) and higher-order modes as much as possible. A slap emphasizes the (2,1), (0,2), (3,1), (1,2), and (0,3) modes (as well as higher-order modes) while suppressing the Helmholtz resonance and the (0,1) and (1,1) modes.<ref name="Prak" /> Skilled players can also produce a medium-pitched sound (between a tone and slap) that is variously called ''third slap'', ''tonpalo'', or ''lé''; this sound emphasizes the (1,1) mode while suppressing all other modes as much as possible.<ref name="Harmonics">{{cite web |title=Harmonics of tones and slaps |first=Michi |last=Henning |date=July 3, 2012 |publisher=djembefola.com |work=Djembe forum |access-date=July 13, 2012 |url=http://djembefola.com/board/technique/harmonics-tones-and-slaps-t3621-30.html#p27494 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20240524040432/http://www.webcitation.org/697MK5Qt9?url=http://djembefola.com/board/technique/harmonics-tones-and-slaps-t3621-30.html |archive-date=May 24, 2024 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | ||

| <gallery heights="135" mode="packed" caption="Spectrum analysis for bass, tonpalo, tone, and slap"> | |||

| {{Gallery | |||

| File:Djembe_bass_spectrum.jpg|alt=Spectrum analysis of a bass. The big hump at 75 Hertz is the Helmholtz resonance.|Spectrum analysis of a bass. The big hump is the Helmholtz resonance. | |||

| |title=Spectrum analysis for bass, tonpalo, tone, and slap | |||

| File:Djembe_tone_Spectrum.jpg|alt=Spectrum analysis of a tone. The pair of spikes at 343 Hz and 401 Hz are the zero-one mode.|Spectrum analysis of a tone. The pair of spikes at 343 Hz and 401 Hz are the (0,1) mode. | |||

| |align=center | |||

| File:Djembe_tonpalo_Spectrum.jpg|alt=Spectrum analysis of a tonpalo (third slap). The tallest spike at 568 Hertz is the one-one mode.|Spectrum analysis of a tonpalo (third slap). The tallest spike is the (1,1) mode. | |||

| |lines=3 | |||

| File:Djembe_slap_Spectrum.jpg|alt=Spectrum analysis of a slap. The spike at 812 Hz is the two-one mode, followed by higher-order modes.|Spectrum analysis of a slap. The spike at 812 Hz is the (2,1) mode, followed by higher-order modes. | |||

| |width=200 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| |File:Djembe_bass_spectrum.jpg|Spectrum analysis of a bass. The big hump is the Helmholtz resonance.|alt=Spectrum analysis of a bass. The big hump at 75 Hertz is the Helmholtz resonance. | |||

| |File:Djembe_tone_Spectrum.jpg|Spectrum analysis of a tone. The pair of spikes at 343 Hz and 401 Hz are the (0,1) mode.|alt=Spectrum analysis of a tone. The pair of spikes at 343 Hz and 401 Hz are the zero-one mode. | |||

| |File:Djembe_tonpalo_Spectrum.jpg|Spectrum analysis of a tonpalo (third slap). The tallest spike is the (1,1) mode.|alt=Spectrum analysis of a tonpalo (third slap). The tallest spike at 568 Hertz is the one-one mode. | |||

| |File:Djembe_slap_Spectrum.jpg|Spectrum analysis of a slap. The spike at 812 Hz is the (2,1) mode, followed by higher-order modes.|alt=Spectrum analysis of a slap. The spike at 812 Hz is the two-one mode, followed by higher-order modes. | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Listen|filename=Famoudou_Konaté_-_Sofa_excerpt.ogg|title=Famoudou Konaté: Sofa|description=Differently pitched slaps due to selective emphasis of different harmonics.<ref name="Rhythmen der Malinke" />|filesize=210 KB|alt=Differently pitched slaps due to selective emphasis of different harmonics}} | {{Listen|filename=Famoudou_Konaté_-_Sofa_excerpt.ogg|title=Famoudou Konaté: Sofa|description=Differently pitched slaps due to selective emphasis of different harmonics.<ref name="Rhythmen der Malinke" />|filesize=210 KB|alt=Differently pitched slaps due to selective emphasis of different harmonics}} | ||

| Line 137: | Line 119: | ||

| ==Role in the traditional ensemble== | ==Role in the traditional ensemble== | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Traditionally, the djembe forms an ensemble with a number of other djembes and one or more dunun. Except for the ''lead'' (or ''solo'') djembe, all instruments play a recurring rhythmic figure that is known as an ''accompaniment pattern'' or ''accompaniment part''. The figure repeats after a certain number of beats, known as a ''cycle''. The most common cycle length is four beats, but cycles often have other lengths, such as two, three, six, eight or more beats. (Some rhythms in the dundunba family from the ] region in Guinea have cycle lengths of 16, 24, 28, or 32 beats, among others.) Cycles longer than eight beats are rare for djembe accompaniments—longer cycles are normally played only by the '']'' or '']''. | Traditionally, the djembe forms an ensemble with a number of other djembes and one or more dunun. Except for the ''lead'' (or ''solo'') djembe, all instruments play a recurring rhythmic figure that is known as an ''accompaniment pattern'' or ''accompaniment part''. The figure repeats after a certain number of beats, known as a ''cycle''. The most common cycle length is four beats, but cycles often have other lengths, such as two, three, six, eight or more beats. (Some rhythms in the dundunba family from the ] region in Guinea have cycle lengths of 16, 24, 28, or 32 beats, among others.) Cycles longer than eight beats are rare for djembe accompaniments—longer cycles are normally played only by the '']'' or '']''. | ||

| Each instrument plays a different rhythmic figure, and the cycle lengths of the different instruments need not necessarily be the same. This interplay results in complex rhythmic patterns ('']s''). The different accompaniment parts are played on djembes that are tuned to different pitches; this emphasizes the polyrhythm and creates a composite overall |

Each instrument plays a different rhythmic figure, and the cycle lengths of the different instruments need not necessarily be the same. This interplay results in complex rhythmic patterns ('']s''). The different accompaniment parts are played on djembes that are tuned to different pitches; this emphasizes the polyrhythm and creates a composite overall melody. | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| The number of instruments in the ensemble varies with the region and occasion. In Mali, a traditional ensemble often consists of one dunun (called ]) and one djembe. The konkoni and djembe are in a rhythmic dialog, with each drum taking turns playing accompaniment while the other instrument plays improvised solos.<ref name="Realbook">{{cite book|title=The Jenbe Realbook|first=Rainer|last=Polak|publisher=bibiafrica|location=Nürnberg, Germany|year=2006}}</ref> | The number of instruments in the ensemble varies with the region and occasion. In Mali, a traditional ensemble often consists of one dunun (called '']'') and one djembe. The konkoni and djembe are in a rhythmic dialog, with each drum taking turns playing accompaniment while the other instrument plays improvised solos. If a second dunun player is available, he supplements the ensemble with a ''khassonka dunun'', which is a bass drum similar in build to a konkoni, but larger.<ref name="Realbook">{{cite book|title=The Jenbe Realbook|first=Rainer|last=Polak|publisher=bibiafrica|location=Nürnberg, Germany|year=2006}}</ref> | ||

| In Guinea, a typical ensemble uses three djembes and three dunun. If an ensemble includes more than one djembe, the highest pitched (and therefore loudest) djembe plays solo phrases and the other djembes and dunun play accompaniment. | In Guinea, a typical ensemble uses three djembes and three dunun, called ''sangban'' (medium pitch), ''dundunba'' (bass pitch), and ''kenkeni'' (high pitch, also called ''kensedeni''). If an ensemble includes more than one djembe, the highest pitched (and therefore loudest) djembe plays solo phrases and the other djembes and dunun play accompaniment. | ||

| An ensemble may have only two dunun, depending on whether a village has enough dunun players and is wealthy enough to afford three dunun. | An ensemble may have only two dunun, depending on whether a village has enough dunun players and is wealthy enough to afford three dunun. | ||

| A djembe and dunun ensemble traditionally does not play music for people to simply sit back and listen to. Instead, the ensemble creates rhythm for people to dance, sing, clap, or work to. The western distinction between musicians and audience is inappropriate in a traditional context. A rhythm is rarely played as a performance, but is participatory: musicians, dancers, singers, and onlookers are all part of the ensemble and frequently change roles while the music is in progress.<ref name="Chernoff">{{cite book|title=African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms|first=John|last=Chernoff|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-10345-7|date= |

A djembe and dunun ensemble traditionally does not play music for people to simply sit back and listen to. Instead, the ensemble creates rhythm for people to dance, sing, clap, or work to. The western distinction between musicians and audience is inappropriate in a traditional context. A rhythm is rarely played as a performance, but is participatory: musicians, dancers, singers, and onlookers are all part of the ensemble and frequently change roles while the music is in progress.<ref name="Chernoff">{{cite book|title=African Rhythm and African Sensibility: Aesthetics and Social Action in African Musical Idioms|first=John|last=Chernoff|publisher=University of Chicago Press|isbn=978-0-226-10345-7|date=October 15, 1981|url-access=registration|url=https://archive.org/details/africanrhythmafr00cher_0}}</ref> | ||

| Musicians and participants often form a circle, with the centre of the circle reserved for dancers. Depending on the particular rhythm being played, dances |

Musicians and participants often form a circle, with the centre of the circle reserved for dancers. Depending on the particular rhythm being played, dances may be performed by groups of men and/or women with choreographed steps, or single dancers may take turns at performing short solos. The lead djembe's role is to play solo phrases that accentuate the movements of the dancers. Often, the aim is to "mark the dancers' feet", that is, to play rhythmic patterns that are synchronized with the dancers' steps. Individual solo dances are not choreographed, with the dancer freely moving in whatever way feels appropriate at that moment. Marking a solo dancer's feet requires the lead djembefola to have strong rapport with the dancer, and it takes many years of experience for a djembefola to acquire the necessary rhythmic repertoire. | ||

| The lead djembefola also improvises to a rhythm at times when no-one is dancing. While there is considerable freedom in such improvisation, the solo phrases are not random. Instead, individual rhythms have specific key patterns (signature phrases) that the soloist is expected to know and integrate into his improvisation. A skilled soloist will also play phrases that harmonize with the background rhythm ('']'') that is created by the other instruments. | The lead djembefola also improvises to a rhythm at times when no-one is dancing. While there is considerable freedom in such improvisation, the solo phrases are not random. Instead, individual rhythms have specific key patterns (signature phrases) that the soloist is expected to know and integrate into his improvisation. A skilled soloist will also play phrases that harmonize with the background rhythm ('']'') that is created by the other instruments. | ||

| ==Construction== | ==Construction== | ||

| ===Materials=== | |||

| ====Shell==== | |||

| Traditionally crafted djembes are carved from a single log of hardwood. A number of different wood species are used, all of which are hard and dense. Hardness and density are important factors for the sound and projection of the djembe. The most prized djembe wood is ''lenke'' ('']''), not because it necessarily sounds better than other woods, but because the Malinké believe that its spiritual qualities are superior. (Malinké traditional wisdom states that a spiritual energy, or '']'', runs through all things, living or dead.<ref name= | |||

| "MM">{{cite book|title=Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa|first=Eric|last=Charry|publisher=University of Chicago Press|year=2000|isbn=0-226-10161-4}}</ref>) Besides lenke, traditional woods include ''djalla'' ('']''), ''dugura'' ('']''), ''gueni'' ('']''), ''gele'' ('']''), and '']'' ('']'').<ref name="Woods">{{cite web|first=Michi|last=Henning|title=Djembe Woods: What You Need to Know|url=http://djembefola.com/articles/djembe-woods.php|accessdate=19 January 2012|publisher=djembefola.com|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/64pkJpYDL|archivedate=20 January 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> | |||

| === Shell === | |||

| ] | |||

| Traditionally crafted djembes are carved from a single log of hardwood. A number of different wood species are used, all of which are hard and dense. Hardness and density are important factors for the sound and projection of the djembe. The most prized djembe wood is ''lenke'' ('']''), not because it necessarily sounds better than other woods, but because the Malinké believe that its spiritual qualities are superior. (Malinké traditional wisdom states that a spiritual energy, or '']'', runs through all things, living or dead.<ref name= | |||

| "MM">{{cite book|title=Mande Music: Traditional and Modern Music of the Maninka and Mandinka of Western Africa|first=Eric|last=Charry|publisher=University of Chicago Press|year=2000|isbn=978-0-226-10161-3}}</ref>) Besides lenke, traditional woods include ''djalla'' ('']''), ''dugura'' ('']''), ''gueni'' ('']''), ''gele'' ('']''), and '']'' ('']'').<ref name="Woods">{{cite web |first=Michi |last=Henning |title=Djembe Woods: What You Need to Know |url=http://djembefola.com/learn/articles/djembe-woods |access-date=January 19, 2012 |publisher=djembefola.com |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120103141203/http://djembefola.com/articles/djembe-woods.php |archive-date=January 3, 2012 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Shells are carved soon after the tree is felled, while the wood still retains some moisture and is softer. This makes the wood easier to carve and avoids radial splits that tend to develop in logs that are allowed to dry naturally.<ref>{{cite encyclopaedia|title=]|encyclopedia=Misplaced Pages|url=http://en.wikipedia.org/Wood_drying|accessdate=20 January 2012|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/6AjLcRf4u|archivedate=16 September 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> Carvers use simple hand tools, such as ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s to shape the shell.<ref name="Sunkett DVD">{{cite video|title=Mandiani Drum and Dance: Djimbe Performance & Black Aesthetics from Africa to the New World|publisher=White Cliffs Media|location=Tempe, AZ|first=Mark|last=Sunkett|medium=DVD|year=1995|others=Companion DVD to the book}}</ref><ref>{{cite video|title=Djembé Spielen Lernen: Herstellung, Geschichte, Tradition|first=Ursula|last=Branscheid-Diabaté|year=2010|location=Neusäß, Germany|publisher=Leu-Verlag|language=German|medium=DVD}}</ref> A well-carved djembe does not have a smooth interior but a texture of scallops or shallow grooves that influence the sound of the instrument. (Djembes with smooth interiors have too much sustain for tones and slaps and sound "ringy".) Often, interior grooves form a spiral pattern, which indicates a carver taking pride in his work. | |||

| Shells are carved soon after the tree is felled while the wood still retains some moisture and is softer. This makes the wood easier to carve and avoids radial splits that tend to develop in logs that are allowed to dry naturally.<ref name="Drying">{{cite book|title=Kiln-Drying of Lumber|first1=Roger B.|last1=Keey|first2=Timothy A. G.|last2=Langrish|first3=John C. F.|last3=Walker|year=2000|publisher=Springer|location=Berlin|isbn=978-3-642-59653-7}}</ref> Carvers use simple hand tools, such as ]s, ]s, ]s, and ]s to shape the shell.<ref name="Sunkett DVD">{{cite video|title=Mandiani Drum and Dance: Djimbe Performance & Black Aesthetics from Africa to the New World|publisher=White Cliffs Media|location=Tempe, AZ|first=Mark|last=Sunkett|medium=DVD|year=1995|others=Companion DVD to the book}}</ref><ref>{{cite video|title=Djembé Spielen Lernen: Herstellung, Geschichte, Tradition|first=Ursula|last=Branscheid-Diabaté|year=2010|location=Neusäß, Germany|publisher=Leu-Verlag|language=de|medium=DVD}}</ref> A well-carved djembe does not have a smooth interior but a texture of scallops or shallow grooves that influence the sound of the instrument. (Djembes with smooth interiors have tones and slaps with too much sustain.) Often, interior grooves form a spiral pattern, which indicates a carver taking pride in his work. | |||

| ====Skin==== | |||

| The djembe is headed with a rawhide skin, most commonly goatskin. Other skins, such as antelope, cow, kangaroo, or horse can be used as well. Thicker skins, such as cow, have a warmer sound with more overtones in the slaps; thinner skins have a sharper sound with fewer overtones in the slaps and are louder. Thick skins make it easier to play full tones but more difficult to play sharp slaps; for thin skins, the opposite applies. Thin skins are louder than thick ones. Thick skins, such as cow, are particularly hard on the hands of the player and cause more callousing than goat skins. | |||

| === Skin === | |||

| Skins from dry and hot-climate areas and poorly fed goats are preferred for djembes because of their low fat content. Skins from cold-climate goats with high-value nutrition have more than double the fat content; they tend to sound dull and lifeless in comparison. Even though the fat content of male goats is lower than that of female goats,<ref>{{cite thesis|title=Biological Factors Influencing the Nature of Goat Skins and Leather|thesis=Ph.D.|first=Philippa|last=Stosic|month=May|year=1994|publisher=University of Leicester|location=UK|url=http://www.nda.agric.za/docs/AAPS/Articles/Goats/Production/R4273.pdf|accessdate=20 January 2012|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/64pkJpYEC|archivedate=20 January 2012|deadurl=no}}</ref> many players prefer female skins because they do not smell as strongly and are reputed to be softer. | |||

| The djembe is headed with a rawhide skin, most commonly goatskin. Other skins, such as antelope, cow, kangaroo, or horse can be used as well. Thicker skins, such as cow, have a warmer sound with more overtones in the slaps; thinner skins have a sharper sound with fewer overtones in the slaps and are louder. Thick skins make it easier to play full tones but more difficult to play sharp slaps; for thin skins, the opposite applies. Thin skins are louder than thick ones. Thick skins, such as cow, are particularly hard on the hands of the player and cause more callousing than goatskins. | |||

| Skins from dry and hot-climate areas and poorly fed goats are preferred for djembes because of their low fat content. Skins from cold-climate goats with high-value nutrition have more than double the fat content; they tend to sound dull and lifeless in comparison. Even though the fat content of male goats is lower than that of female goats,<ref>{{cite thesis |title=Biological Factors Influencing the Nature of Goat Skins and Leather |degree=Ph.D. |first=Philippa |last=Stosic |date=May 1994 |publisher=University of Leicester |location=UK |url=http://www.nda.agric.za/docs/AAPS/Articles/Goats/Production/R4273.pdf |access-date=January 20, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190708091436/http://www.smallstock.info/research/reports/R5186/R5186-PhdThesis.pdf |archive-date=July 8, 2019 |url-status=live |df=mdy }}</ref> many players prefer female skins because they do not smell as strongly and are reputed to be softer. | |||

| The skin is mounted with the spine running through the centre of the drum head, with the line of the spine pointing at the player, so the hands strike either side of the spine. Animal skins are thicker at the spine than the sides; mounting the skin with the spine centered ensures that the left and right hand play symmetric areas of equal size and thickness. In turn, this helps to minimize differences in pitch of the notes played by the left and right hand. Normally, the head end of the spine points at the player, so the hands strike the area of the skin that used to be the shoulders of the goat. With thicker skins, such as from a cow or horse, the skin round is usually taken from the side of the hide so it does not include the spine, which is too thick for use on a djembe. | The skin is mounted with the spine running through the centre of the drum head, with the line of the spine pointing at the player, so the hands strike either side of the spine. Animal skins are thicker at the spine than the sides; mounting the skin with the spine centered ensures that the left and right hand play symmetric areas of equal size and thickness. In turn, this helps to minimize differences in pitch of the notes played by the left and right hand. Normally, the head end of the spine points at the player, so the hands strike the area of the skin that used to be the shoulders of the goat. With thicker skins, such as from a cow or horse, the skin round is usually taken from the side of the hide so it does not include the spine, which is too thick for use on a djembe. | ||

| Skins may be shaved prior to mounting or afterwards, or may be de-haired by ]. Liming weakens skins; some djembefolas also claim that limed skins are harder on their hands and do not sound as good as untreated skins.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/damn-seriously-t3500.html#p23988|title=Damn it.....seriously!!|first=Tom|last=Kondas| |

Skins may be shaved prior to mounting or afterwards, or may be de-haired by ]. Liming weakens skins; some djembefolas also claim that limed skins are harder on their hands and do not sound as good as untreated skins.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/damn-seriously-t3500.html#p23988 |title=Damn it.....seriously!! |first=Tom |last=Kondas |access-date=January 20, 2012 |archive-date=January 4, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120104010549/http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/damn-seriously-t3500.html |url-status=live |publisher=djembefola.com |work=Djembe Forum |date=December 9, 2011 |df=mdy }}</ref> | ||

| Factory-made djembes often use skins made from synthetic materials, such as ]. |

Factory-made djembes often use skins made from synthetic materials, such as ]. | ||

| === |

=== Rope === | ||

| Modern djembes exclusively use synthetic rope, most commonly of ] construction, 4–5 mm in diameter. Low-stretch (static) rope is preferred. Most djembe ropes have a ] core with a 16‑ or 32‑plait mantle and around 5% stretch. Very low-stretch (<1%) rope materials, such as ] and ], are used only rarely due to their much higher cost. | Modern djembes exclusively use synthetic rope, most commonly of ] construction, 4–5 mm in diameter. Low-stretch (static) rope is preferred. Most djembe ropes have a ] core with a 16‑ or 32‑plait mantle and around 5% stretch. Very low-stretch (<1%) rope materials, such as ] and ], are used only rarely due to their much higher cost. | ||

| ===Mounting system=== | |||

| ===Mounting system=== | |||

| The mounting system for the skin has undergone a number of changes over time. | The mounting system for the skin has undergone a number of changes over time. | ||

| ====Traditional mounting==== | ====Traditional mounting==== | ||

| ] from the ] region in ]. (From the collection of ], Paris, added to the collection in 1938.)]] | |||

| Originally, the skin was attached by wooden pegs that were driven through holes in the skin and the shell near the playing edge. Four to five people would stretch the wet skin over the drum to apply tension while the pegs were driven into the bowl. The shrinkage of the skin while it dried then applied sufficient additional tension for the skin to resonate.<ref name="Dublin">{{cite video |people=Mamady Keïta |title=Djembe talk and performance with Mamady Keïta at the Big Bang festival in Dublin, Ireland |volume=Part 1 |format=flv |url=http://djembefola.com/mamady-keita-interview.php |access-date=January 21, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120103151853/http://djembefola.com/mamady-keita-interview.php |archive-date=January 3, 2012 |url-status=dead |publisher=djembefola.com |year=2009 |time=14:05 |df=mdy-all }}</ref> A similar mounting technique is still used by the Landouma (a subgroup of the ]) for a djembe-like drum known as a ''gumbe''.<ref name="Koumbassa">{{cite video|title=Landouma Fare: From the Heartland|medium=DVD|people=Youssouf Koumbassa (himself), Julian McNamara, Kate Farrell (directors)|publisher=B-rave Studio|year=2010}}</ref> This mounting technique most likely goes back hundreds of years; the exact period is unknown. | |||

| ] from the ] region in ]. (From the collection of ], Paris, added to the collection in 1938.)|Traditional djembe used by the Kono people from the Nzérékoré region in Forest Guinea. (From the collection of Musée de l'Homme, Paris, added to the collection in 1938.)]] | |||

| Up until the 1980s, the most common mounting system used twisted strips of cowhide as rope. The skin was attached with rings made of cowhide; one ring was sewn into the perimeter of the skin and a second ring placed below it, with loops holding the skin in place and securing the two rings together. A long strip of cowhide was used to lace up the drum, applying tension between the top ring and a third ring placed around the stem. To apply further tension, the vertical sections of the rope were woven into a diamond pattern that shortens the verticals. Wooden pegs wedged between the shell and the lacing could be used to increase tension still further.<ref name="Dublin" /> | |||

| Originally, the skin was attached by wooden pegs that were driven through holes in the skin and the shell near the playing edge. Four to five people would stretch the wet skin over the drum to apply tension while the pegs were driven into the bowl. The shrinkage of the skin while it dried then applied sufficient additional tension for the skin to resonate.<ref name="Dublin">{{cite video|people=]|title=Djembe talk and performance with Mamady Keïta at the Big Bang festival in Dublin, Ireland|volume=Part 1|format=flv|url=http://djembefola.com/mamady-keita-interview.php|archiveurl=http://www.webcitation.org/64rzOUs5T|archivedate=21 January 2012|deadurl=no|publisher=djembefola.com|year=2009|time=14:05}}</ref> A similar mounting technique is still used by the Landouma (a subgroup of the ]) for a djembe-like drum known as a ''gumbo''.<ref name="Koumbassa">{{cite video|title=Landouma Fare: From the Heartland|medium=DVD|people=Youssouf Koumbassa (himself), Julian McNamara, Kate Farrell (directors)|publisher=B-rave Studio|year=2010}}</ref> This mounting technique most likely goes back hundreds of years; the exact period is unknown. | |||

| Up until the 1980s, the most common mounting system used twisted strips of cowhide as rope. The skin was attached with rings made of cowhide; one ring was sown into the perimeter of the skin and a second ring placed below it, with loops holding the skin in place and securing the two rings together. A long strip of cowhide was used to lace up the drum, applying tension between the top ring and a third ring placed around the stem. To apply further tension, the vertical sections of the rope were woven into a diamond pattern that shortens the verticals. Wooden pegs wedged between the shell and the lacing could be used to increase tension still further.<ref name="Dublin" /> | |||

| The pitch of these traditional djembes was much lower than it is today because the natural materials imposed a limit on the amount of tension that could be applied. Prior to playing, djembefolas heated the skin near the flames of an open fire, which drives moisture out of the skin and causes it to shrink and increase the pitch of the drum. This process had to be repeated frequently, every 15–30 minutes.<ref name="Polak Bamako" /> | The pitch of these traditional djembes was much lower than it is today because the natural materials imposed a limit on the amount of tension that could be applied. Prior to playing, djembefolas heated the skin near the flames of an open fire, which drives moisture out of the skin and causes it to shrink and increase the pitch of the drum. This process had to be repeated frequently, every 15–30 minutes.<ref name="Polak Bamako" /> | ||

| ====Modern mounting==== | ====Modern mounting==== | ||

| ] | |||

| The modern mounting system arose in the early seventies, when touring ballets came into contact with synthetic rope used by the military. Initially, the synthetic rope was used to replace the twisted cowhide strips. However, the rope could now be tightened to the point where it tore through the skin; in response, drum makers started using steel rings instead of twisted cowhide to hold the skin in place.<ref name="Dublin" /> Despite objections from many djembefolas, the modern mounting system gradually displaced the traditional one and, by 1991 had completely replaced it.<ref name="Polak Bamako" /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The skin is held in place by being trapped between the top ring, called the ''crown ring'', and the ring below it, called the ''flesh ring''. A third ring (the ''bottom ring'') is placed around the stem. The rings are commonly made from 6–8 mm (¼–⅓ in) ]. A series of ]es on the crown ring and bottom ring form loops. Through these loops, a length of rope connects the crown ring and the bottom ring; tightening this rope applies tension. As the vertical rope is tensioned, the cow hitches on the crown ring press the skin against the flesh ring below; this attaches the skin to the flesh ring very securely and stretches the skin over the bearing edge of the drum. | |||

| The modern mounting system arose in the early seventies, when touring ballets came into contact with synthetic rope used by the military. Initially, the synthetic rope was used to replace the twisted cowhide strips. However, the rope could now be tightened to the point where it tore through the skin; in response, drum makers started using steel rings instead of rope loops to hold the skin in place.<ref name="Dublin" /> Despite objections from many djembefolas, the modern mounting system gradually displaced the traditional one and, by 1991 had completely replaced it.<ref name="Polak Bamako" /> | |||

| <gallery caption="Mounting systems" heights="150" mode="packed"> | |||

| File:Djembe skin mounting system.jpg|alt=Schematic of two-ring skin mounting|Schematic of two-ring skin mounting | |||

| File:Djembe skin mounting system - three rings.jpg|alt=Schematic of three-ring skin mounting|Schematic of three-ring skin mounting | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ] | |||

| The skin is held in place by being trapped between the top ring, called the ''crown ring'', and the ring below it, called the ''flesh ring''. A third ring (the ''bottom ring'') is placed around the stem. The rings are commonly made from 6–8 mm (¼–⅓ in) ]. A series of ]es on the crown ring and bottom ring form loops. Through these loops, a length of rope connects the crown ring and the bottom ring; tightening this rope applies tension. As the vertical rope is tensioned, the cow hitches on the crown ring press the skin against the flesh ring below; this attaches the skin to the flesh ring very securely and stretches the skin over the bearing edge of the drum. | |||

| A variation of this technique, introduced in the early 2000s, uses three rings instead of two. The idea of this technique is to increase the number of friction points trapping the skin to make it less likely for the skin to slip between the rings as tension is applied. There is no firm consensus in the djembe community as to whether the benefits of this mounting are worth the extra weight and added complexity.<ref name="doc">{{cite book|title=Djembe Construction: A Comprehensive Guide|first=Michi|last=Henning|date=May 2012|isbn=978-0-9872791-0-1}}</ref><ref name="three ring">{{cite web |url=http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/three-top-rings-yea-nay-t855.html |date=March 18, 2009 |access-date=May 5, 2012 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120110171140/http://djembefola.com/board/technical-advice/three-top-rings-yea-nay-t855.html |archive-date=January 10, 2012 |url-status=live |publisher=djembefola.com |work=Djembe Forum |title=Three top rings? Yea or nay |df=mdy }}</ref> | |||

| {{gallery | |||

| |title=mounting systems | |||

| |File:Djembe skin mounting system.jpg|Schematic of two-ring skin mounting|alt=Schematic of two-ring skin mounting | |||

| |File:Djembe skin mounting system - three rings.jpg|Schematic of three-ring skin mounting|alt=Schematic of two-ring skin mounting | |||

| }} | |||

| ] | |||