| Revision as of 18:57, 15 November 2012 editMogism (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users, Pending changes reviewers185,177 editsm →Diary: Typo fixing and cleanup, typos fixed: alledgedly → allegedly using AWB (8564)← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 17:13, 22 December 2024 edit undo50.172.17.27 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| (861 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|American Arctic explorer (1856–1920)}} | |||

| {{for|] ships named after Robert Peary|USS Robert E. Peary}} | |||

| {{for|United States Navy ships named after Robert Peary|USS Robert E. Peary}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=August 2012}} | {{Use mdy dates|date=August 2012}} | ||

| {{more footnotes|date=April 2011}} | |||

| {{Infobox person | {{Infobox person | ||

| |name |

| name = Robert Peary | ||

| |image = |

| image = Robert Peary self-portrait, 1909.jpg | ||

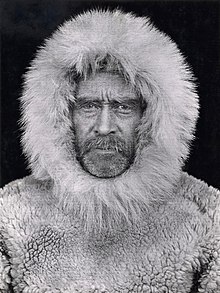

| | caption = At ] on ], 1909 | |||

| |image_size = 160px | |||

| | |

| birth_name = Robert Edwin Peary | ||

| | birth_date = {{birth date|1856|05|06}} | |||

| |birth_name = | |||

| | birth_place = ], ], ] | |||

| |birth_date = {{birth date|1856|5|6}} | |||

| | death_date = {{death date and age|1920|02|20|1856|05|06}} | |||

| |birth_place = ] | |||

| | death_place = ], ] | |||

| |death_date = {{death date and age|1920|2|20|1856|5|6}} | |||

| | |

| resting_place = ] | ||

| | alma_mater = ] | |||

| |death_cause = | |||

| | known_for = Claim to have reached the ] on his travels with Matthew Henson. | |||

| |resting_place = | |||

| | spouse = {{marriage|]|August 11, 1888}} | |||

| |resting_place_coordinates = | |||

| | |

| children = 4 | ||

| | awards = {{ubl|]|]|]}} | |||

| |nationality = ] | |||

| | module = {{infobox military person|embed=yes | |||

| |other_names = | |||

| | |

|allegiance = ] | ||

| | |

|branch_label = Branch | ||

| |branch = {{naval|US|1864}} | |||

| |employer = | |||

| |serviceyears_label = Service years | |||

| |occupation = | |||

| | |

|serviceyears = 1881–1911 | ||

| |rank = ] | |||

| |title = | |||

| | |

|unit = ] | ||

| }} | |||

| |networth = | |||

| |height = | |||

| |weight = | |||

| |term = | |||

| |predecessor = | |||

| |successor = | |||

| |party = | |||

| |boards = | |||

| |religion = | |||

| |spouse = ] | |||

| |partner = | |||

| |children = Marie Ahnighito Peary<br />Robert Edwin Peary, Jr. | |||

| |parents = | |||

| |relatives = | |||

| |signature = | |||

| |website = | |||

| |footnotes = | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Robert Edwin Peary, Sr.''' (May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an ] explorer who claimed to have led the first expedition, on April 6, 1909, to reach the ]. Peary's claim was widely credited for most of the 20th century, though it was criticized even in its own day. | |||

| '''Robert Edwin Peary Sr.''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|p|ɪər|i}}; May 6, 1856 – February 20, 1920) was an American explorer and officer in the ] who made several expeditions to the ] in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was long credited as being the discoverer of the geographic ] in April 1909, having led the first expedition to have claimed this achievement, although it is now considered unlikely that he actually reached the Pole. | |||

| ==Life and career== | |||

| Peary was born in ], but, following his father's death at a young age, was raised in ]. He attended ], then joined the ] as a draftsman. He enlisted in the navy in 1881 as a civil engineer. In 1885, he was made chief of surveying for the ], which was never built. He visited the ] for the first time in 1886, making an unsuccessful attempt to cross ] by ]. In the ], he was much better prepared, and by reaching ] in what is now known as ], he proved conclusively that Greenland was an island. He was one of the first Arctic explorers to study ] survival techniques.{{efn|Many Inuit consider the term "]" to be unacceptable and even pejorative, although it continues to be used within historical, linguistic, archaeological, and cultural contexts.}} During an expedition in 1894, he was the first Western explorer to reach the ] and its fragments, which were then taken from the native Inuit population who had relied on it for creating tools. During that expedition, Peary deceived six indigenous individuals, including ], into traveling to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year. This promise was unfulfilled and four of the six Inuit died of illnesses within a few months.<ref name=Northern/> | |||

| ===Early years=== | |||

| Robert Edwin Peary was born in ], in 1856. He graduated from ], ],<ref>, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed Oct 4, 2009</ref> in 1877.<ref name="bowdoin">{{cite web|url=http://www.bowdoin.edu/news/archives/1bowdoincampus/005262.shtml|title=What They Packed|publisher=bowdoin.edu|accessdate=November 28, 2008}}</ref> He was also a member of the Theta chapter of ] while at Bowdoin, and the flag of DKE was one of the five flags that he took with him to the North Pole. His home in ], still remains in pristine condition as an inn known as the Admiral Peary House. | |||

| On his 1898–1902 expedition, Peary set a new "]" record by reaching Greenland's northernmost point, ]. Peary made two more expeditions to the Arctic, in 1905–1906 and in 1908–1909. During the latter, he claimed to have reached the North Pole. Peary received several ] awards during his lifetime, and, in 1911, received the ] and was promoted to ]. He served two terms as president of ] before retiring in 1911. | |||

| ===Initial Arctic expeditions=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Peary made several expeditions to the ], exploring ] by ] in 1886 and 1891 and returning to the island three times in the 1890s, including the ]. He twice attempted to cross northwest Greenland over the ice cap, discovering Navy Cliff. American artist ] joined some of these expeditions. | |||

| Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole was widely debated along with a competing claim made by ], but eventually won widespread acceptance. In 1989, British explorer ] concluded Peary did not reach the pole, although he may have come within {{convert|60|mi|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Noose/> | |||

| Unlike most previous explorers, Peary studied ] survival techniques, built ]s, and dressed in practical furs in the native fashion both for heat preservation and to dispense with the extra weight of tents and sleeping bags when on the march. Peary also relied on the Inuit as hunters and dog-drivers on his expeditions, and pioneered the use of the system (which he called the "Peary system") of using support teams and supply caches for Arctic travel. His wife, Josephine, accompanied him on several of his expeditions. During the course of his explorations, he had eight toes amputated. | |||

| ==Early life, education, and career== | |||

| ===Peary's fame=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Peary's 1898–1902 expedition was darkened by his claim to an 1899 visual discovery of "]" west of Ellesmere, leading to his allegation that this was his sighting of Axel Heiberg land prior to its discovery by Norwegian explorer ]'s expedition, a Peary claim now universally rejected. However, the ] and ] honored Peary for tenacity, mapping of previously uncharted areas and his discovery in 1900 of ] at the north tip of Greenland. Peary also achieved a farthest north for the western hemisphere in 1902 north of Canada's ]. | |||

| Robert Edwin Peary was born on May 6, 1856, in ], to Charles N. and Mary P. Peary. After his father died in 1859, Peary and his mother moved to ].<ref name=NavalHistory>{{cite web | url=https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/seabee/explore/civil-engineer-corps-history/robert-e--peary.html | title=Rear Admiral Robert E. Peary, US Navy 1856–1920 | publisher=] |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121107040240/http://www.history.navy.mil/bios/peary_roberte.htm | archive-date=November 7, 2012 | url-status=live}}</ref> Peary attended ] where he graduated in 1873. Peary made his way to ], some {{convert|36|mi|abbr=on}} to the north, where he was a member of the ] fraternity and the ] ].<ref name=bowdoin>{{cite web | url=https://www.bowdoin.edu/arctic-museum/educational-resources/arctic-biographies/peary.html | title=Robert E. Peary | publisher=]}}</ref> He was also part of the rowing team.<ref name=bowdoin/> He graduated in 1877 with a ] degree.<ref name=bowdoin/><ref name=Mills510>Mills 2003, p. 510.</ref> | |||

| From 1878 to 1879, Peary lived in ], ]. During that time, he made a profile survey from the top of Fryeburg's Jockey Cap Rock. The 360-degree survey names the larger hills and mountains visible from the summit. After Peary's death, his boyhood friend, Alfred E. Burton, suggested that the profile survey be made into a monument. It was cast in bronze and set atop a granite cylinder and erected to his memory by the Peary family in 1938.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.mainetrailfinder.com/trails/trail/jockey-cap | title=Jockey Cap – Maine Trail Finder | publisher=Maine Trail Finder}}</ref> | |||

| ===The 1905–1906 expedition=== | |||

| ]'' in the ] in 1909]] | |||

| Peary's next expedition was supported by a $50,000 gift by George Crocker,<ref>{{cite journal|title=Peary Gets $50,000; M.K. Jesup Gives $25,000|journal=New York Times|date=July 13, 1905|page=p. 7}}</ref> who was the youngest son of ]. Peary then used the money for a new ship. Peary's new ship ''Roosevelt'' battled its way through the ice between Greenland and Ellesmere Island to an American hemisphere farthest north by ship. The 1906 "Peary System" dogsled drive for the pole across the rough sea ice of the Arctic Ocean started from the north tip of Ellesmere at 83° north latitude. The parties made well under {{convert|10|mi|km}} a day until they became separated by a storm, so Peary was inadvertently without a companion sufficiently trained in navigation to verify his account from that point northward. With insufficient food, and with the negotiability of the ice between himself and land an uncertain factor, he made the best dash he could and barely escaped with his life off the melting ice. On April 20, he was no further north than 86°30' latitude<ref>For obvious reasons, this latitude was never published by Peary. It is in a typescript of his April, 1906 diary, discovered by Sir Wally Herbert (Herbert, 1989). The typescript suddenly stops there, one day before the April 21 purported Farthest, and the original of the April 1906 record is the only missing diary of Peary's exploration career (Rawlins, ).</ref> yet he claimed to have the next day achieved a ] world record at 87°06' and returned to 86°30' without camping, an implied trip of at least {{convert|72|nmi|km}} between sleeping, even assuming undetoured travel. | |||

| After college, Peary worked as a draftsman making technical drawings at the ] office in Washington, D.C. He joined the ] and on October 26, 1881, was commissioned in the ], with the relative rank of lieutenant.<ref name=NavalHistory/> From 1884 to 1885, he was an assistant engineer on the surveys for the ] and later became the engineer in charge. As reflected in a diary entry he made in 1885, during his time in the Navy, he resolved to be the first man to reach the ].<ref name=Mills510/> | |||

| After returning to the ''Roosevelt'' in May, Peary in June began weeks of further agonizing travel by heading west along the shore of Ellesmere, discovering Cape Colgate, from the summit of which he claimed in his 1907 publications<ref>E. g., R. Peary, ''Nearest the Pole'', 1907, pages 202, 207, and 280</ref> he had seen a previously undiscovered far-north "]" to the northwest on June 24 of 1906. Yet his diary for this time and place says "No land visible"<ref>Rawlins, </ref> and Crocker Land was in 1914 found to be non-existent by ] and Fitzhugh Green. On December 15, 1906, the National Geographic Society, which was primarily known for publishing a popular magazine, certified Peary's 1905-6 expedition and Farthest with its highest honor, the Hubbard Gold Medal; no major professional geographical society followed suit. | |||

| In April 1886, he wrote a paper for the ] proposing two methods for crossing Greenland's ice cap. One was to start from the west coast and trek about {{convert|400|mi|abbr=on}} to the east coast. The second, more difficult path, was to start from ] at the top of the known portion of ] and travel north to determine whether Greenland was an island or if it extended all the way across the Arctic.<ref name=Mills511/> Peary was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander on January 5, 1901, and to commander on April 6, 1902.<ref name=NavalHistory/> | |||

| ===The final 1908–1909 expedition=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ], ] in 1909]] | |||

| ] | |||

| For his final assault on the pole, he and 23 men, including ], set off from ] aboard the '']'' under the command of Captain ] on July 6, 1908. They wintered near ] on ] and from Ellesmere departed for the pole on February 28 – March 1, 1909. The last support party was turned back from "Bartlett Camp" on April 1, 1909, in latitude no greater than 87°45' north. (The figure commonly given, 87°47', is based upon Bartlett's slight miscomputation of the distance of a single ] from the pole.) On the final stage of the journey towards the North Pole only five of Peary's men, ], Ootah, Egigingwah, ] and Ooqueah, remained. On April 6, he established "Camp Jesup" allegedly within {{convert|5|mi|km}} of the pole. In his diary for April 7, Peary wrote: "The Pole at last!!! The prize of three centuries, my dream and ambition for twenty-three years. Mine at last." | |||

| Peary was unable to enjoy the fruits of his labors to the full extent when, upon returning to civilization, he learned that Dr. ], who had been a surgeon on an 1891–1892 Peary expedition, claimed to have reached the pole the year before. | |||

| ==Initial Arctic expeditions== | |||

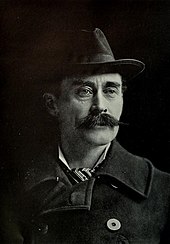

| In 1913 Peary was photographed with ] explorer ]<ref></ref> and ] explorer ]<ref></ref> | |||

| Peary made his first expedition to the ] in 1886, intending to cross Greenland by ], taking the first of his own suggested paths. He was given six months' leave from the Navy, and he received $500 from his mother to book passage north and buy supplies. He sailed on a ] to Greenland, arriving in ] on June 6, 1886.<ref name=Mills510/> Peary wanted to make a solo trek, but Christian Maigaard, a young Danish official, convinced him he would die if he went out alone. Maigaard and Peary set off together and traveled nearly {{convert|100|mi|abbr=on}} due east before turning back because they were short on food. This was the second-farthest penetration of Greenland's ice sheet at the time. Peary returned home knowing more of what was required for long-distance ice trekking.<ref name=Mills511>Mills 2003, p. 511.</ref> | |||

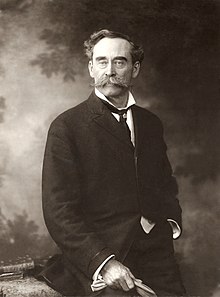

| ], Peary's assistant, in 1910]] | |||

| ===Honors and legacy=== | |||

| Back in Washington attending with the US Navy, in November 1887 Peary was ordered to survey likely routes for a proposed Nicaragua Canal. To complete his tropical outfit he needed a sun hat. He went to a men's clothing store where he met 21-year-old ], a black man working as a sales clerk. Learning that Henson had six years of seagoing experience as a ], Peary immediately hired him as a personal ].<ref name=Nuttall855>Nuttall 2012, p. 855–856.</ref> | |||

| ], ].]] | |||

| On assignment in the jungles of Nicaragua, Peary told Henson of his dream of Arctic exploration. Henson accompanied Peary on every one of his subsequent Arctic expeditions, becoming his field assistant and "first man", a critical member of his team.<ref name=Mills511/><ref name=Nuttall855/> | |||

| Peary's lobbying<ref>See Congressman de Alva Alexander in Rawlins, 1973.</ref> early headed off an intention among some congressmen to have his claim to the pole evaluated by explorers. As eventual congressionally recognized "attainer" of the pole (not "discoverer" in deference to 1908 North Pole claimant ]'s supporters) Peary was given a ]'s pension and the ] by a special act of March 30, 1911. In the same year, he retired to ] on the coast of ], in the town of Harpswell. (His home there is now a Maine State Historic Site.) Civil Engineer Peary received honors from numerous scientific societies of Europe and America for his Arctic explorations and discoveries. He died in Washington, D.C., February 20, 1920, and was buried in ]. Matthew Henson was reinterred nearby on April 6, 1988. | |||

| ==Second Greenland expedition== | |||

| The ] ], the ] ] Edsall class Destroyer Escort USS Peary (DE 132) the cargo ship ], Knox-class frigate ] and ice rated, US-flagged tanker ] were named for him. The at Bowdoin College is named for Peary and fellow Arctic explorer ]. On May 28, 1986, the ] issued a 22 cent ] in honor of Peary and Henson;<ref>] # 2223.</ref> they were previously honored in 1959.<ref>] # 1128.</ref><ref>"Veterans and the Military on Stamps", pp. 5, 30, found at . Retrieved September 25, 2008.</ref> | |||

| In the ], Peary took the second, more difficult route that he laid out in 1886: traveling farther north to find out whether Greenland was a larger landmass extending to the North Pole. He was financed by several groups, including the ], the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences (now the ]), and the ]. Members of this expedition included Peary's aide Henson, ], who served as the group's surgeon; the expedition's ethnologist, Norwegian skier ]; bird expert and marksman Langdon Gibson, and John M. Verhoeff, who was a weatherman and mineralogist. Peary also took his wife along as dietitian, though she had no formal training.<ref name=Mills511/> Newspaper reports criticized Peary for bringing his wife.<ref name="Conefrey">{{cite book | title=How to Climb Mt. Blanc in a Skirt: A Handbook for the Lady Adventurer | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=q4UbYjoz0-EC&pg=PT103 | page=103 | first=Mick | last=Conefrey | publisher=] | year=2011 | isbn=9780230112421}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Peary was the author of several books, the most famous being ''Northward over the Great Ice'' (1898) and ''The North Pole'' (1910). The movie ''Glory & Honor'' by Kevin Hooks (1998) effectively dramatizes his hellish 1909 journey to the vicinity of the pole. Even explorer A. Greely, who came (after initial acceptance) to doubt Peary's reaching 90°, correctly notes that no Arctic expert questions that (unlike Cook) Peary courageously risked his life travelling hundreds of miles from land and that he reached regions adjacent to the pole. | |||

| On June 6, 1891, the party left Brooklyn, New York, in the seal hunting ship SS ''Kite''. In July, as ''Kite'' was ramming through sheets of surface ice, the ship's iron ] suddenly spun around and broke Peary's lower leg; both bones snapped between the knee and ankle.<ref name=Mills511/><ref name=Conefrey/><ref name=Journal>{{cite book | title=My Arctic Journal: A Year among Ice-fields and Eskimos | url=https://archive.org/details/myarcticjournaly00pear | page= | last=Peary | first=Josephine Diebitsch | author-link=Josephine Diebitsch Peary | publisher=] | year=1894}}</ref> Peary was unloaded with the rest of the supplies at a camp they called Red Cliff, at the mouth of ] at the north west end of ]. A dwelling was built for his recuperation during the next six months. ] stayed with Peary. Gibson, Cook, Verhoeff, and Astrup hunted game by boat and became familiar with the area and the ].<ref name=Mills511/> | |||

| ] | |||

| In his book ''Ninety Degrees North'', polar historian and author Fergus Fleming describes Peary as "undoubtedly the most driven, possibly the most successful and probably the most unpleasant man in the annals of polar exploration." | |||

| Unlike most previous explorers, Peary had studied ] survival techniques; he built ]s during the expedition and dressed in practical furs in the native fashion. By wearing furs to preserve body heat and building igloos, he was able to dispense with the extra weight of tents and sleeping bags when on the march. Peary also relied on the Inuit as hunters and dog-drivers on his expeditions. He pioneered the system of using support teams and establishing supply caches for Arctic travel, which he called the "Peary system". The Inuit were curious about the Americans and came to visit Red Cliff. Josephine was bothered by the Inuit body odor from not bathing, their flea infestations, and their food. She studied the people and kept a journal of her experiences.<ref name=Conefrey/><ref name=Journal/> In September 1891, Peary's men and dog sled teams pushed inland onto the ice sheet to lay caches of supplies. They did not go farther than {{convert|30|mi|abbr=on}} from Red Cliff.<ref name=Mills511/> | |||

| In 1891, Peary shattered his leg in a shipyard accident but it healed by February 1892. By April 1892, he made some short trips with Josephine and an Inuit dog sled driver to native villages to purchase supplies. On May 3, 1892, Peary finally set out on the intended trek with Henson, Gibson, Cook, and Astrup. After {{convert|150|mi|abbr=on}}, Peary continued on with Astrup. They found the {{convert|1000|m|abbr=on|order=flip}} high view from Navy Cliff, saw ], and concluded that ] was an island. They trekked back to Red Cliff and arrived on August 6, having traveled a total of {{convert|1250|mi|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Mills511/> | |||

| ====Awards==== | |||

| *American Geographical Society ] (1896) | |||

| *American Geographical Society ] (1902)<ref name="amergeog">{{cite web|url=http://www.amergeog.org/honorslist.pdf|title=American Geographical Society Honorary Fellowships|publisher=amergeog.org|accessdate=March 2, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| *The Royal Geographical Society of London special great gold medal | |||

| *The National Geographic Society of Washington the special great gold medal | |||

| *The Philadelphia Geographical Society great gold medal | |||

| *The Chicago Geographical Society Helen Culver medal | |||

| *Bowdoin College bestowed the honorary degree of doctor of laws | |||

| *New York Chamber of Commerce honorary member. | |||

| *Pennsylvania Society Honorary member | |||

| *Imperial German Geographical Society Nachtigall gold medal | |||

| *Royal Italian Geographical Society King Humbert gold medal | |||

| *Imperial Austrian Geographical Society | |||

| *Hungarian Geographical Society gold medal | |||

| *Royal Belgian Geographical Society gold medal | |||

| *Royal Geographical Society of Antwerp gold medal | |||

| *Royal Scottish Geographical Society special trophy from the -a replica in silver of the ships used by Hudson, Baffin, and Davis. | |||

| *Edinburgh University bestowed an honorary degree of doctor of laws | |||

| *Manchester Geographical Society Honorary membership | |||

| *Royal Netherlands Geographical Society of Amsterdam Honorary membership<ref>{{Cite web | |||

| | last = | |||

| | first = | |||

| | authorlink = | |||

| | last2 = | |||

| | first2 = | |||

| | authorlink2 = | |||

| | title = Recognition of Robert E. Peary the Arctic explorer | |||

| | date = January 21, 1911 | |||

| | year = | |||

| | url = http://docs.lib.noaa.gov/rescue/IPY/IPY_017_pdf/G635p4b381911.pdf | |||

| |format=PDF| accessdate =August 21, 2008 | |||

| | postscript = <!--None--> }}</ref> | |||

| *Grand Officer of the ], awarded 1913<ref>Appleton's cyclopædia of American biography, Volume 8 edited by James Grant Wilson, John Fiske, 1918, pg. 527</ref> | |||

| In 1896, Peary, a ], received his degrees in Kane Lodge No. 454, ].<ref>{{cite web | url=http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/textfiles/famous.html | title=List of famous freemasons | website=freemasonry.bcy.ca | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20011004153632/http://freemasonry.bcy.ca/textfiles/famous.html | archive-date=October 4, 2001 | url-status=live}}</ref><ref name=Freemasons>{{cite web | url=https://stjohnslodgedc.org/famous-masons | title=Famous Freemasons in the course of history | publisher=St. John's Lodge, Washington, D.C. | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151116030150/http://www.stjohnslodgedc.org/famous-masons | archive-date=November 16, 2015 | url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Inuit descendants=== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| Some modern critics of Peary focus on his treatment of the Inuit, including ], a boy who, with five other Inuit, was brought to the United States from Greenland in 1897. Most of them died, and Wallace had considerable difficulty in returning to his home. Other criticisms involve Peary's theft of several enormous meteorites from the same Inuit band. These allegedly were the only local source of iron, and were sold by Peary for $50,000. | |||

| ==1898–1902 expeditions== | |||

| Peary and Henson both fathered children with Inuit women outside of marriage. (So did many other European explorers of the Arctic; for example, ] fathered a son during the filming of '']''.) This was brought up by Cook and his followers during Peary's lifetime and would have damaged his advancement if it had been widely believed. Peary appears to have started his relationship with his Inuit wife Aleqasina (Alakahsingwah) when she was about 14 years old.<ref>{{Cite journal | |||

| ] on ] during his 1898–1902 expedition]] | |||

| | last = Herbert | |||

| As a result of Peary's 1898–1902 expedition, he claimed an 1899 visual discovery of "Jesup Land" west of ].<ref>{{cite journal | author=William Herbert Hobbs | title=The Progress of Discovery and Exploration Within the Arctic Region | journal=] | year=1937 | volume=27 | issue=1 | page=16 | doi=10.1080/00045603709357155}}</ref> He claimed that this sighting of ] was prior to its discovery by Norwegian explorer ]'s expedition around the same time. This contention has been universally rejected by exploration societies and historians.<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=v6THcynQQDMC | author=Harold Horwood | title=Bartlett: The Great Explorer | publisher=] | year=2010 | page=56| isbn=9780385674355 }}</ref> However, the American Geographical Society and the ] honored Peary for tenacity, mapping of previously uncharted areas, and his discovery in 1900 of ] at the north tip of Greenland. Peary also achieved a "farthest north" for the western hemisphere in 1902 north of Canada's ]. Peary was promoted to ] in the Navy in 1901 and to ] in 1902.<ref>Register of Commissioned Officers of the United States Navy. Editions of 1902 and 1903.</ref> | |||

| | first = Wally | |||

| | author-link = | |||

| | title = The Noose of Laurels | |||

| | year = 1989 | |||

| | pages = 206–207 | |||

| | postscript = <!--None-->}}</ref> Furthermore, Peary's main financial backer was New York philanthropist ], a major force in the founding of ]'s ]. Many of the explorers knew the facts, but had no wish to mention them publicly, in case this endangered their financial backing by scandal-shy geographical societies or their own Inuit relationships. | |||

| ==1905–1906 expedition== | |||

| By the 1960s the truth was widely acknowledged, and Peary’s son Kali was eventually brought to the attention of the broader American public by S. Allen Counter, who met him on a North America expedition. The "discovery" of these children and their meeting with their American relatives were documented in a book and documentary titled ''North Pole Legacy: Black, White and Eskimo''. | |||

| Peary's next expedition was supported by fundraising through the ], with gifts of $50,000 from George Crocker, the youngest son of banker ], and $25,000 from ], to buy Peary a new ship.<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/1905/07/13/archives/peary-gets-50000-mk-jesup-gives-25000-fund-for-trip-to-reach-north.html | title=Peary Gets $50,000; M.K. Jesup Gives $25,000 | work=] | date=July 13, 1905 | page=7}}</ref> The {{SS|Roosevelt|1905|6}} navigated through the ice between ] and ], establishing an American hemisphere "farthest north by ship". The 1906 "Peary System" dogsled drive for the pole across the rough sea ice of the Arctic Ocean started from the north tip of Ellesmere at 83° north latitude. The parties made well under {{convert|10|mi|abbr=on}} a day until they became separated by a storm. | |||

| ] in 1909]] | |||

| ==Controversy== | |||

| As a result, Peary was without a companion sufficiently trained in navigation to verify his account from that point northward. With insufficient food, and uncertainty whether he could negotiate the ice between himself and land, he made the best possible dash and barely escaped with his life from the melting ice. On April 20, he was no farther north than 86°30' latitude. This latitude was never published by Peary. It is in a typescript of his April 1906 diary, discovered by ] in his assessment commissioned by the ]. The typescript suddenly stopped there, one day before Peary's April 21 purported "farthest". The original of the April 1906 record is the only missing diary of Peary's exploration career.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://collections.dartmouth.edu/arctica-beta/html/EA15-55.html | title=Robert Edwin Peary | publisher=]}}</ref> He claimed the next day to have achieved a ] world record at 87°06' and returned to 86°30' without camping. This implied a trip of at least {{convert|72|nmi|lk=in}} between sleeping, even assuming direct travel with no detours. | |||

| Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole has long been subject to doubt.<ref></ref> Some polar historians believe that Peary honestly thought he had reached the pole. Others have suggested that he was guilty of deliberately exaggerating his accomplishments. In recent years, Peary's account has encountered renewed criticism and skepticism, as reviewed by Berton (2001) and Henderson (2005). | |||

| After returning to ''Roosevelt'' in May, Peary began weeks of difficult travel in June heading west along the shore of Ellesmere. He discovered Cape Colgate, from whose summit he claimed in his 1907 book<ref>R. Peary, ''Nearest the Pole'', 1907, pp. 202, 207, 280.</ref> that he had seen a previously undiscovered far-north "]" to the northwest on June 24, 1906. A later review of his diary for this time and place found that he had written, "No land visible."<ref>{{Cite web | url=http://www.dioi.org/cot.htm#ypcx | title=Contributions Dennis Rawlins 2 | website=dioi.org | publisher=The International Journal of Scientific History}}</ref> On December 15, 1906, the National Geographic Society of the United States, certified Peary's 1905–1906 expedition and "Farthest" with its highest honor, the ]. No major professional geographical society followed suit. In 1914, ] and Fitzhugh Green's expedition found that Crocker Land did not exist. | |||

| ==Claiming to reach the North Pole== | |||

| ] | |||

| On July 6, 1908, the ''Roosevelt'' departed New York City with Peary's eighth Arctic expedition of 22 men. Besides Peary as expedition commander, it included master of the ''Roosevelt'' ], surgeon Dr. J.W. Goodsell, along with ], ], George Borup, and ]. After recruiting several Inuit and their families at ], the expedition wintered near ] on ]. The expedition used the "Peary system" for the sledge journey, with Bartlett and the Inuit, Poodloonah, "Harrigan," and Ooqueah, composing the pioneer division. Borup, with three Inuit, Keshunghaw, Seegloo, and Karko, composed the advance supporting party. On February 15, Bartlett's pioneer division departed the ''Roosevelt'' for ], followed by 5 advance divisions. Peary, with the two Inuit, Arco and Kudlooktoo, departed on February 22, bringing to the total effort 7 expedition members, 19 Inuit, 140 dogs, and 28 sledges. On February 28, Bartlett, with three Inuit, Ooqueah, Pooadloonah, and Harrigan, accompanied by Borup, with three Inuit, Karko, Seegloo, and Keshungwah, headed North.<ref name="rp">{{cite book |last=Peary | first=Robert | title=The North Pole: Its Discovery in 1906 Under the Auspices of the Peary Arctic Club | date=1986 | publisher=Dover Publications, Inc. | location=New York | isbn=0486251292 | pages=23,25,42,72,121,201–203,213–214,298}}</ref>{{rp|41}} | |||

| On March 14, the first supporting party, composed of Dr. Goodsell and the two Inuit, Arco and Wesharkoupsi, turned back towards the ship. Peary states this was at a latitude of 84°29'. On March 20, Borup's third supporting party, with three Inuit, started back to the ship. Peary states this was at a latitude of 85°23'. On March 26, Marvin, with Kudlooktoo and Harrigan, headed back to the ship, from a latitude estimated by Marvin as 86°38'. Marvin died on this return trip south. On 1 April, Bartlett's party started their return to the ship, after Bartlett estimated a latitude of 87°46'49". Peary, with two Inuit, Egingwah and Seeglo, and Henson, with two Inuit, Ootah and Ooqueah, using 5 sledges and 40 dogs, planned 5 marches over the estimated 130 ]s to the pole. On 2 April, Peary led the way north.<ref name=rp/>{{rp|235,243,252–254,268–271,274}}<ref name=Negro>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=vfvfyQEACAAJ | last=Henson | first=Matthew | authorlink=Matthew Henson | title=A Negro Explorer at the North Pole | date=1912 | publisher=] | isbn=9781406553741 | pages=52,57,61,63,68–71,318–319}}</ref> | |||

| On the final stage of the journey toward the North Pole, Peary told Bartlett to stay behind. He continued with five others: Henson, Ootah, Egigingwah, Seegloo, and Ooqueah. No one except Henson, who had served on the ], had experience of naval-type observations. On April 6, 1909, Peary established Camp Jesup within {{convert|3|mi|abbr=on|0}} of the pole, according to his own readings.<ref>{{Cite web | title=Profile: African-American North Pole Explorer Matthew Henson | url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/profile-african-american-north-pole-explorer-matthew-henson | first=ANNA | last=BRENDLE | publisher=] |date=January 10, 2003}}</ref> Peary estimated the latitude as 89°57', after making an observation at approximate local noon using the Columbia meridian. Peary used a sextant, with a mercury trough and glass roof for an artificial horizon, to make measurements of the Sun. Peary claims, "I had now taken in all thirteen single, or six and one-half double, altitudes of the sun, at two different stations, in three different directions, at four different times." Peary states some of these observations were "beyond the Pole," and "...at some moment during these marches and counter-marches, I had passed over or very near the point where north and south and east and west blend into one."<ref name=rp/>{{rp|287–298}}<ref name=Negro/>{{rp|72–75}} Henson scouted ahead to what was thought to be the North Pole site; he returned with the greeting, "I think I'm the first man to sit on top of the world," much to Peary's chagrin.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.cbp.gov/about/history/did-you-know/first-man | title=Did You Know... A Customs Employee was the 'First Man to Sit on Top of the World?' | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| On April 7, 1909, Peary's group started their return journey, reaching Cape Columbia on April 23, and the ''Roosevelt'' on April 26. MacMillan and the doctor's party had reached the ship earlier, on March 21, Borup's party on April 11, Marvin's Inuit on April 17, and Bartlett's party on April 24. On July 18, the ''Roosevelt'' departed for home.<ref name=rp/>{{rp|302,316–317,325,332}}<ref name=Negro/>{{rp|78–81}} | |||

| Upon returning, Peary learned that Dr. ], a surgeon and ethnographer on the ], claimed to have reached the North pole in 1908.<ref name=Discovered/> Despite remaining doubts, a committee of the National Geographic Society, as well as the Naval Affairs Subcommittee of the ], credited Peary with reaching the North Pole.<ref name=Discovered>{{cite magazine | last=Henderson | first=Bruce | title=Who Discovered the North Pole? | url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/who-discovered-the-north-pole-116633746/ | magazine=] | date=April 2009}}</ref> | |||

| A reassessment of Peary's notebook in 1988 by polar explorer ] found it "lacking in essential data", thus renewing doubts about Peary's discovery.<ref name=Doubts>{{cite news | last=Wilford | first=John N. | title=Doubts cast on Peary's claim to Pole | url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1988/08/22/031988.html?zoom=14.63&pageNumber=27 | work=] | date=August 22, 1988}}</ref><ref name=First>{{cite news | last=Tierney | first=John | title=Who Was First at the North Pole?| url=https://tierneylab.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/09/07/who-was-first-at-the-north-pole | work=] | date=September 7, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| ==Later life and death== | |||

| ], ], and Peary, in January 1913]] | |||

| ], April 6, 1922]] | |||

| Peary was promoted to the rank of captain in the Navy in October 1910.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/research-guides/z-files/zb-files/zb-files-p/peary-robert-e.html | title=Robert Edwin Peary | publisher=]}}</ref> By his lobbying, Peary headed off a move among some U.S. Congressmen to have his claim to the pole evaluated by other explorers. Eventually recognized by Congress for "reaching" the pole, Peary was given the ] by a special act in March 1911.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.navalhistory.org/2013/01/18/peary-at-the-north-pole | title=Peary at the North pole | publisher=] | date=January 18, 2013}}</ref> By the same Act of Congress, Peary was promoted to the rank of ] in the Navy Civil Engineer Corps, retroactive to April 6, 1909. He retired from the Navy the same day, to ] on the coast of ], in the town of Harpswell. His home there has been designated a Maine State Historic Site.<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://bangordailynews.com/2013/12/09/news/north-pole-explorers-maine-home-nominated-as-national-historic-landmark/ | title=North Pole explorer's Maine home nominated as National Historic Landmark | first=Abigail | last=Curtis | work=] | date=December 9, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| After retiring, Peary received many honors from scientific societies for his Arctic explorations and discoveries. He served twice as president of ], from 1909 to 1911, and from 1913 to 1916. | |||

| In early 1916, Peary became chairman of the National Aerial Coast Patrol Commission, a private organization created by the ]. It advocated the use of aircraft to detect warships and submarines off the U.S. coast.<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://www.history.navy.mil/content/dam/nhhc/research/histories/naval-aviation/dictionary-of-american-naval-aviation-squadrons-volume-2/pdfs/Chap_1.pdf | title=Origins of Navy Patrol Aviation, 1911 to 1920s}}</ref> Peary used his celebrity to promote the use of military and naval aviation, which led directly to the formation of ] aerial coastal patrol units during ]. After the war, Peary proposed a system of eight airmail routes, which became the genesis of the U.S. Postal Service's airmail system.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c84q815p/entire_text/ | title=Guide to the Frederick A. Cook and Robert E. Peary Collection MSS.2017.07.14 | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| In 1914, Peary bought the house at 1831 Wyoming Avenue NW in the ] neighborhood of ], where he lived until his death on February 20, 1920.<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.baltimoresun.com/news/bs-xpm-1995-06-25-1995176044-story.html | title=Washington's present meets the past in Adams-Morgan NEIGHBORHOOD TOUR | first=Ralph | last=Vigoda | work=] | date=June 25, 1995 | url-access=limited}}</ref> He began renovating the house in 1920, shortly before his death, after which the renovation was taken over by Josephine. She sold the house in 1927, receiving a $12,000 promissory note.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/ade/item/95858654/ | title=Architectural drawing for alterations to a row house ("residence") for Josephine D. Peary (originally for Adm. Robert E. Peary), 1831 Wyoming Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. | year=1920 | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| He was buried in ].<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Explore/Notable-Graves/Explorers/Robert-Peary | title=Robert Peary | publisher=]}}</ref> Matthew Henson was honored by being re-interred nearby on April 6, 1988.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://www.arlingtoncemetery.mil/Explore/Notable-Graves/Explorers/Matthew-Henson | title=Matthew Alexander Henson | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ==Marriage and family== | |||

| ] in 1892]] | |||

| On August 11, 1888, Peary married ], a business school valedictorian who thought that women should be more than just mothers. Diebitsch had started working at the ] when she was 19 or 20 years old, replacing her father after he became ill and filling his position as a ]. In 1886, she resigned from the Smithsonian upon becoming engaged to Peary. | |||

| The newlyweds honeymooned in ], then moved to ], where Peary was assigned. Peary's mother accompanied them on their honeymoon, and she moved into their Philadelphia apartment, which caused friction between the two women. Josephine told Peary that his mother should return to live in Maine.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://arcticportal.org/ap-library/arctic-deeply/1945-the-forgotten-indigenous-women-of-robert-peary-s-arctic-expeditions | title=The Forgotten Indigenous Women of Robert Peary's Arctic Expeditions | publisher=Arctic Portal | date=August 10, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| They had two children together, Marie Ahnighito (born 1893) and Robert Peary, Jr. His daughter wrote several books, including ''The Red Caboose'' (1932) a children's book about the Arctic adventures published by ]. As an explorer, Peary was frequently gone for years at a time. In their first 23 years of marriage, he spent only three with his wife and family. | |||

| Peary and his aide, Henson, both had relationships with Inuit women outside of marriage and fathered children with them.<ref>{{cite book | last=Sherman | first=Josepha | author-link=Josepha Sherman | date=2005 | title=Exploring the North Pole: The Story of Robert Edwin Peary and Matthew Henson | publisher=Mitchell Lane Publishers | isbn=9781584154020 | url=https://archive.org/details/exploringnorthpo0000sher |url-access=registration}}</ref> Peary appears to have started a relationship with Aleqasina (''Alakahsingwah'') when she was about 14 years old.<ref name=Noose>{{cite book | last=Herbert | first=Wally | author-link=Wally Herbert | date=1989 | title=The Noose of Laurels | url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780689120343 | url-access=registration | pages=| publisher=Atheneum | isbn=9780689120343 }}</ref><ref name=plug>{{Cite news |url=https://nativetimes.com/life/people/5994-us-explorers-inuit-kin-plug-into-globalized-world | title=US explorers' Inuit kin plug into globalized world | last=Hanley | first=Charles J. | work=] | date=September 7, 2011}}</ref> They had at least two children, including a son called Kaala,<ref name=plug/> Karree,<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/1987/07/13/anaukaq-henson-80-dies/5406beb9-9bf7-4f31-839d-f1ac55079fe8/ | title=Anaukaq Henson, 80, dies | newspaper=] | date=July 13, 1987}}</ref> or Kali.<ref name=shoulders>{{Cite news | url=http://nunatsiaq.com/stories/article/Matthew_Hensons_descendants_honour_their_ancestor/ | first=Jane | last=George | title=Standing on the shoulders of a giant; Matthew Henson's descendants honour their ancestor | work=Nunatsiaq News Online | date=April 9, 2009}}</ref> French explorer and ethnologist ] was the first to report on Peary's descendants after spending a year in Greenland in 1951–52.<ref name=plug/><ref></ref> | |||

| ], a ] neuroscience professor interested in Henson's role in the Arctic expeditions, went to Greenland in 1986. He found Peary's son Kali and Henson's son Anaukaq, then octogenarians, and some of their descendants.<ref name=shoulders/> Counter arranged to bring the men and their families to the United States to meet their American relatives and see their fathers' gravesites.<ref name=shoulders/> In 1991, Counter wrote about the episode in his book, ''North Pole Legacy: Black, White, and Eskimo'' (1991). He also gained national recognition of Henson's role in the expeditions.<ref name=shoulders/> A documentary by the same name was also released. Wally Herbert also noted the relationship and children in his book ''The Noose of Laurels'', published in 1989.<ref name=Noose/> | |||

| ==Treatment of the Inuit== | |||

| ] tusk lance with an iron head made from the ].]] | |||

| ], one of the Inuit whom Peary took back to America for study.]] | |||

| Peary has received criticism for his treatment of the Inuit, including fathering children with Aleqasina. Renée Hulan and Lyle Dick have both reported that Peary and his crew sexually exploited Inuit women on his 1908–1909 expedition.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Hulan |first1=Renée |title=Alnayah's People: Archival Photographs from West Greenland, 1908–1909 |journal=Interventions |date=2023 |volume=25 |issue=8 |pages=1088–1109|doi=10.1080/1369801X.2023.2169621 }}</ref> <ref>{{cite journal |last1=Dick |first1=Lyle |title='"Pibloktoq"(Arctic Hysteria): A Construction of European-Inuit Relations?' |journal=Arctic Anthropology |date=1995 |volume=32 |issue=2 |pages=1–42 |jstor=40316385 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/40316385}}</ref> Peary has also been harshly criticized for bringing back a group of ] to the United States along with the ]. The meteorite was of significant local economic importance: Although the Greenlanders had been obtaining the iron they needed from whalers, the Cape York meteorite was the only source of iron for tools. Peary sold it for $40,000 in 1897.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/article/the-legacy-of-arctic-explorer-matthew-henson | title=The Legacy of Arctic Explorer Matthew Henson | work=] | date=February 28, 2014}}</ref> | |||

| Working at the ], ] ] had requested that Peary bring back an Inuit for study.<ref>{{Cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=47HtAAAAMAAJ | last=Thomas | first=David H. | title=Skull Wars: Kennewick Man, Archaeology, and the Battle for Native American Identity | date=March 14, 2000 | page=78 | publisher=]| isbn=9780465092246 }}</ref><ref name=GiveMe>{{Cite book | last=Harper | first=Kenn | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=wK2-ONmUk0YC | title=Give Me My Father's Body: The Life of Minik, the New York Eskimo' | publisher=] | year=2001| isbn=9780743410052 }}</ref><ref name=Meteor>{{cite web | last1=Meier | first1=Allison | title=Minik and the Meteor | date=March 19, 2013 | url=https://narratively.com/minik-and-the-meteor/ | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20200726233201/https://narratively.com/minik-and-the-meteor/ | archive-date=July 26, 2020 | url-status=live}}</ref> During his expedition to retrieve the meteorite, Peary convinced six people, including a man named Qisuk and his child ], to travel to America with him by promising they would be able to return with tools, weapons and gifts within the year.<ref name=Northern>{{cite book | last1=Petrone | first1=Penny | title=Northern Voices: Inuit Writing in English | date=January 1992 | publisher=] | isbn=9780802077172}}</ref> Peary left the people at the museum when he returned with the meteorite in 1897, where they were kept in damp, humid conditions unlike their homeland. Within a few months, four died of ]; their remains were dissected and the bones of Qisuk were put on display after Minik was shown a fake burial.<ref name=Meteor/><ref name=GiveMe/> | |||

| Speaking as a teenager to the '']'' about Peary, ] said: | |||

| {{blockquote|At the start, Peary was kind enough to my people. He made them presents of ornaments, a few knives and guns for hunting and wood to build sledges. But as soon as he was ready to start home his other work began. Before our eyes he packed up the bones of our dead friends and ancestors. To the women’s crying and the men’s questioning he answered that he was taking our dead friends to a warm and pleasant land to bury them. Our sole supply of flint for lighting and iron for hunting and cooking implements was furnished by a huge meteorite. This Peary put aboard his steamer and took from my poor people, who needed it so much. After this he coaxed my father and that brave man Natooka, who were the strongest hunters and the wisest heads for our tribe, to go with him to America. Our people were afraid to let them go, but Peary promised them that they should have Natooka and my father back within a year, and that with them would come a great stock of guns and ammunition, and wood and metal and presents for the women and children … We were crowded into the hold of the vessel and treated like dogs. Peary seldom came near us.<ref name=Northern/>}} | |||

| Peary eventually helped Minik travel home in 1909, though it is speculated that this was to avoid any bad press surrounding his anticipated celebratory return after reaching the North Pole.<ref name=Meteor/> In 1986, ] wrote a book about Minik, entitled ''Give Me My Father's Body''. Convinced that the remains of Qisuk and the three adult Inuit should be returned to Greenland, he tried to persuade the Museum of Natural History to do this, as well as working through the "red tape" of the US and Canadian governments. In 1993, Harper succeeded in having the Inuit remains returned.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Harper |first=Kenn |date=2002-01-01 |title=The Minik Affair: The Role of the American Museum of Natural History |url=https://doi.org/10.1080/789609352 |journal=Polar Geography |volume=26 |issue=1 |pages=39–52 |doi=10.1080/789609352 |bibcode=2002PolGe..26...39H |s2cid=140717778 |issn=1088-937X}}</ref> In ], he witnessed the Inuit funeral ceremony for the remains of Qisuk and the three tribesmen that had been taken to New York. | |||

| Peary had employed the Inughuit in his expeditions for more than a decade, paying them in firearms, ammunition and other Western goods on which they had come to rely, and leaving them in a dire situation in 1909. The demands of the American expeditions had also resulted in the caribou of North Greenland being hunted to near extinction.<ref name="Schledermann2003">{{cite journal | |||

| |title=The Muskox Patrol: High Arctic Sovereignty Revisited | |||

| |first=Peter | |||

| |last=Schledermann | |||

| |journal=] | |||

| |volume=56 | |||

| |number=1 | |||

| |date=March 2003 | |||

| |pages=102 | |||

| |jstor=40512169 | |||

| |doi=10.14430/arctic606 | |||

| |url=https://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/arctic/article/view/63665/47601 | |||

| |doi-access=free | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Controversy surrounding North Pole claim== | |||

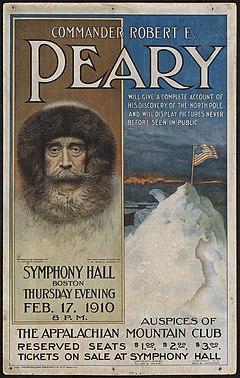

| ] in February 1910]] | |||

| Peary's claim to have reached the North Pole has long been subject to doubt.<ref name=Doubts/><ref>{{cite news |title=A Correction |url=https://www.nytimes.com/1988/08/23/opinion/c-a-correction-310788.html |url-access=subscription |access-date=February 24, 2024 |newspaper=] |date=August 23, 1988 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20090908201355/https://www.nytimes.com/1988/08/23/opinion/c-a-correction-310788.html?scp=3&sq=%20Cook%20Peary%20correction%20north%20pole%20neither&st=cse |archive-date=September 8, 2009}}</ref><ref name=Discovered/> Some polar historians believe that Peary honestly thought he had reached the pole. Others have suggested that he was guilty of deliberately exaggerating his accomplishments. Peary's account has been newly criticized by ] (2001) and Bruce Henderson (2005). | |||

| ===Lack of independent validation=== | ===Lack of independent validation=== | ||

| Peary did not submit his evidence for review to neutral national or international parties or to other explorers. |

Peary did not submit his evidence for review to neutral national or international parties or to other explorers.<ref name=Discovered/> Peary's claim was certified by the ] (NGS) in 1909 after a cursory examination of Peary's records, as NGS was a major sponsor of his expedition.<ref name=Discovered/> This was a few weeks before Cook's Pole claim was rejected by a Danish panel of explorers and navigational experts. | ||

| The National Geographic Society limited access to Peary's records. At the time, his proofs were not made available for scrutiny by other professionals, as had been done by the Danish panel.<ref name=Discovered/> ] persuaded the ] not to get involved. The ] (RGS) of London gave Peary a one-off medal (created by sculptor ], later widow of ]), in 1910,<ref>{{cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/1909/12/16/archives/nations-hail-peary-as-pole-discoverer-felicitations-from-england.html | title=Nations Hail Peary as Pole Discoverer | work=] | date=December 16, 1909}}</ref> despite internal council splits which only became known in the 1970s. The RGS based their decision on the belief that the NGS had performed a serious scrutiny of the "proofs", which was not the case.{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} Neither the ] nor any of the geographical societies of semi-Arctic ] has recognized Peary's North Pole claim. | |||

| ===Criticisms=== | ===Criticisms=== | ||

| {{see also|Peary Channel (Greenland)}} | |||

| {{more citations needed|date=April 2019}} | |||

| ====Omissions in navigational documentation==== | ====Omissions in navigational documentation==== | ||

| The party that accompanied Peary on the final stage of the journey |

The party that accompanied Peary on the final stage of the journey did not include anyone trained in navigation who could either confirm or contradict Peary's own navigational work. This was further exacerbated by Peary's failure to produce records of observed data for steering, for the direction ("]") of the compass, for his longitudinal position at any time, or for zeroing-in on the pole either latitudinally or transversely beyond Bartlett Camp.<ref>Herbert, 1989; Rawlins, </ref> | ||

| ====Inconsistent speeds==== | ====Inconsistent speeds==== | ||

| ] in 1909]] | |||

| The last five marches when Peary was accompanied by a navigator (Capt. Bob Bartlett) averaged no better than {{convert|13|mi|km}} march northing. But once the last support party turned back at "Camp Bartlett" from where Bartlett was ordered southward, at least {{convert|133|nmi|km}} from the pole, Peary's claimed speeds immediately double for the five marches to Camp Jesup, and then quadrupled during the 2½ day return to Camp Bartlett—at which point his speed slowed drastically compared to that pace. Peary's account of a beeline journey to the pole and back — which would have assisted his claim of such speed — is contradicted by companion ]'s account of tortured detours to avoid "pressure ridges" (ice floes' rough edges, often a few meters high) and "leads" (of open water between those floes). The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted ] to take extensive precautions in navigation during his Antarctic expedition so as to leave no room for doubt concerning his 1911 attainment of the ], which (like ]'s a few weeks later in 1912) was supported by the ], ], and ] observations of several other navigators. See ]. | |||

| The last five marches when Peary was accompanied by a navigator (Capt. Bob Bartlett) averaged no better than {{convert|13|mi|abbr=on}} marching north. But once the last support party turned back at "Camp Bartlett", where Bartlett was ordered southward, at least {{convert|133|nmi|abbr=on}} from the pole, Peary's claimed speeds immediately doubled for the five marches to Camp Jesup. The recorded speeds quadrupled during the two and a half-day return to Camp Bartlett – at which point his speed slowed drastically. Peary's account of a beeline journey to the pole and back—which would have assisted his claim of such speed—is contradicted by his companion Henson's account of tortured detours to avoid "pressure ridges" (ice floes' rough edges, often a few meters high) and "leads" (open water between those floes). | |||

| To specify, Peary claimed to travel (in his official report) a total of 304 nautical miles between April 2, 1909 (when he left Bartlett's last camp) and April 9 (when he returned there), 133 NMs to the pole, 133 NMs back and 38 Nautical miles in the vicinity of the pole. These distances are counted WITHOUT detours due to drift, leads and difficult ice, i.e. the distance travelled must have been significantly higher to make good the distance claimed. Such speeds have only been noted in mythology and are clearly impossible. | |||

| Peary and his party arrived back in Cape Columbia on the morning of April 23, 1909, only about two and a half days after Capt Bartlett, yet Peary claimed he had travelled a minimum of 304 NMs more than Bartlett (to the Pole and vicinity). Such claimed speeds are impossible to understand. | |||

| In his official report, Peary claimed to have traveled a total of 304 nautical miles between April 2, 1909, (when he left Bartlett's last camp) and April 9 (when he returned there), {{convert|133|nmi|abbr=on}} to the pole, the same distance back, and {{convert|38|nmi|abbr=on}} in the vicinity of the pole.{{citation needed|date=November 2016}} These distances are counted without detours due to drift, leads and difficult ice, i.e. the distance traveled must have been significantly higher to make good the distance claimed.{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} Peary and his party arrived back in Cape Columbia on the morning of April 23, 1909, only about two and a half days after Capt Bartlett, yet Peary claimed he had traveled a minimum of {{convert|304|nmi|abbr=on}} more than Bartlett (to the Pole and vicinity).{{citation needed|date=April 2013}} | |||

| ===Supporting evidence=== | |||

| Further evidence supporting Peary's claims has been developed in recent decades. | |||

| The conflicting and unverified claims of Cook and Peary prompted ] to take extensive precautions in navigation during ] so as to leave no room for doubt concerning his 1911 attainment of the ], which—like ]'s a month later in 1912—was supported by the sextant, ], and compass observations of several other navigators. | |||

| ====Diary==== | |||

| ] | |||

| The diary that Robert E. Peary kept on his 1909 polar expedition, largely ignored by historians because it was unavailable, was finally opened to the public in 1986. Historian Larry Schweikart examined it, finding that: the writing was consistent throughout (giving no evidence of post-expedition alteration), that there were consistent pemmican and other stains on all pages, and that all evidence was consistent with a conclusion that Peary's observations were made on the spot he claimed. Further, in a previous article,{{citation}} Schweikart had compared the reports and experiences of Japanese explorer ], who reached the North Pole alone in 1978, to those of Peary and found they were entirely consistent.<ref>Larry Schweikart, "Polar Revisionism and the Peary Claim: The Diary of Robert E. Peary," ''The Historian'', XLVIII, May 1986.</ref> However, there were no entries in the diary itself for the crucial days 6 and 7 April 1909, only several blank pages. His famous words, allegedly written in his diary at the pole, "The Pole at Last!" were written on loose slips of paper, inserted into the diary. | |||

| ==== |

====Review of Peary's diary==== | ||

| ]]] | |||

| In 1989, the National Geographic Society (which had been a major sponsor of Peary's expeditions) concluded, based on two-dimensional photogrammetric analysis of the shadows in photographs and review of ocean depth measures taken by Peary, that he was no more than {{convert|5|mi|km}} away from the pole. But since Peary's original camera (a 1908 #4 Folding Pocket Kodak) has not survived, and such cameras were made with at least six different lenses from various manufacturers, the focal length of the lens—and hence the shadow analysis which is based upon it—must be considered uncertain at best. The National Geographic Society has never released Peary's photos for independent analysis, and scientific specialists have questioned the Society's conclusions.<ref>For example, "Washington Post", December 12, 1989; "Scientific American", March and June, 1990</ref> | |||

| The diary that Robert E. Peary kept on his 1909 polar expedition was finally made available for research in 1986. Historian ] examined it, finding that: the writing was consistent throughout (giving no evidence of post-expedition alteration), there were consistent ] and other stains on all pages, and all evidence was consistent with a conclusion that Peary's observations were made on the spot he claimed. Schweikart compared the reports and experiences of Japanese explorer ], who reached the North Pole alone in 1978, to those of Peary and found they were consistent.<ref>{{Cite journal | url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/24447539 | first=Larry | last=Schweikart | authorlink=Larry Schweikart | title=Polar Revisionism and the Peary Claim: The Diary of Robert E. Peary | journal=The Historian | date=May 1986| volume=48 | issue=3 | pages=341–358 | doi=10.1111/j.1540-6563.1986.tb00698.x | jstor=24447539 }}</ref> However, Peary made no entries in the diary on the crucial days of April 6 and 7, 1909, and his famous words "The Pole at Last!", allegedly written in his diary at the pole, were written on loose slips of paper that were inserted into the diary. | |||

| The National Geographic Society commissioned The to resolve the issue. The Navigation Foundation's full report from December 11, 1989 has been published and is . Gilbert M. Grosvenor (President of the National Geographic Society from 1980 to 1996) is quoted as saying, “I consider this the end of a historic controversy and the | |||

| confirmation of due justice to a great explorer.” | |||

| ====1984 and 1989 National Geographic Society studies==== | |||

| In 1984, the ] (NGS), a major sponsor of Peary's expeditions, commissioned ], an Arctic explorer himself, to write an assessment of Peary's original 1909 diary and astronomical observations. As Herbert researched the material, he came to believe that Peary falsified his records and concluded that he did not reach the North Pole.<ref name=Doubts/> His book, ''The Noose of Laurels'', caused a furor when it was published in 1989. If Peary did not reach the pole in 1909, Herbert would claim the record of being the first to reach the pole on foot.<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/1989/08/13/books/not-quite-on-top-of-the-world.html | title=NOT QUITE ON TOP OF THE WORLD | first=Katherine | last=Bouton | work=] | date=August 13, 1989}}</ref><ref name=Noose/> | |||

| In 1989, the NGS also conducted a two-dimensional photogrammetric analysis of the shadows in photographs and a review of ocean depth measures taken by Peary; its staff concluded that he was no more than {{convert|5|mi|abbr=on|0}} away from the pole. Peary's original camera, a 1908 #4 Folding Pocket ], did not survive. As such cameras were made with at least six different lenses from various manufacturers, the focal length of the lens, and hence the shadow analysis based on it, must be considered uncertain at best. The NGS has never released Peary's photos for an independent analysis. Specialists questioned the conclusions of the NGS. The NGS commissioned the Foundation for the Promotion of the Art of Navigation to resolve the issue, which concluded that Peary had indeed reached the North Pole.<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.nytimes.com/1989/12/12/us/peary-made-it-to-the-pole-after-all-study-concludes.html | title=Peary Made It to the Pole After All, Study Concludes | first=Warren E. | last=Leary | work=] | date=August 13, 1989}}</ref><ref name=First/><ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1991/06/09/pearys-polar-mystery/7655c951-fb71-423d-a6c7-c5b75f9817fe/ | title=PEARY'S POLAR MYSTERY | first=Boyce | last=Rensberger | newspaper=] | date=June 9, 1991}}</ref> | |||

| ====Review of depth soundings==== | ====Review of depth soundings==== | ||

| Supporters of Peary and Henson assert that the depth soundings they made on the outward journey have been matched by recent surveys, and so their claim of having reached the Pole is confirmed.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://matthewhenson.com/northpoleproofDEPTH2.htm | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020603060320/https://matthewhenson.com/northpoleproofDEPTH2.htm | archive-date=June 3, 2002 | title=Proof Henson & Peary reached Pole (1909 Depth Soundings) | date=August 16, 2022 | publisher=]}}{{cbignore}}</ref> Since only the first few of the Peary party's soundings, taken nearest the shore, touched bottom; experts have said their usefulness is limited to showing that he was above deep water. Peary's expedition possessed 4,000 fathoms of sounding line, but he took only 2,000 with him over an ocean already established as being deeper in many regions. Peary stated in 1909 Congressional hearings about the expedition that he made no longitudinal observations during his trip, only latitude observations, yet he maintained he stayed on the "Columbia meridian" all along, and that his soundings were made on this meridian.{{citation needed|date=October 2013}} The pack ice was moving all the time, so he had no way of knowing where he was without longitudinal observations.{{citation needed|date=October 2013}} | |||

| === |

===Re-creation of expedition in 2005=== | ||

| British explorer ] and four companions |

In 2005, British explorer ] and four companions re-created the outward portion of Peary's journey using replica wooden sleds and ] teams. They ensured their sled weights were the same as Peary's sleds throughout their journey. They reached the North Pole in 36 days, 22 hours—nearly five hours faster than Peary. However, Avery's fastest 5-day march was 90 nautical miles (170 km), significantly short of the 135 nautical miles (250 km) claimed by Peary. | ||

| After reaching the Pole, Avery and his team were airlifted off the ice rather than returning by dogsled.<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.countrylife.co.uk/out-and-about/sporting-country-pursuits/interview-tom-avery-polar-explorer-29629 | title=Interview: Tom Avery, polar explorer | work=] | date=April 30, 2009}}</ref> | |||

| Analysis of the actual speeds made by Avery do much more to cast doubt on Peary's claim than to confirm it. While Peary claimed {{convert|130|nmi|km}} made good in his last five marches, horrific ice conditions meant that Avery managed only 71 in his last five marches. Indeed, Avery never exceeded {{convert|90|nmi|km}} made good in any five-day stretch, although he was losing over {{convert|7|mi|km}} a day at this time to the southerly drift of the ice.<ref> ''Barclay's Capital Ultimate North''. Retrieved March 10, 2008.</ref>{{dead link|date=September 2011}} Avery managed to match Peary's overall 37-day total in part because Peary was held up by open water for five days at the Big Lead. But Peary had his own advantages in that his team consisted of 133 dogs and 25 men, meaning he was able to keep his "polar party" fresh for the sprint to the Pole. Peary's team was also more experienced at dog sledding. | |||

| == |

==Legacy== | ||

| ], northwest ]]] | |||

| Peary's exploits and life were portrayed in the 1998 ] '']''. ] played Robert Peary. His associate Matthew Henson was played by ]. The film won a ] and a ] for Lindo's performance as Henson.<ref></ref> | |||

| Several United States Navy ships have been named {{USS|Robert E. Peary}}. The ] at Bowdoin College is named for Peary and fellow Arctic explorer ]. Robert E. Peary Middle School, Gardena,CA. In 1986, the ] issued a 22-cent postage stamp in honor of Peary and Henson;<ref name=postal>{{Cite web | url=https://postalmuseum.si.edu/exhibition/the-black-experience/exploration-matthew-henson | title=Exploration: Matthew Henson | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ], ], ] and ] in Greenland, ] and ] in ], as well as ] in Antarctica, are named in his honor. The lunar crater ], located at the Moon's north pole, is also named after him.<ref>{{Cite web | url=https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/Feature/4627 | title=Planetary Names: Crater, craters: Peary on Moon | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ] in York County, Virginia is named for Admiral Peary. Originally established as a Navy ] training center during World War II, it was repurposed in the 1950s as a ] training facility. It is commonly called "The Farm". | |||

| Admiral Peary Vocational Technical School, located in a neighboring community very close to his birthplace of Cresson, PA, was named for him and was opened in 1972. Today the school educates over 600 students each year in numerous technical education disciplines. | |||

| A section of ] in ], is named the Admiral Peary Highway | |||

| Major General ], leader of the ill-fated ] from 1881 to 1884, noted that no Arctic expert questioned that Peary courageously risked his life traveling hundreds of miles from land, and that he reached regions adjacent to the pole. After initial acceptance of Peary's claim, he later came to doubt Peary's having reached 90°. | |||

| In his book ''Ninety Degrees North'', polar historian Fergus Fleming describes Peary as "undoubtedly the most driven, possibly the most successful and probably the most unpleasant man in the annals of polar exploration".<ref>{{Cite news | url=https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/brexit-news-the-race-to-the-north-pole-6600156/ | title=The race to the North Pole and a controversy that has yet to thaw | first=MICK | last=O'HARE | work=] | date=December 19, 2020}}</ref> | |||

| In 1932, an expedition was made by Robert Bartlett and Marie Ahnighito Peary Stafford, Peary's daughter, on the '']'' to erect a monument to Peary at ].<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.bowdoin.edu/arctic-museum/exhibits/2004/peary-monument.html | title=Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, Exhibition: Building the Peary Monument | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| ==Honors== | |||

| {{more citations needed|section|date=April 2017}} | |||

| Medals | |||

| * American Geographical Society, ] (1896)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://americangeo.org/honors/medals-and-awards/cullum-geographical-medal/ | title=CULLUM GEOGRAPHICAL MEDAL | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| * American Geographical Society, ] (1902)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://americangeo.org/honors/medals-and-awards/charles-p-daly-medal/ | title=CHARLES P. DALY MEDAL | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| * National Geographic Society, ] (1906)<ref>{{cite web | url=https://www.nationalgeographic.org/events/awards/hubbard/ | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210914170715/https://www.nationalgeographic.org/events/awards/hubbard/ | url-status=dead | archive-date=September 14, 2021 | title=HUBBARD MEDAL | publisher=]}}</ref> | |||

| * Royal Geographical Society of London, special great gold medal | |||

| * National Geographic Society of Washington, the special great gold medal | |||

| * ], great gold medal | |||

| * Chicago Geographical Society, Helen Culver medal | |||

| * Imperial German Geographical Society, Nachtigall gold medal | |||

| * Royal Italian Geographical Society, King Humbert gold medal | |||

| * Imperial Austrian Geographical Society | |||

| * Hungarian Geographical Society gold medal | |||

| * Royal Belgian Geographical Society gold medal | |||

| * Royal Geographical Society of Antwerp gold medal | |||

| * ] | |||

| Honorary degrees | |||

| * Bowdoin College – Doctor of laws | |||

| * Edinburgh University – Doctor of laws | |||

| Honorary memberships | |||

| * New York Chamber of Commerce honorary member. | |||

| * Pennsylvania Society Honorary member | |||

| * Manchester Geographical Society Honorary membership | |||

| * Royal Netherlands Geographical Society of Amsterdam Honorary membership<ref>{{cite book | url=https://books.google.com/books?id=g1ugAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA365 | title=The North Pole: its discovery in 1909 under the auspices of the Peary Arctic club | first=Robert Edwin | last=Peary | publisher=] | year=1910}}</ref> | |||

| Other | |||

| * Royal Scottish Geographical Society, special trophy, a replica in silver of the ships used by Hudson, Baffin, and Davis. | |||

| * Grand Officer of the ], awarded 1913<ref>{{Cite journal | url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/2560855 | title=Memoir of Robert Edwin Peary | first=William Herbert | last=Hobbs | journal=Annals of the Association of American Geographers | year=1921 | volume=11 | pages=93–108 | doi=10.1080/00045602109357023 | jstor=2560855 | authorlink=William Herbert Hobbs}}</ref> | |||

| * In Arlington National Cemetery on April 6, 1922, the Admiral Robert Edwin Peary monument was unveiled by his daughter, Mrs. Marie Peary Stafford.<ref>{{cite news | title=Dignitaries of the Nation Brave Rain to Honor Peary | url=https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84026749/1922-04-07/ed-1/seq-15/ | work=] |date=April 7, 1922}}</ref> Numerous government officials, including ] and Former ] ] were in attendance. | |||

| * On May 28, 1986, the ] issued a 22 cent ] in his and Matthew Henson's honor.<ref name=postal/> | |||

| ==Popular culture== | |||

| ] gives a satirical account of the rival claims of Peary and Cook in his Erchie Macpherson story "Erchie Explains the Polar Situation", first published in the '']'' of 4th October 1909.<ref>Munro, Neil, "Erchie Explains the Polar Situation", in Osborne, Brian D. & Armstrong, Ronald (eds.) (2002), ''Erchie, My Droll Friend'', ], Edinburgh, pp. 379 -382, {{isbn|9781841582023}}</ref> | |||

| ==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| {{commons|Robert Edwin Peary}} | |||

| {{wikisource author|Robert Edwin Peary}} | |||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{Reflist}} | |||

| *{{cite book | last=Berton|first=Pierre|authorlink=Pierre Berton|title=The Arctic Grail |publisher=Anchor Canada (originally published 1988)| year=2001 |isbn=0-385-65845-1 | oclc = 46661513 }} | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| | last = Bryce | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Berton | first=Pierre | author-link=Pierre Berton | title=The Arctic Grail | publisher=] | year=2001 | isbn=9780385658454}} | |||

| | first = Robert M. | |||

| * {{cite news | last=Brendle | first=Anna | url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/profile-african-american-north-pole-explorer-matthew-henson | title=Profile: African-American North Pole Explorer Matthew Henson | work=] | date=January 9, 2003}} | |||

| | title = Cook & Peary: the polar controversy, resolved | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Bryce | first=Robert M. | title=Cook & Peary: the polar controversy, resolved | date=1997 | publisher=] | isbn=9780689120343}} | |||

| | month = February | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Coe | first=Brian | title=Kodak Cameras: The First Hundred Years | year=2003 | publisher=Hove Foto Books | isbn=9781874707370}} | |||

| | year = 1997 | |||

| * {{cite web | last=Davies | first=Thomas D. | title=''New Evidence Places Peary at The Pole'' | website=northpole1909.com | url=http://www.northpole1909.com/daviesframesets.htm | url-status=dead | archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20020206210630/http://www.northpole1909.com/daviesframesets.htm | archive-date=February 6, 2002}} | |||

| | publisher = Stackpole Books | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Davies | first=Thomas D. | title=Robert E. Peary at the North Pole | year=2009 | publisher=Starpath Publications | isbn=9780914025207}} | |||

| | location = ] | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Dolan | first=Sean | title=Matthew Henson (Junior World Biographies) | publisher=Chelsea Juniors | date=1992}} | |||

| | isbn = 0-689-12034-6 |lccn=96038215|id= {{LCC|G635.C66|H86|1997}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Fleming | first=Fergus | title=Ninety degrees north: the quest for the North Pole | date=2001 | publisher=] | isbn=9781862074491}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Henderson | first=Bruce | title=True North: Peary, Cook, and the Race to the Pole | publisher=] | year=2005 | isbn=9780393327380}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Herbert | first=Wally | author-link=Wally Herbert | title=The noose of laurels: Robert E. Peary and the race to the North Pole | date=1989 | publisher=] | isbn=9780689120343 | url=https://archive.org/details/isbn_9780689120343 }} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Johnson | first=Dolores | title=Onward: A Photobiography of African-American Polar Explorer Matthew Henson | url=https://archive.org/details/onward00dolo/ | publisher=] | date=2006}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Mills | first=William James | title=Exploring Polar Frontiers: A Historical Encyclopedia | year=2003 | publisher=] | isbn=9781576074220}} | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Nuttall | first=Mark | title=Encyclopedia of the Arctic | year=2012 | publisher=] | isbn=9781579584368 | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| * {{cite book | last=Rawlins | first=Dennis | author-link=Dennis Rawlins | title=Peary at the North Pole: fact or fiction? | year=1973 | publisher=Robert B. Luce | location=Washington | isbn=9780883310427 | url=https://archive.org/details/pearyatnorthpole00denn }} | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Robinson | first=Michael F. | title=The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture | year=2006 | publisher=] | isbn=9780226721842}} | |||

| | last = Coe | |||

| * {{cite book | last=Schweikart | first=Larry | authorlink=Larry Schweikart | title=Polar Revisionism and the Peary Claim: The Diary of Robert E. Peary | date=May 1986}} | |||

| | first = Brian | |||

| | title = Kodak Cameras: The First Hundred Years | |||

| | year = 1988, Rev. 2003 | |||

| | publisher = Hove Foto Books | |||

| | location = East Sussex | |||

| | isbn = 1-874707-37-5 | |||

| }} | |||

| *{{cite book | |||

| | last = Davies | |||

| | first = Thomas D. | |||

| | title = Robert Peary at the North Pole | |||

| | year = 2010 | |||

| | publisher = Starpath Publications, Seattle, WA (originally The Foundation For the Promotion of the Art of Navigation) http://starpath.com/catalog/books/1988.htm | |||

| }} | |||