| Revision as of 22:27, 12 January 2013 view sourceErnio48 (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users13,806 edits →1990-present← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 14:09, 5 January 2025 view source Plastikspork (talk | contribs)Edit filter managers, Administrators259,055 edits Please discuss on talk page first!Tag: Undo | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{short description|People of Germany}} | |||

| {{About|Germans as an ethnic group|other uses|Germans (disambiguation)|the population of Germany|Demographics of Germany|an analysis on the nationality or German citizenship|German nationality law|the term "Germans" as used in a context of antiquity (pre AD 500)|Germanic tribes|Germans outside of Germany|Ethnic Germans}} | |||

| {{About|the people of Germany|other uses|German (disambiguation){{!}}German}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{pp-move |

{{pp-move}} | ||

| {{pp |

{{pp|small=yes}} | ||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=September 2024}} | |||

| {{Infobox ethnic group | |||

| ], seat of the ]]] | |||

| |group = Germans <br /> ''Deutsche'' | |||

| ] during ] in 1989 in front of the ]]] | |||

| |image = | |||

| '''Germans''' ({{Langx|de|Deutsche}}, {{IPA|de|ˈdɔʏtʃə|pron|De-Deutsche.ogg}}) are the natives or inhabitants of ], or sometimes more broadly as a sociolinguistic group of those with German descent or native speakers of the ].<ref name="Merriam-Webster">{{cite web|title=German Definition & Meaning|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/German|url-status=live|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201113075927/https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/German|archive-date=13 November 2020|access-date=25 November 2020|website=Merriam-Webster}}</ref><ref name="OED">{{cite book|date=2010|chapter=German|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=anecAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA733|title=Oxford Dictionary of English|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=anecAQAAQBAJ|publisher=]|page=733|isbn=978-0199571123|access-date=22 December 2020|archive-date=4 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210204224602/https://books.google.com/books?id=anecAQAAQBAJ|url-status=live}}</ref> The ], implemented in 1949 following the end of ], defines a German as a ].<ref>{{cite book|title=Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany|editor-last=Bundesministerium der Justiz und für Verbraucherschutz|editor-link=Federal Ministry of Justice and Consumer Protection|url=https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0728|chapter=Article 116|quote=Unless otherwise provided by a law, a German within the meaning of this Basic Law is a person who possesses German citizenship or who has been admitted to the territory of the German Reich within the boundaries of 31 December 1937 as a refugee or expellee of German ethnic origin or as the spouse or descendant of such person.|access-date=3 June 2021|archive-date=7 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201107162050/https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_gg/englisch_gg.html#p0728|url-status=live}}</ref> During the 19th and much of the 20th century, discussions on German identity were dominated by concepts of a common language, culture, descent, and history.<ref name="Moser_172">{{harvnb|Moser|2011|p=172}}. "German identity developed through a long historical process that led, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, to the definition of the German nation as both a community of descent (]) and shared culture and experience. Today, the German language is the primary though not exclusive criterion of German identity."</ref> Today, the German language is widely seen as the primary, though not exclusive, criterion of German identity.<ref>{{harvnb|Haarmann|2015|p=313}}. "After centuries of political fragmentation, a sense of national unity as Germans began to evolve in the eighteenth century, and the German language became a key marker of national identity."</ref> Estimates on the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 to 150 million, most of whom live in Germany.<ref name="Moser_171">{{harvnb|Moser|2011|p=171}}. "The Germans live in Central Europe, mostly in Germany... Estimates of the total number of Germans in the world range from 100 million to 150 million, depending on how German is defined, but it is probably more appropriate to accept the lower figure."</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| |caption= <small>{{allow wrap|{{flatlist| | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| The history of Germans as an ] began with the separation of a distinct ] from the ] of the ] under the ] in the 10th century, forming the core of the ]. In subsequent centuries the political power and population of this empire grew considerably. It expanded eastwards, and eventually a substantial number of Germans migrated further eastwards into ]. The empire itself was politically divided between many small princedoms, cities and bishoprics. Following the ] in the 16th century, many of these states found themselves in bitter conflict concerning the rise of ]. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| In the 19th century, the Holy Roman Empire dissolved, and ] began to grow. At the same time however, the concept of German nationality became more complex. The multiethnic ] ] most Germans into its ] in 1871, and a substantial additional number of Germans were in the multiethnic kingdom of ]. During this time, a large number of Germans also emigrated to the ], particularly to the ], especially to present-day ]. Large numbers also emigrated to ] and ], and they established sizable communities in ] and ]. The ] also included a substantial German population. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Following the end of ], Austria-Hungary and the German Empire were partitioned, resulting in many Germans becoming ] in newly established countries. In the chaotic years that followed, ] became the dictator of ] and embarked on a genocidal campaign to unify all Germans under his leadership. His Nazi movement defined Germans in a very specific way which included ], ], eastern ], and so-called {{lang|de|]}}, who were ethnic Germans elsewhere in Europe and globally. However, this Nazi conception expressly excluded German citizens of ] or ] background. Nazi policies of military aggression and its persecution of those deemed non-Germans in ] led to ] in which the Nazi regime was defeated by ], led by the ], the ], and the former ]. In the aftermath of Germany's defeat in the war, the country was occupied and once again partitioned. Millions of Germans were ] from Central and Eastern Europe. In 1990, ] and ] were ]. In modern times, remembrance of the Holocaust, known as {{lang|de|]}} ("culture of remembrance"), has become an integral part of German identity. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| Owing to their long history of political fragmentation, Germans are culturally diverse and often have strong regional identities. Arts and sciences are an integral part of ], and the Germans have been represented by many prominent personalities in a significant number of disciplines, including ] where Germany is ranked ] among countries of the world in the number of total recipients. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Names== | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Further|List of terms used for Germans|Names of Germany}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| The English term '']'' is derived from the ] '']'', which was used for ] in ancient times.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=313}}<ref>{{cite book|last1=Hoad|first1=T. F.|date=2003|chapter=German|chapter-url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001/acref-9780192830982-e-6407|title=The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology|publisher=]|doi=10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001|isbn=9780192830982|access-date=22 December 2020|archive-date=24 September 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210924162222/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780192830982.001.0001/acref-9780192830982-e-6407|url-status=live}}</ref> Since the early modern period, it has been the most common name for the Germans in English, being applied to any citizens, natives or inhabitants of Germany, regardless of whether they are considered to have German ethnicity. | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| }}}}</small> | |||

| |population = German diaspora: '''circa 150 million''' (roughly 2.1% of the ])<ref>. 156 is the estimate which counts all people claiming ethnic German ancestry in the U.S., Brazil, Argentina, and elsewhere.</ref><ref>"Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia" by Jeffrey Cole (2011), page 171.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://histclo.com/country/ger/reg/pop/gr-pop.html |title=Report on German population |publisher=Histclo.com |date=2010-02-04 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref> | |||

| |regions = {{flagcountry|Germany}} {{nbsp|6}} 66 million<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.destatis.de/DE/Publikationen/Thematisch/Bevoelkerung/MigrationIntegration/Migrationshintergrund2010220107004.pdf?__blob=publicationFile |page=64|title=Detailed estimates |date= |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.destatis.de/DE/PresseService/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2010/01/PD10_033_122.html |title=Slightly higher proportion of people with a migration background |language={{de icon}} |publisher=Destatis.de |date=2010-01-26 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.destatis.de/EN/PressServices/Press/pr/2010/07/PE10_248_122.html |title=Press releases - For the first time more than 16 million people with migration background in Germany |publisher=Federal Statistical Office (Destatis) |date=2010-07-14 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.destatis.de/DE/PresseService/Presse/Pressemitteilungen/2011/09/PD11_355_122.html |title=Pressemitteilungen - Ein Fünftel der Bevölkerung in Deutschland hatte 2010 einen Migrationshintergrund - Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis) |language={{de icon}} |publisher=Destatis.de |date=2011-09-26 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref><ref name="2005 Microcensus">66.42 million is the number of Germans without immigrant background, 75 million is the number of German citizens </ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.dw-world.de/dw/article/0,2144,2046121,00.html |title=Deutsche Welle: 2005 German Census figures |publisher=Dw-world.de |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| |region1 = ]; see also ]. | |||

| |langs=German: ] (], ]), ] (see ]) | |||

| |rels=], ] (chiefly ]) | |||

| |related= ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ],<ref name="hpgl.stanford.edu"/> ], ],<ref name="hpgl.stanford.edu">http://hpgl.stanford.edu/publications/EJHG_2002_v10_521-529.pdf</ref> and other ] | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Germans''' ({{lang-de|Deutsche}}) are a ] ] native to ]. The English term ''Germans'' has referred to the ] population of the ] since the ].<ref>alongside the slightly earlier term ''Almayns''; ]'s 1387 translation of ]'s ''Polychronicon'' has: ''{{lang|enm|Þe empere passede from þe Grees to þe Frenschemen and to þe Germans, þat beeþ Almayns.}}'' During the 15th and 16th centuries, ''Dutch'' was the adjective used in the sense "pertaining to Germans". Use of ''German'' as an adjective dates to ca. 1550. The adjective ''Dutch'' narrowed its sense to "of the Netherlands" during the 17th century.</ref> Legally, Germans are citizens of the ]. | |||

| In some contexts, people of German descent are also called Germans.<ref name="OED"/><ref name="Merriam-Webster"/> In historical discussions the term "Germans" is also occasionally used to refer to the Germanic peoples during the time of the ].<ref name="Merriam-Webster"/><ref name="Columbia">{{cite web|url=https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Germans|title=Germans|year=2013|website=]|publisher=]|access-date=5 December 2020|archive-date=30 November 2020|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201130100500/https://encyclopedia2.thefreedictionary.com/Germans|url-status=live}}</ref><ref name="Drinkwater">{{cite book|last1=Drinkwater|first1=John Frederick|author-link1=John Frederick Drinkwater|date=2012|chapter=Germans|chapter-url=https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001/acref-9780199545568-e-2831|editor1-last=Hornblower|editor1-first=Simon|editor1-link=Simon Hornblower|editor2-last=Spawforth|editor2-first=Antony|editor3-last=Eidinow|editor3-first=Esther|editor3-link=Esther Eidinow|title=]|edition=4|publisher=]|page=613|doi=10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001|isbn=9780191735257|access-date=22 December 2020|archive-date=9 June 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210609021237/https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199545568.001.0001/acref-9780199545568-e-2831|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| Of approximately 100 million native speakers of German in the world, about 66–75 million consider themselves Germans. There are an additional 80 million people of German ancestry mainly in the ], ] (almost totally in the country's ]), ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ] (who most likely are not native speakers of German).<ref>{{es}} </ref> Thus, the total number of Germans worldwide lies between 66 and 160 million, depending on the criteria applied (native speakers, single-ancestry ethnic Germans, partial German ancestry, etc.). | |||

| The German ] '']'' is derived from the ] term '']'', which means "ethnic" or "relating to the people". This term was used for speakers of West-Germanic languages in Central Europe since at least the 8th century, after which time a distinct German ethnic identity began to emerge among at least some them living within the Holy Roman Empire.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=313}} However, variants of the same term were also used in the ], for the related dialects of what is still called ] in English, which is now a national language of the ] and ]. | |||

| Today, peoples from countries with a German-speaking majority or significant German-speaking population groups other than Germany, such as ], ], ] and ], have developed their own national identity, and since the end of ], have not referred to themselves as "Germans" in a modern context. | |||

| ==Name== | |||

| {{further|Names of Germany}} | |||

| ] and ] in the early 2nd century.]] | |||

| The German term '']'' originates from the ] word '']'' (from ''diot'' "people"), referring to the ] "language of the people". It is not clear how commonly, if at all, the word was used as an ethnonym in Old High German. | |||

| Used as a noun, ''ein diutscher'' in the sense of "a German" emerges in ], attested from the second half of the 12th century.<ref> | |||

| e.g. ]. See ], ''Mittelhochdeutsches Handwörterbuch'' (1872–1878), s.v. "Diutsche". | |||

| The Middle High German ] (ca. 1170) has ''in diutisker erde'' (65.6) for "in the German realm, in Germany". | |||

| The phrase ''in tütschem land'', whence the modern '']'', is attested in the late 15th century (e.g. ], ], see Grimm, '']'', s.v. "Deutsch").</ref> | |||

| The ] term ''alemans'' is taken from the name of the ]. It was loaned into ] as ''almains'' in the early 14th century. The word ''dutch'' is attested in English from the 14th century, denoting continental West Germanic ("Dutch" and "German") dialects and their speakers.<ref>''OED'', s.v. "Dutch, adj., n., and adv."</ref> | |||

| While in most the Romance languages the Germans have been named from the ]ns or Alamanni (some, like standard Italian, retain an older borrowing of the ]), the ], Finnish and Estonian names of the Germans was taken from that of the ]. In ], the Germans were given the name of ''{{lang|sla|němьci}} '' (singular ''{{lang|sla|němьcь}}''), originally with a meaning "foreigner, one who does not speak ". | |||

| The English term ''Germans'' is only attested from the mid-16th century, based on the classical Latin term ''Germani'' used by ] and later ]. It gradually replaced ''Dutch'' and ''Almains'', the latter becoming mostly obsolete by the early 18th century.<ref>{{cite book |last= Schulze |first=Hagen |authorlink=Hagen Schulze |title=Germany: A New History |publisher=Harvard University Press |page=4 |year=1998 |isbn= 0-674-80688-3}}</ref><ref>, ''The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Etymology''. Ed. T. F. Hoad. ]: ], 1996. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 4 March 2008.</ref> | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| {{ |

{{See also|History of Germany}} | ||

| ] of ], situated between the ] and ] rivers, a region which the early ] attempted to conquer and control]] | |||

| The Germans are a Germanic people, which as an ethnicity emerged during the Middle Ages.{{Citation needed|date=October 2011}} From the multi-ethnic ], the ] (1648) left a core territory that was to become Germany. | |||

| ===Ancient history=== | |||

| ] | |||

| {{See also|Germania Antiqua|Limes Germanicus|Germanic peoples|Germania}} | |||

| ] in 972 (red line) and 1035 (red dots) with the ], including ], marked in blue]] | |||

| The first information about the peoples living in what is now Germany was provided by the Roman general and dictator ], who gave an account of his conquest of neighbouring ] in the 1st century BC. Gaul included parts of what is now Germany, west of the ] river. He specifically noted the potential future threat which could come from the related ] (''Germani'') east of the river. Archaeological evidence shows that at the time of Caesar's invasion, both Gaul and Germanic regions had long been strongly influenced by the ] ] ].<ref name="Heather"/> However, the ] associated with later Germanic peoples were approaching the Rhine area since at least the 2nd century BC.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=288–289}} The resulting demographic situation reported by Caesar was that migrating Celts and Germanic peoples were moving into areas which threatened the Alpine regions and the Romans.<ref name="Heather"/> | |||

| The modern German language is a descendant of the Germanic languages which spread during the Iron Age and Roman era. Scholars generally agree that it is possible to speak of Germanic languages existing as early as 500 BCE.{{sfn|Steuer|2021|p=32}} These Germanic languages are believed to have dispersed towards the Rhine from the direction of the ], which was itself a Celtic influenced culture that existed in the ], in the region near the Elbe river. It is likely that ], which defines the Germanic language family, occurred during this period.{{sfn|Steuer|2021|p=89, 1310}} The earlier ] of southern Scandinavia also shows definite population and material continuities with the Jastorf Culture,{{sfn|Timpe|Scardigli|2010|p=636}} but it is unclear whether these indicate ethnic continuity.{{sfn|Todd|1999|p=11}} | |||

| The area of modern-day Germany in the ] was divided into the (]) ] in ] and the (]) ] in ]. | |||

| Under Caesar's successors, the Romans began to conquer and control the entire region between the Rhine and the Elbe which centuries later constituted the largest part of medieval Germany. These efforts were significantly hampered by the victory of a local alliance led by ] at the ] in 9 AD, which is considered a defining moment in German history. While the Romans were nevertheless victorious, rather than installing a Roman administration they controlled the region indirectly for centuries, recruiting soldiers there, and playing the tribes off against each other.<ref name="Heather"/>{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=172}} The early Germanic peoples were later famously described in more detail in '']'' by the 1st century Roman historian ]. He described them as a diverse group, dominating a much larger area than Germany, stretching to the ] in the east, and ] in the north. | |||

| The Germanic peoples during the ] came into contact with other peoples; in the case of the populations settling in the territory of modern Germany, they encountered ] to the south, and ] and ] towards the east. | |||

| ===Medieval history=== | |||

| The '']'' was breached in AD 260. Migrating Germanic tribes commingled with the local ] populations in what is now ] and ]. | |||

| ], also known as the German eastward settlement. The left map shows the situation in roughly 895 AD; the right map shows it about 1400 AD. Germanic peoples (left map) and Germans (right map) are shown in light red.]] | |||

| The migration-period peoples who would coalesce into a "German" ethnicity were the ], ], ], ] and ]. By the 800s, the territory of modern Germany had been united under the rule of ]. Much of what is now ] became Slavonic-speaking (] and ]), after these areas were vacated by Germanic tribes (], ], ] and ] amongst others) which had migrated into the former areas of the ]. | |||

| ] after the ], 1648]] | |||

| German ethnicity began to emerge in medieval times among the descendants of those ] who had lived under heavy Roman influence between the Rhine and Elbe rivers. This included ], ], ], ], ] and ] - all of whom spoke related dialects of ].<ref name="Heather">{{cite web|url=https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/History#ref58082|title=Germany: Ancient History|last=Heather|first=Peter|author-link=Peter Heather|website=]|publisher=]|access-date=21 November 2020|quote=Within the boundaries of present-day Germany... Germanic peoples such as the eastern Franks, Frisians, Saxons, Thuringians, Alemanni, and Bavarians—all speaking West Germanic dialects—had merged Germanic and borrowed Roman cultural features. It was among these groups that a German language and ethnic identity would gradually develop during the Middle Ages.|archive-date=31 March 2019|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190331232159/https://www.britannica.com/place/Germany/History#ref58082|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| These peoples had come under the dominance of the western Franks starting with ], who established control of the Romanized and Frankish population of Gaul in the 5th century, and began a process of conquering the peoples east of the Rhine. The regions long continued to be divided into "]", corresponding to the old ethnic designations.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=288–289}} By the early 9th century AD, large parts of Europe were united under the rule of the Frankish leader ], who expanded the ] in several directions including east of the Rhine, consolidating power over the ] and ], and establishing the ]. Charlemagne was crowned emperor by ] in 800.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=288–289}} | |||

| In the generations after Charlemagne the empire was partitioned at the ] (843), eventually resulting in the long-term separation between the states of ], ] and ]. Beginning with ], non-Frankish dynasties also ruled the eastern kingdom, and under his son ], East Francia, which was mostly German, constituted the core of the ].{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|pp=313–314}} Also under control of this loosely controlled empire were the previously independent kingdoms of ], ], and ]. The latter was a Roman and Frankish area which contained some of the oldest and most important old German cities including ], ] and ], all west of the Rhine, and it became another Duchy within the eastern kingdom. Leaders of the stem duchies which constituted this eastern kingdom — Lotharingia, ], ], ], ], and ] ― initially wielded considerable power independently of the king.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=288–289}} German kings were elected by members of the noble families, who often sought to have weak kings elected in order to preserve their own independence. This prevented an early unification of the Germans.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=314}}{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=289–290}} | |||

| ===Medieval period=== | |||

| {{Main|Ostsiedlung|History of German settlement in Eastern Europe}} | |||

| {{Further|Kingdom of Germany|Stem duchy|Medieval demography|Holy Roman Empire}} | |||

| ] around AD 1000. The sphere of German influence ('']'') is marked in blue.]] | |||

| A warrior nobility dominated the ] German society of the Middle Ages, while most of the German population consisted of peasants with few political rights.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=288–289}} The church played an important role among Germans in the Middle Ages, and competed with the nobility for power.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=173}} Between the 11th and 13th centuries, Germans actively participated in five ] to "liberate" the ].{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=173}} From the beginnings of the kingdom, its dynasties also participated in a push eastwards into Slavic-speaking regions. At the ] in the north, the ] east of the Elbe were conquered over generations of often brutal conflict. Under the later control of powerful German dynasties it became an important region within modern Germany, and home to its modern capital, Berlin. German population also moved eastwards from the 11th century, in what is known as the ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=289–290}} Over time, Slavic and German-speaking populations assimilated, meaning that many modern Germans have substantial Slavic ancestry.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|pp=313–314}} From the 12th century, many Germans settled as merchants and craftsmen in the ], where they came to constitute a significant proportion of the population in many urban centers such as ].{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|pp=313–314}} During the 13th century, the ] began conquering the ], and established what would eventually become the powerful German state of ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=289–290}} | |||

| A German ethnicity emerged in the course of the ], ultimately as a result of the formation of the ] within ] and later the ], beginning in the 9th century. The process was gradual and lacked any clear definition, and the use of exonyms designating "the Germans" develops only during the ]. The title of ''rex teutonicum'' "]" is first used in the late 11th century, by the chancery of ]. Natively, the term ''ein diutscher'' "a German" is used of the people of Germany from the 12th century. | |||

| Further south, ] and ] developed as kingdoms with their own non-German speaking elites. The ] on the ] stopped expanding eastwards towards Hungary in the 11th century. Under ], Bohemia (corresponding roughly to modern Czechia) became a kingdom within the empire, and even managed to take control of Austria, which was German-speaking. However, the late 13th century saw the election of ] of the ] to the imperial throne, and he was able to acquire Austria for his own family. The Habsburgs would continue to play an important role in European history for centuries afterwards. Under the leadership of the Habsburgs the Holy Roman Empire itself remained weak, and by the late Middle Ages much of Lotharingia and Burgundy had come under the control of French dynasts, the ] and ]. Step by step, Italy, Switzerland, ], and ] were no longer subject to effective imperial control. | |||

| After ], the Roman Catholic Church and local rulers led German expansion and settlement in areas inhabited by Slavs and Balts (]). Massive German settlement led to their assimilation of Baltic (]) and Slavic (]) populations, who were exhausted by previous warfare. At the same time, naval innovations led to a German domination of trade in the ] and parts of Eastern Europe through the ]. Along the trade routes, Hanseatic trade stations became centers of German culture. ] ''(Stadtrecht)'' was promoted by the presence of large, relatively wealthy German populations and their influence on political power. | |||

| Thus people who would be considered "Germans", with a common culture, language, and ] different from that of the surrounding rural peoples, colonized trading towns as far north of present-day Germany as ] (in ]), ] (in ]), and ] (now in Russia). The Hanseatic League was not exclusively German in any ethnic sense: many towns who joined the league were outside the Holy Roman Empire and a number of them may only loosely be characterized as ''German''. The Empire was not entirely German either. | |||

| Trade increased and there was a specialization of the arts and crafts.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=173}} In the late Middle Ages the German economy grew under the influence of urban centers, which increased in size and wealth and formed powerful leagues, such as the ] and the ], in order to protect their interests, often through supporting the German kings in their struggles with the nobility.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=289–290}} These urban leagues significantly contributed to the development of German commerce and banking. German merchants of Hanseatic cities settled in cities throughout Northern Europe beyond the German lands.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|p=290}} | |||

| ===Early Modern period=== | |||

| ] after the ], 1648]] | |||

| ===Modern history=== | |||

| From the late 15th century, the Holy Roman Empire came to be known as the ], even though it was not exclusively German, and notably included sizeable ] minorities. | |||

| ] in red, ] in blue, ] in yellow, and other member states in grey. Large parts of ] and some parts of ] did not belong to the German Confederation.]] | |||

| The ], a series of conflicts fought mainly in the territory of modern Germany, weakened the coherence of the Holy Roman Empire, leading to the '']'' in ]. | |||

| ] in a mass grave at ]]] | |||

| ] from ] in 1948]] | |||

| The Habsburg dynasty managed to maintain their grip upon the imperial throne in the ]. While the empire itself continued to be largely de-centralized, the Habsburgs own personal power increased outside of the core German lands. ] personally inherited control of the kingdoms of Hungary and Bohemia, the wealthy low countries (roughly modern Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands), the Kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, Sicily, Naples, and Sardinia, and the Dukedom of Milan. Of these, the Bohemian and Hungarian titles remained connected to the imperial throne for centuries, making Austria a powerful multilingual empire in its own right. On the other hand, the ] went to the Spanish crown and continued to evolve separately from Germany. | |||

| The introduction of printing by the German inventor ] contributed to the formation of a new understanding of faith and reason. At this time, the German monk ] pushed for reforms within the Catholic Church. Luther's efforts culminated in the ].{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=173}} | |||

| The ] were the cause of the final dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, and ultimately the cause for the quest for a German ] in 19th-century German nationalism. After the ], ] and ] emerged as two competitors. Austria, trying to remain the dominant power in Central Europe, led the way in the terms of the Congress of Vienna. The Congress of Vienna was essentially conservative, assuring that little would change in Europe and preventing Germany from uniting.{{Citation needed|date=January 2009}} These terms came to a sudden halt following the ] and the ] in 1856, paving the way for ] in the 1860s. | |||

| Religious schism was a leading cause of the ], a conflict that tore apart the Holy Roman Empire and its neighbours, leading to the death of millions of Germans. The terms of the ] (1648) ending the war, included a major reduction in the central authority of the Holy Roman Emperor.{{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=173–174}} Among the most powerful German states to emerge in the aftermath was Protestant ], under the rule of the ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=290–291}} Charles V and his Habsburg dynasty defended Roman Catholicism. | |||

| ] in the ] of the ]. ] appears in white. The Grand Duke of Baden stands beside Wilhelm, leading the cheers. Crown Prince Friedrich, later ], stands on his father's right.]] | |||

| In the 18th century, German culture was significantly influenced by the ].{{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=173–174}} | |||

| In 1866, the ] finally came to an end. There were several reasons behind this war. As ] grew strongly inside the ] and neither could decide on how Germany was going to be ] into a nation-state. The Austrians favoured the Greater Germany unification but were not willing to give up any of the German-speaking land inside of the ] and take second place to Prussia. The Prussians however wanted to unify Germany as Little Germany primarily by the ] whilst excluding Austria. In the final battle of the German war ('']'') the Prussians successfully defeated the Austrians and succeeded in creating the ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.onwar.com/aced/data/sierra/sevenweeks1866.htm |title=Austria-Hungary Prussia War 1866 |publisher=Onwar.com |date=16 December 2000 |accessdate=2 August 2012}}</ref> | |||

| After centuries of political fragmentation, a sense of German unity began to emerge in the 18th century.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=313}} The Holy Roman Empire continued to decline until being ] altogether by ] in 1806. In central Europe, the Napoleonic wars ushered in great social, political and economic changes, and catalyzed a ] among the Germans. By the late 18th century, German intellectuals such as ] articulated the concept of a German identity rooted in language, and this notion helped spark the ] movement, which sought to unify the Germans into a single ].{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=314}} Eventually, shared ancestry, culture and language (though not religion) came to define German nationalism.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=172}} The ] ended with the ] (1815), and left most of the German states loosely united under the ]. The confederation came to be dominated by the Catholic ], to the dismay of many German nationalists, who saw the German Confederation as an inadequate answer to the ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=290–291}} | |||

| In 1870, after France attacked Prussia, Prussia and its new allies in Southern Germany (among them Bavaria) were victorious in the ]. It created the ] in 1871 as a German ], effectively excluding the multi-ethnic Austrian ] and ]. Integrating the Austrians nevertheless remained a strong desire for many people of Germany and Austria, especially among the liberals, the social democrats and also the Catholics who were a minority in Germany. | |||

| Throughout the 19th century, Prussia continued to grow in power.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=174}} ], German revolutionaries set up the temporary ], but failed in their aim of forming a united German homeland. The Prussians proposed an ] of the German states, but this effort was torpedoed by the Austrians through the ] (1850), recreating the German Confederation. In response, Prussia sought to use the ] customs union to increase its power among the German states.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=290–291}} Under the leadership of ], Prussia expanded its sphere of influence and together with its German allies defeated ] in the ] and soon after ] in the ], subsequently establishing the ]. In 1871, the Prussian coalition decisively defeated the ] in the ], annexing the German speaking region of ]. After taking Paris, Prussia and their allies ] the formation of a united ].{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=314}} | |||

| During the 19th century in the German territories, rapid population growth due to lower death rates, combined with poverty, spurred millions of Germans to emigrate, chiefly to the United States. Today, roughly 17% of the United States' population (23% of the ] population) is of mainly German ancestry.<ref name="US Census Bureau, German ancestry">{{cite web |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ADPTable?_bm=y&-geo_id=01000US&-ds_name=ACS_2006_EST_G00_&-_lang=en&-_caller=geoselect&-format= |title=US Census Factfinder}}</ref> | |||

| In the years following unification, German society was radically changed by numerous processes, including industrialization, rationalization, secularization and the rise of capitalism.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=174}} German power increased considerably and numerous overseas colonies were established.{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=291–292}} During this time, the German population grew considerably, and many emigrated to other countries (mainly North America), contributing to the growth of the ]. Competition for colonies between the Great Powers contributed to the outbreak of ], in which the German, Austro-Hungarian and ]s formed the ], an alliance that was ultimately defeated, with none of the empires comprising it surviving the aftermath of the war. Under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles, the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires were both dissolved and partitioned, resulting in millions of Germans becoming ethnic minorities in other countries.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|pp=314–315}} The monarchical rulers of the German states, including the German emperor ], were overthrown in the ] which led to the establishment of the ]. The Germans of the ] side of the ] proclaimed the ], and sought to be incorporated into the German state, but this was forbidden by the ] and ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|pp=291–292}} | |||

| ===Twentieth century=== | |||

| {{Further|Volksdeutsche|Reichsdeutsche}} | |||

| ] in 1891. Germany based in the northeast, dominates in size, occupying about 40% of the new empire.|The ] of 1871–1918. By excluding the German-speaking part of the multinational ], this geographic construction represented a '']'' solution.]] | |||

| What many Germans saw as the "humiliation of Versailles",{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=316}} continuing traditions of authoritarian and ] ideologies,{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=174}} and the ] all contributed to the rise of Austrian-born ] and the Nazis, who after coming to power democratically in the early 1930s, abolished the Weimar Republic and formed the totalitarian ]. In his quest to subjugate Europe, six million ] were murdered in ]. WWII resulted in widespread destruction and the deaths of tens of millions of soldiers and civilians, while the German state was partitioned. About 12 million Germans ] from Eastern Europe.<ref>{{cite journal|last=Troebst|first=Stefan|title=The Discourse on Forced Migration and European Culture of Remembrance|journal=The Hungarian Historical Review|volume=1|number=3/4|year=2012|pages=397–414|jstor=42568610}}</ref> Significant damage was also done to the German reputation and identity,{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|pp=314–315}} which became far less nationalistic than it previously was.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=316}} | |||

| The dissolution of the ] after World War I led to a strong desire of the population of the new ] to be integrated into ] or Switzerland.<ref>{{cite web|author=Ihre Meinung |url=http://www.vol.at/news/vorarlberg/artikel/als-vorarlberg-schweizer-kanton-werden-wollte/cn/news-20081023-08253040 |title=Als Vorarlberg Schweizer Kanton werden wollte – Vorarlberg – Aktuelle Nachrichten – Vorarlberg Online |publisher=Vol.at |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> This was, however, prevented by the ]. | |||

| The German states of ] and ] became focal points of the ], but were ] in 1990. Although there were fears that the reunified Germany might resume nationalist politics, the country is today widely regarded as a "stablizing actor in the heart of Europe" and a "promoter of democratic integration".{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=316}} | |||

| The ], led by ], attempted to unite all the people they claimed were "Germans" ('']'') into one realm, including ethnic Germans in eastern Europe,<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.deepdyve.com/lp/sage/the-nazi-concept-of-volksdeutsche-and-the-exacerbation-of-anti-AM60h08D5M |title=The Nazi Concept of 'Volksdeutsche' and the Exacerbation of Anti-Semitism in Eastern Europe, 1939-45 |publisher=DeepDyve |date=1 January 1994 |accessdate=2 August 2012}}</ref> many of whom had emigrated more than one hundred fifty years before and developed separate cultures in their new lands. This idea was initially welcomed by many ethnic Germans in ], Austria,<ref>Willian L. Shirer (1984). Twentieth Century Journey, Volume 2, The Nightmare Years: 1930-1940. Boston, U.S.A.: Little, Brown & Company. ISBN 0-316-78703-5 (v. 2).</ref> ], ] and western ], particularly the Germans from ]. The ] resisted the idea. They had viewed themselves as a distinctly separate nation since the ] of 1648. | |||

| After World War II, eastern European nations, including areas annexed by the ] and ], expelled Germans from their territories, including ], Hungary, ] and ]. Between 12 and 16,5 million ] were expelled westwards to occupied Germany. | |||

| After World War II, ] increasingly saw themselves as a separate nation from the German nation. Recent polls show that no more than 6% of the German-speaking Austrians consider themselves as "''Germans''".<ref>{{dead link|date=January 2013}}. Development of the Austrian identity</ref> An Austrian identity was vastly emphasized along with the "]."<ref>Peter Utgaard, ''Remembering and Forgetting Nazism'', (New York: Berghahn Books, 2003), 188–189. Frederick C. Engelmann, "The Austro-German Relationship: One Language, One and One-Half Histories, Two States", ''Unequal Partners'', ed. Harald von Riekhoff and Hanspeter Neuhold (San Francisco: Westview Press, 1993), 53–54.</ref> Today over 80 percent of the Austrians see themselves as an independent nation.<ref>{{cite web|author=Redaktion |url=http://derstandard.at/?url=/?id=3261105 |title=Österreicher fühlen sich heute als Nation – 1938 – derStandard.at " Wissenschaft |publisher=Derstandard.at |date=13 March 2008 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| ===1945 to present=== | |||

| ]]] | |||

| Between 1950 and 1987, about 1.4 million ] and their dependants, mostly from ] and ], arrived in Germany under special provisions of ]. With the collapse of the ] since 1987, 3 million "Aussiedler" – ethnic Germans, mainly from Eastern Europe and the former ] – took advantage of Germany's law of return to leave the ''"land of their birth"'' for Germany.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.migrationinformation.org/Feature/display.cfm?ID=201 |title=Fewer Ethnic Germans Immigrating to Ancestral Homeland |publisher=Migrationinformation.org |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| Approximately 2 million, just from the territories of the former Soviet Union, have resettled in Germany since the late 1980s.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.egms.de/en/meetings/gmds2005/05gmds163.shtml |title=External causes of death in a cohort of Aussiedler from the former Soviet Union, 1990–2002 |publisher=Egms.de |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> On the other hand, significant numbers of ethnic Germans have moved from Germany to other European countries, especially ], the ], Britain, Spain and ]. | |||

| Since 1990 Germany has become home to Europe's third-largest ] population. In 2004, twice as many Jews from former ] republics settled in Germany as in ], bringing the total inflow to more than 200,000 since 1991. Some Jews from the former Soviet Union are of mixed heritage. | |||

| In its ''State of World Population 2006'' report, the United Nations Population Fund lists Germany with hosting the third-highest percentage of the main international migrants worldwide, about 5% or 10 million of all 191 million migrants.<ref>United Nations Population Fund: </ref> | |||

| ==Ethnicity== | |||

| {{Main|Ethnic Germans}} | |||

| The German ethnicity is linked to the Germanic tribes of antiquity in central Europe.<ref name="Its Peoples 2009. Pp. 311">World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish, 2009. Pp. 311.</ref> The early Germans originated on the North German Plain as well as southern Scandinavia.<ref name="Its Peoples 2009. Pp. 311"/> By the 2nd century BC, the number of Germans was significantly increasing and they began expanding into eastern Europe and southward into Celtic territory.<ref name="Its Peoples 2009. Pp. 311"/> During antiquity these Germanic tribes remained separate from each other and did not have writing systems at this time.<ref name="Yehuda Cohen 2010. Pp. 27">Yehuda Cohen. The Germans: Absent Nationality and the Holocaust. SUSSEX ACADEMIC PRESS, 2010. Pp. 27.</ref> By 55 BC, the Germans had reached the Danube river and had either assimilated or otherwise driven out the Celts who had lived there, and had spread west into what is now Belgium and France.<ref name="Yehuda Cohen 2010. Pp. 27"/> | |||

| Conflict between the Germanic tribes and the forces of ] under ] forced major Germanic tribes to retreat to the east bank of the ].<ref name="Its Peoples 2009. Pp. 311-312">World and Its Peoples. Marshall Cavendish, 2009. Pp. 311-312.</ref> Roman emperor ] in 12 BC ordered the conquest of the Germans, but the catastrophic Roman defeat at the ] resulted in the ] abandoning its plans to completely conquer Germany.<ref name="Its Peoples 2009. Pp. 311"/> Germanic peoples in Roman territory were culturally Romanized, and although much of Germany remained free of direct Roman rule, Rome deeply influenced the development of German society, especially the adoption of Christianity by the Germans who obtained it from the Romans.<ref name="Its Peoples 2009. Pp. 311-312"/> In Roman-held territories with Germanic populations, the Germanic and Roman peoples intermarried, and Roman, Germanic, and Christian traditions intermingled.<ref>Marvin Perry, Myrna Chase, Margaret Jacob, James R. Jacob, Theodore H. Von Laue. ''Western Civilization: Ideas, Politics, and Society, Volume I: To 1789''. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 2009. Pp. 212.</ref> The adoption of Christianity would later become a major influence in the development of a common German identity.<ref name="Yehuda Cohen 2010. Pp. 27"/> The first major public figure to speak of a German people in general, was the Roman figure ] in his work ''Germania'' around 100 AD.<ref name="Jeffrey E. Cole 2011. Pp. 172">Jeffrey E. Cole. Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California, USA: ABC-CLIO, 2011. Pp. 172.</ref> However an actual united German identity and ethnicity did not exist then, and it would take centuries of development of German culture until the concept of a German ethnicity began to become a popular identity.{{sfn|Motyl|2001|pp=189}} | |||

| The arrival of the ] in Europe resulted in Hun conquest of large parts of Eastern Europe, the Huns initially were allies of the Roman Empire who fought against Germanic tribes, but later the Huns cooperated with the Germanic tribe of the Ostrogoths, and large numbers of Germans lived within the lands of the ] of ].<ref name="Ostrogoths Pp. 46">A History of the Ostrogoths. Pp. 46.</ref> Attila had both Hunnic and Germanic families and prominent Germanic chiefs amongst his close entourage in Europe.<ref name="Ostrogoths Pp. 46"/> The Huns living in Germanic territories in Eastern Europe adopted an ] as their '']''.<ref>Sinor, Denis. 1990. The Hun period. In D. Sinor, ed., The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 177-205.</ref> A major part of Attila's army were Germans, during the Huns' campaign against the Roman Empire.<ref>Jane Penrose. Rome and Her Enemies: An Empire Created and Destroyed by War The Germans and the Romans. Cambridge, England, UK: Osprey Publishing, 2008. Pp. 288.</ref> After Attila's unexpected death the Hunnic Empire collapsed with the Huns disappearing as a people in Europe - who either escaped into Asia, or otherwise blended in amongst Europeans.<ref>Brian A. Pavlac. A Concise Survey of Western Civilization: Supremacies and Diversities Throughout History. Rowman & Littlefield, 2010. Pp. 102.</ref> | |||

| During the wars waged in the Baltic by the Catholic German ]; the lands inhabited by the ethnic group of the ] (the current reference to the people known then simply as the "Prussians"), were conquered by the Germans. The Old Prussians were an ethnic group related to the ] and ] Baltic peoples.<ref>Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier. ''Soziolinguistik: Ein Internationales Handbuch Zur Wissenschaft Von Sprache und Gesellschaft''. English translation edition. Walter de Gruyter, 2006. Pp. 1866.</ref> The former German state of ] took its name from the Baltic Prussians, although it was led by Germans who had assimilated the Old Prussians; the old Prussian language was extinct by the 17th or early 18th century.<ref name="Lang extinct">Encyclopædia Britannica entry 'Old Prussian language'</ref> The ] people of the Teutonic-controlled Baltic were assimilated into German culture and eventually there were many intermarriages of Slavic and German families, including amongst the Prussia's aristocracy known as the ]s.<ref name="autogenerated1914">G. J. Meyer. ''A World Undone: The Story of the Great War 1914 to 1918''. Random House Digital, Inc., 2007. Pp. 179.</ref> Prussian military strategist ] is a famous German whose surname is of Slavic origin.<ref name="autogenerated1914"/> | |||

| By the ], large numbers of ] lived in the ] and had assimilated into German culture, including many Jews who had previously assimilated into French culture and had spoken a mixed Judeo-French language.<ref name="Ulrich Ammon 2006">Ulrich Ammon, Norbert Dittmar, Klaus J. Mattheier. ''Soziolinguistik: Ein Internationales Handbuch Zur Wissenschaft Von Sprache und Gesellschaft''. English translation edition. Walter de Gruyter, 2006. Pp. 1925.</ref> Upon assimilating into German culture, the Jewish German peoples incorporated major parts of the German language and elements of other European languages into a mixed language known as ].<ref name="Ulrich Ammon 2006"/> However tolerance and assimilation of Jews in German society suddenly ended during the ] with many Jews being forcefully expelled from Germany and Western Yiddish disappeared as a language in Germany over the centuries, with German Jewish people fully adopting the German language.<ref name="Ulrich Ammon 2006"/> By the 1820s, large numbers of Jewish German women had intermarried with Christian German men and had converted to Christianity.<ref>Deborah Sadie Hertz. How Jews Became Germans: The History of Conversion and Assimilation in Berlin. Yale University, 2007. Pp. 193.</ref> Jewish German ] was a prominent ] figure who promoted the unification of Germany in the mid-19th century.<ref>James F. Harris. A Study in the Theory and Practice of German Liberalism: Eduard Lasker, 1829-1884. University Press of America, 1984. Pp. 17.</ref> | |||

| The event of the ] and the politics that ensued has been cited as the origins of German identity that arose in response to the spread of a common German language and literature.{{sfn|Motyl|2001|pp=189}} Early German national culture was developed through literary and religious figures including ], ] and ].{{sfn|Kesselman|2009|pp=180}} The concept of a German nation was developed by German philosopher ].{{sfn|Motyl|2001|pp=189-190}}. The popularity of German identity arose in the aftermath of the ]<ref name="Jeffrey E. Cole 2011. Pp. 172"/> | |||

| Persons who speak German as their first language, look German and whose families have lived in Germany for generations are considered "most German", followed by categories of diminishing Germanness such as ] (people of German ancestry whose families have lived in Eastern Europe but who have returned to Germany), Restdeutsche (people living in lands that have historically belonged to Germany but which is currently outside of Germany), Auswanderer (people whose families have emigrated from Germany and who still speak German), German speakers in German speaking nations such as ], and finally people of German emigrant background who no longer speak German.<ref>Forsythe, Diana. 1989. German identity and the problem of history. ''History and ethnicity'', p.146</ref> | |||

| ==Language== | ==Language== | ||

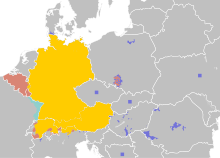

| [[File:Legal statuses of German in Europe.svg|thumb|right| | |||

| The ] in Europe: | |||

| <small>{{legend|#ffcc00|'''German''' ''''']''''': German is the official language (de jure or de facto) and first language of most of the population.}} | |||

| {{legend|#d98575|German is a co-official language but not the first language of most of the population.}} | |||

| {{legend|#7373d9|German (or a German dialect) is a legally recognized minority language (squares: geographic distribution too dispersed/small for map scale).}} | |||

| {{legend|#30efe3|German (or a variety of German) is spoken by a sizeable minority but has no legal recognition.}}</small>]] | |||

| {{Main|German language}} | {{Main|German language}} | ||

| {{Further|Geographical distribution of German speakers}} | |||

| ] is the native language of most Germans. It is the key marker of German ethnic identity.{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=313}}{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=172}} German is a ] language closely related to ] (in particular ] and ]), ], ], ], and ].{{sfn|Haarmann|2015|p=313}} Modern ] is based on ] and ], and is the first or second language of most Germans, but notably not the ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|p=288}} | |||

| ], which is often considered to be a distinct language from both German and Dutch, was the historical language of most of northern Germany, and is still spoken by many Germans, often as a second language.{{Citation needed|date=May 2023}} | |||

| The native language of Germans is German, a ], related to and classified alongside English and ], and sharing many similarities with the ] or Scandinavian languages. Spoken by approximately 100 million ],<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www2.ignatius.edu/faculty/turner/languages.htm |title=Most Widely Spoken Languages |publisher=.ignatius.edu |date=28 May 2011 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> German is one of the world's ] and the most widely spoken ] in the ]. | |||

| ===Dialects=== | |||

| {{Main|German dialects}} | |||

| [[File:Europe germanic-languages 2.PNG|thumb|right|'''West Germanic languages''' | |||

| {{legend|#9cff00|Dutch (Low Franconian, West Germanic)}} | |||

| {{legend|#38ff00|Low German (West Germanic)}} | |||

| {{legend|#00d200|Central German (High German, West Germanic)}} | |||

| {{legend|#008000|Upper German (High German, West Germanic)}} | |||

| {{legend|#ff8811|English (Anglo-Frisian, West Germanic)}} | |||

| {{legend|#ffbb77|Frisian (Anglo-Frisian, West Germanic)}} | |||

| '''North Germanic languages''' | |||

| {{legend|#0000ff|East Scandinavian}} | |||

| {{legend|#00ffff|West Scandinavian}} | |||

| {{legend|#ff0000|Line dividing the North and West Germanic languages}}]] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ** ] | |||

| *** ] (ca. 10 million) form the ] linguistic group, together with those ] who speak German and do not live in ] and the western Tyrol district of ]. ] (ca. 10 million) form the ] group, together with the ], Liechtensteiners, ] and ]ians. | |||

| ** ] dialect group (ca. 45 million) | |||

| *** ] | |||

| **** ] (], ]), forms a dialectal unity with ], ](]) | |||

| *** ] | |||

| **** ],<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.ethnologue.com/show_family.asp?subid=1205-16 |title=Ethnologue: East Middle German |accessdate=6 March 2011}}</ref> ], ], ], ] | |||

| ** ], a High German language of ] origin, spoken throughout the world. It developed as a fusion of German dialects with ], ] and traces of ].<ref>, Baumgarten and Frakes, Oxford University Press, 2005</ref><ref>, www.jewishgen.org</ref> | |||

| * ] (ca. 3–10 million), forms a dialectal unity with ] | |||

| ** ], ] | |||

| ===Native speakers=== | |||

| Global distribution of native speakers of the German language: | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Country | |||

| ! German speaking population (outside Europe) | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 5,000,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch"> (in German). Source lists "German expatriate citizens" only for Namibia and South Africa!</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 3,000,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 2,000,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 800,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 500,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 450,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> – 620,000<ref name="Statcan">{{cite web|url=http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/topics/RetrieveProductTable.cfm?ALEVEL=3&APATH=3&CATNO=&DETAIL=0&DIM=&DS=99&FL=0&FREE=0&GAL=0&GC=99&GK=NA&GRP=1&IPS=&METH=0&ORDER=1&PID=89189&PTYPE=88971&RL=0&S=1&ShowAll=No&StartRow=1&SUB=705&Temporal=2006&Theme=70&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&GID=837928 |title=Statistics Canada 2006 |publisher=2.statcan.ca |date=6 January 2010 |accessdate=15 March 2010}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 250,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 220,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 200,000<ref name=Chil>{{cite web|url=http://www.traduccion.at/4.html|title=Hablantes del alemán en el mundo|format=PDF|accessdate=7 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 110,000 | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 75,000 (German expatriate citizens)<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 66,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 56,000<ref name="Lizcano-CR"/> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 40,000<ref name=Mennonite>{{cite web|url=http://www.hshs.mb.ca/mennonite_old_colony_vision.pdf|title=The Mennonite Old Colony Vision: ''Under siege in Mexico and the Canadian Connection''|format=PDF|accessdate=30 May 2007}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 30,000 (German expatriate citizens)<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 25,000<ref name="Lizcano-CR">{{cite web |url=http://convergencia.uaemex.mx/rev38/38pdf/LIZCANO.pdf |title=Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI |language= ] |format=PDF |page=188 |accessdate=12 June 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/21/world/americas/21bolivia.html?_r=1&oref=slogin |title=Bolivian Reforms Raise Anxiety on Mennonite Frontier |publisher=Nytimes.com |date=2006-12-21 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://mexico.cnn.com/videos/2012/06/07/los-menonitas-en-bolivia |title=Los Menonitas en Bolivia |publisher=Mexico.cnn.com |date=2012-06-07 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 20,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 15,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] | |||

| | 10,000<ref name="Handwörterbuch" /> | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Geographic distribution== | ==Geographic distribution== | ||

| {{See also|German diaspora}} | |||

| ]s celebrate ] in ], Argentina.]] | |||

| ] | |||

| It is estimated that there are over 100 million Germans today, most of whom live in Germany, where they constitute the majority of the population. {{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=171–172}} There are also sizable populations of Germans in Austria, Switzerland, the United States, Brazil, France, Kazakhstan, Russia, Argentina, Canada, Poland, Italy, Hungary, Australia, South Africa, Chile, Paraguay, and Namibia.<ref name="Haarmann_Populations">{{harvnb|Haarmann|2015|p=313}}. "Of the 100 million German speakers worldwide, about three quarters (76 million) live in Germany, where they account for 92 percent of the population. Populations of Germans live elsewhere in Central and Western Europe, with the largest communities in Austria (7.6 million), Switzerland (4.2 million), France (1.2 million), Kazakhstan (900,000), Russia (840,000), Poland (700,000), Italy (280,000), and Hungary (250,000). Some 1.6 million U.S. citizens speak German as their first language, the largest number of German speakers overseas."</ref><ref name="Moser_Populations">{{harvnb|Moser|2011|pp=171–172}}. "The Germans live in Central Europe, mostly in Germany... The largest populations outside of these countries are found in the United States (5 million), Brazil (3 million), the former Soviet Union (2 million), Argentina (500,000), Canada (450,000), Spain (170,000), Australia (110,000), the United Kingdom (100,000), and South Africa (75,000). "</ref> | |||

| ] form an important minority group in several countries in ] and eastern Europe—(], ], ], ]) as well as in ] (]), ] (]) (approx. 3% of the population),<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.passeiweb.com/na_ponta_lingua/sala_de_aula/geografia/geografia_do_brasil/demografia_imigracoes/brasil_imigracoes_alemanha |title=A Imigração Alemã| Brasil | 14.01.2010 |publisher=Passeiweb.com |date=6 January 1990 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> ] (]) (~ 7,5% of the population)<ref>] Descendants of Germans in Argentina</ref> and ] (]) (approx. 3,1% of the population).<ref name="dw.de">{{cite web|url=http://www.dw.de/alemanes-en-chile-entre-el-pasado-colono-y-el-presente-empresarial/a-14958983-1 |title=Alemanes en Chile: entre el pasado colono y el presente empresarial | Sociedad | |publisher=DW.DE |date=2011-03-31 |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref> | |||

| Some groups may be classified as Ethnic Germans despite no longer having German as their mother tongue or belonging to a distinct German culture. Until the 1990s, two million Ethnic Germans lived throughout the former Soviet Union, particularly in Russia and ]. | |||

| In the United States 1990 census, 57 million people were fully or partly of German ancestry, forming the largest single ethnic group in the country. States with the highest percentage of Americans of German descent are in the northern ] (especially ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ]) and the ] state, ]. But Germanic immigrant enclaves existed in many other states (e.g., the ]s and the ], Colorado area) and to a lesser extent, the Pacific Northwest (i.e. ], ], ] and ]). | |||

| Notable Ethnic German minorities also exist in other ] countries such as ] (approx. 10% of the population) and ] (approx. 4% of the population). As in the United States, most people of German descent in Canada and Australia have almost completely assimilated, culturally and linguistically, into the English-speaking mainstream. | |||

| Distribution of German citizens and people claiming German ancestry (figures are only estimates and actual population could be higher, because of wrongly formulated questions in censuses in various countries (for example in Poland)<ref>{{cite web|url=http://lubczasopismo.salon24.pl/niemcy/post/414105,ilu-niemcow-w-slazakach |language=Polish |title=Number of Germans in Silesia (difficulties with the latest census) |publisher=Lubczasopismo.salon24.pl |date= |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref> and other different factors, f.e. related to participant in a census):{{-}} | |||

| {| class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- | |||

| ! Country | |||

| ! ] | |||

| ! ] | |||

| ! Comments | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Germany}} | |||

| | 66,420,000 | |||

| | 75,000,000<ref name="2005 Microcensus"/> | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|USA}} | |||

| | 50,000,000<ref>49.2 million ] as of 2005 according to the {{cite web |url=http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/IPTable?_bm=y&-reg=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201:535;ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201PR:535;ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201T:535;ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201TPR:535&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201PR&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201T&-qr_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_S0201TPR&-ds_name=ACS_2005_EST_G00_&-TABLE_NAMEX=&-ci_type=A&-redoLog=false&-charIterations=047&-geo_id=01000US&-format=&-_lang=en|coauthors=United States Census Bureau|title=US demographic census|accessdate=2 August 2007}}; see also ].</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Brazil}} | |||

| | 5,000,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.passeiweb.com/na_ponta_lingua/sala_de_aula/geografia/geografia_do_brasil/demografia_imigracoes/brasil_imigracoes_alemanha |title=A Imigração Alemã no Brasil | 25.07.2004 |publisher=Passeiweb.com |date=6 January 1990 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Canada}} | |||

| | 3,200,000<ref> gives 2,742,765 total respondents stating their ''ethnic origin'' as partly German, with 705,600 stating "single-ancestry", see ].</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Argentina}} | |||

| | 3,100,000<ref>Including ''Volga Germans'', ''Swiss Germans'', ''Mennonites'', and other German ancestries {{dead link|date=January 2013}}</ref><ref name=GermanArgentine>{{cite web|url=http://www.embajada-alemana.org.ar/culturas/becas1.htm |archiveurl=http://web.archive.org/web/20100213071340/http://www.embajada-alemana.org.ar/culturas/becas1.htm |archivedate=13 February 2010 |title=Internet Archive Wayback Machine |publisher=Web.archive.org |date=13 February 2010 |accessdate=2 August 2012}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.buenosaires.gob.ar/areas/secretaria_gral/colectividades/?col=1 |title=Obsevatorio de Colectividades – Comunidad Alemana |publisher=Buenosaires.gob.ar |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | 50,000<ref name="GermanArgentine"/> | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|South Africa}} | |||

| | 1,200,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.webcitation.org/query?url=http://www.geocities.com/Heartland/meadows/7589/intro_en.html&date=2009-10-25+10:34:36 |title=Germans in South Africa |publisher=Webcitation.org |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref><ref>Professor JA Heese in his book Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner (''The Origins of Afrikaners'') claims the modern ]s (who total around 3.5 million) have 34.4% German heritage. </ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ]. Although studies show that between 30–40% of Afrikaners have German ancestry, due to intermarriage this figure is likely to be much higher. | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flag|CIS}} | |||

| | 1,000,000 | |||

| | 600,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.perepis2002.ru/index.html?id=17 |title=597,212 in Russia as of 2002, 0.4 of Russian population |publisher=Perepis2002.ru |date= |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref> | |||

| | see ], ], ], ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|France}} | |||

| | 1,000,000<ref>{{cite web|author=Vladimir Geroimenko |url=http://www.ling.gu.se/projekt/sprakfrageladan/english/varldskarta/eng-fra.html |title=France |publisher=Ling.gu.se |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.everyculture.com/Europe/Alsatians.html |title=Alsatians |publisher=Everyculture.com |date=16 January 2010 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | predominant ethnic group of ] and ]; 970,000 with German dialects as mother tongue | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Australia}} | |||

| | 812,000<ref>The {{PDFlink||424 KB}} reports 742,212 people of German ancestry in the 2001 Census. German is spoken by ca. 135,000 , about 105,000 of them Germany-born, see ]</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | incl. 106,524 German-born. See ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Chile}} | |||

| | 500,000<ref name="dw.de"/> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Italy}} <small>(in ])</small> | |||

| | 500,000<ref>http://demo.istat.it/str2006/query.php?lingua=ita&Rip=S0&paese=A11&submit=Tavola</ref><ref>. Provincial Statistics Institute.</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Netherlands}} | |||

| | | |||

| | 179,000<ref>378,947 (2010, 2.3% of Dutch population). </ref> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|United Kingdom}} | |||

| | 262,000<ref>German born only; </ref><ref>This figure includes children born to British Military personnel serving on British Military bases in Germany</ref> | |||

| | 92,000<ref>2008, 0.15% of UK population. {{dead link|date=January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Spain}} | |||

| | 255,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ine.com |title=INE(2006) |publisher=INE |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | German immigrants | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Switzerland}} | |||

| | | |||

| | 266,000<ref>265,944 (2009, 3.3% of Swiss population) , Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 163 923 resident aliens (nationals or citizens) in 2004 (2.2% of total population), compared to 112 348 as of 2000. . 4.6 million including ] ]: , identifies the 65% (4.9 million) Swiss German speakers as "ethnic Germans".</ref> | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Poland}} | |||

| | 153,000<ref>2002 census</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | ]. The minority is concentrated mainly in ] (particularly in ]). | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Peru}} | |||

| | 180,000<ref>{{es}} </ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Hungary}} | |||

| | 120,344<ref>{{dead link|date=September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Austria}} | |||

| | | |||

| | 124,710<ref>2008, 1.5% of Austrian population. {{dead link|date=January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Israel}} | |||

| | | |||

| | 100,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4076384,00.html |title=Money overcomes ideology as Israelis hunt down German passports| Yediot Ahronot | 31.05.2011 |work=Ynetnews |date=20 June 1995 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Venezuela}} | |||

| | 70,000 | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Romania}} | |||

| | 60,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/diplo/en/Laender/Rumaenien.html |title=German minority |language={{de icon}} |publisher=Auswaertiges-amt.de |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Uruguay}} | |||

| | 46,000 | |||

| | 6,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/diplo/es/Laenderinformationen/01-Laender/Uruguay.html |title=There are 6,000 Germans living in Uruguay today and 40,000 descendants of Germans |language={{de icon}} |publisher=Auswaertiges-amt.de |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Czech Republic}} | |||

| | 40,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.radio.cz/en/article/27184 |title=Ethnic German Minorities in the Czech Republic, Poland and Slovakia |publisher=Radio.cz |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Bolivia}} | |||

| | 40,000<ref>{{cite web|last=Romero |first=Simon |url=http://www.iht.com/articles/2006/12/21/news/bolivia.php |title=Land reform worries Bolivia's Mennonites |work=International Herald Tribune |date=21 December 2006 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | German speaking Mennonites. See ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Belgium}} | |||

| | 38,366<ref>{{nl}} {{cite web|url=http://statbel.fgov.be/nl/modules/publications/statistiques/bevolking/Bevolking_nat_geslacht_leeftijdsgroepen.jsp|title=Bevolking per nationaliteit, geslacht, leeftijdsgroepen op 1 January 2008|publisher=]|accessdate=30 May 2010}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | excludes ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Norway}} | |||

| | 25,000 <ref> ], retrieved January 11, 2013</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| |First and second generation immigrants. | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Ecuador}} | |||

| | 33,000<ref>{{cite web|author=Joshua Project |url=http://www.joshuaproject.net/countries.php |title=Ethnic groups around the world |publisher=joshuaproject.net |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Namibia}} | |||

| | 30,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=940DE2D71E3CF935A15751C1A96E948260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=print |title=Amid Namibia's White Opulence, Majority Rule Isn't So Scary Now |work=The New York Times |date=26 December 1988 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Dominican Republic}} | |||

| | 25,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/diplo/en/Laender/DominikanischeRepublik.html |title=Dominican Republic |language={{de icon}} |publisher=Auswaertiges-amt.de |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Denmark}} | |||

| | 15,000–20,000<ref>in the German-Danish border region; see </ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Greece}} | |||

| | | |||

| | 15,498<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.statistics.gr/portal/page/portal/ESYE/BUCKET/A1604/Other/A1604_SAP03_TB_DC_00_2001_09_F_GR.pdf |title=Greeks Census 2001 |format=PDF |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Ireland}} | |||

| | 11,797<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.cso.ie/statistics/placebirthagegroup.htm |title=CSO: Statistics: Persons usually resident and present in the State on Census Night, classifieid by place of birth and age group |publisher=Cso.ie |date=13 May 2008 |accessdate=28 September 2011}}{{dead link|date=January 2013}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Slovakia}} | |||

| | 5000–10,000<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/diplo/en/Laenderinformationen/01-Laender/Slowakei.html |title=Slovakia |language={{de icon}} |publisher=Auswaertiges-amt.de |accessdate=28 September 2011}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Philippines}} | |||

| | 6,400<ref>2000 census</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Serbia}} | |||

| | 3,900 | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Croatia}} | |||

| | 2,900 | |||

| | | |||

| | see ] | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Turkmenistan}} | |||

| | 2,700<ref name="joshuaproject.net">{{cite web|author=Joshua Project |url=http://www.joshuaproject.net/peopctry.php |title=Tajik, Afghan of Afghanistan Ethnic People Profile |publisher=Joshuaproject.net |date= |accessdate=2013-01-07}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| |{{flagcountry|Tajikistan}} | |||

| | 2,700<ref name="joshuaproject.net"/> | |||

| | | |||

| |- | |||

| | {{flagcountry|Jamaica}} | |||

| | 160<ref>{{cite web|url=http://jamaica-gleaner.com/pages/history/story0060.htm Out Of Many Cultures The People Who Came The Arrival Of The GERMANS |title=The Arrival of the GERMANS |work=Jamaica Gleaner |date=2 March 2004 |accessdate=31 May 2012}}</ref> | |||

| | | |||

| | ] | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

| {{ |

{{See also|Culture of Germany}} | ||

| ] in ]; remembering ] is an essential part of modern German culture.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=174}}]] | |||

| The Germans are marked by great regional diversity, which makes identifying a single German culture quite difficult.{{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=176–177}} The arts and sciences have for centuries been an important part of German identity.{{sfn|Waldman|Mason|2005|pp=334–335}} The ] and the ] saw a notable flourishing of German culture. Germans of this period who contributed significantly to the arts and sciences include the writers ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and the ], the philosopher ], the architect ], the painter ], and the composers ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ].{{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=176–177}} | |||

| Popular German dishes include ] and ]. Germans consume a high amount of ], particularly beer, compared to other European peoples. Obesity is relatively widespread among Germans.{{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=176–177}} | |||

| ===Literature=== | |||

| {{Main|German literature}} | |||

| ], Berlin, a sculpture honoring ] and some of Germany's most influential writers]] | |||

| ] (German: ''Karneval'', ''Fasching'', or ''Fastnacht'') is an important part of German culture, particularly in ] and the ]. An important German festival is the ].{{sfn|Moser|2011|pp=176–177}} | |||

| German literature can be traced back to the ], with the most notable authors of the period being ] and ]. | |||

| The '']'', whose author remains unknown, is also an important work of the epoch, as is the '']''. The fairy tales collections collected and published by ] in the 19th century became famous throughout the world. | |||

| A steadily shrinking majority of Germans are ]. About a third are ], while one third adheres to ]. Another third does not profess any religion.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=172}} Christian holidays such as ] and ] are celebrated by many Germans.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=176}} The number of ]s is growing.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=176}} There is also a notable ] community, which was decimated in ].{{sfn|Minahan|2000|p=174}} Remembering the Holocaust is an important part of German culture.{{sfn|Moser|2011|p=174}} | |||

| Theologian ], who translated the Bible into German, is widely credited for having set the basis for the modern "High German" language. Among the most admired German poets and authors are ], ], ], ], ], ], ] and ]. Nine Germans have won the ]: ], ], ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. | |||

| ===Philosophy=== | |||

| {{Main|German philosophy}} | |||

| Germany's influence on philosophy is historically significant and many notable German philosophers have helped shape ] since the Middle Ages. The rise of the modern natural sciences and the related decline of religion raised a series of questions, which recur throughout German philosophy, concerning the relationships between knowledge and faith, reason and emotion, and scientific, ethical, and artistic ways of seeing the world. | |||

| ]]] | |||

| ] have helped shape ] from as early as the Middle Ages (]). Later, ] (17th century) and most importantly ] played central roles in the ]. ] inspired the work of ] and ] as well as ] defended by ] and ]. ] and ] developed ] in the second half of the 19th century while ] and ] pursued the tradition of German philosophy in the 20th century. A number of German intellectuals were also influential in ], most notably ], ], ], ], ], ], and ]. The ] founded in 1810 by linguist and philosopher ] served as an influential model for a number of modern western universities. | |||