| Revision as of 14:40, 8 April 2013 edit204.131.75.162 (talk)No edit summaryTag: possible vandalism← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 10:02, 20 December 2024 edit undoTkarcher (talk | contribs)160 editsm reverted vandalism | ||

| (557 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|U.S. national memorial in Washington, D.C.}} | |||

| {{Other uses|World War II Memorial (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{Use American English|date=August 2020}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=November 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox protected area | {{Infobox protected area | ||

| | name = |

| name = World War II Memorial | ||

| | photo = |

| photo = Lincoln_and_WWII_memorials.jpg | ||

| | photo_width = |

| photo_width = 350 | ||

| | photo_caption = The memorial in Washington D.C. | |||

| | map = USA relief | |||

| | map = United States Washington, D.C. central#Washington, D.C. | |||

| | map_caption = | |||

| | location = ] | | relief = 1 | ||

| | location = ] | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|38|53|22|N|77|2|26|W|region:US_type:landmark_scale:1000|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | nearest_city = | |||

| | established = April 29, 2004 | |||

| | lat_d = 38 | lat_m = 53 | lat_s = 21.84 | lat_NS = N | |||

| | visitation_num = 4.6 million | |||

| | long_d = 77 | long_m = 2 | long_s = 25.86 | long_EW = W | |||

| | |

| visitation_year = 2018 | ||

| | coords_ref = | |||

| | coor_type = landmark_scale:1000 | |||

| | area = | |||

| | established = May 29, 2002 | |||

| | visitation_num = 4,410,379 | |||

| | visitation_year = 2005 | |||

| | governing_body = ] | | governing_body = ] | ||

| | website = | |||

| }}<!-- Note: site is not listed in IUCN database --> | |||

| |}}<!-- Note: site is not listed in IUCN database --> | |||

| The '''World War II Memorial''' is a ]<ref>{{cite web |url=http://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/103/32.pdf |title=Public Law 103-32 |date=May 25, 1993 |website=uscode.house.gov |access-date=August 15, 2015 |archive-date=October 10, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221010083036/http://uscode.house.gov/statutes/pl/103/32.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/chapter-1/subchapter-LXI |title=16 U.S. Code Subchapter LXI – National and International Monuments and Memorials |website=LII / Legal Information Institute |access-date=August 15, 2015 |archive-date=May 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230519022228/https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/16/chapter-1/subchapter-LXI |url-status=live }}</ref> dedicated to ] in the ] and as civilians during ]. It is located on the ] in ] | |||

| The ] '''National World War II Memorial''' is a ] dedicated to ] who served in the armed forces and as civilians during ]. Consisting of 56 pillars and a pair of small ]es surrounding a plaza and fountain, it is located on the ] in ], on the former site of the ] at the eastern end of the ], between the ] and the ]. | |||

| The memorial consists of 56 granite pillars, decorated with bronze ]s, representing ] and ], and a pair of small ]es for the Atlantic and Pacific theaters, surrounding an oval plaza and fountain. On its short axis is a memorial wall of ] representing the fallen, and opposite, a sloped and stepped entrance plaza leading up to the oval from 17th Street. Its initial design was submitted by Austrian-American architect ]. | |||

| It opened to the public on April 29, 2004, and was dedicated by ] ] on May 29, 2004, two days before ].<ref></ref> The memorial is administered by the ] under its ] group.<ref></ref> As of 2009, more than 4.4 million people visit the memorial each year.{{Citation needed|date=May 2009}} | |||

| Opened on April 29, 2004, it replaced the ] at the eastern end of the ], between the ] and the ]. Dedicated by ] ] on May 29, 2004,<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wwiimemorial.com/ |title=WWII Memorial |website=www.wwiimemorial.com |access-date=June 12, 2008 |archive-date=May 19, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230519033349/http://wwiimemorial.com/ |url-status=live }}</ref> the memorial is administered by the ] under its ] group.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.nps.gov/nwwm/ |title=World War II Memorial (U.S. National Park Service) |website=www.nps.gov |access-date=April 11, 2005 |archive-date=November 5, 2010 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20101105104642/http://www.nps.gov/nwwm |url-status=live }}</ref> More than 4.6 million people visited the memorial in 2018.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://irma.nps.gov/Stats/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recreation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=WWII |title=Stats Report Viewer: World War II Memorial |website=irma.nps.gov |access-date=April 22, 2019 |archive-date=June 24, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20220624082243/https://irma.nps.gov/STATS/SSRSReports/Park%20Specific%20Reports/Annual%20Park%20Recreation%20Visitation%20(1904%20-%20Last%20Calendar%20Year)?Park=WWII |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Overview== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| The memorial consists of 56 ] ]s, each {{convert|17|ft|m}} tall, arranged in a ] around a ] with two {{convert|43|ft|m|adj=on}} ]es on opposite sides. Two-thirds of the {{convert|7.4|acre|ha|adj=on}} site is landscaping and water. Each pillar is inscribed with the name of one of the 48 ]s of 1945, as well as the ], the ] and ], the ], ], ], ], and the ]. The northern arch is inscribed with "]"; the southern one, "]." The plaza is {{cvt|337|ft|10|in|m}} long and {{cvt|240|ft|2|in|m}} wide, is sunk {{convert|6|ft|m}} below ], and contains a pool that is {{convert|75.2|x|45.0|m|ftin|disp=flip}}.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wwiimemorial.com/default.asp?page=design.asp&subpage=memorialdesign |title=Memorial Design |publisher=National WWII Memorial |access-date=July 16, 2008 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080531165728/http://www.wwiimemorial.com/default.asp?page=design.asp&subpage=memorialdesign |archive-date=May 31, 2008}}</ref> | |||

| The memorial includes two<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM4F0R_Kilroy_Was_Here_World_War_II_Memorial_Washington_DC |title=Kilroy Was Here, World War II Memorial, Washington, D.C. – Kilroy Was Here on Waymarking.com |website=www.waymarking.com |access-date=August 28, 2011 |archive-date=January 27, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210127210107/https://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM4F0R_Kilroy_Was_Here_World_War_II_Memorial_Washington_DC |url-status=live }}</ref> inconspicuously located "]" engravings. Their inclusion in the memorial acknowledges the significance of the symbol to American soldiers during World War II and how it represented their presence and protection wherever it was inscribed.<ref>{{cite news |url=http://voices.washingtonpost.com/rawfisher/2006/05/kilroy_is_herecan_you_find_him.html |newspaper=The Washington Post |title=Kilroy Is Here – Can You Find Him? |access-date=August 28, 2011 |archive-date=December 7, 2022 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20221207140946/http://voices.washingtonpost.com/rawfisher/2006/05/kilroy_is_herecan_you_find_him.html |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| On approaching the semicircle from the east, a visitor walks along one of two walls (right side wall and left side wall) picturing scenes of the war experience in bas relief. As one approaches on the left (toward the Pacific arch), the scenes begin with soon-to-be servicemen getting physical exams, taking the oath, and being issued military gear. The reliefs progress through several iconic scenes, including combat and burying the dead, ending in a homecoming scene. On the right-side wall (toward the Atlantic arch) there is a similar progression, but with scenes generally more typical of the European theatre. Some scenes take place in England, depicting the preparations for air and sea assaults. The last scene is of ] when the western and eastern fronts met in Germany. | |||

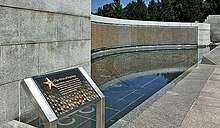

| == Wall of stars == | |||

| ] | |||

| The Freedom Wall is on the west side of the plaza, with a view of the ] and Lincoln Memorial behind it. The wall has 4,048 gold stars, each representing 100 Americans who died in the war. In front of the wall lies the message "Here we mark the price of freedom".<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.savethemall.org/updates/20040624.html |last=Knight |first=Christopher |work=] |date=May 23, 2004 |title=A memorial to forget |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20051226102047/http://www.savethemall.org/updates/20040624.html |archive-date=December 26, 2005}}</ref>{{efn|Many sources give the number of stars as 4,000. The wall contains 23 panels of 11 columns and 16 rows of stars. The number of stars can also be counted in ]. See also discussion at ].}} | |||

| ==History== | ==History== | ||

| ] | |||

| In 1987, World War II veteran Roger Durbin approached Representative ], a ] from ], to ask if a World War II memorial could be constructed. Kaptur introduced the World War II Memorial Act to the ] as HR 3742 on December 10. The resolution authorized the ] (ABMC) to establish a World War II memorial in "Washington, D.C., or its environs", but the bill was not voted on before the end of the session, so it was not passed. Two more times, in 1989 and 1991, Rep. Kaptur introduced similar legislation, but these bills suffered the same fate as the first, and did not become law. | |||

| ] | |||

| In 1987, World War II veteran Roger Durbin approached Representative ], a ] from ], to ask if a World War II memorial could be constructed. Kaptur introduced the World War II Memorial Act to the ] as HR 3742 on December 10. The resolution authorized the ] (ABMC) to establish a World War II memorial in "Washington, D.C., or its environs", but the bill was not voted on before the end of the session. In 1989 and 1991, Rep. Kaptur introduced similar legislation, but these bills suffered the same fate as the first and did not become law. | |||

| Kaptur reintroduced legislation in the House a fourth time as HR 682 on January 27, 1993, one day after Senator ] (a ] from ]) introduced companion Senate legislation. On March 17, 1993, the Senate approved the act, and the House approved an amended version of the bill on May 4. On May 12, the Senate also approved the amended bill, and the World War II Memorial Act was signed into law by President ] on May 25 of that year, becoming |

Kaptur reintroduced legislation in the House a fourth time as HR 682 on January 27, 1993, one day after Senator ] (a ] from ]) introduced companion Senate legislation. On March 17, 1993, the Senate approved the act, and the House approved an amended version of the bill on May 4. On May 12, the Senate also approved the amended bill, and the World War II Memorial Act was signed into law by President ] on May 25 of that year, becoming {{uspl|103|32}}. | ||

| ===Fundraising=== | ===Fundraising=== | ||

| On September 30, 1994, President |

On September 30, 1994, President Bill Clinton appointed a 12-member Memorial Advisory Board (MAB) to advise the ABMC in picking the site, designing the memorial, and raising money to build it.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://wwiiregistry.abmc.gov/timeline/|title=Timeline - WWII Memorial Registry|access-date=2023-09-27|archive-date=September 28, 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230928025820/https://wwiiregistry.abmc.gov/timeline/|url-status=live}}</ref> A ] fundraising effort brought in millions of dollars from individual Americans. Additional large donations were made by veterans' groups, including the ], the ], and Veterans of the Battle of the Bulge. The majority of the corporate fundraising effort was led by co-chairmen Senator ], a decorated World War II veteran and 1996 Republican nominee for president, and ], the ] and ] of ] and a former ] officer. The ] provided about $16 million; a total of $197 million was raised. Following his death in December 2021, Dole himself would have a memorial service held at the World War II Memorial.<ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/12/10/bob-dole-funeral-national-cathedral-world-war-ii-memorial/6451158001/ |title=Bob Dole hailed as war hero and 'Kansas' favorite son' at Washington funeral service |first1=Ledyard |last1=King |first2=Rebecca |last2=Morin |first3=Ella |last3=Lee |publisher=USA Today |date=10 December 2021 |accessdate=10 December 2021 |archive-date=May 16, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230516140228/https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/12/10/bob-dole-funeral-national-cathedral-world-war-ii-memorial/6451158001/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6j-E_kMmk8 |title=Bob Dole Honored At World War II Memorial |author=NBC News |publisher=YouTube |date=10 December 2021 |access-date=December 10, 2021 |archive-date=December 10, 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211210200307/https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6j-E_kMmk8 |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| ===Picking the site=== | ===Picking the site=== | ||

| On January 20, 1995, Colonel Kevin C. Kelley, project manager for the ABMC, organized the first meeting of the ABMC and the MAB, at which the project was discussed and initial plans made. The meeting was chaired by Commissioner F. Haydn Williams, chairman of ABMC's World War II Memorial Site and Design Committee, who would go on to guide the project through the site selection and approval process and the selection and approval of the Memorial's design. Representatives from the ], the ], the ], the ], and the National Park Service attended the meeting. The selection of an appropriate site was taken on as the first action. | |||

| ] | |||

| Over the next months, several sites were considered. Soon, 3 quickly gained favor:<ref>{{cite news |title=Site-seeking at the Mall: Placing World War II memorial in the grand scheme of things |author=Forgey, Benjamin |newspaper=The Washington Post |page=C1 |date=July 1, 1995}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=No Accord on WWII Memorial; Two Agencies Send Mixed Signals About Location |author=Forgey, Benjamin |newspaper=The Washington Post |page=B3 |date=July 28, 1995}}</ref> | |||

| In October 1994, Clinton signed Joint Resolution 227 into law, mandating that the monument be located in downtown Washington, near other memorials. On January 20, 1995, Colonel Kevin C. Kelley, project manager for the ABMC, organized the first meeting of the ABMC and the MAB, at which the project was discussed and initial plans made. The meeting was chaired by Commissioner F. Haydn Williams, chairman of ABMC's World War II Memorial Site and Design Committee, who would go on to guide the project through the site selection and approval process and the selection and approval of the Memorial's design. Representatives from the ], the ], the ], the ], and the National Park Service attended the meeting. Selection of an appropriate site was taken on as the first action. | |||

| * ] ] area – between 3rd Street and the ] | |||

| * ] – east end, between ] and the ] | |||

| Over the next months, several sites were considered. Three quickly gained favor:<ref>{{cite news |title=Site-seeking at the Mall: Placing World War II memorial in the grand scheme of things |author=Forgey, Benjamin |work=The Washington Post |page=C1 |date=1995-07-01 }}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=No Accord on WWII Memorial; Two Agencies Send Mixed Signals About Location |author=Forgey, Benjamin |work=The Washington Post |page=B3 |date=1995-07-28 }}</ref> | |||

| * ] – on ] between ] and 15th Streets | |||

| * ] ] area – between 3rd Street and the ] | |||

| * ] – east end, between ] and the ] | |||

| * ] – on ] between ] and 15th Streets | |||

| Other sites considered but quickly rejected were: | Other sites considered but quickly rejected were: | ||

| * ] |

* ] – northeast side, east of the Tidal Basin parking lot and west of the 14th Street Bridge access road | ||

| * ] |

* ] – between ] and the north shore of the ], northwest of the ] | ||

| * Grounds of the Washington Monument |

* Grounds of the Washington Monument – at Constitution Avenue between 14th and 15th Streets, west of the ] | ||

| * ], adjacent to ] |

* ], adjacent to ] – dropped from consideration because of its unavailability | ||

| The selection of the Rainbow Pool site was announced on October 5, 1995. The design would incorporate the Rainbow Pool fountain, located across 17th Street from the Washington Monument and near the Constitution Gardens site.<ref>{{cite news |title=WWII Memorial Gets Choice Mall Site; 2nd Panel Approves Location, Clearing Way for Design Phase |author=Forgey, Benjamin | |

The selection of the Rainbow Pool site was announced on October 5, 1995. The design would incorporate the Rainbow Pool fountain, located across 17th Street from the Washington Monument and near the Constitution Gardens site.<ref>{{cite news |title=WWII Memorial Gets Choice Mall Site; 2nd Panel Approves Location, Clearing Way for Design Phase |author=Forgey, Benjamin |newspaper=The Washington Post |page=B1 |date=October 6, 1995}}</ref> | ||

| The location, between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, is the most prominent spot for a monument on the National Mall since the Lincoln Memorial opened in 1922. It is the first addition in more than 70 years to the grand corridor of open space that stretches from the Capitol {{convert|2.1|mi|km}} west to the Potomac River.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-11-09-mn-1182-story.html |title=World War II memorial moves toward reality : Officials have agreed on a prominent site on the National Mall. Fund raising is the next task for sponsors. |first=Colleen |last=Krueger |date=November 9, 1995 |via=LA Times |access-date=September 23, 2016 |archive-date=September 23, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160923183928/http://articles.latimes.com/1995-11-09/news/mn-1182_1_world-war-ii-monument |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Design== | |||

| ] | |||

| ] in the background]] | |||

| A nationwide design competition drew 400 submissions from architects from around the country. ]'s initial design was selected in 1997. Over the next four years, St. Florian's design was altered during the review and approval process required of proposed memorials in Washington, D.C. Ambassador Haydn Williams guided the design development for ABMC. | |||

| ===Designing the memorial=== | |||

| The final design consists of 56 ] ]s, each 17 feet (5 m) tall, arranged in a ] around a ] with two 43-foot (13 m) ]es, crafted by ], on opposite sides. Two-thirds of the {{convert|7.4|acre|m2|adj=on}} site is landscaping and water. Each pillar is inscribed with the name of one of the 48 ] of 1945, as well as the ], the ] and ], the ], ], ], ], and the ]. The northern arch is inscribed with "]"; the southern one, "]." The plaza is 337 ft, 10 in (103.0 m) long and 240 feet, 2 inches (73.2 m) wide, is sunk 6 feet (1.8 m) below ], and contains a pool that is 246 feet 9 inches by 147 feet 8 inches (75.2 × 45.0 m).<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.wwiimemorial.com/default.asp?page=design.asp&subpage=memorialdesign |title=Memorial Design |publisher=National WWII Memorial |accessdate=2008-07-16}}</ref> | |||

| A nationwide design competition drew 400 submissions from architects from around the country. ]'s initial design was selected in 1997. St. Florian's design evokes a classical monument. Under each of the two memorial arches, the Pacific and Atlantic baldachinos, four eagles carry an oak laurel wreath. Each of the 56 pillars bear wreaths of oak symbolizing military and industrial strength, and of wheat, symbolizing agricultural production. | |||

| Over the next four years, St. Florian's design was altered during the review and approval process required of proposed memorials in Washington, D.C. Ambassador Haydn Williams guided the design development for ABMC. | |||

| The memorial includes two<ref>http://www.waymarking.com/waymarks/WM4F0R_Kilroy_Was_Here_World_War_II_Memorial_Washington_DC</ref> inconspicuously located "]" engravings. Their inclusion in the memorial acknowledges the significance of the symbol to American soldiers during World War II.<ref>{{cite news| url=http://voices.washingtonpost.com/rawfisher/2006/05/kilroy_is_herecan_you_find_him.html | work=The Washington Post | title=Kilroy Is Here--Can You Find Him?}}</ref> | |||

| On approaching the semicircle from the east, a visitor walks along one of two walls (right side wall and left side wall) picturing scenes of the war experience in bas relief. As one approaches on the left (toward the Pacific arch), the scenes begin with soon-to-be servicemen getting physical exams, taking the oath, and being issued military gear. The reliefs progress through several iconic scenes, including combat and burying the dead, ending in a homecoming scene. On the right-side wall (toward the Atlantic arch) there is a similar progression, but with scenes generally more typical of the European theatre. Some scenes take place in England, depicting the preparations for air and sea assaults. The last scene is of a handshake between the American and Russian armies when the western and eastern fronts met in Germany. | |||

| ===Freedom Wall=== | |||

| The Freedom Wall is on the west side of the memorial, with a view of the ] and Lincoln Memorial behind it. The wall has 4,048 gold stars, each representing 100 Americans who died in the war. In front of the wall lies the message "Here we mark the price of freedom".<ref>{{cite news |url=http://www.savethemall.org/updates/20040624.html |last=Knight |first=Christopher |work=] |date=2004-05-23 |title=A memorial to forget}} — Many sources give the number of stars as 4,000. The wall contains 23 panels of 11 columns and 16 rows of stars. The number of stars can also be counted in ]. See also discussion at ].</ref> | |||

| ==Construction== | ==Construction== | ||

| Ground was broken in November 2000. The construction was managed by ]. | |||

| ] | |||

| Ground was broken in September 2001. The construction was managed by the ]. | |||

| Sculptor ] created the bronze eagles and wreaths that were installed under the arches, as well as 24 bronze ] panels that depict wartime scenes of combat and the home front.<ref></ref> The bronzes were cast over the course of two and a half years at Laran Bronze in ].<ref name="knol">{{cite web |url=http://knol.google.com/k/stephen-r-brown/wwii-memorial/3g98ta32adgw9/2?locale=en# |title=WWII |

New England Stone Industries of Rhode Island was hired by the general contractor to fabricate the stone; it worked closely with St. Florian and the ABMC throughout the process.{{Citation needed|date=February 2024}} The triumphal arches were sub-contracted to and crafted by ]. Sculptor ] created the bronze eagles and two wreaths that were installed under the arches, as well as 24 bronze ] panels that depict wartime scenes of combat and the home front.<ref> {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080407152929/http://www.carnegiemellontoday.com/article.asp?Aid=83 |date=April 7, 2008 }}</ref> The bronzes were cast over the course of two and a half years at ] in ].<ref name="knol">{{cite web |url=http://knol.google.com/k/stephen-r-brown/wwii-memorial/3g98ta32adgw9/2?locale=en# |title=WWII Memorial|access-date=September 9, 2009}}{{dead link|date=February 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> The stainless-steel armature that holds up the eagles and wreaths was designed at Laran, in part by sculptor ],<ref name="peniston">{{cite web |url=http://www.jepsculpture.com/bio.shtml |title=James Peniston Sculpture: Bio |access-date=September 9, 2008 |archive-date=July 25, 2008 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080725132921/http://www.jepsculpture.com/bio.shtml |url-status=live }}</ref> and fabricated by Apex Piping of ].<ref name="folklife">{{cite web |url=http://www.folklife.si.edu/national-wwii-reunion/building-the-memorial/smithsonian |title=Building the Memorial |publisher=Smithsonian Institution |work=Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage |access-date=June 22, 2016 |archive-date=June 24, 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20160624052900/http://www.folklife.si.edu/national-wwii-reunion/building-the-memorial/smithsonian |url-status=live }}</ref> The twin bronze wreaths decorating the 56 granite pillars around the perimeter of the memorial – as well as the 4,048 gold-plated silver stars representing American military deaths in the war – were cast at Valley Bronze in ].<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.valleybronze.com/projects.html |title=Projects |website=Valley Bronze of Oregon |access-date=September 22, 2018 |archive-date=September 23, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180923005845/http://www.valleybronze.com/projects.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.oregonmag.net/WWIIBronze.htm |title=Oregon Magazine |last=Leonard |first=Larry |website=www.oregonmag.net |access-date=September 22, 2018 |archive-date=September 23, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180923052115/http://www.oregonmag.net/WWIIBronze.htm |url-status=live }}</ref> "I'd see buckets full of the stars going through the foundry, and think that each stood for 100 men. The magnitude was overwhelming," Dave Jackman, former president of Valley Bronze, recalled in 2004.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.wallowa.com/20040415/bronze-from-joseph-part-of-wwii-monument |title=Bronze from Joseph part of WWII monument |work=Wallowa County Chieftain |access-date=September 22, 2018 |archive-date=September 23, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180923005825/http://www.wallowa.com/20040415/bronze-from-joseph-part-of-wwii-monument |url-status=live }}</ref> | ||

| ] designed |

] designed the lettering for the memorial and most of the inscriptions were hand-carved ''in situ''. | ||

| The memorial opened to the public on April 29, 2004, and was dedicated in a May 29 ceremony attended by thousands of people. The memorial became a |

The memorial opened to the public on April 29, 2004, and was dedicated in a May 29 ceremony attended by thousands of people. The memorial became a unit of the national park system on November 1, when authority over it was transferred to the National Park Service. | ||

| <gallery caption="The memorial under construction" mode="packed" heights="180"> | |||

| Image:Washington Monument August 2002 02.jpg|August 2002 | |||

| Image:World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. under construction (August 12, 2002).jpg|August 2002 | |||

| Image:WWII memorial under construction 20030406 105243.jpg|April 2003 | |||

| Image:Wwii memorial construction 1.677.jpg|January 2004 | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==Controversy== | ==Controversy== | ||

| ===Criticism of the location=== | ===Criticism of the location=== | ||

| Critics such as the National Coalition to Save Our Mall opposed the location of the memorial. A major criticism of the location was that it would interrupt what had been an unbroken view between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. The memorial was also criticized for taking up open space that had been historically used for major ] and ]s.<ref name="wapo-bush">{{cite |

Critics such as the National Coalition to Save Our Mall opposed the location of the memorial. A major criticism of the location was that it would interrupt what had been an unbroken view between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. The memorial was also criticized for taking up open space that had been historically used for major ] and ]s.<ref name="wapo-bush">{{cite news |first1=Linda |last1=Wheeler |first2=Spencer S. |last2=Hsu |title=Bush Backs War Memorial |newspaper=] |via=nationalmallcoalition.org |date=May 17, 2001 |url=https://www.nationalmallcoalition.org/2001/05/bush-backs-war-memorial-the-washington-post/ |access-date=November 5, 2019 |archive-date=November 5, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191105221349/https://www.nationalmallcoalition.org/2001/05/bush-backs-war-memorial-the-washington-post/ |url-status=live }}</ref><ref name="wapo-fisher">{{cite news |last=Fisher |first=Marc |title=A Memorial That Doesn't Measure Up |newspaper=] |date=May 4, 2004 |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A64436-2004May3.html |access-date=November 5, 2011 |archive-date=September 28, 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110928053628/http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/articles/A64436-2004May3.html |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.savethemall.org/wwii/index.html |title=The World War II Memorial Defaces a National Treasure |access-date=June 2, 2007 |date=January 2001 |publisher=National Coalition to Save Our Mall |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070504055606/http://www.savethemall.org/wwii/index.html |archive-date=May 4, 2007}}</ref>] | ||

| Critics were particularly bothered by the expedited approval process, which is |

Critics were particularly bothered by the expedited approval process, which is considerably lengthy most of the time.<ref>{{cite news |first=Alex |last=Van Oss |url=https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1119095 |title=World War II Memorial |format=] |work=Weekend Edition Sunday |publisher=] |date=February 25, 2001 |access-date=June 2, 2007 |archive-date=March 8, 2007 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070308045110/http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1119095 |url-status=live }}</ref> The United States Congress, worried that World War II veterans were dying before an appropriate memorial could be built, passed legislation exempting the World War II Memorial from further site and design review. Congress also dismissed pending legal challenges to the memorial.<ref>{{cite news |first=Michael |last=Killian |title=Senate OKs WWII Memorial |work=] |url=http://www.savethemall.org/media/senateok.html |date=May 22, 2001 |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20070928120323/http://www.savethemall.org/media/senateok.html |archive-date=September 28, 2007}}</ref> | ||

| ===Criticism of the design and style=== | ===Criticism of the design and style=== | ||

| There were also aesthetic objections to the design. A critic from the '']'' described the monument as "vainglorious, demanding of attention and full of trite imagery."<ref>{{cite news |first=Thomas M. Jr. |last=Keane |url=https://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/bostonherald/655430941.html?did=655430941&FMT=ABS&FMTS=FT&date=Jun+25%2C+2004&author=THOMAS+M.+KEANE+JR.&pub=Boston+Herald&desc=Op-Ed%3B+WW+II+Memorial+fails+both+past%2C+present |archive-url=https://archive.today/20130131155439/http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/bostonherald/655430941.html?did=655430941&FMT=ABS&FMTS=FT&date=Jun+25,+2004&author=THOMAS+M.+KEANE+JR.&pub=Boston+Herald&desc=Op-Ed;+WW+II+Memorial+fails+both+past,+present |url-status=dead |archive-date=January 31, 2013 |title=WWII Memorial fails both past, present |work=] |page=27 |date=June 25, 2004}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| '']'' argued that "this pompous style was also favored by ] and ]"<ref>{{cite news |first=Inga |last=Saffron |authorlink=Inga Saffron |title=Monument to Democracy, The National World War II Memorial deserves its prominent location in Washington, as a tribute to heroes and a great cause |work=] |page=E01 |date=May 28, 2004}}</ref> '']'' described it as "overbearing", "bombastic", and a "hodgepodge of cliche and Soviet-style pomposity" with "the emotional impact of a slab of granite".<ref name="wp2004">{{cite news |last=Fisher |first=Marc |date=May 4, 2004 |title=A Memorial That Doesn't Measure Up |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/local/2004/05/04/a-memorial-that-doesnt-measure-up/c634988b-674f-4964-ab3a-43e46b0bea2b/ |access-date=24 October 2024 |newspaper=] |page=B01}}</ref> | |||

| There were also aesthetic objections to the design. A critic from the '']'' described the monument as "vainglorious, demanding of attention and full of trite imagery."<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |first = Thomas M., Jr. | |||

| |last = Keane | |||

| |url = http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/bostonherald/655430941.html?did=655430941&FMT=ABS&FMTS=FT&date=Jun+25%2C+2004&author=THOMAS+M.+KEANE+JR.&pub=Boston+Herald&desc=Op-Ed%3B+WW+II+Memorial+fails+both+past%2C+present | |||

| |title = WWII Memorial fails both past, present | |||

| |publisher = '']'' | |||

| |page = 27 | |||

| |date = June 25, 2004 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| '']'' argued that "this pompous style was also favored by ] and ]"<ref>{{cite news | |||

| |first = Inga | |||

| |last = Saffron | |||

| |title = Monument to Democracy, The National World War II Memorial deserves its prominent location in Washington, as a tribute to heroes and a great cause | |||

| |work= ] | |||

| |page = E01 | |||

| |date = May 28, 2004 | |||

| }}</ref> (see ]). | |||

| The monument was dismissed by one prominent architecture critic as "knee-jerk ]".<ref>{{cite news |last1=Ouroussoff |first1=Nicolai |author-link=Nicolai Ouroussoff |title=Get Me Rewrite: A New Monument to Press Freedom |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/11/arts/design/11arch.html?_r=1 |access-date=8 February 2024 |work=The New York Times |date=April 11, 2008 |archive-date=September 11, 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180911232257/https://www.nytimes.com/2008/04/11/arts/design/11arch.html?_r=1 |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| The design unveiled by President Bill Clinton included 50 columns honoring the 48 states of the Union during World War II and two of the eight non-state jurisdictions at the time of the war: the territories of Alaska and Hawaii that subsequently were admitted into the Union. On June 2, 1997, the ] approved a ]<ref>{{Cite web |url=http://www.oslpr.org/legislatura/buscar97/tl_busca_avanzada.asp |title=Sistema de Información de Trámite Legislativo |website=www.oslpr.org |access-date=April 28, 2019 |archive-date=April 27, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190427211742/http://www.oslpr.org/legislatura/buscar97/tl_busca_avanzada.asp |url-status=live }}</ref> requesting the addition of a column honoring the territory of Puerto Rico's participation in the war effort. Its author, Sen. ], began a lobbying campaign. Eventually, the number of columns was raised to 56, honoring the 48 states, the District of Columbia, and the seven U.S. territories at the time: Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the Philippines,<ref>The Philippines are no longer a territory after they were granted independence from the United States in 1946. {{Cite book |last1=Schirmer |first1=Daniel B. |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=TXE73VWcsEEC |title=The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance |last2=Shalom |first2=Stephen Rosskamm |date=1987 |publisher=South End Press |isbn=978-0-89608-275-5 |language=en}}</ref> and the United States Virgin Islands.<ref>The ] were not designated as a territory until three decades later in 1975. {{Cite web |date=2015-06-11 |title=Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands |url=https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/cnmi |access-date=2022-08-15 |website=www.doi.gov |language=en |archive-date=August 2, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230802004151/https://doi.gov/oia/islands/cnmi |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| Additionally, some questioned the decision to designate the circle of pillars with the names of the U.S. states, as statehood was irrelevant to the federal war effort. | |||

| ===FDR's D-Day prayer=== | |||

| On May 23, 2013, Senator ] introduced the World War II Memorial Prayer Act of 2013 ({{USPL|113|123}}), which would direct the ] to install at the World War II memorial a suitable plaque or an inscription with the words that President ] prayed with the United States on June 6, 1944, the morning of ].<ref name=1044sum>{{cite web |title=S. 1044 – Summary |url=https://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/1044 |publisher=United States Congress |access-date=June 23, 2014 |archive-date=July 16, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140716104425/https://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/1044/ |url-status=live }}</ref> The bill was opposed by the ], the ], ], the ], and the ].<ref name=ACLUletteropposed>{{cite web |title=Letter to Chairman Udall and Ranking Member Portman |url=https://www.aclu.org/files/assets/2013-07-29_-_joint_letter_re_s1044.pdf |publisher=American Civil Liberties Union |access-date=June 23, 2014 |date=July 29, 2013 |archive-date=August 13, 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130813165530/http://www.aclu.org/files/assets/2013-07-29_-_joint_letter_re_s1044.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> Together the organizations argued that the bill "endorses the false notion that all veterans will be honored by a war memorial that includes a prayer proponents characterize as reflecting our country's 'Christian heritage and values.'"<ref name="ACLUletteropposed"/> The organizations argued that "the memorial, as it currently stands, appropriately honors those who served and encompasses the entirety of the war" and was carefully created, so no additional elements, such as FDR's prayer, need to be added.<ref name="ACLUletteropposed"/> But, they said, "the effect of this bill, however, is to co-opt religion for political purposes, which harms the beliefs of everyone."<ref name="ACLUletteropposed"/> The bill was signed into law on June 30, 2014,<ref name=1044allactions>{{cite web |title=S. 1044 – All Actions |url=https://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/1044/all-actions |publisher=United States Congress |access-date=June 23, 2014 |archive-date=July 14, 2014 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140714115836/https://beta.congress.gov/bill/113th-congress/senate-bill/1044/all-actions |url-status=live }}</ref> and the Commission of Fine Arts preferred a design at the Circle of Remembrance to the northwest of the memorial.<ref name=":0">{{Cite web |date=July 13, 2017 |title=Project Synopsis July 2017 |url=https://www.ncpc.gov/files/projects/2017/7727_Project_Synopsis_Jul2017.pdf |access-date=November 21, 2017 |publisher=National Capital Planning Commission |archive-date=December 5, 2017 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171205182409/https://www.ncpc.gov/files/projects/2017/7727_Project_Synopsis_Jul2017.pdf |url-status=live }}</ref> With funding secured, it was initially intended to be dedicated on June 6, 2022,<ref>{{Cite news |last=Ruane |first=Michael E. |title=FDR's moving fireside D-Day prayer to be added to World War II Memorial |language=en-US |newspaper=Washington Post |url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/10/15/fdr-dday-fireside-chat-prayer/ |access-date=2021-03-13 |issn=0190-8286 |archive-date=November 28, 2020 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20201128233854/https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2020/10/15/fdr-dday-fireside-chat-prayer/ |url-status=live }}</ref> but was instead opened a year later on June 6, 2023 on the 79th anniversary of the Normandy landings.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Gromelski |first=Joe |date=June 6, 2023 |title=FDR's D-Day prayer is now a part of the National World War II Memorial |url=https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2023-06-06/d-day-anniversary-fdr-memorial-10356557.html |access-date=2023-06-07 |website=Stars and Stripes |language=en |archive-date=June 8, 2023 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230608030655/https://www.stripes.com/veterans/2023-06-06/d-day-anniversary-fdr-memorial-10356557.html |url-status=live }}</ref> | |||

| ==Gallery== | ==Gallery== | ||

| <gallery |

<gallery mode="packed" heights="150"> | ||

| Image:WWII Memorial Pacific.jpg|The southern end of the memorial, dedicated to the ] | Image:WWII Memorial Pacific.jpg|The southern end of the memorial, dedicated to the ] | ||

| Image:WWII Memorial Atlantic.jpg|The northern end of the memorial, dedicated to the ] | Image:WWII Memorial Atlantic.jpg|The northern end of the memorial, dedicated to the ] | ||

| Image:"The Price of Freedom", Wash., D.C. IMG_4651.JPG|"The Price of Freedom" | Image:"The Price of Freedom", Wash., D.C. IMG_4651.JPG|"The Price of Freedom" | ||

| Image:Kilroy Was Here - Washington DC WWII Memorial - Jason Coyne.jpg|Engraving of ] on the memorial | Image:Kilroy Was Here - Washington DC WWII Memorial - Jason Coyne.jpg|Engraving of ] on the memorial | ||

| Image:WW2memorial.jpg|Close up |

Image:WW2memorial.jpg|Close up of the engraving at the memorial | ||

| Image:WashingtonWW2MemorialInWinter.jpg|The memorial, looking east in winter | |||

| Image:NWW2M Pacific arch.JPG|The Pacific Arch | Image:NWW2M Pacific arch.JPG|The Pacific Arch | ||

| Image:World War II Memorial, 04950v.jpg|The Atlantic side of the memorial at dusk. | |||

| Image:WWII Seal.JPG|A seal on the floor of the memorial using the ] design | Image:WWII Seal.JPG|A seal on the floor of the memorial using the ] design | ||

| Image:World War 2 Memorial.jpg|Each of the 4,048 gold stars represents 100 Americans who died during the war | Image:World War 2 Memorial.jpg|Each of the 4,048 gold stars represents 100 Americans who died during the war | ||

| Image:WWII_Mem_and_Washington_Monument.jpg|Five state pillars and flag, Washington Monument | |||

| Image:Pacific_Arch_WWII_Mem.jpg|The Pacific Arch (Atlantic Arch in the background) | Image:Pacific_Arch_WWII_Mem.jpg|The Pacific Arch (Atlantic Arch in the background) | ||

| Image:World War II Memorial Pacific-Bas Reliefs Navy In Action.jpg|World War II Memorial Pacific-Bas Reliefs Navy In Action | |||

| Image:Atlantic_Arch_WWII_Mem.jpg|The Atlantic Arch | Image:Atlantic_Arch_WWII_Mem.jpg|The Atlantic Arch | ||

| Image:View of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. from the "Atlantic" arch of the memorial..jpg|View of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. from the Atlantic Arch of the memorial. | |||

| Image:USA-World War II Memorial0.jpg|World War II Memorial (2013) | |||

| National World War II Memorial drained for maintenance, 1 February 2024.jpg|World War II Memorial in February 2024 with the fountain drained for maintenance, looking towards the Atlantic Arch | |||

| Image:WW2Memorial.JPG|Panoramic view at night, ] in the background | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===With the Washington Monument in background=== | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="250"> | |||

| Image:WashingtonWW2MemorialInWinter.jpg|The memorial, looking east in winter | |||

| Image:WWII_Mem_and_Washington_Monument.jpg|Five state pillars and flag | |||

| Image:Wwiimemorialnc.jpg|North Carolina pillar | |||

| Image:WWII Memorial with Washington Monument.jpg|Pennsylvania pillar | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ===Of the Central Fountain=== | |||

| <gallery mode="packed" heights="250"> | |||

| Image:WWII_Mem_Fountain_Atlantic.jpg|Central Fountain with the Atlantic Arch in background | Image:WWII_Mem_Fountain_Atlantic.jpg|Central Fountain with the Atlantic Arch in background | ||

| Image:World War |

Image:World War II Memorial Fountain.jpg|World War II Memorial Fountain in Washington D.C. | ||

| Image: |

Image:World_War_Two_Memorial.JPG|World War II Memorial, Fountain in the evening. | ||

| Image:View of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. from the "Atlantic" arch of the memorial..jpg|View of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. from the "Atlantic" arch of the memorial. | |||

| </gallery> | </gallery> | ||

| {{wide image|National World War II Memorial, Washington DC, July 2017 (panorama).jpg|2000px|Panoramic view|align-cap=center}} | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ], in New Orleans | |||

| *] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| Line 129: | Line 155: | ||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| {{Commons category |

{{Commons category}} | ||

| * |

* | ||

| * | * | ||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| * | |||

| {{Washington DC landmarks}} | {{Washington DC landmarks}} | ||

| {{Public art in Washington, D.C.}} | |||

| {{Protected Areas of the District of Columbia}} | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT: |

{{DEFAULTSORT:World War Ii Memorial}} | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 10:02, 20 December 2024

U.S. national memorial in Washington, D.C. For other uses, see World War II Memorial (disambiguation).

| World War II Memorial | |

|---|---|

The memorial in Washington D.C. The memorial in Washington D.C. | |

| |

| Location | Washington, D.C. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′22″N 77°2′26″W / 38.88944°N 77.04056°W / 38.88944; -77.04056 |

| Established | April 29, 2004 |

| Visitors | 4.6 million (in 2018) |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | World War II Memorial |

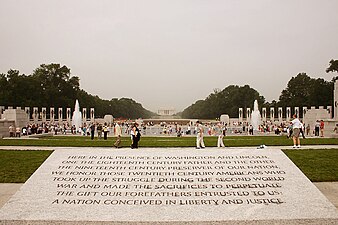

The World War II Memorial is a national memorial in the United States dedicated to Americans who served in the armed forces and as civilians during World War II. It is located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C.

The memorial consists of 56 granite pillars, decorated with bronze laurel wreaths, representing U.S. states and territories, and a pair of small triumphal arches for the Atlantic and Pacific theaters, surrounding an oval plaza and fountain. On its short axis is a memorial wall of gold stars representing the fallen, and opposite, a sloped and stepped entrance plaza leading up to the oval from 17th Street. Its initial design was submitted by Austrian-American architect Friedrich St. Florian.

Opened on April 29, 2004, it replaced the Rainbow Pool at the eastern end of the Reflecting Pool, between the Lincoln Memorial and the Washington Monument. Dedicated by President George W. Bush on May 29, 2004, the memorial is administered by the National Park Service under its National Mall and Memorial Parks group. More than 4.6 million people visited the memorial in 2018.

Overview

The memorial consists of 56 granite pillars, each 17 feet (5.2 m) tall, arranged in a semicircle around a plaza with two 43-foot (13 m) triumphal arches on opposite sides. Two-thirds of the 7.4-acre (3.0 ha) site is landscaping and water. Each pillar is inscribed with the name of one of the 48 U.S. states of 1945, as well as the District of Columbia, the Alaska Territory and Territory of Hawaii, the Commonwealth of the Philippines, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The northern arch is inscribed with "Atlantic"; the southern one, "Pacific." The plaza is 337 ft 10 in (102.97 m) long and 240 ft 2 in (73.20 m) wide, is sunk 6 feet (1.8 m) below grade, and contains a pool that is 246 feet 9 inches by 147 feet 8 inches (75.2 m × 45.0 m).

The memorial includes two inconspicuously located "Kilroy was here" engravings. Their inclusion in the memorial acknowledges the significance of the symbol to American soldiers during World War II and how it represented their presence and protection wherever it was inscribed.

On approaching the semicircle from the east, a visitor walks along one of two walls (right side wall and left side wall) picturing scenes of the war experience in bas relief. As one approaches on the left (toward the Pacific arch), the scenes begin with soon-to-be servicemen getting physical exams, taking the oath, and being issued military gear. The reliefs progress through several iconic scenes, including combat and burying the dead, ending in a homecoming scene. On the right-side wall (toward the Atlantic arch) there is a similar progression, but with scenes generally more typical of the European theatre. Some scenes take place in England, depicting the preparations for air and sea assaults. The last scene is of a handshake between the American and Russian armies when the western and eastern fronts met in Germany.

Wall of stars

The Freedom Wall is on the west side of the plaza, with a view of the Reflecting Pool and Lincoln Memorial behind it. The wall has 4,048 gold stars, each representing 100 Americans who died in the war. In front of the wall lies the message "Here we mark the price of freedom".

History

In 1987, World War II veteran Roger Durbin approached Representative Marcy Kaptur, a Democrat from Ohio, to ask if a World War II memorial could be constructed. Kaptur introduced the World War II Memorial Act to the House of Representatives as HR 3742 on December 10. The resolution authorized the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC) to establish a World War II memorial in "Washington, D.C., or its environs", but the bill was not voted on before the end of the session. In 1989 and 1991, Rep. Kaptur introduced similar legislation, but these bills suffered the same fate as the first and did not become law.

Kaptur reintroduced legislation in the House a fourth time as HR 682 on January 27, 1993, one day after Senator Strom Thurmond (a Republican from South Carolina) introduced companion Senate legislation. On March 17, 1993, the Senate approved the act, and the House approved an amended version of the bill on May 4. On May 12, the Senate also approved the amended bill, and the World War II Memorial Act was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on May 25 of that year, becoming Pub. L. 103–32.

Fundraising

On September 30, 1994, President Bill Clinton appointed a 12-member Memorial Advisory Board (MAB) to advise the ABMC in picking the site, designing the memorial, and raising money to build it. A direct mail fundraising effort brought in millions of dollars from individual Americans. Additional large donations were made by veterans' groups, including the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Veterans of the Battle of the Bulge. The majority of the corporate fundraising effort was led by co-chairmen Senator Bob Dole, a decorated World War II veteran and 1996 Republican nominee for president, and Frederick W. Smith, the president and chief executive officer of FedEx Corporation and a former U.S. Marine Corps officer. The U.S. federal government provided about $16 million; a total of $197 million was raised. Following his death in December 2021, Dole himself would have a memorial service held at the World War II Memorial.

Picking the site

On January 20, 1995, Colonel Kevin C. Kelley, project manager for the ABMC, organized the first meeting of the ABMC and the MAB, at which the project was discussed and initial plans made. The meeting was chaired by Commissioner F. Haydn Williams, chairman of ABMC's World War II Memorial Site and Design Committee, who would go on to guide the project through the site selection and approval process and the selection and approval of the Memorial's design. Representatives from the United States Commission of Fine Arts, the National Capital Planning Commission, the National Capital Memorial Commission, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and the National Park Service attended the meeting. The selection of an appropriate site was taken on as the first action.

Over the next months, several sites were considered. Soon, 3 quickly gained favor:

- U.S. Capitol Reflection Pool area – between 3rd Street and the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial

- Constitution Gardens – east end, between Constitution Avenue and the Rainbow Pool

- Freedom Plaza – on Pennsylvania Avenue between 14th and 15th Streets

Other sites considered but quickly rejected were:

- Tidal Basin – northeast side, east of the Tidal Basin parking lot and west of the 14th Street Bridge access road

- West Potomac Park – between Ohio Drive and the north shore of the Potomac River, northwest of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial

- Grounds of the Washington Monument – at Constitution Avenue between 14th and 15th Streets, west of the National Museum of American History

- Henderson Hall, adjacent to Arlington National Cemetery – dropped from consideration because of its unavailability

The selection of the Rainbow Pool site was announced on October 5, 1995. The design would incorporate the Rainbow Pool fountain, located across 17th Street from the Washington Monument and near the Constitution Gardens site.

The location, between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial, is the most prominent spot for a monument on the National Mall since the Lincoln Memorial opened in 1922. It is the first addition in more than 70 years to the grand corridor of open space that stretches from the Capitol 2.1 miles (3.4 km) west to the Potomac River.

Designing the memorial

A nationwide design competition drew 400 submissions from architects from around the country. Friedrich St. Florian's initial design was selected in 1997. St. Florian's design evokes a classical monument. Under each of the two memorial arches, the Pacific and Atlantic baldachinos, four eagles carry an oak laurel wreath. Each of the 56 pillars bear wreaths of oak symbolizing military and industrial strength, and of wheat, symbolizing agricultural production.

Over the next four years, St. Florian's design was altered during the review and approval process required of proposed memorials in Washington, D.C. Ambassador Haydn Williams guided the design development for ABMC.

Construction

Ground was broken in November 2000. The construction was managed by General Services Administration.

New England Stone Industries of Rhode Island was hired by the general contractor to fabricate the stone; it worked closely with St. Florian and the ABMC throughout the process. The triumphal arches were sub-contracted to and crafted by Rock of Ages Corporation. Sculptor Raymond Kaskey created the bronze eagles and two wreaths that were installed under the arches, as well as 24 bronze bas-relief panels that depict wartime scenes of combat and the home front. The bronzes were cast over the course of two and a half years at Laran Bronze in Chester, Pennsylvania. The stainless-steel armature that holds up the eagles and wreaths was designed at Laran, in part by sculptor James Peniston, and fabricated by Apex Piping of Newport, Delaware. The twin bronze wreaths decorating the 56 granite pillars around the perimeter of the memorial – as well as the 4,048 gold-plated silver stars representing American military deaths in the war – were cast at Valley Bronze in Joseph, Oregon. "I'd see buckets full of the stars going through the foundry, and think that each stood for 100 men. The magnitude was overwhelming," Dave Jackman, former president of Valley Bronze, recalled in 2004.

The John Stevens Shop designed the lettering for the memorial and most of the inscriptions were hand-carved in situ.

The memorial opened to the public on April 29, 2004, and was dedicated in a May 29 ceremony attended by thousands of people. The memorial became a unit of the national park system on November 1, when authority over it was transferred to the National Park Service.

Controversy

Criticism of the location

Critics such as the National Coalition to Save Our Mall opposed the location of the memorial. A major criticism of the location was that it would interrupt what had been an unbroken view between the Washington Monument and the Lincoln Memorial. The memorial was also criticized for taking up open space that had been historically used for major demonstrations and protests.

Critics were particularly bothered by the expedited approval process, which is considerably lengthy most of the time. The United States Congress, worried that World War II veterans were dying before an appropriate memorial could be built, passed legislation exempting the World War II Memorial from further site and design review. Congress also dismissed pending legal challenges to the memorial.

Criticism of the design and style

There were also aesthetic objections to the design. A critic from the Boston Herald described the monument as "vainglorious, demanding of attention and full of trite imagery." The Philadelphia Inquirer argued that "this pompous style was also favored by Hitler and Mussolini" The Washington Post described it as "overbearing", "bombastic", and a "hodgepodge of cliche and Soviet-style pomposity" with "the emotional impact of a slab of granite".

The monument was dismissed by one prominent architecture critic as "knee-jerk historicism".

The design unveiled by President Bill Clinton included 50 columns honoring the 48 states of the Union during World War II and two of the eight non-state jurisdictions at the time of the war: the territories of Alaska and Hawaii that subsequently were admitted into the Union. On June 2, 1997, the Puerto Rico Legislative Assembly approved a Concurrent Resolution requesting the addition of a column honoring the territory of Puerto Rico's participation in the war effort. Its author, Sen. Kenneth McClintock, began a lobbying campaign. Eventually, the number of columns was raised to 56, honoring the 48 states, the District of Columbia, and the seven U.S. territories at the time: Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, Guam, American Samoa, the Philippines, and the United States Virgin Islands.

FDR's D-Day prayer

On May 23, 2013, Senator Rob Portman introduced the World War II Memorial Prayer Act of 2013 (Pub. L. 113–123 (text) (PDF)), which would direct the Secretary of the Interior to install at the World War II memorial a suitable plaque or an inscription with the words that President Franklin D. Roosevelt prayed with the United States on June 6, 1944, the morning of D-Day. The bill was opposed by the American Civil Liberties Union, the American Jewish Committee, Americans United for Separation of Church and State, the Hindu American Foundation, and the Interfaith Alliance. Together the organizations argued that the bill "endorses the false notion that all veterans will be honored by a war memorial that includes a prayer proponents characterize as reflecting our country's 'Christian heritage and values.'" The organizations argued that "the memorial, as it currently stands, appropriately honors those who served and encompasses the entirety of the war" and was carefully created, so no additional elements, such as FDR's prayer, need to be added. But, they said, "the effect of this bill, however, is to co-opt religion for political purposes, which harms the beliefs of everyone." The bill was signed into law on June 30, 2014, and the Commission of Fine Arts preferred a design at the Circle of Remembrance to the northwest of the memorial. With funding secured, it was initially intended to be dedicated on June 6, 2022, but was instead opened a year later on June 6, 2023 on the 79th anniversary of the Normandy landings.

Gallery

-

The southern end of the memorial, dedicated to the Pacific theater

The southern end of the memorial, dedicated to the Pacific theater

-

The northern end of the memorial, dedicated to the Atlantic theater

The northern end of the memorial, dedicated to the Atlantic theater

-

"The Price of Freedom"

-

Engraving of Kilroy on the memorial

Engraving of Kilroy on the memorial

-

Close up of the engraving at the memorial

Close up of the engraving at the memorial

-

The Pacific Arch

-

The Atlantic side of the memorial at dusk.

The Atlantic side of the memorial at dusk.

-

A seal on the floor of the memorial using the World War II Victory Medal design

-

Each of the 4,048 gold stars represents 100 Americans who died during the war

Each of the 4,048 gold stars represents 100 Americans who died during the war

-

The Pacific Arch (Atlantic Arch in the background)

The Pacific Arch (Atlantic Arch in the background)

-

World War II Memorial Pacific-Bas Reliefs Navy In Action

World War II Memorial Pacific-Bas Reliefs Navy In Action

-

The Atlantic Arch

The Atlantic Arch

-

View of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. from the Atlantic Arch of the memorial.

View of the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C. from the Atlantic Arch of the memorial.

-

World War II Memorial (2013)

World War II Memorial (2013)

-

World War II Memorial in February 2024 with the fountain drained for maintenance, looking towards the Atlantic Arch

World War II Memorial in February 2024 with the fountain drained for maintenance, looking towards the Atlantic Arch

-

Panoramic view at night, Washington Monument in the background

With the Washington Monument in background

-

The memorial, looking east in winter

The memorial, looking east in winter

-

Five state pillars and flag

Five state pillars and flag

-

North Carolina pillar

North Carolina pillar

-

Pennsylvania pillar

Pennsylvania pillar

Of the Central Fountain

-

Central Fountain with the Atlantic Arch in background

Central Fountain with the Atlantic Arch in background

-

World War II Memorial Fountain in Washington D.C.

World War II Memorial Fountain in Washington D.C.

-

World War II Memorial, Fountain in the evening.

Panoramic view

Panoramic view

See also

- List of national memorials of the United States

- List of public art in Washington, D.C., Ward 2

- The National WWII Museum, in New Orleans

- Architecture of Washington, D.C.

Notes

- Many sources give the number of stars as 4,000. The wall contains 23 panels of 11 columns and 16 rows of stars. The number of stars can also be counted in Image:Wwii memorial stars march 2006.jpg. See also discussion at Talk:National World War II Memorial#Number the Stars.

References

- "Public Law 103-32" (PDF). uscode.house.gov. May 25, 1993. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- "16 U.S. Code Subchapter LXI – National and International Monuments and Memorials". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2015.

- "WWII Memorial". www.wwiimemorial.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2023. Retrieved June 12, 2008.

- "World War II Memorial (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on November 5, 2010. Retrieved April 11, 2005.

- "Stats Report Viewer: World War II Memorial". irma.nps.gov. Archived from the original on June 24, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2019.

- "Memorial Design". National WWII Memorial. Archived from the original on May 31, 2008. Retrieved July 16, 2008.

- "Kilroy Was Here, World War II Memorial, Washington, D.C. – Kilroy Was Here on Waymarking.com". www.waymarking.com. Archived from the original on January 27, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- "Kilroy Is Here – Can You Find Him?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- Knight, Christopher (May 23, 2004). "A memorial to forget". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2005.

- "Timeline - WWII Memorial Registry". Archived from the original on September 28, 2023. Retrieved September 27, 2023.

- King, Ledyard; Morin, Rebecca; Lee, Ella (December 10, 2021). "Bob Dole hailed as war hero and 'Kansas' favorite son' at Washington funeral service". USA Today. Archived from the original on May 16, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- NBC News (December 10, 2021). "Bob Dole Honored At World War II Memorial". YouTube. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- Forgey, Benjamin (July 1, 1995). "Site-seeking at the Mall: Placing World War II memorial in the grand scheme of things". The Washington Post. p. C1.

- Forgey, Benjamin (July 28, 1995). "No Accord on WWII Memorial; Two Agencies Send Mixed Signals About Location". The Washington Post. p. B3.

- Forgey, Benjamin (October 6, 1995). "WWII Memorial Gets Choice Mall Site; 2nd Panel Approves Location, Clearing Way for Design Phase". The Washington Post. p. B1.

- Krueger, Colleen (November 9, 1995). "World War II memorial moves toward reality : Officials have agreed on a prominent site on the National Mall. Fund raising is the next task for sponsors". Archived from the original on September 23, 2016. Retrieved September 23, 2016 – via LA Times.

- WWII Memorial: The “High Point” of Raymond Kaskey’s Career – Carnegie Mellon Today Archived April 7, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "WWII Memorial". Retrieved September 9, 2009.

- "James Peniston Sculpture: Bio". Archived from the original on July 25, 2008. Retrieved September 9, 2008.

- "Building the Memorial". Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved June 22, 2016.

- "Projects". Valley Bronze of Oregon. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Leonard, Larry. "Oregon Magazine". www.oregonmag.net. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- "Bronze from Joseph part of WWII monument". Wallowa County Chieftain. Archived from the original on September 23, 2018. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- Wheeler, Linda; Hsu, Spencer S. (May 17, 2001). "Bush Backs War Memorial". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 5, 2019. Retrieved November 5, 2019 – via nationalmallcoalition.org.

- Fisher, Marc (May 4, 2004). "A Memorial That Doesn't Measure Up". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved November 5, 2011.

- "The World War II Memorial Defaces a National Treasure". National Coalition to Save Our Mall. January 2001. Archived from the original on May 4, 2007. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Van Oss, Alex (February 25, 2001). "World War II Memorial" (RealAudio). Weekend Edition Sunday. National Public Radio. Archived from the original on March 8, 2007. Retrieved June 2, 2007.

- Killian, Michael (May 22, 2001). "Senate OKs WWII Memorial". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007.

- Keane, Thomas M. Jr. (June 25, 2004). "WWII Memorial fails both past, present". Boston Herald. p. 27. Archived from the original on January 31, 2013.

- Saffron, Inga (May 28, 2004). "Monument to Democracy, The National World War II Memorial deserves its prominent location in Washington, as a tribute to heroes and a great cause". The Philadelphia Inquirer. p. E01.

- Fisher, Marc (May 4, 2004). "A Memorial That Doesn't Measure Up". The Washington Post. p. B01. Retrieved October 24, 2024.

- Ouroussoff, Nicolai (April 11, 2008). "Get Me Rewrite: A New Monument to Press Freedom". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 11, 2018. Retrieved February 8, 2024.

- "Sistema de Información de Trámite Legislativo". www.oslpr.org. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- The Philippines are no longer a territory after they were granted independence from the United States in 1946. Schirmer, Daniel B.; Shalom, Stephen Rosskamm (1987). The Philippines Reader: A History of Colonialism, Neocolonialism, Dictatorship, and Resistance. South End Press. ISBN 978-0-89608-275-5.

- The Northern Mariana Islands were not designated as a territory until three decades later in 1975. "Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands". www.doi.gov. June 11, 2015. Archived from the original on August 2, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- "S. 1044 – Summary". United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 16, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- ^ "Letter to Chairman Udall and Ranking Member Portman" (PDF). American Civil Liberties Union. July 29, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 13, 2013. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- "S. 1044 – All Actions". United States Congress. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved June 23, 2014.

- "Project Synopsis July 2017" (PDF). National Capital Planning Commission. July 13, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved November 21, 2017.

- Ruane, Michael E. "FDR's moving fireside D-Day prayer to be added to World War II Memorial". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Archived from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved March 13, 2021.

- Gromelski, Joe (June 6, 2023). "FDR's D-Day prayer is now a part of the National World War II Memorial". Stars and Stripes. Archived from the original on June 8, 2023. Retrieved June 7, 2023.

External links

- NPS – National World War II Memorial

- Trust for the National Mall: World War II Memorial

- White House dedication

- World War II Memorial Gallery

| Protected areas of the District of Columbia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

- 2004 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- 2004 sculptures

- Artworks in the collection of the National Park Service

- Fountains in Washington, D.C.

- Monuments and memorials in Washington, D.C.

- National Mall

- National Mall and Memorial Parks

- National memorials of the United States

- World War II memorials in the United States

- Washington, D.C., in World War II