| Revision as of 11:13, 2 June 2006 editRl (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Pending changes reviewers11,135 edits →Causes: fmt← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:48, 5 January 2025 edit undoPanamitsu (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users70,839 editsm add {{Use American English}} templateTag: AWB | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|1919 accident in Massachusetts, United States}} | |||

| ] | |||

| {{Pp-pc1}} | |||

| The '''Boston Molasses Disaster''' (also known as the '''Great Molasses Flood''' or '''The Great Boston Molasses Tragedy''') occurred on ], ], in the ] neighborhood of ], ]. A large ] (treacle) tank burst and a wave of molasses ran through the streets at an estimated 35 ] (56 ]), killing twenty-one and injuring 150 others. The event has entered local folklore, and residents claim that the area still sometimes smells of molasses. | |||

| {{Use American English|date=January 2025}} | |||

| {{Use mdy dates|date=January 2019}} | |||

| {{Infobox event | |||

| | title = Great Molasses Flood | |||

| | image = BostonMolassesDisaster.jpg | |||

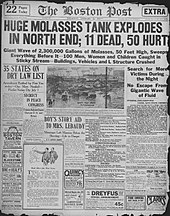

| | caption = The wreckage of the collapsed tank is visible in background, center, next to the light-colored warehouse | |||

| | date = {{start date and age|1919|01|15}} | |||

| | time = Approximately 12:30 pm | |||

| | place = ], U.S. | |||

| | coordinates = {{coord|42|22|06.6|N|71|03|21.2|W|type:event_scale:20000_region:US-MA|display=inline,title}} | |||

| | cause = ] failure | |||

| | reported deaths = 21 | |||

| | reported injuries = 150 injured | |||

| }} | |||

| The '''Great Molasses Flood''', also known as the '''Boston Molasses Disaster''',<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.brighthub.com/education/homework-tips/articles/86176.aspx |title=The Boston Molasses Disaster: Causes of the Molasses Tank Explosion |last=Hinrichsen |first=Erik |date=8 September 2010 |website=Bright Hub |language=en |access-date=March 5, 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |url=http://beaconhilltimes.com/2018/04/06/molasses-disaster-featured-at-evening-at-74/ |title='Molasses Disaster' Featured at Evening at 74 |website=Beacon Hill Times |access-date=March 5, 2019}}</ref>{{efn|The flood has more recently been known as the "Boston Molassacre".<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://americacomesalive.com/the-boston-molassacre/ |title=The 'Boston Molassacre' |last=Kelly |first=Kate |website=America Comes Alive |date=January 8, 2012 |language=en |access-date=October 3, 2021}}</ref>}} was a disaster that occurred on Wednesday, January 15, 1919, in the ] neighborhood of ], ]. | |||

| A large storage tank filled with {{convert|2.3|e6usgal|m3|abbr=off|sp=us}}<ref>{{Cite news |url=https://www.scmp.com/news/world/united-states-canada/article/2182032/great-molasses-flood-us-marks-100-years-deadly-wave |title=Great Molasses Flood: US marks 100 years since deadly wave of treacle trashed part of Boston |date=January 14, 2019 |work=] |access-date=March 18, 2019 |agency=]}}</ref> of ], weighing approximately{{efn|At {{cvt|1.4|kg/L}}, {{cvt|8,700|m3}} of molasses weighs {{convert|12180|t}}.}} {{convert|12000|t|ST|order=flip|abbr=off|sp=us}} burst, and the resultant wave of molasses rushed through the streets at an estimated {{convert|35|mph|kph|abbr=off|sp=us}}, killing 21 people and injuring 150.<ref name="Sohn">{{Cite web |url=https://www.history.com/news/great-molasses-flood-science |title=Why the Great Molasses Flood Was So Deadly |last=Sohn |first=Emily |date=January 15, 2019 |department=] |publisher=] |language=en |access-date=January 16, 2019}}</ref> The event entered local folklore and residents reported for decades afterwards that the area still smelled of molasses on hot summer days.<ref name="Sohn" /><ref name=Smithsonian /> | |||

| == Flood == | |||

| ] | |||

| Molasses can be fermented to produce ], the active ingredient in alcoholic beverages and a key component in munitions.<ref name="DarkTide" />{{rp|11}} The disaster occurred at the ] facility at 529{{nbs}}Commercial Street near Keany Square. A considerable amount of molasses had been stored there by the company, which used the harborside Commercial Street tank to offload molasses from ships and store it for later transfer by pipeline to the Purity ethanol plant situated between Willow Street and Evereteze Way in ]. The molasses tank stood {{convert|50|ft|m|abbr=off|sp=us}} tall and {{cvt|90|ft|m}} in diameter, and contained as much as {{convert|2.3|e6USgal|m3|abbr=unit}}. | |||

| ] | |||

| On January 15, 1919, temperatures in Boston had risen above {{convert|40|F|C|abbr=off|sp=us}}, climbing rapidly from the frigid temperatures of the preceding days,<ref name=DarkTide />{{rp|91, 95}} and the previous day, a ship had delivered a fresh load of molasses, which had been warmed to decrease its viscosity for transfer.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.wbur.org/radioboston/2019/01/15/1919-molasses-flood |title=100 Years Later: Lessons From Boston's Molasses Flood Of 1919 |website=www.wbur.org|date=January 15, 2019 }}</ref> Possibly due to the thermal expansion of the older, colder molasses already inside the tank, the tank burst open and collapsed at approximately 12:30{{nbs}}p.m. Witnesses reported that they felt the ground shake and heard a roar as it collapsed, a long rumble similar to the passing of ]; others reported a tremendous crashing, a deep growling, "a thunderclap-like {{em|bang!}}", and a sound like a machine gun as the ]s shot out of the tank.<ref name=DarkTide />{{rp|92–95}} | |||

| The density of molasses is about {{convert|1.4|t/m3|lb/USgal|abbr=off|sp=us}}, 40 percent more dense than water, resulting in the molasses having a great deal of ].<ref name="nbc 100" /> The collapse translated this energy into a wave of molasses {{cvt|25|ft|m|0}} high at its peak,<ref name="SciAmJabr" /> moving at {{cvt|35|mph|kph}}.<ref name="Sohn" /><ref name="Smithsonian" /> The wave was of sufficient force to drive steel panels of the burst tank against the girders of the adjacent Boston Elevated Railway's ] structure<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://edp.org/molpark.htm |title=Without Warning, Molasses in January Surged Over Boston |last=Park |first=Edwards |date=December 19, 2018 |website=edp.org |access-date=March 24, 2019 |quote=magine an estimated 14,000 tons of the thick, sticky fluid running wild. It left the ruptured tank in a choking brown wave, 15 feet high, wiping out everything that stood in its way. One steel section of the tank was hurled across Commercial Street, neatly knocking out one of the uprights supporting the El.}}</ref> and tip a streetcar momentarily off the El's tracks. Stephen Puleo describes how nearby buildings were swept off their foundations and crushed. Several blocks were flooded to a depth of {{cvt|2|to|3|ft|cm|sigfig=1|abbr=off|sp=us}}. Puleo quotes a ''Boston Post'' report: | |||

| {{quote|quote=Molasses, waist deep, covered the street and swirled and bubbled about the wreckage{{nbsp}} Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was{{nbsp}} Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared. Human beings—men and women—suffered likewise.<ref name=DarkTide />{{rp|98}}}} | |||

| The '']'' reported that people "were picked up by a rush of air and hurled many feet". Others had debris hurled at them from the rush of sweet-smelling air. A truck was picked up and hurled into ]. After the initial wave, the molasses became viscous, exacerbated by the cold temperatures, trapping those caught in the wave and making it even more difficult to rescue them.<ref name="nbc 100" /> About 150 people were injured, and 21 people and several horses were killed. Some were crushed and drowned by the molasses or by the debris that it carried within.<ref name="Buell">{{Cite web |url=https://www.bostonmagazine.com/news/2019/01/12/great-boston-molasses-flood-things-you-didnt-know/ |title=Anarchists, Horses, Heroes: 12 Things You Didn't Know about the Great Boston Molasses Flood |last=Buell |first=Spencer |date=January 12, 2019 |website=Boston Magazine |language=en-US |access-date=January 14, 2019}}</ref> The wounded included people, horses, and dogs; coughing fits became one of the most common ailments after the initial blast. Edwards Park wrote of one child's experience in a 1983 article for ''Smithsonian'': | |||

| {{quote|quote=Anthony di Stasio, walking homeward with his sisters from the Michelangelo School, was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing. Then he grounded and the molasses rolled him like a pebble as the wave diminished. He heard his mother call his name and couldn't answer, his throat was so clogged with the smothering goo. He passed out, then opened his eyes to find three of his four sisters staring at him.<ref name=Smithsonian />}} | |||

| == Aftermath == | |||

| ] | |||

| First to the scene were 116 cadets under the direction of Lieutenant Commander H. J. Copeland from {{USS|Nantucket|IX-18|6}}, a training ship of the Massachusetts Nautical School (now the ]) that was docked nearby at the playground pier.<ref name="NYTimes1919" /> The cadets ran several blocks toward the accident and entered into the knee-deep flood of molasses to pull out the survivors, while others worked to keep curious onlookers from getting in the way of the rescuers. The Boston Police, Red Cross, Army, and Navy personnel soon arrived. Some nurses from the Red Cross dove into the molasses, while others tended to the injured, keeping them warm and feeding the exhausted workers. Many of these people worked through the night, and the injured were so numerous that doctors and surgeons set up a makeshift hospital in a nearby building. Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims, and four days elapsed before they stopped searching; many of the dead were so glazed over in molasses that they were hard to recognize.<ref name="Smithsonian" /> Other victims were swept into Boston Harbor and were found three to four months after the disaster.<ref name="Buell" /> | |||

| In the wake of the accident, 119 residents brought a ] against the ] (USIA),<ref>{{Cite web |last=Andrews |first=Evan |date=2023-05-16 |title=The Great Molasses Flood of 1919 |url=https://www.history.com/news/the-great-molasses-flood-of-1919 |access-date=2023-12-01 |website=HISTORY |language=en}}</ref> which had bought Purity Distilling in 1917. It was one of the first class-action suits in Massachusetts and is considered a milestone in paving the way for modern corporate regulation.<ref name="Betancourt">{{Cite news |url=https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2019/jan/13/the-great-boston-molasses-flood-why-it-matters-modern-regulation |title=The Great Boston Molasses Flood: why the strange disaster matters today |last=Betancourt |first=Sarah |date=January 13, 2019 |work=] |access-date=January 14, 2019 |language=en-GB |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> The company claimed that the tank had been blown up by anarchists<ref name="DarkTide" />{{rp|165}} because some of the alcohol produced was to be used in making munitions, but a court-appointed auditor found USIA responsible after three years of hearings, and the company ultimately paid out $628,000 in damages<ref name="Betancourt" /> (${{Format price|{{Inflation|US|628000|1919}}}} in {{Inflation/year|US}}, adjusted for inflation{{Inflation/fn|US}}). Relatives of those killed reportedly received around $7,000 per victim (equivalent to ${{Inflation|US|7000|1919|r=-3|fmt=c}} in {{Inflation/year|US}}).<ref name="Smithsonian" /> | |||

| === Cleanup === | |||

| Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the molasses and sand to absorb it,<ref name="TheHour" /> and the harbor was brown with molasses until summer.<ref name="HistoryChannel" /> The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks,<ref name="YankeeMason" /> with several hundred people contributing to the effort,<ref name="DarkTide" />{{rp|132–134, 139}}<ref name="Betancourt" /> and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes,<ref name="Smithsonian" /><ref name="DarkTide" />{{rp|139}} and to countless other places. It was reported that "Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky."<ref name="Smithsonian" /> | |||

| === Fatalities === | |||

| ] | |||

| {|class="wikitable sortable" | |||

| |- | |||

| !Name!!Age!!Occupation | |||

| |- | |||

| |Patrick Breen||44||Laborer (North End Paving Yard) | |||

| |- | |||

| |William Brogan||61||Teamster | |||

| |- | |||

| |Bridget Clougherty||65||Homemaker | |||

| |- | |||

| |Stephen Clougherty||34||Unemployed | |||

| |- | |||

| |John Callahan||43||Paver (North End Paving Yard) | |||

| |- | |||

| |Maria Di Stasio||10||Child | |||

| |- | |||

| |William Duffy||58||Laborer (North End Paving Yard) | |||

| |- | |||

| |Peter Francis||64||Blacksmith (North End Paving Yard) | |||

| |- | |||

| |Flaminio Gallerani||37||Driver | |||

| |- | |||

| |Pasquale Iantosca||10||Child | |||

| |- | |||

| |James J. Kenneally||48||Laborer (North End Paving Yard) | |||

| |- | |||

| |Eric Laird||17||Teamster | |||

| |- | |||

| |George Layhe||38||Firefighter (Engine 31) | |||

| |- | |||

| |James Lennon||64||Teamster/Motorman | |||

| |- | |||

| |Ralph Martin||21||Driver | |||

| |- | |||

| |James McMullen||46||Foreman, Bay State Express | |||

| |- | |||

| |Cesar Nicolo||32||Expressman | |||

| |- | |||

| |Thomas Noonan||43||Longshoreman | |||

| |- | |||

| |Peter Shaughnessy||18||Teamster | |||

| |- | |||

| |John M. Seiberlich||69||Blacksmith (North End Paving Yard) | |||

| |- | |||

| |Michael Sinnott||78||Messenger | |||

| |- class="sortbottom" | |||

| | colspan="3" style="text-align: center;" | <ref name=DarkTide />{{rp|239}}<ref name="NYTimes1919" /><ref>{{Cite news |last=Dwyer |first=Dialynn |date=January 13, 2019 |title='There was no escape from the wave': These are the 21 victims of the Great Boston Molasses Flood |url=https://www.boston.com/news/history/2019/01/13/victims-great-boston-molasses-flood-1919 |work=] |access-date=2019-01-14 |language=en-US}}</ref> | |||

| |} | |||

| == Causes == | |||

| ] | |||

| Several factors might have contributed to the disaster. The first factor is that the tank may have leaked from the very first day that it was filled in 1915.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Barry |first=Quan |title=Controvertibles |date=2004-09-26 |publisher=University of Pittsburgh Press |isbn=978-0-8229-8015-5 |doi=10.2307/j.ctt5vkg3w}}</ref><ref>Birnbaum, Amy. (2019). The Great Molasses Flood: A bizarre disaster struck one of America's biggest cities 100 years ago. Scholastic News (Explorer Ed.), 81(11), 4.</ref> The tank was also constructed poorly and tested insufficiently, and carbon dioxide production might have raised the internal pressure due to fermentation in the tank. Warmer weather the previous day would have assisted in building this pressure, as the air temperature rose from {{convert|2|to|41|F|C|sigfig=2}} over that period. The failure occurred from a manhole cover near the base of the tank, and a ] crack there possibly grew to the point of criticality. | |||

| The tank had been filled to capacity only eight times since it was built a few years previously, putting the walls under an intermittent, cyclical load. Several authors say that the Purity Distilling Company was trying to out-race prohibition,<ref name="PuleoQuote79" /><ref name="YankeeStanley" /><ref name="Silverman" /> as the ] was ratified the next day (January 16, 1919) and took effect one year later.<ref name="Streissguth" /> An inquiry after the disaster revealed that Arthur Jell, USIA's treasurer, neglected basic safety tests while overseeing construction of the tank, such as filling it with water insufficient to check for leaks, and ignored warning signs such as groaning noises each time the tank was filled. He had no architectural or engineering experience.<ref name="Sohn" /><ref name="nbc 100" /> When filled with molasses, the tank leaked so badly that it was painted brown to hide the leakage. Local residents collected leaked molasses for their homes.<ref name="StraightD" /> A 2014 investigation applied modern engineering analysis and found that the steel was half as thick as it should have been for a tank of its size even with the lower standards they had at the time. Another issue was that the steel lacked ] and was made more brittle as a result.<ref name="GlobeSchworm" /> The tank's ]s were also apparently flawed, and cracks first formed at the rivet holes.<ref name="Sohn" /> | |||

| In 2016, a team of scientists and students at ] conducted extensive studies of the disaster, gathering data from many sources, including 1919 newspaper articles, old maps, and weather reports.<ref name="AP-Harv">{{Cite news |url=https://www.boston.com/news/history/2016/11/24/slow-as-molasses-sweet-but-deadly-1919-disaster-explained |title=Slow as molasses? Sweet but deadly 1919 disaster explained |date=November 24, 2016 |work=Boston.com |access-date=December 3, 2016 |agency=Associated Press}}</ref> The student researchers also studied the behavior of cold corn syrup flooding a scale model of the affected neighborhood.<ref name="NYT-Harv">{{Cite news |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/26/science/boston-molasses-flood-science.html |title=Solving a Mystery Behind the Deadly 'Tsunami of Molasses' of 1919 |last=Mccann |first=Erin |date=November 26, 2016 |work=The New York Times |access-date=December 3, 2016}}</ref> The researchers concluded that the reports of the high speed of the flood were credible.<ref name="NYT-Harv" /> | |||

| Two days before the disaster, warmer molasses had been added to the tank, reducing the viscosity of the fluid. When the tank collapsed, the fluid cooled quickly as it spread, until it reached Boston's winter evening temperatures and the viscosity increased dramatically.<ref>{{Cite news |url=http://www.alphagalileo.org/ViewItem.aspx?ItemId=170069&CultureCode=en |title=Molasses Creates a Sticky Situation |date=November 17, 2016 |access-date=November 25, 2016 |publisher=] }}{{Dead link|date=August 2024 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes }}</ref> The Harvard study concluded that the molasses cooled and thickened quickly as it rushed through the streets, hampering efforts to free victims before they suffocated.<ref name="AP-Harv" /><ref name="NYT-Harv" /><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Sharp |first1=Nicole |last2=Kennedy |first2=Jordan |last3=Rubinstein |first3=Shmuel |date=November 21, 2016 |title=Abstract: L27.00008 : In a sea of sticky molasses: The physics of the Boston Molasses Flood |url=http://meetings.aps.org/Meeting/DFD16/Session/L27.8 |journal=Bulletin of the American Physical Society |volume=61 |access-date=November 25, 2016 |number=20}}</ref> | |||

| == Area today == | |||

| ] | |||

| United States Industrial Alcohol did not rebuild the tank. The property formerly occupied by the molasses tank and the North End Paving Company became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway (predecessor to the ]). It is now the site of a city-owned recreational complex, officially named ], featuring a ] field, a playground, and ] courts.<ref name="Harris" /> Immediately to the east is the larger Puopolo Park, with additional recreational facilities.<ref name="BHA" /> | |||

| A small plaque at the entrance to Puopolo Park, placed by the Bostonian Society, commemorates the disaster.<ref name=Ocker /> The plaque, titled "Boston Molasses Flood", reads: | |||

| {{quote|On January 15, 1919, a molasses tank at 529 Commercial Street exploded under pressure, killing 21 people. A 40-foot wave of molasses buckled the elevated railroad tracks, crushed buildings and inundated the neighborhood. Structural defects in the tank combined with unseasonably warm temperatures contributed to the disaster.}} | |||

| The accident has since become a staple of local culture, not only for the damage the flood brought, but also for the sweet smell that filled the North End for decades after the disaster.<ref name="Smithsonian" /> According to journalist Edwards Park, "The smell of molasses remained for decades a distinctive, unmistakable atmosphere of Boston."<ref name="Smithsonian" /> | |||

| On January 15, 2019, for the 100th anniversary of the event, a ceremony was held in remembrance. Ground-penetrating radar was used to identify the exact location of the tank from 1919.<ref name="Results of Geophysical survey at Langone Park: 100 Years since the Great Molasses Flood">{{cite web |last1=Steinberg |first1=John M. |title=Results of Geophysical survey at Langone Park: 100 Years since the Great Molasses Flood |url=https://blogs.umb.edu/fiskecenter/2019/01/14/results-of-geophysical-survey-at-langone-park-100-years-since-the-great-molasses-flood/ |website=The Fiske Center Blog |date=January 14, 2019 |publisher=Fiske Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts Boston |access-date=16 October 2023}}</ref> The concrete slab base for the tank remains in place approximately {{convert|20|in|cm}} below the surface of the baseball diamond at ]. Attendees of the ceremony stood in a circle marking the edge of the tank. The 21 names of those who died in, or as a result of, the flood were read aloud.<ref name="Globe_2019">{{Cite news |url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2019/01/15/remembering-great-molasses-flood-years-later/zNqJPoyHTuuSWcXKIZv0HM/story.html |title=Boston officials remember the Great Molasses Flood, 100 years later |last=Sweeney |first=Emily |date=January 15, 2019 |work=The Boston Globe |access-date=January 26, 2019}}</ref><ref name="Universal_Hub_2019">{{Cite web |url=https://www.universalhub.com/2019/gathering-around-where-molasses-tank-used |title=Gathering around the site of the molasses tank to remember its victims |last=adamg |date=January 15, 2019 |location=Boston, Massachusetts |access-date=January 26, 2019}}</ref> | |||

| Many laws and regulations governing construction were changed as a direct result of the disaster, including requirements for oversight by a ] and ].<ref name="nbc 100">{{Cite web |url=https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/great-boston-molasses-flood-1919-killed-21-after-2-million-n958326 |title=The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 killed 21 after 2 million gallon tank erupted |last=Kesslen |first=Ben |date=January 14, 2019 |website=] |access-date=January 14, 2019}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal |last=Durso |first=Fred |date=May 1, 2011 |title=The Great Boston Molasses Flood |url=https://www.nfpa.org/news-and-research/publications/nfpa-journal/2011/may-june-2011/features/the-great-boston-molasses-flood |journal=NFPA Journal |access-date=March 19, 2019 |archive-date=March 18, 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20190318124613/https://www.nfpa.org/News-and-Research/Publications/NFPA-Journal/2011/May-June-2011/Features/The-Great-Boston-Molasses-Flood |url-status=dead }}</ref> | |||

| == In popular culture == | |||

| * ]' song "Great Molasses Disaster" is about the flood, and their official music video includes many pictures of the aftermath.<ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UZnxuPatgH0 |title=Great Molasses Disaster by The Darkest of the Hillside Thickets |website=] |date=January 18, 2017 }}</ref> | |||

| * Canadian metal band ]'s song "All Hands" from the album '']'' is written from the perspective of a victim of the flood. The piano interlude to the song is titled "Harborside" a reference to the harborside tanks in which the molasses was stored. The last lines of the song references the first hand accounts of the aftermath.<ref>{{cite web | url=https://genius.com/Protest-the-hero-all-hands-lyrics | title=Protest the Hero – All Hands }}</ref> | |||

| * Comedian and actress ], on ], passionately spoke about the Great Molasses Flood where she mentions that she was "reduced to tears" talking about the tragedy, where people outside of Boston are far less aware of the event. <ref>{{Cite web |url=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EW77j4AC6Wo |title=Ayo Edebiri's Dad Refused to Let Martin Scorsese Film in Their House for The Departed |website=] |date=June 18, 2024 }}</ref> | |||

| == See also == | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==Notes== | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| == References == | |||

| {{Reflist|30em|refs= | |||

| <ref name="Smithsonian">{{Cite journal |last=Park |first=Edwards |date=November 1983 |title=Without Warning, Molasses in January Surged Over Boston |url=http://edp.org/molpark.htm |journal=Smithsonian |volume=14 |issue=8 |pages=213–230 |access-date=March 24, 2013}} Reprinted at ''Eric Postpischil's Domain'', "Eric Postpischil's Molasses Disaster Pages, Smithsonian Article", June 14, 2009.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="DarkTide">{{Cite book |url=https://archive.org/details/darktide00step |title=Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 |last=Puleo |first=Stephen |publisher=Beacon Press |year=2004 |isbn=0-8070-5021-0 |url-access=registration}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="SciAmJabr">{{Cite journal |last=Jabr |first=Ferris |date=July 17, 2013 |title=The Science of the Great Molasses Flood |url=https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/molasses-flood-physics-science/ |access-date=October 16, 2013 |website=]}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="NYTimes1919">{{Cite news |url=https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1919/01/16/97058317.pdf |title=12 Killed When Tank of Molasses Explodes |date=January 15, 1919 |work=] |access-date=May 30, 2008 |publication-date=January 16, 1919 |issn=0362-4331}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="StraightD">{{Cite web |url=http://www.straightdope.com/columns/041231.html |title=Was Boston once literally flooded with molasses? |last=Adams |first=Cecil |author-link=Cecil Adams |date=December 31, 2004 |website=The Straight Dope |publisher=The Chicago Reader |access-date=December 16, 2006}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="TheHour">{{Cite news |url=https://news.google.com/newspapers?id=s6s0AAAAIBAJ&pg=949%2C3011666 |title=The Great Boston Molasses Disaster of 1919 |date=January 17, 1979 |work=The Hour |agency=United Press International}}</ref> | |||

| <ref name="YankeeMason">{{Cite journal |last=Mason |first=John |date=January 1965 |title=The Molasses Disaster of January 15, 1919 |url=http://edp.org/molyank.htm |journal=] |access-date=March 21, 2005 |archive-date=July 10, 2012 |archive-url=https://archive.today/20120710192737/http://edp.org/molyank.htm |url-status=dead }} Reprinted at ''Eric Postpischil's Domain'', "Eric Postpischil's Molasses Disaster Pages, Yankee Magazine Article", June 14, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2014.</ref> | |||

| <ref name="PuleoQuote79">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yWtJGLG0aEcC&pg=PA263 |title=Dark Tide: The Great Molasses Flood of 1919 |last=Puleo |first=Stephen |publisher=Beacon Press |year=2010 |isbn=9780807096673 |page=79 |quote=Any disruption at the tank could prove disastrous to his plan to outrun Prohibition by producing alcohol as rapidly as possible at the East Cambridge distillery.}}</ref> | |||

| ==Sequence of events== | |||

| ] | |||

| The disaster occurred at the ] facility on ], ], one day before the ] enabling ] was ratified. At the time, molasses was the standard sweetener across the United States (now supplanted by ]). Molasses was also fermented (producing ]) for use in making ] and as a key component in the manufacture of ]. The stored molasses was awaiting transfer to the Purity plant situated between Willow Street and what is now named Evereteze Way in ]. | |||

| <ref name="YankeeStanley">{{Cite journal |last=Stanley |first=Robert |year=1989 |title=Footnote to History |journal=Yankee |volume=53 |page=101 |quote=In January of 1919 Purity Distilling Company of Boston, maker of high-grade rum, was working three shifts a day in a vain attempt to outrun national Prohibition.}}</ref> | |||

| At 529 Commercial Street, a huge molasses tank (50 ] (15 ]) tall, 240 ft (70 m) around and containing as much as 2.5 million US ]s (9,500 m³ or 9,500,000 ]s)) collapsed. The collapse unleashed an immense wave of molasses between 8 and 15 ft (2.5 to 4.5 m) high, moving at 35 ] (56 ]) and exerting a pressure of 2 ]/ft² (200 kPa). The molasses wave was of sufficient force to break the girders of the adjacent ]'s ] structure and lift a ] off the tracks. Several nearby buildings were also destroyed, and several blocks were flooded to a depth of 2 to 3 feet. Twenty-one people were killed and 150 injured as the molasses crushed and ] many of the victims. Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims. | |||

| <ref name="Silverman">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=yWVddZqyqggC&pg=PA37 |title=Einstein's Refrigerator: And Other Stories from the Flip Side of History |last=Silverman |first=Steve |publisher=Andrews McMeel |year=2001 |isbn=978-0-7407-1419-1 |page=37 |quote=First, it was believed that the tank was overfilled because of the impending threat of Prohibition.}}</ref> | |||

| [[Image:Boston molasses detail map.png|right|thumb|300px|Detail of molasses flood area. | |||

| '''1.''' Purity Distilling molasses tank | |||

| '''2.''' Firehouse 31 (heavy damage) | |||

| '''3.''' Paving department and police station | |||

| '''4.''' Purity offices (flattened) | |||

| '''5.''' Copps Hill Terrace | |||

| '''6.''' Boston Gas Light building (damaged) | |||

| '''7.''' Purity warehouse (mostly intact) | |||

| '''8.''' Residential area (site of flattened Clougherty house) | |||

| ]] | |||

| It took over six months to remove the molasses from the ] streets, theaters, businesses, ]s, and homes. The harbor ran brown until summer. Local residents brought a ] (one of the first held in ]) against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company, which had bought Purity Distilling in 1917. In spite of the company's attempts to claim that the tank had been blown up by ]s (because some of the alcohol produced was to be used in making munitions) it ultimately paid out $600,000 in out-of-court settlements (at least $6.6 million in 2005 dollars). | |||

| <ref name="Streissguth">{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=FtbnIe103p4C&pg=PA13 |title=The Roaring Twenties |last=Streissguth |first=Thomas |publisher=Infobase |year=2009 |isbn=978-1-4381-0887-2 |page=13}}</ref> | |||

| United States Industrial Alcohol did not rebuild the tank. The property became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway (predecessor to the ]) and is currently the site of a city-owned ] field. | |||

| <ref name="GlobeSchworm">{{Cite news |url=https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2015/01/14/nearly-century-later-new-insight-into-cause-great-molasses-flood/CNqLYc0T58kNo3MxP872iM/story.html |title=Nearly a century later, new insight into cause of Great Molasses Flood of 1919 |last=Schworm |first=Peter |date=January 15, 2015 |work=] |access-date=January 16, 2015}}</ref> | |||

| According to local ], molasses left from this disaster can still be smelled on hot days. Given over 80 years of rainfall, natural ], and extensive redevelopment of the area, it is reasonable to assume that any residue has long since dissipated. | |||

| <ref name="Harris">{{Cite book |title=Boston: a Guide to Unique Places |last1=Harris |first1=Patricia |last2=Lyon |first2=David |publisher=The Globe Pequot Press |year=2004 |isbn=0-7627-3011-0 |pages=63–64}}</ref> | |||

| ==Causes== | |||

| ]'' article about the disaster]] | |||

| <ref name="BHA">{{Cite web |url=http://www.bostonharborwalk.com/placestogo/location.php?nid=3&sid=21 |title=Places to go: Downtown/North End |publisher=The Boston Harbor Association |url-status=dead |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130913150554/http://www.bostonharborwalk.com/placestogo/location.php?nid=3&sid=21 |archive-date=September 13, 2013 |access-date=September 5, 2013}}</ref> | |||

| The cause of the accident is not known with certainty. One possible explanation is that the tank may have been shoddily constructed, insufficiently tested, and overfilled. Another is that it may have burst due to ] occurring within (the ] this would have produced would have raised the pressure inside the tank); this would probably have been helped by the unusual increase in the local temperatures that occurred over the previous day: the air temperature rose from 2 °] to 41 °F (-17 °] to 4 °C) over that period. A third possibility is that the rising temperatures alone were enough to cause the collapse. | |||

| <ref name="HistoryChannel">{{Cite web |url=http://www.history.com/news/the-great-molasses-flood-of-1919 |title=The Great Molasses Flood of 1919 |last=Andrews |first=Evan |date=January 13, 2017 |website=The History Channel |publisher=A&E Television Networks |access-date=December 21, 2017}}</ref> | |||

| An inquiry after the disaster revealed that Arthur Jell, who oversaw the construction, neglected basic safety tests, such as filling the tank with water to check for leaks. When filled with molasses, the tank leaked so badly that it was painted brown to hide the leaks. Local residents collected leaked molasses for their homes. | |||

| <ref name="Ocker">{{Cite book |title=The New England Grimpendium |last=Ocker |first=J. W. |publisher=The Countryman Press |year=2010 |isbn=978-0-88150-919-9 |location=Woodstock, VT |page=97}}</ref> | |||

| Some accounts relate that given the timing of the accident, the tank may have been overfilled so that the owners could produce as much ethanol (for liquor) as possible before ] came into effect. In fact, the ] would not become law for another year, and the ] would not ban the operations of industrial alcohol producers. | |||

| ==References== | |||

| * by ] | |||

| * | |||

| * {{cite news | |||

| |title=Great molasses flood remembered | |||

| |date=], ] | |||

| |publisher=] | |||

| |url=http://www.cnn.com/2004/US/Northeast/01/23/molasses.flood.ap/ | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| ==Further reading== | ==Further reading== | ||

| * |

* {{Cite book |last=Puleo |first=Stephen |year=2004 |title=Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 |url=https://archive.org/details/darktide00step |url-access=registration |location=Boston |publisher=] |isbn=0-8070-5021-0}} | ||

| ==External links== | == External links == | ||

| {{Commons category|Boston Molasses Disaster}} | |||

| * | |||

| * . Photos related to the event on Flickr. Many phrases are direct quotes. | |||

| * from the Massachusetts Historical Society | |||

| * , four-minute audio story at The American Storyteller Radio Journal | |||

| * Reprinted from Yankee Magazine | |||

| * | * with Stephen Puleo, author of the book listed in "Further reading" | ||

| * {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20110103023107/http://www3.gendisasters.com/massachusetts/2678/boston%2C-ma-%2526%2523039%3Bmolasses-flood%2526%2523039%3B-tank-explosion%2C-jan-1919 |date=2011-01-03}} | |||

| * (via archive.org) | |||

| * , from the ''Washington Times'', January 18, 1919 | |||

| * (photos) | |||

| * (story with more photos) | |||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 22:48, 5 January 2025

1919 accident in Massachusetts, United States

The wreckage of the collapsed tank is visible in background, center, next to the light-colored warehouse The wreckage of the collapsed tank is visible in background, center, next to the light-colored warehouse | |

| Date | January 15, 1919; 105 years ago (1919-01-15) |

|---|---|

| Time | Approximately 12:30 pm |

| Location | Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 42°22′06.6″N 71°03′21.2″W / 42.368500°N 71.055889°W / 42.368500; -71.055889 |

| Cause | Cylinder stress failure |

| Deaths | 21 |

| Non-fatal injuries | 150 injured |

The Great Molasses Flood, also known as the Boston Molasses Disaster, was a disaster that occurred on Wednesday, January 15, 1919, in the North End neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts.

A large storage tank filled with 2.3 million U.S. gallons (8,700 cubic meters) of molasses, weighing approximately 13,000 short tons (12,000 metric tons) burst, and the resultant wave of molasses rushed through the streets at an estimated 35 miles per hour (56 kilometers per hour), killing 21 people and injuring 150. The event entered local folklore and residents reported for decades afterwards that the area still smelled of molasses on hot summer days.

Flood

Molasses can be fermented to produce ethanol, the active ingredient in alcoholic beverages and a key component in munitions. The disaster occurred at the Purity Distilling Company facility at 529 Commercial Street near Keany Square. A considerable amount of molasses had been stored there by the company, which used the harborside Commercial Street tank to offload molasses from ships and store it for later transfer by pipeline to the Purity ethanol plant situated between Willow Street and Evereteze Way in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The molasses tank stood 50 feet (15 meters) tall and 90 ft (27 m) in diameter, and contained as much as 2.3 million US gal (8,700 m).

On January 15, 1919, temperatures in Boston had risen above 40 degrees Fahrenheit (4 degrees Celsius), climbing rapidly from the frigid temperatures of the preceding days, and the previous day, a ship had delivered a fresh load of molasses, which had been warmed to decrease its viscosity for transfer. Possibly due to the thermal expansion of the older, colder molasses already inside the tank, the tank burst open and collapsed at approximately 12:30 p.m. Witnesses reported that they felt the ground shake and heard a roar as it collapsed, a long rumble similar to the passing of an elevated train; others reported a tremendous crashing, a deep growling, "a thunderclap-like bang!", and a sound like a machine gun as the rivets shot out of the tank.

The density of molasses is about 1.4 metric tons per cubic meter (12 pounds per US gallon), 40 percent more dense than water, resulting in the molasses having a great deal of potential energy. The collapse translated this energy into a wave of molasses 25 ft (8 m) high at its peak, moving at 35 mph (56 km/h). The wave was of sufficient force to drive steel panels of the burst tank against the girders of the adjacent Boston Elevated Railway's Atlantic Avenue structure and tip a streetcar momentarily off the El's tracks. Stephen Puleo describes how nearby buildings were swept off their foundations and crushed. Several blocks were flooded to a depth of 2 to 3 ft (60 to 90 cm). Puleo quotes a Boston Post report:

Molasses, waist deep, covered the street and swirled and bubbled about the wreckage Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass, showed where any life was Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared. Human beings—men and women—suffered likewise.

The Boston Globe reported that people "were picked up by a rush of air and hurled many feet". Others had debris hurled at them from the rush of sweet-smelling air. A truck was picked up and hurled into Boston Harbor. After the initial wave, the molasses became viscous, exacerbated by the cold temperatures, trapping those caught in the wave and making it even more difficult to rescue them. About 150 people were injured, and 21 people and several horses were killed. Some were crushed and drowned by the molasses or by the debris that it carried within. The wounded included people, horses, and dogs; coughing fits became one of the most common ailments after the initial blast. Edwards Park wrote of one child's experience in a 1983 article for Smithsonian:

Anthony di Stasio, walking homeward with his sisters from the Michelangelo School, was picked up by the wave and carried, tumbling on its crest, almost as though he were surfing. Then he grounded and the molasses rolled him like a pebble as the wave diminished. He heard his mother call his name and couldn't answer, his throat was so clogged with the smothering goo. He passed out, then opened his eyes to find three of his four sisters staring at him.

Aftermath

First to the scene were 116 cadets under the direction of Lieutenant Commander H. J. Copeland from USS Nantucket, a training ship of the Massachusetts Nautical School (now the Massachusetts Maritime Academy) that was docked nearby at the playground pier. The cadets ran several blocks toward the accident and entered into the knee-deep flood of molasses to pull out the survivors, while others worked to keep curious onlookers from getting in the way of the rescuers. The Boston Police, Red Cross, Army, and Navy personnel soon arrived. Some nurses from the Red Cross dove into the molasses, while others tended to the injured, keeping them warm and feeding the exhausted workers. Many of these people worked through the night, and the injured were so numerous that doctors and surgeons set up a makeshift hospital in a nearby building. Rescuers found it difficult to make their way through the syrup to help the victims, and four days elapsed before they stopped searching; many of the dead were so glazed over in molasses that they were hard to recognize. Other victims were swept into Boston Harbor and were found three to four months after the disaster.

In the wake of the accident, 119 residents brought a class-action lawsuit against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company (USIA), which had bought Purity Distilling in 1917. It was one of the first class-action suits in Massachusetts and is considered a milestone in paving the way for modern corporate regulation. The company claimed that the tank had been blown up by anarchists because some of the alcohol produced was to be used in making munitions, but a court-appointed auditor found USIA responsible after three years of hearings, and the company ultimately paid out $628,000 in damages ($11 million in 2023, adjusted for inflation). Relatives of those killed reportedly received around $7,000 per victim (equivalent to $123,000 in 2023).

Cleanup

Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash away the molasses and sand to absorb it, and the harbor was brown with molasses until summer. The cleanup in the immediate area took weeks, with several hundred people contributing to the effort, and it took longer to clean the rest of Greater Boston and its suburbs. Rescue workers, cleanup crews, and sight-seers had tracked molasses through the streets and spread it to subway platforms, to the seats inside trains and streetcars, to pay telephone handsets, into homes, and to countless other places. It was reported that "Everything that a Bostonian touched was sticky."

Fatalities

- Purity Distilling molasses tank

- Firehouse 31 (heavy damage)

- Paving department and police station

- Purity offices (flattened)

- Copps Hill Terrace

- Boston Gas Light building (damaged)

- Purity warehouse (mostly intact)

- Residential area (site of flattened Clougherty house)

| Name | Age | Occupation |

|---|---|---|

| Patrick Breen | 44 | Laborer (North End Paving Yard) |

| William Brogan | 61 | Teamster |

| Bridget Clougherty | 65 | Homemaker |

| Stephen Clougherty | 34 | Unemployed |

| John Callahan | 43 | Paver (North End Paving Yard) |

| Maria Di Stasio | 10 | Child |

| William Duffy | 58 | Laborer (North End Paving Yard) |

| Peter Francis | 64 | Blacksmith (North End Paving Yard) |

| Flaminio Gallerani | 37 | Driver |

| Pasquale Iantosca | 10 | Child |

| James J. Kenneally | 48 | Laborer (North End Paving Yard) |

| Eric Laird | 17 | Teamster |

| George Layhe | 38 | Firefighter (Engine 31) |

| James Lennon | 64 | Teamster/Motorman |

| Ralph Martin | 21 | Driver |

| James McMullen | 46 | Foreman, Bay State Express |

| Cesar Nicolo | 32 | Expressman |

| Thomas Noonan | 43 | Longshoreman |

| Peter Shaughnessy | 18 | Teamster |

| John M. Seiberlich | 69 | Blacksmith (North End Paving Yard) |

| Michael Sinnott | 78 | Messenger |

Causes

Several factors might have contributed to the disaster. The first factor is that the tank may have leaked from the very first day that it was filled in 1915. The tank was also constructed poorly and tested insufficiently, and carbon dioxide production might have raised the internal pressure due to fermentation in the tank. Warmer weather the previous day would have assisted in building this pressure, as the air temperature rose from 2 to 41 °F (−17 to 5.0 °C) over that period. The failure occurred from a manhole cover near the base of the tank, and a fatigue crack there possibly grew to the point of criticality.

The tank had been filled to capacity only eight times since it was built a few years previously, putting the walls under an intermittent, cyclical load. Several authors say that the Purity Distilling Company was trying to out-race prohibition, as the 18th amendment was ratified the next day (January 16, 1919) and took effect one year later. An inquiry after the disaster revealed that Arthur Jell, USIA's treasurer, neglected basic safety tests while overseeing construction of the tank, such as filling it with water insufficient to check for leaks, and ignored warning signs such as groaning noises each time the tank was filled. He had no architectural or engineering experience. When filled with molasses, the tank leaked so badly that it was painted brown to hide the leakage. Local residents collected leaked molasses for their homes. A 2014 investigation applied modern engineering analysis and found that the steel was half as thick as it should have been for a tank of its size even with the lower standards they had at the time. Another issue was that the steel lacked manganese and was made more brittle as a result. The tank's rivets were also apparently flawed, and cracks first formed at the rivet holes.

In 2016, a team of scientists and students at Harvard University conducted extensive studies of the disaster, gathering data from many sources, including 1919 newspaper articles, old maps, and weather reports. The student researchers also studied the behavior of cold corn syrup flooding a scale model of the affected neighborhood. The researchers concluded that the reports of the high speed of the flood were credible.

Two days before the disaster, warmer molasses had been added to the tank, reducing the viscosity of the fluid. When the tank collapsed, the fluid cooled quickly as it spread, until it reached Boston's winter evening temperatures and the viscosity increased dramatically. The Harvard study concluded that the molasses cooled and thickened quickly as it rushed through the streets, hampering efforts to free victims before they suffocated.

Area today

United States Industrial Alcohol did not rebuild the tank. The property formerly occupied by the molasses tank and the North End Paving Company became a yard for the Boston Elevated Railway (predecessor to the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority). It is now the site of a city-owned recreational complex, officially named Langone Park, featuring a Little League Baseball field, a playground, and bocce courts. Immediately to the east is the larger Puopolo Park, with additional recreational facilities.

A small plaque at the entrance to Puopolo Park, placed by the Bostonian Society, commemorates the disaster. The plaque, titled "Boston Molasses Flood", reads:

On January 15, 1919, a molasses tank at 529 Commercial Street exploded under pressure, killing 21 people. A 40-foot wave of molasses buckled the elevated railroad tracks, crushed buildings and inundated the neighborhood. Structural defects in the tank combined with unseasonably warm temperatures contributed to the disaster.

The accident has since become a staple of local culture, not only for the damage the flood brought, but also for the sweet smell that filled the North End for decades after the disaster. According to journalist Edwards Park, "The smell of molasses remained for decades a distinctive, unmistakable atmosphere of Boston."

On January 15, 2019, for the 100th anniversary of the event, a ceremony was held in remembrance. Ground-penetrating radar was used to identify the exact location of the tank from 1919. The concrete slab base for the tank remains in place approximately 20 inches (51 cm) below the surface of the baseball diamond at Langone Park. Attendees of the ceremony stood in a circle marking the edge of the tank. The 21 names of those who died in, or as a result of, the flood were read aloud.

Many laws and regulations governing construction were changed as a direct result of the disaster, including requirements for oversight by a licensed architect and civil engineer.

In popular culture

- The Darkest of the Hillside Thickets' song "Great Molasses Disaster" is about the flood, and their official music video includes many pictures of the aftermath.

- Canadian metal band Protest The Hero's song "All Hands" from the album Palimpsest is written from the perspective of a victim of the flood. The piano interlude to the song is titled "Harborside" a reference to the harborside tanks in which the molasses was stored. The last lines of the song references the first hand accounts of the aftermath.

- Comedian and actress Ayo Edebiri, on Late Night with Seth Meyers, passionately spoke about the Great Molasses Flood where she mentions that she was "reduced to tears" talking about the tragedy, where people outside of Boston are far less aware of the event.

See also

Notes

- The flood has more recently been known as the "Boston Molassacre".

- At 1.4 kg/L (12 lb/US gal), 8,700 m (310,000 cu ft) of molasses weighs 12,180 tonnes (11,990 long tons; 13,430 short tons).

References

- Hinrichsen, Erik (September 8, 2010). "The Boston Molasses Disaster: Causes of the Molasses Tank Explosion". Bright Hub. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- "'Molasses Disaster' Featured at Evening at 74". Beacon Hill Times. Retrieved March 5, 2019.

- Kelly, Kate (January 8, 2012). "The 'Boston Molassacre'". America Comes Alive. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- "Great Molasses Flood: US marks 100 years since deadly wave of treacle trashed part of Boston". South China Morning Post. Associated Press. January 14, 2019. Retrieved March 18, 2019.

- ^ Sohn, Emily (January 15, 2019). "Why the Great Molasses Flood Was So Deadly". The History Channel. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Park, Edwards (November 1983). "Without Warning, Molasses in January Surged Over Boston". Smithsonian. 14 (8): 213–230. Retrieved March 24, 2013. Reprinted at Eric Postpischil's Domain, "Eric Postpischil's Molasses Disaster Pages, Smithsonian Article", June 14, 2009.

- ^ Puleo, Stephen (2004). Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919. Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5021-0.

- "100 Years Later: Lessons From Boston's Molasses Flood Of 1919". www.wbur.org. January 15, 2019.

- ^ Kesslen, Ben (January 14, 2019). "The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 killed 21 after 2 million gallon tank erupted". NBC News. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Jabr, Ferris (July 17, 2013). "The Science of the Great Molasses Flood". Scientific American. Retrieved October 16, 2013.

- Park, Edwards (December 19, 2018). "Without Warning, Molasses in January Surged Over Boston". edp.org. Retrieved March 24, 2019.

magine an estimated 14,000 tons of the thick, sticky fluid running wild. It left the ruptured tank in a choking brown wave, 15 feet high, wiping out everything that stood in its way. One steel section of the tank was hurled across Commercial Street, neatly knocking out one of the uprights supporting the El.

- ^ Buell, Spencer (January 12, 2019). "Anarchists, Horses, Heroes: 12 Things You Didn't Know about the Great Boston Molasses Flood". Boston Magazine. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- ^ "12 Killed When Tank of Molasses Explodes" (PDF). The New York Times (published January 16, 1919). January 15, 1919. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 30, 2008.

- Andrews, Evan (May 16, 2023). "The Great Molasses Flood of 1919". HISTORY. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ^ Betancourt, Sarah (January 13, 2019). "The Great Boston Molasses Flood: why the strange disaster matters today". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- "The Great Boston Molasses Disaster of 1919". The Hour. United Press International. January 17, 1979.

- Andrews, Evan (January 13, 2017). "The Great Molasses Flood of 1919". The History Channel. A&E Television Networks. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- Mason, John (January 1965). "The Molasses Disaster of January 15, 1919". Yankee. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2005. Reprinted at Eric Postpischil's Domain, "Eric Postpischil's Molasses Disaster Pages, Yankee Magazine Article", June 14, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2014.

- Dwyer, Dialynn (January 13, 2019). "'There was no escape from the wave': These are the 21 victims of the Great Boston Molasses Flood". Boston.com. Retrieved January 14, 2019.

- Barry, Quan (September 26, 2004). Controvertibles. University of Pittsburgh Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt5vkg3w. ISBN 978-0-8229-8015-5.

- Birnbaum, Amy. (2019). The Great Molasses Flood: A bizarre disaster struck one of America's biggest cities 100 years ago. Scholastic News (Explorer Ed.), 81(11), 4.

- Puleo, Stephen (2010). Dark Tide: The Great Molasses Flood of 1919. Beacon Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780807096673.

Any disruption at the tank could prove disastrous to his plan to outrun Prohibition by producing alcohol as rapidly as possible at the East Cambridge distillery.

- Stanley, Robert (1989). "Footnote to History". Yankee. 53: 101.

In January of 1919 Purity Distilling Company of Boston, maker of high-grade rum, was working three shifts a day in a vain attempt to outrun national Prohibition.

- Silverman, Steve (2001). Einstein's Refrigerator: And Other Stories from the Flip Side of History. Andrews McMeel. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-7407-1419-1.

First, it was believed that the tank was overfilled because of the impending threat of Prohibition.

- Streissguth, Thomas (2009). The Roaring Twenties. Infobase. p. 13. ISBN 978-1-4381-0887-2.

- Adams, Cecil (December 31, 2004). "Was Boston once literally flooded with molasses?". The Straight Dope. The Chicago Reader. Retrieved December 16, 2006.

- Schworm, Peter (January 15, 2015). "Nearly a century later, new insight into cause of Great Molasses Flood of 1919". The Boston Globe. Retrieved January 16, 2015.

- ^ "Slow as molasses? Sweet but deadly 1919 disaster explained". Boston.com. Associated Press. November 24, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ Mccann, Erin (November 26, 2016). "Solving a Mystery Behind the Deadly 'Tsunami of Molasses' of 1919". The New York Times. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- "Molasses Creates a Sticky Situation". AlphaGalileo. November 17, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Sharp, Nicole; Kennedy, Jordan; Rubinstein, Shmuel (November 21, 2016). "Abstract: L27.00008 : In a sea of sticky molasses: The physics of the Boston Molasses Flood". Bulletin of the American Physical Society. 61 (20). Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- Harris, Patricia; Lyon, David (2004). Boston: a Guide to Unique Places. The Globe Pequot Press. pp. 63–64. ISBN 0-7627-3011-0.

- "Places to go: Downtown/North End". The Boston Harbor Association. Archived from the original on September 13, 2013. Retrieved September 5, 2013.

- Ocker, J. W. (2010). The New England Grimpendium. Woodstock, VT: The Countryman Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0-88150-919-9.

- Steinberg, John M. (January 14, 2019). "Results of Geophysical survey at Langone Park: 100 Years since the Great Molasses Flood". The Fiske Center Blog. Fiske Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Massachusetts Boston. Retrieved October 16, 2023.

- Sweeney, Emily (January 15, 2019). "Boston officials remember the Great Molasses Flood, 100 years later". The Boston Globe. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- adamg (January 15, 2019). "Gathering around the site of the molasses tank to remember its victims". Boston, Massachusetts. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

- Durso, Fred (May 1, 2011). "The Great Boston Molasses Flood". NFPA Journal. Archived from the original on March 18, 2019. Retrieved March 19, 2019.

- "Great Molasses Disaster by The Darkest of the Hillside Thickets". YouTube. January 18, 2017.

- "Protest the Hero – All Hands".

- "Ayo Edebiri's Dad Refused to Let Martin Scorsese Film in Their House for The Departed". YouTube. June 18, 2024.

Further reading

- Puleo, Stephen (2004). Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919. Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5021-0.

External links

- Boston Public Library. Photos related to the event on Flickr. Many phrases are direct quotes.

- The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, four-minute audio story at The American Storyteller Radio Journal

- Interview with Stephen Puleo, author of the book listed in "Further reading"

- Molasses Flood of 1919Archived 2011-01-03 at the Wayback Machine

- "Scenes in the Molasses-Flooded Streets of Boston", from the Washington Times, January 18, 1919

- 100 years ago, Boston’s North End was hit by a deadly wave of molasses (photos)

- The Great Molasses Flood of 1919 was Boston’s strangest disaster (story with more photos)

- 1910s in Boston

- 1919 disasters in the United States

- 1919 in Massachusetts

- 1919 industrial disasters

- Cultural history of Boston

- Disasters in Boston

- Engineering failures

- Environmental disasters in the United States

- Floods in the United States

- Food processing disasters

- Industrial accidents and incidents in the United States

- January 1919 events in the United States

- Molasses

- North End, Boston