| Revision as of 12:11, 26 July 2013 view sourceDrChrissy (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users21,946 edits →Intelligence and cognition: can not be verified← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 22:22, 30 December 2024 view source ScottishFinnishRadish (talk | contribs)Checkusers, Oversighters, Administrators61,099 editsm rv sockTag: Rollback | ||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Largest living land animal}} | |||

| {{about|the living species|extinct relatives also known as elephants|Elephantidae|other uses|Elephant (disambiguation)}} | |||

| {{About|a paraphyletic group|close extinct relatives|Elephantidae|other uses}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Featured article}} | |||

| {{pp-vandalism|expiry=2014-03-01T01:12:05Z|small=yes}}{{pp-move-indef}} | |||

| {{Pp-vandalism|small=yes}} | |||

| {{use British English|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Pp-move}} | |||

| {{Taxobox | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=January 2020}} | |||

| {{Use British English|date=January 2013}} | |||

| {{Paraphyletic group | |||

| | name = Elephants | | name = Elephants | ||

| | image =African Bush Elephant.jpg | | image = African Bush Elephant.jpg | ||

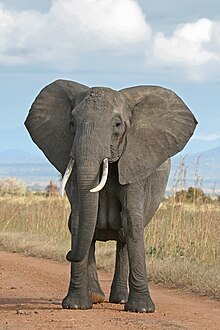

| | image_caption = African elephant in ], Tanzania | | image_caption = A female ] in ], Tanzania | ||

| | auto = yes | |||

| | fossil_range = {{Fossil range|Pliocene|Recent}} | |||

| | fossil_range = {{Fossil range|Late Miocene | Present}} | |||

| | regnum = ]ia | |||

| | parent = Elephantidae | |||

| | phylum = ] | |||

| | includes = * '']'' <small>Anonymous, 1827</small> | |||

| | subphylum = ] | |||

| * '']'' <small>], ]</small> | |||

| | classis = ] | |||

| * {{extinct}}'']'' <small>Matsumoto, 1925</small> | |||

| | superordo = ] | |||

| | excludes = * {{extinct}}'']'' <small>Brookes, 1828</small> | |||

| | ordo = ] | |||

| | range_map = Loxodonta Elephas distribution.png | |||

| | familia = ] | |||

| | range_map_caption = Distribution of living elephant species | |||

| | familia_authority = ], 1821 | |||

| | subdivision_ranks = Genera | |||

| | subdivision ={{plainlist| | |||

| * '']'' | |||

| * '']''}} | |||

| }} | }} | ||

| '''Elephants''' are |

'''Elephants''' are the ] living land animals. Three living ] are currently recognised: the ] (''] africana''), the ] (''L. cyclotis''), and the ] (''] maximus''). They are the only surviving members of the ] ] and the ] ]; extinct relatives include ]s and ]s. Distinctive features of elephants include a long ] called a trunk, ]s, large ear flaps, pillar-like legs, and tough but sensitive grey skin. The trunk is ], bringing food and water to the mouth and grasping objects. Tusks, which are derived from the incisor teeth, serve both as weapons and as tools for moving objects and digging. The large ear flaps assist in maintaining a constant body temperature as well as in communication. ]s have larger ears and concave backs, whereas Asian elephants have smaller ears and convex or level backs. | ||

| Elephants are |

Elephants are scattered throughout ], South Asia, and Southeast Asia and are found in different habitats, including ]hs, forests, deserts, and ]es. They are ], and they stay near water when it is accessible. They are considered to be ], due to their impact on their environments. Elephants have a ], in which multiple family groups come together to socialise. Females (cows) tend to live in family groups, which can consist of one female with her calves or several related females with offspring. The leader of a female group, usually the oldest cow, is known as the ]. | ||

| Males (bulls) leave their family groups when they reach puberty and may live alone or with other males. Adult bulls mostly interact with family groups when looking for a mate. They enter a state of increased ] and aggression known as ], which helps them gain ] over other males as well as reproductive success. Calves are the centre of attention in their family groups and rely on their mothers for as long as three years. Elephants can live up to 70 years in the wild. They ] by touch, sight, smell, and sound; elephants use ] and ] over long distances. ] has been compared with that of ]s and ]ns. They appear to have ], and possibly show concern for dying and dead individuals of their kind. | |||

| African elephants are listed as ] by the ] (IUCN), while the Asian elephant is classed as ]. One of the biggest threats to elephant populations is the ], as the animals are ] for their ivory tusks. Other threats to wild elephants include ] and conflicts with local people. Elephants are used as ]s in Asia. In the past they were used in war; today, they are often put on display in zoos and circuses. Elephants are highly recognisable and have been featured in art, folklore, religion, literature and ]. | |||

| African bush elephants and Asian elephants are listed as ] and African forest elephants as ] by the ] (IUCN). One of the biggest threats to elephant populations is the ], as the animals are ] for their ivory tusks. Other threats to wild elephants include ] and conflicts with local people. Elephants are used as ]s in Asia. In the past, they were used in war; today, they are often controversially put on display in zoos, or employed for entertainment in ]es. Elephants have an iconic status ] and have been widely featured in art, folklore, religion, literature, and popular culture. | |||

| ==Etymology== | ==Etymology== | ||

| The word |

The word ''elephant'' is derived from the ] word {{lang|la|elephas}} (] {{lang|la|elephantis}}) {{gloss|elephant}}, which is the ] form of the ] {{lang|grc|ἐλέφας}} ({{transliteration|grc|elephas}}) (genitive {{lang|grc|ἐλέφαντος}} ({{transliteration|grc|elephantos}}<ref name="LSJ">{{LSJ|e)le/fas|ἐλέφας|ref}}</ref>)), probably from a non-], likely ].<ref name=etymology>{{cite encyclopedia|author=Harper, D.|title=Elephant|dictionary=Online Etymology Dictionary|url=http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=elephant|access-date=25 October 2012|archive-date=24 December 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20131224141504/http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=elephant|url-status=live}}</ref> It is attested in ] as {{transliteration|gmy|e-re-pa}} (genitive {{transliteration|gmy|e-re-pa-to}}) in ] syllabic script.<ref>{{Cite journal |url=https://www.academia.edu/2229199 |title=Ivory and horn production in Mycenaean texts |journal=Kosmos. Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age |last1=Lujan |first1=E. R. |last2=Bernabe |first2=A |access-date=22 January 2013 |archive-date=20 October 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20211020172849/https://www.academia.edu/2229199 |url-status=live }}</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.palaeolexicon.com/default.aspx?static=12&wid=189|title=elephant|publisher=Palaeolexicon, Word study tool of ancient languages|access-date=19 January 2013|archive-date=4 December 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121204075314/http://www.palaeolexicon.com/default.aspx?static=12&wid=189|url-status=live}}</ref> As in Mycenaean Greek, ] used the Greek word to mean ], but after the time of ], it also referred to the animal.<ref name="LSJ" /> The word ''elephant'' appears in ] as {{lang|enm|olyfaunt}} ({{Circa|1300}}) and was borrowed from ] {{lang|fro|oliphant}} (12th century).<ref name=etymology /> | ||

| ==Taxonomy== | ==Taxonomy and evolution== | ||

| {{cladogram|style=font-size:70%|align=right|caption=A cladogram of the elephants within ] based on molecular evidence<ref name=tabuce>{{cite journal|url=http://phylodiversity.net/azanne/csfar/images/d/d9/Afrotherian_mammals.pdf|first1=R.|last1=Tabuce|first2=R. J.|last2=Asher|first3=T.|last3=Lehmann|s2cid=46133294|year=2008|title=Afrotherian mammals: a review of current data|journal=Mammalia|volume=72|pages=2–14|doi=10.1515/MAMM.2008.004|access-date=19 June 2017|archive-date=24 February 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210224122358/http://phylodiversity.net/azanne/csfar/images/d/d9/Afrotherian_mammals.pdf|url-status=usurped | issn=0025-1461}}</ref> | |||

| === Classification, species and subspecies === | |||

| |{{clade | |||

| {{see also|List of elephant species}} | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| ], India]] | |||

| |1={{Clade | |||

| ] | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| Elephants belong to the ], the sole family within the order ]. Their closest ] relatives are the ]ns (]s and ]s) and the ]es, with which they share the ] ] within the superorder ].<ref name = "Ozawa">{{cite journal|author=Kellogg, M.; Burkett, S.; Dennis, T. R.; Stone, G.; Gray, B. A.; McGuire, P. M.; Zori, R. T.; Stanyon, R.|year=2007|title=Chromosome painting in the manatee supports Afrotheria and Paenungulata|journal=Evolutionary Biology|volume=7|page=6|doi=10.1186/1471-2148-7-6}}</ref> Elephants and sirenians are further grouped in the clade ].<ref name=Ozawa2/> Traditionally, two species of elephants are recognised; the ] (''Loxodonta africana'') of ], and the ] (''] maximus'') of ] and ]. African elephants have larger ears, a concave back, more wrinkled skin, a sloping abdomen and two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk. Asian elephants have smaller ears, a convex or level back, smoother skin, a horizontal abdomen that occasionally sags in the middle and one extension at the tip of the trunk. The looped ridges on the ] are narrower in the Asian elephant while those of the African are more diamond-shaped. The Asian elephant also has ] bumps on its head and some patches of ] on its skin.<ref name=Shoshani38>Shoshani, pp. 38–41.</ref> | |||

| |1={{Clade | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{Clade | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{Clade | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} }} }} | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{Clade | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{Clade | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{Clade | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |2=] ] | |||

| }} }} }} }} }}}} | |||

| Elephants belong to the family ], the sole remaining family within the order ]. Their closest ] relatives are the ]ns (]s and ]s) and the ]es, with which they share the ] ] within the superorder ].<ref name="Ozawa">{{cite journal|author1=Kellogg, M. |author2=Burkett, S. |author3=Dennis, T. R. |author4=Stone, G. |author5=Gray, B. A. |author6=McGuire, P. M. |author7=Zori, R. T. |author8=Stanyon, R. |year=2007|title=Chromosome painting in the manatee supports Afrotheria and Paenungulata|journal=Evolutionary Biology|volume=7|issue=1 |page=6|doi=10.1186/1471-2148-7-6 |pmid=17244368 |pmc=1784077 |doi-access=free |bibcode=2007BMCEE...7....6K }}</ref> Elephants and sirenians are further grouped in the clade ].<ref name=Ozawa2>{{cite journal|author1=Ozawa, T. |author2=Hayashi, S. |author3=Mikhelson, V. M. |s2cid=417046 |year=1997|title=Phylogenetic position of mammoth and Steller's sea cow within tethytheria demonstrated by mitochondrial DNA sequences|journal=Journal of Molecular Evolution|volume=44|issue=4|pages=406–13|doi=10.1007/PL00006160|pmid=9089080|bibcode=1997JMolE..44..406O}}</ref> | |||

| Three species of living elephants are recognised; the ] (''] africana''), ] (''Loxodonta cyclotis''), and ] (''] maximus'').<ref name=MSW3>{{cite book|author=Shoshani, J.|year=2005|contribution=Order Proboscidea|editor1=Wilson, D. E.|editor2=Reeder, D. M|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA91|title=Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference|volume=1|edition=3rd|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=90–91|isbn=978-0-8018-8221-0|oclc=62265494|access-date=11 November 2016|archive-date=1 February 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150201164505/http://www.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA91|url-status=live}}</ref> ]s were traditionally considered a single species, ''Loxodonta africana'', but molecular studies have affirmed their status as separate species.<ref name=DNA>{{cite journal|author1=Rohland, N. |author2=Reich, D. |author3=Mallick, S. |author4=Meyer, M. |author5=Green, R. E. |author6=Georgiadis, N. J. |author7=Roca, A. L. |author8=Hofreiter, M. | title =Genomic DNA Sequences from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep Speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants| journal = PLOS Biology | volume =8| issue =12| year =2010| doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564| page =e1000564 | pmid =21203580 | pmc =3006346| editor1-last =Penny| editor1-first =David |doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="Ishida">{{cite journal|author1=Ishida, Y. |author2=Oleksyk, T. K. |author3=Georgiadis, N. J. |author4=David, V. A. |author5=Zhao, K. |author6=Stephens, R. M. |author7=Kolokotronis, S.-O. |author8=Roca, A. L. |year=2011|title=Reconciling apparent conflicts between mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies in African elephants|journal=PLOS ONE|volume=6|issue=6|page=e20642|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0020642|editor1-last=Murphy|editor1-first=William J|pmid=21701575|pmc=3110795|bibcode=2011PLoSO...620642I|doi-access=free }}</ref><ref name="genomic">{{Cite journal|title = Elephant Natural History: A Genomic Perspective|journal = Annual Review of Animal Biosciences|date = 2015|pmid = 25493538|pages = 139–167|volume = 3|issue = 1|doi = 10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110838|first1 = Alfred L.|last1 = Roca|first2 = Yasuko|last2 = Ishida|first3 = Adam L.|last3 = Brandt|first4 = Neal R.|last4 = Benjamin|first5 = Kai|last5 = Zhao|first6 = Nicholas J.|last6 = Georgiadis}}</ref> ]s (''Mammuthus'') are nested within living elephants as they are more closely related to Asian elephants than to African elephants.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Roca |first1=Alfred L. |last2=Ishida |first2=Yasuko |last3=Brandt |first3=Adam L. |last4=Benjamin |first4=Neal R. |last5=Zhao |first5=Kai |last6=Georgiadis |first6=Nicholas J. |date=2015 |title=Elephant Natural History: A Genomic Perspective |journal=Annual Review of Animal Biosciences |volume=3 |issue=1 |pages=139–167 |doi=10.1146/annurev-animal-022114-110838 |pmid=25493538}}</ref> Another extinct genus of elephant, '']'', is also recognised, which appears to have close affinities with African elephants and to have hybridised with African forest elephants.<ref name="Palkopoulou">{{Cite journal |last1=Palkopoulou |first1=Eleftheria |last2=Lipson |first2=Mark |last3=Mallick |first3=Swapan |last4=Nielsen |first4=Svend |last5=Rohland |first5=Nadin |last6=Baleka |first6=Sina |last7=Karpinski |first7=Emil |last8=Ivancevic |first8=Atma M. |last9=To |first9=Thu-Hien |last10=Kortschak |first10=R. Daniel |last11=Raison |first11=Joy M. |date=2018-03-13 |title=A comprehensive genomic history of extinct and living elephants |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |language=en |volume=115 |issue=11 |pages=E2566–E2574 |doi=10.1073/pnas.1720554115 |issn=0027-8424 |pmc=5856550 |pmid=29483247 |bibcode=2018PNAS..115E2566P |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Swedish zoologist ] first ] the genus ''Elephas'' and an elephant from ] (then known as Ceylon) under the ] ''Elephas maximus'' in 1758. In 1798, ] classified the ] under the binomial ''Elephas indicus''. Dutch zoologist ] described the ] in 1847 under the binomial ''Elephas sumatranus''. English zoologist ] classified all three as ] of the Asian elephant in 1940.<ref name=Asian>{{cite journal|author=Shoshani, J.; Eisenberg, J. F.|year=1982|title=''Elephas maximus''|journal=Mammalian Species|volume=182|pages=1–8|url=http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-182-01-0001.pdf|jstor=3504045|doi=10.2307/3504045}}</ref> Asian elephants vary geographically in their colour and amount of depigmentation. The ] (''Elephas maximus maximus'') inhabits Sri Lanka, the Indian elephant (''E. m. indicus'') is native to mainland Asia (on the ] and ]), and the Sumatran elephant (''E. m. sumatranus'') is found in Sumatra.<ref name=Shoshani38/> One disputed subspecies, the ], lives in northern ] and is smaller than all the other subspecies. It has larger ears, a longer tail, and straighter tusks than the typical elephant. Sri Lankan zoologist ] described it in 1950 under the ] ''Elephas maximus borneensis'', taking as his ] an illustration in '']''.<ref name=Borneo>{{cite web|author=Cranbrook, E.; Payne, J.; Leh, C. M. U.|year=2008|title=Origin of the elephants ''Elephas maximus'' L. of Borneo|publisher=Sarawak Museum Journal|url=http://assets.panda.org/downloads/pages_from_originofelephants_in_borneofinal2oct07_2.pdf}}</ref> It was subsequently subsumed under either ''E. m. indicus'' or ''E. m. sumatranus''. Results of a 2003 ] indicate its ancestors ] from the mainland population about 300,000 years ago.<ref name=Fernando>{{cite journal|author=Fernando, P.; Vidya, T. N. C.; Payne, J.; Stuewe, M.; Davison, G.; Alfred, R. J.; Andau, P.; Bosi, E.; Kilbourn, A.; Melnick, D. J.|year=2003|title=DNA analysis indicates that Asian Elephants are native to Borneo and are therefore a high priority for conservation|journal=PLoS Biol|volume=1|issue=1|page=e6|doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0000006}}</ref> A 2008 study found that Borneo elephants are not indigenous to the island but were brought there before 1521 by the ] from ], where elephants are now extinct.<ref name=Borneo/> | |||

| ===Evolution=== | |||

| ], Gabon]] | |||

| Over 180 extinct members of order Proboscidea have been described.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Kingdon|first1=J. |title=Mammals of Africa |date=2013|publisher=Bloomsbury|page=173 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B_07noCPc4kC |isbn=9781408189962 |access-date=6 June 2020|archive-date=21 March 2023|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20230321084755/https://books.google.com/books?id=B_07noCPc4kC|url-status=live}}</ref> The earliest proboscideans, the African '']'' and '']'' are known from the late ].<ref name="Gheerbrant">{{cite journal |author=Gheerbrant, E. |year=2009 |title=Paleocene emergence of elephant relatives and the rapid radiation of African ungulates |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America |volume=106 |issue=26 |pages=10717–10721 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0900251106 |pmid=19549873 |pmc=2705600|bibcode=2009PNAS..10610717G |doi-access=free}}</ref> The ] included '']'', ''],'' and '']'' from Africa. These animals were relatively small and, some, like ''Moeritherium'' and ''Barytherium'' were probably amphibious.<ref name=Sukumar13 /><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Liu |first1=A. G. S. C. |last2=Seiffert |first2=E. R. |last3=Simons |first3=E. L. |date=2008 |title=Stable isotope evidence for an amphibious phase in early proboscidean evolution |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=105 |issue=15 |pages=5786–5791 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0800884105 |pmc=2311368 |pmid=18413605 |bibcode=2008PNAS..105.5786L |doi-access=free}}</ref> Later on, genera such as '']'' and '']'' arose; the latter likely inhabited more forested areas. Proboscidean diversification changed little during the Oligocene.<ref name="Sukumar13">Sukumar, pp. 13–16.</ref> One notable species of this epoch was '']'' of the ], which may have been an ancestor to several later species.<ref name=link>{{cite journal|author1=Shoshani, J. |author2=Walter, R. C. |author3=Abraha, M. |author4=Berhe, S. |author5=Tassy, P. |author6=Sanders, W. J. |author7=Marchant, G. H. |author8=Libsekal, Y. |author9=Ghirmai, T. |author10=Zinner, D. |year=2006|title=A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a "missing link" between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences |volume=103|issue=46|pages=17296–17301|doi=10.1073/pnas.0603689103 |bibcode=2006PNAS..10317296S |pmid=17085582 |pmc=1859925|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| The African elephant was first named by German naturalist ] in 1797 as ''Elephas africana''.<ref name=African>{{cite journal|author=Laursen, L.; Bekoff, M.|year=1978|title=''Loxodonta africana''|journal=Mammalian Species|volume=92|pages=1–8|url=http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-092-01-0001.pdf|jstor=3503889|doi=10.2307/3503889|issue=92}}</ref> The genus ''Loxodonta'' was commonly believed to have been named by Georges Cuvier in 1825. Cuvier spelled it ''Loxodonte'' and an anonymous author ] the spelling to ''Loxodonta''; the ] recognises this as the proper authority.<ref name=MSW3>{{cite book|author=Shoshani, J.|year=2005|contribution=Order Proboscidea|editor=Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M|url=http://www.google.com/books?id=JgAMbNSt8ikC&pg=PA91#v=onepage&q&f=false|title=Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference, Volume 1|edition= 3rd|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|pages=90–91|isbn=978-0-8018-8221-0|oclc=62265494}}</ref> In 1942, 18 subspecies of African elephant were recognised by ], but further morphological data has reduced the number of classified subspecies,<ref>Sukumar, p. 46.</ref> and by the 1990s, only two were recognised, the savannah or ] (''L. a. africana'') and the ] (''L. a. cyclotis'');<ref>{{cite journal|author=Barnes, R. F. W.; Blom, A.; Alers M. P. T.|year=1995|title=A review of the status of forest elephants ''Loxodonta africana'' in Central Africa|journal=Biological Conservation|volume=71|issue=2|pages=125–32|doi=10.1016/0006-3207(94)00014-H}}</ref> the latter has smaller and more rounded ears and thinner and straighter tusks, and is limited to the forested areas of ] and ].<ref name=Shoshani42/> A 2000 study argued for the elevation of the two forms into separate species (''L. africana'' and ''L. cyclotis'' respectively) based on differences in skull morphology.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Grubb, P.; Groves, C. P.; Dudley J. P.; Shoshani, J.| year=2000|title=Living African elephants belong to two species: ''Loxodonta africana'' (Blumenbach, 1797) and ''Loxodonta cyclotis'' (Matschie, 1900)|journal=Elephant|volume=2|issue=4|pages=1–4|url=http://arts.anu.edu.au/grovco/Loxodonta%20cyclotis.pdf}}</ref> DNA studies published in 2001 and 2007 also suggested they were distinct species,<ref name=outgroup>{{cite journal|author=Rohland, N.|year=2007|title=Proboscidean mitogenomics: chronology and mode of elephant evolution using mastodon as outgroup|journal=PLoS Biology|volume=5|issue=8|page=e207|doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207|last2=Malaspinas|first2=Anna-Sapfo|last3=Pollack|first3=Joshua L.|last4=Slatkin|first4=Montgomery|last5=Matheus|first5=Paul|last6=Hofreiter|first6=Michael}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal| author =Roca, A. L.; Georgiadis, N.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; O'Brien, S. J. | title =Genetic evidence for two species of elephant in Africa| journal =Science | volume =293 | issue =5534| pages =1473–77 | year =2001| doi =10.1126/science.1059936| pmid =11520983}}</ref> while studies in 2002 and 2005 concluded that they were the same species.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Eggert, L. S.; Rasner, C. A.; Woodruff, D. S.|year=2002|title=The evolution and phylogeography of the African elephant inferred from mitochondrial DNA sequence and nuclear microsatellite markers|journal=Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences|volume=269|issue=1504|pages=1993–2006|doi=10.1098/rspb.2002.2070}}</ref><ref name=Debruyne>{{cite journal|author=Debruyne, R.|year=2005|title=A case study of apparent conflict between molecular phylogenies: the interrelationships of African elephants|journal=Cladistics|volume=21|issue=1|pages=31–50|doi=10.1111/j.1096-0031.2004.00044.x}}</ref> A 2010 study further supported African savannah and forest elephants' status as separate species.<ref name=DNA>{{cite journal| author =Rohland, N.; Reich, D.; Mallick, S.; Meyer, M.; Green, R. E.; Georgiadis, N. J.; Roca, A. L.; Hofreiter, M.| title =Genomic DNA Sequences from Mastodon and Woolly Mammoth Reveal Deep Speciation of Forest and Savanna Elephants| journal = PLoS Biology | volume =8| issue =12| year =2010| doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.1000564| page =e1000564 | pmid =21203580 | pmc =3006346| editor1-last =Penny| editor1-first =David}}</ref> As of 2011, the ] designations of African elephants were still debated.<ref name="Ishida">{{cite journal|author=Ishida, Y.; Oleksyk, T. K.; Georgiadis, N. J.; David, V. A.; Zhao, K.; Stephens, R. M.; Kolokotronis, S.-O.; Roca, A. L.|year=2011|title=Reconciling apparent conflicts between mitochondrial and nuclear phylogenies in African elephants|journal=PLoS ONE|volume=6|issue=6|page=e20642|doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0020642|editor1-last=Murphy|editor1-first=William J}}</ref> The third edition of '']'' lists the two forms as full species<ref name=MSW3/> and does not list any subspecies in its entry for ''Loxodonta africana''.<ref name=MSW3/> This approach is not taken by the ]'s ] nor by the IUCN, both of which list ''L. cyclotis'' as a ] of ''L. africana''.<ref name=IUCN/><ref>{{cite web|title=''Loxodonta cyclotis'' (Matschie, 1900)|publisher=UNEP-WCMC Species Database|accessdate=12 December 2012|url=http://www.unep-wcmc-apps.org/isdb/Taxonomy/tax-species-result.cfm?displaylanguage=ENG&Genus=%2525Loxodonta%2525&source=animals&speciesNo=71831&Country=&tabname=names}}</ref> Some evidence suggests that elephants of western Africa are a separate species,<ref>{{cite journal|author=Eggert, L. S. Eggert, J. A. Woodruff, D. S.|year=2003|title=Estimating population sizes for elusive animals: the forest elephants of Kakum National Park, Ghana|journal=Molecular Ecology|volume=12|issue=6|pages=1389–1402|doi=10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01822.x|url=http://labs.biology.ucsd.edu/woodruff/pubs/210.pdf|pmid=12755869}}</ref> although this is disputed.<ref name=Debruyne/><ref name="Ishida"/> The ]s of the ], which have been suggested to be a separate species (''Loxodonta pumilio'') are probably forest elephants whose small size and/or early maturity are due to environmental conditions.<ref>{{cite journal | author = Debruyne, R.; Van Holt, A.; Barriel, V.; Tassy, P.;| year = 2003 | title = Status of the so-called African pygmy elephant (''Loxodonta pumilio'' (NOACK 1906)): phylogeny of cytochrome b and mitochondrial control region sequences | journal = Comptes Rendus de Biologie | volume = 326 | issue = 7 | pages = 687–97 | pmid = 14556388|url=http://regis.cubedeglace.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/debruyne_et_al_20032.pdf | doi = 10.1016/S1631-0691(03)00158-6}}</ref> | |||

| {{cladogram|style=font-size:70%|caption=Proboscidea phylogeny based on morphological and DNA evidence<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Baleka|first1=S. |last2=Varela |first2=L. |last3=Tambusso|first3=P. S.|last4=Paijmans|first4=J. L. A.|last5=Mothé|first5=D. |last6=Stafford Jr.|first6=T. W. |last7=Fariña|first7=R. A. |last8=Hofreiter |first8=M. |year=2022|title=Revisiting proboscidean phylogeny and evolution through total evidence and palaeogenetic analyses including ''Notiomastodon'' ancient DNA |journal=iScience |volume=25|issue=1 |page=103559 |doi=10.1016/j.isci.2021.103559 |pmid=34988402 |pmc=8693454 |bibcode=2022iSci...25j3559B}}</ref><ref>{{Cite book |last1=Benoit |first1=J. |chapter=Paleoneurology of the Proboscidea (Mammalia, Afrotheria): Insights from Their Brain Endocast and Labyrinth |date=2023 |title=Paleoneurology of Amniotes |pages=579–644 |editor-last=Dozo |editor-first=M. T. |place=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |doi=10.1007/978-3-031-13983-3_15 |isbn=978-3-031-13982-6 |last2=Lyras |first2=G. A. |last3=Schmitt |first3=A. |last4=Nxumalo |first4=M. |last5=Tabuce |first5=R. |last6=Obada |first6=T. |last7=Mararsecul |first7=V. |last8=Manger |first8=P. |editor2-last=Paulina-Carabajal |editor2-first=A. |editor3-last=Macrini |editor3-first=T. E. |editor4-last=Walsh |editor4-first=S.}}</ref><ref name=Palkopoulou/> | |||

| ===Evolution and extinct relatives=== | |||

| |align=right | |||

| ], ]]] | |||

| |{{clade | |||

| Over 161 extinct members and three major ] of the order Proboscidea have been recorded. The earliest proboscids, the African '']'' and '']'' of the late ], heralded the first radiation.<ref name="Gheerbrant">{{cite journal |author=Gheerbrant, E. |year=2009 |title=Paleocene emergence of elephant relatives and the rapid radiation of African ungulates |journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) |volume=106 |issue=26 |pages=10717–10721 |doi=10.1073/pnas.0900251106 |url=http://www.pnas.org/content/106/26/10717.full |pmid=19549873 |pmc=2705600}}</ref> The ] included ] from the Indian subcontinent and '']'', '']'' and '']'' from Africa. These animals were relatively small and aquatic. Later on, genera such as '']'' and '']'' arose; the latter likely inhabited forests and open woodlands. Proboscidean diversity declined during the Oligocene.<ref>Sukumar, pp. 13–16.</ref> One notable species of this epoch was '']'' of the ], which may have been an ancestor to several later species.<ref name=link>{{cite journal|author=Shoshani, J.; Walter, R. C.; Abraha, M.; Berhe, S.; Tassy, P.; Sanders, W. J.; Marchant, G. H.; Libsekal, Y.; Ghirmai, T.; Zinner, D.|year=2006|title=A proboscidean from the late Oligocene of Eritrea, a "missing link" between early Elephantiformes and Elephantimorpha, and biogeographic implications|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=103|issue=46|pages=17296–301|doi=10.1073/pnas.0603689103}}</ref> The beginning of the ] saw the second diversification, with the appearance of the ] and the ]. The former were related to ''Barytherium'', lived in Africa and Eurasia,<ref name=Sukumar17>Sukumar, pp. 16–19.</ref> while the latter may have descended from ''Eritreum''<ref name=link/> and spread to North America.<ref name=Sukumar17/> | |||

| |label1=] | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |1=early proboscideans, e.g. '']'' ] | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1=] <span style="{{MirrorH}}">]</span> | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1=] <span style="{{MirrorH}}">]</span> | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1=] ] | |||

| |label2=] | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1={{clade | |||

| |1='']'' <span style="{{MirrorH}}">]</span> | |||

| |2='']'' ] | |||

| }} | |||

| |2={{clade | |||

| |1='']'' ] | |||

| |2='']'' <span style="{{MirrorH}}">]</span> | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| }} | |||

| A major event in proboscidean evolution was the collision of Afro-Arabia with Eurasia, during the Early Miocene, around 18–19 million years ago, allowing proboscideans to disperse from their African homeland across Eurasia and later, around 16–15 million years ago into North America across the ]. Proboscidean groups prominent during the Miocene include the ]s, along with the more advanced ], including ] (mastodons), ]s, ] (which includes the "shovel tuskers" like '']''), ] and ].<ref name=Cantalapiedra-2021>{{Cite journal |last1=Cantalapiedra |first1=J. L. |last2=Sanisidro |first2=Ó. |last3=Zhang |first3=H. |last4=Alberdi |first4=M. T. |last5=Prado |first5=J. L. |last6=Blanco |first6=F. |last7=Saarinen |first7=J. |date=2021 |title=The rise and fall of proboscidean ecological diversity |url=https://www.nature.com/articles/s41559-021-01498-w |journal=Nature Ecology & Evolution |volume=5 |issue=9 |pages=1266–1272 |doi=10.1038/s41559-021-01498-w |pmid=34211141 |bibcode=2021NatEE...5.1266C |s2cid=235712060}}</ref> Around 10 million years ago, the earliest members of the family ] emerged in Africa, having originated from gomphotheres.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Saegusa, H. |author2=Nakaya, H. |name-list-style=amp |author3=Kunimatsu, Y. |author4=Nakatsukasa, M. |author5=Tsujikawa, H. |author6=Sawada, Y. |author7=Saneyoshi, M. |author8=Sakai, T. |year=2014 |chapter=Earliest elephantid remains from the late Miocene locality, Nakali, Kenya |page=175 |chapter-url=https://apo.ansto.gov.au/dspace/bitstream/10238/9340/2/icmr_volume_low.pdf#page=188 |editor1=Kostopoulos, D. S. |editor2=Vlachos, E. |editor3=Tsoukala, E. |title=VIth International Conference on Mammoths and Their Relatives |volume=102 |location=Thessaloniki |publisher=School of Geology, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki |isbn=978-960-9502-14-6}}</ref> | |||

| Elephantids are distinguished from earlier proboscideans by a major shift in the molar morphology to parallel lophs rather than the cusps of earlier proboscideans, allowing them to become higher-crowned (hypsodont) and more efficient in consuming grass.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Lister |first=A. M. |date=2013 |title=The role of behaviour in adaptive morphological evolution of African proboscideans |doi=10.1038/nature12275 |journal=Nature |volume=500 |issue=7462 |pages=331–334 |pmid=23803767 |bibcode=2013Natur.500..331L |s2cid=883007}}</ref> The Late Miocene saw major climactic changes, which resulted in the decline and extinction of many proboscidean groups.<ref name="Cantalapiedra-2021" /> The earliest members of the modern genera of Elephantidae appeared during the latest Miocene–early Pliocene around 5 million years ago. The elephantid genera ''Elephas'' (which includes the living Asian elephant) and ''Mammuthus'' (mammoths) migrated out of Africa during the late Pliocene, around 3.6 to 3.2 million years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Iannucci |first1=Alessio |last2=Sardella |first2=Raffaele |date=2023-02-28 |title=What Does the "Elephant-''Equus''" Event Mean Today? Reflections on Mammal Dispersal Events around the Pliocene-Pleistocene Boundary and the Flexible Ambiguity of Biochronology |journal=Quaternary |volume=6 |issue=1 |page=16 |doi=10.3390/quat6010016 |doi-access=free |hdl=11573/1680082 |hdl-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| The second radiation was represented by the emergence of the ]s in the Miocene,<ref name=Sukumar17/> which likely evolved from ''Eritreum''<ref name=link/> and originated in Africa, spreading to every continent except Australia and Antarctica. Members of this group included '']'' and '']''.<ref name=Sukumar17/> The third radiation started in the late Miocene and led to the arrival of the elephantids, which descended from, and slowly replaced, the gomphotheres.<ref>Sukumar, p. 22.</ref> The African '']'' gave rise to ''Loxodonta'', ''Mammuthus'' and ''Elephas''. ''Loxodonta'' branched off earliest, around the Miocene and ] boundary, while ''Mammuthus'' and ''Elephas'' diverged later during the early Pliocene. ''Loxodonta'' remained in Africa, while ''Mammuthus'' and ''Elephas'' spread to Eurasia, and the former reached North America. At the same time, the ], another proboscidean group descended from gomphotheres, spread throughout Asia, including the Indian subcontinent, China, southeast Asia and Japan. Mammutids continued to evolve into new species, such as the ].<ref>Sukumar, pp. 24–27.</ref> | |||

| ], Victoria, British Columbia]] | |||

| At the beginning of the ], elephantids experienced a high rate of ]. '']'' became the most common species in northern and southern Africa but was replaced by ''Elephas iolensis'' later in the Pleistocene. Only when ''Elephas'' disappeared from Africa did ''Loxodonta'' become dominant once again, this time in the form of the modern species. ''Elephas'' diversified into new species in Asia, such as ''E. hysudricus'' and ''E. platycephus'';<ref name=Sukumar28/> the latter the likely ancestor of the modern Asian elephant.<ref>Sukumar, p. 44.</ref> ''Mammuthus'' evolved into several species, including the well-known ].<ref name=Sukumar28>Sukumar, pp. 28–31.</ref> In the ], most proboscidean species vanished during the ] which ] 50% of genera weighing over {{convert|5|kg|lb|abbr=on}} worldwide.<ref>Sukumar, pp. 36–37.</ref> | |||

| Over the course of the ], all non-elephantid probobscidean genera outside of the Americas became extinct with the exception of '']'',<ref name="Cantalapiedra-2021" /> with gomphotheres dispersing into South America as part of the ],<ref name="Mothé et al 2016 (In Press)">{{cite journal |last1=Mothé |first1=Dimila |last2=dos Santos Avilla |first2=Leonardo |last3=Asevedo |first3=Lidiane |last4=Borges-Silva |first4=Leon |last5=Rosas |first5=Mariane |last6=Labarca-Encina |first6=Rafael |last7=Souberlich |first7=Ricardo |last8=Soibelzon |first8=Esteban |last9=Roman-Carrion |first9=José Luis |last10=Ríos |first10=Sergio D. |last11=Rincon |first11=Ascanio D. |last12=Cardoso de Oliveira |first12=Gina |last13=Pereira Lopes |first13=Renato |date=30 September 2016 |title=Sixty years after 'The mastodonts of Brazil': The state of the art of South American proboscideans (Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) |url=http://bibdigital.epn.edu.ec/bitstream/15000/17075/1/Moth%c3%a9%20et%20al.%2c%202016%20-%20Sixty%20years%20proboscideans.pdf |journal=Quaternary International |volume=443 |pages=52–64 |bibcode=2017QuInt.443...52M |doi=10.1016/j.quaint.2016.08.028}}</ref> and mammoths migrating into North America around 1.5 million years ago.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Lister |first1=A. M. |last2=Sher |first2=A. V. |date=2015 |title=Evolution and dispersal of mammoths across the Northern Hemisphere |journal=Science |volume=350 |issue=6262 |pages=805–809 |bibcode=2015Sci...350..805L |doi=10.1126/science.aac5660 |pmid=26564853 |s2cid=206639522}}</ref> At the end of the Early Pleistocene, around 800,000 years ago the elephantid genus '']'' dispersed outside of Africa, becoming widely distributed in Eurasia.<ref>{{Cite book |last=Lister |first=A. M. |chapter=Ecological Interactions of Elephantids in Pleistocene Eurasia |date=2004 |chapter-url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264788794 |title=Human Paleoecology in the Levantine Corridor |pages=53–60 |publisher=Oxbow Books |isbn=978-1-78570-965-4}}</ref> Proboscideans were represented by around 23 species at the beginning of the ]. Proboscideans underwent a dramatic decline during the Late Pleistocene as part of the ] of most large mammals globally, with all remaining non-elephantid proboscideans (including ''Stegodon'', ]s, and the American gomphotheres '']'' and '']'') and '']'' becoming extinct, with mammoths only surviving in ] populations on islands around the ] into the Holocene, with their latest survival being on ], where they persisted until around 4,000 years ago.<ref name=Cantalapiedra-2021/><ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Rogers |first1=R. L. |last2=Slatkin |first2=M. |date=2017 |title=Excess of genomic defects in a woolly mammoth on Wrangel island |journal=PLOS Genetics |volume=13 |issue=3 |page=e1006601 |doi=10.1371/journal.pgen.1006601 |issn=1553-7404 |pmc=5333797 |pmid=28253255 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| Proboscideans experienced several evolutionary trends, such as an increase in size, which led to many giant species that stood up to {{convert|4|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} tall.<ref name=evolution/> As with other ]s, including the extinct ], the large size of elephants likely developed to allow them to survive on vegetation with low nutritional value.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Carpenter, K. |year=2006 |chapter=Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod ''Amphicoelias fragillimus'' Cope, 1878 |editor-last=Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G. (eds.) |title= Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation |series=New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin |publisher=New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science |volume=36 |pages=131–138}}</ref> Their limbs grew longer and the feet shorter and broader. Early proboscideans developed longer ]s and smaller ], while more advanced ones developed shorter mandibles, which shifted the head's ]. The skull grew larger, especially the cranium, while the neck shortened to provide better support for the skull. The increase in size led to the development and elongation of the mobile trunk to provide reach. The number of ]s, incisors and ] decreased. The cheek teeth (molars and premolars) became larger and more specialised. The upper second incisors grew into tusks, which varied in shape from straight, to curved (either upward or downward), to spiralled, depending on the species. Some proboscideans developed tusks from their lower incisors.<ref name=evolution>{{cite journal|author=Shoshani, J.|year=1998|title=Understanding proboscidean evolution: a formidable task|journal=Trends in Ecology and Evolution|volume=13|issue=12|pages=480–87|doi=10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01491-8}}</ref> Elephants retain certain features from their aquatic ancestry such as their ] anatomy and the internal ] of the males.<ref name=snorkel/> | |||

| Over the course of their evolution, probobscideans grew in size. With that came longer limbs and wider feet with a more ] stance, along with a larger head and shorter neck. The trunk evolved and grew longer to provide reach. The number of premolars, incisors, and canines decreased, and the cheek teeth (molars and premolars) became longer and more specialised. The incisors developed into tusks of different shapes and sizes.<ref name=evolution/> Several species of proboscideans became isolated on islands and experienced ],<ref name=Sukumar31>Sukumar, pp. 31–33.</ref> some dramatically reducing in body size, such as the {{Cvt|1|m}} tall ] species '']''.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Romano |first1=M. |last2=Manucci |first2=F. |last3=Palombo |first3=M. R. |date=2021 |title=The smallest of the largest: new volumetric body mass estimate and in-vivo restoration of the dwarf elephant Palaeoloxodon ex gr. ''P. falconeri'' from Spinagallo Cave (Sicily) |journal=Historical Biology |volume=33 |issue=3 |pages=340–353 |doi=10.1080/08912963.2019.1617289 |bibcode=2021HBio...33..340R |s2cid=181855906}}</ref> | |||

| There has been some debate over the relationship of ''Mammuthus'' to ''Loxodonta'' or ''Elephas''. Some ] studies suggest ''Mammuthus'' is more closely related to the former,<ref>{{cite journal|author=Debruyne, R.; Barriel, V.; Tassy, P.|year=2003|title=Mitochondrial cytochrome ''b'' of the Lyakhov mammoth (Proboscidea, Mammalia): new data and phylogenetic analyses of Elephantidae|journal=Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution|volume=26|issue=3|pages=421–34|pmid=12644401|url=http://regis.cubedeglace.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/02/debruyne_et_al_20031.pdf|doi=10.1016/S1055-7903(02)00292-0}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author=Noro, M.; Masuda, R.; Dubrovo, I. A.; Yoshida, M. C.; Kato, M.|year=1998|title=Molecular phylogenetic inference of the woolly mammoth ''Mammuthus primigenius'', based on complete sequences of mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12S ribosomal RNA genes|journal=Journal of Molecular Evolution|volume=46|issue=3|pages=314–26|doi=10.1007/PL00006308|pmid=9493356}}</ref> while others point to the latter.<ref name=Ozawa2>{{cite journal|author=Ozawa, T.; Hayashi, S.; Mikhelson, V. M.|year=1997|title=Phylogenetic position of mammoth and Steller's sea cow within tethytheria demonstrated by mitochondrial DNA sequences|journal=Journal of Molecular Evolution|volume=44|issue=4|pages=406–13|doi=10.1007/PL00006160|pmid=9089080}}</ref> However, analysis of the complete ] profile of the woolly mammoth (sequenced in 2005) supports ''Mammuthus'' being more closely related to ''Elephas''.<ref name=outgroup/><ref name=DNA/><ref>{{cite journal|author=Gross, L.|year=2006|title=Reading the evolutionary history of the Woolly Mammoth in its mitochondrial genome|journal=PLoS Biology|volume=4|issue=3|page=e74|doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0040074}}</ref> ] evidence supports ''Mammuthus'' and ''Elephas'' as ], while comparisons of ] and ] have concluded that all three genera are equally related to each other.<ref>Sukumar, pp. 46–47.</ref> Some scientists believe a ] mammoth ] could one day be implanted in an Asian elephant's womb.<ref>{{cite web|author=Choi, C.|year=2011|title=Woolly Mammoths Could Be Cloned Someday, Scientist Says|publisher=Live Science|url=http://www.livescience.com/17386-woolly-mammoth-clone.html|accessdate=18 September 2012}}</ref> | |||

| === |

===Living species=== | ||

| {| class="wikitable" | |||

| {{main|Dwarf elephant}} | |||

| |+ style="text-align: centre;" | | |||

| ] | |||

| ! Name | |||

| Several species of proboscideans lived on islands and experienced ]. This occurred primarily during the Pleistocene, when some elephant populations became isolated by fluctuating sea levels, although dwarf elephants did exist earlier in the Pliocene. These elephants likely grew smaller on islands due to a lack of large or viable predator populations and limited resources. By contrast, small mammals such as rodents develop ] in these conditions. Dwarf proboscideans are known to have lived in ], the ], and several islands of the ].<ref name=Sukumar31/> | |||

| ! Size | |||

| ! Appearance | |||

| ! Distribution | |||

| ! Image | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (''Loxodonta africana'') | |||

| | '''Male''': {{cvt|304|-|336|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}} (shoulder height), {{cvt|5.2|-|6.9|MT|ST|1|abbr=on}} (weight); '''Female''': {{cvt|247|-|273|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}} (shoulder height), {{cvt|2.6|-|3.5|MT|ST|1|abbr=on}} (weight).<ref name="Larramendi, A. 2015">{{cite journal |author=Larramendi, A. |year=2015 |title=Shoulder height, body mass and shape of proboscideans |journal=Acta Palaeontologica Polonica |doi=10.4202/app.00136.2014 |doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| | Relatively large and triangular ears, concave back, diamond shaped molar ridges, wrinkled skin, sloping abdomen, and two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk.<ref name=Shoshani38>Shoshani, pp. 38–41.</ref> | |||

| | ]; forests, savannahs, deserts, wetlands, and near lakes.<ref name=Shoshani42>Shoshani, pp. 42–51.</ref> | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (''Loxodonta cyclotis'') | |||

| | {{cvt|209|-|231|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}} (shoulder height), {{cvt|1.7|-|2.3|MT|ST|1|abbr=on}} (weight).<ref name="Larramendi, A. 2015"/> | |||

| | Similar to the bush species, but with smaller and more rounded ears and thinner and straighter tusks.<ref name=Shoshani38/><ref name=Shoshani42 /> | |||

| | ] and ]; ], but occasionally ]s and forest/grassland ]s.<ref name=Shoshani42 /> | |||

| |] | |||

| |- | |||

| | ] (''Elephas maximus'') | |||

| | '''Male''': {{cvt|261|-|289|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}} (shoulder height), {{cvt|3.5|-|4.6|MT|ST|1|abbr=on}} (weight); '''Female''': {{cvt|228|-|252|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}} (shoulder height), {{cvt|2.3|-|3.1|MT|ST|1|abbr=on}} (weight).<ref name="Larramendi, A. 2015"/> | |||

| | Relatively small ears, convex or level back, dish-shaped forehead with two large bumps, narrow molar ridges, smooth skin with some blotches of ], a straightened or saggy abdomen, and one extension at the tip of the trunk.<ref name=Shoshani38/> | |||

| |] and ]; habitats with a mix of grasses, low woody plants, and trees, including dry ] in southern India and Sri Lanka and ]s in ].<ref name=Shoshani42/><ref name=Asian>{{cite journal|author1=Shoshani, J.|author2=Eisenberg, J. F.|year=1982|title=''Elephas maximus''|journal=Mammalian Species|issue=182|pages=1–8|url=http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-182-01-0001.pdf|jstor=3504045|doi=10.2307/3504045|access-date=27 October 2012|archive-date=24 September 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150924121940/http://www.science.smith.edu/msi/pdf/i0076-3519-182-01-0001.pdf|url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| |] | |||

| |} | |||

| ==Anatomy== | |||

| '']'' of ] is believed to have descended from '']''. '']'' of ] and ] was only {{convert|1|m|ft|0|abbr=on}}, and had probably evolved from the ]. Other descendants of the straight-tusked elephant existed in ]. Dwarf elephants of uncertain descent lived in ], ] and ], while dwarf mammoths are known to have lived in ].<ref name=Sukumar31>Sukumar, pp. 31–33.</ref> The ] colonised the ] and evolved into the ]. This species reached a height of {{convert|1.2|–|1.8|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} and weighed {{convert|200|–|2000|kg|lb|abbr=on}}. A population of small woolly mammoths survived on ] as recently as 4,000 years ago.<ref name=Sukumar31/> After their discovery in 1993, they were considered dwarf mammoths.<ref name=Nature>{{cite journal | author = Vartanyan, S. L., Garutt, V. E., Sher, A. V. | month = | year = 1993 | title = Holocene dwarf mammoths from Wrangel Island in the Siberian Arctic | journal = ] | volume = 362 | pages = 337–40 | doi=10.1038/362337a0 | issue=6418}}</ref> This classification has been re-evaluated and since the ] in 1999, these animals are no longer considered to be true "dwarf mammoths".<ref>{{cite journal |author=Tikhonov, A.; Agenbroad, L.; Vartanyan, S. |year=2003 |month= |title=Comparative analysis of the mammoth populations on Wrangel Island and the Channel Islands |journal=Deinsea |volume=9 |issue= |pages=415–20 |issn=0923-9308}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| Elephants are the largest living terrestrial animals. Some species of the extinct elephant genus '']'' considerably exceeded modern elephants in size making them among the largest land mammals ever.<ref name="Larramendi, A. 2015" /> The skeleton is made up of 326–351 bones.<ref name=Shoshani68 /> The vertebrae are connected by tight joints, which limit the backbone's flexibility. African elephants have 21 pairs of ribs, while Asian elephants have 19 or 20 pairs.<ref>{{cite web|author=Somgrid, C.|title=Elephant Anatomy and Biology: Skeletal system|publisher=Elephant Research and Education Center, Department of Companion Animal and Wildlife Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University|url=http://www.asianelephantresearch.com/about-elephant-anatomy-and-biology-p1.php#skeleton|access-date=21 September 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120613191055/http://www.asianelephantresearch.com/about-elephant-anatomy-and-biology-p1.php#skeleton|archive-date=13 June 2012|url-status=dead}}</ref> The skull contains air cavities (]) that reduce the weight of the skull while maintaining overall strength. These cavities give the inside of the skull a ]-like appearance. By contrast, the lower jaw is dense. The cranium is particularly large and provides enough room for the attachment of muscles to support the entire head.<ref name=Shoshani68>Shoshani, pp. 68–70.</ref> The skull is built to withstand great stress, particularly when fighting or using the tusks. The brain is surrounded by arches in the skull, which serve as protection.<ref>Kingdon, p. 11.</ref> Because of the size of the head, the neck is relatively short to provide better support.<ref name="evolution">{{cite journal |author=Shoshani, J. |year=1998 |title=Understanding proboscidean evolution: a formidable task |journal=Trends in Ecology and Evolution |volume=13 |issue=12 |pages=480–487 |doi=10.1016/S0169-5347(98)01491-8 |pmid=21238404|bibcode=1998TEcoE..13..480S }}</ref> | |||

| Elephants are ] and maintain their average body temperature at ~ 36 °C (97 °F), with a minimum of 35.2 °C (95.4 °F) during the cool season, and a maximum of 38.0 °C (100.4 °F) during the hot dry season.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=2018|title=Savanna elephants maintain homeothermy under African heat|url=https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00360-018-1170-5|journal=Journal of Comparative Physiology B|doi=10.1007/s00360-018-1170-5|last1=Mole|first1=Michael A.|last2=Rodrigues Dáraujo|first2=Shaun|last3=Van Aarde|first3=Rudi J.|last4=Mitchell|first4=Duncan|last5=Fuller|first5=Andrea|volume=188|issue=5|pages=889–897|pmid=30008137|s2cid=51626564|access-date=14 May 2021|archive-date=15 May 2021|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210515162738/https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00360-018-1170-5|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| == |

===Ears and eyes=== | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| Elephant ear flaps, or ], are {{convert|1|–|2|mm|in|abbr=on}} thick in the middle with a thinner tip and supported by a thicker base. They contain numerous blood vessels called ]. Warm blood flows into the capillaries, releasing excess heat into the environment. This effect is increased by flapping the ears back and forth. Larger ear surfaces contain more capillaries, and more heat can be released. Of all the elephants, African bush elephants live in the hottest climates and have the largest ear flaps.<ref name=Shoshani68 /><ref>{{cite journal|author=Narasimhan, A.|s2cid=121443269|year=2008|title=Why do elephants have big ear flaps?|journal=Resonance|volume=13|issue=7|pages=638–647|doi=10.1007/s12045-008-0070-5}}</ref> The ] are adapted for hearing low frequencies, being most sensitive at 1 ].<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Reuter, T.|author2=Nummela, S.|author3=Hemilä, S.|year=1998|title=Elephant hearing|journal=Journal of the Acoustical Society of America|volume=104|issue=2|pages=1122–1123|url=http://roadecology.ucdavis.edu/%5C/pdflib/Winter2005/Rodwell_Reuter_ele_ear.pdf|doi=10.1121/1.423341|pmid=9714930|bibcode=1998ASAJ..104.1122R|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20121207065356/http://roadecology.ucdavis.edu/pdflib/Winter2005/Rodwell_Reuter_ele_ear.pdf|archive-date=7 December 2012|df=dmy-all}}</ref> | |||

| Elephants are the largest living terrestrial animals. African elephants stand {{convert|3|–|4|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} and weigh {{convert|4000|–|7000|kg|lb|abbr=on}} while Asian elephants stand {{convert|2|–|3.5|m|ft|0|abbr=on}} and weigh {{convert|3000|–|5000|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=Shoshani38/> In both cases, males are larger than females.<ref name=Asian/><ref name=African/> Among African elephants, the forest form is smaller than the savannah form.<ref name=Shoshani42/> The skeleton of the elephant is made up of 326–351 bones.<ref name=Shoshani68/> The vertebrae are connected by tight joints, which limit the backbone's flexibility. African elephants have 21 pairs of ribs, while Asian elephants have 19 or 20 pairs.<ref>{{cite web|author=Somgrid, C.|title=Elephant Anatomy and Biology: Skeletal system|publisher=Elephant Research and Education Center, Department of Companion Animal and Wildlife Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University | |||

| |url=http://www.asianelephantresearch.com/about-elephant-anatomy-and-biology-p1.php#skeleton|accessdate=21 September 2012}}</ref> | |||

| Lacking a ] (tear duct), the eye relies on the ] in the orbit to keep it moist. A durable ] shields the globe. The animal's ] is compromised by the location and limited mobility of the eyes.<ref name="sense">{{cite web|author=Somgrid, C.|title=Elephant Anatomy and Biology: Special sense organs|publisher=Elephant Research and Education Center, Department of Companion Animal and Wildlife Clinics, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Chiang Mai University|url=http://www.asianelephantresearch.com/about-elephant-anatomy-and-biology-p4.php#Special|access-date=21 September 2012|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130729045534/http://www.asianelephantresearch.com/about-elephant-anatomy-and-biology-p4.php#Special|archive-date=29 July 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> Elephants are ]<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Yokoyama, S. |author2=Takenaka, N. |author3=Agnew, D. W. |author4=Shoshani, J. |year=2005|title=Elephants and human color-blind deuteranopes have identical sets of visual pigments|journal=Genetics|volume=170|issue=1|pages=335–344|doi=10.1534/genetics.104.039511|pmid=15781694|pmc=1449733}}</ref> and they can see well in dim light but not in bright light.<ref name=cognition /> | |||

| ===Ears=== | |||

| ] | |||

| Elephant ears have thick bases with thin tips. The ear flaps, or ], contain numerous blood vessels called ]. Warm blood flows into the capillaries, helping to release excess body heat into the environment. This occurs when the pinnae are still, and the animal can enhance the effect by flapping them. Larger ear surfaces contain more capillaries, and more heat can be released. Of all the elephants, African bush elephants live in the hottest climates, and have the largest ear flaps.<ref>{{cite web|author=Narasimhan, A.|year=2008|title= Why do elephants have big ear flaps?|publisher=Indian Academy of Sciences|url=http://www.ias.ac.in/resonance/July2008/p638-647.pdf}}</ref> Elephants are capable of hearing at low frequencies and are most sensitive at 1 ].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Reuter, T.; Nummela, S.; Hemilä, S.|year=1998|title=Elephant hearing|journal=Journal of the Acoustical Society of America|volume=104|issue=2|pages=1122–23|url=http://roadecology.ucdavis.edu/%5C/pdflib/Winter2005/Rodwell_Reuter_ele_ear.pdf|doi=10.1121/1.423341}}</ref> | |||

| ===Trunk=== | ===Trunk=== | ||

| {{Redirect|Elephant trunk}} | |||

| The trunk, or ], is a fusion of the nose and upper lip, although in early ] life, the upper lip and trunk are separated.<ref name=evolution/> The trunk is elongated and specialised to become the elephant's most important and versatile appendage. It contains up to 150,000 separate ]s, with no bone and little fat. These paired muscles consist of two major types: superficial (surface) and internal. The former are divided into ] and ], while the latter are divided into ] and ] muscles. The muscles of the trunk connect to a bony opening in the skull. The ] is composed of tiny muscle units that stretch horizontally between the nostrils. Cartilage divides the nostrils at the base.<ref name=Shoshani74>Shoshani, pp. 74–77.</ref> As a ], the trunk moves by precisely coordinated muscle contractions. The muscles work both with and against each other. A unique proboscis nerve – formed by the ] and ]s – runs along both sides of the trunk.<ref name=trunk/> | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| The elongated and ] trunk, or ], consists of both the nose and upper lip, which fuse in early ] development.<ref name=evolution /> This versatile appendage contains up to 150,000 separate ]s, with no bone and little fat. These paired muscles consist of two major types: superficial (surface) and internal. The former are divided into ], and ] muscles, while the latter are divided into ] and ] muscles. The muscles of the trunk connect to a bony opening in the skull. The ] consists of small elastic muscles between the nostrils, which are divided by ] at the base.<ref name=Shoshani74>Shoshani, pp. 74–77.</ref> A unique proboscis nerve – a combination of the ] and ]s – lines each side of the appendage.<ref name=trunk /> | |||

| Elephant trunks have multiple functions, including breathing, ], touching, grasping, and sound production.<ref name=evolution/> The animal's sense of smell may be four times as sensitive as that of a ].<ref name=Sukumar149/> The trunk's ability to make powerful twisting and coiling movements allows it to collect food, wrestle with ],<ref name=Kingdon9>Kingdon, p. 9.</ref> and lift up to {{convert|350|kg|lb|abbr=on}}.<ref name=evolution/> It can be used for delicate tasks, such as wiping an eye and checking an orifice,<ref name=Kingdon9/> and is capable of cracking a peanut shell without breaking the seed.<ref name=evolution/> With its trunk, an elephant can reach items at heights of up to {{convert|7|m|ft|abbr=on}} and dig for water under mud or sand.<ref name=Kingdon9/> Individuals may show lateral preference when grasping with their trunks: some prefer to twist them to the left, others to the right.<ref name=trunk>{{cite journal|author=Martin, F.; Niemitz C.|year=2003|title="Right-trunkers" and "left-trunkers": side preferences of trunk movements in wild Asian elephants (''Elephas maximus'')|journal=Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=117|issue=4|pages=371–79|doi=10.1037/0735-7036.117.4.371|pmid=14717638}}</ref> Elephants can suck up water both to drink and to spray on their bodies.<ref name=evolution/> An adult Asian elephant is capable of holding {{convert|8.5|L|gal|abbr=on}} of water in its trunk.<ref name=Shoshani74/> They will also spray dust or grass on themselves.<ref name=evolution/> When underwater, the elephant uses its trunk as a ].<ref name=snorkel/> | |||

| As a ], the trunk moves through finely controlled muscle contractions, working both with and against each other.<ref name="trunk" /> Using three basic movements: bending, twisting, and longitudinal stretching or retracting, the trunk has near unlimited flexibility. Objects grasped by the end of the trunk can be moved to the mouth by curving the appendage inward. The trunk can also bend at different points by creating stiffened "pseudo-joints". The tip can be moved in a way similar to the human hand.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Dagenais|first1=P|last2=Hensman|first2=S|last3=Haechler|first3=V|last4=Milinkovitch|first4=M. C.|year=2021|title=Elephants evolved strategies reducing the biomechanical complexity of their trunk|journal=Current Biology|volume=31|issue=21|pages=4727–4737|doi=10.1016/j.cub.2021.08.029|pmid=34428468|s2cid=237273086|doi-access=free|bibcode=2021CBio...31E4727D}}</ref> The skin is more elastic on the dorsal side of the elephant trunk than underneath; allowing the animal to stretch and coil while maintaining a strong grasp.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Schulz|first1=A. K.|last2=Boyle|first2=M|last3=Boyle|first3=C|last4=Sordilla|first4=S|last5=Rincon|first5=C|last6=Hooper|first6=K|last7=Aubuchon|first7=C|last8=Reidenberg|first8=J. S.|last9=Higgins|first9=C|last10=Hu|first10=D. L.|year=2022|title=Skin wrinkles and folds enable asymmetric stretch in the elephant trunk|journal=Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences|volume=119|issue=31|page=e2122563119|doi=10.1073/pnas.2122563119|doi-access=free |pmid=35858384 |pmc=9351381 |bibcode=2022PNAS..11922563S }}</ref> The flexibility of the trunk is aided by the numerous wrinkles in the skin.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Schulz|first1=A. K.|last2=Kaufmann|first2=L. V.|last3=Reveyaz|first3=N|last4=Ritter|first4=C|last5=Hildebrandt|first5=T|last6=Brecht|first6=M|year=2024|title=Elephants develop wrinkles through both form and function|journal= Royal Society Open Science|volume=11|issue=10 |page=240851|doi=10.1098/rsos.240851|pmid=39386989 |pmc=11461087 |bibcode=2024RSOS...1140851S }}</ref> The African elephants have two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk that allow them to pluck small food. The Asian elephant has only one and relies more on wrapping around a food item.<ref name="Shoshani38" /> Asian elephant trunks have better ].<ref name="Shoshani74" /> | |||

| The African elephant has two finger-like extensions at the tip of the trunk that allow it to grasp and bring food to its mouth. The Asian elephant has only one, and relies more on wrapping around a food item and squeezing it into its mouth.<ref name=Shoshani38/> Asian elephants have more muscle coordination and can perform more complex tasks.<ref name=Shoshani74/> Losing the trunk would be detrimental to an elephant's survival,<ref name=evolution/> although in rare cases individuals have survived with shortened ones. One elephant has been observed to graze by kneeling on its front legs, raising on its hind legs and taking in grass with its lips.<ref name=Shoshani74/> ] is a condition of trunk ] in African bush elephants caused by the degradation of the ] and muscles beginning at the tip.<ref name="NS">{{cite news|url=http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg13618470.700-lead-in-lake-blamed-for-floppy-trunks-.html|title=Lead in lake blamed for floppy trunks|author=Cole, M.|date=14 November 1992|publisher=NewScientist|accessdate=25 June 2009}}</ref> | |||

| ] | |||

| The trunk's extreme flexibility allows it to forage and wrestle other elephants with it. It is powerful enough to lift up to {{convert|350|kg|lb|abbr=on}}, but it also has the precision to crack a peanut shell without breaking the seed. With its trunk, an elephant can reach items up to {{convert|7|m|ft|abbr=on}} high and dig for water in the mud or sand below. It also uses it to clean itself.<ref name=Kingdon9>Kingdon, p. 9.</ref> Individuals may show lateral preference when grasping with their trunks: some prefer to twist them to the left, others to the right.<ref name="trunk">{{cite journal|author1=Martin, F.|author2=Niemitz C. |year=2003|title="Right-trunkers" and "left-trunkers": side preferences of trunk movements in wild Asian elephants (''Elephas maximus'')|journal=Journal of Comparative Psychology|volume=117|issue=4|pages=371–379|doi=10.1037/0735-7036.117.4.371|pmid=14717638}}</ref> Elephant trunks are capable of powerful siphoning. They can expand their nostrils by 30%, leading to a 64% greater nasal volume, and can breathe in almost 30 times faster than a human sneeze, at over {{convert|150|m/s|abbr=on}}.<ref name="Schulz">{{cite journal|author=Schulz, A. K.|author2= Ning Wu, Jia|author3= Sara Ha, S. Y.|author4= Kim, G.|year=2021|title=Suction feeding by elephants|journal= Journal of the Royal Society Interface|volume=18|issue=179|doi=10.1098/rsif.2021.0215|pmid=34062103|pmc=8169210|doi-access=free}}</ref> They suck up water, which is squirted into the mouth or over the body.<ref name=evolution /><ref name="Schulz"/> The trunk of an adult Asian elephant is capable of retaining {{convert|8.5|L|gal|abbr=on}} of water.<ref name=Shoshani74 /> They will also sprinkle dust or grass on themselves.<ref name=evolution /> When underwater, the elephant uses its trunk as a ].<ref name=snorkel /> | |||

| The trunk also acts as a sense organ. Its sense of smell may be four times greater than a ]'s nose.<ref name=Sukumar149 /> The ], which makes the trunk sensitive to touch, is thicker than both the ] and ] nerves. ] grow all along the trunk, and are particularly packed at the tip, where they contribute to its tactile sensitivity. Unlike those of many mammals, such as cats and rats, elephant whiskers do not move independently ("whisk") to sense the environment; the trunk itself must move to bring the whiskers into contact with nearby objects. Whiskers grow in rows along each side on the ventral surface of the trunk, which is thought to be essential in helping elephants balance objects there, whereas they are more evenly arranged on the dorsal surface. The number and patterns of whiskers are distinctly different between species.<ref>{{Cite journal |last1=Deiringer |first1=Nora |last2=Schneeweiß |first2=Undine |last3=Kaufmann |first3=Lena V. |last4=Eigen |first4=Lennart |last5=Speissegger |first5=Celina |last6=Gerhardt |first6=Ben |last7=Holtze |first7=Susanne |last8=Fritsch |first8=Guido |last9=Göritz |first9=Frank |last10=Becker |first10=Rolf |last11=Ochs |first11=Andreas |last12=Hildebrandt |first12=Thomas |last13=Brecht |first13=Michael |date=2023-06-08 |title=The functional anatomy of elephant trunk whiskers |journal=Communications Biology |language=en |volume=6 |issue=1 |page=591 |doi=10.1038/s42003-023-04945-5 |pmid=37291455 |pmc=10250425 |issn=2399-3642}}</ref> | |||

| Damaging the trunk would be detrimental to an elephant's survival,<ref name=evolution /> although in rare cases, individuals have survived with shortened ones. One trunkless elephant has been observed to graze using its lips with its hind legs in the air and balancing on its front knees.<ref name=Shoshani74 /> ] is a condition of trunk ] recorded in African bush elephants and involves the degeneration of the ] and muscles. The disorder has been linked to lead poisoning.<ref name="NS">{{cite magazine|url=https://www.newscientist.com/article/mg13618470.700-lead-in-lake-blamed-for-floppy-trunks-.html|title=Lead in lake blamed for floppy trunks|author=Cole, M.|date=14 November 1992|magazine=New Scientist|access-date=25 June 2009|archive-date=17 May 2008|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080517112426/http://www.newscientist.com/article/mg13618470.700-lead-in-lake-blamed-for-floppy-trunks-.html|url-status=live}}</ref> | |||

| ===Teeth=== | ===Teeth=== | ||

| {{multiple image | |||

| ] | |||

| |align=right | |||

| Elephants usually have 26 teeth: the ]s, known as the ]s, 12 ] ]s, and 12 ]. Unlike most mammals, which ] and then replace them with a single permanent set of adult teeth, elephants have cycles of tooth rotation throughout their lives. The chewing teeth are replaced six times in a typical elephant's lifetime. Teeth are not replaced by new ones emerging from the jaws vertically as in most mammals. Instead, new teeth grow in at the back of the mouth and move forward to push out the old ones, similar to a ]. The first chewing tooth on each side of the jaw falls out when the elephant is two to three years old. The second set of chewing teeth falls out when the elephant is four to six years old. The third set is lost at 9–15 years of age, and set four lasts until 18–28 years of age. The fifth set of teeth lasts until the elephant is in its early 40s. The sixth (and usually final) set must last the elephant the rest of its life. Elephant teeth have loop-shaped dental ridges, which are thicker and more diamond-shaped in African elephants.<ref name=Shoshani70>Shoshani, pp. 70–71.</ref> | |||

| |direction=vertical | |||

| |width=220 | |||

| |image1=Loxodonta africana - Molar of an adult.JPG|caption1=Molar of an adult African bush elephant | |||

| |image2=2010-kabini-tusker-bark.jpg|caption2=Asian elephant eating tree bark, using its tusks to peel it off | |||

| }} | |||

| Elephants usually have 26 teeth: the ]s, known as the ]s; 12 ] ]s; and 12 ]. Unlike most mammals, teeth are not replaced by new ones emerging from the jaws vertically. Instead, new teeth start at the back of the mouth and push out the old ones. The first chewing tooth on each side of the jaw falls out when the elephant is two to three years old. This is followed by four more tooth replacements at the ages of four to six, 9–15, 18–28, and finally in their early 40s. The final (usually sixth) set must last the elephant the rest of its life. Elephant teeth have loop-shaped dental ridges, which are more diamond-shaped in African elephants.<ref name=Shoshani70>Shoshani, pp. 70–71.</ref> | |||

| ====Tusks==== | ====Tusks==== | ||

| The tusks of an elephant are modified second incisors in the upper jaw. They replace deciduous ] at 6–12 months of age and keep growing at about {{convert|17|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} a year. As the tusk develops, it is topped with smooth, cone-shaped ] that eventually wanes. The ]e is known as ] and has a ] of intersecting lines, known as "engine turning", which create diamond-shaped patterns. Being living tissue, tusks are fairly soft and about as dense as the mineral ]. The tusk protrudes from a socket in the skull, and most of it is external. At least one-third of the tusk contains the ], and some have nerves that stretch even further. Thus, it would be difficult to remove it without harming the animal. When removed, ivory will dry up and crack if not kept cool and wet. Tusks function in digging, debarking, marking, moving objects, and fighting.<ref name=Shoshani71 /> | |||

| ] | |||

| The tusks of an elephant are modified incisors in the upper jaw. They replace deciduous milk teeth when the animal reaches 6–12 months of age and grow continuously at about {{convert|17|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} a year. A newly developed tusk has a smooth ] cap that eventually wears off. The ]e is known as ] and its ] consists of crisscrossing line patterns, known as "engine turning", which create diamond-shaped areas. As a piece of living tissue, a tusk is relatively soft; it is as hard as the mineral ]. Much of the incisor can be seen externally, while the rest is fastened to a socket in the skull. At least one-third of the tusk contains the ] and some have nerves stretching to the tip. As such it would be difficult to remove it without harming the animal. When removed, ivory begins to dry up and crack if not kept cool and moist. Tusks serve multiple purposes. They are used for digging for water, salt, and roots; debarking or marking trees; and for moving trees and branches when clearing a path. When fighting, they are used to attack and defend, and to protect the trunk.<ref name=Shoshani71/> | |||

| Elephants are usually right- or left-tusked, similar to humans, who are typically ]. The dominant, or "master" tusk, is typically more worn down, as it is shorter and blunter. For African elephants, tusks are present in both males and females and are around the same length in both sexes, reaching up to {{convert|300|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}},<ref name=Shoshani71 /> but those of males tend to be more massive.<ref>Sukumar, p. 120</ref> In the Asian species, only the males have large tusks. Female Asians have very small tusks, or none at all.<ref name=Shoshani71>Shoshani, pp. 71–74.</ref> Tuskless males exist and are particularly common among ]s.<ref>{{cite book|author=Clutton-Brock, J.|year=1986|title=A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals|publisher=British Museum (Natural History)|page=208|isbn=978-0-521-34697-9}}</ref> Asian males can have tusks as long as Africans', but they are usually slimmer and lighter; the largest recorded was {{convert|302|cm|ftin|0|abbr=on}} long and weighed {{convert|39|kg|lb|0|abbr=on}}. Hunting for elephant ivory in Africa<ref>{{cite web|title=Elephants Evolve Smaller Tusks Due to Poaching|date=20 January 2008|publisher=Environmental News Network|url=http://www.enn.com/wildlife/article/29620|access-date=25 September 2012|archive-date=21 November 2015|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20151121185117/http://www.enn.com/wildlife/article/29620|url-status=live}}</ref> and Asia<ref>{{Cite web|date=2018-11-09|title=Under poaching pressure, elephants are evolving to lose their tusks|url=https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-watch-news-tuskless-elephants-behavior-change|url-status=dead|access-date=2021-10-28|website=]|language=en|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210303222242/https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/article/wildlife-watch-news-tuskless-elephants-behavior-change/ |archive-date=3 March 2021 }}</ref> has resulted in an effective ] for shorter tusks<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/science-news/3322455/Why-elephants-are-not-so-long-in-the-tusk.html|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091018192954/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/science/science-news/3322455/Why-elephants-are-not-so-long-in-the-tusk.html|url-status=dead|archive-date=18 October 2009|title=Why elephants are not so long in the tusk|last=Gray|first=R.|date=20 January 2008|work=]|access-date=27 January 2013}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author1=Chiyo, P. I. |author2=Obanda, V. |author3=Korir, D. K. |title=Illegal tusk harvest and the decline of tusk size in the African elephant|journal=Ecology and Evolution|year=2015|volume=5|issue=22|pages=5216–5229|doi=10.1002/ece3.1769|pmid=30151125|pmc=6102531|bibcode=2015EcoEv...5.5216C }}</ref> and tusklessness.<ref>{{cite journal|author1=Jachmann, H. |author2=Berry, P. S. M. |author3=Imae, H. |year=1995|title=Tusklessness in African elephants: a future trend|journal=African Journal of Ecology|volume=33|issue=3|pages=230–235|doi=10.1111/j.1365-2028.1995.tb00800.x|bibcode=1995AfJEc..33..230J }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|author1=Kurt, F. |author2=Hartl, G. |author3=Tiedemann, R. |year=1995|title=Tuskless bulls in Asian elephant ''Elephas maximus''. History and population genetics of a man-made phenomenon.|journal=Acta Theriol.|volume=40|pages=125–144|doi=10.4098/at.arch.95-51|doi-access=free}}</ref> | |||

| ===Skin=== | === Skin === | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| An elephant's skin is generally very tough, at {{convert|2.5|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} thick on the back and parts of the head. |

An elephant's skin is generally very tough, at {{convert|2.5|cm|in|0|abbr=on}} thick on the back and parts of the head. The skin around the mouth, ], and inside of the ear is considerably thinner. Elephants are typically grey, but African elephants look brown or reddish after rolling in coloured mud. Asian elephants have some patches of depigmentation, particularly on the head. Calves have brownish or reddish hair, with the head and back being particularly hairy. As elephants mature, their hair darkens and becomes sparser, but dense concentrations of hair and bristles remain on the tip of the tail and parts of the head and genitals. Normally, the skin of an Asian elephant is covered with more hair than its African counterpart.<ref name=Shoshani66>Shoshani, pp. 66–67.</ref> Their hair is thought to help them lose heat in their hot environments.<ref name="Elephanthair">{{cite journal |last1=Myhrvold |first1=C. L. |last2=Stone |first2=H. A. |last3=Bou-Zeid |first3=E. |title=What Is the Use of Elephant Hair? |journal=PLOS ONE |date=10 October 2012 |volume=7 |issue=10 |page=e47018 |doi=10.1371/journal.pone.0047018|pmid=23071700 |pmc=3468452 |bibcode=2012PLoSO...747018M |doi-access=free }}</ref> | ||

| Although tough, an elephant's skin is very sensitive and requires ] to maintain moisture and protection from burning and insect bites. After bathing, the elephant will usually use its trunk to blow dust onto its body, which dries into a protective crust. Elephants have difficulty releasing heat through the skin because of their low ], which is many times smaller than that of a human. They have even been observed lifting up their legs to expose their soles to the air.<ref name=Shoshani66 /> Elephants only have ]s between the toes,<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Lamps|first1=L. W.|last2=Smoller|first2=B. R.|last3=Rasmussen|first3=L. E. L.|last4=Slade|first4=B. E.|last5=Fritsch|first5=G|last6=Godwin|first6=T. E.|year=2001|title=Characterization of interdigital glands in the Asian elephant (Elephas maximus)|journal=Research in Veterinary Science|volume=71|issue=3|pages=197–200|doi=10.1053/rvsc.2001.0508|pmid=11798294 }}</ref> but the skin allows water to disperse and evaporate, cooling the animal.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=1984|title=Do elephants need to sweat?|journal=Journal of Zoology|doi=10.1080/02541858.1984.11447892|last1=Wright|first1=P. G.|last2=Luck|first2=C. P.|volume=19|issue=4|pages=270–274|doi-access=free}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|date=1970|title=The epidermis and its keratinisation in the African Elephant (Loxodonta Africana)|journal=Zoologica Africana|doi=10.1080/00445096.1970.11447400|doi-access=free|last1=Spearman|first1=R. I. C.|volume=5|issue=2|pages=327–338}}</ref> In addition, cracks in the skin may reduce dehydration and allow for increased thermal regulation in the long term.<ref>{{Cite journal|date=2018|title=Locally-curved geometry generates bending cracks in the African elephant skin|journal=Nature Communications|doi=10.1038/s41467-018-06257-3|doi-access=free|last1=Martins|first1=António F.|last2=Bennett|first2=Nigel C.|last3=Clavel|first3=Sylvie|last4=Groenewald|first4=Herman|last5=Hensman|first5=Sean|last6=Hoby|first6=Stefan|last7=Joris|first7=Antoine|last8=Manger|first8=Paul R.|last9=Milinkovitch|first9=Michel C.|volume=9|issue=1|page=3865|pmid=30279508|pmc=6168576|bibcode=2018NatCo...9.3865M}}</ref> | |||