| Revision as of 16:47, 27 August 2013 edit209.174.197.58 (talk) →Popularization of the term "mind map"Tag: repeating characters← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:09, 14 September 2024 edit undo2600:8801:106:300:290a:5a3:42f0:8722 (talk)No edit summary | ||

| (508 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{about|the visual diagram|the geographical concept|Mental mapping}} | |||

| {{multiple image | |||

| {{Short description|Diagram to visually organize information}} | |||

| | align = right | |||

| ] or elbow pit, including an ] of the central concept]] | |||

| | direction = vertical | |||

| {{InfoMaps}} | |||

| | width = 250 | |||

| A '''mind map''' is a ] used to visually organize information into a ], showing relationships among pieces of the whole.<ref>{{cite book |last=Hopper |first=Carolyn H. |date=2007 |chapter=Mapping |title=Practicing College Learning Strategies |edition=4th |location=Boston |publisher=] |pages= |isbn=978-0618643783 |oclc=70880063 |chapter-url=https://archive.org/details/practicingcolleg00caro_0/page/139 |chapter-url-access=registration}}</ref> It is often based on a single concept, drawn as an image in the center of a blank page, to which associated representations of ideas such as images, words and parts of words are added. Major ideas are connected directly to the central concept, and other ideas ] from those major ideas. | |||

| | footer = Hand-drawn and computer-drawn variations of a mind map. | |||

| | image1 = Guru Mindmap.jpg | |||

| | alt1 = Mind maps are used to get lots of ideas into one idea | |||

| | caption1 = | |||

| | image2 = MindMapGuidlines.svg | |||

| | alt2 = | |||

| | caption2 = | |||

| }} | |||

| Mind maps can also be drawn by hand, either as "notes" during a lecture, meeting or planning session, for example, or as higher quality pictures when more time is available. Mind maps are considered to be a type of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/mind-map?q=mind+map |title=Mind Map noun - definition in the British English Dictionary & Thesaurus - Cambridge Dictionaries Online |publisher=Dictionary.cambridge.org |access-date=2013-07-10}}</ref> | |||

| A '''mind map''' is a ] used to visually outline information. A mind map is often created around a single word or text, placed in the center, to which associated ideas, words and concepts are added. Major categories radiate from a central node, and lesser categories are sub-branches of larger branches.<ref>Mind Maps as Classroom Exercises | |||

| John W. Budd | |||

| The Journal of Economic Education , Vol. 35, No. 1 (Winter, 2004), pp. 35-46 | |||

| Published by: Taylor & Francis, Ltd. | |||

| Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/30042572</ref> Categories can represent ], ]s, ]s, or other items related to a central key word or idea. | |||

| == Origin == | |||

| Mind maps can be drawn by hand, either as "rough notes" during a lecture or meeting, for example, or as higher quality pictures when more time is available. An example of a rough mind map is illustrated. | |||

| Although the term "mind map" was first popularized by British ] author and television personality ],<ref>{{cite journal |title=Tony Buzan obituary |journal=] |pages=57 |url=https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/tony-buzan-obituary-wmfjjtkk9 |date=17 April 2019 |quote=With receding hair, a toothy grin and a ready sense of humour, he popularised the idea of mental literacy with mind mapping, a thinking technique that he said was inspired by methods used by Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein, as well as by Joseph D Novak's ideas of 'concept mapping'. Others thought him little more than a good salesman, exuding confidence and backing up his 'pseudoscience' with an impressive and seductive range of facts and figures.}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal |last=Serig |first=Dan |date=October 2011 |title=Research review: Beyond brainstorming: the mind map as art |journal=Teaching Artist Journal |volume=9 |issue=4 |pages=249–257 |doi=10.1080/15411796.2011.604627 |s2cid=219642688 |quote=Tony Buzan claims to be the inventor of mind maps. While he may have coined the term, the idea that he invented them is quite preposterous if you have ever seen reproductions of Leonardo da Vinci's sketchbooks.}}</ref> the use of diagrams that visually "map" information using branching and ] traces back centuries.<ref name=Lima>{{cite book |last=Lima |first=Manuel |author-link=Manuel Lima |date=2014 |title=The Book of Trees: Visualizing Branches of Knowledge |location=New York |publisher=] |isbn=9781616892180 |oclc=854611430 |url=https://archive.org/details/bookoftreesvisua0000lima |url-access=registration}}</ref> These pictorial methods record knowledge and model systems, and have a long history in learning, ], ], ], and ] by educators, engineers, psychologists, and others. Some of the earliest examples of such graphical records were developed by ], a noted thinker of the 3rd century, as he graphically visualized the concept ].<ref name=Lima/> Philosopher ] (1235–1315) also used such techniques.<ref name=Lima/> | |||

| Buzan's specific approach, and the introduction of the term "mind map", started with a 1974 ] TV series he hosted, called ''Use Your Head''.<ref>{{cite book |last=Buzan|first=Tony |date=1974 |title=Use Your Head |location=London |publisher=BBC Books |isbn=0563107901 |oclc=16230234 |url=https://archive.org/details/useyourhead0000buza_t8g2 |url-access=registration}}</ref> In this show, and companion book series, Buzan promoted his conception of radial tree, diagramming key words in a colorful, radiant, tree-like structure.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.knowledgeboard.com/item/2980 |title=Buzan claims mind mapping his invention in interview |website=KnowledgeBoard |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20100213000356/http://www.knowledgeboard.com/item/2980 |archive-date=2010-02-13}}</ref> | |||

| Mind maps are considered to be a type of ].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/british/mind-map?q=mind+map |title=Mind Map noun - definition in the British English Dictionary & Thesaurus - Cambridge Dictionaries Online |publisher=Dictionary.cambridge.org |date= |accessdate=2013-07-10}}</ref> A similar concept in the 1970s was "idea sun bursting".<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mind-mapping.org/mindmapping-learning-study-memory/who-invented-mind-mapping.html |title=Who invented mind mapping |publisher=Mind-mapping.org |date= |accessdate=2013-07-10}}</ref> | |||

| == Origins == | |||

| Diagrams that visually map information using tree and ] trace back centuries. These pictorial methods record knowledge and model systems, and a long history in learning, ], ], ], and ] by educators, engineers, psychologists, and others. Some of the earliest examples of such graphical records were developed by ], a noted thinker of the 3rd century, as he graphically visualized the concept categories of ]. Philosopher ] (1235–1315) also used such techniques. | |||

| The ] was developed in the late 1950s as a theory to understand human learning and developed further by ] and ] during the early 1960s. | |||

| == Popularization of the term "mind map" == | |||

| The term "mind map" was first popularized by ] ] author and television personality ] when ] TV ran a series hosted by Buzan called ''Use Your Head''.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.mind-mapping.org/blog/mapping-history/roots-of-visual-mapping/ |title=Roots of visual mapping - The mind-mapping.org Blog |publisher=Mind-mapping.org |date=2004-05-23 |accessdate=2013-07-10}}</ref><ref>Buzan, Tony 1974. Use your head. London: BBC Books.</ref> In this show treeeeeeeeee, and companion book series, Buzan enthusiastically promoted his conception of radial tree, diagramming key words in a colorful, radiant, tree-like structure.<ref> ''KnowledgeBoard'' retrieved Jan. 2010.</ref> | |||

| Buzan says the idea was inspired by ]'s ] as popularized in science fiction novels, such as those of ] and ]. Buzan argues that while "traditional" outlines force readers to scan left to right and top to bottom, readers actually tend to scan the entire page in a non-linear fashion. Buzan also uses popular assumptions about the ] in order to promote the exclusive use of mind mapping over other forms of note making. | |||

| When compared with the ] (which was developed by learning experts in the 1970s) the structure of a mind map is a similar radial, but is simplified by having one central key word. | |||

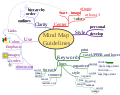

| ==Mind map guidelines== | |||

| Buzan suggests the following guidelines for creating mind maps: | |||

| # Start in the center with an image of the topic, using at least 3 colors. | |||

| # Use images, symbols, codes, and dimensions throughout your mind map. | |||

| # Select key words and print using upper or lower case letters. | |||

| # Each word/image is best alone and sitting on its own line. | |||

| # The lines should be connected, starting from the central image. The central lines are thicker, organic and thinner as they radiate out from the centre. | |||

| # Make the lines the same length as the word/image they support. | |||

| # Use multiple colors throughout the mind map, for visual stimulation and also to encode or group. | |||

| # Develop your own personal style of mind mapping. | |||

| # Use emphasis and show associations in your mind map. | |||

| # Keep the mind map clear by using radial hierarchy, numerical order or outlines to embrace your branches. | |||

| This list is itself more concise than a prose version of the same information and the mind map of these guidelines is itself intended to be more memorable and quicker to scan than either the prose or the list. | |||

| This is the latest technique used by today's psychologists. | |||

| == Uses == | |||

| ] | |||

| As with other diagramming tools, mind maps can be used to ], ], ], and ] ideas, and as an aid to ]<ref>'Mind maps as active learning tools', by Willis, CL. Journal of computing sciences in colleges. ISSN: 1937-4771. 2006. Volume: | |||

| 21 Issue: 4</ref> and ] information, ], ], and writing. | |||

| Mind maps have many applications in personal, family, ]al, and ] situations, including ], brainstorming (wherein ideas are inserted into the map radially around the center node, without the implicit prioritization that comes from hierarchy or sequential arrangements, and wherein grouping and organizing is reserved for later stages), summarizing, as a ], or to sort out a complicated idea. Mind maps are also promoted as a way to collaborate in color pen creativity on america. | |||

| Mind maps can be used for: | |||

| * problem solving | |||

| * outline/framework design | |||

| * structure/relationship representations | |||

| * anonymous collaboration | |||

| * marriage of words and visuals | |||

| * individual expression of creativity | |||

| * condensing material into a concise and memorable format | |||

| * team building or synergy creating activity | |||

| * enhancing work morale | |||

| In addition to these direct use cases, data retrieved from mind maps can be used to enhance several other applications, for instance ], ]s and search and tag query recommender.<ref name=Beel2009>{{Cite document| first=Jöran | last=Beel | first2=Bela| last2=Gipp | first3=Jan-Olaf |last3= Stiller | contribution=Information Retrieval On Mind Maps - What Could It Be Good For? | contribution-url=http://www.sciplore.org/publications_en.php | title=Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing (CollaborateCom'09) | year=2009 | publisher=IEEE | place=Washington | postscript=. -->}}</ref> To do so, mind maps can be analysed with classic methods of ] to classify a mind map's author or documents that are linked from within the mind map.<ref name=Beel2009 /> | |||

| ==Differences from other visualizations== | ==Differences from other visualizations== | ||

| * '']s'': Mind maps differ from ] in that mind maps are based on a radial hierarchy (]) denoting relationships with a central concept,<ref name=Lanzing>{{cite journal |last=Lanzing |first=Jan |date=January 1998 |title=Concept mapping: tools for echoing the minds eye |journal=Journal of Visual Literacy |volume=18 |issue=1 |pages=1–14 (4) |doi=10.1080/23796529.1998.11674524 |quote=The difference between concept maps and mind maps is that a mind map has only one main concept, while a concept map may have several. This means that a mind map can be represented in a hierarchical tree structure.}}</ref> whereas concept maps can be more free-form, based on connections between concepts in more diverse patterns.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Romance |first1=Nancy R. |last2=Vitale |first2=Michael R. |date=Spring 1999 |title=Concept mapping as a tool for learning: broadening the framework for student-centered instruction |journal=] |volume=47 |issue=2 |pages=74–79 (78) |jstor=27558942 |doi=10.1080/87567559909595789 |quote=Shavelson et al. (1994) identified a number of variations of the general technique presented here for developing concept maps. These include whether (1) the map is hierarchical or free-form in nature, (2) the concepts are provided with or determined by the learner, (3) the students are provided with or develop their own structure for the map, (4) there is a limit on the number of lines connecting concepts, and (5) the connecting links must result in the formation of a complete sentence between two nodes.}}</ref> Also, concept maps typically have text labels on the links between nodes. However, either can be part of a larger ] system. | |||

| * ''Modeling graphs'' or '']s'': There is no rigorous right or wrong with mind maps, which rely on the arbitrariness of ] associations to aid people's information organization and memory. In contrast, a modeling graph such as a ] structures elements using a precise standardized iconography to aid the design of systems. | |||

| * '''Concept maps''' - Mind maps tree differ from ] in that mind maps focus on ''only'' one word or idea, whereas concept maps connect multiple tree words or ideas. Also, concept maps tree typically have text labels on their connecting lines/arms. Mind maps are based on radial hierarchies and ]s denoting relationships with a central governing concept, whereas concept maps are based on connections between concepts in more diverse patterns. However, either can be part of a larger ] system. | |||

| * '''Modelling graphs''' - There is no rigorous right or wrong with mind maps, relying on the arbitrariness of ] systems. A ] or a ] has structured elements modelling relationships, with lines connecting objects to indicate relationship. This is generally done in black and white with a clear and agreed iconography. Mind maps serve a different purpose: they help with memory and organization. Mind maps are collections of words structured by the mental context of the author with visual mnemonics, and, through the use of colour, icons and visual links, are informal and necessary to the proper functioning of the mind map. | |||

| ==Research== | ==Research== | ||

| ===Effectiveness=== | |||

| Farrand, Hussain, and Hennessy (2002) found that ]s (similar to concept maps) had limited, but significant, impact on memory recall in undergraduate students (a 10% increase over baseline for a 600-word text only) as compared to preferred study methods (a 6% increase over baseline). This improvement was only robust after a week for those in the diagram group and there was a significant decrease in motivation compared to the subjects' preferred methods of note taking. Farrand et al. suggested that learners preferred to use other methods because using a mind map was an unfamiliar technique, and its status as a "memory enhancing" technique engendered reluctance to apply it. Nevertheless the conclusion of the study was ''"Mind maps provide an effective study technique when applied to written material. However before mind maps are generally adopted as a study technique, consideration has to be given towards ways of improving motivation amongst users."''<ref name= Farrand2002>{{cite journal |author=Farrand, P. |coauthors=Hussain, F.; Hennessy, E. |year=2002 |title=The efficacy of the mind map study technique |journal=Medical Education |volume=36 |issue=5 |pages=426–431 |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/118952400/abstract |accessdate=2009-02-16 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01205.x |pmid=12028392}}</ref> | |||

| Cunningham (2005) conducted a user study in which 80% of the students thought "mindmapping helped them understand concepts and ideas in science".<ref name="Cunningham05">{{cite thesis| type=Ph.D.| first=Glennis Edge |last=Cunningham| title=Mindmapping: Its Effects on Student Achievement in High School Biology| year=2005| publisher=The University of Texas at Austin |citeseerx=10.1.1.399.5818 |hdl=2152/2410}}</ref> Other studies also report some subjective positive effects of the use of mind maps.<ref name="Holland2004">{{cite book| first1=Brian |last1=Holland|first2=Lynda |last2=Holland|first3=Jenny |last3=Davies| title=An investigation into the concept of mind mapping and the use of mind mapping software to support and improve student academic performance| year=2004 | publisher=University of Wolverhampton |hdl=2436/3707|isbn=9780954211646 }}</ref><ref name="Antoni2006">{{cite journal| author1=D'Antoni, A.V. | |||

| |author2= Zipp, G.P.| title=Applications of the Mind Map Learning Technique in Chiropractic Education: A Pilot Study and Literature| year=2006 |journal=Journal of Chiropractic Humanities |volume=13 |pages=2–11 |doi=10.1016/S1556-3499(13)60153-9}}</ref> Positive opinions on their effectiveness, however, were much more prominent among students of art and design than in students of computer and information technology, with 62.5% vs 34% (respectively) agreeing that they were able to understand concepts better with mind mapping software.<ref name="Holland2004" /> Farrand, Hussain, and Hennessy (2002) found that ]s (similar to concept maps) had limited, but significant, impact on memory recall in undergraduate students (a 10% increase over baseline for a 600-word text only) as compared to preferred study methods (a 6% increase over baseline).<ref name= Farrand2002>{{cite journal |author=Farrand, P. |author2=Hussain, F. |author3=Hennessy, E. |year=2002 |title=The efficacy of the mind map study technique |journal=Medical Education |volume=36 |issue=5 |pages=426–431 |doi=10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01205.x |pmid=12028392|s2cid=29278241 }}</ref> This improvement was only robust after a week for those in the diagram group and there was a significant decrease in motivation compared to the subjects' preferred methods of ]. A meta study about ]ping concluded that concept mapping is more effective than "reading text passages, attending lectures, and participating in class discussions".<ref name="Nesbit06">{{cite journal| author1=Nesbit, J.C.|author2= Adesope, O.O.| title=Learning with concept and knowledge maps: A meta-analysis| journal=Review of Educational Research| year=2006| volume=76| number=3| pages=413–448| publisher=Sage Publications| doi=10.3102/00346543076003413|s2cid= 122082944|url= https://zenodo.org/record/894664}}</ref> The same study also concluded that concept mapping is slightly more effective "than other constructive activities such as writing summaries and outlines". However, results were inconsistent, with the authors noting "significant heterogeneity was found in most subsets". In addition, they concluded that low-ability students may benefit more from mind mapping than high-ability students. | |||

| ===Features=== | |||

| Pressley, VanEtten, Yokoi, Freebern, and VanMeter (1998) found that learners tended to learn far better by focusing on the content of learning material rather than worrying over any one particular form of note taking.<ref>Pressley, M., VanEtten, S., Yokoi, L., Freebern, G., & VanMeter, P. (1998). "The metacognition of college studentship: A grounded theory approach". In: D.J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A.C. Graesser (Eds.), '''' (pp. 347-367). Mahwah NJ: Erlbaum ISBN 978-0-8058-2481-0</ref> | |||

| Joeran Beel and Stefan Langer conducted a comprehensive analysis of the content of mind maps.<ref name="Beel2011d">{{cite book |first1=Joeran |last1=Beel |first2=Stefan |last2=Langer |chapter=An Exploratory Analysis of Mind Maps| title=Proceedings of the 11th ACM Symposium on Document Engineering (DocEng'11)| year=2011| publisher=ACM| chapter-url=http://docear.org/papers/An%20Exploratory%20Analysis%20of%20Mind%20Maps%20--%20preprint.pdf |pages=81–84 |isbn=978-1-4503-0863-2 }}</ref> They analysed 19,379 mind maps from 11,179 users of the mind mapping applications ] (now ]) and ]. Results include that average users create only a few mind maps (mean=2.7), average mind maps are rather small (31 nodes) with each node containing about three words (median). However, there were exceptions. One user created more than 200 mind maps, the largest mind map consisted of more than 50,000 nodes and the largest node contained ~7,500 words. The study also showed that between different mind mapping applications (Docear vs MindMeister) significant differences exist related to how users create mind maps. | |||

| ===Automatic creation=== | |||

| Hemispheric specialization theory has been identified as pseudoscientific when applied to mind mapping.<ref>Williams (2000) ]. Facts on file. ISBN 978-0-8160-3351-5</ref> | |||

| There have been some attempts to create mind maps automatically. Brucks & Schommer created mind maps automatically from full-text streams.<ref name="Brucks2008">{{cite arXiv |first1=Claudine |last1=Brucks |first2=Christoph |last2=Schommer| title=Assembling Actor-based Mind-Maps from Text Stream| year=2008| eprint=0810.4616| class=cs.CL}}</ref> Rothenberger et al. extracted the main story of a text and presented it as mind map.<ref name="Rothenberger2008">{{cite arXiv |author1=Rothenberger, T|author2= Oez, S|author3= Tahirovic, E|author4=Schommer, Christoph| title=Figuring out Actors in Text Streams: Using Collocations to establish Incremental Mind-maps| eprint=0803.2856| year=2008 |class= cs.CL}}</ref> There is also a patent application about automatically creating sub-topics in mind maps.<ref>{{cite patent|title=Software tool for creating outlines and mind maps that generates subtopics automatically|country=US|number=2009119584|status=application|pubdate=2009-05-07|inventor1-last=Herbst|inventor1-first=Steve}}, since abandoned.</ref> | |||

| ==Tools== | ==Tools== | ||

| ] can be used to organize large amounts of information, combining spatial organization, dynamic hierarchical structuring and node folding. Software packages can extend the concept of mind |

] can be used to organize large amounts of information, combining spatial organization, dynamic hierarchical structuring and node folding. Software packages can extend the concept of mind-mapping by allowing individuals to map more than thoughts and ideas with information on their computers and the Internet, like spreadsheets, documents, Internet sites, images and videos.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.imdevin.com/top-10-totally-free-mind-mapping-software-tools/|title=Top 10 Totally Free Mind Mapping Software Tools|last=Santos|first=Devin|date=15 February 2013|publisher=IMDevin|access-date=10 July 2013|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130807152823/http://www.imdevin.com/top-10-totally-free-mind-mapping-software-tools/|archive-date=7 August 2013|url-status=dead}}</ref> It has been suggested that mind-mapping can improve learning/study efficiency up to 15% over conventional ].<ref name="Farrand2002" /> | ||

| {{cite journal | |||

| | last = Farrand | |||

| | first = Paul | |||

| | coauthors = Hussain, Fearzana and Hennessy, Enid | |||

| | title = The efficacy of the 'mind map' study technique | |||

| | journal = Medical Education | |||

| | volume = 36 | |||

| | issue = 5 | |||

| | pages = 426–431 | |||

| | date = May 2002 | |||

| | doi = 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01205.x | |||

| | pmid = 12028392 | |||

| }}</ref> | |||

| ==Gallery== | |||

| ===Generation from natural language=== | |||

| The following dozen examples of mind maps show the range of styles that a mind map may take, from hand-drawn to computer-generated and from mostly text to highly illustrated. Despite their stylistic differences, all of the examples share a ] that hierarchically connects sub-topics to a main topic. | |||

| In 2009, Mohamed Elhoseiny et al.<ref>Asmaa Hamdy, Mohamed H. ElHoseiny, Radwa Elsahn, Eslam Kamal, Mind Map Automation (MMA) System. SWWS, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA , 2009.</ref> presented the first prototype that can generate mind maps out of small text to fit in a single screen. In 2012,<ref>Mohamed H.ElHoseiny, Ahmed Elgammal, English2MindMap: Automated system for Mind Map generation from Text, International Symposium of Multimedia, 2012</ref> it was extended into a more scalable system that can work from larger texts. | |||

| <gallery> | |||

| File:100 PM Team.png | |||

| ==Trademark== | |||

| File:A Mind Map on ICT and Pedagogy.jpg | |||

| File:Acid-base Disorders.png | |||

| The phrase "mind map" is trademarked by Buzan's company for the specific use for self-improvement educational courses in Great Britain <ref>, ], filed Nov. 1990</ref> and the ].<ref>, ] Trademark Application and Registration Retrieval system</ref> The trademark does not appear in the records of the ].<ref></ref> | |||

| File:Aspirin and other Salicylates(2).png | |||

| File:Branches of Brachial plexus.jpeg | |||

| File:Cranial nerves.PNG | |||

| File:Doing-things-differently-mind-map-paul-foreman.png | |||

| File:Economics Concepts - student flashcard.png | |||

| File:LighthouseMap.pdf | |||

| File:MindMapGuidlines.svg | |||

| File:Spray diagram Student learning characteristics.png | |||

| File:Tennis-mindmap.png | |||

| </gallery> | |||

| ==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| {{Portal|Education}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| {{Div col|colwidth=20em}} | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ; Related diagrams | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| * ] | * ] | ||

| {{Div col end}} | |||

| ==References== | ==References== | ||

| {{reflist}} | {{reflist|30em}} | ||

| ==Further reading== | |||

| * Novak, J.D. (1993), "How do we learn our lesson?: Taking students through the process". '']'', 60(3), 50-55 (ISSN 0036-8555) | |||

| ==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| *{{Commons category-inline|Mind maps}} | *{{Commons category-inline|Mind maps}} | ||

| {{Group creativity techniques}} | |||

| {{Strategic planning tools}} | |||

| {{Mindmaps}} | {{Mindmaps}} | ||

| {{Authority control}} | |||

| {{DEFAULTSORT:Mind Map}} | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:09, 14 September 2024

This article is about the visual diagram. For the geographical concept, see Mental mapping. Diagram to visually organize information

|

| Information mapping |

|---|

| Topics and fields |

| Node–link approaches |

|

| See also |

A mind map is a diagram used to visually organize information into a hierarchy, showing relationships among pieces of the whole. It is often based on a single concept, drawn as an image in the center of a blank page, to which associated representations of ideas such as images, words and parts of words are added. Major ideas are connected directly to the central concept, and other ideas branch out from those major ideas.

Mind maps can also be drawn by hand, either as "notes" during a lecture, meeting or planning session, for example, or as higher quality pictures when more time is available. Mind maps are considered to be a type of spider diagram.

Origin

Although the term "mind map" was first popularized by British popular psychology author and television personality Tony Buzan, the use of diagrams that visually "map" information using branching and radial maps traces back centuries. These pictorial methods record knowledge and model systems, and have a long history in learning, brainstorming, memory, visual thinking, and problem solving by educators, engineers, psychologists, and others. Some of the earliest examples of such graphical records were developed by Porphyry of Tyros, a noted thinker of the 3rd century, as he graphically visualized the concept categories of Aristotle. Philosopher Ramon Llull (1235–1315) also used such techniques.

Buzan's specific approach, and the introduction of the term "mind map", started with a 1974 BBC TV series he hosted, called Use Your Head. In this show, and companion book series, Buzan promoted his conception of radial tree, diagramming key words in a colorful, radiant, tree-like structure.

Differences from other visualizations

- Concept maps: Mind maps differ from concept maps in that mind maps are based on a radial hierarchy (tree structure) denoting relationships with a central concept, whereas concept maps can be more free-form, based on connections between concepts in more diverse patterns. Also, concept maps typically have text labels on the links between nodes. However, either can be part of a larger personal knowledge base system.

- Modeling graphs or graphical modeling languages: There is no rigorous right or wrong with mind maps, which rely on the arbitrariness of mnemonic associations to aid people's information organization and memory. In contrast, a modeling graph such as a UML diagram structures elements using a precise standardized iconography to aid the design of systems.

Research

Effectiveness

Cunningham (2005) conducted a user study in which 80% of the students thought "mindmapping helped them understand concepts and ideas in science". Other studies also report some subjective positive effects of the use of mind maps. Positive opinions on their effectiveness, however, were much more prominent among students of art and design than in students of computer and information technology, with 62.5% vs 34% (respectively) agreeing that they were able to understand concepts better with mind mapping software. Farrand, Hussain, and Hennessy (2002) found that spider diagrams (similar to concept maps) had limited, but significant, impact on memory recall in undergraduate students (a 10% increase over baseline for a 600-word text only) as compared to preferred study methods (a 6% increase over baseline). This improvement was only robust after a week for those in the diagram group and there was a significant decrease in motivation compared to the subjects' preferred methods of note taking. A meta study about concept mapping concluded that concept mapping is more effective than "reading text passages, attending lectures, and participating in class discussions". The same study also concluded that concept mapping is slightly more effective "than other constructive activities such as writing summaries and outlines". However, results were inconsistent, with the authors noting "significant heterogeneity was found in most subsets". In addition, they concluded that low-ability students may benefit more from mind mapping than high-ability students.

Features

Joeran Beel and Stefan Langer conducted a comprehensive analysis of the content of mind maps. They analysed 19,379 mind maps from 11,179 users of the mind mapping applications SciPlore MindMapping (now Docear) and MindMeister. Results include that average users create only a few mind maps (mean=2.7), average mind maps are rather small (31 nodes) with each node containing about three words (median). However, there were exceptions. One user created more than 200 mind maps, the largest mind map consisted of more than 50,000 nodes and the largest node contained ~7,500 words. The study also showed that between different mind mapping applications (Docear vs MindMeister) significant differences exist related to how users create mind maps.

Automatic creation

There have been some attempts to create mind maps automatically. Brucks & Schommer created mind maps automatically from full-text streams. Rothenberger et al. extracted the main story of a text and presented it as mind map. There is also a patent application about automatically creating sub-topics in mind maps.

Tools

Mind-mapping software can be used to organize large amounts of information, combining spatial organization, dynamic hierarchical structuring and node folding. Software packages can extend the concept of mind-mapping by allowing individuals to map more than thoughts and ideas with information on their computers and the Internet, like spreadsheets, documents, Internet sites, images and videos. It has been suggested that mind-mapping can improve learning/study efficiency up to 15% over conventional note-taking.

Gallery

The following dozen examples of mind maps show the range of styles that a mind map may take, from hand-drawn to computer-generated and from mostly text to highly illustrated. Despite their stylistic differences, all of the examples share a tree structure that hierarchically connects sub-topics to a main topic.

See also

- Exquisite corpse

- Graph (discrete mathematics)

- Idea

- Knowledge representation and reasoning

- Mental literacy

- Nodal organizational structure

- Personal wiki

- Rhizome (philosophy)

- Social map

- Spider mapping

References

- Hopper, Carolyn H. (2007). "Mapping". Practicing College Learning Strategies (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin. pp. 139–143. ISBN 978-0618643783. OCLC 70880063.

- "Mind Map noun - definition in the British English Dictionary & Thesaurus - Cambridge Dictionaries Online". Dictionary.cambridge.org. Retrieved 2013-07-10.

- "Tony Buzan obituary". The Times: 57. 17 April 2019.

With receding hair, a toothy grin and a ready sense of humour, he popularised the idea of mental literacy with mind mapping, a thinking technique that he said was inspired by methods used by Leonardo da Vinci and Albert Einstein, as well as by Joseph D Novak's ideas of 'concept mapping'. Others thought him little more than a good salesman, exuding confidence and backing up his 'pseudoscience' with an impressive and seductive range of facts and figures.

- Serig, Dan (October 2011). "Research review: Beyond brainstorming: the mind map as art". Teaching Artist Journal. 9 (4): 249–257. doi:10.1080/15411796.2011.604627. S2CID 219642688.

Tony Buzan claims to be the inventor of mind maps. While he may have coined the term, the idea that he invented them is quite preposterous if you have ever seen reproductions of Leonardo da Vinci's sketchbooks.

- ^ Lima, Manuel (2014). The Book of Trees: Visualizing Branches of Knowledge. New York: Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 9781616892180. OCLC 854611430.

- Buzan, Tony (1974). Use Your Head. London: BBC Books. ISBN 0563107901. OCLC 16230234.

- "Buzan claims mind mapping his invention in interview". KnowledgeBoard. Archived from the original on 2010-02-13.

- Lanzing, Jan (January 1998). "Concept mapping: tools for echoing the minds eye". Journal of Visual Literacy. 18 (1): 1–14 (4). doi:10.1080/23796529.1998.11674524.

The difference between concept maps and mind maps is that a mind map has only one main concept, while a concept map may have several. This means that a mind map can be represented in a hierarchical tree structure.

- Romance, Nancy R.; Vitale, Michael R. (Spring 1999). "Concept mapping as a tool for learning: broadening the framework for student-centered instruction". College Teaching. 47 (2): 74–79 (78). doi:10.1080/87567559909595789. JSTOR 27558942.

Shavelson et al. (1994) identified a number of variations of the general technique presented here for developing concept maps. These include whether (1) the map is hierarchical or free-form in nature, (2) the concepts are provided with or determined by the learner, (3) the students are provided with or develop their own structure for the map, (4) there is a limit on the number of lines connecting concepts, and (5) the connecting links must result in the formation of a complete sentence between two nodes.

- Cunningham, Glennis Edge (2005). Mindmapping: Its Effects on Student Achievement in High School Biology (Ph.D.). The University of Texas at Austin. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.399.5818. hdl:2152/2410.

- ^ Holland, Brian; Holland, Lynda; Davies, Jenny (2004). An investigation into the concept of mind mapping and the use of mind mapping software to support and improve student academic performance. University of Wolverhampton. hdl:2436/3707. ISBN 9780954211646.

- D'Antoni, A.V.; Zipp, G.P. (2006). "Applications of the Mind Map Learning Technique in Chiropractic Education: A Pilot Study and Literature". Journal of Chiropractic Humanities. 13: 2–11. doi:10.1016/S1556-3499(13)60153-9.

- ^ Farrand, P.; Hussain, F.; Hennessy, E. (2002). "The efficacy of the mind map study technique". Medical Education. 36 (5): 426–431. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.2002.01205.x. PMID 12028392. S2CID 29278241.

- Nesbit, J.C.; Adesope, O.O. (2006). "Learning with concept and knowledge maps: A meta-analysis". Review of Educational Research. 76 (3). Sage Publications: 413–448. doi:10.3102/00346543076003413. S2CID 122082944.

- Beel, Joeran; Langer, Stefan (2011). "An Exploratory Analysis of Mind Maps" (PDF). Proceedings of the 11th ACM Symposium on Document Engineering (DocEng'11). ACM. pp. 81–84. ISBN 978-1-4503-0863-2.

- Brucks, Claudine; Schommer, Christoph (2008). "Assembling Actor-based Mind-Maps from Text Stream". arXiv:0810.4616 .

- Rothenberger, T; Oez, S; Tahirovic, E; Schommer, Christoph (2008). "Figuring out Actors in Text Streams: Using Collocations to establish Incremental Mind-maps". arXiv:0803.2856 .

- US application 2009119584, Herbst, Steve, "Software tool for creating outlines and mind maps that generates subtopics automatically", published 2009-05-07 , since abandoned.

- Santos, Devin (15 February 2013). "Top 10 Totally Free Mind Mapping Software Tools". IMDevin. Archived from the original on 7 August 2013. Retrieved 10 July 2013.

External links

Media related to Mind maps at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Mind maps at Wikimedia Commons

| Group creativity techniques | |

|---|---|

| Argument mapping, concept mapping, and mind mapping software | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOSS |

| |||||

| Proprietary |

| |||||