| Revision as of 10:09, 13 October 2013 editPawyilee (talk | contribs)Extended confirmed users12,162 edits →See also: Kom peoples← Previous edit | Latest revision as of 21:58, 1 December 2024 edit undoKlbrain (talk | contribs)Autopatrolled, Extended confirmed users, New page reviewers87,367 edits Adding missing merge template | ||

| (627 intermediate revisions by more than 100 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| {{Short description|Iranian people mentioned in the Indo-Aryan sources}} | |||

| {{Multiple issues|cleanup = September 2009|primarysources = November 2009|synthesis = November 2009|cite check = September 2009}} | |||

| {{merge|Kambojan language|date=November 2024|discuss=Talk:Kambojan language#Merge proposal}} | |||

| {{EngvarB|date=November 2023}} | |||

| {{Use dmy dates|date=November 2023}} | |||

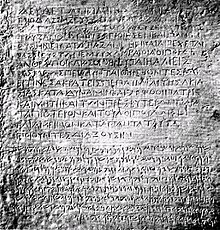

| ] of Ashoka, in which the Kambojas are mentioned.]] | |||

| The '''Kambojas''' were a southeastern ]{{Cref2|a}} who inhabited the northeastern most part of the territory populated by Iranian tribes, which bordered the ]. They only appear in ] inscriptions and literature, being first attested during the later part of the ]. | |||

| They spoke ] similar to ], whose words are considered to have been incorporated in the Aramao-Iranian version of the ] erected by the ] emperor ] ({{reign|268|232|era=BCE}}). They were adherents of ], as demonstrated by their beliefs that insects, snakes, worms, frogs, and other small animals had to be killed, a practice mentioned in the ]n ]. | |||

| The '''Kambojas''' ({{lang-sa|{{linktext|कम्बोज}}}}, ''Kamboja''; {{lang-fa|کمبوہ}}, ''Kambūh'') were a ] tribe of ], frequently mentioned in ] and ]. Modern scholars conclude that the Kambojas were an ] speaking Eastern Iranian tribe who later settled in at the boundary of the ancient India. The Kambojas are classified as a ] or barbarous tribe by the Vedic Inhabitants of India. Indologists believe that Kambojas have adopted Hinduism in a late Vedic Period. | |||

| == Etymology == | |||

| ] India, with the Kamboja on the northwest border]] | |||

| ''Kamboja-'' (later form ''Kāmboja-'') was the name of their territory and identical to the ] name of ''*Kambauǰa-'', whose meaning is uncertain. A long-standing theory is the one proposed by J. Charpentier in 1923, in which he suggests that the name is connected to the name of ] and ] (''Kambū̌jiya'' or ''Kambauj'' in ]), both kings from the ]. The theory has been discussed several times, but the issues that it posed were never persuadingly resolved.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} | |||

| In the same year, ] proposed that the name is of ] origin, though this is typically rejected.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} | |||

| == History == | |||

| ==Ethnicity and language== | |||

| The Kambojas only appear in ] inscriptions and literature, being first attested during the later part of the ]. The ''Naighaṇṭukas'', a glossary and oldest surviving writing about Indian ], is the first source to mention them. In his book about etymology—the '']''—the ancient Indian author ] comments on that part of the ''Naighaṇṭukas'', in which he mentions that "the word ''śavati'' as a verb of motion is used only by the Kambojas", a statement that is more or less repeated in the exact same way by later authors, such as the grammarian ] (2nd-century BCE) in his '']''. The word ''śavati'' is equivalent to ''š́iiauua-'' in ], which demonstrates that the Kambojas spoke an Iranian tongue with close ties to it. Modern historian M. Witzel surmised that grammarians and lexicographers must have first become acquainted with the word around 500 BCE or perhaps earlier, due to Yaska and Patanjali both using the same example known amongst grammarians and lexicographers.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} | |||

| According to ] of ], Kambojas were known as ''vartta-sastropajivinah'', meaning they were a class of ] guilds which lived upon both trade and war.<ref>Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1922). Corporate Life in Ancient India. The Oriental Book Agency, p-29</ref> | |||

| The ancient Kambojas may be related to the present-day ] were an Indo-Iranian tribe.<ref>Dwivedi 1977: 287 "The Kambojas were probably the descendants of the Indo-Iranians popularly known later on as the Sassanians and Parthians who occupied parts of north-western India in the first and second centuries of the Christian era."</ref> They are however, sometimes described as Indo-Aryans<ref name="Mishra 1987">Mishra 1987</ref><ref>Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Achut Dattatrya Pusalker, A. K. Majumdar, Dilip Kumar Ghose, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Vishvanath Govind Dighe. ''The History and Culture of the Indian People'', 1962, p 264,</ref><ref name="Political History of Ancient India">"Political History of Ancient India", H. C. Raychaudhuri, B. N. Mukerjee, University of Calcutta, 1996.</ref> and sometimes as having both Indian and Iranian affinities.<ref name="See p 138">See: Vedic Index of names & subjects by Arthur Anthony Macdonnel, Arthur. B Keath, I.84, p 138.</ref><ref name="Refs 1970, p 107">See more Refs: Ethnology of Ancient Bhārata, 1970, p 107, Ram Chandra Jain; The Journal of Asian Studies, 1956, p 384, Association for Asian Studies, Far Eastern Association (U.S.)</ref><ref>''India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī'', 1953, p 49, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala; Afghanistan, p 58, W. K. Fraser, M. C. Gillet; ''Afghanistan, its People, its Society, its Culture'', Donal N. Wilber, 1962, p 80, 311</ref> The Kambojas are also described as a royal clan of the ].<ref>Thion 1993, p. 51</ref><ref>Walker and Tapp 2001</ref> | |||

| ] of the ] emperor ] ({{reign|268|232|era=BCE}})]] | |||

| ===Iranian characteristics=== | |||

| The ] of the ] emperor ] ({{reign|268|232|era=BCE}}) contain the first attestations of the Kambojas that can be precisely dated. The thirteenth edict says "among Greeks and Kambojas" and the fifth edict says "of Greeks, Kambojas and Gandharians". It is uncertain if Ashoka was only referring to just the Kambojas or all the Iranian tribes in his empire. Regardless, the mentioned groups of people were part of the Maurya Empire, being influenced by its politics, culture and religious traditions, and also adhered to ideology of "righteousness" set by Ashoka.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} | |||

| Linguistic analysis suggests that the Kambojas were ] speaking the ].<ref name="Boyce"/><ref>Persica, 9, 1980, p 92, Michael Witzel.</ref><ref>Oberlies 2001, p.7</ref><ref>Purana, Vol V, No 2, July 1963, p 256, D. C. Sircar; Journal Asiatique, CCXLVI 1958, I, pp 47-48, E. Benveniste; A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire, 1989, p 10, fn 1, M. A. Dandamaev, W. J. Vogelsang; 'K etimologii drevnepersidskikh imen', Etimologija 1965, Moscow, 1967, p 288ff, V. I. Abaev</ref><ref>Witzel 1999b, p. 5</ref><ref>The Afghans (Peoples of Asia), 2001, p 127, also Index, W. J. Vogelsang and Willem Vogelsang; Also Fraser 1979</ref><ref>Boardman et al. 1988, p. 199</ref><ref>"Early Eastern Iran and the Atharvaveda", Persica-9, 1980, fn 81, p 114, Michael Witzel who however, locates the Kambojas in Arachosia and Kandhahar</ref> | |||

| The major Indian epic '']'' also mentions the Kambojas, alongside the Greeks, ]s, Bactrians and ]. Geographical texts in ] and the '']'' include the Kambojas as one of the ] of the ] during the lifetime of ]. Various characteristics of the Kambojas are also described in different types of Sanskrit and ] literature; they shaved themselves bald; they had a king; ''Rāja-pura-'' (meaning "King's town") was the name of their capital, but its site remains unknown. As was typical of Iranians, the Kambojas were renowned for their skill in horse breeding, and it is believed that the horses they produced were the most suitable for use in battle. These horses were brought into India in large quantities and also given as tribute.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}}{{sfn|Sharma|2007|p=145–152}}{{sfn|Boyce|Grenet|1991|pp=129–130}} ] ] further suggests that reputation of Kambojas as homeland of horses possibly earned the horse-breeders known as ] (from Old Persian ''aspa'') and ] (from Sanskrit ''aśva'' "horse") their epithet.{{sfn|Lamotte|1988|p=100}} | |||

| In the ''Mahabharata'' and in ] literature, Kambojas appear in the characteristic Iranian roles of horsemen and breeders of notable horses.<ref name="Boyce"/><ref>The History of Indian Literature, 2005 edition, p 178, Albrecht Weber - Sanskrit literature</ref><ref>Karttunen, 1989, p. 225</ref><ref name="Bongard-Levin 1985, p. 120">Bongard-Levin 1985, p. 120</ref> | |||

| Following the death of Ashoka, the Maurya Empire fell into decline. During the start of the 2nd-century BCE, they lost their Indian-Iranian frontier lands (including Gandhara and ]) to the forces of ] ({{reign|200|180|era=BCE}}), the king of the ]. As a result, the Greek population of those areas were once again under the dominion of their Greek countrymen, while the Kambojas met other Iranians, as the Bactrians were likely a major component of the conquering army along with the Greeks.{{sfn|Boyce|Grenet|1991|p=149}} | |||

| The Kambojas were located partly in north-eastern ]/north-west frontiers province of Pakistan and parts of ].<ref>Ref: Proceedings and Transactions of the All-India Oriental Conference, 1930, p 118; cf: Linguistic Survey of India, Vol X, pp 455-56, G. A. Grierson; cf: History and archaeology of India's contacts with other countries, from earliest times to 300 B.C., 1976, p 152, Shashi P. Asthana - Social Science</ref><ref name="Sethna 2000">Sethna, K. D. (2000) ''Problems of Ancient India'', New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-026-7</ref><ref>Geographical data in the early Purāṇas: a critical study, 1972, p 164 sqq, M. R. Singh - History; Asoka and His Inscriptions, 1968, pp 93-96, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa.</ref><ref>Scholars like H. C. Raychaudhur locate Kamboja from South-west Kashnmir (Abhisara, Rajauri/Poonch) to Kafiristan in Hindukush (See: Political History of Ancient India, 1996, p 132 sqq, H. C. Chaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee; The History and Culture of the Indian People: The age of imperial unity, 1969, p 15, Editors Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Bhāratīya Itihāsa Samiti - India).</ref><ref>Scholars like V. S. Aggarwala etc locate the Kamboja country in Pamirs and Badakshan (Ref: A Grammatical Dictionary of Sanskrit (Vedic): 700 Complete Reviews.., 1953, p 48, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala, Surya Kanta, Jacob Wackernagel, Arthur Anthony Macdonell, Peggy Melcher - India; India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī, 1963, p 38, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala - India; The North-west India of the Second Century B.C., 1974, p 40, Mehta Vasishtha Dev Mohan - Greeks in India; The Greco-Sunga period of Indian history, or, the North-West India of the second century B.C, 1973, p 40, India) and the ] further north, in the Trans-Pamirian territories (See: The Deeds of Harsha: Being a Cultural Study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita, 1969, p 199, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala).</ref><ref>And many scholars like Vladimirovich Gankovskiĭ, Haroon Rashid etc locate Kamboja confederation from south-west Kashmir (Rajaurri) to Kafiristan, Kabul, Ghazni and extending as far as Kandhahar (See: The Peoples of Pakistan: An Ethnic History, 1971, pp 64-67, I︠U︡riĭ Vladimirovich Gankovskiĭ - Ethnology; History of the Pathans, 2002, p 11, Haroon Rashid - Pushtuns).</ref><ref>Sircar says that Kamboja lay roughly to the east and south of Bahlika country, and to the west of Pancala (western Punjab and southern Kashmir) and also comprised Peshawr-Hazara in western Pakistan and Kafiristan-Kandhahar in Afghanistan, including tribal territories lying between the two (See: Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, 1990, p 203, Dineschandra Sircar; Also: Cosmography and geography in early Indian literature, 1967, p 109, Dineschandra Sircar - Indic literature).</ref><ref>Michael Witzel also extends Kamboja including the Kapisa and Kabul valleys to Arachosia/Kandahar (See: Persica-9, p 92, fn 81. Michael Witzel).</ref> | |||

| Some historians consider the Kambojas to have established the ] in ], but this remains uncertain. Some historians consider it to have founded by Kambojas who had settled in Bengal, a theory which may be supported by the attestation of a ''Kambojadeśa'' in the ] by the ]an book ''Pag Sam Jon Zang''. ] proposed that the Kambojas may have travelled to Bengal from the northwestern frontier in the wake of ] conquests during the lifetime of ]. He adds that those Kambojas perhaps acquired positions and, at a suitable time, seized power.{{sfn|Caudhurī|1967|p=73}} | |||

| The ''Bhishamaparava'' and ''Shantiparava'' in the ''Mahabharata'' indicate that the Kambojas were living in the north of India. Like other people of the ] region, they are called '']s'' (barbarians) or ''asuras'', lying outside the Indo-Aryan fold.<ref>Historical and Cultural Chronology of Gujarat, 1960, p 43, Manjulal Ranchholdlal Majmudar</ref><ref>Sarkar, 1987, p. 43</ref><ref>History of Dharmaśāstra: (ancient and Mediæval Religious and Civil Law), 1930, p 13, Pandurang Vaman Kane, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Poona, India.(Bombay)</ref><ref name="Lamotte 1988, p. 106">Lamotte 1988, p. 106</ref> ] reveals that in the lands of Yavanas, Kambojas and some other frontier nations, there were only two classes of people: '']s'' and '']s'', the masters and slaves. The Arya could become Dasa and vice versa.<ref>Majjhima Nikaya 43.1.3</ref> This social organisation was completely alien to India, where a four-class social structure was prevalent.<ref name="Lamotte 1988, p. 106"/> | |||

| ] considers the Nuristani ] (aka Kamôzî or Kamôǰî) to be the descendants of the Kamboja people.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Strand |first=Richard |date=2022 |title=Kamboǰas and Sakas in the Holly-Oak Mountains: On the Origins of the Nûristânîs |url=https://nuristan.info/peristan.pdf |website=Nuristan: Hidden Land of the Hindu Kush}}</ref> | |||

| The ] commentator and scholar ] (2nd or 4th century CE,<ref>2nd century CE according to ''Freedom, Progress and Society: Essays in honor of K. Satchidananda Murty'', 1966, p 109, B. Subramanian, K. Satchidananda).</ref> expressly describes the Kambojas as having Persian affinties.<ref>Quoted in: Journal of the Asiatic Society, 1940, p 256, by India Asiatic Society (Calcutta, Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal.</ref><ref name="Foreign">, Foreign Elements in Ancient Indian Society, 2nd Century BC to 7th Century AD, 1979</ref><ref>Studies in Indian History and Civilization, 1962, p 351, Buddha Prakash; ''Cultural Heritage of India'', p 625, Debala Mitra; Indological Studies, 1950, p 78, Bimala Churn Law.</ref><ref>''Inscriptions of Asoka: Translation and Glossary'', 1990, p 84, Beni Madhab Barua, Binayendra Nath Chaudhury; Journal of the Asiatic Society, 1956, p 256, Asiatic Society (Calcutta, India); ''Indian studies: past & present'', 1964, p 365, Indo-Aryan philology; ''Maurya and Post-Maurya Art: A Study in Social and Formal Contrasts'', 1975, p 36, Niharranjan Ray.</ref><ref>Cf: The Śikh Gurus and the Śikh Society: A Study in Social Analysis, 1975, p 139, Niharranjan Ray.</ref> | |||

| == Language and location == | |||

| The Kambojas' religious customs were ].{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} | |||

| {{Main|Kambojan language}} | |||

| {{location map+ |Afghanistan |float=right|width=250 |caption=Location of the two inscription sites in present-day ], whose engraved Iranian languages have been suggested to have been spoken by the Kambojas | |||

| |places= | |||

| {{location map~ |Afghanistan| label = ] |lat=33.396556|long=68.416056|position=top}} | |||

| {{location map~ |Afghanistan| label = ] |lat=31.732|long=65.8267|position=left}} | |||

| }} | |||

| The Kambojas inhabited the northeastern most part of the territory populated by Iranian tribes, which bordered the Indian lands.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} In 1918, Lévi suggested it to be ], but later retracted it in 1923; B. Liebich suggested they lived in the ]; J. Bloch suggested that they lived to the north-east of ]; Lamotte considered them to live them from Kafiristan to the southwestern part of ].{{sfn|Lamotte|1988|p=100}}{{sfn|Bailey|1971|p=66}} | |||

| In 1958, a new suggestion was put forward by the French linguist ].{{sfn|Bailey|1971|p=66}} He drew a comparison between the Kambojas and Greeks described in Ashoka's ] and the two languages it was written in; Greek and "Aramao-Iranian", which refers to the Iranian language hidden in the text of the ]. Ashoka wanted to use these two languages to convey his religious message to the inhabitants of what is now present-day eastern ], around the Gandhara area, approximately between Kabul and Kandahar. Because of this, Benveniste considered the Iranian language used in Ashoka's inscriptions to be spoken by the Kambojas.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} The ] ] and Frantz Grenet also support this view, saying that "The fact that Aramaic versions were made indicates that the Kambojas enjoyed a measure of autonomy, and that they not only preserved their Iranian identity, but were governed in some measure by members of their own community, on whom was laid the responsibility of transmitting to them the king's words, and having these engraved on stone."{{sfn|Boyce|Grenet|1991|p=136}} | |||

| ===Indo-Aryan characteristics=== | |||

| Various ancient documents, such as the ''Vamsa Brahmana'' and ''Rig Veda'', mention "Kamboja" in the context of the Indo-Aryan civilisation. These references have made various scholars argue that the Kambojas were Indo-Aryans and that in the early Vedic times they formed an important division of the Vedic Aryans.<ref name="Political History of Ancient India"/><ref name="Sethna 2000"/><ref>''The History and Culture of the Indian People'', 1962, p 264, Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Achut Dattatrya Pusalker, A. K. Majumdar, Dilip Kumar Ghose, K. M. Munshi</ref> | |||

| ] suggested that the unidentified Iranian language of the two rock-inscriptions (IDN 3 and 5) in ] was spoken by the Kambojas, perhaps an early stage of the ]. According to Rüdiger Schmitt; "If this hypothesis should prove to be true, we would be able to locate the Kambojas more precisely in the mountains around ] and on the Upper ]."{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} | |||

| Some versions of ] <ref>Ch. 95, verse 18; see also: Vedic Index, Vol 1(Hindi Translation), page 138 , A. A. Keith, Arthur Berridale; Iranians and Greeks in Ancient Panjab, 1973' p 3, fn 15, D. C. Sircar</ref> refer to name "Kamboja" as one of the Brahmana Gotras, having Bhargava, Chyavana, Aurva, Jamadagnya & Apnuvana as its Pravara---whereas the other versions substitute "Vatsa" for "Kamboja". Pt Bhupindranatha Datta observes that a ] from amongst the ancient Kamboja people had founded this "Kamboja" Gotra.<ref>See: Dielectrics of Hindu Ritualism, 1956, pp 59/60, Bhupindranath Datta; See also: Hindu Law of Inheritance-- An Anthropological Study, 1957, p 3</ref> | |||

| == Religious beliefs == | |||

| ==Origins== | |||

| The ] considered the Kambojas to be "non-Aryan" (''anariya-'') strangers with their own peculiar traditions, as demonstrated in a portion of the ] ]. Insects, snakes, worms, frogs, and other small animals had to be killed according to the Kambojas' religious beliefs.{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}}{{sfn|Boyce|Grenet|1991|pp=129–130}} This practice has been linked by academics to the ]n ] for a long time, leading them to the conclusion that the Kambojas were adherents of ].{{sfn|Schmitt|2021}} These beliefs are based on Zoroastrian dualism, which attributes the Evil Spirit to creatures like these and others that are poisonous or repulsive to humans. Hence, Zoroastrians were commanded to destroy them, and careful pursuit of this goal has been observed by outside spectators since the 5th-century BCE to the present.{{sfn|Boyce|Grenet|1991|p=130}} | |||

| The earliest reference to the Kamboja is in the works of ], around the 5th century BCE. Other pre-] references appear in the '']'' (2nd century) and the '']'' (1st century), both of which described the Kambojas as former kshatriyas who had degraded through a failure to abide by Hindu sacred rituals.<ref name="West">''Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania'', Barbara A. West, Infobase Publishing (2009), ISBN 9781438119137 p. 359</ref> Their territories were located beyond ], which lay in the area of northern ] and eastern ],<ref>Encyclopaedia Indica, "The Kambojas: Land and its Identification", First Edition, 1998 New Delhi, page 528</ref> and the 3rd century BCE '']'' refers to the area under Kamboja control as being independent of the ] in which it was situated.<ref name="West" /> | |||

| == Notes == | |||

| Some sections of the Kambojas crossed the ] and planted Kamboja colonies in ] and as far as ]. The ''Mahabharata'' locates the Kambojas on the near side of the Hindu Kush as neighbors to the ], and the ]s across the Hindu Kush as neighbors to the ]s (or ]s) of the ] region.<ref name="Sethna 2000"/><ref>Numerous scholars now locate the Kamboja realm on the southern side of the Hindu Kush ranges (in the ], ], and ] valleys) and the Parama-Kambojas in the territories on the north side of the Hindu Kush. See: Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 11-13, Moti Chandra - India; ''Geographical Data in the Early Purāṇas: A Critical Study'', 1972, p 165/66, M. R. Singh</ref><ref>''Purana'', Vol VI, No 1, January 1964, p 207 sqq; ''Inscriptions of Asoka: Translation and Glossary'', 1990, p 86, Beni Madhab Barua, Binayendra Nath Chaudhury - Inscriptions, Prakrit).</ref> | |||

| {{Cnote2 Begin|liststyle=upper-alpha}} | |||

| {{Cnote2|a|Scholarship agree that the Kambojas were Iranian.<ref>{{harvnb|Schmitt|2021}}; {{harvnb|Boyce|Grenet|1991|p=129}}; {{harvnb|Scott|1990|p=45}}; {{harvnb|Kubica|2023|p=88}}; {{harvnb|Emmerick|1983|p=951}}; {{harvnb|Fussman|1987|pp=779–785}}; {{harvnb|Eggermont|1966|p=293}}.</ref> ] stated that "Their location and the meaning of the word Kamboja are much debated, but it is at least agreed that they were Iranians living to the northwest of the subcontinent."{{sfn|Frye|1984|p=154}} | |||

| }} | |||

| {{Cnote2 End}} | |||

| {{notelist}} | |||

| == See also == | |||

| The confederation of the Kambojas may have stretched from the valley of Rajauri in the south-western part of Kashmir to the Hindu Kush Range; in the south–west the borders extended probably as far as the regions of Kabul, Ghazni and Kandahar, with the nucleus in the area north-east of the present day Kabul, between the Hindu Kush Range and the ] river, including ]<ref>The Peoples of Pakistan: An Ethnic History, 1971, pp 64-67, Yuri Vladimirovich Gankovski - Ethnology.</ref><ref>History of the Pathans, 2002, p 11, Haroon Rashid - Pushtuns.</ref> possibly extending from the Kabul valleys to Kandahar.<ref>] Persica-9, p 92, fn 81.</ref> | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| == References == | |||

| Others locate the Kambojas and the Parama-Kambojas in the areas spanning ], Badakshan, the Pamirs and ],<ref>Asoka and His Inscriptions, 1968, pp 93-96, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa.</ref> or in various settlements in the wide area lying between Punjab, Iran and Balkh.<ref>Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India, 1971, p 100, D. C. Sircar.</ref><ref>Mandal and Sinha 1980, p. 57</ref> and the Parama-Kamboja even farther north, in the Trans-Pamirian territories comprising the ] valley, towards the Farghana region, in the ] of the classical writers.<ref name="Mishra 1987"/><ref>See: ''Proceedings and Transactions of the All-India Oriental Conference'', 1930, p 118, J. C. Vidyalankara</ref><ref>''The Deeds of Harsha: Being a Cultural Study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita'', 1969, p 199, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala</ref> The mountainous region between the ] and ] is also suggested as the location of the ancient Kambojas.<ref>''Central Asiatic Provinces of the Mauryan Empire'', p 403, H. C. Seth; See also: ''Indian Historical Quarterly'', Vol. XIII, 1937, No 3, p. 400; ''Journal of the Asiatic Society'', 1940, p 37, (India) Asiatic Society (Calcutta, Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal - Asia; cf: ''History and Archaeology of India's Contacts with Other Countries, from Earliest Times to 300 B.C.'', 176, p 152, Shashi P. Asthana; ''Mahabharata Myth and Reality'', 1976, p 232, Swarajya Prakash Gupta, K. S. Ramachandran. Cf also: ''India and Central Asia'', p 25 etc, P. C. Bagchi.</ref> | |||

| {{sfn whitelist|CITEREFSchmitt2021|CITEREFEmmerick1983|CITEREFFussman1987}} | |||

| The name ] may derive from (''Kam + bhuj''), referring to the people of a country known as "Kum" or "Kam". The mountainous highlands where the Jaxartes and its confluents arise are called the highlands of the ] by Ptolemy. ] also names these mountains as ''Komedas''.<ref>''Indian Historical Quarterly'', 1963, p 403; Central Asiatic provinces of the Maurya Empire, p403, H.C. Seth</ref><ref>''History and Archaeology of India's Contacts with Other Countries, from Earliest Times to 300 B.C.'', 1976, p 152, Shashi Asthana; ''Mahabharata Myth and Reality'', 1976, p 232, Swarajya Prakash Gupta, K. S. Ramachandran.</ref><ref>"The Town of Darwaz in Badakshan is sill called Khum (Kum) or Kala-i-Khum. It stands for the valley of Basht. The name Khum or Kum conceals the relics of ancient Kamboja" (''Journal of the Asiatic Society'', 1956, p 256, Buddha Prakash ).</ref> The ''Kiu-mi-to'' in the writings of ] have also been identified with the ''Komudha-dvipa'' of the ] literature and the Iranian Kambojas.<ref>''India and the World'', p 71, Buddha Prakash; also see: ''Central Asiatic Provinces of Maurya Empire'', p 403, H. C. Seth; ''India and Central Asia'', p 25, P. C. Bagchi</ref><ref>''Journal of the Asiatic Society'', 1956, p 256, Asiatic Society (Calcutta, India), Asiatic Society of Bengal.</ref> | |||

| The two Kamboja settlements on either side of the Hindu Kush are also substantiated from Ptolemy's ], which refers to the ''Tambyzoi'' located north of the Hindu Kush on the river Oxus in ], and the ''Ambautai'' people on the southern side of Hindukush in the Paropamisadae.{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} Scholars have identified both the Ptolemian ''Tambyzoi'' and ''Ambautai'' with Sanskrit ''Kamboja''.<ref name="Sethna 2000"/><ref name="Talbert 2000, p. 99">Talbert 2000, p. 99</ref><ref>For Tambyzoi=Kamboja, see refs: Pre Aryan and Pre Dravidian in India, 1993, p 122, Sylvain Lévi, Jean Przyluski, Jules Bloch, Asian Educational Services; Cities and Civilization, 1962, p 172, Govind Sadashiv Ghurye</ref><ref>Lalye 1985, p. 133</ref><ref>For Ambautai=Kamboja, see Witzel 1999a</ref><ref>Patton and Bryant 2005, p. 257</ref> Ptolemy also mentions a people called ''Khomaroi'' and ''Komoi'' in Sogdiana.<ref>Geography 6.18.3; Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, p 199; Ancient India as Described by Ptolemy: Being a Translation of the Chapters, 1885, p 268, John Watson McCrindle - Geography, Ancient.</ref> The Ptolemian ''Komoi'' is a classical form of ''Kamboi'' (or ''Kamboika'', from ] ''Kambojika'', Sanskrit ''Kamboja'').<ref>The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 403; Central Asiatic Provinces of Maurya Empire, p 403, H. C. Seth.</ref> | |||

| The Kambojas on the far side of the Hindu Kush remained essentially Iranian in culture and religion, while those on the near side came under Indian cultural influence.<ref>Vedic Index I, p 138, Macdonnel, Keith.</ref><ref>Ethnology of Ancient Bhārata–1970, p 107, Ram Chandra Jain.</ref><ref>The Journal of Asian Studies–1956, p 384, Association for Asian Studies, Far Eastern Association (U.S.).</ref><ref>India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī–1953, p 49, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala.</ref><ref>Afghanistan, p 58, W. K. Fraser, M. C. Gillet.</ref><ref>Afghanistan, its People, its Society, its Culture, Donal N. Wilber, 1962, p 80, 311 etc.</ref><ref>Iran, 1956, p 53, Herbert Harold Vreeland, Clifford R. Barnett.</ref><ref>Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 33, Moti Chandra - India.</ref> | |||

| ===Theory of Origin - Eurasian Nomads=== | |||

| Some scholars believe that the Trans-Caucasian hydronyms and toponyms viz. Cyrus, Cambyses and Cambysene were due to ] extension of the Iranian ethnics — the Kurus and Kambojas of the Indian texts, who according to them, had moved to the north of the Medes in Armenian Districts in remote antiquity.<ref>Histoire Auguste: Pt. 2. Vies des deux Valérines et des deux Galliens, 2000, p 90, Ammn Marcellin, Jean Pierre Callu, O. Desbordes (''Les hydronymes de Transcaucasie, en question ici, auraient pu, dès lors, aussi dériver aussi de ces ethniques, lors de l'extension des tribus iraniennes vers le Nord de la Médie, et non pas de ces souverains achéménides — dont la présente légende répond mieux à l'ingéniosité «heurématique» des Grecs'')</ref> The Cambyses (Jora/Yori or Gori) was the sacred river Champsis of the Scythians before they went to the north Caucasus isthmus via Caspian and Nlanytsch.<ref>The Deluged Civilization of the Caucasus Isthmus, Chapter 11, The Egyptian and Aryan Home-lands, section 12, Reginald Aubrey Fessendan.</ref> | |||

| But ] scholar ] speculates that the Kambojas of the Kabul/Indus-land as mentioned in the Indian texts had originally migrated from Kambuja (Kambysene) of Transcaucasian Steppe (in Armenia and Albania).<ref>Zeitschrift der Deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft, 1872, p 716, Friedrich Spiegel, Cf also: Erânische Alterthumskunde, 1871, p 442</ref> Chandra Chakraberty also theorizes that the Kambojas---''the Kambohs of NW Panjab was a branch of the ] Cambysene from ancient Armenia''.<ref>Literary History of Ancient India, in Relation to Its Racial and Linguistic Affiliations, 2010, p 165, Chandra Chakraberty</ref> | |||

| As against the above, Buddha Prakash, S. Misra and others have done further research on this topic and have come to the conclusion that the Kurus and Kambojas were in fact, a ] from the ]n ] who, as a composite horde, had entered ], ], ] as well as ] through the passage between the ] and the ] around 8th or 9th century BCE (or even earlier).{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} | |||

| ==The Kambojan States== | |||

| The capital of Kamboja was probably ] (modern Rajori). The ''Kamboja Mahajanapada'' of Buddhist traditions refers to this cis-Hindukush branch.<ref>See: Problems of Ancient India, 2000, p 5-6; cf: Geographical Data in the Early Puranas, p 168.</ref> | |||

| ]'s '']'' and ]'s Edict No. XIII attest that the Kambojas followed a republican constitution. Pāṇini's Sutras tend to convey that the Kamboja of Pāṇini was a "Kshatriya monarchy", but "the special rule and the exceptional form of derivative" he gives to denote the ruler of the Kambojas implies that the king of Kamboja was a titular head (''king consul'') only.<ref>''Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times'', Parts I and II., 1955, p 52, Dr Kashi Prasad Jayaswal - Constitutional history; Prācīna Kamboja, jana aura janapada =: Ancient Kamboja, people and country, 1981, Dr Jiyālāla Kāmboja - Kamboja (Pakistan).</ref> | |||

| ===The Aśvakas=== | |||

| {{main|Aśvakas}} | |||

| The Kambojas were famous in ancient times for their excellent breed of horses and as remarkable horsemen located in the ''Uttarapatha'' or north-west.<ref>The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 103</ref><ref name="hindupolity">Hindu Polity, 1978, pp 121, 140, K. P. Jayswal.</ref><ref name="Early Greek Literature 1989, p 225">India in Early Greek Literature: academic dissertation, 1989, p 225, Klaus Karttunen - Greek literature.</ref> They were constituted into military '']s'' and corporations to manage their political and military affairs.{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} The Kamboja cavalry offered their military services to other nations as well. There are numerous references to Kamboja having been requisitioned as cavalry troopers in ancient wars by outside nations.<ref>War in Ancient India, 1944, p 178, V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar - Military art and science.</ref><ref>The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 103; The Achaemenids in India, 1950, p 47, Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya; Poona Orientalist: A Quarterly Journal Devoted to Oriental Studies, 1945, P i, (edi) Har Dutt Sharma; The Poona Orientalist, 1936, p 13, Sanskrit philology; Tribes in Ancient India, 1943, p 4, B. C. Law - Ethnology; The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1949, p 103.</ref> | |||

| It was on account of their supreme position in horse (''Ashva'') culture that the ancient Kambojas were also popularly known as '']s'', i.e. horsemen. Their clans in the ] and ] valleys have been referred to as ''Assakenoi'' and ''Aspasioi'' in classical writings, and ''Ashvakayanas'' and ''Ashvayanas'' in Pāṇini's ''Ashtadhyayi''. | |||

| {{quote|The Kambojas were famous for their horses and as cavalry-men (aśva-yuddha-Kuśalah), Aśvakas, 'horsemen', was the term popularly applied to them... The Aśvakas inhabited Eastern Afghanistan, and were included within the more general term Kambojas.|K.P.Jayswal<ref name="hindupolity" />}} | |||

| {{quote|Elsewhere Kamboja is regularly mentioned as "the country of horses" (Asvanam ayatanam), and it was perhaps this well-established reputation that won for the horsebreeders of Bajaur and Swat the designation Aspasioi (from the Old Pali aspa) and assakenoi (from the Sanskrit asva "horse").|]<ref>"Par ailleurs le Kamboja est régulièrement mentionné comme la "patrie des chevaux" (Asvanam ayatanam), et cette reputation bien etablie gagné peut-etre aux eleveurs de chevaux du Bajaur et du Swat l'appellation d'Aspasioi (du v.-p. aspa) et d’assakenoi (du skt asva "cheval")". E. Lamotte, ''Historie du Bouddhisme Indien'', p. 110. (WP translation. Quotation should be taken from the published English translation: Lamotte 1988, p. 100)</ref>}} | |||

| ===Alexander's Conflict with the Kambojas=== | |||

| {{main|Alexander's Conflict with the Kambojas}} | |||

| ].]] | |||

| The Kambojas entered into conflict with ] as he invaded Central Asia. The Macedonian conqueror made short shrifts of the arrangements of ] and after over-running the Achaemenid Empire he dashed into ]. There he encountered incredible resistance of the Kamboja ''Aspasioi'' and ''Assakenoi'' tribes.<ref>Panjab Past and Present, pp 9-10; also see: History of Porus, pp 12, 38, Buddha Parkash</ref><ref>Proceedings, 1965, p 39, by Punjabi University. Dept. of Punjab Historical Studies - History.</ref> | |||

| These Ashvayana and Ashvakayana clans fought the invader to a man. When worse came to worst, even the Ashvakayana Kamboj women took up arms and joined their fighting husbands.{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} | |||

| The Ashvakas fielded 30,000 strong cavalry, 30 elephants and 20,000 infantry against Alexander. | |||

| The Ashvayans (Aspasioi) were also good cattle breeders and agriculturists. This is clear from the large number of bullocks, 230,000 according to ], of a size and shape superior to what the ]s had known, that Alexander captured from them and decided to send to Macedonia for agriculture.<ref name="Punjab">''History of Punjab'', 1997, Editors: Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi</ref><ref>Acharya 2001, p 91</ref> | |||

| ==Migrations== | |||

| During the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, clans of the Kambojas from north Afghanistan in alliance the with Sakas, ] and the ] entered India, spread into Sindhu, Saurashtra, Malwa, Rajasthan, Punjab and Surasena, and set up independent principalities in western and south-western India. Later, a branch of the same people took Gauda and Varendra territories from the ] and established the ] of Bengal in Eastern India.<ref>Yadav and Gupta 1996, p. 173</ref><ref>''Geographical Data in the Early Purāṇas: A Critical Study'', 1972, p 168, M. R. Singh - India.</ref><ref>''History of Ceylon'', 1959, p 91, Ceylon University, University of Ceylon, Peradeniya, Hem Chandra Ray, K. M. De Silva.</ref><ref>Pande (R.) 1984, p. 93</ref> | |||

| There are references to the hordes of the Sakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, and Pahlavas in the ] of the ]. In these verses one may see glimpses of the struggles of the Hindus with the invading hordes from the north-west.<ref name="Political History of Ancient India"/><ref>Shrava 1981, p. 12</ref><ref>Rishi, 1982, p. 100</ref><ref>''Indological Studies'', 1950, p 32, B. C. Law</ref> The invading hordes from the north-west entered Punjab, Sindhu, Rajasthan and Gujarat in large numbers, wrested political control of northern India from the Indo-Aryans and established their respective kingdoms as independent rulers in the land of the Indo-Aryans, as also attested by the ''Mahabharata'' as well as the '']''.{{citation needed|date=June 2013}} There is literary as well as inscriptional evidence supporting the Yavana and Kamboja overlordship in ] in Uttar Pradesh.{{cn|date=July 2013}} The royal family of the ]s mentioned in the ] are believed to be linked to the royal house of ] in ].<ref>See: ''Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum'', Vol II, Part I, p xxxvi; see also p 36, Sten Konow; ''Indian Culture'', 1934, p 193, Indian Research Institute; Cf: ''Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland'', 1990, p 142, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland - Middle East.</ref> The ] of ], in all probability, belonged to the Kambojas, who had settled down in south-western India around the beginning of the Christian era. In the medieval era, the Kambojas are known to have seized north-west Bengal (''Gauda'' and ''Radha'') from the ] of ] and established their own ]. Indian texts like '']'', ''Vishnu Dharmottari'' ''Agni Purana'',<ref>''Indian Historical Quarterly'', 1963, p 127</ref> | |||

| ===Eastern Kambojas=== | |||

| {{see also|Kamboja-Pala Dynasty of Bengal}} | |||

| A branch of Kambojas seems to have migrated eastwards towards Tibet in the wake of ] (1st century) or else ] (5th century) pressure and hence their notice in the chronicles of ] ("Kam-po-tsa, Kam-po-ce, Kam-po-ji") and ] (Kambojadesa).<ref>Shastri and Choudhury 1982, p. 112</ref><ref>B. C. Sen, ''Some Historical Aspects of the Inscriptions of Bengal'', p. 342, fn 1</ref><ref>Vaidya 1986, p. 221</ref> The 5th-century ] mentions the Kambojas around ] and ].<ref>M. R. Singh, ''A Critical Study of the Geographical Data in the Early Puranas'', p. 168</ref><ref>''Pala-Sena Yuger Vamsanucarita'', p. 70</ref><ref>Ganguly 1994, p. 72, fn 168</ref><ref>H. C. Ray, ''The Dynastic History of Northern India'', I, p. 309</ref><ref>A. D. Pusalkar, R. C. Majumdar et al., ''History and Culture of Indian People'', Imperial Kanauj, p. 323,</ref> | |||

| {{quote|The Kambojas of ancient India are known to have been living in north-west, but in this period (9th century AD), they are known to have been living in the north-east India also, and very probably, it was meant Tibet.|R.R. Diwarkar<ref>R. R. Diwarkar (ed.), ''Bihar Through the Ages'', 1958, p. 312</ref>}} | |||

| Later these Kambojas appear to have moved towards ] from where they may have invaded ] during the ] and wrested north-west Bengal from them.{{Citation needed|date=January 2010}} These Kambojas had made a first bid to conquer Bengal during the reign of king ] (810–850) but were repulsed. A later attempt was successful when they were able to deprive the Palas of the suzerainty over northern and western Bengal and set up a ] towards the middle of the 10th century.<ref name="Law 1924">Law 1924</ref> | |||

| ==Mauryan period== | |||

| {{see also|Maurya Empire}} | |||

| The Kambojas find prominent mention as a unit in the 3rd-century BCE ]. Rock Edict XIII tells us that the Kambojas had enjoyed autonomy under the Mauryas.<ref name="Political History of Ancient India"/><ref name="Boyce"/><ref>H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee; Asoka and His Inscriptions, 3d Ed, 1968, p 149, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa.</ref> The republics mentioned in Rock Edict V are the ]s, Kambojas, ]s, Nabhakas and the Nabhapamkitas. They are designated as ''araja. vishaya'' in Rock Edict XIII, which means that they were kingless, i.e. republican polities. In other words, the Kambojas formed a self-governing political unit under the Maurya emperors.<ref>Hindu Polity, A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, 1978, p 117-121, K. P. Jayswal; Ancient India, 2003, pp 839-40, V. D. Mahajan; Northern India, p 42, Mehta Vasisitha Dev Mohan etc</ref><ref>Bimbisāra to Aśoka: With an Appendix on the Later Mauryas, 1977, p 123, Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya.</ref> | |||

| ] sent missionaries to the Kambojas to convert them to ], and recorded this fact in his Rock Edict V.<ref>The North-west India of the Second Century B.C., 1974, p 40, Mehta Vasishtha Dev Mohan - India; Tribes in Ancient India, 1973, p 7, B. C. Law - Ethnology</ref><ref>Anand 1996, p. 79</ref><ref>Yar-Shater 1983, p. 951</ref> | |||

| ==Modern Descendants== | |||

| The ] tribe of the ]<ref name="Literary History">''Literary History of Ancient India'', 1952, Chandra Chakraverty</ref><ref>Bhatia 1984, p. 50</ref><ref>Jindal 1992, p. 149</ref> and the ] and ] of the ] in the ] province of Afghanistan<ref name="Political History of Ancient India"/> are believed by scholars to represent some of the modern descendants of the Kambojas. | |||

| Another branch of the Scythian ''Cambysene'' reached the ] where they mixed with the locals, and some Tibetans are still called Kambojas.<ref name=Chakraberty>''The Racial History of India'' - 1944, Chandra Chakraberty</ref> | |||

| ==See also== | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| * ] | |||

| ==References== | |||

| {{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

| == |

== Sources == | ||

| * {{cite book |last=Bailey|first=H. W.|authorlink=Harold Walter Bailey|chapter=Ancient Kamboja |title=Iran and Islam: In Memory of the Late Vladimir Minorsky |publisher=Edinburgh University Press |year=1971 |pages=65–71|isbn=978-0085224201|editor=] |url=https://archive.org/details/iranislaminmemor0000unse}} | |||

| * Acharya, K. T. (2001) ''A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food'' (Oxford India Paperbacks). ISBN 978-0-19-565868-2 | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Boyce |first1=Mary |author-link1=Mary Boyce|last2=Grenet |first2=Frantz |editor1-last=Beck |editor1-first=Roger |title=A History of Zoroastrianism, Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman Rule |date=1991 |publisher=Brill |location=Leiden|isbn=978-9004293915}} | |||

| * Anand, Ashok Kumar (1996) ''Buddhism in India: From the Sixth Century B.C. to the Third Century A.D.''. New Delhi: Gyan Pub. House. ISBN 81-212-0506-9 | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Caudhurī|first=Ābadula Mamina|title=Dynastic History of Bengal, C. 750-1200 A.D. |date=1967 |publisher=Asiatic Society of Pakistan}} | |||

| * Barnes, Ruth and David Parkin (eds.) (2002) ''Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology on the Indian Ocean''. London: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1235-6 | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Eggermont|first=P.H.L.|title=The Murundas and the Ancient Trade-Route From Taxila To Ujjain|publisher=Brill |year=1966|pages=257–296|journal=Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient|volume=9 |issue=3 |doi=10.1163/156852066X00119}} | |||

| * Bhatia, Harbans Singh (1984) ''Political, legal, and military history of India''. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications | |||

| * {{Cambridge History of Iran|volume=3b|last=Emmerick|first=R. E.|chapter=Buddhism among Iranians|pages=949–964}} | |||

| * Bhattacharyya, Alakananda (2003) ''The Mlechchhas in Ancient India'', Kolkata: Firma KLM. ISBN 81-7102-112-3 | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Kubica |first1=Olga |title=Greco-Buddhist Relations in the Hellenistic Far East: Sources and Contexts |date=2023 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-1032193007}} | |||

| * Boardman, John and N. G. L. Hammond, D. M. Lewis, and M. Ostwald (1988) ''The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 4, Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean (c. 525 to 479 BC)''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22804-2 | |||

| * {{Encyclopaedia Iranica | volume=2 | fascicle=7 | title = Aśoka ii. Aśoka and Iran | last = Fussman | first = G. | url = https://iranicaonline.org/articles/asoka-mauryan-emperor#pt2 | pages = 779–785 }} | |||

| * Bongard-Levin, Grigoriĭ Maksimovich (1985) ''Ancient Indian Civilization''. New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann | |||

| * {{cite book | title = The History of Ancient Iran | year = 1984 | publisher = C.H. Beck | last = Frye | first = R. N. | authorlink = Richard N. Frye | isbn = 978-3406093975 | url = https://archive.org/details/historyofancient0000frye | url-access = registration }} | |||

| * Bowman, John Stewart (2000) ''Columbia chronologies of Asian history and culture'', New York; Chichester: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11004-9 | |||

| * {{cite book |last1=Lal |first1=Deepak |author-link=Deepak Lal |title=The Hindu Equilibrium: India C.1500 B.C. - 2000 A.D. |date=2005 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-927579-3 |page=xxxviii |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=dps-A5gOmA8C&pg=PR38 |language=en}} | |||

| * Boyce, Mary and Frantz Grenet (1991) ''A History of Zoroastrianism'', Vol. 3, Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-09271-4 | |||

| * {{cite book |last=Lamotte|first=Etienne Lamotte|author-link1=Etienne Lamotte|editor1-last=Webb-Boin|editor1-first=Sara|title=History Of Indian Buddhism |date=1988|publisher=Peters Press|isbn=978-9068311006}} | |||

| * Chaumont, Marie Louise (2005) "Cambysene", ''Encyclopædia Iranica Online''. ISBN 1-56859-050-4 | |||

| * {{Encyclopædia Iranica Online|url=https://referenceworks.brillonline.com/entries/encyclopaedia-iranica-online/kamboja-COM_337524?lang=en|title=Kamboja|first=Rüdiger|last=Schmitt|authorlink=Rüdiger Schmitt|year=2021}} | |||

| * Collins, Steven (1998) ''Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities: Utopias of the Pali Imaginaire''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57054-9. ISBN 0-521-57842-6 ISBN 978-0-521-57842-4 | |||

| * {{cite journal |last=Scott|first=David Alan|year=1990|title=The Iranian Face of Buddhism |journal=East and West|volume=40 |issue =1 |pages=43–77 |jstor=29756924 }} {{Registration required}} | |||

| * Dandamayev, Muhammad A. (2005) "Cambyses", ''Encyclopædia Iranica Online'', available at www.iranica.com. ISBN 1-56859-050-4 | |||

| *{{cite book |last=Sharma |first=Ram Sharan |author-link=Ram Sharan Sharma |title=India's Ancient Past |date=2007 |publisher=Oxford University Press |language=en |url=https://academic.oup.com/book/27690 |pages=145–152 |chapter= Chapter 15: Territorial States and the Rise of Magadha |quote=The rise of large states with towns as their base of operations strengthened the territorial idea. People owed strong allegiance to the janapada or the territory to which they belonged rather than to their jana or tribe. The Pali texts reveal that the janapadas grew into mahajanapadas. Gandhara and Kamboja were important mahajanapadas. Kamboja is called a janapada in Panini and a mahajanapada in the Pali texts. |isbn=9780199080366}} | |||

| * Dandamaev, M.A. (1989) ''A Political History of the Achaemenid Empire''. W.J. Vogelsang (trans). Leiden, New York: E.J. Brill, 1989. ISBN 90-04-09172-6 | |||

| * Drabu, V. N. (1986) ''Kashmir Polity, c. 600-1200 A.D.'' New Delhi: Bahri Publications. Series in Indian history, art, and culture; 2. ISBN 81-7034-004-7 | |||

| * Frye, Richard Nelson (1984) ''The History of ancient Iran''. München: Beck. ISBN 3-406-09397-3 | |||

| * Ganguly, Dilip Kumar (1994) ''Ancient India, History and Archaeology''. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-304-3 | |||

| * Dwivedi, R. K., (1977) "A Critical study of Changing Social Order at Yuganta: or the end of the Kali Age" in Lallanji Gopal, J.P. Singh, N. Ahmad and D. Malik (eds.) (1977) ''D.D. Kosambi commemoration volume''. Varanasi: Banaras Hindu University. | |||

| * Jha, Jata Shankar (ed.) (1981) ''K.P. Jayaswal commemoration volume''. Patna: K P Jayaswal Research Institute | |||

| * Jindal, Mangal Sen (1992) ''History of Origin of Some Clans in India, with Special Reference to Jats''. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-85431-08-6 | |||

| * Kāmboja, Jiyālāla L. and Satyavrat Śāstrī (1981) ''Prācīna Kamboja, jana aura janapada'' (Ancient Kamboja, people and country) Delhi: Īsṭarna Buka Liṅkarsa (in Hindi) | |||

| * Karttunen, Klaus (1989) ''India in Early Greek Literature''. Helsinki: Finnish Oriental Society. ISBN 951-9380-10-8 | |||

| * Lalye. P. G. (1985) ''Purana-vimar'sucika: Bibliography of Articles on Puranas''. Hyderabad: P. G. Lalye, | |||

| * Lamotte, Etienne (1988) ''History of Indian Buddhism: From the Origins to the Saka Era''. Sara Webb-Boin and Jean Dantinne (transl.) Louvain-la-Neuve: Université Catholique de Louvain, Institut Orientaliste. ISBN 90-6831-100-X | |||

| * Law, Bimal Churn (1924) ''Some Ksatriya Tribes Of Ancient India''. Calcutta: University of Calcutta. | |||

| * Mandal, R. B. and Vishwa Nath Prasad Sinha (1980) ''Recent Trends and Concepts in Geography''. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Co. | |||

| * Mishra, Krishna Chandra (1987) ''Tribes in the Mahabharata: A Socio-cultural Study''. New Delhi, India: National Pub. House. ISBN 81-214-0028-7 | |||

| * Misra, Satiya Deva (ed.) (1987) ''Modern Researches in Sanskrit: Dr. Veermani Pd. Upadhyaya Felicitation Volume''. Patna: Indira Prakashan | |||

| * Oberlies, Thomas (2001) ''Pāli: A Grammar of the Language of the Theravāda Tipiṭaka'', Berlin, New York: De Gruyter ISBN 3-11-016763-8 | |||

| * Pande, Govind Chandra (1984) ''Foundations of Indian Culture'', Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass ISBN 81-208-0712-X (1990 edition.) | |||

| * Pande, Ram (ed.) (1984) ''Tribals Movement [proceedings of the National Seminar on Tribals of Rajasthan held on 9–10 April 1983 at Jaipur under the auspices of Shodhak in collaboration of Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi.'' Jaipur: Shodhak | |||

| * Patton, Laurie L. and Edwin Bryant (eds.) ( 2005) ''Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History'', London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1462-6 ISBN 0-7007-1463-4 | |||

| * Ramakrishna, M. (1981) ''Bhat Varāhamihira's Bṛhat Saṁhitā''. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass | |||

| * Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982) ''India & Russia: Linguistic & Cultural Affinity''. Chandigarh: Roma Publications | |||

| * Sarkar, Amal (1987) ''A Study on the Rāmāyanas''. Calcutta: Rddhi-India | |||

| * Sathe, Shriram (1987) ''Dates of the Buddha''. Hyderabad: Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti Hyderabad | |||

| * Sethna, K. D. (2000) ''Problems of Ancient India'', New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-026-7 | |||

| * Sethna, Kaikhushru Dhunjibhoy (1989) ''Ancient India in a new light''. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-85179-12-3 | |||

| * Shastri, Biswanarayan (ed.) and Pratap Chandra Choudhury, (1982) ''Abhinandana-Bhāratī: Professor Krishna Kanta Handiqui Felicitation Volume''. Gauhati: Kāmarūpa Anusandhāna Samiti | |||

| * Shrava, Satya (1981 ) ''The Śakas in India''. New Delhi: Pranava Prakashan | |||

| * Singh, Acharya Phool (2002) ''Philosophy, religion and Vedic education'', Jaipur: Sublime. ISBN 81-85809-97-6 | |||

| * Singh, G. P., Dhaneswar Kalita, V. Sudarsen and Mohammed Abdul Kalam (1990) ''Kiratas in Ancient India: Displacement, Resettlement, Development''. India University Grants Commission, Indian Council of Social Science Research. New Delhi: Gian. ISBN 81-212-0329-5 | |||

| * Singh, Gursharan (ed.) (1996) ''Punjab history conference''. Punjabi University. ISBN 81-7380-220-3 ISBN 81-7380-221-1 | |||

| * Talbert, Richard J.A. (ed.) (2000) ''Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World''. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04945-8 | |||

| * Thion, Serge (1993) ''Watching Cambodia: Ten Paths to Enter the Cambodian Tangle''. Bangkok: White Lotus. ISBN 1-879155-19-2 ISBN 1-879155-20-6 ISBN 974-8495-91-4 ISBN 974-8495-91-0 | |||

| * Vaidya, Chintaman Vinayak (1986 ) ''Downfall of Hindu India''. Delhi: Gian Pub. House | |||

| * Vogelsang, Willem (2001) ''The Afghans''. Peoples of Asia Series. ISBN 978-1-4051-8243-0 | |||

| * Walker, Andrew and Nicholas Tapp (2001) in ''Tai World: A Digest of Articles from the Thai -Yunnan Project Newsletter''. Or in Scott Bamber (ed.) ''Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter''. Australian National University, Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies. http://www.nectec.or.th/thai-yunnan/20.html. ISSN 1326-2777 | |||

| * Witzel, M. (1999a) "Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic)", ''Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies'', 5:1 (September). | |||

| * Witzel, Michael (1980) "Early Eastern Iran and the Atharvaveda", ''Persica'' 9 | |||

| * Witzel, Michael (1999b) "Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.", in J. Bronkhorst & M. Deshpande (eds.), ''Aryans and Non-Non-Aryans, Evidence, Interpretation and Ideology''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Dept. of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University (Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 3). ISBN 1-888789-04-2 pp. 337–404 | |||

| * Witzel, Michael (2001) in ''Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies'' 7:3 (May 25), Article 9. ISSN 1084-7561 | |||

| * Yadav, Jhinkoo and Suman Gupta (eds.) (1996) ''Social justice: problems & perspectives, seminar proceedings of March 5–7, 1995, Felicitation volume for Sri Chandrajeet Yadav''. Varanasi: National Research Institute of Human Culture. | |||

| * Yar-Shater, Ehsan (ed.) (1983) The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. ISBN 0-521-20092-X ISBN 0-521-24693-8 (v.3/2) ISBN 0-521-24699-7 (v.3/1-2) | |||

| ==External links== | |||

| * B. C. Law, Some Kshatriya Tribes Of Ancient India, The Kambojas, | |||

| * | |||

| {{Ancient India and Central Asia}} | {{Ancient India and Central Asia}} | ||

| {{Tribes and kingdoms of the Mahabharata}} | |||

| {{Mahajanapada |state=collapsed}} | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

| ] | |||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | ] | ||

| ] | |||

Latest revision as of 21:58, 1 December 2024

Iranian people mentioned in the Indo-Aryan sources| It has been suggested that this article be merged with Kambojan language. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2024. |

The Kambojas were a southeastern Iranian people who inhabited the northeastern most part of the territory populated by Iranian tribes, which bordered the Indian lands. They only appear in Indo-Aryan inscriptions and literature, being first attested during the later part of the Vedic period.

They spoke a language similar to Younger Avestan, whose words are considered to have been incorporated in the Aramao-Iranian version of the Kandahar Bilingual Rock Inscription erected by the Maurya emperor Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE). They were adherents of Zoroastrianism, as demonstrated by their beliefs that insects, snakes, worms, frogs, and other small animals had to be killed, a practice mentioned in the Avestan Vendidad.

Etymology

Kamboja- (later form Kāmboja-) was the name of their territory and identical to the Old Iranian name of *Kambauǰa-, whose meaning is uncertain. A long-standing theory is the one proposed by J. Charpentier in 1923, in which he suggests that the name is connected to the name of Cambyses I and Cambyses II (Kambū̌jiya or Kambauj in Old Persian), both kings from the Achaemenid dynasty. The theory has been discussed several times, but the issues that it posed were never persuadingly resolved.

In the same year, Sylvain Lévi proposed that the name is of Austroasiatic origin, though this is typically rejected.

History

The Kambojas only appear in Indo-Aryan inscriptions and literature, being first attested during the later part of the Vedic period. The Naighaṇṭukas, a glossary and oldest surviving writing about Indian lexicography, is the first source to mention them. In his book about etymology—the Nirukta—the ancient Indian author Yaska comments on that part of the Naighaṇṭukas, in which he mentions that "the word śavati as a verb of motion is used only by the Kambojas", a statement that is more or less repeated in the exact same way by later authors, such as the grammarian Patanjali (2nd-century BCE) in his Mahabhashya. The word śavati is equivalent to š́iiauua- in Younger Avestan, which demonstrates that the Kambojas spoke an Iranian tongue with close ties to it. Modern historian M. Witzel surmised that grammarians and lexicographers must have first become acquainted with the word around 500 BCE or perhaps earlier, due to Yaska and Patanjali both using the same example known amongst grammarians and lexicographers.

According to Arthashastra of Kautilya, Kambojas were known as vartta-sastropajivinah, meaning they were a class of Kshatriya guilds which lived upon both trade and war.

The Major Rock Edicts of the Maurya emperor Ashoka (r. 268–232 BCE) contain the first attestations of the Kambojas that can be precisely dated. The thirteenth edict says "among Greeks and Kambojas" and the fifth edict says "of Greeks, Kambojas and Gandharians". It is uncertain if Ashoka was only referring to just the Kambojas or all the Iranian tribes in his empire. Regardless, the mentioned groups of people were part of the Maurya Empire, being influenced by its politics, culture and religious traditions, and also adhered to ideology of "righteousness" set by Ashoka.

The major Indian epic Mahabharata also mentions the Kambojas, alongside the Greeks, Gandharas, Bactrians and Indo-Scythians. Geographical texts in Sanskrit and the Aṅguttara Nikāya include the Kambojas as one of the sixteen kingdoms of the Indian subcontinent during the lifetime of the Buddha. Various characteristics of the Kambojas are also described in different types of Sanskrit and Pali literature; they shaved themselves bald; they had a king; Rāja-pura- (meaning "King's town") was the name of their capital, but its site remains unknown. As was typical of Iranians, the Kambojas were renowned for their skill in horse breeding, and it is believed that the horses they produced were the most suitable for use in battle. These horses were brought into India in large quantities and also given as tribute. Indologist Etienne Lamotte further suggests that reputation of Kambojas as homeland of horses possibly earned the horse-breeders known as Aspasioi (from Old Persian aspa) and Assakenoi (from Sanskrit aśva "horse") their epithet.

Following the death of Ashoka, the Maurya Empire fell into decline. During the start of the 2nd-century BCE, they lost their Indian-Iranian frontier lands (including Gandhara and Arachosia) to the forces of Demetrius I (r. 200–180 BCE), the king of the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. As a result, the Greek population of those areas were once again under the dominion of their Greek countrymen, while the Kambojas met other Iranians, as the Bactrians were likely a major component of the conquering army along with the Greeks.

Some historians consider the Kambojas to have established the Kamboja Pala dynasty in Bengal, but this remains uncertain. Some historians consider it to have founded by Kambojas who had settled in Bengal, a theory which may be supported by the attestation of a Kambojadeśa in the Lushai Hills by the Tibetan book Pag Sam Jon Zang. Hem Chandra Raychaudhuri proposed that the Kambojas may have travelled to Bengal from the northwestern frontier in the wake of Gurjara-Pratihara conquests during the lifetime of Narayanapala. He adds that those Kambojas perhaps acquired positions and, at a suitable time, seized power.

Richard Strand considers the Nuristani Kom people (aka Kamôzî or Kamôǰî) to be the descendants of the Kamboja people.

Language and location

Main article: Kambojan language

The Kambojas inhabited the northeastern most part of the territory populated by Iranian tribes, which bordered the Indian lands. In 1918, Lévi suggested it to be Kafiristan, but later retracted it in 1923; B. Liebich suggested they lived in the Kabul Valley; J. Bloch suggested that they lived to the north-east of Kabul; Lamotte considered them to live them from Kafiristan to the southwestern part of Kashmir.

In 1958, a new suggestion was put forward by the French linguist Émile Benveniste. He drew a comparison between the Kambojas and Greeks described in Ashoka's edicts in Kandahar and the two languages it was written in; Greek and "Aramao-Iranian", which refers to the Iranian language hidden in the text of the Aramaic alphabet. Ashoka wanted to use these two languages to convey his religious message to the inhabitants of what is now present-day eastern Afghanistan, around the Gandhara area, approximately between Kabul and Kandahar. Because of this, Benveniste considered the Iranian language used in Ashoka's inscriptions to be spoken by the Kambojas. The Iranologists Mary Boyce and Frantz Grenet also support this view, saying that "The fact that Aramaic versions were made indicates that the Kambojas enjoyed a measure of autonomy, and that they not only preserved their Iranian identity, but were governed in some measure by members of their own community, on whom was laid the responsibility of transmitting to them the king's words, and having these engraved on stone."

Gérard Fussman suggested that the unidentified Iranian language of the two rock-inscriptions (IDN 3 and 5) in Dasht-e Nawar was spoken by the Kambojas, perhaps an early stage of the Ormuri language. According to Rüdiger Schmitt; "If this hypothesis should prove to be true, we would be able to locate the Kambojas more precisely in the mountains around Ghazni and on the Upper Arghandab."

Religious beliefs

The Indo-Aryans considered the Kambojas to be "non-Aryan" (anariya-) strangers with their own peculiar traditions, as demonstrated in a portion of the Buddhist Jataka tales. Insects, snakes, worms, frogs, and other small animals had to be killed according to the Kambojas' religious beliefs. This practice has been linked by academics to the Avestan Vendidad for a long time, leading them to the conclusion that the Kambojas were adherents of Zoroastrianism. These beliefs are based on Zoroastrian dualism, which attributes the Evil Spirit to creatures like these and others that are poisonous or repulsive to humans. Hence, Zoroastrians were commanded to destroy them, and careful pursuit of this goal has been observed by outside spectators since the 5th-century BCE to the present.

Notes

- Scholarship agree that the Kambojas were Iranian. Richard N. Frye stated that "Their location and the meaning of the word Kamboja are much debated, but it is at least agreed that they were Iranians living to the northwest of the subcontinent."

See also

- Kamboj

- Cambodia

- Kambojan

- Parama Kambojas

- Komedes

- Arta (Kamuia)

- Kingdom of Kapisa

- Parachi

- Saptarishi Tila statue

- Rishikas

References

- ^ Schmitt 2021.

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (1922). Corporate Life in Ancient India. The Oriental Book Agency, p-29

- Sharma 2007, p. 145–152.

- ^ Boyce & Grenet 1991, pp. 129–130.

- ^ Lamotte 1988, p. 100.

- Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 149.

- Caudhurī 1967, p. 73.

- Strand, Richard (2022). "Kamboǰas and Sakas in the Holly-Oak Mountains: On the Origins of the Nûristânîs" (PDF). Nuristan: Hidden Land of the Hindu Kush.

- ^ Bailey 1971, p. 66.

- Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 136.

- Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 130.

- Schmitt 2021; Boyce & Grenet 1991, p. 129; Scott 1990, p. 45; Kubica 2023, p. 88; Emmerick 1983, p. 951; Fussman 1987, pp. 779–785; Eggermont 1966, p. 293.

- Frye 1984, p. 154.

Sources

- Bailey, H. W. (1971). "Ancient Kamboja". In Clifford Edmund Bosworth (ed.). Iran and Islam: In Memory of the Late Vladimir Minorsky. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 65–71. ISBN 978-0085224201.

- Boyce, Mary; Grenet, Frantz (1991). Beck, Roger (ed.). A History of Zoroastrianism, Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman Rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-9004293915.

- Caudhurī, Ābadula Mamina (1967). Dynastic History of Bengal, C. 750-1200 A.D. Asiatic Society of Pakistan.

- Eggermont, P.H.L. (1966). "The Murundas and the Ancient Trade-Route From Taxila To Ujjain". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. 9 (3). Brill: 257–296. doi:10.1163/156852066X00119.

- Emmerick, R. E. (1983). "Buddhism among Iranians". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 3(2): The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian Periods. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 949–964. ISBN 0-521-24693-8.

- Kubica, Olga (2023). Greco-Buddhist Relations in the Hellenistic Far East: Sources and Contexts. Routledge. ISBN 978-1032193007.

- Fussman, G. (1987). "Aśoka ii. Aśoka and Iran". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica. Vol. II/7:ʿArūż–Aśoka IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 779–785. ISBN 978-0-71009-107-9.

- Frye, R. N. (1984). The History of Ancient Iran. C.H. Beck. ISBN 978-3406093975.

- Lal, Deepak (2005). The Hindu Equilibrium: India C.1500 B.C. - 2000 A.D. Oxford University Press. p. xxxviii. ISBN 978-0-19-927579-3.

- Lamotte, Etienne Lamotte (1988). Webb-Boin, Sara (ed.). History Of Indian Buddhism. Peters Press. ISBN 978-9068311006.

- Schmitt, Rüdiger (2021). "Kamboja". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica (Online ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica Foundation.

- Scott, David Alan (1990). "The Iranian Face of Buddhism". East and West. 40 (1): 43–77. JSTOR 29756924. (registration required)

- Sharma, Ram Sharan (2007). "Chapter 15: Territorial States and the Rise of Magadha". India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press. pp. 145–152. ISBN 9780199080366.

The rise of large states with towns as their base of operations strengthened the territorial idea. People owed strong allegiance to the janapada or the territory to which they belonged rather than to their jana or tribe. The Pali texts reveal that the janapadas grew into mahajanapadas. Gandhara and Kamboja were important mahajanapadas. Kamboja is called a janapada in Panini and a mahajanapada in the Pali texts.

| Ancient India and Central Asia | |

|---|---|

| Archaeology and prehistory | |

| Historical peoples and clans | |

| States | |

| Mythology and literature | |

| Mahajanapadas | |

|---|---|

| Great Indian Kingdoms (c. 600 BCE–c. 300 BCE) | |